Abstract

Bionic limbs require reliable, low-noise and high-comfort interfaces between electrodes and the prosthetic system. This work presents the first fully flexible, wearable myoelectric control system compatible with both dry and wet electrodes. It features a low-noise front-end circuit on foil using amorphous Indium-Gallium-Zinc-Oxide (a-IGZO) Thin-Film Transistors, optimized for multi-electrode sensing. The design includes an autozeroed pre-charging buffer to minimize offset and 1/f noise while maintaining high input impedance (841 MΩ at 50 Hz). The front-end achieves 22 µVrms input noise, < −90 dBc crosstalk, and a 4.6 mV input offset consuming 55.3 µW per channel. EMG signals measured by this AFE were used to drive an elbow musculoskeletal model and predict the resulting human elbow flexion-extension moments, which in turn were used to realize a closed-loop real-time control in a simulated bionic elbow joint, using both dry and wet electrodes. Experiments done with a series of movements show a 20°rms error in angular control.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Limb amputation is a common cause of disability worldwide, affecting approximately 57.7 million individuals as of 20171. Motorized myoelectric prostheses, or bionic arms, present a promising solution for restoring partial limb functionality. These systems typically incorporate control methods that interpret bioelectrical signals from the user, enabling intuitive prosthetic movement2,3.

A key challenge in state-of-the-art prosthetic control systems is to ensure fully volitional and continuous bionic limb control during long-term use. Human arm control requires coordinated, voluntary, neural control of force across multiple muscles spanning a target joint, something challenging to reproduce in an artificial limb4. For individuals with transhumeral amputations, inertial measurement units (IMUs) cannot be used to control the prosthesis, as there is no residual forearm or elbow from which to capture inertial data. Consequently, this work explores the use of surface electromyography (sEMG) signals as an alternative control modality. Although sEMG signals represent a promising solution for interfacing with the human neuro-muscular system, progress has been hampered by limits in the interface between sEMG signals and the prosthesis5. These often arise from motion artifacts, signal crosstalk and interference in the wired connections, or, in the case of wireless solutions, due to the bulky footprint and limited miniaturization. Using Silicon electronics alone would need long interconnects between the electrode and the Silicon chip, a solution that is susceptible to EMI and lowers the input impedance due to the added parasitic capacitance, or necessitates complex interconnect schemes including shielding and guard drivers. Flexible electronics offers a promising solution to these interface challenges by integrating electrodes and readout electronics on a single substrate6. This enables the use of ultra-thin, conformable electrodes that closely adhere to the skin, while also providing signal amplification or buffering near the source. Additional possible benefits of the local electronics on foil are the reduction of the signal crosstalk, increase of the input impedance, the higher robustness to external interference and the lower motion artifacts thanks to the intimate contact with the skin and the low mass.

Previous studies have demonstrated that sensing electrodes can be developed using flexible electronics, and that they can even be integrated with Thin-Film Transistor (TFT) multiplexing solutions to aggregate multiple channels7,8. However, these solutions have two shortcomings. First of all, the input impedance of the TFT readout electronics is relatively low ( < 25MΩ) and decreases with the number of aggregated channels, allowing only the use of impractical wet electrodes. Second, in other designs, the advantages provided by flexible electronics are only partially exploited as the front-end electronics relies solely on active-matrix addressing circuits6, with no local amplification, resulting in limited signal integrity. Despite flexible electronic technologies based on TFTs have been available for more than two decades, designing an active front-end for sEMG sensing is still considered a challenge due to the low noise requirements and the comparatively large low-frequency noise injected by the TFTs.

To bridge this gap, in this work we propose an innovative multiplexed front-end based on a-IGZO TFTs, which combines time-division multiplexing (TDM) with pre-charging using an autozeroed amplifier, addressing input impedance limitations and enhancing the robustness against interference coupling. This solution provides EMG signals with a noise level that enables for the first time a fully conformable and volitional prosthetic control system based on flexible electronics. Besides, the flexible electronics can be interfaced directly even with dry electrodes.

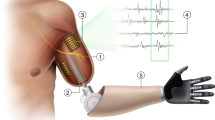

The front-end on foil is directly connected to a Silicon CMOS-based system developed with off-the-shelf electronics, and both are integrated on a flexible printed circuit board. This heterogeneous integration results in a lightweight, conformable and wearable device optimized for prosthetic sensing. The prototype is further coupled to a digital model-based controller to demonstrate its suitability for elbow prosthesis control (Fig. 1a).

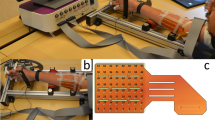

a Diagram of the full system used for prosthesis control. b Photograph of the flexible PCB including the flexible AFE. Insets depict the dry electrodes used and a photo of the flexible AFE. c, d Photographs of the full system attached to the subjects arm. e Diagram of the system used to find the noise requirements of the AFE. f RMSE error of the prothesis system as function of the digitally-added white noise.

Results

System overview

The proposed system architecture for prosthetic control is illustrated in Fig. 1a. The sensing elements consist of an array of four electrodes, with three electrodes functioning as input channels for the prosthesis control, and one serving as a reference. In this work, the sensing electrodes are placed on the biceps, triceps, and brachialis muscles. The three signals from the electrodes are directly connected to the a-IGZO Analog Front-End (AFE) through a flexible PCB using Anisotropic Conductive Epoxy (ACE) bonding made with IQ-BOND 5976. The flexible PCB shown in Fig. 1b−d is designed as an adjustable band that securely wraps around the upper arm, maintaining stability regardless of arm movement. Although the electrodes in this work are not yet monolithically integrated, the a-IGZO TFT technology does support such integration6. The AFE includes a multiplexer with pre-charging to enhance input impedance. Autozeroing is used to reduce the 1/f noise introduced by the pre-charging amplifier9. The a-IGZO AFE is followed by an off-the-shelf Silicon voltage buffer (OPA2140) and an analog-to-digital converter (ADC, PXI-9527), to digitize the signals. Additionally, a microcontroller unit (MCU, ESP32-WROOM-32E) generates the required clock signals to synchronize the system operations. The acquired data is then demultiplexed in the digital domain and used to drive, in real-time, a musculoskeletal model of the human elbow joint, which estimates the resulting human joint flexion-extension moments2. Concurrently, EMG-decoded joint moments are fed to the low-level control logic of a virtual arm prosthesis, thereby enabling volitional and continuous myoelectric control of the prosthetic limb joint rotation (Fig. 1a). Moreover, the angle and velocity of the lower arm are estimated using a Simulink prosthesis model and compared to a reference, obtained by reading an off-the-shelf gyroscope (MPU-6050) attached to the hand with a glove.

