Abstract

Neural representations arise from high-dimensional population activity, but current neuromodulation methods lack the precision to write information into the central nervous system at this complexity. In this perspective, we propose high-dimensional stimulation as an approach to better approximate natural neural codes for brain-machine interfaces. Key advancements in resolution, coverage, and safety are essential, with flexible microelectrode arrays offering a promising path toward precise synthetic neural codes.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Humans possess approximately 86 billion neurons in the brain and 200 million neurons in the spinal cord1,2, forming highly interconnected networks that underlie complex behaviors and sensory processing. Neural codes for sensations and motor control emerge from these networks and are often conceptualized as states or trajectories in a high-dimensional space, where each dimension corresponds to the activity of a single neuron or latent feature derived from neural population dynamics3. At any given moment, the firing rates of a neuronal population represent a single point in this space, and as these rates evolve over time, they trace a neural trajectory. These trajectories are thought to be confined to manifolds within the high-dimensional space, with the manifold’s dimensionality reflecting the complexity of the encoded information4,5.

Both sensory and motor systems leverage these intrinsically complex neural states to encode and integrate multiple variables. For example, the somatosensory cortex encodes texture using fine-grained patterns of neural activity, with approximately 30 principal components required to distinguish pairs of textures6,7. Similarly, in the visual pathway, the dimensionality of object representations increases at different stages, with area V4 requiring 40 dimensions and the inferotemporal cortex nearly 100 dimensions to represent local image patches8,9. Neuronal populations in the primary visual cortex (V1) encode features such as edges, motion, and brightness, while also integrating non-visual cues like locomotion, highlighting the adaptability of sensory processing10. Moreover, even motor tasks, traditionally considered to rely on low-dimensional neural dynamics, have been argued to form a rich, context-dependent dynamical mechanism in the motor cortex, resembling high-dimensional reservoirs of neural activity patterns11. These insights from natural neural activity have significant implications for artificial stimulation in brain-machine interfaces (BMIs) and other applications. They emphasize the need for high-dimensional control of neural activity, achievable through spatiotemporally precise stimulation across many degrees of freedom.

On the technological front, recent advances in neural microelectrode arrays (MEAs), both rigid and flexible, have dramatically increased the number of channels available for recording neural activity, now reaching hundreds or even thousands of channels12,13,14,15,16,17,18. These advancements have driven significant strides in “read-out” capacities, paving the way for large-scale BMIs to control robotic arms19, move cursors20, and decode speech21 at scales not available previously. However, despite these breakthroughs, “write-in” capabilities have lagged behind. Most existing stimulation strategies employ a single or few stimulating electrodes at a time to modulate neural populations, often resulting in synchronized activation or suppression of nearby neurons. This coarse approach frequently results in unnatural perceptions, hindering the effectiveness of current neuroprosthetic technologies22,23,24.

These limitations highlight a critical gap in leveraging high-dimensional stimulation to achieve more naturalistic and precise sensory and motion restoration. A key challenge lies in the lack of interfacing strategies to reliably generate the complex activity patterns underlying diverse brain states. While substantial progress has been made in developing flexible, conformal MEAs to enhance recording longevity and increase sensing density25, their application in stimulation is still in their early stages26,27,28,29,30,31,32,33,34. However, their potential to improve stimulation performance is increasingly being recognized. In this perspective, we propose the necessity of high-dimensional stimulation, outline the challenges inherent in implementing such paradigms, and express our optimism that flexible and conformal MEAs offer a promising avenue for generating naturalistic artificial neural codes.

High-dimensional stimulation: unlocking access to complex neural states

We argue that accessing and modulating complex neural states requires a fundamental technological shift towards high-dimensional stimulation, moving beyond the limitations of traditional techniques. This entails deploying a large number of spatially distributed, independently controlled stimulating electrodes that interface with neural populations, enabling more selective activation of specific subsets of neurons. Additionally, time-varying stimulation patterns can guide the temporal evolution of brain states within their high-dimensional manifold. By perturbing neural activity to approximate the trajectories associated with specific sensations or movements, this approach holds potential to enable high-capacity neuroprostheses capable of more naturalistic and effective sensory and motor restoration.

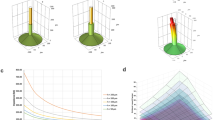

To illustrate this concept, we simulated the responses of a neuronal population to spatiotemporally patterned microstimulations using an MEA. The simulation was based on the cortical column model of Potjans and Diesmann (2014) and implemented with NEST 3.8, encompassing 3858 neurons in total (Fig. 1a)35,36. Our results demonstrate that increasing the number of stimulating electrodes from one to 32, still far fewer than the total number of neurons, produces diverse neural responses with dimensionality approaching that of spontaneous activity (Fig. 1b–d). Single-electrode stimulation activates the entire cortical column, resulting in highly synchronized, low-dimensional neural activity. In contrast, splitting the stimulation across multiple independent electrodes creates spatiotemporally distributed patterns, producing more complex responses with dimensionality closer to natural neural activity. Furthermore, as the number of independently controlled stimulation electrodes increases, the stimulation-evoked manifold exhibits greater overlap with the baseline manifold. This increased overlap is driven by the reduction of synchrony in the evoked activity, leading to more distributed and naturalistic neural responses (Fig. 1b, c, e). These results suggest that high-dimensional stimulation has potential to approximate arbitrary patterns of neural activity, even without precise knowledge of the neural code. Importantly, these results are not restricted to depth-wise MEAs but are generalizable to lateral MEA configurations as well.

a Schematic illustration of implanted neural MEA in a sensory cortex microcircuit model implemented in NEST. Each cortical layer (L2/3, L4, L5, L6) consists of a population of excitatory and inhibitory neurons. Extracellular electrical stimulation recruits neurons based on a simplified induced intracellular current model, which is inversely proportional to the distance from the stimulation site35,36. For clarity, only 16 electrodes of the MEA are shown in the column, although all 32 electrodes were used in the simulation. b Raster plots showing neural activity recorded from 3858 neurons at baseline and under different stimulation configurations for 60 s. All neurons receive independent Poisson background inputs, with layer and population-specific rates. Stimulation is performed by grouping 32 electrodes into 1, 2, 4, 8, 16, and 32 independent stimulation groups, with within-group electrodes sending identical current pulses. Each group’s pulse times are drawn from a Poisson distribution at 10 Hz, with an amplitude of 2 µA. c Natural (black) and stimulated (blue) neural states. Firing rates are calculated in 500 ms windows with 400 ms overlap for each group of electrodes. The resulting time-series matrix, with rows as time samples and columns as electrode indices, is projected into a 3D subspace using principal component analysis (PCA). Stimulated neural states are then projected onto the 3D PCA subspace derived from the baseline data, allowing for a direct comparison to the baseline neural activity manifold. An ellipsoid is fitted to the lower-dimensional data to estimate volume under both conditions. d The number of PCA components required to explain 85% of the variance increases as the number of independent stimulation groups increases. e The volume overlap between the baseline and stimulation-evoked manifolds increases as the number of independent stimulation groups increases. a adapted from ref. 35. licensed under CC BY-NC 3.0.

However, inherent and practical challenges persist for microstimulation. Biophysically, electrical stimulation often excites neurons through the passage of axons, leading to spatially distributed activation patterns37. Additionally, because the activation thresholds are governed by the electrical excitability of the local cell membrane, primarily influenced by properties such as myelination and geometry, it lacks specificity for selectively targeting distinct neuronal populations, such as excitatory and inhibitory cells38. Nevertheless, we argue that these are not insurmountable obstacles. Spatial focality and cell-type selectivity can be shaped by stimulation parameters such as amplitude, frequency, and duration39,40; using flexible MEAs to reduce stimulation current also demonstrates improvement in spatial targeting26. Furthermore, leveraging structural or functional regularities in the sensory cortices, such as topographic maps and cortical columns, can steer the population closer to the desired manifold41. For example, stimulation in the hand areas of primary somatosensory cortex (S1) has been shown to elicit precise sensations in the fingers42,43,44,45. At a finer spatial scale, neurons in primary visual cortex (V1) are organized into orientation-tuned columns46. In higher-order visual areas, stimulation of single columns has been shown to bias judgments of motion direction toward the column’s preferred direction47. Thus, we advocate that high-density MEAs, when aligned with anatomical-functional maps and combined with optimization of stimulation parameters, offer a powerful and promising path toward generating functionally meaningful, near-manifold synthetic neural codes.

