Abstract

Full understanding of the anisotropic interfacial reactions between albite (NaAlSi3O8) and sulfate-rich solutions is crucial for predicting the stability of minerals in both natural and engineered systems. However, the regulatory role of mineral surface orientation on reaction pathways at the atomic scale remains unclear. This study employs reactive molecular dynamics (ReaxFF MD) simulations to systematically investigate the kinetic behaviors of the interfacial reactions between albite (100), (010), and (001) surfaces and sulfate solution. The results reveal significant anisotropic effects among the different surfaces: the (001) surface exhibits the highest reactivity due to its high surface energy, which leads to the surface structural disordering as well as the leaching of Na+ mediated by ion exchange and sulfate coordination. In contrast, the (100) surface maintains structural stability through a dense hydrogen bond network and Na+ shielding effects, while the (010) surface structure facilitates the formation of silanols, inhibiting ion migration.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Understanding the interfacial reactions between silicate minerals and fluids is crucial for revealing material transport processes in natural systems. These reactions play vital roles in various environments, from near-surface soil weathering profiles to deep geological reservoirs, and even in engineered systems such as carbon sequestration or nuclear waste repositories1. As one of the most abundant silicate minerals in the Earth’s crust2,3, feldspar dissolution-precipitation dynamics significantly regulate the release of alkali/alkaline earth metals and silicon into natural waters, as well as the formation of secondary clay minerals4. Albite (NaAlSi3O8), the sodium end-member of the plagioclase solid solution series, has been extensively studied as a model system for silicate weathering processes5,6. However, much of the existing understanding of mineral dissolution stems from experiments using polycrystalline or powdered samples. While invaluable, these approaches often mask or average out the critical influence of crystallographic anisotropy on interfacial reaction kinetics, particularly under the near-equilibrium conditions prevalent in natural and engineered environments, where the reactivity of specific crystal faces may dominate the overall process. For instance, the interactions between albite and sulfate-rich fluids (e.g., SO42− ions in acid mine drainage or oilfield brines) could lead to surface passivation or secondary mineral formation, the processes of which may be regulated by atomic arrangements and defect densities across different crystal faces. Thus, elucidating how the crystallographic anisotropy of feldspar minerals governs atomic-scale structural evolution during surface interactions with sulfate solutions (such as sulfate-mediated dissolution, ion exchange, and secondary mineral formation) can provide critical support for predicting long-term mineral stability in CO₂ sequestration reservoirs and assessing the lifespan of nuclear waste containment barriers.

Feldspar dissolution has been widely investigated during the last few decades, the rates of which are highly dependent on chemical affinity (ΔGₐ), pH, temperature, and the presence of inhibitory species7,8,9,10,11. Nevertheless, there still exist significant knowledge gaps regarding the effects of surface-specific factors on the regulation of dissolution and precipitation pathways, including crystal face orientation, step density, and defect distribution. It is crucial to recognize that understanding the anisotropy in crystalline material reactivity constitutes an essential theoretical foundation for establishing robust mineral dissolution kinetic models. Pollet-Villard et al.12 demonstrate that due to crystallographic anisotropy, the effect of chemical affinity on feldspar dissolution differs markedly across individual crystal surfaces, governing the spontaneous nucleation of etch pits and dissolution mechanism. This finding is consistent with the general understanding, as extensively documented by numerous prior studies13,14,15,16,17, that fundamental mechanisms and derived rate laws are difficult to directly extrapolate from traditional mineral powder dissolution experiments. The reason lies in the dilemmas faced by conventional powder experimental methods in polycrystalline system studies: On one hand, the inherent polycrystalline nature of materials creates difficulties in decoupling the synergistic effects of different crystallographic orientations. On the other hand, although characterization techniques such as X-ray photoelectron spectroscopy (XPS)18, uclear magnetic reso-nance spectroscopy (NMR)19,20, Fourier-transform infrared (FTIR) spectroscopy21,22, and secondary ion mass spectrometry (SIMS)23 have played a key role in deciphering macroscopic behaviors such as mineral dissolution rates and etch pit morphologies, they are all constrained by insufficient spatial resolution and dynamic tracking capabilities. This limitation makes it challenging to precisely reveal detailed information about interfacial behaviors or reaction mechanisms induced by aqueous solutions and dissolved ions in polycrystalline mineral systems4. While techniques like atomic force microscopy (AFM)24,25 and vertical scanning interferometry (VSI)12,26,27 provide the data for spatially resolved rate maps (nanoscale) that quantify and illustrate the substantial heterogeneity in surface reactivity, they still face limitations in characterizing more refined atomic-scale kinetic processes. These include the dynamic evolution of surface coordination environments, the configurations of ion adsorption, chemical bond breaking/formation events, and hydrogen bonding network dynamics occurring on picosecond to nanosecond timescales.

Reactive molecular dynamics (ReaxFF MD) simulations, leveraging force fields parameterized from first-principles calculations, offer unparalleled capabilities to probe atomistic mechanisms at well-defined mineral-fluid interfaces28,29,30. This approach uniquely enables the visualization of critical dynamic reaction processes at the molecular scale, overcoming limitations inherent to current experimental techniques31,32. Within the ReaxFF MD framework, in-depth analysis of how mineral crystal anisotropy and complex fluid components regulate interfacial kinetics advances the mechanistic understanding of molecular-level processes such as mineral dissolution and precipitation. Recent applications of ReaxFF MD have illuminated dissolution mechanisms in amorphous aluminosilicate glasses33,34,35, providing direct molecular-scale insights that enhance experimental understanding of mineral-water interface dynamics4. However, two critical knowledge gaps persist at the nanoscale: (1) The regulatory role of crystallographic anisotropy on reaction pathways. Compared to amorphous glasses, albite single crystals exhibit well-defined crystalline structures where distinct crystal faces (e.g., (100), (010), (001)) may exhibit divergent ion exchange rates and alteration activation energies due to varying surface coordination states and dangling bond densities. (2) The coupling effects of complex fluid components (Ca2+, SO42−) on interfacial kinetics. While Ca2+ acts as a charge-balancing cation, SO42− ions participate through competing interfacial processes. These include electrostatic screening that inhibits H+ adsorption36 and surface complexation with Al3+ that modifies hydrolysis energy barriers37. Although recent research has made significant progress in elucidating reaction mechanisms at the silicate glass-water interface38,39, the influence of sulfate ions in sulfate-rich solutions on the dissolution behavior of different mineral crystal faces is more complex than that of pure water dissolution. This complexity arises from the ionic characteristics of sulfate (high charge density, specific spatial configuration, and competitive adsorption capacity). Given the widespread presence of sulfate-rich fluids in natural feldspar weathering environments and their common occurrence in engineering systems where long-term mineral stability is crucial, revealing the hydrolysis mechanisms of different mineral crystal faces under sulfate-rich fluids holds significant importance. It enables the prediction of natural feldspar weathering pathways or ensures the long-term stability of engineered barrier materials.

