Abstract

Long-term epidermal monitoring with wearable electronics is often hindered on hairy skin due to hair regrowth, which disrupts the skin-device interface and can damage the device. Here, we introduce a high-precision microfiber epidermal thermometer (MET) designed for deformation-insensitive, durable, reliable performance on hairy skin. MET utilizes a stretchable fiber (~340 µm diameter), smaller than average hair follicle spacing, enabling conformal contact without interference from growing hair. Localized nanofiber reinforcement on a microfiber and temperature-sensing layer on localized region create a strain-engineered architecture, allowing MET to achieve strain-insensitive temperature detection. MET demonstrates stable operation under repeated strains (up to 55%) and delivers exceptional precision, with a temperature resolution of 0.01 °C, even during body movements. It accurately tracks physiological temperature fluctuations and provides consistent measurements over 26 days of continuous wear, remaining unaffected by hair regrowth or motion. These results highlight MET as a robust platform for long-term temperature monitoring on hairy skin.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Wearable electronics have garnered significant attention for their integration onto human skin, enabling real-time monitoring for diverse applications such as healthcare1,2,3, biomechanics4,5,6, sports coaching2,7,8, and human-machine interfaces9,10,11,12. These devices are specifically engineered to be flexible and deformable, allowing them to conform to the complex, uneven surfaces of skin while continuously tracking temperature13,14,15, physiological signals16,17, and environmental changes18,19. Despite their promising potential, achieving reliable long-term performance remains a major challenge, particularly when these devices are applied to hairy skin20,21,22 or subjected to dynamic body movements18,23. Hairy skin presents unique obstacles for wearable electronics: human body hair grows at an average rate of approximately 0.3 mm per day24, which disturbs the skin-device interface21,25,26,27, leading to inaccurate measurements, signal instability, and eventual device detachment20,22,28. Furthermore, the natural stretching and movement of the skin during daily activities exacerbate these issues by causing deformation-induced signal noise and motion artifacts. Overcoming these challenges requests innovative approaches that can mitigate interference by growing hair and maintain the same skin-device contact during daily body motions.

Various strategies have been explored to address these challenges on hairy skin, with partial success. Methods employing spray-on tattoos20,25,29, soft polymer electrodes30,31, paste electrodes20, viscoelastic dry electrodes32, and conductive biogels29 have demonstrated improved skin contact. However, these approaches are often limited by large skin-electrode impedance, susceptibility to motion artifacts, and poor long-term stability due to dehydration or residue buildup20,29,30,31,32. While porous substrate-based wearables somewhat alleviated hair interference, they remain vulnerable to hair regrowth over time32,33. Strain-engineered substrates that combine rigid and soft regions34,35,36,37,38,39, drawing inspiration from the stress-strain behavior of biological tissues, have been proposed to reduce signal artifacts caused by body movement40,41, but are less effective in addressing the hair-related challenges. Advanced structural designs - such as wrinkles42, kirigami43,44,45, and serpentine patterns46- have improved the conformability and stability of wearable electronics, yet have not fully resolved the unique issues associated with hairy skin. These designs often require large surface area, which can lead to additional problems such as sweat accumulation, reduced breathability, skin irritation, and overall user discomfort. On hairy skin, these complications are further exacerbated, as the device is prone to delamination or damage from growing hair.

To achieve durable performance under dynamic conditions on hairy skin, it is essential to develop thin, lightweight, deformation-insensitive, and comfortable device architectures. Microfiber (MF)-based wearable electronics present a promising structural approach to these challenges47,48,49. Their small lateral dimensions enable superior conformability to the skin’s uneven morphology, reduce air gaps, maintain close contact even during sweating, and minimize irritation and discomfort. MF-based devices have demonstrated suitability for a range of wearable applications, including electrophysiological sensing50, pressure sensing51, cardio-respiratory monitoring52, and temperature detection53. Nevertheless, their application on hairy skin remains largely unexplored. While some MF-based devices have utilized the structural geometries (buckled54,55, wrinkled56,57, or serpentine58,59) and successfully reduced the motion-induced signal noise, these designs often fall short in achieving mechanical durability and consistent performance on irregular or hairy skin surfaces. Although strain-engineered stretchable MF-based temperature sensors have been reported36,57,60,61, none have demonstrated high-precision detection while maintaining deformation insensitivity under dynamic physiological conditions and ongoing hair growth.

In this study, we solve these limitations by introducing a microfiber epidermal thermometer (MET) designed for high-precision, long-term use during daily life activities. The MET is fabricated through a combination of wet spinning and electrospinning to produce microfibers (MFs) with diameters smaller than the average spacing between human hair follicles, thereby eliminating interference from existing and growing hair. The device features a strain-engineered stretchable MF substrate with a localized tough region, as well as a temperature-sensitive conductive coating layer applied onto the localized tough region. This multilayered architecture imparts strain insensitivity to the sensor, enabling extraordinarily high-precision temperature measurements (temperature resolution ≤ 0.01 °C) without signal disturbance from body motion or hair growth, even during continuous wear for one month.

