Abstract

Physical and chemical properties of passivating alteration gels formed on alumino-boro-silicate glasses of interest for nuclear waste containment are reported. Opposite effects of B and Al on the gel’s propensity to restructure and become passivating were observed. Boron, primarily forming Si‒O‒B bonds, fragments and weakens the silicate network if its concentration is higher than a critical value, leading to the formation of pores and Si‒OH terminations as it leaches out. The greater the number of the silanol groups, the more effective the recondensation (Si‒OH + Si‒OH ⇌ Si‒O‒Si + H2O) is, leading to reduction of pore connectivity; this facilitates passivation and thus lowers the glass alteration rate. Conversely, Al has a slowing effect on this reorganization dynamics. This work provides better insight into the role of elements in the glass alteration kinetics.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Upon contact with water, alumino-borosilicate glasses can develop amorphous, porous, and hydrated layers called gels, which may act as a barrier to the further transport of water and species released from glass1. This ‘protective’ or ‘passivating’ role depends on the composition of the glass as well as on the alteration conditions, such as temperature, pH, and the composition of the solution. That is why it is not easy to generalize the phenomenon of passivation or even to quantify it2,3,4. An additional difficulty is that there is not a unique mechanism limiting the glass dissolution rate in silica-saturated conditions2. Moreover, to date, even advanced glass durability models such as GRAAL5, GM20016, Ma’s model7 or Monte Carlo models8,9 could predict a limited number of gel properties, under specific conditions and with the use of empirical parameters. An in-depth understanding of the convoluted mechanisms at work is still needed to improve predictions. This motivates mechanistic studies on borosilicate glass alteration under conditions relevant to geological disposal.

In this study, we characterized gels formed under silica-saturated conditions (at 90 °C and pH 9) for a series of six borosilicate glasses studied in the sister article10. The chemical compositions of the gels were determined by ToF-SIMS. Their thicknesses were determined by several methods: transmission electron microscopy (TEM), crater measurement after time-of-flight secondary ion mass spectrometry (ToF-SIMS) analysis, spectroscopic ellipsometry (SE), and analysis of tracer elements in solution. Their porosity was determined by thermogravimetric analyses (TGA) and from ToF-SIMS profiles. A relationship between glass composition and characteristics of gel is proposed. Findings reveal opposite effects of B and Al on gel maturation and residual alteration rates.

Results

Gel composition

The composition of the gels was studied through (i) core alteration of glass powder monitored by solution analysis and (ii) monolith alteration studied by ToF-SIMS depth profiling.

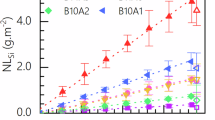

For the first method, glass powders underwent a first stage at pH 5 in a solution close to saturation with respect to amorphous SiO2 at 90 °C to favor the release of mobile elements, followed by a 1-month stage at pH 9 to allow gel maturation under the same conditions as those used for the kinetic studies (Table 1). Figure 1 depicts the fraction of altered glass calculated from the concentrations of dissolved elements. For each glass, the leaching of B and Na occurs preferentially to that of other elements. According to B release, it is observed that glasses B11A3, B14A3, B11A6 and B10A2 are core-altered with a fraction of altered glass ranging between 80% and 100%. However, core alteration is not achieved for B6A4 and B10A1, for which the alteration exhibits a plateau around 50% indicating a very slow alteration rate. For all glasses, Si and Al are highly retained in the gels, but Ca retention appears to be dependent on the composition. It varies from 60% for B10A2 to 100% for B11A6. Comparing these results to those obtained at pH = 9 using powder (results discussed in the companion paper10), where Ca is entirely retained in the gel regardless of the composition of the glass, it appears that the lower retention noted in the present experiment is likely due to the first stage at pH 5 (which was selected to accelerate the reaction). Indeed, as the pH decreases, the solubility of Ca in solution increases and its retention in the gel decreases11. Another difference related to the pH change between the two experiments is the behavior of B within B6A4. As mentioned in Part I of this study10, at pH = 9, B is largely retained in the gel. This is still the case but with a lower extent at pH = 5.

In the second method, alteration of glass monoliths were conducted in a solution close to saturation with respect to amorphous 29SiO2 at pH = 9 and 90 °C. The duration of alteration depended on the composition of the glasses, with the aim of avoiding the formation of a too thick gel possibly subject to delamination. Thus, alteration durations were 5 days for B14A3, 13 days for B10A1, and 30 days for B6A4, B10A2, B11A6 and B11A3. ToF-SIMS profiles are depicted in Fig. 2. Concentrations of B, Na, Ca and Si were estimated after normalization of their corresponding intensities with respect to their mean intensity in the pristine glass (Ii/Ii,glass) and to the same ratio for aluminum (IAl/IAl,glass), as Al is considered to be entirely retained in the gel according to experiments conducted on powders. For five out of six glasses (B10A1, B10A2, B11A6, B11A3, B14A3), a nearly total depletion in B and Na is observed at depths varying depending on the glass composition. From the B profiles, it is thus possible to determine the thickness of the gel, with the midpoint depth of the B gradient indicating the interface between the gel and the pristine glass as explained in former articles dedicated to this analytical technique applied to glass corrosion12,13. However, glass B6A4 is an exception. Comparing the profiles of B, Na, and H, water species appears to penetrate to approximately 46 nm. The H profile can indeed be correlated with that of Na, which exhibits decreasing depletion with the thickness of altered glass. Nevertheless, unlike the other studied glasses, the leaching of B from glass B6A4 is not congruent with that of Na and occurs only within the top-most 2 nm. Thus, it seems that glass B6A4 forms a B-depleted gel, if any, only over a few nm, and water alteration primarily leads to the formation of a Na-depleted hydrated glass layer. This behavior is somewhat similar to the Na-leaching from a soda lime silica glass where dissociation of the network is negligible14.

