Abstract

Long-duration spaceflight affects otolith-mediated ocular counter-roll (OCR) and brain function, but the relationship between these changes is unclear. This study examines whether OCR changes correlate with functional connectivity (FC) changes in the vestibular network in the same cosmonauts after a long-duration (6-month) spaceflight mission. Using a human vestibular atlas, we found that changes in FC between the right operculum (OP2_PIVC) and inferior parietal lobule (IPL, area PGp and PGa) were positively correlated with OCR changes. First-time flyers showed a greater decrease in OCR, linked to more significant FC reductions. Irrespective of the OCR, increased FC was observed postflight between the left visual cingulate cortex (CSv) and the anterior cingulate cortex (ACC, area 33), superior parietal lobule (SPL, area 5C), and thalamus (pulvinar), and between the right OP2_PIVC and SPL (area 5Ci). Secondly, decreased FC was observed between the left OP2_PIVC and the IPL (PGp) and SPL (area 7A). Additionally, increased FC postflight was observed between the left lateral sensorimotor area (LSM) and IPL (area PGp), and between the right lateral visual area (LVA) and cerebellum (Crus 1, Lobule VI). These findings suggest sensory reweighting and sensory system reorganization after long-duration spaceflight.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Humans heavily depend on the vestibular organs in the inner ear to detect gravity, head movements, and relay information to the brain, ensuring proper upright posture, stable gaze, and spatial orientation1. These organs consist of the semicircular canals (SCCs), which respond to angular accelerations, and the otolith organs, which signal head translations and the gravitational force vector. Thus, the otolith organs, i.e., the utricle and saccule, act as primary graviceptors. In the free-fall induced state of microgravity on the International Space Station (ISS), where the Earth’s sensed gravitational forces are reduced to 0.000001 G2, the otoliths only detect head translations generated by self-motion. This leads to a deconditioning of the otoliths, characterized by a reduced gain in otolith-mediated reflexes3. In response to this deconditioning in microgravity, neuro-vestibular adaptation is activated, enabling the astronaut to adjust to the altered environment and recalibrate their sensorimotor functions4. Upon return to Earth, the adapted neuro-vestibular system poses challenges at the level of posture, navigation, gaze stabilization, and balance5, requiring a time window of days to weeks to readapt to Earth’s gravity3.

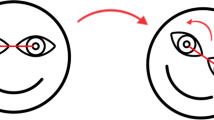

The ocular counter-roll (OCR), an essential otolith-mediated reflex, serves as a crucial measure in studying neuro-vestibular adaptation during spaceflight, isolating the effects of otolith adaptations5,6,7,8,9,10. The OCR is generated when the head is laterally tilted, or during artificial circumstances, such as during centrifugation11,12,13. Following off-axis centrifugation postflight, our team observed a similar transient reduction in OCR, returning to baseline levels 8–12 days after return (R + 8/12) in a cohort of 44 cosmonaut measurements14. Notably, our findings suggest that first-time flyers experience a more pronounced impact of otolith deconditioning, resulting in a more significant reduction in OCR upon returning to Earth compared to frequent flyers (Fig. 1). We hypothesized that experienced flyers show higher OCR values early postflight, compared to first-time flyers, possibly due to central adaptation from prior space missions. This hypothesis stems from the observation that past spaceflight experience influences sensorimotor adaptations to spaceflight15.

a The effect of spaceflight on the otolith-mediated reflex, the ocular counter-roll (OCR). The overall average of the OCR measurements showed a decreased OCR early postflight (R + 1/3, 1–3 days after return) after a 6-month space mission. In addition, the evolution of the OCR across the first 2 weeks postflight is illustrated, showing a return to baseline levels (BDC) 8–12 days after their return (R + 8/12). b The difference between 1st-, 2nd-, 3rd-, 4th-, and 5th-time flyers regarding the effect of long-duration spaceflight on the otolith-mediated OCR. All flyers (first-time to frequent flyers) show a clear decrease in early postflight (R + 1/3). However, the more the cosmonauts have flown, the less the OCR gain decreases postflight. For more details, please review Schoenmaekers et al.14.

The central vestibular system, characterized by bilateral organization, provides functional advantages such as precise differentiation of head motion, compensation for unilateral failures, and adjustment for vestibular imbalances16,17. Its structure involves ascending and descending pathways with crossings in the brainstem and cortex16,17. In a study by zu Eulenburg and colleagues, ten vestibular regions in the cortex were identified using galvanic vestibular stimulation (GVS) during functional magnetic resonance imaging (fMRI). The response patterns observed in this GVS protocol suggest that the core cortical vestibular network in humans likely includes the parietal operculum (OP2), medial superior temporal area (MST), frontal portion of the parietal lobe (parabolic flight (PF), area 7), and visual cingulate sulcus (CSv), also known as the vestibular cingulate area (VC)18. The vestibular system undergoes altered signaling in microgravity, leading to unexpected sensory feedback from head movements3,14,19,20. As a result, the central nervous system adapts to facilitate proper orientation and resolve sensory conflicts21,22. Postflight, astronauts experience declines in vestibular function, such as reduced OCR and heightened sensitivity of utricular afferents to translational accelerations3,14,19,20.

The sensorimotor system includes all the sensory, motor, and central processing components that manage reflex control at the brainstem and cerebellum, voluntary movement regulation in the cortical and subcortical areas, and more complex cognitive functions1,16,23. Spaceflight significantly affects the brain’s sensorimotor regions, which are responsible for coordinating movement and processing sensory information24. In microgravity, the usual sensory cues that help maintain balance and body position on Earth are disrupted or absent, leading astronauts to experience difficulties with coordination, balance, and fine motor skills. Regions that are generally involved in the sensorimotor system are the primary somatosensory cortex, the primary motor cortex, the cerebellum, the lateral and superior sensorimotor cortex, and the visual cortex25.

