Abstract

Conductive putty-like polymer composites have recently received considerable attention in wearable electronics, soft robotics, and energy storage due to their unique electrical and mechanical properties. Their viscoelasticity enables direct 3D printing of intricate, customizable conductive pathways, yet printing in high-viscosity polymer solutions remains challenging. Inspired by clay, we develop a moldable conductive polymer composite (MCPC) with tunable viscoelasticity, shear-thinning behavior, and high conductivity by blending liquid Ecoflex with graphite powders. By extruding MCPC onto liquid Ecoflex of various viscosities, we demonstrate a facile strategy for fabricating soft sensors with spatially controlled conductive pathways. These sensors exhibit a wide strain response (0.05%-150%), high sensitivity (gauge factor >15000), and nearly 100% electrical repeatability over 1000 cycles. They reliably monitor human movement and control robotic hands. Our approach provides a new strategy for fabricating soft sensors with enhanced mechanical and electrical properties, expanding possibilities for next-generation wearable and bio-integrated technologies.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Soft sensors have gained significant attention in recent years due to their mechanical properties similar to biological tissues and ability to conform to complex geometries. These sensors play a crucial role in a wide range of applications, including wearable devices1,2, electronic skin (e-skin)3,4, display and lighting technologies5,6, and energy storage devices7,8, each significantly impacting modern society and enhancing quality of life. The function of soft sensors largely relies on their ability to convert mechanical deformation into electric signals. As a core component, the quality of soft sensors, such as detection sensitivity, mechanical stretchability and durability, and working strain range, critically influences overall device performance9,10. To meet the demands of next-generation electronics, researchers have explored various materials and fabrication strategies to develop soft, stretchable, and highly sensitive sensors that can sustain large deformations while maintaining stable electrical performance.

To achieve electrical conductivity in soft sensors, various conductive materials have been incorporated. Conventional conductive materials, such as metal films and carbon-based materials, need to be integrated onto stretchable substrates to impart mechanical flexibility. Directly depositing conductive materials onto the elastomer surface is the most straightforward and commonly used method11. To enhance the adhesion between the conductive layer and elastomer matrix, several surface pre-treatment methods (e.g., dopamine modification and plasma treatment) have been developed12,13. Transfer printing is another widely used technique which utilizes the fluidity of uncured polymer solutions to facilitate the encapsulation transfer of the conductive layer from a support surface into cured elastomer14. However, the limited intrinsic stretchability of conventional conductive materials often leads to mechanical failures under large deformations. Various strategies have been developed to expand the working range, such as creating a wrinkled conductive layer15,16, adopting complex conductive patterns17, and introducing networked cracks18,19. Stretchable conductive materials, including conductive polymers20,21, conductive polymer composites22,23, and nanomaterial-infused elastomers24, have also been developed to fundamentally address this limitation. Additionally, to enhance the durability of soft sensors, healable conductive materials have emerged, allowing for the repair of electrical conductivity after mechanical damage and effectively extending the sensor’s lifespan.

A unique class of conductive materials that has recently attracted interest is moldable conductive materials. In contrast to conventional conductive materials and stretchable conductive materials enabled by crosslinked polymer networks which exhibit predominantly elastic behavior with limited moldability25, moldable materials demonstrate enhanced viscous behavior, allowing them to deform plastically under stress and easily assume various shapes, resembling materials like silly putty26. Their superior viscoelasticity not only renders their healing properties and adaptable shape modulation in response to specific application requirements27, but also enables the fabrication of complex and customized designs with high precision through 3D printing28. To make stretchable electronics, conductive pathways can be directly printed onto a solid substrate and then transferred to combine with a stretchable matrix. To eliminate the transfer process, embedded printing has been developed, where conductive materials are printed within a low-viscosity elastomer solution, such as PDMS29,30. However, challenges remain in achieving successful 3D printing in high-viscosity polymer solutions due to difficulties in maintaining print fidelity.

In this study, we present a novel moldable conductive polymer composite (MCPC) by mixing graphite into Ecoflex elastomer solution. Our MCPC exhibits higher electrical conductivity than existing carbon-based conductive viscoelastic polymers and a superior healing capability (see Supplementary Table 1). With this composite, we demonstrate an adaptive 3D printing method in which the conductive filament is extruded onto the surface of uncured elastomer solution. This approach eliminates the transfer process required for the conductive pathways printed on solid substrates and meanwhile overcomes the viscosity limitations of embedded 3D printing, enabling simplified and effective integration with high-viscosity elastomers (Supplementary Movie 1). The spatial positioning of these conductive pathways is precisely controlled by adjusting the precipitation of printed filaments within the elastomer matrix, forming both fully and partially encapsulated MCPC structures in the elastomer matrix, which can readily function as a stretchable strain sensor. Our soft sensor demonstrates a wide working strain range and high sensitivity simultaneously, and exhibits significant potential for monitoring various human movements. Our approach offers a new avenue for fabricating stretchable, durable, and highly sensitive soft sensors with customizable designs.

Results

Preparation and characterization of MCPC

Inspired by the moldable clay dough made by mixing soil particles with water in right ratios, we develop a MCPC by mixing liquid Ecoflex00–10 silicone with graphite powders (Supplementary Fig. 1). Micro-sized graphite powders (Supplementary Fig. 2) are directly mixed with commercial Ecoflex00–10 silicone at various ratios, including 0, 10, 20, 30, 40, and 50 wt.%, without any modification. Interestingly, the polymer composite exhibits a clear transition from crosslinked to clay-like uncured solid when the graphite concentration is beyond 20 wt.%. This shift is accompanied by significant changes in mechanical properties. The macro and micro-scale morphologies of the different polymer composites reveal that roughness and micro-agglomeration intensify with increasing graphite content (Fig. 1A). Our compression measurements using polymer composite samples with a cylindrical structure further confirm this mechanical state transition, as shown in Fig. 1B. The polymer composite exhibits an increasingly higher compression modulus as graphite content increases from zero to 10 wt.% and 20 wt.%, because the graphite powders behave as rigid inclusions in the soft crosslinked polymer matrix31. However, the stiffness of the polymer composite sharply drops to a level even lower than the pure Ecoflex polymer when 30 wt.% graphite is added into Ecoflex, suggesting that a crosslinked polymer network fails to form. As more graphite is added, the increased interaction among graphite particles enhances shear resistance, thereby increasing the compression load needed for the same compression distance.

