Abstract

Transferring single-crystalline (SC) membranes to flexible substrates has been increasingly studied, enabling emerging functionality and enhanced performance of various devices. A commonly used support-assisted transfer process inevitably leaves dirty residue on material surfaces, limiting the further development of surface-related applications. Here, we scale down the thickness of flexible SC SrRuO3 (SRO) membranes to 15 nm with a clean surface area of 2.5 × 2.5 mm2. This is accomplished by making the polyethylene terephthalate (PET) substrate surface hydrophilic via oxygen plasma treatment, thereby reducing the surface tension. The ultrathin, clean, wide, and flexible SC SRO membranes guarantee a high transmittance of up to 60%, a low resistivity of 10−4−10−3 Ω cm at room temperature, and band ferromagnetism below 150 K with a high magnetic moment of ~0.5 μB/Ru at 10 K. The SC-level properties of our SRO membranes imply their potential use in state-of-the-art platforms for next-generation electronics and energy devices.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Single-crystalline (SC) membranes show great promise due to their flexibility for use in wearable applications, superior device performance with respect to hypocrystalline membranes, and emerging properties that are unachievable with solid SC films. Nanometre-thick SC BaTiO3 membranes can be bent up to 180° while retaining their ferroelectric polarization1. Highly twistable SC devices of YBa2Cu3O7−x and Fe3O4 exhibit superconductivity and ferrimagnetism, respectively2,3. Ferroelectric tunnel junctions can be realized by placing ultrathin SC BaTiO3 membranes on silicon or polymer substrates without an additional buffer layer4,5,6. Extreme strain engineering, exceeding 8%, is capable of inducing a reversible metal-insulator transition in SC La0.7Ca0.3MnO3 membranes7. SC membranes have also attracted considerable attention due to the potential realization of quantum phenomena at the monolayer limit based on similar observations in two-dimensional van der Waals materials8.

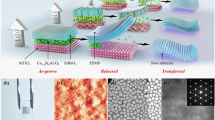

The recent introduction of convenient and safe transfer methods using a water-soluble sacrificial layer1,2,3,4,5,6,7,8,9 or remote epitaxy through graphene10,11 continues to fuel growing interest in SC membranes. However, the conventional way to transfer SC membranes is through the use of organic support materials for easy handling; this inevitably leaves a dirty residue on the membrane surface, further limiting the development of surface-related applications. Figure 1a displays the commonly used support-assisted transfer process with a selectively etchable sacrificial layer1,2,3,4,5,6,7,8,9, involving the following five steps: (1) depositing SC films on sacrificial layer-coated SC substrates → (2) coating the surface with an organic support material for convenient handling → (3) selectively etching the sacrificial layer → (4) transferring the floated SC films onto other substrates → (5) erasing the support by mechanical detachment, thermal decomposition, and acetone. Without the support, the SC membranes tend to crumble, roll, and/or tear (Supplementary Fig. 1). Thus, it is extremely challenging to transfer thin SC membranes while keeping a large, clean surface.

a Conventional support-assisted transfer process includes coating an organic support material for easy handling; however, it is a five-step process and tends to leave a dirty residue on the surface. Without the support material, the SC SRO membranes easily crumple, roll, and tear, so it is difficult to transfer membranes that are thinner than those with a sub-hundred-nanometre thickness. b Using the proposed support-free transfer process, we transferred SC SRO membranes as thin as 15 nm onto an oxygen-plasma-treated PET substrate. Given that organic supports are not required for our method, the entire process involves only three steps. The photographs show the c selective etching of the sacrificial layer in deionized water, d floated SC SRO membranes in deionized water, and e transferred SC SRO membrane onto the oxygen-plasma-treated PET.

Although the early works of van der Waals materials suffered from similar contamination issues, the use of a hexagonal BN stamp has provided the means to transfer these materials while retaining a clean surface12. The clean surface of van der Waals materials enables the fabrication of twisted bilayers, which have exhibited emerging quantum phenomena, e.g., superconductivity and ferromagnetism13,14. This achievement serves as a potential guide for SC membrane development and transfer. The ability to produce ultrathin SC membranes with large, clean surfaces will enable the development of emerging surface-related applications, including bilayer-stacked quantum devices and catalysts. Moreover, thin SC membranes have the advantages of flexibility, as they are less brittle than thicker membranes with respect to mechanical stress7,15, and transparency, given that the transmittance increases with a decrease in thickness16.