Neuroimaging techniques have been employed to investigate the impact of microgravity on the central vestibular system in both spaceflight conditions, specifically after 6-month space missions, and its analogs on Earth, including head-down bed rest (HDBR) and PF. The first study on altered brain functional connectivity (FC) following spaceflight using fMRI was conducted by our group on a single Russian cosmonaut26. A decreased connectivity within the right insula was discovered, a region involved in vestibular processing and cognitive control, as well as altered connectivity between the motor cortex and the cerebellum. Two previous studies performed by our team showed functional brain changes in cosmonauts during simulated walking, induced by applying foot pressure, including altered connectivity in multisensory regions related to coordination and proprioception, and lasting connectivity decreases in the posterior cingulate cortex and thalamus, and increases in the right angular gyrus (AG) based on resting-state fMRI27. The bilateral insular cortex showed reduced connectivity, which normalized 8 months after returning to Earth28. In a previous study performed by Hupfeld and colleagues, fMRI was also used to investigate changes in brain activity from pre- to postflight4. Widespread reductions in somatosensory and visual cortical deactivation were revealed postflight, supporting sensory compensation and vestibular reweighting. Furthermore, correlations were observed between pre- to postflight changes in brain activity and eyes closed standing balance. Greater reductions in visual cortical deactivation in response to vestibular stimulation were associated with less postflight balance decline4. Interestingly, the observed brain changes returned to baseline values within 3 months postflight.

Spaceflight analogs, such as HDBR and PF, have proven to be valuable tools for investigating brain changes induced by spaceflight. A study performed by Zhou and colleagues showed that after 45-day HDBR, a functional network centered in the anterior insula (aINS) and midcingulate cortex was affected by simulated microgravity, regions involved in supporting subjective feeling states, and cognitive control and decision making29. A study performed by our group revealed lower overall FC in the right temporo-parietal junction, a region involved in multisensory integration and spatial tasks, after a PF30. Collectively, these previous studies suggest that sensory reweighting and adaptive vestibular cortical neuroplasticity occur in response to altered gravity and spaceflight, providing insights into how the brain compensates for and adapts to vestibular functional disruption.

While both OCR and neuroimaging techniques have been used to investigate the effects of microgravity on the vestibular organs and central vestibular system, the relationship between these two domains remains unknown. Neuroimaging findings alone are challenging to interpret without complementary functional data, and a deeper understanding of how changes in OCR affect downstream central vestibular systems would be valuable. This study seeks to address this gap by investigating whether shifts in OCR before and after spaceflight correlate with FC alterations in specific vestibular cortical regions18. Our hypothesis is that peripheral vestibular alterations, as reflected by OCR changes, have downstream sensory consequences that influence cortical connectivity of central vestibular regions. We propose that shifts in OCR before and after spaceflight will correlate with FC alterations in specific vestibular cortical regions, as changes in peripheral vestibular function can have a ripple effect on the central nervous system. Additionally, the study explores potential brain reweighting mechanisms by examining FC changes in vestibular and sensorimotor areas, comparing pre- and postflight data. Gaining insight into these dynamics could be critical for managing vestibular adaptation, an area of particular importance for future missions to the Moon and other space exploration endeavors.

Results

Analysis I. Prolonged exposure to microgravity alters the vestibular cortical network

The FC analysis employed a seed-based connectivity (SBC) approach. The seed regions were chosen from a vestibular atlas18. We primarily investigated pre- to postflight connectivity differences, considering an uncorrected voxel-level threshold p < 0.001 and a false discovery rate (FDR)-corrected cluster-level threshold of p < 0.05. A significant increase in FC was found between the seed region left CSv and the anterior cingulate cortex (ACC, area 33) (p(FDR) = 0.001), the left superior parietal lobule (SPL, area 5Ci) (p(FDR) = 0.034), and the thalamus (geniculate nuclei, pulvinar) (p(FDR) = 0.034) (Fig. 2a). Secondly, a significant decrease in FC was found between the seed region left OP2_PIVC and the left inferior parietal lobule (IPL, area PGp) (p(FDR) = 0.006) and right SPL (area 7A) (p(FDR) = 0.035) (Fig. 2b). Lastly, a significant increase in FC was found between the seed region right OP2_PIVC and the right SPL (area 5Ci) (p(FDR) = 0.011) (Fig. 2c). The other vestibular seed regions used, including the right CSv, left PFcm_VPS, right PFcm_VPS, nodulus, and uvula, did not show any changes in FC postflight.

a A significant increase in FC postflight was observed between the left cingulate sulcus visual (CSv) and the anterior division of the cingulate gyrus, the left postcentral gyrus, and the thalamus. b A significant decrease in FC postflight was observed between the left OP2 (OP2_PIVC) and the left angular gyrus and right superior parietal lobule (SPL). c A significant increase in FC postflight was observed between the right OP2 (OP2_PIVC) and the right SPL. Results are mapped on a brain template and scaled by t value. The T(13) values indicate the T-statistic with 13 degrees of freedom. Graphs illustrate the effect sizes at pre- and postflight. The effect sizes are expressed as standardized measures (e.g., Cohen’s d), which help indicate how meaningful the results are beyond just being statistically significant.

Anatomical labels were defined using the Juelich Brain Atlas (Version 3.1). The three vestibular seed regions that showed to have altered FC are shown in Fig. 3.

We also found a significant decrease in FC when comparing the first to second MRI scan for the controls between the seed region left OP2 (OP2_PIVC) and the left IPL (area PGp) (p(FDR) = 0.001) (Fig. 4). The other vestibular seed regions used, including the left CSv, right CSv, right OP2_PIVC, left PFcm_VPS, right PFcm_VPS, nodulus, and uvula, did not show any changes in FC at the second MRI. Specifications of significant clusters can be found in Table 1.

A significant increase in FC at the second MRI measurement was observed between the left OP2 (OP2_PIVC) and the left angular gyrus. Results are mapped on a brain template and scaled by t value. The T(18) values indicate the T-statistic with 18 degrees of freedom. Graphs illustrate the effect sizes at the first and second MRI acquisition. The effect sizes are expressed as standardized measures (e.g., Cohen’s d), which help indicate how meaningful the results are beyond just being statistically significant.