The input signals are expected to reach frequencies of up to 500 Hz and amplitudes ranging from 0.5 to 1.5 mVrms, while both electrode DC offset and motion artifacts can potentially reach up to hundreds of millivolts10.

The purpose of the AFE circuit is twofold: first, it enables the use of dry electrodes and thus eases the usability of the system; second, it provides a higher level of signal integrity, lowering the impedance of the interconnect lines it drives. Moreover, the proposed AFE provides multiplexing of four electrodes on a single output. In future applications requiring high-density sEMG sensing, this will significantly reduce the number of interconnections to the Silicon electronics, lowering footprint and costs of the Silicon chip. Compared to the work of Genco et al. 8, Time-Division Multiplexing (TDM) is used, rather than Frequency-Division Multiplexing (FDM). TDM has the advantage that it can be implemented with a single switch per channel, while FDM requires individual optimization for each aggregated channel and the use of multiple distinct clock frequencies, due to the varying bandwidth requirements of each channel.

To determine the specifications for the analog front-end, sEMG data are measured using a state-of-the-art measurement system, i.e., REFA amplifiers11, to derive a reference dataset, as detailed in the Methods section. The control of the prosthetic model based on this reference dataset, achieves an angular root-mean-square error (RMSE) of 12 degrees. To assess the impact of the AFE noise on the control accuracy, the Signal-to-Noise Ratio of the dataset signals has been decreased artificially by adding white noise (Fig. 1e). The results shown in Fig. 1f indicate that the system can tolerate a maximum input-referred noise of 50µVrms to keep an accuracy of 20-degree RMSE. Therefore, considering that the expected artifacts have a maximum amplitude of 150 mV, a dynamic range of 61 dB is required. Furthermore, an input impedance of at least 200 MΩ is necessary to support the use of dry or contactless electrodes12.

Proposed analog front-end

A schematic representation of the proposed analog front-end (AFE) is shown in Fig. 2a. In time-division multiplexing (TDM), the switches \({\phi }_{m,i}\) are employed to interleave in time the four channels indicated by “i” at the Nyquist frequency (resulting in a 4 kHz multiplexer operation speed). Typically, this requires the input to charge the loading capacitor \({C}_{s}\) (Fig. 2a), which is the input capacitance of the electronics driven by the multiplexer, plus the routing parasitics, every time a new channel is selected, detrimentally affecting the input impedance of the multiplexer.

a Schematic representation of the proposed a-IGZO analog front-end (AFE). b Working signals of the pre-charging. \({\phi }_{p}\) is the pre-charging phase, \({\phi }_{m}\) the multiplexing phase. c, d Schematic representation of a single channel with an electrode model included during the (c) pre-charging phase and (d) multiplexing phase. Here, Ve is the myoelectric input signal. e Micrograph of the proposed AFE. f Schematic representation of the amplifier A of Fig. 2a. The biasing voltages Vb1, Vb2, and Vb3 are generated using current mirrors and suitable reference currents.

If only switches would be used as multiplexer, directly connecting the electrodes to the Si electronics, a stray capacitance \({C}_{s}\) of at least 10 pF would be introduced by the routing lines on the PCB. For a sinusoidal signal frequency at the upper end of the input spectrum, 500 Hz, the input impedance would be 32 MΩ, causing a 17 dB signal (and SNR) loss if high impedance (~200 MΩ) electrodes12 would be used. To alleviate this inherent problem in the multiplexing, a possible solution is to drastically reduce the load capacitance by adding e.g., a TFT-based voltage buffer between the output of the multiplexer and the Silicon electronics. The major disadvantage of this solution is that the a-IGZO amplifier will introduce significant noise to the system, due to the relatively large low-frequency noise of the TFTs compared to the Silicon counterpart, for the same power consumption. Indeed, the lowest Noise Efficiency Factor (NEF) reported in flexible electronics to date13 is 9.8, while Silicon amplifiers can reach NEFs of 1 or lower14. To address these shortcomings, we propose here a TFT AFE solution that uses pre-charging to improve the input impedance of the multiplexer without requiring an amplifier in the signal path. Pre-charging15 is a multi-phase technique that provides part of the charge needed to fill the stray capacitance \({C}_{s}\) from the power supply instead of the signal input. Pre-charging has shown to significantly increase the input impedance in a chopper-stabilized amplifier15, here the same technique is used to increase the input impedance of a multiplexer. The working principle is shown in Fig. 2b−d. During the pre-charging phase (Fig. 2c, switch \({\phi }_{p}\) closed and \({\phi }_{m}\) open), the input is conveyed to the load capacitor \({C}_{s}\) through a buffer (A), which allows the load capacitor to be charged via the supply rather than the input. In the multiplexing phase (Fig. 2d, switch \({\phi }_{m}\) closed and \({\phi }_{p}\) open), the input is connected again to the load capacitor (Cs)15. This approach trades off increase in input impedance with increase in noise: as the input sees the \({C}_{s}\) capacitor only during the multiplexing phase \({\phi }_{m}\), the signal impedance is increased choosing a shorter \({\phi }_{m}\). On the other hand, the noise added by the buffer is in principle overridden by the connection to the input during \({\phi }_{m}\), if this phase lasts long enough to effectively charge the capacitor \({C}_{s}\). In this work we chose for equal duration of pre-charging and multiplexing phase. While this discussion is valid for sinusoidal signals, the presence of slow-changing input signals is also very important in determining the total current required from the electrodes. Possible different DC offsets between different electrodes are dealt with during the AFE pre-charging phase \({\phi }_{p}\), and thus have little effect on the current requested by the inputs, as shown in Fig. 2b. As electrode offsets can be as large as ±150 mV10, this is very important in practice. Another contribution to the input current comes from the difference between the voltage \({V}_{{out}}\) sampled on \({C}_{s}\) at the end of the pre-charging phase, Fig. 2c, and the actual value of the electrode voltage, \({V}_{e}\), during the multiplexing phase (shown as \(\Delta V\) in Fig. 2b). Amplifiers designed using TFTs are prone to considerable offset due to the transistor mismatch8, large low-frequency noise, and buffer gain errors, due to the limited gain of the base amplifier used in the buffer, leading to an increase of this input current contribution. To suppress the correlated low-frequency noise and offset, we take advantage of a technique we previously proposed based on autozeroing9, to apply noise-cancellation to the AFE in combination with the pre-charging, and achieve an ultra-low noise front-end with high input impedance. The autozeroing technique is also shown in Fig. 2a. In the first phase, where \({\phi }_{1}\) is closed and \({\phi }_{2}\) is open, the amplifier A is connected in a buffer configuration. Therefore, the top plate of \({C}_{{az}}\) (connected to the negative input of A) is charged to the input voltage and noise + offset is added. The bottom plate of \({C}_{{az}}\) is connected to the input voltage, and thus the capacitor is charged to \({v}_{n}\) (the instantaneous noise + offset voltage of A at the end of the first phase). In the second phase, where \({\phi }_{2}\) is closed and \({\phi }_{1}\) is open, the feedback path of A causes the negative input to stay at the input voltage plus the noise. The output voltage of the buffer is thus equal to the input voltage without the correlated noise and the offset stored at the end of phase 1. Because in this method the input voltage is not switched, the input impedance is not affected by the autozeroing, resulting in better noise performance without compromising the input impedance. The autozeroing is applied at 8 kHz to allow for a full autozeroing cycle for each time the multiplexer is switched.

