Abstract

The shift toward biomass fuels for heat and power generation has introduced a range of new challenges for power plant technology, in particular large-scale boilers. One major challenge is the corrosion of preheaters and flue gas cleaning equipment, commonly known as low-temperature corrosion. Observations over recent decades show that this form of corrosion aligns more closely with chlorine chemistry than with sulfur chemistry. This review provides an up-to-date survey of the existing literature, with a particular focus on hygroscopic chloride salts that deliquesce and cause corrosion on cold-end surfaces.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Industrial-scale power plants, i.e., boilers that supply district heating, electricity, or process steam, are experiencing advances in boiler efficiency, which, when expressed on a lower heating value (LHV) basis, can in the best case exceed 90%1,2. A significant portion of the energy loss in boiler systems is attributed to the sensible heat carried away by the flue gases released into the atmosphere. Consequently, a primary approach to enhancing boiler efficiency is through flue gas heat recovery3. Typically, lowering the flue gas temperature by about 20 °C can yield a 1% increase in the efficiency of boilers4,5. Within this context, preheaters, economizers, and air preheaters play a central role. Air preheaters are used to recover the heat from the flue gases and typically account for around 10% of boiler efficiency gain4. These units come in two primary types, tubular and rotary, and are normally placed downstream of the economizers6,7. The latent heat can further be recovered using a flue gas condenser.

While lowering flue gas temperatures enhances efficiency, too-low material temperatures can result in new challenges for the power boilers, such as deposit build-up as well as corrosion of the heat transfer tubes and flue gas cleaning equipment8,9,10,11,12,13,14,15,16,17,18,19,20,21,22,23. These challenges have become increasingly complex over the past few decades, as broader adoption of lower-grade fuels and various additives has introduced more contaminants into the flue gases24. In response, operational demands and environmental regulations have become more stringent to mitigate corrosion14,25 and reduce emissions26, necessitating the integration of large flue gas cleaning systems such as electrostatic precipitators (ESP), baghouse filters, selective catalytic or non-catalytic reduction (SCR/SNCR) units, and wet flue-gas-desulfurization (FGD) scrubbers, etc. Consequently, the cold-end zone itself has gradually expanded within the boiler system.

Corrosion occurring in the cold-end zone is commonly known as low-temperature corrosion9,10,11,12,13,14,15,17,18,19,20,21,22,23,27,28,29,30, also referred to as cold-end corrosion11,14,25,31,32 or back-end corrosion27. Low-temperature corrosion may result in costly repairs and unplanned shutdowns23. The affected equipment includes the economizer, air preheater, flue gas cooler, precipitator, flue gas reheater, and various flue gas cleaning equipment23,33,34.

Low-temperature corrosion in biomass boilers is predominantly attributed to hygroscopic salts within ash deposits14. These salts exhibit a strong tendency to absorb moisture from the surrounding environment, which can, under suitable conditions, result in the formation of aqueous solutions. This phenomenon, known as deliquescence, promotes the accumulation of corrosive environments on boiler surfaces, thereby accelerating material degradation. Another contributing factor is the condensation of sulfuric acid (H2SO4(g)) when temperatures drop below its dew point. However, acid dew point corrosion, traditionally the dominant corrosion mechanism in coal-fired boilers, plays a comparatively less significant role in biomass combustion11,14,23,24. Additionally, when temperatures fall below the water dew point, acidic gases such as HCl(g) and SO2(g) are absorbed by condensed water, forming an electrolyte that aggressively corrodes carbon steel surfaces35,36,37. Collectively, these factors constitute the mechanisms driving low-temperature corrosion in biomass boilers. A more detailed discussion of these mechanisms and the formation of corrosive species will be provided later in this article. Many interacting factors influence the formation of corrosive species and the severity of corrosion, such as combustion technology24, boiler operating mode (e.g., start-up, on-load, low-load, high-load, and shutdown)10,38,39,40,41, material selection and temperatures10,14,39,40,41, additives in combustion11,25, as well as flue gas and fly ash compositions25,42.

Biomass-derived fuels often have a high moisture content and a variety of ash-forming elements that will affect their utilization. Figure 1 illustrates how the ash-forming elements differ across various biomass fuels. These compositional differences strongly influence what factors dominate deposit chemistry, how deposits form, and what corrosive species emerge in the cold end. For instance, chlorine-rich fuels such as straw and reed tend to create more corrosive deposits, while woody biomasses such as stemwood from birch and spruce generally contain lower content of ash-forming elements and exhibit a less problematic composition from a corrosion standpoint.

Biomass boilers employ several designs, including grate-fired units, bubbling fluidized bed (BFB) and circulating fluidized bed (CFB) combustors (often used for co-firing with coal), pulverized fuel systems (also frequently co-fired with coal), and Kraft recovery boilers to accommodate various fuel types. Each of these designs has a distinct temperature profile from the combustion zone to the flue gas exit. Flame temperatures in grate-fired units and pulverized fuel systems normally reach around 1000 to 1200 °C43,44, while fluidized bed combustors typically operate at lower temperatures to minimize thermal NOx formation and to maintain bed stability. After leaving the combustion chamber, the hot flue gases first pass through the superheaters, which are typically limited to maximum metal temperatures of around 450–500 °C due to the risk of chloride-induced high-temperature corrosion24,45. Downstream, at the inlet of the economizers, the flue gas temperature is usually around 450 °C46. In economizers, low-temperature corrosion often occurs in the coldest sections, where the feedwater enters. Further downstream, the flue gas temperature at the air preheaters is typically about 200 °C46. If no flue gas condensation or latent heat recovery is employed, the final flue gas temperature at the stack is typically around 130–150 °C23.

The main objective of this review is to provide a comprehensive overview of the existing literature on low-temperature corrosion in biomass boilers to clarify the work that has been accomplished so far and to elucidate the current state of knowledge in this field. The structure of this paper is organized as follows: Section “Primary drivers of low-temperature corrosion in biomass boilers” provides a detailed explanation of the primary factors contributing to low-temperature corrosion in biomass boilers, followed by Section “Summary of previously published works”, which presents a detailed table summarizing the key findings from previous studies. Section “Analysis,discussion, and critical review of the literature review” offers a broader analysis of the literature, examining the topic from various perspectives, including corrosion-prone areas, mitigation strategies, and underlying corrosion mechanisms. The review concludes in Section “Summary and conclusion” with a summary of key insights and recommendations for future research.

