Abstract

The recognition of the early stage of radiation aging and the aggregation of point defects into nanometric clusters pose significant challenges for nuclear structural materials. In this study, we employ positron annihilation spectroscopy to characterize various alloys exposed to severe radiation conditions. A novel approach to data evaluation enables a detailed description of helium-vacancy interactions in defects, ranging from small vacancy clusters to nanometric helium bubbles. This study combines two irradiation experiments to clarify the role of ballistic damage, helium production rates, and irradiation temperature. The obtained data serve as the foundation for a new semi-empirical model that elucidates positron trapping at helium-vacancy clusters and provides realistic experimental equilibrium helium-to-vacancy ratios across a wide range of defect sizes. This work complements and expands current understanding of helium bubble swelling in nuclear materials, offering new insights into the microstructural evolution of materials for the next generation of nuclear facilities.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

In radiation environments of advanced nuclear facilities such as next-generation of fission, fusion, and accelerator-driven systems, high-energy neutron bombardment, combined with thermal and environmental ageing leads to radiation embrittlement and volumetric cavity swelling, even in so-called radiation-tolerant materials. These changes ultimately affect the long-term safety of operation and final decommissioning of the nuclear facility1,2,3,4. From the material engineering point of view, it is critical to know when the microstructure of the irradiated material reaches the stage where it may pose a safety hazard. Predicting the transition from safe to unsafe conditions requires understanding the early stages of the radiation ageing processes, including sinking point defects and transmutation products such as hydrogen and helium.

Recent advances in ion beam technology have enabled targeted simulation of specific damage features—such as helium implantation, vacancy clustering, and early-stage defect formation—under well-controlled experimental conditions.

One of the major drawbacks of material irradiation experiments using charged particle accelerators is the non-uniform damage profile and usually relatively short stopping depth of only a few microns. Such thickness of the modified region is insufficient for the application of many microstructural characterization techniques, often probing a tens of micrometers deep region under the sample surface. Similarly, various micro-mechanical testing techniques have limited application on the samples with only a few grains across their thickness. This, among others, complicates for instance the comparison with the results obtained from mechanical testing on bulk samples irradiated in conventional fast reactors or spallation neutron sources. However, the increased availability of high-energy ion beams for nuclear material research enables to conduct a new generation of irradiation experiments tailored to address various aspects of radiation ageing. This includes implantation of high energy light ions such as hydrogen and helium in studies aimed at early-stage radiation ageing (i.e., low dpa irradiations).

In the last decades, the application of experimental simulation via accelerated light ions was successfully tested worldwide, for instance, using hydrogen ions for neutron fluence simulation and helium ions for alpha particle simulation5. Our previous research6 confirms the feasibility of using low-energy helium implantations to simulate radiation conditions in spallation neutron targets and fusion reactors, what points to the importance of assessment of helium concentration together with displacement damage (dpa) parameter.

In terms of determining helium density in different sizes of vacancy clusters, the literature reports three common approaches. Theoretical modelling of helium-vacancy interactions has been extensively studied using Molecular Dynamics (MD) simulations7,8, while experimental approaches have primarily involved Scanning Transmission Electron Microscopy combined with Electron Energy Loss Spectroscopy (STEM/EELS)9,10,11 and positron annihilation spectroscopy (PAS)6,12,13. Both experimental and theoretical modelling approaches to studying helium-vacancy interactions are constrained by a limited cavity size range, within which they can provide reliable data. This naturally impacts the number of published data points across different scales. As shown in Fig. 1, there is a significantly greater volume of data on larger cavities ( > 1 nm) compared to sub-nanometer ones, resulting in a research bias toward the later stages of defect evolution. Consequently, the formation and impact of large, immobile defect agglomerates—key contributors to radiation-induced embrittlement—are relatively well understood. In contrast, the early stages of microstructural degradation, particularly the transition from isolated point defects to stable defect clusters, remain less comprehensively documented and understood.

To address the above issues and provide the necessary experimental data, the present paper reports a unique experiment, which utilizes multiple energy high-fluence helium implantations14. In this experiment, helium ions were accelerated to energies ranging from 1 MeV to 17 MeV at near-room temperature to achieve a quasi-homogeneous implantation profile in a bulk volume. As discussed in detail later in this paper, the corresponding penetration depth of He ions is comparable to or exceeds the typical grain size (10–50 µm) of ferritic-martensitic steels. Therefore, the helium-modified region encompasses multiple grains and grain boundaries, making it structurally representative and sufficiently thick to support not only non-destructive microstructural characterization techniques but also micromechanical testing (e.g., micropillar compression or nanoindentation) without significant substrate interference15. Unlike comparable bulk irradiation experiments using neutron or proton irradiation16,17, the samples in this study did not induce radioactivity, thereby eliminating the need for hot cell facilities and radiological laboratories for sample analysis.

A unique feature of the samples irradiated in this study is that the region modified by helium implantations closely aligns with the stopping profile of positrons from a conventional 22Na radioisotope source. In this paper, we present the results from positron annihilation lifetime spectroscopy (PALS) and compare them with available PALS data of similar materials irradiated in spallation neutron target. Our previous experimental models describing the positron trapping at helium-vacancy clusters13,18 were extended to cover the full dimensional range of helium-vacancy cavities, from small vacancy clusters to nanometric helium bubbles, by characterizing the helium-filled vacancy clusters and estimating the nHe/nV ratio. Note: In this work, the term “cavity” is used as a general, size-independent expression encompassing all helium-vacancy defects. We define “clusters” as small, sub-nanometer helium-vacancy aggregates (typically < 0.5 nm in radius, often invisible to TEM), and “bubbles” as larger, more evolved helium-filled cavities (typically > 0.5–1 nm) that may be resolvable by TEM and exhibit internal gas pressure.

Furthermore, in the present study, a semi-empirical model has been applied to several alloys irradiated in two distinct radiation environments at various temperatures. The proposed model enables a unique investigation into the effects of both irradiation temperature and helium production rate—from nucleation and coarsening to the formation and evolution of helium bubbles.