Flight-induced alterations in OCR are correlated with vestibulo-cortical FC changes

We next used the same SBC approach and vestibular atlas to investigate correlations between pre- to postflight differences in FC and OCR, considering an uncorrected voxel-level threshold of p < 0.001, and an FDR-corrected cluster-level threshold of p < 0.05. A significant positive correlation was found between the pre- to postflight change in OCR and the change in FC between the vestibular seed region right OP2_PIVC and both the right IPL (area PGp) (p(FDR) = 0.021) and the left IPL (area PGa) (p(FDR) = 0.038) (Fig. 5). The other vestibular seed regions used, including the right CSv, left CSv, left OP2_PIVC, left PFcm_VPS, right PFcm_VPS, nodulus, and uvula, did not show significant correlations between the pre- to postflight change in OCR and FC. As shown in Fig. 5, cosmonauts who experienced the greatest decrease in OCR postflight also exhibited decreased FC.

We found a positive and significant correlation between the pre- to postflight change in OCR and the change in FC between the right OP2 (OP2_PIVC) and a the right angular gyrus, and b left angular gyrus. Results are mapped on a brain template and scaled by t value. The T(12) values indicate the T-statistic with 12 degrees of freedom. Scatter plots on the left side illustrate the correlation between the ∆OCR and ∆Connectivity, indicating that a greater decrease in FC postflight is associated with a greater decrease in OCR. Negative ∆Connectivity indicates an increase in FC postflight, while positive values indicate a decrease in FC postflight.

Specifications of significant clusters can be found in Table 1.

Analysis II. The brain reweights sensory inputs when vestibular inputs are reduced

As a secondary analysis, the focus shifted to the sensorimotor regions from the Harvard-Oxford atlas as seed regions, to investigate the FC difference from pre- to postflight (voxel-level threshold: p < 0.001, uncorrected; cluster-level threshold: p < 0.05, FDR-corrected). An increased FC postflight was found between the left lateral sensorimotor area (LSM) and the left IPL (area PGp) (p(FDR) = 0.010), as well as between the right lateral visual area (LVA) and three clusters located in the cerebellum (left Crus 1, p(FDR) = 0.033; right lobule VI, p(FDR) = 0.033; right Crus 1, p(FDR) = 0.036) (Fig. 6). The other sensorimotor seed regions used, including the right LSM, SSM, medial visual area (MVA), occipital visual area (OVA), and left LVA, did not show any changes in FC postflight.

An increased postflight FC was observed between a the left lateral sensorimotor cortex (LSM) and the left angular gyrus, and between b the right lateral visual cortex (LVA) and three clusters located in the cerebellum. Results are mapped on a brain template and scaled by t value. The T(13) values indicate the T-statistic with 13 degrees of freedom. Graphs on the right side illustrate the increase in effect size postflight. The effect sizes are expressed as standardized measures (e.g., Cohen’s d), which help indicate how meaningful the results are beyond just being statistically significant.

Specifications of significant clusters can be found in Table 1. The two sensorimotor seed regions that showed to have altered FC are shown in Fig. 7.

Discussion

In this study, the primary objective was to examine whether changes in the OCR from pre- to postflight correlate with FC changes observed in the same cosmonauts. Using regions of interest (ROIs) from a vestibular cortical atlas31, we found significant correlations between OCR changes and FC changes between the right OP2 and both left and right AG (right IPL area PGp and left IPL area Pga). As a secondary objective, the effects of spaceflight on FC of the vestibular cortical atlas were investigated. We found FC changes in the vestibular cortical regions CSv, left OP2, and right OP2 after spaceflight compared to before. Lastly, we aimed to study whether sensorimotor and visual areas exhibited altered FC after spaceflight and found significant changes in the left LSM and left LVA. These findings collectively suggest that brain cortical regions exhibit adaptive responses to the spaceflight environment. In particular, the changes seen in vestibular, visual, and sensorimotor regions align with sensory reweighting mechanisms, which prioritize visual and somatosensory information when vestibular input is reduced or altered in microgravity. This adaptive mechanism likely helps astronauts cope with microgravity by altering the way sensory input is integrated, eventually to avoid disorientation and to allow for proper sensorimotor functions.

Our main finding is that changes in OCR correlate with changes in FC between the right OP2 and left and right AG. The OCR is a direct measure of otolith function, which is compromised in microgravity due to a missing gravitational reference. In previous studies, we showed that the ocular tilt degree is decreased 3 days after long-duration spaceflight and normalizes 9 days after long-duration spaceflight with respect to preflight measurements3,14. Moreover, this postflight decrease is significantly more pronounced in first-time flyers compared to frequent flyers14. These findings suggest that microgravity enables central mechanisms to modulate the OCR reflex, with prior spaceflight experience being a significantly contributable factor. Our correlation analysis reveals that the first-time flyers show the strongest decrease in FC between right OP2 and AG and the strongest decrease in OCR. On the contrary, cosmonauts with prior spaceflight experience exhibit less decrease or even an increase in FC, and less OCR decrease. While the central vestibular mechanisms that are responsible for OCR modulation likely involve brainstem and cerebellar nuclei32, the correlations with cortical FC changes might point to secondary effects of compromised vestibular function after spaceflight. Specifically, the FC between right OP2 and the AG might contribute to sensory reweighting and the vestibular system’s input in multisensory integration. From another viewpoint, it can be hypothesized that OP2-AG connectivity is significantly decreased early postflight, followed by a normalization process during the upcoming days that varies depending on the normalization rate of otolith function. This would then result in first-time flyers, who show the strongest decrease of OCR postflight, still exhibiting FC decreases between OP2 and AG 9 days after spaceflight, while frequent flyers do not. The involvement of the right OP2 is worth emphasizing, as it is considered one of the main vestibular cortical hubs and is considered to be the human homolog of the parieto-insular vestibular cortex (PIVC) of Macaques33. While the AG is not specifically included in the vestibular cortical atlas, several studies involving gravitational level changes report changes in the AG. The connectivity of the right AG with the rest of the brain was found to be reduced after gravitational transitions induced by PF30 and was found to be increased after long-duration spaceflight28. The connectivity between right and left AG is also increased in fighter pilots, who frequently experience gravitational level changes, compared to matched controls34. The AG is largely a higher-order cognitive region, serving various functions based on integrated sensory information, including visuospatial attention35, sense of agency36, body-space representation37, and action-outcome monitoring38. Generally, the AG has a proposed function as matching bottom-up information (sensory input) with top-down information (context, internal models) (for review, see ref. 39), which is therefore likely impacted by the sensory conflicts generated by gravitational level changes and altered vestibular signaling. While more details on connectivity between OP2 and AG in regular Earth-based circumstances are lacking, our findings support a connection between peripheral and cortical vestibular changes.

