Abstract

There is a need for high-throughput, scale-relevant, and direct electrochemical analysis to understand the corrosion behavior and sensitivity of nuclear materials that are exposed to extreme (high pressure, temperature, and radiation exposure) environments. We demonstrate the multi-scale, multi-modal application of scanning electrochemical cell microscopy (SECCM) to electrochemically profile corrosion alterations in nuclear alloys in a microstructurally resolved manner. Particularly, we identify that both mechanically deformed and irradiated microstructures show reduced charge-transfer resistance that leads to accelerated oxidation. We highlight that the effects of mechanical deformation and irradiation are synergistic, and may in fact, superimpose each other, with implications including general-, galvanic-, and/or irradiation-activated stress-corrosion cracking. Taken together, we highlight the ability of non-destructive, electrochemical interrogations to ascertain how microstructural alterations result in changes in the corrosion tendency of a nuclear alloy: knowledge which has implications to rank, qualify and examine alloys for use in nuclear construction applications.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

With the advent of the nuclear age, alloys have found widespread use in highly aggressive “radiation exposure” environments, e.g., in nuclear power plants (NPPs), nuclear waste disposal facilities1, and in weapons systems. In such environments, alloys may experience physical damage (e.g., via deformation and irradiation)2,3, and electrochemical degradation (e.g., via corrosion)4. As one of the most negative scenarios, synergistic degradations wherein the physical and electrochemical degradation may superimpose (e.g., stress corrosion cracking: SCC, irradiation-assisted SCC: IASCC, etc.)5,6. Spatially and temporally resolved, and scale relevant examinations are critical to understand and reveal the key variables and features that provoke and stimulate alloy degradation. Such understanding is needed not only to predict and prevent catastrophic failure, but also to screen, rank and order failure-resistant materials for use in nuclear and other extreme-environment applications.

While numerous efforts have sought to characterize damage in nuclear alloys, such tasks are challenging due to the spread of damage type and damage allocation at micro-to-macro scales7. While microstructural post-deformation and post-irradiation examinations (PIE) have been extensively developed over the years, better electrochemical technologies are still required to link corrosion behavior and microstructural damage evolutions. Prevailing analytical approaches can only reveal disjointed microstructural or corrosion behaviors—and that too, at defined (i.e., not across) scales. For instance, transmission electron microscopy (TEM) and atom probe tomography (APT) reveal localized microstructural damages8,9,10; whereas conventional corrosion assessments (voltammetry, impedance spectroscopy, etc.) reveal averaged behavior while overlooking localized features11,12. Therefore, critical knowledge gaps persist in understanding the microstructure-corrosion interplay across scales. For this reason, forecasting the evolution of IASCC remains impractical. However, many recent developments of SECCM technologies have resolved the scale limits imposed by conventional methods13,14,15. For instance, by using a micropipette to confine corrosion evaluation in a nano- to micrometer-sized microdroplets, SECCM readily resolves small microstructural features14,16,17,18. The scanning probe technique has been consequently applied to study the mechanism of SCC. For instance, in a previous study, we have demonstrated that surface electrochemical reactivity is correlated with strain-induced heterogeneities (e.g., martensite, point defects and dislocations) in austenitic stainless steels, even though these features are identical in elemental composition with the austenitic matrix4. In addition, many other studies have reveal that, corrosion can be accelerated not only by plastic strain-induced microstructures, but can also activated by elastic stresses19,20,21,22.

Akin to the deformation damage, irradiation also induces microstructural defects23, which results in accelerated surface oxidation in nuclear reactor environments24. In both cases, irradiation and mechanical deformation increase the chemical reactivity in similar manners, i.e., by inducing defected phase-transformation (e.g., martensitic transformation)25,26 or building stored energy in lattices27,28. This is significant since the enhancement of corrosion reactivity is linked to the chemical potential that is in turn elevated by mechanical deformation (plastic strain) and irradiation (i.e., displacement per atom, dpa). Based on these linkages, herein, we develop an electrochemical post-damage examination (Ec-PDE) approach to achieve multiscale, multimodal analyses on deformed and irradiated nuclear materials, herein choosing as an example, austenitic stainless steel (304L).