The micrograph of the system on foil comprising a multiplexed 4-channels AFE is shown in Fig. 2e. Figure 2f shows the internal architecture of the three-stage amplifier A. The first stage of the amplifier consists of a cascoded input pair (M1-M4) to minimize the Miller effect and thus maximize input impedance, and a bootstrapped load16 (M5-M8, Cbs). The bootstrapped load amplifier architecture was selected due to its ability to provide sufficiently high open-loop gain around the autozeroing frequency, which is essential for accurate closed-loop operation together with effective offset and noise cancellation. Compared to alternatives such as diode-connected load amplifiers or positive feedback configurations, the bootstrapped design offers superior performance by delivering high gain at the autozeroing frequency while maintaining low DC gain and offset, which improves linearity and increases yield. The cascode is replica-biased by the transistors M19-M22. The first stage (M1-M8) is biased in the sub-threshold regime to maximize the efficiency of the amplifier. The second stage of the amplifier consists of two source followers (M10-M13) used to correctly bias the third stage of the amplifier (M14-M18). This third stage shows a gain similar to a diode-connected load amplifier, having the gate of the loads (M16-M17) biased by the voltage Vcmfb, which is generated by the common mode biasing circuit (ACM, M23, M24). The common mode biasing is performed using a replica of the third stage and a common mode feedback amplifier ACM, to keep the source of M23 (and thus of M16/M17) to the common mode reference voltage. ACM is designed using a simple resistive load amplifier. Miller compensation (CM and RM) is used to ensure the stability of the amplifier in buffer configuration. The biasing voltages Vb1, Vb2, and Vb3 are generated using current mirrors and suitable reference currents that are provided off-chip. Implementing a differential to single-ended conversion in unipolar flexible TFT technologies that operate with a relatively large input voltage swing is extremely challenging due to the lack of a complementary transistor. Therefore, in this work the signal is extracted from only one output of the fully differential-amplifier (Fig. 2f), resulting in a 6 dB gain loss. This amplifier is designed to achieve a gain-bandwidth product of at least 20 kHz to correctly operate while autozeroing at 8 kHz (i.e., two times the multiplexing frequency). The input-referred noise level is designed to be less than 25 µVrms. This is verified at design stage by using suitable circuit simulations that utilize the TFT electrical model provided by the foundry17 and its 1/f noise model extracted from dedicated device characterization18. At design stage, the input impedance of the AFE was simulated to be larger than 1 GΩ over all the Process Design Kit Process corners (with optimized biasing for each corner), for supply voltage variations of ±10% from the nominal value of 3.5 V and over the temperature range (0–35 °C). Furthermore, a Monte Carlo simulation of the schematic view at constant biasing and including mismatch has been performed, resulting in a mean input impedance of 590 MΩ and a standard deviation of 370 MΩ. Finally, the switches in the system are designed with two dummy transistors to counteract charge injection13.

Electrical measurement results

The proposed AFE circuit is manufactured with a unipolar a-IGZO TFT technology17 on a 30 µm-thick flexible substrate based on polyimide. The circuit supports up to 4 electrodes, occupies a total area of 3.76 mm2, (0.88 mm2/channel), and consumes a total power of 221 µW (55.3 µW/channel) from a supply of 3.5 V. The micrograph of the AFE is shown in Fig. 2e. The measured in-band transfer of the AFE is equal to one (within the accuracy defined by the noise) due to the direct connection from input to output during the multiplexing phase. The first characterization of the AFE aims to determine the cross-talk between two successive channels. A 50 Hz input tone of 150 mV peak is applied to channel 1 and the outputs of channels 1 and 2 recorded. The measurement results shown in Fig. 3a reveal that no spurs emerge from the noise floor of channel 2. Therefore, the cross-talk between two consecutive channels is <−90 dBc.

a Measurement of the cross-talk of two consecutive channels. b Measurement of the noise in all channels together, and separately. c Histogram of the measured output-referred offset of 33 samples of the buffer in the AFE. d Histogram of the measured input-referred integrated noise of 7 samples of the AFE. e Time-domain measurement of the AFE where the channel 1 input is connected to a 90 Hz sine wave and the other inputs are grounded (f) Measurement of the input impedance of the AFE and a first-order R-C fit of the data. g Comparison table with the state-of-the-art in flexible electronics for biopotential readout systems.

