Abstract

The corrosion behavior of B4C/6061Al in spent nuclear fuel (SNF) storage environments was investigated in H3BO3 solutions (0–10,000 ppm) at temperatures ranging from 20 °C to 90 °C by using experimental and computational approaches. The results reveal that dispersed B4C particles act as cathodes, accelerating the dissolution of the aluminum matrix rather than causing localized trench formation. In deionized water, a dual-layered protective corrosion product film forms, consisting of an inner γ-AlOOH layer and an outer Al(OH)3 layer. H3BO3 dissolves both the aluminum matrix and its corrosion products in the following order: Al(OH)3 > γ-AlOOH > aluminum matrix, with increasing effect at higher concentrations. Elevated temperatures enhance both the formation of corrosion products and the dissolution rate by H+. Overall, the results suggest that B4C/6061Al exhibits high corrosion resistance in deionized water (BWR conditions) but suffers significant degradation in H3BO3-containing pools (PWR conditions).

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

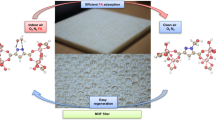

B4C/Al metal matrix composites (MMCs), which are ideal materials for absorbing neutrons, have received considerable attention in recent decades1. Boron carbide (B4C) is used as a promising reinforcement phase for MMCs due to its favorable properties, including a high melting point (2450 °C), high hardness (3700 Hv), high stiffness (445 GPa), low density (2.52 g/cm3), and excellent neutron absorption capacity2,3. The ability of B4C to capture thermal neutrons is attributed to a large thermal neutron cross section (3838.1 b) of the 10B isotope4. Aluminum alloys are commonly chosen as matrix materials in MMCs due to their mechanical properties and excellent corrosion resistance5,6. The powders of the two materials can be easily and evenly blended, avoiding the problem of sedimentation during the condensation process of the materials. As a result, B4C/Al MMCs are used in the manufacture of SNF pool storage racks, which are submerged in a mildly corrosive pool filled with deionized water for boiling water reactors (BWR) and boric acid (H3BO3) solution for pressurized water reactors (PWR), respectively7. Given the importance of the safety of SNF storage, the stability of the materials should be thoroughly considered.

In the long-term service process, the corrosion behavior of B4C/Al MMCs significantly affects the stability of the materials. Previous investigations have been conducted by numerous researchers to study the corrosion behavior of B4C/Al MMCs in H3BO3 solutions with different concentrations. A protective Al(OH)3 corrosion product film formed in dilute H3BO3 solutions, while the conditions to form a stable corrosion product film in concentrated solutions were more difficult to reach8. The corrosion product Al(OH)3 acts as a physical barrier between the material surface and the solution9. The concentration of H+ in the solution controls the dissolution and formation of corrosion products10. The corrosion resistance of B4C/Al MMCs decreases as the volume fraction of B4C particles increases11. This is mainly because the introduction of B4C particles disrupts the continuity of the matrix surface oxide film, leading to preferential corrosion at the interface between the matrix and the reinforcement12,13. B4C particles exhibit a cathodic behavior in the micro-galvanic corrosion of the matrix and the reinforcement, which can accelerate the dissolution of the matrix14, and even cause the particles to peel off from the matrix15,16. Notably, despite these insights, the current understanding still lacks a quantitative description of the degree of micro-galvanic corrosion and explicit elaboration on the specific impacts generated by micro-galvanic effects. In addition, the solution temperature is an important factor affecting the corrosion behavior of B4C/Al MMCs, which has been ignored in previous studies. The role and mechanisms by which temperature affects the corrosion behavior of B4C/Al MMCs are still unclear. In SNF pools, the temperature is intricately related to the various stages and potential scenarios of the storage environment. Prior to the transfer of SNF to the pool, the temperature is at room temperature. After the SNF is settled in the storage pool, neutron-absorbing materials are exposed to complex service conditions such as massive doses of gamma radiation as well as lower levels of fast neutron radiation. Typically, the heat generated by absorbing thermal neutrons raises the storage pool temperature to 40–60 °C17, which reflects the operational temperature regime that the materials are expected to endure during routine storage. In the event of a malfunction, for instance, a failure within the cooling system, the SNF pool temperature may escalate to 90 °C18. Therefore, to explore the combined influence of the temperature and H3BO3 concentration on the corrosion behavior of B4C/Al MMCs is of utmost importance.

In this study, the corrosion behavior of B4C/6061Al in deionized water and H3BO3 solutions at different concentrations and temperatures has been investigated. The samples obtained from the immersion tests were characterized with respect to weight change, surface morphology, composition, and relative amount of the corrosion products detected. The electrochemical properties after sample immersion were analyzed by conducting electrochemical measurements. The micro-galvanic effect between particles and matrix was explored by experimental and modeling studies. Finally, the influence of H3BO3 concentration and temperature on the corrosion behavior of B4C/6061Al was discussed.

