Abstract

The growth kinetics of localized corrosion, e.g. pits, in corrosive environments often controls the service life of metallic components. Yet, our understanding of these kinetics is largely based on coupon-level, e.g. mass-loss, studies which provide limited insights into the evolution of individual damage events. It is critical to relate observed cumulative loss trends, such as links between changing humidity and mass loss rates, to the growth kinetics of individual pits. Towards this goal, we leverage in-situ X-ray computed tomography to measure the growth rates of over sixty pits in aluminum in four different humid, chloride environments over ≈3 days of exposure. Pit growth rates and final volumes increased with increasing droplet volume, which was observed to increase with increasing humidity and salt loading. Two factors, droplet spreading and oxide jacking, dramatically increased pit growth rates and final volumes.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

The rate of localized corrosion in the form of pits frequently controls part lifetimes in humid, chloride environments. In these conditions, failure is often caused by one or a few instances of damage, e.g. when a pit exceeds a critical size. The rate at which individual pits grow as a function of material and environment is thus an important factor when assessing part lifetime1,2,3,4,5. However, predicting local damage rates during atmospheric corrosion requires extrapolation from continuum scale measurements, a challenging task. Classically, atmospheric corrosion rates are evaluated using mass change measurements, but these give no information about the growth kinetics of individual pits6,7,8. Measurements from aqueous corrosion may provide insights into electrochemical processes, but it is challenging to relate these data to the highly localized attack typical of pits3. X-ray computed tomography (XCT) recently emerged as an alternative method to directly measure rates of localized corrosion in-situ4,9,10,11,12,13,14,15,16,17,18,19,20. XCT allows attack to be characterized at a spatial and temporal scale relevant to long term atmospheric corrosion processes without significantly disturbing the evolving process9. This study leverages this technique to examine how two environmental factors, salt loading and relative humidity (RH), affect pit growth kinetics in commercial-purity aluminum during atmospheric corrosion.

Both field and laboratory studies indicate that atmospheric corrosion rates, as measured using mass change, generally increase with increasing salt loading6,7,21,22,23. For commercial-purity aluminum, Schaller et al. and Blucher et al. both observed that the corrosion rate of NaCl-loaded samples increased with increasing salt loading6,24. Salts create electrolyte on the surface of materials by water uptake from the air; salt loading thus significantly influences the available cathode surface area. With increasing salt load, electrolyte coverage and volume generally increase, tending towards thin, continuous films6,25. The increase in droplet size typically observed with increasing salt loading can also intensify the impact of differential aeration7,26,27,28

RH also greatly influences corrosion kinetics29. Depending on the material and salt, a critical RH must be reached before an electrolyte film forms. Above this critical value, RH, together with salt loading, dictates the composition, volume, and many other properties of the electrolyte7,30,31. While it is challenging to draw direct relationships between RH and atmospheric corrosion rates, a few general trends have been observed. Studies of marine environments found that the corrosion rate of zinc increases with increasing water layer thickness; this, in turn, increases with increasing RH32. Above some critical thickness value, though, the corrosion rate is limited due to oxygen diffusion through the water layer33. For plain carbon steel, general trends of increasing pit depth and corrosion rate with increasing RH were observed both for samples loaded with NaCl and artificial sea water22,34. These results can be rationalized by considering that the droplet size, which strongly influences the cathode area, increases with increasing RH. The authors are unaware of data regarding the effect of RH on atmospheric corrosion rates in commercial-purity aluminum when salt loading is held constant.

Both synchrotron and laboratory-based XCT techniques have been applied to many aspects of corrosion, ranging from the growth rates of environmentally assisted cracks to the evolution of galvanic corrosion2,3,4,5,9,10,11,12,13,14,16,17,18,35,36,37,38. While the ≈1 μm spatial resolution of this technique prevents some aspects of corrosion from being captured, e.g. pit tunneling and submicron crack growth, it has provided valuable insights into the rates at which localized damage progresses, e.g. pit growth rates4,10,12. Several studies measured pit growth kinetics in aluminum and iron alloys under potentiostatic control or while immersed in chloride solutions19,35,39. Because damage evolution is significantly different under atmospheric conditions than immersed conditions, others characterized the growth rates of pits and environmentally-assisted cracks during atmospheric corrosion4,10,12. An important conclusion of these studies is that corrosion rates obtained from mass change data are often vastly different from the local corrosion rates measured using XCT4,10.

Prior XCT-based studies of pit growth kinetics in Al during atmospheric corrosion produced several key findings. Pits in high-purity (99.99%) Al loaded with 200 μg cm−2 of NaCl exposed at 84% RH generally exhibited sigmoidal growth kinetics40, i.e. having an initial exponential phase, an intermediate phase which was approximately linear, and a final phase during which the pit volume approached an asymptote until all pit growth ceased. The rates of growth of the 11 pits observed varied between 50 and 825 μm3 hr−140. Similarly, for commercial-purity Al samples exposed at 84% RH and loaded with 60 μg cm−2 of NaCl, the rates of pit growth across the 9 pits observed varied by more than two orders of magnitude, from 30 to 3930 μm3 hr−1. Notably the temporal resolution of the latter study was too slow to capture the sigmoidal growth kinetics of most pits10. In both studies, it was observed that the rate of pit growth increased abruptly when the droplet associated with the pit spread by forming one or more secondary droplets. In commercial-purity Al, the fastest rates of pit growth occurred after droplet spreading10.

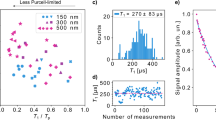

The present study examines the influence of two environmental factors, RH and salt loading, on pit growth rates in commercial-purity Al (1100 Al). Based on our understanding of pit growth rates from prior studies, the present study addresses two questions: 1) how does the distribution of pit growth rates change as a function of either salt loading or RH? 2) for a given environment, what factors produce the fastest pit growth rates? XCT was used to characterize the morphology and growth kinetics of pits in 1100 Al wires loaded with either 60 or 200 μg cm−2 of NaCl and exposed at either 84% or 98% RH over the first 60 to 90 h after exposure. We use the abbreviations 84RH-060, 84RH-200, 98RH-060, and 98RH-200 to distinguish between these four conditions. The material and environments were chosen both for their close relationship to previous work by the authors6,10,40 and their pedagogical simplicity. This study has the same minimum resolvable feature size and temporal resolution, 15.6 μm3 and 1.33 h., as used in ref. 40, see Methods for more information.

