Abstract

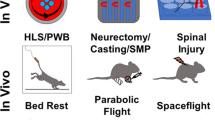

Bone density loss is a major concern for astronauts in space, largely due to altered mechanical stimuli in microgravity. These changes are thought to impact bone cells by directly affecting musculoskeletal cell physiology and disrupting mechanosensing and mechanotransduction pathways. This review focuses on the role of the primary cilium, a small, non-motile cellular structure, involved in these processes. Previously underestimated, the primary cilium is now known to act as a mechano- and chemo-sensor on the surface of most vertebrate cells, transmitting signals via multiple intracellular pathways. The primary cilium senses the extracellular fluid flow and its dynamic changes in physiological and pathological conditions, which may include exposure to microgravity, connecting its inactivation to bone density loss. This systematic review will compile and analyze current data on how weightlessness affects the mechanosensing functions of the primary cilium and its role in bone homeostasis disruption.

Similar content being viewed by others

Data availability

All data generated or analyzed during this study are included in this published article.

References

Tagliaferri, C., Wittrant, Y., Davicco, M.-J., Walrand, S. & Coxam, V. Muscle and bone, two interconnected tissues. Ageing Res. Rev. 21, 55–70 (2015).

Juhl, O. J. et al. Update on the effects of microgravity on the musculoskeletal system. NPJ Microgravity 7, 28 (2021).

Vico, L. et al. Effects of long-term microgravity exposure on cancellous and cortical weight-bearing bones of cosmonauts. Lancet Lond. Engl. 355, 1607–1611 (2000).

Man, J., Graham, T., Squires-Donelly, G. & Laslett, A. L. The effects of microgravity on bone structure and function. Npj Microgravity 8, 1–15 (2022).

Caillot-Augusseau, A. et al. Bone formation and resorption biological markers in cosmonauts during and after a 180-day space flight (Euromir 95). Clin. Chem. 44, 578–585 (1998).

Sugawara, Y. et al. The alteration of a mechanical property of bone cells during the process of changing from osteoblasts to osteocytes. Bone 43, 19–24 (2008).

Argentati, C. et al. Insight into mechanobiology: how stem cells feel mechanical forces and orchestrate biological functions. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 20, 5337 (2019).

Chen, Y., Ju, L., Rushdi, M., Ge, C. & Zhu, C. Receptor-mediated cell mechanosensing. Mol. Biol. Cell 28, 3134–3155 (2017).

Di, X. et al. Cellular mechanotransduction in health and diseases: from molecular mechanism to therapeutic targets. Signal Transduct. Target. Ther. 8, 282 (2023).

Shutova, M. S. & Boehncke, W.-H. Mechanotransduction in skin inflammation. Cells 11, 2026 (2022).

Stoufflet, J. et al. Primary cilium-dependent cAMP/PKA signaling at the centrosome regulates neuronal migration. Sci. Adv. 6, eaba3992 (2020).

Wheway, G., Nazlamova, L. & Hancock, J. T. Signaling through the primary cilium. Front. Cell Dev. Biol. 6, 8 (2018).

Jun, J. H., Lee, E. J., Park, M., Ko, J. Y. & Park, J. H. Reduced expression of TAZ inhibits primary cilium formation in renal glomeruli. Exp. Mol. Med. 54, 169–179 (2022).

Moorman, S. J. & Shorr, A. Z. The primary cilium as a gravitational force transducer and a regulator of transcriptional noise. Dev. Dyn. 237, 1955–1959 (2008).

Shi, W. et al. Primary cilia act as microgravity sensors by depolymerizing microtubules to inhibit osteoblastic differentiation and mineralization. Bone 136, 115346 (2020).

Martin, B. Aging and strength of bone as a structural material. Calcif. Tissue Int. 53, S34–S40 (1993).

Feng, X. Chemical and biochemical basis of cell–bone matrix interaction in health and disease. Curr. Chem. Biol. 3, 189–196 (2009).

Franz-Odendaal, T. A., Hall, B. K. & Witten, P. E. Buried alive: how osteoblasts become osteocytes. Dev. Dyn. 235, 176–190 (2006).

