Abstract

Nuclear glasses are made of highly soluble (B) and low soluble (Si, Al) glass formers. This paper investigates the influence of these two types of elements on the initial and residual alteration rates of 6-oxide borosilicate glasses with varying B and Al contents. The results show that Al, by strengthening the glass network, leads to a decrease both in the glass matrix hydrolysis and in the gel reorganization. This provides a reduction of the initial dissolution rate and an increase in the residual rate due to a delay in the passivation effect. Regarding B, when its content in the glass is sufficient to form a continuous sub-network of Si‒O‒B bonds, it strongly increases both the initial and residual rates. However, below the threshold (estimated between 5.5 mol% and 9.7 mol% of B), its effect on the initial and residual rate becomes negligible.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

The water-induced alteration of borosilicate glasses is at the forefront of numerous industrial challenges due to the widespread use of these glasses in various applications. Examples include their use in implantable medical devices, laboratory glassware, mirrors for space optics, and the containment of long-lived radioactive waste from the reprocessing of spent nuclear fuel. The alteration of these glasses in the presence of water involves numerous coupled mechanisms that depend on both the glass composition and the alteration conditions. Recent review articles provide a comprehensive overview of the knowledge accumulated in this field1,2,3.

In brief, the dissolution behavior of borosilicate glass in contact with water can be delineated into two distinct phases. Initially, dissolution occurs at a rate governed by the hydrolysis of the glass network, with no influence from the elements released into the solution. Subsequently, a residual dissolution rate regime ensues, wherein the decreasing affinity of the dissolution reaction is impacted by high concentrations of dissolved Si and the formation of a passivating layer that reduces the transport of elements between the glass and the solution2,3. This passivating layer, also called gel, typically amorphous in nature, can be destabilized by the precipitation of secondary phases, potentially leading to a resumption of glass alteration4,5,6. The initial dissolution rate is characterized by a linear release of Si into a highly diluted solution, preceded by faster reactions such as interdiffusion, also called ion-exchange. These fast reactions involve interactions between hydrogenated species and elements acting as glass modifiers, as well as B − O − X (X = Si, Al, B) bonds hydrolysis. The predominance of these reactions is contingent upon the non-bridging oxygen (NBO) content of the glass and the pH level. A more acidic pH intensifies the exchange reactions7. The release of glass components during this phase follows a square root of time dependency, unlike the hydrolysis of the silicate network, which remains constant as long as the solution remains diluted. The mechanisms governing the residual dissolution rate are still a subject of debate and appear to be influenced by the glass composition, alteration conditions (pH, solution composition), and the progress of the reaction8. Potential rate-limiting mechanisms include the rate of water diffusion in the glass triggering ion-exchange reactions or B hydrolysis from the silicate network9, as well as the transport of dissolved species through the gel or the precipitation of secondary phases8. Even though these mechanisms are accepted by the scientific community, none of the existing models are able to accurately explain the effect of glass composition on reaction rates2. For that, a better understanding of the role of key elements, such as B or Al on glass dissolution rates determined at various reaction progresses is important.

In this study, we focus on six glasses with varying proportions of low soluble (called I for insoluble) elements (Si, Al) and soluble (S) elements (B, Ca modifier and Na modifier). Note that this is a common but simplistic vision of the role of glass species as, depending on the conditions, Ca, Na and potentially B can be either fully dissolved or retained in gel. Ca and Na have a constant concentration in these glasses. The glasses are divided into two series: In the first series of 3 glasses, the Si/Al ratio remained constant with only the S/I ratio varying. Inversely, the second series of 3 glasses have varying Si/Al ratio and constant S/I ratio. The names of the glasses are given solely based on their molar content of B and Al (with Al denoted as A). This results in names of the type BxAy. It is worth noting that the glass B10A2, also called CJ3 elsewhere, has already been studied10. It is as simplified version of ISG or SON68 glass.

These glasses underwent both initial dissolution rate and residual rate measurement under identical temperature and pH conditions (90 °C and pH 9) to better understand the impact of Si, Al and B on these two kinetic regimes. The whole study is split in two parts. In this first part, we present and discuss the reaction kinetics. The second part, which is the subject of another dedicated article, addresses the physico-chemical characteristics of the gels formed under residual rate conditions.

