Abstract

Stretchable triboelectric nanogenerators (TENGs) have garnered significant attention as wearable power sources by enabling the realization of self-powered systems through integration with other wearable platforms. However, achieving intrinsically stretchable TENGs with stable performance under deformation remains a major challenge, particularly in forming robust dielectric/electrode interfaces and fabricating fully stretchable materials. Here, we propose the intrinsically stretchable ionogel-based TENGs (S-iTENG) with a monolithic structure by directly coating silver nanowires (AgNWs) onto free-standing ionogel. The ionogel serves as the substrate, charge-generating, and trapping layer, simplifying device configuration. Its hydrophilic characteristics improve the wettability of AgNWs and their interfacial adhesion. The optimized S-iTENG exhibits a power density of ~109.8 mW·m−2, excellent stretchability (~195%), and stable operation even under 80% strain. The practical feasibility of the S-iTENG is demonstrated in self-powered sensory platforms. Overall, these results highlight the significance of monolithic, substrate-free S-iTENG as wearable energy harvesters and key components for future wearable electronics.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

With the rapid advancement of wearable electronics, the demand for flexible/stretchable and sustainable power devices has grown significantly. Among the various energy-harvesting technologies, triboelectric nanogenerators (TENGs) have emerged as promising wearable power sources due to their simple layered structure and efficient energy conversion even at low frequencies1,2,3. As wearable platforms pursue higher stretchability and adaptability, the development of stretchable TENGs with stable performance under mechanical deformation becomes essential. To fabricate intrinsically stretchable TENGs, the employment of elastic materials for all components is crucial not only to ensure sufficient deformability but also to enhance overall device performance4. Considering the conventional use of polymers, metal oxides, and metals as charge-generating5,6, trapping7,8,9, and collecting layers10,11,12, respectively, their limited stretchability hinders the realization of fully stretchable TENGs. Although molecular and structural modifications can improve deformability, the mismatch in stretchability between layers and the resulting poor interfacial adhesion remain critical obstacles for practical applications13,14. In addition, geometrically engineered conductive films such as serpentine-patterned metals have been employed as another strategy to enhance stretchability15,16. However, these designs typically require complex fabrication processes, including photolithography or laser patterning, and often provide limited surface coverage, which can hinder overall device performance due to the reduced contact area. Some recent studies have demonstrated ultra-thin TENGs with excellent conformability and high power density17,18. These ultra-thin devices often require spin-coating or spray-coating onto supporting substrates, thereby limiting substrate independence. Moreover, their mechanical robustness and long-term durability under repeated deformation remain major concerns.

Ionogels, consisting of polymeric gelators and ionic liquids (ILs), enable a simplified TENG configuration. As the ionogels can simultaneously serve as both the charge-generating and trapping layers, the interfacial issue arising between these two components disappears. Their high electrical double layer (EDL) capacitance is another advantageous feature, which effectively prevents the recombination of generated electrical charges, ultimately leading to higher performance19. Moreover, ionogels offer excellent stretchability when copolymer gelators are rationally designed20,21,22,23,24. These features highlight the strong potential of ionogels for use in stretchable TENGs25,26,27.

On the other hand, considerable efforts have been devoted to improving the stretchability of the charge-collecting layer (electrode) without significantly compromising its conductivity. Among numerous conductive materials such as liquid metals28,29,30, metal inks31,32, and carbon nanotubes33,34, silver nanowires (AgNWs) are considered one of the most promising candidates, as they form interconnected percolative networks that ensure stable electrical performance even under strain35,36,37. However, AgNWs exhibit poor adhesion to relatively hydrophobic elastic substrates (e.g., plastics), so electrical integrity may be lost under repeated mechanical deformation38,39. While plasma treatment of plastic substrates is able to improve adhesion, its effect is temporary and insufficient to ensure long-term stability40,41. Furthermore, interfacial delamination between the AgNW-based charge-collecting layer and the overlying charge-generating/trapping layer further degrades mechanical integrity.

In this work, we propose an intrinsically stretchable TENG with a monolithic configuration that enhances interfacial adhesion and ensures mechanical deformability. To this end, a hydrophilic ionogel consisting of poly(hydroxyethyl acrylate) (PHEA) and 1-ethyl-3-methylimidazolium dicyanamide ([EMI][DCA]) was designed to provide strong adhesion to AgNWs without additional post-treatments. Then, AgNWs were directly spray-coated onto the ionogel for monolithic integration. The mechanical robustness of the ionogel allows the realization of a substrate-free device. Namely, the ionogel simultaneously functioned as the charge-generating layer, charge-trapping layer, and the elastic substrate for the charge-collecting layer, resulting in a highly simplified device structure. The overall mechanical properties and performance of the stretchable ionogel-based TENG (S-iTENG) were optimized by tailoring the characteristics of the ionogel and AgNW layers, leading to high stretchability (~195%), a voltage output of ~94 V, and reliable operation even under deformation up to 80%. The practical feasibility of the S-iTENG was demonstrated in self-powered high-precision human motion sensory platforms. By tracking the magnitude of the voltage generated under different mechanical conditions (pressure/strain), a wide range of body movements could be effectively monitored. These results indicate the potential of the S-iTENG as a simple but advanced power source and self-powered wearable sensory platform, positioning it as a key component for next-generation wearable devices and energy harvesting systems.