Here, we successfully scale down the thickness of flexible SC SrRuO3 (SRO) membranes to 15 nm with a clean surface area of 2.5 × 2.5 mm2 by converting the hydrophobic surface of polyethylene terephthalate (PET) substrates to a hydrophilic state via oxygen plasma treatment. Using stress relaxation to our advantage, we successfully transfer the as-fabricated ultrathin, clean, wide, and flexible SC membranes. Our flexible SC membranes display high optical transmittance of up to ~60%. Because a single crystal is preserved even in the flexible membranes, as indicated by X-ray diffraction (XRD) and scanning transmission electron microscopy (STEM) measurements, the electrical and magnetic properties are comparable to those of solid SC SRO films grown directly on SrTiO3 (STO) substrates.

Results and discussion

Transfer of ultrathin, clean, wide, and flexible SC SRO membrane

Earlier, we discussed a five-step transfer process for the membranes. However, in our proposed approach, the use of an organic support material was not necessary, thus reducing the number of steps to the following three (Fig. 1b): (1) depositing SC films on sacrificial layer-coated SC substrates → (2) selectively etching the sacrificial layer → (3) transferring the floated SC films onto other substrates. Using our support-free process, we successfully transferred ultrathin and wide SC SRO membranes with a clean surface onto flexible PET substrates. Figure 1c−e show the photographs taken by a camera at each step. Using pulsed laser epitaxy, we coated (001)-oriented STO substrates with a water-soluble sacrificial layer of Sr3Al2O6 (SAO). The samples had a large surface area of 2.5 × 2.5 mm2. Subsequently, we deposited SC SRO films onto the SAO-coated STO substrate. The growth conditions were similar to those described in the previous reports1,2,3,4,5,6,7,8,9, and further details are provided in the Methods section. The cross-sectional STEM images indicated thicknesses of 250 nm and 15–30 nm for the SAO and SRO layers, respectively (Supplementary Fig. 2). The samples were immersed in deionized water to selectively dissolve the SAO layer (Fig. 1c), which dissolved within a few minutes; however, the sample was kept in the water for 12 h to completely release the SRO membranes from the STO substrate (Fig. 1d). The floating membranes were scooped from the water using oxygen-plasma-treated PET substrates (Fig. 1e). Water droplets were removed from the surface for a period of 30 min. Notably, we could stably reproduce the SRO membranes (Supplementary Fig. 3a–c). The resulting material properties of the transferred SC SRO membrane were then characterized. Note that for convenience, we will sometimes use the simpler form \({{{\mathrm{SRO}}}}_{{{{\mathrm{substrate}}}}}^{{{{\mathrm{thickness}}}}}\).

In addition to being an extremely simple process, our approach has several advantages. We succeeded in transferring SC SRO membranes as thin as 15 nm onto flexible PET with a clean surface; notably, the membrane thickness was much thinner than that reported in an earlier report (subhundred nanometre thickness)17. Such ultrathin membranes on flexible substrates guarantee flexibility (Fig. 2a), which is different from most thin membranes transferred to solid substrates2,4,8,9. Because we did not use an organic support, which would normally coat the film surface, we were able to retain a clean membrane surface. Optical microscopy revealed that our flexible SC SRO membranes had a clean 2.5 × 2.5 mm2 surface area (Fig. 2b). The microscale images obtained by scanning electron microscopy hardly showed cracks on the surface (Figure S3d). Atomic force microscopy revealed a uniform phase over randomly selected 5 × 5 μm2 areas of the SC SRO membrane (Fig. 2c), while the treated PET surface showed nonuniform phases (Fig. 2d); i.e., there were few residues on the surface of the SC SRO membrane. The root-mean-square roughness of the SC SRO membranes was ~2.9 nm (Fig. 2e), similar to the ~2.4 nm roughness of the treated PET substrate (Fig. 2f). Thus, the SC SRO membrane surface was very flat. Additionally, our transfer process was very safe, only using deionized water instead of dangerous acids18,19. It is also noteworthy that the expensive STO substrates could be reused, as reported elsewhere17.