For this perspective, we focus on the electrode interface to achieve high-dimensional stimulation in BMIs, while only briefly touching on considerations of backend electronics and algorithms in the conclusion. We examine key technical obstacles and highlight flexible electrode technology as a promising solution. We also review recent efforts in high-dimensional stimulation across various BMI applications and explore how flexible MEAs are driving advancements in the field.

Enabling high-dimensional stimulation through flexible MEAs: challenges and solutions

High-dimensional stimulation, as previously illustrated, improves access to naturally high-dimensional neural states underlying sensations and movements. However, implementing this paradigm presents technical challenges, including the need to lower stimulation thresholds, increase precision of stimulation, improve tissue integration, and scale up electrode density and coverage. These challenges are interconnected and rely upon the MEA’s stable and intimate interface with neural tissue. We argue that flexible MEAs uniquely address these challenges by promoting long-term tissue compatibility, enabling precise spatiotemporal stimulation, supporting high-density configurations, and maintaining long-term stability.

Intimate electrode-tissue integration for stimulation safety and precision

Stimulation-induced tissue damage is typically linked to excessive charge density or charge per phase delivered to the nervous system. At the single electrode level, Shannon’s equation is commonly used to predict these damage thresholds, although it was developed using macroelectrode data and may not fully apply to microelectrodes48,49. A later study found that charge per phase was significantly correlated with tissue damage when using microelectrodes, whereas charge density did not exhibit a statistically significant correlation50. These criteria are not directly applicable to high-dimensional stimulation paradigms, where many electrodes are activated simultaneously or in rapid succession. As the number of electrodes used increases, so does the risk of cortical kindling and seizures, particularly when the stimulation currents are not sufficiently low51,52,53. Although dynamic sequential stimulation52 can mitigate these safety concerns by reducing the overall charge delivered per second, it often comes at the cost of temporal control and throughput, which can be suboptimal for certain applications52,54. For instance, in the somatosensory system, neurons involved in texture perception are highly sensitive to spike timing. Neurons receiving strong inputs from Pacinian corpuscle fibers, which respond to vibrations, can exhibit phase-locked responses at frequencies as high as 1000 Hz7,55. This sensitivity highlights the critical importance of precise temporal control, as deviations in spike timing can impair encoding of tactile information.

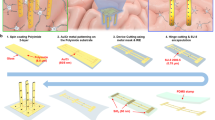

Therefore, reducing stimulation current is crucial for reducing the risk of tissue injury in high-dimensional stimulation paradigms. However, low stimulation currents are only effective if they elicit a relevant physiological effect, such as a perceptible sensation or functional movement. The minimum current required to elicit such a response in a proportion of trials, such as 50% of the time, is referred to as the stimulation threshold. Intuitively, the stimulation threshold is strongly influenced by the distance of the electrode from the target neurons (Fig. 2a, b). This relationship is evident when comparing surface arrays to penetrating MEAs. Surface arrays, while offering wide spatial coverage, typically require higher stimulation amplitudes due to their considerable distance from the cortex, typically ranging from hundreds of microamps to milliamps23,52,56. These high thresholds often result in off-target effects caused by non-focal recruitment of neural populations. For example, stimulation of somatosensory cortex has even been shown to evoke unwanted motor movement near the sensory perception threshold, likely due to current spread to motor cortex56. In contrast, penetrating MEAs directly interface with neural tissue, enabling significantly lower thresholds, often just a small fraction of the current required for surface arrays26,57,58. Such intracortical microstimulation (ICMS) has demonstrated remarkable selectivity, evoking sensations in individual fingertips and generating precise letters and shapes in the visual field42,59. Furthermore, ICMS in human patients maintained relatively stable detection thresholds in a human patient for over 1500 days60.

a Representative MEAs. From left to right: Conventional surface electrode array, conformal surface electrode array, rigid Utah MEA, and flexible intracortical MEA. b Comparison of current amplitude and the number of neurons directly activated across various electrical stimulation modalities and natural activity (ion channel). For intracortical MEAs, larger and lighter shade bars represent rigid MEAs, while smaller and darker shade bars represent flexible MEAs. For surface arrays, larger and lighter shade bars represent conventional surface arrays, while smaller and darker shade bars represent conformal surface arrays. c Literature comparison of ICMS behavioral detection thresholds in rodents, non-human primates, and humans using either chronically implanted rigid or flexible MEAs. Minimum reported or deduced values are plotted. a Left reprinted with permission from PMT Corporation; left-middle reprinted from ref. 145 licensed under CC BY-NC 4.0; right-middle reprinted from ref. 146. licensed under CC BY-NC-SA 4.0, right adapted with permission from ref. 26, Elsevier. b data sources: Intracortical MEAs (rigid): activation estimates from ref. 147, current range from ref. 57. Intracortical MEAs (flexible): activation estimates from ref. 147, current range from refs. 26,27. Deep brain stimulation (DBS): activation estimates from refs. 148,149, current range from ref. 150. Surface arrays (conformal): activation estimates from ref. 151, current range from refs. 31,32,33. Surface arrays (conventional): activation estimates from ref. 151, current range from ref. 62. Panel c adapted with permission from ref. 26, Elsevier. c data sources: 1: Urdaneta et al.79; 2: Flesher et al.22; 3: Hughes et al.60; 4: Fernandez et al.59; 5: Callier et al.152; 6: Ferroni et al.153; 7: Ni et al.154; 8: Sombeck et al.155; 9: Schmidt et al.57; 10: Fifer et al.42; 11: Smith et al.156; 12: Ye et al.30; 13: Orlemann et al.27; 14: Lycke et al. (minimum charge/frequency)26; 15: Lycke et al. (minimum charge)26.

It is worth noting that for both penetrating MEAs and surface arrays, the use of flexible or conformal designs, which establish a more intimate tissue interface compared to rigid or conventional electrodes, further reduces the distance to target neurons and lowers the current required for stimulation (Fig. 2a, b)26,27,30,31,32,33,34. The flexibility and conformability of penetrating MEAs and surface arrays are often achieved through the use of flexible substrates such as polyimide, parylene-C, PDMS, and SU-8, alongside structural designs like reduced electrode thickness, increased porosity, and micro-patterned or serpentine structures that enhance adaptability to the soft and dynamic neural environment61.

Despite relatively limited use in stimulation, studies employing flexible intracortical MEAs have demonstrated significantly lower detection thresholds26,27,30. The lowest threshold to elicit behavioral detection is remarkably just 1.5 µA (0.25 nC/phase)26 (Fig. 2c). Conformal surface arrays, though detection thresholds have yet to be reported, operate at tens to hundreds of microamps, significantly lower than the milliamps typically required by conventional surface arrays62. For example, a conformal surface array demonstrated improved activation confinement in the visual cortex using currents as low as 30 µA in a bipolar configuration, compared to traditional unipolar configurations31. Similarly, Neuroweb used low amplitude pulses of 30 µA and observed increased firing rates, although the results did not reach statistical significance33. Additionally, the “Layer 7 Cortical Interface” used 50–100 µA pulses in the visual cortex and detected evoked spiking, although no saccades were observed32. While these early studies are encouraging, the limited number of investigations—mostly conducted in rodent and other animal models—calls for further validation. Nevertheless, evidence from both flexible penetrating MEAs and conformal surface arrays underscores the impact of improved tissue integration and closer proximity to target neurons in enabling more efficient stimulation.

Notably, lower stimulation thresholds are not only essential for safe operation under the high-dimensional stimulation paradigms but also enable higher-resolution, more precise stimulation. Despite ongoing debates regarding the mechanism of neural activation by electrical stimulation37,63,64, in vivo studies have consistently shown that reducing the amplitude of stimulation currents improves the spatial specificity of stimulation, enabling neuronal activation to be confined from multiple cortical columns to a single column, a single cortical layer, and even a few neurons26,65,66,67. Thus, to preserve as much of the high-dimensional nature of natural neural coding as possible, it is imperative to use small currents that allow for focal activation of neuronal populations.