Palumbo, C. & Ferretti, M. The osteocyte: from “Prisoner” to “Orchestrator”. J. Funct. Morphol. Kinesiol. 6, 28 (2021).

Ma, X. et al. Functional role of vanilloid transient receptor potential 4-canonical transient receptor potential 1 complex in flow-induced Ca2+ influx. Arterioscler. Thromb. Vasc. Biol. 30, 851–858 (2010).

Robling, A. G., Castillo, A. B. & Turner, C. H. Biomechanical and molecular regulation of bone remodeling. Annu. Rev. Biomed. Eng. 8, 455–498 (2006).

Chen, N. X. et al. Ca(2+) regulates fluid shear-induced cytoskeletal reorganization and gene expression in osteoblasts. Am. J. Physiol. Cell Physiol. 278, C989–C997 (2000).

Roux, W. Beiträge zur Entwickelungsmechanik des Embryo. Anat. Hefte 2, 277–333 (1893).

Wolff, J. Concept of the law of bone remodelling. In The Law of Bone Remodelling (ed. Wolff, J.) 1–1 (Springer, 1986).

Frost, H. M. The mechanostat: a proposed pathogenic mechanism of osteoporoses and the bone mass effects of mechanical and nonmechanical agents. Bone Mineral 2, 73–85 (1987).

Burr, D. B. et al. In vivo measurement of human tibial strains during vigorous activity. Bone 18, 405–410 (1996).

Fritton, S. P., McLeod, K. J. & Rubin, C. T. Quantifying the strain history of bone: spatial uniformity and self-similarity of low-magnitude strains. J. Biomech. 33, 317–325 (2000).

Carter, D. R., Fyhrie, D. P. & Whalen, R. T. Trabecular bone density and loading history: regulation of connective tissue biology by mechanical energy. J. Biomech. 20, 785–794 (1987).

Liu, H.-Y. et al. Research on solute transport behaviors in the lacunar-canalicular system using numerical simulation in microgravity. Comput. Biol. Med. 119, 103700 (2020).

Stavnichuk, M., Mikolajewicz, N., Corlett, T., Morris, M. & Komarova, S. V. A systematic review and meta-analysis of bone loss in space travelers. Npj Microgravity 6, 1–9 (2020).

Dobner, S., Amadi, O. C. & Lee, R. T. Chapter 14 - Cardiovascular Mechanotransduction. in Muscle (eds. Hill, J. A. & Olson, E. N.) 173–186 (Academic Press, 2012).

Uray, I. P. & Uray, K. Mechanotransduction at the plasma membrane–cytoskeleton interface. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 22, 11566 (2021).

Freund, J. B., Goetz, J. G., Hill, K. L. & Vermot, J. Fluid flows and forces in development: functions, features and biophysical principles. Development 139, 1229–1245 (2012).

Qin, L., Liu, W., Cao, H. & Xiao, G. Molecular mechanosensors in osteocytes. Bone Res. 8, 1–24 (2020).

Zimmermann, K. W. Beiträge zur Kenntniss einiger Drüsen und Epithelien. Arch. Mikrosk. Anat. 52, 552–706 (1898).

Cameron, D. A. The ultrastructure of bone. In The Biology and Physiology of Bone 2nd edn (ed. Bourne, G. H.) Ch. 6, 191–236 (Academic Press, 1972).

Wheatley, D. N., Wang, A. M. & Strugnell, G. E. Expression of primary cilia in mammalian cells. Cell Biol. Int. 20, 73–81 (1996).

Boisvieux-Ulrich, E., Sandoz, D. & Allart, J.-P. Determination of ciliary polarity precedes differentiation in the epithelial cells of quail oviduct. Biol. Cell 72, 3–14 (1991).

Albrecht-Buehler, G. & Bushnell, A. The ultrastructure of primary cilia in quiescent 3T3 cells. Exp. Cell Res. 126, 427–437 (1980).

Downing, K. H. & Sui, H. Structural insights into microtubule doublet interactions in axonemes. Curr. Opin. Struct. Biol. 17, 253–259 (2007).