Results

Structural design and monolithic integration of S-iTENG

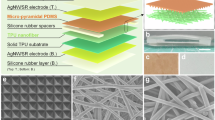

Figure 1a illustrates the structure of the monolithic S-iTENG device, which consists solely of an indium tin oxide (ITO)-coated polyethylene terephthalate (PET) film, an ionogel, and an AgNW layer. The PET and ionogel were used as the contact (charge-generating) layers. The ionogel can form a high-capacitance EDL through the movement of internal ions in response to the generated triboelectric charges, effectively reducing charge recombination. This characteristic makes it suitable for use as a charge-trapping layer. Moreover, to support its additional role as a deformable substrate for the charge-collecting layer (electrode, AgNWs), the effect of the photo-polymerized ionogel composition on mechanical robustness was investigated at five different IL concentrations from 10 to 50 wt% (Supplementary Fig. 1). Irrespective of IL concentration, all ionogels showed elastic solid-like behavior, characterized by G’ > G” over the entire experimental frequency range42. The AgNW layer was electrically connected to the counter ITO charge-collecting electrode via an external circuit to supply the generated electricity to an electronic component.

a Schematic illustration of the monolithic configuration and overall mechanical deformability of the intrinsically stretchable S-iTENG. b Fabrication process of the AgNWs spray-coated ionogel. c Photographs of the AgNWs/ionogel bilayer and the AgNW layer morphology at the initial and stretched state (40% strain). d Overview of the working principle of the S-iTENG and the corresponding voltage profile. e Potential applications of the S-iTENG as a wearable power source and a self-powered sensor.

Since S-iTENG requires deformable electrodes with high reliability, AgNWs are directly spray-coated onto the free-standing ionogel to realize an intrinsically stretchable energy harvesting platform (Fig. 1b). Considering that AgNWs are wrapped with polyvinylpyrrolidone (PVP) and dispersed in isopropanol (IPA), hydrophilic HEA and [EMI][DCA] are selected for ionogel components to establish a robust interface with strong adhesion and enable monolithic integration. The hydroxyl group in HEA improves the affinity for AgNWs through hydrogen bonding with the carbonyl groups of the PVP layer on the AgNWs surface (Supplementary Fig. 2). The PVP layer on the AgNW surface not only ensures strong adhesion with the ionogel but also serves as a protective capping layer that suppresses surface oxidation, thereby contributing to reliable device performance (Supplementary Fig. 3). Also, the hydrophilic IL, [EMI][DCA], is employed to ensure compatibility with HEA. As a result, the [EMI][DCA] gel exhibits excellent homogeneity and optical transparency, whereas the use of a hydrophobic IL (e.g., 1-ethyl-3-methylimidazolium bis(trifluoromethylsulfonyl)imide ([EMI][TFSI])) leads to phase separation in the gel (Supplementary Fig. 4). The resulting AgNWs/ionogel bilayer exhibited intrinsic stretchability, providing reliable mechanical adaptability under deformation (Fig. 1c). Although some microcracks are formed when uniaxial strain is applied, the AgNW network structure maintains the stability of the electrical pathway in the electrode at moderate strain levels. These characteristics enable stable charge collection and efficient energy conversion in the S-iTENG, even during dynamic mechanical loading.

Working mechanism and application of S-iTENG

The overall working principle of the S-iTENG is illustrated in Fig. 1d. At the initial state, [EMI]+ and [DCA]– ions are uniformly distributed over the entire ionogel. Upon contact between the PET and the ionogel (stage Ⅰ), surface charges are generated at the interface via triboelectrification. According to the triboelectric series, PET is considered a tribo-positive material and tends to acquire positive charges through triboelectric contact. Thus, negative charges are induced on the ionogel surface. As the PET gradually separates from the ionogel (stage Ⅱ), [EMI]+ cations migrate toward the negatively charged ionogel surface, while [DCA]– anions move toward the AgNW electrode for electrostatic equilibrium. When the PET is completely separated from the ionogel (stage Ⅲ), [EMI]+ and [DCA]– accumulate near the ionogel surface and the AgNW surface, respectively, leading to the formation of an EDL within the ionogel. When the positively charged PET approaches the ionogel again (stage Ⅳ), the ions return to the initial state, and electrons flow back to the AgNW electrode through the external circuit. Since the ionogel can form an EDL in response to the induced surface charges, replacing the tribo-positive PET with tribo-negative polydimethylsiloxane (PDMS) as the charging-generating layer results in an inversion of the voltage profile with the same ionogel (Supplementary Fig. 5).

The intrinsic deformability of the S-iTENG enhances its practicality as a stretchable power source. Furthermore, operating in single-electrode mode allows the device to be readily mounted on body parts experiencing strain simply by attaching it to the skin. The attached S-iTENG harvests energy via triboelectrification between the ionogel and the skin, thereby generating electrical signals. By tracking the open-circuit voltage (VOC), human motion can be monitored without an external power source, demonstrating the potential of the S-iTENG as a self-powered sensory system (Fig. 1e).

