Abstract

In this work, emerging perovskite-inspired Cu2AgBiI6 (CABI) solar cells were successfully fabricated on flexible substrates, demonstrating that the transition from rigid to flexible materials does not compromise device performance. This underscores the versatility of CABI on two different kinds of substrates. Additionally, to optimize charge extraction, we selected a polymeric hole-transport material (HTM), PPDT2FBT, whose energy levels align with CABI. The PPDT2FBT-based devices outperformed those using the well-known poly(3-hexylthiophene) (P3HT), leading to power conversion efficiencies as high as approximately 0.8%. These results suggest that PPDT2FBT may hold promise as a HTM for use in low-toxicity, perovskite-inspired photovoltaic systems, such as those based on CABI. Furthermore, roll-to-roll processing techniques, crucial for scalable production, were tested. However, controlling the morphology of the active layer remains a significant challenge. These findings represent critical steps toward the large-scale manufacturing and commercialization of flexible, PIM-based solar cells.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

The rapid development of photovoltaic (PV) technology has gained significant attention in recent years due to its potential to revolutionize the renewable energy landscape. Among the various PV technologies, lead halide perovskites (LHPs) have emerged as promising candidates, offering high efficiency, low-cost fabrication, and versatility in a wide range of optoelectronic applications1,2,3. However, the inclusion of lead in traditional perovskite formulations raises environmental and health concerns, especially in indoor environments, necessitating the exploration of lead-free and low-toxicity alternatives4,5,6. In response to these concerns, researchers have turned their focus towards lead-free perovskite-inspired materials (PIMs), with the aim of developing environmentally friendly PV technologies6,7,8,9. Tin (Sn)- and germanium (Ge)-based perovskites and double perovskites, which substitute lead with non-toxic elements such as bismuth (Bi) or silver (Ag), are promising candidates due to their similar electronic properties to lead-based perovskite but with lower toxicity. These materials offer improved stability and environmental safety while retaining desirable optoelectronic properties, making them potential candidates for applications like solar cells and photodetectors. Among the PIMs, Sn-based perovskites have gained particular prominence, achieving power conversion efficiencies (PCE) exceeding 14%6. However, these perovskites face significant instability in air. For instance, MASnI3 decomposes within seconds due to the undesirable oxidation of Sn2+ to Sn4+10,11,12. In contrast, bismuth (Bi)- and antimony (Sb)-based pnictohalide compounds are generally air-stable due to the intrinsic oxidative stability of the pnictogen 3+ cations7,13. In addition, pnictohalide compounds have band gaps within the optimal range of 1.9–2.0 eV for indoor PVs (IPVs), making them highly suitable candidates for IPV applications6,9. In our lifecycle assessment study of various pnictohalide PIMs, we demonstrated that these perovskite-inspired absorbers are not only environmentally friendly at the material level but also have the potential to be a sustainable IPV technology14. Research on pnictohalide PIMs for IPVs has just begun and only a few materials have been studied for IPVs. Among them, Cu2AgBiI6 (CABI) has garnered considerable amount of interest. The initial PCE of CABI has improved from 0.438 to 2.39%15 under 1 sun illumination and reached 5.52%9 under 1000 lux by optimizing the mesoporous TiO2 layer. Alloying Sb3+ with Bi3+ in CABI further reduced defect density, achieving a PCE of 9.53%16 at 1000 lux illumination, nearly doubling the performance of unalloyed devices. Additionally, the wide bandgap of CABI makes it suitable for tandem PV applications as a top cell, with predicted PCEs reaching up to 30%8. With excellent stability under air and sunlight soaking8,9, and the potential to achieve high PCEs in both single- and multijunction PV applications4,8,9, CABI is positioned to be an attractive low-toxicity absorber. So far, the well-known hole-transport materials (HTMs) used in high-performing LHP solar cells have also been directly adopted for lead-free PIM devices17. However, the ad-hoc selection of the HTLs with respect to the absorber is necessary to guarantee effective charge extraction and transport, thereby maximizing overall device performance. Yet, this aspect is largely overlooked in the literature. Polymers such as poly(3-hexylthiophene) (P3HT), poly[bis(4-phenyl)(2,4,6-trimethylphenyl)amine (PTAA), poly(N,N′-bis(4-butylphenyl)-N,N′-bis(phenyl)benzidine) (poly-TPD) are often used in LHP solar cells and are the promising candidates due to their favorable electronic properties, solution processability at low temperatures, and mechanical flexibility18,19,20,21,22,23. However, the optimized HTMs for LHP devices are not necessarily ideal for lead-free PIMs.

In this study, we chose two polymeric HTMs for CABI-based PVs, namely poly[(2,5-bis(2-hexyldecyloxy) phenylene)-alt-(5,6-difluoro-4,7-di(thiophen-2-yl)benzo[c]-1,2,5thiadiazole (PPDT2FBT) and P3HT. While P3HT has been earlier employed in CABI and other PIM devices24, PPDT2FBT has never been tested in the context of PIM solar cells but only for organic25,26 and lead-based perovskite solar cells27,28. One of the key benefits of PPDT2FBT over commonly used polymer-based HTMs such as P3HT, PTAA, and poly TPD is its high hole mobility27,29, which facilitates efficient charge extraction from the active layer. This high mobility enhances charge extraction process, thereby improving overall performance of the device.