Next, the Input-Referred Noise voltage spectral density of the aggregated AFEs output has been measured, while multiplexing at a 4 kHz frequency and autozeroing at 8 kHz. The IRN of the four input channels has then been derived from this measurement. The spectrum of the aggregated signal (labeled as “mux output”) and the four demultiplexed channels are shown in Fig. 3b. The output spectral density of the aggregated signal is halved compared to the individual channels because the same total power is distributed over a wider bandwidth (4 kHz compared to 1 kHz per channel). Interestingly, even though autozeroing is used in the AFE, a clear 1/f noise trend can be noticed at frequencies <50 Hz. This can be caused either by the 1/f noise of the switches (as the multiplexer is not autozeroed) or by the limited effectiveness of the autozeroing due to the finite midband gain of the amplifier A, or leakage of the capacitor Caz. The total integrated IRN of the front-end per channel is measured to be 22 µVrms over a 500 Hz bandwidth, which is sufficiently low to obtain an angular control accuracy better than 20 degrees RMSE in the target applications. With these results, the AFE attains a Noise Efficiency Factor (NEF) of 150 and a Power Efficiency Factor (PEF) of 7.9 ∙ 104. The IRN is furthermore evaluated for 8 different channels taken from 2 separate multiplexers. One out of the 8 channels did not meet the target specifications ( < 60µVrms) and therefore has not been included in the distribution (Fig. 3d). The histogram of the results (Fig. 3d) reveals a mean value of µn=26 µVrms and a standard deviation of σn = 5.4µVrms.

A low input offset is required to ensure the correct functionality of the AFE circuit. As the offset strongly depends on the matching, which is notably worse in a-IGZO TFTs than Silicon transistors, it is important to characterize this parameter over a statistically meaningful sample population. Therefore, 36 channels taken from 9 separate multiplexers have been tested by supplying an input DC signal of 1.4 V (i.e. the input common-mode). Out of the 36 samples, three channels did not perform according to specifications and were therefore removed. The input offset was calculated by subtracting the output voltage in the pre-charging phase from the output voltage in the multiplexing phase (which is equal to the input voltage of the AFE). The histogram of the results (Fig. 3c) reveals a mean value of only µo = 203µV, proving that the AFE operates correctly, and a standard deviation of σo‘=4.6 mV, which is the best AFE input offset performance reported in flexible electronics to date8.

The correct functionality of the AFE multiplexing is shown in Fig. 3e. Here a sine wave of 50 mVrms at 90 Hz has been set as an input of one channel, while the other input channels were grounded.

Finally, the AFE input impedance has been measured to be 841MΩ while using an input tone at 50 Hz (i.e., the typical frequency used to characterize the input impedance of biomedical front-ends). With a similar approach, the input impedance has been characterized over frequency (Fig. 3f). At relatively low frequencies, the recorded impedance level fluctuates due to interference and noise in the measurement setup. For this reason, an average value of ~720 MΩ has been extracted for the input impedance within the frequency range 1–50 Hz.

Prosthesis control

After digitizing the sEMG signals, these data are post-processed and used as input for the prosthesis control (see Fig. 1a). The flow of this process is shown in Fig. 4a. First, the sEMG signals are converted into normalized linear envelopes, by band-pass filtering (with a 40 Hz–200 Hz frequency band), notch filtering (at 50 Hz and its harmonics), full-wave rectifying and low-pass filtering (with a 2 Hz cut-off frequency). The resulting envelope is normalized and further processed via a non-linear transfer function to yield muscle activations. Next, these muscle activations are used as inputs for the musculotendon model in order to estimate the force \({{\rm{F}}}_{{\rm{mt}}}\) exerted by each muscle-tendon unit m. Afterwards, these forces are used as inputs for the musculoskeletal model, which predicts the torque of the elbow joint \({{\rm{T}}}_{{\rm{ref}}}\) based on the forces and the moment arms of the muscles \({\rm{M}}{{\rm{A}}}_{{\rm{m}}}\). This torque is considered as the reference for a torque-controlled prosthesis model. The output torque induces a change in the angle θ between prosthesis and imaginary extension of the lower arm as depicted in Fig. 4b. This angle is used for feedback to the musculotendon and musculoskeletal models, thereby adjusting muscle-tendon kinematics (i.e., length and moment arm)19.

To obtain a value for the muscle activation, first the sEMG signals measured at the biceps brachii, triceps brachii and brachialis are individually filtered using a band-pass and notch filters to eliminate out-of-band noise and powerline interference. Next, linear envelopes are extracted from the filtered signals, which are normalized with respect to the measured value at maximum voluntary contraction (MVC). The normalized sEMG signals u are transformed into muscle activations a using

Where the scalar A is the nonlinearity factor, taking into account the non-linearity between normalized EMG linear envelope amplitude and muscle twitch response20. By adjusting A, the influence of low and high amplitude sEMG signals can be altered, with A = −3 indicating highly non-linear mapping and A approaching zero indicating linear mapping.

To convert muscle activation into the resulting muscle-tendon force, a Hill-type musculotendon-model with force-length-velocity relationships expressed in closed-form equations (presented by Pau et al. 21) as depicted in Fig. 4c is used. The total force \({{\rm{F}}}_{{\rm{M}}}\) generated by the muscle-element within a muscle-tendon unit is expressed as the sum of the contractile force \({F}_{{CE}}\), the passive elastic force \({F}_{{PE}}\), and the force of the dampening element \({F}_{{VE}}\).

