Abstract

Spaceflight Standard Measures is an integrated research study designed to characterize how spaceflight affects the health and performance of astronauts. Standardizing the research methods allows for robust monitoring of individuals and allows comparison between crewmembers of different missions of various durations. This manuscript reviews the objectives of the Spaceflight Standard Measures project, and details how each disciplinary component is used to monitor spaceflight-induced human risks. It also covers the timeline of data collection, the methods used to analyze the data, and the process for requesting access to the data. With the impending return to lunar operations and exploration of deep space, an urgent need exists for high-quality, multidisciplinary investigations to inform programmatic and operational decisions. The Spaceflight Standard Measures model provides a standardized, flexible research approach, fostering collaboration across agencies to create a strong evidence base that can be used to safely advance human spaceflight into multiplanetary exploration.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Characterizing how humans respond to hazards of the spaceflight environment is paramount to informing programmatic and operational decisions that affect the safety and success of a space program. Thus, the National Aeronautics and Space Administration (NASA) is committed to biomedical research efforts aimed at generating an evidence base that can inform technical standards, establish research priorities, and facilitate the evaluation of mission risks1. When evaluating risks, an astronaut is conceptualized as a “human system,” defined here as the aggregate of all physiological, psychological, and phenomenological elements that comprise a crewmember’s health and performance. Additionally, there are five features of the space environment that are recognized as hazardous to the human system: space radiation, microgravity, distance from Earth, and a hostile closed environment that is associated with isolation and confinement2.

These five features of the space environment are believed to be the root cause of unfavorable health or performance outcomes known as human-system risks. There are currently 30 active human-system risks being evaluated for multiple design reference mission (DRM) profiles3. DRMs are operational concepts for human spaceflight missions of various durations, destinations, and operational conditions that are used to assess a specific risk for a specific mission. DRMs range from free-flyer missions in low-earth orbit (LEO) shorter than 30 days, to interplanetary missions to Mars lasting an estimated three years. The human-system risk concept allows scientists to not only consider performance impacts during a mission, but also the long-term health consequences after a mission.

NASA’s Human System Risk Board evaluates each of the 30 recognized risks by reviewing the best available evidence and generating a risk assessment based on a “likelihood times consequences” formula (LxC). “Likelihood” represents the probability that an undesired outcome will occur, and “consequences” is the impact that the undesired outcome will have on the health and/or performance of a crewmember. This LxC formula informs a risk posture, which is NASA’s formal stance on a human system risk within the context of specified mission parameters4.

NASA’s Human Research Program (HRP), part of the Space Operations Mission Directorate (SOMD), is one of the primary programs that generate evidence to inform these human-system risk assessments. The HRP is responsible, among other things, for conducting research to characterizes risks, developing technologies, and validating countermeasures to support the continued exploration of space5. Spaceflight Standard Measures (SSM) is an HRP-sponsored study that (a) supports these various research objectives; (b) is designed to simultaneously monitor multiple human-system risks; (c) provides context for concurrent experiments; and (d) generates data that can be retrospectively utilized by researchers within and outside of the NASA domain (Fig. 1). The objective of this review is to share the established research practices of SSM, promote the standardization of research methods, and inform scientists on how they can utilize the SSM data to support their research interests.

Experimental Design

“Standard Measures” are defined here as a set of uniform research tests or measurements, collected in the same way each time, that monitor consented participant’s health and performance metrics across multiple domains of the human system. Since the year 2000, fewer than 300 astronauts have stayed on the International Space Station (ISS). This limited pool of potential participants is an inherent limitation of spaceflight research6,7. One of the primary benefits of implementing a standardized test battery is the ability to group subjects of different studies to increase the sample size. Pooling subjects to achieve a larger sample size enables more robust analysis of population-level responses and reduces the probability of a Type II error (missing a “real” effect), which is necessary to evaluate the effectiveness of countermeasures.

Furthermore, SSM adopts a multidisciplinary, repeated-measures design to improve the data yield per subject and to identify temporal adaptations through longitudinal analysis. Data collection takes place 6 months and 3 months before flight. During short-duration missions (up to 105 days), a single data collection is scheduled midway through the mission. During standard-duration ISS missions (105–240 days), data is collected during the first month, at mid-flight, and during the last month of the mission. An additional in-flight data collection is scheduled for extended-duration missions ( > 240 days). After flight, data is collected on the day of return at the landing site, and then one day, one week, and one month later (see Supplementary Tables 1 to 3). SSM are collected from NASA, ESA, JAXA, and CSA astronauts flying on board the International Space Station (ISS), as well as individuals participating in commercial private astronaut missions to the ISS or free-flyer destinations. Data from these crewmembers are stored in the Standard Measures repository within the NASA Life Sciences Data Archives as described in greater detail in subsequent sections.

SSM is not a hypothesis-driven study. Instead, SSM implements a descriptive and exploratory design to achieve the following scientific objectives:

-

Simultaneously monitor several high-priority human-system risks.

-

Characterize and compare the response of crewmembers to various mission durations.

-

Evaluate the effectiveness of countermeasures and/or the impact of changes to in-flight capabilities.

-

Generate a repository of data that can support concurrent experiments and the development of novel hypotheses.

Six broad areas of investigation are included in SSM, which are referred to as “domains” (Fig. 2). These domains were selected due to their relevance to high priority human-system risks within the HRP’s research portfolio. These domains include Behavioral Health & Performance, Cellular Profile, Biochemical Markers, Muscle Performance, Microbiome, and Sensorimotor Standard Measures. Each of the SSM domains encompasses multiple scientific disciplines and is described in detail in the subsequent sections. Each of the measures within these disciplines was chosen because it is relevant to spaceflight-induced risk to health or performance, and has been established in the clinical, analog, and/or spaceflight literature. The parameters included in the SSM were compiled by the HRP Element Science Working Group (ESWG) and validated through prior space research studies. Each year, the ESWG conducts reviews of standard test batteries, test timing and methods, and relevant clinical data. Based on these reviews, parameters may be added or removed from the SSM test battery.

The inner ring includes the study domains, secondary ring includes the scientific disciplines, the tertiary ring includes human-system risks addressed by SSM. Note, the hazards “closed & hostile environment” and “isolated and confined” were combined for efficiency. IMTP: isometric mid-thigh pull test. Figure created with BioRender.com. Image credit: NASA, ESA, CSA, STScI, Webb ERO Production Team; CC BY-NC 2.0.

An agreement with NASA’s Space Medicine Operations Division permits the sharing of select medical data with the SSM project. The acquisition of this shared medical data, which includes bone densitometry8, radiation exposure9, and neuro-ocular responses to spaceflight10, expands the risks monitored by the SSM study (Table 1).

Table 2 provides a description of the risks, domains and disciplines associated with SSM, as well as the tests, measures, and the flight phases during which the measures are collected. Detailed descriptions of the data collection schedules and the measures within each discipline are provided in Supplementary Tables 1-3.