So far, CABI films have been deposited only on rigid substrate via spin coating or thermal evaporation8,9,13,30,31. The properties of this material allow for solution processing, opening avenue for the use of flexible substrates and scalable deposition techniques which have not been studied before. The use of flexible substrate is particularly useful for Internet of Things (IoT) applications, where lightweight, bendable, and durable electronics are required4,6,32. Fabricating CABI films on flexible substrates could enable the development of wearable or portable energy-harvesting devices, contributing to the growth of self-powered IoT systems. These flexible solar cells can be incorporated into various surfaces and products, making them ideal for emerging IoT technologies that demand adaptable and scalable energy solutions33.

Considering the advantages of CABI for PV applications, processing through large-scale fabrication is an essential step to achieve industrial goals, just as with any PV technology34. As far as halide PIMs are concerned, to our knowledge, only one report exists. Xu et al. recently demonstrated solar module fabrication for an organic-inorganic antimony halide PIM by joining a few individual cells7. However, the module, which was a few square centimeters in size, was fabricated on rigid glass substrates. No large-scale PIM solar cell device fabrication or PIM layer processing using scalable techniques on flexible substrates has been achieved. Solution processing methods, such as slot-die coating and gravure printing, offer scalability and compatibility with flexible substrates, making them attractive for large-scale production35,36. It should be noted that achieving continuous, pinhole-free film morphologies for PIMs through simple solution processes like spin-coating is quite challenging. This difficulty arises primarily from uncontrolled crystallization dynamics, which have not been as thoroughly addressed as in the case of LHPs37. Therefore, achieving uniform film coverage and controlling crystallization dynamics during the large-scale solution processing poses additional challenges. These challenges lead to variations in film morphology and consequently the device performance.

In this study, we successfully apply various lab-scale and large-scale solution processing deposition techniques, including spin coating, slot-die coating, and gravure printing for fabricating CABI thin films with area of 8 cm2 and devices of 25 mm2. Our primary focus is on their impact on the film morphology and the device performance of CABI. As seen in previous studies, the crystallization of CABI is a sensitive process8,9,13,15,31, which leads to variations in film quality between different methods. Further development of the ink is necessary to improve film quality and achieve higher cell efficiencies. In this study, for the first time, CABI devices are fabricated on flexible substrate, and it was observed that the efficiency remained almost the same compared to conventional rigid substrates. Notably, PPDT2FBT—a polymer-based hole transport material—has been applied to lead-free CABI solar cells, achieving marginally higher efficiency than the typically employed P3HT. This choice was driven by its energy level compatibility with CABI, ensuring improved charge extraction performance.

Results

Cu2AgBiI6 film preparation on glass and PET substrates

In order to investigate the feasibility of deposition on flexible substrates, CABI films were prepared on two different substrates, glass and PET, using spin coating as the deposition method. The film thicknesses were controlled by using the same spin coating method to ensure comparability. The as-prepared films were examined using XRD, UV-Vis spectroscopy, and scanning electron microscopy (SEM).

Figure 1a shows the experimental XRD pattern of CABI samples on both glass and rigid substrates. The XRD patterns were assigned to the R3-m space group based on comparison with standard diffraction patterns previously published for Cu₂AgBiI68,9. Diffraction peaks at approximately 12.7°, 24.5°, 25.3°, 29.4°, and 41.7° matched the (003), (101), (012), (104), and (110) planes reported in these references (Fig. 1a). These suggest that CABI samples with high phase purity crystallized in the R3-m space group, featuring a complex structure of alternating layers that form a network of octahedral and tetrahedral sites, created by the cubic close-packed iodide sublattice8.

However, we observed slight shifts—about ±0.5°—in the peaks at higher diffraction angles (>42°) compared to the reference pattern, while the lower-angle peaks (10–40°) align well with the standard. The cause of these high-angle shifts is not yet fully understood. One likely explanation is the presence of local crystal strain38, potentially arising from a high density of point defects found in wide-bandgap CABI16,39. A more detailed investigation using advanced XRD techniques and complementary structural analyses will be necessary to clarify this behavior.

The absorption spectra were recorded using a UV-Vis spectrophotometer over the wavelength range of 400–800 nm. The baseline correction was performed to account for the substrate contributions. The UV-Vis absorption spectra of CABI films demonstrate similar absorption features and are in line with what has been reported earlier for polycrystalline CABI films9,13. Both films show strong absorption in the visible region. For the film on glass (Fig. 1b), the absorption onset around 670 nm and two peaks appear at around 415 and 580 nm. The peak at 415-420 nm, which is typically found in CABI thin film samples, has been assigned to either AgI, BiI3, Cu2BiI5, or CuI-rich impurities9,31 or the source of carrier self-trapping in CABI40,41. The PET-based film exhibited a similar absorption profile, albeit with slightly lower absolute absorbance across the spectrum. This may suggest minor variations in the thickness, crystallinity, or surface roughness between the two films. The optical bandgap energies of the CABI samples were determined using Tauc plots, as shown in Fig. S1. The bandgap energies were estimated by extrapolating the linear region of the (αhν)n versus hν plots, with n = 2 corresponding to a direct bandgap8. The calculated bandgap energies were 1.94 eV and 1.97 eV for spin-coated CABI films on glass/ITO/SnO2 and PET/ITO/SnO2 substrates, respectively. These bandgap energies are in close agreement with previous reports9,42.

