Abstract

In conditions of microgravity the human body undergoes extensive alterations in physiological function. However, it has proven challenging to determine how these changes are mediated at the molecular and cellular level. Here, we investigated whether ELKIN1, a mechanically activated ion channel, regulates changes in cellular and molecular structures in conditions of simulated microgravity. Deletion of ELKIN1 inhibited the simulated microgravity-induced alterations of cellular structure and attachment. In addition, cells lacking ELKIN1 did not exhibit changes in focal adhesion structures and redistribution of the YAP1 transcription factor in response to simulated microgravity, consistent with wild type cells. Finally, melanoma cell invasion of a collagen gel, from organotypic spheroids, was reduced in simulated microgravity, in an ELKIN1 dependent manner. Thus, the force sensing molecule, ELKIN1, modulates the impact of microgravity at both the molecular and cellular levels, revealing one of the molecular mechanisms that underpins cellular adaptations to conditions of microgravity.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Despite the omnipresent influence of the planet’s gravitational vector during the evolution of life, Earth based biology is remarkably resilient in the absence of gravitational loading. However, while humans and other organisms can survive for extended periods under conditions of microgravity, significant alterations in human physiology accrue with increasing time spent in reduced gravity environments. These changes include redistributions in blood flow, alterations in immune function, bone and muscle wastage, and increased lytic disruption of erythrocytes that occur over time1,2. While there are additional stressors experienced by those who spend extended periods of time in space2, many of the observed changes in physiology are linked to physiological systems in which force sensing is an essential aspect of normal function, but active use of the gravitational stimulus is not3.

The ability of cells to sense various aspects of their mechanical environment is fundamentally important for many aspects of mammalian physiology. For instance, the rapid conversion of an external force to an electrical signal underpins our senses of touch and hearing; pressure and stretch sensing are important for proper function of the renal, respiratory and vascular systems and cellular sensing of changing mechanical load is essential for the proper maintenance of bone and cartilage3. In addition, some cells can probe the mechanical properties of their surroundings by applying contractile forces at cell-substrate contacts, a process that can regulate cellular differentiation4,5, wound healing6 and cancer cell metastasis7,8,9,10. The force sensing mechanisms and signalling pathways that regulate human physiology have all evolved under the persistent impact of Earth’s gravitational field, defined as 1 g.

The ability of cells to convert mechanical inputs into biochemical signals is known as mechanotransduction, a broad term that encapsulates the action of multiple force sensing mechanisms and the signal transduction pathways that sit downstream of these mechanically responsive molecules and structures. Forces can be propagated from the extracellular environment, directly to the nucleus via cytoskeletal structures11,12,13, cell attachment proteins, such as integrins14,15,16 and cadherins17,18 have been shown to play important roles in cellular mechanosensing and strain gauge proteins such as Talin19 and Zyxin20,21 reversibly deform under load, regulating molecular interactions and influencing downstream signalling22. However, the most ancient of force sensing molecules are the mechanically activated (MA) ion channels, pore forming proteins that are activated by mechanical inputs.

Much of the research into MA ion channels has been dedicated to the identification of these force sensing molecules and how their function influences the balance between physiological and pathophysiological states. However, given that all life on Earth has evolved under the persistent influence of the planet’s gravitational vector, it is important to consider if mechanical signalling via MA channels will be impacted in reduced gravitational environments, such as the microgravity (1 ×10-3 to 1 ×10-5 g) experienced on the International Space Station (ISS) or the low gravity of Luna, Earth’s moon (0.166 g). Recent studies utilising hindlimb unloading in rodents to simulate microgravity have revealed a role for Piezo1, the best characterised mammalian MA ion channel, in regulating bone loss23,24 and alterations in the carotid artery reminiscent of aging-like pathologies25. These data suggest that the investigation of the role of MA channels in cellular adaptations in microgravity is warranted.

Studies that have investigated the impact of the application of microgravity (either real or simulated) to isolated cells have reported reorganisation of cytoskeletal structures26,27,28, changes in cell morphology29,30,31,32 and attachment30,33,34,35 and alterations in gene expression34 as well as changes in cell adhesion and signal transduction molecules36,37. Alterations in cytoskeletal structures (assessed qualitatively) and the detachment of cells from two dimensional (2D) substrates have been the most consistently observed outcomes when cells are exposed to real or simulated microgravity.

We hypothesise that these changes in cell and molecular structure may be influenced by MA channel function. To investigate this question, we have conducted studies using simulated microgravity applied to melanoma cells (Fig. 1). This experimental design was chosen to enable cost-effective, ground-based studies where the microgravity state is simulated using a random positioning machine (RPM). Samples mounted in the RPM are subjected to random reorientation, relative to the orientation of the gravity vector, thus resulting in an average gravity zero vector, over time38. Melanoma cells were selected for study, given their high degree of mechanosensitivity, common to many cancer cell types. Here, we have focussed on the impact of the mechanically gated channel, ELKIN1 (TMEM87a)7,39: in melanoma cells, this novel force sensor has previously been demonstrated to regulate cell migration, cell dissociation from organotypic spheroids and cellular attachment properties7. In sensory neurons, ELKIN1 acts as one of the touch receptors involved in gentle touch perception39. We have previously created knockout cell lines, lacking ELKIN17,40, and here we have used those cells to test whether ELKIN1 influences aspects of the cellular adaptations that occur in simulated microgravity. We have investigated whether deletion of ELKIN1 modulates cell attachment and morphology and whether force sensing structures and mechanically regulated transcription factors are differentially impacted by simulated microgravity when ELKIN1 is absent.

To conduct ground-based studies, we have used an RPM to simulate microgravity. A Schematic of the RPM prior to experiment, with the two rotational arms in orange and blue. When static, the sample plate (blue) is consistently orthogonal relative to the direction of the gravitational vector (g), lower insert. B The RPM experiments were conducted inside a cell culture incubator, maintaining conditions of 37°, 5% CO2. To analyse the impact of simulated microgravity, duplicate samples were prepared, one placed next to the RPM in the incubator, the other on the sample plate in the central axis of the RPM device (blue). The RPM then rotates the sample through the two independent axes (indicated by orange and blue arrows). This movement continually reorients the sample relative to the gravitational vector, resulting in an average zero gravity vector acting on the sample, over time (lower insert).

Results

Deletion of ELKIN1 inhibits simulated microgravity induced cell detachment

Adherent cells detach from their underlying substrate in response to treatment with microgravity (real or simulated)28,30,31,32,34. To investigate whether ELKIN1 influences the impact of microgravity on cells cultured under 2D conditions, we first assessed changes in the number of adherent melanoma cells, after the application of simulated microgravity. Wild type and ELKIN1-KO cells derived from the WM266-4 cell line were treated with either 4 or 16 h of simulated microgravity. After treatment, cells were fixed and labelled with Hoechst, the number of stained nuclei were counted as a proxy for cell number and data normalised against the control samples that had been incubated at 1 g (Fig. 2A–D). The number of WT cells adhered to the substrate was significantly lower after 4 h of microgravity, compared with the corresponding 1 g controls (Fig. 2E). In contrast, no significant reduction in the number of ELKIN1-KO cells was noted after 4 h simulated microgravity, compared to the relevant 1 g control. These observations were confirmed in additional WT and ELKIN1-KO clones, indicating that this impact cannot solely be attributed to clonal effects. In further support of the role of ELKIN1 in this process, the detachment of cells from the substrate in simulated microgravity after 4 h was rescued in ELKIN1-KO cells stably expressing ELKIN1-isoform 1-mGFP. A qualitative assessment of ELKIN1-isoform 1-mGFP distribution in cells attached to the substrate after treatment with 4 h simulated microgravity did not reveal alterations in the distribution of ELKIN1-isoform 1, in comparison with controls (Supplementary Fig. 1). ELKIN1-isoform 1 remains localised to the Golgi, and in puncta in the plasma membrane, as previously described for melanoma7 and other cell types39,41. After 16 h there was a reduction in the number of ELKIN1-KO cells adhered to the substrate, however, the impact of simulated microgravity on ELKIN1-KO cell attachment was more moderate than that noted for WT cells after 16 h treatment.

