Abstract

We present a rare case of low-grade diffusely infiltrative tumor (LGDIT), SMARCB1-mutant, recurred as an atypical teratoid/rhabdoid tumor (AT/RT) seven years after complete resection. Comprehensive genetic and epigenetic analysis of both LGDIT, SMARCB1-mutant, and AT/RT samples revealed that SMARCB1 mutation and methylation patterns are stable during the latent period and not the direct target that determines the malignant phenotype of cancer. However, there was a switch of oncogenic signaling pathways from the MAPK pathway to the PI3K/AKT pathway with accumulation of somatic variants responsible for the inherent malignant phenotype. Considering the dormant oncogenic traits behind an innocent phenotype, it is recommended to confirm the diagnosis of LGDIT, SMARCB1-mutant, by conducting a methylation classifier analysis or an SMARCB1 expression study to ensure accurate prognosis prediction.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Atypical teratoid/rhabdoid tumor (AT/RT) is a highly malignant, true rhabdoid tumor in the central nervous system (CNS) predominantly presenting in infants and young children1. The prognosis for AT/RT is generally poor, with a median survival of 15-18 months in adults, although it can vary widely ranging from as short as 2 weeks to over 17 years2. Key molecular aspects associated with AT/RT include alterations in the SMARCB1 or SMARCA4 genes3. Of these two genes, the majority of rhabdoid tumors contain bi-allelic inactivating mutations in the SMARCB1 gene. SMARCB1 is expressed in human cells and is a member of the SWI/SNF chromatin remodeling complex, a multiprotein transcriptional modulator that underlies this protein’s role as a tumor suppressor4. The disruption of SWI/SNF function can lead to an ‘epigenetic instability’ state, where altered chromatin structure affects gene expression and disrupts differentiation programs5. Several downstream pathways are known to be modulated by SMARCB1, including the PI3K/AKT pathway. The PI3K/AKT pathway plays a crucial role in regulating cell proliferation and metastasis in various tumor types. Multiple studies have revealed that this pathway is extensively activated in various tumor types6.

AT/RT typically arises de novo. However, rare cases of AT/RT or INI1-deficient rhabdoid tumor have been reported to develop from other primary CNS tumors7. Recently, CNS low-grade diffusely infiltrative tumor (LGDIT) with SMARCB1-mutant, a novel disease entity based on sporadic case reports, has been proposed8,9,10,11,12,13. LGDIT, SMARCB1-mutant, occurs in the supratentorial area in children and young adults, and is clearly distinguished from AT/RT by low proliferative activity, a diffusely infiltrative growth pattern, and the lack of rhabdoid cells and polyphenotypic immunoreactivity11. LGDIT, SMARCB1-mutant, typically shows an indolent clinical course after surgery in the majority of cases, but in some cases, progression to malignancy has been observed10,11,13. The epigenetic profile of LGDIT, SMARCB1-mutant based on DNA-methylation patterns, has been classified as ATRT-MYC8,9,12. However, due to limited experience, it has not yet been definitively proven whether all LGDIT, SMARCB1-mutant are precancerous conditions of AT/RT.

Here, we present an additional case of LGDIT, SMARCB1-mutant, unusually occurring in a middle-aged adult, which eventually recurred in the vicinity of the primary site as an AT/RT after 7 years. Comprehensive genetic and epigenetic analyzes of both LGDIT, SMARCB1-mutant, and AT/RT samples revealed that SMARCB1 mutation was commonly present and methylation profiles did not differ significantly, suggesting that accumulation of additional genetic alterations as the driver mechanism for the inherent malignant phenotype to manifest during the latent period.

Results

Case presentation

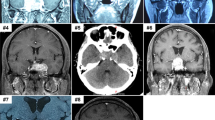

A 52-year-old female presented with behavioral seizures, such as intermittent chest discomfort and emotional lability. Initial brain magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) revealed a poorly-demarcated mass lesion in the right anterior temporal lobe characterized by T2 high signal intensity and focal enhancement (Fig. 1). Gross total resection of the tumor was performed. At the time of the initial surgery, genetic profiling of the tumor tissue was not performed, and only histological diagnosis rendered ganglioglioma, CNS WHO grade 1. The patient had since been doing well without any recurrence of the tumor and with complete control of epilepsy.