Results

Droplet coverage

The total area covered by droplets increased as a function of both salt loading and RH, see Fig. 1a. Figure 1b shows that increasing RH, regardless of salt loading, increased droplet volumes. Representative 3D renderings showing top-down views of droplets (dark gray) on the surface of Al wires (light gray) in each of these environments are provided in Fig. 1c–f. In addition to droplets, thin layers of electrolyte between the droplets were likely present on the surface of wires, though these could not be observed using XCT30. For a given RH, the distribution of individual droplet volumes remained relatively constant at the two salt loadings examined, but the number density of droplets increased with increasing salt loading.

The fraction area covered by droplets on the surface of each of these samples is shown in (a). The distribution of individual droplet volumes on the surface of samples exposed to four different environments is shown in (b). Representative 3D renderings collected 10 h after exposure showing the distribution of droplets on the surface of these samples are provided in (c–f), all images are at the same scale. The Al wire is colored light gray. The drops appear as dark gray on the surface of the wires. CDF in this figure and all others is an abbreviation of cumulative distribution function.

Cumulative pitting characteristics

Prior studies characterizing pit growth rates in Al indicate that, for a given material and environment, ~10 pits provide a sufficient sample size to investigate statistical variations in pit growth rates10,40. The total number of pits observed across all samples exposed at each environment are summarized in Table 1. In total, across all four environments, the growth kinetics of 63 pits were characterized, with a minimum of 12 pits observed in each environment. At 84RH, it was necessary to characterize 3 and 2 replicate samples at salt loadings of 60 and 200 μg cm−2, respectively, to observe a total of at least ten pits that exceeded the minimum resolvable feature size, 15.6 μm3. For each salt loading exposed at 98RH, a single sample was sufficient to observe at least ten pits. Given the time-consuming nature of testing and data analysis, in-depth study of specimen-to-specimen variability in the rate of pit nucleation for a given environment was outside the scope of the present investigation.

Across all samples, only a small percentage of drops were associated with pits, see Table 1. In all but two cases, pits nucleated and grew under separate droplets relative to other pits on that sample. Additionally, simultaneous nucleation and growth of multiple pits under widely separated drops was observed for all tested environments. The percentage of droplets from which pits nucleated increased with increasing RH but was not a strong function of salt loading; given sample-to-sample variability in pit nucleation, more replicates are necessary to confirm this observation.

The rate of pit nucleation per unit wetted area increased as a function of RH but was not a strong function of salt loading, see Fig. 2a. Except samples exposed at 84RH-060, all samples exhibited similar rates of volume loss per unit wetted area over the first 60 h after exposure, see Fig. 2b. The volume loss for samples exposed at 84RH-060 was an order of magnitude smaller than for all other environments of interest.

Plots of (a) the cumulative number of pits per unit wetted area and (b) the cumulative volume loss per unit wetted area as a function of time for the first 90 h after exposure are shown for all four environments. As discussed in the methods, machine errors caused two samples exposed at 84% RH to terminate 73 and 64 h after exposure, truncating these experiments prematurely.

The evolution of individual pits

Plots of pit volume as a function of time for two pits are provided in Fig. 3. The absolute error in pit volume measurement was between 1 and 5% of the total pit volume, see refs. 10,40 for more details. Nonphysical decreases in pit volume, e.g. Figure 3b, are within this measurement error, see representative error bars in Figs. 3, 4.

Plots of pit volume as a function of time elapsed after nucleation are provided for two typical pits in (a) and (b). Insets show tomographs of these pits. 3D renderings and 2D tomographs of the pit shown in (a) at the points highlighted with yellow are provided in (c–h) and (i–k), respectively. In (c–h) the droplet is colored blue, the surface of the wire is colored gray, yellow indicates new growth relative to the previous time step and black represents growth at the prior time step. (g) shows a top-down view of the pit. (h) and (i) show cross-sections of the pit along the axes shown in (g). Error bars represent absolute error in pit volume measurement.

Plots of pit volume as a function of time elapsed after nucleation are provided for two pits that exhibited piecewise sigmoidal growth kinetics in (a, b). Dashed lines separate the initial and secondary growth regimes. 3D renderings of the pit shown in (a) at the six timesteps highlighted red are provided in (c–h). The droplet and wire surface are colored gray. Yellow indicates new growth relative to the previous time step while black represents growth at the prior time step. The arrow at (d) highlights the beginning of droplet spreading. (i–k) show 2D slices of this pit at 8 timesteps. (i) shows a top-down view of the droplet above the pit while (j) and (k) show cross-sections of the pit along the axes shown in (i). Arrows indicate droplet spreading at 3.9 and 6.5 h. after this pit nucleated and oxide jacking at 18.2 and 24.7 h. after this pit nucleated. Representative error bars indicate absolute error in pit volume measurement.

The sigmoidal growth kinetics exhibited by the pits in Fig. 3 were typical of 51 of the 63 pits observed in this study. As observed in ref. 40, the limited temporal resolution of this study prevented clear differentiation between the exponential, linear, and asymptotic periods of pit growth. The separations in Fig. 3a are suggestions for when these periods occurred, not definitive delineations.

To illustrate the morphological evolution typical of the 51 pits that exhibited sigmoidal growth kinetics, 3D renderings and 2D slices of the pit shown in Fig. 3a at 6 timesteps after nucleation are provided in Fig. 3c–k. As observed in prior studies of pitting in Al, pits across all environments exhibited an arborescent-like morphology, with meandering branches or tendrils propagating into the Al material40. These tendrils were occasionally difficult to discern using 3D data. For instance, it is likely that the two volumes observed in Fig. 3d are physically connected; however, it was not until 7.8 h after this pit nucleated that the tendril joining these volumes became large enough to be resolved using XCT, see Fig. 3g. Additionally, as observed in prior studies of pit growth in Al10,40, only a portion of the pit grew between any given timesteps, e.g. compare Fig. 3g, h.

For the remaining 12 pits observed in this study, the growth kinetics were piecewise, with strong similarities to sigmoidal kinetics. Examples are provided in Fig. 4. For these pits, after reaching an initial asymptote, pit volume increased nonlinearly for hours until a second asymptote was reached. For some pits, such as that shown in Fig. 4a, this process was repeated multiple times until the pit reached its final volume. The morphology of these 12 pits both before and after reaching this asymptote evolved in a manner similar to the other 51 pits.

For the 12 pits that exhibited piecewise growth kinetics, we define initial and secondary growth regimes as the regimes before and after the initial asymptote was reached, see labels in Fig. 4. In all 12 cases, the initial growth regime exhibited sigmoidal growth kinetics. The kinetics of the secondary growth regime varied pit to pit. In some cases, e.g. Figure 4b, sigmoidal growth kinetics were observed. In others, e.g. Figure 4a, piecewise linear growth kinetics were observed. In the latter case, it is possible that the temporal resolution of this study was insufficient to resolve sigmoidal growth kinetics.

