Abstract

Incongruent corrosion of silicate glass is modeled as a moving-boundary transport problem, where the moving boundary contributes convective transport and the ion exchange provides diffusive transport. Here, the convection-diffusion transport equation is solved with two models—one couples the moving boundary to the diffusion process while the other has an independent moving boundary trajectory. These models are shown to replicate the aqueous corrosion of soda lime silica (SLS) in neutral and acidic conditions. The sigmoidal sodium concentration profiles at the glass surface are explained by the Gaussian convolution caused by experimental methods, not by a concentration-dependent diffusion coefficient. By fitting the experimental data with physically meaningful transport models, the driving force for the diffusion and leaching of sodium from the glass is found to be the ingress of hydrous species into the SLS glass (H2O in neutral condition and H+ in acidic condition), instead of the concentration gradient of sodium.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Silicate glass is a commonly used material in architecture, food storage, electronics, and even art1,2. Its widespread use is attributed to its robust chemical resistance, decent mechanical properties, and relatively low melting temperature, all of which are fine-tuned with the cations added as network modifiers3,4. However, these network modifiers also complicate attempts to understand the surface properties of silicate glass, especially its chemical durability in aqueous environments4,5,6,7. Understanding this behavior is of principle importance in a variety of applications, including nuclear waste vitrification, architectural applications, display panel fabrication, and the stability of food and beverage storage containers8,9,10,11,12.

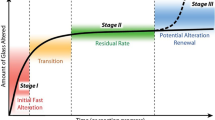

In general, when exposed to aqueous solution, three different types of processes occur at the glass surface: dissolution of the network, preferential leaching/ion exchange of network modifiers, and/or the formation of a gel layer due to the ingress of water. It is known that for silicate glasses, the relative rates of these three processes are strongly dependent on the initial composition of the untreated glass and the pH of the aqueous solution13,14. For example, when International Simple Glass (ISG), a six-component model glass designed for aqueous corrosion studies of nuclear waste glass, is treated in neutral and basic conditions, boron will preferentially dissolve out of the glass network, forming large pores which facilitate further transport of water10,14,15,16,17. This porous gel layer has been shown to undergo structural reorganization as the corrosion proceeds, and is hypothesized to eventually form a passivation layer14,15,16. This has been offered as a factor contributing to the transition from Stage I with a rapid initial corrosion rate to Stage 2 with a significantly decreased mid-stage corrosion rate13. Another contributing factor for the transition from Stage I to Stage II corrosion is the change in the concentration of the dissolving ions in solution. However, it has been shown that the silicate network will still corrode from ISG into a solution pre-saturated with amorphous silica14.

Within this work, leaching refers to incongruent depletion of components from the glass network as a direct result of the reaction of hydrous species, while dissolution refers to congruent break-down of the glass network. Corrosion and alteration then encompass the totality of congruent and incongruent behavior, with the former generally describing the phenomenon with the latter typically referring to the total depth.

While aqueous corrosion of ISG has been extensively studied due to the significance of this system to the important application of nuclear waste vitrification, much less effort recently has been focused on characterizing the corrosion behavior of soda lime silica (SLS), which is extensively used in industry. Understanding the corrosion behavior of SLS is important since its surface corrosion has a significant impact on the chemical and mechanical durability of SLS5,18,19. Much of the early work interrogating the reaction of glass with water investigated the corrosion behavior using either post-corrosion solution analysis or by analyzing the glass surface of the remnant monolith, but rarely were both methods used in the same study20,21,22. Nevertheless, some aspects of the corrosion behavior of SLS can be stated with confidence. In acidic conditions, sodium will be incongruently leached from the glass network22,23,24,25. The sodium-leached surface layer will undergo some structural changes, resulting in a glass network which is more “silica-like”26,27. This network has Si-O bond length and Si-O-Si bond angle distributions more similar to silica than uncorroded SLS. During sodium leaching, water will ingress into the glass network. Note that “water” here does not refer only to H2O, instead it includes all chemical species that originate from water (such as H+, H3O+, OH-). As such, in this work these species will be called “hydrous species” to be more accurate and inclusive.

In highly acidic conditions, such as at pH 1, it was often assumed that dissolution of the silicate network in SLS is negligible5,18,19. This assumption is reasonable at the very early stage of corrosion if the dissolution rate is much smaller than the diffusion rate and there is no sign of a visually identifiable gel layer on the sample retrieved from the solution. While significant gel layer formation can be easily ruled out by visual inspection, the impact of dissolution cannot be disregarded as the solution treatment time increases. An example is shown in Figure S1 in the Supplementary Information (SI) section. During initial investigations of the pH 1 treated samples using X-ray photoelectron spectroscopy (XPS), tin was often detected on the air side of the glass. While there is little tin intentionally added as a component during batching of this glass, tin contamination is still present in most float glasses manufactured using the Pilkington float process. During manufacturing, the glass melt is floated on top of a bed of molten tin, which will diffuse into the side of the glass which is “face-down” on the molten tin28,29,30,31. The “face-up” side of the glass, which is called the air side, will not have any tin contamination after processing. The presence of the characteristic Sn 3d5/2 and 3d3/2 peaks on the XPS spectra of the air side of the SLS glass immersed in a pH 1 solution for 120 days means that there must be substantial dissolution of the tin side and re-adsorption of tin ions on the air side during batch treatment. It should be noted that previous work looking at samples treated in a similar manner for 5 days showed no Sn 3 d peaks above the noise level, supporting that the dissolution is negligible at early times32. While there is a great deal of work which seeks to understand the fundamental causes of these processes, much less work has been done on developing the transport models needed to comprehensively analyze the overall corrosion behavior.

The two most frequently utilized models to understand incongruent corrosion of modifier ions in glass are Fick’s second law of diffusion and the Doremus model of interdiffusion. For Fickian diffusion in a semi-infinite medium, analysis of the release rate of ions from the glass is often done with a simple scaling equation:

where \(x\) is the characteristic diffusion depth (often described in the glass field by the equivalent dissolution thickness or the average leaching depth), \({\mathcal{D}}\) is the diffusion coefficient, and \(t\) is time33,34. Thus, if the average leaching depth follows a square root of time (t1/2) relationship, then the leaching is said to be Fickian and diffusion controlled. The ubiquity of this model is attributed to its conceptual simplicity and ease of application. There are no requirements to fit or solve differential equations to yield a diffusion coefficient for leaching data using this model. However, this simplicity can result in oversights in fundamental understanding of glass corrosion behaviors. This simple scaling for diffusion depth can only be applied to a system if the matrix through which the ions are diffusing is unaltered. In other words, if there is significant dissolution or swelling of the glass surface layer, Eq. (1) will not accurately describe the system. Even if the diffusion depth of leached ions follows a t1/2 dependence, Eq. (1) will be inadequate if the glass network is changing with time. This means the leaching of modifier ions that is accompanied by network dissolution or gel layer formation cannot be explained by the simple relation in Eq. (1).

The second model frequently used to describe the leaching of modifier ions from a glass is the Doremus model of interdiffusion35. This model considers charge neutrality by accounting for the in-diffusion of hydrous species (either protons (H+) or hydronium (H3O+) ions) and the out-diffusion of sodium ions from the glass. This consideration provides an improvement over Eq. (1), namely that the Doremus model of interdiffusion can separate the diffusion coefficients of the counter-diffusing species. However, this model has several pitfalls. First, the model was derived for a constant corrosion rate35,36. This means that if the corrosion rate is not constant with time, such as due to the growth of a passivating gel layer, the diffusion rate will deviate from the predictions of the model. Secondly, the original work provided two solutions for the formulation; one in the early time regime where dissolution rate is negligible compared to the diffusion, and the other at steady state after a long time of treatment where the leaching and dissolution rates are comparable36. This inherently limits its applicability to any system that is not at the steady state. Moreover, the model uses a concentration-dependent interdiffusion coefficient, which was introduced as an umbrella term to cover any changes in the diffusion process occurring as a byproduct of the hydration of the glass35. The introduction and use of the concentration-dependent diffusion coefficient warrants additional discussion.