The morphology of the CABI films was characterized using SEM, while surface roughness was quantified using white light interferometry. Figure 2 presents SEM images that closely examine the surface morphology of CABI films on various substrates, revealing features that directly correlate with their solar cell performance. The thicknesses obtained were 250 ± 11 nm and 250 ± 14 nm on rigid and flexible subsrates, respectively. General issue with CABI is morphology due to low crystallinity and phase heterogeneity that hinders the device performance8,9,13. SEM images reveal that both CABI films deposited on glass and PET substrates exhibit a non-continuous surface morphology with pinholes and notable surface roughness as shown in Fig. 2a, b, respectively. The CABI film on the glass substrate shows a relatively uneven surface with roughness of 30 ± 4 nm as the crystal domains are not fully connected. The surface inspection suggest that the films remain rough and porous throughout the film. Despite these imperfections, the overall film coverage is more uniform compared to the PET-based film. The CABI film on the PET substrate exhibits a less uniform or less favorable surface morphology compared to the one on glass substrate. The surface is highly irregular, exhibiting two distinct structural features, which result in higher surface roughness of 60 ± 18 nm compared to 30 ± 4 nm for the glass/CABI samples. While darker area looks dense and uniform, the gray area appeared to be porous. This heterogeneous appearance contributes to a less compact film structure. The surface roughness for various CABI samples presented in this study are presented in Table S1. While both substrates result in CABI films with moderate surface morphology, the glass-based sample demonstrates slightly better film quality. The more uniform surface contributes to a somewhat denser and more coherent film structure on glass. One possible reason for the lower film quality on the flexible substrate is that the substrate was slightly bent and did not have uniform contact with the hot plate during annealing. As a result, heat transfer was uneven, leading to inconsistent solvent evaporation and CABI crystallization, which ultimately resulted in slightly reduced film quality.

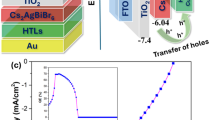

Rigid and flexible CABI solar cells

To investigate whether the differences in film morphology of CABI samples on glass and flexible substrates affect their PV performance, we fabricated corresponding devices with a device architecture of glass or PET/ITO/SnO2/CABI/PPDT2FBT/Au. The device architectures are illustrated in Fig. 3a. We ensured the same fabrication conditions for both types of devices. The current density-voltage (J-V)-curves for CABI devices on both substrates were measured under simulated sunlight (AM 1.5 G), and those of the best performing devices are shown in Fig. 3b. The key parameters derived from the J-V curves, such as open-circuit voltage (VOC), short-circuit current density (JSC), fill factor (FF), and power conversion efficiency (PCE), are summarized in Table 1.

The forward J-V-curves indicate that CABI devices fabricated on PET and glass substrates exhibit nearly identical solar cell performance. The statistical distributions of PV parameters are shown in Fig. S2. The champion devices yielded a PCE of approximately 0.8%. Although the PCE of 0.77% (champion device) achieved in this work is lower than the record PCE of 2.39% reported for CABI solar cells15, those higher efficiencies were obtained using mesoscopic architectures with high-temperature-processed TiO₂, which are incompatible with flexible substrates. In contrast, our planar, low-temperature SnO₂-based devices achieve efficiencies that are comparable to, or slightly higher than, existing reports using similar configurations, where PCEs as low as 0.55% have been observed8,42.

The J–V characteristics (Fig. 3b) exhibit noticeable hysteresis between the forward and reverse scans, which is attributed to ion mobility and interfacial carrier trapping at the CABI–transport layer interface13, consistent with previous reports on planar CABI solar cells8,9,42. Figure S3 presents the stabilized power output (SPO) trends, which were used to derive the stabilized PCEs—reaching up to 0.6%. While the VOCs are the same for both the devices, the marginally lower JSC of the PET-CABI devices compared to the glass-CABI. This may be attributed to differences in film morphology and surface roughness of CABI layer between the rigid and flexible devices. Although the FF is higher for PET-CABI devices, the overall device performance of CABI is retained when transitioning from a rigid glass substrate to a flexible PET substrate. This encouraged us the use of roll-to-roll (R2R) deposition methods such as slot-die coating and gravure printing for constructing CABI devices on flexible substrates.

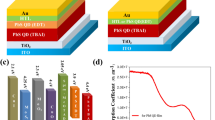

Hole transporting material comparison: PPDT2FBT vs. P3HT

This study investigates two polymeric HTMs, PPDT2FBT and P3HT, in the context of lead-free solar cells. The molecular structures of P3HT and PPDT2FBT are shown in Fig. 4a, b, respectively. The fabrication process of PPDT2FBT and P3HT involved spin coating for the deposition. Both materials were tested in the device architecture Glass/ITO/SnO2/CABI/HTM/Au under standard 1 sun illumination. The thicknesses of the PPDT2FBT and P3HT films are 30 ± 8 and 60 ± 12 nm, respectively. We first conducted UV-Vis absorption measurement. P3HT has strong absorption 400–650 nm, while PPDT2FBT exhibits two absorption regions from 350 to 450 nm and 450 to 720 nm as shown in Fig. 4c.

We compare the use of both P3HT and PPDT2FBT as HTMs in CABI-based devices. The forward and reverse J-V scans are presented in Fig. 4d. Solar cells incorporating PPDT2FBT as the HTM exhibited a slightly higher PCE and JSC than those using P3HT (see Table 2 and Fig. S4). Although the observed performance differences between device configurations are modest, they nonetheless indicate clear and reproducible trends that highlight the suitability of the selected HTL in flexible device architectures.