(Left) MRI scans showing axial T2-weighted (T2) and T1-weighted post-contrast enhancement (T1E) images. (Right) Hematoxylin and eosin (H&E) staining reveals the cellular architecture. (Top) In LGDIT, SMARCB1-mutant, H&E shows a cortex-based lesion with overall low cellularity, composed of unusually shaped neuronal cells intermingled with glial-like cells. INI-1 immunostaining demonstrates loss of expression predominantly in the glial-like cell population. NeuN highlights non-tumorous neurons exhibiting reactive atypia. Ki-67 indicates a low proliferative index. (Bottom) In AT/RT, INI1 shows complete nuclear loss in tumor cells. NeuN is negative. Synaptophysin shows weakly positive.

However, seven years after the initial surgery, the patient presented with headache and vomiting. MRI demonstrated a well-enhancing mass in the right inferior frontal lobe extending to the insular lobe (Fig. 1). Revision craniotomy and near-total resection of the tumor were performed. Histopathological examination revealed atypical rhabdoid cells with high cellularity, and immunohistochemistry showed loss of nuclear expression of INI-1, confirming the final diagnosis of AT/RT, CNS WHO grade 4 (Fig. 1). Despite adjuvant radiotherapy, the tumor showed rapid progression, and the patient died 4 months after the surgery.

When we retrieved the initial tumor specimen, neoplastic tissue of low cellularity and low proliferative index characterized by unusually shaped neuronal cells intermixed with glial-like cells, was observed. Retrospective INI-1 immunostaining demonstrated a loss of expression predominantly in the glial-like cells (Supplementary Fig. 1). Dysmorphic binucleated ganglion cells were not observed in the initial resection specimen, supporting that this lesion is not a ganglioglioma. Based on newly revised diagnostic criteria that have recently begun to be proposed, the initial tumor could be interpreted as a LGDIT, SMARCB1-mutant.

DNA methylation profiling

To examine a putative subtype classification for our samples, Uniform Manifold Approximation and Projection (UMAP) was performed using filtered and normalized DNA methylation data. The analysis included 147 samples from the GSE109381 dataset, comprising AT/RT-MYC (31 samples), AT/RT-SHH (51 samples), AT/RT-TYR (39 samples), and LGG-GG (26 samples) on top of our two samples labeled as “LGDIT, SMARCB1-mutant” and “AT/RT”, bringing the total number of samples to 149. The UMAP plot revealed distinct clusters corresponding to AT/RT subtypes (SHH, MYC, TYR) and LGG, GG. Both “LGDIT, SMARCB1-mutant” and “AT/RT” samples were positioned within the AT/RT cluster, indicating their methylation profiles align with AT/RT rather than LGG, GG (Fig. 2A). This suggests that although the tumor was phenotypically low-grade tumor, it already possessed the epigenetic signature of AT/RT, indicating that this trait has remained unchanged over a long period. These results were consistently reproduced using the DKFZ methylation profiling classifier. The DKFZ results identified the “LGDIT, SMARCB1-mutant” sample as AT/RT, showing a calibrated score of 0.96704 (Fig. 2B). The AT/RT sample was also classified as AT/RT, with a calibrated score of 0.9543414. The minimal epigenetic changes observed during the transformation from LGDIT, SMARCB1-mutant, to AT/RT suggest that the tumor had already acquired the AT/RT signature at the LGDIT, SMARCB1-mutant stage.

a UMAP visualization of methylation profiles categorizing the target samples (“LGDIT, SMARCB1-mutant” and “AT/RT”) with reference AT/RT subgroups (SHH, MYC, TYR) and LGG, GG samples. Both “LGDIT, SMARCB1-mutant” and “AT/RT” are mapped in proximity to AT/RT in the UMAP space. b Brain classifier results (Version: 12.8) for LGDIT, SMARCB1-mutant, and AT/RT based on methylation profiling. The DKFZ methylation classifier, created by the German Cancer Research Center (DKFZ), University Hospital Heidelberg, and the German Consortium for Translational Cancer Research (DKTK), was utilized by uploading the sample’s IDAT files to their website as instructed. The table shows the calibrated scores and interpretations for methylation classes in LGDIT, SMARCB1-mutant, (top) and AT/RT (bottom). The “LGDIT, SMARCB1-mutant” sample was classified as AT/RT with a calibrated score of 0.96704. Subtypes such as “MYC Activated” and “SHH Activated” yield lower scores and are categorized as no match. The “AT/RT” sample was classified as AT/RT with a calibrated score of 0.95434. Specific subtypes “MYC Activated” (calibrated score: 0.87404) did not match.