Saternos, H., Ley, S. & AbouAlaiwi, W. Primary cilia and calcium signaling interactions. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 21, 7109 (2020).

Kiesel, P. et al. The molecular structure of mammalian primary cilia revealed by cryo-electron tomography. Nat. Struct. Mol. Biol. 27, 1115–1124 (2020).

Flaherty, J., Feng, Z., Peng, Z., Young, Y.-N. & Resnick, A. Primary cilia have a length-dependent persistence length. Biomech. Model. Mechanobiol. 19, 445–460 (2020).

Sun, S.-Y., Zhang, L.-Y., Chen, X. & Feng, X.-Q. Biochemomechanical tensegrity model of cytoskeletons. J. Mech. Phys. Solids 175, 105288 (2023).

Garcia-Gonzalo, F. R. & Reiter, J. F. Open sesame: how transition fibers and the transition zone control ciliary composition. Cold Spring Harb. Perspect. Biol. 9, a028134 (2017).

Satir, P. & Gilula, N. B. The cell junction in a Lamellibranch Gill ciliated epithelium. J. Cell Biol. 47, 468–487 (1970).

Nechipurenko, I. V. The enigmatic role of lipids in cilia signaling. Front. Cell Dev. Biol. 8, 777 (2020).

Hoey, D. A., Tormey, S., Ramcharan, S., O’Brien, F. J. & Jacobs, C. R. Primary cilia-mediated mechanotransduction in human mesenchymal stem cells. Stem Cells 30, 2561–2570 (2012).

Jin, X. et al. Cilioplasm is a cellular compartment for calcium signaling in response to mechanical and chemical stimuli. Cell. Mol. Life Sci. 71, 2165–2178 (2014).

Molla-Herman, A. et al. The ciliary pocket: an endocytic membrane domain at the base of primary and motile cilia. J. Cell Sci. 123, 1785–1795 (2010).

Davenport, J. R. & Yoder, B. K. An incredible decade for the primary cilium: a look at a once-forgotten organelle. Am. J. Physiol. Renal Physiol. 289, F1159–F1169 (2005).

Gherman, A., Davis, E. E. & Katsanis, N. The ciliary proteome database: an integrated community resource for the genetic and functional dissection of cilia. Nat. Genet. 38, 961–962 (2006).

Li, D. & Wang, Y. Mechanobiology, tissue development, and tissue engineering. In Principles of Tissue Engineering 5th edn, Ch. 14 (eds. Lanza, R., Langer, R., Vacanti, J. P. & Atala, A.) 237–256 (Academic Press, 2020).

Subauste, M. C. et al. Vinculin modulation of paxillin–FAK interactions regulates ERK to control survival and motility. J. Cell Biol. 165, 371–381 (2004).

McNamara, L., Majeska, R., Weinbaum, S., Friedrich & Schaffler, M. Attachment of osteocyte cell processes to the bone matrix. Anat. Rec. Hoboken NJ 2007 292, 355–363 (2009).

Xu, Z., Zhang, D., He, X., Huang, Y. & Shao, H. Transport of calcium ions into mitochondria. Curr. Genom. 17, 215–219 (2016).

Lauritzen, I. et al. Cross-talk between the mechano-gated K2P channel TREK-1 and the actin cytoskeleton. EMBO Rep. 6, 642–648 (2005).

Maniotis, A. J., Chen, C. S. & Ingber, D. E. Demonstration of mechanical connections between integrins, cytoskeletal filaments, and nucleoplasm that stabilize nuclear structure. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 94, 849–854 (1997).

Maurer, M. & Lammerding, J. The driving force: nuclear mechanotransduction in cellular function, fate, and disease. Annu. Rev. Biomed. Eng. 21, 443–468 (2019).

Helmke, B. P., Thakker, D. B., Goldman, R. D. & Davies, P. F. Spatiotemporal analysis of flow-induced intermediate filament displacement in living endothelial cells. Biophys. J. 80, 184–194 (2001).

Ackbarow, T., Sen, D., Thaulow, C. & Buehler, M. J. Alpha-helical protein networks are self-protective and flaw-tolerant. PLoS ONE 4, e6015 (2009).