Relative concentrations of glass elements are obtained by a double normalization (Ii/IAl)/(Ii0/IAl0), whereas the relative concentration of H underwent a simple normalization to the mean intensity in the pristine glass. For Si, only 28Si profiles are displayed on the plots (29Si profiles are shown in Fig. 3). The alteration time was 5 d (B14A3), 13 d (B10A1) and 30 d (B6A4, B10A2, B11A6, B11A3). The interface between the gel and the pristine glass is placed at the depth corresponding to the half intensity of B. The hydrated glass, characterized by the depletion of Na only, is visible only for B6A4.

The determination of the interface between hydrated glass and pristine glass raises questions. Typically, for B profiles, it is generally considered that the interface is located at the midpoint of the concentration gradient to account for possible interface roughness12,13,15. However, the observed Na profile during the alteration of glass B6A4 exhibits a very different shape with a broad gradient. In this case, the gradient is indicative of incomplete sodium depletion, which occurs through ion-exchange driven by water penetration into the glass16,17,18. Consequently, placing the interface between pristine glass and hydrated glass becomes more challenging since the midpoint of the gradient is not indicative of the interface. Thus, it is considered that the interface is located at the end of the sodium and hydrogen gradients. The different interfaces determined, namely the gel/pristine glass interface, gel/hydrated glass interface and hydrated glass/pristine glass interface, are indicated on Fig. 2 by dashed lines. Beyond these considerations, this example illustrates that, on one hand, the mechanisms of ion exchange and B hydrolysis are not necessarily correlated, and on the other hand, ion exchange is faster than B hydrolysis.

Regarding the behavior of Ca, the ToF-SIMS profiles indicate that it is retained in the gel of all studied glasses, except for glass B10A1, where approximately 50% depletion of calcium is observed.

For four out of six glasses (B6A4, B11A6, B11A3, B14A3), the silicon profile remains constant with depth. Only B10A1 and B10A2 show silicon depletion, which can be correlated with an enrichment in 29Si as shown in Fig. 3. For glass B10A1, the entire thickness of the gel exhibits a high enrichment in 29Si. It can be inferred that this gel forms through a dissolution/reprecipitation mechanism from the silicon present in the alteration solution labeled with 29Si. For glass B10A2, approximately 40 nm out of 120 nm of the gel show an enrichment in 29Si. This partial enrichment suggests that the outer part of the gel forms through dissolution/reprecipitation whereas the inner part underwent partial hydrolysis/condensation reaction with no exchange with Si(aq), as discussed in former articles19,20. For the other glasses, enrichment in 29Si is observed only on a few nm at the surface of the gel, which may indicate exchange between Si atoms as well as deposition on the glass surface or easily accessible large pores.

The duration of the experiments was 5 d (B14A3), 13 d (B10A1) or 30 d (B6A4, B10A2, B11A6, B11A3). The interface between the pristine glass and the gel is represented by the vertical dashed line and is determined at the midpoint of the gradient of the B profile. The natural isotopic abundance of Si (Si nat. ab.) is represented by the horizontal dashed red line. Relative concentrations of B and Na are obtained by a double normalization (Ii/IAl)/(Ii0/IAl0).

Gel thickness

Comparison of the gel thicknesses formed on monoliths determined by ToF-SIMS, spectroscopic ellipsometry (SE), and TEM is provided in Table 2. The thicknesses measured by ToF-SIMS and SE are in reasonable agreement, with differences ≤30% between the two techniques. Gel thickness on B6A4 sample could not be determined with SE because the refractive index contrast was not large enough (which is understandable based on the depth profiles shown in Fig. 2 for this glass). The thickness determined with ToF-SIMS could be simply fitted with a ‘surface roughness’ layer in the optical model constructed for SE data analysis. TEM imaging on FIB lamellae was performed for glasses B10A1 and B10A2 (Fig. 4).