Results

Microstructure of B4C/6061Al

Figure 1 displays the surface morphology as obtained with scanning electron microscopy (SEM), together with particle size distribution and energy dispersive spectroscopy (EDS) analyses of the B4C/6061Al sample before immersion. Micrometer-sized B4C particles, in irregular shapes, are distributed in the aluminum matrix as the reinforcement phase (Fig. 1a). According to the particle size distribution analysis (Fig. 1b), the B4C particle size is in the range from 0 to around 14 μm and exhibits a mean particle size of 5 μm. The area in Fig. 1a was selected for further EDS analysis (Fig. 1c). The results show that in addition to B4C particles, the aluminum matrix contains magnesium (Mg) and silicon (Si). These elements could originate from β-Mg2Si, which is commonly present in the 6xxx series alloys19. However, particles of this phase were not observed at the current magnification. It can also be observed that oxygen (O) is only detected on the aluminum matrix surface, indicating that the presence of B4C particles disrupts the continuity of the oxide film formed in air at ambient temperature. This discontinuous oxide film, however, may still play a certain protective role.

Weight change

All samples were immersed in various H3BO3 solutions (0, 500, 2500, 5000, 10,000 ppm) at 20 °C, 50 °C, and 90 °C, respectively, with a duration of 1440 h. Figure 2 displays the weight changes per unit area of the B4C/6061Al samples after immersion. The error bars are the result of triplicate measurements. The weight changes observed in the samples are attributed to the dynamic balance between the formation rate of the corrosion products and the dissolution rate of the aluminum matrix9. For the samples immersed at 20 °C, weight-gains are observed when the H3BO3 concentration is equal to or below 500 ppm. At 50 °C, the weight-losses are only seen at 10,000 ppm. At 90 °C, there is no weight-loss observed for any sample. Obviously, weight-gains are more likely observed as temperature increases, suggesting that the formation of corrosion products is favored by increased temperature. In 10000 ppm H3BO3 solution, the weight loss at 50 °C is equal to or only slightly larger than at 20 °C. As the H3BO3 concentration increases, the weight-gains of the sample shows a decreasing trend. There is little change in the observed weight losses with temperature, which indicates that H3BO3 can dissolve the formation of corrosion products, but exerts little effect on the dissolution rate of the aluminum matrix.

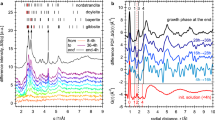

Grazing incidence X-ray diffraction (GIXRD) analysis

GIXRD was performed to identify the corrosion products formed on the samples with weight-gains. Figure 3 displays the GIXRD spectra of the B4C/6061Al samples after immersion. Based on the results of the indexing of diffraction peaks, it is found that the investigated surface region after exposure in deionized water and in solutions with lower H3BO3 concentration mainly consists of the aluminum matrix, B4C particles, and the corrosion products γ-AlOOH and Al(OH)3. At higher H3BO3 concentration, only γ-AlOOH remains in the corrosion products.

To better investigate the relative amount of each phase in the corrosion products, the results were calculated by FullProf Rietveld refinement20 in samples with observed weight gain. All values of the weighted profile factor (Rwp) were below 6.12 (The value of Rwp should be below 10 for satisfactory results21). The percentage of the detected γ-AlOOH and Al(OH)3 in the corrosion products was calculated, and the results are shown in Fig. 4. In deionized water, the relative amount of γ-AlOOH is the highest at 90 °C compared with that at 20 °C and 50 °C (Fig. 4). In H3BO3 solutions, γ-AlOOH is the dominating compound in all corrosion products formed in all samples. Especially at higher H3BO3 concentrations, the corrosion products only consist of γ-AlOOH. Therefore, the ability of H3BO3 to dissolve already existing Al(OH)3 is stronger than its ability to dissolve γ-AlOOH.

Microstructure of B4C/6061Al after immersion

Figure 5 displays the morphologies on the sample surface after immersing in deionized water. In 20 °C solution, two types of corrosion products are distributed on the sample surface (Fig. 5a). One has a flat surface with cracks, while the other exhibits a granular stacked shape. At 50 °C and 90 °C, only granular stacked corrosion products were observed (Fig. 5b and c). In deionized water, the thin oxide film reacts with water and disruption of Al-O-Al bonds occurs via hydrolysis reaction to form the Al-OH species γ-AlOOH and Al(OH)322:

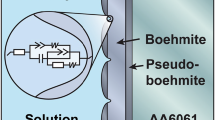

Therefore, in combination with GIXRD analysis and surface morphologies, it can be deduced that the corrosion products consist of a two-layer structure with an outer layer of granular stacked Al(OH)3 and an inner layer of γ-AlOOH. This two-layer structure is clearly evident in the cross-sectional SEM images (Supplementary Fig. 1–3).

Figure 6 displays the morphologies on the sample surface after immersion in H3BO3 solutions. The morphologies after immersion in 20 °C solutions are shown in Fig. 6a–d. Only a dense layer of rippled corrosion products was observed in 500 ppm H3BO3 (Fig. 6a). No visible corrosion products were observed in H3BO3 concentrations higher than 2500 ppm (Fig. 6b–d), and the surface is rougher compared to that before immersion due to the aluminum matrix dissolution.