Behavioral health and performance

Spaceflight is an isolated, confined, and extreme environment that directly impacts an astronaut’s psychological health and functioning. The Behavioral Health and Performance (BHP) domain monitors human-system risks related to sleep quantity and quality, circadian rhythmicity, workload, habitability, and team functioning. To monitor various aspects of behavioral health and performance the following SSM are collected: a personality test using the International Personality Item Pool—Neuroticism, Extraversion, Openness (IPIP-NEO), the Cognition Test Battery (CTB), actigraphy, sleep logs, and end of day surveys.

Personality test

The International Personality Item Poool (PIP-NEO-120 version) is a 120-item questionnaire based on the five-factor model of personality (neuroticism, extraversion, openness, agreeableness, and conscientiousness) used to establish a baseline profile for each crewmember before flight11. The mean factor scores for each crew member are collected using a 7-point Likert scale, the anchors being “very inaccurate (1)”, “neutral (4)” and “very accurate (7)”. Individuals high in neuroticism are characterized as anxious and irritable, whereas those low in neuroticism are characterized as more emotionally stable. Individuals high in extraversion can be described as excitable, sociable, talkative, assertive, and emotionally expressive. Individuals high in openness are described as adventurous, creative, and willing to explore new experiences. Individuals high on agreeableness are described as trusting, altruistic, kind, affectionate, and tend toward prosocial behaviors. Finally, individuals high in conscientiousness are described as thoughtful in their actions, exhibit good impulse control, and goal-directed behaviors, and are organized and mindful of details. The personality profiles of astronauts are generally low in neuroticism and high in agreeableness and conscientiousness12.

Cognition test battery (CTB)

Cognition is tested using the CTB software tool, which consists of 10 short neurocognitive tests. These tests are designed to measure different types of thinking skills, such as memory, learning, problem-solving, attention, and how people make decisions under stress13. The 10 tests include recognizing emotions, solving patterns, matching shapes, remembering objects, and reacting quickly to visual cues.

The CTB assesses how fast and how accurately a person can complete the tests. Speed is usually measured by how quickly someone responds, except in one of the tests (called the psychomotor vigilance test) where a special formula is used to better detect the effects of being tired. Accuracy is generally measured by how many answers are correct, but a few of the tests use special scoring systems. For example, one test gives partial credit depending on how close the answer is, and another averages accuracy across different types of questions to give a more complete picture. One test, the Balloon Analog Risk Task, doesn’t measure accuracy at all—instead, it looks at how willing someone is to take risks by seeing how many times they “pump” a virtual balloon before it pops14.

The results from five studies involving a total of 87 astronauts who repeatedly completed the CTB and participated in semi-structured debriefs, indicated a high level of user acceptability15. Recent CTB analyses of 25 professional astronauts during standard duration missions on the ISS found no evidence of a systematic decline in overall cognitive function; however, significant reductions in processing speed, working memory, and sustained attention occurred during flight16. The evidence from this analysis was subsequently used, in conjunction with other data, to update the human system risk related to deficits in cognitive performance.

Sleep logs and actigraphy

Circadian desynchronization and reduced sleep duration are common among crewmembers of ISS missions17. Evidence from studies conducted in conditions analogous to spaceflight suggests sleep deprivation has significant impacts on performance, including reduced accuracy of complex psychomotor tasks such as docking a spacecraft18. Self-reported questionnaires are designed to assess a crewmember’s subjective sleep quality, stress level, and fatigue, as well as their use of sleep medications. The sleep survey format consists of free-response answers on a visual analog scale, with item-specific anchors and raw values that vary between 0 and 100 or −100 to +100, depending on the item.

To monitor sleep-wake behaviors, study participants wear an actigraphy device that tracks accelerations caused by wrist movements. During flight, actigraphy data are collected for 14-day periods that are spaced 60 days apart. During these collection periods, actigraphy is performed 24/7, except during extravehicular activities or other operational constraints. The actigraphy analysis software includes settings for selecting a wake threshold and for detecting sleep intervals and sleep onset and end. The sleep variables measured include the following:

-

Minutes to fall asleep (onset latency)

-

Minutes spent awake after sleep onset

-

Number of wake bouts during a sleep period (awakenings)

-

Total sleep duration relative to time in bed (sleep efficiency)

-

Minutes spent resting after waking (snooze duration)

These variables are used to calculate total nap duration, total sleep duration (nap and sleep combined), and total time in bed over a 24-hour period. Additionally, the actigraphy device records the subject’s exposure to white, red, green, and blue light in lux over the same 24-hour period.

Sleep studies in astronauts are essential because spaceflight disrupts normal sleep due to factors such as exposure to altered light cycles and demanding schedules. Poor sleep can impair cognitive performance, emotional regulation, and physical health, increasing the risk of errors during missions19. The SSM data helps identify these challenges and supports the development of countermeasures—such as light therapy or optimized operational schedules—to improve sleep, maintain alertness, and protect astronaut well-being during long-duration spaceflight.

End of the Day Survey

This questionnaire provides valuable information on neurobehavioral function, such as team cohesion and performance, team processes, and crew living within the ISS. Subject must rate their level of agreement with statements regarding their crew on a scale from 1 to 7 (Table 3). Preliminary findings from six-month ISS missions reveal significant variability in individual responses among astronauts. Team cohesion and group dynamics tend to decline around mid-mission, coinciding with increased reports of stress, fatigue, and irritability20.

Biochemical markers

Biochemical markers are essential for monitoring how astronauts’ bodies respond to the unique challenges of spaceflight. Responses include changes in nutrient metabolism and health effects such as anemia, oxidative stress, and vision problems. By linking these markers to diet, crewmembers can adjust their nutritional intake to prevent deficiencies, support individual needs, and maintain health, which will be especially critical on planetary missions that have limited medical support. However, providing food that is both palatable and nutritionally adequate is challenging due to constraints such as limited re-supply opportunities, minimal storage and preparation capabilities, and the difficulty of growing fresh produce on the ISS.

The Biochemical Markers domain of SSM monitors two human-system risks: crew illness due to inadequate food or nutrition and cardiovascular adaptations. Research indicates that the space environment can directly alter blood chemistry, including changes in hemoglobin levels and oxidative stress markers, which in turn influence key nutritional factors such as iron metabolism and antioxidant function21. More recent findings show that specific genetic variants related to one-carbon metabolism may impact B-vitamin status in crewmembers and increase the risk of developing vision-related issues during spaceflight. These findings highlight the critical role of ongoing nutritional monitoring in space22,23,24.