The concentration-dependent diffusion coefficient was first applied to glass to explain their reaction with an aqueous solution while studying leaching of sodium from glass in neutral water, where the concentration dependence was cited as the cause of the sigmoidal shape of the concentration profiles37. This dependence encompassed any potential structural changes which may occur in the glass as a result of incongruent corrosion into a single term. This term includes effects from structural reorganization, pore formation, differences in transport mechanisms, and even bulk stresses caused by the diffusion35,37. The effective diffusion coefficient for a given process is fundamentally a function of the chemical potential of the diffusing ions33,34. Thus, the effective diffusion coefficient will depend on various factors including the structure of the surrounding matrix, electrostatic effects, concentration differences, crystalline phases, temperature, and processing history. The core assumption of the original concentration-dependent diffusion coefficient is that all the factors which influence the diffusion coefficient are fully explained as a function of the concentration of the diffusing species. In the intervening years, greater fidelity has been brought to understanding the origin of the concentration dependent interdiffusion coefficient as a byproduct of imposing charge neutrality of two different exchanging species38,39,40,41.

In the work by Boksay et al.37 where the concentration dependence was first applied to the glass/water system, however, it lacked this theoretical justification, and was primarily used to fit the model concentration curves to the sigmoidal shape yielded by the experimental data. However, the sigmoidal shape is very common in experimental concentration profiles. This shape is not necessarily representative of concentration dependent physical behavior, as can be well explained by convolution of data from experimental artifacts. Even a layered sample with atomically sharp interfaces exhibits the same sigmoidal shape (theoretically, the error function) when analyzed with sputter depth profiling42,43,44. Additionally, there is ample literature showing that the sigmoidal curvature will vary significantly based on the acquisition parameters45,46. The curvature in these works are due to the convolution of various factors, including surface roughness, non-homogenous profiling craters, and the intrinsic width of the probe method used. All of these artifacts will also convolute the data collected for ion-exchange of silicate glass. Without first accounting for these experimental artifacts, any concentration/phase dependence which is applied to the diffusion data can be questioned, regardless of how close the model may match the data.

As the corrosion behavior of SLS is neither adequately modeled by simple scaling for time-dependent diffusion length of a single species given by Eq. (1) nor captured by the Doremus model of interdiffusion, a new model is required to understand the glass corrosion behavior more accurately. In this paper, we develop transport models under two constraints which are directly relevant to physical processes taking place in SLS in two different pH conditions (neutral and acidic). In the first part of the Results section, two solutions are presented for the convection-diffusion equation — (i) in a system where the convection process is coupled with the diffusion process, which admits a similarity solution, and (ii) in the case where the convection and diffusion occur independently, which is solved numerically. In both cases, the diffusion coefficient is invariant with concentration and governed by the driving force of the main diffusion species, which is accompanied by the displacement and movement of counter-diffusing ions to meet charge neutrality. In addition, we present an algorithm that enables comparison of the theoretical concentration profile with the sigmoidal concentration profile observed in the experimental studies, which involves convolution with intrinsic artifacts associated with the depth profiling experiment as modeled by a simple Gaussian curve35,43.

The Results section then includes a section on Applications of the two models to understand corrosion of SLS glass. In Part 1, we show that the similarity solution can fully explain the experimental data reported by Lanford et al.35 for corrosion of SLS in a neutral pH with a constant diffusion coefficient. In Part 2, we demonstrate that the leaching of sodium from SLS in a pH 1 solution of nitric acid can be satisfactorily modeled by the numerical solution with a constant dissolution rate. In Part 3, we show that pre-saturating the solution with NaCl has a negligible impact on the diffusion and leaching of sodium ions from SLS into the solution; instead, a small decrease in leaching depth is the consequence of an enhancement of the dissolution process. Finally, in the Discussion section, we discuss the physical insights obtained by analyzing the experimental data with the newly developed convection-diffusion models. Conventionally, it was thought that sodium leaching from SLS is driven by the concentration gradient of sodium across the glass/solution interface. However, the analysis of experimentally observed concentration profiles with the transport model developed in this paper shows that the primary driving force is the ingress of hydrous species into the glass—H2O in neutral solution and H+ in acidic solution—while the diffusion and leaching of sodium ions occurs as a secondary process to maintain charge neutrality.

Results

General model development

Formulation of the theoretical model begins with the unsteady diffusion equation for one-dimensional diffusion of a single species in a semi-infinite domain:

where the concentration \(c\left(x,t\right)\) is a function of both position \((x)\) and time \(\left(t\right)\), and \({\mathcal{D}}\) is the diffusion coefficient of the primary diffusing species. Based on the principle of charge neutrality, an interdiffusion process can still be modeled by the diffusion of single species, since the movement of the counter-diffusing ion is coupled with the driving force for diffusion of the primary ion. Equation (2) can be used to describe leaching behavior when the glass matrix is static with time (i.e., no change in the network structure), given the initial and boundary conditions:

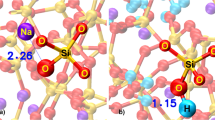

which correspond to a semi-infinite domain initially at a bulk concentration \(\left({c}_{{Bulk}}\right)\). Figure 1a provides a visual representation of the situation where such a simple Fickian model would capture the entire corrosion behavior of a glass. While such systems with truly no dissolution or swelling of the leached layer are rare, this simple model can still be used to describe early-time behavior wherein structural changes and/or dissolution of the leached layer is negligible.

a Diffusion into a semi-infinite domain with no moving boundary, b moving boundary that is coupled with the interdiffusion process, c moving boundary which is uncoupled from the diffusion process. The vertical scale of each figure is scaled from 0 to the bulk concentration. In the current study, b is physically relevant for a glass forming a gel layer on the surface, and c is for a glass dissolving in solution.

The ingress of water from the solution phase can cause swelling of the external region of the glass. This leads to the formation of a gel layer on top of the leached glass. If the gel layer is sufficiently hydrated, then the sodium ions leaching from the glass can move rapidly through the gel layer, resulting in negligible concentration of sodium in the gel layer. This is schematically illustrated in Fig. 1b. In contrast, when dissolution of the leached layer occurs, the solution/glass boundary itself moves with time, as shown in Fig. 1c. Both systems represent moving-boundary transport problems, where the concentration of the diffusing species is effectively zero at a location that moves in time due to either gel layer growth or network dissolution. In both cases, analysis of the transport problem can be simplified by introducing the coordinate system transformation:

where \(\eta \left(t\right)\) is the position of the moving boundary (either the gel-layer/leached layer interface or the solution/leached layer interface). Thus, the equation governing the concentration distribution \(c\left(s,t\right)\) becomes:

where \(\frac{d{\eta }}{{dt}}\) represents the velocity of the moving boundary.

Moving boundary due to gel layer formation on the glass

When modeling the growth of the gel layer on the surface of the glass (Fig. 1b), it is important to realize that the interdiffusion of aqueous species from the solution and modifier ions from the glass is coupled with the growth of the gel layer. This suggests that the displacement of the gel layer/leached layer interface in time is scaled with the diffusion length scale \(\sqrt{{\mathcal{D}}t}\) as shown in Eq. (1). Thus, for the system shown in Fig. 1b, we look for a similarity solution, \(\bar{c}\left(\bar{s}\right)\), by introducing the dimensionless variables:

where \(\gamma\) is a dimensionless constant. Upon further mathematical manipulations (shown in SI 2), the unsteady diffusion equation in the moving frame of reference is transformed into an ordinary differential equation:

with associated boundary conditions:

This yields the similarity solution in the moving frame:

which can be rewritten in a fixed frame as:

where \({erf}\) is the error function. This provides an analytical prediction for the time-dependent concentration distribution of the main diffusing species in a glass that forms a gel-layer. The concentration distribution of the counter-diffusing species is simply \(1-\bar{c}\left(x,t\right)\).

Moving boundary due to dissolution of the sodium-leached layer

In contrast to the system with gel-layer formation, where the motion of the moving boundary is coupled to the transport of the diffusing species, the dissolution rate of the sodium-leached layer is entirely uncoupled from the diffusion process in this case. This precludes the development of an analytical solution. Here, we will consider a case where the dissolution rate of the sodium-leached network \((\frac{d\eta }{{dt}}=U)\) is expected to be constant over the entire duration of experiment. Then, the governing equation becomes:

with the following initial and boundary conditions:

Equation (16) is solved using the method of lines, with the spatial derivatives approximated using 3-point central differences and the resulting differential-algebraic system marched in time using Euler’s method47. The Python code solving Eq. (16) with sufficiently small discretization and time steps for error control is provided in plain text in SI 7.

