Abstract

Gravity, a constant in Earth’s environment, constrains not only physical motion but also our estimation of motion trajectories. Early studies show that natural gravitational acceleration facilitates the manual interception of free-falling objects. However, whether implied gravity affects the perception of coherent motion patterns from local motion cues remains poorly understood. Here, we designed a motion coherence threshold task to measure the visual discrimination of coherent global motion with natural (1 g) and reversed (−1 g) gravitational accelerations. Across five experiments, we showed that the perceptual thresholds of motion coherence were significantly lower under the natural gravity than the reversed gravity condition, regardless of variations in stimulus parameters and visual contexts. These convergent results suggest that the human visual system inherently extracts the gravitational acceleration cues conveyed by local motion signals and integrates them into a unified global motion, thereby facilitating the visual perception of complex motion patterns in natural environments.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Gravity is a fundamental physical invariant of the Earth’s environment, which constrains all the moving things on Earth. Beyond this, the status of Earth’s gravity may serve as prior knowledge in the brain to regulate our sensorimotor processing and mental representations of moving objects1,2,3. People are capable of discriminating different gravity conditions implied by visual parabolic motion although the precision is relatively poor4. Meanwhile, they can precisely estimate the time to collision (TTC) of a moving ball and intercept a free-falling ball whose direction of acceleration aligns with that of gravitational acceleration5,6, while their performance will decline if the acceleration cues imply unnatural (e.g., −1 g or 0 g) compared with natural (i.e., 1 g) gravitational accelerations1,7. These effects are very robust in that they can occur either in the real-world environment8,9, in the immersive virtual reality scene10, or with the computer-simulated visual display3. In addition, literature on visual memory reveals that the memorized locations of previously viewed objects are biased toward the direction of gravity11,12,13, although this effect is modulated by the object’s size, mass14, and its contexts15,16,17,18. Together, these results imply that, instead of passively responding to visual motion cues, people actively construct a mental representation of visual objects attracted by gravity to guide their actions and memory.

The existing studies on how gravitational acceleration cues modulate visual motion analysis concentrated on the extrinsic movements of single objects, such as the motion trajectory of a free-falling ball. However, whether gravitational cues influence the ability to perceive intrinsic global motion patterns from local motion cues is still poorly understood. The most relevant evidence is from the visual perception of biological motion. Human observers have a sophisticated ability to detect and discriminate the movements of biological entities, by integrating the local motion of body joints that are constrained by the effect of gravity19,20,21,22,23. Remarkably, if the gravitational cues in biological motion stimuli are perturbed through vertical inversion, observers’ perception will be severely impaired, regardless of whether the global configuration cues are intact or deprived22,23,24,25,26. These findings suggest that the gravity-compatible acceleration cues in local limb motion play a vital role in biological motion perception. However, it’s worth noting that biological motion is influenced by not only gravitational forces but also the force exerted by the organism, and the visual processing of local biological motion cues involves a heritable mechanism specialized for life motion perception27. Therefore, whether gravitational acceleration cues conveyed by local motions also facilitate the perception of non-biological motion patterns remains to be explored.

In the current study, we investigated this issue by employing a coherent motion perception task, a classic test to probe the visual system’s ability to integrate local motion signals into a coherent global percept28,29,30. We measured the proportion of signal dots required for participants to discriminate the direction of coherent motion embedded in random motion noise, that is, the perceptual threshold. The coherent motion signals were either accelerated by natural gravity (1 g) or by reversed gravity (−1 g). If natural gravitational acceleration cues promote coherent motion perception, signal dots moving under the 1 g condition (accelerating when moving downward and decelerating when upward) would lead to a lower perceptual threshold than their counterparts in the −1 g condition.

In Experiment 1, we embedded upward and downward moving signal dots with 1 g and −1 g accelerations in constant-speed noise dots to examine whether implied gravity promotes coherent motion perception (i.e., reduces the coherence threshold for 1 g motion) within a constant-speed environment. In Experiment 2, we measured the motion coherence threshold using noise dots with the same magnitude of acceleration as the signal dots, preventing participants from accomplishing the task solely based on the existence of accelerations in signals. Experiments 3–5 adopted similar designs as Experiment 2 but with variations in stimulus parameters and visual contexts to assess the generalizability of the observed effects. Experiment 3 modified the stimulus-creation method and introduced varied lifetimes to the motion dots. Experiments 4 and 5 utilized visual scenes with an expanded size and higher local motion speed. Additionally, Experiment 5 changed the stimulus display mode to investigate whether the effect of implied gravity could extend to a real-world-like scenario. Specifically, we presented moving dots with accelerations of ±9.81 m/s2 in physical world coordinates on a large projected screen, instead of presenting the stimuli on a computer screen within a virtual context that provides relative size information as in the previous experiments.