To monitor various aspects of biochemistry, blood is drawn before, during, and after flight, and a 24-h urine collection is completed before and after flight. The blood samples (both plasma and serum) are analyzed for over 50 analytes that span multiple physiological systems, including bone and cardiac biomarkers, a complete blood count, an extensive metabolic panel, and a comprehensive chemistry panel. Urine samples are analyzed for approximately 20 analytes to develop a renal stone profile and identify the levels of various biochemicals, minerals, and electrolytes.

All crewmembers fast before collections and refrain from exercise for at least 8 h prior to the blood draws. Before and after flight, blood (15.7 mL) is collected in two 5-mL serum separator tubes (SST), a 3 mL EDTA tube, and a 2.7 mL lithium-heparin tube. During flight, 15 mL blood is collected in two 7.5 mL SSTs. The blood is allowed to coagulate for 30 minutes after the blood is drawn, and samples are then centrifuged at 3500 rpm. After centrifugation, samples are placed in a -80 °C laboratory freezer (pre- and post-flight samples) or are transferred to the -96 °C ISS freezer (inflight samples) where they are stored until the samples are returned to Earth via a cargo or manned vehicle return such as the SpaceX Dragon capsule. The samples are maintained in conditioned storage from splashdown until inventory and transferred to Nutritional Biochemistry Laboratory personnel.

Some pre- and post-flight analyses are completed real-time (i.e., on the day of the blood draw) because they cannot be measured in samples that have been frozen. These tests include complete blood count (including white blood cell count, neutrophils, lymphocytes, monocytes, eosinophils, basophils, red blood cell count, reticulocyte count, platelet count, mean platelet volume, platelet distribution width, hemoglobin, and hematocrit). The remaining samples are processed and frozen until they are batch analyzed alongside flight samples, ensuring that handling of the ground samples matches inflight sample processing.

With the exception of the tests listed above and the tests performed by the Space Medicine Operations Division, all samples are batch analyzed. After the samples are returned to the laboratory, they are thawed, aliquoted, and re-frozen until they are batch analyzed. Blood analysis includes serum urea nitrogen, bilirubin, glucose, serum 1,25-dihydroxyvitamin D, serum 25-hydroxyvitamin D, bone-specific alkaline phosphatase, calcium, liver enzyme alanine transaminase (ALT), liver enzyme aspartate transaminase, total alkaline phosphatase, sodium, potassium, chloride, total protein, albumin, creatinine, osteocalcin, undercarboxylated osteocalcin, intact parathyroid hormone, osteoprotegerin, osteoprotegerin ligand/RANKL, leptin, insulin-like growth factor 1, sclerostin, and N-terminal propeptide of type I procollagen.

The blood draws before and after flight are collected within the same 24-hour period as the urine collections. A 24-hour, void-by-void urine collection is completed using 500-mL bottles. Samples are kept in a cooler containing ice packs until delivery to the Nutritional Biochemistry Laboratory at NASA’s Johnson Space Center (JSC) for processing and analysis. There are no inflight urine collections. Pre- and post-flight urine analysis includes sodium, potassium, creatinine, pH, 24-hour volume, calcium, phosphorus, magnesium, uric acid, citrate, sulfate, oxalate, calcium oxalate supersaturation, calcium phosphate supersaturation, sodium urate supersaturation, struvite supersaturation, and uric acid supersaturation.

Each of the tests above is performed on separate aliquots from the 24-h urine pool. Aliquots for calcium, phosphorus, and magnesium are acidified with 1 drop of 6 N hydrochloric acid (HCl) in 3 mL of urine. Each of the aliquots for citrate, sulfate, oxalate, and supersaturation tests has 6 drops of 6 N HCl added to 10 mL of urine. Additionally, the uric acid aliquot has 1 drop of 2.5% sodium hydroxide added to 3 mL of urine.

A standardized survey is used to capture the crewmember’s exercise regimen and medication use during the seven days prior to the sample collections to provide further context to the analysis results. The number of samples collected and the total volume per collection are ultimately determined by the duration of the crewmember’s flight. The logs and analyte data are synthesized to provide a complete profile of a crewmember’s nutritional status before, during, and after a mission.

Cellular profile

The risk of adverse health events due to a dysregulated immune response is the primary human-system risk monitored by the Cellular Profile domain of SSM. The effects of spaceflight on the immune system have been well characterized with documented dysregulation of both the innate (non-specific defense) and adaptive immune systems (antigen-specific defense)25. During and after missions to the ISS, elevated levels of stress hormones, reduced immune cell counts, and impaired immune cell function have been detected in astronaut’s blood and saliva. This dysregulated state can result in clinically relevant cases of viral reactivation, such as the Epstein-Barr Virus (EBV)26. To examine how spaceflight affects the immuno-virological status of crewmembers, both saliva and blood samples are collected as part of SSM before, during, and after spaceflight27. These samples are analyzed to assess viral shedding, stress hormone levels, peripheral leukocyte distribution, cytokine levels, and T cell function. Pre- and post-flight specimens are left at room temperature for 32 hours before processing to approximate the time required for the inflight samples to travel from the ISS to JSC. Although this time is shorter than the actual voyage time (by approximately 5 hours), previous analyses indicate this difference does not cause a meaningful change to the resulting data.

The following quantitative assessments of immunology are performed for Cellular Profile:

-

From whole blood, leukocyte subsets are quantified, and T cell differentiation status is determined via multi-parametric flow cytometry.

-

Peripheral blood mononuclear cells are isolated and stimulated with a panel of mitogens:

-

○

Staphylococcal enterotoxins A and B, anti-CD3 and anti-CD28 antibodies, for 24 hours to determine T cell function.

-

○

Lipopolysaccharide, anti-CD3 and anti-CD28 antibodies, and PMA + Ionomycin, for 48 hours to quantify the secretion of cytokine and chemokine protein mediators.

-

○

These assays rely on a multi-parametric flow cytometer (Gallios instrument, Beckman Coulter) and a Luminex Magpix system (EMD Millipore). Plasma is cryopreserved for cytokine analysis. Immune cells are characterized via multi-parametric flow cytometry for phenotype and 24-hr activation. Supernatants from 48-hr cultures are cryopreserved for future analysis of cytokine secretion. The flow cytometry data are analyzed at every time-point, but each crew member’s data is synthesized via longitudinal analysis only at the conclusion of their sampling schedule.

For virology, saliva samples are collected first thing in the morning before eating or drinking and then stored frozen until processing. Salivary DNAs are extracted using a Qiagen extraction kit. Epstein Barr virus, Herpes simplex virus 1 and Varicella zoster virus are detected by real-time polymerase chain reaction (PCR). Glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase (GAPDH) is included as a positive control for each PCR assay.

A standardized questionnaire titled “Cellular Profile Survey” is completed after flight to inquire about crewmember’s allergies, rashes, hypersensitivities, infections, and wound healing. Once data collection is complete, the data from these various samples and survey data are aggregated to generate an immunological and virological profile for each crewmember.