AgNW coating optimization and interfacial compatibility with ionogel substrates

The compatibility of the ionogel with the AgNW-based charge-collecting layer was assessed by comparing the water contact angles on representative stretchable elastomers, such as PDMS and polystyrene-block-polybutadiene-block-polystyrene (SBS) (Fig. 2a). The water contact angle of the ionogel was measured to be ~33.5°, which was notably lower than those of the PDMS ( ~93.6°) and SBS ( ~79.3°), indicating its hydrophilic nature and higher suitability as a deformable substrate for AgNWs. Figure 2b compares the surface morphologies of AgNW-coated samples, in which all samples were prepared at the same AgNW concentration. When AgNWs were spray-coated onto the relatively hydrophobic PDMS and SBS films, noticeable agglomeration and dewetting were observed. In contrast, the use of the hydrophilic ionogel facilitated the formation of a uniform and continuous AgNW network, attributed to improved wetting behavior and strong interfacial interactions between the PVP-wrapped AgNWs and the polar functional groups within the ionogel matrix. This uniform deposition is crucial for obtaining reliable electrical performance and mechanical integrity in stretchable electronic applications. The robust interface between the ionogel and AgNWs was further verified through peel-off tests (Supplementary Fig. 6). Due to the lack of favorable interfacial interactions, the AgNW layer was easily detached from both PDMS and SBS substrates, resulting in an abrupt increase in relative resistance change. In contrast, the AgNWs on the ionogel maintained a low resistance change even after repeated tape-peeling cycles, demonstrating their strong interfacial adhesion with AgNWs (Supplementary Fig. 7).

a Contact angles of stretchable elastomers: PDMS, SBS, and ionogel. b Photographs and optical microscopy images of AgNW-coated surfaces. Sheet resistance of the AgNW layer as a function of (c) IL content in the ionogel and (d) the number of AgNW spray coatings. e FE-SEM images of AgNW-coated surfaces at different AgNW coating cycles.

To examine the effect of IL content in the ionogel on the AgNW coating performance, the sheet resistance was measured (Fig. 2c). The concentration of [EMI][DCA] was systematically adjusted to 0, 20, and 40 wt% relative to HEA. For all ionogel compositions, the sheet resistance of the coated AgNW layer was consistently determined to be average 7 ~ 8 Ω·sq−1. This similar conductivity was further supported by the observation that the morphology of the AgNW layer was not significantly affected by the IL content (Supplementary Fig. 8), as the ionogel consistently retained its hydrophilic characteristic regardless of IL concentration (Supplementary Fig. 9).

In general, a thicker AgNW layer provides higher conductivity but compromises its deformability. Therefore, the number of spray coating cycles and the concentration of AgNW ink must be carefully controlled to achieve a balance between these two metrics. To this end, a low-concentration AgNW solution (0.25 wt%) was repeatedly sprayed onto the gel surface. As the number of spray cycles increased from 5 to 20, the sheet resistance exhibited a significant decrease, indicating enhanced percolation and connectivity of the conductive AgNW network (Fig. 2d). However, no significant change was detected beyond 20 cycles, probably due to the coverage saturation. This correlation was further supported by field emission scanning electron microscopy (FE-SEM) images, which revealed increased AgNW density and interconnectivity with higher spray coating cycles (Fig. 2e). Moreover, in terms of another critical parameter, deformability, the AgNW-coated ionogel fabricated with 25 spray coatings exhibited the poorest stretchability, which is attributed to the relatively thick and stiff AgNW layer with increased coating cycles (Supplementary Figs. 10 and 11). These observations represent a trade-off between electrical performance and mechanical robustness, suggesting that 20 spray coatings offer the most suitable balance for use in S-iTENGs.

Optimization of electrochemical properties and output performance of S-iTENGs

While the IL content in the ionogel did not affect the AgNW coating processability, it remains a critical parameter, as the ionogel should additionally function as a charge-generating and charge-trapping layer. Therefore, the dependence of electrochemical properties of ionogels on IL content (0–50 wt% relative to HEA) was explored by measuring the ionic conductivity (σ) (Fig. 3a) and capacitance (C) (Fig. 3b). From the plateau |Z| value in bode plots, where the resistive component is the dominant contributor (Supplementary Fig. 12), the ionic conductivity was extracted using the relation σ = h/AR with h, A, and R representing the gel thickness, contact area, and bulk resistance, respectively. The increases in conductivity and capacitance with higher IL contents can be rationalized by the lower viscosity of the ionogel and the higher concentration of mobile ion species. Nonetheless, the maximum S-iTENG output performance was obtained with the ionogel containing 40 wt% IL. For example, the output VOC increased continuously to ~85 V with 40 wt% IL content, but decreased when the IL concentration reached 50 wt% (Fig. 3c). A similar trend was observed in the short-circuit current (ISC) and short-circuit charge (QSC) (Fig. 3d and Supplementary Fig. 13). This IL content dependency is attributed to the loss of surface charge caused by current leakage at high IL contents (Fig. 3e and Supplementary Fig. 14). In the presence of excess IL species, free electrons near the ionogel surface leak through internal conductive pathways and recombine with holes at the bottom electrode, thereby reducing surface charge density and degrading output performance43,44,45. This ion-coupled mechanism in the S-iTENG was further investigated by comparing the response dynamics of ionogel-based (40 wt% IL) and polymer-based (0 wt% IL) devices (Supplementary Fig. 15). The sharper and narrower peak of the polymer-based TENG reflects the rapid polarization response of dielectric polymers, whereas the broader peak observed for the ionogel-based TENG is attributed to slower ion migration and EDL formation within the ionogel. The effect of ionogel thickness on the S-iTENG output performance was also examined (Supplementary Fig. 16). The output voltage exhibited negligible dependence on thickness variation, as the effective capacitance of the device is predominantly governed by the interfacial EDL rather than the bulk thickness of the ionogel. Since the EDL forms at the electrode/ionogel interface and its characteristic thickness is on the nanometer scale, changes in the bulk thickness of the ionogel do not significantly affect the overall capacitance46.