Dupont, S. et al. Role of YAP/TAZ in mechanotransduction. Nature 474, 179–183 (2011).

Habbig, S. et al. NPHP4, a cilia-associated protein, negatively regulates the Hippo pathway. J. Cell Biol. 193, 633–642 (2011).

Suarez Rodriguez, F., Sanlidag, S. & Sahlgren, C. Mechanical regulation of the Notch signaling pathway. Curr. Opin. Cell Biol. 85, 102244 (2023).

Stassen, O. M. J. A., Ristori, T. & Sahlgren, C. M. Notch in mechanotransduction—from molecular mechanosensitivity to tissue mechanostasis. J. Cell Sci. 133, jcs250738 (2020).

Stasiulewicz, M. et al. A conserved role for Notch signaling in priming the cellular response to Shh through ciliary localisation of the key Shh transducer Smo. Development 142, 2291–2303 (2015).

Ezratty, E. J., Pasolli, H. A. & Fuchs, E. A presenilin-2-ARF4 trafficking axis modulates notch signaling during epidermal differentiation. J. Cell Biol. 214, 89–101 (2016).

Huangfu, D. et al. Hedgehog signalling in the mouse requires intraflagellar transport proteins. Nature 426, 83–87 (2003).

Ezratty, E. J. et al. A role for the primary cilium in notch signaling and epidermal differentiation during skin development. Cell 145, 1129–1141 (2011).

Anvarian, Z., Mykytyn, K., Mukhopadhyay, S., Pedersen, L. B. & Christensen, S. T. Cellular signalling by primary cilia in development, organ function and disease. Nat. Rev. Nephrol. 15, 199–219 (2019).

Choi, J. U. A., Kijas, A. W., Lauko, J. & Rowan, A. E. The mechanosensory role of osteocytes and implications for bone health and disease states. Front. Cell Dev. Biol. 9, (2022).

Zhou, J. et al. Sinusoidal electromagnetic fields increase peak bone mass in rats by activating Wnt10b/β-catenin in primary cilia of osteoblasts. J. Bone Miner. Res. 34, 1336–1351 (2019).

Kim, S. et al. The polycystin complex mediates Wnt/Ca2+ signalling. Nat. Cell Biol. 18, 752–764 (2016).

Russwurm, M., Russwurm, C., Koesling, D. & Mergia, E. NO/cGMP: the past, the present, and the future. Methods Mol. Biol. 1020, 1–16 (2013).

He, W.-F. et al. The interdependent relationship between the nitric oxide signaling pathway and primary cilia in pulse electromagnetic field-stimulated osteoblastic differentiation. FASEB J. 36, e22376 (2022).

Shi, W. et al. The flavonol glycoside icariin promotes bone formation in growing rats by activating the cAMP signaling pathway in primary cilia of osteoblasts. J. Biol. Chem. 292, 20883–20896 (2017).

Sassone-Corsi, P. The cyclic AMP pathway. Cold Spring Harb. Perspect. Biol. 4, a011148 (2012).

Paolocci, E. & Zaccolo, M. Compartmentalised cAMP signalling in the primary cilium. Front. Physiol. 14, 1187134 (2023).

Kwon, R. Y., Temiyasathit, S., Tummala, P., Quah, C. C. & Jacobs, C. R. Primary cilium-dependent mechanosensing is mediated by adenylyl cyclase 6 and cyclic AMP in bone cells. FASEB J. 24, 2859–2868 (2010).

Tschaikner, P., Enzler, F., Torres-Quesada, O., Aanstad, P. & Stefan, E. Hedgehog and Gpr161: regulating cAMP signaling in the primary cilium. Cells 9, 118 (2020).

Yoder, B. K., Hou, X. & Guay-Woodford, L. M. The polycystic kidney disease proteins, polycystin-1, polycystin-2, polaris, and cystin, are co-localized in renal cilia. J. Am. Soc. Nephrol. 13, 2508 (2002).

