Abstract

Flexible organic light-emitting diodes (OLEDs) are promising light sources for biomedical applications. However, the use of these flexible devices has been restricted by their short shelf lifetimes due to poor ambient stability. Here, the fabrication of a long-lived flexible OLED is reported by replacing air-sensitive metals such as aluminum, and alkali metals used as n dopants, with silver. In addition, to achieve stable and efficient flexible OLEDs we tuned the optical cavity length to the second-order interference maximum. The device design has simple encapsulation and leads to an improvement in the air stability of flexible OLEDs which show a shelf lifetime of greater than 130 days whereas the conventional structure exhibits degradation after only 12 days. The proposed design for making flexible OLEDs demonstrates a great potential for using the devices for wearable bioelectronic applications.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

There is growing interest in the use of organic optoelectronics for wearable and biomedical devices1,2,3,4,5,6,7,8,9,10. Organic light-emitting diodes (OLEDs) are attractive light sources for medical applications as they are lightweight, emit light over an area and can be fabricated on flexible substrates. Using flexible OLEDs as wearable light sources has brought many new advances in biomedical applications such as photodynamic therapy1,3 and photobiomodulation11 by introducing non-invasive, precise, and adjustable treatments. A wearable OLED medical device can be easily and conformably integrated with the human body making it a promising light source for outpatient care. Besides the use of OLEDs for therapeutic treatment wearable OLEDs can also be applied as light sources for health monitoring12, muscle contraction sensing2, and optogenetics13.

One important issue that limits the practical application of flexible OLEDs is their short shelf lifetimes due to their sensitivity to oxygen and moisture14,15. This problem of poor ambient stability can cause the formation of dark spots leading to a reduction in light emitting area and non-uniform emission.

In recent years several encapsulation methods including thin film and lamination have been developed to protect flexible OLEDs from environmental degradation15,16,17,18,19. Thin film encapsulation (TFE) techniques based on multi layered structures of alternating inorganic/organic layers and inorganic-based nanolaminate systems can be formed by vacuum processes such as atomic layer deposition (ALD) and chemical vapor deposition. However, these TFEs are complex and are not always effective17. Furthermore, ALD encapsulation generally requires a minimum process temperature of 80 °C. The increased temperature during the ALD process can cause device degradation20.

To make long-lived flexible OLEDs without stringent encapsulation requirements, the structure of inverted OLEDs with a bottom cathode has been proposed14,21,22,23. The advantage of using an inverted structure is that reactive materials such as alkali metals, which significantly reduce the ambient stability of OLEDs can be replaced with metal oxides14. In most reported work based on inverted OLEDs, metal oxides such as ZnO were employed to inject electrons from the electrode to the organic layers14. However, electron injection by metal oxides alone is not sufficient leading to an increase in driving voltage14,24,25. A high driving voltage causes heat generation which can be a particular problem in medical applications where the device may be in contact with the skin3. To reduce driving voltage combining a metal oxide layer and an interlayer has been proposed14. However, the driving voltage was only reduced to about 5 V at a luminance of 1000 cd/m2 14,23 which can still limit the practical application of flexible OLEDs where low power consumption devices are required. Furthermore, this reduction in voltage was achieved by employing a solution-processed interlayer which requires solution coating and annealing processes between the vacuum processes in OLED fabrication and therefore increases process cost. In addition, as metal oxides such as ZnO have high evaporation temperature, a different deposition process, namely sputtering, is used on top of the transparent electrode. ZnO has generally been used on indium-tin-oxide (ITO) which has a sheet resistance too high to achieve good uniformity of light emission in applications requiring large area OLED26,27.

