Abstract

In recent years, smart contact lenses as a type of wearable device have attracted significant attention in health monitoring and disease detection. In this study, we combine a resistive sensor based on a cracked PEDOT: PSS structure with a 70 MHz double-loop gold antenna, enabling high-precision and continuous measurement of intraocular pressure (IOP). By comprehensively optimizing the sensor design, device structure, and wireless detection system, we achieved a sensitivity of 47.31 Ω/mmHg—approximately 15 times higher than conventional approach, corresponding to a resistance change 183 times larger. Both in vitro wireless IOP measurements of a porcine eye and in vivo wireless IOP measurements of rabbit eyes altered by microbead injection, using a commercial tonometer and a fabricated sensor lens, showed a strong correlation with R² values of 93% and 97%, respectively. These findings highlight the platform’s potential for long-term, non-invasive IOP monitoring, thus making a significant contribution to early diagnosis and treatment of glaucoma.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Glaucoma is a prevalent and incurable eye disease that can lead to irreversible nerve damage and blindness if left untreated1,2,3. The only currently available preventive measure is to reduce the risk of disease progression through regular intraocular pressure (IOP) monitoring, combined with IOP management such as medication and surgery4. However, only single-time measurements of IOP are currently available clinically (e.g., Goldman tonometry), which can affect the timeliness of monitoring and lead to missed optimal treatment windows. Consequently, continuous 24-h IOP monitoring is essential for effective early-stage glaucoma prevention5.

A promising approach to address this need is to develop contact lenses with sensors that measure IOP by capturing internal ocular changes6,7,8,9. The principle behind this technology is to sense deformation in the contact lens caused by elevated IOP, which changes the curvature radius of the cornea10. Current sensor technologies include microfluidic, optical, and wireless systems. The first two rely on the changes in fluid flow in microfluidic channels integrated into the contact lens and the principle of light reflection11,12,13,14,15,16, respectively, mainly observed by the naked eye or camera. These approaches have low sensitivity and large errors. Additionally, such approaches face limitations in dark environments. In contrast, wireless systems have the potential for practical monitoring via continuous information transmission to a receiving antenna or device17. Wireless monitoring systems can be categorized into inductive18,19,20,21,22, capacitive23,24,25,26,27,28, and resistive29,30,31,32,33 sensors based on their operational principles. In some designs, both inductance and capacitance vary in response to external stimuli, allowing for hybrid sensing capabilities34,35. Among these, a rigid-flexible hybrid structure has been designed to utilize the change in resistive strain of the flexible component to monitor signal variations using conventional coupled coils29. However, traditional wireless systems exhibit minimal S11 parameter variation. Additionally, there has been a report of using a Wheatstone bridge consisting of two strain gauges and two compensating resistors intended to enhance the sensitivity of IOP measurement and reduce errors caused by temperature changes30,31. However, integrating complex Bluetooth devices in contact lenses can hinder patient comfort. Moreover, another approach utilizes transparent silver nanowires to connect the lens to a 13.56 MHz ASIC chip for signal transmission, but this setup increases manufacturing costs and may cause discomfort32,33.

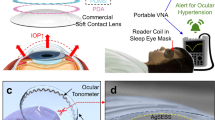

In response to these limitations, we propose a contact lens design based on a transparent resistive pressure sensor. The contact lens consists of a metal antenna and a ring-shaped multilayer pressure sensor consisting mainly of a Poly(3,4-ethylenedioxythiophene): Poly(styrenesulfonate) (PEDOT: PSS) film, which has good light transmittance, minimizing interference with the user’s vision36. We designed a multilayer sandwich structure as the resistive sensor, including a highly sensitive PEDOT: PSS layer and a PEDOT: PSS/Polyvinyl alcohol (PVA) layer to improve stretchability. When the IOP increases and causes the sensor to stretch, the highly sensitive PEDOT: PSS layer cracks, causing a change in resistance (Fig. 1a). We successfully achieved dynamic monitoring of 1.5 Ω/mmHg in the range of 6 mmHg to 36 mmHg. Meanwhile, we introduced the idea of Parity-Time (P-T) symmetry37 into the antenna at the detector side to improve the Q-factor of the magnetic resonance coupling system, which improves the energy transfer efficiency of the coupled oscillators and realizes high-sensitivity wireless measurement (Fig. 1b). We have designed a gain resonator to compensate for dissipation losses during wireless transmission, significantly increasing the IOP measurement accuracy. This increase in Q-factor cannot be realized in conventional dissipative systems and can only be observed in the P-T symmetry system.

a The schematic diagram of a wireless contact lens system for non-invasive and continuous intraocular pressure (IOP) monitoring. At the lens end, it consists of an LCR circuit and a resistive sensor composed of PEDOT: PSS and PEDOT: PSS/PVA, which converts resistance changes into signal variations. The conventional loss LCR receiving circuit at the reader end was replaced with an equivalent negative resistance (-R) P-T symmetric system. b Utilizing this P-T effect significantly enhances detection sensitivity.