Results obtained to date indicate a low, but real, incidence of clinical symptoms consistent with immunologic disease among crewmembers during spaceflight. For example, the frequency of allergy and hypersensitivity symptoms among astronauts during spaceflight is higher than in ground control subjects. Antihistamines remain the second-most prescribed medication on board the ISS. Furthermore, data from flight studies suggest that during spaceflight, astronauts exhibit persistent, low-level inflammation. All of these morbidities may be manifestations of altered immune function. Persistent human immune dysregulation manifests severe pathogenesis. In astronauts, the reactivation of latent herpes viruses throughout spaceflights relates directly to chronically depressed T cell function. If prolonged exposure to the space environment perturbs the stability of multiple aspects of the immune system, then it may confer a serious clinical risk to crew members during exploration-class missions that will be of an unprecedented duration28,29.

Microbiome

The human microbiota includes all microorganisms that inhabit a specified region of the body (i.e. skin, saliva, or gastrointestinal tract). These microorganisms produce several bioactive molecules such as short chain fatty acids, neurotransmitters, and small amounts of B vitamins that influence a variety of physiologic systems both locally and systemically. Alterations in the taxonomic composition of astronaut’s microbiome have been identified during ISS missions30. These changes are correlated with altered cytokine profiles that may increase the risk of skin hypersensitivities, infections, and other inflammatory disease states31. To determine spaceflight-induced microbiome changes and the implications of those changes, the Microbiome domain of SSM monitors the human-system risk related to interactions between a host and microorganisms.

Skin, nasal, saliva, and fecal samples are collected before, during, and after a mission. Sample collection methods are non-invasive and require minimal crew time. Body swabs are performed on the forearm, forehead, nostrils, and a control surface using swabs pre-moistened with 0.85% saline. At each collection time point, saliva samples are collected once a day on four consecutive days using oral swabs. Stool sampling kits are used to collect the entire fecal material during ground sessions, whereas fecal swabs immediately after defecation are used to collect samples during in-flight sessions. Microbial DNA is analyzed, using 16S sequencing techniques, so that the types and concentrations of microorganisms can be calculated to monitor temporal changes in a crewmember’s microbiome32.

A brief “Health and Hygiene Survey” is completed before each collection session to provide context for the sequencing results. Together, these data help monitor changes to an astronaut’s microbiome throughout all phases of a mission.

Studies of astronauts’ microbiome are crucial because the microbiome plays a vital role in maintaining immune function, mental health, metabolism, and protection against infection—all of which can be significantly affected during spaceflight. The extreme environment of spaceflight, including microgravity, altered diets, isolation, and psychological stress, can disrupt the balance and diversity of the gut microbiome. These disruptions may contribute to immune dysregulation, changes in nutrient absorption, and even cognitive or emotional challenges through the gut-brain axis. Additionally, the confined and recycled atmosphere in a spacecraft increases the risk of microbial transmission; therefore, it is important to monitor how the astronaut microbiome evolves and interacts with the environment. Determining these changes not only supports astronaut health, but it also informs the development of personalized countermeasures, such as probiotics or dietary adjustments33. Furthermore, microbiome research is essential for planetary protection efforts that will prevent both forward contamination of other celestial bodies and backward contamination of Earth. Overall, microbiome studies are a key component of ensuring human health and mission success during long-duration space exploration.

Sensorimotor standard measures

During launch into space and return to Earth, crewmembers experience transitions in gravitational field strength that have considerable effects on their sensorimotor system. Actual and simulated gravitational perturbations have been shown to produce alterations in vestibular function, visual processing, and proprioception that can result in disorientation, imbalance, and motion sickness34. These physiological alterations and associated symptoms can have direct impacts on health, performance, and flight operations, including an increased risk of syncope and the inability to carry out mission-critical tasks such as piloting, docking, and safely egressing a vehicle35. Sensorimotor Standard Measures monitor the human-system risk involving impaired ability of crewmembers to perform essential tasks due to alterations in vestibular and sensorimotor function. To monitor how the sensorimotor system adapts to spaceflight, this SSM domain includes a battery of three functional tests and two motion sickness evaluations.

An astronaut’s performance of mission-critical tasks is tested immediately after landing and compared with their performance of the same tasks before the flight. These tasks include a sit-to-stand and walk-and-turn test, a tandem walk test, and a recovery-from-fall test. Inertial motion units (IMU) worn by the crewmembers measure 6 degrees of freedom body movements. A gait mat measures their balance and locomotion capabilities, and blood pressure monitors capture their hemodynamic responses.

The sit-to-stand and walk-and-turn test involves a crewmember rising from a seated position as quickly as possible, without using their hands, and standing stationary for 10 seconds. The crewmember then walks as quickly and safely as possible towards a cone four meters away. They walk around the cone and return to a seated position in the chair. On their way to and back from the cone, crewmembers step over a 30-cm obstacle. Three trials are performed for this test. Measures of performance during this test include the time lapse from sit to stand, the time required for walking, and the yaw angular velocity of the trunk while walking around the cone.

For the sit-to-stand part of the test, the time elapsed between the command to stand and the achievement of a stable posture is used as the measure of performance. The IMU data are used to determine when a stable posture is achieved. The start and end of the stand are defined using a threshold of five times the standard deviation of the absolute angular trunk pitch velocity during the stable period at the end of the stance. For the walk-and-turn part of the test, the start and end of the walk are defined when the resultant acceleration from the trunk IMU is above or below, respectively, five times the standard deviation of the stance resultant acceleration. The turn rate is calculated during the cone turn only. The start of the cone turn is based on a threshold of five times the standard deviation of the yaw angular velocity of the trunk relative to the straight-line walk. The end of the cone turn is defined as a greater than 165 degrees turn from the position at the start of the cone turn.

During the tandem walk test, crewmembers are asked to walk 10 heel-to-toe steps with their arms folded across their chest. Two trials are performed with eyes open and two trials with eyes closed. Each trial is continuously reordered for scoring and analysis after the test is completed. Each trial is recorded by video. Three reviewers independently examine the videos to determine the number of correct steps during each trial. Each subject’s scores are pooled from the videos of all their trials across all sessions, and then the order is randomized to minimize reviewer bias based on their awareness of the session. After all the reviewers have completed their assessments, the median value is used to determine the percent of correct steps for that trial. A higher percent of correct steps directly relates to better performance.

During the recovery-from-fall test, crewmembers lie prone for two minutes while a brachial blood pressure measurement is taken. They then stand as quickly as possible following a verbal command from the test operator and remain in a quiet standing position for three and a half minutes. The time elapsed between the command to stand and the achievement of a stable posture is used as the measure of performance, and the same IMUs and methods are used as in the sit-to-stand test. When they are standing, another brachial blood pressure measurement is taken to assess the hemodynamic responses of the positional change and identify instances of orthostatic tolerance.