Here, we report the fabrication of long-lived, efficient and operationally stable flexible OLEDs with a low operating voltage of 3.1 V at 1000 cd/m2 by using thermal evaporation only and simplified encapsulation. This was achieved by replacing air-sensitive materials in the device stack. In particular, we replaced the aluminum electrode and n dopants based on alkali metals with silver. Flexible OLEDs based on the new structure have a shelf life greater than 130 days, whereas the conventional flexible device shows degradation after only 12 days. In addition, by extending the cavity length to the second-order interference maximum, operational stability of the devices was significantly improved. To realize efficient OLEDs optical modeling of the entire device stack was used to optimize the cavity length to the second-order interference maximum by increasing the hole transport layer thickness.

Due to the importance of using flexible OLEDs in biomedical applications red phosphorescent OLEDs were developed in this work. This is because red light with a wavelength of 600–700 nm has a higher penetration depth into tissue than shorter wavelengths7.

Results

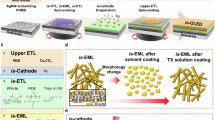

Previously we developed flexible OLEDs that are composed of doped transport layers known as a p-i-n structure that is sandwiched between a reflective metal anode and a semi-transparent metal cathode in a top emission configuration and encapsulated by an epoxy glue (NOA88, Norland) and a commercial polyethylene terephthalate (PET) film with barrier layers3 (LINTEC Corporation) (Fig. 1a). We take this structure as a baseline for assessing adjustments to improve shelf lifetime. Figure 2a, b shows current density–voltage–luminance (J–V–L) characteristics and external quantum efficiency (EQE) as a function of luminance for this baseline device. At a luminance of 1000 cd m−2 OLED devices show an operating voltage of 2.83 V and EQE of 25.2%. This low driving voltage is a requirement for applications in wearable electronics to avoid Joule heating. However, the important issue of these flexible OLEDs is their short shelf lifetimes due to their high sensitivity to oxygen and moisture. Figure 2c, d displays OLED devices degraded after 12 days of storage in air. The degradation could be seen as shrinkage of emission area, reduction of light output and appearance of dark spots.

To improve the environmental stability of the flexible OLEDs we first started to protect layers that are sensitive to oxygen and moisture. As aluminum can react with oxygen, silver was used as a protection layer on top of the aluminum electrode in p-i-n and n-i-p structure (Supplementary Fig. 1). In addition, to achieve operationally stable OLEDs the cavity length was extended to the second-order interference maximum. Outcoupling efficiency calculations in Supplementary Fig. 2 show the optimized thicknesses for the hole transport layer (HTL) and electron transport layer (ETL) are 195–225 nm and 60–70 nm, respectively. Therefore, an HTL thickness of 195 nm and ETL thickness of 60 nm were used for device fabrication to induce the second-order constructive interference effect.

p-i-n and n-i-p structures

The device performance including the current density–luminance–voltage, EQE-luminance, and operating lifetime test for the fabricated p-i-n and n-i-p devices is summarized in Fig. 3. As Fig. 3a, b shows the voltage and EQE at luminance of 1000 cd m−2 is reached at 2.96 V and 16% for the p-i-n devices, while in the case of n-i-p devices the voltage increased to 4 V with lower EQE of 12.4%. The operational lifetimes of the fabricated OLEDs are shown in Fig. 3c. The LT50 (time to 50% of initial luminance) at a current density of 25 mA/cm2 is only 6 h for the n-i-p devices, however, in the case of p-i-n devices, the intensity decayed less than 4% after 17 h. Shelf lifetime measurements of the p-i-n OLEDs showed the formation of dark spots as well as non-uniform emission after 1 month and degradation can be seen more clearly in Supplementary Fig. 3c after 3 months.

Bottom reflective electrode: comparing Al/Ag with Ag electrode

In view of the better performance of the p-i-n device, we explored further refinements of this structure. We next compare the performance of p-i-n OLEDs based on Al (80 nm)–Ag (20 nm) and Ag (100 nm) bottom reflective electrodes (schematic structure of devices is shown in Supplementary Fig. 4a). For further tuning of the second order cavity for devices using Al (80 nm)–Ag (20 nm), we increased the thickness of HTL from 195 nm to 205 nm. The spectrum peak shifts from 594 nm to 610 nm (Supplementary Fig. 5a, b) and the EQE at 1000 cdm−2 increases from 16% to 19.6% (Supplementary Fig. 5c).