Results

Experiment 1: implied gravity aids motion discrimination within constant-speed noise

Experiment 1 examined whether implied gravity promotes coherent motion perception when observers discriminated the moving directions of gravitational motions embedded in constant-speed noise dots (Fig. 1). All data were normally distributed confirmed by the Shapiro–Wilk test (ps > 0.077). A repeated measures ANOVA with gravitational accelerations (1 g/−1 g) and moving directions (upward/downward) as within-subject factors revealed a significant main effect of gravitational acceleration [F(1,23) = 8.525, p = 0.008, ηp2 = 0.270]. Specifically, participants exhibited lower perceptual thresholds of motion coherence in the 1 g condition than in the −1 g condition (Fig. 2A, Table 1). The main effect of moving direction also reached significance [F(1,23) = 18.041, p < 0.001, ηp2 = 0.440], demonstrating the influence of the directional component on coherent motion perception. A marginal significant interaction was observed [F(1,23) = 3.944, p = 0.059, ηp2 = 0.146]. These results provided preliminary evidence that participants exhibited an enhanced capability to perceive coherent global motion when the local motion conforms to the principles of natural gravity.

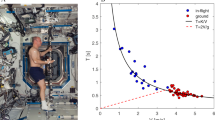

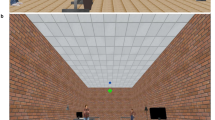

A A schematic illustration of a single trial in Experiments 1, 2, 3, and 4. B Schematics of the motion stimuli and the background. The light dots represent the signal dots moving downward under natural gravity. These dots show an acceleration of 1 g in the virtual scene coordinates with the same initial velocity at the upper side of the square. The hollow dots represent the noise dots, which have the same motion parameters as the signal dots except for moving in random directions. We informed the participants that the perspective drawing presented a long tunnel, and the two figures were 1.8 m in height. C Experimental settings of Experiment 5, in which the participants sat 7 m away from a 1.9-m-height projection screen, and the motion stimuli were projected onto the screen without the perspective drawing background.

A-E Motion coherence thresholds for Experiments 1–5. The bar charts illustrate the mean motion coherence threshold for each condition, with error bars representing the standard errors. Individual participant data for motion coherence thresholds under both 1 g and −1 g conditions, with upward and downward motion directions combined, are plotted as points in the upper panels. Triangles represent the group means. The p-values highlight the main effect of gravitational acceleration. Specific parameter differences for each experiment are labeled on the figure.

Experiment 2: perceiving implied gravity from accelerated noise

In Experiment 1, the noise dots were moving at a uniform speed, leaving the possibility that participants accomplished the task solely by detecting the existence of acceleration. To better assess participants’ ability to perceive coherent motion through local motion, Experiment 2 further examined whether implied gravity promotes coherent motion perception when observers have to discriminate vertical gravitational acceleration from other directions of acceleration. All data were normally distributed confirmed by the Shapiro–Wilk test (ps > 0.233). A repeated measures ANOVA revealed a significant main effect of gravitational acceleration [F(1,23) = 13.572, p = 0.001, ηp2 = 0.371], with the coherence threshold being lower in the 1 g condition than in the −1 g condition (Fig. 2B, Table 1). The main effect of moving direction was significant [F(1,23) = 4.528, p = 0.044, ηp2 = 0.164], while there was no significant interaction [F(1,23) = 0.500, p = 0.487, ηp2 = 0.021]. In line with the first experiment, these results demonstrated enhanced perception of coherent global motion from gravity-compatible local motion cues.

Experiment 3: robust influence of implied gravity under variable stimulus conditions

In Experiment 3, we adopted a similar design to Experiment 2 but randomized the lifetime of the motion dots, testing the influence of implied gravity on coherent motion perception in a highly different stimulus setting. All data were normally distributed confirmed by the Shapiro–Wilk test (ps > 0.077). A repeated measures ANOVA revealed a significant main effect of gravitational acceleration [F(1,24) = 8.373, p = 0.008, ηp2 = 0.259], with the coherence threshold being lower in the 1 g condition than in the −1 g condition (Fig. 2C, Table 1). The main effect of moving direction was not significant [F(1,24) = 1.863, p = 0.185, ηp2 = 0.072], and there was no significant interaction [F(1,24) = 0.455 p = 0.506, ηp2 = 0.019]. In line with Experiment 2, these results demonstrate enhanced perception of coherent global motion from gravity-compatible local motion cues.