Results and discussion

Deformation-induced corrosion reactivities

Cold working is extensively used to improve strength, and, for nuclear industry applications, to introduce sinks for radiation defects. However, corrosion-related premature failures of cold-worked materials may be a serious concern. Amongst others, corrosion associated with strain localization is the most difficult to ascertain as the strain concentration varies at the (1) macro- and (2) in-grain levels8,29,30,31. Therefore, we performed PD polarization and EIS to characterize the strain concentration at all levels in a cold-worked 304L stainless steel. Here, miniature tensile test specimens with a gauge length of 7.6 mm (see Supplementary Fig. 1) were elongated up to 30% tensile strain at room temperature and at a strain rate of 5 × 10−4 s−1. Such deformation resulted in uniformly distributed strain in the gauge part at the macro-scale32. However, EBSD revealed the non-uniform microscale strain distribution. The strain-induced phases, i.e., deformation bands in austenite and martensite surrounding the δ-ferrite can be seen in the EBSD- phase and kernel average misorientation (KAM) maps (Fig. 1a, b). Such strain localization is caused by dislocation motion impeded by δ-ferrite33, and induces localized corrosion and a high SCC susceptibility34. Scanning probe PD experiments (with ~7 μm2 microdroplet sizes) were then superimposed on top of the EBSD-mapped area (Fig. 1c). Tafel-fitting of the PD curves indicates a corrosion current density (Icorr) that is higher in regions of greater strain (47.5 ± 6.4 μA/cm2) as compared to less deformed regions (36.7 ± 4.4 μA/cm2, see Fig. 1b, d, e). Although the high scan rate (20 mV/s) promote greater Icorr35 as compared to those published in literature (3–8 μA/cm2, measured at 1 mV/s)36,37, these results suggest about 29% enhancement in corrosion rates in the strain-concentrated areas.

(a) and (b) showing, respectively, EBSD- phase and kernel average misorientation (KAM) maps showing the strain localization. c Polarized light microscope images show the 8 × 16 microdroplet matrix where the PD polarization tests were performed. The microdroplets are ~3 μm in diameter. d A contour plot of the Icorr values regressed via Tafel fitting the collected polarization curves shown in (e). A 20 mM LiCl solution was used in the scanning-PD analysis.

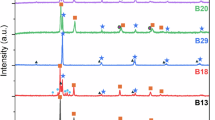

On the other hand, PD analysis can stimulate heterogeneous corrosion (e.g., pitting and transpassive corrosion), whereas EIS can probe the surface in a non-destructive manner and directly probe the passive film at the open circuit potential (OCP). First, frequency-sweep (10 kHz to 1 Hz) EIS measurements were performed within two grains characterized by distinct microstructures (Fig. 2a). One austenitic grain (upper left in Fig. 2a) was severely deformed and filled with strain-induced martensite and deformation bands; whereas the other grain (lower right) is mainly austenitic with less strain-induced features. Note that, such microstructural variation is not caused by inclusions/impurities such as δ-ferrites. Instead, it might be explained by intrinsic differences in stress-coping ability between grains38. Associated with those microstructural dissimilarities, the two grains are also characterized by distinguished impedance spectra (Fig. 2b). We were able to regress the charge-transfer resistances (RCT) by fitting the EIS spectra with the simplified Randles circuit model (Fig. 2b), which implies a single-layered structure of the passive film. The RCT values indicate the austenitic grain is ~1.7 fold more resistant to charge transfer (3.4 ± 0.5 kΩ cm2) as compared to the most deformed grain (2.0 ± 0.5 kΩ cm2). The reduction in RCT is consistent with the previously determined changes in corrosion rates (Icorr), suggesting that strain-induced features cause differences in passivation between two grains—a phenomenon that cannot be resolved by conventional corrosion tests. The RCT values acquired at room temperature may suggest a propensity for complex in-reactor corrosion attributed to radiolysis and oxidation at elevated pressure and temperature conditions. For instance, strong oxidants are produced by radiolysis (e.g. hydroxyl radicals and H2O2)39 in nuclear environments, and the passive layer is the main barrier impeding charge transfer between steel and radiolytic products. Therefore, regions with lower RCT values may undergo fast oxidation in reactor environments, concurring with high residual strain/stress, which will lead to a high susceptibility for the initiation of SCC/IASCC40,41.

a Nyquist plots (dots) and equivalent circuit fittings (lines) of the localized impedance spectra in superposition with the polarized light microscope (PLM) image. The microdroplets matrix cover two grains characterized by distinguished microstructures. The numbers indicate corrosion resistance values (RCT) regressed by the equivalent circuit fitting, as shown in (b). The grain boundary is identified based on the EBSD map shown in Fig. S3. b Illustration of the Randle circuit in correlation to the droplet-passive film-metal configuration, where RS represents the system (solution + QRCE) resistance, RCT and CPEOX are the charge-transfer (corrosion) resistance and the capacitive response of the passive film, respectively. The fitted curves are plotted as solid lines in (a). c PLM image showing the 11 × 11 microdroplet scanned during a constant frequency impedance mapping at 1 Hz. d PLM image revealing strain localization in the same area after droplets were removed. Note that, no surface degradation was observed after the impedance scan. e Contour plots of the AC impedance at 1 Hz (|Z|1Hz) showing the correlation between the corrosion resistance and strain localization. The scale bars are 20 μm in length.