Results and discussion

Structure and fabrication of the microfiber (MF) thermometer

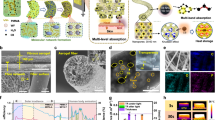

Figure 1a illustrates the dimensional design of the MF. The MF was engineered with an overall diameter of 340 µm, which is smaller than the average follicular spacing of human hair. This design choice enhances the device’s conformability to the skin for long-term use by minimizing interference with existing or growing hair. Figure 1b depicts the structure of the deformation-insensitive MF. The core was made of a soft stretchable polyurethane (PU) MF fabricated via wet spinning. The central region of the PU MF was reinforced with aligned poly(ε-caprolactone) (PCL) nanofibers (NFs), which were wrapped around the MF in alignment with its longitudinal axis. Then, the entire PU MF was encapsulated with soft polydimethylsiloxane (PDMS) by dip-coating, protecting the MF from damage and establishing a robust interface between the PCL NF layer and the PU MF core. Details of the fabrication process are provided in Fig. S1.

a Scheme showing the integration of the MF onto hairy human skin, demonstrating its conformability and alignment between hair follicles. The MF diameter (~340 µm) is smaller than typical follicular spacing, minimizing interference with hair. b Structural illustration of the MF, composed of a stretchable PU core locally reinforced with PCL NFs, and encapsulated with a soft PDMS coating. c Cross-sectional FE-SEM image of the MF, highlighting the embedded PCL NFs within the PDMS and its integration with the PU core. d Optical images showing the MF conformally mounted on porcine skin, where follicular spacing (800–1000 µm) accommodates the MFs without disrupting hair alignment.

Cytotoxicity tests, presented in Fig. S2, evaluate the biocompatibility of the constituent materials (PDMS, PU, and PCL) in the MF over 7 days by exposing to fibroblast cells in vitro. Live/dead fluorescence assays, visualized through confocal microscopy (Fig. S2a), showed live/viable cells fluorescing green and dead/non-viable cells fluorescing red. Quantitative analysis (Fig. S2b) indicates that approximately 98% of cells remained viable through 3, 5, 7 days. All materials exhibit excellent biocompatibility, as evidenced by sustained cell viability across the testing period. These results confirm the non-cytotoxic nature of the MF, supporting its safe application for direct contact with human skin.

The cross-sectional field-emission scanning electron microscopy (FE-SEM) image (Fig. 1c) shows the PU MF core, centrally wrapped with the aligned PCL NFs and encapsulated within a PDMS layer. This directional alignment of the PCL NFs provides mechanical reinforcement to the MF core, restricting deformation under external strain while allowing the remaining regions to retain stretchability. To address this point, Fig. S3 shows finite element analysis (FEA) results under 50% strain. The NF-wrapped central zone exhibits minimal deformation, while the adjacent NF-free regions undergo significant stretching, confirming the strain-isolation effect of the aligned PCL NFs. Supporting this, Fig. S4 and Supplementary Video SV1 present optical observation during 0 ~ 60% stretching, clearly illustrating that the NF-free zones maintain stretchability, whereas the NF-wrapped zone constrains deformation.

The conformability of the MF on both porcine and human skin is demonstrated in Fig. 1d and Fig. S5a. On porcine skin, the MF accommodated the natural follicular spacing (>400 µm) without disrupting hair alignment, as shown in the magnified view. Similarly, Fig. S5b illustrates the integration of the MF on human skin across different populations61,62,63,64,65, and Fig. S5c shows its deployment as bands, rings, or free-standing MFs.

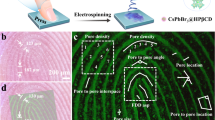

Figure 2a displays the schematic design of the microfiber epidermal thermometer (MET), accompanied by high-resolution SEM images captured at corresponding stages of fabrication. A graphene oxide (GO)/PU temperature sensing layer was coated by dip-coating on the NF-wrapped localized region and dried at 55 °C. The SEM image highlights the regions where the GO/PU sensing layer (40 μm) were uniformly coated on the MF (see also Fig. S6). For electrical interfacing, Ti (5 nm) and Au (50 nm) were sequentially deposited onto the ends of the GO/PU sensing layer by using e-beam evaporation through a soft mask (see the SEM image). Metal deposition was performed twice, once on the upper surface and again on the lower surface after inverting the MF. Copper wires were then connected to the Ti/Au electrodes to complete the device assembly. The total length of the MF (LMF) was 3 cm or longer, and the NF-reinforced localized region (sensing region, Ls) was 2 cm. The optimal conditions for MET structural design is discussed in the next section.

a Scheme of the MET fabrication process. A soft PU MF (total length, LMF = 3 cm) was selectively coated with a temperature-sensitive GO/PU composite on the NF zone (LS = 2 cm), followed by thermal reduction and sequential Ti (5 nm)/Au (50 nm) electrode deposition on both sides via e-beam evaporation. Cross-sectional FE-SEM images exhibit the GO/PU composite layer and the Ti/Au electrode. b Durability test showing stable current response (ΔI/I0) over 10,000 stretching cycles at 30% strain. c Temperature sensing of the MET under various applied strains (0%, 35%,55%).

The fabrication process of the MET comprises sequential steps that are largely scalable. PU MF are produced by wet spinning, and PCL NFs by electrospinning, both industry-compatible techniques. Although NF wrapping on the PU MF is currently manual, it is a mechanically simple step that can be automated using rotational winding systems. Subsequent PDMS dip-coating, selective GO/PU deposition, and low-temperature thermal reduction at 55 °C are all scalable processes. While Ti/Au electrodes were deposited by evaporation for precision, this step can be replaced by screen printing or roll-to-roll methods. Overall, the process supports adaptation for large-scale and textile-integrated production with minimal modifications (Note S1).