Experiment 4: testing implied gravity under varying stimulus parameters

Experiment 4 further assessed the generalizability of the observed effects with varying stimulus parameters. In particular, we utilized expanded visual size (15°-by-15°) and higher average local motion speed (40.7 degrees/s) as compared with those in Experiment 2 (8°-by-8°, 17.7 degrees/s). All data were normally distributed confirmed by the Shapiro–Wilk test (ps > 0.145). A repeated measures ANOVA revealed a significant main effect of gravitational acceleration [F(1,23) = 6.835, p = 0.015, ηp2 = 0.229]. The main effect of moving direction [F(1,23) = 0.707, p = 0.409, ηp2 = 0.030] and the interaction [F(1,23) = 0.200, p = 0.659, ηp2 = 0.009] were not significant (Fig. 2D, Table 1). These results suggested that the effect of implied gravity on coherent motion perception found in Experiments 1–2 could be generalized and observed with varying parameters.

Experiment 5: extending implied gravity effects to a real-world display context

Experiment 5 aimed to investigate whether the influence of implied gravity on coherent motion perception could extend to a real-world-like scenario. To this end, we presented stimuli on a projected screen far away from the observers rather than on a computer screen within a virtual context that provided relative size cues as in the previous experiments (Fig. 1C). Other stimulus parameters matched those in Experiment 4. Participants sat 7 m from a wide screen and viewed the motion stimuli. The acceleration or deceleration of the moving dots was 9.81 m/s2 in physical world coordinates. Under this setting, the perceptual threshold for natural gravitational motion was again lower than that for inversed accelerated motion (Fig. 2E, Table 1). All data were normally distributed confirmed by the Shapiro–Wilk test (ps > 0.070). In line with Experiment 4, a repeated measures ANOVA revealed a significant main effect of gravitational acceleration [F(1,23) = 5.621, p = 0.027, ηp2 = 0.196]. The main effect of moving direction [F(1,23) = 0.229, p = 0.637, ηp2 = 0.010] and its interaction with gravitational accelerations [F(1,23) = 1.278, p = 0.270, ηp2 = 0.053] were not significant.

Comparison of results across experiments

Although the main effect of gravitational acceleration directions was found in all experiments, it is unclear whether this phenomenon is mediated by the properties of the stimulus or the experimental environment. To answer these questions, we conducted a series of cross-experimental comparisons (Table 2).

The only difference between the first two experiments was whether the noise dots contained acceleration or not. To analyze the influence of the acceleration of the noise on the effect of gravity, we conducted a 2 (noise types: constant/accelerated) × 2 (gravitational accelerations: 1 g/−1 g) × 2 (moving directions: upward/downward) mixed ANOVA. Results revealed significant main effects of gravitational accelerations [F(1,46) = 21.831, p < 0.001, ηp2 = 0.322] and moving directions [F(1,46) = 19.614, p < 0.001, ηp2 = 0.299], but no significant main effect of noise types (p = 0.330). The interactions between noise types and gravitational accelerations or motion directions did not reach significance either (ps > 0.100). These results demonstrated that the acceleration of the noise dots did not influence the effect of gravitational acceleration directions.

The key difference between Experiment 2 and Experiment 3 was the introduction of varied dot lifetimes in Experiment 3, which added a dynamic component to the motion stimuli and enhanced uniformity of stimulus distribution across space. To assess the influence of dot lifetime on the effect of gravitational acceleration, we conducted a 2 (dot lifetime: fixed/varied) × 2 (gravitational accelerations: 1 g/−1 g) × 2 (moving directions: upward/downward) mixed ANOVA. Results revealed significant main effects of gravitational accelerations [F(1,47) = 22.176, p < 0.001, ηp2 = 0.321] and moving directions [F(1,47) = 5.204, p = 0.027, ηp2 = 0.100], but no significant main effect of dot lifetime (p = 0.161). The interactions between dot lifetime and gravitational accelerations or motion directions did not reach significance either (ps > 0.177). These results demonstrated that the introduction of limited dot lifetimes did not influence the effect of gravitational acceleration directions.

Experiments 4 and 5 had comparable stimuli, with the only difference lying in the presentation context—Experiment 4 employed computer-simulated scenes in virtual-world coordinates while Experiment 5 used real-size scenes. Given that the presence of visual background significantly affects gravitational motion processing31,32, here we examined the potential influence of contextual environment on the perceptual thresholds of motion coherence by comparing the results from Experiments 4 and 5. A 2 (context: real/virtual) × 2 (gravitational accelerations: 1 g/−1 g) × 2 (moving directions: upward/downward) mixed ANOVA showed only a significant main effect of gravitational accelerations [F(1,46) = 12.016, p < 0.001, ηp2 = 0.207], without evident main effect of contextual environment or interactions between context and other factors (ps > 0.199). These results suggest that the presentation context does not influence the effect of gravity on coherent motion perception.