Effect of experimental artifacts on the theoretical concentration profiles

As discussed in the Introduction section, artifacts arising from inherent limitations of the experimental methods employed must be considered to compare the concentration profiles predicted by the theoretical models with experimental data. In the case of nuclear reaction analysis (NRA), the method originally used by Lanford et al. to measure hydrogen concentration profiles35, the stopping distance of impinging ions will have a Gaussian distribution42,45,46. The spread of this Gaussian distribution will increase as the ion energy increases and thus the mean position of the stopped ions in the glass increases. In other words, the detection signal becomes wider as the NRA method probes deeper into the glass. In the case of depth profiling with sputtering followed by elemental analysis using XPS or time-of-flight secondary ion mass spectrometry (ToF-SIMS), the signal will be convoluted by interlayer mixing, preferential sputtering, and surface roughness, all of which will cause the measured concentration profile to deviate from the theoretically predicted concentration profiles43,48. The impact of these sputter-induced effects can also be modeled by convolution with a Gaussian distribution function, where the width of the Gaussian curve will be larger as the sample is sputtered more, to model the increased interface width42,45,46.

The general procedure for convolution of a theoretical profile, \(T\left(x,t\right)\), with a Gaussian distribution, \(G\left(x,{x}_{0}\right)\), where \({x}_{0}\) is the mean position of the distribution, to yield an experimental profile, \(E\left({x}_{0},{t}_{n}\right)\), can be represented by:

This operation is conducted at a given time \({t}_{n}\). More details about the computational procedure as well as a graphical illustration of the convolution process are provided in the Methods section.

Applications Part 1: Moving boundary due to gel layer formation of SLS in neutral water

To properly and accurately re-analyze the corrosion data reported by Lanford et al.35, it is necessary to know the physical state of the SLS glass surface corroded in neutral pH conditions. For that purpose, SLS glass with a composition similar to the one studied by Lanford et al.35 was corroded in the same conditions. The surface of the sample immediately after retrieval from the solution looked like a swollen gel with significant roughness (Fig. 2a). Upon drying, the gel layer collapsed which produced a hazy surface; the haziness was due to light scattering from the dried surface which was topographically rough. This suggests that the sample should be physically described by the similarity solution, Eq. (14).

a Pictures of a representative sample of SLS after 21 days of treatment in neutral water, before and after drying. The high roughness seen while the sample is wet is due to the swollen gel layer, which creates a hazy surface when dried, and can be seen in the 3D optical profilometry scan. b Hydrogen concentration profiles replotted from Lanford et al.35. c Log-Log plot of the total alteration depth of SLS in neutral water from Lanford et al. and the leaching depth of SLS in a pH 1 solution of nitric acid (this work) taken from the depth at which the concentration is 50% of the bulk. The error bars on the pH 1 data are the standard errors based on at least 3 replicate experiments.

The total alteration depth from the data provided in the original paper by Lanford et al.35 was extracted and re-plotted in Fig. 2b. Note that this figure shows the hydrogen concentration profile measured via NRA, which was then fit using the Doremus model of interdiffusion. Separately in that same work, it was shown that the H:Na ratio was 3:1 in the surface region of the treated glass35, which led to the hypothesis of inward diffusion of hydronium ions (H3O+) exchanging with outward diffusing sodium ions (Na+). It is impossible to ascertain if this ratio pertains to the swollen gel layer before it is removed from the solution; the actual H:Na ratio during treatment will probably be even larger due to excess water which will desorb from the gel network during sample drying and characterization under vacuum. Nonetheless, the requirement for charge neutrality can still be used to relate the profile shown in Fig. 2b to the expected concentration profile of sodium ions which remain in the glass. This can be done by simply normalizing the hydrogen concentrations and then subtracting them from unity. When the time dependence of the 50% depth of the calculated sodium depth profile is plotted in log-log scale, it is found to be well fit to t1/2, as in Fig. 2c. The significance of this exponent will be explained in more detail in the Discussion section.

Using the similarity solution shown in Eq. (14), it was found that the experimental data of the normalized sodium concentration data can be fit with \(\gamma =3.6\) and \({\mathcal{D}}=1\times {10}^{-16}c{m}^{2}/\sec\), as shown in Fig. 3a. Figure 3b shows very good agreement between the 50% concentration depth (from the experimental data of Lanford et al.35) and the model prediction. This value of \({\mathcal{D}}\) is on the same order of magnitude as was previously reported by Lanford et al.35. The fact that the \(\gamma\) value from fitting is larger than 2 has a physical meaning, which will be elaborated in the Discussion section.

a Normalized sodium concentration profiles. The points are from the data reported by Lanford et al.35, and the solid lines are the result of the theoretical calculations using the similarity solution with Eq. (14) with \(\gamma =3.6\) and \({\mathcal{D}}=1\times {10}^{-16}c{m}^{2}/\sec\). The numbers along the top of the plot refer to the length of treatment in days. b Comparison of the 50% depth for the data from Lanford et al. and the similarity solution. The dotted line has a slope of 1, to guide the eyes. c Reproduction of experimental profiles with a sigmoidal shape for 0.16, 1.5, and 13 days of treatment from Fig. 3a, using the similarity solution with Gaussian convolution described by Eq. (20), with the value used for \(\sigma\) in Eq. (29) shown on the plot.

It is clear, however, that the shape of the profile from the similarity solution does not match the sigmoidal shape exhibited by the experimental data, which was the original justification for the concentration-dependent diffusion coefficient35,37. This mismatch should not, however, be attributed to an insufficiency of the model. The sigmoidal shape of the experimental data mostly originates from an intrinsic artifact of the characterization techniques used. While Lanford et al. mentioned the Gaussian detection range in their original paper35, it was not accounted for it in the data analysis. As shown in Fig. 3c, when the analytical similarity solution is corrected with the Gaussian convolution process using Eq. (20), not only does the profile resemble the expected sigmoidal shape, but reasonable agreement is reached between the model data and the experimental data. It should be noted that to achieve the best agreement between the similarity solution and the experimental data, the width of the Gaussian profile must be increased gradually as the sampling depth increases. This makes sense as a thicker gel layer will correlate to more pronounced surface roughness when dried. This increase in surface roughness will inevitably result in an increase in the spread of the Gaussian detection signal. Even if the sample surface were atomically flat, the distribution of the stopping distance will become wider as the kinetic energy of the probing ion increases49. In this first-order correction, all such experimental non-idealities can be grouped together into the width of the Gaussian distribution. Additionally, at this stage of investigation, the models are fit by inspection to avoid overfitting. Future work will investigate both a fine-grained breakdown of the factors which influence the width of the Gaussian distribution and will pair this insight with a multivariate regression fitting model.

In summary, after applying a simple correction, the leaching behavior of sodium from SLS in neutral water can be well explained with a constant diffusion coefficient. By scaling the growth of the gel layer with the interdiffusion length, the resulting similarity solution fully replicates the corrosion behavior of SLS in neutral pH conditions. Additionally, the sigmoidal shape of the experimental data can be well explained as resulting from experimental artifacts, which can be reasonably approximated using a simple Gaussian convolution process.

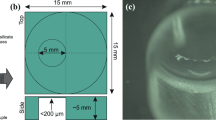

Applications Part 2: Moving boundary due to dissolution of leached layer in acidic solution

The first step in understanding the corrosion behavior of SLS in acidic conditions is characterizing the dissolution of the glass network. Figure 4a shows the equivalent dissolution thickness for each element evaluated by ICP analysis of the solution after acid treatment for varying treatment times, using Eq. (25). The results clearly show that calcium, magnesium, and silicon all corrode congruently, since the equivalent dissolution thickness as calculated from their post-treatment solution concentrations yields comparable values, within the spread of the experimental error. In contrast, sodium is clearly corroded incongruently in this sample, as it is the only element that yields an equivalent dissolution thickness significantly larger than that of all other elements. The raw ICP data can be found in SI 3. Visual inspection of the glass samples retrieved from the solution showed no sign of a gel layer (Fig. 4b), and the glass surface appeared smooth upon drying.

a Equivalent dissolution thickness for SLS treated in a pH 1 solution of nitric acid. The symbols represent the equivalent dissolution thickness calculated from the ICP data of individually marked element, and the dashed lines are the resulting fit to the shown equations. The raw ICP data can be found in SI 3. b Pictures of a representative sample of SLS after 60 days of treatment, before and after drying. The high clarity of the sample when dried, as well as the low roughness shown in the 3D optical profilometry scan, supports that the surface of the sample is smooth and does not have a gel layer.