To effectively discriminate high susceptibility regions from impedance maps of larger areas, we simplified the AC-impedance mapping to constant-frequency scans, wherein the magnitude of impedance (|Z|) was captured at a fixed frequency (1 Hz) to accommodate fast-scanning of multipoint matrices. The frequency of 1 Hz was selected as the measured impedance well correlates with the RCT (see Fig. 2a, e), while the dwelling time at each point is only a few seconds. As shown in Fig. 2, the strain localization areas were outlined by the impedance map of |Z|1Hz (Fig. 2c–e). The regions near ferrite-martensite and deformation bands exhibited meaningfully lower |Z|1Hz (1.8 ± 0.1 kΩ cm2) as compared to the pristine austenite grain (>2.1 kΩ cm2). These |Z|1Hz values are compatible with the RCT values determined in full-spectrum EIS tests. As a result, a map of |Z|1Hz can effectively reveal low RCT regions without tedious fittings of every EIS spectrum (see Supplementary Fig. 3).

Until this point, the aforementioned tests encompass micro(n)-scale, in-grain level investigations. However, corrosion and stress-induced heterogeneities can manifest at the bulk scale (millimeter to centimeter). For instance, it is well known that localized yielding and necking may take place at large geometric heterogeneities that interrupt the stress flow (i.e., stress concentrations)32. When cracking initiates, plastic zones develop near the crack tip, resulting in disproportionate plastic strain across regions that may encompass hundreds of grains42. Consequently, corrosion/surface reactivity assessments should also include larger scale analysis. Towards this end, we used scanning AC-impedance analyses to examine a tensile specimen as it underwent necking and fracture (Fig. 3a). As shown in Fig. 3b, EIS spectra were acquired from where the plastic strain progressively increased from the head to gauge. This region of necking reflects the highest effective plastic strain (EPS). Significantly, the regressed charge-transfer resistance (RCT) is inversely correlated with the EPS quantified via COMSOL simulations (see Fig. 3b), suggesting bulk-scale EPS can elevate steel’s electrochemical (corrosion) reactivity. As compared to the undeformed head (RCT = 4.2 kΩ cm2), the RCT reduced to 3.3 kΩ cm2 at the gauge and further decreased to 2.8 kΩ cm2 at the necking region where the deformation is the most severe. The EPS was also examined in the region of necking and well captured the distribution of severe deformation that led to fracture. As shown in Fig. 3c, the COMSOL simulation predicted a contour of >0.95 EPS denoted by the white arrows, which is well represented by the contour of the fractured rim (Fig. 3d). Interestingly, the severe deformation can also be mapped electrochemically. For instance, the|Z |1Hz map outlines the same contour of the EPS distribution, this is manifested by greater |Z|1Hz values than associated with areas having a lower EPS (see red arrows in Fig. 3c, e), and the regions that are most adjacent to fracture exhibit the lowest corrosion resistance. These outcomes suggest that whether the deformation was pre-induced or developed in-service, SCC can be initiated and accelerated due to the preferential oxidation of localized plastic zone6,23,43,44. Additionally, unevenly-distributed EPS can also activate micro- and macro-galvanic corrosion events4, further accelerating the corrosion/oxidation rates of the most deformed regions. This demonstration is significant as the impedance mapping indicate an ability to forecast the SCC susceptible regions across length scales.

a Light microscopy image and COMSOL simulation showing the deformed-to-fracture 304L specimen and the distribution of the effective plastic strain (EPS). The scale bar is 2 mm in length. b Regressed RCT values are plotted along with the EPS acquired from COMSOL simulation. Error bars were calculated from three repeated experiments. c EPS distribution mapping and (d) a 0.7 mm × 0.7 mm matrix of microdroplets at the region of necking. e Matrix plot of |Z |1Hz that agrees with the simulated strain distribution. Each pixel represents |Z |1Hz acquired from each droplet, as shown in (d). A 20 mM LiCl + 5% HNO3 solution was used in the impedance scans. Scale bars in (c) and (d) are 0.7 mm in length.

Interplays of irradiation, deformation, and corrosion

To more clearly unentangle irradiation-assisted SCC (namely, IASCC), we exploited the surface electrochemical reactivities solely induced by irradiation. Herein, an annealed 304L steel was partially irradiated to 1.1 dpa. Although the irradiation did not cause any apparent surface alternations, the irradiated area was clearly revealed by the impedance (|Z|1Hz) map characterized by low charge-transfer resistances (see Fig. 4a). As such, irradiation induces point defects, dislocation loops, etc.23, which lead to a defective passivation film and enhanced corrosion activity. In addition, the concentration of irradiation-induced lattice defects is also manifested by hardness elevation, i.e., irradiation hardening. In fact, the evolution of |Z|1Hz correlates well with the irradiation-induced hardening (Fig. 4b): the irradiated region features a lower |Z|1Hz of 2.1 ± 0.5 kΩ cm2, but was hardened to 209 ± 10 HV. In contrast, a hardness of 148 ± 11 HV was measured for the non-irradiated region, which shows a higher |Z|1Hz value of 3.7 ± 0.6 kΩ cm2. Interestingly, progressive (somewhat linear) crossover in hardness and |Z|1Hz values were observed at the transition region between 0 and 1.1 dpa. Such a blurred boundary between irradiation and unirradiated regions is likely due to the scattering of the ion beam45. But the progressive |Z|1Hz values imply the surface impedance is also sensitive to smaller irradiation dose (i.e., <1 dpa) induced lattice defects.