This slight enhancement is attributed in part to the better energy level alignment of PPDT2FBT with CABI. Specifically, the HOMO level of PPDT2FBT (−5.28 eV) lies approximately 30 meV below the valence band of CABI (−5.25 eV), while P3HT shows a larger offset at −5.00 eV (Fig. S5). Although this alignment suggests more favorable hole extraction for PPDT2FBT, with the small 30 meV barrier is not expected to significantly hinder charge transfer under operational conditions. It also does not lead to an observable Voc improvement, likely due to non-ideal interface quality and interfacial recombination dominating Voc behavior in both cases. Consistent with this, both devices exhibit comparable VOCs (0.46 V). Additionally, the higher hole mobility of PPDT2FBT (7.3 × 10−3 cm2/V s)27 compared to P3HT (1.0 × 10−4 cm2/V s)29 may contribute to the slightly increased JSC. Overall, the similar performance metrics suggest that while PPDT2FBT is a promising HTM for CABI devices, the observed differences are modest. Accordingly, PPDT2FBT was used for the remainder of the device studies presented in this work.

Since both PPDT2FBT and P3HT are relatively strong absorbers in the visible range (Fig. 4c), and the overall device photocurrents and efficiencies are modest, we examined whether the HTMs might contribute to photocurrent generation. To assess this, we compared the normalized external quantum efficiency (EQE) spectra of devices using each HTM with the absorption spectrum of the CABI layer (Fig. S6). Despite their distinct absorption profiles, the EQE spectra for both devices are nearly identical and closely follow the shape of the CABI absorption spectrum across the 400–650 nm range. Notably, the characteristic peak near 420 nm—a signature of CABI—is faithfully reproduced in both EQE curves. If either HTM contributed significantly to the photocurrent, differences in the EQE spectra would be expected to reflect their individual absorption features. The absence of such differences strongly supports the conclusion that the photocurrent originates predominantly from the CABI layer, with negligible contribution from the HTMs.

The near-identical EQE traces of PPDT2FBT- and P3HT-based cells (Fig. S6) confirm that photocurrent generation is dominated by the CABI layer. However, it is worth noting that both PPDT2FBT and P3HT inherently exhibit a finite absorption extending beyond 600 nm, potentially causing a minor parasitic optical loss of photons near the band edge (650–700 nm), where CABI’s absorption coefficient decreases significantly. Keeping the polymer HTL thin (30 nm for PPDT2FBT) ensures that this parasitic absorption remains negligible, consistent with established practice in perovskite-based PVs43.

Deposition method comparison: Lab-scale vs. large-scale

As demonstrated above, CABI can be fabricated on a flexible substrate without compromising the efficiency of the cells. This opens up the possibility of using industrially applicable deposition methods such as slot-die coating and gravure printing. The following section examines the impact of these methods on the quality of the CABI layer and the efficiency of the cells. The CABI films deposited via the three mentioned methods have similar XRD patterns, as shown in Fig. 5a. The XRD patterns with glass/ITO/SnO2 and PET/ITO/SnO2 substrates are shown in Fig. S7. The absorption spectra of CABI films deposited via spin-coating, slot-die coating, and gravure printing on PET are shown in Fig. 5b. When comparing all the methods, it is evident that the deposition technique influences the sharpness and intensity of the absorption features. However, the extracted optical bandgaps remain largely consistent. For devices fabricated on PET/ITO/SnO₂ substrates, the calculated bandgap energies were 1.97 eV (spin coating), 1.93 eV (slot-die coating), and 1.97 eV (gravure printing), as shown in Fig. S1. The minimal variation (<0.05 eV) indicates that the fundamental optical properties of CABI are well preserved regardless of the deposition method.

The film thicknesses for spin coating, slot-die coating, and gravure printing were 250 ± 14, 270 ± 50, 280 ± 86 nm, respectively. All fabricated samples exhibit a typical absorption spectrum for CABI. However, there is a peak at 415 nm in all spectra, which is associated with AgI, BiI3, Cu2BiI5, or CuI-rich impurities9,31. The variations in absorbance can be attributed to differences in film morphology and thickness variation to each deposition technique. Spin-coating typically produces more uniform and dense films, leading to sharp absorption onset around 675 nm (Fig. 5b). Slot-die coating, while also producing continuous films, may result in variations in crystallinity, film thickness and uniformity affecting the absorption spectra (Fig. 5b). Gravure printing, although advantageous for large-scale and patterned film deposition, results in greater thickness variations and defects, displaying the highest intensity from 400 to 600 nm and a broader absorption onset around 750 nm (Fig. 5b). Despite differences, all methods produce films with similar absorption characteristics.

SEM was used to examine the surface morphology of the films prepared. The SEM image of the spin-coated CABI film (Fig. 6a) revealed the most uniform morphology among the samples with surface roughness of 60 ± 18 nm. However, the film exhibited a non-uniform structure. The SEM analysis of the slot-die coated film (Fig. 6b) displayed a slightly inferior morphology compared to the spin-coated samples. The film has more uneven surface, crystals which are not fully connected, and the surface coverage is lower and surface roughness is higher (185 ± 42 nm) compared to spin coated film. Despite these imperfections, the slot-die coated film still maintained a reasonable degree of uniformity and coverage, making this method a viable option for large-area deposition, albeit with somewhat reduced film quality compared to spin coating. In contrast, the SEM images of the gravure-printed CABI film (Fig. 6c) exhibited similar film quality as the slot die coated one but still the poorest morphology among the three methods. The gravure printed film was less homogeneous than the coating methods, including more pronounced smaller crystal and lower surface coverage leading to the highest roughness of 217 ± 44 nm (Table S1). Gravure printing, despite its high throughput capability, would require further ink formulation to improve the film uniformity and to reduce defects to be considered as a competitive deposition technique for high-quality CABI films. Ink formulation for higher viscosity can be achieved using additives like biopolymers such as starch36,38, which enhance the rheological properties without compromising film quality. Alternatively, solvent engineering by selecting solvents or solvent mixtures with tailored evaporation rates and viscosities—can also effectively increase the ink’s viscosity, optimizing it for specific deposition technique15,16,39,44.