The transition from initial to secondary growth regimes was associated with one of two distinct events: droplet spreading or oxide-jacking. These are illustrated in Figs. 4,5. For clarity, the terms droplet spreading and oxide jacking are now defined.

(a–c) show 2D slices of a pit that exhibited oxide jacking at four timesteps. (c) shows top-down views of the droplet associated with this pit. Arrows highlight the oxide jacking that began 14.3 h. after his pit nucleated. A plot of pit volume as a function of time after pit nucleation for this pit is provided in (d). The inset in (d) highlights a small area of the boxed region in (b) 14.3 h after this pit nucleated. The 2D slices in (a–c) come from the timesteps highlighted in the plot in (d).

Droplet spreading by the formation of secondary droplets is known to occur around NaCl or MgCl2 drops associated with growing pits in aluminum and other alloys41,42,43,44. It can be caused by 1) the creation by oxygen reduction and/or hydrogen reduction of OH- ions near the edge of droplets (cathodic spreading), or 2) the production of metal ions by corrosion migrating from within the pit into the droplet (anodic spreading). In either case and under equilibrium conditions, added ionic species, e.g. OH-, near the edge of the electrolyte can cause water to be absorbed into the electrolyte. This leads to growth and spreading of the electrolyte41,43.

An example of droplet spreading is shown in Fig. 4a. A small secondary droplet formed at the edge of the main droplet approximately 6.5 h. after this pit nucleated. This droplet grew and spread in subsequent timesteps. Shortly after this droplet formed, all measurable growth of this pit ceased for approximately 1.3 h. Pit growth subsequently resumed at a rate faster than that measured prior to the formation of a secondary droplet. In total, seven pits exhibited droplet spreading. In each case, within the temporal resolution of this study, the growth kinetics of these pits after droplet spreading were piecewise linear. The number of pits associated with droplet spreading are summarized in Table 1. All cases of droplet spreading occurred at 84 RH.

Oxide jacking is defined as follows. Oxidation of many metals, including Al, is generally accompanied by a net increase in material volume45,46. When this occurs within a confined space, e.g. an occluded pit, the stresses generated by the net expansion of material can be sufficient to fracture or deform the surrounding material. This results in the phenomena known as oxide jacking. Commonly associated with cracking of steel-reinforced concrete47, oxide jacking has been observed in many metals during corrosion, including Al48.

In the current study, oxide jacking was associated with five pits, e.g. see red arrows at 18.2 and 24.7 h in Fig. 4g–k. To better elucidate this phenomenon, a second pit associated with oxide jacking is shown in Fig. 5. As illustrated in Fig. 5d, all measurable growth of this pit ceased 7.8 h. after it nucleated. Subsequently, between 13 and 14.3 h after this pit nucleated, three simultaneous (within the temporal resolution of this study) events occurred. First, uncorroded metal around the pit mouth was forced away from the surface of the wire, see red arrows in Fig. 5. Second, cracks appeared in the corrosion product, as illustrated in Fig. 5d. Third, measurable pit growth resumed, both near the pit mouth and near the bottom of the pit, e.g. see region boxed red in Fig. 5a. Over subsequent timesteps, uncorroded metal around the pit mouth was forced further away from the surface of the wire. Pit growth into the wire’s interior continued, see regions highlighted by green and blue boxes in Fig. 5. Eventually, the rate of pit growth slowed, and pit volume reached a new asymptote. For the pit shown in Fig. 5, this process subsequently restarted, producing an additional secondary growth rate. The number of pits associated with this phenomenon at each environment are summarized in Table 1. One pit, that shown in Fig. 4a, was associated with droplet spreading and oxide jacking, in that order.

The growth kinetics of individual pits

For all pits observed in this study, both those with and those without a secondary growth regime, the initial pit growth rate is defined as the slope of the approximately linear region within the initial growth regime. This linear region is labelled in Fig. 3b and Fig. 4a, b. This approach follows methods described elsewhere for evaluating the growth rate of sigmoidal functions49,50 and allows pit growth rates reported in this study to be compared to those provided in prior studies10,40. Secondary pit growth rates are defined as the slopes of the linear region(s) within the secondary growth regime, see Fig. 4. For some pits exhibiting piecewise growth kinetics, e.g., the pit shown in Fig. 4a, multiple secondary growth rates were recorded. Note that pit morphology during both the initial and secondary growth regimes evolved in similar manners. Figure 6a highlights three key results of this study. First, for each environment, the initial pit growth rates varied by more than an order of magnitude. Second, the initial pit growth rates observed at 84RH-200, 98RH-060, and 98RH-200 were remarkably similar. Finally, the initial growth rates of pits were significantly slower at 84RH-060 than at any of the other environments. These results are also highlighted in Supplementary Table 1, which provides the minimum, maximum, average, median, standard deviation, and skewness of initial pit growth rates for all four environments.

For the four environments examined in this study, distributions of (a) initial and (b) secondary pit growth rates are provided. Some pits exhibited multiple secondary growth rates – all of these are included in (b). (c) shows a plot of secondary growth rate as a function of initial growth rate; connected points highlight secondary growth rates that were associated with a single pit. Contour lines are provided in (c) as a visual guide to compare initial and secondary growth rates.

Figure 6b shows two trends regarding secondary growth rates. First, at all environments, secondary growth rates were generally significantly faster than initial pit growth rates, see also Fig. 6c. Second, the rate of secondary growth increased with increasing RH but was not a strong function of salt loading. As highlighted in Table 1, droplet spreading only occurred at 84RH, while oxide jacking primarily occurred at 98RH.

A similar trend to that observed in the distribution of initial pit growth rates was observed in the distribution of final pit volumes, see Fig. 7b. The duration of pit growth was a weak function of RH, see Fig. 7a, with the longest growing pits observed in the conditions of lowest RH. Salt loading had no clear effect on the duration of pit growth.

The droplet size associated with pit nucleation increased with increasing RH, see Fig. 8a. At 84RH, the droplet size associated with pit nucleation increased with salt loading, but this was not observed at 98 RH. These data suggest that, for the conditions in this study, a minimum droplet size of 10−3 nL was necessary to nucleate a pit larger than the minimum resolvable feature size, 15.6 μm3.

As Fig. 8b, c show, the initial pit growth rate and final pit volume varied significantly for a given droplet volume. For a given droplet volume, these data also indicate that an upper limit existed for the initial pit growth rate and the final pit volume. This relationship was nonlinear, with a significant increase in the maximum pit volume and initial pit growth rate when droplet size exceeded 0.1 nL.