Sample images of Hoechst-stained nuclei obtained from WT-3B6 1 g control (A), WT-3B6 16 h microgravity (B), E1KO-3C6 1 g control (C) and E1KO-3C6 16 h microgravity (D). Scale bar = 200 µm. E–G Data from each sample were normalised to the mean average of the respective control for each individual experiment and plotted as individual data points. E After 4 h, a significant decrease in adherent cell number was observed in WT-3B6 cells treated with microgravity compared to WT-3B6 controls, whereas no significant difference was seen between ELKIN1-KO (E1KO)-3C6 control and E1KO-3C6 microgravity This result was recapitulated with additional WT (WT-3E9) and E1KO (E1KO-3D6) clones. (Kruskal-Wallis with uncorrected Dunn’s test, WT-3B6 control; n = 21, WT-3B6 microgravity; n = 20, ***p-value = 0.0004; E1KO-3C6 control; n = 20; E1KO-3C6 microgravity; n = 17 wells, ns p-value = 0.16; WT-3E9 control; n = 9, WT-3E9 microgravity; n = 9, **p = 0.007; E1KO-3D6 control, n = 8; E1KO-3D6 microgravity; n = 7, ns p-value = 0.19). F After 4 h, the impact of microgravity could be rescued by overexpression of ELKIN1-isoform 1 in E1KO-3C6 cells, with a significant reduction in cells expressing ELKIN1-isoform1 adhered to the surface after treatment with microgravity (Kruskal-Wallas with uncorrected Dunn’s test, E1KO-3C6 control; n = 7; E1KO-3C6 microgravity; n = 9, ns p-value = 0.86; E1KO-3C6-ELKIN1-iso1 rescue control; n = 8; E1KO-3C6-ELKIN1-iso1 rescue microgravity; n = 9, **p = 0.002). G After 16 h, a significant decrease in adherent cell numbers was observed in WT-3B6 microgravity compared to WT-3B6 control groups and a mild yet significant difference was seen between E1KO-3C6 control and E1KO-3C6 microgravity groups (Kruskal-Wallis with uncorrected Dunn’s test, WT-3B6 control; n = 13, WT-3B6 microgravity, ****p-value < 0.0001; n = 14, E1KO-3C6 control; n = 13; E1KO-3C6 microgravity; n = 13 wells, *p-value = 0.0495). Each data point denotes an individual sample well. The line underlying individual data points indicates sample median.

Moderate changes in cell morphology in response to simulated microgravity are regulated by ELKIN1

We next assessed whether ELKIN1 expression influenced the morphology of the remaining adhered cells after microgravity treatment. A change in the cytoskeleton of cells exposed to microgravity has frequently been reported26,27,28. We initially imaged fluorescently labelled actin structures in cells treated with simulated microgravity (Supplementary Fig. 2). Actin stress fibres are visible in WT and ELKIN1-KO cells, both at 1 g and post treatment with simulated microgravity. A subset of cells were characterised by disorganised actin. Published data has shown that melanoma cells exhibit not only stress fibres but also surface structures that depend on submembranous actin42,43. As such, quantifying alterations in the actin cytoskeleton is non-trivial, given the heterogeneity of actin-based structures in these cells. As an alternative, we used alterations in cell morphology as an integrated proxy for alterations in cells structure, that in-part depend on the cytoskeleton. Cells expressing a fluorescent membrane label were imaged using laser scanning confocal microscopy and 3D reconstructions of cell shape were generated from the resulting image stacks (Fig. 3A–F). The ratio of cell surface area to cell volume was calculated as an indicator of cell size. After 4 h of simulated microgravity, no changes were noted in the cell area/volume ratio for either sample (Fig. 3G). However, after 16 h of simulated microgravity, the WT cells exhibited a significantly lower cell area/volume ratio, suggesting an increase in cell size (Fig. 3H). The cell aspect ratio was also assessed, as an indication of cell elongation: a decrease in cell elongation was noted for WT samples treated with simulated microgravity for 4 h (Fig. 3I). This effect was lost after 16 h of treatment with microgravity (Fig. 3J), suggesting that either an adaptation process or that the detachment of a large proportion of cells (Fig. 2) left an unresponsive population adhered to the surface. However, given the noted change in cell surface area: volume ratio after 16 h, it is clear that the remaining cells have not completely adapted to ongoing conditions of simulated microgravity. In contrast to these alterations in the morphology of WT cells, no significant changes were observed in either cell surface area: cell volume nor the cell aspect ratio in ELKIN1-KO cells treated with simulated microgravity for either 4 or 16 h.

Representative examples of surface masks generated from confocal image stacks of WM266-4: WT-3B6 controls (A) and post exposure to 4 h (B) or 16 h simulated microgravity (C) and WM266-4 E1KO-3C6 cells under normal gravity conditions (control, D) or post exposure to 4 h (E) or 16 h simulated microgravity (F). Scale bar = 15 μm. G, H Cell Area/Volume ratio calculated from 3D image reconstructions. (G) No differences were noted between control and samples treated with simulated microgravity for 4 h (Kruskal-Wallis with uncorrected Dunn’s comparison, WT-3B6 control; n = 53, WT-3B6 microgravity; n = 35, p > 0.9999; E1KO-3C6 control = 59, E1KO-3C6 microgravity = 51, p = 0.3). H When simulated microgravity was applied for 16 h, the treated WT cells exhibited a significantly smaller Cell Area/Volume ratio, but there was no difference between E1KO cells from the control group versus the sample treated with simulated microgravity (One way ANOVA with uncorrected Fisher’s LSD, WT-3B6 control; n = 33, WT-3B6 microgravity; n = 40, ***p = 0.001; E1KO-3C6 control = 27, E1KO-3C6 microgravity = 30, ns p = 0.84). I, J The cell aspect ratio was calculated from 3D image reconstructions. I WT-3B6 control cells exhibited a significantly reduced cell-aspect ratio in comparison to WT-3B6 cells treated with microgravity but E1KO-3C6 cells did not differ in cell-aspect ratio between the two conditions (Kruskal-Wallis with uncorrected Dunn’s comparison, WT-3B6 control; n = 53, WT-3B6 microgravity, *p = 0.048; n = 35, E1KO-3C6 control = 59, E1KO-3C6 microgravity = 51, ns p = 0.70). J After 16 h of simulated microgravity no significant differences in cell aspect ratio were noted (Kruskal-Wallis with uncorrected Dunn’s comparison, WT-3B6 control; n = 33, WT-3B6 microgravity; n = 40, ns p = 0.14; E1KO-3C6 control = 27, E1KO-3C6 microgravity = 30, ns p = 0.30). Each data point denotes a single cell, the line underlying individual data points represents the sample median.

Focal adhesion size and composition is altered in simulated microgravity

We next assessed whether ELKIN1 regulated changes in cell attachment structures due to treatment with simulated microgravity. Melanoma, and other adherent cells, form FA complexes when cultured on tissue culture plastic or glass. These structures are multi-molecular complexes of attachment, signalling and mechanoresponsive proteins that mediate both binding to the subjacent surface and the transduction of information encoded in mechanical cues from the substrate44. To assess whether core elements of these FA structures change in response to simulated microgravity, we labelled Paxillin and Zyxin, using post-fixation antibody staining (Fig. 4A–D), and measured the size of domains formed by these molecules at the cell periphery (structures localised within 10 µm of the edge of the cell). The ratio between the Zyxin and Paxillin defined domains was utilised to determine if FA size and Zyxin recruitment changes occur independently of each other. We found that after 4 h simulated microgravity, there was no change in FA size in the WT cells, as determined from the Paxillin defined domains (Fig. 4E). In contrast, the Zyxin defined domains were smaller in the WT treated with 4 h simulated microgravity (Fig. 4F), and thus there was also a significant difference in the Zyxin: Paxillin area ratio (Fig. 4G). These data indicate that, in WT cells, the application of 4 h microgravity does not change the size of Paxillin domains, but does reduce the recruitment of Zyxin to those structures. When we assessed the changes in these domains in ELKIN1-KO cells, we noted that the size of Paxillin domains was increased after 4 h simulated microgravity (Fig. 4E), compared to ELKIN1-KO 1 g controls. There was a concomitant increase in the size of the Zyxin defined domains, however the ratio between the two was not significantly different (Fig. 4F-G). These data suggest that, over 4 hr, simulated microgravity can lead to larger FAs in ELKIN1-KO cells but does not alter the recruitment of Zyxin (in contrast to WT cells). The impact of microgravity on Paxillin and Zyxin-defined FA domains was rescued by overexpression of ELKIN1-isoform1-mGFP in ELKIN-KO cells (Supplementary Figure 3). When cells were treated for 16 h with simulated microgravity, no changes in Paxillin or Zyxin defined domains were detected in the WT cells (Fig. 4H–J). As mentioned above, these data may reflect either an adaptation to the change in gravitational loading or that the remaining cells adhered to the surface were simply less responsive. For the ELKIN1-KO cells, the Zyxin domains appeared larger after 16 h simulated microgravity, indicating that more Zyxin was being recruited to FA structures.