A Representative optical images showing the state transitions of various polymer composites after prolonged air exposure. The zoomed-in views are representative SEM images showing the surface morphologies. Scale bars: 10 mm and 50 μm in the optical and SEM images, respectively. B Load responses of various polymer composites under a compression strain increasing from 0 to 0.5. C Nuclear magnetic resonance (NMR) spectra (1D 13C) of different samples. D Schematic illustration of the polymer network structures in polymer composites with low (≤20 wt.%) and high (>20 wt.%) graphite contents. E Variation of conductivity with increasing graphite content in polymer composites. F Electrical response of polymer composites under a compression strain increasing from 0 to 0.5. G Viscosity of polymer composites with varying graphite content.

The disruption of the crosslinking reaction of Ecoflex silicone by graphite is further confirmed by our rheological measurements. As a platinum (Pt)-catalyzed product, Ecoflex silicone undergoes spontaneous curing via a time-dependent chemical reaction once its Part A and Part B are mixed together32. As curing progresses, the tan(δ), defined as the ratio of loss modulus to storage modulus, of liquid Ecoflex monotonically decreases from 10 to less than 1 within 90 mins (Supplementary Fig. 3A), suggesting a liquid-to-solid transition as a result of the continuous crosslinking reaction. The polymer becomes fully cured after 120 min. However, when graphite is added to the liquid Ecoflex to 30 wt.%, the decrease in tan(δ) is significantly less pronounced (Supplementary Fig. 3B). Notably, even after 1440 min, the polymer composite remains in a semi-cured state with a tan(δ) around 1. The results demonstrate that graphite indeed influences the crosslinking process of Ecoflex silicone. At low filler concentrations, the influence is insufficient to significantly disrupt the curing network. This explains why many previous studies using ≤20 wt.% of such fillers in Pt-catalyzed silicones did not report similar behavior (Supplementary Table 2). In contrast, high graphite loadings appear to hinder the crosslinking reaction more substantially.

To investigate the underlying mechanism that causes the mechanical state transition of Ecoflex, we replace graphite with several other fillers, including sugar, starch, NaCl and liquid metal. Unlike graphite powders, Ecoflex is able to fully cure when other particles are used as fillers (Supplementary Table 3), which excludes the possibility that a crosslinked network failed to form due to the incomplete covering of the fillers by the liquid polymer. Additionally, we mix graphite with various liquid polymers (Supplementary Table 4). All the Smooth-On series polymers (Ecoflex00–10, Ecoflex00–30, Ecoflex00–50, and Dragon skin) remain in a semi-cured state even after one year and the Sylgard™ series eventually solidify after an extended crosslinking time (from within 12 h to more than 48 h), while Room Temperature Vulcanizing silicones (RTV, 734 CLEAR 310 ML, Dow) cure without any noticeable changes. Considering that both Smooth-On and Sylgard™ series polymers are Pt-catalyzed, our results suggest that graphite specifically interfered the Pt-catalyzed crosslinking reaction of Smooth-On and Sylgard™ series polymers.

To investigate the mechanism by which graphite content affects the state of Ecoflex00–10 silicone, we conduct elemental and phase analyses at the microscopic level. The XPS survey spectra in Supplementary Fig. 4 and the FTIR spectra in Supplementary Fig. 5 show that the incorporation of graphite into Ecoflex polymer does not introduce any new chemical elements or absorption peaks, excluding the possibility of catalyst poisoning of the Ecoflex00–10 silicone or new chemical reactions. The molecular structures of various samples are characterized using NMR analysis. As shown in Fig. 1C, a shape “CH3” peak, representing the methyl group, is observed around 0.8 ~ 1.0 ppm on the chemical shift scale for Ecoflex Part A, Ecoflex Part B, and the fully cured Ecoflex with both Part A and Part B. The appearance of the “CH3” peak is consistent with the existence of methyl groups in these three samples33. With the addition of 50 wt.% graphite, the chemical shift position shifts and the peak broadens, which reflect changes in the polymer chains’ microenvironment due to the interactions between the polymer sidechains and graphite. In principle, the peak broadening can be attributed to two possible factors34,35: an increase in amorphousness and a decrease in side-chain dynamics. Considering that our polymer composite is an amorphous material, the observed peak broadening should be due to the decrease in side-chain dynamics. As illustrated in Fig. 1D, the reduced side-chain dynamics can be caused by π-CH hydrogen bond interactions36,37, which significantly reduces the flexibility and polymer chain dynamics of the Ecoflex. Our results suggest that the reduced mobility and flexibility of the CH3 side chains can limit the polymerization reaction and consequently result in a clay-like polymer composite, although the CH3 group does not directly participate in the crosslinking reaction. However, at low graphite contents, the dispersed fillers only locally disrupt the crosslinking reaction and therefore do not prevent Ecoflex00–10 silicone from being fully cured.