Throughout these tests, an operator repeatedly asks the crewmembers to rate their level of motion sickness using a 0 to 20 scale with 20 being the most severe rating. Separately, astronauts complete a motion sickness questionnaire during and after flight to report any symptoms experienced during the first three days of launch and during return, medication used to treat these symptoms, and the perceived effectiveness of these medications to alleviate motion sickness symptoms. Collectively, these data help monitor sensorimotor adaptations to spaceflight and the relevant human-system risks.

The sensorimotor tests conducted on 19 astronauts before their flight, a few hours after landing, and then 1 day and 6 to 11 days later show that adaptation to long-term weightlessness causes deficits in functional performance immediately after landing that can last for up to one week34. Research in this area helps identify the mechanisms behind these changes and supports the development of effective countermeasures, such as balance training, exercise regimens, and adaptive strategies to support safe movement during spaceflight and during re-adaptation to gravity36,37. This knowledge is essential for maintaining astronaut performance, safety, and independence during long-duration missions and post-mission recovery.

Muscle performance (isometric mid-thigh pull test)

Multi-system deconditioning including reductions in skeletal muscle mass and peak force production has been identified in astronauts after long-duration spaceflight38. The rate and magnitude of spaceflight-induced loss of muscle mass are different for individual body regions and are highly variable between crewmembers. Not only can deconditioning impede a crewmember’s ability to perform essential tasks, but it may also have undesired health consequences. Paraspinal muscle atrophy, for example, may increase the risk of spinal injuries such as intervertebral disc herniation39. Additionally, spaceflight-associated deconditioning appears to negatively affect a wide range of musculoskeletal tissues including muscle, cartilage, and bone and is only partially mitigated through exercise countermeasures40,41.

The isometric mid-thigh pull (IMTP) domain of SSM evaluates the risk of performance decline due to reduced muscle mass, strength, and endurance. The IMTP is a validated and reliable full-body strength test that measures peak force production using a force plate, which generates a force-over-time curve during the test. Ground-based sessions are conducted using force plates and a specialized exercise rig at the Exercise Physiology and Countermeasures Laboratory at JSC. In-flight tests are performed on the ISS advanced resistance exercise device. This test enables scientists to track changes in peak force production throughout all phases of a mission.

IMTP strength testing is important for astronaut health because it provides a simple, effective way to monitor muscle strength, which typically declines with exposure to microgravity. Because muscles such as the quadriceps and hamstrings weaken during spaceflight, IMTP helps assess this loss and evaluate the effectiveness of countermeasures such as exercise and nutrition. The IMTP test is easy to perform in space, requires minimal equipment, and is crucial for ensuring astronauts can perform mission tasks and recover safely after returning to Earth or adapting to other gravity environments.

Data archiving

The logistical challenges of implementing scientific research on astronauts include their high workloads and congested pre-flight travel schedules, limited on-orbit sample processing capabilities, and limited crew availability immediately after flight. Because of these challenges, the SSM study receives considerable support from the Research Operations and Integration (ROI) program element at JSC to implement its science in a way that deconflicts with operations as much as possible. The collaborating ROI experiment teams interface directly with the crew and their increment science coordinators to ensure SSM science is implemented at the highest feasible standard throughout all phases of a mission. Once the SSM samples are acquired, the personnel in the Biomedical Research and Environmental Sciences Division of the Human Health and Performance Directorate associated with each discipline process the samples and analyze the data. After analysis is completed, a data report and a data file are generated for each discipline. The SSM science team is responsible for synthesizing the siloed reports into a single cohesive report that includes all consented participants of a given ISS increment. This report is delivered to NASA HRP’s Chief Scientist for review.

SSM has a dedicated data scientist who then further processes the data and harmonizes each of the discipline-specific data files into a unified format. The Data Element Dictionary for each of the SSM disciplines is shown in Supplementary Table 4. This formatted data is then archived into the NASA Life Sciences Data Archive (LSDA) and into the Information Management Platform for Data Analytics and Aggregation (IMPALA). The SSM database has been available since 2019 and continues to be updated, as there is no fixed target for the number of astronauts included. NASA is coordinating efforts to share this data with the archives of other space agencies.

The LSDA at NASA’s JSC is the primary repository for human spaceflight-related life sciences data. Established in the early 1990s, the LSDA was created to systematically collect, preserve, and distribute data from NASA’s HRP and its predecessors. This archive includes a comprehensive range of datasets from human spaceflight missions that encompasses physiological measurements, behavioral assessments, and biomedical analyses. IMPALA is an open-source structured query language (SQL) engine designed for real-time analytics on large datasets. IMPALA allows for efficient analysis and data interchange without the need for data migration, making it a valuable tool for organizations working with big data42.

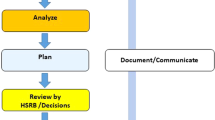

Data requests

Researchers can access the LSDA through the NASA Life Sciences Portal (NLSP) at https://nlsp.nasa.gov/explore/lsdahome. The SSM team works closely with NLSP archivist to ensure human subject data is coded, encrypted, and appropriately stored on secured servers behind NASA firewalls. One primary aim of the SSM project is to generate evidence in a data repository that can be retrospectively accessed by both NASA and non-NASA investigators. Figure 3 shows the flow of data from crew consent, data collection and analysis to data archiving.

To request human research data from NASA, investigators must submit a formal access request including Institutional Review Board (IRB) approval, institutional endorsement, and acceptance of data use agreements, ensuring compliance with federal human subject protection regulations. Additionally, NASA reserves the right to publish the data first within one year of receiving mission data. Any scientific or technical publication using SSM data must acknowledge “NASA Human Research Program Standard Measures” as the data source.

The LSDA team provides the appropriate processes, tools, and secure infrastructure to archive and disseminate experimental data while complying with applicable rules, regulations, policies, and procedures governing the management and archive of sensitive data and information. The LSDA team disseminates data and information to the public or to authorized personnel either by providing public access to information or via an approved request process for information and data from the LSDA in accordance with NASA HRP and JSC Institutional Review Board direction.

In addition to retrospective requests, SSM study data can be accessed through prospective data sharing agreements (DSAs) with both NASA and non-NASA investigators. DSAs provide a broad physiological context to concurrent experiments that may be of a more focused scope of inquiry (Fig. 4). This is one reason why SSM was included in NASA HRP’s Complement of Integrated Protocols for Human Exploration Research (CIPHER) experiment, the most comprehensive, multi-national human spaceflight study in history.

Data Sharing Agreements (DSAs) are formal arrangements between concurrent principal investigators (PIs) and/or flight surgeons to share select research and or medical data. Every DSA for a given crewmember is aggregated into a single Data Sharing Plan that must be reviewed and consented to by that crewmember before any data can be shared.