Figure 6e–h show the morphologies of the samples after immersion in 50 °C solutions. At 500 ppm H3BO3 solution, the sample surface is covered with granular stacked corrosion products (Fig. 6e). The rippled corrosion products were observed in 2500 ppm and 5000 ppm H3BO3 solutions (Fig. 6f, g). It is worth noting that obvious corrosion effects can be observed only at 10,000 ppm H3BO3 solution (Fig. 6h), where the surrounding of B4C particles is exposed and the aluminum matrix has been significantly dissolved.

At 90 °C, all samples are completely covered by corrosion products of different nature (Fig. 6i–l). At 500 ppm (Fig. 6i), the surface is covered densely with rippled corrosion products, and the sample surface also retains polyhedral granular corrosion products and a few flocculent corrosion products. When the H3BO3 concentration exceeds 2500 ppm, the polyhedral corrosion products disappear, and only a dense layer of corrosion products can be seen (Fig. 6j–l).

In all, samples immersed in H3BO3 solutions show three morphological features (Fig. 6): granular corrosion products that accumulate or disperse on the surface, densely rippled corrosion products, and sample surfaces with no obvious corrosion products. Combining GIXRD analysis and surface morphologies, it can be concluded that the granular corrosion products consist of Al(OH)3, and the densely rippled corrosion products consist of γ-AlOOH.

Confocal laser scanning microscopy (CLSM) analysis

The topography and morphology of samples after immersion for 1440 h were analyzed with CLSM. Distinct pore formation was only observed in 10000 ppm H3BO3 at 50 °C. Figure 7a exhibits the variation in height of the corroded sample surface, where the depth of the pore region is significantly deeper than the average depth of other surface features. Figure 7b depicts the morphology of the corroded sample surface, showing that a pore appears at the vicinity of a B4C particle. Looking at the size of the pore (approximately 10 µm in diameter and 7 µm in depth), its formation may be caused by the detachment of a B4C particle rather than a trenching effect. Trench formation is considered as a common phenomenon that may occur around secondary phases due to galvanic corrosion effects23. To investigate the trench effect around B4C particles in more detail, the height profiles along the red lines in Fig. 7a were deduced. The depth of trenches around the B4C particles investigated (typically a few tenths of micrometers) is less than the depth of the aluminum matrix dissolution (around 3 to 5 micrometers, Fig. 7), which suggests that trench effects are weak (less than 10% of the total dissolution under present exposure conditions).

Atomic force microscopy (AFM) and scanning Kelvin probe force microscopy (SKPFM) analysis

Figure 8 shows a topographic map of B4C particles embedded in the aluminum matrix, and the corresponding surface Volta potential distribution. In this test, the Volta potential was measured by applying a bias potential to the sample. The Volta potential difference \(\triangle \Phi\) can be defined relative to the tip bias as follows24:

where \({\Phi }_{{sample}}\) and \({\Phi }_{{tip}}\) are the work functions of the sample and the conducting tip, respectively, and \(e\) is the electronic charge. Based on the definition of concepts involved in this equation, a higher Volta potential difference indicates a higher work function of the sample, corresponding to a higher nobility. Hence, Fig. 8b suggests that the B4C particle phase is more noble than the surrounding matrix, with a potential difference of approximately 230 mV (Fig. 8c). It is generally believed that the potential difference between the reinforcement phase and the aluminum matrix is the driving force for micro-galvanic corrosion25. The potential difference between the B4C particles and the aluminum matrix would suggest that micro-galvanic corrosion tends to occur at the periphery of B4C particles, where the aluminum matrix will act as an anode and is prone to be preferentially corroded due to the micro-galvanic effect.

Electrochemical characterization

To gain a deeper understanding of the electrochemical properties of immersed B4C/6061Al in deionized water and H3BO3 solutions under different temperature conditions, potentiodynamic polarization measurements were conducted and the results are displayed in Fig. 9. Table 1 presents the electrochemical parameters derived from potentiodynamic polarization curves, along with the corresponding corrosion products identified by GIXRD at the same conditions. It is seen that the corrosion potential, Ecorr, of the sample with a single layer of corrosion product exhibits a positive shift compared to that of the sample without corrosion products. This is due to the fact that the corrosion product film alters the electrochemical nobility of the material surface and decreases the likelihood of corrosion. When two layers of corrosion products are present, the Ecorr may shift slightly more positively, signifying that the second layer of corrosion product further enhances the electrochemical nobility, making it more difficult for the material to undergo a corrosion reaction. Similarly, the corrosion current density, icorr, of the sample with corrosion products is lower than that of the sample without corrosion products. When one layer of corrosion product forms on the sample surface, icorr decreases compared to without corrosion product. This reduces the exposed area of the metal matrix and the corrosive medium, and thus slows down the corrosion apparently. When there are two layers of corrosion products, icorr decreases further, indicating that the two layers of corrosion products offer enhanced protection and further decelerate the corrosion rate. In particular, even if there is a layer of corrosion products on the surface, such as in a 10,000 ppm H3BO3 solution at 90 °C, it will lead to a dramatic decrease in Ecorr and a significant increase in icorr.