Effects of IL content on the (a) ionic conductivity and (b) capacitance of the ionogels. IL content dependence of the (c) VOC and (d) ISC of the S-iTENG. e Schematic diagrams of current leakage pathways in the S-iTENG at high IL content. f Output performance of the S-iTENG with varying contact areas, in which the IL concentration in the ionogel was fixed at 40 wt%. Variations of (g) current density and voltage, and (h) power density of the S-iTENG under different external loads.

The S-iTENG was further characterized under varying contact areas and contact frequencies to evaluate its geometric scalability (Fig. 3f). The VOC exhibited a strong dependence on the contact area, increasing steadily with larger active areas. A maximum VOC of approximately 170 V was recorded for the 5 cm² device, whereas only ~46 V was produced from the 1 cm² configuration. This enhancement is attributed to the larger amount of charge accumulation on the surface of the triboelectric (i.e., charge-generating) layers, enabled by the expanded interfacial area available for EDL formation. Considering the operating environment of wearable applications, where dynamic mechanical input is continuously applied, understanding both the pressure and frequency dependence of device performance is also essential. The S-iTENG exhibited a distinct pressure-dependent increase in output voltage, demonstrating its robustness and high sensitivity under varying mechanical loading (Supplementary Fig. 17). Furthermore, increasing the contact–separation frequency from 1 to 5 Hz led to a noticeable enhancement in the VOC (Supplementary Fig. 18). This observation can be explained by the increased rate of charge transfer and accumulation during repeated contact events, which promotes more efficient electrification at the triboelectric interface47,48. However, when the frequency exceeded 5 Hz, the output voltage began to decrease. This reduction is attributed to excessive surface charge accumulation leading to air breakdown and to incomplete contact–separation cycles at high frequencies, both of which limit effective charge generation49,50.

The peak voltage, current density, and power density were also measured with varying external load resistances. As the external resistance increased, the device current decreased and approached zero (namely, open-circuit condition), and thus the voltage saturated near the VOC. In contrast, reducing the external resistance shifted the system toward a short-circuit regime, increasing current output while decreasing VOC (Fig. 3g). The maximum power output is achieved when the external load is matched to the internal resistance of the S-iTENG, in accordance with the maximum power transfer theorem51. The power density was estimated using P = (V × I)/A, where A is the active area of the device. The highest power density of ~109.81 mW·m−2 and the conversion efficiency of 48% were obtained at an external load resistance of ~107 Ω from the S-iTENG (Fig. 3h). The mechanical durability of the S-iTENG was further evaluated under repeated contact-separation cycles (Supplementary Fig. 19). The S-iTENG maintained a stable output voltage even after 1000 cycles, demonstrating excellent long-term stability and mechanical robustness.

The mechanical robustness and stretchable energy harvesting performance of S-iTENG

The IL content influences not only TENG output performance but also the mechanical deformability of the ionogel. To elucidate this relationship, we examined the strain-stress profiles of ionogels with varying IL compositions (Fig. 4a). As the IL content increased up to 40 wt%, the ionogels exhibited higher toughness and stretchability, which can be attributed to the plasticizing effect of the IL within the polymer network52. Notably, the ionogel with 40 wt% IL achieved an excellent stretchability of ~389% and a maximum toughness of ~0.33 MJ·m−3 (Fig. 4b). It is noted that the use of 50 wt% IL caused excessive plasticization, which loosened the polymer network. While this structural relaxation enhanced stretchability, it simultaneously deteriorated mechanical properties, such as the elastic modulus. Overall, the toughness, defined as the area under the stress–strain curve, was reduced. The 40 wt% IL-containing ionogel showed solid-like elastic behavior (G’ > G”) over the entire frequency range in the time-temperature superposition (tTS) analysis (Fig. 4c), further supporting its mechanical reliability under dynamic conditions. Considering all the forementioned features, the ionogel containing 40 wt% IL was determined to be the most suitable for S-iTENG applications.

a Tensile stress-strain curves of ionogels with different IL contents. b Toughness and maximum stretchability as a function of IL content in the ionogel. c tTS master curves of the optimized ionogel containing 40 wt% IL. d Stress-strain curve and photograph of the S-iTENG during stretching. Change in (e) sheet resistance and (f) VOC of the S-iTENG under applied strain with a proportionally increasing contact area. g Snapshots from Supplementary Movie 1 showing 20 green LEDs being powered by the S-iTENG under 0, 40, 80% strain, with the corresponding circuit diagram.

Although the stiff charge-collecting layer of AgNWs was directly spray-deposited on the ionogel, the stretchability of the monolithically integrated system still exhibited an excellent stretchability of ~195% (Fig. 4d). Moreover, the monolithic system exhibited high mechanical reliability under repeated stretching and releasing cycles with no significant hysteresis (Supplementary Fig. 20). To assess the practical feasibility of the AgNW layer as a stretchable electrode, we measured the sheet resistance at various strain levels (Fig. 4e). The initial sheet resistance at 0% strain was ~2 Ω·sq.−1, and relatively low resistance of ~108 Ω·sq.−1 was maintained even at 80% strain. However, beyond this strain range, disconnection of the AgNW conducting network occurred, resulting in a significant decrease in the electrical conductivity of the S-iTENG electrode (Supplementary Fig. 21). To further evaluate the mechanical reliability of the AgNW electrode under repeated deformation, the cyclic stretching-releasing test at 80% strain was conducted for over 300 cycles. The resistance of the AgNW electrode showed no significant degradation over 300 cycles, indicating electrical durability under repetitive strain (Supplementary Fig. 22). Consequently, the S-iTENG remained operational up to 80% strain, which is still sufficient for practical use in wearable applications53,54.