Results

Initial dissolution rate

The initial dissolution rate, r0, was measured for all six glasses on powders and monoliths in a solution at pH = 9 and 90 °C. The results of these experiments, along with the conditions under which they were conducted, are provided in Table 1 and depicted for monolith tests in Fig. 1.

As indicated in Table 1, the pH of the solution remained stable and close to the targeted value during the experiment. Silicon release into the solution was monitored for both powder and monolith experiments through UV-visible spectrophotometric analysis of solution samples collected at different time points. Normalized Si mass losses (Fig. 1) indicate that Si release over time is linear for all glasses, indicative of constant dissolution rate of each glass. Initial dissolution rates for each glass, r0, are provided in Table 1.

Results obtained on monoliths are the most accurate as the reactive surface area is known with less than 1% uncertainty11. For powder, the reactive surface considered is either the estimated geometric surface or the specific surface measured by BET method. Results obtained from normalization to the BET surface area are closer to values obtained for monoliths (difference < 30%) compared to normalization to the geometric surface area (up to 96% difference). The difference for B10A2 is even more significant but cannot be considered valid due to the presence of grinding fines which are not considered in the determination of the geometric surface area. However, in the literature, the geometric surface area is sometimes considered as the actual reactive surface and, in some cases, shows better agreement than the BET surface area11,12,13. It can be assumed that the agreement between BET and geometric surface area depends partly on the dissolution rates. The rates measured in this study are relatively low compared to some rates determined by Gin 202013. Therefore, taking into account surface roughness up to nanoscale as obtained by the BET method may not have significance when several micrometers of glass are dissolved during the experiment. However, even for glass B14A3, which exhibits the highest dissolution rate and an estimated alteration thickness of 1.5 µm at the end of the experiment, the dissolution rate normalized to BET is closer to the rate determined on monoliths (-5%) than the rate normalized to geometric surface area (50%).

Regarding the monoliths, the total mass losses measured at the end of the experiment (obtained by weighing) is shown in Fig. 1 by empty symbols are slightly lower but close to the normalized Si mass losses determined from solution analyses. From this result, one can wonder if a gel could have formed to account for the slight difference. The linear release of Si, and the congruency of the dissolution (Fig. 2) strongly indicates that if such a gel exists, it has no significant impact on the rate. Note that the gel formed in initial dissolution rate conditions are expected to be highly porous and non protective, unlike those formed in silica saturated solution14 (see the next experiments in residual rate conditions).

The initial dissolution rate of the B10A2 (also called CJ3 in the literature) glass has been studied on multiple occasions under the same conditions as those applied here10,13. Gin et al. (2012)10 measured a value of r0 of 2.4 g.m-2.d-1 normalized to the BET surface area of glass powder, while Gin et al. (2020)8 reported a value of 9.9 ± 3.0 g.m-2.d-1 normalized to the geometric surface area. The latter indicated that the difference in normalization could imply a factor of 2 to 4 between the values of r0. The values obtained on powders are directly comparable with those obtained by Gin et al. (2012) as both are normalized to the BET surface area10. There is a factor of 2.75 between r0 measured here and that measured in 2012. Comparing now with the r0 value measured in 2020 normalized to the geometric surface area, a factor of 1.5 between the two values is obtained, which is lower than stated by Gin et al. (2020)13 between BET and geometric surface areas. The initial rate measured on powders for B10A2 thus appears slightly higher than those previously measured but remains nevertheless close. The difference could be explained by the presence of grinding fines (B10A2 glass powder was not washed), whose rapid dissolution during the test led to a significant reduction in the reactive surface measured by BET.

The congruency of the dissolution was investigated by monitoring the release of all the glass elements through ICP-OES analysis for monolith experiments only. The normalized mass losses of these elements are depicted in Fig. 2, except for calcium, for which analysis results were not usable, likely due to sample contamination in the collected solution. From the normalized mass losses, and for each of the six glasses studied, initial dissolution rate, r0 were calculated for Si, B, Al and Na. Results are presented in Table 2. Figure 2 and Table 2 show that the release of glass elements occurs linearly over time for all elements and that, within uncertainties, the dissolution of glasses is congruent. Moreover, the agreement between the normalized mass losses of Si and the total mass losses of the monoliths represented in Fig. 1 is another indicator that dissolution is congruent in the tested conditions. These observations indicate that interdiffusion is negligible in these conditions, unlike under acidic pH7,15. Furthermore, as Si‒O‒Si are both the most numerous and the less hydrolysable linkages within these glasses, their hydrolysis should control the initial dissolution rate of the glasses.