Solar cell performance

After morphology examination, CABI-based devices (PET/ITO/SnO2/CABI/PPDT2FBT/Au) were fabricated and their performance was evaluated under 1 sun illumination conditions (AM 1.5 G, 100 mW/cm2). The device architecture and J-V scans are shown in Fig. 7a, b, respectively. The highest PCE was observed for the spin-coated CABI devices, with a champion PCE of 0.76%. The higher performance of these cells can be attributed to the better film quality produced by spin coating, which exhibits fewer defects and more uniform structure. This enhanced film quality contributes to more effective charge transport and reduced recombination, leading to improvements in JSC, VOC, and FF. Among other methods tested, slot-die coated devices demonstrated a moderate PCE of 0.47% in the best case, reflecting the slightly lower film quality compared to the devices employing spin-coated CABI layers. Gravure printed cells had a slightly lower PCE of 0.45% in the best case, which is very much comparable to the slot-die coated case. However, the SPOs of the champion devices (Fig. S3) show stabilized PCEs of 0.43% and 0.36% for slot-die coating and gravure printing, respectively. The relatively low device performance of the gravure printed device is primarily due to suboptimal CABI layer quality, including very low surface coverage. The device parameters are summarized in Table 3. Furthermore, the closely comparable EQE spectra of devices fabricated on flexible PET substrates using spin coating, slot-die coating, or gravure printing (Fig. S8) further confirm that the observed photocurrent—and consequently the device PCE—originates from the absorber material, that is, CABI.

a The device architectures and b forward (solid lines) and reverse (dashed lines) J-V curves with scan rate of 0.02 V/s of the CABI devices in which the CABI thin film was prepared on two different substrates using different methods; spin coated on glass substrate (black curve), spin coated on PET (red curve), slot-die coated on PET (blue curve), and gravure printed on PET (orange curve).

The deposition method significantly affects the morphology and film quality of CABI, and therefore, its solar cell performance. Spin coating yields the smoothest and highest-quality CABI films, resulting in the best device efficiency. In contrast, films produced via gravure printing and slot-die coating exhibit significantly higher surface roughness—approximately 4–6 times greater than that of spin-coated films (see Table S1). This trend is further supported by white light interferometry measurements, which show average roughness of 60 nm, 185 nm, and 217 nm for spin-coated, slot-die-coated, and gravure-printed films on PET/ITO/SnO2, respectively. The increased surface irregularity correlates with a decrease in PCE, from 0.76 (spin coating) to 0.45% (gravure printing). These findings highlight the critical role of deposition techniques in optimizing the efficiency of CABI-based solar cells and underline the importance of controlling film morphology to enhance device performance.

Summary and outlook

In this study, we explored the processing of the emerging PIM, CABI, with a special focus on its applicability in flexible and lead-free PVs. One of the most significant achievements of this work is the successful fabrication of CABI-based devices on a flexible substrate. To our knowledge, this study represents the first demonstration of such devices, marking a crucial step in the development of flexible PIM solar cells. Remarkably, our results demonstrated that the devices on both rigid and flexible substrates exhibited almost identical performance, indicating that the shift to flexible materials does not compromise the efficiency of this type of solar cells.

Additionally, we introduced a polymer HTM, PPDT2FBT, which has not been tested before in lead-free CABI solar cells. The performance of devices using PPDT2FBT as the HTM was found to moderately surpass that of devices employing the well-known HTM, P3HT. This finding suggests that PPDT2FBT is a suitable alternative to traditional materials and can help improve device efficiency, making it a promising candidate for future perovskite and PIM solar cell applications.

Moreover, we explored roll-to-roll compatible processing methods, which are crucial for the scalable production of flexible PV devices. However, our experiments highlighted that while these methods are applicable, controlling the morphology of the active layers remains a significant challenge, as seen in other studies.

In summary, this study has laid the groundwork for the development of flexible CABI-based solar cells, demonstrating both the feasibility and challenges associated with their production. The identical performance of devices on both rigid and flexible substrates, combined with the notable performance of the novel HTM, PPDT2FBT, underscores the potential of these materials in next-generation, low-toxicity PV technologies. While the current PCE of approximately 0.8% is modest, it should be viewed in the context of a relatively unoptimized material system. Even on rigid substrates using small-scale methods such as spin-coating, CABI and other Bi- and Sb-based PIMs are still in the early stages of performance development. Thus, the primary aim of this study was to demonstrate feasibility and establish a foundational platform integrating scalable processing, mechanical flexibility, and environmentally benign materials.