Primary drivers of low-temperature corrosion in biomass boilers

In the past, low-temperature corrosion was a problem typically occurring through the utilization of coal with high sulfur content (up to 6 wt%, d.b.), leading to the formation of H2SO4(g), which upon condensation would result in severe corrosion below the H2SO4 dew point. This type of corrosion is commonly referred to as dew point corrosion47,48. However, the situation in biomass boilers has become more complex. Over the past three decades, deposits containing hygroscopic salts have been shown to contribute significantly to corrosion in these boilers9,14,18,20,21,22,23,28,29,30,31,42,49. For these salts, corrosion can occur over a broader temperature range, influenced by the deposit composition and water vapor concentration in the flue gas. Due to these various contributing factors, there is no universally agreed-upon temperature definition of low-temperature corrosion. This paper defines low-temperature corrosion as corrosion occurring when material temperatures fall below approximately 150 °C. This definition allows for a broader range of mechanisms to be considered. Figure 2 provides an overview of the various mechanisms that contribute to a corrosive environment at the cold end of biomass boilers.

Sulfuric acid dew point corrosion

The acid dew point refers to the temperature at which flue gas becomes saturated with a specific acid. When the temperature drops below this point, the gas can no longer maintain the acid in its gaseous form and will start condensing. In power boiler technology, the term acid dew point typically refers to H2SO4 because it has a significantly higher dew point than other acidic components. H2SO4(g) originates from the sulfur in fuel or additives. During the combustion of sulfur-containing fuels, SO2(g) is produced, and a small fraction of this SO2(g) is further oxidized to form SO3(g). In biomass combustion, the concentration of SO3(g) in the flue gas is typically very low, often in the sub-ppmv range (frequently undetectable)20,23,30. The formation of SO3(g) in the combustion zone (in-flame) has been investigated in numerous studies50,51,52,53,54,55 and is known to take place through two mechanisms, namely homogeneous gas-phase reactions, which occur by the reaction of SO2 with oxygen radicals (Reaction 1)56 or with OH radicals via HOSO2 as an intermediate (Reactions 2.1 and 2.2)52; and heterogeneous catalytic reactions (e.g., Reaction 3)57.

Low-temperature corrosion caused by H2SO4(aq) has been a well-recognized issue in coal-fired boilers for decades. In fact, reports of dew point corrosion in coal-fired boilers date back to the 1950s48,58,59. In biomass boilers, however, acid dew point is not normally a major limiting factor of cold-end material temperatures. This is mainly because biomass fuels typically have a low sulfur content24, leading to low SO2(g) formation. In addition, the relatively low combustion temperatures in biomass boilers result in lower SO2(g) to SO3(g) conversion51,52. Air staging also lowers the formation of SO3(g)60. Moreover, the SO3(g) is readily captured by the alkalis present in biomass through the formation of alkali sulfates61,62,63. From a mechanistic perspective, the sulfation of gaseous alkali chlorides, for instance, KCl(g), occurs with SO3(g) (Reaction 4) rather than with SO2(g) (and oxygen)61,62. Therefore, sulfation of alkali chlorides is a desired reaction as alkali chlorides cause high-temperature corrosion of superheater tubes. Thus, the sulfation of KCl(g) is more efficient with additives forming SO3(g) rather than SO2(g)63,64,65.

This is a favorable reaction since K2SO4 is less corrosive for superheaters than KCl. Finally, condensed H2SO4(aq) droplets can potentially be neutralized by fly ash and alkaline deposits formed during biomass combustion, thereby preventing them from causing corrosion and further damage30.

While H2SO4 dew point corrosion is not expected in most biomass boilers due to the factors discussed above, it can still become relevant under certain conditions, such as when firing low-alkali and high-sulfur fuels in boilers equipped with specific flue gas cleaning equipment. In Selective Catalytic Reduction (SCR) systems, for instance, up to 2% of the SO2(g) can typically be catalytically converted to SO3(g)66, resulting in higher SO3(g) concentrations and making cold-end components more vulnerable to acid condensation and corrosion. Therefore, H2SO4 dew point corrosion should not be entirely dismissed in biomass boilers.

Corrosion below the water dew point

In biomass boilers, water dew point corrosion occurs when the temperature of metal surfaces falls below the dew point of water vapor in the flue gas. This dew point typically ranges between 50 and 65 °C, depending on the water vapor concentration in the flue gas. A key factor influencing water dew point corrosion is the overall composition of the flue gas. In biomass combustion, flue gases typically contain 15–35 vol% of water vapor due to the high inherent moisture content of many biomass fuels. When water vapor condenses on a cooler surface, the resulting liquid layer can readily absorb acidic gases such as HCl(g) and SO2(g), forming HCl(aq) and H2SO3(aq), both of which can lead to severe corrosion of carbon steel35,36,37. From an operational perspective, water dew point corrosion is most frequently encountered during partial load, as well as start-up and shutdown periods, when material temperatures drop below the water dew point.

Hygroscopic salt corrosion

Many salts that form during combustion, particularly chlorides, are highly hygroscopic, meaning they can readily absorb/adsorb moisture from their surroundings. Some hygroscopic salts, such as CaCl2 (in this review, salts are referred to by their anhydrous formulas, but this includes all hydrates likely to occur under boiler cold-end conditions, e.g., CaCl2·xH2O, unless a certain hydrate is explicitly specified) are deliquescent, which means they can absorb enough water to form an aqueous solution at a certain relative humidity. The deliquescence of hygroscopic salts can create a corrosive environment in the cold end of biomass boilers, leading to the degradation and damage of tube surfaces.

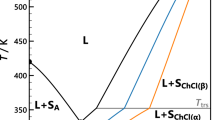

The relative humidity at which a deliquescent salt begins to absorb moisture from the flue gas is called deliquescence relative humidity (DRH), and for any given salt, it varies with temperature18. For flue gases, it is more common to talk about water vapor concentration in volume percentage rather than relative humidity. For this reason, the term deliquescence temperature at a certain vol% of water vapor is mainly used to describe hygroscopic properties. Figure 3 illustrates the deliquescence temperatures of various saturated aqueous salt solutions at different water vapor concentrations. In this figure, each curve represents the deliquescence behavior of a specific salt. Above the curves, the salts remain solid, while below the curves, they deliquesce and form a saturated aqueous solution. Understanding these curves is crucial for predicting when and how hygroscopic corrosion may occur in boiler systems.

It should be noted that even when the relative humidity is below the DRH, i.e., above the deliquescence curve, the environment may still not be entirely safe from corrosion. For instance, NH4Cl(s) can cause corrosion without fully dissolving into an aqueous solution25,67. Figure 4 highlights the region above the deliquescence curve where NH4Cl(s) can absorb moisture, leading to metal surface corrosion. This behavior can be explained, for instance, by the adsorption of water onto the salt surface. Additionally, capillary condensation can occur below the saturation pressure of the bulk gas within, e.g., porous ash particles or corrosion products68, which might also contribute to corrosion below the DRH.