Whole genome sequencing analysis

Next, we sought to elucidate the genetic relationship between the initial and recurrent tumors leading to the malignant transformation of a tumor with a different phenotype, we conducted Whole Genome Sequencing (WGS) using both LGDIT, SMARCB1-mutant, and AT/RT samples. Compared with the paired blood sample, a total of 13,560 somatic variants were identified, including 8235 variants in intergenic regions, 5080 in intronic regions, and 245 in exonic regions. Among these, 4802 variants were specific to LGDIT, SMARCB1-mutant, and 6279 variants were specific to AT/RT. Also, 2479 variants were shared between the two samples (Supplementary Table 1).

We identified non-synonymous single nucleotide variations (nsSNVs) that are completely overlapping at the nucleotide position in both LGDIT, SMARCB1-mutant, and AT/RT samples. Among these genes, genes harboring missense mutations that are classified as probably damaging or possibly damaging by PolyPhen-2 include NLRP11, LRRC36, PPARGC1A, OR4L1, NCOR2, TRPM3, and CEP9715. The gene with start-gained mutations is EYA1 and genes with stop-gained mutations are FBXW7, NUTM1, and SMARCB1 (Fig. 3A). Also, the 3’ UTR variant (c.*3834 T > C) in the BRAF gene was identified in both samples. However, no variants in the KRAS, NF1, FGFR, CDKN2A, and SMARCA4 genes were identified in either of the samples.

a Genes with non-synonymous mutations that have damaging effects in LGDIT, SMARCB1-mutant, and/or AT/RT. (Left) Chromosomal positions of non-synonymous mutations are mapped across the genome, with mutation types denoted by color: red dots represent mutations common to both LGDIT, SMARCB1-mutant, and AT/RT, yellow dots indicate mutations specific to LGDIT, SMARCB1-mutant, and green dots indicate mutations specific to AT/RT. (Right) heatmap showing the overlap and specificity of genes carrying non-synonymous mutations with damaging effects in LGDIT, SMARCB1-mutant, and AT/RT. Genes are categorized into LGDIT, SMARCB1-mutant-specific, AT/RT-specific, or common to both tumors. b Chromosomal CNVs in LGDIT, SMARCB1-mutant, and AT/RT across whole chromosomes. CNV profiles across all chromosomes in LGDIT, SMARCB1-mutant, (top) and AT/RT (bottom). CNV profiles derived from WGS-based analysis (left) and EPIC array-based analysis (right) are shown. Chromosome 19 is highlighted with a red box. The x-axis indicates chromosome number, while the y-axis shows the log2 ratio of copy number alterations.

In addition, a novel SMARCB1 mutation was observed at a new nucleotide position in both samples. A G-to-T substitution in the SMARCB1 gene results in a premature stop codon (c.790 G > T | p.Glu264*), leading to truncation of the SMARCB1 protein. This mutation was detected in both the LGDIT, SMARCB1-mutant, and AT/RT samples; however, its absence in the blood sample confirms its somatic origin. Allele fractions, assessed using Integrative Genomics Viewer (IGV), differed between tumors. The mutant T allele was observed at 44% in the LGDIT, SMARCB1-mutant, sample and 31% in the AT/RT sample (Supplementary Fig. 2)16.

Next, we analyzed somatic variants specific to AT/RT in nsSNVs. Among these, genes filtered out missense variants predicted to be benign by PolyPhen-2 were ACADS, MME, DST, CD74, OR2M5, IRF8, COBL, PLEC, CTNNB1, PTPN6, CYBA, RGS2, EXD3, TOR1B, HK3, and ZNF729. Genes with start-gained mutations include SCHIP1 and TOX2, while genes with stop-gained mutations include TRIM71 and NLRP8. Additionally, KMT5B harbors both a frameshift mutation (c.526_533de | p.Lys176fs) and a deletion (c.535_540de | p.Lys179_Glu180del) (Fig. 3A).