Results

Multilayer PEDOT based resistance sensor

A pressure-sensitive intraocular lens with a multilayer structure based on PEDOT: PSS and PEDOT: PSS/PVA sensor has been developed. The multilayer structure sensor is composed of a PDMS substrate, a layer of highly conductive PEDOT: PSS activated with sulfuric acid and a layer of PEDOT: PSS/ PVA to detect the IOP with high sensitivity, biocompatibility, and repeatability (Fig. 2a). The first layer of the sensor consists of a PDMS film, serving as the substrate that not only enhances the overall stretchability of the sensor but also facilitates a better integration with the underlying PDMS contact lens. The thickness of the film was found to be approximately 56 μm (Fig. S1). This integration enables the accurate conveyance of the contact lens deformation to the sensor, thereby improving the sensitivity observed in response to the deformation. The second layer comprises a highly conductive PEDOT: PSS film, which has been treated with sulfuric acid. PEDOT: PSS acid treatment significantly improves its electrical and mechanical properties38. Upon acid treatment, PEDOT films undergo a transformation in which the PEDOT flakes arrange into a fibrillar structure, while a substantial portion of the PSS chains are removed. This treatment enhances the crystallinity of the PEDOT, thereby significantly improving its conductivity39. Consequently, acid-treated PEDOT:PSS exhibits lower resistance and higher conductivity, thus presenting greater potential for applications requiring high conductivity40. The third layer consists of a PEDOT: PSS/PVA film, which combines PEDOT: PSS with PVA binder to enhance the film’s stretchability. This layer exhibits good conductivity and stretchability, supporting current flow and providing the sensor with recoverability. Due to the relatively low stretchability of the second layer, the highly conductive PEDOT: PSS film, cracks occur when stretched (Fig. 2b). This results in the current flowing through the third layer, composed of PEDOT: PSS/PVA film along the cracked paths. The second layer exhibits lower resistance and higher conductivity, while the third layer, with its enhanced stretchability, has relatively higher resistance. Therefore, more cracks form in the second layer upon stretching, leading to a decrease in the conductivity of the sensor and an increase in resistance. Moreover, both the PEDOT: PSS/PVA film and the PDMS film, which serve as the substrate, exhibit good recoverability after deformation. The sensor can return to its original state after stretching, ensuring the reversibility of the resistance changes during the IOP measurement and enabling long-term IOP monitoring. A tensile test was conducted to determine the optimal ratio of PVA in the third layer of the multilayered sensor. The experiment involved applying tension to the ends of PEDOT: PSS/PVA films with different PVA ratios to induce deformation while recording the resistance changes using a multimeter through direct wiring. The resistance change after deformation gradually decreases with an increase in the ratio of PVA (0 wt%, 2 wt%, 5 wt%, and 10 wt%) (Fig. 2c). At 2 wt% PVA content, the slope of the change in resistance is larger and more stable, approaching linearity with a slope value of approximately 2.66841. Additionally, cycling stretching/releasing tests up to 15% strain showed that lower PVA content resulted in higher sensitivity but more pronounced hysteresis (Figs. S2 and S3).

a The top view structural configuration of contact lenses b Illustration and microscope image of cracks formed in the sensor after stretching. c The variation in resistance with different PEDOT: PSS/PVA ratios during a stretching experiment. d The visible spectrum transmission comparison with various PEDOT: PSS/PVA ratios.

Meanwhile, a critical parameter in smart contact lenses is light transmission. Each components are generally expected to have above 80% transmission in the visible region of the electromagnetic spectrum41. To ensure that the sensors do not impede the visible range when placed on contact lenses, the transmittance of PEDOT: PSS/PVA thin film sensors with different ratios was tested within the visible light spectrum (Fig. 2d). The transmittance test revealed that the 2 wt% sensors exhibited the highest transparency after the PEDOT: PSS sample at the visible range, with a minimum transmittance of nearly 82. 8%. This is due to the fact that an increased PVA content results in a higher viscosity of the polymer suspension, which leads to the formation of a thicker film during spin-coating at a fixed rotational speed42. The 2% PVA formulation was finally selected due to the low strain for contact lens applications and the need for high sensitivity and transparency.

Assessment of PEDOT sensor for Intraocular pressure measurement

A balloon experiment was conducted to determine the sensitivity of the PEDOT: PSS/PVA sensor. The balloon, made of PDMS, was connected to an automatic syringe via an inlet, allowing the injection or extraction of air into the hollow cavity, mimicking ocular deformation. The inlet of the balloon was connected to a pressure meter to monitor the pressure and obtain intraocular pressure readings. The pressure in the model eye was equal to that of the syringe pump system. In the balloon experiment, the sensor-equipped contact lens was placed directly on top of the balloon, and the sensor ends were connected to a source meter via wires. The resistance variation of the sensor corresponding to the balloon’s expansion was obtained.

To determine the recoverability of the sensor, a cyclic experiment was conducted. The sensor was placed on a PDMS balloon, pressure was increased from 6 mmHg to 36 mmHg, and then returned to 6 mmHg, defining one cycle. Each cycle was performed in about 75 s on average, with more than 100 cycles conducted. The resistance variation of the sensor after multiple stretches was obtained (Fig. 3a). The red curve illustrates the approximate response trend of the sensor. After multiple cycles of deformation and recovery, the resistance variation of the sensor stabilizes within a relatively consistent range. This phenomenon can be attributed to the initial stretching process, during which relatively few cracks form in the highly conductive PEDOT film. However, after undergoing multiple stretches within the IOP measurement limits, the crack formation reaches saturation, leading to a more stable sensor performance. Meanwhile, the asymmetry observed in resistance mainly results from the viscoelastic properties of the PEDOT: PSS/PVA composite material and minute fluctuations in pressure during the stretching and releasing process. Moreover, our measurement involves pressure-induced loading and unloading due to IOP changes, which differ from conventional uniaxial tensile tests. Nevertheless, the stepwise impedance response remains stable under varying IOP, and in an acceptable range (Fig. 3e, f).

(The red line represents the fitting line of the resistance changed trend). a The resistance changes of the PEDOT sensor during repeated stretching on a PDMS eye mold by varying intraocular pressures (IOP). b The relationship between IOP and relative change in resistance after the resistance variation stabilizes. c The real part of the impedance Re (Zin) of the PEDOT sensor attached to the antenna at different IOP levels. d Response of the real part of the impedance Re (Zin) of the PEDOT sensor under IOP increasing/decreasing cycles. e Hysteresis curves of the real part of the impedance Re (Zin) of the PEDOT sensor for IOP increasing/decreasing cycles. f The real part of the impedance Re (Zin) of the PEDOT sensor of the wireless sensor as a function of step index when the IOP was increased/decreased stepwisely.