Discussion

Predicting the distribution of pit sizes as a function of environment and time remains a key challenge within the field of atmospheric corrosion. This is a function of both the rate and duration of pit growth – this study focuses on the factors that affect the growth rate of pits. In the present study, pits at all environmental conditions generally exhibited similar growth kinetics, i.e. sigmoidal, and similar morphologies, i.e. arborescent-like. It is thus reasonable to compare pit growth rates across these environments.

To understand the effects of RH and salt loading on pit growth rates, we must first consider the effect of droplet size on pit growth rate. The upper limits in Fig. 8b, c indicate that initial pit growth rates and final pit volumes were strongly influenced by droplet volume. These upper limits can be explained by cathodic limitations: increasing the droplet size increases the total possible cathodic area, increasing the total cathodic capacity and maximizing initial pit growth rates and pit volume. This suggests that the fastest growing pits for a given droplet volume grew under cathodic control. Cathodic limitations on growth rate have also been shown in mass-loss measurements in Al systems6.

Consider now the effect of RH and salt loading on droplet volumes. Figure 1 shows that the median droplet volume increased by an order of magnitude with increasing RH but was not significantly influenced by salt loading. This explains many observations from this study, e.g. the similarities in pit growth rates at 98RH and the significant differences in growth rates between 98RH-060 and 84RH-060 but does not explain the difference between growth rates at 84RH-200 and 84RH-060. Regarding the latter observation, Fig. 8a provides a key insight: the distribution of droplet volumes beneath which pits nucleated at 84RH-200 was significantly larger than at 84RH-060. Notably, for a given droplet volume, initial pit growth rates at 84RH-060 were similar to those observed for all other environmental conditions. However, the median droplet volume beneath which pits nucleated at 84RH-060 was nearly an order of magnitude smaller than the median droplet volumes beneath which pits nucleated at other environments. Thus, the significant differences in pit growth rates and final pit volumes between 84RH-060 and all other conditions can be, at least partly, attributed to the distribution of droplets beneath which pits nucleated for these environments.

We note that changing RH and salt loading also alter the electrochemical processes associated with pitting, e.g. oxygen solubility and diffusivity. As described in the Supplementary Discussion, electrochemical calculations suggest that the total cathodic capacity available for dissolution increases with increasing RH and salt loading. We speculate that these effects were muted by the significant changes in droplet size caused by changes to RH and salt loading as discussed in the previous paragraphs.

Figure 8 also shows that a wide range of pit growth rates occurred for a given droplet size, even for a single environment. Pitting is a stochastic process and factors other than droplet size affect the final pit volume and initial growth rates of pits. A prior study of pit growth in a 99.99% (4 N) Al material, which contained relatively few, widely-spaced Fe-rich particles, indicated that pit growth rates are affected by the local grain and dislocation structure40. In the present study, the distribution, size, and morphology of Fe-rich intermetallics also likely influenced pit growth rates. These intermetallics are known to serve as local preferential cathodes and likely locally accelerate pit growth51. The limited temporal resolution of this study prevented characterization of the local rates of corrosion near Fe-rich intermetallics, but their effects can be assessed indirectly as described in the following.

Consider the difference in pit growth rates at 84RH-200 between this material and the 4N-Al material used by ref. 40, see Fig. 9. Note that the 4N-Al material had a significantly lower volume-density of Fe-rich intermetallics than the material used in this study. Figure 9 suggests that, for a given droplet volume, the presence of Fe-rich particles in the 1100 Al material significantly accelerated pit growth rates. We speculate that the variations in pit growth rates for a given droplet volume observed in this study can be partially attributed to local variations in the density, size, and morphology of second-phase particles, though grain boundaries and local dislocation density likely also played a role52.

Using data from ref. 40 (a) a CDF showing pit growth rates and (b) plots of pit growth rate as a function of droplet volume are provided for 1100-Al and 99.99% (4 N) Al for conditions of 84RH and 200 μg cm−2 loading with NaCl. Data in ref. 40 were collected using the same temporal and spatial resolution as that used in this study.

The fastest rates of pit growth observed in this study occurred after droplet spreading or oxide jacking. We first consider the effects of droplet spreading on pit growth kinetics. Prior in-situ XCT studies of pit growth in Al demonstrated that, by altering cathode size and efficiency, droplet spreading tends to increase the rate of pit growth10,40. As Fig. 6c shows, the rate of pit growth increased by 50% or more following droplet spreading. Additionally, as shown in Fig. 7a, the longest durations of pit growth were associated with droplet spreading. This is also attributed to the increased size and efficiency of the cathode after droplet spreading10,40. These observations indicate the crucial role that droplet spreading plays in dictating the maximum pit size. Indeed, all of the largest pits observed at 84RH-060 and two of the largest pits observed at 84RH-200 were associated with droplet spreading. It is thus relevant to consider the conditions which produce droplet spreading during pitting of Al.

In the present study, droplet spreading was only observed at 84RH and was associated with ≈25% of the pits. As discussed by refs. 41,42,43,44, droplet spreading can only occur when sufficient ions diffuse into the droplet such that a significant change in droplet chemistry results. By this reasoning, the likelihood of droplet spreading is influenced by initial droplet size, the concentration of NaCl within the droplet, and the rate of ion production, the latter being directly linked to pit growth rate. Figure 8a suggests that, at 84RH, for a given droplet size, a minimum initial pit growth rate is necessary, but not sufficient, for droplet spreading to occur in Al. Because of the significant decrease in NaCl concentration with increasing RH from 84 to 98RH, we speculate that significantly higher rates of pit growth than those observed in this study would have been necessary for droplet spreading to occur at 98RH.

The fastest rates of pit growth observed at any environment were associated with the occurrence of oxide-jacking. Based on the limited temporal resolution of XCT experiments, we hypothesize that oxide-jacking was produced by the following sequence of events. First, the rate of pit growth gradually slowed due to the formation of corrosion product within the pit increasing ohmic drop and reacting with the electrolyte to form some combination of aluminum oxides, hydroxides and hydroxycarbonates, such as dawsonite (NaAlCO3(OH)2) 6,40. Precipitation of the latter has been shown to dry out NaCl electrolytes during corrosion of aluminum under conditions similar to this present study6, though it could not be clearly differentiated from the electrolyte using XCT. The pressure created by the expanding corrosion product or other debris within the pit eventually exceeded the local strength of the Al surrounding the pit mouth, causing a portion of the Al to rupture. The corrosion product precipitated in the electrolyte subsequently fractured, potentially by the force of the uplifted Al. These two events, which likely occurred nearly simultaneously, would have significantly increased oxygen availability to the surface. The sudden cathodic activity at the surface would act to re-start and potentially accelerate the rate of pit growth. Additionally, the fractured corrosion product could have created a new ionic pathway to the cathode, increasing the cathodic current available to support corrosion and hindering outward diffusion of produced metal cations, therefore increasing the pit growth rate53.