Results and discussion

Feasibility of the proposed methodology based on PAS analysis

Positron annihilation lifetime spectra of investigated specimens were analyzed in the LT10 fitting program19 in two steps. In the first step, a two-component model was employed to approximately evaluate the effect of ion-implantation and to assess source contributions (the fraction of positrons annihilating in the positron source, i.e., outside the sample pair) and the resolution function (Table 1). In this step, the source contribution left as a free parameter yielded a value of 25.0%. The source contribution comprises 89.1% of the 382 ps component attributed to Kapton and a 10.9% component of approximately 2 ns associated with air or the polymer foil of the sample holder. This source contribution was subtracted from the fitted curve to obtain the positron lifetime characteristic of studied samples.

From the two-component model, in addition to deriving parameters for the experimental apparatus, we obtained an initial estimation of the material response to irradiation, specifically in terms of average positron lifetime, which showed a significant increase for the implanted samples17. This increase in average lifetime reflects a shift in the annihilation environment: τ1 increased to values characteristic of monovacancy trapping, suggesting that positrons were increasingly captured by radiation-induced vacancies and small vacancy clusters, rather than annihilating in the bulk lattice. Meanwhile, the second component τ2 showed only moderate variations, indicating a transition from intrinsic microstructural traps (e.g., dislocations or oxide particles) to larger irradiation-induced defect complexes.

The major outcome of this step of the fitting routine was the obtaining of the average positron lifetime, which can be compared across the whole series of experimental data. The results clearly show an increase of the τavg which was most pronounced for the materials with low positron lifetime in the as-received condition (Fig. 2). This is in agreement with our previous results reporting the effect of intrinsic vacancy-type defects on the radiation resistance of Fe-Cr alloys18.

The S-parameter from the CDBS, shown in Fig. 3, is a qualitative measure used to determination of the concentration of defects that act as positron traps in materials. Generally, the more pronounced the positron trapping at defects is, the higher the probability that low-momentum (valence) electrons participate in the annihilation process, resulting in an increase in the S-parameter. Therefore, the S-parameters of the irradiated samples in this experiment are correlated with the average positron lifetime data. More detailed discussion on Doppler broadening spectroscopy in the context of irradiated materials can be found in ref.20.

It is well known that the volumetric swelling in austenitic steels is ~5 times more significant when compared to ferritic steels (1%/dpa vs. 0.2%/dpa for austenitic steels and ferritic steels, respectively)21,22,23. This makes austenitic steels less resistant to radiation-induced swelling and restricts their application in some high-flux radiation exposure environments. Based on this, we initially expected the positron trapping at open-volume defects in the two austenitic alloys to be more significant after the implantations. However, as can be seen in Figs. 2, 3, the absolute value of the increase of the positron lifetime does not suggest such behavior. On the contrary, the positron trapping at radiation-induced defects in austenitic steels is lower compared to the f/m steels including the ODS Eurofer, which is generally expected to exhibit high resistance to radiation damage.

Already, these first data suggest that ODS Eurofer exhibits a superior radiation tolerance. In contrast, the traditional ferritic steels such as Eurofer 97 and SIMP both presented an almost equal and maximum increase in mean lifetime.

After a comprehensive evaluation of the selected parameters, all the studied materials exhibit distinct properties after irradiation. The different behavior of the studied variables provides an interesting basis for the suggested conclusions regarding defect formation. Therefore, the initial analysis demonstrates the potential feasibility of the proposed semi-empirical model, which is described in detail in the following text.

Qualitative and quantitative assessment of conditions for semi-empirical model

While the two-component lifetime spectra model enables a quick assessment of the materials response to the conducted radiation treatment, it does not provide the opportunity to identify and quantify the radiation-induced defects. To achieve a more comprehensive characterization, a three-component fitting model was applied in the second step of the procedure. In this fitting model, the first positron lifetime (τ1) and its intensity (I1) were attributed to the material bulk (reduced due to positron trapping at defects24), while the second (τ2, I2) and third (τ3, I3) components were attributed to small and large vacancy clusters, respectively. This fitting model has been used only for the implanted samples, as it anticipates positron annihilation at larger vacancy clusters, which were not expected in unimplanted samples. The results of the three-component fitting model are shown in the Table 2.

In this step of the fitting procedure, the source contribution and the resolution function were fixed based on the two component fitting results. At the same time, the defect parameters (τ, I) were left as free parameters. The routine used for spectra decomposition was discussed in detail in our previous reports, e.g.18 and the approach was found to be applicable for the treatment of the present data.

The presented data treatment, namely the qualitative and quantitative characterization of the helium-vacancy clusters, was facing two main challenges. First, contrary to the known relationship between the positron lifetime and the size of an empty cavity in investigated alloys12,25, the presence of helium in the clusters does not permit a straightforward estimation of the size of the clusters due to unknown nHe/nV ratio. The second challenge comes from unknown positron trapping coefficient of the microstructural cavities, which also depends not only on the size, but on the actual nHe/nV ratio as well26. This coefficient is the scaling factor between the experimentally obtained positron trapping rate and the actual concentration of the given type of defect. In our analysis, the defect concentrations ND1 and ND2 were calculated as the product of the trapping coefficient and the trapping rate, where the trapping rate was derived from the lifetimes and intensities of each defect component identified in the spectra. This methodology, including the parameter extraction approach, is described in detail in our previous work18. On the other hand, the amount of available data collected over the last two decades of research on numerous irradiation experiments and very specific design of the present irradiation experiments enabled us to propose a plausible approach to these peculiarities. Furthermore, the exact known concentration of helium ions implanted in the Monster samples and the plausible assumption that all helium atoms occupy the helium-vacancy clusters (i.e., the concentration of interstitial helium in the matrix is negligible)27 enabled a reasonable validation of the proposed semi-empirical models.