Therefore, prior to the formal measurements, a pre-stretching process was conducted using the PDMS eyeball model by increasing the internal pressure to 36 mmHg and repeating this step 20 times. This procedure helped to improve mechanical stability and reduce signal drift. It can be observed that the resistance change has a linear relationship with IOP. At 36 mmHg, there is a maximum change of approximately 10%.

The porcine eye experiments further demonstrated the sensor’s applicability in animal ocular environments (Fig. 3b). Due to differences in the type of friction between the fabricated device and the surface of the eye under measurement, one being a balloon made of PDMS and the other porcine eye, resulting in kinetic and lubricated friction, respectively, the resistance changes in porcine eyes are smaller compared to those with PDMS molds over the eye pressure range of 6–36 mmHg. In addition to frictional effects, differences in the radius of curvature change under pressure between the PDMS balloon and porcine eyes may also contribute to this variation. Despite these factors, the response remains linear with a sensitivity of 1 ohm/mmHg. (Figs. S4 and S5). This finding validates the feasibility of conducting animal experiments to evaluate the sensor’s performance. Therefore, a sensor made of PEDOT: PSS and 2 wt% PEDOT: PSS/PVA was selected as the resistive sensor for contact lenses.

A patterned PEDOT sensor film was combined with gold antennas with resonance frequency tuned at 70 MHz. A smart contact lens using a 3D-printed mold was fabricated to measure intraocular pressure. The contact lenses with sensors were connected directly to a vector network analyzer (VNA) via a cable to detect changes in the antenna impedance. The effect of intraocular pressure on the deformation of the contact lens was simulated utilizing the fabricated PDMS balloon. When IOP increases, the cracks formed on the PEDOT sensor cause changes in the overall impedance of the contact lens antenna. The trend of the real part of the impedance (Z′) as a function of intraocular pressure variation is shown in Fig. 3c, where the sensor Z′ increases as the IOP rises from 6 mmHg to 36 mmHg. Figure 3d shows the response characteristics of the stabilized PEDOT sensor to cyclic changes in intraocular pressure from 6 to 36 mmHg with a 5% change in the real part of the impedance. It demonstrates a regular and highly reproducible cyclic pattern. The hysteresis behavior of the sensor is shown in Fig. 3e, where there are differences in the impedance paths corresponding to the rising process of the IOP (green line) and the falling process (red line). This hysteresis behavior is a typical response of pressure sensors and is quantified by a gauge factor (GF) of about 0.0015/mmHg, an important parameter to consider during sensor calibration. Figure 3f shows the response curve of the real part Re (Zin) of the impedance of the PEDOT sensor to a stepwise IOP change. The stepwise pressure change pattern allows evaluation of the sensor’s performance at each individual pressure point at steady state. The results show that the sensor has excellent response and repeatability and provides strong support for practical intraocular pressure monitoring applications.

The hysteresis behavior of the sensor is shown in Fig. 3e, where there are differences in the impedance paths corresponding to the rising process of the IOP (red dashed line) and the falling process (green solid line). This hysteresis behavior is a typical response of pressure sensors and is quantified by a hysteresis factor (GF) of about 0.0015/mmHg. Figure 3f shows the response curve of the real part Re (Zin) of the impedance of the PEDOT sensor to a stepwise IOP change. The stepwise pressure change pattern allows evaluation of the sensor’s performance at each individual pressure point at steady state. The results show that the sensor has excellent response consistency, reliability, and repeatability, and provides strong support for practical intraocular pressure monitoring applications.

When intraocular pressure increases, an increase in the real part of the impedance (Z′) is observed without causing a frequency shift. This allows measurements to be conducted at a single resonant frequency. In contrast, traditional LCR sensors that rely on changes in inductance or capacitance to detect intraocular pressure require consideration of the shifts15,16,17,18,21,22,23,24,25. Therefore, our IOP measurement system offers several distinct advantages. First, the measurement time is reduced because frequency scanning is unnecessary. Second, high-Q antennas can be employed, as there is no requirement of wide antenna to broaden the resonance range. Finally, this approach simplifies the detector circuit, making it more efficient and light weight to implement. Although PDMS has different mechanical properties compared to ocular tissue, this model provides a consistent and replicable environment for evaluating how the sensor responds to changes in pressure.

Wireless readout: traditional loss antenna vs. P-T symmetric antenna

The P-T symmetry wireless system is inspired by quantum mechanical systems that balance the gain and loss of a coupled system with applications in optics, acoustics, and electronics43. In electronics, the conventional energy loss detection antenna is replaced by a signal amplifying P-T symmetric antenna to improve wireless sensing in contact lenses44,45,46. Compared with the traditional passive LCR antenna system, the P-T symmetric antenna introduces a negative resistive unit and adopts an active system design, which transforms into an LC(-R) system, compensating for the loss in energy transmission and enhancing the signal strength, thus realizing the signal amplification effect. This design gives the P-T symmetric antenna a significant advantage in wireless sensing applications, enabling the detection of weaker signals. The system sensitivity can be improved by finding the exceptional point (EP) (near which the eigenvalues and eigenvectors of the coupled oscillators coalesce) can significantly increase the sensitivity of our P-T symmetry system (Fig. S6)31. Unlike manually soldering the P-T antenna before, we designed compact PCB boards that are easy to assemble onto the eyeglass frames. To verify the sensitivity of the P-T symmetric antenna, we measured the initial impedance of the conventional antenna versus the P-T symmetric antenna in the IOP sensing contact lens (Fig. 4a).

a The configuration of P-T symmetric PCB board. b The real and imaginary parts of the impedance from a conventional readout antenna coupled to a contact lens sensor (above) versus a P-T readout resonator coupled to a contact lens sensor (below). c The real part of the impedance in conventional antenna as IOP varies, measured by sensor-integrated contact lenses. d The real part of the impedance in the P-T antenna as IOP varies, measured by sensor-integrated contact lenses. e The graph illustrates the relationship between the absolute value of the relative change in the real part of the impedance, |ΔRe(Zin)/Re(Z0) |, and the change in IOP. f linear relationship (R² = 93%) between IOP and contact lens resistance Re (Zin) using a tonometer and PT lens sensor.