The contractile force \({{\rm{F}}}_{{\rm{CE}}}\) is a function of muscle activation a, Eq. (1) as well as normalized muscle active force-length fl and force-velocity relationship fv. The equation for FCE is given by

where fl and fv are a function of normalized muscle length (lm) and contraction velocity (vm) and are normalized by the muscle maximal isometric force \({{\rm{F}}}_{{\rm{Max}}}\). fl is calculated according to the Thelen model22 with the equation

where \({{\rm{l}}}_{{\rm{mopt}}}\) is the muscle optimal fiber length used to normalize lm and γ is a shape factor. The Rosen model20 provides an equation for sigmoidal force-velocity relationship:

where \({{\rm{v}}}_{{\rm{n}}}\) is the normalized muscle fiber contraction velocity given by

The maximal muscle fiber contraction velocity \({{\rm{v}}}_{{\rm{m\_}}\max }\) can be approximated by \(10\cdot {{\rm{l}}}_{{\rm{mopt}}}/s\) modelling a fast-twitch muscle with maximal velocity equal to ten optimal fiber length per second21. The muscle parallel passive elastic force FPE is the resistive force counteracting the lengthening of the muscle fiber. A closed-form equation for the passive elastic force is presented by Cavallaro et al. 20 which is given by

where \({{\rm{C}}}_{{\rm{pass}}}\) is a tuning variable to adjust the influence of the passive elastic force. A parallel damping element \({F}_{{VE}}\) was added to the muscle force-length relationship to avoid singularities in the model when the muscle operates with zero activations:

where \({{\rm{\beta }}}_{{\rm{m}}}\) is the damping coefficient of the muscle. The total force produced by the muscle-tendon unit is given by

where \({\alpha }_{p}\) expresses the orientation of the muscle element relative to the tendon line of action, which in this study was set to 0 rad to approximate the fusiform arm musculature.

In this paper, the commonly used musculoskeletal model presented by Pau et al. 21 is expanded by including the brachialis muscle. With this addition, the flexion force is divided over two different moment arms, which results in a more accurate prediction of the total moment of the elbow joint. The moment caused by a specific muscle group \({{\rm{M}}}_{{\rm{m}}}\) is given by

where \({{\rm{K}}}_{{\rm{m}}}\) is a tuning variable to scale the influence of the corresponding muscle group, \({\rm{M}}{{\rm{A}}}_{{\rm{m}}}\) is the variable moment arm of the corresponding muscle group calculated from the trigonometry as shown in Fig. 4b, and \({F}_{m}\) is the total force of a specific muscle group calculated with the Musculotendon model.

Similar to the musculotendon model, the musculoskeletal model contains a viscous component that dampens change in joint angle θ. This viscous moment is given by

where β is the damping coefficient of the elbow. The total moment \({{\rm{M}}}_{{\rm{Tot}}}\) about the elbow calculated according to the improved model is given by

where \({{\rm{M}}}_{{\rm{g}}}\) is the moment caused by gravity and O is an offset that is used as a tuning variable. Suffixes Bi, Bra, and Tri are used to indicate the moments caused by the biceps, brachialis, and triceps respectively.

The combination of the musculotendon model and Musculoskeletal model provides a description of the kinematics of the elbow joint based on physiological constants and tuning variables. The tuning variables are chosen by minimizing the RMSE of the predicted angle based on data obtained with the golden standard measurement setup further described in the methods section.

The dynamics of the elbow prosthesis is simulated using a Simulink model. This prosthesis model consists of a mechanical joint model and a prosthesis dynamic model. The mechanical joint is simulated using the Compliant Joint Toolbox23. This toolbox contains options to simulate distortions like various forms of friction and torque ripple. These options are used to create a realistic representation of an elbow prosthesis. The output torque Tout can be used to calculate the angular acceleration \(\ddot{{\rm{\theta }}}\) of the digital prosthesis using

where I is the moment of inertia. By integrating this angular acceleration, the angular velocity and joint angle of the virtual prosthesis can be obtained. This conversion from torque to joint angle and angular velocity is referred to as the prosthesis dynamics model in Fig. 4a. The moment of inertia considered in this model is an estimation of the moment of inertia of an elbow prosthesis about the elbow pivot.

The output of the musculoskeletal model \({M}_{{tot}}\) is used as the reference torque TREF for a torque-controlled prosthesis. This prosthesis is controlled using a passivity-based controller based on the structure presented by Albu-Schäffer et al. 24. The joint angle θ that is resultant from the torque applied by the prostheses \({T}_{{out}}\) acts as a feedback for the musculotendon and musculoskeletal models as depicted in Fig. 4a.

In-vivo system validation

A prototype of the full system has been implemented as shown in Fig. 1b–d. The electrodes are attached to an informed and consenting able-bodied participant (age: 25, weight: 72 kg, sex: male) with no history of musculoskeletal injuries, specifically at the biceps, triceps, brachialis, and epicondyle. The electrode at the epicondyle was used as a reference. The proposed flexible PCB integrates all the electronic components and allows the system to be wrapped around the upper arm like a band. The participant was then asked to perform two sets of tasks. The first task is to move the lower arm at the frequency of a metronome, and the second task is to move the arm in a slow and fast manner repeatedly. The details of the tasks are explained later in the section.

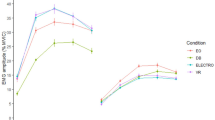

To validate the system compatibility with both wet and dry electrodes, a series of tensing and relaxing exercises of the biceps are conducted, guided by a metronome set at 30 beats per minute (BPM). The experiments utilize both a wet electrode and a BQEL1 ringtrode dry electrode25. The power spectral density analysis (Fig. 5a) reveals similar signal-to-noise ratios for both the dry and wet electrodes. Additionally, the time domain signals (Fig. 5b) reveal that with both electrodes, the movement of the lower arm can be tracked. Note that the signal waveforms are not the same due to the two measurements being performed at different instances in time. To benchmark the performance of our system, we have used a REFA amplifier, which exclusively works with low-impedance electrodes, to record the reference dataset. Therefore, to provide a fair comparison, all the subsequent measurements are performed using wet electrodes.

a Normalized measured spectral density of the filtered signals at 30BPM with wet and dry electrodes. b Normalized measured envelope of the time domain signal for a 30BPM motion with wet and dry electrodes. Note that the two measurements were performed at two different instances in time. c Measured filtered sEMG signal. d Measured prosthesis torque. e Measured prosthesis angle. f Measured prosthesis velocity. g Histogram of measurements of the period distribution between peak angles for different metronome frequencies.