The yellow shaded area illustrates the region above the deliquescence curve of NH4Cl (at relative humidity below the DRH), where the salt absorbs moisture without fully dissolving, resulting in corrosion of carbon steel. The data points and the empirical formula are adapted and modified from25.

Besides DRH, another important factor governing the moisture interactions of salts is the efflorescence relative humidity (ERH). Whereas deliquescence describes the point at which a salt begins to dissolve upon increasing relative humidity, efflorescence refers to the point at which a saturated salt solution (or partially dissolved salt) re-crystallizes upon decreasing relative humidity. Efflorescence often exhibits hysteresis effects. A salt may remain in a supersaturated solution state below the DRH until it finds favorable conditions to re-crystallize, resulting in an ERH that can be significantly lower than the DRH. Understanding both DRH and ERH is crucial for predicting the behavior of salts under varying humidity conditions. Table 1 lists the DRH and ERH values at room temperature for several compounds that may form during combustion processes. Notably, most published DRH/ERH data originate from atmospheric chemistry research conducted under near-ambient laboratory conditions69, and systematic determinations under the atmosphere of boiler flue gases remain scarce. Nonetheless, some flue gas–relevant data points have recently been reported11,15,25,70.

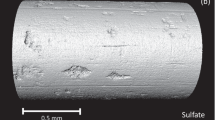

Several factors influence the severity of corrosion caused by hygroscopic deposits. One key factor is the thickness of the deposit layer on the surface42, as thicker layers can act as a barrier, preventing flue gas humidity from reaching the steel surface and thereby reducing corrosion rates. Additionally, these thicker deposits can increase surface temperatures, which reduces the salts’ ability to absorb moisture. Consequently, flue gas moisture reacts most severely with thin layers of hygroscopic salts, where the protective barrier effect is minimal.

The size of salt particles also plays a role in hygroscopic behavior. Smaller particles have a larger specific surface area, enabling them to react more effectively with flue gas humidity and contribute to corrosion42. Additionally, the chemical composition of deposits can also influence corrosion behavior. If the deposit contains only minor amounts of hygroscopic salts, the bulk of the deposit may hinder or limit the formation of a continuous liquid film, thereby reducing the corrosive effect71.

A salt mixture can deliquesce at a relative humidity level lower than the DRH of any single salt component. In other words, the mixture exhibits higher hygroscopicity compared to its pure constituents. Figure 5a provides a visualization of how the deliquescent behavior of a salt mixture varies with its composition and relative humidity. The figure shows a schematic phase diagram for a system comprising salt A, salt B, and water vapor. As can be seen, for all ratios of salts, the mixture deliquesces at a relative humidity level lower than the DRH of any individual salt component. At a specific ratio of salts, the mixture reaches the lowest relative humidity at which it can deliquesce, defined as the eutonic relative humidity (eutonic RH), also known as mutual deliquescence relative humidity (MDRH). This particular ratio is referred to as the eutonic concentration, also known as eutonic composition. Any mixture of two salts, even if the proportions are well away from the eutonic point, can still take up some water vapor at eutonic RH. It will continue to do this until one of the salts is entirely used up to create this eutonic point. If there is an excess of the other salt, it remains out of the solution in the solid phase. Hence, to the left, we have a mixture of A(s) with A(aq)+B(aq), and once it reaches the eutonic RH, only part of it is liquid, and some of the salt A will remain in its solid phase. To the right, similarly, some of the salt B remains in its solid phase above the eutonic RH. If humidity is raised further, more and more of the mixture becomes liquid until, eventually, the entire mixture is in its liquid phase. An example of this phenomenon is shown in Fig. 5b, which illustrates data for the NaCl–KCl system. Pure NaCl(s) and KCl(s) exhibit DRH values in the range of 73–77% and 83–86%, respectively. However, when mixed in their eutonic composition (XKCl = 0.3), the resulting mixture displays a eutonic RH of 72.3( ± 0.5)%, which is lower than the DRH values of either pure salt72. It is worth noting that, in a mixture of salts, if one component is significantly more hygroscopic than the others, the deliquescence behavior of the entire mixture is practically governed by that single salt11,73. In such cases, the eutonic lowering is minimal and can be neglected for engineering purposes. This means that, for practical corrosion assessments, it is sufficient to base the minimum safe surface temperature on the DRH of the most hygroscopic salt present. However, the behavior of salt mixtures under actual boiler conditions has not yet been thoroughly studied, and this remains an area requiring further investigation.

a A schematic phase diagram illustrating key regions and critical points in a theoretical salt A + salt B + H2O vapor system. For all ratios of salts, the mixture deliquesces at a relative humidity lower than the DRH of any individual salt component. b An experimentally derived phase diagram for the NaCl-KCl system showing mutual deliquescence behavior across various mixing ratios. At the eutonic composition (XKCl = 0.3), the mixture deliquesces at around 72.3% RH, which is lower than the DRH of either pure salt. The dashed lines are imaginary boundaries to illustrate the phase separations (Adapted and modified with permission from reference72).

In boilers, the corrosion products themselves can also be hygroscopic. When corrosion occurs, iron chlorides may form as corrosion products. These iron chlorides are highly hygroscopic and can absorb moisture from the environment, further accelerating corrosion. This process creates a self-perpetuating cycle of material degradation, as hygroscopic corrosion products continuously promote additional corrosion71. The corrosion mechanism, which is driven by the corrosion products themselves, is sometimes referred to as an autocatalytic or feedback mechanism71.

Summary of previously published works

Initial observations regarding low-temperature corrosion in biomass boilers were reported in the late 1990s35. Early research primarily focused on seeking practical solutions to prevent corrosion17,31. A more significant expansion in research on this topic emerged around 2012, with a notable increase in publications. Alkali and iron chlorides were the earliest salts recognized as contributors17,31, and over time, additional chlorides, such as CaCl2, ZnCl2, and NH4Cl, were also found to play significant roles. More recent research has shifted towards quantifying the hygroscopic properties and deliquescence points, exploring the interplay between operational parameters and corrosion phenomena, and developing advanced corrosion-mitigating strategies and monitoring techniques. Table 2 provides a chronological summary of the literature on low-temperature corrosion in biomass boilers. To maintain impartiality and preserve the integrity of the original works, we only report the observations, findings, or conclusions of prior research without necessarily endorsing or disputing the authors’ viewpoints. Critical evaluations of selected findings will be presented in the subsequent section (Section “Analysis, discussion, and critical review of the literature review”), where we discuss conclusions that may require alternative interpretations.