Figure 4f presents the strain-dependent energy harvesting performance of the S-iTENG. The device was subjected to various strain levels from 0 to 80%. Interestingly, the VOC initially increased with strain, reaching a peak value of ~94 V at 20% strain. This enhancement can be explained by the enlarged contact area between two charge-generating layers (i.e., ionogel and PET), enabled by the use of an ITO/PET film sufficiently large to cover the fully stretched ionogel. For example, the initial contact area before stretching of 3 cm2 was increased to ~3.3 cm² at 20% strain. Considering the correlation between contact area and output performance (Fig. 3f), the measured VOC of ~94 V at 20% strain is in good agreement with expectations. However, when the strain exceeded 20%, the VOC began to decline primarily due to the increased resistance of the AgNW electrode under high strains. To decouple the effect of contact area, an additional experiment was performed using a fixed-size ITO/PET film (3 cm × 3 cm), which ensured a constant contact area regardless of strain (Supplementary Fig. 23). Under this configuration, the output voltage decreased with increasing strain, confirming that the reduced electrical conductivity of the AgNW electrode is the dominant factor. We comment that the S-iTENG was still able to generate a voltage of ~30 V and serve as an effective power source even at 80% strain, despite the voltage degradation at higher strains. For example, when the S-iTENG was connected to 20 green LEDs and manually tapped (Fig. 4g and Supplementary Movie 1), the LEDs lit up successfully in both the initial and stretched states. Furthermore, in contrast to previously reported stretchable TENG systems that often suffer from a trade-off between TENG performance (e.g., output voltage) and mechanical stretchability, the S-iTENG developed in this study successfully achieved an optimal balance between those two parameters (Supplementary Fig. 24). This balance is enabled by the monolithic integration of the stretchable AgNW electrode and the ionogel, which simultaneously serves as the charge-generating/trapping layer and mechanical substrate.

Application of S-iTENG as a self-powered motion sensor for wearable electronics

To further demonstrate the suitability of AgNW electrodes for wearable devices, the effect of different current collectors on the S-iTENG performance was measured (Supplementary Fig. 25). Although metallic conductors such as Cu tape and Al wire can be easily attached to the ionogel, their output performance was much lower than that of AgNWs due to poor interfacial contact and weak adhesion. By contrast, AgNWs directly coated on the ionogel formed a conformal and strongly adhered interface, enabling efficient charge collection under mechanical deformation. By taking advantage of the high mechanical durability of the monolithic system against various mechanical deformations, such as folding, twisting, rolling, and stretching (Supplementary Fig. 26), along with its softness and simplicity, the S-iTENG could be easily attached to human joints as a self-powered motion monitoring system. The sensing mechanism using the S-iTENG is illustrated in Fig. 5a. Upon finger bending, the S-iTENG stretches and makes contact with the skin, resulting in triboelectrification. Due to the tribo-positive nature of human skin, it can act as a triboelectric layer, enabling the S-iTENG to operate in single-electrode mode. When the finger is straightened, an air gap is formed between the skin and the S-iTENG. Subsequently, the ion movements (namely, [EMI]+ and [DCA] –) commence within the gel, generating characteristic output voltage waves. Based on this principle, the S-iTENG can be used as a self-powered strain sensor that operates without an external power supply.

Figure 5b displays the electrical signals produced during finger bending. A larger strain induced by a higher bending angle (e.g., 90°) resulted in an increased VOC, attributed to the enlarged contact area of the S-iTENG. Furthermore, the device consistently responded to finger motions regardless of bending frequency. This result indicated its reliable sensory performance under dynamic conditions. To further demonstrate its applicability as a motion sensor, the S-iTENG was attached to four additional body parts: the wrist, ankle, elbow, and knee (Fig. 5c–f). Each joint produced a distinct voltage signal during bending-releasing motions, reflecting differences in mechanical input. Even under identical motion conditions (e.g., bending angle and frequency), the strain level was varied depending on the joint (~15% for the finger, ~25% for the wrist and ankle, and ~40% for the elbow and knee). This joint-specific deformation led to a larger contact area and further amplified the voltage output. As a result, the VOC progressively increased from the finger to the knee, with the highest voltage recorded at the knee during walking. By tracking the magnitude of generated VOC, the S-iTENG enabled high-precision human motion detection, highlighting its feasibility as a self-powered sensory system for wearable applications.

Discussion

In this work, we developed a monolithically integrated and intrinsically stretchable ionic TENG platform based on a free-standing ionogel and a directly coated AgNW electrode. The ionogel simultaneously served as the charge-generating layer, charge-trapping layer, and elastic substrate, enabling a substrate-free and simplified device configuration. Owing to its hydrophilic characteristic and high mechanical robustness, the ionogel ensured strong interfacial adhesion with AgNWs and maintained reliable performance under strains up to 80%. The optimized S-iTENG exhibited excellent stretchability (~195%), a power density of ~109.8 mW·m−2, and stable energy harvesting under repeated deformation. When directly attached to the body, the S-iTENG successfully functioned as a self-powered motion sensor, capable of detecting various human joint movements with high strain sensitivity and motion specificity. These results highlight the practical feasibility of the S-iTENG not only as a robust and deformable power source but also as a highly effective wearable sensor. This dual functionality offers a promising route toward next-generation self-powered platforms for wearable systems.