Next, we investigated which vestibular cortical regions show FC changes after spaceflight compared to before, irrespective of the OCR changes. Here we found that the left vestibular cingulate area (CSv) showed increased FC with the right anterior cingulate cortex (ACC, area 33), the left superior parietal lobule (SPL, area 5Ci), and the thalamus (geniculate nuclei, pulvinar). The CSv, part of the vestibular cortical atlas, is an important region for oculomotor function and for egomotion based on visual motion cues40,41. As reviewed in ref. 42, the ACC has a wide array of functions. In the context of spaceflight, particularly interesting roles and theories of the ACC are world model updating, monitoring of conflicts and errors, instigating behavioral changes resulting from such conflicts and errors, and triggering autonomic responses42. The thalamus is a gateway region for nearly all signaling activity with the cortex, demonstrating its widespread functional roles. The significant cluster in our analysis overlaps with the medial and lateral geniculate nuclei, as well as the pulvinar. The lateral geniculate and pulvinar are specifically known to process visual information, which might explain their connectivity change with the CSv to contribute to visual information processing. One study shows a key causal role of both pulvinar and lateral geniculate nucleus in visually-guided saccades43, underpinning the shared oculomotor function with the CSv. When investigating FC changes of the left and right OP2, we found significant changes with the left AG (IPL, area PGp) and right SPL (area 7A) for the left OP2 as the seed region, and with the right SPL (area 5Ci) for the right OP2 as the seed region. The SPL serves a wide variety of highly integrated functional tasks. The SPL is involved in spatial perception44 and visuospatial attention45. Through extensive work done in studying Macaque SPL and providing comparative analyses with human SPL, there is also an important role for the SPL in visuomotor tasks to interact with the environment46,47. In more general terms, the SPL is highly involved in spatial functions and may, therefore, mediate a part of the spaceflight adaptations to account for the loss of otolith function in microgravity. The connection between OP2 and the AG or SPL in healthy Earth-bound individuals remains largely unknown, though our study reveals changes in their FC following long-duration spaceflight. Lastly, sensorimotor and visual seed regions were chosen to investigate FC changes within regions of other modalities than vestibular, as a complementary approach to investigate sensory reweighting. The left LSM, covering pre- and postcentral gyri, showed increased FC with the left AG (IPL, area PGp). This left AG cluster, however, does not overlap with the one that showed a positive correlation between OCR changes and FC changes with the right OP2. Nevertheless, the proximity of both clusters suggests that the left AG overall shows modulated connectivity with both vestibular and sensorimotor regions. The left LVA showed decreased FC with three cerebellar regions, left and right Crus 1, and right lobule VI. Cerebellar lobule VI is known to have sensorimotor representations of neck, face, and upper limb regions48. Crus I, on the other hand, is rather involved in mental and cognitive processes, among which are visuospatial attention49, and biological motion detection50. One study also shows the involvement of the visual cortex and Crus I in the dizziness sensation of vestibular patients, which the authors suggest has implications for vestibular compensation51. Altogether, our analyses reveal FC changes between our vestibular, visual, and sensorimotor seed regions and higher-order regions with a wide diversity of functions in the brain. It is, therefore, still unclear at this stage which functional roles of these regions are exactly affected. Hence, only speculations can be made based on their known roles from literature and their potential implications for adaptation to spaceflight.

From an integrated perspective, we see that the right OP2 exhibits FC changes with the SPL after spaceflight and that the pre- to postflight FC change with the bilateral AG correlates with changes in peripheral otolith function. Given the importance of the right OP2 in cortical vestibular signaling, these findings demonstrate that spaceflight is affecting the vestibular cortex in parallel to affecting the peripheral function. All cosmonauts in this study are right-handed, making the right cerebral hemisphere dominant for vestibular functions52. However, the left OP2 also shows FC changes, in this case with the left AG and right SPL, demonstrating that not only the dominant side shows changes due to spaceflight. The AG has also been implicated in spaceflight-associated studies, suggesting its function is modulated by altered gravity levels28,30,34. In this study, it was implicated in several results, further supporting the AG’s role in gravity-dependent processing, as has been evident from other studies. From a broader perspective, our results show the effects of spaceflight on many regions in the parietal lobe. These parietal regions include the AG and SPL. Since the parietal lobe is typically involved in spatial processing53 and given that spatial functions are evidently affected by spaceflight, this lobe likely is important in general for most adaptations requiring spatial functions, including the sensory reweighting mechanism. Another general view of our results reveals that several visually related brain regions are also affected by spaceflight. These include the a priori chosen left LVA and area CSv as seed regions, resulting in clusters in the SPL, the thalamic nuclei for visual representations, and partly Crus I. This again gives strong support to the involvement and importance of the visual system in spatial adaptations as a result of a suppressed vestibular system in microgravity. Lastly, regions such as the ACC and AG share a role in matching predicted outcomes based on internal models with actual (multi)sensory feedback, thereby enabling the detection of conflicts and adapting behavior to resolve the conflict.