Analysis, discussion, and critical review of the literature review

Corrosion-prone areas in boilers

Drawing from the literature summarized in Table 2, we have identified key areas within the cold end of biomass boilers that are susceptible to corrosion. Despite differences in fuel type, boiler design, and operating conditions, certain areas have consistently been reported to experience low-temperature corrosion. Figure 6 provides a broad overview of the areas of a biomass boiler that are most vulnerable to low-temperature corrosion, along with examples of associated corrosive species and the corresponding minimum safe material temperatures for carbon steel surfaces. Air preheaters are a typical location where corrosion has been reported to occur9,11,12,13,14,17,18,19,22,23,30. Economizers have also been reported to experience corrosion in various biomass boilers21,42. Components within the flue gas cleaning system, including flue gas ducts and baghouse filters13,20,23,28, and areas downstream of baghouse filters12,22, such as gas/gas heat exchangers10,40,41 have also been another area prone to low-temperature corrosion.

Corrosion-prone areas are shown in red, along with the reported species responsible for corrosion in these regions. Minimum safe material temperatures to avoid CaCl2 deliquescence and NH4Cl water absorption under different flue gas water vapor concentrations are also presented in the figure. Note that this is a generalized schematic intended to illustrate potential corrosion areas based on findings from the literature review; boiler designs can vary significantly, and additional species may also contribute to corrosion. (ECOs: Economizers, APH: Air Preheater, ESP: Electrostatic Precipitator, BHF: Baghouse Filter, SCR: Selective Catalytic Reduction, HE: Heat Exchanger).

Corrosion preventive suggestions

As indicated in Table 2, the primary approach for preventing low-temperature corrosion in biomass boilers is maintaining material and surface temperatures above critical thresholds to prevent the deliquescence of hygroscopic salts and also condensation of H2SO4(g) and water11,12,14,17,18,20,23,28,29,30,31,74. These thresholds depend on the specific corrosive species and flue gas composition. Fuel composition also plays an essential role; by reducing chlorine and alkali metal content through pretreatment19 or selecting low-chlorine fuels like woody biomass over straw10,12,39,40,41, the corrosion risk can be lowered. Additionally, adjusting flue gas composition, such as lowering water vapor concentration (e.g., by drying the fuel)18,30,74 and controlling NH3(g) slip25,42, minimizes the formation of hygroscopic compounds. Using corrosion-resistant materials like enamel-coated pipes19,31, Teflon-coated tubes75, appropriate stainless steels and high-grade alloys10,14,15,39,40,41,76, or specific protective coatings such as Ni-Al and NiCrMoSiB19 is another approach that enhances the durability of heat exchanger tubes and other corrosion-prone components. Implementing regular ash removal and cleaning procedures, especially for economizers and air preheaters downstream of dust precipitators, is another approach that helps prevent the accumulation of corrosive deposits21. Optimized boiler design and operational practices, such as strategically locating economizers21, can also reduce condensation risks on cold surfaces, and in some systems, bypassing FGD units helps maintain temperatures that lower corrosion risk10,39,40,41. Additionally, real-time monitoring of corrosive deposit formation through online probes enables operators to make timely adjustments and limit corrosion progression9,10,15,30,39,40,41,42.

Practical advantages, limitations, and trade-offs of mitigation strategies

Many of the preventive methods mentioned above are based on case-specific studies and are tuned to particular combinations of boiler designs, fuel types, and operational conditions. While these strategies may not be universally applicable to all biomass boilers, they offer a valuable overview of the solutions explored within the field. By understanding the diversity of approaches that have been successfully implemented, engineers and operators can better identify methods suited to their own systems. Table 3 provides a critical assessment of the most commonly implemented strategies, summarizing their primary benefits and known limitations.

Practical case studies: applicable examples for plant operators

Calcium-rich fuels and limestone addition → formation of CaCl2-containing deposits

Combustion of chlorine- and calcium-rich biomasses (such as in a case study where the fuel contained 12.5 wt% Ca and 0.13 wt% Cl9), and also the addition of limestone (CaCO3(s)) for SO2(g) capture, can lead to the formation of Ca-containing deposits such as CaO(s) or Ca(OH)2(s) on heat-exchanger surfaces, which can then chlorinate upon reaction with HCl(g) in the cold-end of the boilers77,78. The detection of CaCl2 on boiler heat-exchanger surfaces11,14,23 indicates that this transformation is kinetically fast enough to take place before the Ca-containing deposits are removed, e.g., by soot-blowing. Even small amounts of CaCl2 in these deposits can present a serious corrosion risk due to moisture absorption and subsequent deliquescence14. To mitigate this risk, the surface metal temperature should be kept above the CaCl2 deliquescence point (see Fig. 6).

Ammonia slip + HCl(g) → formation of NH4Cl-containing deposits

In boilers equipped with SCR/SNCR, ammonia (NH3(g)) and HCl(g) react to form hygroscopic deposits containing NH4Cl(s,aq), for instance, downstream of SCR units. NH3(g) typically originates during SCR/SNCR processes, where injected NH3(g) intended for NOx reduction escapes into the flue gas (known as ammonia slip) due to incomplete mixing or suboptimal operating conditions. In some cases, NH3(g) may also come from fuel-bound nitrogen, particularly during low-load boiler operation42. According to25, if the HCl(g) concentration is below 5 ppmv and the NH3(g) concentration is below 1 ppmv (conditions that can reasonably occur downstream of an SCR unit), NH4Cl(s) can form at temperatures below approximately 85 °C. At higher NH3(g) concentrations, NH4Cl(s) can form even at higher temperatures. Once formed, NH4Cl(s) can absorb moisture and cause rapid corrosion of carbon steel at material temperatures below 80–100 °C, depending on the water vapor concentration in the flue gas. The measurements show that the corrosion rate is higher at lower material temperatures25. The minimum safe carbon steel temperatures required to prevent NH4Cl-induced corrosion under various flue gas water vapor concentrations are presented in Fig. 6.

The mechanisms through which corrosive species form, leading to low-temperature corrosion in biomass boilers

Extensive observations from the literature show that low-temperature corrosion issues in the cold end of biomass boilers are consistently linked to the formation of hygroscopic salt deposits. Many of the deposit formation mechanisms are similar to those observed at higher temperatures, as discussed in previous studies, e.g., in79,80,81. However, once deposits are formed, the mechanisms by which they induce corrosion can differ significantly in the cold end. Specifically, processes such as salt deliquescence and acid condensation become far more important in the cold end. Here, we synthesize the findings from multiple investigations and group them under five principal mechanisms (as illustrated in Fig. 7).