Overall, the results highlight opportunities for realizing flexible PIM solar cells for commercially viable applications. However, future efforts should focus on both film-level control and device-level engineering—including the use of other solution-processable electron transport layers, interlayers, and thin interfacial passivation layers—to refine interface quality, boost performance, and fully unlock the potential of perovskite-inspired PVs for both indoor and outdoor energy harvesting applications. In this context, recent advances such as the use of hypophosphorous acid additives to enhance CABI film quality on SnO2 and device efficiency further underscore the opportunities for performance enhancement through targeted material and interface engineering.

Future work, building upon this foundational proof-of-concept, will involve detailed optimization strategies to unlock the full potential of flexible perovskite-inspired PVs for both indoor and outdoor applications.

Methods

Chemicals: Bismuth iodide (BiI3), copper iodide (CuI), dimethylformamide anhydrous (DMF), dimethyl sulfoxide anhydrous (DMSO), hydroiodic acid 57% EMPLURA® (HI), chlorobenzene anhydrous, and 1,2-dichlorobenzene anhydrous were purchased from Sigma Aldrich. Silver iodide (AgI) and Tin (IV) oxide nanoparticle dispersion (15% in H2O) were acquired from Alfa Aesar. Poly(3-hexylthiophene) (P3HT) (4002-E) and poly[(2,5-bis(2-hexyldecyloxy) phenylene)-alt-(5,6-difluoro-4,7-di(thiophen-2-yl)benzo[c]-1,2,5thiadiazole)] (PPDT2FBT) were purchased from Rieke Metals and Brilliant Matters, respectively. All the chemicals were used as received without any further purification.

Cu2AgBiI6 thin film preparation

CABI ink was prepared by dissolving metal iodide precursors (0.2381 g of AgI, 0.5172 g of BiI3, and 0.2418 g of CuI) in 2 mL of DMSO-DMF (3:1 v/v) solvent mixture at 150 °C for 40 min. The hot precursor solution was then filtered with a 0.22 µm PTFE filter. Next day 15 µl of HI was added to 1 ml of solution and mixed for 1 h at room temperature. The solution was heated to 75 °C prior to deposition. Three deposition techniques (spin coating, slot-die coating, and gravure printing) were used to deposit CABI films on glass and flexible substrates in ambient environment. The as-deposited films were annealed in the air first at 50°C for 60 min and then at 130 °C for 5 min.

An O2 plasma treatment (Tepla 440-G) at 300 W for 5 min was performed on Glass/ITO/SnO2 and PET/ITO/SnO2 to improve the wettability of the CABI ink.

The CABI precursor solution was spin-coated onto glass/ITO/SnO2 and PET/ITO/SnO2 substrates with a speed of 3000 rpm for 60 s with 3000 rpm/s acceleration. The PET/ITO/SnO2 substrate was attached to a piece of glass with an adhesive surface to ensure it remained flat and to prevent bending during spin coating. A research laboratory slot die coater from infinityPV (Denmark) was used to deposit CABI on PET/ITO/SnO2 substrate. For coating, the slot head with a meniscus guide and width of 1 cm was used together with a pump flow rate of 0.01 ml/min and a coating speed of 7 mm/s. The gravure printing was done by using a table-top gravure-printing machine (Labratester, Norbert Schläfli Maschinen). 0.3 mL of the CABI solution was applied on the printing plate with an engraved pattern having a line density of 120 lines cm−1, then printed at a speed of 18 m/min.

It should be noted that while the optimization strategy for spin-coated CABI films was based on the methodology reported by Grandhi et al.9, the slot-die coating and gravure printing processes were independently optimized, as described in the Supplementary Note 1.

Solar cell fabrication

Indium tin oxide (ITO) coated glass slide was used as a rigid substrate. ITO was partially etched by immersing the substrate in the heated (65 °C) mixture of HNO3:HCl:H2O (1:15:10 volume ratio) solution for 60 s. The etched substrates were then cleaned by keeping the substrates 10 min in household detergent solution, 10 min in isopropanol, and 10 min in deionized water in ultrasonic bath. The substrates were rinsed with deionized water when changing the solution. Finally, the substrates were kept at 80 °C overnight. ITO covered polyethylene terephthalate (PET) (Eastman Flexvue OC50) was used as a flexible substrate, and the desired ITO pattern was realized by rotary screen printing of an etching paste (HiEP-300; P & P Solution Co., Ltd). SnO2 nanoparticles 15 wt% in water was diluted to 5 wt% in deionized water and spin coated on rigid and flexible substrates. CABI layers were prepared as explained in the Cu2AgBiI6 thin film deposition section. After annealing, the hole-transporting layer was spin-coated on the CABI layer. The P3HT solution was prepared by dissolving 20 mg of P3HT in 1 ml of anhydrous chlorobenzene. This solution was deposited by spin-coating 100 μl at 3000 rpm, 2000 rpm/s for 30 s. The PPDT2FBT ink was prepared by dissolving 10 mg of PPDT2FBT in 1 ml of anhydrous 1,2-dichlorobenzene. The solution was deposited by spin-coating 100 μl at 1200 rpm, 1000 rpm/s for 35 s. Finally, a 100 nm thick gold layer was thermally evaporated under a high vacuum (5 × 10−7 mbar) on top of the hole-transporting layer to form the back contact. The active area of cells was controlled to be 25 mm² by using a specific evaporation mask.

It should be noted that the active area of all solar cell devices was defined by the region covered by the thermally evaporated back-contact electrode, patterned using a shadow mask. For all device types—including those fabricated by spin coating, slot-die coating, and gravure printing—the active area was consistently maintained at 25 mm². Although the printed CABI films (in slot-die and gravure-printed devices) extended over larger areas (8 cm²), the masked electrode area determined the effective device area for PV measurements.