Verbruggen, S. W., Sittichokechaiwut, A. & Reilly, G. C. Osteocytes and primary cilia. Curr. Osteoporos. Rep. 21, 719–730 (2023).

Temiyasathit, S. Osteocyte primary cilium and its role in bone mechanotransduction. Ann. N. Y. Acad. Sci. https://nyaspubs.onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1111/j.1749-6632.2009.05243.x (2010).

Xiao, Z. et al. Cilia-like structures and polycystin-1 in osteoblasts/osteocytes and associated abnormalities in skeletogenesis and Runx2 expression. J. Biol. Chem. 281, 30884–30895 (2006).

Gargalionis, A. N., Adamopoulos, C., Vottis, C. T., Papavassiliou, A. G. & Basdra, E. K. Runx2 and polycystins in bone mechanotransduction: challenges for therapeutic opportunities. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 25, 5291 (2024).

Xiao, Z. et al. Osteoblast-specific deletion of Pkd2 leads to low-turnover osteopenia and reduced bone marrow adiposity. PLoS ONE 9, e114198 (2014).

Xiao, Z., Zhang, S., Magenheimer, B. S., Luo, J. & Quarles, L. D. Polycystin-1 regulates skeletogenesis through stimulation of the osteoblast-specific transcription factor RUNX2-II. J. Biol. Chem. 283, 12624–12634 (2008).

Grimm, D. Microgravity and space medicine. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 22, 6697 (2021).

White, R. J. & Averner, M. Humans in space. Nature 409, 1115–1118 (2001).

Moosavi, D. et al. The effects of spaceflight microgravity on the musculoskeletal system of humans and animals, with an emphasis on exercise as a countermeasure: a systematic scoping review. Physiol. Res. 70, 119–151 (2021).

Nagaraja, M. P. & Risin, D. The current state of bone loss research: data from spaceflight and microgravity simulators. J. Cell. Biochem. 114, 1001–1008 (2013).

Belavy, D. L., Beller, G., Ritter, Z. & Felsenberg, D. Bone structure and density via HR-pQCT in 60d bed-rest, 2-years recovery with and without countermeasures. J. Musculoskelet. Neuronal Interact. 11, 215–226 (2011).

Gabel, L. et al. Pre-flight exercise and bone metabolism predict unloading-induced bone loss due to spaceflight. Br. J. Sports Med. 56, 196–203 (2022).

Sibonga, J. et al. Resistive exercise in astronauts on prolonged spaceflights provides partial protection against spaceflight-induced bone loss. Bone 128, 112037 (2019).

Fox, R. W., McDonald, A. T. & Mitchell, J. W. Fox and McDonald’s Introduction to Fluid Mechanics (John Wiley & Sons, 2020).

Smith, J. K. Osteoclasts and microgravity. Life 10, 207 (2020).

Shi, W. et al. Microgravity induces inhibition of osteoblastic differentiation and mineralization through abrogating primary cilia. Sci. Rep. 7, 1866 (2017).

Blaber, E. A. et al. Microgravity induces pelvic bone loss through osteoclastic activity, osteocytic osteolysis, and osteoblastic cell cycle inhibition by CDKN1a/p21. PLoS ONE 8, e61372 (2013).

De Leon-Oliva, D. et al. The RANK–RANKL–OPG system: a multifaceted regulator of homeostasis, immunity, and cancer. Medicina (Mexico) 59, 1752 (2023).

Vimalraj, S. Alkaline phosphatase: structure, expression and its function in bone mineralization. Gene 754, 144855 (2020).

Fan, C. et al. Activation of focal adhesion kinase restores simulated microgravity-induced inhibition of osteoblast differentiation via Wnt/Β-catenin pathway. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 23, 5593 (2022).

Zayzafoon, M., Gathings, W. E. & McDonald, J. M. Modeled microgravity inhibits osteogenic differentiation of human mesenchymal stem cells and increases adipogenesis. Endocrinology 145, 2421–2432 (2004).

Ducy, P., Zhang, R., Geoffroy, V., Ridall, A. L. & Karsenty, G. Osf2/Cbfa1: a transcriptional activator of osteoblast differentiation. Cell 89, 747–754 (1997).