A recurring theme across several works that we reviewed is that flue gas ash particles directly deposit onto the surfaces of the boiler or heat exchanger (mechanisms 1)12,13,19,21,22,25,30,74. Both fine and coarse ash particles form in power boilers, with fly ash composition primarily determined by factors such as fuel type, additives, combustion technology, and flue gas composition. Fly ash particles then deposit on cold-end surfaces. Depending on the deposit composition and the water vapor concentration in the flue gas, these deposits can absorb moisture and become corrosive. This water uptake also increases the deposition rate, making it more difficult to remove. Fly ash can also absorb water while in flight, becoming sticky and leading to corrosion once it deposits9,23. The reaction of gases with deposits on the heat exchanger surface is another crucial mechanism that can result in the formation of corrosive compounds (mechanism 2). For instance, highly hygroscopic CaCl2(s) can form in deposits through reactions between CaO(s) or Ca(OH)2(s) and HCl(g), leading to the formation of CaOHCl(s) and CaCl2(s)11,14,23. If these chlorides absorb water, they can create a corrosive solution. The next mechanism is the formation of iron chlorides as corrosion products beneath the deposit (mechanism 3)17,31. Iron chlorides are highly hygroscopic and can be a driving force of the corrosion process. Another mechanism (mechanism 4) involves the direct condensation of H2SO4(g) onto heat exchanger surfaces with temperatures below the H2SO4 dew point20,28,29, although the overall contribution of H2SO4 to corrosion is not typically considered significant in biomass combustion. The final mechanism (mechanism 5) involves the absorption/adsorption of gases such as SO2(g) and HCl(g) onto wet surfaces (or deliquescent salts)82,83,84. This mechanism differs from the condensation-driven mechanisms, as it relies on the absorption of gases into the liquid phase that already exists in the deposit. When moisture is present, either from deliquescent salts or water formed through condensation, gases are absorbed into this liquid layer, leading to further chemical reactions such as carbonation, sulfation, or chlorination. This process adds another dimension to deposit formation, as the presence of water allows for the capture and incorporation of acidic or corrosive gases into the deposit, enhancing both deposition rates and the corrosive nature of the deposit. These mechanisms are likely applicable to various combustion technologies, such as oxy-combustion and chemical looping combustion systems. These systems share similar flue gas compositions and temperature gradients that encourage deposition, particularly in the cooler sections.

Re-evaluating the mechanism through which HCl contributes to corrosion: Condensation or absorption by water?

Although it has been widely assumed in the reviewed literature that HCl(g) may condense similarly to H2SO4(g) (HCl dew point corrosion)10,19,22,39,40,41, we could not find solid evidence to support this assumption. Some studies (e.g.85) have proposed empirical correlations to predict an HCl dew point, typically placing it near (slightly above/below) the water dew point (see Fig. 8). However, these formulas likely estimate the onset of water condensation (water dew point), during which HCl(g) is efficiently absorbed into the liquid phase as HCl(aq), rather than indicating a distinct condensation point for HCl(g) itself. This absorption may have been interpreted as HCl(g) condensation, leading to the widespread assumption of an HCl dew point under boiler conditions. Since such estimations lack conclusive experimental or theoretical support, the notion of an HCl dew point should be approached with caution, especially since the thermodynamics of pure HCl(g) also strongly argue against condensation under boiler conditions. The saturation vapor pressure of anhydrous HCl(g) is around 40 bar at 17.8 °C86. Given that typical partial pressures of HCl(g) in biomass-boiler flue gas are far below atmospheric pressure, equilibrium condensation would require temperatures significantly below any encountered in real boilers or stacks, even during shutdown. Therefore, we believe that the concept of an HCl dew point is unlikely to exist in a boiler environment. This perspective helps clarify design and operating decisions in the cold end of boilers, where preventing water condensation (or effectively managing it) largely determines whether HCl-driven corrosion can occur.

It can be concluded that HCl contributes to low-temperature corrosion in biomass boilers through three primary mechanisms. The first involves the reaction of HCl(g), e.g., with solid calcium oxides or hydroxides, leading to the formation of highly hygroscopic salts such as CaCl2. Another mechanism results from the reaction of HCl(g) with NH3(g), producing hygroscopic NH4Cl(s), which absorbs moisture and leads to metal surface corrosion. A further mechanism occurs when HCl(g) is absorbed into water below the water dew point, forming corrosive HCl(aq). Nevertheless, the possibility of other HCl-induced corrosion mechanisms, such as the HCl(aq) formation above the water dew point through adsorption by extremely thin water layers, should not be overlooked. Future studies should investigate such potential mechanisms.

Summary and conclusion

Three decades of field observations and laboratory evidence indicate that low-temperature corrosion in large-scale biomass boilers correlates with chlorine chemistry rather than with sulfur chemistry, often accompanied by the presence of hygroscopic salts. While sulfuric acid dew point corrosion remains relevant under specific conditions, e.g., in boilers equipped with Selective Catalytic Reduction (SCR) systems, it is rarely the primary limiting factor in biomass combustion due to the generally low sulfur content of biomass fuels and the efficient capture of SO3(g) by alkaline ash. Instead, the dominant corrosion mechanisms at the cold end are linked to the formation and deliquescence of hygroscopic salts such as CaCl2 and NH4Cl. These salts absorb flue-gas moisture and create highly aggressive electrolytes that degrade heat exchange surfaces, especially carbon steel.

The formation of deposits containing hygroscopic salts occurs through various mechanisms such as direct deposition of particles, reactions between flue gas constituents like HCl(g) and existing deposits, and the formation of hygroscopic corrosion products. The type of biomass fuel and the use of additives significantly influence the deposit composition and corrosivity. For instance, fuels with high chlorine content, such as straw, tend to form more hygroscopic salts, while additives can significantly alter the chemistry of deposits, either mitigating or exacerbating corrosion. Corrosion rates are highly dependent on material temperatures, and maintaining temperatures above the deliquescence points of hygroscopic salts is crucial to prevent moisture absorption and subsequent corrosion. Corrosion is also influenced by the relative humidity and the presence of acidic gases like H2SO4(g) and HCl(g) in the flue gas. However, we argue that HCl(g) does not condense as H2SO4(g) does, but instead is absorbed by pre-existing liquid water. The formation of iron chlorides and other hygroscopic corrosion products beneath deposits can accelerate material degradation as these products continue to absorb moisture, perpetuating the corrosion cycle.

The most commonly affected components include air preheaters, economizers, and various elements of the flue gas cleaning system, such as ducts, baghouse filters, and gas-gas heat exchangers. These areas are particularly susceptible due to their relatively low surface temperatures and the accumulation of chlorine-rich or hygroscopic deposits, which, in the presence of water vapor, form corrosive liquid films.