At 70 MHz, conventional antennas exhibit dual resistance peaks due to mode splitting caused by proximity coupling, resulting in a wide 3.528 MHz bandwidth, as depicted in Fig. 4b (top) and c, which is unfavorable for detection. In contrast, P-T symmetric antennas show an initial resistance close to −6 KΩ, with a narrower bandwidth of 0.2064 MHz and a sharper peak than conventional antennas, as shown in Fig. 4b (bottom) and d. The Q factor (quality factor) is an essential indicator for the performance of oscillator and resonator systems. The higher the Q value, the better the performance of the oscillator47.

According to the equation:

where:

-

\({f}_{0}\) is the resonant frequency (in hertz).

-

\(\varDelta f\) is the bandwidth or full-width at half maximum of the peak (in hertz).

The Q-factor can reach 339.15 in the P-T system, while the Q-factor of the conventional antenna determined via the Gaussian fitting function is 15.71 (Fig. 4b top). Therefore, the introduction of the P-T symmetry in the wireless measurement system provides an exponential increase in sensitivity.

Figure 4c shows the change in the resistance of the conventional detector antenna as the IOP of the PDMS balloon was varied. The conventional antenna detected a very small change in resistance. At a frequency of 70 MHz, the output resistance difference is only 5.94 Ω at an IOP ranging from 6 mmHg to 36 mmHg. Figure 4d shows the change of resistance in the P-T symmetric antenna. According to the previous experiments and reports, to get better linear readings, we used the broken P-T condition37,48,49 to perform the measurement. When the IOP increases from 6 mmHg to 36 mmHg, the Z′ changes from −4.5 KΩ to −5.59 KΩ, which is 183 times larger than the change of the Z′ in the conventional antenna. Multiple measurements also show that the Z′ response to IOP change has a good linear relationship in the case of broken P-T. Comparing the relative absolute value of the conventional antenna’s Z′ variation with that of the P-T symmetry, the Z′ change detected by the P-T system is dramatically enhanced. Specifically, the conventional antenna has a sensitivity of 1.98% for pressures ranging from 6 mmHg to 36 mmHg, while the P-T antenna system has a sensitivity of approximately 30.46%, which is about 15 times greater (Fig. 4e). To determine the correlation between IOP and contact lens resistance data, we used a commercially available tonometer to determine the IOP values at each step (Fig. 4f). We conducted four porcine eye experiments and injected the same volume of water (0.08 ml) each time using a syringe pump to control IOP in the eyes. The resistance values were measured using the P-T antenna, and the IOP values were recorded using a tonometer. Ultimately, we obtained a coefficient of determination (R²) of 93%, demonstrating a strong linear correlation between the sensor lens resistance and the tonometer-measured IOP. This result provides a solid basis for calibrating the contact lens device. Therefore, we have established a complete IOP detection system using the P-T symmetric antenna to improve the detection sensitivity.

Real-time intraocular pressure measurement and biosafety in animals using smart IOP contact lenses

To better fit the rabbits’ eyes, we specially designed an IOP contact lens with a diameter of 14 mm and a curvature radius of 16 mm. A 2 mm circular hole was punched in the center of the lens using a biopsy punch. The experimental setup is shown in Fig. 5a. First, the initial IOP of each anesthetized rabbit was measured using a tonometer. Next, artificial tears were applied, and the smart contact lenses were placed on the rabbits’ eyes. An animal headcover embedded with a P-T PCB antenna was used, and the board was connected to a DC power supply. The Z′ values were recorded by a vector network analyzer at 5-s intervals. Sodium hyaluronate was then injected into the eye (Fig. 5b), occupying space and inhibiting aqueous humor outflow, which led to an increase in IOP. After the experiment, the IOP gradually returned to normal within 2 days. Two anesthetized rabbits were used for in vivo measurements (Fig. 5c, d). The experimental procedure involved measuring the rabbits’ IOP before sodium hyaluronate injection, immediately after the injection, and again 2 days later. Each measurement session lasted 10 min, during which the IOP of each eye was measured separately using the iCare tonometer, both before and after the smart contact lenses were worn. The results showed that both rabbits exhibited similar IOP fluctuations. MATLAB was used to analyze the iCare tonometer data, obtained before and after contact lens application, along with the contact lens resistance data. The rabbits’ IOP ranged from 20 to 25 mmHg prior to the injection of sodium hyaluronate, increased significantly following injection, and returned to normal levels after 2 days. We observed a strong linear correlation (R² = 0.97462) between the IOP data from the tonometer and the contact lens resistance values (Fig. 5e), which is consistent with the IOP-resistance relationship observed in our porcine eye experiments.

a schematic of the experimental setup for intraocular pressure testing in rabbits. b Concept diagram illustrating the effect of injecting sodium hyaluronate (Healon®) into the eyeball. c, d In-vivo IOP measurements before and after injecting sodium hyaluronate into two rabbits’ eyes, and 2 days later. (Each data point represents the average of n = 30 independent measurements, with error bars indicating the standard deviation). A linear correlation between the rabbits’ IOP and the resistance value Re (Zin) (R2 = 0.97462). e A linear correlation was observed between the rabbits’ intraocular pressure and the resistance value Re (Zin) (R2 = 0.97462). f Thermal imaging temperature detection of rabbits using a FLIR camera. g Cell viability at 24, 48, and 72 h after incubating contact lens material with corneal cells. h Fluorescence microscopy images of human corneal epithelial (HCE) cells after live and dead cell staining (scale bar = 220 μm).

To demonstrate the safety of the IOP measurement system, we monitored the temperature around the rabbit’s eye using a thermal imaging camera during in vivo wireless measurements (Fig. 5f). We observed no difference between rabbits wearing contact lenses and those not wearing them. The temperature remained below 35.2 °C throughout and following wireless measurements via the P-T symmetric antenna, indicating no hazardous temperature variation on the eye wearing the contact lens devices.