In addition, to analyze whether low-level visual properties such as stimulus size and average speed influence the results, we compared the results of Experiments 2 (smaller sizes, lower speeds) and 4 (larger sizes, higher speeds). We conducted a 2 (experiments: 2/4) × 2 (gravitational accelerations: 1 g/−1 g) × 2 (moving directions: upward/downward) mixed ANOVA. We found a significant main effect of gravitational accelerations [F(1,46) = 20.046, p < 0.001, ηp2 = 0.304]. Moreover, the main effect of experiments [F(1,46) = 5.282, p = 0.026, ηp2 = 0.103] was significant, with lower thresholds for larger and faster stimuli. The interaction between experiments and moving directions [F(1,46) = 4.966, p = 0.031, ηp2 = 0.097] also reached significance. Simple effect analysis for the interaction showed that moving directions had a significant effect on Experiment 2 (F = 6.13, p = 0.017) but not on Experiment 4 (F = 0.46, p = 0.502). The difference in moving directions was larger for smaller and slower stimuli. The other main effects and interactions did not reach significance (ps > 0.210). These results revealed that the visual angle and average speed of motion stimuli did not influence the effect of gravitational acceleration directions. However, they modulated the effect of moving directions. These results indicate that gravity may be a stable anchor in motion perception, while the effect of moving direction depends on the stimuli.

Discussion

The present research employed a coherent motion perception task to assess whether implied gravity cues influence the visual system’s ability to integrate local motion signals into coherent global motion percepts. In five experiments, we measured the perceptual thresholds for coherent motion under the natural (1 g) and reversed (−1 g) gravitational acceleration conditions. We obtained consistent results that compared with the −1 g motion condition, participants exhibited a lower coherent motion perception threshold in the 1 g condition. These results provide compelling evidence that gravitational acceleration cues conveyed by local motion signals facilitate the visual perception of coherent global motion. They extend the previous findings that gravity cues affected the processing or representation of external motion trajectories of objects5,6,12,13,33,34, shedding new light on how prior knowledge about gravitational acceleration shapes visual motion perception.

Considering that motion estimation is influenced by various factors, such as stimulus properties and visual context, we also examined whether and how these variables modulate the perception of gravitational motion. First, cross-experiment comparisons revealed that the effect of gravity was not modulated by either the distinct motion characteristics of noise dots (Experiments 1 and 2), the introduction of varied dot lifetimes and different stimulus creating methods (Experiments 2 and 3), or the visual angle and average speed of stimuli (Experiments 2 and 4), which underscores the robustness of the effect of implied gravity in motion perception.

Notably, we showed that the gravitational coherent motion thresholds differed between the upward and downward conditions in Experiments 1 and 2, with greater sensitivity for upward motion. Since downward movement is more common in visual contexts (e.g., falling objects), these results may be attributed to increased attention to novel stimuli. However, the influence of motion direction was not evident in Experiments 4 and 5, which differed from Experiments 1 and 2 mainly in low-level stimulus properties (e.g., stimulus size and motion speed), indicating that motion direction may influence coherent motion perceptual threshold only with certain stimulus properties. The limited range of parameters used in the current study has reduced our ability to explain this phenomenon. Adopting continuously varied stimulus parameters in future studies might help better explain the differences regarding the effect of motion direction across experiments. In addition, using psychophysical methods, one recent study has revealed a perceptual bias in which downward-falling objects require greater acceleration to appear at a constant velocity compared to upward-moving objects. However, the study found no difference in sensitivity to acceleration between downward and upward movements35. The distinction between this study and our study lies in specific aspects of stimulus presentation, such as visual context, depth cues, and experimental task design. These differences may impact how acceleration is perceived in upward and downward motion. However, despite these variations, the main effect of gravitational acceleration direction was significant in all the experiments, suggesting that the impact of implied gravity on motion perception occurs regardless of the main effect of motion direction.

Finally, the results of Experiments 4 and 5, which compared the effects of display contexts, showed no significant difference in the perceptual influence of gravitational cues. By using larger stimuli, higher speeds, and a real-size display, these experiments more closely approximate real-world motion scenarios, thereby enhancing the ecological validity of our findings. However, we acknowledge that the current design only partially addresses ecological validity, as it does not fully establish whether our findings generalize to real-world conditions where non-vertical motion would result in bent trajectories. Further research is needed to address this limitation. Together, our results from 5 experiments provide converging evidence that gravity is a stable anchor in coherent motion perception, and its influence can occur consistently across different stimuli and environments.