Equivalent boron thicknesses, ETh(B), were determined from solution analyses. For the monolith alteration experiments, the calculated equivalent thicknesses were larger than those measured by ToF-SIMS, SE, and TEM. The fact that aluminum solution concentrations were significant enough to be measured by ICP-OES implies that Al concentration in the solutions was larger than what it would have been if Al only came from leaching of the gel layers. This is interpreted as a non-negligible portion of the glass network has dissolved despite the pre-saturation of the solution with silica. Therefore, to determine the gel thickness, the equivalent aluminum thickness (ETh(Al)) is subtracted from the equivalent boron thickness (ETh(B)). The difference between the gel thicknesses measured by ToF-SIMS and those calculated from ICP measurements (ETh(B) - ETh(Al)) is small ( < 20%), except for glass B6A4 which has a very thin gel layer, leading to larger uncertainties in measured data. Overall, the implemented techniques are in good agreement for thicknesses of the alteration gels formed on the monoliths.

Gel porosity

Gel porosity was determined by two methods: thermogravimetric analyses (TGA) and ToF-SIMS. For TGA analysis, the gel powders were placed at 98% relative humidity imposed by a saturated solution of K2SO4 for 24 h to rehydrate all the available porosity. The hydrated powders were then heated to 450 °C with a ramp of 10 °C/min followed by a 10 min hold. The mass loss associated with this heating corresponds to the amount of water present within the gels and thus allows the estimation of the porosity occupied by water.

Porosity can also be calculated from ToF-SIMS profiles, following a method described in a previous study21. In brief, it is assumed that i) the porosity is equal to the free volume corresponding to the release of the mobile elements, namely B, Na, and Ca, and, ii) the gel occupies the same volume as that initially occupied by altered glass (isovolumic hypothesis). The fraction of released elements was calculated according to the profiles shown in Fig. 2. Knowing that, the free volume was calculated at a given depth according to the volume occupied by each of the atoms B[3], B[4], Na, and Ca, where the ionic radius r is provided in Table 3.

Table 4 summarizes the porosities determined by the two methods. Firstly, from porosity calculations obtained from ToF-SIMS profiles, it is noted that across the entire glass series between 80% and 90% of the porosity is created by the departure of B atoms. Secondly, for four out of six glasses (B10A2, B11A6, B11A3, and B14A3), the difference in porosity between the TGA and ToF-SIMS measurements is less than 15%, which is deemed acceptable. This result suggests that the porosity within the gels formed by in situ reorganization of the silicate network are similar for powders and monoliths even though the alteration procedure to prepare the gels was slightly different.

However, two glasses show significant differences in porosity between the two analyses. Glass B10A1 exhibits a porosity of 41.5% on monoliths and 12.7% on powders. The calculation of porosity from the ToF-SIMS profiles for this glass raises questions because, as stated earlier, its gel forms through dissolution/reprecipitation. The assumptions of total aluminum retention and the formation of an isovolumetric gel are therefore more questionable. Nonetheless, the large porosity measured on the monoliths seems consistent with the TEM image presented in Fig. 4, where large and numerous pores are visible. However, the alteration kinetics obtained on glass B10A1 and represented in Fig. 1 suggest the formation of a very passivating gel during powder alteration due to the presence of a plateau at 50% alteration. This result is consistent with the formation of low porosity measured by TGA, which is tied to a fast reorganization of the gel. It thus appears that for B10A1 only, the behavior of powder significantly differs from that of monolith. This difference can be explained by the reactive surface area involved in the two experiments. With powders, this surface area is much larger, so it is possible that the dissolution of the silicate network leads to local supersaturation of the fluid near the glass surface, which are less significant on monoliths. Therefore the gel may precipitate faster on powder.

Finally, glass B6A4 also exhibits significant differences in porosity between the TGA and ToF-SIMS analyses. However, the glass powder used for the alteration of glass B6A4 being very small (1 µm - 2 µm instead of 20 –40 µm for the other glasses), it seems likely that the TGA measurement is not accurate because such small grains are likely to create a larger amount of inter-granular water than the other powders. This amount of external water thus distorts the TGA measurement, for which only the pore water is to be measured, and can explain such a large discrepancy between the two analysis techniques. For this reason, the value obtained by TGA is discarded.

Considering that 80% to 90% of the porosity is due to the departure of B, it is inherently linked to the B content of the glass: the higher it is, the higher the porosity of the gel. According to ToF-SIMS data, porosity varies between 12% and 47% across the entire glass series. The reasons of this difference along with some implication on the passivation properties of the gel will be discussed further.

Transport properties of the gels studied with post mortem isotopic tracing experiments

To study the ion diffusivity within gels, tracing experiments followed by ToF-SIMS depth profiling were conducted. Altered monoliths were exposed to a tracing solution enriched with H218O and methylene blue to investigate how water molecules behave within the gel and how a bigger (~1 nm) and inert molecule such as methylene blue diffuses in the porous network. These tracing experiments were performed at room temperature to prevent further gel or glass alteration, and for different durations (3 min, 24 h, and 21 days). For each tracing experiment, a profile was acquired for negative ions. The analyses were performed in cryogenic mode to avoid the evaporation of pore water during analysis. The 18O/16O ratio provides quantitative data about 18O incorporation in the gel, whereas analysis of S provides qualitative data (mainly the depth of penetration) about diffusion of dye.