Lecka-Czernik, B. et al. Inhibition of Osf2/Cbfa1 expression and terminal osteoblast differentiation by PPARgamma2. J. Cell. Biochem. 74, 357–371 (1999).

Chatziravdeli, V., Katsaras, G. N. & Lambrou, G. I. Gene expression in osteoblasts and osteoclasts under microgravity conditions: a systematic review. Curr. Genom. 20, 184–198 (2019).

Baecker, N. et al. Bone resorption is induced on the second day of bed rest: results of a controlled crossover trial. J. Appl. Physiol. 95, 977–982 (2003).

Gerbaix, M. et al. One-month spaceflight compromises the bone microstructure, tissue-level mechanical properties, osteocyte survival and lacunae volume in mature mice skeletons. Sci. Rep. 7, 2659 (2017).

Colucci, S. et al. Irisin prevents microgravity-induced impairment of osteoblast differentiation in vitro during the space flight CRS-14 mission. FASEB J. 34, 10096–10106 (2020).

Sambandam, Y. et al. Microgravity induction of TRAIL expression in preosteoclast cells enhances osteoclast differentiation. Sci. Rep. 6, 25143 (2016).

Brunetti, G. et al. TRAIL effect on osteoclast formation in physiological and pathological conditions. Front. Biosci. Elite Ed. 3, 1154–1161 (2011).

Yen, M.-L., Hsu, P.-N., Liao, H.-J., Lee, B.-H. & Tsai, H.-F. TRAF-6 dependent signaling pathway is essential for TNF-Related Apoptosis-Inducing Ligand (TRAIL) induces osteoclast differentiation. PLoS ONE 7, e38048 (2012).

Spatz, J. M. et al. The Wnt inhibitor sclerostin is up-regulated by mechanical unloading in osteocytes in vitro*. J. Biol. Chem. 290, 16744–16758 (2015).

Li, X. et al. Sclerostin binds to LRP5/6 and antagonizes canonical Wnt signaling*. J. Biol. Chem. 280, 19883–19887 (2005).

Sambandam, Y. et al. Microgravity control of autophagy modulates osteoclastogenesis. Bone 61, 125–131 (2014).

Lin, N.-Y., Stefanica, A. & Distler, J. H. W. Autophagy: a key pathway of TNF-induced inflammatory bone loss. Autophagy 9, 1253–1255 (2013).

Dai, R. et al. Cathepsin K: the action in and beyond bone. Front. Cell Dev. Biol. 8, 433 (2020).

Sutton, M. M., Duffy, M. P., Verbruggen, S. W. & Jacobs, C. R. Osteoclastogenesis requires primary cilia disassembly and can be inhibited by promoting primary cilia formation pharmacologically. Cells Tissues Organs 213, 235–244 (2024).

Nabavi, N., Khandani, A., Camirand, A. & Harrison, R. E. Effects of microgravity on osteoclast bone resorption and osteoblast cytoskeletal organization and adhesion. Bone 49, 965–974 (2011).

Wassermann, F. & Yaeger, J. A. Fine structure of the osteocyte capsule and of the wall of the lacunae in bone. Z. Zellforsch. Mikrosk. Anat. 67, 636–652 (1965).

Malone, A. M. D. et al. Primary cilia mediate mechanosensing in bone cells by a calcium-independent mechanism. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 104, 13325–13330 (2007).

Coughlin, T. R., Voisin, M., Schaffler, M. B., Niebur, G. L. & McNamara, L. M. Primary cilia exist in a small fraction of cells in trabecular bone and marrow. Calcif. Tissue Int. 96, 65–72 (2015).

Uzbekov, R. et al. Centrosome fine ultrastructure of the osteocyte mechanosensitive primary cilium. Microsc. Microanal. 18, 1430–1441 (2012).

McGlashan, S. R., Jensen, C. G. & Poole, C. A. Localization of extracellular matrix receptors on the chondrocyte primary cilium. J. Histochem. Cytochem. 54, 1005–1014 (2006).