Methods

Materials

2-HEA (96%), [EMI][DCA] ( ≥ 98%), 2-hydroxy-2-methylpropiophenone (97%), SBS, and ITO-coated PET film (surface resistivity ~60 Ω·sq−1) were purchased from Sigma–Aldrich. The AgNW solution dispersed in IPA (diameter: 20 nm, length: 20 μm, 0.5 wt%) was obtained from SG Flexio Co., Ltd. PDMS elastomers were prepared by mixing Sylgard 184 base and curing agent (Dow Corning) at a 10:1 weight ratio. SBS block copolymers were dissolved in tetrahydrofuran solvent.

Preparation of ionogels

Ionogels were synthesized via a simple one-pot polymerization. HEA monomer (3.54 g, 0.061 mol), Photoinitiator (Irgacure 1173) (0.05 g, 0.61 mmol), and [EMI][DCA] (0 ~ 50% by weight relative to monomer) were mixed homogeneously. The detailed composition details of all ionogels are summarized in Supplementary Table 1. The mixture was poured into a Teflon mold (thickness: 1 mm, width: 10 mm, and length: 30 mm) and irradiated under a UV lamp for 180 s at room temperature. After photo-gelation, residual monomers were removed in a vacuum oven at 100 °C for 30 min (Supplementary Fig. 27).

Fabrication of the S-iTENG

AgNW solution (0.25 wt%) was uniformly coated onto the ionogel using a spray coater (Shot Mini 200 SX, Musashi) equipped with a digital spray controller (ME-5000 SP, Musashi). To remove the PVP layer on the AgNWs, the AgNW dispersion was centrifuged at 4000 rpm for 5 min. The supernatant was carefully decanted, and the residual precipitate was redispersed in IPA. This procedure was repeated five times to ensure effective removal of the PVP layer (Supplementary Fig. 28). After coating, the solvent was evaporated on a heated plate at 100 °C. The coated ionogel was inverted, utilizing AgNWs as the bottom electrode and the ionogel as the dielectric layer in the S-iTENG. The ITO/PET film was cut into 3 × 3 cm2, where PET was utilized as the contact layer and ITO as the top electrode. Aluminum wire was attached to the ionogel for electrical connection. A full-wave bridge rectifier was integrated with the S-iTENG for driving 20 green LEDs.

Energy conversion efficiency of S-iTENG

The energy conversion efficiency was calculated as the ratio of generated output electrical energy to the input mechanical energy, using the following equation55:

The output electrical energy is given by

where I is the current, and R is the load resistance at which the maximum power is reached.

The input mechanical energy is given by

where m is the mass of ITO/PET film (m = 0.0011 kg), and v is the velocity of the ITO/PET film immediately prior to contact (v = 0.2 m/s).

Based on this calculation, the calculated maximum efficiency was observed to be 48% at 107 Ω of load resistance.

Mechanical and rheological analyses

Tensile stress-strain curves were obtained using a z-axis motorized force applier (ESM303, Mark-10) and a force gauge (M5-10, Mark-10) at a loading speed of 6 mm·min−1. Rheological properties of the ionogel were assessed on a rheometer (MCR 302, Anton Paar) with 8 mm parallel plates. The frequency and strain amplitude were fixed at 10 rad·s−1 and 1%, respectively. tTS analysis was measured using a frequency sweep of 0.1–100 rad·s−1 at temperatures ranging from 0 °C to 150 °C. The applied strain and reference temperature were set at 1% and 20 °C, respectively. Master curves were obtained using shift factors.

Electrical and electrochemical analyses

The changes in resistance (–R/R0) of AgNWs and I-V characteristics of the ionogel were analyzed by employing a source meter (2450, Keithley). The sheet resistance of the AgNW-coated ionogel was recorded with sheet resistance measurement equipment (CMT-100J, AIT). The ionic conductivity and capacitance of the ionogel were determined using electrochemical impedance spectroscopy (IM6, Zahner) under an AC amplitude of 10 mV across a frequency range from 10−1 to 105 Hz.

Morphological and surface characterizations

The surface of the AgNW-coated substrate was observed through an optical microscope (BX43, Olympus). FE-SEM (SU8010, Hitachi) was employed to examine the surface structure and thickness of the AgNW-coated ionogel. Contact angles of the ionogel were measured using a goniometer (CAM 200, KSV). The attenuated total reflection Fourier-transform infrared (ATR-FTIR) spectra were recorded using a Spectrum 100 instrument (PerkinElmer).

S-iTENG output performance characterizations

The output voltage, current, and charge of the S-iTENG were recorded on a digital storage oscilloscope (TDS 2024 C, Tektronix) and electrometer (6517B, Keithley). The applied pressure on the S-iTENG was quantitatively measured using a force-sensitive resistor (FSR) sensor. We also note that the S-iTENG was attached to the body parts of a volunteer who participated in the experiment with fully informed consent.

Data availability

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

References

Wu, C., Wang, A. C., Ding, W., Guo, H. & Wang, Z. L. Triboelectric nanogenerator: A foundation of the energy for the new era. Adv. Energy Mater. 9, 1802906 (2019).

Zhang, S. L. et al. Rationally designed sea snake structure based triboelectric nanogenerators for effectively and efficiently harvesting ocean wave energy with minimized water screening effect. Nano Energy 48, 421–429 (2018).

Yu, Y. et al. Biocompatibility and in vivo operation of implantable mesoporous PVDF-based nanogenerators. Nano Energy 27, 275–281 (2016).