Next, the biosafety of the soft contact lens was verified in two ways. First, the survival rate of human corneal epithelial cells (HCEs) was assessed by culturing them with the contact lens samples (Fig. 5g). After 24 and 48 h, the average cell viability exceeded 90%. Second, we evaluated cell viability under a microscope (Fig. 5h) by incubating HCE cells and the PEDOT: PSS component of the sensor for 24, 48, and 72 h. The cells were stained using calcein-AM (green fluorescence for live cells) and propidium iodide (PI, red fluorescence for dead cells)50. Imaging with a confocal laser scanning microscope revealed only a small number of PI-stained cells at each time point, indicating that the PEDOT: PSS-based sensors had a negligible impact on cell viability. At the same time, fluorescence microscopy images (20×) of the corneal epithelium were taken after 72 h of culture to better observe the integrity of the cells (Fig. S7). For the good stability of the sensor lens in real case environments, a multiday storage test and ultrasonic cleaning experiment were conducted on the contact lens (Fig. S8). The results showed that daily care solution immersion has less effect on the sensors and exhibits good stability, but multiple ultrasonic cleanings will lead to a rise in electrical resistance, which is caused by structural damage. Therefore, durability and long-term stability still need to be improved.

Discussion

We have demonstrated the PEDOT:PSS/PVA resistive sensor, fabricated via the described process, which possesses three key attributes: high sensitivity, recoverability, and high transmittance. The high sensitivity ensures that IOP changes are effectively transmitted through the P-T wireless transmission system. Recoverability enables the sensor to regain its original state following deformation, facilitating continuous and reliable IOP measurements. Moreover, its high transmittance ensures that normal vision remains largely unaffected during the measurement process. By integrating these three characteristics, the sensor enables continuous monitoring of IOP fluctuations with minimal disruption to the patient’s daily life, thereby providing a comprehensive record of IOP variations.

While resistance changes in a conventional wireless transmission system may not strongly influence the Z′ at the detector circuit, incorporating a P-T symmetric detector significantly enhances sensitivity to IOP changes. This exceptional sensitivity holds promise for the practical applications, as evidenced by in vivo rabbit experiments indicating that the method could be highly beneficial for continuous, real-time IOP monitoring.

While this study directly alters IOP in rabbits, body posture changes can also induce fluctuations in IOP32,35. Meanwhile, blinking has been shown to cause significant IOP fluctuations, which can affect the stability of continuous monitoring51. Therefore, accurately identifying and eliminating transient interference signals caused by body posture variation and blinking is crucial to ensuring the accuracy and reliability of IOP monitoring.

Additionally, the contact lens sensor has demonstrated biocompatibility, confirming its safety for use in biological systems. Consequently, this sensor offers substantial potential for various applications, particularly for monitoring and treating ocular diseases such as glaucoma, where accurate IOP assessment is essential. Its capabilities make it an excellent candidate for inclusion in the diagnosis and management of these eye conditions.

Methods

Preparation of the multilayer resistive sensor film

The glass substrate (2.5 × 7.6 cm2) was pre-washed with detergent, deionized water, acetone, and isopropyl alcohol (IPA). A 10 wt% aqueous polyvinyl alcohol (PVA, NW ~ 22000, MP) solution was spin-coated onto the glass substrate at 500 rpm for 30 s and then dried at 80 °C for 20 min. Polydimethylsiloxane (PDMS, DuPont Toray Specialty Materials K.K.) (20:1) prepolymer was spin-coated onto glass slides to form a film. The spin speed was set at 2000 rpm for 30 s and then cured at 80 °C for 2 h. The PDMS films on glass plates were subjected to oxygen plasma treatment for 5 min to improve the hydrophilicity of contact lenses. First, a conventional Poly(3,4-ethylenedioxythiophene): Poly(styrenesulfonate) (PEDOT: PSS) aqueous solution (Clevios PH 1000, Heraeus) was filtered through a 0.45 μm syringe filter, and then spin-coated onto a glass substrate (2.5 × 7.6 cm2) to form the initial film. This was followed by thermal annealing on a hotplate at 120 °C for 15 min. H2SO4 treatment was performed by dropping 100 μL of 1 M H2SO4 (FUJIFILM) solution onto the PEDOT: PSS film on a hotplate at 160 °C. The film was dried after approximately 5 min. It was then cooled to room temperature and rinsed three times with deionized water. Then, the polymer film was dried again at 160 °C for approximately 5 min. The sensor film is then patterned with a circular cutter (DSPIAE) (inner diameter: 10 mm; outer diameter: 12 mm). Then, the glass substrate is immersed in water, so the highly conductive film is peeled off the substrate (Fig. S9). The thickness of the film was measured by a surface measurement instrument (BRUKER, DXT-E, JP).

Fabrication of smart contact lens

First, a double loop coil, gold antenna, 3 mm in radius, was fabricated, and a capacitor (Cs = 68 pF) was connected in parallel to achieve a resonant frequency of 70 MHz. The initial impedance of the coil was 1.2 KΩ. Next, two gold wires are connected to each end of a multilayer structured PEDOT sensor as electrodes. These electrodes are attached to the sensor structure using PEDOT/PVA glue to secure the electrodes (Fig. S10). The use of silver adhesive was avoided due to the cytotoxicity of silver nanoparticles52. Subsequently, the gold electrodes at both ends of the sensor were connected to the antenna to ensure the integrity of the entire sensor system. Finally, the complete sensor system was placed into a 3D printed contact lens mold (Formlabs Form 3+). Next, a PDMS prepolymer with a base-to-curing agent ratio of 20:1 was poured into the mold. Curing was done at 70 °C for 3 h to ensure perfect integration of the sensors and wireless transmission system on the PDMS contact lens.