This finding indicates that identifying conditions under which oxide jacking occurs is critical to predicting the maximum depth and volume pits can reach. We speculate that the occurrence of oxide jacking in this material is controlled by the rate at which corrosion product is produced within the pit, i.e. the pit growth rate, and the shape of the pit, particularly the size of the pit mouth. Notably, all pits associated with oxide jacking were associated with initial pit growth rates of 450 μm3 hr−1 or greater. While the spatial resolution of this study was insufficient to accurately characterize the size and shape of pit mouths, the narrow mouth shown in Fig. 5 was typical of pits associated with oxide jacking. Thus, pit morphology may play a controlling role on the occurrence of oxide jacking within this material.

Although data on pit nucleation is relatively limited, this study suggests that increasing RH affected the likelihood of pit nucleation, with roughly 3 times as many droplets associated with a pit at 98RH than at 84RH. This may be partially attributed to the significantly larger droplets present at 98RH than at 84RH. The likelihood of a droplet intersecting susceptible microstructural features, e.g. the Fe-rich intermetallics shown in Supplementary Fig. 141,54,55, that can act as preferential pit nucleation sites increases with increasing droplet size. Similar increases in the likelihood of pit nucleation with increasing drop volume have been observed in 1000-series steels, where pits preferentially nucleate at inclusions beneath droplets21,56.

Over the first ≈70 h after exposure, at all environmental conditions, cumulative volume loss followed a power law. The rate of volume loss at 84RH-060 was an order of magnitude lower than all other conditions. No significant difference in the rate of volume loss was observed between the other three samples. In prior studies of mass change in commercial-purity Al exposed at 98RH, volume loss was observed to increase significantly with increasing salt loading. However, this difference was only observed 150 h after exposure began; within the first 70 h after exposure, Schaller et al.6 observed no significant difference in mass change between samples loaded with 60 and 125 μg cm−2 of NaCl.

Methods

Material

A 0.813 mm diameter 1100 Al wire material was acquired from McMaster-Carr for this study. This material was in the O-temper, i.e. it was annealed after drawing to the final diameter. The composition of this material, in mass percent, was measured using inductively coupled plasma mass spectroscopy and was: Zn 0.003%, Si 0.085%, Mn 0.002%, Mg <0.001%, Fe 0.45%, and Cu 0.047%, with the remainder (99.4%) being Al. The principal axes of this material are defined as the fiber direction (FD), which is parallel to the wire drawing direction and the length of the wire, and the radial direction (RAD), which is parallel to the diameter of the wire.

Samples were extracted from this material perpendicular to the FD and parallel to the FD to characterize the microstructure. Using the methods described in the next section, microstructural characterization was performed using electron backscatter diffraction (EBSD), energy-dispersive X-ray spectroscopy (EDS), and secondary electron imaging. A backscatter electron image of this material is provided in Supplementary Fig. 1. This image reveals the presence of strings of ≈1–10 μm long particles aligned with the wire FD and dispersed throughout the microstructure. As the example EDS maps provided in Supplementary Fig. 1b, c show, these particles were Fe-rich and are presumed to be the Al3Fe intermetallics known to serve as local preferential cathodes in Al alloys51.

EBSD maps reveal that grains are slightly elongated along the wire drawing direction and roughly equiaxed in the RAD plane. These maps are provided as inverse pole figure (IPF) and kernel average misorientation (KAM) maps in Supplementary Fig. 2. The average grain length, defined as the length of the grain parallel to the FD, was 26 μm. The average grain diameter, defined as the length of the grain parallel to the RAD, was 20 μm. By measuring the misorientation between neighboring points within a kernel, KAM maps provide a useful way to visual local misorientations within grains created by geometrically necessary dislocations, see ref. 57 for more information. These maps indicate the presence of some residual dislocation structure in the presence of geometrically necessary dislocations within grains.

Microscopy

All microstructural characterization prior to corrosion was performed using a Zeiss Supra 55VP field emission scanning electron microscope (SEM). An accelerating voltage of 20 kV was used to collect all secondary electron images, EBSD data, and EDS data. Oxford HKL AZtecTM was used to collect EBSD data using a stepsize of 0.5 μm. All EBSD data were analyzed using MTEX58, an extension for MATLAB. During post-processing, no methods were applied to “clean up” the EBSD data, e.g. removing unindexed pixels. For EBSD data analysis, grains were defined by assigning adjacent points that were misoriented by less than 5° to one another to the same grain. Grains smaller than 10 points were merged with neighboring grains.

Specimen preparation

Seven specimens of the 1100 Al wire were prepared for in-situ characterization using XCT. The same procedure used in ref. 10 was used to prepare these specimens. This method is now briefly described.

Specimens approximately 25 long mm were cut from the as-received material. Each specimen was cleaned for 90 s in a solution of 1.0 M NaOH at 60 °C. Each specimen was then rinsed in deionized water, placed in a solution of 70% HNO3 for 30 s, rinsed again with deionized water, and, lastly, dried using compressed air. After this initial preparation, the inkjet printing method described in ref. 59 was used to deposit a uniform field of discrete, picoliter-sized droplets of near-saturated NaCl along the entire surface of the wire. A LogoJET ProH4 inkjet printer (LogoJET USA) was used for this procedure. Four specimens were loaded with 60 μg cm−2 of NaCl. The remaining three specimens were loaded with 200 μg cm−2 of NaCl.

After salt printing, each specimen was encapsulated in a plastic tube, following the procedure described by ref. 10. The tube was attached on one end to a sample holder that could be easily inserted into the XCT system used in this study, see next section for more details. A small sponge was inserted into the other end of the plastic tube. Each sample was subsequently stored in a dry atmosphere until tested.

Immediately before the commencement of each in-situ test, a few droplets of a super-saturated KCl or K2SO4 solution were added to the sponge to create either a 84% or 98% RH atmosphere within the tube, as described by ref. 60. Both ends of the tube were subsequently sealed using a photo-cure epoxy and the entire assembly was placed within the XCT system for in-situ characterization. Note that, aside from salt loading and the super-saturated solution added to the sponge, all samples were prepared and handled identically throughout the study. Lastly, we note that the sponge remained saturated throughout the experiment, i.e. it was still wet after the termination of each experiment.

In-situ XCT Characterization

All XCT data were collected using a Zeiss Xradia Versa 520 (Carl Zeiss XRM, Pleasanton, CA). This is a laboratory-based XCT system. All scans were performed using the following settings: a 4X objective, no beam filter, a power of 5 W, and an accelerating voltage of 60 kV. To give an effective voxel size of 1.25 μm for all scans, the source to sample and sample to detector distances were adjusted. The effective spatial resolution, also known as the minimum resolvable feature size, for all XCT data collected in this study was 15.6 μm3, i.e. 2 × 2 × 2 voxels for three-dimensional features. This approximately corresponds to a hemispherical pit 4 μm in diameter.