Characterization techniques

High-resolution XRD patterns of the CABI thin film samples on glass and PET substrates were collected using Cu Kα radiation with λ = 1.5406 Å on a Malvern Panalytical Empyrean Alpha 1 high-resolution X-Ray diffractometer (Malvern, UK). UV-Vis absorption spectra were recorded using an Agilent Technologies Cary 5000 UV-Vis-NIR spectrophotometer in the range of 400–800 nm. Baseline corrections were applied using a clean substrate of each type. The SEM images of the CABI films were recorded using a field emission scanning electron microscope Carl Zeiss Ultra 55 (operation was at 3 kV). The J–V characteristics of the solar cells were recorded under the AM1.5 solar simulator (SolarTest 1200, Atlas, USA), calibrated to 100 mW/cm2 (Si-reference cell filtered with a KG5 filter). The measurements were done with the Keithley 3706 A System Switch Multimeter in nitrogen atmosphere. The following measurement parameters were used: range of −0.2–0.6 V, voltage step 0.01 V, positive to negative and back, current compliance 20 mA, scan rate 0.02 V/s, and settling delay 200 ms. The surface roughness of the thin film samples were measured with Bruker ContourX-1000 white light interferometer.

Reporting summary

Further information on research design is available in the Nature Research Reporting Summary linked to this article.

Data availability

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

References

Bati, A. S. R. et al. Next-generation applications for integrated perovskite solar cells. Commun. Mater. 4, 2 (2023).

Yang, C. et al. Achievements, challenges, and future prospects for industrialization of perovskite solar cells. Light Sci. Appl. 13, 227 (2024).

Kumar, S. et al. A review on perovskite solar cells (PSCs), materials and applications. J. Materiomics 7, 940–956 (2021).

Peng, Y. et al. Lead-free perovskite-inspired absorbers for indoor photovoltaics. Adv. Energy Mater. 11, 2002761 (2021).

Huang, Y. T. et al. Perovskite-inspired materials for photovoltaics and beyond-from design to devices. Nanotechnology 32, 132004 (2021).

Chakraborty, A. et al. Rudorffites and beyond: perovskite-inspired silver/copper pnictohalides for next-generation environmentally friendly photovoltaics and optoelectronics. Adv. Funct. Mater. 32, 2203300 (2022).

Xu, J. et al. Air-stable lead-free antimony-based perovskite inspired solar cells and modules. ACS Energy Lett. 9, 671–678 (2024).

Sansom, H. C. et al. Highly absorbing lead-free semiconductor Cu2AgBiI6 for photovoltaic applications from the quaternary CuI−AgI−BiI3 phase. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 143, 3983–3992 (2021).

Grandhi, G. K. et al. Enhancing the microstructure of perovskite-inspired Cu-Ag-Bi-I absorber for efficient indoor photovoltaics. Small 18, 2203768 (2022).

Mahmoudi, T. et al. Suppression of Sn2+/Sn4+ oxidation in tin-based perovskite solar cells with graphene-tin quantum dots composites in active layer. Nano Energy 90, 106495 (2021).

Fujihara, T. et al. Fabrication of high coverage MASnI3 perovskite films for stable, planar heterojunction solar cells. J. Mater. Chem. C 5, 1121–1127 (2017).

Saha, P. et al. Performance optimization of MASnI3 perovskite solar cells: insights into device architecture. Micro Nanostruct. 191, 207827 (2024).

Grandhi, G. K. et al. Perovskite-inspired Cu2AgBiI6 for mesoscopic indoor photovoltaics under realistic low-light intensity conditions. Sustain. Energy Fuels 7, 66–73 (2023).

Vidal, R. et al. Assessing the environmental impact of pnictogen-based perovskite-inspired materials for indoor photovoltaics. Adv. Energy Mater. 2403981 https://doi.org/10.1002/aenm.202403981 (2024).

Pai, N. et al. Solution processable direct bandgap copper-silver- bismuth iodide photovoltaics: compositional control of dimensionality and optoelectronic properties. Adv. Energy Mater. 12, 2201482 (2022).

Al-Anesi, B. et al. Antimony-bismuth alloying: the key to a major boost in the efficiency of lead-free perovskite-inspired photovoltaics. Small 19, 2303575 (2023).

Wang, M. et al. Lead-free perovskite materials for solar cells. Nano-Micro Lett. 13, 62 (2021).

Parvazian, E. et al. Selecting non-halogenated low-toxic hole transporting materials for Roll-to-Roll perovskite solar cells using carbon electrodes. Commun. Mater. 5, 82 (2024).

Xu, D. et al. Constructing molecular bridge for high-efficiency and stable perovskite solar cells based on P3HT. Nat. Commun. 13, 7020 (2022).

Wang, Y. et al. PTAA as efficient hole transport materials in perovskite solar cells: a review. Sol. RRL 6, 2200234 (2022).

Hu, L. et al. High efficiency perovskite solar cells with PTAA hole transport layer enabled by PMMA:F4-TCNQ buried interface layer. J. Mater. Chem. C 10, 9714–9722 (2022).

Hu, X. et al. Molecular weight effect of poly-TPD hole-transporting layer on the performance of inverted perovskite solar cells. Sol. Energy 218, 368–374 (2021).