Representative images of Paxillin and Zyxin structures in WM266-4 WT-3B6 controls (1 g, A) and post exposure to 4 h simulated microgravity (RPM, B) and WM266-4 E1KO-3C6 cells under normal gravity conditions (1 g, C) or post exposure to 4 h simulated microgravity (RPM, D). Single channel images are presented as inverted grey scale. An overlay image, (Paxillin in green and Zyxin in magenta) is presented, alongside an inset that corresponds to the marked region in the overview image. Scale bar = 10 µm or 5 µm, as indicated. E–G Quantification of adhesion structure sizes defined by Paxillin and Zyxin staining, after exposure to 4 h simulated microgravity. E The Paxillin defined FA domains did not significantly vary in size in response to 4 h simulated microgravity in WT-3B6 cells. However, in E1KO-3C6 cells, these structures are significantly larger after application of 4 h simulated microgravity (Kruskal-Wallis with uncorrected Dunn’s test; WT-3B6 control; n = 330, WT-3B6 microgravity, n = 368, ns p = 0.21; E1KO-3C6 control = 324, E1KO-3C6 microgravity = 199, **p = 0.005). F After 4 h simulated microgravity, the Zyxin-defined FA domains were significantly smaller in WT cells but significantly larger in E1KO cells (Kruskal-Wallis with uncorrected Dunn’s test; WT-3B6 control; n = 330, WT-3B6 microgravity; n = 368, *p = 0.012; E1KO-3C6 control = 362, E1KO-3C6 microgravity = 199, **p = 0.006,). G When the ratio of Zyxin to Paxillin area was determined for each FA structure, this ratio was significantly decreased in WM-WT cells post application of 4 h simulated microgravity, but remained unchanged in WM-E1KO cells (Kruskal-Wallis with uncorrected Dunn’s test; WT-3B6 control; n = 330, WT-3B6 microgravity; n = 368, **p = 0.001; E1KO-3C6 control = 363, E1KO-3C6 microgravity = 199, ns p = 0.45). H–J Quantification of adhesion structure sizes defined by Paxillin and Zyxin staining, after exposure to 16 h simulated microgravity. H The Paxillin defined FA domains did not significantly vary in size after application of 16 h simulated microgravity in WT or E1KO cells (Kruskal-Wallis with uncorrected Dunn’s test; WT-3B6 control; n = 246, WT-3B6 microgravity, n = 222, ns p = 0.29; E1KO-3C6 control = 232, E1KO-3C6 microgravity = 451, ns p = 0.45). I After 16 h simulated microgravity applied to WT cells, the Zyxin-defined FA domains not significantly different in comparison with 1 g controls. However, Zyxin-defined domains at the cell periphery were significantly larger in E1KO cells treated with simulated microgravity, in comparison with 1 g controls (Kruskal-Wallis with uncorrected Dunn’s test; WT-3B6 control; n = 240, WT-3B6 microgravity; n = 222, ns p = 0.16; E1KO-3C6 control n = 274, E1KO-3C6 microgravity n = 464, **p = 0.009). J When the ratio of Zyxin to Paxillin area was determined for each FA structure, this ratio remained unchanged in WT cells treated with 16 h microgravity, in comparison with 1 g controls. In contrast, the ratio of Zyxin to Paxillin area was significantly decreased in E1KO cells treated with 16 h of simulated microgravity, in comparison with 1 g controls (Kruskal-Wallis with uncorrected Dunn’s test; WT-3B6 control; n = 238, WT-3B6 microgravity; n = 222, ns p = 0.14; E1KO-3C6 control; n = 232, E1KO-3C6 microgravity; n = 451, ***p = 0.0002). Each data point denotes an individual focal adhesion, the line underlying individual data points corresponds to the sample median.

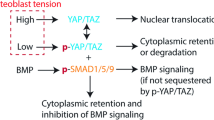

Simulated microgravity leads to a reduction in nuclear localisation of YAP1 in a process dependent on ELKIN1

The YAP1 transcriptional activator is often used as a proxy for assessing integrated changes in mechanical signalling45,46,47. The YAP1 protein shuttles between cytoplasm and nucleus, with an increase in nuclear staining corresponding to an increase in mechanical loading of the cells. To assess if ELKIN1 expression dictates YAP1 localisation in melanoma cells treated with simulated microgravity, we assessed the relative levels of nuclear YAP1: cytoplasmic YAP1 from wide field images of cells labelled with anti-YAP1 antibody45. Given that YAP1 nuclear localisation can also be influenced by cell density45, these experiments were conducted with fewer cells in each sample (5 × 103 cells added to each well), so that the sample consisted of individual cells. The application of 4 h of simulated microgravity to WT cells resulted in a reduction in the relative amount of YAP1 staining in the nucleus (Fig. 5A, B, E, F). In contrast, the nuclear to cytoplasmic ratio of YAP1 labelling in ELKIN1-KO cells did not differ after 4 h of simulated microgravity. The impact of simulated microgravity on YAP1 translocation to the nucleus could be rescued by over-expression of ELKIN1-isoform1-GFP in the ELKIN1-KO cells (Fig. 5C, D). However, it is clear that overexpression of ELKIN1-isoform1 impacts YAP1 nuclear localisation under conditions of 1 g. Namely, high levels of ELKIN1 expression led to a reduction in YAP1 nuclear localisation, compared to the WT cells. This observation likely reflects a role for ELKIN1 in regulating YAP1 localisation under both standard conditions and in simulated microgravity. When WT and ELKIN1-KO cells were exposed to simulated microgravity for 16 h, the impact on YAP1 localisation was consistent with the data obtained after 4 h simulated microgravity (Fig. 5E, F). These data suggest that ELKIN1 is required for the microgravity-dependent changes in YAP1 localisation.