Figure 4a shows EQE-luminance characteristics for devices using Al/Ag and Ag reflective electrodes. The EQE at 1000 cdm−2 for devices using an Al/Ag electrode was observed to be 19.6%, however, when the bottom electrode changes to Ag the EQE increased to 26.5%. We performed optical calculations in order to explain the differences in EQE between the devices using Al/Ag and Ag reflective electrodes. Figure 4b illustrates outcoupling efficiency as a function of HTL thickness for devices using Al/Ag and Ag electrodes. For the device using Al/Ag the maximum outcoupling efficiency in the second-order cavity was 24.4% and increased to 27.5% by changing the reflective electrode to Ag. Abs + Ref loss in Fig. 4c shows the ratio of light with a propagation angle less than the critical angle of the emission layer/air interface that could not outcouple owing to losses caused by electrodes (absorption and imperfect reflection) versus total light generated. As Fig. 4c shows for an HTL thickness of 205 nm, which maximizes outcoupling efficiency, the optical losses reduce from 0.14 to 0.114 by changing the bottom reflective electrode from Al/Ag to Ag. Figure 4d shows that coupling to waveguide (WVG) modes and surface plasmon polariton (SPP) modes does not change. Therefore, the improvement in EQE by using a silver electrode is mainly due to a reduction of absorption and reflection loss.

Using an alternative n dopant for electron transport layer

Another reactive material in the conventional p-i-n structure is the Cs used to n-dope the ETL. Therefore, to improve the environmental stability of flexible OLEDs silver was used as an alternative n dopant in the electron transport layer. Bin et al. 28 showed the effect of using silver as an efficient n dopant in a rigid device. Doping efficiency of silver and cesium as n dopants have been previously explained by using ultraviolet photoelectron spectroscopy (UPS) and using low energy inverse photoemission spectroscopy (LEIPS) to measure Fermi level shift. The electron injection barrier reduces due to a shift of the Fermi level toward the lowest unoccupied molecular orbital (LUMO) state by using silver or cesium n dopants. Here, we explore its effect on the shelf lifetime of flexible devices. To study the effect of employing silver on electron transporting properties we first fabricated devices on a glass substrate and compared Ag and Cs doped BPhen (device structure is shown in Supplementary Fig. 4b). Figure 5a shows the J–V–L characteristics of the devices. At a luminance of 1000 cd m−2, the voltage for the devices using Cs as an n dopant is 2.72 V while a voltage of 2.98 V is required for Ag-doped devices. Figure 5b shows EQE as a function of luminance for Ag-doped BPhen using different doping concentrations. The EQE of the Ag-doped devices at 1000 cd m−2 with doping concentrations of 9, 13, and 32 wt% are 22.5%, 19.5%, and 13.8%, respectively. The operational lifetime of the OLEDs using the 9 wt% Ag-doped Bphen was tested at a current density of 25 mA/cm2. As Fig. 5c illustrates they show a stable emission with less than 3% decay in intensity after 30 h. Owing to the rough surface of silver as a reflective electrode29 first order devices were not operationally stable and suddenly shorted, however, extending the cavity length to the second-order interference maximum by increasing HTL thickness can smoothen the surface morphology and therefore, the operational stability of the devices were significantly improved.

Flexible OLED performance based on the modified structure

In the final step of this work, we combined the above elements by making devices on PET substrate employing silver as a reflective electrode and an Ag-doped BPhen electron transport layer (device structure is shown in Fig. 1c). Two different top transparent electrodes of Ag (20 nm) and Au (2 nm)–Ag (10 nm) were used. Our comparative study of J–V–L characteristics for these two electrode layers (Ag (20 nm) versus Au (2 nm)–Ag (10 nm)) shown in Fig. 6a,b indicates that there is a slight difference in terms of operating voltage and EQE. The voltage at 1000 cd m−2 reached 3.1 V with EQE of 22.5% for the devices using Ag (20 nm) while in the case of Au (2 nm)–Ag (10 nm) the voltage increased to 3.3 V with 20% EQE.