In addition, our findings suggest intriguing parallels between the influence of gravity on non-biological and biological motion perception. Previous research highlighted that gravitational acceleration cues embedded in local motion are crucial for the perception of biological motion. People could easily distinguish between biological motion on the Earth (1 g) and the simulated biological motion on the Moon (0.16 g; Maffei et al., 2015). Perception of biological motion is strongly impaired when the orientation changes from upright (1 g) to inverted (−1 g), regardless of whether its global configuration is intact or disrupted22,23,24,25,26. Our study extends these findings and suggests that the faciliatory role of gravitational acceleration cues in visual motion perception may be a general phenomenon, not limited to biological motion. At the neural level, previous studies have proposed an internal model hypothesis that highlights the role of the vestibular cortex in visual perception of gravitational motion. This hypothesis suggests that the human vestibular cortex integrates vestibular estimates of gravity and visual inputs to construct the representational visual gravitational information, preparing for further sensory processing, sensorimotor integration, and motor control5,36. The vestibular cortex can be activated by multiple visual gravitational cues, including vertical moving objects5,32, simulated vertical self-motion37, as well as biological motion38. Thus, we speculate that the vestibular cortex may also be involved in our gravitational coherence threshold task. Further studies could investigate the function of the vestibular cortex in integrating coherent motion perception based on the gravitational local motion signals. Besides, building upon the established link between the Earth’s gravity environment and biological motion perception through vestibular gravity computation23, a crucial question emerges: does the gravity environment exert a similar influence on the perception of non-biological motion? This question awaits further exploration.

In conclusion, we measured the visual perceptual threshold of coherent motion under different gravitational conditions. Results show that the human visual system has an advantage in processing local motion signals that imply the effect of natural gravitational force and instantaneously integrating them into a unified global motion percept. This sensitivity to gravitational cues enhances our ability to reliably detect and accurately perceive natural movement patterns in the Earth’s environment.

Methods

Participants

A total of 130 participants (89 females, 23.3 ± 2.8 years old) took part in the study, with 28 in Experiment 1, 25 in Experiment 2, 26 in Experiment 3, 25 in Experiment 4, and 26 in Experiment 5. Nine participants (4, 1, 1, 1, and 2 for Experiments 1, 2, 3, 4, and 5, respectively) were excluded from formal data analysis, leaving a sample size of 24 for Experiments 1,2,4,5 and 25 for Experiment 3. According to a power analysis using G*power39 based on our pilot studies, 24 participants would be sufficient to detect a medium effect size (Cohen’s f2 = 0.25) with a power of 0.80 under the α error probability of 0.05. Data exclusion was implemented based on the following criteria to ensure the accuracy and reliability of the results. First, in at least one condition, the calculated threshold(s) is lower than the minimum fraction (1%) or higher than the maximum fraction (80%) of signal dots that the program can present. Second, the result is not convergent in at least one condition, as the standard error of the last 5 trials exceeds 20%. All participants were right-handed and had normal or corrected-to-normal visions. The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and was approved by the Institutional Review Board of the Institute of Psychology, Chinese Academy of Sciences (approval number: H18029). Informed consent was obtained from all participants.

Apparatus

All experiments were conducted in a dimly lit, sound-proof room. The stimuli were presented using Psychtoolbox40 in MATLAB (MathWorks, Inc.). In Experiments 1, 2, 3, and 4, the participants sat in front of a computer (the viewing distance was 57 cm) with their heads restrained with a chin rest. The computer monitor had a resolution of 1920 by 1080 pixels at a refresh rate of 60 Hz. In Experiment 5, the participants sat 7 m from a 1.9-m-height projection screen. The stimuli were projected onto the surface screen via a liquid crystal projector, with a resolution of 1024 by 768 pixels at a refresh rate of 60 Hz.

Stimuli, design, and procedure

In Experiment 1, the stimuli consisted of 400 moving dots, presented in a square subtended 8°-by-8° visual angle at the screen center. The dots were divided into signal dots, which all moved in the same vertical direction (upward or downward), and noise dots, which moved in random directions except for moving vertically upward and downward (Fig. 1B). The motion of signal dots followed an accelerated or decelerated pattern (randomized across trials) with a constant magnitude of 9.81 m/s² in the simulated virtual scene coordinates. The virtual presentation distance of the stimulus was adjusted to achieve good perceptual clarity and an appropriate level of task difficulty. As a result, the minimum and maximum velocities of the dots were 11.8°/s and 23.6°/s, always appearing at the upper and lower (or lower and upper) edges of the square, with the velocities in-between these area dependent on the height of the stimulus relative to the square. The initial velocity of each signal dot was determined by its initial height. Noise dots moved at a constant speed of 17.7°/s, matching the average speed of the signal dots. All dots were black (RGB = 0, 0, 0), presented on a gray (RGB = 128, 128, 128) background, and had the same size of 0.1° visual angle. The initial distance between every two dots must be greater than 0.3° visual angle, but their distances were not controlled during motion. If a dot crossed the square boundary, it would immediately reappear at the opposite side of the square and continue to move in the original direction. For a signal dot, its velocity would be reset to a value corresponding to that at the edge where it reappeared.