WGS analysis also revealed differences in the Copy number variation (CNV) patterns between LGDIT, SMARCB1-mutant, and AT/RT. During the transition to AT/RT, a broad gain across chromosome 19 was observed. This finding was consistent with the results of methylation-based CNV analysis (Fig. 3B).

Integrative analysis of whole genome sequencing and transcriptomic data

We investigated the expression level of genes harboring nsSNVs with a non-benign PolyPhen-2 prediction in AT/RT (Fig. 4A). For this, we conducted RNA-seq and compared expression levels between the two samples. On the other hand, DNA methylation array and CpG methylation analysis were also performed to compare and analyze the expression results. In ATRT-specific genes, OR2M5, TRIM71, and COBL showed decreased RNA expression, and MME and HK3 demonstrated increased RNA expression. It is notable that TRIM71, known to have a tumor suppressor function, was downregulated in AT/RT compared with LGDIT, SMARCB1-mutant.

a Analysis of genes with non-synonymous somatic mutations that have damaging effects in AT/RT. The top panel shows allele fractions of DNA mutations, with mutations in LGDIT, SMARCB1-mutant, (yellow) and AT/RT (green), with corresponding RNA expression and DNA methylation status of the genes in LGDIT, SMARCB1-mutant, and AT/RT. b Somatic variants and molecular profiles specific to AT/RT. Somatic variants unique to AT/RT were identified across intergenic, intronic, and exonic regions, with 167 genes showing significant RNA expression changes ( | log2FC | > 5). The top panel illustrates the allele fraction of variants categorized as intronic/intergenic (yellow) or exonic (green). The middle panel displays RNA expression levels (log-transformed counts per million, log(CPM + 1)) for LGDIT, SMARCB1-mutant, and AT/RT. The bottom panel shows methylation beta values stratified by genomic features, including promoters, enhancers, and gene bodies, comparing LGDIT, SMARCB1-mutant, and AT/RT. Gene names with red color indicate known oncogenes. blue gene names indicate known tumor suppressor genes.

Next, we assessed whether the variants specific to AT/RT across all regions, including intergenic, intronic, and exonic regions, were intertwined with the gene expression changes during the malignant transformation. After filtering for genes harboring variants with an expression difference of absolute log fold change greater than or equal to 5, only 167 genes remained (Fig. 4B, Supplementary Table 2). It was found that most genes with variants that could explain the differences in RNA expression showed little change in methylation patterns, implying that epigenetic changes are not the major contributor to the malignant transformation of LGDIT, SMARCB1-mutant.

Gene ontology and Kyoto encyclopedia of genes and genomes pathway analysis

Using the set of 167 differentially expressed genes, we performed Gene Ontology (GO) enrichment analysis. The analysis revealed distinct biological processes, molecular functions, and cellular components associated with genes exhibiting significant expression changes (Fig. 5A). Activated genes in AT/RT were enriched in processes related to cell adhesion, including ITGA6, MME, PIK3R2, and SKAP1, and in extracellular processes, including NPR3, CEACAM1, ACTG2, CA1, and MME. Suppressed genes in AT/RT were associated with synaptic function, including the postsynaptic density membrane, with involvement of GRID2, SHISA9, GRM1, and SORCS3 (Fig. 5A). The KEGG pathway analysis revealed that the “Hematopoietic cell lineage”, “T cell receptor signaling pathway”, “Motor proteins”, and “PI3K/AKT signaling pathway” had the highest expression in AT/RT. Conversely, the “Neuroactive ligand-receptor interaction”, “Protein digestion and absorption”, “Cholinergic synapse”, and “Calcium signaling pathway” exhibited significant downregulation in AT/RT (Fig. 5B). Notably, in our gene set, ITGA6 and PIK3R2 are involved in the upregulation of the PI3K/AKT signaling pathway, while PHLPP2 is involved in its downregulation.