The shelf lifetime of the flexible OLEDs with Au (2 nm)–Ag (10 nm) is shown in Fig. 6c. It shows a shelf lifetime of greater than 130 days which exhibits significantly higher air stability than our previous flexible OLEDs. In addition, we found that the flexible OLED based on the new structure not only leads to an improvement of device shelf lifetime in air but also provides sufficient protection to operate the devices in deionized water (Fig. 6d and Supplementary Movie 1). Therefore, these features including low turn-on voltage, high efficiency, water resistivity and air stability based on the new structure make our flexible OLEDs promising for wearable medical devices.

Our results compare favorably with past studies. Several reports on both top and bottom emitting devices showed higher operating voltage (5−12 V) and much shorter lifetime (from 40 h to 30 days)23,30,31. A bottom emitting display was reported showing only a few dark spots after a year14. However, our device shows lower operating voltage and higher efficiency. Another study used multilayer structures consisting of inorganic nanolaminates formed by atomic layer deposition (ALD) and parylene-C for encapsulation15. It achieved similar efficiency and operating voltage, but dark spots appeared after 70 days, whereas our device has lasted more than 130 days without shrinkage of emission area and dark spots. In addition, our encapsulation method avoids the complexity of ALD and the heating of the OLED during the process which can adversely affect the device performance and stability. Further details of this comparison are provided in Supplementary Table 1.

Discussion

In summary, we presented a device design strategy to demonstrate the feasibility of making long-lived flexible OLEDs by using thermal evaporation only and without using a stringent encapsulation technique. Replacing air-sensitive layers such as aluminum as a reflective electrode and alkali metals as an n dopant with silver leads to a significant improvement in ambient stability. In addition, by expanding the cavity to the second-order constructive interference maximum the OLEDs showed an EQE of 22.5% at an initial luminance of 1000 cd m−2 with less than a 3% reduction in intensity after 30 h. Our results enable the development of using OLEDs in wearable bioelectronics applications.

Methods

OLED fabrication

All layers were deposited by thermal evaporation using a thermal evaporator (Angstrom Engineering, EVOVAC vacuum deposition system) with a base pressure lower than 3 × \({10}^{-7}\) mbar. In our conventional structure, a 100 nm aluminum anode was deposited on a PET substrate with barrier layers at a rate of 3 Å/s. In the proposed structure 100 nm silver was deposited on the substrate at a rate of 1 Å/s. The hole transport layer (HTL) consists of a 35 nm 2,2′,7,7′-tetra (N, N-di-p-tolyl) amino-9,9-spirobifluorene (Spiro-TTB) p doped by 2,2-(-(perfluoronaphthalene-2,6-diylidene) dimalononitrile (F6-TCNNQ) (4 wt%) and was deposited at 0.6 Å/s. In a modified structure the optical cavity was extended to the second order by increasing the thickness of HTL to 195 and 205 nm. An electron-blocking layer of NPB (N,N′-bis (naphthalen-1-yl)-N,N′-bis(phenyl)-benzidine) with a thickness of 10 nm was deposited at 0.3 Å/s. A 40 nm emission layer of Ir(MDQ)2(acac) (2-methyldibenzo[f,h]quinoxaline)(acetylacetonate)iridium(III) at (10 wt%) in a NPB host. A hole blocking layer of bis(8-hydroxy-2-methylquinoline) -(4-phenylphenoxy) aluminum (BAlq) was deposited at 0.3 Å/s. A 60 nm electron transport layer of 4,7-diphenyl-1,10- phenanthroline (BPhen) was doped by either Cs or Ag and deposited at 1 Å/s. For the top electrode, 20 nm Ag was deposited at 1 Å/s and an 80 nm NPB capping layer was deposited at 0.6 Å/s. After evaporation, we encapsulated the fabricated OLEDs inside a nitrogen glovebox by using a PET with a barrier, a UV-curable epoxy glue (Norland Optical Adhesive 88), and a moisture getter. Before encapsulation, the glue was baked at 80 °C for one hour inside the glovebox.