Corrosion mitigation demands a combination of strategies such as maintaining surface temperatures above critical temperatures (for instance, above 90 °C at 20 vol% water vapor to prevent water uptake by NH4Cl or above 105 °C at 20 vol% water vapor to prevent deliquescence of CaCl2), optimizing fuel composition to reduce chlorine content, controlling additive dosing (notably limestone and ammonia, which foster the formation of CaCl2 and NH4Cl) and applying corrosion-resistant alloys or dense enamel and Ni-based coatings particularly where temperature control is impractical. Optimized boiler design (e.g., strategic placement of economizers), regular cleaning, and advanced monitoring techniques, such as online deposit probes, can also help manage deposit build-up and assess corrosion risks in real time.

Although this review compiles findings from various industrial biomass boiler types, the extent to which individual results can be generalized across different boiler configurations has not been thoroughly investigated in the literature. Most studies have been conducted on single installations with specific fuel blends, operating conditions, and flue gas cleaning systems. Comparable diagnostic approaches have seldom been applied systematically across multiple boiler types, and comprehensive cross-validation is therefore limited. Nevertheless, since similar (chlorine-driven) chemistry governs deposit formation in most biomass boilers, it is reasonable to expect that many of the findings are generalizable to a significant extent. For example, the presence of HCl(g) in the flue gas, together with Ca-bearing ash or NH3 slip, poses a risk for the formation of hygroscopic CaCl2 or NH4Cl, largely irrespective of boiler type. Therefore, while specific mitigation strategies should be adapted to the conditions of individual installations, the core corrosion risks and mechanistic principles outlined in this review are expected to be broadly applicable to a wide range of biomass boiler configurations.

Looking ahead, further progress in understanding and mitigating low-temperature corrosion requires integrating detailed salt–gas–surface models into boiler CFD, taking into account temperature gradients within the deposit layers. Robust in-situ sensors that track deposit properties under operating conditions would also be valuable for process optimization. In addition, data on the hygroscopic properties of individual salts and salt mixtures under flue gas conditions remain limited, particularly regarding their behavior in the presence of temperature gradients and their impact on corrosion. Addressing these gaps is essential for improving understanding and control of corrosion in real boiler systems and guiding targeted mitigation strategies.

Data availability

No datasets were generated or analysed during the current study.

References

Chen, Q. et al. Condensing boiler applications in the process industry. Appl. Energy 89, 30–36 (2012).

IEA Bioenergy. Combustion of wood chips and composting residues for process steam generation in a potato processing industry, industrial process heat: case study 1. Contribution of Task 32 to the intertask project on industrial heat, 1–16 (2020).

Elwardany, M. Enhancing steam boiler efficiency through comprehensive energy and exergy analysis: A review. Process Saf. Environ. Prot. 184, 1222–1250 (2024).

Electric Power Research Institute (EPRI). Assessment of air preheater effects on power plant efficiency. Report 1018472 (2008).

Iliev, I., Terziev, A. & Beloev, H. Condensing economizers for large-scale steam boilers. Proc. 9th Int. Conf. Therm. Equip., Renew. Energy Rural Dev. (TE-RE-RD) 180, 1–12 (2020).

Wang, C. et al. Application of a low-pressure economizer for waste heat recovery from the exhaust flue gas in a 600 MW power plant. Energy 48, 196–202 (2012).

Wang, C., He, B., Yan, L., Pei, X. & Chen, S. Thermodynamic analysis of a low-pressure economizer based waste heat recovery system for a coal-fired power plant. Energy 65, 80–90 (2014).

Jafarihonar, F., Vainio, E., Hupa, L. & Hupa, M. Deposit sintering in modern Kraft recovery boilers − The role of NaOH? Fuel 371, 132–138 (2024).

Vainio, E., Ruozzi, A., Kinnunen, H., Lauren, T. & Hupa, L. Low-temperature corrosion in a BFB boiler firing biomass and waste streams – Online measurement technique for monitoring deposit corrosivity. Fuel 371, 131864 (2024).

Montgomery, M., Olesen, R. E. & Gensmann, P. Corrosion in the flue gas cleaning system of a biomass-fired power plant. J. Fail. Anal. Prev. 17, 195–204 (2017).

Vainio, E. et al. Hygroscopic properties of calcium chloride and its role on cold-end corrosion in biomass combustion. Energy Fuels 33, 11913–11922 (2019).

Pan, P. et al. Investigation on the hygroscopicity of deposits at the cold-end of biomass and coal-fired plants. Energy Fuels 35, 8006–8022 (2021).

Ma, L., Wei, W., Sun, F. & Shi, Y. Research on formation mechanism of typical low-temperature fouling layers in biomass-fired boilers. Case Stud. Therm. Eng. 35, 102076 (2022).

Ruozzi, A., Vainio, E., Kinnunen, H. & Hupa, L. Cold-end corrosion in biomass combustion – Role of calcium chloride in the deposit. Fuel 349, 128344 (2023).

Yahi, S. et al. A novel methodology for monitoring low-temperature corrosion caused by hygroscopic salts using linear polarization resistance. Electrochim. Acta 478, 143827 (2024).

Tran, H. N., Barham, D. & Reeve, D. W. Sintering of fireside deposits and its impact on plugging in Kraft recovery boilers. Tappi J. 71, 109–113 (1988).

Frandsen, F. et al. Deposit formation and corrosion in the air preheater of a straw-fired combined heat and power production boiler. IFRF Combust. J. 1, 23 (2002).

Lindau, L. & Goldschmidt, B. Low-temperature corrosion in bark fuelled, small boilers. Vaermeforsk (2002).

Song, J., Gu, Y., Li, J. & Fang, J. Study on air preheater corrosion problem of CFB biomass directed-fired boiler in Zhanjiang biomass power plant. Proc. Appl. Mech. Mater. 291, 294–299 (2013).

Vainio, E., Lauren, T., Demartini, N., Brink, A. & Hupa, M. Understanding low-temperature corrosion in recovery boilers: Risk of sulphuric acid dew point corrosion? J. Sci. Technol. Prod. Process. 4, 14–22 (2014).

Retschitzegger, S., Brunner, T. & Obernberger, I. Low-temperature corrosion in biomass boilers fired with chemically untreated wood chips and bark. Energy Fuels 29, 3913–3921 (2015).

Wang, Y. et al. Experimental study on dew point corrosion characteristics of the heating surface in a 65 t/h biomass-fired circulating fluidized bed boiler. Appl. Therm. Eng. 96, 76–82 (2016).

Vainio, E. et al. Low-temperature corrosion in co-combustion of biomass and solid recovered fuels. Fuel 184, 957–965 (2016).

Hupa, M., Karlström, O. & Vainio, E. Biomass combustion technology development - It is all about chemical details. Proc. Combust. Inst. 36, 113–134 (2017).

Vainio, E., Yrjas, P., Hupa, L. & Hupa, M. Cold-end corrosion caused by hygroscopic ammonium chloride in thermal conversion of biomass and waste. Fuel 346, 128061 (2023).