Ganesan, P., Nazeeruddin, M. K. & Ganesan, P. Perovskite solar cells: challenges facing polymeric hole selective materials in p–i–n configuration. Adv. Energy Mater. 12, 2409939 (2024).

Al-Anesi, B. et al. Dissecting the role of the hole-transport layer in Cu2AgBiI6 solar cells: an integrated experimental and theoretical study. J. Phys. Chem. C. 128, 9446–9453 (2024).

Lee, T. H. et al. Investigation of charge carrier behavior in high performance ternary blend polymer solar cells. Adv. Energy Mater. 6, 1600637 (2016).

Nguyen, L. et al. Semi-crystalline photovoltaic polymers with efficiency exceeding 9% in a ∼300 nm thick conventional single-cell device. Energy Environ. Sci. 7, 3040–3051 (2014).

Koh, C. W. et al. Enhanced efficiency and long-term stability of perovskite solar cells by synergistic effect of nonhygroscopic doping in conjugated polymer-based hole-transporting layer. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 9, 43846–43854 (2017).

Sepalage, G. A. et al. Can laminated carbon challenge gold? Toward universal, scalable, and low-cost carbon electrodes for perovskite solar cells. Adv. Mater. Technol. 7, 2101148 (2021).

Predeep, P. et al. Measurement of hole mobility in P3HT based photovoltaic cell using space charge limited current method. AIP Conf. Proc. 2162, 020142 (2019).

Zhang, F. et al. Low-temperature solution-processed Cu2AgBiI6 films for high performance photovoltaics and photodetectors. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 14, 18498–18505 (2022).

Putland, B. W. J. et al. Compositional transformation and impurity-mediated optical transitions in co-evaporated Cu2AgBiI6 thin films for photovoltaic applications. Adv. Energy Mater. 14, 2303313 (2024).

De Rossi, F. et al. Modified P3HT materials as hole transport layers for flexible perovskite solar cells. J. Power Sources 494, 229735 (2021).

Gao, Y. et al. Flexible perovskite solar cells: from materials and device architectures to applications. ACS Energy Lett. 7, 1412–1445 (2022).

Green, M. A. Commercial progress and challenges for photovoltaics. Nat. Energy 1, 15015 (2016).

Kim, Y. Y. et al. Roll-to-roll gravure-printed flexible perovskite solar cells using eco-friendly antisolvent bathing with wide processing window. Nat. Commun. 11, 5146 (2020).

Bisconti, F. et al. Polymer-assisted single-step slot-die coating of flexible perovskite solar cells at mild temperature from dimethyl sulfoxide. ChemPlusChem 86, 1442–1450 (2021).

Saki, Z. et al. Solution-processed perovskite thin-films: the journey from lab- to large-scale solar cells. Energy Environ. Sci. 14, 5690–5722 (2021).

Phillips, R. et al. Influence of temperature and point defects on the X-ray diffraction pattern of graphite. Carbon Trends 5, 100124 (2021).

Grandhi, G. K. Wide-bandgap perovskite-inspired materials: defect-driven challenges for high-performance optoelectronics. Adv. Funct. Mater. 34, 2307441 (2024).

Buizza, L. R. V. et al. Charge-carrier mobility and localization in semiconducting Cu2AgBiI6 for photovoltaic applications. ACS Energy Lett. 6, 1729–1739 (2021).

Grandhi, G. K. et al. Role of self-trapped excitons in the broadband emission of lead-free perovskite-inspired Cu2AgBiI6. J. Phys. Chem. Lett. 14, 4192–4199 (2023).

Zhanh, Q. et al. Hypophosphorous acid additive engineering for efficient Cu2AgBiI6 solar cells. Advanced Science News, no. 2504863, https://doi.org/10.1002/adfm.202504863 (2025).

Bisconti, F. et al. One-step polymer assisted roll-to-roll gravure-printed perovskite solar cells without using anti-solvent bathing. Cell Rep. Phys. Sci. 2, 100639 (2021).

Mohammed, M. K. A. et al. Boosting the performance of CH3NH3PbI3 perovskite solar cells with a well-aligned polymeric hole-transporting layer. Indian. J. Phys. 99, 3009–3018 (2024).

Acknowledgements

The work is part of the Research Council of Finland Flagship Programme, Photonics Research and Innovation (PREIN), decision number 346545. This work was supported by the Research Council of Finland, Printed intelligence infrastructure funding, decision 358621. This work made use of the Tampere Microscopy Center facilities at Tampere University. N.L. thanks The Emil Aaltonen Foundation for funding. P.V. and G.K.G. acknowledge the Jane and Aatos Erkko Foundation (SOL-TECH project) for funding. P.V. and G.K.G. also thank the SPOT-IT project founded by the CETPartnership, the Clean and Energy Transition Partnership under the 2022 CET Partnership joint call for research proposal, co-founded by the European Commission (GA 101069750) and with the founding of the organizations detailed on https://cetpartnership.eu/funding-agencies-and-call-modules.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

V.H. conducted the experiments and wrote the first draft of the manuscript. T.K., R.S., and P.V. supervised the project and revised the manuscript. G.K.G. helped with XRD and UV-Vis data and revised the manuscript. N.L. conducted the SEM and XRD measurements. All the authors contributed to comments on and revision of the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Holappa, V., Grandhi, G.K., Lamminen, N. et al. Flexible Cu2AgBiI6-based perovskite-inspired solar cells using large-scale processing methods. npj Flex Electron 10, 6 (2026). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41528-025-00505-5

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41528-025-00505-5