Strain neutrality of the MET

The sensor demonstrated outstanding strain insensitivity, exhibiting negligible changes in relative current (ΔI/I₀) under uniaxial strains (ε) up to 60% (Fig. S7). Even after 10,000 stretching cycles at ε = 30% which is a level representative of typical strains experienced by human skin, no discernible change in current was observed (Fig. 2b). Across the wide temperature range of 25–60 °C, the thermometer maintained excellent linearity between ΔI/I₀ and temperature, with no interference from external strain at any tested level (ε = 0–55%) (Fig. 2c), potentially enabling the MET to more reliably reflect core body temperature changes, such as hypothermia (<35 °C) and fever (>38 °C), which is in contrast to conventional skin-mounted thermometers which often suffer from motion artifacts and limited skin conformity. This linearity enabled direct conversion of ΔI/I₀ to absolute temperature, independent of mechanical deformation. Notably, this strain neutrality was also achieved with a shorter localized zone (Ls = 1 cm) (Fig. S8). The remarkable strain insensitivity observed in this study is attributed to the high deformability (ε ≥ 600%) and low Young’s modulus (~0.5 MPa) of the MF (Fig. S9).

Both the Ti/Au electrode and its interfaces with the GO/PU layer, as well as the metal wire connections, can potentially be influenced by external mechanical stimuli. To ensure stable electrical contact between the metal wire and the Ti/Au layer, liquid metal was employed as the interfacial material. We further examined the influence of the Ti/Au electrode area and its positioning on the GO/PU layer (Fig. S10). While the electrode area had minimal impact on strain neutrality, confining the Ti/Au coating to the two ends of the GO/PU layer provided optimal strain-insensitive performance, with no variation observed under external mechanical stimuli.

Achievement of extraordinary high precision in temperature sensing

The temperature sensing mechanism of the MET is governed by the temperature-dependent conductivity of the GO/PU composite. At elevated temperatures, thermal excitation increased charge carrier mobility, thereby enhancing both tunneling and hopping transport across the GO/PU–polymer interfaces. Figure 3a demonstrates the extraordinarily high precision of temperature measurement achieved by the deformable MET. The device’s signal (ΔI/I₀) was recorded within a narrow temperature interval (36.5–36.8 °C), with incremental steps of 0.1 °C. The plot includes visible error bars, indicating minimal variation across repeated measurements, with a maximum standard deviation of less than 0.5% (0.03 µA). Based on these results, the sensor achieved a maximum temperature resolution of 0.01 °C, outperforming previously reported resolutions (typically ~0.5 °C) for deformable thermometers56,62,63,64, by more than an order of magnitude. For comparison, our previous work reported a wearable thermometer with a best temperature resolution of 0.2 °C65.

a High-resolution thermal sweep (36.5–36.8 °C) showing a linear increase in output current (I) with small incremental change (0.1 °C). b Time-dependent temperature response of the MET under dynamic thermal situation, upon heating (red-shaded region) followed by cooling (blue-shaded region). c Temperature stability of the MET sensor at three different skin positions (Position 1: back of hand, Position 2: forearm, Position 3: upper arm) over 60 s. d Temperature response of the MET sensor during continuous finger movement over 200 s, demonstrating stable temperature measurements (~33 °C) without motion-induced artifacts.

To further evaluate the sensor’s response to dynamic temperature changes, the MET was mounted on a cylindrical metal bar and subjected to controlled thermal stimuli (Fig. 3b). Upon immersion in hot water (~60 °C; red-shaded region), the temperature of the metal bar increased gradually over 200 s, reaching approximately 60 °C. Subsequent immersion in ice water (~6 °C; blue-shaded region) led to a rapid temperature decrease over ~100 s, followed by a slower approach to equilibrium at ~3 °C. Throughout these dynamic transitions, the MET provided stable and precise temperature readings. Notably, a slight decrease in temperature was observed before immersion in hot water (80–95 s in Fig. 3b), despite the system appearing stable at room temperature. This transient drop is attributed to localized convective heat loss from the exposed metal surface to the ambient air, which may have been slightly cooler than the bar due to prior handling or thermal lag. The high thermal conductivity of the metal bar also rendered it highly responsive to minor environmental changes, such as airflow from ventilation or air conditioning, resulting in a rapid but subtle decrease in surface temperature. The MET’s ability to detect these minute thermal fluctuations highlights its high sensitivity and rapid response, key attributes for accurate temperature monitoring in dynamically changing, real-world environments.

To validate reliable epidermal temperature monitoring on hairy skin, we compared body temperature measurements from three different sites on a hairy forearm (Fig. 3c). All three locations yielded consistent readings (~34 °C), with minor variations reflecting natural differences in skin temperature across body regions, thereby confirming the sensor’s effective conformal contact on hairy skin. Figure 3d further illustrates the MET’s performance when mounted on a finger during repeated flexion and extension; the measured temperature remained constant, with no evidence of motion-induced artifacts. Additional temperature monitoring from three anatomical locations, the wrist, dorsum of the hand, and palm, is presented in Fig. S11. All the three locations had the same temperature regardless of the motions.