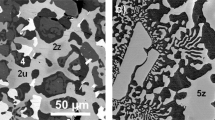

a An optical image showing matrices of microdroplets and Vickers hardness indents. The microdroplets are 50 μm apart and the hardness indents are 10 μm apart. The scale bar is 200 μm in length. b AC-impedance at 1 Hz is consistent with hardness measurements, revealing the irradiated and unirradiated regions, the transition region is highlighted by red dashed lines. The error bars of |Z|1Hz show the standard deviation of five repeat measurements. In an irradiated and deformed (1% strain) 304L sample, dislocation channels (DCs) are evidenced by the surface height steps. c Surface topography and (d) |Z|1Hz maps acquired from the same area indicating the DCs feature a significantly reduced corrosion resistance. The scale bar in (c) is 20 μm in length, and a 20 mM LiCl + 5% HNO3 solution was used in all impedance scans. e High-angle annular dark-filed (HAADF) TEM images showing the surface steps and the highly distorted lattice within a DC. The scale bar is 50 nm in length. f Atomic resolution image of the DC displaying multiple edge and partial dislocations on the \(\left\{1\bar{1}1\right\}\) planes as shown by its Fast Fourier transform (inset). The scale bar is 1 nm in length.

When the irradiated sample is further subjected to mechanical deformation, a small strain (1%) can readily cause severe dislocation channeling in the irradiated lattice (see Fig. 4c)46,47,48. The dislocation channels (DCs) are signified by the 20-to-150 nm slip steps found on the sample surface. Evident corrosion susceptibilities of the DCs are revealed by the scanning impedance measurements conducted via constant frequency and frequency sweeps (see Fig. 4d and Supplementary Fig. 6). Note that, an irradiation of 1.1 dpa alone can cause a 40% reduction in steel’s oxidation resistance (|Z|1Hz from 3.7 ± 0.6 kΩ cm2 to 2.1 ± 0.5 kΩ cm2), and the resistance is further reduced to 1.2 ± 0.2 kΩ cm2 at DCs. Such significant reduction in charge-transfer resistance will result in fast corrosion of the surface steps, and has been confirmed by studies in simulated reactor environments46,49. It is indicated that the high corrosion/oxidation tendency of DCs is attributed to the following: (1) the highly distorted lattice (see Fig. 4e) which stores elastic energy at defects such as dislocation networks (Fig. 4f), thereby elevating the chemical potential and reactivity of the alloying atoms27,28. (2) DC formation leads to the formation of abrupt surface steps, which mechanically disrupt the original oxide film and expose the metal atoms directly to the corrosive environments. In fact, equivalent circuit fitting of the EIS spectra confirms the rupture of the oxide layer, leading to the reduced surface impedance values (see Supplementary Fig. 6). Moreover, the surface steps also disrupt stress flow and cause stress concentration, such mechanical–chemical interplay is likely the root cause of IASCC initiation Importantly, this study provides a non-destructive approach to locate and assess these detrimental features.

In summary, we have developed an electrochemical post-damage examination (Ec-PDE) approach to understand and elaborate the underpinnings of IASCC initiation and propagation—across length scales. Ec-PDE encompasses multiscale and multimodal approaches to electrochemically examine the interplay between irradiation, deformation, and corrosion. Our results show that deformation and irradiation induced alterations of microstructures can elevate the steel’s corrosion tendency, which can be attributed to lattice distortion and disruption of surface oxide films. Both deformation- and irradiation- induced damage similarly reduce corrosion impedance. The measured corrosion rate and surface impedance are quantitatively correlated with the extent and magnitude of strain concentrations and irradiation dose (i.e., dpa). Because of its ability to reveal corrosion activity at micro-to-macro scales, the methodology developed herein can be utilized to predict SCC and IASCC susceptibilities while accommodating both the complex geometries, and diversity of materials used in nuclear components. More importantly, the fast turnaround times of the techniques allow agile adaptation for continuously evolving reactor designs, thereby providing a means for accurate and high-throughput corrosion evaluations, and screening of the microstructural alternations that can cause the degradation of current/new alloy materials.