Linear regression of the congruently corroded dissolution thickness with time yields a dissolution rate \(\left(U\right)\), which is the velocity of the moving boundary. For this system, the sodium-leached layer dissolves at a rate of \(2.21\) nm/day, corresponding to \(2.56\times {10}^{-12}\) cm/sec, which is less than \(1\) Å/hr. A Pearson correlation coefficient of 0.97 for the linear regression model indicates that the dissolution rate of the SLS glass is constant over the entire experimental duration. While a constant corrosion rate has been reported previously for silicate glass, it should be noted that this assumption may not hold at longer treatment times, as the concentration of the solution continues to change8,35.

From examination of the equivalent dissolution thickness of sodium (Fig. 4a), it appears that the time-dependence of the sodium leaching depth can be fit well to t1/2. Despite this apparently reasonable agreement with a characteristic length scale for diffusion from Eq. (1), it should be reiterated that this does not imply that the leaching behavior can be fully described as diffusion controlled. As previously discussed, the diffusion length scale can be used to model leaching when there is no motion of the glass/solution interface. The presence of calcium, silicon, and magnesium in solution, as well as tin adsorption on the air side of the sample after treatment (as shown in Figure S1), are all indicative of dissolution of the glass matrix. This means that the solution/glass boundary is moving (as shown in Fig. 1c) and its motion cannot be assumed to be negligible. In other words, diffusion is not occurring relative to the original solution/glass boundary as shown in Fig. 1a. Additionally, calculation of the equivalent dissolution thickness assumes that the entire corroded region is uniformly depleted in the element under consideration. Depth profiling has shown that there is a concentration gradient of sodium in the surface of the glass after acid treatment (for example, see Fig. 5a). Thus, any trend based on the equivalent dissolution thickness of an ion which is incongruently leached will inherently be convoluted by this assumption, resulting in the total alteration depth being systematically under-estimated5,23,24. Instead, as shown in the Discussion section, the t1/2 dependence is simply an early behavior of the convention-diffusion process with a constant dissolution rate that is relatively smaller than the diffusion rate.

a XPS sodium depth profiling results for SLS treated in pH 1 solution of nitric acid. The dots are representative experimental data, while the shaded regions bound by lines represent the average spread of at least 3 repeat measurements. Full XPS depth profiling data for sodium can be found in SI 5. The numbers on the plots are the treatment time in days. Also shown for comparison is the data for a sample fractured in-situ in the vacuum of the XPS chamber (brown squares). b Theoretical concentration as calculated from the model with a constant dissolution rate, with \(U=2.56\times {10}^{-12}{cm}/\sec\) and \({\mathcal{D}}=5.5\times {10}^{-17}c{m}^{2}/\sec\). c Demonstration of experimental profiles with a sigmoidal shape for 7, 30, and 120 days of treatment from Fig. 5a, using the constant dissolution rate model with Gaussian convolution described by Eq. (20), with the value used for \(\sigma\) in Eq. (29) shown on the plot. The convoluted profiles were shifted by approximately \(2\sigma\) to ensure they pass through (0,0).

Figure 5a shows the XPS depth profile for sodium from SLS treated in pH 1 solutions of nitric acid at 90 °C for various lengths of time. Since XPS depth profiling is performed on samples after treatment, the zero-depth point in these measurements corresponds to \(s=0\) (not \(x=0\)), as shown graphically in Fig. 1c. Included on this plot is the profiling data for a sample which was measured on a piece of glass that was fractured in the vacuum of the XPS chamber. Notice that the sodium signal at the pristine fractured surface is 2.2 times the bulk signal detected after sputtering. This is not actually due to an increased sodium concentration at the surface; the in-situ vacuum fracturing all but assures measuring a uniform, bulk concentration. This apparent sodium concentration gradient is due to the inward migration of sodium ions during the Ar+ sputtering for depth profiling43,44,48,50.

The depth where the normalized concentration reaches 50% of the bulk value is a common metric used to quantify the average leaching depth for samples analyzed with sputter profiling. As such, the 50% leaching depths for these experiments are plotted as a function of time in Fig. 2c, along with the total alteration depths for the Lanford et al. data35. Nonlinear regression of the leaching data yields a power-law dependence on time with an exponent of only 0.39 (R2 = 0.9997), much smaller than the 0.5 value associated with either transient diffusion in a fixed semi-infinite solid (Eq. (1)), or the similarity solution for the moving boundary problem arising from formation of a gel layer. As such, the leaching behavior was modeled via numerical solution of the convection-diffusion equation with a constant dissolution rate. The resulting concentration profiles shown in Fig. 5b were obtained by setting \(U=2.56\times {10}^{-12}\) cm/sec, based on the ICP results shown in Fig. 4a, and varying the diffusion coefficient (\({\mathcal{D}}\)) until good agreement was achieved with the experimental data. Using the computed concentration profiles, the average leaching depth was quantified.

Again, the disparity between the sodium depth profiles from the model and the experimental profiles is due to the absence of experimental artifacts in the computed concentration profiles presented in Fig. 5b, which do influence the experimental data in Fig. 5a. As shown in Fig. 5c, when the model concentration profiles are treated using the Gaussian convolution method (Eq. (20)), good agreement is achieved between the simulation and experimental data for a constant diffusion coefficient of \({\mathcal{D}}=5.5\times {10}^{-17}\) cm2/sec. It should be noted that, just as in Fig. 3c, the width of the Gaussian convolution must be increased as the leaching depth increases to account for the more gradual rise in the data. This increased width can be explained by the same effects listed previously; namely, increased surface roughness with increased sputter time, uneven craters created by preferential sputtering, and charge-induced migration46,48. Mathematical modeling of all possible experimental artifacts is beyond the scope of this study; nonetheless, the data presented in Fig. 5c demonstrate that the sodium leaching data can be well explained with a constant diffusion coefficient after accounting for experimental error.

Figure 6 shows the XPS depth profiles for calcium and magnesium, from the same experiments which yielded the sodium profiles shown in Fig. 5a. Notice that while the sodium concentration profiles vary drastically with time, the calcium and magnesium profiles appear relatively unchanged as the treatment time increases. The uniformity of the calcium and magnesium profiles supports the notion that these two elements corrode congruently with the silicon in this glass system, as shown in the ICP data (Fig. 4a). The calcium and magnesium data are well modeled by the numerical solution of the convection-diffusion equation using the same value of \(U\) as in Fig. 5b, since the glass dissolution is the same for all elements in the glass, but with \({\mathcal{D}}\approx 5.5\times {10}^{-18}\) cm2/sec for calcium and \({\mathcal{D}}\approx 5.5\times {10}^{-19}\) cm2/sec for magnesium. These values of diffusivity are reasonable considering the range of values calculated in the original paper35.

Representative experimental XPS depth profiles for (a) calcium and b magnesium, corresponding to the same treatment times as the sodium leached profiles shown in Fig. 5. Full XPS depth profiling data for calcium and magnesium can be found in SI 5. Also included on both of these profiles is the depth profile (brown squares) for a sample fractured in-situ in the vacuum of the XPS chamber, as well as an arbitrary dotted black line meant to guide the eyes and show the general behavior of the congruent corrosion. Additionally, the results of the constant dissolution rate model with \(U=2.56\times {10}^{-12}{cm}/\sec\) and c \({\mathcal{D}}=5.5\times {10}^{-18}c{m}^{2}/\sec\) and d \({\mathcal{D}}=5.5\times {10}^{-19}c{m}^{2}/\sec\), which is shown to agree well with the calcium and magnesium profiles, respectively.