Immediately after placing samples within the XCT system, the top of the wire was identified using X-ray radiography. A 1.25 mm tall portion of the wire 3 mm below the top of the wire was then centered within the field of view of the XCT system. For each sample, this same region was subsequently characterized for the duration of in-situ characterization. During characterization, the XCT system remained at room temperature, i.e. 25 °C ± 3 °C.

After identifying the region of interest, in-situ characterization of each specimen proceeded as follows. First, a one hour “warm-up” scan was performed at 60 kV and 5 W, following the manufacturer’s recommendations. This scan was intended to ensure that the X-ray source fully stabilized at the desired accelerating voltage. For all samples, no pits were observed to nucleate during this warm-up scan. Next, 3D tomography data was collected over the 1.25 mm tall portion of the sample within the field of view. This data was acquired by rotating the sample through 360° and collecting a radiographic projection every 0.225° for a total of 1601 projections. Each radiograph was collected using an exposure time of 2 s to ensure that the manufacturer’s recommended 5000 counts was reached through the thickest part of the Al wire. Reference images were automatically collected during the scan. Each reference image consisted of ten frames without the sample in the field of view. These reference images allowed radiographs to be normalized by subtracting this reference image as background. After collecting each dataset, a 3D dataset was automatically reconstructed using the Zeiss XMReconstructor software. This software uses a standard filtered back-projection method to reconstruct data. Simultaneously, collection of the next dataset began. The total collection time for each dataset was 80 min ± 2 min. Thus, the temporal resolution of all XCT datasets collected in this study was 1.33 ± 0.67 h. Note that the accumulated X-ray exposure may affect the pitting process to some degree, but this effect is ignored in the present study.

Using the Zeiss Scout & Scan software, XCT data was set to be collected automatically for the first 101 h after exposure for all samples. This included the 1-hour warm-up scan and 75 scans as described in the previous paragraph. However, due to software errors, in-situ characterization of 1 sample each at 84RH-060, 84RH-200, and 98RH-200 were interrupted 73, 66.3, and 91.7 h after exposure, respectively.

3D data segmentation and analysis

Reconstructed tomography datasets were processed and analyzed using the Dragonfly 3D Software 2021.1 (Object Research Systems Inc, Montreal, Canada, 2021). Phases of interest, such as pits and droplets, were segmented using a combination of deep-learning based segmentation and manual segmentation based on local grayscale values and voxel locations. The deep-learning model used for segmentation is now briefly described.

Deep-learning based segmentation was performed using Keras, an open-source machine learning framework. A three model deep-learning pipeline was employed for data segmentation. The first model (the pit detector model) was used to flag pits within the volume. The second model (the pit segmentation model) segmented the flagged areas. Lastly, a third model (the material segmentation model) was used to segment the Al material from all other phases, including pits, droplets, and air. This workflow is now described in more detail.

First, the pipeline divided the entire volume into overlapping, equal sized 3D subvolumes, or chunks, of size 64 × 64 × 64. These chunks were passed to the pit detector model, which produced a binary classification indicating if the current chunk contained a pit. If so, the chunk was passed to the pit segmentation model which performed a per-voxel segmentation on that chunk into one of two classes: pit or nonpit. Lastly, the material model was applied to separate wire material from air. The results from the pit segmentation and material model were combined to obtain a full segmentation for all three classes, pit, material, and air. Note, when segmenting pits, droplets were segmented as air - a separate approach using a conventional threshold-based approach was used to segment the droplets whose volumes are reported in Fig. 1. This process was repeated for all chunks in the volume, and once finished, the subvolumes are joined into a full segmentation of the input volume. These three models are now described in more detail.

The pit detector model was a sequence of multiple 3D CNN layers stacked in unison with the appropriate pooling and normalization intermediaries. These layers re-scaled the resolution of any particular chunk (passed in as input) and propagated useful pixel information downward for the final dense layer classification. Our pit detector model took in subvolumes of size 64 × 64 × 64 and was trained to determine if any pit voxels were present in the central 32 × 32 × 32 region of this subvolume. The additional voxels in each dimension served to add additional context to aid the model in performing its classification. This final classification was a binary true or false, indicating whether pit voxels were found in the center of the subvolume and was used to decrease the overall false positive rate in the volume. The subvolumes that were flagged by the pit detector model were first center-cropped to a 32 x 32 x 32 window and then passed to the pit segmentation model.

The pit segmentation model and the material segmentation model both used a V-Net architecture61. The segmentation models act on input chunks (32 x 32 x 32 in the pit segmentation case, 128 x 128 x 128 in the material segmentation case) and were comprised of multiple downward convolution layers, successively exchanging spatial context for channel context. That information was paired with an equal set of transposed convolutions, which served to gradually restore spatial context until producing the same sized output. Combining these two results, this yields a per-voxel segmentation for that particular chunk into one of three classes for each voxel: material, pit, or air.

This deep-learning based model was used to perform initial segmentation on all 3D datasets collected during this investigation. This initial segmentation then served as a baseline from which to perform manual segmentation. Notably, all 3D datasets were manually segmented using the features identified using deep-learning as a reference. Subsequently, local grayscale values and voxel location relative to the surface were used to identify and segment pits. These segmented data were used to evaluate the volume and surface area of pits.

Based on the voxel size used for this study, the minimum pit size that could be identified was 15.6 μm3. A pit was defined as nucleated once it met or exceeded this threshold. The timestep associated with pit nucleation was identified for each pit. Based on this information, the duration of growth for each pit was measured as the time elapsed from the timestep preceding that at which it was first observed to the last timestep at which any visible growth occurred. Two pits continued growing after XCT characterization was terminated and, as such, no determination of pit growth duration could be made for these two pits.

Droplet volume and coverage area were also assessed using XCT data. Droplets were manually segmented based on local grayscale value and location relative to the wire surface. The minimum droplet size that could be assessed from XCT data was 15.6 μm3. The volume of droplets and the total droplet coverage area from representative samples exposed at each environment were characterized using XCT data collected 10 h after exposure.

The volume of individual droplets associated with pits were assessed at the first timestep associated with a linear rate of growth for that pit. This timestep is highlighted in Fig. 3a. As this timestep varied pit to pit, the time elapsed between pit nucleation and when droplet volume was measured varied between 1.3 and 6.2 h. To assess if droplet volume varied significantly with time in the first 7 h after a pit nucleated, the volumes of droplets associated with two pits were measured for the first seven hours after each pit nucleated. In both cases, droplet volume varied by 5% or less over these first 7 h.