Long-term practical use of the MET

To evaluate the long-term reliability of the MET, assessments were performed under real-life conditions, including body movements, thermal stimuli, and extended use on hairy skin. Figure 4a presents the real-time response of the MET during exercise. A male subject in his early 30 s performed repetitive pressing and releasing actions by using a hand grip strengthener for 100 s. Throughout the exercise, the recorded skin temperature remained steady at approximately 30.6 °C. Following the cessation of exercise, the skin temperature gradually increased, reaching a peak of ~32.9 °C within 270 s and decreasing to ~31.0 °C. The high-precision temperature measurements enabled detection of subtle physiological thermal changes associated with blood circulation and post-exercise recovery. The delayed peak in skin temperature following exercise reflects established thermoregulatory processes. During exercise, metabolic heat accumulates in the core due to muscle activity, while cutaneous vasoconstriction restricts immediate heat transfer to the skin. After exercise cessation, vasodilation enhances peripheral blood flow, gradually transferring stored heat to the skin surface, causing a post-exercise temperature rise. This thermal lag is well-documented and arises from circulatory dynamics and thermal inertia. Therefore, the observed trend in this study properly represents the physiological behavior, and the current measurement protocol effectively captures this thermal response66,67,68,69. Notably, the post-exercise temperature measured by the MET matched the forearm temperature (32.9 °C) obtained by using an infrared thermometer after the temperature rise phase (Fig. 4b). Additionally, repeated trials comparing MET and infrared thermometer measurements before and after exercise were conducted, and the results presented in Figs. S12 and S13 further validate the temperature accuracy of the MET.

a Real-time temperature response of the MET during mild exercise, showing a stable ΔI/I0 signal during movement (~100–200 s) and a gradual increase of temperature after the exercise. b Infrared thermal image of the forearm during the temperature increase after exercise, confirming surface body temperature (~32.9 °C). c Dynamic thermal stimulation test showing the MET response upon contact with a hot object, followed by a cold object. d Long-term monitoring of the same skin site during consecutive 26 days. e Optical images of the sensor site corresponding to (d), showing progressive hair regrowth while maintaining full conformal attachment of the MET without delamination (Day 0, 9, and 26).

Figure 4c demonstrates the MET’s real-time response to abrupt external thermal stimuli. The sensor was placed on a glass slide, and plastic tubes filled with hot (~45 °C) and cold (~0 °C) water were sequentially brought into contact with the sensor. The baseline temperature was initially ~25 °C. Upon contact with the hot object, the sensor temperature increased within 10 s and returned to the baseline after the object was removed. Subsequent exposure to the cold object resulted in a sharp temperature drop, which then returned again to baseline upon removal.

Figure 4d highlights the long-term stability of the MET when worn on the forearm for 26 consecutive days. The forearm was shaved on Day 0 and left unshaved for the duration of the study (Fig. 4e). Throughout the 26-day period, the sensor consistently provided stable temperature readings (~33.5 °C). Despite the progressive increase in hair length and density, the MET maintained excellent conformal contact with the skin, demonstrating outstanding long-term signal fidelity on hairy skin. Additionally, the extended set of optical images presented in Fig. S13, including those of shaved skin and images from Days 0, 9, 16, and 26, was compiled to monitor skin condition throughout the study. No visible signs of redness, irritation, or other adverse skin reactions were observed at the MET application site during the entire 26-day period, confirming excellent skin compatibility (see Fig. S14).

In addition to hairy skin compatibility and motion resilience, the long-term wearability of the MET was further evaluated under realistic environmental skin conditions. Three samples were fabricated using the same procedure described in the ‘Methods’ section and tested on the same human subject under oily, sweaty, and humid conditions. These conditions were selected to simulate realistic environmental challenges for skin-interfaced devices. The oily condition involved application on lotion-treated skin, the sweaty condition followed natural perspiration during routine activity, and the humid condition involved storing the sample at 60% RH before reapplication on Day 4. As shown in Fig. S15, all temperature-time curves on Day 1 and Day 4 remained closely overlapped around ~33 °C, with a slight decrease in the sweaty condition (~32.5 °C) due to evaporative cooling. This result confirms the MET’s thermal sensitivity and strong environmental robustness, supporting its reliability for long-term skin-mounted applications.

Beyond temperature sensing, the MET platform may offer potential for future multifunctional integration. By reconfiguring the NF-reinforcement strategy and tuning the sensing materials, the same MF framework can be adapted to monitor additional physiological signals such as strain, ECG, EEG, or hydration. For example, adjusting the amount of the NF-loading can allow strain-responsive behavior, Replacing the GO/PU coating with low-impedance, biocompatible conducting layer like PEDOT:PSS70 or silver nanowires (AgNWs)71 is expected to enable high-fidelity electrophysiological signal acquisition. Hydration sensing can also be realized by integrating humidity-sensitive materials such as GO72 or polyaniline73. These modifications highlight the extensibility of the MET architecture for comprehensive multimodal wearable sensing system (see Note S2).

Discussion

We have developed a strain-engineered microfiber epidermal thermometer (MET) featuring a stretchable PU core, a nanofiber-reinforced localized coating, a GO/PU temperature-sensing composite coating on the localized region, and Ti/Au electrodes at both ends of the sensing layer, and liquid metal-assisted signal wiring. This multilayer MF architecture allowed deformation-insensitive, extraordinary high-precision temperature sensing. The MET exhibited a linear response between relative current and temperature, with outstanding temperature resolution as fine as 0.01 °C. It showed excellent mechanical durability, maintaining stable performance under repeated large strains (ε = 55%). The MET responded rapidly to abrupt thermal changes and accurately tracked physiological temperature variations during exercise and daily activities. Long-term trials further confirmed its stable operation and signal fidelity, even when worn on hairy skin over 26 consecutive days. Collectively, these results underscore the robust, deformation-insensitive, and biologically adaptive performance of the MET, positioning it as a promising candidate for next-generation wearable health monitoring systems.