Across the entire series of studied glasses, the initial dissolution rate calculated from Si varies between 2.4 ± 0.6 and 32.6 ± 6.3 g.m-2.d-1 depending on the glass composition. Figure 3 depicts the initial dissolution rates of studied glasses as a function of the fraction between soluble and insoluble elements. In a first approximation, we observe an increase in r0 with the S/I ratio. However, it also appears that for the same value of S/I, the r0 varies beyond the measurement uncertainties. Moreover, no correlation was found between r0 and NBO/Si or the fraction of four-coordinated B, BIV (given in Table 4). When r0 is plotted as a function of Si+Al (mol%), a linear decrease in initial dissolution rate is observed with increasing content of these two network glass formers, with the exception of B6A4. Si and Al are both difficult-to-hydrolyze network formers, contributing to the hydrolysis resistance of the vitreous network. However, given the way glass compositions are defined, the sum of Si+Al is inversely proportional to the B content within the glasses. It can then be considered that an increase in B content leads to an increase in r0. This interpretation seems as valid as the first one: hydrolysis of B atoms is much easier than that of Si and Al atoms under dilute conditions16, and the dissolution of B leads to a weakening of the entire vitreous network, thus favoring its dissolution. We thus observe destabilization of the vitreous network with an increase in B content and consolidation of the network with an increase in Si+Al content. The reinforcing role of Al in the vitreous network is discussed further.

The fact that the B6A4 glass stands out from the trend probably likely arises from the low B content of this glass. Indeed, in high B content glass such as CJ3 (B10A2), or ISG, molecular dynamic simulation has demonstrated that Si‒O‒B bonds create a continuous subnetwork with that formed by Si‒O‒Si and Si‒O‒Al bonds17,18. For B6A4 glass the ratio (Si‒O‒B + Al‒O‒B)/(Si‒O‒Si + Si‒O‒Al) is equal to 0.44, much lower than for the other glasses in the series (between 0.92 and 1.50). We can hypothesize that the discontinuity of a more soluble subnetwork (Si‒O‒B bonds) alters the observed trend. This point will be discussed more broadly later in the study.

Residual rate

The residual dissolution rate were measured for all six glasses in a solution close to saturation with respect to amorphous silica, at pH = 9 and 90 °C. Figure 4 presents the kinetic data in the form of equivalent thickness, ETh(i), determined from solution analyses. Generally observed is a preferential release of B, accompanied by simultaneous or slightly less significant release of Na. This is notably the case for B11A6, where the Al content is the highest, and where some Na is required to compensate for the charge of Al retained in the alteration layer, as the Ca content is not sufficient to compensate for all Al atoms19. However, B6A4 glass exhibits an alteration behavior different from the others. For this glass, Na is preferentially released, but B is likely retained in the alteration layer, along with Ca and Al, and even more than Si (this is confirmed by solid-state analysis detailed in the sister paper20).

All the curves depicted in Fig. 4 show an inflection followed by a nearly linear segment. The choice was made to calculate residual alteration rates from linear regression on B release in the last part of the curve, with as many points as possible to obtain the best possible fit (SI Fig. 1). Across the entire glass series, the rr values indicated in Table 3 vary over three orders of magnitude, an amplitude much larger than that noticed for r0. An attempt to correlate these rates with glass composition was made. Figure 5 represents the best-fitted correlation. It appears that the residual rate increases with Al content of the glass, except for glass B6A4, which does not follow the highlighted trend. This difference can be explained by the distinct behavior of glass B6A4, as mentioned earlier, where B is retained in the alteration layer. However, even considering this difference and using Na as a tracer element for this glass, the measured residual rate is (2.7 ± 1.6) x 10-4 g.m-2.d-1 (hollow symbol in Fig. 5) remains off the observed trend, indicating that at low concentration in the glass, B has not the same impact on residual rate than for the other glasses.