Implantation of large arrays with sufficient density and coverage

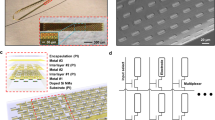

Another major challenge in achieving high-dimensional stimulation is to balance sufficient spatial coverage with high-density electrode placement. Achieving this requires neural interfaces to provide sufficient resolution and coverage across all three dimensions. High-density arrays with broad coverage spanning functional regions are especially critical for restoring complex perceptual functions that rely on coordinated activity across distributed cortical or spinal subregions (Fig. 3). The scale of this requirement presents a major engineering challenge. For example, restoring vision in blind patients by interfacing with the primary visual cortex (V1) to achieve visual acuity beyond legal blindness (20/200 visual acuity and a 20-degree visual field, equivalent to a resolution of 0.16 degrees)68 would require a collection of MEAs with over 30,000 independent electrodes distributed across a 15 cm² area, far exceeding the capabilities of current technology.

Illustration of functional mapping in human BMI and prostheses. a Schematics of the central nervous system; implant locations of example applications are marked with black rectangle. b For sensory BMI, one Utah MEA only covers a 4 × 4 mm2 region, while human brain uses about 2 × 3 cm2 to represent a single-hand in the somatosensory cortex157. Each colored region in the cortical map corresponds to a certain finger from which it receives perception. c Two Utah MEAs implanted at different sites on a visuotopic map of the visual cortex, which is about 15 cm2, and the conceptual illustration of their elicited phosphenes in the vision field158. Although the resolution of a single phosphene can be less than 1 degree, achieving an average resolution equivalent to the threshold for legal blindness (0.16 degrees across a 20-degree visual field) remains a distant goal. d Three spinal cord segments responsible for controlling the lower limb. Currently, standard epidural arrays, such as the Medtronic 5-6-5 paddle lead116 recruit multiple motor pools and generate global movements of a large muscle group. They lack the precision to target individual rootlets and control specific muscles separately. Each colored spinal cord root controls a group of muscle of the human lower limb with the same color. Middle panel adapted from ref. 158 licensed under CC BY 4.0.

In addition, vertical coverage and resolution play a critical role in extending the dimensionality of stimulation. In the cortex, vertically oriented pyramidal neurons are generally considered the primary target of stimulation63. Although the typical size of human pyramidal neurons is about 20 µm, they spread across most cortical layers, with an average cortical depth of 2.5 mm and a maximum of 4.5 mm69. Studies have reported layer-specific activity dynamics and their distinct roles in triggering perception70. Therefore, achieving depth coverage and resolution will enhance selectivity and increase the dimensionality of stimulation. Existing stimulating technologies, such as the Utah MEA and surface array, lack such depth resolution, indicating a critical gap for future technical developments.

The balance of coverage and density becomes especially challenging for penetrating MEAs due to their invasive nature. Implanting many MEAs at high densities significantly increases the risk of tissue damage. For example, a recent study demonstrated that the chronic implantation of 16 Utah MEAs in the monkey visual cortex led to extensive cortical lesions spanning the full depth of the dorsal V1 and underlying white matter, which ultimately resulted in blindness in the subject71.

Flexible electrodes, being less invasive than rigid ones, offer a promising approach for improving coverage and density while mitigating tissue damage. Recent advancements have demonstrated the feasibility of implanting large numbers of flexible probes while maintaining stable tissue integration and scalability. For instance, one study successfully distributed 1024 electrodes of polymer MEAs across multiple regions in rats, recording over 300 single units for more than 160 days72. More recently, multiple flexible MEAs were implanted in the mouse V1 cortex with high volumetric density, comprising 64 probes with 1024 contacts within approximately 1 mm3. This design achieved volumetric coverage with an electrode/contact density exceeding 1000 electrodes per mm3 15.

However, implanting flexible electrodes with high density, precision, and broad coverage requires advanced and technically complex implantation techniques. Early approaches, such as increasing probe thickness73, reducing effective length74, and adding rigid support structures75, focused on enhancing stiffness to facilitate manual implantation, often at the cost of stable tissue integration. Later developments introduced techniques such as coating flexible MEAs with dissolvable rigid layers76 or using shuttle devices with retractable guiding wires77, which minimized implantation trauma while maintaining insertion efficiency. However, these methods remain labor-intensive and challenging to scale for achieving large-area neural coverage. More recently, Neuralink introduced an innovative and scalable platform, capable of implanting flexible polymer probes at a rate of approximately 30 probes per minute78. This system represents significant progress towards fast, automated implantation of high-density flexible electrodes. Its scalable design and automation mark an important step forward in realizing large-coverage, high-density neural prostheses, highlighting the immense potential of flexible MEAs to transform neural interfacing by combining precision, scalability, and robust tissue integration for a wide range of applications.

Chronic stability for long-lasting stimulation

In the pursuit of complex, high-dimensional stimulation paradigms for restoring advanced sensory and motor functions, chronic stability is essential for ensuring the long-term functionality, safety, and effectiveness of neural interfaces. However, maintaining consistent and low stimulation thresholds over extended periods remains a significant challenge. Traditional intracortical MEAs have exhibited diverse variations during chronic stimulation. In cases where stimulation thresholds increased, the magnitude of increase was potentially linked to the severity of foreign body responses in a cortical layer-dependent manner, suggesting that adverse tissue reactions are a primary driver of these chronic variations71,79,80,81,82,83. Even in instances where no significant longitudinal changes in detection thresholds were observed, session-to-session variations were substantial, often comparable to the current levels themselves used for stimulation60. Moreover, histological and explant analyses of multi-year chronic implants consistently reveal adverse effects of rigid MEAs on surrounding tissue84, including scar encapsulation, material degradation, and lesions79,85,86,87,88,89. These findings underscore the critical role of adverse tissue responses in undermining the chronic functional stability performance of neural interfaces.

Emerging flexible MEAs have substantially mitigated adverse tissue responses during chronic implantation by leveraging two key properties. First, their high flexibility allows them to conform to tissue micromovements, effectively minimizing interfacial forces and reducing chronic inflammation90,91. Second, their implantation processes can be meticulously engineered to minimize surgical damage and promote tissue recovery, further enhancing tissue integration92.

Although polymer electrodes do not experience corrosion, delamination of the layers consisting of the stack of metallization, adhesion, and insulating substrate is a common failure mode93. This can be exacerbated with mechanical strain due to mismatch in mechanical properties between the metal and polymer layers, as well as by electrical stimulation. A few recent studies have successfully addressed these challenges, demonstrating remarkable durability and longevity in stimulation using flexible polymer electrodes. For example, the use of IrOx/NanoPt as adhesion promotor between metal contacts and poly(3,4-ethylenedioxythiophene) (PEDOT) significantly enhances the electrode’s integrity under extensive stimulation94. This approach enables 10–15 µm-thick polyimide MEAs to endure rigorous in vitro tests, including over 10,000 redox cycles, 110 days under accelerated aging conditions at 60 °C, and continuous pulsing at 18 and 25 µA for up to 10 billion pulses at 1000 Hz27,94. Alternatively, wafer-scale sputter coating of IrOx, combined with microfabricated cap rings over each contact for structural reinforcement, enabled robust and stable stimulation by 1 µm-thick ultraflexible MEAs in vivo for over 200 days26. Notably, the interday variations of behavioral detectability in this study were at or smaller than 1 µA, reaching the current resolution of the stimulator, and an order of magnitude smaller than the variations using conventional MEAs26. These results highlight the potential of flexible MEAs to achieve long-term stable stimulation, paving the way for advancements in neuroprosthetics and BMI applications.

Applications of high-dimensional stimulation in brain-machine interface

In the previous section, we outlined the technical challenges associated with high-dimensional stimulation and demonstrated how flexible neural interfaces provide a viable solution. In this section, we discuss high-dimensional stimulation as a powerful technology for “writing in” neural activity in two-way BMI applications, with a particular focus on its potential to restore sensations and movement in patients affected by injury or disease. We review key progress in high-dimensional stimulation paradigms across three application areas: the somatosensory cortex, the visual cortex, and the spinal cord. For each domain, we examine the complexity of the underlying functions, the demands for precise control of intricate neural activity, and highlight recent advances and remaining gaps that flexible electrode technologies show promise in overcoming.

Somatosensory cortical BMI

Sensory feedback is essential for interacting with the physical world, enabling coordinated movements, regulating grasp force, and even maintaining social bonds19,95,96. Millions of individuals with neurological disorders or injuries experience impaired sensory pathways to the somatosensory cortex, resulting in losing this critical feedback. A bidirectional BMI could bridge this gap and restore lost functions and improve quality of life by decoding motor commands from the brain to control movements and delivering sensory feedback directly to the somatosensory cortex97. High-dimensional stimulation, with its potential to replicate complex, naturalistic sensory experiences, represents a promising approach to achieving this goal.