In this study, ReaxFF MD simulations (2.5 ns) are employed to systematically investigate the interfacial reactivity of albite’s different surfaces ((100), (010), (001)) in contact with CaSO4 solutions. The anisotropic dissolution mechanisms and sulfate-mediated surface transformations are unraveled through analysis of reaction species distribution, hydrogen bonding networks, atomic density profiles, charge states, and mean square displacements. These findings provide a valuable perspective for refining the understanding of fluid–solid reactions at the molecular scale. This study advances the fundamental understanding of albite–solution interactions while providing predictive insights for optimizing mineral stability in subsurface engineering applications.

Results and discussion

Surface energy and surface structure analysis

The structural configurations and calculated surface energies for the (100), (010), and (001) crystallographic surfaces of albite are summarized in Table 1. The surface energies follow the order: (001) > (010) > (100). This disparity predominantly originates from distinct atomic configurations and coordination environments exposed during cleavage processes. The (100) surface exhibits the lowest surface energy, attributable to its continuous [AlSi3O8]n framework network (as shown in Fig. 2a(iv)) formed by tetrahedrally coordinated Al3+/Si4+ centers interconnected through bridging oxygen atoms. All oxygen species maintain their bridging configuration in this surface architecture, effectively preventing the formation of undercoordinated metal centers. Furthermore, interstitial Na⁺ remains encapsulated within oxygen-constructed cavities, achieving charge compensation through long-range electrostatic interactions while maintaining low defect density. In contrast, the moderately higher surface energy of the (010) surface correlates with cleavage-induced disruption of Al-O octahedral chains. This structural perturbation induces a coordination number increase (from four to five coordination, as shown in Fig. 2b(i)(ii)) in partial Al3+ centers within tetrahedral frameworks, creating localized charge asymmetry that necessitates additional energy expenditure for electrostatic stabilization. The (001) surface demonstrates the highest surface energy due to its cleavage mechanism that directly disrupts the covalent Si–O–Al network, exposing high densities of terminal non-bridging oxygen species and unsaturated Si/Al centers. Moreover, Na⁺ cations within framework channels become fully exposed at this interface, where their unscreened positive charges generate substantial electrostatic repulsion with adjacent electronegative terminal oxygen atoms. The synergistic effects of these atomic-scale structural defects and charge imbalances necessitate complex electronic redistribution mechanisms for surface stabilization, thereby substantially elevating surface energy. The observed positive correlation between surface reactivity towards CaSO4 solutions and surface energy across different albite surfaces primarily derives from variations in exposed coordination states and charge distribution patterns. Detailed mechanistic discussions will be presented in subsequent sections.

Reactivity of the albite/sulfate solution interfaces

Figure 1 illustrates the dynamic interfacial structural evolution of albite (100), (010), and (001) crystal surfaces interacting with CaSO4 solution at the initial reaction stage (0 ns) and after 2.5 ns. The corresponding top-view surface morphology and magnified details of characteristic structures at 2.5 ns are shown in Fig. 2. Comparative analysis reveals that all surfaces undergo significant surface reconstruction through interactions with the solution, while exhibiting distinct reaction pathways and kinetic characteristics. On the (100) surface, the exposed aluminum atoms (initially undercoordinated) and the oxygen atoms of the SiO4 tetrahedra serve as the primary reactive sites. On the one hand, water molecules directly coordinate with the Al atoms through coordination interaction. On the other hand, the water molecules dissociate into OH− and H+ species, and the OH− groups combine with Al atoms to achieve their hydroxylation, while the oxygen atoms on the surface silicon-oxygen tetrahedra act as proton acceptors for the dissociated H+. This process drives the coordination evolution of Al from initial AlⅣ to AlⅤ/AlⅥ (The superscript numbers represent the coordination number). This is schematically illustrated by the (i) (ii) structural configuration in Fig. 2a. Notably, the [AlSi3O8]n framework network (Fig. 2a(iv)) contains substantial porosity, enabling limited water penetration into subsurface regions. While SO42− migrate to bond with surface Al atoms, Ca2+ adsorption is inhibited by Na+ shielding effects.

The (010) surface features reactive tri-coordinated Si atoms as active centers. Dissociated OH− preferentially binds with Si to form dense silanol groups (Fig. 2b(iii)), surpassing other surfaces in hydroxyl density. The Si–O–Al bridging oxygen acts as a proton acceptor, forming Si–OH–Al configurations. Interestingly, the absence of SO42− adsorption is observed on this surface, which is attributed to the absence of directly exposed Al atoms at the interface, leading to a lack of binding sites for SO42−. The adsorption of Ca2+ is associated with the hydroxylation of surface Si atoms, where the hydroxylated surface electrostatically attracts Ca2+. In contrast, the (001) surface demonstrates the highest reactivity with pronounced structural disordering compared to other surfaces. Enhanced adsorption behaviors of SO42− with Ca2+ were observed on the (001) surface. Notably, Na+ leaching behavior was uniquely identified on this facet, a phenomenon absent in both (100) and (010) surfaces. This is because, on one hand, the high surface energy promotes the hydroxylation of surface Si and Al, weakening the bonding of Na+ at the central sites, and on the other hand, the typical ion exchange mechanism facilitates Na+ release40. Additionally, the exposed Al atoms demonstrate a metastable dissolution tendency. Surface Al atoms undergo a coordination transformation from three-coordinate to AlIV/AlV/AlVI configurations (as shown in Fig. 2c(i)–(iii)), accompanied by partial hydration dissolution, evidenced by significant deviations of the Al coordination geometry from the surface reference plane. Nevertheless, the dissolved Al species maintain strong bonding with surface terminal oxygen through inner-sphere complexation, indicating that complete dissolution of Al remains kinetically constrained within the limited simulation timeframe (2.5 ns). This phenomenon suggests that the dissolution process of feldspar minerals likely follows a stepwise mechanism of local activation-progressive detachment, where initial surface modifications precede gradual structural disintegration. This concept is consistent with the stepwise, site-specific dissolution mechanisms proposed based on quantum chemical calculations41 and is supported by experimental observations of interfacial dissolution–reprecipitation processes in silicates and aluminosilicates at the nanoscale42.