Methods

Sample preparation

A hot rolled 304L stainless steel (ArcelorMittal) with the nominal composition listed in Table 1 was sectioned into miniature tensile specimens shown in Fig. 1a50,51. In deformation tests, two specimens were respectively elongated to a 30% strain and fracture under uniaxial tension at a strain rate of 5 × 10-4 s−1. To make samples for SECCM, each sample was attached to a copper wire, and then embedded in epoxy resin. The exposed surfaces were successively polished (N.B., using the 50 nm colloidal silica as the final step) until the surface featured a mean roughness Sa < 10 nm. After polishing, the samples were stored in a desiccator before used.

Irradiation

A 304L steel tensile specimen and a spacer (see Supplementary Fig. 1) were annealed at 1050 °C for 3 h to produce solution-treated monophasic austenitic microstructure, with a grain size on the order of tens of micrometers. The specimens were partially irradiated at 300 °C by using a 1.5 MeV proton ([H+]) beam (generated by the NEC 3 MV tandem ion accelerator, LANL) until a target fluence of 1.84 × 1019 ions/cm2 was attained. A flat-region irradiation damage level of 1.11 dpa was calculated based on full-cascade SRIM simulations52. Thereafter, the tensile specimen was elongated to a 1% strain under uniaxial tension at a strain rate of 5×10-4 s-1.

Microstructural characterization

The crystallographic orientations of the grains were studied using a Scanning Electron Microscopy (SEM, Tescan Mira3) equipped with an electron backscatter diffraction detector (EBSD, Oxford Ultim Max). The acceleration voltage and step size used were 20 kV and 500 nm, respectively. The EBSD data were subsequently analyzed using the OIM Analysis® software.

A cross-sectional thin slide from the irradiated and deformed surface was prepared using Focused Ion Beam (FIB) ablation. An FEI Nova 600 Nanolab Dual-Beam Focused Ion Beam-Scanning Electron Microscope (FIB-SEM) was used for this purpose. High-resolution transmission electron microscopy (HRTEM) of the characteristic irradiated microstructure was performed using a FEI Titan 300-kV scanning transmission electron microscope (STEM).

Vickers hardness indentations were performed under a load of 200 gram force (gf) and loading time of 15 s, 20 indentations were made 100 μm apart across the irradiated and unirradiated regions of the spacer.

Scanning probe analysis

The surface reactivity of the deformed and [H+]-irradiated 304L steels were evaluated using a scanning electrochemical microscope (HEKA ElProScan, see Fig. 5a). The instrument is equipped with micropipettes with a 1.8 ± 0.3 μm opening to probe spatially resolved electrochemical responses (see Fig. 5b, c). The micropipettes were made at 700 °C by a pipette puller (Sutter P-1000), using filamented borosilicate glass tubes (1 mm ID, 1.5 mm OD). The SECCM tests were performed with the micropipettes filled with 0.2 M LiCl or 0.2 M LiCl + 5% HNO3 solutions. N.B., Lithium is commonly used in pressurized water reactors (PWRs) as a coolant additive, therefore, LiCl as a potential coolant contaminant53, was used to promote measurable corrosion signals; and the 0.2 M LiCl + 5% HNO3 solution are used to dissolve surface hydroxides and reveal the corrosion resistance of only the protective “barrier” oxides. During scanning, the steel samples were connected as the working electrode and an AgCl-coated silver wire (Ag/AgCl) were inserted in the micropipette to serve as the quasi-reference-counter-electrode (QRCE). As the micropipette approached the steel surface, a 30 s open circuit hold was performed allowing the microdroplets to stabilize and the open circuit potentials (OCP) were measured at the end of the hold. Thereafter, potentiodynamic (PD) polarization was performed at −0.25 VOCP to 0.4 VOCP with a 20 mV/s scanning rate. Linear fitting were performed on the Tafel plots over −0.25 VOCP to 0 VOCP, and over 0 VOCP to 0.25 VOCP, the corrosion current density was then extracted from the crossing point. Electrochemical impedance spectroscopy (EIS) was conducted at OCP with ± 10 mV stimulus potential over the frequency range of 10 kHz to 1 Hz. A programmable 3D motor with nanometer precision controlled the positioning of the micropipette to scan a grid-matrix that is superimposed on EBSD- and optical microscope-mapped areas. This produced hundreds of location-specific corrosion datasets within one scan, and allowed correlation of measured properties (e.g., corrosion rate, corrosion potential, and passive film thickness, etc.). A conductive carbon-fiber cloth was used to cover the whole SECCM apparatus as a Faraday cage. A Petri dish filled with cotton saturated with LiCl solution was placed next to the scanned sample to ensure a high relative humidity and prevent microdroplets from drying. All experiments were performed at room temperature (23 ± 2 °C) using reagent grade chemicals. All solutions were prepared using deionized (DI) water (>18 MΩ cm2).