The ability of the total system to drive a prosthesis with a periodically changing angle is shown by the test subject flexing and extending his arm guided by a metronome. The sEMG signals sensed from the biceps and recorded at the output of the AFE circuit and its envelope for a 60 BPM metronome are shown in Fig. 5c. The intensity of the envelope signal is digitally processed using Eq. (1)-(12) to give an indication of the reference torque to be applied, which is shown in Fig. 5d. The low-level controller enables the prosthesis to track this reference torque with an RMSE of 0.22 Nm. Finally, the angle and velocity of the prosthesis are shown in Fig. 5e, f respectively. This measurement has been repeated for BPMs of 30 to 90 with steps of 15 BPM. The histogram showing the time between measured beats is shown in Fig. 5g. The average error for all BPMs except 75 BPM, which suffered from multiple outliers, is 2 ms with a standard deviation of 16 ms, showing good correlation between the prothesis output and the movement of the test subject.

The main performance indicator of the system is the accuracy of the angle prediction. For this measurement, a gyroscope is used to the test subject’s lower arm to measure the input angle θ (Fig. 4b). The subject was then asked to perform a series of movements as shown in Fig. 6a. In a time-span of 60 s, the subject was asked to perform two fast extension and flexion movements and two slow extension and flexion movements. The resulting angles are shown in Fig. 6b. Furthermore, a video showing the measurement protocol and the resulting movement of the prosthesis model is provided in the Supplementary Materials. A REFA amplifier (TMSi11) is used as a golden standard to provide a comparison (Fig. 6c). The results from the flexible measurement setup do show an increased RMSE of 20.8 degrees compared to the REFA amplifier, which achieves an RMSE of 11.5 degrees. This is due to the lower noise of the REFA amplifier, which is made possible at the cost of higher power consumption. The REFA amplifier, however, is not portable, while the proposed wearable setup is. By including an extra electrode located on the brachialis muscle the RMSE is decreased by approximately 30% compared to the model presented by Pau et al. 21 implemented on the same dataset.

a Schematic representation of the movements done by the subject for prosthesis angle accuracy measurements. b, c Prosthesis angle and angular velocity alternating between fast and slow movements using the improved musculoskeletal model ((b) wearable setup, (c) REFA golden-standard setup). d Comparison table with the state-of-the-art in sEMG driven model-based elbow joint angle predictors.

Discussion

In Fig. 3f, the performance of the proposed AFE circuit is compared with relevant state-of-the-art in flexible electronics. Compared to existing frontends for EMG signals, our AFE achieves the lowest noise floor and power consumption, and the highest input impedance. TFT-based frontends for different biosignal sensing applications have also been reported in literature by Moy et al. 26, Zulqarnain et al. 27 and Van Oosterhout et al. 13. These works achieve better noise floor, however, they exhibit 4-5x less bandwidth, making them incompatible with EMG signal sensing. Furthermore, none of these works achieve an input impedance larger than 25 MΩ around 50 Hz, which is about 30x smaller than what reported here, and insufficient to enable the use of dry electrodes.

The performance of the proposed AFE enabled the construction, for the first time in literature, of a wearable device for sEMG-based prosthesis control based on flexible electronics. The accuracy of the predicted angle is compared to other works (Koo et al. 28, Pau et al. 21, Pang et al. 29, Han et al. 30, and Li et al.31) using sEMG driven model-based elbow joint angle predictors in Fig. 6d. None of these works, however, make use of a lightweight wearable device for the sEMG sensing part of the system: they rather rely on Silicon-based rigid solutions. Due to the realistic modeling employed in our system, we expect similar performance when transitioning from the virtual prosthesis used in this study to a physical device.

Finally, increasing the number of channels can substantially enhance the capabilities of flexible electronics in prosthetic control applications. In our design, each channel occupies 0.88 mm², which sets the upper bound for electrode density when electrodes are monolithically integrated directly on top of the electronics on the flexible substrate8. Importantly, even high-density EMG systems typically employ inter-electrode pitches ranging from 1 mm to 8 mm. As a result, the compact footprint of the AFE per channel does not impose a constraint, even when paired with such dense electrode arrays. However, in the technology used for this work, the maximum area of the flexible circuit that the foundry provides is 4.62 cm2. Assuming to assemble an array of flexible AFEs with a larger patch containing the electrodes, the area needed to connect the AFE input to the electrode patch using a pad and our ACE process is at least 0.25 mm2. This would result in an absolute maximum number of channels of 408. This estimation neglects the connection pads for the outputs, supplies and clocks, as well as the area taken up by routing the channels.

To conclude, this work demonstrates for the first time a wearable device for sEMG sensing, suitable for prosthesis control and built using integrating flexible electronics. The wearable patch embeds a multiplexed analog front-end designed with a-IGZO TFTs that combines pre-charging with autozeroing techniques to reduce low-frequency noise and offset, without detrimentally affecting the input impedance. Thanks to these circuit innovations, the proposed a-IGZO AFE enables the use of dry electrodes for sEMG sensing, which has the potential to improve the comfort and usability of the solution significantly. A prototype built using this wearable patch has been complemented with a simple musculoskeletal model. This system can track flexion and extension movements performed by a test subject following a metronome ranging from 30 to 90 BPM, using both wet and dry electrodes. The tracking accuracy time is within tens of milliseconds. The rms angle error measured in a series of movements is approximately 20 degrees. This work lays a foundation for future ultra-thin, fully integrated prosthetics, offering the potential for seamless, and conformable interfaces to the human body.