H-bond density and strength analysis

Hydrogen bonding, as a prototypical example of intermolecular weak interactions in mineral–solution interfacial reactions, demonstrates density and strength parameters that directly characterize the interaction characteristics between water molecules and mineral surfaces43,44,45. Figures 3 and 4 present the calculated 1D and 2D hydrogen bond density and intensity profiles for albite surfaces interacting with CaSO4 solution at 2.5 ns. To define a hydrogen bond, the distance cutoff is set as 3.5 Å, and the angle is set as 30.0°. The (100) system shown in Fig. 3a demonstrates much higher peak values at the interface, and the number density is about 0.062/Å3 compared with 0.054/Å3 for the (010) system and 0.043/Å3 for the (110) system. This discrepancy can be attributed to the heterogeneous behavior of different surfaces in response to the solution (as illustrated in snapshots in Fig. 4). The (100) surface atomic arrangement features high-density bridging oxygens (Si–O–Al, Si–O–Si) and active sites consisting of terminal non-bridging oxygens in silicon–oxygen tetrahedra, along with a well-ordered structure and relatively flat reactive surfaces that facilitate strong hydrogen bond network formation with water molecules. In contrast, the (010) surface aligns parallel to silicon–oxygen tetrahedral chains, adopting a dominant [SiO3] configuration with silicon atoms as the primary exposed species. The sparse exposure of active oxygen sites reduces hydrogen bond strength and density compared to the (100) surface. The (001) surface exposes two terminal non-bridging oxygens and Si–O–Al bridging oxygens from tetrahedra, but its irregular reactive surface topology results in short-range, low-density hydrogen bond networks at the interface.

Furthermore, two-dimensional color contour maps reveal spatial distribution details of hydrogen bond density across XY and YZ surfaces for each crystal system (left and middle columns of Fig. 4), illustrating how hydrogen bond density propagates along albite’s edge geometry with different crystallographic orientations. The (100) surface shows significant interfacial hydrogen bond density variations with distinct localized high-density regions, demonstrating pronounced interfacial aggregation characteristics. Comparatively, the (010) surface exhibits more uniform density distribution while retaining observable local hydrogen bond clustering at the interface, suggesting that the (010) surface possesses stronger hydrogen bond-forming capabilities in certain localized regions. In contrast, the (001) surface displays relatively homogeneous hydrogen bond distribution from interface to bulk solution without significant localized aggregation features observed in the (010) and (100) systems.

Atomic density distribution

The atomic density distribution maps provide spatial characterization of various atom types within minerals and at their interfaces with solutions. By analyzing changes in atomic density profiles during dissolution, these maps visually reveal the evolution of mineral surface structures and reaction dynamics. Figure 5 presents the atomic density distribution characteristics of albite (100), (010), and (001) surfaces after interaction with CaSO4 solution. The density profiles reveal significant atomic density fluctuations in the mineral/solution interfacial region of the (100) surface, where the steep interfacial feature indicates distinct phase separation between mineral and solution phases, associated with the lower surface energy of this crystallographic surface. Notably, both H and Ow atoms exhibit higher density peaks at the (100) surface compared to the (010) and (001) surfaces, with the (001) surface showing the lowest peak values for both H and Ow atomic densities. These observations align with the hydrogen bond network analysis presented in Section “H-bond density and strength analysis”. Higher surface hydrogen bond density facilitates tighter water molecule adsorption, forming a stable hydration layer that not only prevents undesirable surface reactions but also reduces dissolution and corrosion potentials46,47. A distinct Os density peak emerges in the mineral region of the (100) and (001) surfaces, indicating sulfate ion adsorption at the mineral/solution interface. Characteristic Ow and H atom density peaks observed in the regions of all three surfaces respond to the gradient diffusion behavior of water molecules along mineral surfaces. Particularly, the (100) and (010) surfaces maintain well-ordered density distributions of O, Al, and Si atoms post-reaction, demonstrating remarkable structural stability during interfacial processes. In contrast, the (001) surface displays disordered atomic density fluctuations at the interface, attributable to its higher surface energy that enhances susceptibility to solution-induced structural reorganization. Furthermore, a distinct sodium density peak emerged in the solution phase of the (001) system, which indicates the occurrence of Na+ dissolution behavior on the (001) surface.

Radial distribution function

To further analyze the characteristic coordination of surface atoms with water and ions during reactions between different albite surfaces and CaSO₄ solution. The radial distribution function (RDF) is defined as the ratio of the average number of atoms per unit volume at a distance r from a reference atom to the overall average atomic number density of the system. The calculation formula is as follows:

where \({\rho }_{0}=\frac{N}{V}\) represents the average atomic number density of the system (where N is the total number of atoms and V is the volume); dN(r) denotes the average number of other atoms within a spherical shell at a distance r+dr from the reference atom; \(4{\rm{\pi }}{r}^{2}{dr}\) is the volume of the spherical shell.

Figure 6a presents the RDF of Si–Ow in albite (100), (010), and (001) surface systems. Distinct characteristic peaks emerge at 1.65 Å for (010) and (001) surfaces, with this bond length closely matching the typical coordination distance of Si–Ow during silica tetrahedron hydrolysis, indicating the formation of stable coordination structures between surface silicon atoms and water molecules. The (010) surface exhibits a prominent peak, attributable to under-coordinated Si atoms (tri-coordinated state) with strong electronegativity on this surface, which readily coordinate with water molecules to form Si–OwH surface hydroxyl groups. In contrast, the weaker peak intensity observed for the (001) surface suggests reduced interaction strength at this coordination distance. No discernible peaks are detected for the (100) surface within this bond length range, directly correlated with the coordination saturation of four-coordinated Si atoms on this surface.

The Al–Ow RDF analysis in Fig. 6b reveals first coordination peaks at 1.83 Å for (100) and (001) surfaces, consistent with results reported by Jabraoui et al.48. The peak intensity follows the order: (001) > (100), while the (010) surface shows no significant peaks at short distances (<3 Å). This discrepancy originates from structural characteristics: Al atoms on the (010) surface are predominantly embedded within the silica tetrahedral framework, forming stable Al–O tetrahedral configurations with low surface Al/O ratios that effectively suppress Al–Ow interactions. The layered structure of the (001) surface exposes higher proportions of under-coordinated Al atoms, which form stable Al–Ow coordination through strong interactions with oxygen atoms in water molecules. Notably, the lower surface energy of the (100) surface provides limited active sites through defects or localized Al exposure, explaining its reduced coordination peak intensity compared to (001). The Na–Ow hydration characteristics (Fig. 6c) demonstrate significant crystallographic orientation dependence, with primary peaks at 2.41 Å showing intensity sequence (100) > (010) > (001), consistent with experimental observations49,50. This trend correlates with structural differences in mineral-solution interfacial hydrogen bond networks, where the unique Na⁺ spatial distribution pattern on the (100) surface likely enhances hydration.

For calcium coordination behavior (Fig. 6d), the main Ca–Ow RDF peak at 2.5 Å aligns closely with experimental and MD simulation results (average 2.47 Å) reported by Jalilehvand et al.51, validating computational model reliability. Detailed analysis (Fig. 6e) shows both (001) and (010) surfaces exhibit Ca–O coordination peaks at 2.41 Å, but with broader peak width for (001). This difference arises from distinct oxygen species exposure: terminal oxygen atoms with higher negative charge density on the (001) surface readily form coordination bonds with Ca2+, while bridge oxygen and Al3+-coordinated oxygen on the (010) surface exhibit lower coordination activity. The denser atomic arrangement on the (010) surface restricts Ca2+ adsorption sites, reflected in a narrower peak width. The (100) surface shows no detectable peaks due to Na+ electrostatic shielding effects.