Vaughan, T. J., Mullen, C. A., Verbruggen, S. W. & McNamara, L. M. Bone cell mechanosensation of fluid flow stimulation: a fluid–structure interaction model characterising the role integrin attachments and primary cilia. Biomech. Model. Mechanobiol. 14, 703–718 (2015).

Miao, L.-W. et al. Simulated microgravity-induced oxidative stress and loss of osteogenic potential of osteoblasts can be prevented by protection of primary cilia. J. Cell. Physiol. 238, 2692–2709 (2023).

Hughes-Fulford, M. Physiological effects of microgravity on osteoblast morphology and cell biology. In Advances in Space Biology and Medicine, Vol. 8 (ed. Cogoli, A.) 129–157 (Elsevier, 2002).

Gioia, M. et al. Simulated microgravity induces a cellular regression of the mature phenotype in human primary osteoblasts. Cell Death Discov. 4, 1–14 (2018).

Andreeva, E. et al. Real and simulated microgravity: focus on mammalian extracellular matrix. Life 12, 1343 (2022).

Ingber, D. E. Tensegrity: the architectural basis of cellular mechanotransduction. Annu. Rev. Physiol. 59, 575–599 (1997).

Heller, S. & O’Neil, R. G. Molecular mechanisms of TRPV4 gating. In TRP Ion Channel Function in Sensory Transduction and Cellular Signaling Cascades (eds Liedtke, W. B. & Heller, S.) (CRC Press/Taylor & Francis, 2007).

Berna-Erro, A. et al. Structural determinants of 5′,6′-epoxyeicosatrienoic acid binding to and activation of TRPV4 channel. Sci. Rep. 7, 10522 (2017).

Ding, D. et al. The microgravity induces the ciliary shortening and an increased ratio of anterograde/retrograde intraflagellar transport of osteocytes. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 530, 167–172 (2020).

Lutz, K., Trevino, T. & Adrian, C. Modeling effects of electromagnetic fields on bone density on humans in microgravity. In Proc. of AIAA ASCEND 2022–4291 (American Institute of Aeronautics and Astronautics, 2022).

Zhang, T., Zhao, Z. & Wang, T. Pulsed electromagnetic fields as a promising therapy for glucocorticoid-induced osteoporosis. Front. Bioeng. Biotechnol. 11, 1103515 (2023).

Prakash, D. & Behari, J. Synergistic role of hydroxyapatite nanoparticles and pulsed electromagnetic field therapy to prevent bone loss in rats following exposure to simulated microgravity. Int. J. Nanomed. 4, 133–144 (2009).

Zwart, S. R., Morgan, J. L. L. & Smith, S. M. Iron status and its relations with oxidative damage and bone loss during long-duration space flight on the International Space Station. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 98, 217–223 (2013).

Wang, N. et al. Salidroside alleviates simulated microgravity-induced bone loss by activating the Nrf2/HO-1 pathway. J. Orthop. Surg. 19, 531 (2024).

Xin, M. Attenuation of hind-limb suspension-induced bone loss by curcumin is associated with reduced oxidative stress and increased vitamin D receptor expression. Osteoporos. Int. https://link.springer.com/article/10.1007/s00198-015-3153-7 (2015).

Liang, X. et al. Angelicae dahuricae radix alleviates simulated microgravity induced bone loss by promoting osteoblast differentiation. Npj Microgravity 10, 1–14 (2024).

Page, M. J. et al. The PRISMA 2020 statement: an updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. BMJ 372, 71 (2021).

Ouzzani, M., Hammady, H., Fedorowicz, Z. & Elmagarmid, A. Rayyan—a web and mobile app for systematic reviews. Syst. Rev. 5, 210 (2016).

Minke, B. & Cook, B. TRP channel proteins and signal transduction. Physiol. Rev. 82, 429–472 (2002).

Sinkins, W. G., Estacion, M. & Schilling, W. P. Functional expression of TrpC1: a human homologue of the Drosophila Trp channel. Biochem. J. 331, 331–339 (1998).

Tsiokas, L. et al. Specific association of the gene product of PKD2 with the TRPC1 channel. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 96, 3934–3939 (1999).