For comparison, Fig. 7 shows the average sodium leaching, dissolution, and total alteration depths with time for this sample set, with the symbols representing experimental data and the lines showing numerical solutions of the convection-diffusion equation. As previously discussed, the leaching depth is from the 50% concentration depth of the XPS data, with the error bars representing one standard error from repeat experiments. For the concentration profiles generated from numerical simulations, the average leaching depth is quantified using the depth where the concentration is 90% of the bulk value. This metric was chosen as it resulted in good agreement with the experimental profiles after Gaussian convolution. The total alteration depth is the sum of the dissolution thickness and the leaching depths. The excellent agreement shown in this plot between the numerical solutions and the experimental leaching, dissolution, and total alteration depths support that the convection-diffusion model with a constant diffusion coefficient fully describes the dissolution-diffusion process occurring at the SLS glass surface in pH 1 solution. Note that non-linear regression with a power law showed that the total thickness from which sodium ions are leached fits well with an exponent of ~0.5. While similar to the trend seen for sodium in ICP analysis (Fig. 4a), this exponent has a physical meaning which will be examined further in the Discussion section.

Summarized experimental data and model fitting for corrosion of SLS in acidic conditions: Summary of the corrosion behavior for SLS immersed in a pH 1 solution of nitric acid at 90 °C. The dots are from experimental data, either from XPS depth profiling with the error bars representing the standard error calculated after at least 3 replicate samples, or from ICP which is replotted from Fig. 4; the total alteration data is the sum of the averages of the two data. The solid lines are the result of the constant dissolution rate model, with \(U=2.56\times {10}^{-12}{cm}/\sec\) and \({\mathcal{D}}=5.5\times {10}^{-17}c{m}^{2}/\sec\).

Applications Part 3: Corrosion in an acidic solution pre-saturated with NaCl

Often, sodium leaching from SLS is hypothesized to be driven by the difference in the concentrations of sodium in the glass bulk and at the glass surface, with the surface concentration then impacted by the activity of sodium in the solution. If this is the case, the sodium leaching rate will be altered as the sodium concentration in the solution increases. By extension, if the corrosion is conducted in static conditions, then the leaching may appear to halt as the glass/solution reaches a steady state after a long time. The interdependence between the ion activity in the solution and the corrosion of the glass is one of the governing factors considered in the GRALL model, which was developed to model long-term corrosion of ISG and other nuclear waste glasses51. Although there is no term describing such activity dependences in the transport model developed here, it can still account for such a hypothetical decrease in driving force because such a change will be reflected in the terms \(\frac{\partial \bar{c}}{\partial s}\) and \(\frac{{\partial }^{2}\bar{c}}{{\partial s}^{2}}\) in Eq. (16). As such, the proposed hypothesis can be evaluated by studying the leaching and diffusion behavior of sodium from SLS into a pH 1 aqueous solution pre-saturated with NaCl.

Figure 8a shows the average leaching depth for SLS treated in a pH 1 solution with and without NaCl added. Notice that while the average leaching depth does decrease when the solution is pre-saturated with NaCl, the decrease is relatively minor. Additionally, the surface concentration of sodium in the glass sample was nearly zero, even when the solution was pre-saturated with NaCl, as shown in the inset of Fig. 8a (full data set shown in SI 4). It may be argued that, since the nominal concentration of sodium in SLS is 9 M and the saturation concentration of NaCl at 90°C is around 6 M52,53, there is still a concentration difference which could drive sodium to migrate across the glass/solution interface. However, since the sodium ion concentration in the solution is already at the maximum equilibrium level with NaCl solubility at 90 °C, any driving force from the concentration gradient of sodium is significantly reduced relative to the sample with no salt added to the solution. Compared to this large change in the sodium ion activity in the solution phase, the change observed in the sodium ion depth profile in the leached glass is rather marginal.

a Summarized sodium leaching data for SLS treated in a pH 1 solution of nitric acid at 90 °C for various treatment time. The error bars represent standard error, calculated from at least 3 repeat measurements. The full XPS data set can be found in SI 5. Note that for some data points, the error bars are so narrow as to not be visible. Both data sets are fit with an arbitrary power law, shown as a dotted line, demonstrating that they are poorly described by t1/2. The inset shows the average depth profile for both experiment sets at a single time point (60 days), further reinforcing that they are statistically different. b AFM-IR spectra for pristine SLS, and for a sample treated for 120 days in a solution either saturated with NaCl or with no NaCl added. These plots show that though their surface structure is the same, their sodium leaching behavior is different.

In applying the moving boundary model to understand the leaching depth, the two parameters which must be adjusted are \(U\) and \({\mathcal{D}}\). Unfortunately, high ion concentrations in the NaCl-saturated solutions prohibited direct measurement of the post-corrosion solution concentrations via ICP. As previously discussed, \({\mathcal{D}}\) is fundamentally a function of the chemical potential of the primary diffusing ions, which includes interactions between the ions and the remnant silica-rich network. Based on the IR spectra (Fig. 8b) collected with a surface-sensitive mode, which has an effective probe depth of ≤150 nm54, the vibrational spectral features of the sodium-leached surface layers are almost identical after 120 days of treatment in either solution. This implies that the sodium-leached layer has the same remnant structure regardless of the sodium content of the solution. If the same ions are diffusing through the same matrix, then it is reasonable to assume that the effective diffusion coefficient for leaching into the two different solutions is similar. So, in contrast to the approach used for the case with no NaCl added (where \(U\) was known and \({\mathcal{D}}\) was determined), this system was modeled by fixing \({\mathcal{D}}\) and slowly increasing \(U\) until good agreement was reached between model predictions and experimental results.

Figure 9 shows excellent agreement between the experimental leaching data and the numerical solution with \({\mathcal{D}}=5.5\times {10}^{-17}\) cm2/sec and \(U=3.0\times {10}^{-12}\) cm/sec. The agreement between the experimental data and the simulation result suggests that the apparent decrease in the thickness of the sodium-depleted layer in the glass shown in Fig. 8a can be attributed to an increase in dissolution rate, not a decrease in the driving force for Na+/H+ ion-exchange. This result is reasonable, as the dissolution rate of amorphous silica is known to increase in solutions with high concentrations of NaCl55.

Summarized corrosion data for SLS leached in a pH 1 solution of nitric acid pre-saturated with NaCl. The dots are from experimental leaching data from XPS depth profiling, with the error bars representing the standard error calculated after at least 3 replicate samples. The depth profiling data of sodium, calcium, and magnesium are provided in SI 5. The solid lines are the result of the constant dissolution rate calculation, with \(U=3.0\times {10}^{-12}{cm}/\sec\) and \({\mathcal{D}}=5.5\times {10}^{-17}c{m}^{2}/\sec\).

It is still an open question in the field as to what drives the incongruent leaching of alkali ions (such as sodium) from glass into aqueous solutions; namely, whether it is out-diffusion of sodium ions from SLS accompanied by in-diffusion of protons subject to charge neutrality, or vice versa. It is believed that the transport of hydrogen also involves transport of water into the glass network, although it is unknown if this occurs due to hydrogen transport occurring with hydronium ion transport (i.e., Na+/H3O+ exchange), or if the hydration of the glass occurs after preliminary proton transport (Na+/H+ exchange)35. Our data show that the driving force for leaching of sodium from SLS is almost entirely independent of the concentration of sodium in the aqueous solution (at least up to the saturation level of NaCl solubility), which implies that the main driving force for sodium leaching may not be the outward diffusion of sodium ions, but the ingress of protons.

It is generally known in the glass community that the corrosion of glass is impacted significantly by the activity of ions in solution16,55,56,57. Thus, the change in activity of the solution is one of the leading theories behind the transition from stage 1 to stage 2 corrosion of ISG15,16. While, it has previously been demonstrated that silicate glass can still corrode into a solution that is pre-saturated with amorphous silica, the specific rate of the dissolution will vary with concentration14. In a similar manner, our data demonstrate that sodium will continue to leach out of SLS into an acidic solution that is pre-saturated with NaCl, leaving a leached layer that is only slightly thinner than the leached layer formed in a solution with no NaCl added. By using the moving boundary model presented here, we demonstrate that a slight decrease in the leached layer thickness observed in XPS depth profiling can be explained by an increase in the dissolution rate, which can be supported by the known fact that the solubility of silica can be enhanced by the presence of other ionic species in the solution55. This therefore reinforces the use of the convection-diffusion model with a constant diffusion coefficient for a glass with significant dissolution and negligible gel layer formation.