Surface imaging

Topographical and polarized light images were acquired by a Vertical Scanning Interferometer (VSI, Zygo, NewView 7000). A 100× Mirau objectives (lateral resolution 84 nm) were used to measure surface height over the SECCM scanned areas ranging from 80 μm × 80 μm to 1 mm × 1 mm. The resolution in the z-direction is in the order of ±2 nm based on analysis of a NIST traceable step-height standard. The Gwyddion (ver. 2.55)54 software was used to analyze the topographical and polarized light images acquired by VSI. The SECCM scanned area were characterized immediately after each experiment to measure microdroplet sizes, and all current density and impedance were normalized by the surface area covered by microdroplets. In this study, the microdroplets are of diameters between 3 to 10 μm, rendering size measurement errors of less than 3%.

COMSOL simulation

The two-dimensional stress-strain distribution in the fractured sample was simulated by COMSOL Multiphysics using adaptive strain-stepping stationary solvers, triangular mesh elements (mesh opening of 0.005 mm2), and symmetrical continuity conditions. The simulation utilized a nonlinear elastoplastic model, wherein the input true stress–strain (σT–εT) relation was converted from the measured engineering stress–strain (σ-ε) curve following equations32:

Data availability

The analysis scripts and datasets generated during and/or analyzed over the course of the title study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

References

Cattant, F., Crusset, D. & Féron, D. Corrosion issues in nuclear industry today. Mater. Today 11, 32–37 (2008).

Gussev, M. N. & Leonard, K. J. In situ SEM-EBSD analysis of plastic deformation mechanisms in neutron-irradiated austenitic steel. J. Nucl. Mater. 517, 45–56 (2019).

Gussev, M. N., Field, K. G. & Busby, J. T. Strain-induced phase transformation at the surface of an AISI-304 stainless steel irradiated to 4.4 Dpa and deformed to 0.8% strain. J. Nucl. Mater. 446, 187–192 (2014).

Chen, X., Gussev, M., Balonis, M., Bauchy, M. & Sant, G. Emergence of micro-galvanic corrosion in plastically deformed austenitic stainless steels. Mater. Des. 2021, 109614.

Matsubara, N. et al. Research programs on SCC of cold-worked stainless steel in Japanese PWR N.P.P. France: N. p., 2011. Web.

Takakura, K., Nakata, K., Ando, M., Fujimoto, K. & Wachi, E. Lifetime evaluation for IASCC initiation of cold worked 316 stainless steel’s BFB in PWR primary water. Canada: N. p., 2007. Web.

Was, G. S. & Andresen, P. L. Irradiation-assisted stress-corrosion cracking in austenitic alloys. JOM 44, 8–13 (1992).

Shen, Y. F., Li, X. X., Sun, X., Wang, Y. D. & Zuo, L. Twinning and martensite in a 304 austenitic stainless steel. Mater. Sci. Eng. A 552, 514–522 (2012).

Liu, T., Reese, E. R., Ghamarian, I. & Marquis, E. A. Atom probe tomography characterization of ion and neutron irradiated alloy 800H. J. Nucl. Mater. 543, 152598 (2021).

Calcagnotto, M., Ponge, D., Demir, E. & Raabe, D. Orientation gradients and geometrically necessary dislocations in ultrafine grained dual-phase steels studied by 2D and 3D EBSD. Mater. Sci. Eng. A 527, 2738–2746 (2010).

McCafferty, E. Introduction to Corrosion Science (Springer, 2010).

Andresen, P. L. Stress corrosion cracking of current structural materials in commercial nuclear power plants. Corrosion 69, 1024–1038 (2013).

Suter, T. & Böhni, H. A new microelectrochemical method to study pit initiation on stainless steels. Electrochim. Acta 42, 3275–3280 (1997).

Grandy, L. & Mauzeroll, J. Localising the electrochemistry of corrosion fatigue. Curr. Opin. Colloid Interface Sci. 61, 101628 (2022).

Bard, A. J. & Mirkin, M. V. Scanning Electrochemical Microscopy (CRC Press, 2012).

Gateman, S. M. et al. Using macro and micro electrochemical methods to understand the corrosion behavior of stainless steel thermal spray coatings. Npj Mater. Degrad. 3, 1–9 (2019).

Yule, L. C. et al. Nanoscale electrochemical visualization of grain-dependent anodic iron dissolution from low carbon steel. Electrochim. Acta 332, 135267 (2020).

Yule, L. C. et al. Nanoscale active sites for the hydrogen evolution reaction on low carbon steel. J. Phys. Chem. C 123, 24146–24155 (2019).

Sidane, D. et al. Electrochemical characterization of a mechanically stressed passive layer. Electrochem. Commun. 13, 1361–1364 (2011).

Sun, P., Liu, Z., Yu, H. & Mirkin, M. V. Effect of mechanical stress on the kinetics of heterogeneous electron transfer. Langmuir 24, 9941–9944 (2008).

Yazdanpanah, A. et al. Revealing the stress corrosion cracking initiation mechanism of Alloy 718 prepared by laser powder bed fusion assessed by microcapillary method. Corros. Sci. 208, 110642 (2022).