Early human studies used sequential single-channel, single-frequency stimulations and were able to successfully generate localized sensations in the hand and arm regions22,23,24. Patients reported a variety of sensations, including “squeeze”, “tingle”, “pressure”, “buzzing”, and proprioceptive experiences such as a sense of rightward movement. However, these initial studies primarily focused on the location and intensity of the evoked sensations, rather than their naturalness. Many sensations were categorized as “possibly natural” or “less natural” frequently characterized by paresthetic qualities like tingling or an electrical buzz22,23,24. This prevalence of unnatural sensations highlights the limitations of low-dimensional stimulation, which cannot replicate the intricate spatiotemporal patterns of natural neural activity.

To address these limitations, researchers have adopted biomimetic stimulation strategies that aim to better approximate the natural coding of tactile events98. For example, by mimicking the spatiotemporal dynamics of cortical neurons in response to mechanical indentation, biomimetic stimulation employs four electrodes simultaneously during the onset and reduces to a single electrode during the sustained phase44,55. Temporally, stimulation frequency or amplitude peaks at both the onset and offset of contact to drive enhanced neural firing44,55. These biomimetically informed stimulation patterns, applied in both peripheral and cortical systems, have successfully replicated some of key dynamics, evoking more realistic tactile sensations44,99,100,101. Furthermore, spatiotemporal patterning of ICMS using groups of two to seven electrodes has been shown to evoke sensations of curves, edges, and movement, effectively mimicking more complex features of tactile perception45. In these experiments, electrodes with spatially aligned projected fields (PFs) on the hand were stimulated to generate edge-like sensations with specific orientations. By modulating the amplitude and timing of stimulation pulses, researchers modeled natural touch responses, enabling perception of concave and convex surfaces. By incorporating biomimetic principles, these stimulation protocols have achieved significant progress in producing realistic tactile sensations.

Despite its considerable promise, biomimetic stimulation still faces notable challenges. Although studies have recorded high-dimensional neural activity in response to texture perception, replicating these patterns is difficult6. ICMS produced by current clinically applicable MEAs has a coarse spatiotemporal resolution, making it difficult to evoke neural activity that closely resembles natural tactile coding. Additionally, the vast parameter space of stimulation variables, ranging from amplitude to frequency across many electrodes, further complicates the design of effective stimulation. Although learning-based approach could avoid the need of precisely replicate neural code, it requires extensive user training and cognitive effort, which may not be practical for all applications102.

Ultimately, generating naturalistic sensations requires high-dimensional stimulation protocols that go beyond the current limitations in channel count and spatial coverage. Achieving this will require dense MEAs spanning both the surface and depth of the somatosensory cortex, effectively stimulating all hand areas to create diverse tactile experiences. Flexible MEAs offer a promising solution by lowering stimulation thresholds, maintaining chronic stability, and enabling high-density implantation, ultimately enhancing the realism of hand sensations.

Visual cortical prostheses

Over 40 million individuals worldwide are blind, yet no effective treatment exists to fully restore vision. Researchers have long aspired to develop visual prosthetics by directly stimulating the visual cortex using intracortical MEAs or surface arrays to elicit visual sensations103,104,105,106. Such stimulations typically induce small spots of light in the visual field, known as phosphenes103. In principle, a multitude of phosphenes could be combined to create complex visual perceptions such as shapes and patterns. However, for decades after the discovery of this phenomenon, the number of phosphenes that could be reliably induced in a single subject remained low, limiting the ability to construct detailed shapes or patterns57,104.

Recent breakthroughs have demonstrated that spatiotemporal patterned cortical stimulation can generate complex visual perceptions. For instance, patterned stimulation using 14 Utah MEAs implanted in monkey V1 cortex successfully elicited shape perception107. Similarly, surface arrays employing the technique of dynamic current steering, rapidly shifting stimulation across pairs of electrodes, enabled shape perceptions in human patients52,108. These advancements underscore the importance of spatiotemporal patterning in stimulation to restore vision beyond the perception of simple phosphenes.

It is worth noting that, despite these groundbreaking advances, current progress remains limited in eliciting the high-dimensional states necessary for natural visual perception. One significant challenge is achieving both resolution and coverage simultaneously, as discussed in Section “Enabling high-dimensional stimulation through flexible MEAs: challenges and solutions”. For instance, the study on shape perception in monkeys, which represents the highest channel count visual prosthesis to date107, still achieved coverage and resolution levels far below the threshold for legal blindness. In addition, the currents used in these studies are relatively high: up to 2 mA for surface arrays52 and 50 µA for penetrating MEAs107. These large currents fundamentally limit the scalability and flexibility of spatiotemporal patterning, as they risk inducing tissue damage with prolonged or extensive stimulation. In contrast, the perceptual threshold for visual cortical stimulation using flexible polymer electrodes can be as low as 3.3 µA27. Furthermore, even thinner and more flexible MEAs could elicit behavioral detection at currents as low as 1.5 µA26, highlighting their potential for safer and more precise high-dimensional stimulation for visual prostheses.

Spinal cord stimulation

For spinal cord injury (SCI), where communication between the brain and spinal networks is disrupted, spinal cord stimulation has emerged as a promising tool for both motor recovery and sensory restoration, particularly in facilitating critical routine activities such as walking. The spinal cord integrates sensory information from the periphery toward the brain and distributes motor commands from the brain to muscles109. Its functional organization follows a dorso-ventral gradient, with dorsal regions primarily processing sensory input and ventral regions primarily dedicated to motor output110. Additionally, its connections to skin and muscles via the dorsal and ventral roots underscore its pivotal role in coordinating motor and sensory integration109.

The functional mechanisms of spinal cord stimulation can be broadly categorized into two groups: enabling effects111 and inducing effects112. Enabling effects enhance the spinal cord circuits’ responsiveness to motor commands, while inducing effects directly activate muscles or muscle groups through stimulation. Noninvasive transcutaneous spinal cord stimulation (tSCS) has been shown to promote recovery from spinal cord injury through enabling effects113. However, its resolution is limited, as it indirectly targets nerve roots via cutaneous input through reflex pathways and primarily aims to increase excitability of entire muscle groups, rather than inducing motion upon stimulation.

Implanted epidural electrical stimulation (EES) targets dorsal roots to optimize fiber recruitment and facilitate natural movement through reflex pathways114, providing not only the enabling111 but also inducing115 effects. The coverage of spinal cord segments is a critical factor of EES. Paddle electrodes, the most commonly used configuration for humans and primates, typically have 8 to 16 contacts and cover 3–5 vertebral segments. These devices can recruit 4–10 motor pools to generate limb movements115,116,117,118,119,120,121. However, the targeting selectivity of EES remains limited to the dorsal root level, restricting the ability to recruit individual muscles. Closed-loop EES successfully generated sensory feedback to prosthetic feet during walking122. Yet, the coarse granularity of electrode-dermatome mapping limited the stimulation specificity.

Intraspinal microstimulation (ISMS), on the other hand, can directly target motoneuron pools via penetrating MEAs and has demonstrated efficacy in generating rhythmic movements such as breathing123 and walking124 through patterned stimulation or pacing with behavioral feedback. Though ISMS benefits from increased stimulation resolution in the spinal cord, it faces certain challenges. ISMS activation of motoneurons pools is not strictly localized, as axonal projections in the ventral horn may also be recruited125. While this fiber recruitment can facilitate generation of muscle synergies that closely mimic natural activation patterns, it may also introduce off-target effects. This reflects a key concern with ISMS that it may “oversimplify” the complex spinal networks126. Specifically, ISMS may not fully engage the interneuronal circuits that coordinate multi-muscle activity, in part due to our limited understanding of the underlying spinal mechanisms127. Continued investigation into spinal network mechanisms is essential for fully leveraging the expanded access to neural populations provided by ISMS. Additionally, ISMS remains highly invasive, presenting substantial translational barriers and significant challenges for multi-site implantation across spinal segments, which is important to achieve comprehensive coverage required for complex motor restoration.