Representative images of YAP1 localisation in WM266-4 cells: WT-3B6 controls (1 g, A) and post exposure to 4 h simulated microgravity (RPM, B) and WM266-4 E1KO-3C6 cells under normal gravity conditions (1 g, C) or post exposure to 4 h simulated microgravity (RPM, D). Scale bar = 20 µm. Note all images presented were from the same technical replicate, and were obtained during the same imaging session. E, F Quantification of the ratio of nuclear YAP1: cytoplasmic YAP1 staining. After 4 hr (E) of simulated microgravity applied to WT cells, the ratio of YAP1 staining in the nucleus, in relation to YAP1 staining in the cytoplasm, was significantly reduced compared to 1 g controls, however no significant differences were noted for E1KO samples treated with microgravity. When ELKIN1-isoform 1 was overexpressed in the E1KO cells, the effect on the relative amount of YAP1 in the nucleus was rescued and a significantly lower ratio of nuclear YAP1: cytoplasmic YAP1 was observed (Kruskal-Wallis with uncorrected Dunn’s test; WT-3B6 control (4 h); n = 123; WT-3B6 microgravity (4 h); n = 65 ****p < 0.0001; E1KO-3C6 control (4 h); n = 68; E1KO-3C6 microgravity (4 h); n = 156 ns p = 0.062; E1KO-3C6-ELKIN1-iso1 control (4 h); n = 29; E1KO-3C6-ELKIN1-iso1 microgravity (4 h), n = 21 ****p < 0.0001). F When simulated microgravity was applied for 16 h, the reduction in YAP1 in the nucleus was observed in WT cells, but not E1KO cells, compared to 1 g controls (Kruskal-Wallis with uncorrected Dunn’s test; WT-3B6 control (16 h); n = 146, WT-3B6 microgravity (16 h); n = 142 ****p < 0.0001; E1KO-3C6 control (16 h): n = 104; E1KO-3C6 microgravity (16 h), n = 69 ns p = 0.267). G Quantification of the ratio of nuclear YAP1: cytoplasmic YAP1 staining in A375-MA2 melanoma cell lines. After 4 h of simulated microgravity WT cells exhibited reduced YAP1 staining in the nucleus (Kruskal-Wallis with uncorrected Dunn’s test; WT control (4 h); n = 26; WT microgravity (4 h); n = 39 ****p < 0.0001) but no difference in relative levels of nuclear YAP1 was detected when E1KO cells were treated with simulated microgravity (E1KO control (4 h); n = 29; E1KO microgravity (4 h); n = 65 ns p = 0.23). Deletion of PIEZO1 (P1KO) led to a reduction in relative nuclear YAP1 staining under conditions of 1 g, compared to WT cells, and the application of simulated microgravity led to an increase in the relative amount of YAP1 in the nucleus (P1KO control (4 h); n = 40, P1KO microgravity (4 h); n = 48 ****p < 0.0001). In cells where both PIEZO1 and ELKIN1 have been knocked out (E1P1KO), no significant difference was noted in relative YAP1 localisation, after application of simulated microgravity, a phenocopy of the E1KO cell effect (Kruskal-Wallis with uncorrected Dunn’s test; E1P1KO control (4 h); n = 48; E1P1KO microgravity (4 h); n = 66 ns p = 0.73).

Given the potential significance of this observation, we assessed YAP1 nuclear localisation in a second melanoma cell line, A375-MA2. The A375-MA2 cells were subjected to 4 h of simulated microgravity and the WT A375-MA2 cells exhibited a similar reduction in the relative amount of nuclear localised YAP1 (Fig. 5G), recapitulating the data generated using the WM266-4 WT cells (Fig. 5E). The ELKIN1-KO clone derived from the A375-MA2 cells also recapitulated the data obtained in the WM266-4 background, i.e. the application of simulated microgravity did not lead to significant changes in the relative amount of nuclear YAP1. The A375-MA2 cells also express the MA channel, PIEZO148 (a molecule that is lacking in WM266-4 cells). Under conditions of 1 g, the A375-MA2 PIEZO1-KO cells exhibit significantly lower relative nuclear YAP1 levels, compared to the WT controls. Thus, these cells exhibit a distinct starting condition, compared to WT cells under conditions of 1 g. Interestingly, when A375-MA2 PIEZO1-KO cells were treated with 4 h simulated microgravity, the relative amount of YAP1 in the nucleus was increased, compared to the 1 g control. These data indicate that PIEZO1 regulates YAP1 localisation under standard gravity conditions in these melanoma cells. The inversion of the relative ratio of nuclear YAP1: cytoplasmic YAP1 in the PIEZO1-KO cells under conditions of 1 g and simulated microgravity, compared to WT cells, suggests that the loss of PIEZO1 alters mechanical signalling differentially under these two distinct conditions. A double knockout of ELKIN1 and PIEZO1 in the A375-MA2 cells phenocopied the ELKIN1-KO result: similar relative amounts of YAP1 in the nucleus under conditions of 1 g and no changes in the relative amount of nuclear YAP1 noted after application of simulated microgravity. These data indicate that mechanoelectrical transduction regulates downstream mechanical signalling and that ELKIN1 deletion in two distinct cell lines blocks microgravity-induced alterations in YAP1 localisation. In addition, YAP1 localisation in ELKIN1-PIEZO1 double knockout cells suggests that, in 1 g, deletion of ELKIN1 overrides the impact of PIEZO1 deletion. Finally, these data suggest that ELKIN1 and PIEZO1 exert distinct impacts on YAP1 shuttling under conditions of microgravity.

Simulated microgravity inhibits melanoma cell dissociation from organotypic spheroids, in a manner regulated by ELKIN1

We have clearly demonstrated that the impacts of simulated microgravity on cell attachment, cell morphology, cell attachment structures and the localisation of important mechanical signalling molecules are all abrogated or altered when the ELKIN1 molecule is deleted from these cells. However, one limitation of these data is that these experiments were all conducted on cells cultured in 2D on tissue culture plastic or glass. These culturing conditions influence signalling via mechanotransduction pathways and will impact how the cells experience the change in mechanical loading due to weightlessness. We therefore capitalised on an assay that we have previously used to assess the dissociation of melanoma cells from an organotypic spheroid embedded in a three dimensional (3D) collagen gel7, to determine if ELKIN1 expression influences microgravity-induced changes in cell behaviour in 3D environments. Organotypic spheroids were formed from either WM266-4 WT or ELKIN1-KO cells and implanted in collagen gels. Parallel spheroids were prepared for fixation at time 0 h (when spheroids were embedded), after 24 h simulated microgravity and after 48 h simulated microgravity (Fig. 6A-J). These longer incubation times were chosen to allow for sufficient dissociation of WT cells under conditions of 1 g, as previously defined7. For spheroids formed from WT cells, there was a significant reduction in the number of cells that had dissociated from the spheroid after 24 and 48 h simulated microgravity, in comparison with 1 g controls (Fig. 6K, L). These data indicate that the WT melanoma cells are less likely to invade the surrounding matrix under conditions of simulated microgravity. Our previous work has shown that the ELKIN1-KO cells are significantly more likely to dissociate from spheroids, compared to WT cells, under conditions of 1 g7. After 24 h of simulated microgravity, the number of dissociated cells counted for the ELKIN1-KO cells was indistinguishable from the ELKIN1-KO 1 g controls (Fig. 6K). However, there was a slight reduction in the number of ELKIN1-KO cells that had dissociated from the spheroid after 48 h of simulated microgravity, compared to the matched 1 g controls (Fig. 6L). These data were confirmed by assessing the size of the invasion front in a second set of clones (Supplementary Fig 4). In addition, these spheroids were stained for Ki67, to assess whether the alterations in invasion are due to differences in cell proliferation. No significant differences were noted in proliferation when spheroids were treated with simulated microgravity for 48 h (Supplementary Fig 4). These data suggest that simulated microgravity reduces melanoma cell invasion, in a manner that is partially regulated by ELKIN1.

Example images of organotypic spheroids formed from WT-3B6 (A–E) or E1KO-3C6 (F–J) cells embedded in a collagen I gel. A reference image of a spheroid at Time0 is presented for each cell type in A and F, Hoechst labelled nuclei are presented in blue and phalloidin staining of actin to label cells in magenta. The example images suggest that the application of microgravity to WT cells reduces spheroids size the amount of cell invasion after 24 (B, D) and 48 h (C, E). In contrast, the invasion of the collagen gel by cells dissociating from E1KO spheroids appear similar in both 1 g controls and microgravity treated samples (F–J). The number of cells dissociated were quantified after 24 h treatment (K) and 48 h treatment (L). Data are presented as normalised against the respective 1 g controls. K After 24 h of simulated microgravity, significantly fewer cells had dissociated from the WT spheroids, compared to 1 g controls, however no significant difference was noted for E1KO spheroids (Kruskal-Wallis with uncorrected Dunn’s test; WT-3B6 control (24 h); n = 11; WT-3B6 microgravity (24 h); n = 12 ***p = 0.0003; E1KO-3C6 control (24 h); n = 11; E1KO-3C6 microgravity (24 h); n = 12 ns p = 0.519). L After 48 h simulated microgravity, fewer cells had dissociated from the treated WT spheroids and the treated E1KO spheroids, compared to the respective 1 g controls (Kruskal-Wallis with uncorrected Dunn’s test; WT-3B6 control (48 h); n = 10; WT-3B6 microgravity (48 h); n = 9 *p < 0.036; E1KO-3C6 control (48 h); n = 11; E1KO-3C6 microgravity (48 h); n = 9 *p = 0.027).