Yazdanpanah, A., Pezzato, L. & Dabalà, M. Stress corrosion cracking of AISI 304 under chromium variation within the standard limits: failure analysis implementing microcapillary method. Eng. Fail. Anal. 142, 106797 (2022).

Was, G. S. Fundamentals of Radiation Materials Science: Metals and Alloys (Springer, 2016).

Deng, P. et al. Effect of irradiation on corrosion of 304 nuclear grade stainless steel in simulated PWR primary water. Corros. Sci. 127, 91–100 (2017).

Birtcher, R. C., Kirk, M. A., Furuya, K., Lumpkin, G. R. & Ruault, M. O. In situ transmission electron microscopy investigation. Radiat. Eff. J. Mater. Res. 20, 1654–1683 (2005).

Kaoumi, D. & Liu, J. Deformation induced martensitic transformation in 304 austenitic stainless steel: in-situ vs. ex-situ transmission electron microscopy characterization. Mater. Sci. Eng. A 715, 73–82 (2018).

Hirst, Charles A. et al. Revealing hidden defects through stored energy measurements of radiation damage. Sci. Adv. 8, eabn2733 (2022).

El-Tahawy, M. et al. Stored energy in ultrafine-grained 316l stainless steel processed by high-pressure torsion. J. Mater. Res. Technol. 6, 339–347 (2017).

Naghizadeh, M. & Mirzadeh, H. Microstructural evolutions during annealing of plastically deformed AISI 304 austenitic stainless steel: martensite reversion, grain refinement, recrystallization, and grain growth. Metall. Mater. Trans. A 47, 4210–4216 (2016).

Wang, H. et al. Dislocation structure evolution in 304L stainless steel and weld joint during cyclic plastic deformation. Mater. Sci. Eng. A 690, 16–31 (2017).

Sohrabi, M. J., Naghizadeh, M. & Mirzadeh, H. Deformation-induced martensite in austenitic stainless steels: a review. Arch. Civ. Mech. Eng. 20, 1–24 (2020).

Hertzberg, R. W., Vinci, R. P. & Hertzberg, J. L. Deformation and Fracture Mechanics of Engineering Materials (John Wiley & Sons, 2020).

Czerwinski, F. et al. The edge-cracking of AISI 304 stainless steel during hot-rolling. J. Mater. Sci. 34, 4727–4735 (1999).

Xu, Y., Jing, H., Xu, L., Han, Y. & Zhao, L. Effect of δ-ferrite on stress corrosion cracking of CF8A austenitic stainless steels in a simulated pressurised water reactor environment. J. Mater. Res. Technol. 8, 6420–6426 (2019).

Yi, Y., Cho, P., Al Zaabi, A., Addad, Y. & Jang, C. Potentiodynamic polarization behaviour of AISI type 316 stainless steel in NaCl solution. Corros. Sci. 74, 92–97 (2013).

Bakhsheshi-Rad, H. R. et al. Cold deformation and heat treatment influence on the microstructures and corrosion behavior of AISI 304 stainless steel. Can. Metall. Q. 52, 449–457 (2013).

Tao, H., Ding, M., Shen, C. & Zhang, L. Inconsistent evolvement of micro-structures and corrosion behaviors in cold/warm deformed austenitic stainless steel. Mater. Res. Express 9, 096520 (2022).

Gussev, M. N., Busby, J. T., Byun, T. S. & Parish, C. M. Twinning and martensitic transformations in nickel-enriched 304 austenitic steel during tensile and indentation deformations. Mater. Sci. Eng. A 588, 299–307 (2013).

Raiman, S. S., Bartels, D. M. & Was, G. S. Radiolysis driven changes to oxide stability during irradiation-corrosion of 316L stainless steel in high temperature water. J. Nucl. Mater. 493, 40–52 (2017).

Lozano-Perez, S. et al. Multi-scale characterization of stress corrosion cracking of cold-worked stainless steels and the influence of Cr content. Acta Mater. 57, 5361–5381 (2009).

Deng, P., Peng, Q., Han, E.-H. & Ke, W. Effect of the amount of cold work on corrosion of type 304 nuclear grade stainless steel in high-temperature water. Corrosion 73, 1237–1249 (2017).

Wenman, M. R., Trethewey, K. R., Jarman, S. E. & Chard-Tuckey, P. R. A finite-element computational model of chloride-induced transgranular stress-corrosion cracking of austenitic stainless steel. Acta Mater. 56, 4125–4136 (2008).

Hamilton, M. L. et al. Mechanical properties and fracture behavior of 20% cold-worked 316 stainless steel irradiated to very high neutron exposures. Influence of Radiation on Material Properties: 13th International Symposium (Part II). (ASTM International, 1987).