The penetration of methylene blue, with S as the tracer element, is illustrated in Fig. 5, for a tracing duration of 24 h. The S profile is compared to that of B and the 29Si/28Si ratio within the gel. The main observation is that the penetration of methylene blue correlates quite well with the enrichment of 29Si, although a difference in front position of about 10 nm is noticed for B11A6. This correlation between S and 29Si supports the idea that the 29Si enrichment is due to deposition of dissolved silica within easily accessible large pores. For B10A1, the penetration of methylene blue and the enrichment of 29Si occur throughout the entire alteration gel. This result is consistent with TEM images showing large pores in the whole gel (Fig. 4).

To study the behavior of tagged water molecules within the gels, first, a maximum pore filling capacity is calculated based on the porosity of the gels. By assuming that the entire porosity is filled by the tracing solution and knowing its isotopic enrichment in 18O, it is possible to determine a theoretical 18O/16O ratio corresponding to this maximum. This ratio can be compared to that determined by ToF-SIMS. The profiles obtained are shown in Fig. 6 for the different contact durations with the tracing solution. Note that the calculation cannot be performed for glass B10A1 because the porosity of the gel is not known.

Measured isotopic ratios (dark full symbols) are compared to theoretical ratios (light empty symbols) calculated if the entire porosity is filled by the tracing solution. The case of B10A1 is not shown on this plot as the porosity of this gel is not known. Note that, although it is not visible on the plots, the natural abundance was recorded (18O/16O = 0.002) in the area corresponding to pristine glass.

For all the glasses in the series, the 18O/16O ratio increases with the contact duration with the tracing solution, indicating that the proportion of water from the tracing solution penetrating the gel increases over time. This was also noticed in a previous study with ISG22. Except for B6A4, where the gel thickness is very low, the 18O/16O ratio within the gel appears as a plateau over most of the gel thickness, followed by a peak representing 18O accumulation at the gel/intact glass interface. This interface seems more reactive than the rest of the gel, which could be due to the presence of boron facilitating exchanges with the oxygen atoms from water12.

Except for B6A4, the 18O/16O ratio is far from the maximum calculated ratio, which assumes that the entire gel porosity is filled by the tracing solution. This suggests that the gels primarily consist of closed pores barely inaccessible to the tracing solution or that the exchange between oxygen atoms is kinetically slow.

Discussion

The in-depth characterization of gels performed in this study provides insights into their formation mechanisms and properties (composition, porosity, and diffusivity). The main question we will address in this section is whether it is possible to establish a link between the composition of the glasses and the passivating properties of the gels formed under silica saturation conditions.

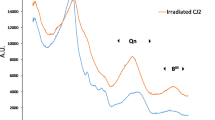

29Si/28Si ratios in the gels show that B10A1 glass is the only glass of the series that formed its altered layer through the dissolution/reprecipitation mechanism. The entire gel has a 29Si/28Si close to that of the solution ( ~ 4 vs 8.25; natural abundance is 0.05) (Fig. 3). It is therefore evident that the gel of this glass was formed by the precipitation of silica supplied by the bulk solution and silica supplied by the glass. For this gel, the estimation of porosity from the ToF-SIMS profiles was incorrect. The TGA measurement (determined on powder) indicates a low value (12.7%), which seems consistent with a significant decrease in the alteration rate of this glass (Table 4 sister paper). The fact that this glass forms a gel by precipitation is related to its low Al content. In a previous study comparing the alterations of CJ1 glass (SiO2, B2O3, Na2O) and CJ2 glass (SiO2, B2O3, Na2O, Al2O3), two glasses with same Si/B and Si/Na ratio, we showed that the glass without Al, CJ1, formed a gel by precipitation unlike the glass with Al, CJ2, whose gel formed by in situ reorganization of the aluminosilicate network inherited from the glass19. Al makes the silicate network less soluble and as a result slows down its reorganization23. The CJ2 glass contains 2.1 mol% of Al, which is three times more than the B10A1 glass in this study. Therefore, it seems that for four-oxide glasses, the threshold for changing the gel formation mechanism lies at a molar Si/Al ratio between 24 (B10A1) and 8 (CJ2). Further studies are needed to clarify the value of this threshold.

B14A3, B11A6, B11A3, and B6A4 exhibit very different alteration behaviors but share the common point of forming gels primarily through in situ reorganization of the silicate network after the departure of soluble species (B, Na). Enrichment of 29Si is only noticed in the first few nanometers at the interface with the solution. B10A2 glass shows an intermediate behavior, in that about the outer half of the gel is enriched in 29Si (Fig. 3). This intermediate case is not surprising. In Gin et al. 202019, it was shown that a glass could exhibit both modes of gel formation under the same conditions as the present study (90 °C, pH 9, silica saturated solution). Other intermediate cases have been noted in the literature24. However, the reason for such a change in mechanism remains to be understood.

Excluding B10A1 glass, as its gel formed by precipitation and thus has characteristics that depend more on the solution composition than on the glass composition itself, we can consider the remaining five glasses and attempt to establish links between their composition and alteration behavior.