The stimuli were presented on a perspective drawing background on the computer screen (Fig. 1A). The background contained a square at the center, with perspective cues making it appear located deeply inside the computer screen at a long distance from the participants. Two figures were standing on both sides of the square, providing a reference for estimating the actual size of other stimuli on the screen.

Experiment 1 consisted of four conditions based on the movement of signal dots: 2 gravitational acceleration directions (1 g/−1 g) × 2 moving directions (upward/downward). Among them, the accelerated downward and decelerated upward motions conformed to the law of natural gravitational motion (1 g condition), while the accelerated upward motion and decelerated downward motion were reversed to the natural gravitational motion (−1 g condition). Each condition had 40 trials, leading to a total of 160 randomly mixed trials.

At the beginning of the experiment, we asked the participants to imagine they were sitting at one end of a tunnel, with the square located at the opposite end of the tunnel far away from them. They were informed that the height of the tunnel was 3 m, and the height of the two figures near the tunnel was 1.8 m. This information helped participants perceive the stimuli as moving with gravitational acceleration presented at a distance.

Each trial started with a fixation cross presented at the center of the screen for 500 ms, followed by the moving dots display for 1000 ms, and a blank interval for 100 ms. After that, a “?” was presented, and participants were asked to judge whether the direction of the coherent motion was upward or downward by pressing the corresponding keys. The instruction given to participants was: “Please judge the overall direction of the moving dots. While you may observe some dots moving in various directions, focus on determining whether the general movement is upward or downward”. No feedback was provided.

We measured the coherent motion perception threshold for each participant under each condition independently via the QUEST method41, implemented via the Quest toolbox in Psychtoolbox with an algorithm recommended by King-Smith et al.42. The QUEST method is a Bayesian adaptive psychometric procedure, which could be implemented through the following steps. First, the initial coherence level was set to 80% in the first trial of each condition. Then, the coherence level was adjusted for each trial based on the distribution of thresholds computed by the QUEST procedure according to the participants’ responses. The minimum and maximum percentages of signal dots were limited between 1% and 80%. A final perceptual threshold was estimated for each condition at 75% accuracy after 40 trials.

In Experiment 2, we adjusted the motion of the noise dots to match the acceleration or deceleration characteristics of the signal dots. Specifically, the noise dots accelerated or decelerated along their respective random directions with the same magnitude of acceleration or deceleration as the signal dots. Thus, in each trial, both the noise and signal dots followed uniformly accelerated (or decelerated) linear motion, with the only difference lying in their moving directions. For noise dots under accelerating conditions, the speed of each dot when it appeared at the edge of the stimulus area was 11.8°/s, and its speed when it disappeared at the edge ranged between 23.6 and 33.4°/s. Under decelerating conditions, the speed of each noise dot when it appeared at the edge of the stimulus area was 23.6°/s, and its speed when it disappeared at the edge ranged between 8.3 and 11.8°/s. The other aspects remained the same as in Experiment 1.

In Experiment 3, the design and setup were similar to those of Experiment 2, with the primary difference being the introduction of varied dot lifetimes, which enhanced the uniformity of stimulus density across space. Specifically, each dot was assigned a lifetime (\(t)\) randomly sampled within the range of (0,0.75] seconds. The dot velocity ranged approximately between 8°/s (\({v}_{\min }\)) and 27.6°/s (\({v}_{\max }\)). The initial velocity (\({v}_{{init}})\) of a dot depends on the assigned lifetime. Under accelerating conditions, this relationship is given by Eq. (1) and under decelerating conditions, the initial velocity is determined by Eq. (2):

The dots accelerated or decelerated from their initial velocity over their lifetime. Whenever a dot crossed the square boundary, it reappeared at the opposite edge immediately, maintaining its current velocity and direction (and continuing its acceleration or deceleration) until reaching its lifetime. Once a dot’s lifetime expired, it vanished and reappeared at a new random location with a newly assigned initial velocity according to Eq. (1) or Eq. (2).

Experiments 4 & 5 aimed to verify whether the effect of implied gravity could be generalized to different stimulus parameters and display modes. To facilitate comparisons across experiments, we first altered the stimulus parameters (size and speed) in Experiment 4, and building on this, further changed the presentation mode in Experiment 5. Consequently, the stimulus parameters in Experiments 4 and 5 remained consistent.