The conductivity of Ecoflex-graphite composite is also highly dependent on the graphite content. As depicted in Fig. 1E, when the graphite content is no more than 20 wt.%, the polymer composite is not conductive. With 30 wt.% graphite, the composite becomes conductive, albeit with a low conductivity value. As the graphite content increases further to 40 and 50 wt.%, the conductivity rises exponentially, resulting in an order of magnitude difference. More importantly, the conductivity of the conductive composite changes in response to mechanical compression (Fig. 1F), although the polymer composite with less than 20 wt.% graphite remains non-conductive. As compression strain increases from 0 to 50%, the samples with 30 wt.% and 40 wt.% graphite display a monotonic drop in resistance, whereas the sample with 50 wt.% graphite exhibits a resistance trend that initially decreases, then remains stable, and finally increases. In theory, assuming that the polymer composite is incompressible and has a constant resistivity, the resistance of a cylindrical conductive sample should vary under compression following the equation: \(R={R}_{0}{\left(1-\varepsilon \right)}^{2}\), where \({R}_{0}\) and ε are the initial resistance and the compression strain along the longitudinal direction, respectively. The clear mismatch between our experimental results in Fig. 1F and the predicted results in Supplementary Fig. 6 suggests that the resistivity may change during compression. The initial compression may lead to a reduction in the distance between graphite particles, which reduces the resistivity of our MCPC. At a high compression level, the particle distance may become too short to further change, and cracks are observed in the sample with 50 wt.% graphite (see the inset of Fig. 1F), leading to an increase in resistance.

Additionally, the viscosity of the polymer composite with more than 20 wt.% graphite shows shear-thinning behavior (Fig. 1G), suggesting their potential as extrusion-based 3D printing inks. Supplementary Fig. 7 illustrates the printability of the composites. The surfaces of the printed filaments with 30 and 40 wt.% graphite are smooth, while the composite with 50 wt.% graphite exhibits a relatively rougher surface.

Our conductive polymer composites are highly moldable, even for the one with 50 wt.% graphite. The composite can be easily shaped into various shapes through hand kneading, as shown in Fig. 2A. The electrical resistance of the composite varies with changes in the sample’s shape. As demonstrated in Fig. 2B, the MCPC sample with a cylindrical structure illustrates a consistent increase in electrical resistance as the sample’s diameter decreases while maintaining its volume, but the intrinsic resistivity of the MCPC remains roughly consistent across different shapes (Supplementary Fig. 8). The relatively larger resistivity of the first shape is likely due to the weaker compressive densification during our kneading, as stronger compression is needed to make samples with smaller diameters. Another key characteristic of the MCPC is its physical healing capability. As shown in Fig. 2C, after the sample with a spherical structure is cut into two pieces, the two parts are able to adhere to each other and perfectly heal with a gentle finger touch applying approximately 500 kPa of pressure for a few seconds. As illustrated in Fig. 2D, the dynamic healing process may be facilitated by the π–π stacking interactions between graphite, π–CH interactions between graphite and polymer chains, and the interdiffusion of polymer chains38.

A Four representative shapes formed using the same MCPC. Scale bars: 10 mm. B Variation in electrical resistance associated with the shape change of the MCPC. C Representative optical and SEM images showing the morphologies of the MCPC during cutting and healing process. Scale bars: 10 mm and 250 μm in the optical and SEM images, respectively. D Schematic diagram illustrating the molecular mechanisms underlying the healing process. E Electrical resistance changes during a single cutting-and-healing process. F Electrical resistance changes recorded over 100 cutting-and-healing cycles.

The electrical resistance changes during a single cutting-and-healing cycle are recorded in Fig. 2E. As the cutting gets increasingly deeper, the resistance increases monotonically, reaching infinity when the specimen is fully separated. Remarkably, conductivity is immediately restored upon re-attachment of the separated specimens, and the electrical property returns to the initial level after gentle hand kneading. These results suggest that the graphite particles rapidly reform the percolation network upon contact, without the need for diffusion and re-orientation. We extend the cutting-and-healing cycle to 100 times and observe that the electrical resistance of the MCPC can be fully restored even after 100 cycles (Fig. 2F).