Fabrication of the conventional loss antenna

The conventional antenna is fabricated using a copper wire wound into two loops with a diameter of 38 mm (wire diameter: 0.216 mm).

Fabrication of PCB board for P-T symmetric antenna

The wireless detection coil of the P-T parallel resonance circuit is fabricated using PCB manufacturing technology in our lab. Firstly, the circuit diagram is designed to define the components and connections required for the PCB. Secondly, a dry film is applied to the surface of the PCB substrate to prepare for the subsequent image transfer. Thirdly, the circuit diagram is transferred onto the PCB substrate through a photolithography process, utilizing UV exposure to create the desired pattern. Next, a NaOH solution is used to remove the excess resist coating, exposing the non-circuit copper layers. Lastly, the etching process is carried out using a chemical displacement reaction with FeCl2 to selectively corrode the non-circuit areas of the copper layer, leaving behind the desired circuit pattern. Finally, we need to perform drilling and electronic component soldering on the PCB board to accommodate the insertion of electronic components and form electrical connections. After the drilling process, electronic components such as resistors and capacitors are soldered onto the PCB board. The parameters of each electronic component used are as follows: inductor (L1 = 32 nH), the BJT transistor (c1815gr), bias resistors (R1 = 4.7 KΩ, R2 = 2.2 KΩ), source resistor (R3 = 120 Ω), source capacitor (C1 = 120 pF), bypass capacitors (C2 = 220 pF, C3 = 100 pF), and oscillation capacitors (C4, C6 = 150 pF, C5 = 50 + 10 ~50 pF). The SMA connector is connected to both ends of L1. The circuit schematic of the gain resonator (Clapp oscillator circuit) is shown in Fig. S11. The final resonant frequency of the antenna is 70 MHz.

Sensor resistance testing on the PDMS eye model

A mixed solution of a Sylgard 184 silicone elastomer kit (10:1) was poured into a hemisphere mold (304 2.0 thick hemisphere, PERSON) made of stainless steel, which was then pressed with a metallic ball to create an eye shape. After heating at 150 °C for 5 min, the hemisphere PDMS film was removed from the mold and mounted onto the planar PDMS film. Subsequently, it was sealed with PDMS and cured at 70 °C for 5 h to make a PDMS eye model. The inner pressure of the combined PDMS films and the hemisphere cavity is controlled with a syringe pump (FP-1100, Melquest) connected to a pressure sensor (PS-9302, FUSO). The syringe pump can inject 154 mM saline solution into the PDMS model eye. A sensor was placed on the balloon with both ends connected to a source meter (Keithley 2450) to record the change in resistance as the balloon expanded.

IOP monitoring on the PDMS eye model

The IOP sensing lens was mounted onto the model eye, and a vector network analyzer (MS46122B, Anritsu) was used to measure the impedance variation.

IOP monitoring on porcine eyes

We purchased fresh porcine eyes. In the same manner as in the PDMS eye model experiments, the eyes were attached to the syringe pump system to control the IOP from 6 mmHg to ~ 36 mmHg. The modulated IOP was monitored by a wireless system consisting of a sensing lens and reader circuit. The iCare TONOVET Plus tonometer (USA) was used to explore the relationship between intraocular pressure and contact lens resistance data.

IOP monitoring in vivo test

Firstly, to anesthetize the rabbit, a mixture of general anesthetic agents was administered via intramuscular injection. The mixture consisted of 0.15 mg/kg medetomidine hydrochloride (Domitor; Nippon Zenyaku Kogyo, Japan), 1 mg/kg midazolam (Dormicum; Maruishi Pharmaceutical, Japan), and 1.5 mg/kg butorphanol tartrate (Betlfal; Meiji Animal Health, Japan). After the rabbit was fully anesthetized (about 15 min), we used a handheld tonometer (iCare TonoLab TV02, M.E. Technica) to measure the rabbit’s eye’s intraocular pressure three times and recorded the average value. Next, we placed contact lenses into the rabbit’s eyes and fitted the P-T symmetry reader PCB board in front of the rabbit’s eye using a 3D-printed container and a headband. During the measurement, a robotic script (Yingdao, Inc., China) was used to store data every 5 s. Measurements were taken for 10 min on each eye. Each data point shows the mean value of 30 measurements, with the error bars indicating the standard deviation. After 10 min, the contact lenses were removed, and the IOP was measured three times again using the tonometer, with the average value recorded. Then, 0.6 mL of purified sodium hyaluronate (Healon Ophthalmic Viscoelastic Substance 1% syringe, Japan) was injected to rapidly increase the IOP in the rabbit eye. The same IOP measurement procedures were repeated. A follow-up measurement was performed 2 days later, after the IOP had recovered. No euthanasia was performed in this study. All rabbits fully recovered after the experiments.

Safety of the IOP measurement system

The temperature imaging maps around the contact lens and P-T antenna were taken by FLIR C3, CAN, with the legend corresponding to the colors.

Assessment of ocular cell viability

First, the obtained HCEs (Cell Science & Technology Institute, Inc., Japan) are introduced into DMEM/F12 culture medium and cultured separately for 24 h and 48 h in a humidified incubator set to 37 °C with 5% CO₂. After performing one waste liquid extraction, the culture dish is tilted. Subsequently, 0.5 mL of DMEM/F12 culture medium is added, followed by another waste liquid extraction. Next, 0.5 mL of Trypsin (Cell Science & Technology Institute, Inc., Japan) is added, and the cells are allowed to rest for 5 min. Following this, three rinses are performed, transferring the extracted liquid to a new tube. An additional 0.5 mL of culture medium is added, drawing all the liquid into the tube. The tube is then centrifuged at a speed of 150 RPM for 5 min. After centrifugation, the supernatant is extracted and discarded. Finally, the culture medium is added to the tube and gently mixed from the bottom. Then, 50 µL of liquid is extracted and transferred to a small tube. Subsequently, 50 µL of Trypan Blue (Gibco by Thermo Fisher Scientific, Japan) is added and mixed, and then 10 µL is taken out and placed on a substrate (Fig. S12). Lastly, cell viability is assessed using the TC20 Automated Cell Counter (Bio-Rad Laboratories, Inc., USA).