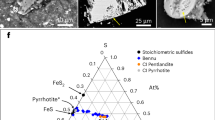

In terms of SO42− adsorption behavior (Fig. 6f), the surface of (001) shows a prominent Al–Os coordination peak at 1.89 Å, which is very close to the X-ray test result of 1.879 Å52, indicating stable surface complex formation. In contrast, the Al-Os coordination bond length on the (100) surface measures 2.01 Å, attributed to the electrostatic shielding effect induced by Na+ on the (100) surface, which weakens the adsorption interaction between SO42− and Al3+. Notably, no Al–Os peaks appear on the (010) surface, where dense silica tetrahedral networks effectively isolate Al3+ from the solution phase.

Atomic charge state

The change in the charge state of atoms or ions reflects the electron transfer process of reactions occurring at the mineral–solution interface. Monitoring the charge state helps determine the hydration or hydroxylation degree of surface atoms, identify the formation of hydrated products in reactions, and understand the overall reaction pathways involved in mineral dissolution. Figure 7a–c present the atomic distribution along the z-axis and the surface charge distribution of albite (100), (010), and (001) surface systems at 2.5 ns. To elucidate the charge transfer mechanism during interfacial reactions, a comparative analysis of the charge values of representative metal cations under distinct structures on each surface was conducted. The z-axis charge distribution reveals non-identical surface adsorption groups and charge patterns across different crystallographic surfaces. This study statistically analyzed the trend of charge changes in Si and Al atoms within the solid region (24–27 Å) near the solution reaction interface on different surfaces.

The left panel presents the atomic charge distribution along the z-axis at 2.5 ns for the a 100, b 010, and c 001 surfaces (top to bottom). The central panel displays representative snapshots of surface charge configurations at 2.5 ns, with atoms color-coded by Mulliken charges. The right panel comparatively analyzes charge variations of Al and Si atoms under distinct characteristic states from different surfaces.

In the interface region of the (100) surface, the average positive charge of Si atoms increased by 1.2% (Δq = +0.017e) compared to the overall system, while Al atoms increased by 7.7% (Δq = +0.08e). Conversely, the (010) surface showed a reverse trend with Si atom charges decreasing by 7.97% (Δq = −0.1e) and Al atoms decreasing by 5.77% (Δq = −0.075e). The (001) surface exhibited differential changes, with Si atom positive charges decreasing by 5.71% (Δq = −0.071e) and Al atoms increasing by 3.38% (Δq = +0.04e). These charge distribution differences are closely related to the post-reaction interface structure. The (010) surface’s charge reduction originates from hydroxylation of exposed SiO3 groups (SiO3 → SiO3–OH, Fig. 2b(iii)), where Si accepts hydroxyl electrons. Meanwhile, the protonation of SiO4 groups on the (001) surface (SiO4 → SiO4H) weakens the electron attraction of Si (Fig. 2c(vi)), reducing its positive charge. This is further confirmed by comparing the charge values of Si1/Si2 structures in Fig. 7b, c. Notably, the decrease in the charge of Al atoms on the (010) surface is also related to this electron transfer mechanism. However, the 100 surface, due to its low surface reactivity and dense hydrogen bond network that inhibits protonation reactions, has only a minimal portion of Si–O tetrahedra with protonated O, resulting in minimal overall charge fluctuations at the interface. Additionally, the number of neighboring oxygen atoms (O atoms) to Si atoms is positively correlated with their positive charge (comparison of Si1/Si2 in Fig. 7a), a pattern consistent with the results reported in the literature53.

Unlike the charge changes dominated by the coordination environment of Si atoms, the charge state of Al atoms is primarily regulated by coordinating molecules. It can be observed that the charge of Al atoms increases with the number of neighboring molecules (i.e., coordination with Ow, Os, O), as illustrated in the right panel of Fig. 7. In Fig. 7a, b, Al1 → Al2, and in Fig. 7c, Al1 → Al3, all exhibit an increase in positive charge for centrally coordinated Al atoms. When coordinated with the Ow of water molecules or the Os atoms of surface sulfate groups, Al atoms lose electrons, leading to an increase in positive charge (Δq > 0), while the coordinating Ow/Os gain additional electrons (Δq < 0). This charge transfer mechanism indicates that the coordination of interfacial water molecules with surface Al sites plays a crucial role in charge redistribution.

Dynamic properties

In the study of reaction kinetics at mineral–solution interfaces, the mean square displacement (MSD) is a crucial dynamic parameter that characterizes atomic migration behavior, effectively revealing the diffusion characteristics and interaction mechanisms of ions during interfacial reaction. The expression for the calculation of MSD is as follows:

where N is the number of particles and ri (t) is the position of the ith particle at time t. ri (0) is the initial moment position. Figure 8a, b presents the evolution of MSD and its vertical component (Z-MSD) for surface Na+ at different crystal surfaces of the albite–CaSO4 interface system. Computational data reveal that the (001) surface exhibits significantly higher MSD values compared to (100) and (010) surfaces, with its kinetic curve demonstrating steep initial ascent and intense fluctuations throughout the temporal domain, indicating superior diffusion activity of Na+ on this surface. This dynamic characteristic likely originates from relatively weak lattice confinement effects on the (001) surface, enabling enhanced susceptibility of surface sodium ions to thermodynamic perturbations from the solution environment. In contrast, the (100) surface maintains relatively stable MSD evolution, suggesting better kinetic stability in its diffusion process, while the persistently low MSD values of the (010) surface reflect strong constraints imposed by three-dimensional chemical bonding networks. Z-MSD analysis (Fig. 8b) reveals significant coupling between vertical diffusion behavior and overall dynamics for the (001) surface. The MSD-Z curve displays two rapid ascending phases (0–71 ps and 157–221 ps), corresponding to stepwise dissolution processes of Na+. Subsequent stages enter a slow-growth regime, though persistent fluctuations may correlate with dynamic reconstruction of layered structures or localized defect formation mechanisms. Comparative analysis shows the (100) surface achieves kinetic equilibrium after initial rapid response, while the near-zero MSD-Z values of (010) surface directly relate to steric hindrance effects from its interlayer close-packed structure. Combined with density distribution analysis from Fig. 5 (showing absence of sodium characteristic peaks in solution layer), this confirms sodium dissolution has not occurred on (100) and (010) surfaces. Comprehensive analysis demonstrates significant anisotropic diffusion characteristics among albite crystal surfaces: The (001) surface exhibits superior diffusion capacity due to layered structure and weak vertical confinement, particularly showing enhanced interfacial reactivity through high Z-direction activity; The (100) surface maintains limited 3D diffusion capacity with suppressed vertical motion; The (010) surface effectively restricts ionic migration through strong chemical bonding interactions.