Air Quality Expert Group (AQEG). The potential air quality impacts from biomass combustion. 1–80 (2017).

Magasiner, N. Back-end corrosion in bagasse-coal fired boilers with particular reference to co-generation. South Afr. Sugar Technologists’ Assoc. 83, 422–443 (2010).

De Martini, N., Vainio, E., Holmblad, H. & Hupa, M. Understanding low-temperature corrosion in Kraft recovery boilers - Implications for increased energy recovery. In Pulping, Engineering, Environmental, Recycling, Sustainability Conference, 127–135 (2016).

De Martini, N., Vainio, E., Lauren, T. & Hupa, L. Bisulfate formation and impact on low-temperature corrosion in Kraft recovery boilers. In the International Chemical Recovery Conference (ICRC) (2017).

Brunner, T. et al. Low-temperature corrosion in biomass-fired combustion plants – Online measurement of corrosion rates, acid dew points, and deliquescence corrosion. In Proceedings of 25th European Biomass Conference and Exhibition 393–400 (2017).

Jensen, J. P., Fenger, L. D. & Henriksen, N. Cold-end corrosion in biomass and waste incineration plants. Power Plant Chem. 3, 469–471 (2001).

Ganapathy, V. Cold-end corrosion: Causes and cures. Hydrocarb. Process. 68, 57–59 (1989).

Chen, H., Pan, P., Chen, X., Wang, Y. & Zhao, Q. Fouling of the flue gas cooler in a large-scale coal-fired power plant. Appl. Therm. Eng. 117, 698–707 (2017).

Pan, P., Chen, H., Liang, Z. & Zhao, Q. Deposition and corrosion characteristics of liquid-solid droplets on tubular corrosion probes in desulfurized flue gas. Eng. Fail. Anal. 90, 129–140 (2018).

Frandsen, F. J. Utilizing biomass and waste for power production - A decade of contributing to the understanding, interpretation, and analysis of deposits and corrosion products. Fuel 84, 1277–1294 (2005).

Chen, H., Pan, P., Wang, Y. & Zhao, Q. Field study on the corrosion and ash deposition of low-temperature heating surface in a large-scale coal-fired power plant. Fuel 208, 149–159 (2017).

Pan, P., Chen, H., Liang, Z. & Zhao, Q. Desulfurized flue gas corrosion coupled with deposits in a heating boiler. Corros. Sci. 131, 126–136 (2018).

Jones, F., Ryde, D. & Hjörnhede, A. Down-time corrosion in boilers. Fuel Process. Technol. 141, 276–284 (2016).

Montgomery, M., Nielsen, L. V. & Petersen, M. B. Assessment of corrosion in the flue gas cleaning system using online monitoring. VGB PowerTech 10, 77–83 (2015).

Montgomery, M. & Gensmann, P. Online corrosion measurements undertaken in the flue gas cleaning unit of a biomass-fired power plant. In Eurocorr, in combination with the 20th International Corrosion Congress and the Process Safety Congress (2017).

Montgomery, M., Nielsen, L. V. & Petersen, M. B. Utilization of online corrosion monitoring in the flue gas cleaning system. In Proceedings of NACE CORROSION Conference (2015).

Herzog, T. et al. Corrosion caused by dew point and deliquescent salts in the boiler and flue gas cleaning. Waste Manag. 3, 343–358 (2012).

Yin, C., Rosendahl, L. A. & Kær, S. K. Grate-firing of biomass for heat and power production. Prog. Energy Combust. Sci. 34, 725–754 (2008).

Su, X. et al. Optimizing biomass combustion in a 130 t/h grate boiler: Assessing gas-phase reaction models and primary air distribution strategies. Appl. Therm. Eng. 238, 122043 (2024).

Skrifvars, B. J., Backman, R., Hupa, M., Salmenoja, K. & Vakkilainen, E. Corrosion of superheater steel materials under alkali salt deposits. Part 1: The effect of salt deposit composition and temperature. Corros. Sci. 50, 1274–1282 (2008).

Kinnunen, H. The role and corrosivity of lead in recycled wood combustion. Ph.D. thesis, Åbo Akademi University (2019).

Dunham, J. T., Rampacek, C. & Henrie, T. A. High-sulfur coal for generating electricity. Science 184, 346–351 (1974).

Moskovits, P. Low-temperature boiler corrosion and deposits—A literature review. Ind. Eng. Chem. 51, 1305–1312 (1959).

Frandsen, F. et al. Low-temperature ash deposit formation and corrosion in biomass-fired combined heat and power production boilers. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Effects of Coal Quality on Power Plant Management: Ash Problems, Management and Solutions (EPRI, 2001).

Alzueta, M. U., Bilbao, R. & Glarborg, P. Inhibition and sensitization of fuel oxidation by SO2. Combust. Flame 127, 2234–2251 (2001).

Fleig, D. et al. Measurement and modeling of sulfur trioxide formation in a flow reactor under post-flame conditions. Combust. Flame 160, 1142–1151 (2013).

Hindiyarti, L., Glarborg, P. & Marshall, P. Reactions of SO3 with the O/H radical pool under combustion conditions. J. Phys. Chem. A 111, 3984–3991 (2007).

Jørgensen, T. L., Livbjerg, H. & Glarborg, P. Homogeneous and heterogeneously catalyzed oxidation of SO2. Chem. Eng. Sci. 62, 4496–4499 (2007).

Srivastava, R. K., Miller, C. A., Erickson, C. & Jambhekar, R. Emissions of sulfur trioxide from coal-fired power plants. J. Air Waste Manag. Assoc. 54, 750–762 (2004).

Guo, J. et al. Effect of HCl and CO on sulfur trioxide formation mechanisms during oxy-fuel combustion. Fuel Process. Technol. 174, 95–103 (2018).

Glarborg, P., Kubel, D., Dam-Johansen, K., Chiang, H. M. & Bozzelli, J. W. Impact of SO2 and NO on CO oxidation under post-flame conditions. Int. J. Chem. Kinet. 28, 773–790 (1996).

Marier, P. & Dibbs, H. P. The catalytic conversion of SO2 to SO3 by fly ash and the capture of SO2 and SO3 by CaO and MgO. Thermochim. Acta 8, 155–165 (1974).

Whittingham, G. The corrosive nature of combustion gases. Anti-Corros. Methods Mater. 1, 182–193 (1954).

Flint, D. & Kear, R. W. The corrosion of a steel surface by condensed films of sulphuric acid. J. Appl. Chem. 1, 388–393 (1951).

Downmore, M., Jambwa, S. D. & Kusaziwa, K. P. Trends in the control of NOx and SOx combustion emissions: Implications to the design of fluidised bed combustion operations. Proc. Inst. Mech. Eng. Part E J. Process Mech. Eng. 231, 349–358 (2017).