In all, potentiodynamic polarization curves suggest that the presence and nature of corrosion product layers significantly influence the corrosion resistance of B4C/6061Al. Samples with a single layer of γ-AlOOH exhibit relatively limited corrosion resistance, while samples with two layers of corrosion products, γ-AlOOH and Al(OH)3, show a higher corrosion resistance. In contrast, samples without stable corrosion products exhibit more negative Ecorr and higher icorr, and a higher susceptibility to corrosion.

Discussion

In what follows, the results presented are discussed in some detail. The discussion particularly focuses on the influence of H3BO3 concentration on the corrosion effect of the investigated B4C/Al metal matrix composite. Additionally, the effect of temperature is examined. Finally, the combined effect of H3BO3 concentration and temperature is also taken into account. A complicating factor is the presence of B4C particles and concomitant micro-galvanic or galvanic effects. This issue is treated in the first section below, from which is evident that the overall micro-galvanic effects can be regarded as relatively large. However, no visible trenching or other localized corrosion effects around B4C particles are observed. Instead, the micro-galvanic effects result in an evenly distributed general corrosion enhancement along the whole aluminum matrix in between the B4C particles. Hence, the remaining sections focus exclusively on the influence of temperature and H3BO3 concentration on the aluminum matrix, rather than their effects on micro-galvanic corrosion.

To explain the temperature dependence of an acid, such as H3BO3, one needs to consider the activity of the dissociated protons through changes in the ionization equilibrium of the acid with temperature26. Based on the Einstein-Smoluchowski diffusion relationship27, an increased temperature also favors the mobility of protons from the acid toward the oxide. Other important temperature-dependent factors to consider are the growth rate of corrosion products, mainly γ-AlOOH and Al(OH)3, and the ability of protons to dissolve these compounds, both of which are expected to increase with temperature28,29. The overall temperature dependence of the corrosion effect is then the net effect of formation rates and dissolution rates at each exposure condition.

SKPFM results show that there is a potential difference between B4C particles, acting as cathode, and the surrounding aluminum matrix, acting as anode (Fig. 8), which becomes the driving force for micro-galvanic corrosion. This micro-galvanic effect may aggravate the corrosion of the matrix around the particles, leading to the formation of local trenches9. However, distinct pore formation was only observed once at the interface between B4C particles and the aluminum matrix, in 10,000 ppm H3BO3 at 50°C (Fig. 8). In all, CLSM observations and analysis confirm that trench formation is minimal, suggesting that the pore formation in this particular case may be related to the detachment of B4C particles, rather than trench formation.

To further substantiate this point and predict a possible micro-galvanic effect and trenching corrosion tendency, a finite element method (FEM) modeling and simulation study was conducted based on single-phase potentiodynamic polarization curve data of B4C particles and the aluminum matrix obtained under the same condition (10,000 ppm H3BO3 concentration at 50 °C, Fig. 10a). In this model, three different B4C particle distributions were investigated (Fig. 10b), i.e., three aggregated particles, two aggregated particles, and a single particle separated from other particles. The simulation results reveal that the corrosion current density of the aluminum matrix is the largest among the three aggregated particles (Fig. 10c). However, the variation in corrosion current density across the entire aluminum matrix surface is less than 0.08%, which is negligibly small. Nevertheless, compared with the free corrosion situation of the aluminum matrix (1.7 × 10−7 A/cm2, obtained from the potentiodynamic polarization curve of the aluminum matrix in Fig. 10a), the corrosion current density of the aluminum matrix with micro-galvanic effects triggered by B4C particles is one order of magnitude higher than without B4C particles (Fig. 10c).

To conclude, the introduction of B4C particles into the aluminum matrix accelerates the corrosion rate of the entire aluminum matrix rather than in visible trench formation at the B4C/matrix interface.

In deionized water, the corrosion products on the sample surface have a two-layer structure with an outer layer of granular stacked Al(OH)3 and an inner layer of γ-AlOOH (Fig. 5), with excellent corrosion resistance (Table 1). When the solution contains a low amount of H3BO3, the Al(OH)3 in the outer layer reacts with H+ produced by the ionization of H3BO3, resulting in a decrease in the relative amount of Al(OH)3 on the sample surface (Fig. 4 and reaction (4) below). As the H3BO3 concentration continues to increase, more Al(OH)3 dissolves until eventually only γ-AlOOH remains. As the H3BO3 concentration increases further, also γ-AlOOH dissolves (reaction (5)), after which the dissolution of the aluminum matrix starts (reaction (6)).