Figure 8c, d reveals the anisotropic characteristics and dynamic evolution mechanisms of water molecule diffusion at the interface between different albite surface systems and calcium sulfate solution. Figure 8c demonstrates that the Ow–MSD curves of three surface systems initially exhibit rapid ascending trends, corresponding to the dynamic reconstruction processes of surface ion exchange and the initial interfacial hydration layer. During subsequent evolution stages, the MSD curves of the (100) and (010) surface systems gradually stabilize, indicating the achievement of dynamic equilibrium in their interfacial reactions. Notably, the Ow-MSD values of the (001) surface system present two distinct growth inflection points: rapid increase during 0–71 ps, slow growth in 71–485 ps, followed by another rapid increase in 485–575 ps before reaching system stabilization. This phenomenon suggests that after the initial rapid surface-solution interaction, subsequent dynamic reconstruction of metastable structures or localized concentration gradient effects induced by continuous leaching of surface cations (e.g., Na+) may provide additional kinetic driving forces for water molecule diffusion.

Further analysis of z-axis directional MSD reveals more pronounced differences in the (001) system compared to (100) and (010) systems. The mean squared displacement of interfacial water molecules along the Z-direction and the simulation time required to reach equilibrium in the (001) system significantly exceed those of other surfaces, further confirming its superior interfacial reactivity and reaction extent. Additionally, the (010) surface system maintains the minimum mean squared displacement of interfacial water molecules throughout the simulation, demonstrating exceptional interfacial stability compared to other surfaces.

Behavioral analysis of Na atomic leaching

This section investigates the Na+ leaching behavior and underlying mechanisms on the (001) surface. Figure 9a–d illustrates snapshots of the dissolution characteristics of Na+ at different surface sites of the (001) surface. The migration trajectories of Na⁺ from various dissolution sites are depicted by black trace lines in Fig. 10. Based on kinetic trajectory analysis, two dominant mechanisms are identified: (1) leaching induced by SO42− (Fig. 9a–c), and (2) ion-exchange mechanisms (Fig. 9d).

Figure 9a–c respectively displays the Na+ leaching behavior dominated by SO42− at three different sites. During initial hydration, the three Na+ remain in equilibrium positions constrained by lattice energy barriers, exhibiting vibrational motion within confined regions (as shown by trajectories in Fig. 10a–c). When SO42− diffuses from solution and approaches the vibrating Na+ ions, they facilitate the detachment of Na+ from the lattice surface through electrostatic interactions and coordination effects. Notably, while the Na+ in Fig. 9a, b exhibit rapid dissolution in early reaction stages, the Na⁺ in Fig. 9c undergoes approximately 350 ps of localized motion before achieving final desorption through cooperative interaction with adjacent SO42−. This reveals that the Na+ leaching process is not only constrained by the local environment but also exhibits dynamic randomness over the reaction time. Remarkably, SO42− exhibits catalyst-like behavior through reversible adsorption-desorption cycles that continuously promote Na+ separation. In contrast, Fig. 9d demonstrates an ion-exchange behavior between Na+ and H+ at the (001) surface. This exchange process, widely reported in the literature40,54,55,56, can occur either within a single SiO4 tetrahedron or between oxygen atoms of adjacent tetrahedra. As shown in Fig. 9d, a proton from the aqueous solution bonded with an oxygen atom in the SiO4 tetrahedron at 2.7 ps, forming a silanol group (Si–OH). Concurrently, the Na+ initiated dissociation from the reaction zone and diffused into the solution phase, achieving full desorption by 27 ps. The trajectory visualization in Fig. 10d corroborates this dynamic process. Charge compensation by protons from the aqueous solution was observed in both mechanisms to neutralize residual negative charges after Na+ dissolution. Additionally, surface reconstruction of the atomic structure near the leaching Na+ is observed, where the bridging oxygen bonds connecting Si–O–Al break and reform into Si–O–Si bonds. This surface chemical bond reorganization may result from the dissolution effect induced by the hydroxylation of surface Al atoms57. Notably, following the initial Na+ leaching, the shielding effect of the Si–O–Al framework on bulk Na⁺ and the inherently slow hydrolysis of Si–O–Al bonds (relative to ion leaching/water diffusion) may lead to stabilization of the hydrolysis front, potentially halting further dissolution. Compared to Na+ dissolution in pure aqueous systems, the leaching dynamics in sulfate solutions appear predominantly governed by SO42− interactions.

Interfacial hydrolysis reaction

Figure 11 presents a comparative schematic diagram illustrating hydrolysis reaction pathways and characteristic structures on different albite surfaces. The surface hydrolysis pathways exhibit significant structural dependence, primarily governed by the dual regulation of surface atomic coordination states and topological configurations. For the (100) surface (Fig. 11a), hydroxyl groups (OH−) generated through interfacial water dissociation coordinate with exposed Al atoms to form Al–OH configurations, while released protons (H+) are captured by bridge oxygen atoms in Al–O–Si frameworks to create Si–O(H)–Al structural states (Al–O–Si + H2O → Al(OH)–O(H)–Si). The (100) surface demonstrates relatively stable Al–O–Si bridging bond networks due to its lower surface energy, resulting in less extensive hydrolysis compared to other surfaces. On the (010) surface (Fig. 11b), partially unsaturated coordination states emerge from fractured silica-oxygen tetrahedral units. During hydrolysis, dissociated water molecules generate hydroxyl groups that directly coordinate with Si atoms to form surface silanol groups ([SiO3] + H₂O → [SiO3(OH)] + H+). Released protons migrate through surface diffusion to adjacent Al–O–Si bridge oxygen sites, forming protonated bridge oxygen structures (Al–O(H)–Si). Notably, no sulfate ion participation was observed in surface reactions here, consistent with previous discussions. The (001) surface exhibits distinct site-selective hydrolysis mechanisms (Fig. 11c). Upon hydrolysis initiation, hydroxyl groups coordinate with surface Al atoms to form Al–OH complexes ([AlO3] + H2O → [AlO3(OH)] + H+), while most protons are captured by terminal oxygen atoms in [SiO4] units to generate Si–OH terminations (Fig. 2c(vi)). This site selectivity reflects the screening effect of the topological structures of different albite surfaces on proton migration pathways58.