Contrary to previous works, where we used rather discrete values of positron lifetimes and helium-filled nano-cavities, in the present work, we proposed a model that correlates positron lifetime with helium-vacancy cluster size in the whole application range of positron lifetime spectroscopy. In case of empty clusters this range starts at a single vacancy ( ~ 180 ps28,29) and ends in a cluster of ~30–50 vacancies (diameter ~ 0.9–1 nm) with positron lifetime saturating at ~ 500 ps. It is important to note, however, that the presence of helium in vacancy-type defects decreases positron lifetime in these defects. As a result, positron lifetimes shorter than that of a single vacancy cannot be ruled out in the fitting procedure. The presented model employs a bi-modal distribution of defect clusters (characterized by positron lifetimes τ2 and τ3), where τ2 represents small defect clusters and τ3 represents larger defect clusters. This fitting model has been applied in many studies, and its validity has been demonstrated28,30. According to Stoller et al.,7 at room temperature and for He ion irradiation conditions, as helium-vacancy clusters grow, they spontaneously produce Frenkel defects to absorb vacancies, thus releasing internal pressure, leading to a decrease in the nHe/nV ratio. This maintains internal pressure at a relatively low dynamic equilibrium. Based on previous studies on spallation samples irradiated at low temperature to low displacement damage levels, we can reasonably assume that no helium bubbles were formed in the studied materials in the performed irradiation experiment. This assumption is further supported by our previous studies, where TEM-visible helium bubbles were always associated with a positron lifetime component of > 400 ps6,18,31. As can be seen in the Table 2, the measured lifetimes of the τ3 defect component range between 300 ps and 400 ps. At the same time the short defect component (τ2) varies around 180 ps.

Let us assume a logarithmic function (Eq.1) describing the positron lifetime τ as an effective helium-vacancy cluster radius r, which incorporates, to some extent, the convolution of both the physical cluster size and the impact of helium on the positron trapping characteristics (a more detailed explanation is provided later in the paper). This function returns a cluster of a few vacancies for positron lifetime ~ 200 ps and saturates at positron lifetime values below 500 ps. Suggested constants in function are a1 = −0.07, b1 = 500, and c1 = 9400.

While we report this formula to extract the cluster radius (r (nm)) from positron lifetime (τ (ps)), the conventional way of plotting this relationship - τ as a function of r - is presented in Fig. 4. This figure shows all experimentally obtained positron lifetime data with the size attributed using above mentioned assumption of function. The figure shows the defect components (τ2, τ3) obtained for the samples listed in Table 2, as well as theoretically calculated data for empty vacancy clusters in Fe adopted from literature12,25. Compared to this curve, a much steeper slope of the positron lifetime can be observed for helium-containing cavity in the range 175–250 ps (τ2 of the investigated data set). This strong dependency of positron lifetime on the size of the clusters indicates a contribution of another factor, besides the effect of the size. It is reasonable to assume that the contributing factor is helium, which is known to decrease the positron trapping rate at vacancy-type defects. Since the nHe/nV ratio decreases with the cluster size7,27 the above-mentioned hypothesis is plausible. The evolution of the nHe/nV ratio with the cluster size is discussed in detail below. Figure 4 also shows datapoints from previous experiments6 on STIP II—F82H and STIP V—CLAM steel samples, where TEM-visible helium bubbles were correlated with PALS results. Considering the uncertainties associated with the PALS fitting ( < 10 ps) and the qualitative nature of the TEM analysis (~20%), the correlation is very good.

The datapoints correspond to lifetime measurements obtained from the Monster samples presented here as well as from previously studied spallation samples irradiated within STIP II and STIP V programs. For comparison, data representing empty vacancy clusters in BCC Fe (adopted from ref.12) are also included. Additionally, TEM experimental data of STIP II program for F82H and STIP V program for CLAM steel are plotted using values reported in reference 6. Note: A comparison between our predicted τ(r) curve and the theoretical vacancy-only trend for nano-voids in BCC iron suggests that an increased population of He-free intrinsic defects—varying among the investigated materials—would primarily manifest as a change in the initial slope. This effect is expected to be minor, as trapping at radiation-induced helium–vacancy clusters dominates over trapping at native dislocations or oxide particles in the irradiated state.

It is important to note that the positron lifetime is not solely a function of cluster size but also depends on helium content. Therefore, the approach adopted here treats the derived radius as an effective parameter that inherently reflects both the geometric size and the influence of helium. This simplification is necessary for a tractable model and is common in semi-empirical analyses. Additionally, it should be acknowledged that data from spallation samples (represented by red square symbols in Fig. 4) may also be influenced by transmutation hydrogen, which could play a role in the helium–vacancy cluster evolution and thus the positron lifetime. However, this contribution is not explicitly accounted for in the present model, which focuses on isolating helium–vacancy interactions. Therefore, the interpretation of the results presented in this study—as well as any comparison between spallation data and data obtained from hydrogen-free helium implantation experiments—should be made with appropriate caution.

With respect to Fig. 4, it is important to note that most theoretical studies on positron trapping at open-volume defects suggest a saturation of the positron lifetime at a value of approximately 400 ps. However, experimental studies conducted on highly irradiated structural materials containing large vacancy agglomerations13,32,33, including the present study, report positron lifetimes longer than 400 ps. A possible explanation for this discrepancy is the hypothetical formation of positronium in large, mostly empty cavities. Nevertheless, this hypothesis has not been confirmed nor rejected in any experimental study to date.

Establishment and application of the semi-empirical model

Based on the reasoning above and the previously published PAS studies, we proposed a semi-empirical relationship between the equilibrium helium-to-vacancy ratio and the radius of a cluster (Eq.2):

where r is the effective radius of the vacancy cluster in nm, constant a2 = 3.5 and constant b2 = -6.5. Proposed relationship is visualized in Fig. 5, which shows the nHe/nV ratios attributed to the size (radius) of all experimentally obtained positron lifetime data. While not addressing the irradiation temperature explicitly, the plot covers a range of temperatures from 338 to 670 K.

STEM/EELS data published by other authors10,11 from irradiation experiments conducted at elevated temperatures of 620 K10 and 820 K11, respectively, have been included. Note: The horizontal arrow at the top of the plot indicates the direction of increasing irradiation temperature, which strongly influences the observed nHe/nV ratio trends across the different datasets.