The broad physiological context obtained from SSM data supports efforts to determine the effectiveness of countermeasures. Data sharing with medical operations and current experiments reduces costs and optimizes requirements for crew time. For example, the ZeroT2 experiment is comparing the effectiveness of different exercise hardware on board the ISS for mitigating multi-system deconditioning. Because both SSM and ZeroT2 collect IMTP data, this measure is tactically shared to avoid redundancy and reduce total time requirements for a crewmember’s science complement.

Data analysis

SSM data are obtained on several physiological systems (microbiology, cardiovascular physiology, sleep, psychology, vestibular physiology, bone, biochemistry, nutrition) across studies performed during spaceflight. The database also includes associated information such as environmental conditions, mission characteristics, demographics, and countermeasures performed by the astronauts.

As of August 2025, the overall compliance with data collection is around 87%, with surveys and exercise logs showing the lowest completion rates. Missing data were primarily due to operational constraints, including scheduling conflicts, limited crew availability, equipment malfunctions, and the need to prioritize mission-critical activities. In some instances, incomplete data resulted from medical exemptions or technical problems during data transmission or storage.

This extensive, multimodal dataset offers a unique opportunity to examine how various human systems respond and adapt to spaceflight. With repeated measures taken at six timepoints—two preflight, two during a six-month mission, and two postflight—the data support robust longitudinal analyses. Methods such as linear mixed-effects models, growth curve modeling, and time series analysis can be used to track individual changes over time and evaluate the dynamics of recovery after spaceflight.

As mentioned earlier, a primary goal of SSM is to gather data for use by current and future researchers; therefore, there are no specific hypotheses or statistical analyses associated with the project. To date, data analysis has focused on the effects of intervention (spaceflight, bed rest, isolation, and confinement) on individual systems (cognition, cardio-vascular, sensorimotor, biochemistry). The results of this analysis have been published in peer-reviewed journals16,19,24,34,43,44,45,46. NASA standard measures data reveal that spaceflight leads to consistent physiological changes—including disrupted sleep, cardio-vascular and musculoskeletal adaptations, bone and vision changes, and altered immune and microbiome profiles—despite countermeasures.

The breadth of SSM variables allows for integrated, multivariate approaches. Techniques such as principal component analysis, structural equation modeling, and machine learning can help uncover relationships across systems and identify key predictors of resilience or vulnerability. The dataset also supports in-depth analysis of specific domains, such as the effects of microgravity on muscle strength, cardiovascular function, spatial disorientation, and sleep quality. Biological data (e.g., blood, urine, immune, and microbiome profiles) can be linked to behavioral and cognitive outcomes to explore complex interactions. Additionally, subgroup analyses based on sex, age, or baseline health status can help identify differences in spaceflight adaptation among individuals47. Immune function and viral shedding data offer the potential for survival and event-based analyses, whereas the relatively continuous measurement of motion amplitudes allows for fine-grained modeling of locomotor and vestibular performance. Altogether, this dataset provides a rich foundation for both hypothesis-driven and exploratory research into the physiological and psychological effects of long-duration spaceflight.

Similar standard measures are collected in analogs of spaceflight, such as during bed rest24,48,49,50,51,52,53,54,55,56,57,58,59,60, in isolated and confined environments61, in partial gravity during parabolic flight62, in simulated Martian gravity63, and in clinical settings64. Comparing data collected in these different environments can: (a) complement the spaceflight data with measures performed on a larger number of subjects and in a more controlled environment; (b) find possible redundant measures or synergies between the changes in responses from various physiological systems; and (c) determine outliers that might indicate the need to examine a related operational or environmental condition. The results of this data analysis will inform HRP about the mission impact on human health and performance capacity, and the effectiveness of countermeasures.

Limitations

The collection of SSM data is subject to several important limitations. One major constraint is the small number of astronauts flying on missions each year, which limits the size of the dataset and makes it difficult to draw broad statistical conclusions. Operational demands on board the ISS further restrict data collection; astronauts have limited time for research activities due to their packed schedules, and available onboard resources—such as equipment, storage, and power—must be carefully managed across multiple priorities. Ethical and privacy considerations also play a significant role, as all human research must comply with IRB requirements, which limit the types of data that can be collected, the methods used, and how the data can be shared or reused. Technological challenges in space, including the effects of microgravity on sample handling and device functionality, and time constraints can complicate or limit certain measurements. In addition, astronauts vary in how consistently they follow countermeasures such as exercise routines or dietary protocols, introducing variability in the data. Finally, longitudinal data collection—before, during, and after flight—can be inconsistent due to scheduling conflicts, medical complications, changing mission timelines, or other compliance issues, sometimes resulting in incomplete datasets.

Perspectives

With the ever-evolving landscape of human spaceflight and a rapidly growing biomedical evidence base (Table 4), space research studies must be agile enough to adapt to shifting programmatic priorities and evolving operational constraints.

Several modifications in SSM’s test battery and collection schedule have occurred in response to shifting priorities and to incorporate measurements with stronger supporting evidence than their historical counterparts. The relatively recent emergence of an active commercial space industry also provides new and unique opportunities to conduct biomedical research with groups of astronauts from assorted occupational backgrounds and various health statuses65,66. SSM was originally designed for ISS operations and was recently tailored to the specific characteristics of very short-duration private astronaut missions. In-flight hardware and software, vehicle capabilities, crew training, crew testing availability, and operational support are all factors that must be accounted for in the SSM design when applied to private astronaut mission designs. As the ISS prepares for decommissioning, collaborations between space agencies and private space programs have never been more important67,68.

With the Artemis generation of spaceflight underway, the return of cis-lunar and lunar-surface operations requires the evolution of active studies and creation of new research paradigms to address these emerging problem sets69. NASA is currently developing a set of measures that will be collected during the various manned Artemis missions. The exact measures and their timeline are being considered in the context of an occupational surveillance model that will actively monitor current crew health parameters and inform crew health practices to enable future precision space health capabilities70. Although ISS-based research continues to inform missions to the Moon, future Artemis research is designed to prepare space programs for exploration-class missions to Mars and beyond. These planetary missions require a robust research infrastructure that can inform decisions, accurately characterize risks, and evaluate countermeasures71. The SSM model of a standardized, agile, and multi-disciplinary research adopted by both governmental and private space agencies could produce a diverse evidence base that safely progresses human spaceflight into a new era of multiplanetary exploration. Fig 5.

Schematic illustrating how various spaceflight platforms can generate a diverse evidence base to reduce health risks to astronauts and advance humanity towards multi-planetary exploration. The risk matrix is color coded to indicate the severity of each risk ranging from red risks which are more severe than yellow risks which are more severe than green risks. Figure created with BioRender.com. Image credit: ESA/Hubble & NASA, M. Messa.

Data availability

No datasets were generated or analyzed during the current study.

References

Childress, S. D., Williams, T. C. & Francisco, D. R. NASA Space Flight Human-System Standard: enabling human spaceflight missions by supporting astronaut health, safety, and performance. npj Microgravity 9, 31 (2023).