a GO analysis showing altered biological pathways in AT/RT compared to LGDIT, SMARCB1-mutant. The dot plot visualizes enriched pathways categorized into seven functional groups: Cell adhesion, Neuronal synapse, Extracellular structures, Membrane interaction, Intracellular structure, Calcium binding, and Physiological regulation. The size of the dots represents the count of genes associated with each pathway, while the color indicates activation (orange) or suppression (green) in AT/RT relative to LGDIT, SMARCB1-mutant. b The diagram illustrates significant pathways, upregulated (orange) or downregulated (green) in AT/RT compared with LGDIT, SMARCB1-mutant. Genes related to each pathway are displayed within the respective sections. c Schematic representation of MAPK pathway with genes upregulated (orange) and downregulated (green) in LGDIT, SMARCB1-mutant. d Schematic representation of PI3K/AKT pathway with genes upregulated (orange) and downregulated (green) in AT/RT. This figure was created using Inkscape 1.4 software.

To focus specifically on the MAPK pathway and the PI3K/AKT pathway, we re-conducted KEGG pathway analysis using only the RNA count data based on a logFC threshold of 2 or -2 from our LGDIT, SMARCB1-mutant, and AT/RT samples (Figs. 5C, 5D). In LGDIT, SMARCB1-mutant, key components of the MAPK pathway, such as PKC, Ras, and JNK, exhibit increased expression (Fig. 5C). In AT/RT, PI3K is activated by upregulation of upstream growth factors and receptor tyrosine kinases (RTKs), triggering downstream signaling cascades (Fig. 5D). Cytokines and extracellular matrix (ECM) components alongside integrins are also involved in PI3K activation. Membrane metalloendopeptidase (MME) was identified as a downstream effector of PI3K that mediates the induction of senescence. We identified that MME was positively related to AT/RT.

Discussion

We report a rare case of a patient who progressed from LGDIT, SMARCB1-mutant, to AT/RT. To our knowledge, this study is the first to report comprehensive genetic and epigenetic profiling of a case that progressed from LGDIT, SMARCB1-mutant, to AT/RT. We determined that although LGDIT, SMARCB1-mutant, is typically low-grade in histology, it already possessed the genetic and epigenetic traits of AT/RT, which can eventually be transformed into a malignant phenotype by the accumulation of additional genetic changes. This study focuses on analyzing the key genes and mutations altered during the transformation from LGDIT, SMARCB1-mutant, to AT/RT. Among the newly acquired mutations in AT/RT, genetic changes resulted in the activation of the PI3K/AKT pathway.

There have been a few documented cases of malignant transformation of LGDIT, SMARCB1-mutant, to AT/RT. Nadi et al. reported a case of a tumor that initially presented as a Dysembryoplastic neuroepithelial tumor (DNET), which had focal loss of INI1 immunostaining, progressed to an AT/RT over 7 years10. Schweizer et al. described a rare case of transformation of a SMARCB1-deleted low-grade brain tumor into an AT/RT over 14 years13. Analysis of AT/RT demonstrated the closest relation to the AT/RT-MYC molecular subgroup, while the initial tumor and first relapse showed a mixed profile between the AT/RT-MYC and AT/RT-SHH subgroups. Additionally, the similar DNA methylation profiles across the three tumor manifestations imply that SMARCB1 is stable driver oncogene that contributes to shaping the methylation profile of the dormant oncogenic traits. Nobusawa et al. reported malignant transformation to AT/RT in 2 of 3 cases of SMARCB1-mutant low-grade brain tumor, which they originally named CNS LGDITs with INI1 deficiency (CNS LGDIT-INI1)11. Later, Hasselblatt et al. analyzed 6 consult cases and proposed the LGDIT, SMARCB1-mutant as a distinct entity12.

Since the SMARCB1 mutation has been present since LGDIT, SMARCB1-mutant, the development of the malignant phenotype of AT/RT cannot be explained by the SMARCB1 mutation alone. This SMARCB1 mutation may have played a critical role in the early stages of tumorigenesis. These findings underscore the importance of early detection and monitoring of SMARCB1 mutations in patients with low-grade tumor, as such mutations could signal a risk of progression to more aggressive tumors of AT/RT.