In Experiment 4, the stimuli consisted of 900 moving dots, presented in a square subtended 15°-by-15° visual angle at the screen center. The corresponding virtual tunnel was 2 m high, and the simulated distance was ~7 m from the participants. Under accelerating conditions, the speed of each dot when it appeared at the edge of the stimulus area was 27.1°/s, and its speed when it disappeared at the edge ranged between 54.2 and 76.6°/s. Under decelerating conditions, the speed of each dot when it appeared at the edge of the stimulus area was 54.2°/s, and its speed when it disappeared at the edge ranged between 19.2 and 27.1°/s. The initial velocity of each signal dot was determined by its initial position. The other aspects remained the same as in Experiment 2.

Experiment 5 was identical to Experiment 4 except that a real-size scene was presented on a 1.9-m-height screen 7 meters away from the participants (Fig. 1C). The perspective drawing background was not employed in Experiment 5.

Data availability

All data generated in the current study are made available at https://doi.org/10.57760/sciencedb.psych.00244.

References

Delle Monache, S. et al. Watching the effects of gravity. Vestibular cortex and the neural representation of “visual” gravity. Front. Integr. Neurosci. 15, 793634 (2021).

Jörges, B. & López-Moliner, J. Gravity as a strong prior: implications for perception and action. Front. Hum. Neurosci. 11, 203 (2017).

Zago, M., McIntyre, J., Senot, P. & Lacquaniti, F. Internal models and prediction of visual gravitational motion. Vis. Res. 48, 1532–1538 (2008).

Jörges, B., Hagenfeld, L. & López-Moliner, J. The use of visual cues in gravity judgements on parabolic motion. Vis. Res. 149, 47–58 (2018).

Indovina, I. et al. Representation of visual gravitational motion in the human vestibular cortex. Science 308, 416–419 (2005).

Zago, M. & Lacquaniti, F. Visual perception and interception of falling objects: a review of evidence for an internal model of gravity. J. Neural Eng. 2, S198–S208 (2005).

Balestrucci, P., Maffei, V., Lacquaniti, F. & Moscatelli, A. The effects of visual parabolic motion on the subjective vertical and on interception. Neuroscience 453, 124–137 (2021).

La Scaleia, B., Lacquaniti, F. & Zago, M. Neural extrapolation of motion for a ball rolling down an inclined plane. PLoS ONE 9, e99837 (2014).

La Scaleia, B., Zago, M. & Lacquaniti, F. Hand interception of occluded motion in humans: a test of model-based vs. on-line control. J. Neurophysiol. 114, 1577–1592 (2015).

Russo, M. et al. Intercepting virtual balls approaching under different gravity conditions: evidence for spatial prediction. J. Neurophysiol. 118, 2421–2434 (2017).

De Sá Teixeira, N. A., Kerzel, D., Hecht, H. & Lacquaniti, F. A novel dissociation between representational momentum and representational gravity through response modality. Psychol. Res. 83, 1223–1236 (2019).

Hubbard, T. L. Cognitive representation of linear motion: possible direction and gravity effects in judged displacement. Mem. Cognit.18, 299–309 (1990).

Hubbard, T. L. Representational gravity: empirical findings and theoretical implications. Psychon. Bull. Rev. 27, 36–55 (2020).

Hubbard, T. L. & Ruppel, S. E. Spatial memory averaging, the landmark attraction effect, and representational gravity. Psychol. Res. 64, 41–55 (2000).

Hubbard, T. L. Cognitive representation of motion: evidence for friction and gravity analogues. J. Exp. Psychol. Learn. Mem. Cogn. 21, 241–254 (1995).

Hubbard, T. L. Some effects of representational friction, target size, and memory averaging on memory for vertically moving targets. Can. J. Exp. Psychol. 52, 44–49 (1998).

Masuda, T., Kimura, A., Dan, I. & Wada, Y. Effects of environmental context on temporal perception bias in apparent motion. Vis. Res 51, 1728–1740 (2011).

Vinson, D. W., Abney, D. H., Dale, R. & Matlock, T. High-level context effects on spatial displacement: the effects of body orientation and language on memory. Front. Psychol. 5, https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2014.00637 (2014).

Blake, R. & Shiffrar, M. Perception of human motion. Annu. Rev. Psychol. 58, 47–73 (2007).

Johansson, G. Visual perception of biological motion and a model for its analysis. Percept. Psychophys. 14, 201–211 (1973).

Neri, P., Morrone, M. C. & Burr, D. C. Seeing biological motion. Nature 395, 894–896 (1998).