In this study, ReaxFF MD simulations were performed to investigate the anisotropic interfacial reaction mechanisms of albite with sulfate-rich solutions across its (100), (010), and (001) crystallographic surfaces. The simulation results reveal that fundamental differences in the stability and early-stage interfacial kinetic behavior of different surfaces of the albite mineral are governed by atomic coordination states, surface topological configurations, and sulfate interactions. Specifically, the (001) surface exposes a significant number of non-bridging oxygen atoms and undercoordinated Al atoms, promoting sulfate coordination adsorption and Na+ leaching. Dynamic analysis reveals that Na+ desorption is partially driven by sulfate-mediated coordination reactions, while another portion occurs through ion exchange mechanisms, accompanied by the rupture and reconstruction of surface Si–O–Al bonds. In contrast, the (100) surface maintains structural stability through a dense hydrogen bond network and Na+ shielding effects, which suppress Ca2+ adsorption and hydrolysis reactions. Meanwhile, the (010) surface restricts ion migration through the dense formation of silanol groups, with its surface Al atoms, embedded within the silica tetrahedral framework, showing almost no interaction with sulfate ions. Atomic-scale charge analysis highlighted electron transfer mechanisms. Al atoms lost electrons through coordination with water or sulfate, increasing their positive charge, while Si charge variations depended on neighboring oxygen atom density. MSD analysis further revealed anisotropic diffusion behaviors; the (001) surface displayed enhanced vertical mobility due to its layered structure and weak lattice constraints, whereas the (010) surface strongly suppressed ion migration due to the confinement of the dense structural network.

In summary, this study provides a novel perspective for investigating the subtle dissolution mechanisms at mineral–solution interfaces and pioneers initial pathways toward establishing a comprehensive theoretical framework for phenomena related to the different surface stabilities in mineral phases. These atomic-scale insights illuminate how crystallographic orientation dictates initial surface reconstruction dynamics and intrinsic stability. Regarding engineering implications, while the high initial reactivity of the (001) surface could accelerate early-stage mineral carbonation in CO2 sequestration, its propensity to be rapidly consumed or passivated during prolonged dissolution necessitates careful evaluation of long-term sustainability, potentially requiring strategies to harness the stability of less reactive faces like (100). Conversely, the demonstrated ion-shielding capability of the (100) surface aligns with the long-term geochemical stability demands of nuclear waste barrier materials. Future research will further integrate experimental validation and extend to multicomponent solution environments and longer simulation timescales to comprehensively evaluate mineral evolution in complex geological and engineered scenarios.

Methods

Atomistic model construction

In this study, the triclinic crystal structure file of low albite was sourced from the Cambridge Crystallographic Data Center (CCDC)59, and the structural parameters employed were obtained from the experimental data reported by Fröjdh et al.60. This fully ordered low albite structure was chosen specifically to investigate the intrinsic surface anisotropy arising from the crystallographic orientation within the triclinic framework, providing a clear baseline free from the averaging effects of disorder. The dimensions of the initial unit-cell parameters were set to a = 7.13000 Å, b = 7.38000 Å, c = 7.64000 Å, with angles α = 115.170°, β = 107.200°, and γ = 100.600°. After geometric optimization using density functional theory (DFT) methods61, the refined cell parameters became a = 7.18317 Å, b = 7.47293 Å, c = 7.73649 Å and α = 115.053°, β = 107.110°, γ = 100.782°. The (100), (010), and (001) crystallographic surfaces of albite were selected as the simulation interfaces. A 15 Å vacuum layer was introduced above each surface to avoid periodic image interactions. Subsequent geometric optimization was performed on these three surfaces, and their surface energies were calculated for further comparison. The optimized planes were then expanded into a 5 × 5 × 5 supercell. Each surface model comprises a total of 1164 atoms, including 128 Na, 128 Al, 384 Si, and 1024 O atoms. Next, a CaSO4 solution model containing 800 H2O molecules, 26 Ca2+, and 26 SO42− was constructed, and added to the albite surface to complete the atomic model construction, as shown in Fig. 12. The final simulation box had the dimensions of 30.21 × 29.9 × 73.99 Å3 for albite (100) surface, 28.52 × 30.56 × 75.25 Å3 for albite (010) surface, 28.73 × 29.76 × 75.47 Å3 for albite (001) surface, respectively.

Surface energy calculations

The albite crystal model was subjected to geometry optimization and surface energy calculations using DFT implemented in the CP2K/Quickstep software package62, employing the hybrid Gaussian and Plane Waves (GPW) method63. The exchange-correlation potential was described by the generalized gradient approximation (GGA) with the Perdew–Burke–Ernzerhof (PBE) functional64. The wavefunctions were expanded using a double zeta valence polarized (DZVP) basis set with a cutoff energy of 400 Ry65,66, complemented by auxiliary plane wave basis sets. Core electrons were treated using Goedecker–Teter–Hutter (GTH) pseudopotentials67. The energy convergence criterion was set to 10−12 Hartree, while the self-consistent field (SCF) convergence threshold was defined as 10−6 Hartree. A 3 × 3 × 2 Monkhorst–Pack k-point grid was employed for Brillouin zone sampling68, with the diagonalization method69 and wavefunction extrapolation strategy implemented through the Always Stable Predictor Corrector (ASPC) algorithm. The valence electron configurations used in these calculations were Na 3s1, Al 3s23p1, Si 3s23p2, O 2s22p4. In this study, the surface energy (γ) of different albite surfaces was calculated using the following formula:

where \({E}_{S}^{unopt}\) represents the energy of the unoptimized surface structure; \({E}_{b}\) denotes the energy of a single atom in the bulk material; N is the number of atoms included in the surface model; A is the surface area; \({E}_{S}^{opt}\) corresponds to the energy of the optimized surface structure.

ReaxFF MD simulation details

The ReaxFF MD simulations were performed using large-scale atomic/molecular massively parallel simulator (Lammps)70. The ReaxFF framework is a molecular dynamics potential function constructed based on the Bond Order (BO) theory developed by van Duin et al.71,72. Its key feature is its capability to dynamically describe chemical reaction processes between molecules. In this study, the specific ReaxFF parameters for Na/Al/Si/O/H were adopted from the work of Zhang et al.73, which enables reactive molecular modeling for various solid earth systems and interfacial systems. The parameters for Ca/S were sourced from Liu et al.74, who developed parameters to model calcium sulfate-aluminate interaction systems. (see ReaxFF parameters in the Supporting Information).

To ensure the rationality and stability of the ReaxFF MD simulation, all models underwent energy minimization relaxation using the conjugate gradient algorithm implemented in lammps prior to the molecular dynamics simulation. Periodic boundary conditions were set in the X and Y directions of the simulation box, while fixed boundary conditions were applied in the Z direction. A reflective wall was placed at the top of the simulation box to mitigate the impact of periodic phenomena on the simulation. The simulation was performed under the canonical (NVT) ensemble and the temperature was controlled at 298 K by coupling the system to a Nosé–Hoover thermostat with a coupling constant of 10.0 fs. The velocity-Verlet algorithm75 was used for the numerical integration of the equation of motion with a time step of 0.1 fs. The charge equilibration (QEq) method76 is used to calculate the atomic charge state at each computational step in the system. This approach inherently models the partial screening of charges in aqueous environments and at reactive interfaces, avoiding the use of fixed full-charge approximations. The dynamics of the motion trajectory are visualized every 1000 steps using OVITO software77.