Flexible electrode technology emerges as a promising solution that helps bridge the gap in both coverage and resolution, benefiting both epidural arrays and intraspinal MEAs. Flexible epidural surface arrays have been shown to be capable of motor restoration in animal SCI models by 2-way electrical-chemical modulation128. A flexible epidural circumferential array provides access to both dorsal and ventral regions of the spinal cord, enabling ventral stimulation to recruit site-specific muscle responses while preserving dorsal sensory functions129. It also allows inter-communicating dual-implants that bypass the injury site to enable closed-loop muscle recruitment. Importantly, increasing the electrode count and density of flexible arrays enhances the selectivity of muscle recruitment130 and paves the way for high-dimensional and refined stimulation in SCI treatment. Furthermore, flexible intraspinal polymer MEAs enabled high-quality unit recording in the deep dorsal region131 and elicited movement of the limb132 demonstrating promise in reducing invasiveness and improving tissue integration.

Summary and outlook

In this perspective, we advocate for high-dimensional stimulation as a framework to match the complexity of natural neural codes in BMI applications. Both the motor and sensory systems, which are key targets for BMIs, are inherently high-dimensional, with behaviors and sensory perception arising from distributed, coordinated population activity. Spatially patterned stimulation across many electrodes offers a promising means to modulate these high-dimensional neural states and restore complex functions.

We focus on sensory cortices and the spinal cord, where topographic maps provide a useful scaffold in developing high-dimensional stimulation strategies. Other regions, such as the hippocampus, could also benefit from high-dimensional stimulation, particularly for memory restoration. However, memories are encoded through distributed, non-topographic patterns across the medial temporal lobe, including the hippocampus, which makes targeted stimulation more difficult133. Nevertheless, researchers have shown that a non-linear multi-input, multi-output model of hippocampal CA3-CA1 neuron interactions can restore and even enhance hippocampal memory processing in humans134,135. More recently, stimulation patterns or “content codes” derived from memory decoding models have been shown to significantly modify memory performance in visual memory tasks136.

We identify key technological requirements for high-dimensional stimulation: resolution, coverage, and safety. Although these requirements are yet to be fully realized, we are optimistic that flexible electrode technology will play a transformative role in advancing high-dimensional stimulation for BMI applications. Their exceptional tissue integration, scalability, and capacity for large area, high-density coverage make them well-suited for delivering intricate stimulation patterns to the nervous system. Furthermore, their close proximity to target neurons enables lower stimulation thresholds and enhances both spatial specificity and long-term stability.

We restricted the scope of this perspective to the electrode interface, but we acknowledge that hardware and computational challenges remain. For example, backend electronics must scale accordingly to support the increasing number of electrodes. Current commercial systems can provide up to 1024 channels for microstimulation107. More recently, a custom wireless system integrating 65,536 recording electrodes and 16,384 stimulation channels with a flexible subdural array demonstrated stable chronic performance in vivo, underscoring the feasibility of large-scale electrode-electronics integration137.

However, determining the optimal time and parameters to stimulate each electrode remains a major computational challenge. Traditional trial-and-error methods, in which clinicians manually vary stimulation parameters and query patient percepts or movements, become impractical in high-dimensional stimulation settings. Computational models have therefore become essential tools. Epidural spinal stimulation (EES) has benefited from such models, in part due to the availability of objective outcome measures such as motor-evoked potentials and movement kinematics115,138. In contrast, applying similar modeling frameworks to sensory restoration via ICMS is more challenging, as the goal is to elicit accurate subjective sensations that are unobservable to the clinician and difficult to validate. Biophysically based models attempt to optimize stimulation patterns that reproduce neural activity observed during natural sensory experiences, which is used as a proxy for sensation139. However, such models that optimize for biomimetic stimulation patterns are hindered by high computational costs and technical limitations, such as stimulation artifacts that obscure the evoked neural responses needed for validation. Alternatively, models that attempt to reduce the burden of psychometric tests may be more practical for high-dimensional stimulation contexts. For instance, developing electrode-to-percept maps can be accelerated by exploiting distance-dependent correlations in neuronal signals across electrodes140. Self-guided stimulation paradigms can both speed up psychometric testing and better engage patients141. In addition, neural recordings from higher-order brain areas have shown that detection of electrically induced percepts is associated with specific neural signatures107,142,143. These objective neurometric markers can enable estimation of perceptual detection thresholds at a much higher throughput without requiring continuous patient feedback. Lastly, recalibration strategies will also be necessary to accommodate physiological phenomena like representational drift and device-induced plasticity144.

By addressing these multifaceted challenges and leveraging advancements in high-dimensional stimulation and electrode technologies, we are optimistic that the field will continue to make transformative strides in restoring natural motor, sensory, and cognitive functions, ultimately enhancing the quality of life for individuals with neurological impairments.

Data availability

The data generated and used for Fig. 1 in this manuscript are deposited in the Zenodo archive at https://zenodo.org/records/14880298. Code used for simulation, analysis, and visualization is available on Github (https://github.com/XieLuanLab/high_dimensional_stim_sim).

References

Azevedo, F. A. et al. Equal numbers of neuronal and nonneuronal cells make the human brain an isometrically scaled-up primate brain. J. Comp. Neurol. 513, 532–541 (2009).

Bahney, J. & von Bartheld, C. S. The cellular composition and glia–neuron ratio in the spinal cord of a human and a nonhuman primate: comparison with other species and brain regions. Anat. Rec. 301, 697–710 (2018).

Langdon, C., Genkin, M. & Engel, T. A. A unifying perspective on neural manifolds and circuits for cognition. Nat. Rev. Neurosci. 24, 363–377 (2023).

Churchland, M. M. et al. Neural population dynamics during reaching. Nature 487, 51–56 (2012).

Cunningham, J. P. & Yu, B. M. Dimensionality reduction for large-scale neural recordings. Nat. Neurosci. 17, 1500–1509 (2014).

Lieber, J. D. & Bensmaia, S. J. High-dimensional representation of texture in somatosensory cortex of primates. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 116, 3268–3277 (2019).

Long, K. H., Lieber, J. D. & Bensmaia, S. J. Texture is encoded in precise temporal spiking patterns in primate somatosensory cortex. Nat. Commun. 13, 1311 (2022).

Lehky, S. R., Kiani, R., Esteky, H. & Tanaka, K. Dimensionality of object representations in monkey inferotemporal cortex. Neural Comput. 26, 2135–2162 (2014).

Kodama, A., Kimura, K. & Sakai, K. Dimensionality of the intermediate-level representation of shape and texture in monkey V4. Neural Netw. 153, 444–449 (2022).

Niell, C. M. & Stryker, M. P. Modulation of visual responses by behavioral state in mouse visual cortex. Neuron 65, 472–479 (2010).

O’Shea, D. J. et al. Direct neural perturbations reveal a dynamical mechanism for robust computation. bioRxiv 2022–12 (2022).

Jun, J. J. et al. Fully integrated silicon probes for high-density recording of neural activity. Nature 551, 232–236 (2017).

Chung, J. E. et al. High-density, long-lasting, and multi-region electrophysiological recordings using polymer electrode arrays. Neuron 101, 21–31.e5 (2019).

Sahasrabuddhe, K. et al. The Argo: a high channel count recording system for neural recording in vivo. J. Neural Eng. 18, 015002 (2021).

Zhao, Z. et al. Ultraflexible electrode arrays for months-long high-density electrophysiological mapping of thousands of neurons in rodents. Nat. Biomed. Eng. 7, 520–532 (2023).

Steinmetz, N. A. et al. Neuropixels 2.0: A miniaturized high-density probe for stable, long-term brain recordings. Science 372, eabf4588 (2021).

Trautmann, E. M. et al. Large-scale high-density brain-wide neural recording in nonhuman primates. BioRxiv 2023–02 (2023).

Liu, Y. et al. A high-density 1,024-channel probe for brain-wide recordings in non-human primates. Nat. Neurosci. 27, 1620–1631 (2024).

Flesher, S. N. et al. A brain-computer interface that evokes tactile sensations improves robotic arm control. Science 372, 831–836 (2021).

Simeral, J. D., Kim, S.-P., Black, M. J., Donoghue, J. P. & Hochberg, L. R. Neural control of cursor trajectory and click by a human with tetraplegia 1000 days after implant of an intracortical microelectrode array. J. Neural Eng. 8, 025027 (2011).