The model predicts a sharp decrease in the nHe/nV ratio at small cluster sizes, which is consistent with early-stage, under-pressurized vacancy clusters, followed by a gradual saturation of the ratio for clusters larger than ~1 nm, where helium accumulation becomes more efficient. In this sub-nanometer regime, experimental data are extremely scarce and depend primarily on advanced techniques such as PAS. Importantly, when comparing the PAS-derived data with nHe/nV ratios obtained from STEM-EELS measurements on samples irradiated at elevated temperatures10,11, a clear temperature effect becomes evident. The higher-temperature datasets display systematically larger cluster sizes and higher helium filling, effectively shifting the trend to the right. This behavior is qualitatively indicated by the horizontal arrow in Fig. 5, which illustrates the direction of increasing irradiation temperature and supports the interpretation that temperature significantly influences helium–vacancy cluster evolution.

Reporting the nHe/nV ratios described by the new semi-empirical model, it is interesting to compare it to previously published estimations. In our first study on spallation samples13 we reported 12-vacancy clusters with nHe/nV ratio ~1 to represent the τ2 defect component. Comparing this datapoint(s) to the set of data in Fig. 5, one can see that this value was reasonable yet slightly over-estimated. Although our TEM data6 confirm the accuracy of our proposed semi-empirical model, data taken from the literature by other authors10,11 describe defects in the larger size like helium bubbles.

As discussed above, the data plotted in Fig. 5 correspond to an approximately 350 K interval of irradiation temperatures. While the temperature dependence of the equilibrium nHe/nV ratio was reported as very weak for bubbles with radius > 0.25 nm in the work of Stoller and Osetsky7, the presented data offer a unique opportunity to investigate this relationship in a semi-empirical manner. Figure 6 shows the data from the previous figure plotted as a function of the given irradiation temperature for the τ2 defect components (a) and τ3 defect components (b). Contrary to the work of Stoller and Osetsky, whose molecular dynamics simulations suggest an increasing nHe/nV ratio with temperature, the experimental data presented here indicate a weak negative temperature dependence for small clusters. For larger clusters, their simulations suggest near temperature independence, whereas our experimental results reveal a more complex trend: a positive correlation between the nHe/nV ratio and temperature at lower irradiation temperatures (below approximately 450 K), followed by a negative correlation at higher temperatures. This observation is consistent with the findings of Dai et al.,31 where the initial increase was attributed to helium inflow into radiation-induced vacancy clusters (dark grey region in Fig. 6), and the subsequent decline was linked to cluster coarsening and the formation of TEM-visible helium bubbles (light grey region in Fig. 6).

The observed discrepancy between MD simulations and experimental results likely reflects the fundamentally different nature of the two systems. While MD simulations describe helium bubble behavior in mechanical equilibrium under idealized thermal conditions, the experimental data reflect non-equilibrium irradiation environments—where factors such as helium production rate, defect recombination, vacancy mobility, and microstructural evolution significantly influence the final nHe/nV ratio7.

The reliability of the quantitative assessment of any type of cavities identified in positron lifetime spectra depends on the knowledge of the positron trapping coefficient for the given type of defect. In our previous work18, we suggested a simple cubic ratio of the positron trapping coefficient on the radius of the helium bubble size (\(\mu =4\times {10}^{-14}{r}^{3}\)). This model is reasonable for helium bubbles (i.e., large helium-vacancy clusters) where the nHe/nV ratio depends only weakly on the cavity size. As can be seen in the Fig. 5, such condition is met for cavities with radii > 0.5 nm.

The effect of temperature on the positron trapping rate was addressed in the past with some agreement achieved for empty vacancy clusters but almost no common agreement for helium-filled vacancy clusters. Eldrup and Jensen26 reported a rather weak (if any) temperature effect for the defects of sizes much smaller than the positron thermal wavelength ( ~ 4–10 nm) based on the published studies34,35,36. While the temperature dependence of positron trapping rate into larger voids or gas bubbles has been reported by several studies37,38,39,40, there is little consensus regarding helium-filled vacancy clusters. Recognizing challenges such as the competing effects of helium pressure and open volume on the positron potential well, the difficulty in decoupling helium content from cluster size, and the potential for temperature-induced migration or restructuring of vacancy clusters, our analysis employs a semi-empirical model based on experimentally observed lifetime trends and their correlation with independently validated cluster size estimations (e.g., from TEM for larger bubbles). This approach enables us to capture dominant trends in positron behavior without requiring detailed knowledge of trapping-rate physics in helium-containing clusters, which remains an open area of research.

The availability of positron lifetime data for similar alloys irradiated at different temperatures with different concentration of the transmutation/implanted helium enabled us to suggest a relationship between the specific positron trapping rate (trapping coefficient) and two parameters, i.e., size and irradiation temperature \(\mu \left(r,T\right).\) Suggested dependence is described by following function:

where r is the radius of the vacancy cluster in nm, T is irradiation temperature in K, constant a3 = 4.4 × 10−7, and constant b3 = 2.5. The constants were determined through iterative comparison of the known helium content in the investigated samples with the helium content estimated by the model.

Figure 7 shows the obtained relationship between the trapping coefficient and radius of the corresponding clusters estimated for the investigated materials and samples. As can be seen in the figure, the relationship covers clusters ranging from a few vacancies to bubbles of ~1.75 nm in size (diameter).

When we plot the positron trapping coefficient data as a function of irradiation temperature (Fig. 8), we can see two distinct behaviors of the small a) and large b) defect clusters (represented by the τ2 and τ3 lifetime components). It is worth reminding the reader that the estimation of the helium concentration in the vacancy clusters and corresponding nHe/nV ratios are based on the known concentration of the implanted/transmutational helium atoms, assuming all of them to be accommodated in the clusters. Given the experimental conditions (primarily the irradiation and measurement temperature) and the relatively high mobility of helium atoms as well as high binding energy to vacancy clusters, this assumption, i.e. no helium in the interstitial position of the matrix, is plausible.

The estimated positron trapping coefficients into small clusters (a) and large helium-vacancy clusters (b) plotted as a function of the irradiation temperature. The shaded areas in the right figure illustrate the range of irradiation temperatures with dominantly increasing (dark grey) and dominantly decreasing (light grey) nHe/nV ratio.