Since the initial and residual rates were measured under the same temperature and pH conditions, the rate drop can be estimated by taking the ratio between r0 and rr. This ratio provides an estimate of the gel’s passivation efficiency throughout the duration of the experiment. Results are given in Table 3. Depending on the glass composition, the rate drop ratio r0/rr varies over three orders of magnitude. This result indicates that, despite being composed of the same elements, the gels do not passivate the underlying glass in the same manner. It is worth noting that we have not found a strong correlation between r0/rr and any compositional parameter (S/I,%B, %(Si + Al)…).

Given the challenge of establishing a relationship between the residual rate, the rate drop, and the composition of the glasses for the entire series, another parameter was identified in an attempt to correlate alteration kinetics and glass composition. The normalized boron mass losses were fitted to a function of the form NLB (t) = a + b·e-t/τ (SI Fig. 2), where τ corresponds to the characteristic time of transition between the initial and residual alteration regimes. The values of τ are given in Table 3. Figure 6 represents the best-fitted correlation, showing the evolution of τ as a function of the Si + 2 Al content (mol%). This evolution is linear for all six glasses of the series. It seems that the moment at which the transition between the initial and residual alteration regimes occurs is governed by the content of less soluble network formers, especially with a significant contribution from Al, which must be counted twice to obtain a good fit. The higher the content of network formers retained in the gel, the later the transition between the initial and residual regimes. This correlation can be explained by both an increase of gel formers (Si and Al) and a stiffening of the glass and gel networks due to an increase of Al content, which decreases the degree of freedom for reorganizing the structure and thus slows down the recondensation of silanols, thus facilitating the formation of a protective gel against alteration. In the sister paper related to the gel characterization, a complementary explanation is provided20.

Discussion

Alteration kinetics of six alumino-borosilicate glasses were studied from the initial to the residual regime at 90 °C and pH 9.

These alteration experiments highlight the congruence of the dissolution of the glass constituents in the initial regime and the decrease in this rate with Si+Al content, or an increase with B content, unlike B6A4 glass which stands out of the trends. Moreover, a control of the initial dissolution rate by the hydrolysis of Si‒O‒Si and Si‒O‒Al linkages is established. It seems also key to distinguish high B content glass from low B content glasses that did not behave similarly. For the latter, B does not seem to weaken the glass network as it does for the other glasses.

Regarding the residual regime, it was demonstrated that, in similar conditions as in the present study, the residual rate of ISG-type glasses is controlled by the hydrolysis of Si‒O‒B linkages8,21. Consistent with this model, we observe for all glasses, except for the B6A4 glass, a preferential release of B and Na, compared to Si, Al, and Ca which are almost totally retained in the gels (for more details, see sister paper20). The residual rate increases with an increase in Al content in the glass. A characteristic time to reach the residual regime, τ, is estimated from the kinetic data. This parameter evolves linearly with an increase in Si+2 Al content, indicating that the restructuring of the gel network is a key mechanism associated with the decrease in the glass alteration rate.

The alteration kinetics experiments on the glass series provide insights into different alteration regimes. These regimes do not depend on the same parameters, but the significant role of aluminum is highlighted in both kinetic regimes: the increase in aluminum content can be either beneficial or detrimental depending on the studied alteration regime.

In the initial rate regime, the role of aluminum has been the subject of numerous studies22,23. The role of this element is complex: at Al2O3 low content ( < 3.5 mol%), an increase in the Al content leads to a significant decrease in glass alteration; at intermediate content (3.5 mol% < x < 19 mol%), the effect of aluminum still lowers glass alteration but is less pronounced; at high content ( > 19 mol%), glass alteration increases significantly22. Recent studies have demonstrated the ease of aluminum dissolution and its reinforcing effect on the silicate network. Indeed, the activation energy for the dissociation of silicon atoms with aluminum as their nearest neighbors is higher than that of silicon atoms in a pure silica network23. For the glasses selected for this study, a decrease in r0 is observed with increasing Si and Al content. Nonetheless, the role of aluminum could not be separated from that of silicon. The decrease in the initial dissolution rate can be simply related to the polymerization and strength of the vitreous network with the increase in less hydrolysable network formers.