a Photograph showing the background ‘DGIST’ logo to demonstrate the flexibility of our \({{{\mathrm{SRO}}}}_{{{{\mathrm{PET}}}}}^{15{{{\mathrm{nm}}}}}\) membrane, with the form \({{{\mathrm{SRO}}}}_{{{{\mathrm{substrate}}}}}^{{{{\mathrm{thickness}}}}}\) used for convenience. b Optical microscopy image of 2.5 × 2.5-mm2-wide \({{{\mathrm{SRO}}}}_{{{{\mathrm{PET}}}}}^{15{{{\mathrm{nm}}}}}\) showing a clean surface. An atomic force microscopy image reveals a more uniform phase on the randomly selected 5 × 5 μm2 surface of the c SC SRO membrane than that of the d treated PET. The root-mean-square roughness of the e SC SRO membranes was only ~2.9 nm, comparable to the ~2.4 nm of f PET.

Hydrophilic PET surface for strain relaxation of SRO membrane

The most important reason for the successful transfer of the ultrathin SC membranes was the conversion of the hydrophobic surface of the flexible PET substrate to its hydrophilic form using oxygen plasma treatment. Polymer substrates, including untreated PET, have a hydrophobic surface due to C−C bonding20,21. Thus, there is a large amount of surface tension between the hydrophobic surface of PET and deionized water, which results in the curved surface of water droplets having a very large contact angle (ϕ) and a very small radius (R) (Fig. 3a). According to the Stoney formula15, the stress applied to the membranes floating on the droplet of water was inversely proportional to the radius of curvature and increased further with a decrease in the membrane thickness (d). As evidenced by X-ray photoelectron spectroscopy20,21, oxygen plasma mainly attacked CH2 and phenyl rings, forming C−O groups, i.e., converting the hydrophobic PET surface (Fig. 3b) to a hydrophilic state (Fig. 3c). The contact angle decreased drastically from ~73.4° on the untreated PET substrate to ~19.4° on the oxygen-plasma-treated substrate. Accordingly, the radius of curvature increased from ~3.1 to ~13.9 mm, significantly reducing the stress on the oxygen-plasma-treated PET substrate. Therefore, we were able to transfer much thinner membranes (15 nm in this work), with a clean and wide surface and without mechanical fracturing, crumpling, rolling, or tearing.

a Membrane floating on the water droplet is under stress; the associated stress is inversely proportional to the radius of curvature (R) and the membrane thickness (d). The contact angles (ϕ) between the water droplet and PET substrate decreased b from ~73.4° for untreated PET c to ~19.4° for oxygen-plasma-treated PET. Accordingly, the radius of curvature increased from 3.1 to 13.9 nm. Thus, we can transfer much thinner membranes with a clean surface and a wide area on oxygen-plasma-treated PET substrates.