Adaptive 3D printing of MCPC

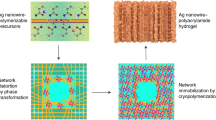

To use our MCPC for stretchable soft electronics, adaptive 3D printing is developed to integrate the MCPC with an elastomeric matrix. We directly print MCPC onto the surface of uncured Ecoflex solution. Given that the density of the polymer composite consistently increases with the addition of graphite (Supplementary Fig. 9), the printed filament of Ecoflex-graphite composite is expected to gradually sink into the Ecoflex solution and may be fully immersed eventually (Supplementary Fig. 10). The final vertical position of the filament can be controlled by manipulating the interplay among gravity \(({F}_{G})\), buoyancy \(({F}_{b})\) and viscous drag forces \(({F}_{D})\), as illustrated in Fig. 3A. For simplicity, we treat a small segment of the printed filament as a cylindrical particle and assume the inertial effect of the flow is negligible compared to the viscous force. The gravitational force remains constant throughout the sedimentation process, given by \({F}_{G}={\rho }_{P}g{V}_{P}\), where \({\rho }_{P}\) is the density of the MCPC, g is gravitational acceleration, and \({V}_{P}\) is the volume of the filament, calculated as \({V}_{P}=L\pi {R}^{2}\), where L and R are the length and radius of the filament, respectively. The buoyancy can be calculated based on Archimedes’ principle: \({F}_{b}={\rho }_{L}g{V}_{{disp}}\), where \({\rho }_{L}\) and \({V}_{{disp}}\) are the density of the liquid polymer and the displaced volume of the polymer liquid by the filament, respectively. The drag force can be approximated by the Stokes’ law as: \({F}_{D}=\frac{1}{2}{C}_{D}{\rho }_{L}{v(t)}^{2}A\), where \({C}_{D}\) is drag coefficient, v is the velocity of the cylindrical particle relative to the polymer solution, and A is the projected area of the particle onto the flow direction. Note that \({C}_{D}\approx \frac{12\mu }{R{\rho }_{L}v(t)}\), where μ is the viscosity of liquid Ecoflex. The continuous crosslinking of Ecoflex polymers results in a time-dependent viscosity: \(\mu ={\mu }_{0}{e}^{0.0445t}\) (Supplementary Fig. 11), where \({\mu }_{0}\) is the viscosity at the start of curing reaction39. Both \({V}_{{disp}}\) and A depend on the sedimentation depth h of the filament and their analytical relations can be easily derived at different stages illustrated in Fig. S10. Thus, the velocity of the cylindrical particle during sedimentation is governed by \({\rho }_{P}{V}_{P}\frac{{dv}(t)}{{dt}}={\rho }_{P}g{V}_{P}-{\rho }_{L}g{V}_{{disp}}-\frac{1}{2}{C}_{D}{\rho }_{L}{v(t)}^{2}A\). The sedimentation depth can then be determined as \(h\left(t\right)={\int }_{0}^{t}v(t){dt}\). As shown in Supplementary Fig. 12, v is predicted to rapidly increase from zero to its maximum value within a few seconds and then gradually decreases to zero as the liquid Ecoflex cures, while h initially increases sharply and then transitions to a slower rate of increase before eventually stabilizing at the final depth. It is predicted that the sedimentation depth reduces with the increase in the pre-curing time (Supplementary Fig. 12B), which is successfully verified experimentally (Fig. 3B). Our understanding is further verified through finite element simulations. By utilizing the viscosity of liquid Ecoflex at various pre-curing time (refer to Supplementary Fig. 11), we successfully replicate the corresponding vertical displacements observed in our experiments (Fig. 3B).

A Schematic illustration of the working principle of the adaptive 3D printing. B Variations in sedimentation displacement of the extruded filament in Ecoflex liquids with different viscosities with experimental results on the left and COMSOL simulation results on the right. C Optical images of a right-angle pattern printed on the surface of Ecoflex liquids with varying viscosities using the same printing parameters. Scale bar: 10 mm. D Optical images of a right-angle pattern printed on the surface of Ecoflex liquids with a constant viscosity using different extrusion pressures. Scale bar: 10 mm. E Simulation results of the displacement of a printed filament with right-angle pattern in liquids with varying viscosities or under different \({F}_{m}\). F Optical images of various MCPC patterns printed with optimized parameters. Scale bar: 5 mm.

In addition to the vertical configuration, the printing resolution in the horizontal plane is also systematically examined. When the nozzle movement velocity \(({v}_{{nozzle}})\) differs from the extrusion velocity \(({v}_{{extrusion}})\), a tensile or compressive force \(({F}_{m})\) is induced along the printing path. This can result in filament thinning or breakage when \({v}_{{nozzle}}\) is faster, or material buildup when it is slower (Supplementary Fig. 13). This force arises from the adhesion and shear force between the extruded MCPC filament and the uncured polymer substrate and its magnitude is positively correlated with \(|\frac{{v}_{{nozzle}}-{v}_{{extrusion}}}{{v}_{{extrusion}}}|\), leading to the movement of extruded filament, which in turn induces a drag force from the uncured Ecoflex. Figure 3C illustrates that, under the same \({v}_{{extrusion}}\) (air pressure ≈ 150 kPa), the designed right-angle model becomes more distorted and curved on the liquid Ecoflex with a lower viscosity (i.e., shorter pre-curing time). A similar result is predicted by finite element simulations under the same \({F}_{m}\) (see Fig. 3E), confirming that a sufficiently high viscosity of the underlying Ecoflex is required to reliably generate the intended pattern. Figure 3D displays a right-angle pattern printed onto Ecoflex with a 30 min pre-curing time under various air pressures (i.e., \({v}_{{extrusion}}\)). The results demonstrate that at a lower air pressure (125 kPa), the extruded filament is hard to maintain its smoothness and integrity. The designed pattern becomes distorted, with shorter lengths and curved angles due to the low extrusion velocity. At excessively high air pressure (200 kPa), over-extrusion results in distorted curves instead of the intended straight lines. Only at the intermediate air pressure (175 kPa) does the printed pattern closely match the designed pattern, with the filament remaining smooth and intact. Our understanding is also validated through finite element simulations. With the same viscosity of the liquid Ecoflex, distinct distortion patterns are predicted under tensile and compressive forces, resembling the printed patterns under low and high pressures (Fig. 3E). Using optimized printing parameters (30-minute pre-curing of the Ecoflex and 175 kPa air pressure during printing), we successfully print various more complex conductive patterns, including a flower, cross, network and spider web, with a semi-embedded structure in the elastomer matrix, as displayed in Fig. 3F.

Electrical responses of the integrated structure

Semi-embedding or fully embedding MCPC into an elastomer matrix using adaptive 3D printing allows us to explore these structures as strain sensors. As depicted in Fig. 4A, the π–CH interactions between the graphite in MCPC and the polymer chains in the matrix and the interdiffusion of polymer chains between MCPC and the matrix ensure a strong adhesion between the MCPC and the matrix, in addition to the structural interlock. We confirm that the semi-embedded MCPC filament remains attached to the matrix after a semi-embedded sample is stretched, as demonstrated in Supplementary Fig. 14. Zoomed-in views captured the emergence and progression of cracks in the MCPC as the structure is gradually stretched by 150% (Fig. 4B). However, the cracks gradually close and completely disappear after the stretching is fully released. This dynamic process inevitably induces changes in the electrical pathways, as depicted in Fig. 4C, suggesting that the sample has potential applications in stretchable soft electronics with high durability.