Given that B dissolution is responsible for most of the gel porosity, as shown in this study and in a previous one21, let us examine the link between B content in the glass and the gel porosity. Figure 7 shows a positive correlation between these two variables, with high B content glasses forming more porous gels. Intuitively, one might expect that the most porous gels would allow faster exchanges with the solution and therefore have the highest rates of 18O-labeled water filling.

Figure 8 shows the gel thickness and the accessibility to the pores (determined from the pore filling capacity after 21 days of tracing with H218O) as a function of the boron content in the glass. It appears that the more B the glass contains, the thicker the gel, and the lower the fraction of pores filled by H218O after 21 days of tracing. Thus, there is an anti-correlation between total porosity and pore accessibility. To explain this result, it is important to remember that the gel is a dynamic structure22, and its reorganization depends on the content of soluble elements in the glass. Indeed, the departure of B, Na, and Ca creates silanol bonds (Si‒OH) which may condense to form siloxane (Si‒O‒Si) bonds18. It is through these condensation reactions that the number of easily accessible pores decrease and the transport of aqueous species (water and solutes) slow down through steric effects18 and hydrogen bond interactions with the surfaces4.

Evolution of two characteristics of the gel as a function of boron content in the glass: fraction of the gel porosity at equilibrium with the tracing solution after 21 days on the left Y axis; thickness of the gel that underwent tracing, determined from crater measurement following the ToF-SIMS analysis on the right Y axis.

In the sister article, to quantify the passivating nature of the gel, parameter τ, which is the characteristic time of transition to the residual regime, was calculated for each glass. The smaller the τ parameter, the more quickly the passivating gel forms. It appears that τ decreases with increasing B content in the glass (Fig. 9a). This means that the more B in the glass, the more silanol bonds are formed, leading to more condensation reactions in the gel. As a result, the gel becomes passivating faster. It is also shown that the earlier the passivating gel forms, the lower the exchange with the solution (Fig. 9b).

Thus, this study suggests that B has a dual effect on the durability of silicate glasses. On one hand, it weakens the silicate network by fragmenting it through the creation of Si-O-B bonds25, which are easier to hydrolyze than Si‒O‒Si bonds (Fig. 3 of the sister paper10). This results in gel thickness increasing with the B content in the glass. However, this phenomenon is strongly mitigated by a much faster and more efficient gel maturation in B-rich glasses. Contrary to what one might expect, the passivating nature of a gel is not correlated with its porosity but rather with the dynamic reorganization of the porous network, which is facilitated by B.

The literature has already highlighted the role of elements like Zr26,27,28 or Al29 on the dynamic reorganization of the gel and its consequences on the glass alteration kinetics. Comparing glasses B11A6 and B11A3, which only differ in their Si/Al ratio (3 vs. 5), we observe that at equal porosity (as expected since they have nearly the same B content), the Al-rich glass is less passivating (larger τ, and consequently a higher residual rate) and its porosity is more accessible (pore filling rate with 18O-labeled water is 25% compared to 12% for the less aluminous glass).

In conclusion, this study confirms the complexity of the effects of different oxides in nuclear glasses on the dissolution kinetics. Al was shown to stiffen the vitreous network and slow down its reorganization dynamics. It is proposed that for 4-5 oxide aluminoborosilicate glasses, a low aluminum content leads to gel formation by silica reprecipitation instead of in-situ reorganization of the silicate network, the glassy network being insufficiently rigidified by the low Al content. Also, the negative impact of B on glass durability, known for a long time30,31, must be reconsidered given its ability to facilitate passivation. The richer the glass is in B (up to a certain limit that was not investigated in this study), the faster the silicate network of the gel can reorganize, resulting in reduced accessibility of aqueous species to the porous network. Another striking result is that the way water diffuses in the gels is qualitatively similar whatever the glass composition is (a plateau at short times, with the value increasing over time). This suggests that the pores are interconnected (except for glass B6A4, for which weak bonds do not form a continuous subnetwork within the aluminosilicate network). One can imagine that water diffuses more rapidly in the center of the pores and more slowly near the interfaces, as shown by the atomistic simulations22.

The very concept of chemical durability must be contextualized, as it depends on both the glass composition and the alteration conditions (temperature, pH, solution composition), as well as the envisaged duration, given that the alteration process is dynamic.

Methods

Glass composition and preparation

Six glasses of five oxides (SiO2-B2O3-Al2O3-Na2O-CaO) were defined in two series for which the ratio of soluble to insoluble elements (S/I) or the Si/Al ratio were modified. Table 5 shows the compositions of the selected glasses and the S/I and Si/Al ratios. The names of the glasses (BxAy) are based on the molar elemental percentages of boron (x) and aluminum (y). Details of how to calculate the ratio of soluble to insoluble elements can be found elsewhere10, but to summarize, the elements considered soluble are boron, and calcium and sodium if not charge-compensator for aluminum, and the insoluble elements are silicon and aluminum.