Antonsen, E. L. et al. Estimating medical risk in human spaceflight. npj Microgravity 8, 8 (2022).

Antonsen, E. L. et al. Causal diagramming for assessing human system risk in spaceflight. npj Microgravity 10, 32 (2024).

Antonsen, E. L. et al. Updates to the NASA human system risk management process for space exploration. npj Microgravity 9, 72 (2023).

Afshinnekoo, E. et al. Fundamental biological features of spaceflight: advancing the field to enable deep-space exploration. Cell 183, 1162–1184 (2020).

Shelhamer, M. et al. Selected discoveries from human research in space that are relevant to human health on Earth. npj Microgravity 6, 5 (2020).

Dansberry, B. E. et al. Reflections on 20 years of research on the International Space Station. IAC-21-B3.3.8. In 72nd International Astronautical Congress (IAC), Dubai, UAE, 21-25 October 2021 (2021).

Walle, M. et al. Tracking of spaceflight-induced bone remodeling reveals a limited time frame for recovery of resorption sites in humans. Sci. Adv. 10, eadq3632 (2024).

Chancellor, J. C., Scott, G. B. I. & Sutton, J. P. Space radiation: the number one risk to astronaut health beyond low earth orbit. Life 4, 491–510 (2014).

Lee, A. G. et al. Spaceflight associated neuro-ocular syndrome (SANS) and the neuro-ophthalmologic effects of microgravity: a review and an update. npj Microgravity 6, 7 (2020).

Johnson, J. A. Measuring thirty facets of the Five Factor Model with a 120-item public domain inventory: Development of the IPIP-NEO-120. J. Res. Personal. 51, 78–89 (2014).

Musson, D. M., Sandal, G. & Helmreich, R. L. Personality characteristics and trait clusters in final stage astronaut selection. Aviat. Space Environ. Med. 75, 342–349 (2004).

Basner, M. et al. Cognition test battery: Adjusting for practice and stimulus set effects for varying administration intervals in high performing individuals. J. Clin. Exp. Neuropsychol. 42, 516–529 (2020).

Moore, T. M. et al. Validation of the Cognition Test Battery for spaceflight in a sample of highly educated adults. Aerosp. Med. Hum. Perform. 88, 937–946 (2017).

Casario, K. et al. Acceptability of the Cognition Test Battery in astronaut and astronaut-surrogate populations. Acta Astronautica 190, 14–23 (2022).

Dev, S. I. et al. Cognitive performance in ISS astronauts on 6-month low Earth orbit missions. Front. Physiol. 15, 1451269 (2024).

Flynn-Evans, E. et al. Circadian misalignment affects sleep and medication use before and during spaceflight. npj Microgravity 2, 15019 (2016).

Piechowski, S. et al. Effects of total sleep deprivation on performance in a manual spacecraft docking task. npj Microgravity 10, 21 (2024).

Piltch, O., Flynn-Evans, E. E., Young, M. & Stickgold, R. Changes to human sleep architecture during long-duration spaceflight. J. Sleep. Res. 10, e14345 (2024).

Clément, G. in Fundamental of Space Medicine 3rd edn. (ed. Clément, G.) 277–320 (Springer, 2025).

Smith, S. M., Zwart, S. R., Block, G., Rice, B. L. & Davis-Street, J. E. The nutritional status of astronauts is altered after long-term space flight aboard the International Space Station. J. Nutr. 135, 437–443 (2005).

Smith, S. M., Heer, M. & Zwart, S. R. Nutrition and human space flight: Evidence from 4-6 month missions to the International Space Station. Curr. Dev. Nutr. 4, nzaa055_031 (2020).

Chaloulakou, S., Poulia, K. A. & Karayiannis, D. Physiological alterations in relation to space flight: the role of nutrition. Nutrients 14, 4896 (2022).

Zwart, S. R. et al. Optic disc edema during strict 6° head-down tilt bed rest is related to one-carbon metabolism pathway genetics and optic cup volume. Front. Ophthalmol. 3, 1279831 (2023).

Mann, V. et al. Effects of microgravity and other space stressors in immunosuppression and viral reactivation with potential nervous system involvement. Neurol. India 67, S198–S203 (2019).

Diak, D. M., Crucian, B. E., Nelman-Gonzalez, M. & Mehta, S. K. Saliva diagnostics in spaceflight virology studies - A review. Viruses 16, 1909 (2024).

Oliveira Neto, N. F. D. et al. The emergence of saliva as a diagnostic and prognostic tool for viral infections. Viruses 16, 1759 (2024).

Crucian, B. et al. Alterations in adaptive immunity persist during long-duration spaceflight. npj Microgravity 1, 15013 (2015).

Crucian, B. et al. Immune system dysregulation during spaceflight: Potential countermeasures for deep space exploration missions. Front. Immunol. 9, 1437 (2018).

Morrison, M. D. et al. Investigation of spaceflight induced changes to astronaut microbiomes. Front. Microbiol. 12, 659179 (2021).

Tesei, D., Jewczynko, A., Lynch, A. M. & Urbaniak, C. Understanding the complexities and changes of the astronaut microbiome for successful long-duration space missions. Life 12, 495 (2022).

Castro-Wallace, S. L. et al. Nanopore DNA sequencing and genome assembly on the International Space Station. Sci. Rep. 7, 18022 (2017).

Halpin, A. L., McDonald, L. C., & Elkins, C. A. Framing bacterial genomics for public health care. J. Clin. Microbiol. 59, https://doi.org/10.1128/jcm.00135-21 (2021).

Clément, G., Moudy, S., Macaulay, T. R., Bishop, M. & Wood, S. Mission-critical tasks for assessing risks from vestibular and sensorimotor adaptation during space exploration. Front. Physiol. 13, 1029161 (2022c).

Moore, S. T. et al. Long-duration spaceflight adversely affects post-landing operator proficiency. Sci. Rep. 9, 2677 (2019).

Macaulay, T. R. et al. Developing proprioceptive countermeasures to mitigate postural and locomotor control deficits after long-duration spaceflight. Front. Syst. Neurosci. 15, 658985 (2021).

Moudy, S. C., Peters, B. T., Clark, T. K., Schubert, M. C. & Wood, S. J. Development of a ground-based sensorimotor disorientation analog to replicate astronaut postflight experience. Front. Physiol. 15, 1369788 (2024).

Comfort, P. et al. Effects of spaceflight on musculoskeletal health: A systematic review and meta-analysis, considerations for interplanetary travel. Sports Med. 51, 2097–2114 (2021).

Chang, D. G. et al. Lumbar spine paraspinal muscle and intervertebral disc height changes in astronauts after long-duration spaceflight on the International Space Station. Spine 41, 1917–1924 (2016).