Methods

The research performed in this manuscript has been approved by the Ethics Review Board of Eindhoven University of Technology under ERB number: ERB2024EE1. The human participant involved provided informed consent prior to participation.

Golden standard measurements using the REFA amplifier

To obtain measurements with a state-of-the-art golden standard system, the REFA amplifier by TMSi is used to acquire the EMG signals. The electrodes used and their placement are identical to the tests done with the flexible system. The test subject is asked to perform the prosthesis angle accuracy movements depicted in Fig. 6b. The data obtained by the REFA amplifier are processed by the prosthesis control system, generating a prosthesis angle that can be compared to the angles predicted by the flexible-based system in the same experiment. All model parameters in these experiments are identical for the REFA amplifier and the flexible-based system except for the parameters contributing to the transformation from sEMG signal to muscle activation a.

Anisotropic conductive epoxy bonding

To connect the flexible electronics front-end to the flexible PCB, the IQ-BOND 5976 anisotropic conductive epoxy (ACE) is used. A flip-chip machine is used for the bonding process, heating the ACE to 110 degrees Celsius for 25 min. Using this process, the 51 pads of the AFE are connected to the flexible PCB. This connection acts as a strong adhesive while still allowing mechanical flexibility.

Flexible printed circuit

To integrate the AFE into a wearable setup, a flexible printed circuit (FPC) is developed, as shown in Fig. 1b. The components are mounted on a segmented band that can wrap around the subjects upper arm. Electrodes are connected to this band using serpentine arms that enable multiple electrode placements. The off-the-shelf components on this FPC include adjustable low-dropout regulators (LDOs, TPS715) for the generation of bias points for the AFE, an MCU (ESP32-WROOM-32E) for clock signal generation, and a buffer to drive the PXI ADC (see Electrical characterization setup). The output signals of this buffer are digitized to be used for prosthesis control. By integrating the AFE into the wearable setup new noise sources are introduced that increase the total input-referred noise of the electronics to 56µVRMS. One likely additional source of noise is that the PCB design did not include separate ground planes for the AFE and the microcontroller. This can increase the interference caused by switching in the microcontroller towards the sensitive AFE.

Electrical characterization setup

The AFE electrical measurements were performed using a PXI-9527 ADC (at 24-bits with a sampling speed of 200 kHz) connected to the output of the multiplexer. The crosstalk is measured by exciting one channel of the multiplexer with a 150 mV peak sine wave with a frequency of 50 Hz, as is the standard in the field. Afterwards, the output was digitally demultiplexed and the FFT of the different channels were averaged over 50 samples of 1 second. The noise was calculated by setting all input channels to the reference common mode of 1.4 V and measuring the output channel through the PXI, averaging 50 samples of 1 second, and sampling at 4 kHz. To obtain the noise of the separated channels, the channels were digitally demultiplexed. The total integrated noise was then calculated over the bandwidth of 500 Hz. To measure the offset, a 1.4 V input was set to 36 different channels. The offset was then measured as the difference between the output in the switch phase (\({\phi }_{m}\)) and the pre-charging phase (\({\phi }_{p}\)). For three channels, the buffer did not perform within the set specifications ( < 60µVrms noise), and therefore, these three channels were not taken into account for the statistics. Finally, to characterize the AFE input impedance, the voltage drop is measured over a 100 kΩ resistor connected in series with the input of the AFE. This voltage is sensed using an instrumentation amplifier (INA217) and a Dynamic Signal Analyzer (Keysight 35665A), and converted to the corresponding input impedance.

Human research participants

A single healthy volunteer (age: 25, weight: 72 kg, sex: male) participated in the EMG recordings. Prior to the experiment, the participant was provided with comprehensive information regarding the study, including its objectives, procedures, potential risks, and benefits. The participant reviewed relevant background materials and demonstrated a clear understanding of the study’s scope. Informed consent was obtained, with explicit acknowledgment that participation was voluntary and could be withdrawn at any time without consequence. The participant also consented to the publication of anonymized data in a scientific journal. Ethical approval for this study was granted by the Ethics Review Board of Eindhoven University of Technology (ERB number: ERB2024EE1), ensuring compliance with standards for research involving human subjects.

Data availability

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Code availability

The code that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

References

McDonald, C. L., Westcott-McCoy, S., Weaver, M. R., Haagsma, J. & Kartin, D. Global prevalence of traumatic non-fatal limb amputation. Prosthet. Orthot. Int 45, 105–114 (2021).

Sartori, M., Durandau, G., Došen, S. & Farina, D. Robust simultaneous myoelectric control of multiple degrees of freedom in wrist-hand prostheses by real-time neuromusculoskeletal modeling. J. Neural Eng. 15, 066026 (2018).

Farina, D. et al. Man/machine interface based on the discharge timings of spinal motor neurons after targeted muscle reinnervation. Nat. Biomed. Eng. 1, 0025 (2017).

Song, H. et al. Continuous neural control of a bionic limb restores biomimetic gait after amputation. Nat. Med 30, 2010–2019 (2024).

Yadav, D. & Veer, K. Recent trends and challenges of surface electromyography in prosthetic applications. Biomed. Eng. Lett. 13, 353–373 (2023).

Londoño-Ramírez, H. et al. Multiplexed Surface Electrode Arrays Based on Metal Oxide Thin-Film Electronics for High-Resolution Cortical Mapping. Adv. Sci. https://doi.org/10.1002/advs.202308507. (2023)

Garripoli, C., Abdinia, S., van der Steen, J.-L. J. P., Gelinck, G. H. & Cantatore, E. A Fully Integrated 11.2-mm 2 a-IGZO EMG Front-End Circuit on Flexible Substrate Achieving Up to 41-dB SNR and 29-M$\Omega$ Input Impedance. IEEE Solid State Circuits Lett. 1, 142–145 (2018).