Glarborg, P. & Marshall, P. Mechanism and modeling of the formation of gaseous alkali sulfates. Combust. Flame 141, 22–39 (2005).

Iisa, K., Lu, Y. & Salmenoja, K. Sulfation of potassium chloride at combustion conditions. Energy Fuels 13, 1184–1190 (1999).

Kassman, H., Bäfver, L. & Åmand, L. E. The importance of SO2 and SO3 for sulphation of gaseous KCl - An experimental investigation in a biomass fired CFB boiler. Combust. Flame 157, 1649–1657 (2010).

Aho, M., Paakkinen, K. & Taipale, R. Destruction of alkali chlorides using sulphur and ferric sulphate during grate combustion of corn stover and wood chip blends. Fuel 103, 562–569 (2013).

Wu, H. et al. Modeling of ferric sulfate decomposition and sulfation of potassium chloride during grate-firing of biomass. AIChE J. 59, 4314–4324 (2013).

IEA Bioenergy Baxter, L. Biomass impacts on SCR catalyst performance. Report Task 32, 1–89 (2005).

Toba, K., Suzuki, T., Kawano, K. & Sakai, J. Effect of relative humidity on ammonium chloride corrosion in refineries. Corrosion 67, 0550051–0550057 (2011).

Yarom, M. & Marmur, A. Capillary condensation with a grain of salt. Langmuir 33, 13444–13450 (2017).

Peng, C., Chen, L. & Tang, M. A database for deliquescence and efflorescence relative humidities of compounds with atmospheric relevance. Fundamental Res. 2, 578–587 (2022).

Vainio, E., Brink, A. & Hupa, L. Low-temperature corrosion caused by alkali phosphate containing particulates in biomass conversion. In the 3rd Annual Meeting of the SMARTCATs COST Action (2017).

Alcántara, J. et al. Marine atmospheric corrosion of carbon steel: A review. Materials 10, 406 (2017).

Li, X., Gupta, D., Eom, H. J., Kim, H. K. & Ro, C. U. Deliquescence and efflorescence behavior of individual NaCl and KCl mixture aerosol particles. Atmos. Environ. 82, 36–43 (2014).

Kelly, J. T. & Wexler, A. S. Water uptake by aerosol: Water activity in supersaturated potassium solutions and deliquescence as a function of temperature. Atmos. Environ. 40, 4450–4468 (2006).

Brunner, T., Obernberger, I., Ramerstorfer, C. & Kanzian, W. Evaluation of the low-temperature corrosion potential of flue gases from the combustion of wood and non-wood fuels. In Proceedings of the 26th European Biomass Conference and Exhibition (EUBCE) 430-439 (2018).

Lu, Z. et al. Experimental research on the effect of acid and ash deposition on heat transfer characteristics of PTFE-coated 3-D finned tube. Int. J. Therm. Sci. 193, 108544 (2023).

Mannisto, T. Korrosion orsakad av delikvescent ZnCl2 i förbränning av sidoströmmar (Original title in Swedish; English translation: Corrosion caused by deliquescent ZnCl2 in the combustion of side streams). Master’s thesis, Åbo Akademi University, (2023).

Vainio, E. et al. Impact of boiler load and limestone addition on SO3 and corrosive cold-end deposits in a coal-fired CFB boiler. Fuel 304, 121313 (2021).

Jozewicz, W. & Gullett, B. K. Reaction mechanisms of dry Ca-based sorbents with gaseous HCl. Ind. Eng. Chem. Res. 34, 607–612 (1995).

Alipour, Y. High temperature corrosion in a biomass-fired power boiler reducing furnace wall corrosion in a waste wood-fired power plant with advanced steam data. (Licentiate thesis, KTH Royal Institute of Technology, 2013).

Laursen, K., Frandsen, F. & Larsen, O. H. Ash deposition trials at three power stations in Denmark. Energy Fuels 12, 429–442 (1998).

Kleinhans, U., Wieland, C., Frandsen, F. J. & Spliethoff, H. Ash formation and deposition in coal and biomass fired combustion systems: Progress and challenges in the field of ash particle sticking and rebound behavior. Prog. Energy Combust. Sci. 68, 65–168 (2018).

Adewuyi, Y. G. & Carmichael, G. R. A theoretical investigation of gaseous absorption by water droplets from SO2-HNO3-NH3-CO2-HCl mixtures. Atmos. Environ. 16, 719–729 (1982).

Koech, L. et al. Spray drying absorption for desulphurization: A review of recent developments. Clean. Technol. Environ. Policy 23, 1665–1686 (2021).

Karimi, M., Shirzad, M., Silva, J. A. C. & Rodrigues, A. E. Carbon dioxide separation and capture by adsorption: A review. Environ. Chem. Lett. 21, 2041–2084 (2023).

Kiang, Y. H. Predicting dew points of acid gases. Chem. Eng. 88, 127 (1981).

Stull, D. R. Vapor pressure of pure substances. Organic and inorganic compounds. Ind. Eng. Chem. 39, 517–550 (1947).

Richardson, G. M. & Malthus, R. S. Salts for static control of humidity at relatively low levels. J. Appl. Chem. 5, 557–567 (1955).

Turgoose, S. Post-excavation changes in iron antiquities. Stud. Conserv. 27, 97–101 (1982).

Zevenhoven, M., Yrjas, P., Skrifvars, B. J. & Hupa, M. Characterization of ash-forming matter in various solid fuels by selective leaching and its implications for fluidized-bed combustion. Energy Fuels 26, 6366–6386 (2012).

Greenspan, L. Humidity fixed points of binary saturated aqueous solutions. J. Res Natl Bur. Stand Sect. A Phys. Chem. 81 A, 89–96 (1977).

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by the Research Council of Finland (Properties and behavior of deliquescent salts and deposits in biomass and waste thermal–conversion - Towards improved efficiency and reliability, Decision No. 333917). The authors also thank the High-Temperature Processes and Materials Group at Åbo Akademi University for providing resources and technical support. The authors acknowledge the funding provided for the article processing charge (open access fee) from Gösta Branders research fund, Åbo Akademi University Foundation (Gösta Branders forskningsfond, Stiftelsen för Åbo Akademi).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

F.J. was responsible for the original draft preparation, investigation, visualization, and for performing the literature review. E.V. contributed to writing, review and editing, supervision, funding acquisition, and conceptualization. L.H. was involved in writing, review, and editing. M.H. contributed to writing, review and editing, and conceptualization.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Jafarihonar, F., Vainio, E., Hupa, L. et al. Low-temperature corrosion in large-scale biomass boilers. npj Mater Degrad 9, 108 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41529-025-00640-4

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41529-025-00640-4