Data availability

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author, Philip J. Noell, upon reasonable request.

Code availability

Codes are available upon reasonable request to the corresponding author, Philip J. Noell.

References

Ghahari, S. et al. Pitting corrosion of stainless steel: measuring and modelling pit propagation in support of damage prediction for radioactive waste containers. Corros. Eng. Sci. Technol. 46, 205–211 (2011).

Ghahari, S. M. et al. In situ synchrotron X-ray micro-tomography study of pitting corrosion in stainless steel. Corros. Sci. 53, 2684–2687 (2011).

Örnek, C. et al. Time-dependent in situ measurement of atmospheric corrosion rates of duplex stainless steel wires. NPJ Mater. Degrad. 2, 1–15 (2018).

Eguchi, K., Burnett, T. L. & Engelberg, D. L. X-Ray tomographic characterisation of pitting corrosion in lean duplex stainless steel. Corros. Sci. 165, 108406 (2020).

Eguchi, K., Burnett, T. L. & Engelberg, D. L. X-ray tomographic observation of environmental assisted cracking in heat-treated lean duplex stainless steel. Corros. Sci. 184, 109363 (2021).

Schaller, R. F., Jove-Colon, C. F., Taylor, J. M. & Schindelholz, E. J. The controlling role of sodium and carbonate on the atmospheric corrosion rate of aluminum. NPJ Mater. Degrad. 1, 1–8 (2017).

Katona, R. et al. Quantitative assessment of environmental phenomena on maximum pit size predictions in marine environments. Electrochim. Acta. 370, 137696 (2021).

Srinivasan, J. et al. Long-term effects of humidity on stainless steel pitting in sea salt exposures. J. Electrochem. Soc. 168, 021501 (2021).

Turnbull, A. Corrosion pitting and environmentally assisted small crack growth. Proc. Math. Phys. Eng. Sci. 470, 20140254 (2014).

Noell, P. J., Schindelholz, E. J. & Melia, M. A. Revealing the growth kinetics of atmospheric corrosion pitting in aluminum via in situ microtomography. NPJ Mater. Degrad. 4, 1–10 (2020).

Rafla, V. N., King, A. D., Glanvill, S., Davenport, A. & Scully, J. R. Operando Assessment of Galvanic Corrosion Between Al-Zn-Mg-Cu Alloy and a Stainless Steel Fastener Using X-ray Tomography. Corrosion 74, 5–23 (2018).

Glanvill, S. J., du Plessis, A., Street, S. R., Rayment, T. & Davenport, A. J. In Situ X-ray Tomography Observations of Initiation and Propagation of Pits During Atmospheric Corrosion of Aluminium Alloy AA2024. J. Electrochem. Soc. 168, 031508 (2021).

Singh, S. S., Williams, J. J., Xiao, X., De Carlo, F. & Chawla, N. In Fatigue of Materials II 17–25 (Springer, 2013).

Singh, S. et al. In situ investigation of high humidity stress corrosion cracking of 7075 aluminum alloy by three-dimensional (3D) X-ray synchrotron tomography. Mater. Res. Lett. 2, 217–220 (2014).

Singh, S. S. et al. Measurement of localized corrosion rates at inclusion particles in AA7075 by in situ three dimensional (3D) X-ray synchrotron tomography. Corros. Sci. 104, 330–335 (2016).

Singh, S. S., Stannard, T. J., Xiao, X. & Chawla, N. In situ X-ray microtomography of stress corrosion cracking and corrosion fatigue in aluminum alloys. JOM 69, 1404–1414 (2017).

Stannard, T. J. et al. 3D time-resolved observations of corrosion and corrosion-fatigue crack initiation and growth in peak-aged Al 7075 using synchrotron X-ray tomography. Corros. Sci. 138, 340–352 (2018).

Vallabhaneni, R., Stannard, T. J., Kaira, C. S. & Chawla, N. 3D X-ray microtomography and mechanical characterization of corrosion-induced damage in 7075 aluminium (Al) alloys. Corros. Sci. 139, 97–113 (2018).

Niverty, S., Kale, C., Solanki, K. N. & Chawla, N. Multiscale investigation of corrosion damage initiation and propagation in AA7075-T651 alloy using correlative microscopy. Corros. Sci. 185, 109429 (2021).

Niverty, S. & Chawla, N. 4D microstructural characterization of corrosion and corrosion-fatigue in a Ti–6Al–4V/AA 7075-T651 joint in saltwater environment. Mater. Sci. Eng., A 825, 141886 (2021).

Risteen, B., Schindelholz, E. & Kelly, R. Marine aerosol drop size effects on the corrosion behavior of low carbon steel and high purity iron. J. Electrochem. Soc. 161, C580 (2014).

Schindelholz, E., Risteen, B. & Kelly, R. Effect of relative humidity on corrosion of steel under sea salt aerosol proxies I. NaCl. J. Electrochem. Soc. 161, C450–C459 (2014).

Weirich, T. D. et al. Humidity Effects on Pitting of Ground Stainless Steel Exposed to Sea Salt Particles. J. Electrochem. Soc. 166, C3477–C3487 (2019).

Blücher, D. B., Lindström, R., Svensson, J. & Johansson, L. The effect of CO 2 on the NaCl-induced atmospheric corrosion of aluminum. J. Electrochem. Soc. 148, B127–B131 (2001).

Chen, Z., Cui, F. & Kelly, R. Calculations of the cathodic current delivery capacity and stability of crevice corrosion under atmospheric environments. J. Electrochem. Soc. 155, C360 (2008).

Alexander, C. L. et al. Oxygen reduction on stainless steel in concentrated chloride media. J. Electrochem. Soc. 165, C869 (2018).

Katona, R., Carpenter, J., Schindelholz, E. & Kelly, R. Prediction of maximum pit sizes in elevated chloride concentrations and temperatures. J. Electrochem. Soc. 166, C3364 (2019).

Katona, R. et al. Editors’ Choice—Natural Convection Boundary Layer Thickness at Elevated Chloride Concentrations and Temperatures and the Effects on a Galvanic Couple. J. Electrochem. Soc. 168, 031512 (2021).

Mahmood, S., Gallagher, C. & Engelberg, D. Atmospheric corrosion of aluminum alloy 6063 beneath ferric chloride corrosion product droplets. Corrosion 76, 985–994 (2020).

Schindelholz, E. & Kelly, R. G. Wetting phenomena and time of wetness in atmospheric corrosion: a review. Corros. Rev. 30, 135–170 (2012).

Bryan, C. R. et al. Physical and chemical properties of sea salt deliquescent brines as a function of temperature and relative humidity. Sci. Total Environ. 824, 154462 (2022).