The glasses were produced from oxide and carbonate powders using a classical melt-quench protocol, with a second fusion to ensure glass homogeneity. Powdered and monolithic samples were then produced from the glass obtained for the alteration experiments. Details of these processes can be found in the companion paper10. Six-sided polished monoliths measuring 25 x 25 x 1 mm3 were prepared, and 20 µm–40 µm powders were selected by grinding, sieving and sedimentation cleaning in acetone and ethanol. For core alteration experiments, 1 µm–2 µm powders were prepared specifically for the particularly durable B6A4 glass.

Core alteration experiments

Core alteration experiments were carried out in PFA reactors containing 1000 mL or 500 mL solution. Experiment were conducted at 90 °C and pH = 5 in a pre-saturated amorphous silica solution for 90 days. Note that, according to previous work on ISG2, it is expected that the gel formed at pH 5 in silica saturated conditions is representative of that formed in alkaline conditions, at least before maturation. To prepare the leaching solution, high purity silica gel (Sigma Aldrich (200 µm – 425 µm) mesh particle size) was dissolved at 90 °C pH 9.5 (adjusted with high purity 1 M LiOH solution) for a few days and the pH was then adjusted to 5 by adding diluted Normapur HNO3 (VWR Chemicals). Silicon concentrations over time are shown in Figure S1. A mass of 1 g of glass powder with a grain size of 20 µm – 40 µm (or 1 µm to 2 µm for the particularly durable B6A4 glass) was introduced into the alteration solution. The pH of the solution was regularly monitored and adjusted by adding 1 M HNO3. Regular samples of the alteration solution were taken, filtered at 0.2 µm to avoid the presence of powder grains in the sampled solutions, and analyzed by UV-visible spectrophotometry for boron and ICP-OES for all the elements in the glass composition. Once core alteration has been reached, i.e. when all the boron in the glass has been released into solution, or when alteration has reached a plateau, the pH of the solution was raised to 9 for 40 more days. The powders were then recovered by Büchner filtration, rinsed and oven-dried at 50 °C for at least one night.

Gel formation on monoliths

Gel formation experiments were carried out in 50 mL PFA reactors. Four 25 x 25 x 1 mm3 monoliths were placed in 40 mL of 29Si pre-saturated solution ([Si] = 291.12 mg.L-1) at pH = 9 and 90 °C. Alteration time varied between 5 and 30 days, depending on the glass (B14A3: 5 days; B10A1: 13 days; B6A4, B10A2, B11A6, B11A3: 30 days), to avoid the formation of an excessively thick gel that would present a risk of delamination. The monoliths were then rinsed and dried, and a sample of the solution was taken to compare the content of elements in solution by ICP-OES with gel thickness measurements. Thickness measurements were carried out using several techniques: ToF-SIMS, TEM, SE. In addition, the altered monoliths were immersed in a tracing solution composed of 500 µL of H218O (18O/16O = 7) and 75 µL of methylene blue to study the accessibility of the gel by these molecules. Durations of immersion were 3 min, 24 h and 21 days at room temperature.

Solution analyses

The sampled solutions were analyzed using a Thermo Scientific ICAP 6300 Duo ICP-OES to determine the concentrations of the various elements released during glass alteration. After correcting the concentrations with their respective dilution factors, the equivalent thicknesses ETh (Eq. 1) were calculated for each times from the following equation:

with ci the concentration of element i in solution, xi the mass fraction of element i in the pristine glass, S the reactive surface area of the glass, V the volume of alteration solution and ρ the density of the glass.

The fractions of altered glass were calculated from the following equation:

with ci(t) the concentration of element i in solution at time t, xi the mass fraction of element i in the glass, V(t) the volume of solution at time t and VS the volume of the j-th sampling and m the mass of glass powder in the reactor.

TOF-SIMS

Time-of-flight secondary ion mass spectrometry (ToF-SIMS) analyses were carried out by TESCAN Analytics in Fuveau (France) on an IONTOF TOF 5. For positive ion profiles, the surface was sputtered by an O2+ ion beam (1 keV, 300 nA) over an area of 190 × 190 µm2. Analyses were performed with a Bi+ ion beam (25 keV, 2 pA) over an analyzed area of 60 × 60 µm2, and positive secondary ions were analyzed.

Negative ion analysis were also carried out after the altered monoliths were immersed in a solution enriched with isotopic tracers. After immersion in the tracer solution, the monoliths were taken out, air-dried for 10 s to remove the water meniscus, immersed in liquid nitrogen for 10 min and then placed on a cooled sample holder. Only one sample was analyzed at a time, to avoid overheating the chamber. Sputtering cycles were performed by primary Cs+ ions (2 kEV, 94 nA) over an area of 200 × 200 µm2. Analyses were carried out using a primary Bi3+ beam (25 keV, 0.1 pA) over an area of 50 × 50 µm2 where negative secondary ions were analyzed. Surface neutralization was achieved by pulsed flow of low-energy electrons ( < 20 eV). The depth of the crater created by the sputtering cycles was measured using a 1D mechanical profilometer.

To calculate the porosity based on ToF-SIMS elemental profiles, the following procedure was conducted:

-

Elemental profiles are obtained by a double normalization (Ii/IAl)/(Ii0/IAl0), with Ii refers to intensities for element i, and 0 refers to pristine glass. Al is considered as an immobile element in the experimental conditions of the study.