For each distinct albite crystal plane that reacts with CaSO4 solution, perform a single independent ReaxFF MD trajectory with a duration of 2.5 ns. It should be noted that although comprehensive analysis indicates that the systems reached dynamic equilibrium for the initial interfacial reaction processes of interest within the simulation time, and a well-validated ReaxFF force field was employed, a single trajectory may have limitations in sampling rare events with slow kinetics. Nevertheless, this study clearly demonstrates significant differences in the initial interfacial interactions between distinct albite crystal planes and CaSO4 solution. Furthermore, the interfacial reaction process involves ion adsorption behavior, mineral surface reconstruction, and possible initial proton exchange or surface group modifications, which typically occur on timescales ranging from picoseconds to nanoseconds. Such simulation duration is generally sufficient for observing these rapid initial interfacial processes.

Data availability

The data will be made available upon request to the corresponding author.

Code availability

All the software used in this work is open source. No specific software was developed for this work.

References

Putnis, A. Why mineral interfaces matter. Science 343, 1441–1442 (2014).

Gruber, C. et al. Enhanced chemical weathering of albite under seawater conditions and its potential effect on the Sr ocean budget, Geochim. Cosmochim. Acta 271, 20–34 (2019).

Blum, A. E. & Stillings, L. L. Feldspar dissolution kinetics. In Chemical Weathering Rates of Silicate Minerals. (Mineralogical Society of America, Washington, 1995) pp 291–351.

Putnis, C. V. & Ruiz-Agudo, E. The mineral–water interface: where minerals react with the environment. Elements 9, 177–182 (2013).

Schott, J. et al. Mechanisms controlling albite dissolution/precipitation kinetics as a function of chemical affinity: new insights from experiments in 29Si spiked solutions at 150 and 180 °C. Geochim. Cosmochim. Acta 374, 284–303 (2024).

Beig, M. S. & Lüttge, A. Albite dissolution kinetics as a function of distance from equilibrium: Implications for natural feldspar weathering. Geochim. Cosmochim. Acta 70, 1402–1420 (2006).

Murphy, W. M. & Helgeson, H. C. Thermodynamic and kinetic constraints on reaction rates among minerals and aqueous solutions. III. Activated complexes and the pH-dependence of the rates of feldspar, pyroxene, wollastonite, and olivine hydrolysis. Geochim. Cosmochim. Acta 51, 3137–3153 (1987).

Arn’orsson, S. & Stef’ ansson, A. Assesment of feldspar solubility constants in the range of 0 degrees to 350 degrees C at vapor saturation pressures. Am. J. Sci. 299, 173–209 (1999).

Arvidson, R. S. & Luttge, A. Mineral dissolution kinetics as a function of distance from equilibrium—new experimental results. Chem. Geol. 279, 79–88 (2010).

Wohlers, A., Manning, C. E. & Thompson, A. B. Experimental investigation of the solubility of albite and jadeite in H2O, with paragonite + quartz at 500 and 700 ◦C, and 1-2.25 Gpa. Geochim. Cosmochim. Acta 75, 2924–2939 (2011).

Thorpe, C. L. et al. Forty years of durability assessment of nuclear waste glass by standard methods. npj Mater. Degrad. 5, 61 (2021).

Pollet-Villard, M. et al. Does crystallographic anisotropy prevent the conventional treatment of aqueous mineral reactivity? A case study based on K-feldspar dissolution kinetics. Geochim. Cosmochim. Acta 190, 294–308 (2016).

Fischer, C., Arvidson, R. S. & Lüttge, A. How predictable are dissolution rates of crystalline material?. Geochim. Cosmochim. Acta 98, 177–185 (2012).

Lüttge, A., Arvidson, R. S. & Fischer, C. Stochastic treatment of crystal dissolution kinetics. Elements 9, 183–188 (2013).

Fischer, C. et al. Variability of crystal surface reactivity: what do we know?. Appl. Geochem. 43, 132–157 (2014).

Daval, D. et al. Linking nm-scale measurements of the anisotropy of silicate surface reactivity to macroscopic dissolution rate laws: new insights based on diopside. Geochim. Cosmochim. Acta 107, 121–134 (2013).

Kurganskaya, I. & Luttge, A. Kinetic Monte Carlo approach to study carbonate dissolution. J. Phys. Chem. C 120, 6482–6492 (2016).

Shchukarev, A., Rosenqvist, J. & Sjöberg, S. XPS study of the silica–water interface. J. Electron. Spectrosc. Relat. Phenom. 137-140, 171–177 (2004).

Stone-Weiss, N. et al. An insight into the corrosion of alkali aluminoborosilicate glasses in acidic environments. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 22, 1881–1897 (2020).

Kohn, S., Dupree, R. & Smith, M. A multinuclear magnetic resonance study of the structure of hydrous albite glasses. Geochim. Cosmochim. Acta 53, 2925–2935 (1989).

Ishida, H. & Koenig, J. L. A Fourier-transform infrared spectroscopic study of the hydrolytic stability of silane coupling agents on e-glass fibers. J. Polym. Sci. Polym. Phys. Ed. 18, 1931–1943 (1980).

Collin, M. et al. ToF-SIMS depth profiling of altered glass. npj Mater. Degrad. 14, 3 (2019).

McPhail, D. Applications of secondary ion mass spectrometry (SIMS) in materials science. J. Mater. Sci. 41, 873–903 (2007).

Lea, A. S., Higgins, S. R., Knauss, K. G. & Rosso, K. M. A high-pressure atomic force microscope for imaging in supercritical carbon dioxide. Rev. Sci. Instrum. 82, 043709 (2011).

Fischer, C. & Luttge, A. Pulsating dissolution of crystalline matter. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 115, 897–902 (2018).

Lüttge, A., Bolton, E. W. & Lasaga, A. C. An interferometric study of the dissolution kinetics of anorthite: The role of reactive surface area. Am. J. Sci. 299, 652–678 (1999).

Fischer, C. & Luttge, A. Beyond the conventional understanding of water–rock reactivity. Earth Planet. Sci. Lett. 457, 100–105 (2017).

Hahn, S. H. et al. Development of a ReaxFF reactive force field for NaSiOx/water systems and its application to sodium and proton self-diffusion. J. Phys. Chem. C 122, 19713–19724 (2018).

Manzano, H. et al. Hydration of calcium oxide surface predicted by reactive force field molecular dynamics. Langmuir 28, 4187–4197 (2012).

Pitman, M. C. & van Duin, A. C. T. Dynamics of confined reactive water in smectite clay–zeolite. Compos. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 134, 3042–3053 (2012).

Senftle, T. et al. The ReaxFF reactive force-field: development, applications and future directions. npj Comput. Mater. 15011, 2 (2016).