OLED characterization

J–V–L characteristics of the OLEDs were measured using a source measurement unit (Keithley 2400), a multimeter (Keithley 2000) and a calibrated silicon photodiode. The electroluminescence (EL) spectrum of the devices was measured by using a spectrograph (MS125, Oriel) connected to a charge-coupled device (CCD) camera (DV420-BU, Andor). EQE values were calculated based on the assumption that the emission profiles of the OLEDs are Lambertian.

OLED simulation

Optical simulation of the devices was performed in Spyder using a custom-made program-based Python programming language. Further details of this simulation are provided in Supplementary Note 1 and the supplementary of ref. 27.

Data availability

The research data underpinning this publication can be accessed at: https://doi.org/10.17630/9f40322e-44b6-4905-a1d1-86ba2c56ebe0.

References

Attili, S. K. et al. An open pilot study of ambulatory photodynamic therapy using a wearable low-irradiance organic light-emitting diode light source in the treatment of nonmelanoma skin cancer. Br. J. Dermatol. 161, 170–173 (2009).

Bansal, A. K., Hou, S., Kulyk, O., Bowman, E. M. & Samuel, I. D. W. Wearable organic optoelectronic sensors for medicine. Adv. Mater. 27, 7638–7644 (2015).

Lian, C. et al. Flexible organic light-emitting diodes for antimicrobial photodynamic therapy. npj Flex. Electron. 3, 18 (2019).

Legabão, B. C. et al. In vitro antifungal activity of curcumin mediated by photodynamic therapy on Sporothrix brasiliensis. Photodiagnosis Photodyn. Ther. 43, 103659 (2023).

Park, Y., Choi, H. R., Shin, J. W., Huh, C. H. & Choi, K. C. A wearable OLED medical device for enhanced cutaneous wound healing and patient comfort: revolutionizing dermatology. J. Inf. Disp. https://doi.org/10.1080/15980316.2023.2232560 (2023).

Murawski, C., Gather, M. C. Emerging biomedical applications of organic light-emitting diodes. Adv. Opt. Mater. https://doi.org/10.1002/adom.202100269 (2021).

Piksa, M. et al. The role of the light source in antimicrobial photodynamic therapy. Chem. Soc. Rev. 52, 1697–1722, (2023).

Cabral, F. V. et al. Organic light‐emitting diodes as an innovative approach for treating cutaneous leishmaniasis, Adv. Mater. Technol. https://doi.org/10.1002/admt.202100395 (2021).

Jeon, Y., Choi, H. R., Park, K. C. & Choi, K. C. Flexible organic light‐emitting‐diode‐based photonic skin for attachable phototherapeutics. J. Soc. Inf. Disp. 28, 324–332 (2020).

Choi, S. et al. Wearable photomedicine for neonatal jaundice treatment using blue organic light‐emitting diodes (OLEDs): toward textile‐based wearable phototherapeutics.Adv. Sci. 9, 2204622 (2022).

Wu, X. et al. Organic light-emitting diode improves diabetic cutaneous wound healing in rats. Wound Repair Regen. 23, 104–114 (2015).

Kim, C. H. Inf. Disp. 37, 14 (2021).

Murawski, C., Pulver, S. R. & Gather, M. C. Segment-specific optogenetic stimulation in Drosophila melanogaster with linear arrays of organic light-emitting diodes. Nat. Commun. 11, 1 (2020).

Fukagawa, H. et al. Long‐lived flexible displays employing efficient and stable inverted organic light‐emitting diodes. Adv. Mater. 30, 1 (2018).

Keum, C. et al. A substrateless, flexible, and water-resistant organic light-emitting diode. Nat. Commun. 11, 1 (2020).