Methods

Materials

Polycaprolactone (PCL) pellets (Mw ≈80,000, Sigma Aldrich) were dissolved in a chloroform/methanol mixture (8:2 (V/V), Sigma Aldrich) to prepare the electrospinning solution for nanofiber (NF) fabrication using an electrospinning system (ESR 200, Nano NC). For polyurethane (PU) microfiber (MF) fabrication via wet spinning, PU granules (SG 85A, Tecoflex) were dissolved in a 1:1 mixture of dimethylformamide (DMF, Sigma Aldrich) and acetone (Sigma Aldrich) at 80 °C under continuous stirring for 3 h. Polydimethylsiloxane (PDMS; Sylgard 184, Dow Corning) was prepared by mixing the base and curing agent at a 10:1 weight ratio. Graphene oxide (GO) nanosheets, synthesized by the Hummers’ method, were dispersed in dimethylacetamide (DMAC, Sigma Aldrich) and blended with PU to form a temperature-sensitive GO/PU nanocomposite layer. PU granules were first dissolved in DMAC at 80 °C for 1 h under stirring, followed by dropwise addition of GO to ensure homogeneous dispersion. Temperature sensor electrodes were fabricated by sequentially depositing a 5 nm titanium (Ti) adhesion layer and a 50 nm gold (Au) conductive layer onto the MF’s NF zone using e-beam evaporation (KVE-ET, Korea Vacuum Tech).

Microfiber fabrication

A DMF/acetone mixture (1:1, V/V) was used as the solvent for wet spinning of PU at a concentration of 30 wt% to prepare the spinning dope. The solution was injected through a 23 G needle into a deionized (DI) water coagulation bath at a flow rate of 1 mL h−¹. The resulting MF was left in DI water for 24 h for complete coagulation, then air-dried for 8 h. The total length of the PU MF was set to 4 cm, with 3 cm designated as the working section. PCL NFs were electrospun from a 10 wt% PCL solution in chloroform/methanol (8:2 v/v) onto a grounded aluminum foil collector (20 cm × 20 cm) under 13.5 kV, at a flow rate of 0.7 mL h−1, and a 15 cm needle-to-collector distance. After electrospinning, the NF mats were air-dried to remove residual solvent, then cut into 1 cm × 1 cm and 2 cm × 1 cm pieces and wrapped around the central region of the PU MF to create two sample variations. The NF-wrapped MF was dip-coated in PDMS, suspended to remove excess, and cured at 55 °C for 8 h. The final MF, with a diameter of ~340 µm, was obtained by controlling the PDMS dipping time to 1 min.

Cytotoxicity evaluation of PCL, PU, and PDMS

The biocompatibility of PCL, PU, and PDMS was assessed over seven days. Each material was cast into well plates and cured for 8 h to form uniform layers before cell seeding. Mouse embryonic fibroblast cells (NIH3T3, Korean Cell Line Bank) were cultured on the material surfaces in high-glucose Dulbecco’s modified Eagle medium (DMEM, Gibco) supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS, Gibco) and 5% penicillin/streptomycin at 37 °C with 5% CO₂. Live/dead fluorescence assays were conducted on days 3, 5, and 7 to monitor cell viability, with imaging performed using a confocal microscope (Fluoview 3000, Olympus). The fraction of dead cells was quantified by measuring the fluorescence intensity ratio of dead (red) to total cells using ImageJ software.

Deposition and measurement of stretchable Ti/Au electrodes

A 5 nm Ti adhesion layer followed by a 50 nm Au conductive layer was deposited along the full length of the MF using e-beam evaporation to ensure uniform coverage. For static testing, electrical responses under strains of 0–55% were measured using a semiconductor analyzer (Keithley 2450) and an x–y holder (UMP 100, Tera Leader). To prevent damage to the Ti/Au layer, measurements were performed at both NF and NF-free zones. Copper wires were attached to both ends of the designated regions, with EGaIn (eutectic gallium-indium, Sigma Aldrich) facilitating electrical contact. The same protocol was applied to NF-free zones for comparison. Electrode responses during stretching were recorded with the Keithley 2450.

Temperature measurement

To enhance GO/PU composite adsorption, the MF was plasma-treated at 640 mTorr with 100 W microwave power. Uncoated regions were then dip-coated with GO/PU solution and thermally reduced at 55 °C for 30 h to form reduced GO (R-GO). Selective electrode regions were defined by depositing Ti/Au (5 nm/50 nm) onto both sides of the NF zone (length = 2 mm), with the remainder masked. All skin-contact experiments were conducted on a single healthy male (age 30) with informed consent. Textile-based conductive contacts (nickel-coated polyester, GA-1610R, DST) were attached to both ends of the NF zone for reliable connectivity. Sensor responses were evaluated under various conditions: different body sites, stretching, pre- and post-exercise, dynamic movements, contact with hot/cold objects, and mounting on a cylinder. For long-term wearability (26 days), the sensor was encapsulated in PDMS and covered with a water-retentive patch. Current variations were analyzed using a Keithley 2450. For band-form temperature sensing, the PU MF zone was extended and both ends tied to form a wearable band.