Card, N. S. et al. An accurate and rapidly calibrating speech neuroprosthesis. N. Engl. J. Med. 391, 609–618 (2024).

Flesher, S. N. et al. Intracortical microstimulation of human somatosensory cortex. Sci. Transl. Med. 8, 361ra141 (2016).

Hiremath, S. V. et al. Human perception of electrical stimulation on the surface of somatosensory cortex. PLOS ONE 12, e0176020 (2017).

Armenta Salas, M. et al. Proprioceptive and cutaneous sensations in humans elicited by intracortical microstimulation. eLife 7, e32904 (2018).

Araki, T. et al. Flexible neural interfaces for brain implants—the pursuit of thinness and high density. Flex. Print. Electron. 5, 043002 (2020).

Lycke, R. et al. Low-threshold, high-resolution, chronically stable intracortical microstimulation by ultraflexible electrodes. Cell Rep. 42, 112554 (2023).

Orlemann, C. et al. Flexible polymer electrodes for stable prosthetic visual perception in mice. Adv. Healthcare Mater. 13, 2304169 (2024).

Pancrazio, J. J. et al. Thinking small: progress on microscale neurostimulation technology. Neuromodulation Technol. Neural Interface 20, 745–752 (2017).

Li, G. et al. A bimodal closed-loop neuromodulation implant integrated with ultraflexible probes to treat epilepsy. Biosens. Bioelectron. 271, 117071 (2025).

Ye, Y. et al. Flexible bi-directional brain computer interface for controlling turning behavior of mice. In 2023 IEEE 36th Int. Conf. Micro Electro Mech. Syst. MEMS, 33–36 (IEEE, 2023).

Uguz, I. & Shepard, K. L. Spatially controlled, bipolar, cortical stimulation with high-capacitance, mechanically flexible subdural surface microelectrode arrays. Sci. Adv. 8, eabq6354 (2022).

Hettick, M. et al. The Layer 7 Cortical Interface: a scalable and minimally invasive brain–computer interface platform. Preprint at https://www.biorxiv.org/content/10.1101/2022.01.02.474656v2 (2024).

Lee, J. M. et al. The ultra-thin, minimally invasive surface electrode array neuroweb for probing neural activity. Nat. Commun. 14, 7088 (2023).

Viana, D. et al. Nanoporous graphene-based thin-film microelectrodes for in vivo high-resolution neural recording and stimulation. Nat. Nanotechnol. 19, 514–523 (2024).

Potjans, T. C. & Diesmann, M. The cell-type specific cortical microcircuit: relating structure and activity in a full-scale spiking network model. Cereb. Cortex 24, 785–806 (2014).

Graber, S. et al. Nest 3.8 (2024).

Histed, M. H., Bonin, V. & Reid, R. C. Direct activation of sparse, distributed populations of cortical neurons by electrical microstimulation. Neuron 63, 508–522 (2009).

Aberra, A. S., Peterchev, A. V. & Grill, W. M. Biophysically realistic neuron models for simulation of cortical stimulation. J. Neural Eng. 15, 066023 (2018).

Hughes, C. L., Stieger, K. A., Chen, K., Vazquez, A. L. & Kozai, T. D. Spatiotemporal properties of cortical excitatory and inhibitory neuron activation by sustained and bursting electrical microstimulation. iScience 28, 112707 (2024).

Dadarlat, M. C., Sun, Y. J. & Stryker, M. P. Activity-dependent recruitment of inhibition and excitation in the awake mammalian cortex during electrical stimulation. Neuron 112, 821-834.e4 (2023).

Jazayeri, M. & Afraz, A. Navigating the neural space in search of the neural code. Neuron 93, 1003–1014 (2017).

Fifer, M. S. et al. Intracortical somatosensory stimulation to elicit fingertip sensations in an individual with spinal cord injury. Neurology 98, e679–e687 (2021).

Greenspon, C. M. et al. Evoking stable and precise tactile sensations via multi-electrode intracortical microstimulation of the somatosensory cortex. Nat. Biomed. Eng. 9, 935–951 (2024).

Hobbs, T. G. et al. Biomimetic stimulation patterns drive natural artificial touch percepts using intracortical microstimulation in humans. medRxiv 2024–07 (2024).

Valle, G. et al. Tactile edges and motion via patterned microstimulation of the human somatosensory cortex. Science 387, 315–322 (2025).

Ho, C. L. A. et al. Orientation preference maps in microcebus murinus reveal size-invariant design principles in primate visual cortex. Curr. Biol. 31, 733–741.e7 (2021).

Salzman, C. D., Britten, K. H. & Newsome, W. T. Cortical microstimulation influences perceptual judgements of motion direction. Nature 346, 174–177 (1990).

Shannon, R. A model of safe levels for electrical stimulation. IEEE Trans. Biomed. Eng. 39, 424–426 (1992).

McCreery, D., Agnew, W., Yuen, T. & Bullara, L. Charge density and charge per phase as cofactors in neural injury induced by electrical stimulation. IEEE Trans. Biomed. Eng. 37, 996–1001 (1990).

McCreery, D., Yuen, T., Agnew, W. & Bullara, L. Stimulus parameters affecting tissue injury during microstimulation in the cochlear nucleus of the cat. Hearing Res. 77, 105–115 (1994).

Cain, D. P. Kindling in sensory systems: neocortex. Exp. Neurol. 76, 276–283 (1982).

Beauchamp, M. S. et al. Dynamic stimulation of visual cortex produces form vision in sighted and blind humans. Cell 181, 774–783 (2020).

Beauchamp, M. S., Bosking, W. H., Oswalt, D. & Yoshor, D. Raising the stakes for cortical visual prostheses. J. Clin. Investig.131, e154983 (2021).

Roelfsema, P. R. Writing to the mind’s eye of the blind. Cell 181, 758–759 (2020).

Callier, T., Suresh, A. K. & Bensmaia, S. J. Neural coding of contact events in somatosensory cortex. Cereb. Cortex 29, 4613–4627 (2019).

Kirin, S. C. et al. Somatosensation evoked by cortical surface stimulation of the human primary somatosensory cortex. Front. Neurosci. 13, 1019 (2019).

Schmidt, E. M. et al. Feasibility of a visual prosthesis for the blind based on intracortical micro stimulation of the visual cortex. Brain 119, 507–522 (1996).

Houweling, A. R. & Brecht, M. Behavioural report of single neuron stimulation in somatosensory cortex. Nature 451, 65–68 (2008).

Fern´andez, E. et al. Visual percepts evoked with an intracortical 96-channel microelectrode array inserted in human occipital cortex. J. Clin. Investig. 131, e151331 (2021).

Hughes, C. L. et al. Neural stimulation and recording performance in human sensorimotor cortex over 1500 days. J. Neural Eng. 18, 045012 (2021).

Schiavone, G. et al. Guidelines to study and develop soft electrode systems for neural stimulation. Neuron 108, 238–258 (2020).

Kanno, A., Enatsu, R., Ookawa, S., Ochi, S. & Mikuni, N. Location and threshold of electrical cortical stimulation for functional brain mapping. World Neurosurg. 119, e125–e130 (2018).

Stoney, S. D. Jr, Thompson, W. D. & Asanuma, H. Excitation of pyramidal tract cells by intracortical microstimulation: effective extent of stimulating current. J. Neurophysiol. 31, 659–669 (1968).

Kumaravelu, K., Sombeck, J., Miller, L. E., Bensmaia, S. J. & Grill, W. M. Stoney vs. histed: Quantifying the spatial effects of intracortical microstimulation. Brain Stimul. 15, 141–151 (2022).

Murasugi, C., Salzman, C. & Newsome, W. Microstimulation in visual area MT: effects of varying pulse amplitude and frequency. J. Neurosci. 13, 1719–1729 (1993).

Voigt, M. B., Hubka, P. & Kral, A. Intracortical microstimulation differentially activates cortical layers based on stimulation depth. Brain Stimul. 10, 684–694 (2017).

Tanaka, Y. et al. Focal activation of neuronal circuits induced by microstimulation in the visual cortex. J. Neural Eng. 16, 036007 (2019).

Charman, W. N. Visual standards for driving. Ophthalmic Physiol. Opt. 5, 211–220 (1985).

Mai, J. K. & Paxinos, G. The human nervous system (Academic Press, 2011).

Marshel, J. H. et al. Cortical layer–specific critical dynamics triggering perception. Science 365, eaaw5202 (2019).