The evolution in corrosion products during this process is also evident in the cross-sectional morphology (Supplementary Fig. 1–3) and the thickness changes of corrosion products on the sample (Supplementary Fig. 4). Combined with the GIXRD analysis results (Fig. 3), the cross-sectional SEM images (Supplementary Fig. 1–3) reveal that as the H3BO3 concentration increases, the distinct thick Al(OH)3 and γ-AlOOH corrosion products gradually become thin γ-AlOOH corrosion products. The thin γ-AlOOH corrosion products cannot be clearly defined in terms of thickness based on the distribution of Al and O elements in the EDS mapping. Along with the more intuitive glow discharge optical emission spectroscopy (GDOES) analysis results (Supplementary Fig. 4), it is evident that the thickness of corrosion products exhibits a decreasing trend with an increase in H3BO3 concentration.

For all investigated temperatures, the relative amount of Al(OH)3 on the sample surface at 500 ppm H3BO3 is less than that in deionized water, and Al(OH)3 is no longer present at higher H3BO3 concentrations, where only γ-AlOOH exists (Fig. 4). The difference in dissolution behavior of Al(OH)3 and γ-AlOOH in the presence of H3BO3 can be attributed to their inherent thermodynamic stabilities. According to solubility studies, the equilibrium constant for the dissolution of Al(OH)3 is 7.76 ± 0.14, while that of γ-AlOOH is 7.49 ± 0.09, suggesting that γ-AlOOH is thermodynamically more stable than Al(OH)3 under standard condition (298 K, 1 atm). Hence, the ability of H3BO3 to dissolve Al(OH)3 is stronger than to dissolve γ-AlOOH.

When the aluminum matrix surfaces dissolve, especially at 20 °C, the corresponding weight-losses do not change significantly with H3BO3 concentration (Fig. 2), suggesting that a change in H3BO3 concentration has no significant effect on the dissolution rate of the aluminum matrix at 20 °C.

To conclude, H3BO3 is able to dissolve the aluminum matrix and corrosion products on B4C/6061Al, mainly Al(OH)3 and γ-AlOOH, with rates that depend on the actual exposure conditions. The variation in H3BO3 concentration exhibits no significant influence on the dissolution of the aluminum matrix at low temperature, yet it exerts a substantial effect on the dissolution of corrosion products across all temperature conditions.

The weight loss of the samples is attributed to the dissolution rate of the aluminum matrix when exceeding the formation rate of the corrosion products. At 10,000 ppm H3BO3, the weight-loss of the sample at 50 °C is equal to or slightly higher than that at 20 °C (Fig. 2), which indicates that temperature may have a weak accelerating effect on the dissolution of the aluminum matrix at this H3BO3 concentration.

At any given H3BO3 concentration, the samples usually tend to gain weight with increasing temperature (Fig. 2). The dominating corrosion products on the samples characterized by weight-gains is γ-AlOOH (Fig. 4), in particular at higher concentrations and temperatures. Evidently, γ-AlOOH is more stable at high temperatures than Al(OH)3. This is in accordance with the thermodynamic results based on the software HSC chemistry 6.030, where Gibbs free energy changes and equilibrium constants of the inverse reaction (7) of the reaction (2) decrease and increase with temperature (Fig. 11), respectively. Hence, both immersion tests and thermodynamic results show that the reaction

is favored by increasing temperature.

To conclude, the effect of solution temperature on the corrosion behavior of B4C/6061Al is mainly to promote the formation rate of both Al(OH)3 and γ-AlOOH, and secondly the ability of protons to dissolve corrosion products and the aluminum matrix in the following order: Al(OH)3 > γ-AlOOH > aluminum matrix.

The concentration of H3BO3 and solution temperature not only separately affect the corrosion behavior of B4C/6061Al, but also in combination. At any given H3BO3 concentration there is a dual influence of temperature: on one hand to promote the transformation of Al(OH)3 to γ-AlOOH, on the other hand to increase the proton activity through enhanced acid dissociation promoting the ability of protons to dissolve the solid phases in the order Al(OH)3 > γ-AlOOH > aluminum matrix. These two opposite effects, one resulting in mass gain and the other in mass loss, change with temperature so that the overall effect is either a net mass gain or a net mass loss. At any given temperature, the mass gain is highest at the lowest H3BO3 concentration and then decreases with concentration (Fig. 2). At 20 °C, a mass gain is observed up to 500 ppm H3BO3, after which slight mass losses are observed independent of H3BO3 concentration. At 50 °C, mass gains are observed up to 5000 ppm, and mass losses only at 10,000 ppm. At 90 °C mass gains are observed at all concentrations.

Finally, these experimental results may give guidelines for practical implications. B4C/6061Al for SNF in deionized water pool storage (BWR) is protected by corrosion products and thus exhibits a relatively high corrosion resistance. In contrast, B4C/6061Al for storage of SNF in H3BO3-containing pools (PWR) may corrode under the combined effect of H3BO3 concentration and solution temperature. An excessively high H3BO3 concentration, such as 10000 ppm, makes the formation of protective corrosion products unlikely and is not recommended for any application. In addition, surface treatments such as shot peening and anodizing should be carried out in advance to mitigate corrosion. Finally, it is worth noting that the above conclusions have been drawn based on 1440 h (2 months) immersion tests, which is still a short period compared with the expected total lifetime of the pool storage facility. Much longer term of immersion data is necessary to obtain more realistic corrosion trends of the B4C/6061Al composite.