A Schematic illustration of the integration of MCPC with Ecoflex elastomer with the zoomed-in view highlighting the molecular interactions between the MCPC filament and the Ecoflex matrix. B Optical images showing the morphology changes to the MCPC filament during one stretching-and-releasing cycle. C Schematic illustration of the change in the conductive pathways in the MCPC filament during stretching. D, E Relative resistance changes of the sample with a fully embedded MCPC filament (D) and a semi-embedded MCPC filament (E) under various strains. F Comparison of gauge factor and stretching strain limit between the fabricated sample and other reported soft strain sensors, including metal-based41,42,43,44, carbon-based45,46,47, conductive polymer-based22,48, hydrogel-based49,50, and putty-like26. G Comparison of strain response range between the fabricated sample and other reported soft strain sensors41,45,47,51,52,53,54,55,56,57,58. H Electrical responses during the first 1000 stretching-and-releasing cycles.

The electrical responses of the structures with a semi-embedded or fully embedded MCPC filament under cyclic stretching are recorded during ten stretching-and-releasing cycles with strains ranging from 0.05% to 150% (Fig. 4D, E). Note that the initial resistance of both structures is approximately 100 Ω. As stretching reaches 0.05%, a slight electrical increase is observed. This response signal remains stable throughout the subsequent stretching-and-releasing cycles. As the stretching ratio further increases, the samples exhibit a consistent rise in electrical resistance though the magnitude of the increase varies between the semi-embedded and fully embedded ones. At a strain level of 150%, the electrical increase is still observable, but the signal becomes unstable during multiple stretching-and-releasing cycles, indicating that the structure is reaching its maximum response range. The sensitivity of the semi-embedded and fully embedded structures is quantitively evaluated using gauge factor: \({GF}=\frac{\Delta R/{{\rm{R}}}_{0}}{{\rm{\varepsilon }}}\), where \(\triangle R\) is the resistance change upon elongation, \({R}_{0}\) is the original resistance, and ε is the applied strain40. For the semi-embedded structure, the gauge factor remains constant at around 50 when the stretching strain is less than 20%. It then shows a slight upward trend from 30% to 100% strain and increases sharply to higher than 15,000 as the elongation rises from 100% to 150% (Supplementary Fig. 15). The gauge factor of the fully embedded structure also exhibits a monotonically increasing trend with a much slower rate as a function of stretching strain until strain reaches beyond 120%. This difference arises from the fact that the semi-embedded filament is only partially attached and prone to crack emergence and progression, making it more sensitive to mechanical stretching. To the best of our knowledge, our MCPC sample exhibits a record-high comprehensive gauge factor (Fig. 4F) and a much broader electrical response range (Fig. 4G) compared to existing soft strain sensors.

Due to the healing capability of our MCPC, the electrical performance of our stretchable strain sensors is highly stable. To assess the initial stability of our sensors, a total of 1000 stretching-and-releasing cycles are performed with a maximum strain of 60% (Fig. 4H). The relative valley resistance changes are negligible over the entire process, confirming the excellent recovery performance of the conductive pathways in the MCPC after each stretching-and-releasing cycle. However, the relative peak resistances of fully embedded and semi-embedded structures appear a slight drop from 40 and 120 to 35 and 80, respectively, during the first 50 cycles, indicating a minor adjustment in the local conductive pathways. After the initial conditioning stage, the relative resistance changes become highly repeatable with only slight fluctuations over the next 950 cycles. These advantages confirm the strong potential of the MCPC sample for use as a strain sensor.

Application of MCPC-based soft sensors

Due to its large strain-sensing range and high repeatability, we further explore the use of the MCPC sample as a skin-mounted human motion detector. The sample is conformally attached to different locations on an adult human body using a commercial tape, and electrical signals are collected in response to various human movements. Figure 5A demonstrates that the sample can detect human facial expressions, including a slight smile, a broad smile, and an angry expression. Due to their distinct levels of muscle movement, these facial expressions can be easily differentiated by the amplitude of the corresponding changes in relative resistance. Figure 5B records the relative resistance responses at the cheek, Adam’s apple, and chest as the tester pronounces the letter ‘A’. Subtle deformations at the corners of the mouth, throat vibrations, and chest resonance are clearly detected. Apart from the aforementioned small deformations, large deformations from many other parts of the body can be captured as well. Figure 5C, D presents the electrical signals in response to periodic finger and elbow movements, showing that the relative resistance changes consistently as the bending angles gradually increase from 0° to 90° and 135°. Additionally, varying squat depths can trigger distinct electrical responses, as shown in Fig. 5E. The sample, attached to the tester’s knee, exhibits good electrical repeatability at the same squat depth, with the resistance returning to its original state once the deformations are reversed. Finally, walking at various speeds is monitored using the fabricated MCPC sample, as shown in Fig. 5F. At the motion’s peak amplitude, the relative resistance change is approximately 6. Despite variations in walking speed, the electrical response remains almost consistent, indicating the sample’s ability to accurately detect movement at different speeds. The real-time resistance changes during natural walking suggest that the sample can be used to count steps based on the response peaks.

A–F Relative resistance variation caused via subtle motion of facial expression (A), deformations at the corners of the mouth, throat vibrations, and chest resonance (B), finger bending with various angles (C), elbow bending with various angles (D), squat with different extents (E), and walking with different velocities (F). G Experimental setup of the remote manipulator control system. H Changes in robotic hand gesture operated remotely using various gestures made by a glove-mounted human hand.