We also note that the FC changes observed in the control group across repeated MRI sessions are noteworthy and warrant further consideration. While this study was not specifically designed to investigate the effects of static magnetic fields on vestibular or cortical activity, it is possible that repeated exposure to the MRI environment elicits subtle neurophysiological changes. One plausible explanation is magnetic vestibular stimulation, as described by Roberts and colleagues54, whereby the static magnetic field of the scanner can trigger the SCCs and induce cortical responses associated with vestibular processing. Although we did not directly assess vestibular function, this mechanism may partially account for the FC changes observed in controls. However, the influence of MVS in this study would be minimal due to its longitudinal design. As the same scanner and magnetic field strength (3 T) were used at both timepoints, any MVS-related effects would likely be consistent across sessions. Therefore, by comparing scans within subjects over time, any persistent MVS effects would cancel out to a large extent, and the MVS contribution to a systematic bias in the results would be minimal. Furthermore, the study used a 3 T MRI scanner, where MVS effects are minimal compared to higher-field scanners like 7 T. That said, it’s difficult to completely rule out any potential influence. Additionally, some of the FC variability may stem from non-biological sources such as scanner drift, physiological noise, or other technical factors inherent to repeated MRI acquisition. While our preprocessing pipeline included standard procedures to reduce such artifacts, including motion correction and temporal filtering, residual noise cannot be entirely ruled out. Finally, the timing of the MRI scans may account for the observed FC changes in the control group. Preflight controls were scanned in the early morning, while postflight scans took place in the late afternoon, which could influence the brain’s resting state or default mode network.

Several limitations were inescapably tied to this work. First, there was a disparity in the timing of data collection postflight between the fMRI and OCR data, the former being acquired on average 9 days after space, and the latter on average 3 days after space. Since the OCR data acquired 9 days postflight shows no change with baseline, the OCR data acquired 3 days postflight was chosen to reflect the level of peripheral function loss from spaceflight. In this analysis, we assume that cortical reorganization is a longer process, which is also evident in other reports on brain changes after spaceflight24,26,27,28. Second, the small sample size reduced the statistical power to detect subtle effects. These two limitations are a natural consequence of logistical restrictions in accessing the already limited number of people who travel to space and retrospective analyses that merge two independent studies. Another limitation is the poor explanatory power of results regarding altered FC. At this stage, explanations for their direction of effect (increase vs. decrease) and relevance at the behavioral, clinical, or performance level fall short. However, resting-state FC analysis provides a means to study whole-brain functional organization, not limited to imposed tasks or stimuli, therefore allowing the investigation of changes across all functional domains. Third, while our analysis focused on eight predefined seed regions selected based on prior literature and hypotheses aligned with our study aims, we acknowledge that this targeted approach may not capture all possible FC changes. By concentrating on specific regions, we may have missed other potentially relevant connectivity alterations outside our areas of interest. However, this hypothesis-driven strategy builds upon our previous hypothesis-free analyses28, allowing us to focus more precisely on FC changes within core vestibular regions. The final limitation is the absence of direct assessment of perceptual correlates associated with OCR changes, such as self-motion or tilt perception. Consequently, it remains unclear whether the observed alterations in cortical connectivity are related to subjective vestibular experiences following spaceflight. Future research should aim to integrate perceptual measures with OCR and neuroimaging data to more fully elucidate the functional relevance of cortical adaptations to vestibular system changes.

In conclusion, our analyses revealed a link between peripheral otolith function changes and cortical vestibular function changes after spaceflight. The main vestibular cortical hub, the right OP2, is key in these results and shows significant FC changes after spaceflight. Other regions of the vestibular cortical network, the visual system, and the sensorimotor system also show FC changes postflight compared to preflight. The bulk of our results can be placed in the framework of sensory reweighting and provide new and additional information to understand brain adaptations to spaceflight.

Methods

Ethics

Approval for the study was obtained from the European Space Agency Medical Board, the Committee of Biomedicine Ethics of the Institute of Biomedical Problems of the Russian Academy of Science, and the Human Research Multilateral Review Board. All participants, cosmonauts and healthy controls, provided written informed consent, and the investigations adhered to the principles outlined in the Declaration of Helsinki and its subsequent amendments.

Participants

Beginning in February 2014, Russian cosmonauts, who were scheduled for long-duration ISS space missions, could volunteer to participate in two distinct prospective experiments by our group: (1) BRAIN-DTI, which involved acquiring MRI data, and (2) GAZE-SPIN to study otolith function by means of OCR measurements. A total of 14 cosmonauts participated in both experiments and formed the subject pool for the current study. MRI data was obtained on average 89 days (SD = 33 days) before and 9 days (SD = 3 days) after their missions. The OCR measurements were acquired on average 89 days (SD = 39 days) before and 4 days (SD = 2 days) after their missions. The cosmonauts had a median (MAD) age of 46 (3) years, a median (MAD) mission duration of 173 (6) days, and a median (MAD) experience of 165 (165) days in previous missions. Additionally, 19 healthy individuals, matched by age at the group level, were included as controls, with MRI data collected at two timepoints separated by an average of 252 days (SD = 76 days). For cosmonauts, the average time between scans was 269 days (SD = 56 days).

Ocular counter-roll (OCR) measurement

The methodology, detailed in Schoenmaekers et al.14, is summarized here for clarity14. The visual and vestibular investigation system at the Gagarin Cosmonaut Training Center was used to induce the OCR. Cosmonauts, secured on an off-axis rotation chair, were exposed to a centripetal acceleration of 1 G and gravitational acceleration of 1 G, resulting in a theoretical illusion of a 45° roll tilt. Consequently, an OCR was induced, orienting the eyes away from the perceived tilt direction. The OCR measurements were taken 40 s after reaching a constant rotational speed, to avoid SCC signaling. Each measurement lasted 20 s while the cosmonaut fixated on a visual target. Eye movements were recorded via infrared video goggles and analyzed using LabVIEW (National Instruments—11500 N Mopac Expwy, Austin, TX, USA) to quantify OCR in both clockwise and counterclockwise directions for each eye. The OCR was calculated as the average eye torsion over these 20 s recordings, across both eyes and centrifugation direction. The OCR was calculated based on landmarks in the iris structure of the eyes. Upon rotation of the eyeball, like during the centrifugation-induced OCR, this torsion was measured by the amount of pixels that the landmark in the iris structure rotated, using cross-correlation. To avoid false torsion, the subjects fixated a dot in the primary position throughout the measurement55. Data quality was maintained by removing artifacts such as blinks and eyelash interference. The change in OCR pre- to postflight (∆OCR) was used as the variable of interest in the correlation analysis. Noteworthy, OCR data was acquired in cosmonauts only and not for the healthy controls.