Single crystallinity of ultrathin SRO flexible membranes

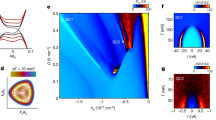

We found that the SRO flexible membranes preserved the SC structural properties, to some extent, after our transfer process. The red line in Fig. 4a shows the XRD θ−2θ scan of \({{{\mathrm{SRO}}}}_{{{{\mathrm{PET}}}}}^{30{{{\mathrm{nm}}}}}\). The XRD peaks of \({{{\mathrm{SRO}}}}_{{{{\mathrm{PET}}}}}^{15{{{\mathrm{nm}}}}}\) were similar but very weak (Supplementary Fig. 4). A distinguishable XRD peak was observed at 2θ = 46.1°, corresponding to the (002)SRO diffraction peak, which was absent for the bare PET substrate (black line). To gain further insights, we compared the XRD θ−2θ scans of \({{{\mathrm{SRO}}}}_{{{{\mathrm{SAO}}}}/{{{\mathrm{STO}}}}}^{30{{{\mathrm{nm}}}}}\) (green line) and \({{{\mathrm{SRO}}}}_{{{{\mathrm{STO}}}}}^{30{{{\mathrm{nm}}}}}\) (grey line). As guided by the dashed line, the (002)SRO peaks of \({{{\mathrm{SRO}}}}_{{{{\mathrm{PET}}}}}^{30{{{\mathrm{nm}}}}}\) and \({{{\mathrm{SRO}}}}_{{{{\mathrm{SAO}}}}/{{{\mathrm{STO}}}}}^{30{{{\mathrm{nm}}}}}\) were positioned at a higher 2θ angle than those (= 45.9°) of \({{{\mathrm{SRO}}}}_{{{{\mathrm{STO}}}}}^{30{{{\mathrm{nm}}}}}\). Such a negligible strain was acceptable, given that PET is amorphous. The lattice parameters of SRO (a = b = c = 3.95 Å) were similar to those of SAO (3.96 Å), whereas the SRO films on STO substrates exhibited a compressive in-plane strain due to smaller lattice parameter (3.905 Å) of STO. The XRD ω scans of (002)SRO showed a single peak for \({{{\mathrm{SRO}}}}_{{{{\mathrm{PET}}}}}^{30{{{\mathrm{nm}}}}}\), \({{{\mathrm{SRO}}}}_{{{{\mathrm{SAO}}}}/{{{\mathrm{STO}}}}}^{30{{{\mathrm{nm}}}}}\), and \({{{\mathrm{SRO}}}}_{{{{\mathrm{STO}}}}}^{30{{{\mathrm{nm}}}}}\) (Lorentzian fits are in Fig. 4b and the experimental data are in Supplementary Fig. 5), implying the dominant existence of a single domain for all samples. As reported for SC Sr2IrO4 membranes22, the full widths at half maximum of the ω scans increased from 0.14° for \({{{\mathrm{SRO}}}}_{{{{\mathrm{STO}}}}}^{30{{{\mathrm{nm}}}}}\) and 0.42° for \({{{\mathrm{SRO}}}}_{{{{\mathrm{SAO}}}}/{{{\mathrm{STO}}}}}^{30{{{\mathrm{nm}}}}}\) to 2.33° for \({{{\mathrm{SRO}}}}_{{{{\mathrm{PET}}}}}^{30{{{\mathrm{nm}}}}}\), indicating the slight formation of a mosaic spread in the SC SRO/SAO/STO films and SC SRO membranes. This could be the origin of electron scattering with regard to the transport properties of ultrathin SC SRO membranes.

a X-ray diffraction θ−2θ scans show the (002) diffraction peaks of SRO near 2θ = 45.9−46.1°, as guided by a dashed line, for \({{{\mathrm{SRO}}}}_{{{{\mathrm{PET}}}}}^{30{{{\mathrm{nm}}}}}\), \({{{\mathrm{SRO}}}}_{{{{\mathrm{SAO}}}}/{{{\mathrm{STO}}}}}^{30{{{\mathrm{nm}}}}}\), and \({{{\mathrm{SRO}}}}_{{{{\mathrm{STO}}}}}^{30{{{\mathrm{nm}}}}}\); SAO and STO indicate a Sr3Al2O6 sacrificial layer and the SrTiO3 substrate, respectively. b Full widths at half maximum of the normalized ω scan increased from 0.14° \(({{{\mathrm{SRO}}}}_{{{{\mathrm{STO}}}}}^{30{{{\mathrm{nm}}}}})\) to 2.33° \(({{{\mathrm{SRO}}}}_{{{{\mathrm{PET}}}}}^{30{{{\mathrm{nm}}}}})\). For convenience, we used the normalized intensity \(( = \frac{I}{{I_{{{{\mathrm{max}}}}}}})\) and Δω (= ω − ωc), where Imax is the maximum intensity at ωc. c Scanning transmission electron microscopy images show few mechanical fractures over a wide area of \({{{\mathrm{SRO}}}}_{{{{\mathrm{PET}}}}}^{30{{{\mathrm{nm}}}}}\); energy-dispersive X-ray spectroscopy measurements indicate a uniform distribution of Sr and Ru.

SRO flexible membranes on PET have few mechanical fractures over a wide area. The cross-sectional STEM image in Fig. 4c shows that \({{{\mathrm{SRO}}}}_{{{{\mathrm{PET}}}}}^{30{{{\mathrm{nm}}}}}\) has a uniform thickness of 30 nm with a lateral length of ~1 μm. The energy-dispersive X-ray spectroscopy results indicated uniform distributions of Sr and Ru over the entire area. Both images were similar to those of \({{{\mathrm{SRO}}}}_{{{{\mathrm{SAO}}}}/{{{\mathrm{STO}}}}}^{30{{{\mathrm{nm}}}}}\) (Supplementary Fig. 2), indicating that strain-relaxed transfer onto the hydrophilic surface of flexible PET preserved the inherent single crystallinity of the SRO films.