Jeong, S. Y. et al. Highly air-stable, flexible, and water-resistive 2D titanium carbide MXene-based RGB organic light-emitting diode displays for transparent free-form electronics. ACS Nano 17, 10353–10364 (2023).

Jeong, E. G., Kwon, J. H., Kang, K. S., Jeong, S. Y. & Choi, K. C. A review of highly reliable flexible encapsulation technologies towards rollable and foldable OLEDs. J. Inf. Disp. 21, 19–32 (2020).

Choi, D. K. et al. Anomalous collapses of Nares Strait ice arches leads to enhanced export of Arctic sea ice. Nat. Commun. 12, 1 (2021).

Wu, J. et al. Efficient multi-barrier thin film encapsulation of OLED using alternating Al(2)O(3) and polymer layers. RSC Adv. 8, 5721–5727 (2018).

Deng, Y., Keum, C., Hillebrandt, S., Murawski, C. & Gather, M. C. Improving the thermal stability of top‐emitting organic light‐emitting diodes by modification of the anode interface, Adv. Opt. Mater. https://doi.org/10.1002/adom.202001642 (2021).

Morii, K. et al. Encapsulation-free hybrid organic-inorganic light-emitting diodes. Appl. Phys. Lett. 89, 1 (2006).

Fukagawa, H. et al. Highly efficient and air-stable inverted organic light-emitting diode composed of inert materials. Appl. Phys. Express 7, 16 (2014).

Yokota, T. et al. Air-stable ultra-flexible organic photonic system for cardiovascular monitoring. Adv. Mater. Technol. 1, 2200454 (2022).

Sessolo, M. & Bolink, H. J. Hybrid organic-inorganic light-emitting diodes. Adv. Mater. 23, 1829–1845 (2011).

Kabra, D., Song, M. H., Wenger, B., Friend, R. H. & Snaith, H. J. High efficiency composite metal oxide‐polymer electroluminescent devices: a morphological and material based investigation. Adv. Mater. 20, 3447–3452 (2008).

Schwab, T. et al. Highly efficient color-stable inverted white top‐emitting OLEDs with ultra‐thin wetting layer top electrodes. Adv. Opt. Mater. 1, 707–713 (2013).

Riahi, M., Yoshida, K., Hafeez, H. & Samuel, I. D. W. Adv. Electron. Mater. 2300675, 1 (2023).

Bin, Z. et al. Making silver a stronger n-dopant than cesium via in situ coordination reaction for organic electronics. Nat. Commun. 10, 1 (2019).

Qian, M. et al. A stacked Al/Ag anode for short circuit protection in ITO free top-emitting organic light-emitting diodes. RSC Adv. 5, 96478–96482 (2015).

Jinno, H. et al. Self-powered ultraflexible photonic skin for continuous bio-signal detection via air-operation-stable polymer light-emitting diodes. Nat. Commun. 12, 4 (2021).

Han, Y. C. et al. Reliable thin-film encapsulation of flexible OLEDs and enhancing their bending characteristics through mechanical analysis. RSC Adv. 6, 40835–40843 (2016).

Acknowledgements

The authors are grateful to the Engineering and Physical Sciences Research Council (Grant No. EP/R035164/1 for financial support. We would like to thank LINTEC Corporation for providing the barrier film for the flexible OLEDs.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Ifor D. W. Samuel (I.D.W.S.) conceived the project and supervised the research. Mina Riahi (M.R.) designed and made the OLEDs and wrote the first draft of the manuscript. Kou Yoshida (K.Y.) performed the optical modeling of OLEDs and edited the first draft of the manuscript. Ifor D. W. Samuel (I.D.W.S.) edited the first draft and the revised version of the manuscript. All authors have read and approved the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Riahi, M., Yoshida, K. & Samuel, I.D.W. Improving the air stability of flexible top-emitting organic light-emitting diodes. npj Flex Electron 8, 51 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41528-024-00338-8

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41528-024-00338-8