Discussion

It is challenging to dissect the underlying mechanisms by which cells are impacted by changes in gravity. These challenges arise, in part, because cellular mechanotransduction is a complex process. Here, we studied whether ELKIN1, an ion channel involved in force sensing in melanoma cells7 and sensory neurons39, can influence cellular adaptations to simulated microgravity. The WT cells used in this study exhibited the commonly reported cell detachment from 2D culture substrates and the fraction of cells that remained adhered to the substrate underwent changes in size and morphology when treated with simulated microgravity. These effects were mitigated in ELKIN1-KO cells, highlighting a role for ELKIN1 in cellular adaptation to conditions of microgravity. These data also suggest that the commonly reported cell detachment and alterations in cellular structure are influenced by channel-mediated, force sensing pathways.

Previous data have shown that ELKIN1 dependent currents are activated at the contacts between cells and their microenvironment7. Within this cellular compartment there are additional force sensing structures, FAs, that help mediate links between the extracellular environment and the intracellular actin-based cytoskeleton. FAs are structured domains containing attachment, scaffolding, force sensing and signalling molecules44 and their size is mechanically regulated, with larger FA domains (including Paxillin-defined domains) forming on harder substrates49. This impact of substrate stiffness on FA size is dependent on retrograde actin flow50,51. In contrast, the redistribution and recruitment of some FA proteins, including Zyxin, is dependent on the application of tensile forces, substrate stretch or shear52,53,54. Previous studies have reported a reduction in the number of FAs formed in melanoma cells treated with simulated microgravity37, however little data is available on whether the size of FA domains is altered in microgravity or whether force-sensitive recruitment of proteins such as Zyxin to FAs is altered.

The WT cells studied here did not display alterations in the size of FAs, as defined by the size of Paxillin domains. These data suggest that simulated microgravity does not influence retrograde actin flow, in contrast to the broad, frequently reported impact of microgravity on actin stress fibres28. However, significantly smaller Zyxin domains were associated with these FAs, suggesting that the stress fibre-mediated, tension dependent localisation of Zyxin is impacted by simulated microgravity. In contrast, in the ELKIN1-KO cells, both the Paxillin and Zyxin defined domains were larger after the application of simulated microgravity for 4 hr, but the ratio of the two remained the same. These interesting data suggest that the lack of ELKIN1 leads to perturbation of the control of FA formation and tension-based changes in Zyxin defined domains. Thus, in WT cells, ELKIN1 positively regulates loading-dependent changes in Zyxin localisation, but negatively regulates the size of FAs. However, there appear to be additional counter mechanism(s) that function to increase the size of FAs, particularly in conditions of simulated microgravity, that are apparent when ELKIN1 is lacking. We postulate that in WT cells, ELKIN1 helps maintain FA size and simultaneously negatively regulates the amount of Zyxin in FA structures under conditions of simulated microgravity. Our data also suggest that individual elements of FAs are differentially impacted by microgravity and ELKIN1. Given the molecular and structural complexity of FAs44, future studies will be necessary to further tease apart which individual elements of these attachment, mechanosensing and signalling platforms are a) modulated by microgravity and b) dependent on ELKIN1.

In addition to these structural changes in mechanosignalling hubs at the cell-substrate interface we noted downstream alterations in mechanical transduction. YAP1 is a transcriptional co-regulator known to be involved in the conversion of mechanical information into alterations in gene expression45,47. The ratio of YAP1 in the nucleus: YAP1 in the cytoplasm functions as a coarse indicator of overall mechanical sensing, with high nuclear YAP1 observed when cells are cultured on hard substrates46. Nuclear YAP1 is decreased when WT cells are treated with simulated microgravity, supporting the hypothesis that individual cells sense the microgravity-dependent change in their mechanical environment. A similar impact of simulated microgravity on YAP1 shuttling in mesenchymal stem cells has been previously reported, and application of low intensity vibration stimuli could partially rescue this effect55. When we examined ELKIN1-KO cells, the microgravity-induced reduction in the relative levels of nuclear YAP1 was no longer observed, in two different melanoma cell lines. This extraordinary result highlights a new role for ELKIN1 (influencing YAP1 localisation) and reveals that the deletion of ELKIN1 renders cells incapable of responding to simulated microgravity in the same way as WT cells. In PIEZO1-KO melanoma cells, there was similarly high relative levels of YAP1 in the nucleus when cells were treated with simulated microgravity, suggesting that mechanotransduction via ion channels is an important factor in regulating YAP1 localisation when cells experience weightlessness. However, these results are confounded by the fact that, under conditions of 1 g, the deletion of PIEZO1 or the overexpression of ELKIN1 both result in reduced nuclear YAP1, as seen here (Fig. 5) and reported for PIEZO1 deletion elsewhere in other mechanically responsive cells5,56. Previously reported data has also shown that deletion of PIEZO1 from osteoblasts resulted in changes in gene expression patterns when these cells were treated with simulated microgravity23, and that in hindlimb suspension models, reductions in bone mass and perturbations of aortic function are influenced by Piezo1 function23,24,25. These data suggest that MA ion channels are important molecular effectors of cellular adaptations that occur in simulated microgravity and that the loss of these force sensing molecules has a similar impact on YAP1 localisation as stimulating MSCs with low intensity vibrations55.

An important factor that must be considered when investigating force sensing via ion channels is that such molecules are highly context dependent57. The cellular background3 the presence of accessory molecules58,59,60,61,62,63,64,65,66,67 and the mechanical nature of the environment5,68 can all influence the activation and impact of signalling via MA ion channels. As such, ELKIN1 may be regulating cellular adaptations in microgravity due to the change in the mechanical context of the cells when they experience weightlessness. In such a model, ELKIN1 would not be acting as a gravity sensing molecule, per se, but would be mediating these changes due to disruptions in normal function. A second consequence of this context dependency of MA channel activation is that, while data generated from cells cultured on plastic can reveal molecular factors that are involved in mechanical transduction, as shown here, it is also important to combine such studies with an investigation of the impact of microgravity on cells in environments more mimetic of in vivo conditions69,70. We found that simulated microgravity caused a decrease in WT melanoma cell dissociation from organotypic spheroids that mimic a tumour mass. However, the deletion of ELKIN1 reduced the impact of simulated microgravity on cell invasion. These data support a role for ELKIN1 in regulating alterations in cell behaviour that occur in simulated microgravity, in both 2D and 3D microenvironments.

Here we show that the ELKIN1 ion channel regulates cellular responses to microgravity. The deletion of ELKIN1 ablated or delayed simulated-microgravity induced alterations in molecular and cellular properties. These data more broadly support an important, mechanistic, role for mechanically activated ion channels in cellular adaptations in reduced gravity.

Methods

Cell culture

Wild type (WT) and ELKIN1-knockout (ELKIN1-KO) clonal isolates, previously derived from WM266-4 (RRID:CVCL_2765) human melanoma cells7, were used in this study. Two WT clones (WT-3B6 and WT-3E9) and two ELKIN1-KO clones (E1KO-3C6 and E1KO-3D6) were analysed. Cells were further modified to express either mNeonGreen-CAAX or mScarlet-CAAX to fluorescently label the cell membrane. Rescue experiments were performed with the E1KO-3C6 isolate stably transfected with ELKIN1-isoform 1-mGFP7. All WM266-4 derived cells were cultured in complete Minimal Essential Medium Eagle (MEME)(Sigma-Aldrich), containing 10% FBS and 1% Penicillin/Streptomycin. Clonal derivates from A375-MA2 (RRID:CVCL_X495), a second melanoma cell line, were cultured in Dulbecco’s Modified Eagle’s Medium (DMEM), containing 10% FBS and 1% Penicillin/Streptomycin. These lines included WT, ELKIN1-KO, PIEZO1-knockout (PIEZO1-KO) and ELKIN1, PIEZO1-double knockout cells. All cells were cultured at 37 °C, 5% CO2 in a humidified incubator and were regularly tested for Mycoplasma contamination by the Mycoplasma testing facility at UNSW. For simulated microgravity experiments, cells were used between passage 4-20, before discarding. WM266-4 edited cell lines constructed are available on request.