Resting-state functional magnetic resonance imaging (rs-fMRI) data acquisition

Resting-state fMRI data were acquired using a 3 T MRI scanner (Discovery MR750; GE Healthcare USA) situated at the Federal Center of Treatment and Rehabilitation in Moscow, Russia. The T2*-weighted echo planar imaging scans were performed with participants positioned head-first and supine, utilizing a 16-channel head and neck array coil. Scan parameters included: echo time = 30 ms, repetition time = 2000 ms, flip angle = 77°, voxel size = 3 × 3 × 3 mm³, and field of view = 192 × 192 × 126 mm (matrix dimension: 64 × 64, 42 near-axial slices). Each session comprised the acquisition of 300 images following 4 dummy scans to establish steady-state conditions. Participants were instructed to keep their eyes closed, allowing their minds to wander without fixation on any particular thought or task, and to avoid falling asleep. Additionally, a high-resolution fast-spoiled gradient echo (FSPGR) 3D T1-weighted image was obtained for anatomical localization purposes, with parameters including: echo time = 3.06 ms, repetition time = 7.90 ms, inversion time = 450 ms, flip angle = 12°, voxel size = 1 mm³, and field of view = 176 × 240 × 240 mm (matrix dimensions: 240 × 240, 176 sagittal slices).

Resting-state fMRI data preprocessing

Preprocessing for each cosmonaut was performed using SPM12 (revision 7771; Wellcome Department of Cognitive Neurology, London, UK) running on Matlab R2023a (Mathworks, Natick, MA, USA). The process involved the following steps: initially, manual reorientation of structural and functional images to the Montreal Neurological Institute (MNI) template was conducted to achieve approximate spatial alignment. Subsequently, slice-time correction, realignment to the first volume, and coregistration to T1-weighted structural images were applied to fMRI images. Segmentation of T1 images into gray matter, white matter (WM), and cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) was performed using the computational anatomy toolbox (CAT12, CAT12.8.2 R2170). The standard segmentation pipeline was followed, which included spatial normalization to MNI space and bias field correction. Using the deformation fields from the CAT12 segmentation output, the functional images underwent non-linear warping and normalization to MNI space, resulting in a final spatial resolution of 3 × 3 × 3 mm for functional and 1 × 1 × 1 mm for anatomical images. Functional images were then smoothed using a Gaussian kernel with dimensions 6 × 6 × 6 mm³ at full-width half-maximum. To reduce noise, the aCompCor (anatomical Component Based Noise Correction Method) method was used, modeling noise influence as voxel-specific linear combinations of multiple empirically estimated noise sources. The noise sources entailed the first 5 principal components from both eroded WM and CSF masks, and signals within these masks were extracted from the unsmoothed functional images. Residual head motion parameters, including three rotation and three translation parameters, plus six parameters representing their first-order temporal derivatives, were included as noise covariates. Outliers were identified based on a global signal threshold of z = 3.0, an absolute motion threshold of 0.5 for translation and 0.05 for rotation, and a scan-to-scan motion threshold of 1.0 for translation and 0.02 for rotation, which were also entered as noise covariates. Subsequently, the functional time series were filtered using a temporal band-pass filter ranging from 0.008 to 0.09 Hz, along with linear detrending.

Connectivity analysis

The study used a repeated-measures design, utilizing the FC toolbox (CONN v22a; https://www.nitrc.org/projects/conn).

For the first analysis (Analysis I), an SBC approach was adopted, using ROIs defined by a cortical vestibular atlas originating from a previous fMRI study performed by Zu Eulenburg and colleagues18,31. A total of 22 vestibular cortical regions were identified, where we selected eight ROIs for correlation analysis (Table 2). These eight regions were chosen due to their specific responses to visual and vestibular signals and their role as central hubs for vestibular processing. Seed-to-voxel correlation maps were created for each ROI and for each subject and time point. Correlation coefficients were transformed to z-scores using Fisher’s r-to-z method. Group-level statistical tests were performed using the general linear model. To investigate changes in connectivity as a result of spaceflight, paired t-tests were performed comparing pre- and postflight data. To investigate correlations between connectivity changes and OCR changes after spaceflight, we performed Pearson correlation analyses.

For the second analysis (Analysis II), a similar SBC approach was used, but this time with cortical sensorimotor and visual ROIs defined by the CONN atlas. We selected seven ROIs, as detailed in Table 2. Group-level statistics were conducted to investigate changes in connectivity from pre- to postflight, whereas no correlation analysis between FC changes and OCR changes was performed.

All statistical tests were performed at the voxel-level. Statistical significance was determined by first applying an uncorrected voxel-level threshold of p < 0.001, followed by a cluster-level threshold of p < 0.05 corrected for FDR. Anatomical labels were defined using the Juelich Brain Atlas. To address multiple comparisons across multiple tested ROIs, a Benjamini-Hochberg correction was used.

Regions-of-interest definitions

Regarding Analysis I, the left and right cingulate sulcus visual (left CSv, right CSv), which exhibit structural and FC with various (multi)sensory and (pre)motor regions engaged in egomotion and locomotion40,56. Seeds three and four were the left and right OP2 (left OP2_PIVC, right OP2_PIVC), serving as a central hub for vestibular processing57. The fifth and sixth seeds were the left and right medial visual posterior sylvian area (left PFcm_VPS, right PFcm_VPS), which contain neurons that exhibit specific responses to the direction of heading in both visual and vestibular systems, with a dominance towards the vestibular modality58. The last two seeds were the nodulus (Nodulus b) and uvula (Uvula b), which play a crucial role in orienting eye velocity of the slow component of the angular vestibulo-ocular reflex (aVOR) to the GIA, and are associated with visual motion processing and the generation of smooth pursuit eye movements59.