As can be seen in Fig. 8a, the positron trapping coefficient (i.e., specific trapping rate of positrons) is decreasing with the irradiation temperature. While higher temperature leads to growth of helium bubbles with typically higher trapping coefficient (Fig. 7), in the case of small vacancy clusters another process prevails—increasing of nHe/nV ratio. This behavior was briefly discussed in the work of Dai et al.,31 as it explained a surprising anticorrelation between the average positron lifetime and displacement damage at low irradiation temperatures ( < 470 K). This phenomenon can be partially seen also in Fig. 8b for large clusters for the similar temperature range. The more understood competitive process with respect to the positron trapping rate is the growth of vacancy clusters with temperature leading to a decrease in their number density and consequently to the increase of the positron mean free path in the diffusion process. As can be seen in Fig. 8 the change of the dominance of the two discussed effects can be found somewhere in the range ~ 450–525 K which can be considered as the irradiation temperature range leading to maximum nHe/nV ratios in the radiation-induced clusters of ~ 0.3 nm ( ~ 10 vacancies).

When we summarize the obtained values of the positron trapping coefficient and plot the data as a function of the estimated nHe/nV ratio (Fig. 9), we can see that the trapping coefficient indeed decreases with the nHe/nV ratio. As can be seen in the figure, this decrease is nearly exponential.

Table 3 summarizes the data used in our semi-empirical model and shows the corresponding discrepancy between the anticipated helium concentration in the microstructure of the studied samples and the helium concentration predicted by our model. Except for a few samples with nearly saturated positron trapping, one can see a very good agreement between the theoretical and semi-empirical data. The average discrepancy is < 42%, which is a reasonable correlation considering the large discrepancy between similar assessments published by various authors in the literature7,9,10,11.

It is worth noting that all the models and reasoning above consider a very narrow equilibrium nHe/nV ratio. In contrast to theoretical models7,41 our semi-empirical model suggests that nHe/nV ratios greater than 1 cannot be practically achieved in any realistic radiation-induced cavities. This study confirms the preliminary outcomes noted in our earlier papers42,43,44, indicating a relatively narrow range of equilibrium nHe/nV ratios in radiation-induced cavities, which can be considered practically independent of helium production rates. In other words, even the most severe radiation environments, with nHe/dpa reaching 100 or more (such as in spallation neutron targets), will not lead to ‘over-pressurized’ cavities in structural materials. In fact, the formation of clusters with nHe/nV > 1 would imply an uneven partitioning of helium among vacancy clusters under constrained production rates. To conserve the global helium-to-vacancy balance, this would necessarily entail the simultaneous presence of under-pressurized or helium-free vacancy clusters—an outcome that appears physically improbable in typical sustained irradiation experiments in bulk materials.

It is also important to note that the models are applicable only for where positron trapping is not saturated, meaning that not all positrons annihilate from trapped states. In the case of near-saturated trapping—defined here as a bulk component intensity below 10% in the fitted PALS spectra (i.e., more than 90% of positrons are trapped at defects)—special attention must be given to the fitting of each component. Before assigning any physically plausible fixed value, its presence should be carefully tested through a series of fitting iterations to ensure that it does not result from a fitting artifact. Because near-saturated positron trapping was evident in all samples irradiated in the present study, this consideration was carefully addressed in the fitting procedure presented in this work.

The presented data and suggested models are based on a bi-modal approximation of the size distribution of the (vacancy-type) defect clusters. While this may not necessarily represent a realistic condition in all types of materials and irradiation conditions, in the present work, it provides a quite realistic characterization of the microstructure arrangement in the studied samples. A typical feature observed in all samples is that the relatively high nHe/nV ratio in small helium-vacancy clusters is compensated by the absorption of vacancies, achieving equilibrium between the internal and external pressures of He-vacancy clusters. This process is accompanied by a decrease in helium concentration and an increase in volume, resulting in an increase of the open volume for positron trapping, and subsequently, an increase in the positron trapping coefficient and lifetime. This leads thereafter to the change of the characteristic lifetime component from τ2 to τ3 component and the corresponding change in the component intensities.

The current and reviewed experimental data, in agreement with the theory of helium bubble swelling, suggest that in the early stages of irradiation, small vacancy-type defects (composed of only a few vacancies) are rapidly generated due to helium migration into radiation-induced vacancies and hinder the recombination of the Frenkel pairs. If the irradiation temperature and the concentration of helium in the matrix favour growth of larger vacancy agglomerations, the nHe/nV ratio can increase in these clusters with irradiation (or annealing) temperature and reach a maximum indicated in Fig. 6. However, with the irradiation temperature increasing further (≳ 450 K), thermally activated defect mobility, particularly vacancy diffusion, promotes further cluster growth. During this process, the cluster volume expands as more vacancies are absorbed, while the helium content increases more slowly or remains nearly constant. This results in a natural decrease in the nHe/nV ratio and to the gradual attainment of dynamic equilibrium, where the nHe/nV ratio reaches a saturated state. At the same time, the growing clusters become TEM-resolvable cavities. Due to the relatively low saturated nHe/nV ratio at this point, these defects can be identified as voids rather than the (He) bubbles.

Methods

Investigated materials

Six different structural alloys have been used for the present study, including four ferritic/martensitic (f/m) and two austenitic alloys. The chemical composition of the materials is shown in Table 4. Among these materials, three steels, including austenitic 310S45, alloy 800H46,47, and ODS steel PM200048, have high chromium content ( > 19 wt.%), while the f/m steels SIMP49,50, Eurofer 9751,52, and its ODS variants have chromium content < 11 wt.%. To ensure broad applicability, the selected alloys span a diverse range of microstructures and compositions, enabling the development of a semi-empirical model focused on irradiation-driven helium-vacancy interactions. While microstructural features such as dislocations and oxide particles are known to influence a material’s response to radiation (potentially enhancing its resistance), this effect occurs primarily by extending the incubation period before bubble swelling initiates18. The fundamental mechanisms governing helium-vacancy clustering and cavity evolution remain qualitatively similar across different alloy systems and are primarily determined by the irradiation environment.