Finite element analysis, three-dimensional

A three-dimensional finite element model was developed in ABAQUS to simulate the mechanical behavior of MF under uniaxial stretching. The MF, with a diameter of 460 µm, consists of multiple constituent materials with distinct mechanical properties: PU with an elastic modulus of 0.42 MPa and a Poisson’s ratio of 0.3, PCL NFs with an elastic modulus of 3 MPa and a Poisson’s ratio of 0.36, and PDMS with an elastic modulus of 0.28 MPa and a Poisson’s ratio of 0.4. To accurately capture the deformation behavior of the heterogeneous MF structure, the domain was discretized using 8-node linear hexahedral elements (C3D8). A minimum element size of 5 µm was applied to ensure numerical stability and reliable convergence while maintaining computational efficiency. The element size was selected to be less than one-fifth of the smallest characteristic dimension of the MF, ensuring sufficient resolution for precise stress and strain distribution analysis.

Characterization

Field-emission scanning electron microscopy (FE-SEM, SU6600, Hitachi) was used to characterize NF and MF morphologies. Stress-strain properties were measured with an ultimate tensile tester (E42, MTS System). Optical images of MF and pig hair were obtained with an optical microscope. Electrode responses were measured using a two-probe system (MST8000, Keithley) and a Keithley 4200-SCS semiconductor parameter analyzer. Temperature sensor responses were also recorded with the Keithley 4200-SCS, while dynamic sensing responses were measured with the Keithley 2450. Stretching cycle tests were performed using a UMP 100 (Tera Leader). Ti/Au deposition was conducted with an e-beam evaporator (KVE-ET, Korea Vacuum Tech). Thermal images before and after exercise were captured with a thermal camera (885 Pro, Testo). Precise thermal response measurements were carried out using a Thermal Chemical Vapor Deposition system (TCVD, MTI Corporation).

Data availability

Data is provided within the paper or supplementary information files.

References

Iqbal, S. M. A., Mahgoub, I., Du, E., Leavitt, M. A. & Asghar, W. Advances in healthcare wearable devices. npj Flex. Electron. 5, 1–14 (2021).

Singh, J., Bin, S., Jung, S. & Kim, J. Materials today bio electronic textiles: new age of wearable technology for healthcare and fitness solutions. Mater. Today Bio 19, 100565 (2023).

Ray, T. R. et al. Bio-integrated wearable systems: a comprehensive review. Chem. Rev. 119, 5461–5533 (2019).

Wang, J. et al. Sustainably powering wearable electronics solely by biomechanical energy. Nat. Commun. 7, 1–8 (2016).

Wan, D. et al. Nano energy human body-based self-powered wearable electronics for promoting wound healing driven by biomechanical motions. Nano Energy 89, 106465 (2021).

Li, X. et al. Biomechanical energy harvesting technologies for wearable electronics: theories and devices. Friction 12, 1655–1679 (2024).

Kwon, S., Kwon, Y., Kim, Y., Lim, H. & Mahmood, M. Biosensors and bioelectronics skin-conformal, soft material-enabled bioelectronic system with minimized motion artifacts for reliable health and performance monitoring of athletes. Biosens. Bioelectron. 151, 111981 (2020).

Choudhry, N. A., Arnold, L., Rasheed, A., Khan, I. A. & Wang, L. Textronics: a review of textile-based wearable electronics. Adv. Eng. Mater. 23, 2100469 (2021).

Wu, Z. et al. A wearable ionic hydrogel strain sensor with double cross-linked network for human–machine interface. Adv. Compos. Hybrid. Mater. 8, 1–13 (2025).

Zhang, C. et al. Nature-inspired helical piezoelectric hydrogels for energy harvesting and self-powered human-machine interfaces. Nano Energy 136, 110755 (2025).

Ma, G. et al. Body-coupled multifunctional human–machine interfaces with double spiral electrode structure. Adv. Funct. Mater. 35, 2424979 (2025).

Zarei, M., Lee, G., Lee, S. G. & Cho, K. Advances in biodegradable electronic skin: material progress and recent applications in sensing, robotics, and human–machine interfaces. Adv. Mater. 35, 2203193 (2023).

Lin, Y., Qiu, W. & Kong, D. Stretchable and body-conformable physical sensors for emerging wearable technology. Sens. Diagn. 3, 1442–1455 (2024).

Mazzotta, A., Carlotti, M. & Mattoli, V. Conformable on-skin devices for thermo-electro-tactile stimulation: materials, design, and fabrication. Mater. Adv. 2, 1787–1820 (2021).

Nie, S. et al. Soft, stretchable thermal protective substrates for wearable electronics. npj Flex. Electron. 6, 1–9 (2022).

Jin, H., Abu-Raya, Y. S. & Haick, H. Advanced materials for health monitoring with skin-based wearable devices. Adv. Healthc. Mater. 6, 1700024 (2017).

Wang, X., Liu, Z. & Zhang, T. Flexible sensing electronics for wearable/attachable health monitoring. Small 13, 1602790 (2017).

Ershad, F. et al. Ultra-conformal drawn-on-skin electronics for multifunctional motion artifact-free sensing and point-of-care treatment. Nat. Commun. 11, 1–13 (2020).

Chen, W. et al. Customized surface adhesive and wettability properties of conformal electronic devices. Mater. Horiz. 11, 6289–6325 (2024).