The higher proportion of the wild-type G allele in the AT/RT sample may also indicate the presence of residual non-tumor cells or subclonal populations within the tumor. Despite possible dilution of mutant alleles by non-neoplastic cell contamination, our genomic analysis showed that the AT/RT sample harbors a higher mutational burden across whole, intronic, and exonic regions than the LGDIT, SMARCB1-mutant. These additional variants could have introduced new clonal populations or altered the selective pressures within the tumor microenvironment, driving further tumor evolution.

The patient did not receive radiotherapy or chemotherapy prior to recurrence; therefore, the observed variations are not therapy-induced. Additionally, epigenetic changes are relatively stable and are also not factors contributing to malignant transformation.

We observed a significant upregulation of key components associated with ECM interactions and RTK signaling in AT/RT. In mammals, the PI3K/AKT pathway is activated by RTKs, integrins, and various growth factor receptors, through multiple upstream pathways that connect diverse cell surface receptors to specific class I PI3K isoforms17. Among the downstream effectors of PI3K, we detected activation of SGK and MME in AT/RT. SGK plays an AKT-independent role in cellular transformation18. Notably, MME mediates the induction of senescence through mechanisms potentially associated with its glycosylation19. We hypothesize that after the initial surgical removal of the tumor, nearby SMARCB1-mutated cells triggered changes related to the PI3K/AKT signaling pathway, leading to the development of AT/RT.

In summary, we report an additional case of LGDIT, SMARCB1-mutant and provided insights into the potential underlying genetic mechanisms mediating LGDIT, SMARCB1-mutant progression to AT/RT

Methods

Sample collection

This study was approved by the institutional ethics committee of Seoul National University Hospital (H-2305-099-1432). Patient samples were collected after obtaining written informed consent for research purposes, including genetic studies, in accordance with the institutional review board guidelines (H-0507-509-153). Every method carried out in this study involving human subjects complied with the Declaration of Helsinki and its subsequent revisions or similar ethical standards

Tumor tissues were snap-frozen in liquid nitrogen immediately after removal and stored at −80 °C. Blood samples were also collected at the time of tumor removal, and WBCs were isolated from the buffy coat and stored at −80 °C.

DNA and RNA extraction and library preparation

DNA was isolated from frozen tumor tissues and WBC samples using the Qiagen QIAamp DNA Mini Kit (Qiagen, Valencia, CA), and RNA was extracted from frozen tumor tissues using the RNeasy Lipid Tissue Mini Kit (Qiagen, Valencia, CA), following the manufacturer’s instructions. The extracted DNA and RNA were used for whole-genome sequencing (WGS), DNA Methylation array and RNA sequencing (RNA-seq).

Genomic DNA was fragmented using Covaris sonicator to generate double-stranded DNA fragments with 3’ or 5’ overhangs. End repair and size selection were performed to produce blunt-ended fragments, followed by adenylation of the 3’ ends and ligation of indexed adapters. For the TruSeq Nano DNA library, PCR amplification was conducted to enrich the DNA fragments. The generated BCL/cBCL binary was then converted into raw FASTQ files utilizing the Illumina bcl2fastq2-v2.20.0 package.

For the extracted RNA, quality control was conducted to select qualified samples for library construction. Libraries were prepared through random DNA or cDNA fragmentation, adapter ligation, and PCR amplification. Sequencing was performed using Illumina sequencer. Raw sequencing data were processed into FASTQ format using Real Time Analysis software and bcl2fastq.

WGS analysis

The raw FASTQ files were aligned to the GRCh37 human genome using BWA (ver. 0.7.17)-MEM to generate SAM files. SAM files were converted to BAM format and sorted BAM using SAMtools (ver. 1.21). Duplicate reads were marked using Picard’s MarkDuplicates, and read groups were added with AddOrReplaceReadGroups. BAM files were indexed using Picard (ver. 3.3.0) BuildBamIndex. Base quality score recalibration was performed with GATK (ver. 4.5.0.0) BaseRecalibrator using known variant sites from dbSNP and indel databases, followed by application of the recalibration with GATK ApplyBQSR. Somatic variant calling was conducted using GATK Mutect2 in tumor–normal paired mode with default parameters, and variants were filtered with GATK FilterMutectCalls. Annotated VCF files were generated using SnpEff. CNV was performed using CNVkit (ver. 0.9.11) in whole-genome sequencing mode (batch -m wgs option)20,21,22.