Cui, T. et al. Effects of composition and microstructure on oxidation and stress corrosion cracking susceptibility of stainless steel claddings in hydrogenated PWR. Prim. Water J. Nucl. Mater. 553, 153057 (2021).

Taller, S. et al. Multiple ion beam irradiation for the study of radiation damage in materials. Nucl. Instrum. Methods Phys. Res. B: Beam Interact. Mater. 412, 1–10 (2017).

Was, G. S., Farkas, D. & Robertson, I. M. Micromechanics of dislocation channeling in intergranular stress corrosion crack nucleation. Curr. Opin. Solid State Mater. Sci. 16, 134–142 (2012).

Johnson, D. C., Kuhr, B., Farkas, D. & Was, G. S. Quantitative linkage between the stress at dislocation channel–grain boundary interaction sites and irradiation assisted stress corrosion crack initiation. Acta Mater. 170, 166–175 (2019).

Chimi, Y. et al. Correlation between locally deformed structure and oxide film properties in austenitic stainless steel irradiated with neutrons. J. Nucl. Mater. 475, 71–80 (2016).

Deng, P., Peng, Q., Han, E.-H., Ke, W. & Sun, C. Proton irradiation assisted localized corrosion and stress corrosion cracking in 304 nuclear grade stainless steel in simulated primary PWR water. J. Mater. Sci. Technol. 65, 61–71 (2021).

Gussev, M. N., Howard, R. H., Terrani, K. A. & Field, K. G. Sub-size tensile specimen design for in-reactor irradiation and post-irradiation testing. Nucl. Eng. Des. 320, 298–308 (2017).

Gussev, M. et al. Role of scale factor during tensile testing of small specimens. Small Specimen Test Techniques: 6th Volume. (ASTM International, 2015).

Ziegler, J. F. SRIM-2003. Nucl. Instrum. Methods Phys. Res. B: Beam Interact. Mater. 219, 1027–1036 (2004).

Fruzzetti, K. Pressurized Water Reactor Primary Water Chemistry Guidelines Revision 6 (EPRI, 2007).

Nečas, D. & Klapetek, P. Gwyddion: an open-source software for SPM data analysis. Open Phys. 10, 181–188 (2012).

Acknowledgements

The authors acknowledge financial support for this research provided by the U.S. Department of Energy’s Light Water Reactor Sustainability (LWRS) Program through the Oak Ridge National Laboratory operated by UT-Battelle LLC (Contract #: 4000154999) and The National Science Foundation (CAREER Award: 1253269, CMMI: 1401533). The contents of this paper reflect the views and opinions of the authors who are responsible for the accuracy of data presented. This research was carried out in the Laboratory for the Chemistry of Construction Materials (LC2) and the Electron Microscopy Core Facility at UCLA, and the Oak Ridge National Laboratory (ORNL). The ion irradiation was performed at the Center for Integrated Nanotechnologies, an Office of Science User Facility operated for the U.S. Department of Energy (DOE) Office of Science. Los Alamos National Laboratory, an affirmative action equal opportunity employer, is managed by Triad National Security, LLC for the U.S. Department of Energy’s NNSA, under contract 89233218CNA000001. As such, the authors gratefully acknowledge the support that has made these facilities and their operations possible. This manuscript has been authored by UT-Battelle, LLC under Contract No. DE-AC05-00OR22725 with the United States Department of Energy. The United States Government retains and the publisher, by accepting the article for publication, acknowledges that the United States Government retains a non-exclusive, paid-up, irrevocable, worldwide license to publish or reproduce the published form of this manuscript, or allow others to do so, for United States Government purposes. The Department of Energy will provide public access to these results of federally sponsored research in accordance with the Department of Energy Public Access Plan (http://energy.gov/downloads/doe-public-access-plan).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Xin Chen: Writing—original draft, Methodology, Formal analysis, Data curation, Investigation. Marta Pozuelo: Writing—original draft, Data analysis, Conceptualization. Maxim Gussev: Writing—original draft, Methodology, Formal analysis, Data curation, Investigation. Matthew Chancey: Methodology, Formal analysis, Data curation. Yongqiang Wang: Writing—original draft, Methodology, Formal analysis, Data curation, Investigation. Magdalena Balonis: Writing—original draft, Data curation, Conceptualization. Mathieu Bauchy: Writing—original draft, Data curation, Conceptualization. Gaurav Sant: Writing—original draft, Conceptualization, Supervision.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing Interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Chen, X., Pozuelo, M., Gussev, M. et al. Microstructurally resolved electrochemical evolution of mechanical- and irradiation-induced damage in nuclear alloys. npj Mater Degrad 8, 84 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41529-024-00500-7

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41529-024-00500-7

This article is cited by

-

Prediction of coating degradation based on “Environmental Factors–Physical Property–Corrosion Failure” two-stage machine learning

npj Materials Degradation (2025)