Discussion

This section compares the general behavior of the two moving-boundary models applied to glass corrosion: (i) gel formation where the moving boundary trajectory is coupled with diffusion (Fig. 1b), and (ii) dissolution of the leached layer where the trajectory of the moving boundary is independent from diffusion (Fig. 1c). To that end, we introduce the Péclet number (\({Pe}\)), which is a dimensionless number comparing the relative rates of convection to diffusion. In the case of glass corrosion, the convective contribution originates from the motion of the moving boundary; so, \({Pe}\) can be defined as:

where \(\frac{d\eta }{{dt}}\) is the speed of the moving boundary, \(L\) is the characteristic length, and \({\mathcal{D}}\) is the diffusion coefficient. When \({Pe}\ll 1\), the transport is governed by diffusion. As \({Pe}\) becomes greater than 1, the convective contributions dominate the transport behavior instead. In the case of glass corrosion, this is either gel layer formation or surface dissolution. Using the diffusive characteristic length scale \(\sqrt{{\mathcal{D}}t}\), as in Eq. (1), \({Pe}\) becomes:

for the similarity solution (Fig. 1b), and:

for a system with a constant dissolution rate (Fig. 1c). We can see that \({Pe}\) is constant in time for the similarity solution, while \({Pe}\) will increase with time for the system with a constant dissolution rate. To examine these behaviors in more detail, hypothetical data have been generated using both models for a variety of \({Pe}\) (Figs. 10, 11). For the sake of simplicity, no Gaussian convolution will be performed on these plots. The data presented here is modeling the sodium concentration profile, \({\bar{c}}_{{Na}}\), as that is experimentally measured in XPS or ToF-SIMS depth profiling. The concentration profile of the hydrous species, such as that measured via NRA, can be obtained using charge neutrality, i.e., \({\bar{c}}_{H}=1-{\bar{c}}_{{Na}}\), as long as the H/Na ratio does not vary35.

Normalized concentration profiles as predicted from the (a–d) similarity solution and the (e–h) constant dissolution rate solution as a function of the original glass surface (\(x\) in Fig. 1). The insets in (e–h) show the concentration profile with respect to the moving boundary (solution/glass interface noted as \(s\) in Fig. 1c). Curves of a common color correspond to the same time, with the leftmost red curve corresponding to 0.08 days, the rightmost blue curve corresponding to 120 days of treatment, each line corresponding to a difference of about 10 days, with the arrows indicating the progression of time. Above each plot are the parameters used to generate the data, \(\gamma\) and \({\mathcal{D}}\) for the similarity solution and \(U\) and \({\mathcal{D}}\) for the constant dissolution rate solution.

The average corrosion depth extracted from the calculated profiles in Fig. 10. For the (a–c) similarity solution results, notice that as \(\gamma\) increases, the amount of total alteration and the gel layer thickness both increase, while the leached layer thickness decreases. For the results (d–f) with a constant dissolution rate, the dotted red lines are superimposed to show t1/2. Shown in the table inset in Fig. 11e, Eq. (24) is used to calculate \({t}_{{Pe}=1}\) for each \({\mathcal{D}}\) value, which is then indicated on Fig. 11e, f with a yellow star. Note that no star is present for \({\mathcal{D}}=1\times {10}^{-16}c{m}^{2}/\sec\) and \({\mathcal{D}}=5\times {10}^{-17}c{m}^{2}/\sec\), as their \({t}_{{Pe}=1}\) is significantly larger than the time frame considered in these calculations.

The concentration profiles of the similarity solution with \(\gamma\) = 0.1, 0.6, 1.8, and 3.6 (corresponding to \({Pe}\) = 0.05, 0.3, 0.9, and 1.8, respectively) are shown in Fig. 10a–d. When \({Pe}\ll 1\), the concentration profile is very similar to one-dimensional diffusion into a semi-infinite domain with no convection, as described by Eq. (2). As \({Pe}\) increases, the gel layer thickness increases and the \({\bar{c}}_{{Na}}\) profile from the moving boundary becomes steeper. This increased convection contribution is the reason that the \({\bar{c}}_{H}\) data by Lanford, et al.35 (Fig. 2b) cannot be fit with Eq. (2). As shown in Fig. 3c, the sigmoidal shape is caused by the convolution of the Gaussian profile inherently originating from the experimental method, not because the diffusion coefficient of one species varies with the concentration of the counter-diffusing species.

The analysis of the data from Lanford, et al.35 with the similarity solution (shown in Fig. 3) carries several implications for the corrosion process. First, and most obviously, fitting with \(\gamma =3.6\) means that the overall transport process is not governed by diffusion alone (\({Pe} > 1\)), and the moving boundary-induced convection plays an important role. It should be noted that, though the convection is induced by the moving boundary, it functions as true convective contribution to the transport. In other words, the corrosion behavior of SLS in neutral water is governed by the ingress of the hydrous species forming a gel layer at the surface, while the concentration gradient between the gel layer (moving boundary) and the bulk is due to the subsequent diffusion of hydrous species into the bulk. Secondly, while in this work the similarity solution was fit to the data using a guess-and-check method, since the similarity solution has an analytical form, the experimental depth profiling data could instead be fit using nonlinear regression of Eq. (15) for \({\mathcal{D}}\) and \(\gamma\). To account for the impact of the experimental artifacts, a simple approximation could be to only fit data in the intermediate concentration range (for example, where \(0.3\le \bar{c}\le 0.7\)) where the impact of the Gaussian convolution effect is relatively minor. A more rigorous method would be to perform nonlinear regression with the similarity solution after Gaussian convolution, for \({\mathcal{D}}\), \(\gamma\), and \(\sigma\).

The concentration profiles calculated with four different diffusion coefficients with a constant moving boundary trajectory are shown in Fig. 10e–h. In this case, as noted in Eq. (23), \({Pe}\) will increase with time; the corrosion process is “diffusion-controlled” initially and then becomes “convection-controlled” after some time. The time where the corrosion changes from diffusion-controlled to convection-controlled can be estimated with:

which is the time when \({Pe}=1\). For Fig. 10e, \({t}_{{Pe}=1}\) is significantly larger than the 120 days considered in this plot, so \({Pe}\ll 1\) over the entire duration of the experiment. The behavior therefore resembles that of diffusion into a semi-infinite domain with negligible convective contribution, and is similar to the behavior shown in Fig. 10a. This is the reason that the exponent of the time dependence of the equivalent dissolution thickness from the ICP data of sodium in Fig. 4a is found to be ~0.5. For Fig. 10h, \({t}_{{Pe}=1}\) is about 12 days, so most of the behavior observed over 120 days is dominated by convective contributions.

The insets in Fig. 10e–h show the concentration plots in the moving frame (\(s\)-coordinate in Fig. 1c), which corresponds to the concentration profiles that would be expected if the post-corrosion samples were analyzed by depth profiling, without the Gaussian convolution effect applied. When \({Pe} > 1\) (Fig. 10h), the profile shown in the inset may give a false impression that there is negligible corrosion occurring in the sample, because the concentration profiles do not appear to change significantly with time. However, by examining the behavior in the \(x\)-coordinate system, it is clear that the surface dissolves. This \({Pe} > 1\) behavior could be representative of congruent corrosion, such as for calcium and magnesium shown in Fig. 6a, b. This reinforces the importance of collecting both solution and monolith data after corrosion experiments to fully characterize the corrosion behavior.

In both similarity (Fig. 10a–d) and numerical (Fig. 10e–h) solutions, the concentration profiles become steeper with a high \({Pe}\). Regardless of how the moving boundary is modeled, a convection-dominated process tends to have a steeper concentration gradient in the leached layer. With this behavior in mind, it is interesting to note that this steep concentration gradient is similar to the concentration profile of boron in ISG which was treated in neutral and basic conditions8. This commonality suggests that the transport behavior of ISG is governed by the convective components from the gel layer growth, instead of the diffusive components of ion depletion. This supports the hypothesis that the transition from stage-1 to stage-2 corrosion is primarily a function of factors which impact the convective process, such as changes in gel growth rate due to structural reorganization, instead of factors influencing the diffusion14,15,16. This is similar to previous results demonstrating that the dissolution rate was rate controlling for short-term experiments at a high pH, which is typically used for studies of ISG58. Further work is needed to test this hypothesis with various moving boundary conditions.