Methods

Sample preparation

The B4C/6061Al samples used in this study were commercially obtained from Zhenjiang Huahe Equipment Co., Ltd., China. The chemical compositions of B4C powders and 6061Al are given in Tables 2 and 3, respectively. The 6061Al powders and 31 wt.% B4C powders were blended evenly at the beginning of powder metallurgy. The blended powders were subjected to shaping, sintering, forging, hot rolling, and annealing. After this process, B4C/6061Al plates of 2.7 mm thickness were cut into standard-size coupons (50 mm × 25 mm) using a laser cutting machine. All as-received samples were subjected to surface pickling treatment. In order to reduce the effect of surface pickling, the as-received samples were successively abraded with 400–2000 grit SiC paper and polished with 0.5 μm diamond paste.

Immersion tests

The immersion tests were carried out for a period of 1440 h in deionized water and in solutions of different H3BO3 concentrations (500, 2500, 5000, and 10,000 weight-ppm) at temperatures of 20 °C, 50 °C and 90 °C, respectively. The measured solution pH values are listed in Table 4. The inclusion of deionized water and the 10,000 ppm H3BO3 solution aimed to simulate the actual composition of SNF pools in BWR and PWR, respectively. The selection of other H3BO3 concentrations was based on values used in relevant studies17. The experimental temperatures were chosen to reflect different stages and potential scenarios within the material’s service environment. Prior to immersion, all B4C/6061Al samples were degreased with ethanol, rinsed with deionized water, and dried using cold air. Each solution was prepared by using analytical-grade reagents and deionized water. The solution volume per square centimeter of sample surface area was more than 20 mL, according to ASTM-G31-2131. The beaker containing the solution was sealed with a customized lid and sealing film to prevent the solution from evaporating. A thermostatic chamber was employed to stabilize the solution temperature with a temperature fluctuation range of –1.0 to 0.5 °C. Before and after immersion tests, the samples were weighed using an analytical balance (METTLER TOLEDO XPR106DUH/AC, Switzerland) with an accuracy of 0.01 mg. To ensure reliability, three parallel samples were employed in the immersion test for each experimental condition.

Surface characterization

Surface morphology of the B4C/6061Al plates before and after immersion tests was observed by SEM (ZEISS MERLIN Compact, Germany) coupled with EDS. The second electron detector was adopted with an accelerating voltage of 20 kV for the electron imaging.

The topography and the corresponding surface Volta potential distribution of the B4C/6061Al sample were mapped with AFM (Bruker Dimension Icon, Germany) and SKPFM before immersion. Prior to testing, each sample was prepared to a size of 10 mm × 10 mm × 2.7 mm, successively abraded with 400–2000 grit SiC paper and polished with 0.5 μm diamond paste. Each sample was then ultrasonically cleaned with ethanol, rinsed with deionized water and finally blow-dried with cold wind. The SKPFM measurements were conducted in ambient air at a temperature of 23 ± 1 °C with relative humidity of 60 ± 1%. The scanning range and pixel resolution were 20 × 20 µm and 256 × 256, respectively. A voltage was applied to the sample to measure the surface potential difference between the sample and the conducting tip.

The composition and microstructure of the corrosion products were analyzed with X-ray diffractometry (Rigaku Corporation, Japan). Since the thickness of the corrosion product layers was in the micrometer range, GIXRD was utilized to obtain a better identification of the surface corrosion products than conventional X-ray diffraction due to its much higher surface sensitivity. The measurements were carried out using Cu Kα radiation (λ = 1.542 Å) for 2θ between 10° and 90°, and the angle of incidence was 4°. FullProf software was used for the Rietveld refinement of diffraction patterns. The pseudo-Voigt function, a linear combination of Gaussian and Lorentzian functions with the same full width at half-maximum (FWHM) values, was employed to obtain the relative amount of corrosion products.

The morphology and topography of the B4C/6061Al plates after immersion were obtained using a CLSM (Olympus LEXT OLS5000, Japan). CLSM uses a 405 nm laser source with a lateral resolution of 0.12 μm. The image information was obtained through the built-in color imaging optical element, and the confocal images were presented by the laser confocal optical element. The depth of corrosion pits was measured via section analysis.

Electrochemical measurements

To explore the corrosion behavior after immersion of the B4C/6061Al samples, electrochemical measurements were conducted by employing an electrochemical workstation (Princeton PARSTAT MC, USA) with a double-layer water bath for the temperature-controlled corrosion cell. The immersed B4C/6061Al sample was the working electrode, a saturated Ag/AgCl electrode the reference electrode, and a Pt sheet the counter electrode. To minimize solution resistance effects, the reference electrode was positioned as close as possible to the working electrode surface, and automatic iR compensation was applied during all measurements using the workstation’s built-in function.