The PEDOT: PSS sensor was placed in a culture dish containing HCEs and incubated in the incubator for 24, 48, and 72 h. Cells were stained with calcein dye and PI, and then visualized by confocal Microscope (OLYMPUS FLUOVIEW FV3000, JP) for cell survival.

Ethics approval

The rabbit experiments were approved by the Animal Ethics Committee of the Yamaguchi University Graduate School of Medicine (Approval No. 41-003). The experiments were conducted in accordance with the ARRIVE guidelines for animal research and the ARVO Statement for the Use of Animals in Ophthalmic and Vision Research.

Data availability

The data that support the plots in this paper and other findings of this study are available from the corresponding authors upon reasonable request.

References

Lee, D. A. & Higginbotham, E. J. Glaucoma and its treatment: a review. Am. J. Health Syst. Pharm. 62, 691–699 (2005).

Haleem, M. S., Han, L., Van Hemert, J. & Li, B. Automatic extraction of retinal features from colour retinal images for glaucoma diagnosis: a review. Comput. Med. Imaging Graph. 37, 581–596 (2013).

Susanna, R., De Moraes, C. G., Cioffi, G. A. & Ritch, R. Why Do People (Still) Go Blind from Glaucoma?. Transl. Vis. Sci. Technol. 4, 1 (2015).

Arrigo, A. et al. Cognitive dysfunctions in glaucoma: an overview of morpho-functional mechanisms and the impact on higher-order visual function. Front. Aging Neurosci. 13, 747050 (2021).

Tejwani, S., Dinakaran, S., Joshi, A., Shetty, R. & Roy, A. A cross-sectional study to compare intraocular pressure measurement by sequential use of Goldman applanation tonometry, dynamic contour tonometry, ocular response analyzer, and Corvis ST. Indian J. Ophthalmol. 63, 815 (2015).

Yang, C. et al. Wearable and implantable intraocular pressure biosensors: recent progress and future prospects. Adv. Sci. 8, 2002971 (2021).

Shin, H. et al. Recent progress on wearable point-of-care devices for ocular systems. Lab. Chip 21, 1269–1286 (2021).

Farandos, N. M., Yetisen, A. K., Monteiro, M. J., Lowe, C. R. & Yun, S. H. Contact lens sensors in ocular diagnostics. Adv. Healthc. Mater. 4, 792–810 (2015).

Azhari, S., Méhes, G. & Miyake, T. Wireless biosensors for healthcare: smart contact lenses and microbial devices. In Wearable Biosensing in Medicine and Healthcare (Springer, 2024).

Leonardi, M., Leuenberger, P., Bertrand, D., Bertsch, A. & Renaud, P. First steps toward noninvasive intraocular pressure monitoring with a sensing contact lens. Investig. Opthalmol. Vis. Sci. 45, 3113 (2004).

Agaoglu, S. et al. Ultra-sensitive microfluidic wearable strain sensor for intraocular pressure monitoring. Lab. Chip 18, 3471–3483 (2018).

An, H. et al. Microfluidic contact lenses for unpowered, continuous and non-invasive intraocular pressure monitoring. Sens. Actuators Phys. 295, 177–187 (2019).

Song, C., Ben-Shlomo, G. & Que, L. A multifunctional smart soft contact lens device enabled by nanopore thin film for glaucoma diagnostics and in situ drug delivery. J. Microelectromech. Syst. 28, 810–816 (2019).

Maeng, B., Chang, H. & Park, J. Photonic crystal-based smart contact lens for continuous intraocular pressure monitoring. Lab. Chip 20, 1740–1750 (2020).

Yuan, M. et al. High-sensitive microfluidic contact lens sensor for intraocular pressure visualized monitoring. Sens. Actuators Phys. 354, 114250 (2023).

Li, Y. et al. A novel implantable piezoresistive microsensor for intraocular pressure measurement. ACS Sens 9, 3958–3966 (2024).

Takamatsu, T., Chen, Y., Yoshimasu, T., Nishizawa, M. & Miyake, T. Highly efficient, flexible wireless-powered circuit printed on a moist, soft contact lens. Adv. Mater. Technol. 4, 1800671 (2019).

M. Kouhani, M. H., Wu, J., Tavakoli, A., Weber, A. J. & Li, W. Wireless, passive strain sensor in a doughnut-shaped contact lens for continuous non-invasive self-monitoring of intraocular pressure. Lab. Chip 20, 332–342 (2020).

An, H. et al. High-sensitivity liquid-metal-based contact lens sensor for continuous intraocular pressure monitoring. J. Micromech. Microeng. 31, 035006 (2021).

Chen, G.-Z., Chan, I.-S., Leung, L. K. K. & Lam, D. C. C. Soft wearable contact lens sensor for continuous intraocular pressure monitoring. Med. Eng. Phys. 36, 1134–1139 (2014).

Li, X. et al. Temperature self-compensating intelligent wireless measuring contact lens for quantitative intraocular pressure monitoring. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 16, 22522–22531 (2024).

Lin, Y. et al. Magneto-elastic for wireless intraocular pressure monitoring. Chem. Eng. J. 498, 155357 (2024).

Chiou, J.-C., Huang, Y.-C. & Yeh, G.-T. A capacitor-based sensor and a contact lens sensing system for intraocular pressure monitoring. J. Micromech. Microeng. 26, 015001 (2016).

Kim, J. et al. Wearable smart sensor systems integrated on soft contact lenses for wireless ocular diagnostics. Nat. Commun. 8, 14997 (2017).

Yang, C. et al. Intelligent wireless theranostic contact lens for electrical sensing and regulation of intraocular pressure. Nat. Commun. 13, 2556 (2022).