Roberge, P., Klassen, R. & Haberecht, P. Atmospheric corrosivity modeling—A review. Mater. Des. 23, 321–330 (2002).

Chung, S., Lin, A., Chang, J. & Shih, H. EXAFS study of atmospheric corrosion products on zinc at the initial stage. Corros. Sci. 42, 1599–1610 (2000).

Schindelholz, E., Risteen, B. & Kelly, R. Effect of relative humidity on corrosion of steel under sea salt aerosol proxies: II. MgCl2, artificial seawater. J. Electrochem. Soc. 161, C460 (2014).

Almuaili, F., McDonald, S., Withers, P. & Engelberg, D. Application of a quasi in situ experimental approach to estimate 3-D pitting corrosion kinetics in stainless steel. J. Electrochem. Soc. 163, C745 (2016).

Knight, S. et al. In situ X-ray tomography of intergranular corrosion of 2024 and 7050 aluminium alloys. Corros. Sci. 52, 3855–3860 (2010).

Landron, C. et al. Resolution effect on the study of ductile damage using synchrotron X-ray tomography. Nucl. Instrum. Methods Phys. Res. Sect. B: Beam Interact. Mater. At. 284, 15–18 (2012).

Ramandi, H. L., Chen, H., Crosky, A. & Saydam, S. Interactions of stress corrosion cracks in cold drawn pearlitic steel wires: An X-ray micro-computed tomography study. Corros. Sci. 145, 170–179 (2018).

Ghahari, M. et al. Synchrotron X-ray radiography studies of pitting corrosion of stainless steel: Extraction of pit propagation parameters. Corros. Sci. 100, 23–35 (2015).

Noell, P. J. et al. The evolution of pit morphology and growth kinetics in aluminum during atmospheric corrosion. NPJ Mater. Degrad. 7, 12 (2023).

Morton, S. & Frankel, G. Atmospheric pitting corrosion of AA7075‐T6 under evaporating droplets with and without inhibitors. Mater. Corros. 65, 351–361 (2014).

Liang, H., Liu, J., Schaller, R. F. & Asselin, E. A new corrosion mechanism for X100 pipeline steel under oil-covered chloride droplets. Corrosion 74, 947–957 (2018).

Tsuru, T., Tamiya, K.-I. & Nishikata, A. Formation and growth of micro-droplets during the initial stage of atmospheric corrosion. Electrochim. Acta 49, 2709–2715 (2004).

Zhang, J., Wang, J. & Wang, Y. Micro-droplets formation during the deliquescence of salt particles in atmosphere. Corrosion 61, 1167–1172 (2005).

Manning, M. Geometrical effects on oxide scale integrity. Corros. Sci. 21, 301–316 (1981).

Harris, J. & Crossland, I. Mechanical effects of corrosion: an old problem in a new setting. Endeavour 3, 15–26 (1979).

Wang, X. et al. Research on internal monitoring of reinforced concrete under accelerated corrosion, using XCT and DIC technology. Constr. Build. Mater. 266, 121018 (2021).

Zhou, X.-r, Thompson, G. & Scamans, G. The influence of surface treatment on filiform corrosion resistance of painted aluminium alloy sheet. Corros. Sci. 45, 1767–1777 (2003).

Bentea, L., Watzky, M. A. & Finke, R. G. Sigmoidal nucleation and growth curves across nature fit by the Finke–Watzky model of slow continuous nucleation and autocatalytic growth: explicit formulas for the lag and growth times plus other key insights. J. Phys. Chem. C. 121, 5302–5312 (2017).

Myhrvold, N. P. Revisiting the estimation of dinosaur growth rates. PLoS One 8, e81917 (2013).

Ambat, R., Davenport, A. J., Scamans, G. M. & Afseth, A. Effect of iron-containing intermetallic particles on the corrosion behaviour of aluminium. Corros. Sci. 48, 3455–3471 (2006).

Key, J. W. & Kacher, J. Establishing first order correlations between pitting corrosion initiation and local microstructure in AA5083 using automated image analysis. Mater. Charact. 178, 111237 (2021).

Ansari, T. Q., Luo, J.-L. & Shi, S.-Q. Modeling the effect of insoluble corrosion products on pitting corrosion kinetics of metals. NPJ Mater. Degrad. 3, 28 (2019).

Thomson, M. & Frankel, G. Atmospheric pitting corrosion studies of AA7075-T6 under electrolyte droplets: part I. Effects of droplet size, concentration, composition, and sample aging. J. Electrochem. Soc. 164, C653 (2017).

Li, J., Maier, B. & Frankel, G. Corrosion of an Al–Mg–Si alloy under MgCl2 solution droplets. Corros. Sci. 53, 2142–2151 (2011).

Li, S. & Hihara, L. Atmospheric corrosion initiation on steel from predeposited NaCl salt particles in high humidity atmospheres. Corros. Eng. Sci. Technol. 45, 49–56 (2010).

Wright, S. I., Nowell, M. M. & Field, D. P. A review of strain analysis using electron backscatter diffraction. Microsc. Microanal. 17, 316–329 (2011).

Bachmann, F., Hielscher, R. & Schaeben, H. In Solid State Phenom. 63–68 (Trans Tech Publ).

Schindelholz, E. & Kelly, R. Application of inkjet printing for depositing salt prior to atmospheric corrosion testing. Electrochem. Solid-State Lett. 13, C29 (2010).

Greenspan, L. Humidity fixed points of binary saturated aqueous solutions. J. Res. Natl Bur. Stand. Sec. A 81, 89–96 (1977).

Milletari, F., Navab, N. & Ahmadi, S.-A. In 2016 fourth international conference on 3D vision (3DV). 565-571 (Ieee).

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to acknowledge James Griego, Jason Taylor, and Priya Pathare. Supported by the Laboratory Directed Research and Development program at Sandia National Laboratories, a multimission laboratory managed and operated by National Technology and Engineering Solutions of Sandia LLC, a wholly owned subsidiary of Honeywell International Inc. for the U.S. Department of Energy’s National Nuclear Security Administration under contract DE-NA0003525. The views expressed in the article do not necessarily represent the views of the U.S. DOE or the United States Government.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

P.J.N., I.C., R.M.K., and M.A.M. performed in-situ XCT experiments and analysis of XCT data. E.K. and M.A.M. performed microscopy of corroded samples. P.J.N., M.A.M., A.T.P., and E.J.S. performed analysis of microscopy data. All authors discussed and contributed to the writing of the paper.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons license and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Noell, P.J., Pham, B.T., Campbell, I. et al. Pit growth kinetics in aluminum: effects of salt loading and relative humidity. npj Mater Degrad 7, 61 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41529-023-00382-1

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41529-023-00382-1