Leveraging the excellent electrical response performance of our sample, we develop a soft electronic smart glove designed to track the motion of each human finger, as displayed in Fig. 5G. The glove integrates the MCPC sample with a commercial circuit board chip, interfacing with a robotic hand. When mounted on a human hand, the glove enables remote operation of the robotic hand through various gestures. The smart glove precisely controls the robotic fingers without requiring additional control algorithms for grasping and releasing (Supplementary Movie 2). We have captured several typical postures in the continuous control process in Fig. 5H. Time-resolved resistance signals and the corresponding robotic responses are presented in Supplementary Fig. 16 and Supplementary Movie 3, illustrating the system’s dynamic behavior during finger movements. This demonstrates the smart glove’s effectiveness for virtual reality applications for tracking the movements of different body parts.

Discussion

In this study, we demonstrated a facile strategy for fabricating stretchable, durable, and highly sensitive soft sensors with customizable designs. We developed a novel MCPC by blending graphite powders with commercial Ecoflex00–10, which exhibited both excellent moldability and conductivity when the graphite content exceeded 30 wt.%. The moldability of our polymer composite resulted from the disruption of the crosslinking reaction of the Ecoflex polymer by graphite at a high content. We further proposed an adaptive 3D printing method to integrate the composite into the elastomer matrix, which effectively overcomes the limitation of embedded 3D printing. The printed sample exhibited superior characteristics as a soft sensor, including a broad strain response range from 0.05% to 150%, highly sensitive electromechanical performance with gauge factors exceeding 15,000, and nearly 100% electrical healing efficiency even after 1000 stretching-and-releasing cycles. Our MCPC shows promise for use in wearable electronics, particularly in healthcare monitoring, rehabilitation, and as a human-machine interface.

Methods

Preparation of moldable conductive polymer composite (MCPC)

The MCPC was created by mixing Ecoflex00–10 silicone (Smooth on, Inc.) with graphite powders (ACS reagent, Sigma-Aldrich) in various weight ratios, unless otherwise stated. Ecoflex00–10 was prepared by mixing its Part A and Part B in a 1:1 weight ratio. More specifically, the MCPC was fabricated through a multi-step dispersion process. Firstly, graphite powders were pre-mixed with Ecoflex Part A. Ecoflex Part B was then added, and the mixture was manually stirred for 10 min. This was followed by high-shear mixing using a planetary centrifugal mixer (THINKY ARE-310) at 2000 rpm for 2 min and subsequently homogenized at 5000 rpm for 10 min to break up any initial agglomerates. Finally, the mixture was degassed under vacuum for 10 min prior to casting or printing. All materials were used as received, without further purification.

Fabrication of soft sensors

The soft sensors were prepared by the proposed adaptive 3D printing. Briefly, the printable MCPC was extruded onto the surface of the liquid Ecoflex00–10 with different crosslinking degrees. A commercial extrusion-based 3D printer (BIO XTM, 3D BioPRINTER, CELLINK) was employed to print the designed model with a tapered nozzle (400 μm in diameter, Nordson). The printing speed and extrusion pressure were systematically varied to investigate their influence on the quality of the printed structures. Driven by gravity, the printed filaments exhibit different sedimentation distances prior to the fully curing of the liquid Ecoflex00–10, leading to various encapsulated structure configurations of the MCPC in the elastomer matrix.

Characterization and measurements

The weight and dimensions of the samples were measured by a scale and Vernier caliper, respectively. Their 2D surface morphology was imaged using a field-emission scanning electron microscope (FE-SEM, Hitachi, SU-70) with 5 kV operating voltage. To minimize charging, the samples were sputtered with gold for 75 s (Denton Vacuum Desk V). Laser scanning confocal microscopy (VK-X1000, KEYENCE) was utilized to characterize the 3D morphology and surface roughness. To identify the functional groups and phases, a Fourier transform infrared spectrometer (FTIR, Nicolet iS50) and an X-ray photoelectron spectroscopy (XPS, SmartLab, Japan) were utilized. For the Nuclear magnetic resonance (NMR) test, 13C NMR measurements were performed using a 600 MHz NMR spectrometer and 3.2 mm probe. 60 kHz hard pulses were used for direct excitation and high-power decoupling scheme (spinal64) was used on proton during detection. A rheometer (MCR 301, Anton Paar) was used to measure viscosity of elastomer inks. Mechanical property of the fabricated samples was characterized on an Instron tensile tester (Instron, 3366). The specimens were mounted to the instrument with a gauge length of 10 mm. The tensile speed was kept at 5 mm/s to obtain a stable mechanical response. A four-point probe system (Ossila, UK) was employed to measure the sheet resistance of the different filament samples at rest. The resistance during the dynamic deformation processes was recorded by a digital multimeter (KEYSIGHT, 34465 A, 6 1/2), and two thin copper wires connected the sensor to the multimeter. Note that the cyclic stretching was carried out on a home-made stretcher controlled by a computer, at a speed of 0.5 mm/s. The experiments of human motion detection were performed with a healthy adult. A written consent was obtained from the participant regarding the research experiments and publication. The commercial robotic hand (Ti5 robot, China), which has six degrees of freedom (DoF), was used to demonstrate the ability to control the robot using the sample. With flexible sensors mounted on the tester’s fingers, the resistance of these samples was measured by a customized sampling board to predict finger bending angles. The predicted angles were then used to control the robot hand’s gestures through a MATLAB program.

COMSOL simulation

COMSOL analyses were conducted to simulate the sedimentation process of printed filament in Ecoflex solution. The system was modeled as a 2D problem in which a filament with a round profile descended in liquids with different viscosities, with the density and dimensions of the filament matching those of the experimental sample. The temporal evolution of liquid viscosity was obtained based on previous experimental results39. Additionally, we simulated the filament’s behavior in the horizontal plane. By applying a stretching or compression load of 0.001 N/m² to the end of an L-shaped object, we observed its drag behavior in Ecoflex liquids with varying viscosities over specific time intervals.