Simulated microgravity: 2-dimensional cell culture

For simulated microgravity experiments on samples cultured on 2D substrates, cells were seeded in duplicate 96-well microplates (Greiner Bio-One) or duplicate 18 well µ-slides (ibidi GmbH) at a concentration of 5 × 103 cells/well for morphological and molecular distribution analysis and 1 × 104 cells/well for cell adherence measurements. In all cases, 2D experiments were performed without coating or modifying the sample wells. Post-seeding, cells were maintained under standard cell culture conditions for 16 h to maximise attachment and spreading. Immediately before placement in the RPM, each well was completely filled with media and the culture plates were then sealed with an air-permeable membrane. Care was taken to exclude bubbles to minimise any potential shear stress from the movement of the simulated microgravity device, wells with evident bubbles were marked and excluded from analysis. Subsequently, one sample was mounted on the RPM (EXPLOR Space Technologies, Sydney, NSW, Australia) at the centre of the inner frame to simulate microgravity (~0.001 g), while eliminating artefacts arising from rotational kinematics. The RPM was located inside a cell culture incubator set for standard cell culture conditions, and a duplicate sample placed in the same incubator, next to the RPM, as a 1 g control (Fig. 1). Simulated microgravity was then applied using standard, validated factory settings within the Explor software for either 4 h or 16 h. Post-application of simulated microgravity, plates were removed from the incubator and cells were immediately fixed using 4% paraformaldehyde (PFA), at room temperature, for 15 min. Data were obtained from at least duplicate wells of each sample, from 3 independent experiments performed on separate days.

Simulated microgravity: 3 dimensional cell culture

For simulated microgravity experiments on cell samples in 3 dimensional (3D) environments, 1 × 103 cells were first seeded into ultra-low attachment plates and left to aggregate and form spheroids over 72 h7, under standard culturing conditions. Compact and reusable platforms, with dimensions matching wells in a 96 well plate, were then created using the curable elastomer polydimethylsiloxane (PDMS). Briefly, the PDMS bulk elastomer and cross-linker solutions were mixed in a ratio of 10:1, degassed and cured for 2 h at 110 °C in a 60 mm petri dish. After polymerisation, PDMS blocks were peeled away from the petri dish and cut into cubes of 2.5 cm in length. A biopsy puncher was used to create 3 wells in the PDMS block (6 mm diameter), which was subsequently bonded to a coverslip (24 × 50 mm), using oxygen plasma treatment. Before use, PDMS platforms were washed with 70% ethanol, rinsed with PBS and treated with ultraviolet illumination for 30 min prior to sample preparation.

To prepare 3D samples, collagen gel mixtures were made from 1.8 mg/mL rat tail Collagen I (#354236, Corning, USA) on ice. A base collagen gel was formed in each well of the PDMS platform by incubating 30 μL of the collagen mixture at 37 °C, 5% CO2 for 6 min. The collagen gel mixture containing the spheroid was then applied to the base gel and underwent gelation at 37 °C, 5% CO2 for 15 min. Cells in collagen gels were cultured under 70 μL of complete media and a gas permeable adhesive film was applied to both exclude air bubbles and avoid leaking during the rotation of the sample mounted in the RPM. As above, in all cases duplicate samples were prepared, with one sample mounted in the RPM (at the centre of the inner frame) and the second placed in the same incubator as a 1 g control. Samples were fixed at times 0, 24 and 48 h treatment, using 4% PFA in PBS, 1 h, room temperature.

Immunofluorescence

Prior to imaging, fixed 2D samples were permeabilised with 0.1% Triton-X 100 in PBS for 5 min. Nuclei were labelled using Hoechst (0.1 µg/ml) and the cell membrane was labelled with wheat germ agglutinin-fluorescein isothiocyanate (WGA-FITC) (1:400; Sigma-Aldrich). For antibody labelling, cells were treated with blocking solution (3% fetal goat serum in PBS) for 1 h at room temperature, before labelling with primary antibody, overnight at 4 °C, diluted in blocking solution. Cells were then washed 3 x with blocking solution and labelled with secondary antibody, diluted 1:1000 in blocking solution, for 1 h at room temperature. Samples were washed 3 x with PBS before imaging. For this study the following antibodies were used: rabbit anti YAP1 antibody (ab205270, Abcam; 1:500 dilution, RRID:AB_2813833), mouse anti-Zyxin antibody (ab58210, Abcam, 1:250 dilution, RRID:AB_946255), rabbit anti-Paxillin antibody (ab32084, Abcam, 1:100 dilution, RRID:AB_779033), goat anti-rabbit-AlexaFluor647 antibody (A21244, Molecular Probes, 1:1000 dilution, RRID:AB_2535812), goat anti-mouse-AlexaFluor488 antibody (ab150113, Abcam, 1:1000 dilution, RRID:AB_2576208), goat anti-rabbit-AlexaFluor488 antibody (ab150077, Abcam, 1:1000 dilution, RRID:AB_2630356). In 2D experiments, actin structures were visualised using Dylight 488 Phalloidin (1:40 dilution, ThermoFisher Scientific). For spheroids and invasive cells embedded in collagen gels, samples were permeabilised in 0.3% Triton X-100, for 1 h and subsequently labelled using Phalloidin-DyLight 594 (1:20 dilution, ThermoFisher Scientific) and Hoechst for 1 h. To assess proliferation of cells within spheroids, spheroid cultures were stained using rabbit anti-Ki67 antibody [SP6] (ab16667, Abcam, 1:250 dilution, RRID:AB_302459),

Imaging and analysis

To quantify the number of adherent cells, cell nuclei labelled with Hoechst were imaged using a 10x/0.3 NA objective, DAPI-U filter and DS-Qi2 CMOS camera, on a Nikon Eclipse Ti2 inverted microscope, using the propriety software, NIS Elements, version 4.6. Cell number was determined from post hoc analysis of the number of nuclei, by creating a binary image using the FIJI distribution of ImageJ (ImageJ, RRID:SCR_003070) and the ‘Analyse Particles’ function was used to automatically determine the number of stained nuclei within the field of view. Data from each independent experiment were normalised against the average cell number for each 1 g control sample. To assess changes in the morphology of cells and nuclei, image stacks were obtained using either Zeiss LSM 880, fitted with a 40x/1.3 NA Water objective or a Zeiss LSM 900 equipped with 40x/1.3 NA oil objective. Samples were illuminated using either 488 or 561 laser, as appropriate, using the Zeiss propriety software, Zen Blue 2.1 (Zeiss 880) or Zen Blue 3.1 (Zeiss 900). All data were subsequently processed using Imaris 9.3.1 software (Bitplane AG, Zurich, Switzerland, RRID:SCR_007370). A cell mask was generated in Imaris, based on the intensity distribution of WGA-FITC labelling and the cell area-to-volume ration was calculated from the surface area and volume parameters automatically determined by Imaris from the cell mask. The cell-aspect ratio was extracted from the Cell Bounding Box Length parameter and calculated as:

Cells were excluded from this analysis if they were multi-nucleated, necrotic, partially out of frame or where the signal was insufficiently strong to generate a coherent mask. Morphological parameters were measured from at least 15 cells for each experimental condition, with data obtained from triplicate samples generated on three separate days.

The size of Paxillin and Zyxin defined focal adhesions (FAs) was determined from images obtained from blinded samples and all analysis was similarly blinded to cell type and treatment. The measure function in FIJI was used to determine the area of each Paxillin-defined FA structure within 10 µm of the periphery of the cell, from an outline of each Paxillin domain, followed by the corresponding Zyxin-defined domain, at the same FA site. The Zyxin: Paxillin area was also calculated for each individual FA. The ratio of nuclear YAP1: perinuclear (cytoplasmic) YAP1 was calculated from blinded images of cells stained with anti-YAP1 antibody by first measuring the average intensity within a region of the nucleus, followed by the average signal intensity of a similarly-sized region of the cell, adjacent the nucleus45.