Zhang, R., Wen, S., Zhao, Y. & Ji, S. Water-removable paste electrode for electrophysiological monitoring on hairy skin. ACS Appl. Electron. Mater. 7, 925–932 (2025).

Ershad, F., Patel, S. & Yu, C. Wearable bioelectronics fabricated in situ on skins. npj Flex. Electron. 7, 32 (2023).

Wang, Y. et al. Skin bioelectronics towards long-term, continuous health monitoring. Chem. Soc. Rev. 51, 3759–3793 (2022).

Yin, J., Wang, S., Tat, T. & Chen, J. Motion artefact management for soft bioelectronics. Nat. Rev. Bioeng. 2, 541–558 (2024).

Philpott, M. P., Green, M. R. & Kealey, T. Human hair growth in vitro. J. Cell Sci. 97, 463–471 (1990).

Li, H. et al. E-Tattoos: toward functional but imperceptible interfacing with human skin. Chem. Rev. 124, 3220–3283 (2024).

Liu, Y., Pharr, M. & Salvatore, G. A. Lab-on-skin: a review of flexible and stretchable electronics for wearable health monitoring. ACS Nano 11, 9614–9635 (2017).

Belay, A. N. et al. Biointerface engineering of flexible and wearable electronics. Chem. Commun. 61, 2858–2877 (2025).

Zhang, A. et al. Adhesive wearable sensors for electroencephalography from hairy scalp. Adv. Healthc. Mater. 12, 1–9 (2023).

Wang, C. et al. On-skin paintable biogel for long-term high-fidelity electroencephalogram recording. Sci. Adv. 8, 1–11 (2022).

Li, T. et al. Robust skin-integrated conductive biogel for high-fidelity detection under mechanical stress. Nat. Commun. 16, 88 (2025).

Stauffer, F. et al. Skin conformal polymer electrodes for clinical ECG and EEG recordings. Adv. Healthc. Mater. 7, 1700994 (2018).

Tian, Q. et al. Hairy-skin-adaptive viscoelastic dry electrodes for long-term electrophysiological monitoring. Adv. Mater. 35, 2211236 (2023).

Tian, Q. et al. Ultrapermeable and wet-adhesive monolayer porous film for stretchable epidermal electrode. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 14, 52535–52543 (2022).

Cho, H. et al. Recent progress in strain-engineered elastic platforms for stretchable thin-film devices. Mater. Horiz. 9, 2053–2075 (2022).

Hou, S. et al. Stretchable electronics with strain-resistive performance. Small 20, 2306749 (2024).

Wang, W. et al. Strain-insensitive intrinsically stretchable transistors and circuits. Nat. Electron. 4, 143–150 (2021).

Cai, M., Nie, S., Du, Y., Wang, C. & Song, J. Soft elastomers with programmable stiffness as strain-isolating substrates for stretchable electronics. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 11, 14340–14346 (2019).

Zhang, L. et al. Strain-insensitive stretchable triboelectric tactile sensors via interfacial stress dispersion. Nano Energy 133, 110482 (2025).

Gul, O. et al. Bioinspired interfacial engineering for highly stretchable electronics. Nat. Commun. 16, 1337 (2025).

Ma, Y., Feng, X., Rogers, J. A., Huang, Y. & Zhang, Y. Design and application of ‘J-shaped’ stress-strain behavior in stretchable electronics: a review. Lab Chip 17, 1689–1704 (2017).

Zhao, C., Park, J., Root, S. E. & Bao, Z. Skin-inspired soft bioelectronic materials, devices and systems. Nat. Rev. Bioeng. 2, 671–690 (2024).

Ma, Y. et al. Design of strain-limiting substrate materials for stretchable and flexible electronics. Adv. Funct. Mater. 26, 5345–5351 (2016).

Brooks, A. K., Chakravarty, S., Ali, M. & Yadavalli, V. K. Kirigami-inspired biodesign for applications in healthcare. Adv. Mater. 34, 2109550 (2022).

Park, J. et al. Kirigami-inspired gas sensors for strain-insensitive operation. Results Eng. 21, 101805 (2024).

Yong, K. et al. Kirigami-inspired strain-insensitive sensors based on atomically-thin materials. Mater. Today 34, 58–65 (2020).

Xin, Y., Zhou, J., Nesser, H. & Lubineau, G. Design strategies for strain-insensitive wearable healthcare sensors and perspective based on the Seebeck coefficient. Adv. Electron. Mater. 9, 2200534 (2023).

Hou, Z. et al. Smart fibers and textiles for emerging clothe-based wearable electronics: materials, fabrications and applications. J. Mater. Chem. A 11, 17336–17372 (2023).

Hanif, A. & Kim, D. S. Micro/nanofibers for flexible, stretchable, and strain-insensitive wearable electronics—a review. Adv. Sens. Res. 4, 2400133 (2025).

Sun, T., Liang, Y., Ning, N., Wu, H. & Tian, M. Strain-insensitive stretchable conductive fiber based on helical core with double-network hydrogel. Adv. Fiber Mater. 7, 882–893 (2025).

Yu, L. et al. Highly stretchable, weavable, and washable piezoresistive microfiber sensors. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 10, 12773–12780 (2018).

Lee, J. et al. Conductive fiber-based ultrasensitive textile pressure sensor for wearable electronics. Adv. Mater. 27, 2433–2439 (2015).