In experiments, the averaged corrosion depths are often analyzed instead of full concentration profiles. Figure 11 summarizes the average corrosion depth for both models. Note that for the similarity solution, the gel-layer depth (Fig. 11a), leaching depth (Fig. 11b), and total alteration depth (Fig. 11c) all have a t1/2 dependence. This is because the thickness of the gel layer is inherently tied to the diffusion of mobile species by Eq. (10). As such, the average depth of all three layers should follow a t1/2 dependence regardless of the value of \(\gamma\). The influence of \(\gamma\), and therefore \({Pe}\), can instead be seen in the relative contributions of the gel layer and leached layer thickness to the total alteration depth. When \(\gamma =3.6\) (\({Pe}=1.8\)), the system is dominated by convective contributions induced by gel layer growth. In contrast, when \(\gamma =0.1\) (\({Pe}=0.05\)), the gel layer growth is negligible. When \(\gamma \approx 0.7\), the gel layer thickness is about the same as the average diffusion depth.

For the constant dissolution rate system (Fig. 11d–f), the leaching and total alteration depth will eventually deviate from the t1/2 dependence because \({Pe}\) will approach and exceed 1 as corrosion continues. This behavior is shown in Fig. 11e by a star, which indicates \({t}_{{Pe}=1}\). Initially (\({Pe}\ll 1\)), the leached layer thickness follows a t1/2 dependence. But, as \({Pe}\) approaches and exceeds 1, the growth rate of the leached layer and the total alteration depth will both deviate from their t1/2 dependence, with the leaching rate decreasing and the total alteration rate increasing. Thus, the fact that the experimental leaching rate follows a t1/2 dependence does not necessarily mean that the transport is solely due to diffusion and there is no dissolution. The transport model developed here can be used to estimate the dissolution rate if the diffusion coefficient is known, as shown in Applications Part 3. However, it is better to measure the dissolution experimentally, when feasible.

By analyzing the experimentally observed concentration profiles for SLS surfaces corroded in neutral and acidic conditions with the convection-diffusion equation with proper boundary conditions, we find strong evidence that transport phenomena during corrosion are driven by the inward diffusion of hydrous species, rather than the outward diffusion of sodium ions. While corrosion in neutral condition results in the formation of a gel layer on top of the leached layer, corrosion in acidic conditions is accompanied by the dissolution of the leached layer. This difference can be explained if we realize that the primary hydrous species diffusing into the glass varies depending on the solution pH.

In pH 7, the concentration of protons ([H+]) and hydroxide ([OH-]) ions are very low, around 10-7 M. Thus, the main hydrous species that will interact with the glass network is water (H2O); thus, the diffusion coefficient measured at 90 °C would be \({{\mathcal{D}}}_{{H}_{2}O}=1.0\times {10}^{-16}{{cm}}^{2}/s\). Then, the following reaction could take place in the glass:

H2O(ingress) + ≡Si-O-Na+ → ≡Si-OH + Na++ OH-(generated)

The Na+ ion is then free to diffuse out, and the hydroxide ions generated inside the glass can undergo further reactions, dissociating the nearby glass network:

OH-(generated) + ≡Si-O-Si≡ → ≡Si-OH + -O-Si≡

This reaction will facilitate further ingress of water, leading to the formation of the observed gel layer. Note that this gel layer may delaminate from the glass surface if it grows too thick or if the solution is agitated.

In pH 1 where [H+] = 10-1 M and [OH-] = 10-13 M, the main hydrous species diffusing into the glass will be protons, such that the diffusion coefficient measured at 90 °C would be \({{\mathcal{D}}}_{{H}^{+}}=5.5\times {10}^{-17}{{cm}}^{2}/s\). It may be counter-intuitive for the diffusion coefficient of H+ to be less than the diffusion coefficient of water, but this could be explained by the difference in glass networks which the hydrous species must diffuse through—the silica-like remnant glass network for H+ from pH 1 solution vs. the porous gel layer for H2O from pH 7 solution. This will protonate the nonbridging oxygen in the glass network:

H+(ingress) + ≡Si-O-Na+ → ≡Si-OH + Na+

The sodium ion is then free to diffuse out of the glass. In acidic conditions, the ingress of these hydrous species does not manifest in the formation of a porous gel layer at the SLS surface18. But, this silica-rich network will still undergo dissolution at a rate of \(U=2.56\times {10}^{-12}{cm}/s\).

In pH 13 where [H+] = 10-13 M and [OH-] = 10-1 M, the main hydrous species diffusing into the glass is hydroxide ions, which will dissociate the glass network:

OH-(ingress) + ≡Si-O-Si≡ → ≡Si-OH + -O-Si≡

Previous work has shown this to lead to the dissolution of the glass at a rate of \(U=2.8\times {10}^{-8}{cm}/s\) at 90 °C59. At this high dissolution rate, \({Pe}\gg 1\) at very early treatment times, such that the diffusion coefficient could not be reliably determined.

In this work, the only situation which is solved numerically is the case where the moving boundary has a constant velocity, as it is physically relevant for aqueous corrosion of SLS in acidic conditions. However, it should be noted that the model can be adjusted to account for other moving boundary trajectories. For example, the numerical solution to the convection-diffusion equation presented here (Fig. 1c) may be applied to describe the transition from Stage 2 (extremely slow corrosion rate due to the presence of passivation layer) to Stage 3 (resumption of glass dissolution) in corrosion of ISG60. It has been discussed that the decreased dissolution rate seen in the transition from Stage 1 to Stage 2 corrosion could be a consequence of various processes which involve restructuring of the remnant layer and pore closing (leading to a decrease in \({\mathcal{D}}\))10. However, this restructured passivation layer may still dissolve at a constant rate, albeit significantly slower than in Stage 1. This dissolution rate might be too small to be measured within typical experimental observation times; but this does not necessarily mean that dissolution does not occur at all. If the dissolution occurs at a constant rate, then Eq. (23) dictates that the system will reach \({Pe}=1\) after a sufficiently long time. Alternatively, if the solution conditions changed rapidly, such that the dissolution rate increased significantly51,61, then the system may transition from a diffusion-controlled regime (\({Pe}\ll 1\)) to a dissolution-controlled regime (\({Pe}\ge 1\)). There might be an induction time before this transition becomes experimentally measurable. It is simply a matter of relative rates of diffusion and convection induced by the dissolution rate (\(d\eta /{dt}\)) at a given time or observation duration (\(t\)). More detailed analysis of this transition in ISG corrosion is beyond the scope of the current work and can be the focus of a future study.

We propose here two models for the incongruent corrosion of silicate glass using a moving boundary condition for the convection-diffusion transport equation. The first utilizes a similarity solution to provide an analytical model, which is physically meaningful when the moving boundary is caused by the interdiffusion of water and ions. The second model is solved numerically and allows for the motion of the moving boundary to be uncoupled from the diffusion process, such as when the outer surface of the leached layer dissolves at a constant rate. The two models are shown to explain the corrosion behavior of SLS in neutral water and highly acidic conditions, respectively. Additionally, it is demonstrated that both models can well describe the sigmoidal shape of the experimental concentration profiles with a constant diffusion coefficient, if previously neglected experimental artifacts are properly considered. With this correction, it is not necessary to assume that the diffusion coefficient will vary with the concentration of the diffusing species. The constant dissolution model is then used to show that the apparent decrease in sodium-leaching depth when SLS is treated in a solution pre-saturated with NaCl can be best explained by an increase in the dissolution rate of the leached layer, instead of a decrease in the leaching rate. This is proposed as evidence which supports the hypothesis that leaching is driven by the chemical potential of hydrogen containing species (inward diffusion of protons), not the chemical potential of sodium (outward diffusion of mobile ions). Finally, we introduce the Péclet number (\({Pe}\)) to compare the convective and diffusive components of the corrosion. In the case of gel-layer formation where the similarity solution is used, the \({Pe}\) remains constant with time. In the case of a constant dissolution rate, the \({Pe}\) increases with time. Combining all results together, the main species diffusing into the glass and subsequent reactions occurring in the glass can be understood comprehensively.