Maroto, R. et al. TRPC1 forms the stretch-activated cation channel in vertebrate cells. Nat. Cell Biol. 7, 179–185 (2005).

Quick, K. et al. TRPC3 and TRPC6 are essential for normal mechanotransduction in subsets of sensory neurons and cochlear hair cells. Open Biol. 2, 120068 (2012).

Klein, S. et al. Modulation of transient receptor potential channels 3 and 6 regulates osteoclast function with impact on trabecular bone loss. Calcif. Tissue Int. 106, 655–664 (2020).

Shao, L. et al. Genetic reduction of cilium length by targeting intraflagellar transport 88 protein impedes kidney and liver cyst formation in mouse models of autosomal polycystic kidney disease. Kidney Int. 98, 1225–1241 (2020).

Masyuk, A. I. et al. Cholangiocyte cilia detect changes in luminal fluid flow and transmit them into intracellular Ca2+ and cAMP signaling. Gastroenterology 131, 911–920 (2006).

Lee, K. L. et al. The primary cilium functions as a mechanical and calcium signaling nexus. Cilia 4, 7 (2015).

Nomura, H. et al. Identification of PKDL, a novel polycystic kidney disease 2-like gene whose murine homologue is deleted in mice with kidney and retinal defects*. J. Biol. Chem. 273, 25967–25973 (1998).

DeCaen, P. G., Delling, M., Vien, T. N. & Clapham, D. E. Direct recording and molecular identification of the calcium channel of primary cilia. Nature 504, 315–318 (2013).

Fois, G. et al. An ultra fast detection method reveals strain-induced Ca2+ entry via TRPV2 in alveolar type II cells. Biomech. Model. Mechanobiol. 11, 959–971 (2012).

Köttgen, M. et al. TRPP2 and TRPV4 form a polymodal sensory channel complex. J. Cell Biol. 182, 437–447 (2008).

Corrigan, M. A. et al. TRPV4-mediates oscillatory fluid shear mechanotransduction in mesenchymal stem cells in part via the primary cilium. Sci. Rep. 8, 3824 (2018).

Acharya, T. K. et al. TRPV4 regulates osteoblast differentiation and mitochondrial function that are relevant for channelopathy. Front. Cell Dev. Biol. 11, 1066788 (2023).

Gayden, T. et al. Association of novel mutation in TRPV4 with familial nonsyndromic craniosynostosis with complete penetrance and variable expressivity. J. Neurosurg. Pediatr. 31, 584–592 (2023).

Cox, C. D. et al. Removal of the mechanoprotective influence of the cytoskeleton reveals PIEZO1 is gated by bilayer tension. Nat. Commun. 7, 10366 (2016).

Qin, L. et al. Roles of mechanosensitive channel Piezo1/2 proteins in skeleton and other tissues. Bone Res. 9, 44 (2021).

Lin, Y., Ren, J. & McGrath, C. Mechanosensitive Piezo1 and Piezo2 ion channels in craniofacial development and dentistry: recent advances and prospects. Front. Physiol. 13, 1039714 (2022).

Ashley, Z., Mugloo, S., McDonald, F. J. & Fronius, M. Epithelial Na+ channel differentially contributes to shear stress-mediated vascular responsiveness in carotid and mesenteric arteries from mice. Am. J. Physiol. Heart Circ. Physiol. 314, H1022–H1032 (2018).

Acknowledgements

This study was partially funded by Università Cattolica del Sacro Cuore “linea D.1 and linea D.3.1” to W.L. The authors acknowledge the Regenerative Medicine Research Center (CROME) of the Università Cattolica del Sacro Cuore.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Conceptualization: D.D.T. and W.L.; writing—original draft preparation: D.D.T., F.T., L.P.; writing review and editing: W.L., F.T., A.A., A.M., and L.D.P.; funding acquisition: A.M., W.L., and O.P. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Tosi, D.D., Tiberio, F., Di Pietro, L. et al. Effects of microgravity mechanotransduction in bone tissue and cells: systematic review on primary cilium-dependent mechanisms. npj Microgravity (2026). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41526-025-00556-y

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41526-025-00556-y