-

Free volume left by the release of B, Na or Ca are calculated based on ionic radius of the elements. The volume occupied by BO3, BO4-, Na+ and Ca2+ are 0.029 nm3, 0.0521 nm3, 0.00444 nm3, 0.00419 nm3, respectively.

-

At each z position the sum of the free volumes given by the fraction of B, Na and Ca release is calculated, providing a local value of porosity.

-

The total porosity corresponds the integral of the porosity profile.

Transmission electron microscopy (TEM)

Transmission electron microscopy was used to observe the thickness and morphology of alteration gels formed on B10A2 and B10A1 glass monoliths. For this purpose, thin TEM lamellae were prepared by abrasion with a gallium focused ion beam (FIB) using a 30 kV FEI Helios 600 Nanolab SEM at CP2M, Université Aix-Marseille III (France) with standard FIB procedures. The FIB TEM lamellae were then observed with a Technai G2 FEI TEM equipped with a 200 kV LaB6 source, again at CP2M.

Thermogravimetric analysis (TGA)

Thermogravimetric analysis (TGA) was used to determine the amount of water in the gels. For this purpose, core-altered gel powders were rehydrated by being placed at 98% relative humidity imposed by a saturated solution of K2SO4 for 24 h. TGAs were then carried out using a SETARAM SETSYS TMA S60/58507 by heating the powders to 450 °C with a ramp of 10 °C/min followed by a 10 min step. The mass losses measured correspond to the quantity of water present within the gels, from which the porosity occupied by this water can be estimated. These analyses were carried out by Primeverre in Montpellier (France).

Spectroscopic ellipsometry (SE)

Spectroscopic ellipsometry (SE) analyses were used to determine the altered thickness of the various glass monoliths. These analyses were carried out on an Alpha-SE, J.A. Woollam Co. spectroscopic ellipsometer with a wavelength range of 381 to 893 nm at the Pennsylvania State University (USA). The back of the sample was roughened to avoid back-side reflection.

Data availability

Data is provided within the manuscript or supplementary information files

References

Gin, S., Delaye, J. M., Angeli, F. & Schuller, S. Aqueous alteration of silicate glass: state of knowledge and perspectives. Npj Mater. Degradation 5, https://doi.org/10.1038/s41529-021-00190-5 (2021).

Gin, S. et al. Insights into the mechanisms controlling the residual corrosion rate of borosilicate glasses. Npj Mater. Degradation 4, https://doi.org/10.1038/s41529-020-00145-2 (2020).

Ngo, D. et al. Spectroscopic ellipsometry study of thickness and porosity of the alteration layer formed on international simple glass surface in aqueous corrosion conditions. Npj Mater. Degradation 2, https://doi.org/10.1038/s41529-018-0040-7 (2018).

Ngo, D. et al. Hydrogen bonding interactions of H2O and SiOH on a boroaluminosilicate glass corroded in aqueous solution. Npj Mater. Degradation 4, https://doi.org/10.1038/s41529-019-0105-2 (2020).

Frugier, P., Minet, Y., Rajmohan, N., Godon, N. & Gin, S. Modeling glass corrosion with GRAAL. Npj Mater.Degradation 2, https://doi.org/10.1038/s41529-018-0056-z (2018).

Grambow, B. & Müller, R. First-order dissolution rate law and the role of surface layers in glass performance assessment. J. Nuclear Materials 298, 112–124, (2001).

Ma, T. Q. et al. A mechanistic model for long-term nuclear waste glass dissolution integrating chemical affinity and interfacial diffusion barrier. J. Nucl. Mater. 486, 70–85 (2017).

Kerisit, S. & Du, J. C. Monte Carlo simulation of borosilicate glass dissolution using molecular dynamics-generated glass structures. J. Non-Crystalline Solids 522, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jnoncrysol.2019.119601 (2019).

Delaye, J. M., Tiwari, S., Brun, E., Fossati, P. C. M. & Gin, S. Advanced Monte Carlo method for simulating glass alteration: Application to aluminoborosilicate glasses. J. American Ceramic Society 108, https://doi.org/10.1111/jace.20167 (2025).

Taron, M., Gin, S. & Delaye, J. M. Impact of B and Al on the initial and residual dissolution rate of alumino-boro-silicate glasses. Part I: kinetic data. Npj Mater. Degrad Submitted 9, 32 (2025).

Aréna, H., Rébiscoul, D., Garcès, E. & Godon, N. Comparative effect of alkaline elements and calcium on alteration of International Simple Glass. Npj Mater. Degradation 3, https://doi.org/10.1038/s41529-019-0072-7 (2019).

Collin, M. et al. ToF-SIMS depth profiling of altered glass. Npj Mater.Degradation 3, https://doi.org/10.1038/s41529-019-0076-3 (2019).

Hellmann, R. et al. Nanometre-scale evidence for interfacial dissolution-reprecipitation control of silicate glass corrosion. Nat. Mater. 14, 307–311 (2015).