Methods

Sample preparation

Soda Lime Silica (SLS) glass samples were cut from planar sheets as supplied by AGC Inc. (Tokyo, Japan), with a composition shown in Table S2. The target dimensions for the glass samples were 2 cm × 2 cm × 0.7 mm. After fracturing, the samples were annealed for 2 hours at 520 °C to relieve any stress imposed on the glass network during scribing and fracturing, which would influence the corrosion behavior59,62. The samples were rigorously cleaned by repeated and alternating sonication in HPLC grade acetone (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis MO, USA) or ethanol (Decon Labs, King of Prussia PA, USA). After cleaning, the samples were sprayed with Type 1 DI water (LabChem Inc, Zelienople PA, USA) and blow-dried with nitrogen. During cleaning, special care was taken to avoid touching the faces of the glass samples, since even slight physical contact has previously been shown to enhance corrosion susceptibility59,63.

The acidic solutions were prepared by mixing nitric acid (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham MA, USA) with Type 1 DI water in pre-cleaned perfluoroalkoxy (PFA) jars (Savillex, Eden Prairie MN, USA). A pre-cleaned permeable PFA basket was also placed inside the PFA jar, to ensure full exposure of the samples to the acidic solution. The pH was set to 1 using the mass of the constituent solutions and was validated using a pH testing strip after mixing.

For the samples which were pre-saturated with NaCl (VWR, West Chester PA, USA), the pH 1 solution was prepared as described above, and then pre-heated to 95 °C overnight. Then, enough NaCl was added to the solution such that, if the NaCl were to completely dissolve, the solution would reach 7.8 M. Since the saturation concentration of NaCl is approximately 6.4 M at these conditions, there was always excess NaCl at the bottom of the jar. In this way, it was ensured the solution retained the highest possible concentration of dissolved sodium ions. This solution was placed in an oven held at 95 °C, and was set to mix by a magnetic stir bar overnight.

Prior to adding the glass samples, both solutions were given ample time to reach 90 °C. The amount of solution in each container was adjusted to ensure the glass surface area to solution volume ratio was between 0.25 and 0.30 cm-1. The glass was added to the solutions, ensuring they were placed on top of the sample basket to ensure complete immersion of the samples in the solution, while not touching the undissolved NaCl at the bottom of the jar. The PFA jar was sealed tight, and then placed back into a Fisherbrand Isotemp oven, which was held at a constant 90 °C. After adding the jar to the oven, the mass of the sealed jar was measured regularly to ensure no significant mass loss due to evaporation.

After treatment was completed for the designated time, the jar was removed from the oven. The glass samples were then carefully removed for the acidic solution, and were thoroughly rinsed with Type 1 DI water, to remove any remaining solution. The pH of the post-treatment solution was again tested with pH testing strip, with no pH change detected for any of the solutions. The samples were thoroughly dried using nitrogen gas and wrapped in ultra-clean aluminum foil until needed for analysis. The solution, if it was to be used for ICP, was retained in the tightly sealed PFA jar and stored at room temperature.

X-ray Photoelectron Spectroscopy

X-ray photoelectron spectroscopy (XPS) was used to measure the composition of the glass after treatment, using a similar process as described previously5. Analysis was conducted using a PHI VersaProbe III with a monochromatic Al-Kα X-ray source and a low energy charge neutralizer at the Penn State University Materials Characterization Lab. Accurate relative sensitivity factors were determined by analyzing an in-situ vacuum fractured sample of SLS, and then using the elemental composition provided by AGC Inc. to normalize the peaks, found in SI 6. Elemental quantification was performed over narrow binding energy regions to measure the O 1 s, Na KLL, Ca 2p, Mg KLL, C 1 s, Si 2p, and Al 2p peaks, averaging 3 scans with a pass energy of 224 eV, with the backgrounds set using an iterated Shirely background. These peaks were chosen due to their similar inelastic mean free path64. Surface charging was adjusted by calibrating the adventitious carbon contamination to 284.6 eV. Depth profiling was performed using an Ar+ beam, where the profiling rate was calibrated separately using a silicon wafer with known SiO2 thickness. The analysis beam was set to a 200 μm diameter circle, within the 2 mm by 2 mm profiling crater, to mitigate edge effects. All data processing was conducted in CasaXPS65.

Inductively coupled plasma spectrometry

Elemental composition of the post-corrosion solution was analyzed using both inductively coupled plasma mass spectrometry (ICP-MS) and inductively coupled plasma atomic emission spectrometry (ICP-AES). Analysis was performed at the Laboratory for Isotopes and Metals in the Environment at Penn State University, using a Thermo Fisher Scientific iCAPTM RQ ICP-MS and a Thermo Fisher Scientific iCAPTM 7400 ICP-OES. The method of analysis was chosen to ensure the expected concentration of the element of interest in the leaching solution would fall within the calibration range of the instrument. This led to sodium, calcium, and silicon data being collected by ICP-AES, while ICP-MS was used to collect concentration data of magnesium. This composition data was then used with the following equation:

to calculate the equivalent dissolution thickness \(\left({{Th}}_{c}\right)\)66,67. This equation uses the solution concentration of element \(i\) \(\left({C}_{i}\right)\), the volume of the solution \(\left(V\right)\), the mass fraction of element \(i\) in the pristine glass \(\left({f}_{i}\right)\), the surface area of the glass sample \(\left(S\right)\), and the density of the glass sample \(\left(\rho \right)\) to estimate the thickness of glass that must have dissolved to release the specific amount of element \(i\) into solution. It should be noted that this calculation inherently assumes that the entire equivalent dissolution thickness has been congruently corroded.

Surface sensitive spectroscopy

Vibrational spectrum of the corroded and pristine glass were collected using the advanced, surface sensitive characterization technique photothermal atomic force microscopy coupled with infrared spectroscopy (AFM-IR)54. The analysis was conducted on a Dimension IconIR system from Bruker, using a gold-coated PR-UM-CnIR-B-10 tips (Bruker, Billerica MA, USA) (with a spring constant of 0.2 N/m and a resonant frequency of 13 kHz), with the instrument operated in surface sensitive mode. Surface sensitive mode utilizes a heterodyne detection mechanism to achieve enhanced surface sensitivity. For all measurements, the piezo modulation frequency was tuned to 2.00 MHz, the laser pulse rate was 1.54 MHz, and the detection frequency was 460 kHz. While the exact probe depth depends on the material being measured and the frequencies used, based on previous work on silica glass it is assumed that the probe depth on SLS is ~150 nm54,59,68.

Numerical simulations

Numerical simulations of the convection-diffusion equation were conducted in a custom Python code using the method of lines. The full code is made available in SI 7. The method of lines proceeds by first discretizing the spatial derivatives only and leaving the time variable continuous. This leads to a system of ordinary differential equations which are then integrated using a time-marching scheme for initial value problems.

The overall algorithm is as follows. First, a uniform spatial grid is used to discretize Eq. (16) with respect to the spatial variable \(s\) using second-order finite differences of the form:

where \(\varDelta s\) is the spacing of the uniform spatial grid47. The concentrations at all spatial nodes are initialized using the initial condition for Eq. (16), and the above approximations are used in Eq. (16) to approximate \(\frac{\partial \bar{c}}{\partial t}\) at each spatial node. An explicit Euler scheme is then used to march the solution in time according to:

where \(\varDelta t\) is the time step. Knowing the solution at all spatial nodes at time \({t}_{n}\), this step can be repeated to calculate the concentrations at time \({t}_{n+1}\)47. Thus, by starting with the initial condition provided by the original problem formulation, the concentration profile at any time \(t=j\times \varDelta t\) can be computed by repeating these steps until \(n=j\). The spacing \(\varDelta s\) and time step \(\varDelta t\) were optimized to ensure they had no significant impact on the results, while considering computation speed. With the exception of the simulations for Fig. 10h, which required a grid spacing of \(\varDelta s=0.25{nm}\), a grid spacing of \(\varDelta s=0.5{nm}\) was used in all cases. A time step of \(\varDelta t=1\sec\) was used in all simulations.

Gaussian convolution

The process to convolute the theoretically determined concentration profiles to model the Gaussian profile inherent to experimental collection was done using a custom Mathematica code, which is available in SI 8. A visual diagram of the general procedure is found in Fig. 12. First, concentration data is input to the program, either in an analytical or discrete form. If in discrete form, then tabulated data may be uploaded and interpolated. Either way, the result is some function \(T(x,t)\), which represents the theoretical concentration profile at some time \(\left(t\right)\), as a function of depth \(\left(x\right)\). Then, a Gaussian curve is defined as per the following equation: