Abstract

Microgravity-induced bone loss increases urinary calcium excretion which increases kidney stone formation risk. Not all individuals show the same degree of increase in urinary calcium and some pre-flight characteristics may help identify individuals who may benefit from in-flight monitoring. In weightlessness the bone is unloaded, and the effect of this unloading may be greater for those who weigh more. We studied whether pre-flight body weight was associated with increased in-flight urinary calcium excretion using data from Skylab and the International Space Station (ISS). The study was reviewed and approved by the National Aeronautics and Space Administration (NASA) electronic Institutional Review Board (eIRB) and data were sourced from the Longitudinal Study of Astronaut Health (LSAH) database. The combined Skylab and ISS data included 45 participants (9 Skylab, 36 ISS). Both weight and day in flight were positively related to urinary calcium excretion. There was also an interaction between weight and day in flight with higher weight associated with higher calcium excretion earlier in the mission. This study shows that pre-flight weight is also a factor and could be included in the risk assessments for bone loss and kidney stone formation in space.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Prolonged microgravity exposure during long-duration human space flight results in a physiological imbalance of bone remodeling1. Weightlessness unloads the skeleton so that bone resorption is favored over bone formation1. This results in significant loss of bone mineral density, at a rate of approximately 1–1.5% per month in weight-bearing areas like the hip and lumber spine, which is only partially responsive to non-pharmacological countermeasures2,3. Additionally, microgravity-induced bone resorption leads to calcium loss from bone which enters the systemic circulation and is excreted in the urine4. As a result, the increased urinary calcium can supersaturate leading to an increased risk of kidney stone formation.

Microgravity-induced bone loss and kidney stone risk are currently unresolved health risks for long-duration space travelers5. Generally, crew members engage in physical exercise for fifteen hours a week to reduce these risks6. On long-duration International Space Station (ISS) flights, these risks are currently being controlled by careful astronaut selection, attention to hydration, as well as an exercise program7,8. The risk of bone loss and kidney stone formation has not been completely eliminated through these measures9.

On Earth, a variety of factors influence these risks including sex, dietary intake, race, genetic predisposition, lifestyle, and comorbidities10,11. There is also inherent variability in the amount of urinary calcium healthy as well as diseased individuals normally excrete12,13. The normal range for urinary calcium is wide, and its limits are not well described14. This suggests that not all individuals are at equal risk of losing bone or forming kidney stones in space. Identifying those at highest risk of these complications may help inform measures to reduce these risks. As commercial and lunar spaceflight is projected to become increasingly popular, the risk of bone loss and kidney stone formation may increase due to less stringent screening and smaller spacecraft with limited countermeasure capability. In contrast to rigorous astronaut selection among career-astronauts, medical screening for commercial spaceflight passengers may be less aggressive15. As a result, passengers among the general population who have risk factors for bone loss or kidney stones may be permitted to fly in space. This could pose significant ethical and health implications if these risks are not mitigated among passengers on long-duration spaceflights.

Physical exercise, an established countermeasure to reduce—albeit not completely—the risk of bone loss and kidney stone formation, may not be feasible for lunar and capsule flights where space and resources are limited16. While several pharmacologic as well as other non-pharmacological countermeasures have been proposed, one of the biggest challenges may be identifying those at highest risk, perhaps by monitoring urinary calcium excretion. When bone loss occurs, urinary calcium excretion increases which can be measured and used to assess an individual’s level of bone resorption and risk of kidney stone formation in real time17,18. This can be used to guide frequency of non-pharmacological countermeasures or dosing of pharmacological measures like bisphosphonates or potassium citrate—both of which have dose-dependent effects and are currently being studied as potential countermeasures19,20. Therefore, by using urinary calcium excretion to identify high-risk populations, targeted countermeasures can be individualized in real-time.

Previous research on Earth has demonstrated that weight plays a role in influencing urinary calcium excretion, kidney stone formation, and bone mineral density21,22,23. While the mechanism has not yet been fully elucidated, greater body weight, waist circumference, and body mass index have all been associated with increased urinary calcium excretion, bone loss, and kidney stone formation risk in terrestrial studies10,22,24. However, there is a scarcity of literature identifying the relationship of body weight and urinary calcium excretion in space. Therefore, in this research, we examined data from the Skylab and ISS programs to assess the relationship between pre-flight weight and in-flight urinary calcium excretion.

Methods

Study design

Data from the Skylab and ISS programs were obtained from the Longitudinal Study of Astronaut Health (LSAH) database. All ISS data were de-identified, while the Skylab data had previously been published in identifiable form. This study was reviewed and approved by the National Aeronautics and Space Administration (NASA) and the Johnson Space Center (JSC) electronic Institutional Review Board (eIRB). Longitudinal in-flight 24 h urinary calcium excretion measurements (mg/day) were available for 9 and 36 individuals from the Skylab and ISS programs, respectively. For both programs, information on pre-flight weight (kg) was available. Pre-flight urinary calcium excretion measurements were only available for the Skylab program.

Statistical analyses

To test the effect of baseline urinary calcium excretion on in-flight urinary calcium excretion, we fit a linear mixed effects model using Skylab data only. Weight and day of flight were included as covariates, and subject identification (ID) was modeled as a random effect. We next examined the effect of pre-flight weight, day of flight, and their interaction on in-flight urinary calcium excretion using the combined Skylab and ISS data. We fit a linear mixed effects model that included program (Skylab/ISS) as a covariate and subject ID as a random effect. In both models, the random effect included both intercepts and slopes. All statistical analyses were performed in R. All statistical tests were two-sided and statistical significance was considered at p < 0.05.

Reporting summary

Further information on research design is available in the Nature Research Reporting Summary linked to this article.

Results

Data analyses

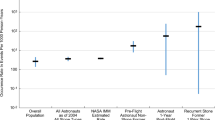

The mean in-flight urinary calcium excretion was 273 mg/day (SD = 100) for all 628 collections. The mean urinary calcium excretion was 281 mg/day (SD = 101) using Skylab data and 238 mg/day (SD = 90) for ISS data (Figs. 1, 2). Table 1 shows the characteristics of the dataset. Based on the model using Skylab data only, there was a statistically significant association between baseline urinary calcium excretion and urinary calcium excretion during flight controlling for pre-flight weight and day in flight (coefficient = 1.1; 95% CI: 0.47, 1.8; p = 0.018) (Fig. 3). In this model the effect of weight was not significant.

Using the combined dataset, we found a statistically significant association between pre-flight weight and urinary calcium excretion during flight (coefficient = 2.8; 95% CI: 0.38, 5.2; p = 0.029) (Table 2). The association between day in flight and urinary calcium excretion during flight approached significance (coefficient = 3.8; 95% CI: 0.21, 7.3; p = 0.055). The interaction term between pre-flight weight and day in flight also approached statistical significance (coefficient = −0.047, 95% CI: −0.093, −0.00095; p = 0.064). While the magnitude of the coefficient was small, the coefficient was negative, which could suggest that as time increases, the slope of the association between pre-flight weight and urinary calcium excretion during flight decreases, indicating that increased weight has a greater effect on urinary calcium excretion in the earlier days in flight.

Discussion

In this study, greater pre-flight body weight was associated with an increased risk of higher in-flight urinary calcium excretion. Increased body weight also showed a tendency to be associated with a more rapid rise in urinary calcium excretion. These findings suggest that passengers with an increased pre-flight body weight may be at an increased risk of bone loss and kidney stone formation than lower weight counterparts.

To the best of our knowledge, this is the first study that has identified pre-flight weight as a risk factor for increased in-flight urinary calcium. The findings of this study corroborate previous research evaluating factors influencing urinary calcium excretion among healthy terrestrial subjects, including body weight14,25,26,27. Weight loss can lead to bone resorption and decreased bone mineral density28,29,30. Those with higher baseline body weight are especially prone to this phenomenon31,32. Additionally, rapid as opposed to gradual weight loss potentiates this effect28,33. Weightlessness in space unloads the skeleton at a much more rapid rate and degree than weight loss does on Earth. In turn, it is possible that skeletal unloading from weightlessness may explain the relationship between weight and urinary calcium excretion observed in this study. Those with greater pre-flight weight may therefore be more prone to skeletal unloading and have a greater effect from reducing their skeletal load in weightlessness.

Previous research has shown that urinary calcium excretion can serve as a marker of bone loss and kidney stone risk while in space34,35,36. However, identifying which passengers may benefit from in-flight urinary calcium monitoring has not been well established. Based on the findings of this study, pre-flight medical screening for spaceflight passengers may incorporate body weight to select individuals for whom closer monitoring of urinary calcium levels may be useful while they are in microgravity.

While our findings suggest that higher weight is associated with increased urinary calcium excretion during flight, the effect was not profound. Based on this analysis, a 10 kg increase in body weight would translate into a 28 mg/day increase in urinary calcium excretion, which is an approximate 10% increase based on the average overall urinary calcium excretion. This suggests that other factors may play a more substantial role in influencing calcium excretion. Nevertheless, these results could provide useful information for risk stratification. For the same baseline level of urinary calcium excretion, a heavier individual may be running a higher risk of stone formation. While weight is a significant risk factor for kidney stones, many other factors including genetic predisposition, diet, and hydration, exist11. Therefore, weight alone may not reliably predict risk of kidney stones, bone loss, or urinary calcium excretion in space. Instead, weight may be used as one of the many factors that may need to be considered to establish an individual’s risk profile.

This study has some limitations. The amount of data available was limited and the number of individuals studied was small and may not reflect the population of commercial spacefarers. Full data on gender was not available. Further research with larger sample sizes is needed to validate the findings of this study since body weight is not the only factor affecting urinary calcium excretion. Additionally, the association between baseline urinary calcium excretion and urinary calcium excretion during flight was tested using measurements for only 9 individuals from the Skylab program because the ISS data did not contain data for pre-flight urinary calcium excretion. While we detected a statistically significant association between baseline urinary calcium excretion and in-flight urinary calcium excretion, the small sample size limited our statistical power to detect an association between pre-flight weight and in-flight urinary calcium excretion during flight using just the Skylab data. To test this association, we therefore combined Skylab and ISS data.

Combining data from the Skylab and ISS programs increased our sample size to 45 participants. This also created another limitation, namely that the two programs differ. There may be differences in diet and the use of exercise as a countermeasure to prevent bone loss in space, which could affect urinary calcium excretion during flight but are difficult to account for. We attempted to adjust for these differences statistically by controlling for mission in our model using the combined data, but residual confounding remains a possibility.

Finally, 19 out of 45 participants had 3 or fewer measurements, and 11 participants had only 1 or 2 measurements. As a result, individuals who could be considered outliers, for example individuals with relatively low weight but very high levels of baseline urinary calcium excretion levels, could have a fairly large impact on the results of our analysis given that we were not able to control for baseline urinary calcium excretion in the combined analysis. Despite these limitations, this study highlights the utility for using pre-flight weight for assessing the risk for increased urinary calcium excretion in space using actual space flight data. Higher weight individuals could be targeted for urinary calcium measurements in space.

The risk of bone loss and kidney stone formation are significant barriers that must be overcome for the future success of long duration spaceflight. This will be especially critical as the general population, including those with endogenous risk factors for increased urinary calcium excretion, will be traveling in space. Loss of bone mineral density leads to an increased risk of fractures as well as kidney stones—either of these events happening in-flight can be problematic or even detrimental in the resource-confined environment of spaceflight. Therefore, targeting individuals at an increased baseline risk for these issues with close monitoring of urinary calcium excretion can mitigate these adverse events. Small, low power, point-of-care devices are being developed that could make these measurements. Further research evaluating the efficacy of using body weight to reduce these risks is needed to validate the utility of using these factors in stratifying bone loss and kidney stone risk.