Wang, Z. et al. Optical microfiber intelligent sensor: wearable cardiorespiratory and behavior monitoring with a flexible wave-shaped polymer optical microfiber. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 16, 8333–8345 (2024).

Trung, T. Q. et al. Freestanding, fiber-based, wearable temperature sensor with tunable thermal index for healthcare monitoring. Adv. Healthc. Mater. 7, 1800074 (2018).

Yoon, K. et al. Strain-insensitive stretchable fiber conductors based on highly conductive buckled shells for wearable electronics. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 15, 18281–18289 (2023).

Li, Y. et al. A highly stretchable and conductive continuous composite filament with buckled polypyrrole coating for stretchy electronic textiles. Appl. Surf. Sci. 610, 155515 (2023).

Sun, F. et al. Stretchable conductive fibers of ultrahigh tensile strain and stable conductance enabled by a worm-shaped graphene microlayer. Nano Lett. 19, 6592–6599 (2019).

Lee, J. et al. Intrinsically strain-insensitive, hyperelastic temperature-sensing fiber with compressed micro-wrinkles for integrated textronics. Adv. Mater. Technol. 5, 2000073 (2020).

Yuan, H. et al. Ultra-stable, waterproof and self-healing serpentine stretchable conductors based on WPU sheath-wrapped conductive yarn for stretchable interconnects and wearable heaters. Chem. Eng. J. 473, 145251 (2023).

Trung, T. Q. et al. A stretchable strain-insensitive temperature sensor based on free-standing elastomeric composite fibers for on-body monitoring of skin temperature. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 11, 2317–2327 (2019).

Zheng, L. et al. Conductance-stable liquid metal sheath-core microfibers for stretchy smart fabrics and self-powered sensing. Sci. Adv. 7, 1–11 (2021).

Wang, M. et al. Conductance-stable and integrated helical fiber electrodes toward stretchy energy storage and self-powered sensing utilization. Chem. Eng. J. 457, 141164 (2023).

Kim, H. et al. A highly sensitive wearable thermometer with MWCNT and PEDOT:PSS composite. Adv. Mater. Technol. 2401893, 1–10 (2025).

Fan, W. et al. An antisweat interference and highly sensitive temperature sensor based on poly(3,4-ethylenedioxythiophene)-poly(styrenesulfonate) fiber coated with polyurethane/graphene for real-time monitoring of body temperature. ACS Nano 17, 21073–21082 (2023).

Li, F., Xue, H., Lin, X., Zhao, H. & Zhang, T. Wearable temperature sensor with high resolution for skin temperature monitoring. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 14, 43844–43852 (2022).

Choi, H. & Jeong, U. Purposive design of stretchable composite electrodes for strain-negative, strain-neutral, and strain-positive ionic sensors. Adv. Mater. 35, 2306795 (2023).

Wendt, D., van Loon, L. J. C. & van Marken Lichtenbelt, W. D. Thermoregulation during exercise in the heat: strategies for maintaining health and performance. Sports Med. 37, 669–682 (2007).

Taylor, N. A., Tipton, M. J. & Kenny, G. P. Considerations for the measurement of core, skin and mean body temperatures. J. Therm. Biol. 46, 72–101 (2014).

Marriott, B. M. (Ed.) Nutritional needs in hot environments: applications for military personnel in field operations. (National Academies Press, 1993).

Seeley, A. D., Giersch, G. E. & Charkoudian, N. Post-exercise body cooling: skin blood flow, venous pooling, and orthostatic intolerance. Front. Sports Act. Living 3, 658410 (2021).

Kim, M. et al. Stretchable and biocompatible transparent electrodes for multimodal biosignal sensing from exposed skin. Adv. Electron. Mater. 9, 2300075 (2023).

Liu, B., Luo, Z., Zhang, W., Tu, Q. & Jin, X. Silver nanowire-composite electrodes for long-term electrocardiogram measurements. Sens. Actuators A Phys. 247, 459–464 (2016).

Xing, Z. et al. High-sensitivity humidity sensing of microfiber coated with three-dimensional graphene network. Sens. Actuators B Chem. 281, 953–959 (2019).

Sasikanth, G., Subramanyam, B. V. R. S. & Radhakrishnan, T. P. Efficient humidity sensing and stable moisture energy generation with polyaniline emeraldine base–poly(sodium 4-styrenesulfonate) thin film. J. Phys. Chem. C 128, 10818–10825 (2024).

Acknowledgements

D.K. thanks the support by the National Research Foundation of Korea (NRF) grant funded by the Korea government (MSIT) (Grant No. RS-2023-00208702). U.J. appreciates the support from the National Research Foundation of Korea (NRF) funded by the Korean government (MIST) (RS-2024-00338686).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

A.H. conceptualized the research, designed the experiments, developed the materials, and conducted the investigations; A.H. and J.P. designed and performed the measurements and data acquisition; D.K. and J.Y. analyzed the data and supported characterization; A.H. and J.P. wrote and edited the paper; D.S.K. and U.J. supervised the research and acquired funding. All authors contributed to the discussion on the paper.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

IRB approval/ethics declaration

This study was approved by the Institutional Review Board office at POSTECH Ethics Committee (PIRB-2025-E015). Signed consent from the human participant was received before the research.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Hanif, A., Park, J., Kim, D. et al. Microfiber epidermal thermometer (MET) with extraordinary high precision designed for long-term use on hairy skin. npj Flex Electron 9, 82 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41528-025-00464-x

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41528-025-00464-x