High transmittance and metallicity of SRO membrane

SRO is a versatile material that has been increasingly studied due to its high conductivity23, ferromagnetism24,25, and electrocatalytic activity26. Recently, SRO has gained renewed interest after observations of magnetic skyrmions27 and magnetic monopoles in momentum space28. Investigations of SRO have been mainly carried out in its film form. We investigated the optical, electrical, and magnetic properties of flexible SC SRO membranes as well as their potential application.

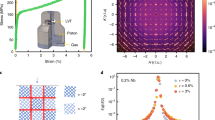

Thickness scaling and a clean surface enabled an increase in the optical transmittance of flexible SC SRO membranes. According to Beer’s law, a larger amount of light can propagate through a thinner material16. The clean surface of our SC SRO membranes reduced light scattering, as there were few particles on the surface. Figure 5a shows the enhanced transmittance, which is up to ~60% for wavelengths above ~500 nm for \({{{\mathrm{SRO}}}}_{{{{\mathrm{PET}}}}}^{15{{{\mathrm{nm}}}}}\); additionally, the ‘DGIST’ letters can clearly be seen through the SC SRO membranes in the figure. Thus, the improvement in the transmittance was significant, with \({{{\mathrm{SRO}}}}_{{{{\mathrm{PET}}}}}^{30{{{\mathrm{nm}}}}}\) realizing ~40% transmittance compared with the complete opaqueness of 100−300-nm-thick SRO membranes17. The suppressed transmission of wavelengths below 500 nm is attributed to the interband transition energy of ~3.3 eV between the occupied O 2p level and the unoccupied Ru 4d eg level26. We commonly observed a sudden dip near the wavelength of 1650 nm for all samples, which originated from the PET substrate.

a In the wavelength range of 200−2000 nm, the transmittance approached 60% for \({{{\mathrm{SRO}}}}_{{{{\mathrm{PET}}}}}^{15{{{\mathrm{nm}}}}}\). The dip near 1650 nm comes from the PET substrate. UV and IR are short for ultraviolet and infrared, respectively. b \({{{\mathrm{SRO}}}}_{{{{\mathrm{PET}}}}}^{30{{{\mathrm{nm}}}}}\) shows a similar resistivity–temperature curve as that of \({{{\mathrm{SRO}}}}_{{{{\mathrm{STO}}}}}^{30{{{\mathrm{nm}}}}}\). Although the resistivity of \({{{\mathrm{SRO}}}}_{{{{\mathrm{PET}}}}}^{15{{{\mathrm{nm}}}}}\) is higher than that of \({{{\mathrm{SRO}}}}_{{{{\mathrm{STO}}}}}^{15{{{\mathrm{nm}}}}}\), it is very close to 10−3 Ω cm near room temperature. The high resistivity of \({{{\mathrm{SRO}}}}_{{{{\mathrm{SAO}}}}/{{{\mathrm{STO}}}}}^{15{{{\mathrm{nm}}}}}\) provides some insight into the high resistivity of \({{{\mathrm{SRO}}}}_{{{{\mathrm{PET}}}}}^{15{{{\mathrm{nm}}}}}\) that readily occurs during the growth of the SRO film on an SAO-coated STO substrate. The arrows in the figure and the inset indicate the anomaly, which is attributed to the band ferromagnetism of SRO. The flexible SC SRO membranes and solid SC SRO films show similar c magnetic moment–temperature and d magnetic moment–magnetic field curves.