Data availability

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon request.

References

Park, H. et al. Organic flexible electronics with closed-loop recycling for sustainable wearable technology. Nat. Electron. 7, 39–50 (2024).

Tao, D. et al. Electro-spun nanofibers-based triboelectric nanogenerators in wearable electronics: status and perspectives. npj Flex. Electron. 9, 4 (2025).

Wang, W. et al. Neuromorphic sensorimotor loop embodied by monolithically integrated, low-voltage, soft e-skin. Science 380, 735–742 (2023).

Jung, Y. H. et al. A wireless haptic interface for programmable patterns of touch across large areas of the skin. Nat. Electron. 5, 374–385 (2022).

Lee, J. et al. Analytic modeling and validation of strain in textile-based OLEDs for advanced textile display technologies. npj Flex. Electron. 8, 73 (2024).

Su, R., Park, S. H., Ouyang, X., Ahn, S. I. & McAlpine, M. C. 3D-printed flexible organic light-emitting diode displays. Sci. Adv. 8, eabl8798 (2022).

Freitas, M. C., Sanati, A. L., Lopes, P. A., Silva, A. F. & Tavakoli, M. 3D printed gallium battery with outstanding energy storage: toward fully printed battery-on-the-board soft electronics. Small 20, 2304716 (2024).

Zhao, J. et al. Self-powered, long-durable, and highly selective oil–solid triboelectric nanogenerator for energy harvesting and intelligent monitoring. Nano-Micro Lett. 14, 160 (2022).

Wu, S., Peng, S., Yu, Y. & Wang, C.-H. Strategies for designing stretchable strain sensors and conductors. Adv. Mater. Technol. 5, 1900908 (2020).

Zhang, S. et al. On-skin ultrathin and stretchable multifunctional sensor for smart healthcare wearables. npj Flex. Electron. 6, 11 (2022).

Yang, Y., Duan, S. & Zhao, H. Advances in constructing silver nanowire-based conductive pathways for flexible and stretchable electronics. Nanoscale 14, 11484–11511 (2022).

Yang, Y., Duan, S., Xiao, W. & Zhao, H. Silver nanowire-based stretchable strain sensors with hierarchical wrinkled structures. Sens. Actuators A Phys. 343, 113653 (2022).

Sappati, K. K., Rout, B., Girard-Lauriault, P.-L. & Bhadra, S. Plasma treatment of composite piezoelectric thin films for good adhesion of printed conductive ink. ACS Appl. Polym. Mater. 3, 319–328 (2021).

Huang, Z. & Lin, Y. Transfer printing technologies for soft electronics. Nanoscale 14, 16749–16760 (2022).

Yang, Y., Duan, S. & Zhao, H. Highly conductive silicone elastomers via environment-friendly swelling and in situ synthesis of silver nanoparticles. Adv. Mater. Interfaces 8, 2100137 (2021).

Zhou, J. et al. Multiscale and hierarchical wrinkle enhanced graphene/Ecoflex sensors integrated with human-machine interfaces and cloud-platform. npj Flex. Electron. 6, 55 (2022).

Qi, D., Zhang, K., Tian, G., Jiang, B. & Huang, Y. Stretchable electronics based on PDMS Substrates. Adv. Mater. 33, 2003155 (2021).

Chu, Z. et al. Superhydrophobic gradient wrinkle strain sensor with ultra-high sensitivity and broad strain range for motion monitoring. J. Mater. Chem. A 9, 9634–9643 (2021).

Tang, C. et al. Ultrasensitive textile strain sensors redefine wearable silent speech interfaces with high machine learning efficiency. npj Flex. Electron. 8, 27 (2024).

Nezakati, T., Seifalian, A., Tan, A. & Seifalian, A. M. Conductive polymers: opportunities and challenges in biomedical applications. Chem. Rev. 118, 6766–6843 (2018).

Tang, H. et al. A solution-processed n-type conducting polymer with ultrahigh conductivity. Nature 611, 271–277 (2022).

Jiang, X. et al. Flexible conductive polymer composite materials based on strutted graphene foam. Compos. Commun. 25, 100757 (2021).

Kim, N. et al. Elastic conducting polymer composites in thermoelectric modules. Nat. Commun. 11, 1424 (2020).

Fang, R. et al. 3D highly stretchable liquid metal/elastomer composites with strain-enhanced conductivity. Adv. Funct. Mater. 34, 2310225 (2024).

Zou, Z. et al. Rehealable, fully recyclable, and malleable electronic skin enabled by dynamic covalent thermoset nanocomposite. Sci. Adv. 4, eaaq0508 (2018).

Boland, C. S. et al. Sensitive electromechanical sensors using viscoelastic graphene-polymer nanocomposites. Science 354, 1257–1260 (2016).

D’Elia, E., Barg, S., Ni, N., Rocha, V. G. & Saiz, E. Self-healing graphene-based composites with sensing capabilities. Adv. Mater. 27, 4788–4794 (2015).

Li, Z. et al. 3D-printable and multifunctional conductive nanocomposite with tunable mechanics inspired by sesame candy. Nano Energy 108, 108166 (2023).

Muth, J. T. et al. Embedded 3D printing of strain sensors within highly stretchable elastomers. Adv. Mater. 26, 6307–6312 (2014).

Wu, Q. et al. Suspension printing of liquid metal in yield-stress fluid for resilient 3D constructs with electromagnetic functions. npj Flex. Electron. 6, 50 (2022).

Wakabayashi, K. et al. Polymer−graphite nanocomposites: effective dispersion and major property enhancement via solid-state shear pulverization. Macromolecules 41, 1905–1908 (2008).