Troje, N. F. & Westhoff, C. The inversion effect in biological motion perception: evidence for a “life detector”? Curr. Biol. 16, 821–824 (2006).

Wang, Y. et al. Modulation of biological motion perception in humans by gravity. Nat. Commun. 13, 2765 (2022).

Chang, D. H. F., Ban, H., Ikegaya, Y., Fujita, I. & Troje, N. F. Cortical and subcortical responses to biological motion. NeuroImage 174, 87–96 (2018).

Chang, D. H. F. & Troje, N. F. Acceleration carries the local inversion effect in biological motion perception. J. Vis. 9, 19–19 (2009).

Wang, L., Yang, X., Shi, J. & Jiang, Y. The feet have it: local biological motion cues trigger reflexive attentional orienting in the brain. NeuroImage 84, 217–224 (2014).

Wang, Y. et al. Heritable aspects of biological motion perception and its covariation with autistic traits. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 115, 1937–1942 (2018).

Braddick, O. Visual perception: seeing motion signals in noise. Curr. Biol. 5, 7–9 (1995).

Britten, K., Shadlen, M., Newsome, W. & Movshon, J. The analysis of visual motion: a comparison of neuronal and psychophysical performance. J. Neurosci. 12, 4745–4765 (1992).

Van der Hallen, R., Manning, C., Evers, K. & Wagemans, J. Global motion perception in autism spectrum disorder: a meta-analysis. J. Autism Dev. Disord. 49, 4901–4918 (2019).

Cheron, G. et al. Gravity influences top-down signals in visual processing. PLoS ONE 9, e82371 (2014).

Miller, W. L. et al. Vestibular nuclei and cerebellum put visual gravitational motion in context. J. Neurophysiol. 99, 1969–1982 (2008).

De Sá Teixeira, N. A. et al. Vestibular stimulation interferes with the dynamics of an internal representation of gravity. Q. J. Exp. Psychol. 70, 2290–2305 (2017).

Lacquaniti, F. et al. Visual gravitational motion and the vestibular system in humans. Front. Integr. Neurosci. 7, https://doi.org/10.3389/fnint.2013.00101 (2013).

Phan, M. H., Jörges, B., Harris, L. R. & Kingdom, F. A. A. A visual bias for falling objects. Perception 53, 197–207 (2024).

Merfeld, D. M., Zupan, L. & Peterka, R. J. Humans use internal models to estimate gravity and linear acceleration. Nature 398, 615–618 (1999).

Indovina, I. et al. Simulated self-motion in a visual gravity field: sensitivity to vertical and horizontal heading in the human brain. NeuroImage 71, 114–124 (2013).

Maffei, V. et al. Visual gravity cues in the interpretation of biological movements: neural correlates in humans. NeuroImage 104, 221–230 (2015).

Faul, F., Erdfelder, E., Buchner, A. & Lang, A.-G. Statistical power analyses using G*Power 3.1: tests for correlation and regression analyses. Behav. Res. Methods 41, 1149–1160 (2009).

Brainard, D. H. The psychophysics toolbox. Spat. Vis. 10, 433–436 (1997).

Watson, A. B. & Pelli, D. G. Quest: a Bayesian adaptive psychometric method. Percept. Psychophys. 33, 113–120 (1983).

King-Smith, P. E., Grigsby, S. S., Vingrys, A. J., Benes, S. C. & Supowit, A. Efficient and unbiased modifications of the QUEST threshold method: theory, simulations, experimental evaluation and practical implementation. Vis. Res. 34, 885–912 (1994).

Acknowledgements

This research was supported by grants from the Space Medical Experiment Project of CMSP (HYZHXMR01002), the Ministry of Science and Technology of China (2021ZD0203800, 2021ZD0204200), the National Natural Science Foundation of China (32171059, 32430043), the Interdisciplinary Innovation Team (JCTD-2021-06), the Youth Innovation Promotion Association of the Chinese Academy of Sciences, and the Fundamental Research Funds for the Central Universities.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Y.W. conceptualized the study. X.L. and Y.W. designed the experiments. X.L., B.S., S.Z.(Shaoshuai Zhang), S.Z.(Shujia Zhang), and M.H. conducted data collection and analysis. X.L., B.S., and S.Z.(Shaoshuai Zhang) wrote the original draft and X.L. prepared the figures. Y.W. and Y.J. provided critical revisions. All authors reviewed and approved the final version of the manuscript for submission.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Lu, X., Song, B., Zhang, S. et al. Implied gravity promotes coherent motion perception. npj Microgravity 11, 36 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41526-025-00498-5

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41526-025-00498-5