For Analysis II, the first three seeds, the left lateral sensorimotor area (left LSM), right lateral sensorimotor area (right LSM R), and superior sensorimotor area (SSM) are responsible for regulating sensory and motor functions. The remaining four seeds, the MVA, OVA, left LVA, and right LVA involved in the receiving, integrating, and processing of visual information.

Data availability

Data can be requested from F.L.W. or I.N. (pending scientific review and a completed material transfer agreement). Requests for the OCR data should be submitted to floris.wuyts@uantwerpen.be or NaumovIvan@gmail.com.

References

Angelaki, D. E. & Cullen, K. E. Vestibular system: the many facets of a multimodal sense. Annu. Rev. Neurosci. 31, 125–150 (2008).

Chandler, D. Weightlessness and microgravity. Phys. Teach. 29, 312–313 (1991).

Hallgren, E. et al. Decreased otolith-mediated vestibular response in 25 astronauts induced by long-duration spaceflight. J. Neurophysiol. 115, 3045–3051 (2016).

Hupfeld, K. E. et al. Brain and behavioral evidence for reweighting of vestibular inputs with long-duration spaceflight. Cereb. Cortex 32, 755–769 (2022).

Hallgren, E. et al. Dysfunctional vestibular system causes a blood pressure drop in astronauts returning from space. Sci. Rep. 5, 17627 (2015).

Young, L. R. & Sinha, P. Spaceflight influences on ocular counterrolling and other neurovestibular reactions. Otolaryngol. Head. Neck Surg. 118, S31–S34 (1998).

Vogel, H. & Kass, J. R. European vestibular experiments on the Spacelab-1 mission: 7. Ocular counterrolling measurements pre- and post-flight. Exp. Brain Res. 64, 284–290 (1986).

Iakovleva, I. I., Kornilova, L. N., Tarasov, I. K. & Alekseev, V. N. [Results of a study of vestibular function and space perception in cosmonauts]. Kosm. Biol. Aviakosm. Med. 16, 20–26 (1982).

Diamond, S. G. & Markham, C. H. Changes in gravitational state cause changes in ocular torsion. J. Gravit. Physiol. 5, P109–P110 (1998).

Clément, G., Reschke, M. & Wood, S. Neurovestibular and sensorimotor studies in space and Earth benefits. Curr. Pharm. Biotechnol. 6, 267–283 (2005).

MacDougall, H. G., Curthoys, I. S., Betts, G. A., Burgess, A. M. & Halmagyi, G. M. Human ocular counterrolling during roll-tilt and centrifugation. Ann. N. Y. Acad. Sci. 871, 173–180 (1999).

Miller, E. F. 2nd & Graybiel, A. Effect of gravitoinertial force on ocular counterrolling. J. Appl. Physiol. 31, 697–700 (1971).

Moore, S. T., Clément, G., Raphan, T. & Cohen, B. Ocular counterrolling induced by centrifugation during orbital space flight. Exp. Brain Res. 137, 323–335 (2001).

Schoenmaekers, C. et al. Ocular counter-roll is less affected in experienced versus novice space crew after long-duration spaceflight. npj Microgravity 8, 27 (2022).

Cebolla, A. M. et al. ‘Cerebellar contribution to visuo-attentional alpha rhythm: insights from weightlessness’. Sci. Rep. 6, 1–10 (2016).

Dieterich, M. & Brandt, T. The bilateral central vestibular system: its pathways, functions, and disorders. Ann. N. Y. Acad. Sci. 1343, 10–26 (2015).

Barmack, N. H. Central vestibular system: vestibular nuclei and posterior cerebellum. Brain Res. Bull. 60, 511–541 (2003).

zu Eulenburg, P., Stephan, T., Dieterich, M. & Ruehl, R. M. The human vestibular cortex. ScienceOpen Postershttps://doi.org/10.14293/S2199-1006.1.SOR-.PPCSDUO.v1 (2020).

Boyle, R. Otolith adaptive responses to altered gravity. Neurosci. Biobehav. Rev. 122, 218–228 (2021).

Kornilova, L. N., Naumov, I. A., Azarov, K. A. & Sagalovitch, V. N. Gaze control and vestibular-cervical-ocular responses after prolonged exposure to microgravity. Aviat. Space Environ. Med. 83, 1123–1134 (2012).

Clarke, A. H., Grigull, J., Mueller, R. & Scherer, H. The three-dimensional vestibulo-ocular reflex during prolonged microgravity. Exp. Brain Res. 134, 322–334 (2000).

Oman, C. M. & Cullen, K. E. Brainstem processing of vestibular sensory exafference: implications for motion sickness etiology. Exp. Brain Res. 232, 2483–2492 (2014).

Cullen, K. E. Vestibular motor control. Handb. Clin. Neurol. 195, 31–54 (2023).

Roy-O’Reilly, M., Mulavara, A. & Williams, T. A review of alterations to the brain during spaceflight and the potential relevance to crew in long-duration space exploration. npj Microgravity 7, 5 (2021).

Klineberg, I. & Eckert, S. The biological basis of a functional occlusion: the neural framework. In Functional Occlusion in Restorative Dentistry and Prosthodontics (eds Klineberg, I. & Eckert, S.) 3–22 (Mosby, 2016).

Demertzi, A. et al. Cortical reorganization in an astronaut’s brain after long-duration spaceflight. Brain Struct. Funct. 221, 2873–2876 (2016).

Pechenkova, E. et al. Alterations of functional brain connectivity after long-duration spaceflight as revealed by fMRI. Front. Physiol. 10, 761 (2019).

Jillings, S. et al. Prolonged microgravity induces reversible and persistent changes on human cerebral connectivity. Commun. Biol. 6, 46, (2023).

Zhou, Y. et al. Disrupted resting-state functional architecture of the brain after 45-day simulated microgravity. Front. Behav. Neurosci. 8, 82743 (2014).

Van Ombergen, A. et al. Intrinsic functional connectivity reduces after first-time exposure to short-term gravitational alterations induced by parabolic flight. Sci. Rep. 7, 3061 (2017).

Raiser, T. M. et al. The human corticocortical vestibular network. Neuroimage 223, 117362 (2020).