Garg, R. et al. Polarization-induced mechanically socketed ultra-stretchable and breathable textile-based nanogenerator and pressure sensor. Adv. Funct. Mater. 34, 2401593 (2024).

Lee, J. H., Yu, I., Hyun, S., Kim, J. K. & Jeong, U. Remarkable increase in triboelectrification by enhancing the conformable contact and adhesion energy with a film-covered pillar structure. Nano Energy 34, 233–241 (2017).

Wang, S. et al. Maximum surface charge density for triboelectric nanogenerators achieved by ionized-air injection: Methodology and theoretical understanding. Adv. Mater. 26, 6720–6728 (2014).

Chen, X. et al. Electron trapping & blocking effect enabled by MXene/TiO₂ intermediate layer for charge regulation of triboelectric nanogenerators. Nano Energy 98, 107236 (2022).

Park, H. et al. Electron blocking layer-based interfacial design for highly-enhanced triboelectric nanogenerators. Nano Energy 50, 9–15 (2018).

Wu, C. et al. Enhanced triboelectric nanogenerators based on MoS₂ monolayer nanocomposites acting as electron-acceptor layers. ACS Nano 11, 8356–8363 (2017).

Seung, W. et al. Nanopatterned textile-based wearable triboelectric nanogenerator. ACS Nano 9, 3501–3509 (2015).

Luo, J. et al. Flexible and durable wood-based triboelectric nanogenerators for self-powered sensing in athletic big data analytics. Nat. Commun. 10, 5147 (2019).

Li, H. et al. Multi-scale metal mesh based triboelectric nanogenerator for mechanical energy harvesting and respiratory monitoring. Nano Energy 89, 106423 (2021).

Bai, P. et al. Integrated multilayered triboelectric nanogenerator for harvesting biomechanical energy from human motions. ACS Nano 7, 3713–3719 (2013).

Chung, I. J. et al. Layer-by-layer assembled graphene multilayers on multidimensional surfaces for highly durable, scalable, and wearable triboelectric nanogenerators. J. Mater. Chem. A 6, 3108–3115 (2018).

Zhao, L., Lin, Z. & Lai, K. W. C. Skin-integrated, stretchable triboelectric nanogenerator for energy harvesting and mechanical sensing. Mater. Today Electron. 2, 100012 (2022).

Salauddin, M. et al. Highly electronegative V2CTx/silicone nanocomposite-based serpentine triboelectric nanogenerator for wearable self-powered sensors and sign language interpretation. Adv. Energy Mater. 13, 2203812 (2023).

Liu, Z., Zhao, Z., Zeng, X., Fu, X. & Hu, Y. Ultrathin, flexible and transparent graphene-based triboelectric nanogenerators for attachable curvature monitoring. J. Phys. D: Appl. Phys. 52, 314002 (2019).

Zhang, Y. et al. Ultra-thin and sensitive pressure sensor based on MXene/PVDF-HFP composite fiber TENG for self-diagnosis of ligament injuries. Nano Energy 132, 110372 (2024).

Lim, D. U. et al. Ion-impregnated intermediate layer for enhancing triboelectric nanogenerator performance. Adv. Funct. Mater. 34, 2401717 (2024).

Kim, Y. M. & Moon, H. C. Ionoskins: nonvolatile, highly transparent, ultrastretchable ionic sensory platforms for wearable electronics. Adv. Funct. Mater. 30, 1907290 (2020).

Ding, Y. et al. Preparation of high-performance ionogels with excellent transparency, good mechanical strength, and high conductivity. Adv. Mater. 29, 1704253 (2017).

Kim, Y. M., Kwon, J. H., Kim, S., Choi, U. H. & Moon, H. C. Ion-cluster-mediated ultrafast self-healable ionoconductors for reconfigurable electronics. Nat. Commun. 13, 3769 (2022).

Ren, Y. et al. Ionic liquid-based click-ionogels. Adv. Sci. 5, eaax0648 (2019).

Kim, Y. M., Yu, K. S. & Moon, H. C. Regulating the π-π interactions of copolymer gelators: Effective molecular design of highly stretchable and tough ionogels for wearable ionotronics. Chem. Eng. J. 480, 147947 (2024).

Liu, Y. et al. Versatile ion-gel fibrous membrane for energy-harvesting iontronic skin. Adv. Funct. Mater. 33, 2303723 (2023).

Li, G. et al. Transparent, stretchable and high-performance triboelectric nanogenerator based on dehydration-free ionically conductive solid polymer electrode. Nano Energy 88, 106289 (2021).

Han, J. H., Kim, S. Y. & Moon, H. C. Unveiling the impact of tailoring ionic conductor characteristics on the performance of wearable triboelectric nanogenerators. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 16, 27778–27784 (2024).

Wang, S., Ding, L., Fan, X., Jiang, W. & Gong, X. A liquid metal-based triboelectric nanogenerator as stretchable electronics for safeguarding and self-powered mechanosensing. Nano Energy 53, 863–870 (2018).

Yang, L. et al. Stretchable triboelectric nanogenerator based on liquid metal with varying phases. Adv. Sci. 11, 2405792 (2024).

Pan, C., Liu, D., Ford, M. J. & Majidi, C. Ultrastretchable, wearable triboelectric nanogenerator based on sedimented liquid metal elastomer composite. Adv. Mater. Technol. 5, 2000754 (2020).

Jiang, F. et al. Stretchable, breathable, and stable lead-free perovskite/polymer nanofiber composite for hybrid triboelectric and piezoelectric energy harvesting. Adv. Mater. 34, 2200042 (2022).