Ogrinc, A. L., Zhou, Y. X., Hahn, S. H., Lin, Y. T. & Kim, S. H. Revealing the structure of the sodium-leached layer of soda lime silica glass: A comprehensive spectroscopic analysis. J. Non-Crystalline Solids 600, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jnoncrysol.2022.121989 (2023).

Gin, S. et al. Atom-Probe Tomography, TEM and ToF-SIMS study of borosilicate glass alteration rim: A multiscale approach to investigating rate-limiting mechanisms. Geochimica Et. Cosmochimica Acta 202, 57–76 (2017).

Doremus, R. H. Interdiffusion of hydrogen and alkali ions in a glass surface. J. Non-Crystalline Solids 19, 137–144 (1975).

Petit, J. C. et al. Hydrated-layer formation during dissolution of complex silicate-glasses and minerals. Geochimica Et. Cosmochimica Acta 54, 1941–1955 (1990).

Bunker, B. C. Molecular mechanisms for corrosion of silica and silicate-glasses. J. Non-Crystalline Solids 179, 300–308 (1994).

Gin, S. et al. A General Mechanism for Gel Layer Formation on Borosilicate Glass under Aqueous Corrosion. J. Phys. Chem. C. 124, 5132–5144 (2020).

Strachan, D. et al. On the dissolution of a borosilicate glass with the use of isotopic tracing - Insights into the mechanism for the long-term dissolution rate. Geochimica Et. Cosmochimica Acta 318, 213–229 (2022).

Collin, M. et al. Structure of International Simple Glass and properties of passivating layer formed in circumneutral pH conditions. Npj Mater. Degradation 2, https://doi.org/10.1038/s41529-017-0025-y (2018).

Gin, S. et al. Dynamics of self-reorganization explains passivation of silicate glasses. Nat. Commun. 9, https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-018-04511-2 (2018).

Damodaran, K., Delaye, J. M., Kalinichev, A. G. & Gin, S. Deciphering the non-linear impact of Al on chemical durability of silicate glass. Acta Materialia 225, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.actamat.2021.117478 (2022).

Cagnon, B., Daval, D., Cabié, M., Lemarchand, D. & Gin, S. A comparative study of the dissolution mechanisms of amorphous and crystalline feldspars at acidic pH conditions. Npj Mater. Degradation 6, https://doi.org/10.1038/s41529-022-00240-6 (2022).

Lu, X. N., Ren, M. G., Deng, L., Benmore, C. J. & Du, J. C. Structural features of ISG borosilicate nuclear waste glasses revealed from high-energy X-ray diffraction and molecular dynamics simulations. J. Nucl. Mater. 515, 284–293 (2019).

Cailleteau, C. et al. Insight into silicate-glass corrosion mechanisms. Nat. Mater. 7, 978–983 (2008).

Cailleteau, C., Devreux, F., Spalla, O., Angeli, F. & Gin, S. Why Do Certain Glasses with a High Dissolution Rate Undergo a Low Degree of Corrosion?. J. Phys. Chem. C. 115, 5846–5855 (2011).

Arab, M. et al. Aqueous alteration of five-oxide silicate glasses: Experimental approach and Monte Carlo modeling. J. Non-Crystalline Solids 354, 155–161 (2008).

Damodaran, K., Gin, S., Naranayasamy, S. & Delaye, J. M. On the effect of Al on alumino-borosilicate glass chemical durability. Npj Mater. Degradation 7, https://doi.org/10.1038/s41529-023-00364-3 (2023).

Frugier, P., Martin, C., Ribet, I., Advocat, T. & Gin, S. The effect of composition on the leaching of three nuclear waste glasses: R7T7, AVM and VRZ. J. Nucl. Mater. 346, 194–207 (2005).

Zapol, P., He, H. Y., Kwon, K. D. & Criscenti, L. J. First-Principles Study of Hydrolysis Reaction Barriers in a Sodium Borosilicate Glass. Int. J. Appl. Glass Sci. 4, 395–407 (2013).

Acknowledgements

Authors are grateful to Géraldine Parisot (CEA, Marcoule) and FILAB for ICP-OES analyses, Laurent Duffours (Primeverre, Montpellier) for sample preparation and TGA analyses, Martina Cabié (CP2M, Marseille) for FIB lamella preparation and TEM observation, Loan Laï (Tescan Analytics, Fuveau) for ToF-SIMS analyses.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

M.T. was responsible for the corrosion experiment and interpretation. H.K. and S.K. realized the SE experiments. S.G. and J.-M.D. supervised the study. M.T. and S.G. wrote the paper. All the authors participated in editing of the paper.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Taron, M., Gin, S., Kaya, H. et al. Impact of B and Al on the initial and residual dissolution rate of alumino-boro-silicate glasses. Part II: gel properties. npj Mater Degrad 9, 59 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41529-025-00576-9

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41529-025-00576-9

This article is cited by

-

Insights into gel maturation from alteration of borosilicate glass from 7 days to 27 years

npj Materials Degradation (2025)