Irradiation experiment

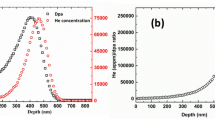

The irradiation (referred to as “Monster”) experiment was carried out at the 6 MV Tandetron ion accelerator at the Advanced Technologies Research Institute, Slovak University of Technology in Bratislava31,53. The detail of the irradiation experiments was previously reported in the paper by Noga et al.14. This unique irradiation experiment was performed using 33 different energies of the helium ion beam starting at ranging between 17 MeV gradually decreasing to 1 MeV. The corresponding fluencies were calculated to obtain a near homogenous helium profile with a mean helium concentration of 1000 ppm (Fig. 10), which is a typical concentration of transmutation helium in numerous published experiments utilizing spallation neutron target irradiations31,43. The average displacement damage produced in the irradiation was 0.162 dpa, calculated using the routine recommended by Stoller et al.44. Although the displacement damage was relatively low, the exceptionally high He/dpa ratio of ~3890 enabled the experimental observation of helium-vacancy cluster evolution in a regime predicted by theoretical models to exhibit He/vacancy ratios well above 1. This experiment was designed to test whether such extreme He enrichment is physically realistic and experimentally achievable under controlled conditions.

a Depth distribution of He concentration after 33 sequential He ion implantation/irradiation steps. The inset illustrates individual implantation profiles at 16 MeV, 16.5 MeV, and 17 MeV. b Ratio of He concentration (appm) to displacements per atom (dpa) as a function of depth overlaid with the positron implantation profile of (a) 22Na source14.

Investigation methods

As discussed above, the irradiation experiment was proposed to enable future assessment of engineering properties—such as hardness, strength, and ductility—using micromechanical testing methods, and to enable the application of conventional positron annihilation spectroscopy utilizing radioisotope sources such as 22Na positron source. This provides positrons with a continuous spectrum of energies up to 540 keV, which corresponds to ~ 85–90% positron stopping in the depth of 65 μm54. The PAS measurements were performed on a combined lifetime-Doppler spectrometer with three BaF2 scintillator detectors for lifetime measurements and two HPGe detectors for coincidence Doppler broadening spectroscopy (CDBS) of the annihilation gamma line.

Although a strong correlation between positron lifetime and CDBS line-shape parameters has been demonstrated previously13,55, a quantitative assessment based on CDBS results has not yet been established for complex defects like helium-filled vacancy clusters. This paper therefore focusses primarily on positron lifetime data obtained from different f/m steels irradiated under various conditions and investigated using different PALS setups13,56, while ensuring consistent evaluation through the same analytical model. The evaluation is based on the positive correlation between positron lifetime and vacancy cluster size. However, this correlation is weakened when helium atoms fill the vacancies, as the increasing helium density changes the local electron distribution, specifically by reducing the open volume, which affects positron trapping and annihilation. This paper presents an experimental approach that can overcome the complexity of positron trapping at helium-vacancy clusters using the known helium concentration in the matrix and the previously postulated boundary conditions18.

In addition to the above-described experiment (“Monster” samples), the positron lifetime data obtained from previously published experiments on spallation samples of f/m steels6,13,31 studied with PALS and TEM experimental techniques were used. The summary of all samples and the corresponding irradiation conditions are shown in the Table 5. The combination of TEM and PALS data enabled us to obtain experimental data from which a semi-empirical model was developed, linking positron annihilation variables with key defect characteristics such as cavity radius and the helium-to-vacancy (nHe/nV) ratio.

Aim of a study

Further, it is important to note that the spallation samples contained a non-negligible concentration of transmutation hydrogen, which is known to interact with helium-vacancy clusters, often by promoting the growth and coalescence of He bubbles57,58,59. While the synergistic effect of hydrogen and helium clearly deserves a comprehensive study, the present study focuses on isolating the role of helium. First-principles simulations by Jiang et al.60 demonstrate that although hydrogen atoms may enhance bubble growth, the helium atoms play a significantly more dominant role in initiating and stabilizing vacancy clusters. Their calculations show that He atoms preferentially occupy the center of vacancies and exhibit much stronger trapping energies than H atoms, while H atoms tend to decorate the periphery of existing He-vacancy clusters and have only a secondary effect on their evolution. Moreover, the presence of H was found to have little influence on the trapping behavior of He, whereas He substantially enhances the vacancy’s ability to accommodate H.

In light of these findings, our helium-only approach, enabled by the absence of hydrogen in the Monster samples, provides a simplified but meaningful platform to investigate early-stage helium–vacancy interactions. While we acknowledge that the quantitative characteristics (e.g., cluster sizes and densities) observed in spallation samples may be influenced by H/He synergy, the qualitative mechanisms of cluster nucleation and early evolution remain representative. As such, the present study offers valuable insight into the fundamental processes governing the incubation phase of radiation-induced damage in structural alloys.

Data availability

The relevant data are available from the corresponding authors upon reasonable request.

References

Zinkle, S. J. & Busby, J. T. Structural materials for fission & fusion energy. Mater. Today 12, 12–19 (2009).

Was, G. S., Petti, D., Ukai, S. & Zinkle, S. Materials for future nuclear energy systems. J. Nuclear Mater. 527 (2019).

Zinkle, S. J. & Möslang, A. Evaluation of irradiation facility options for fusion materials research and development. in Fusion Engineering and Design. 88 (2013).

Zinkle, S. J. & Snead, L. L. Designing radiation resistance in materials for fusion energy. Annu. Rev. Mater. Res. 44, 241–267 (2014).

Krsjak, V. et al. Application of positron annihilation spectroscopy in accelerator-based irradiation experiments. Materials 14, 6238 (2021).

Krsjak, V., Kuriplach, J., Vieh, C., Peng, L. & Dai, Y. On the empirical determination of positron trapping coefficient at nano-scale helium bubbles in steels irradiated in spallation target. J. Nucl. Mater. 504, 277–280 (2018).