Genco, E. et al. An EMG Interface Comprising a Flexible a-IGZO Active Electrode Matrix and a 65-nm CMOS IC. IEEE J. Solid-State Circuits https://doi.org/10.1109/JSSC.2023.3274709. (2023)

van Oosterhout, K., Timmermans, M., Fattori, M. & Cantatore, E. A 250MΩ Input Impedance a-IGZO Front-End for Biosignal Acquisition from Non-Contact Electrodes. In 2024 IEEE International Symposium on Circuits and Systems (ISCAS) 1–5 (IEEE. https://doi.org/10.1109/ISCAS58744.2024.10558081. 2024)

Raynauld, J.-P. & Laviolette, J. R. The silver-silver chloride electrode: a possible generator of offset voltages and currents. J. Neurosci. Methods 19, 249–255 (1987).

REFA & TMSi - an Artinis Company, the N. www.tmsi.artinis.com.

Chi, Y. M., Jung, T. P. & Cauwenberghs, G. Dry-contact and noncontact biopotential electrodes: Methodological review. IEEE Rev. Biomed. Eng. 3, 106–119 (2010).

van Oosterhout, K. et al. Brain-Computer Interfaces Using Flexible Electronics: An a-IGZO Front-End for Active ECoG Electrodes. Adv. Sci. https://doi.org/10.1002/advs.202408576. (2024)

Hall, D. A., Makinwa, K. A. A. & Jang, T. Quantifying Biomedical Amplifier Efficiency: The noise efficiency factor. IEEE Solid-State Circuits Mag. 15, 28–33 (2023).

Chandrakumar, H. & Markovic, D. A High Dynamic-Range Neural Recording Chopper Amplifier for Simultaneous Neural Recording and Stimulation. IEEE J. Solid-State Circuits 52, 645–656 (2017).

Raval, H. N., Tiwari, S. P., Navan, R. R., Mhaisalkar, S. G. & Rao, V. R. Solution-Processed Bootstrapped Organic Inverters Based on P3HT With a High- $k$ Gate Dielectric Material. IEEE Electron Device Lett. 30, 484–486 (2009).

Pragmatic Semiconductor. https://www.pragmaticsemi.com/.

van Oosterhout, K., Timmermans, M., Fattori, M. & Cantatore, E. Design Trade-offs for Noise Reduction Techniques in Flexible Electronics. In accepted for publication at IFETC 2025.

Pau, J. W. L., Xie, S. S. Q. & Pullan, A. J. Neuromuscular Interfacing: Establishing an EMG-Driven Model for the Human Elbow Joint. IEEE Trans. Biomed. Eng. 59, 2586–2593 (2012).

Cavallaro, E. E., Rosen, J., Perry, J. C. & Burns, S. Real-Time Myoprocessors for a Neural Controlled Powered Exoskeleton Arm. IEEE Trans. Biomed. Eng. 53, 2387–2396 (2006).

Pau, J. W. L., Saini, H., Xie, S. S. Q., Pullan, A. J. & Mallinson, G. An EMG-driven neuromuscular interface for human elbow joint. In 2010 3rd IEEE RAS & EMBS International Conference on Biomedical Robotics and Biomechatronics 156–161 (IEEE, https://doi.org/10.1109/BIOROB.2010.5627758. 2010).

Thelen, D. G. Adjustment of Muscle Mechanics Model Parameters to Simulate Dynamic Contractions in Older Adults. J. Biomech. Eng. 125, 70–77 (2003).

Malzahn, J., Roozing, W. & Tsagarakis, N. The Compliant Joint Toolbox for MATLAB: An Introduction With Examples. IEEE Robot Autom. Mag. 26, 52–63 (2019).

Albu-Schäffer, A., Ott, C. & Hirzinger, G. A Unified Passivity-based Control Framework for Position, Torque and Impedance Control of Flexible Joint Robots. Int J. Rob. Res 26, 23–39 (2007).

MedCaT BV. https://medcat.nl/.

Moy, T. et al. An EEG Acquisition and Biomarker-Extraction System Using Low-Noise-Amplifier and Compressive-Sensing Circuits Based on Flexible, Thin-Film Electronics. IEEE J. Solid-State Circuits 52, 309–321 (2017).

Zulqarnain, M. et al. A flexible ECG patch compatible with NFC RF communication. npj Flex. Electron. 4, 13 (2020).

Koo, T. K. K. & Mak, A. F. T. Feasibility of using EMG driven neuromusculoskeletal model for prediction of dynamic movement of the elbow. J. Electromyogr. Kinesiol. 15, 12–26 (2005).

Pang, M., Guo, S., Huang, Q., Ishihara, H. & Hirata, H. Electromyography-Based Quantitative Representation Method for Upper-Limb Elbow Joint Angle in Sagittal Plane. J. Med Biol. Eng. 35, 165–177 (2015).

Han, J., Ding, Q., Xiong, A. & Zhao, X. A State-Space EMG Model for the Estimation of Continuous Joint Movements. IEEE Trans. Ind. Electron. 62, 4267–4275 (2015).

Li, K., Zhang, J., Liu, X. & Zhang, M. Estimation of continuous elbow joint movement based on human physiological structure. Biomed. Eng. Online 18, 31 (2019).

Acknowledgements

This publication is part of the project Smart-Sense (with project number17608) which is (partly) financed by the Dutch Research Council (NWO).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

K.O. and S.D. are equally credited. The overall research was designed and supervised by E.C.; the circuit design was carried out by K.O.; circuit design reviews were done by K.O., M.T., M.F. and E.C.; Electrical characterization of the electronics was done by K.O.; Noise specification simulations were performed by S.D. and K.O.; Design of the flexible PCB was done by S.D.; The prosthesis control algorithm was made by S.D.; in vivo validation of the electronics has been performed by K.O. and S.D.; K.O. and S.D. wrote the first draft of the manuscript; editing and revision were carried out by K.O., S.D., M.T., M.F., E.C. and M.S.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

van Oosterhout, K., van Diemen, S., Timmermans, M. et al. Flexible circuits for bionic limbs: a high impedance multiplexing front-end for myoelectric control. npj Flex Electron 9, 117 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41528-025-00492-7

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41528-025-00492-7