The open circuit potentials (OCP) were measured initially for 3600 s in the test solution to reach a steady state. After the OCP measurements, potentiodynamic polarization curves were obtained by potentiodynamic polarization at a scan rate of 1 mV/s in the potential range from –0.5 V to 1.0 V (vs. OCP). A scan rate of 1 mV/s is chosen both to reduce the removal of the surface film and to minimize the impact of charge transfer32. The experiments were conducted in deionized water and different H3BO3 solutions at temperatures of 20 °C, 50 °C and 90 °C respectively, the same as those conducted in the immersion tests. The temperature was stabilized by circulating external heating water. Three replications for each concentration and temperature were performed to ensure repeatability.

FEM simulation

To follow up the observations of micro-galvanic effects in immersion tests, a 3D mathematical micro-galvanic corrosion model was built based on the Bulter-Volmer equation and a FEM in order to model possible micro-galvanic effects in B4C/6061Al. COMSOL Multiphysics® was used to solve the partial differential equations in this model. A schematic diagram of the governing equations and boundary conditions is shown in Fig. 12. The electrolyte potential \({\varphi }_{l}\) over the electrolyte domain was solved according to:

where \({{\bf{i}}}_{l}\) is the electrolyte current density vector and \({\sigma }_{l}\) is the electrolyte conductivity. The insulation condition for all boundaries was used except for the electrode surface:

where n is the normal vector, pointing out of the domain. The local current density \({i}_{{loc},m}\) was solved according to:

where \({\varphi }_{s}\) is the surface potential of two phases (aluminum matrix and B4C with a diameter of 5 μm). The relationship between local current density\(\,{i}_{{loc},m}\), and electrolyte potential \({\varphi }_{l}\) is experimentally determined by polarization curves of the 6061Al alloy and bulk B4C material performed at 50 °C and 10000 ppm H3BO3 concentration. The electrochemical reactions modeled in the FEM include aluminum dissolution (anodic) reaction and hydrogen evolution (cathodic) reaction, which were identified as the dominant processes based on potentiodynamic polarization tests in argon-deaerated condition12. To simplify the model and save computing resources, the following assumptions have been made in this model: (1) The electrolyte solution is well-mixed, isotropic, and incompressible. (2) The solution is electro-neutral. (3) The diffusion and conviction can be neglected and a constant conductivity of solution can be assumed in the H3BO3 solution. Based on the aforementioned assumptions, the secondary current distribution interface was adopted in the simulation.

Data availability

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

References

Ghayebloo, M., Mostaedi, M. T. & Rad, H. F. A review of recent studies of fabrication of Al-B4C composite sheets used in nuclear metal casks. T. Indian I. Met. 75, 2477–2490 (2022).

Li, Y., Wang, W., Zhou, J., Chen, H. & Zhang, P. 10B areal density: A novel approach for design and fabrication of B4C/6061Al neutron absorbing materials. J. Nucl. Mater. 487, 238–246 (2017).

Wu, C. et al. Influence of particle size and spatial distribution of B4C reinforcement on the microstructure and mechanical behavior of precipitation strengthened Al alloy matrix composites. Mater. Sci. Eng., A 675, 421–430 (2016).

Basturk, M., Kardjilov, N., Lehmann, E. & Zawisky, M. Monte Carlo simulation of neutron transmission of boron-alloyed steel. IEEE T. Nucl. Sci. 52, 394–399 (2005).

Shirvanimoghaddam, K. et al. Boron carbide reinforced aluminium matrix composite: Physical, mechanical characterization and mathematical modelling. Mater. Sci. Eng., A 658, 135–149 (2016).

Behm, N. et al. Quasi-static and high-rate mechanical behavior of aluminum-based MMC reinforced with boron carbide of various length scales. Mater. Sci. Eng. A 650, 305–316 (2016).

Shi, J., Shen, C., Zhang, L., Lei, J. & Long, X. Corrosion mechanism of Al-B4C composite materials in boric acid. Energy Sci. Technol. 46, 972–977 (2012).

Shi, J. et al. Corrosion behavior of Al-B4C composite in spent nuclear fuel storage environments. J. Chin. Soc. Corros. Prot. 33, 419–424 (2013).

Li, Y., Wang, W., Chen, H., Zhou, J. & Wu, Q. Corrosion behavior of B4C/6061Al neutron absorber composite in different H3BO3 concentration solutions. Acta Metall. Sin. (Engl. Lett.) 29, 1037–1046 (2016).

Shi, J., Lei, J., Zhang, L. & Shen, C. Corrosion behaviors of Al-B4C composite materials. Energy Sci. Technol. 44, 159–165 (2010).

Gaylan, Y., Avar, B., Panigrahi, M., Aygün, B. & Karabulut, A. Effect of the B4C content on microstructure, microhardness, corrosion, and neutron shielding properties of Al-B4C composites. Ceram. Int. 49, 5479–5488 (2023).

Han, Y. M. & Chen, X. G. Corrosion characteristics of Al-B4C metal matrix composites in boric acid solution. Mater. Sci. Forum 877, 530–536 (2016).