Zhang, J. et al. Smart soft contact lenses for continuous 24-hour monitoring of intraocular pressure in glaucoma care. Nat. Commun. 13, 5518 (2022).

Zhu, H. et al. Hydrogel-based smart contact lens for highly sensitive wireless intraocular pressure monitoring. ACS Sens 7, 3014–3022 (2022).

Yang, H. et al. Intraocular pressure monitoring smart contact lens with high environmental stability. Adv. Funct. Mater. 34, 2400722 (2024).

Kim, J. et al. Intraocular pressure monitoring following islet transplantation to the anterior chamber of the eye. Nano Lett. 20, 1517–1525 (2020).

Xu, J. et al. Highly transparent and sensitive graphene sensors for continuous and non-invasive intraocular pressure monitoring. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 12, 18375–18384 (2020).

Dou, Z. et al. Wearable contact lens sensor for non-invasive continuous monitoring of intraocular pressure. Micromachines 12, 108 (2021).

Kim, T. Y. et al. Smart contact lenses with a transparent silver nanowire strain sensor for continuous intraocular pressure monitoring. ACS Appl. Bio Mater. 4, 4532–4541 (2021).

Kim, T. Y. et al. Wireless theranostic smart contact lens for monitoring and control of intraocular pressure in glaucoma. Nat. Commun. 13, 6801 (2022).

Karunaratne, I. K. et al. Wearable dual-element intraocular pressure contact lens sensor. Sens. Actuators Phys. 321, 112580 (2021).

An, H. et al. LC contact lens sensor for ultrasensitive intraocular pressure monitoring. npj Flex. Electron. 8, 53 (2024).

Hu, L. et al. Electrochromic soft contact lenses with built-in non-interfering, high-efficient dual-band wireless power transfer system. Sens. Actuators Phys. 344, 113766 (2022).

Takamatsu, T., Sijie, Y. & Miyake, T. Wearable, implantable, parity-time symmetric bioresonators for extremely small biological signal monitoring. Adv. Mater. Technol. 8, 2201704 (2023).

Xia, Y., Sun, K. & Ouyang, J. Solution-processed metallic conducting polymer films as transparent electrode of optoelectronic devices. Adv. Mater. 24, 2436–2440 (2012).

Yousefian, H. et al. Beyond acid treatment of PEDOT:PSS: decoding mechanisms of electrical conductivity enhancement. Mater. Adv. 5, 4699–4714 (2024).

Fan, Q. et al. The mechanism of enhancing the conductivity of PEDOT: PSS films through molecular weight optimization of PSS. Prog. Org. Coat. 189, 108308 (2024).

Hu, L. et al. Multi-electrode electroretinography with transparent microelectrodes printed on a soft and wet contact lens. Adv. Mater. Technol. 2400075 https://doi.org/10.1002/admt.202400075 (2024).

Romyen, N., Thongyai, S., Praserthdam, P. & Sotzing, G. A. Enhancement of poly(3,4-ethylenedioxy thiophene)/poly(styrene sulfonate) properties by poly(vinyl alcohol) and doping agent as conductive nano-thin film for electronic application. J. Mater. Sci. Mater. Electron. 24, 2897–2905 (2013).

Cao, W. et al. Fully integrated parity–time-symmetric electronics. Nat. Nanotechnol. 17, 262–268 (2022).

Sakhdari, M. et al. Experimental observation of P T symmetry breaking near divergent exceptional points. Phys. Rev. Lett. 123, 193901 (2019).

Liu, G. & Zhang, B. Dual-coupled robust wireless power transfer based on parity-time-symmetric model. Chin. J. Electr. Eng. 4, 50–55 (2018).

Choi, Y., Hahn, C., Yoon, J. W. & Song, S. H. Observation of an anti-PT-symmetric exceptional point and energy-difference conserving dynamics in electrical circuit resonators. Nat. Commun. 9, 2182 (2018).

Mansour, M. & Mansour, I. Triple bands Class-C voltage-controlled power oscillator based on high-quality factor asymmetry inductor. Microelectron. J. 116, 105251 (2021).

Basics of PT Symmetry. in PT Symmetry 3–38 https://doi.org/10.1142/9781786345967_0001 (WORLD SCIENTIFIC, 2018).

Özdemir, ŞK., Rotter, S., Nori, F. & Yang, L. Parity–time symmetry and exceptional points in photonics. Nat. Mater. 18, 783–798 (2019).

Zhang, B. et al. High-efficient and dosage-controllable intracellular cargo delivery through electrochemical metal–organic hybrid nanogates. Small Sci. 1, 2100069 (2021).

Downs, J. C. IOP telemetry in the nonhuman primate. Exp. Eye Res. 141, 91–98 (2015).

Liao, C., Li, Y. & Tjong, S. C. Bactericidal and cytotoxic properties of silver nanoparticles. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 20, 449 (2019).

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by AMED under Grant No. JP23hma322020, the Canon Foundation, and Grant-in-Aid for Scientific Research A under Grant No. 24H00805. Part of this work was conducted at Kitakyushu Foundation for the Advancement of Industry, Science and Technology, Semiconductor Center, supported by “Nanotechnology Platform Program” of the Ministry of Education, Culture, Sports, Science and Technology (MEXT), Japan.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

T.X. and H.Z. contributed equally to this work: investigator, data curation, writing—original draft, writing—review and editing and T.T. Investigator, data curation and A.A. Investigator, writing—review and editing and S.A. Investigator, data curation, writing—review and editing and K.K. Writing—review and editing, funding acquisition and T.M. Conceptualization, investigator, data curation, writing—original draft, writing—review and editing, funding acquisition.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Xiao, T., Zhang, H., Takamatsu, T. et al. Ultra-sensitive real-time monitoring of intraocular pressure with an integrated smart contact lens using parity-time symmetry wireless technology. npj Flex Electron 10, 4 (2026). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41528-025-00507-3

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41528-025-00507-3