Labelled spheroids and invasive cells in 3D collagen gels were imaged using a Leica SP8 DLS fitted with a 20x/0.4 NA objective, to collect image stacks encompassing the entire spheroid and surrounding dissociated cells. For spheroids with a broad distribution of dissociated cells, a 10x objective was used to capture the entire sample. Data were analysed using Imaris 9.1.2 software to segment cells by creating masks with a cut-off filter of 200 µm3 to exclude cell debris. Dissociated cells were filtered by centre of image mass versus z depth, where the z value was determined by orientating the 3D image stacks to the plane of view showing the cells on the glass. Any cells attached to the glass under the base collagen gel were excluded from analysis. A spheroid mask corresponding to spheroid size at time = 0 was created and dissociated cells outside this masked area were identified in Imaris. From these data, the number of dissociated cells and their coordinate positions, were exported and analysed. Data were obtained from triplicate experiments conducted on separate days. Supplementary experiments to confirm alterations in invasion were conducted using additional WT and ELKIN1-KO clones. Spheroid samples were exposed to 48 h simulated microgravity (as above) and then fixed and imaged using bright field microscopy (10x/0.3 NA objective, DS-Qi2 CMOS camera, on a Nikon Eclipse Ti2 inverted microscope). The circumference of the invasion front was assayed in FIJI as an indicator of the extent of invasion.

Statistical analyses

All statistical analyses were performed using GraphPad Prism 9 (La Jolla, CA, USA, RRID:SCR_002798). Data sets were analysed to determine if they were normally distributed, using a D’Agostino-Pearson test. Non-normally distributed data were analysed using a Kruskal-Wallis test with Uncorrected Dunn’s test to compare individual groups. Normally distributed data were compared using one way ANOVA with Fisher’s LSD test to compare individual groups. Statistical significance was accepted at the level of p < 0.05. All analyses compared WT controls to WT cells exposed to simulated microgravity and KO controls to KO cells exposed to microgravity, but the two cell types were not compared.

Data availability

The data that support the findings in this study are available on request.

References

Trudel, G., Shahin, N., Ramsay, T., Laneuville, O. & Louati, H. Hemolysis contributes to anemia during long-duration space flight. Nat. Med. 28, 59–62 (2022).

Afshinnekoo, E. et al. Fundamental Biological Features of Spaceflight: Advancing the Field to Enable Deep-Space Exploration. Cell 183, 1162–1184 (2020).

Poole, K. The Diverse Physiological Functions of Mechanically Activated Ion Channels in Mammals. Annu. Rev. Physiol. 84, 307–329 (2022).

Engler, A. J., Sen, S., Sweeney, H. L. & Discher, D. E. Matrix Elasticity Directs Stem Cell Lineage Specification. Cell 126, 677–689 (2006).

Pathak, M. M. et al. Stretch-activated ion channel Piezo1 directs lineage choice in human neural stem cells. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. 111, 16148–16153 (2014).

Holt, J. R. et al. Spatiotemporal dynamics of PIEZO1 localization controls keratinocyte migration during wound healing. eLife 10, e65415 (2021).

Patkunarajah, A. et al. TMEM87a/Elkin1, a component of a novel mechanoelectrical transduction pathway, modulates melanoma adhesion and migration. eLife 9, e53308 (2020).

Kai, F. B., Laklai, H. & Weaver, V. M. Force Matters: Biomechanical Regulation of Cell Invasion and Migration in Disease. Trends Cell Biol. 26, 486–497 (2016).

Broders-Bondon, F., Ho-Bouldoires, T. H. N., Fernandez-Sanchez, M. E. & Farge, E. Mechanotransduction in tumor progression: The dark side of the force. J. Cell Biol. 217, 1571–1587 (2018).

Chin, L. K., Xia, Y., Discher, D. E. & Janmey, P. A. Mechanotransduction in cancer. Curr. Opin. Chem. Eng. 11, 77–84 (2016).

Jahed, Z. & Mofrad, M. R. The nucleus feels the force, LINCed in or not! Curr. Opin. Cell Biol. 58, 114–119 (2019).

Janota, C. S., Calero-Cuenca, F. J. & Gomes, E. R. The role of the cell nucleus in mechanotransduction. Curr. Opin. Cell Biol. 63, 204–211 (2020).

Wang, N., Tytell, J. D. & Ingber, D. E. Mechanotransduction at a distance: Mechanically coupling the extracellular matrix with the nucleus. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 10, 75–82 (2009).

Friedland, J. C., Lee, M. H. & Boettiger, D. Mechanically Activated Integrin Switch Controls α 5 β 1 Function. Science 323, 642–644 (2009).

Hynes, R. O. Integrins: Bidirectional, allosteric signaling machines. Cell 110, 673–687 (2002).

Sun, Z., Guo, S. S. & Fässler, R. Integrin-mediated mechanotransduction. J. Cell Biol. 215, 445–456 (2016).

Bays, J. L., Campbell, H. K., Heidema, C., Sebbagh, M. & Demali, K. A. Linking E-cadherin mechanotransduction to cell metabolism through force-mediated activation of AMPK. Nat. Cell Biol. 19, 724–731 (2017).

Lecuit, T. & Yap, A. S. E-cadherin junctions as active mechanical integrators in tissue dynamics. Nat. Cell Biol. 17, 533–539 (2015).

Goult, B. T., Yan, J. & Schwartz, M. A. Talin as a mechanosensitive signaling hub. J. Cell Biol. 217, 3776–3784 (2018).

Yoshigi, M., Hoffman, L. M., Jensen, C. C., Yost, H. J. & Beckerle, M. C. Mechanical force mobilizes zyxin from focal adhesions to actin filaments and regulates cytoskeletal reinforcement. J. Cell Biol. 171, 209–215 (2005).

Hirata, H., Tatsumi, H. & Sokabe, M. Zyxin emerges as a key player in the mechanotransduction at cell adhesive structures. Communicative Integr. Biol. 1, 192–195 (2008).

Bidone, T. C. et al. Multiscale model of integrin adhesion assembly. PLOS Comput. Biol. 15, e1007077 (2019).

Sun, W. et al. The mechanosensitive Piezo1 channel is required for bone formation. eLife 8, e47454 (2019).

Hu, Y. et al. The Critical Role of The Piezo1/β-catenin/ATF4 Axis on The Stemness of Gli1+ BMSCs During Simulated Microgravity-Induced Bone Loss. Adv. Sci. 10, 2303375 (2023).

Zhang, J. et al. Long-term simulated microgravity fosters carotid aging-like changes via Piezo1. Cardiovasc. Res. 120, 548–559 (2024).

Koaykul, C., Kim, M.-H., Kawahara, Y., Yuge, L. & Kino-oka, M. Alterations in Nuclear Lamina and the Cytoskeleton of Bone Marrow-Derived Human Mesenchymal Stem Cells Cultured Under Simulated Microgravity Conditions. Stem Cells Dev. 28, 1167–1176 (2019).

Vassy, J. et al. The effect of weightlessness on cytoskeleton architecture and proliferation of human breast cancer cell line MCF-7. FASEB J.: Off. Publ. Federation Am. Societies Exp. Biol. 15, 1104–1106 (2001).

Bradbury, P. et al. Modeling the Impact of Microgravity at the Cellular Level: Implications for Human Disease. Front. Cell Developmental Biol. 8, 1–8 (2020).

Buken, C. et al. Morphological and Molecular Changes in Juvenile Normal Human Fibroblasts Exposed to Simulated Microgravity. Sci. Rep. 9, 1–22 (2019).

Kopp, S. et al. Identifications of novel mechanisms in breast cancer cells involving duct-like multicellular spheroid formation after exposure to the Random Positioning Machine. Sci. Rep. 6, 26887 (2016).

Pietsch, J. et al. Spheroid formation of human thyroid cancer cells in an automated culturing system during the Shenzhou-8 Space mission. Biomaterials 34, 7694–7705 (2013).

Zhang, S. et al. The effects of spheroid formation of adipose-derived stem cells in a microgravity bioreactor on stemness properties and therapeutic potential. Biomaterials 41, 15–25 (2015).

Dietz, C., Infanger, M., Romswinkel, A., Strube, F. & Kraus, A. Apoptosis induction and alteration of cell adherence in human lung cancer cells under simulated microgravity. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 20, 3601 (2019).

Po, A. et al. Phenotypic transitions enacted by simulated microgravity do not alter coherence in gene transcription profile. npj Microgravity 5, 27 (2019).