Yap T. F. et al. Thermally accelerated curing of platinum-catalyzed elastomers. Cell Rep. Phys. Sci. 5, 101849 (2024).

Chira, N. A., Nicolescu, A., Stan, R. & Rosca, S. Fatty acid composition of vegetable oils determined from 13C-NMR spectra. Rev. Roum. Chim. 67, 1257–1263 (2016).

Nimerovsky, E. et al. Proton detected solid-state NMR of membrane proteins at 28 Tesla (1.2GHz) and 100kHz magic-angle spinning. Biomolecules 11, 752 (2021).

Xue, K., Sarkar, R., Tošner, Z. & Reif, B. Field and magic angle spinning frequency dependence of proton resonances in rotating solids. Prog. Nucl. Magn. Reson. Spectrosc. 130-131, 47–61 (2022).

Jin, M. Y. et al. Engineered non-covalent π interactions as key elements for chiral recognition. Nat. Commun. 13, 3276 (2022).

Chen, W. et al. On the nature of Pt-carbon interactions for enhanced hydrogen generation. J. Catal. 389, 492–501 (2020).

Wang, S. & Urban, M. W. Self-healing polymers. Nat. Rev. Mater. 5, 562–583 (2020).

Yang, Y., Cao, B., Tang, Y. & Huang, C. One-pot fabrication of bio-inspired shape-morphing bilayer structures. J. Chem. Eng. 500, 156735 (2024).

Lee S., et al. Shape-reconfigurable crack-based strain sensor with ultrahigh and tunable sensitivity. Adv. Funct. Mater. 35, 2421812 (2025).

Oh, J. Y. et al. Stretchable self-healable semiconducting polymer film for active-matrix strain-sensing array. Sci. Adv. 5, eaav3097 (2019).

Wang, Y. et al. A durable nanomesh on-skin strain gauge for natural skin motion monitoring with minimum mechanical constraints. Sci. Adv. 6, eabb7043 (2020).

Zhang, Y. et al. A flexible strain sensor based on conductive TPU/CNTs-Gr composites. J. Appl. Polym. Sci. 139, e52475 (2022).

Tang, N. et al. A highly aligned nanowire-based strain sensor for ultrasensitive monitoring of subtle human motion. Small 16, 2001363 (2020).

Yang, H. et al. Computational design of ultra-robust strain sensors for soft robot perception and autonomy. Nat. Commun. 15, 1636 (2024).

Kumaresan, Y., Mishra, S., Ozioko, O., Chirila, R. & Dahiya, R. Ultra-high gauge factor strain sensor with wide-range stretchability. Adv. Intell. Syst. 4, 2200043 (2022).

Lee, J. H. et al. Heterogeneous structure omnidirectional strain sensor arrays with cognitively learned neural networks. Adv. Mater. 35, 2208184 (2023).

Bhattacharjee, M., Soni, M., Escobedo, P. & Dahiya, R. PEDOT: PSS microchannel-based highly sensitive stretchable strain sensor. Adv. Electron. Mater. 6, 2000445 (2020).

Zhang, Y.-Z. et al. MXenes stretch hydrogel sensor performance to new limits. Sci. Adv. 4, eaat0098 (2018).

Zhao, W. et al. Road narrow-inspired strain concentration to wide-range-tunable gauge factor of ionic hydrogel strain sensor. Adv. Sci. 10, 2303338 (2023).

Shen, Z. et al. High-stretchability, ultralow-hysteresis conductingpolymer hydrogel strain sensors for soft machines. Adv. Mater. 34, 2203650 (2022).

Zhou, Z. et al. Sign-to-speech translation using machine-learning-assisted stretchable sensor arrays. Nat. Electron. 3, 571–578 (2020).

Lu, Y. et al. Stretchable graphene–hydrogel interfaces for wearable and implantable bioelectronics. Nat. Electron. 7, 51–65 (2024).

Seo, K. et al. Superhydrophobic and highly elastic strain-sensing fiber embedded with carbon nanotubes and aerogels based on the dipping and drying method. Adv. Mater. Interfaces 11, 2300820 (2024).

Lee, J. et al. Transparent, flexible strain sensor based on a solution-processed carbon nanotube network. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 9, 26279–26285 (2017).

Zhu, J. et al. Tuning strain sensor performance via programmed thin-film crack evolution. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 13, 38105–38113 (2021).

Zou, J., Chen, X., Song, B. & Cui, Y. Bionic spider web flexible strain sensor based on CF-L and machine learning. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 16, 23761–23770 (2024).

Yu, T., Lü, X. & Bao, W. High electrical self-healing flexible strain sensor based on MWCNT- polydimethylsiloxane elastomer with high gauge factor and wide measurement range. Compos. Sci. Technol. 238, 110049 (2023).

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank Haoyu Jiang for his help on the mechanical test. C.H. acknowledges financial support from Ministry of Education (MOE), Singapore, under its Academic Research Fund Tier 1 (RG74/23 and RG84/25) and Academic Research Fund Tier 2 (MOET2EP50121-0004).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Y.Y.: Conceptualization, Methodology, Software, Data curation, Formal analysis, Writing–original draft. Y.T.: Simulation, Methodology. K.X.: Methodology, Data curation. J.L.: Methodology, Construction of test platform. S.D.: Conceptualization, Validation writing–review. C.H.: Conceptualization, Formal analysis, Supervision, Validation writing–review and editing, Funding acquisition.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

A Singapore provisional patent (application number: 10202502020W) was filed by Y.Y., Y.T. and C.H.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Yang, Y., Tang, Y., Xue, K. et al. Adaptive 3D printing of moldable conductive polymer composite for highly sensitive soft sensors with a broad working range. npj Flex Electron 10, 22 (2026). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41528-025-00523-3

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41528-025-00523-3