Goldberg, J. M. et al. The Vestibular System: A Sixth Sense (Oxford University Press, 2011).

zu Eulenburg, P., Caspers, S., Roski, C. & Eickhoff, S. B. Meta-analytical definition and functional connectivity of the human vestibular cortex. Neuroimage 60, 162–169 (2012).

Radstake, W. E. et al. Neuroplasticity in F16 fighter jet pilots. Front. Physiol. 14, 1082166 (2023).

Taylor, P. C. J., Muggleton, N. G., Kalla, R., Walsh, V. & Eimer, M. TMS of the right angular gyrus modulates priming of pop-out in visual search: combined TMS-ERP evidence. J. Neurophysiol. 106, 3001–3009 (2011).

Farrer, C. et al. The angular gyrus computes action awareness representations. Cereb. Cortex 18, 254–261 (2008).

de Boer, D. M. L., Johnston, P. J., Kerr, G., Meinzer, M. & Cleeremans, A. A causal role for the right angular gyrus in self-location mediated perspective taking. Sci. Rep. 10, 19229 (2020).

van Kemenade, B. M. et al. Distinct roles for the cerebellum, angular gyrus, and middle temporal gyrus in action-feedback monitoring. Cereb. Cortex 29, 1520–1531 (2019).

Seghier, M. L. Multiple functions of the angular gyrus at high temporal resolution. Brain Struct. Funct. 228, 7–46 (2023).

Ruehl, R. M. et al. The human egomotion network. Neuroimage 264, 119715 (2022).

Ruehl, R. M., Ophey, L., Ertl, M. & Zu Eulenburg, P. The cingulate oculomotor cortex. Cortex 138, 341–355 (2021).

Clairis, N. & Lopez-Persem, A. Debates on the dorsomedial prefrontal/dorsal anterior cingulate cortex: insights for future research. Brain 146, 4826–4844 (2023).

Takakuwa, N., Isa, K., Onoe, H., Takahashi, J. & Isa, T. Contribution of the pulvinar and lateral geniculate nucleus to the control of visually guided saccades in blindsight monkeys. J. Neurosci. 41, 1755–1768 (2021).

Lester, B. D. & Dassonville, P. The role of the right superior parietal lobule in processing visual context for the establishment of the egocentric reference frame. J. Cogn. Neurosci. 26, 2201–2209 (2014).

Wu, Y. et al. The neuroanatomical basis for posterior superior parietal lobule control lateralization of visuospatial attention. Front. Neuroanat. 10, 32 (2016).

Gamberini, M., Passarelli, L., Fattori, P. & Galletti, C. Structural connectivity and functional properties of the macaque superior parietal lobule. Brain Struct. Funct. 225, 1349–1367 (2020).

Passarelli, L., Gamberini, M. & Fattori, P. The superior parietal lobule of primates: a sensory-motor hub for interaction with the environment. J. Integr. Neurosci. 20, 157–171 (2021).

Mottolese, C. et al. Mapping motor representations in the human cerebellum. Brain 136, 330–342 (2013).

Kellermann, T. et al. Effective connectivity of the human cerebellum during visual attention. J. Neurosci. 32, 11453–11460 (2012).

Sokolov, A. A. et al. Structural and effective brain connectivity underlying biological motion detection. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 115, E12034–E12042 (2018).

Helmchen, C. et al. Effects of galvanic vestibular stimulation on resting state brain activity in patients with bilateral vestibulopathy. Hum. Brain Mapp. 41, 2527–2547 (2020).

Dieterich, M. et al. Dominance for vestibular cortical function in the non-dominant hemisphere. Cereb. Cortex 13, 994–1007 (2003).

Sack, A. T. Parietal cortex and spatial cognition. Behav. Brain Res. 202, 153–161 (2009).

Roberts, D. C. et al. MRI magnetic field stimulates rotational sensors of the brain. Curr. Biol. 21, 1635–1640 (2011).

Moore, S. T., Haslwanter, T., Curthoys, I. S. & Smith, S. T. A geometric basis for measurement of three- dimensional eye position using image processing. Vis. Res. 36, 445–459 (1996).

De Castro, V. et al. Connectivity of the cingulate sulcus visual area (CSv) in macaque monkeys. Cereb. Cortex 31, 1347–1364 (2021).

Zhao, B., Wang, R., Zhu, Z., Yang, Q. & Chen, A. The computational rules of cross-modality suppression in the visual posterior sylvian area. iScience 26, 106973 (2023).

Xu, P., Chen, A., Li, Y., Xing, X. & Lu, H. Translational physiology: medial prefrontal cortex in neurological diseases. Physiol. Genom. 51, 432 (2019).

Cohen, B., John, P., Yakushin, S. B., Buettner-Ennever, J. & Raphan, T. The nodulus and uvula: source of cerebellar control of spatial orientation of the angular vestibulo-ocular reflex. Ann. N. Y. Acad. Sci. 978, 28–45 (2002).

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank all participating cosmonauts and crew members. This study was funded by the Belgian Science Policy (Prodex), ESA-AO-2004-093. The work of L.K., D.G. and I.N. is supported by the Russian Academy of Sciences (FMFR-2024-0033). C.S. is a Research Fellow of the Research Foundation Flanders (Belgium, FWO-Vlaanderen, Grant 1SF9122N and 1SF9124N).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

C.S., S.J., D.G., I.N., E.T., I.R., E.P., A.R., L.M., I.N. and F.L.W. contributed to data acquisition; C.S., S.J. and S.M. contributed to data analysis; C.S., S.J. and S.M. contributed to data interpretation; C.S. contributed to drafting the paper; and C.S., S.J., S.M., D.G., I.N., E.T., I.R., E.P., A.R., L.M., I.N., P.Z.E. and F.L.W. contributed to a substantial revision of the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Schoenmaekers, C., Jillings, S., Mortaheb, S. et al. Neural correlates of vestibular adaptation in cosmonauts after long duration spaceflight. npj Microgravity 11, 71 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41526-025-00528-2

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41526-025-00528-2