Chen, X. et al. Chronic stability of a neuroprosthesis comprising multiple adjacent Utah arrays in monkeys. J. Neural Eng. 20, 036039 (2023).

Chung, J. E. et al. Chronic implantation of multiple flexible polymer electrode arrays. J. Vis. Exp. JoVE 10–3791 (2019).

Mercanzini, A. et al. Demonstration of cortical recording using novel flexible polymer neural probes. Sens. Actuators, A 143, 90–96 (2008).

Patel, P. R. et al. Insertion of linear 8.4 µm diameter 16 channel carbon fiber electrode arrays for single unit recordings. J. Neural Eng. 12, 046009 (2015).

Takeuchi, S., Suzuki, T., Mabuchi, K. & Fujita, H. 3D flexible multichannel neural probe array. J. Micromech. Microeng. 14, 104 (2003).

Lo, M. -c. et al. Coating flexible probes with an ultra fast degrading polymer to aid in tissue insertion. Biomed. Microdevices 17, 1–11 (2015).

Zhao, Z. et al. Parallel, minimally-invasive implantation of ultra-flexible neural electrode arrays. J. Neural Eng. 16, 035001 (2019).

Musk, E. et al. An integrated brain-machine interface platform with thousands of channels. J. Med. Internet Res. 21, e16194 (2019).

Urdaneta, M. E. et al. The long-term stability of intracortical microstimulation and the foreign body response are layer dependent. Front. Neurosci. 16, 908858 (2022).

Bradley, D. C. et al. Visuotopic mapping through a multichannel stimulating implant in primate v1. J. Neurophysiol. 93, 1659–1670 (2005).

Rousche, P. & Normann, R. Chronic intracortical microstimulation (ICMS) of cat sensory cortex using the utah intracortical electrode array. IEEE Trans. Rehabil. Eng. 7, 56–68 (1999).

Davis, T. S. et al. Spatial and temporal characteristics of V1 microstimulation during chronic implantation of a microelectrode array in a behaving macaque. J. Neural Eng. 9, 065003 (2012).

Cone, J. J., Ni, A. M., Ghose, K. & Maunsell, J. H. R. Electrical microstimulation of visual cerebral cortex elevates psychophysical detection thresholds. eneuro 5, ENEURO.0311–18.2018 (2018).

Patel, P. R. et al. Utah array characterization and histological analysis of a multi-year implant in non-human primate motor and sensory cortices. J. Neural Eng. 20, 014001 (2023).

Prasad, A. et al. Abiotic-biotic characterization of Pt/Ir microelectrode arrays in chronic implants. Front. Neuroeng. 7, 2 (2014).

Salatino, J. W., Ludwig, K. A., Kozai, T. D. Y. & Purcell, E. K. Glial responses to implanted electrodes in the brain. Nat. Biomed. Eng. 1, 862–877 (2017).

Szymanski, L. J. et al. Neuropathological effects of chronically implanted, intracortical microelectrodes in a tetraplegic patient. J. Neural Eng. 18, 0460b9 (2021).

Woeppel, K. et al. Explant analysis of Utah electrode arrays implanted in human cortex for brain-computer-interfaces. Front. Bioeng. Biotechnol. 9, 759711 (2021).

Bjånes, D. A. et al. Quantifying physical degradation alongside recording and stimulation performance of 980 intracortical microelectrodes chronically implanted in three humans for 956–2246 days. medRxiv (2024).

Xie, C. et al. Three-dimensional macroporous nanoelectronic networks as minimally invasive brain probes. Nat. Mater. 14, 1286–1292 (2015).

Luan, L. et al. Ultraflexible nanoelectronic probes form reliable, glial scar–free neural integration. Sci. Adv. 3, e1601966 (2017).

Potter, K. A., Buck, A. C., Self, W. K. & Capadona, J. R. Stab injury and device implantation within the brain results in inversely multiphasic neuroinflammatory and neurodegenerative responses. J. Neural Eng. 9, 046020 (2012).

Boehler, C., Carli, S., Fadiga, L., Stieglitz, T. & Asplund, M. Tutorial: guidelines for standardized performance tests for electrodes intended for neural interfaces and bioelectronics. Nat. Protoc. 15, 3557–3578 (2020).

Boehler, C., Oberueber, F., Schlabach, S., Stieglitz, T. & Asplund, M. Long-term stable adhesion for conducting polymers in biomedical applications: IrOx and nanostructured platinum solve the chronic challenge. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 9, 189–197 (2017).

Sainburg, R. L., Poizner, H. & Ghez, C. Loss of proprioception produces deficits in interjoint coordination. J. Neurophysiol. 70, 2136–2147 (1993).

Cascio, C. J. Somatosensory processing in neurodevelopmental disorders. J. Neurodev. Disord. 2, 62–69 (2010).

Bensmaia, S. J., Tyler, D. J. & Micera, S. Restoration of sensory information via bionic hands. Nat. Biomed. Eng. 7, 443–455 (2020).

Bensmaia, S. J. Biological and bionic hands: natural neural coding and artificial perception. Philos. Trans. R. Soc. B Biol. Sci. 370, 20140209 (2015).

George, J. A. et al. Biomimetic sensory feedback through peripheral nerve stimulation improves dexterous use of a bionic hand. Sci. Robot. 4, eaax2352 (2019).

Valle, G. et al. Biomimetic intraneural sensory feedback enhances sensation naturalness, tactile sensitivity, and manual dexterity in a bidirectional prosthesis. Neuron 100, 37–45.e7 (2018).

Valle, G. et al. Biomimetic computer-to-brain communication enhancing naturalistic touch sensations via peripheral nerve stimulation. Nat. Commun. 15, 1151 (2024).

Dadarlat, M. C., O’Doherty, J. E. & Sabes, P. N. A learning-based approach to artificial sensory feedback leads to optimal integration. Nat. Neurosci. 18, 138–144 (2015).

Brindley, G. S. & Lewin, W. S. The sensations produced by electrical stimulation of the visual cortex. J. Physiol. 196, 479–493 (1968).

Bak, M. et al. Visual sensations produced by intracortical microstimulation of the human occipital cortex. Med. Biol. Eng. Comput. 28, 257–259 (1990).

Bosking, W. H. et al. Saturation in phosphene size with increasing current levels delivered to human visual cortex. J. Neurosci. 37, 7188–7197 (2017).

Salas, M. A. et al. Sequence of visual cortex stimulation affects phosphene brightness in blind subjects. Brain Stimul. 15, 605–614 (2022).

Chen, X., Wang, F., Fernandez, E. & Roelfsema, P. R. Shape perception via a high-channel-count neuroprosthesis in monkey visual cortex. Science 370, 1191–1196 (2020).

Firszt, J. B., Koch, D. B., Downing, M. & Litvak, L. Current steering creates additional pitch percepts in adult cochlear implant recipients. Otol. Neurotol. 28, 629–636 (2007).

Purves, D. et al. Neuroscience 3rd ed (Oxford University Press, 2012).

Osseward, P. J. II & Pfaff, S. L. Cell type and circuit modules in the spinal cord. Curr. Opin. Neurobiol. 56, 175–184 (2019).

Taccola, G., Sayenko, D., Gad, P., Gerasimenko, Y. & Edgerton, V. R. And yet it moves: recovery of volitional control after spinal cord injury. Prog. Neurobiol. 160, 64–81 (2018).

Sayenko, D. G., Angeli, C., Harkema, S. J., Edgerton, V. R. & Gerasimenko, Y. P. Neuromodulation of evoked muscle potentials induced by epidural spinal-cord stimulation in paralyzed individuals. J. Neurophysiol. 111, 1088–1099 (2014).

Taylor, C. et al. Transcutaneous spinal cord stimulation and motor responses in individuals with spinal cord injury: a methodological review. PLoS One 16, e0260166 (2021).

Hachmann, J. T. et al. Epidural spinal cord stimulation as an intervention for motor recovery after motor complete spinal cord injury. J. Neurophysiol. 126, 1843–1859 (2021).

Lorach, H. et al. Walking naturally after spinal cord injury using a brain–spine interface. Nature 618, 126–133 (2023).

Rowald, A. et al. Activity-dependent spinal cord neuromodulation rapidly restores trunk and leg motor functions after complete paralysis. Nat. Med. 28, 260–271 (2022).