The influence of Al on the residual rate regime is less documented, but in general, an increase in Al content appears to lead to a decrease in the residual rate24. Here, the opposite effect is observed. Overall, an increase in Al content in the glass leads to an increase in the residual rate. Qualitatively, the effect of Al can be compared to the effects of Zr in borosilicate glasses25,26. It has been shown that an increase of Zr in glass leads to a decrease in the initial dissolution rate. However, in the residual rate regime, at low Zr content, the residual rate was greatly reduced, whereas an opposite effect was noted for high Zr content glasses. This non-linear response was explained considering that Zr prevents the dissolution of atoms in their surroundings (Si, Al, B) and thus slows down gel reorganization. It is therefore conceivable that the reinforcement provided by Al to the silicate network delays the formation of a passivating gel, with a more pronounced effect for high Al content glasses. This delay in the formation of a passivating gel is observed in the evolution of τ, the characteristic time of transition between the initial and residual regimes. The linear correlation between τ and Si+2Al content in the glass, is consistent with a reinforcing role of Al, similar to Zr.

This study also helps to better understand the role of B on the two studied kinetic regimes. The most likely hypothesis is that the glass with 5.5 mol% of B (B6A4) does not contain enough Si‒O‒B linkages to allow a soluble sub-network to form a continuous subnetwork of weak bonds through the aluminosilicate network. As a result, the residual rate of this glass is no longer controlled by the dissolution of B, as it is the case for all other glasses in the series, as well as for ISG glass8. This leads to a strong decoupling between B and Na in the residual regime and a characteristic time τ much longer than for the other glasses.

The continuation of the study focuses on the physicochemical characteristics of the gels formed under silica saturation conditions and is presented in the sister paper20. It deepens the understanding of the effects of Al and B on the chemical durability of glasses.

Methods

Glass preparation

Six five-oxide glasses (SiO2-B2O3-Al2O3-Na2O-CaO) were formulated with a wide range of composition outside of the scope of classical nuclear glass. The six glasses were divided into two series:

-

A series comprising three glasses for which the Si/Al ratio is kept constant and the soluble/insoluble elements (S/I) ratio is variable (elements considered soluble or insoluble are described below). The B content varies widely from 5.5 to 14.1 mol%;

-

A series comprising three glasses for which the soluble/insoluble elements (S/I) ratio is kept constant and the Si/Al ratio is variable. The Al content varies widely from 0.8 to 5.6 mol%.

-

In order to determine the soluble/insoluble elements ratio, several assumptions were made based on experimental or numerical data from the literature19,27. It was assumed that:

-

the soluble elements are B and Ca and Na if these last two elements are not a charge compensator for aluminum;

-

the low soluble elements (called insoluble for simplicity) are Si and Al;

-

Al is compensated in priority to B, first by Na, then if necessary by Ca;

-

B is compensated by Na only.

For instance, in the case of B11A6 glass, all the Al is compensated by Na, since the Na content is higher than that of Al. The remaining Na is used to compensate for the B. Therefore, the quantity of soluble elements therefore corresponds to all B atoms, all Ca atoms (as none is used to compensate Al) and Na not used to compensate Al (Na – Al), and the quantity of insoluble elements to all Si and Al.

Table 4 lists glass compositions in elemental mole percent (el mol%), S/I and Si/Al ratios, and indicates the names of the glasses (BxAy) with x and y the rounded elemental molar percentages of B and Al, respectively.