Hu, S. et al. A stretchable multimode triboelectric nanogenerator for energy harvesting and self-powered sensing. Adv. Mater. Technol. 7, 2100870 (2022).

Xiong, Q., Yang, Z. & Zhang, X. Flexible triboelectric nanogenerator based on silk fibroin-modified carbon nanotube arrays. Chem. Eng. J. 482, 148986 (2024).

Oguntoye, M., Johnson, M., Pratt, L. & Pesika, N. S. Triboelectricity generation from vertically aligned carbon nanotube arrays. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 8, 27454–27457 (2016).

Lai, Y.-C. et al. Preparation of high-performance ionogels with excellent transparency, good mechanical strength, and high conductivity. Adv. Mater. 29, 1704253 (2017).

Hwang, B.-U. et al. Transparent stretchable self-powered patchable sensor platform with ultrasensitive recognition of human activities. ACS Nano 9, 8801–8810 (2015).

Liang, X. et al. Highly transparent triboelectric nanogenerator utilizing in-situ chemically welded silver nanowire network as electrode for mechanical energy harvesting and body motion monitoring. Nano Energy 59, 508–516 (2019).

Kwon, N. Y. et al. Uniform silver nanowire patterned electrode on robust PEN substrate using poly(2-hydroxyethyl methacrylate) underlayer. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 14, 34909–34917 (2022).

Xiong, M. et al. Silver nanowires deposited on triblock copolymer microfibers for stretchable conductive fabrics. ACS Appl. Nano Mater. 5, 17721–17730 (2022).

Prameswati, A. et al. Highly stretchable and mechanically robust silver nanowires on surface-functionalized wavy elastomers for wearable healthcare electronics. Org. Electron. 108, 106584 (2022).

Liu, H.-S., Pan, B.-C. & Liou, G.-S. Highly transparent AgNW/PDMS stretchable electrodes for elastomeric electrochromic devices. Nanoscale 9, 2633–2639 (2017).

Hong, S. H., Kim, Y. M. & Moon, H. C. Dynamic metal–ligand coordination-assisted ionogels for deformable alternating current electroluminescent devices. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 15, 28516–28523 (2023).

Hwang, H. J. et al. An ultra-mechanosensitive visco-poroelastic polymer ion pump for continuous self-powering kinematic triboelectric nanogenerators. Adv. Energy Mater. 9, 1803786 (2019).

Kim, Y. et al. Ionic liquid-based molecular design for transparent, flexible, and fire-retardant triboelectric nanogenerator (TENG) for wearable energy solutions. Nano Energy 84, 105925 (2021).

Hwang, H. J. et al. Ionic liquid with hydrogen bonding reducing leakage charge for enhancing triboelectric performance. Nano Energy 125, 109535 (2024).

Lee, K. H., Zhang, S., Lodge, T. P. & Frisbie, C. D. Electrical impedance of spin-coatable ion gel films. J. Phys. Chem. B 115, 3315–3321 (2011).

Sardana, S. et al. Flexible, humidity- and contamination-resistant superhydrophobic MXene-based electrospun triboelectric nanogenerators for distributed energy harvesting applications. Nanoscale 15, 19369–19380 (2023).

Cheng, Y., Zhu, W., Lu, X. & Wang, C. Mechanically robust, stretchable, autonomously adhesive, and environmentally tolerant triboelectric electronic skin for self-powered healthcare monitoring and tactile sensing. Nano Energy 102, 107636 (2022).

Jiang, C. et al. All-electrospun flexible triboelectric nanogenerator based on metallic MXene nanosheets. Nano Energy 59, 268–276 (2019).

Shen, X. et al. Punching pores on cellulose fiber paper as the spacer of triboelectric nanogenerator for monitoring human motion. Energy Rep. 6, 2851–2860 (2020).

Niu, S. et al. Theoretical study of contact-mode triboelectric nanogenerators as an effective power source. Energy Environ. Sci. 6, 3576–3583 (2013).

Jansen, J. C., Friess, K., Clarizia, G., Schauer, J. & Izak, P. High ionic liquid content polymeric gel membranes: Preparation and performance. Macromolecules 44, 39–45 (2011).

Souri, H. et al. Wearable and stretchable strain sensors: Materials, sensing mechanisms, and applications. Adv. Intell. Syst. 2, 2000039 (2020).

Yadav, A., Yadav, N., Wu, Y., Ramakrishna, S. & Hongyu, Z. Wearable strain sensors: state-of-the-art and future applications. Mater. Adv. 4, 1444–1459 (2023).

Zhu, G. et al. Toward large-scale energy harvesting by a nanoparticle-enhanced triboelectric nanogenerator. Nano Lett. 13, 847–853 (2013).

Acknowledgements

This research was supported by the Nano & Material Technology Development Program through the National Research Foundation of Korea(NRF), funded by the Ministry of Science and ICT(No. RS-2025-02221332). Also, this research was supported by the Nano & Material Technology Development Program through the National Research Foundation of Korea (NRF) funded by the Ministry of Science and ICT (RS-2023-00283244).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

J.H.H. and H.C.M. conceived the main idea and designed experiments. J.H.H. conducted the experiments and wrote the original manuscript. H.C.M. supervised the project and revised the manuscript. All authors discussed the experimental results.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Han, J.H., Moon, H.C. Monolithically integrated ionic triboelectric nanogenerators for deformable energy harvesting and self powered sensing. npj Flex Electron 9, 114 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41528-025-00491-8

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41528-025-00491-8