Masiello, M. G. et al. Phenotypic Switch Induced by Simulated Microgravity on MDA-MB-231 Breast Cancer Cells. BioMed. Res. Int. 2014, 1–12 (2014).

Sahana, J. et al. Alterations of Growth and Focal Adhesion Molecules in Human Breast Cancer Cells Exposed to the Random Positioning Machine. Front. Cell Dev. Biol. 9, 672098 (2021).

Tan, X. et al. Simulated microgravity inhibits cell focal adhesions leading to reduced melanoma cell proliferation and metastasis via FAK/RhoA-regulated mTORC1 and AMPK pathways. Sci. Rep. 8, 3769 (2018).

Borst, A. G. & Van Loon, J. J. W. A. Technology and developments for the random positioning machine. Rpm. Microgravity Sci. Technol. 21, 287–292 (2009).

Chakrabarti, S. et al. Touch sensation requires the mechanically gated ion channel ELKIN1. Science 383, 992–998 (2024).

Patkunarajah, A. Mechanoelectrical signalling via ELKIN1 and PIEZO1 in cell lines derived from metastatic melanoma. PhD diss, UNSW Sydney https://doi.org/10.26190/unsworks/24010 (2022).

Kang, H. et al. GolpHCat (TMEM87A), a unique voltage-dependent cation channel in Golgi apparatus, contributes to Golgi-pH maintenance and hippocampus-dependent memory. Nat. Commun. 15, 5830 (2024).

Puech, P. H., Poole, K., Knebel, D. & Muller, D. J. A new technical approach to quantify cell-cell adhesion forces by AFM. Ultramicroscopy 106, 637–644 (2006).

Poole, K. & Müller, D. Flexible, actin-based ridges colocalise with the β1 integrin on the surface of melanoma cells. Br. J. Cancer 92, 1499–1505 (2005).

Xia, S. & Kanchanawong, P. Nanoscale mechanobiology of cell adhesions. Semin. Cell Developmental Biol. 71, 53–67 (2017).

Dupont, S. Role of YAP/TAZ in cell-matrix adhesion-mediated signalling and mechanotransduction. Exp. Cell Res. 343, 42–53 (2016).

Dupont, S. et al. Role of YAP/TAZ in mechanotransduction. Nature 474, 179–184 (2011).

Panciera, T., Azzolin, L., Cordenonsi, M. & Piccolo, S. Mechanobiology of YAP and TAZ in physiology and disease. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 18, 758–770 (2017).

Hung, W. C. et al. Confinement Sensing and Signal Optimization via Piezo1/PKA and Myosin II Pathways. Cell Rep. 15, 1430–1441 (2016).

Balaban, N. Q. et al. Force and focal adhesion assembly: a close relationship studied using elastic micropatterned substrates. Nat. Cell Biol. 3, 466–472 (2001).

Oakes, P. W., Beckham, Y., Stricker, J. & Gardel, M. L. Tension is required but not sufficient for focal adhesion maturation without a stress fiber template. J. Cell Biol. 196, 363–374 (2012).

Stricker, J., Beckham, Y., Davidson, M. W. & Gardel, M. L. Myosin II-Mediated Focal Adhesion Maturation Is Tension Insensitive. PLoS ONE 8, e70652 (2013).

Uemura, A., Nguyen, T. N., Steele, A. N. & Yamada, S. The LIM domain of zyxin is sufficient for force-induced accumulation of zyxin during cell migration. Biophysical J. 101, 1069–1075 (2011).

Sun, X. et al. Mechanosensing through Direct Binding of Tensed F-Actin by LIM Domains. Developmental Cell 55, 468–482.e7 (2020).

Winkelman, J. D., Anderson, C. A., Suarez, C., Kovar, D. R. & Gardel, M. L. Evolutionarily diverse LIM domain-containing proteins bind stressed actin filaments through a conserved mechanism. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 117, 25532–25542 (2020).

Thompson, M., Woods, K., Newberg, J., Oxford, J. T. & Uzer, G. Low-intensity vibration restores nuclear YAP levels and acute YAP nuclear shuttling in mesenchymal stem cells subjected to simulated microgravity. npj Microgravity 6, 35 (2020).

Zhou, T. et al. Piezo1/2 mediate mechanotransduction essential for bone formation through concerted activation of NFAT-YAP1-ß-catenin. eLife 9, 1–38 (2020).

Richardson, J., Kotevski, A. & Poole, K. From stretch to deflection: the importance of context in the activation of mammalian, mechanically activated ion channels. FEBS J. 289, 4447–4469 (2022).

Poole, K. et al. Tuning Piezo ion channels to detect molecular-scale movements relevant for fine touch. Nat. Commun. 5, 3520 (2014).

Qi, Y. et al. Membrane stiffening by STOML3 facilitates mechanosensation in sensory neurons. Nat. Commun. 6, 8512 (2015).

Cox, C. D., Bavi, N. & Martinac, B. Cytoskeleton-Associated Proteins Modulate the Tension Sensitivity of Piezo1. Biophysical J. 114, 111a (2018).

Cordero-Morales, J. F. & Vásquez, V. How lipids contribute to ion channel function, a fat perspective on direct and indirect interactions. Curr. Opin. Struct. Biol. 51, 92–98 (2018).

Wang, J. et al. Tethering Piezo channels to the actin cytoskeleton for mechanogating via the cadherin-β-catenin mechanotransduction complex. Cell Rep. 38, 110342 (2022).

Zhou, Z. et al. MyoD-family inhibitor proteins act as auxiliary subunits of Piezo channels. Science 381, 799–804 (2023).

Zhang, T., Chi, S., Jiang, F., Zhao, Q. & Xiao, B. A protein interaction mechanism for suppressing the mechanosensitive Piezo channels. Nat. Commun. 8, 1797 (2017).

Hu, J., Chiang, L. Y., Koch, M. & Lewin, G. R. Evidence for a protein tether involved in somatic touch. EMBO J. 29, 855–867 (2010).

Chiang, L.-Y. et al. Laminin-332 coordinates mechanotransduction and growth cone bifurcation in sensory neurons. Nat. Neurosci. 14, 993–1000 (2011).

Wetzel, C. et al. Small-molecule inhibition of STOML3 oligomerization reverses pathological mechanical hypersensitivity. Nat. Neurosci. 20, 209–218 (2017).

Bavi, N., Richardson, J., Heu, C., Martinac, B. & Poole, K. PIEZO1-Mediated Currents Are Modulated by Substrate Mechanics. ACS Nano 13, 13545–13559 (2019).

Silvani, G. et al. Testing 3D printed biological platform for advancing simulated microgravity and space mechanobiology research. npj Microgravity 8, 19 (2022).

Silvani, G. et al. A 3D-Bioprinted Vascularized Glioblastoma-on-a-Chip for Studying the Impact of Simulated Microgravity as a Novel Pre-Clinical Approach in Brain Tumor Therapy. Adv. Therapeutics 4, 2100106 (2021).

Acknowledgements

This material is based upon work supported by the Air Force Office of Scientific Research under award number FA2386-21-1-4035 to KP. The imaging aspects of this study were conducted, in part, using instrumentation situated in and maintained by the Katharina Gaus Light Microscopy Facility of the Mark Wainwright Analytical Centre at UNSW. The authors would like to acknowledge the traditional custodians of the land on which this research was conducted, the Bidjigal people of the Eora nation and pay their respects to Elders past, present and emerging.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

D.W. conducted the bulk of the microgravity and imaging studies in 2D, with some imaging conducted by K.P. and L.S. and G.S. conducted the 3D investigations, with assistance from K.P. and L.S. Extensive support for maintaining cell culture was provided by L.S. and J.C. assisted with student supervision, study design and interpretation. J.C. assisted with project supervision. K.P. conceived the project, obtained funding, helped execute some experiments, supervised the project and wrote the manuscript, with input from all authors.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

J.C. is now CEO of Explor, the company that manufacture the RPM used in this study. All other authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Wang, D., Silvani, G., Schroeter, L. et al. The mechanosensitive channel ELKIN1 regulates cellular adaptations to simulated microgravity. npj Microgravity 11, 10 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41526-025-00466-z

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41526-025-00466-z