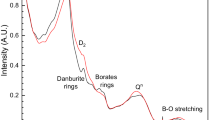

The glasses were synthesized from high-purity oxide and carbonate powders, mixed in a Turbula® T2F to ensure the homogeneity of the initial mix. The powder mix was then placed in a rhodium-plated platinum crucible to be heated in a Pyrox® RKA23 electric furnace for two successive melts. During the first melt, the temperature increased by 300°C/h to reach 850°C, for 1 h to perform a decarbonation dwell. The mixture was then heated 300°C/h to Tf (indicated in Table 4) and held at this temperature for 3 h before being quenched on a fall plate. The glass obtained was crushed and a small quantity was used to determine the glass transition temperature Tg (indicated in Table 4) with a SETARAM SETSYS TMA S60/5807 TGA in differential scanning calorimetry (DSC) mode under argon atmosphere on approximately 60 mg of glass placed in an alumina crucible. A heating rate of 10 °C/min up to 1500 °C was imposed. One heating cycle was performed. A second melt was carried out to ensure glass homogeneity, by heating from 300 °C/h to approximately Tf-100, maintained for 1 h, then heating again to Tf. After 15 min at Tf, the glass was poured into a graphite crucible with a section of 25×25 mm2 previously heated to annealing temperature, then directly annealed at a temperature of Tg + 20°C for 1 h, after which the furnace temperature was reduced by 30 °C/h. The density of the glasses produced and the percentage of B[IV] are shown in Table 4. Glass density was measured by hydrostatic weighing in water. 3 measurements were performed on 1 monolith for each composition. The B[IV] percentage was measured by NMR. NMR spectra were collected on an Avance II 500WB Bruker spectrometer operating at a magnetic field of 11.72 T using a Bruker WVT CPMAS 4 mm probe (with a MAS stator free of boron oxide to avoid a strong 11B signal) at a spinning frequency of 12.5 or 14 kHz. The 11B chemical shifts were referenced to external samples of a 1 M boric acid solution (19.6 ppm). NMR data were processed and fitted using a custombuilt code that implements specific lineshapes for amorphous materials and accounts for the distribution of NMR parameters. The error associated the calculation of boron coordination in glasses is ± 1%.

Chemical analysis of glass composition was carried out by ICP-OES after acid dissolution in HCl, HNO3 and HF. The compositions obtained are shown in SI Table 1 as well as the theoretical composition in mole percentage of oxide (ox mol%). The experimental composition is close to the nominal value, with an error relative to the theoretical composition of no more than 10% for all elements. For all experiments, normalization to composition was performed with the experimental value.

Powder and monolith samples were prepared for the alteration experiments. Several monoliths were cut from the glass bars using a diamond saw. The monoliths obtained were 25x25x1 mm3 in size and all six faces were polished with a diamond oil suspension of 1 µm using an automatic polisher. Glass powders were obtained by grinding part of the synthesized bars using a planetary mill and a grain size of 20 µm to 40 µm was isolated by sieving. In order to eliminate fine particules, the powders were washed by sedimentation in acetone followed by ethanol. For B10A2 glass, a previous batch of powder was used, which was found not to have been washed to remove grinding fines. BET surface area was determined by krypton adsorption-desorption measurement and is shown in Table 5.

Initial dissolution rate measurement

Initial dissolution rate experiments were carried out in 1000 mL or 500 mL perfluoroalkoxy (PFA) reactors placed in an oven at 90 ± 1°C. Glass was altered for less than 4 hours in powder or monolith form in a deionized water solution adjusted to pH = 9 ± 0.1 with a 1 mol/L LiOH solution, with two separate experiments carried out for each glass to determine the influence of sample shape on the initial dissolution rate measurement. The S/V ratio varied between 0.01 and 0.2, depending on the powder and monolith experiments and the chemical durability of the glasses. The experiments have been designed so that the solution concentration can be measured without leaving the initial rate regime. In order to ensure the homogeneity of the alteration solution, a magnetic stirring system was used. Samplings of 3 mL each were taken from the solution at various durations. They were filtered at 0.2 µm to avoid the presence of powder grains and analyzed by UV-visible spectrophotometry and ICP-OES. The pH of the solution was measured at the beginning and end of the experiment.

Residual rate measurement

Longer-term alteration experiments were carried out in static mode in 50 mL PFA reactors in 40 mL of alteration solution pre-saturated with amorphous silica, in order to accelerate the reach of the residual regime and limit glass dissolution. For that, high purity silica gel (Sigma Aldrich 200 µm- 425 µm mesh particle size) was dissolved at 90 °C pH 9.5 for a few days and the pH was then adjusted to 9 by adding diluted Normapur HNO3 (VWR Chemicals). Silicon concentrations over time are shown in Figure S3. Alteration was carried out at pH = 9 and 90 °C. A mass of 1 g of glass powder with a particle size of 20 µm -40 µm was introduced into the alteration solution. The reactor was placed in a double envelope, i.e. in a larger vessel containing a bottom of water to create a relative humidity of 100% and limit evaporation of the alteration solution. Regular samples of 0.3 mL of the alteration solution were taken at various durations, filtered at 0.2 µm to avoid the presence of powder grains in the sampled solutions, and analyzed by UV-visible spectrophotometry and ICP-OES. After 250 days, the powders were recovered by Büchner filtration, rinsed and oven-dried at 50 °C for at least one night.