Data availability

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author, [ST], upon reasonable request.

Code availability

The code that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author, [ST], upon reasonable request.

References

Buckey J. C. Bone Loss: Dealing with Calcium and Bone Loss in Space. Space Physiology. 1–32 (Oxford University Press, New York 2006).

Orwoll, E. S. et al. Skeletal health in long-duration astronauts: Nature, assessment, and management recommendations from the NASA bone summit. J. Bone Min. Res. 28, 1243–1255, (2013).

Stavnichuk, M., Mikolajewicz, N., Corlett, T., Morris, M. & Komarova, S. V. A systematic review and meta-analysis of bone loss in space travelers. npj Microgravity 6, 1–9 (2020).

Nordin, B. E. C., Polley, K. J., Need, A. G., Morris, H. A. & Horowitz, H. Calcium and osteoporosis. Ann. Chir. Gynaecol. 77, 212–218 (1988).

Patel, Z. S. et al. Red risks for a journey to the red planet: The highest priority human health risks for a mission to Mars. npj Microgravity 6, 1–13 (2020).

Preventing Bone Loss in Space Flight | NASA [Internet]. [cited 2022 May 28]. Available from: https://www.nasa.gov/mission_pages/station/research/benefits/bone_loss.html.

El-Husseini, A. et al. Urinary calcium excretion and bone turnover in osteoporotic patients. Clin. Nephrol. 88, 239–247 (2017).

Whitson, P. A., Pietrzyk, R. A. & Pak, C. Y. C. Renal stone risk assessment during Space Shuttle flights. J. Urol. 158, 2305–2310 (1997).

Sibonga, J. D. Spaceflight-induced bone loss: Is there an osteoporosis risk? Curr. Osteoporos. Rep. 11, 92–98 (2013).

Pouresmaeili, F., Kamalidehghan, B., Kamarehei, M. & Goh, Y. M. A comprehensive overview on osteoporosis and its risk factors. Ther. Clin. Risk Manag. 14, 2029 (2018).

Shin, S., Srivastava, A., Alli, N. A. & Bandyopadhyay, B. C. Confounding risk factors and preventative measures driving nephrolithiasis global makeup. World J. Nephrol. 7, 129 (2018).

Siani, A., Iacoviello, L., Giorgione, N., Iacone, R. & Strazzullo, P. Comparison of variability of urinary sodium, potassium, and calcium in free-living men. Hypertens. (Dallas, Tex. 1979) 13, 38–42 (1989).

Spiegel, D. M. & Brady, K. Calcium balance in normal individuals and in patients with chronic kidney disease on low- and high-calcium diets. Kidney Int. 81, 1116–1122 (2012).

KNAPP, E. L. Factors influencing the urinary excretion of calcium; in normal persons. J. Clin. Invest. 26, 182–202 (1947).

Jennings, R. T. et al. Medical qualification of a commercial spaceflight participant: Not your average astronaut. Aviat. Sp. Environ. Med. 77, 475–484 (2006).

Genah, S., Monici, M. & Morbidelli, L. The effect of space travel on bone metabolism: Considerations on today’s major challenges and advances in pharmacology. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 22, 4585 (2021).

Issekutz, B., Blizzard, J. J., Birkhead, N. C. & Rodahl, K. Effect of prolonged bed rest on urinary calcium output. J. Appl. Physiol. 21, 1013–1020 (1966).

Seeger, H. et al. Changes in urinary risk profile after short-Term low sodium and low calcium diet in recurrent Swiss kidney stone formers. BMC Nephrol. 18, 1–9 (2017).