Sibonga, J. et al. Resistive exercise in astronauts on prolonged spaceflights provides partial protection against spaceflight-induced bone loss. Bone 128, 112037 (2019).

Scott, J. M. et al. Effects of exercise countermeasures on multisystem function in long duration spaceflight astronauts. npj Microgravity 9, 11 (2023).

Russell, J. Getting Started with IMPALA (O’Reilly Media, Inc., 2014).

Zwart, S. R., Aunon-Chancellor, S. M., Heer, M., Melin, M. M. & Smith, S. M. Albumin, oral contraceptives, and venous thromboembolism risk in astronauts. J. Appl. Physiol. 132, 1232–1239 (2022).

Lee, S. M. C. et al. (2025) Cardiovascular responses to standing with and without lower body compression garments after long-duration spaceflight. J. Appl. Physiol. 139, 70–80 (2025).

Lee, S. M. C. et al. Arterial structure and function in the years after long-duration spaceflight. J. Appl. Physiol. 138, 1474–1488 (2025).

Ramsburg, C. F. et al. Potential benefits and human systems integration of parastronauts with bilateral vestibulopathy for a space mission. Front. Neurol. 16, 1556553 (2025).

Platts, S. H. et al. Effects of sex and gender on adaptation to space: cardiovascular alterations. J. Women Health 23, 950–955 (2014).

Laurie, S. S. et al. Optic disc edema after 30 days of strict head-down tilt bed rest. Ophthalmology 126, 467–468 (2019).

Laurie, S. S. et al. Unchanged cerebrovascular CO2 reactivity and hypercapnic ventilatory response during strict head-down tilt bed rest in a mild hypercapnic environment. J. Physiol. 598, 2491–2505 (2020).

Laurie, S. S. et al. Optic disc edema and chorioretinal folds develop during strict 6 degrees head down tilt bed rest with or without artificial gravity. Physiol. Rep. 9, e14977 (2021).

Lee, J. K. et al. Head down tilt bed rest plus elevated CO2 as a spaceflight analog: Effects on cognitive and sensorimotor performance. Front. Hum. Neurosci. 13, 355 (2019).

Zwart, S. R. et al. Association of genetics and B vitamin status with the magnitude of optic disc edema during 30-day strict head-down tilt bed rest. JAMA Ophthalmol. 137, 1195–1200 (2019).

Clément, G. et al. International standard measures during the VaPER bed rest study. Acta Astronautica 190, 208–217 (2022a).

Clément, G. et al. International standard measures during the AGBRESA bed rest study. Acta Astronautica 200, 163–175 (2022b).

Clément, G. et al. The assessment of centrifugation as a countermeasure in long duration spaceflight analogue: The protocol and implementation of the AGBRESA study. Front. Physiol. 13, 976926 (2022d).

Clément, G., Moudy, S. C., Macaulay, T. R., Mulder, E. & Wood, S. J. Effects of intermittent seating upright, lower body negative pressure, and exercise on functional tasks performance after head-down tilt bed rest. Front. Physiol. 15, 1442239 (2024b).

McGrath, E. R. et al. Bone metabolism during strict head-down tilt bed test and CO2 exposure. Cur. Dev. Nutr. 6, 1190 (2021).

McGrath, E. R. et al. Bone metabolism during strict head-down tilt bed rest and exposure to elevated levels of ambient CO2. npj Microgravity 8, 57 (2022).

Roberts, D. R. et al. Altered cerebral perfusion in response to chronic mild hypercapnia and head-down tilt bed rest as an analog for spaceflight. Neuroradiology 63, 1271–1281 (2021).

Carter, K. et al. Daily use of veno-constrictive thigh cuffs during 30 days of strict 6° head-down tilt bedrest to reverse the headward fluid shift. Physiology 39, 406 (2024).

Stahn, A. C. & Kühn, S. Brains in space: the importance of understanding the impact of long-duration spaceflight on spatial cognition and its neural circuitry. Cog. Process. 22, 105–114 (2021).

Clément, G., Macaulay, T. R., Bollinger, A., Weiss, H. & Wood, S. J. Functional activities essential for space exploration performed in partial gravity during parabolic flight. npj Microgravity 10, 86 (2024a).

Rosenberg, M. J., Koslovsky, M., Noyes, M., Reschke, M. F. & Clément, G. Tandem walking in simulated Martian gravity and visual environment. Brain Sci. 12, 1268 (2022).

Clément, G. et al. Cognitive and balance functions of astronauts after spaceflight are comparable to those of individuals with bilateral vestibulopathy. Front. Neurol. 14, 1284029 (2023).

Blue, R. S., Jennings, R. T., Antunano, M. J. & Mathers, C. H. Commercial spaceflight: Progress and challenges in expanding human access to space. Reach 7–8, 6–13 (2017).

Griko, Y. V., Loftus, D. J., Stolc, V. & Peletskaya, E. Private spaceflight: A new landscape for dealing with medical risk. Life Sci. Space Res. 33, 41–47 (2022).

Stepanek, J., Blue, R. S. & Parazynski, S. Space medicine in the era of civilian spaceflight. N. Engl. J. Med. 380, 1053–1060 (2019).

Creech, S., Guidi, J., & Elburn, D. Artemis: an overview of NASA’s activities to return humans to the Moon. In 2022 IEEE Aerospace Conference (AERO), Big Sky, MT, USA, 1-7 https://doi.org/10.1109/AERO53065.2022.9843277 (2022).

Bizzarri, M., Gaudenzi, P. & Angeloni, A. The biomedical challenge associated with the Artemis space program. Acta Astronautica 212, 14–28 (2023).

Abercromby, A. et al. NASA’s top human system research and technology needs for Mars. Acta Astronautica 228, 931–939 (2024).

Siegel, B. et al. Development of a NASA roadmap for planetary protection to prepare for the first human missions to Mars. Life Sci. Space Res. 38, 1–7 (2023).

Acknowledgements

This work was funded by NASA’s Human Health and Performance Contract (HHPC) as part of the Standard Measures Cross-Cutting Project. The authors thank Suzanne Bell, Christian Castro, Brian Crucian, Sheena Dev, Steven Laurie, Stuart Lee, Brandon Macias, Eric Rivas, Scott Smith, Sarah Wallaceś, Scott Wood, Sara Zwart, and the personnel of the Human Health and Performance Laboratories at NASA’s Johnson Space Center for their help with data collection and data analysis. The authors also thank Kerry George for editing the manuscript.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

J.H. contributed to the writing and revisions of all sections of the manuscript, figures, and supplementary information. Figures created using BioRender.com. C.T., T.O., and G.C. contributed to the writing and revisions of the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Hardy, J.G., Theriot, C.A., Oswald, T. et al. Spaceflight Standard Measures is a multidisciplinary study that systematically monitors risks to astronaut health and performance. npj Microgravity 11, 78 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41526-025-00532-6

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41526-025-00532-6