Solution analyses

The solution samples taken were analyzed using two techniques to determine the concentrations in solution of all the elements used in the composition of the glasses. Commercial Merck Spectroquant kits were used to measure by colorimetry with a Cary Varian UV-visible spectrophotometer (concentrations ranging from 0.05 to 5 mg/L of boron at a wavelength of 405 nm and 0.5 to 2 mg/L of silicon at a wavelength of 820 nm). For cross-comparison, and to obtain concentrations of the other elements used in glass composition, some samples were analyzed by ICP-OES on a Thermo Scientific ICAP 6300 Duo.

After correcting the concentrations with their respective dilution factors, the normalized mass losses NL (Eq. 1) and equivalent thicknesses ETh (Eq. 2) were calculated for each times from the following equations:

with [i] the concentration of element i in solution, xi the mass fraction of element i in the glass, S the reactive surface area of the glass, V the volume of alteration solution and ρ the density of the glass.

Glass alteration rates were calculated from the evolution of NL as a function of time for the initial rate regime r0 and the residual rate regime rr :

Data availability

Data is provided within the manuscript or supplementary information files.

References

Frankel, G. S. et al. Recent Advances in Corrosion Science Applicable To Disposal of High-Level Nuclear Waste. Chem. Rev., https://doi.org/10.1021/acs.chemrev.0c00990 (2021).

Gin, S., Delaye, J. M., Angeli, F. & Schuller, S. Aqueous alteration of silicate glass: state of knowledge and perspectives. Npj Mater. Degrad. 5, https://doi.org/10.1038/s41529-021-00190-5 (2021).

Vienna, J. D., Ryan, J. V., Gin, S. & Inagaki, Y. Current Understanding and Remaining Challenges in Modeling Long-Term Degradation of Borosilicate Nuclear Waste Glasses. Int. J. Appl. Glass Sci. 4, 283–294 (2013).

Crum, J. V. et al. Seeded Stage III glass dissolution behavior of a statistically designed glass matrix. J. Am. Ceram. Soc. 104, 4145–4162 (2021).

Gin, S. et al. The fate of silicon during glass corrosion under alkaline conditions: A mechanistic and kinetic study with the International Simple Glass. Geochim. Et. Cosmochim. Acta 151, 68–85 (2015).

Parruzot, B. et al. Effect of zeolite type, temperature, and pH on Stage III glass alteration behavior for two nuclear waste glasses. J. Nucl. Mater. 567, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jnucmat.2022.153717 (2022).

Inagaki, Y., Kikunaga, T., Idemitsu, K. & Arima, T. Initial Dissolution Rate of the International Simple Glass as a Function of pH and Temperature Measured Using Microchannel Flow-Through Test Method. Int. J. Appl. Glass Sci. 4, 317–327 (2013).

Gin, S. et al. Insights into the mechanisms controlling the residual corrosion rate of borosilicate glasses. NPJ Mater. Degrad. 4, https://doi.org/10.1038/s41529-020-00145-2 (2020).

Strachan, D. et al. On the dissolution of a borosilicate glass with the use of isotopic tracing - Insights into the mechanism for the long-term dissolution rate. Geochim. Et. Cosmochim. Acta 318, 213–229 (2022).

Gin, S., Beaudoux, X., Angeli, F., Jegou, C. & Godon, N. Effect of composition on the short-term and long-term dissolution rates of ten borosilicate glasses of increasing complexity from 3 to 30 oxides. JOURNAL NON-CRYSTALLINE SOLIDS 358, 2559–2570 (2012).

Fournier, M. et al. Glass dissolution rate measurement and calculation revisited. J. Nucl. Mater. 476, 140–154 (2016).

Icenhower, J. P. & Steefel, C. I. Experimentally determined dissolution kinetics of SON68 glass at 90 °C over a silica saturation interval: Evidence against a linear rate law. J. Nucl. Mater. 439, 137–147 (2013).

Gin, S. et al. Can a simple topological-constraints-based model predict the initial dissolution rate of borosilicate and aluminosilicate glasses? Npj Mater. Degrad. 4, https://doi.org/10.1038/s41529-020-0111-4 (2020).