The metallicity of the flexible ultrathin SC SRO membranes was comparable to that of the solid SC SRO films. Figure 5b shows that the resistivity of \({{{\mathrm{SRO}}}}_{{{{\mathrm{PET}}}}}^{30{{{\mathrm{nm}}}}}\) (red solid line) increased with increasing temperature over a wide temperature range of 10−400 K, an indication of metallic behaviour; moreover, the resistivity was similar to those of our \({{{\mathrm{SRO}}}}_{{{{\mathrm{STO}}}}}^{30{{{\mathrm{nm}}}}}\) (red dotted line) and reported solid SC SRO films23,24,25. The persistent metallicity was consistent with the preserved single crystallinity during our transfer process. Although the resistivity of \({{{\mathrm{SRO}}}}_{{{{\mathrm{PET}}}}}^{15{{{\mathrm{nm}}}}}\) (blue solid line) decreased with increasing temperature, it was very close to 10−3 Ω cm (the Mott–Ioffe–Regel limit)29 at room temperature, indicating that \({{{\mathrm{SRO}}}}_{{{{\mathrm{PET}}}}}^{15{{{\mathrm{nm}}}}}\) was on the verge of attaining a metallic nature. It should be noted that \({{{\mathrm{SRO}}}}_{{{{\mathrm{SAO}}}}/{{{\mathrm{STO}}}}}^{15{{{\mathrm{nm}}}}}\) (green solid line) also had a higher resistivity than \({{{\mathrm{SRO}}}}_{{{{\mathrm{STO}}}}}^{15{{{\mathrm{nm}}}}}\) (red dotted line). Therefore, the high resistivity of \({{{\mathrm{SRO}}}}_{{{{\mathrm{PET}}}}}^{15{{{\mathrm{nm}}}}}\) was attributed to the slight formation of a mosaic spread in the SC SRO/SAO/STO films and SC SRO membranes, as indicated in the XRD data (Fig. 4b). The fundamental thickness of metallic resistivity was ~15 nm for the flexible SC SRO membrane, which was considerably thicker than the ~1.5-nm thickness of solid epitaxial SC SRO films24,25.

It is widely accepted that SRO has ferromagnetism due to a spontaneously spin-split band30. We observed band ferromagnetism in the flexible ultrathin SC SRO membranes, as well as in the solid SC SRO films. The saturation magnetic moment at 100 Oe increased below a Curie temperature of 150 K with the ultrathin SC SRO membranes, as well as with the SC SRO films (Fig. 5c). We also examined the Curie temperature at ~150 K by the anomaly in the resistivity–temperature curves (arrows in Fig. 5b and the inset)24. The ultrathin SC SRO membranes exhibited a large-area hysteresis loop, given the magnetic field dependence of the magnetic moment at 10 K (Fig. 5d). The saturation magnetic moment of 0.5−0.7 μB/Ru and the coercive field of 0.5−1.5 T were similar to those of the SC SRO films, indicating the existence of ferromagnetic ordering below 150 K, even with \({{{\mathrm{SRO}}}}_{{{{\mathrm{PET}}}}}^{15{{{\mathrm{nm}}}}}\).

In conclusion, we developed a transfer process to scale down the thickness of clean and large SC membranes on a flexible PET substrate. We successfully thinned the SC SRO membranes to 15 nm with a clean surface area of 2.5 × 2.5 mm2 when we reduced the surface tension between the water droplets and PET surface. This was accomplished by converting the hydrophobic surface of the PET substrate to one that was hydrophilic via oxygen plasma treatment. Due to the cleaner surface and thinner thickness than those reported previously in the literature (sub-hundred-nanometre-thick membranes), our flexible SC SRO membranes were optically transparent with an enhanced transmittance of up to ~60% while retaining their metallicity (<10−3 Ω cm at room temperature) and magnetization (0.5−0.7 μB/Ru at 10 K). Notably, these values were comparable to those of the solid SC SRO films grown directly on STO. Therefore, the thin, clean, wide, and flexible SC SRO membranes, are expected to be especially useful for emerging surface-related applications, including those involving flexible optoelectronic devices, bilayer-stacked devices, and catalysts.