RNA-seq analysis

Raw FASTQ files were assessed with FastQC, and adapter trimming and quality filtering were performed using Trimmomatic (ver. 0.39). Reads were aligned to the GRCh37 human genome using HISAT (ver. 2.2.1), and SAM files were converted to sorted BAM files with SAMtools. Transcript assembly and read quantification were performed using StringTie, and gene count matrices were generated with prepDE.py. Differential expression analysis was conducted with edgeR in R (ver. 4.4.1), using TMM normalization and log2 counts per million (CPM). Log2 fold changes (logFC) were calculated by comparing CPM values between samples. GO analysis was performed using the clusterProfiler package in R with log2 fold change values and the org.Hs.eg.db database23. GO terms across Biological Process, Molecular Function, and Cellular Component were analyzed. KEGG pathway analysis was conducted using the KEGG Mapper – Color tool based on human-specific pathways.

DNA Methylation array and CpG methylation analysis

Genomic DNA was analyzed using Illumina Infinium MethylationEPIC BeadChip kits (Illumina, Inc., San Diego, CA), and methylation arrays were scanned using the Illumina iScan scanner. Methylation data points were quantified based on fluorescent signals from methylated (M) and unmethylated (U) alleles. For UMAP analysis, DNA methylation data from 147 samples (GSE109381) including AT/RT-MYC (31 samples), AT/RT-SHH (51 samples), AT/RT-TYR (39 samples), and LGG-GG (26 samples), were used on top of the data from this study14,24. UMAP analysis was performed using the umap package in R.

Immunohistochemistry

Three-micrometer-thick sections were prepared from formalin-fixed, paraffin-embedded (FFPE) tissue blocks and subjected to immunohistochemical analysis. Tissue sections were stained with anti-INI-1 (Cell Marque, Rocklin, 1:100), anti-Neu-N (Millipore, Temecula, 1:500), anti-Ki-67 (DAKO, Glostrup, Denmark, 1:100), and anti-Synaptophysin (Novocastra, Newcastle, 1:200). INI-1, Neu-N, and Ki-67 were stained using the OPTIVIEW DAB IHC Detection Kit on the VENTANA (Roche), while Synaptophysin was stained using the POLYMER DETECTION Kit with counterstain on the BONDIII (Leica). The staining procedure was conducted using a Non-Biotin Amplification method.

Data availability

All data generated or analyzed during this study are included in this published article and are available in Supplementary Data.

References

Rorke, L. B., Packer, R. J. & Biegel, J. A. Central nervous system atypical teratoid/rhabdoid tumors of infancy and childhood: definition of an entity. J. Neurosurg. 85, 56–65 (1996).

Shonka, N. A. et al. Atypical teratoid/rhabdoid tumors in adults: a case report and treatment-focused review. J. Clin. Med. Res. 3, 85–92 (2011).

Louis, D. N. et al. The 2021 WHO classification of tumors of the central nervous system: a summary. Neuro Oncol. 23, 1231–1251 (2021).

Roberts, C. W. & Biegel, J. A. The role of SMARCB1/INI1 in development of rhabdoid tumor. Cancer Biol. Ther. 8, 412–416 (2009).

Wilson, B. G. & Roberts, C. W. SWI/SNF nucleosome remodellers and cancer. Nat. Rev. Cancer 11, 481–492 (2011).

He, Y. et al. Targeting PI3K/Akt signal transduction for cancer therapy. Signal Transduct. Target Ther. 6, 425 (2021).

Nobusawa, S. et al. Secondary INI1-deficient rhabdoid tumors of the central nervous system: analysis of four cases and literature review. Virchows Arch. 476, 763–772 (2020).

Dottermusch, M., Schumann, Y., Kordes, U., Hasselblatt, M. & Neumann, J. E. Spatial molecular profiling of a central nervous system low-grade diffusely infiltrative tumour with INI1 deficiency featuring a high-grade atypical teratoid/rhabdoid tumour component. Neuropathol. Appl Neurobiol. 48, e12777 (2022).