Hu, J., Chu, W. Y., Fei, W. D. & Zhao, L. C. Effect of interfacial reaction on corrosion behavior of alumina borate whisker reinforced 6061Al composite. Mater. Sci. Eng. A 374, 153–159 (2004).

Ding, H. & Hihara, L. H. Electrochemical examinations on the corrosion behavior of boron carbide reinforced aluminum-matrix composites. J. Electrochem. Soc. 158, C118 (2011).

Zhang, F., Brett Wierschke, J., Wang, X. & Wang, L. Nanostructures formation in Al-B4C neutron absorbing materials after accelerated irradiation and corrosion tests. Microsc. Microanal. 21, 1159–1160 (2015).

Han, H. et al. Revealing corrosion behavior of B4C/pure Al composite at different interfaces between B4C particles and Al matrix in NaCl electrolyte. J. Mater. Res. Technol. 27, 7213–7227 (2023).

Shi, J. et al. Corrosion behaviors of Al-B4C composite materials for BWR reactor spent fuel pool. Prog. Rep. China Nucl. Sci. Technol. 2, 106–111 (2011).

Jung, Y., Lee, Y., Kim, J. H. & Ahn, S. Accelerated corrosion tests of Al-B4C neutron absorber used in spent nuclear fuel pool. J. Nucl. Mater. 552, 153011 (2021).

Zhou, Y. T. et al. Corrosion onset associated with the reinforcement and secondary phases in B4C-6061Al neutron absorber material in H3BO3 solution. Corros. Sci. 153, 74–84 (2019).

Rietveld, H. M. A profile refinement method for nuclear and magnetic structures. J. Appl. Crystallogr. 2, 65–71 (1969).

He, Y. et al. Improved thermal properties and CMAS corrosion resistance of rare-earth monosilicates by adjusting the configuration entropy with RE-doping. Corros. Sci. 226, 111664 (2024).

Kanehira, S. et al. Controllable hydrogen release via aluminum powder corrosion in calcium hydroxide solutions. J. Asian Ceram. Soc. 1, 296–303 (2013).

Li, D., Huang, F., Lei, X. & Jin, Y. Localized corrosion of 304 stainless steel triggered by embedded MnS. Corros. Sci. 211, 110860 (2023).

Örnek, C., Leygraf, C. & Pan, J. On the Volta potential measured by SKPFM - fundamental and practical aspects with relevance to corrosion science. Corros. Eng., Sci. Technol. 54, 185–198 (2019).

Yin, L., Jin, Y., Leygraf, C. & Pan, J. A FEM model for investigation of micro-galvanic corrosion of Al alloys and effects of deposition of corrosion products. Electrochim. Acta 192, 310–318 (2016).

Arcis, H., Ferguson, J. P., Applegarth, L. M. S. G., Zimmerman, G. H. & Tremaine, P. R. Ionization of boric acid in water from 298K to 623K by AC conductivity and Raman spectroscopy. J. Chem. Thermodyn. 106, 187–198 (2017).

Islam, M. A. Einstein-Smoluchowski diffusion equation: a discussion. Phys. Scr. 70, 120–125 (2004).

Nevskaya, E. Y. et al. α-Al(OH)3 dissolution in acid media. Theor. Found. Chem. En. 34, 292–297 (2000).

Palmer, D. A., Bénézeth, P. & Wesolowski, D. J. Aqueous high-temperature solubility studies. I. The solubility of boehmite as functions of ionic strength (to 5 molal, NaCl), temperature (100–290 °C), and pH as determined by in situ measurements. Geochim. Cosmochim. Ac. 65, 2081–2095 (2001).

Roine, A. HSC Chemistry 6.0 (Outotec Research Oy, 2006). www.outotec.com/hsc.

ASTM. ASTM G31-21: Standard Guide for Laboratory Immersion Corrosion Testing of Metals (ASTM, 2021).

Zhang, X. L., Jiang, Z. H., Yao, Z. P., Song, Y. & Wu, Z. D. Effects of scan rate on the potentiodynamic polarization curve obtained to determine the Tafel slopes and corrosion current density. Corros. Sci. 51, 581–587 (2009).

Acknowledgements

This study was supported by China Nuclear Power Engineering Co., Ltd. (No. KY2008-1302).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Bo Zhang (First Author): Conceptualization, Methodology, Formal analysis, Writing-original draft, Investigation. Xin Lei: Resources, Supervision. Feifei Huang: Supervision, Funding acquisition. Hai Chang: Project administration, Funding acquisition. Shi Pu: Validation, Investigation. Ying Jin: Resources, Funding acquisition, Supervision, Writing- Review & Editing. Christofer Leygraf: Writing - Review & Editing.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Zhang, B., Lei, X., Huang, F. et al. Study of the effect of H3BO3 concentration and temperature on the corrosion behavior of B4C/6061Al. npj Mater Degrad 9, 84 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41529-025-00636-0

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41529-025-00636-0

This article is cited by

-

Influence of micro-structure on the corrosion behaviour of glass-bead blasted AA6061-B4C MMC in H3BO3 solution

npj Materials Degradation (2025)