Methods

Synthesis of single-crystalline (SC) SrRuO3 (SRO) flexible membranes

We used pulsed laser epitaxy to deposit an SRO epitaxial film and a Sr3Al2O6 (SAO) sacrificial layer onto a (001)-oriented SrTiO3 (STO) substrate. SAO and SRO targets (Toshima Manufacturing Co., Ltd.) were ablated with a KrF excimer laser (IPEX-760; LightMachinery, Inc.) with a wavelength of 248 nm, a laser intensity of 1 J cm−2, and a repetition rate of 10 Hz. The growth conditions for the SAO layer included a substrate temperature of 730 °C and an oxygen partial pressure of 150 mTorr. The SRO films had a substrate temperature of 700 °C and an oxygen partial pressure of 100 mTorr. The SRO/SAO/STO samples were immersed in deionized water for 12 h to sufficiently dissolve the SAO sacrificial layer. We scooped the floating SRO film and transferred the film membrane to the oxygen-plasma-treated polyethylene terephthalate (PET) substrate. The samples were then dried at 70 °C on a hot plate for 30 min.

Oxygen plasma treatment of PET

We converted the hydrophobic surface of PET to a hydrophilic state by oxygen plasma at a radio frequency of 13.56 MHz. We found that the optimal conditions for the hydrophilic and flat surfaces of PET were a power of 50 W for 30 s (Supplementary Fig. 6) since the surface of the treated PET did not become rougher while having a smaller contact angle and a larger radius of curvature than the untreated PET. We used a contact angle analyser (Phoenix-Mini; SEO) to measure the contact angles of water droplets on PET. The contact angles did not change over a 24-hour period (Supplementary Fig. 7), which indicated that the hydrophilic surface was persistent.

Characterization of the flexible SC SRO membranes

Atomic force microscopy (XE7; Park Systems) was used to check the roughness and surface contamination of the samples. In tapping mode, we scanned the randomly selected 5 × 5 μm2 surface of the samples using a scan rate of 0.5 Hz. We investigated the structural properties using a four-circle high-resolution X-ray diffractometer (Empyrean; PANalytical) with a wavelength of 1.54 Å radiated from a copper source. A ¼-inch divergence slit was used for θ−2θ and ω scans. Cross-sectional images were obtained with a transmission electron microscope (HF-3300; Hitachi) that was operated at 300 kV and had a lattice resolution of at least 1 Å. To directly measure the transmittance, the spectrophotometer was operated in transmission mode over the wavelength range of 175−3300 nm (Cary 5000 UV-Vis-NIR; Agilent Technologies). A physical property measurement system (Quantum Design, Inc.) was used to investigate the transport properties with four-point geometry. We applied a current and measured the resistance (<10 MΩ) after cooling and subsequent heating. The magnetic properties were investigated using a magnetic property measurement system (Quantum Design, Inc.).

Data availability

The data supporting the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

References

Dong, G. et al. Super-elastic ferroelectric single-crystal membrane with continuous electric dipole rotation. Science 366, 475–479 (2019).

Chen, Z. et al. Freestanding crystalline YBa2Cu3O7−x heterostructure membranes. Phys. Rev. Mater. 3, 060801 (2019).

An, F. et al. Highly flexible and twistable freestanding single crystalline magnetite film with robust magnetism. Adv. Funct. Mater. 30, 2003495 (2020).

Lu, D., Crossley, S., Xu, R., Hikita, Y. & Hwang, H. Y. Freestanding oxide ferroelectric tunnel junction memories transferred onto silicon. Nano Lett. 19, 3999–4003 (2019).

Luo, Z.-D., Peters, J. J. P., Sanchez, A. M. & Alexe, M. Flexible memristors based on single-crystalline ferroelectric tunnel junctions. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 11, 23313–23319 (2019).

Li, R. et al. Preparation and characterization of a flexible ferroelectric tunnel junction. Appl. Phys. Lett. 116, 222904 (2020).

Hong, S. S. et al. Extreme tensile strain states in La0.7Ca0.3MnO3 membranes. Science 368, 71–76 (2020).

Ji, D. et al. Freestanding crystalline oxide perovskites down to the monolayer limit. Nature 570, 87–90 (2019).

Lu, D. et al. Synthesis of freestanding single-crystal perovskite films and heterostructures by etching of sacrificial water-soluble layers. Nat. Mater. 15, 1255–1260 (2016).

Kim, Y. et al. Remote epitaxy through graphene enables two-dimensional material-based layer transfer. Nature 544, 340–343 (2017).

Kum, H. S. et al. Heterogeneous integration of single-crystalline complex-oxide membranes. Nature 578, 75–81 (2020).