Baran, R. et al. Microgravity-related changes in bone density and treatment options: A systematic review. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 23, 8650 (2022).

Whitson, P. A. et al. Effect of potassium citrate therapy on the risk of renal stone formation during spaceflight. J. Urol. 182, 2490–2496 (2009).

Andersen, T., McNair, P., Fogh-Andersen, N. & Transbol, T. Calcium homeostasis in morbid obesity. Min. Electrolyte Metab. 10, 316–318 (1984).

Carbone, A. et al. Obesity and kidney stone disease: A systematic review. Minerva Urol. Nefrol. 70, 393–400 (2018).

Powell, C. R. et al. Impact of body weight on urinary electrolytes in urinary stone formers. Urology 55, 825–830 (2000).

Taylor, E. N., Stampfer, M. J. & Curhan, G. C. Obesity, Weight Gain, and the Risk of Kidney Stones. JAMA 293, 455–462 (2005).

Bevier, W. C. et al. Relationship of body composition, muscle strength, and aerobic capacity to bone mineral density in older men and women. J. Bone Min. Res. 4, 421–432 (1989).

Orozco, P. & Nolla, J. M. Associations between body morphology and bone mineral density in premenopausal women. Eur. J. Epidemiol. 13, 919–924 (1997).

Saleh, A. E. C. & Coenegracht, J. M. The influence of age and weight on the urinary excretion of hydroxyproline and calcium. Clin. Chim. Acta. 21, 445–452 (1968).

Hunter, G. R., Plaisance, E. P. & Fisher, G. Weight Loss and Bone Mineral Density. Curr. Opin. Endocrinol. Diabetes Obes. 21, 358 (2014).

Pines, A. Weight loss, weight regain and bone health. Climacteric 15, 317–319 (2012).

Shen, Z. et al. Weight loss since early adulthood, later life risk of fracture hospitalizations, and bone mineral density: a prospective cohort study of 0.5 million Chinese adults. Arch. Osteoporos. 15, 60 (2020).

Jensen V. F. H., Mølck A. M., Dalgaard M., McGuigan F. E., Akesson K. E. Changes in bone mass associated with obesity and weight loss in humans: Applicability of animal models. Bone 145, 115781 (2021).

Jiang, B. C. & Villareal, D. T. Weight Loss-Induced Reduction of Bone Mineral Density in Older Adults with Obesity. J. Nutr. Gerontol. Geriatr. 38, 100–114 (2019).

Soltani, S., Hunter, G. R., Kazemi, A. & Shab-Bidar, S. The effects of weight loss approaches on bone mineral density in adults: a systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Osteoporos. Int. 27, 2655–2671 (2016).

Iwamoto, J., Takeda, T. & Sato, Y. Interventions to prevent bone loss in astronauts during space flight. Keio J. Med. 54, 55–59 (2005).

Ren, J. et al. Urinary calcium for tracking bone loss and kidney stone risk in space. Aerosp. Med Hum. Perform. 91, 689–696 (2020).

Vermeer C., Wolf J., Craciun A., Knapen M. Bone markers during a 6-month space flight: effects of vitamin K supplementation. undefined. 1998.

Acknowledgements

This research was supported by NASA Grant 80NSSC19K1632. We thank the NASA office of the Life Sciences Data Archive for their time in providing the dataset used in this study.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

This manuscript has been read and approved by all authors and all authors are named in this submission for their contributions. S.T., M.S., and J.B. were involved in research design as well as the writing of this manuscript. S.T. was the leading author. M.S. was the primary statistician who conducted most of the statistical analysis. S.T. and J.B. had the primary responsibility for final content.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons license and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Thamer, S., Stevanovic, M. & Buckey, J.C. Pre-flight body weight effects on urinary calcium excretion in space. npj Microgravity 9, 45 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41526-023-00291-2

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41526-023-00291-2