Capogrosso, M. et al. A brain–spine interface alleviating gait deficits after spinal cord injury in primates. Nature 539, 284–288 (2016).

Formento, E. et al. Electrical spinal cord stimulation must preserve proprioception to enable locomotion in humans with spinal cord injury. Nat. Neurosci. 21, 1728–1741 (2018).

Gill, M. L. et al. Neuromodulation of lumbosacral spinal networks enables independent stepping after complete paraplegia. Nat. Med. 24, 1677–1682 (2018).

Wagner, F. B. et al. Targeted neurotechnology restores walking in humans with spinal cord injury. Nature 563, 65–71 (2018).

Barra, B. et al. Epidural electrical stimulation of the cervical dorsal roots restores voluntary upper limb control in paralyzed monkeys. Nat. Neurosci. 25, 924–934 (2022).

Nanivadekar, A. C. et al. Restoration of sensory feedback from the foot and reduction of phantom limb pain via closed-loop spinal cord stimulation. Nat. Biomed. Eng. 8, 1–12 (2023).

Sunshine, M. D., Ganji, C. N., Reier, P. J., Fuller, D. D. & Moritz, C. T. Intraspinal microstimulation for respiratory muscle activation. Exp. Neurol. 302, 93–103 (2018).

Holinski, B. J., Mazurek, K. A., Everaert, D. G., Stein, R. B. & Mushahwar, V. K. Restoring stepping after spinal cord injury using intraspinal microstimulation and novel control strategies. In 2011 Annu. Int. Conf. IEEE Eng. Med. Biol. Soc., 5798–5801 (IEEE, 2011).

Mushahwar, V. K., Jacobs, P. L., Normann, R. A., Triolo, R. J. & Kleitman, N. New functional electrical stimulation approaches to standing and walking. J. Neural Eng. 4, S181 (2007).

Saigal, R., Renzi, C. & Mushahwar, V. K. Intraspinal microstimulation generates functional movements after spinal-cord injury. IEEE Trans. Neural Syst. Rehabil. Eng. 12, 430–440 (2004).

Loeb, G. E. Learning from the spinal cord. J. Physiol. 533, 111–117 (2001).

Minev, I. R. et al. Electronic dura mater for long-term multimodal neural interfaces. Science 347, 159–163 (2015).

Woodington, B. J. et al. Flexible circumferential bioelectronics to enable 360-degree recording and stimulation of the spinal cord. Sci. Adv. 10, eadl1230 (2024).

Russman, S. M. et al. The conformal, high-density spinewrap microelectrode array for focal stimulation and selective muscle recruitment. Adv. Funct. Mater. 2420488.

Wu, Y. et al. Ultraflexible electrodes for recording neural activity in the mouse spinal cord during motor behavior. Cell Rep. 43, 114199 (2024).

Highlights, CNET. Watch Neuralink’s spinal implant stimulate movement in pig. Video on YouTube (2022).

Quiroga, R. Q. Concept cells: the building blocks of declarative memory functions. Nat. Rev. Neurosci. 13, 587–597 (2012).

Berger, T. W. et al. A cortical neural prosthesis for restoring and enhancing memory. J. Neural Eng. 8, 046017 (2011).

Hampson, R. E. et al. Developing a hippocampal neural prosthetic to facilitate human memory encoding and recall. J. Neural Eng. 15, 036014 (2018).

Roeder, B. M. et al. Developing a hippocampal neural prosthetic to facilitate human memory encoding and recall of stimulus features and categories. Front. Comput. Neurosc. 18, 1263311 (2024).

Jung, T. et al. Stable, chronic in-vivo recordings from a fully wireless subdural-contained 65,536-electrode brain-computer interface device (2024).

Capogrosso, M. et al. A computational model for epidural electrical stimulation of spinal sensorimotor circuits. J. Neurosci. 33, 19326–19340 (2013).

Kumaravelu, K. et al. A comprehensive model-based framework for optimal design of biomimetic patterns of electrical stimulation for prosthetic sensation. J. Neural Eng. 17, 046045 (2020).

Lozano, A. et al. Large-scale RF mapping without visual input for neuroprostheses in macaque & human visual cortex. medRxiv 2024–12 (2024).

Verbaarschot, C. et al. Conveying tactile object characteristics through customized intracortical microstimulation of the human somatosensory cortex. Nat. Commun. 16, 4017 (2025).

Van Vugt, B. et al. The threshold for conscious report: Signal loss and response bias in visual and frontal cortex. Science 360, 537–542 (2018).

Beauchamp, M. S., Sun, P., Baum, S. H., Tolias, A. S. & Yoshor, D. Electrocorticography links human temporoparietal junction to visual perception. Nat. Neurosci. 15, 957–959 (2012).

Bonizzato, M. et al. Autonomous optimization of neuroprosthetic stimulation parameters that drive the motor cortex and spinal cord outputs in rats and monkeys. Cell Rep. Med. 4, 101008 (2023).

Tybrandt, K. et al. High-density stretchable electrode grids for chronic neural recording. Adv. Mater. 30, 1706520 (2018).

Kelly, R. C. et al. Comparison of recordings from microelectrode arrays and single electrodes in the visual cortex. J. Neurosci. 27, 261–264 (2007).

Tehovnik, E. J. Electrical stimulation of neural tissue to evoke behavioral responses. J. Neurosci. Meth. 65, 1–17 (1996).

Miocinovic, S. et al. Computational analysis of subthalamic nucleus and lenticular fasciculus activation during therapeutic deep brain stimulation. J. Neurophysiol. 96, 1569–1580 (2006).

McIntyre, C. C. & Anderson, R. W. Deep brain stimulation mechanisms: The control of network activity via neurochemistry modulation. J. Neurochem. 139, 338–345 (2016).

Koeglsperger, T., Palleis, C., Hell, F., Mehrkens, J. H. & B¨otzel, K. Deep brain stimulation programming for movement disorders: Current concepts and evidence-based strategies. Front. Neurol. 10, 410 (2019).

Kim, D., Seo, H., Kim, H.-I. & Jun, S. C. Computational study on subdural cortical stimulation- the influence of the head geometry, anisotropic conductivity, and electrode configuration. PLoS ONE 9, e108028 (2014).

Callier, T. et al. Long-term stability of sensitivity to intracortical microstimulation of somatosensory cortex. J. Neural Eng. 12, 056010 (2015).

Ferroni, C. G., Maranesi, M., Livi, A., Lanzilotto, M. & Bonini, L. Comparative performance of linear multielectrode probes and single-tip electrodes for intracortical microstimulation and single-neuron recording in macaque monkey. Front. Syst. Neurosci. 11, 84 (2017).

Ni, A. M. & Maunsell, J. H. Microstimulation reveals limits in detecting different signals from a local cortical region. Curr. Biol. 20, 824–828 (2010).

Sombeck, J. T. & Miller, L. E. Short reaction times in response to multi-electrode intracortical microstimulation may provide a basis for rapid movement-related feedback. J. Neural Eng. 17, 016013 (2020).

Smith, T. J. et al. Behavioral paradigm for the evaluation of stimulation-evoked somatosensory perception thresholds in rats. Front. Neurosci. 17, 1202258 (2023).

Das, A. Plasticity in adult sensory cortex: a review. Netw. Comput. Neural Syst. 8, R33–R76 (1997).

van der Grinten, M. et al. Towards biologically plausible phosphene simulation for the differentiable optimization of visual cortical prostheses. Elife 13, e85812 (2024).

Acknowledgements

This work was funded by R01EY036094 (L.L); R01NS102917 (C.X); U01NS115588 (C.X); and U01NS131086 (C.X & L.L.).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Initial conception: L.L., C.X. Simulation and data analysis: R.K., J.Z. Original draft writing: R.K., Y.L., J.Z., C.X., L.L. Figures—R.K., Y.L., J.Z. Original draft reviewed and edited by: R.K., Y.L., J.Z., C.X., L.L. Funding: L.L., C.X.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

L.L. and C.X. hold equity ownership in Neuralthread, Inc., an entity that commercializes flexible electrode technology discussed herein. No other authors have financial conflicts.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Kim, R., Liu, Y., Zhang, J. et al. Towards precise synthetic neural codes: high-dimensional stimulation with flexible electrodes. npj Flex Electron 9, 68 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41528-025-00447-y

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41528-025-00447-y