Stoller, R. E. & Osetsky, Y. N. An atomistic assessment of helium behavior in iron. J. Nucl. Mater. 455, 258–262 (2014).

Osetsky, Y. N. & Stoller, R. E. Atomic-scale mechanisms of helium bubble hardening in iron. J. Nucl. Mater. 465, 448–454 (2015).

Wu, Y., Odette, G. R., Yamamoto, T., Ciston, J. & Hosemann, P. An electron energy loss spectroscopy study of helium bubbles in nanostructured ferritic alloys, fusion reactor materials, semiannual progress report DOE/ER-0313/54. Oak Ridge National Laboratory 173–179 (2013).

Vieh, C. Hardening induced by radiation damage and helium in structural materials. (2015).

Fréchard, S. et al. Study by EELS of helium bubbles in a martensitic steel. J. Nuclear Materials 393, (2009).

Troev, T., Popov, E., Staikov, P. & Nankov, N. Positron lifetime studies of defects in α-Fe containing helium. in Physica Status Solidi (C) Current Topics in Solid State Physics vol. 6 (2009).

Krsjak, V. et al. Helium behavior in ferritic/martensitic steels irradiated in spallation target. J. Nucl. Mater. 456, 382–388 (2015).

Noga, P. et al. High-fluence multi-energy ion irradiation for testing of materials. Materials 15, 6443 (2022).

Hosemann, P. Developing Ultra-Small Scale Mechanical Testing Methods and Microstructural Investigation Procedures for Irradiated Materials. https://www.osti.gov/servlets/purl/1432446 (2018).

Jia, X. & Dai, Y. Microstructure in martensitic steels T91 and F82H after irradiation in SINQ Target-3. J. Nucl. Mater. 318, 207–214 (2003).

Sencer, B. H., Garner, F. A., Gelles, D. S., Bond, G. M. & Maloy, S. A. Microstructural evolution in modified 9Cr–1Mo ferritic/martensitic steel irradiated with mixed high-energy proton and neutron spectra at low temperatures. J. Nucl. Mater. 307–311, 266–271 (2002).

Krsjak, V. et al. On the helium bubble swelling in nano-oxide dispersion-strengthened steels. J. Mater. Sci. Technol. 105, 172–181 (2022).

Giebel, D. & Kansy, J. LT10 program for solving basic problems connected with defect detection. Phys. Procedia 35, 122–127 (2012).

Selim, F. A. Positron annihilation spectroscopy of defects in nuclear and irradiated materials- a review. Mater. Charact. 174, (2021).

Zhu, X., Li, X. & Zheng, M. Predicting the irradiation swelling of austenitic and ferritic/martensitic steels, based on the coupled model of machine learning and rate theory. Metals 12, (2022).

Klueh, R. L. Analysis of swelling behaviour of ferritic/martensitic steels. Philos. Mag. 98, 2618–2636 (2018).

Garner, F. A., Toloczko, M. B. & Sencer, B. H. Comparison of swelling and irradiation creep behavior of fcc-austenitic and bcc-ferritic/martensitic alloys at high neutron exposure. J. Nucl. Mater. 276, (2000).

Krause-Rehberg, R. & Leipner, H. S. Positron Annihilation in Semiconductors Defect Studies. (Springer Berlin Heidelberg, 1999).

Troev, T., Markovski, A., Peneva, S. & Yoshiie, T. Positron lifetime calculations of defects in chromium containing hydrogen or helium. J. Nucl. Mater. 359, 93–101 (2006).

Eldrup, M. & Jensen, K. O. Positron trapping rates into cavities in Al: temperature and size effects. Phys. Status Solidi (a) 102, 145–152 (1987).

Morishita, K., Sugano, R., Wirth, B. D. & Diaz de la Rubia, T. Thermal stability of helium-vacancy clusters in iron. Nucl. Instrum. Methods Phys. Res B 202, 76–81 (2003).

Čížek, J. Characterization of lattice defects in metallic materials by positron annihilation spectroscopy: a review. J. Mater. Sci. Technol. 34, 577–598 (2018).

Robles, C. & Plazaola. Collection of data on positron lifetimes and vacancy formation energies of the elements of the periodic table. Defect Diffus. Forum 213–215, 141–236 (2003).

Ukai, S., Hirade, T. & Okubo, N. Positron annihilation lifetime spectroscopy of FeCr and FeCrAl oxide dispersion strengthened (ODS) alloys. Mater. Charact. 211, 113813 (2024).

Dai, Y., Krsjak, V., Kuksenko, V. & Schäublin, R. Microstructural changes of ferritic/martensitic steels after irradiation in spallation target environments. J. Nucl. Mater. 511, 508–522 (2018).

Zhu, S. et al. Positron annihilation lifetime spectroscopy on heavy ion irradiated stainless steels and tungsten. in J. Nucl. Mater. 343 (2005).

Sato, K. et al. Positron annihilation lifetime measurements of He-ion-irradiated Fe using pulsed positron beam. J. Phys. Conf. Ser. 262, 012053 (2011).

Nieminen, R. M. & Laakkonen, J. Positron trapping rate into vacancy clusters. Appl. Phys. 20, 181–184 (1979).

McMullen, T. The effect of positron-phonon scattering on positron trapping at defects in metals: Formalism and low-order theory. J. Phys. F Metal Phys. 7 (1977).

McMullen, T. The effect of positron-phonon scattering on positron trapping at defects in metals: Solution for strong trapping. J. Phys. F Metal Phys. 8 (1978).

Nieminen, R. M., Laakkonen, J., Hautojärvi, P. & Vehanen, A. Temperature dependence of positron trapping at voids in metals. Phys. Rev. B 19, 1397–1402 (1979).

Mantl, S., Kesternich, W. & Triftshäuser, W. Defect specific temperature dependence of positron trapping. J. Nucl. Mater. 69–70, 593–595 (1978).

Bentzon, M. D., Linderoth, S. & Petersen, K. No Title. in Proc. 7th Internat. Conf. Positron Annihilation (eds. Jain, P. C., Singru, R. M. & Gopinathan, K. P.) 485 (World Scientific, Singapore, 1985).