Gin, S., Ribet, I. & Couillard, M. Role and properties of the gel formed during nuclear glass alteration: importance of gel formation conditions. J. Nucl. Mater. 298, 1–10 (2001).

Advocat, T., Crovisier, J. L., Vernaz, E., Ehret, G. & Charpentier, H. in 14th International Symp on the Scientific Basis for Nuclear Waste Management. 57-64.

Zapol, P., He, H. Y., Kwon, K. D. & Criscenti, L. J. First-Principles Study of Hydrolysis Reaction Barriers in a Sodium Borosilicate Glass. Int. J. Appl. Glass Sci. 4, 395–407 (2013).

Taron, M., Delaye, J. M. & Gin, S. A classical molecular dynamics simulation method for the formation of “dry” gels from boro-aluminosilicate glass structures. J. Non-Cryst. Solids 553, 11 (2021).

Lu, X. N., Ren, M. G., Deng, L., Benmore, C. J. & Du, J. C. Structural features of ISG borosilicate nuclear waste glasses revealed from high-energy X-ray diffraction and molecular dynamics simulations. J. Nucl. Mater. 515, 284–293 (2019).

Angeli, F., Gaillard, M., Jollivet, P. & Charpentier, T. Influence of glass composition and alteration solution on leached silicate glass structure: A solid-state NMR investigation. Geochim. Et. Cosmochim. Acta 70, 2577–2590 (2006).

Taron, M., Gin, S., Kaya, H., Delaye, J. M. & Kim, S. H. Impact of B and Al on the initial and residual dissolution rate of alumino-boro-silicate glasses. Part II: gel properties. NPJ Mater. Degrad.

Damodaran, K., Gin, S., De Montgolfier, J. V., Jegou, C. & Delaye, J. M. Behavior of B in passivating gels formed on International Simple Glass in acid and basic pH. J. Non-Cryst. Solids 598, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jnoncrysol.2022.121938 (2022).

Vienna, J. D., Neeway, J. J., Ryan, J. V. & Kerisit, S. N. Impacts of glass composition, pH, and temperature on glass forward dissolution rate. Npj Mater. Degrad. 2, https://doi.org/10.1038/s41529-018-0042-5 (2018).

Damodaran, K., Delaye, J. M., Kalinichev, A. G. & Gin, S. Deciphering the non-linear impact of Al on chemical durability of silicate glass. Acta Mater. 225, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.actamat.2021.117478 (2022).

Reiser, J. T. et al. Effects of Al:Si and (Al plus Na):Si ratios on the static corrosion of sodium-boroaluminosilicate glasses. Int. J. Appl. Glass Sci. 13, 94–111 (2022).

Cailleteau, C. et al. Insight into silicate-glass corrosion mechanisms. Nat. Mater. 7, 978–983 (2008).

Ledieu, A., Devreux, F., Barboux, P. & Minet, Y. Contribution of Monte Carlo modeling to understanding the alteration of nuclear glasses by water. Nucl. Sci. Eng. 153, 285–300 (2006).

Collin, M. et al. Structure of International Simple Glass and properties of passivating layer formed in circumneutral pH conditions. Npj Mater. Degrad. 2, https://doi.org/10.1038/s41529-017-0025-y (2018).

Acknowledgements

Authors are grateful to Géraldine Parisot (CEA Marcoule) and FILAB for ICP-OES analyses, Thibault Charpentier (CEA Saclay) for RMN analysis, and Laurent Duffours (Primeverre) for sample preparation.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

M.T. was responsible for the experimental realization and interpretation. S.G. and J.-M.D. supervised the study. M.T. and S.G. wrote the paper. All the authors participated in the editing of the paper.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Taron, M., Gin, S. & Delaye, JM. Impact of B and Al on the initial and residual dissolution rate of alumino-borosilicate glasses. Part I: kinetic data. npj Mater Degrad 9, 32 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41529-025-00577-8

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41529-025-00577-8

This article is cited by

-

Insights into gel maturation from alteration of borosilicate glass from 7 days to 27 years

npj Materials Degradation (2025)

-

Impact of B and Al on the initial and residual dissolution rate of alumino-boro-silicate glasses. Part II: gel properties

npj Materials Degradation (2025)