Zhao, M. et al. A 7-year-old boy presented with temporal lobe lesion. Brain Pathol. 34, e13246 (2024).

Nadi, M. et al. Atypical teratoid rhabdoid tumor diagnosis after partial resection of dysembryoplastic neuroepithelial tumor: case report and review of the literature. Pediatr. Neurosurg. 51, 191–198 (2016).

Nobusawa, S. et al. CNS low-grade diffusely infiltrative tumors with ini1 deficiency, possessing a high propensity to progress to secondary INI1-deficient rhabdoid tumors. Am. J. Surg. Pathol. 44, 1459–1468 (2020).

Hasselblatt, M. et al. Low-grade diffusely infiltrative tumour (LGDIT), SMARCB1-mutant: a clinical and histopathological distinct entity showing epigenetic similarity with ATRT-MYC. Neuropathol. Appl. Neurobiol. 48, e12797 (2022).

Schweizer, Y. et al. Molecular transition of an adult low-grade brain tumor to an atypical teratoid/rhabdoid tumor over a time-course of 14 years. J. Neuropathol. Exp. Neurol. 76, 655–664 (2017).

Capper, D. et al. DNA methylation-based classification of central nervous system tumours. Nature 555, 469–474 (2018).

Adzhubei, I. A. et al. A method and server for predicting damaging missense mutations. Nat. Methods 7, 248–249 (2010).

Robinson, J. T., Thorvaldsdottir, H., Turner, D. & Mesirov, J. P. igv.js: an embeddable JavaScript implementation of the Integrative Genomics Viewer (IGV). Bioinformatics 39 https://doi.org/10.1093/bioinformatics/btac830.(2023).

Fruman, D. A. et al. The PI3K pathway in human disease. Cell 170, 605–635 (2017).

Cao, H. et al. Functional role of SGK3 in PI3K/Pten driven liver tumor development. BMC Cancer 19, 343 (2019).

Liu, X. L. et al. Membrane metallo-endopeptidase mediates cellular senescence induced by oncogenic PIK3CA(H1047R) accompanied with pro-tumorigenic secretome. Int. J. Cancer 145, 817–829 (2019).

Talevich, E., Shain, A. H., Botton, T. & Bastian, B. C. CNVkit: genome-wide copy number detection and visualization from targeted DNA sequencing. PLoS Comput. Biol. 12, e1004873 (2016).

Olshen, A. B. et al. Parent-specific copy number in paired tumor-normal studies using circular binary segmentation. Bioinformatics 27, 2038–2046 (2011).

Venkatraman, E. S. & Olshen, A. B. A faster circular binary segmentation algorithm for the analysis of array CGH data. Bioinformatics 23, 657–663 (2007).

Yu, G., Wang, L. G., Han, Y. & He, Q. Y. clusterProfiler: an R package for comparing biological themes among gene clusters. OMICS 16, 284–287 (2012).

Sievers, P. et al. Pediatric-type high-grade neuroepithelial tumors with CIC gene fusion share a common DNA methylation signature. npj Precis. Oncol. 7, 30 (2023).

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by the National Research Foundation of Korea(NRF) grant funded by the Korea government (MSIT) (RS-2024-00335143).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

The study was designed by H.L. and C.K.P. Clinical information and patient samples were collected by J.H.H., S.M.N., and C.K.P. H.J.K., W.S., and H.L. performed all the computational analyzes. Experimental work was undertaken by H.J.K. H.J.Y. J.K.W., and S.H.P. evaluated pathological diagnosis. All authors contributed to the interpretation of results. H.J.K., W.S., H.L., and C.K.P. wrote the manuscript, and all the authors approved the manuscript.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing Interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Kim, H.J., Song, W., Hwang, J.H. et al. Malignant transformation of low-grade diffusely infiltrative tumor (LGDIT), SMARCB1-mutant to atypical teratoid/rhabdoid tumor (AT/RT). npj Genom. Med. 11, 7 (2026). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41525-025-00543-y

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41525-025-00543-y