Schultz, P. J., Lynn, K. G., MacKenzie, I. K., Jean, Y. C. & Snead, C. L. Temperature dependence of the positron annihilation characteristics in molybdenum containing voids. Phys. Rev. Lett. 44, 1629–1632 (1980).

Shi, J., Li, L., Peng, L., Gao, F. & Huang, J. Atomistic study on helium-to-vacancy ratio of neutron irradiation induced helium bubbles during nucleation and growth in α-Fe. Nucl. Mater. Energy 26, 100940 (2021).

Krsjak, V., Degmova, J., Sojak, S. & Slugen, V. Effects of displacement damage and helium production rates on the nucleation and growth of helium bubbles–positron annihilation spectroscopy aspects. J. Nucl. Mater. 499, 38–46 (2018).

Krsjak, V., Degmova, J., Veternikova, J. S., Yao, C. F. & Dai, Y. Experimental comparison of the (ODS)EUROFER steels implanted by helium ions and irradiated in spallation neutron target. J. Nucl. Mater. 523 (2019).

Stoller, R. E. et al. On the use of SRIM for computing radiation damage exposure. Nucl. Instrum. Methods Phys. Res B 310, 75–80 (2013).

Li, W. et al. Enhancement of hydrogen embrittlement resistance in 310S austenitic stainless steel through ribbon-like δ-ferrite. Corros. Sci. 233, 112086 (2024).

Cheik Njifon, I. & Torres, E. Effect of grain boundaries on the helium degradation mechanisms of alloy 800H: a molecular dynamics study. J. Nucl. Mater. 603, 155395 (2025).

Dai, C., Wang, Q., Prudil, A., Li, W. & Walters, L. Radiation-induced segregation at grain boundaries of alloy 800H: experimentally-informed atomistic simulations. J. Nucl. Mater. 579, 154395 (2023).

Chen, J., Jung, P., Pouchon, M. A., Rebac, T. & Hoffelner, W. Irradiation creep and precipitation in a ferritic ODS steel under helium implantation. J. Nucl. Mater. 373, 22–27 (2008).

Zhang, L. et al. Silicon enhances high temperature oxidation resistance of SIMP steel at 700 °C. Corros Sci. 167 (2020).

Lan, Y. et al. Synergies between H and He in advanced F/M steels for fusion reactors and spallation target. J. Nucl. Mater. 613, 155849 (2025).

Roldán, M. et al. Comparative study of helium effects on EU-ODS EUROFER and EUROFER97 by nanoindentation and TEM. J. Nucl. Mater. 460 (2015).

Lindau, R. et al. Present development status of EUROFER and ODS-EUROFER for application in blanket concepts. Fusion Eng. Des. 75–79, 989–996 (2005).

Noga, P. et al. A new ion-beam laboratory for materials research at the Slovak University of Technology. Nucl. Instrum. Methods Phys. Res. B 409, 264–267 (2017).

Saro, M., Krsjak, V., Petriska, M. & Slugen, V. On the characterization of small-scale samples using radioisotope positron sources. Acta. Phys. Pol. A 137, (2020).

Krsjak, V. et al. Positron annihilation study of the reactor pressure vessel model steels irradiated in the high flux reactor. J. Nucl. Mater. 584 (2023).

Petriska, M., Sojak, S., Kršjak, V., Degmová, J. & Slugeň, V. Combined triple coincidence positron lifetime and coincidence Doppler broadening measurement setup. in AIP Conference Proceedings vol. 2778 (2023).

Hu, W. et al. Synergistic effect of helium and hydrogen for bubble swelling in reduced-activation ferritic/martensitic steel under sequential helium and hydrogen irradiation at different temperatures. Fusion Eng. Design 89 (2014).

Kim, S. et al. Synergistic effect of he and h on the surface swelling of ion-implanted Ti/Ta-added reduced activation ferritic/martensitic steel for fusion reactors. J. Korean Phys. Soc. 77 (2020).

Lee, E. H., Hunn, J. D., Rao, G. R., Klueh, R. L. & Mansur, L. K. Triple ion beam studies of radiation damage in 9Cr–2WVTa ferritic/martensitic steel for a high power spallation neutron source. J. Nucl. Mater. 271–272, 385–390 (1999).

Jiang, S. et al. Synergistic effect of helium and hydrogen for vacancy-like defects in pure Fe and Fe9Cr alloy. J. Nucl. Mater. 588 (2024).

Ziegler, J. F., Ziegler, M. D. & Biersack, J. P. SRIM–the stopping and range of ions in matter (2010). Nucl. Instrum. Methods Phys. Res B 268, 1818–1823 (2010).

Acknowledgements

The authors disclose support for the research of this work from the Slovak Research and Development Agency (grant No. APVV-20-0010), and from the Scientific Grant Agency of the Ministry of Education, Science, Research and Sport of the Slovak Republic and the Slovak Academy of Sciences (VEGA grants No. 1/0558/24, 1/0511/25, and 1/0471/25). The authors also disclose support for this work from the European Union projects INNUMAT (No. 101061241) and DELISA-LTO (No. 101061201), and from the EU NextGenerationEU through the Recovery and Resilience Plan for Slovakia (project No. 09I01-03-V04-00033).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

The study was conceived by V.K., J.D., and Y.S. Sample preparation, experimentation, and data acquisition were carried out by S.S., M.P., and B.S. The irradiation experiment, including theoretical simulations of the implantation profiles, design of the target holder, and beamline support, was carried out by P.N., M.K., and D.V. Data analysis and interpretation were performed by Y.S., V.L., I.N., and T.S., under the supervision of V.K. The first draft was prepared by V.K. and Y.S. and revised by all authors; the final revision was conducted by V.K. and V.L. All authors approved the submitted version of the manuscript. Funding acquisition and resources were secured by V.K., P.N., T.S., and V.S.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Kršjak, V., Song, Y., Lučanská, V. et al. Understanding early-stage radiation damage in nuclear alloys through positron annihilation and semi-empirical modeling. npj Mater Degrad 9, 82 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41529-025-00620-8

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41529-025-00620-8