Wang, L. et al. One-dimensional electrical contact to a two-dimensional material. Science 342, 614–617 (2013).

Cao, Y. et al. Unconventional superconductivity in magic-angle graphene superlattices. Nature 556, 43–50 (2018).

Sharpe, A. L. et al. Emergent ferromagnetism near three-quarters filling in twisted bilayer graphene. Science 365, 605–608 (2019).

Ohring, M. Materials Science of Thin Films. (Academic Press, Hoboken, United States, 2002).

Fox, M. Optical Properties of Solids. (Oxford University Press, Oxford, United Kingdom, 2010).

Gu, K. et al. Simple method to obtain large‐size single‐crystalline oxide sheets. Adv. Funct. Mater. 30, 2001236 (2020).

Paskiewicz, D. M., Sichel-Tissot, R., Karapetrova, E., Stan, L. & Fong, D. D. Single-crystalline SrRuO3 nanomembranes: A platform for flexible oxide electronics. Nano Lett. 16, 534–542 (2016).

Li, X. et al. Epitaxial liftoff of wafer-scale VO2 nanomembranes for flexible, ultrasensitive tactile sensors. Adv. Mater. Technol. 4, 1800695 (2019).

Inagaki, N., Narushim, K., Tuchida, N. & Miyazaki, K. Surface characterization of plasma-modified poly(ethylene terephthalate) film surfaces. J. Polym. Sci. Pt. B-Polym. Phys. 42, 3727–3740 (2004).

Junkar, I., Vesel, A., Cvelbar, U., Mozetič, M. & Strnad, S. Influence of oxygen and nitrogen plasma treatment on polyethylene terephthalate (PET) polymers. Vacuum 84, 83–85 (2009).

Shrestha, S. et al. Nanometer-thick Sr2IrO4 freestanding films for flexible electronics. ACS Appl. Nano Mater. 3, 6310–6315 (2020).

Thompson, J. et al. Enhanced metallic properties of SrRuO3 thin films via kinetically controlled pulsed laser epitaxy. Appl. Phys. Lett. 109, 161902 (2016).

Chang, Y. J. et al. Fundamental thickness limit of itinerant ferromagnetic SrRuO3 thin films. Phys. Rev. Lett. 103, 057201 (2009).

Xia, J., Siemons, W., Koster, G., Beasley, M. R. & Kapitulnik, A. Critical thickness for itinerant ferromagnetism in ultrathin films of SrRuO3. Phys. Rev. B 79, 140407 (2009).

Lee, S. A. et al. Enhanced electrocatalytic activity via phase transitions in strongly correlated SrRuO3 thin films. Energy Environ. Sci. 10, 924–930 (2017).

Wang, L. et al. Ferroelectrically tunable magnetic skyrmions in ultrathin oxide heterostructures. Nat. Mater. 17, 1087–1094 (2018).

Fang, Z. et al. The anomalous Hall effect and magnetic monopoles in momentum space. Science 302, 92–95 (2003).

Ioffe, A. F. & Regel, A. R. Non-crystalline, amorphous and liquid electronic semiconductors. Prog. Semicond. 4, 237–291 (1960).

Blundell, S. Magnetism in Condensed Matter. (Oxford University Press, Oxford, United Kingdom, 2001).

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by the National R&D programs through the National Research Foundation of Korea, which is funded by the Ministry of Science and ICT (Project Nos.: NRF-2021M3F3A2A03015439 and NRF-2021R1C1C1005042). We acknowledge the support from the Defence Acquisition Program Administration (DAPA) and Agency for Defence Development (ADD) of Korea (Project No.: UD200016GD), the DGIST R&D Program of the Ministry of Science and ICT of Korea (Project Nos.: 22-HRHR+−05, 22-CoE-NT-02, and 21-HRHR-06), and Samsung Electronics Co., Ltd.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

D.K. conducted the experiments and wrote the manuscript under the supervision of S.L. W.K.J. managed the funds from DAPA and ADD of Korea and explored potential military applications.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons license and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Kim, D., Jung, W.K. & Lee, S. Single-crystalline-level properties of ultrathin SrRuO3 flexible membranes with wide and clean surface. npj Flex Electron 6, 24 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41528-022-00155-x

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41528-022-00155-x