Shen, F., Liu, G., Liu, C., Zhang, Y. & Yang, L. Corrosion and oxidation on iron surfaces in chloride contaminated electrolytes: insights from ReaxFF molecular dynamic simulations. J. Mater. Res. Technol. 29, 1305–1312 (2024).

Deng, L. et al. Reaction mechanisms and interfacial behaviors of sodium silicate glass in an aqueous environment from reactive force field-based molecular dynamics simulations. J. Phys. Chem. C 123, 21538–21547 (2019).

Kalahe, J. et al. Composition effect on interfacial reactions of sodium aluminosilicate glasses in aqueous solution. J. Phys. Chem. B 127, 279–284 (2023).

Kalahe, J. et al. Composition dependence of the atomic structures and properties of sodium aluminosilicate glasses: molecular dynamics simulations with reactive and nonreactive potentials. J. Phys. Chem. B 127, 5327–5342 (2022).

Biber, M. V. et al. The coordination chemistry of weathering: IV. Inhibition of the dissolution of oxide minerals. Geochim. Cosmochim. Acta 58, 1999–2010 (1994).

Furrer, G. & Stumm, W. The coordination chemistry of weathering: I. Dissolution kinetics of δ-Al2O3 and BeO. Geochim. Cosmochim. Acta 50, 1847–1870 (1987).

Jabraoui, H. et al. Leaching and reactivity at the sodium aluminosilicate glass-water interface: insights from a ReaxFF molecular dynamics study. J. Phys. Chem. C. 125, 27170–27184 (2021).

Du, J. & Rimsza, J. M. Atomistic computer simulations of water interactions and dissolution of inorganic glasses. npj Mater. Degrad. 1, 16 (2017).

Deng, L. et al. Ion-exchange mechanisms and interfacial reaction kinetics during aqueous corrosion of sodium silicate glasses. npj Mater. Degrad. 5, 15 (2021).

Xiao, Y. & Lasaga, A. C. Ab initio quantum mechanical studies of the kinetics and mechanisms of silicate dissolution: H+(H3O+) catalysis. Geochim. Cosmochim. Acta 58, 5379–5400 (1994).

Hellmann, R. et al. Nanometre-scale evidence for interfacial dissolution–reprecipitation control of silicate glass corrosion. Nat. Mater. 14, 307–311 (2015).

Kumar, R., Schmidt, J. R. & Skinner, J. L. Hydrogen bonding definitions and dynamics in solution water. J. Chem. Phys. 127, 204107 (2007).

Wang, Y. & Wang, Y. HB calculator: a tool for hydrogen bond distribution calculations in molecular dynamics simulations. J. Chem. Inf. Model. 74, 1772–1777 (2024).

Ngo, D. et al. Hydrogen bonding interactions of H2O and SiOH on a boroaluminosilicate glass corroded in aqueous solution. npj Mater. Degrad. 4, 1 (2020).

Bañuelos, J. L. et al. Oxide− and silicate−water interfaces and their roles in technology and the environment. Chem. Rev. 123, 6413–6544 (2023).

Tong, Z. et al. A room temperature dissolution solvent and its mechanism for natural biopolymers: hydrogen bonding interaction investigation. Green. Chem. 25, 5086–5096 (2023).

Jabraoui, H. et al. Leaching and reactivity at the sodium aluminosilicate glass−water interface: insights from a ReaxFF. Mol. Dyn. Study, J. Phys. Chem. C 125, 27170–27184 (2021).

Skipper, N. T. & Neilson, G. W. X-ray and neutron diffraction studies on concentrated aqueous solutions of sodium nitrate and silver nitrate. J. Condens. Matter Phys. 1, 4141 (1989).

Mähler, J. & Persson, I. A study of the hydration of the alkali metal ions in aqueous solution. Inorg. Chem. 51, 425–438 (2012).

Jalilehvand, F. et al. Hydration of the calcium ion. An EXAFS, large-angle X-ray scattering, and molecular dynamics simulation study. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 123, 431–441 (2001).

Fischer, T. et al. Crystal structure of oxonium bis(sulfato) aluminate, H3O[Al(SO4)2]. Z. Kristallogr 211, 465 (1996).

Gao, J. et al. Anisotropic effects in local anodic oxidation nanolithography on silicon surfaces: insights from ReaxFF molecular Dynamics. Langmuir 40, 15530–15540 (2024).

Frankel, G. S. et al. A comparative review of the aqueous corrosion of glasses, crystalline ceramics, and metals. npj Mater. Degrad. 2, 15 (2018).

Giraudo, N. et al. Corrosion of concrete by water-induced metal–proton exchange. J. Phys. Chem. C 120, 22455–22459 (2017).

Thissen, P. Exchange reactions at mineral interfaces. Langmuir 37, 10293–10307 (2020).

Sykes, D. & Kubicki, J. D. A model for H2O solubility mechanisms in albite melts from infrared spectroscopy and molecular orbital calculations. Geochim. Cosmochim. Acta 57, 1039–1052 (1993).

Blum, A. E. & Lasaga, A. C. The role of surface speciation in the dissolution of albite. Geochim. Cosmochim. Acta 55, 2193–2201 (1991).

Fröjdh, E. et al. CSD 2042879: Experimental Crystal Structure Determination. (2020).

Fröjdh, E. et al. Discrimination of aluminum from silicon by electron crystallography with the JUNGFRAU Detector. Crystals 10, 1148 (2020).

Runge, E. & Gross, E. K. U. Density-functional theory for time dependent systems. Phys. Rev. Lett. 997, 52 (1984).

VandeVondele, J. et al. Quickstep: fast and accurate density functional calculations using a mixed Gaussian and plane waves approach. Comp. Phys. Commun. 177, 103–128 (2005).

Lippert, B. G., Hutter, J. & Parrinello, M. A hybrid Gaussian and plane wave density functional scheme. Mol. Phys. 92, 477–488 (2010).

Perdew, J. P., Burke, K. & Ernzerhof, M. Generalized gradient approximation made simple. Phys. Rev. Lett. 77, 3875 (1997).

Vandevondele, J. & Hutter, J. Gaussian basis sets for accurate calculations on molecular systems in gas and condensed phases. J. Chem. Phys. 127, 114105 (2007).

Hartwigsen, C., Goedecker, S. & Hutter, J. Relativistic separable dual-space Gaussian pseudopotentials from H to Rn. Phys. Rev. B. 58, 3741–3772 (1998).

Goedecker, S., Teter, M. & Hutter, J. Separable dual-space Gaussian pseudopotentials. Phys. Rev. B Condens Matter 54, 1703–1710 (1997).

Monkhorst, H. J. & Pack, J. D. Special points for Brillouin-zone integrations. Phys. Rev. B Condens. Matter 13, 5188–5192 (1977).

Marek, A. et al. The ELPA library: scalable parallel eigenvalue solutions for electronic structure theory and computational science. J. Phys. 27, 213201 (2014).

Thompson, A. P. et al. LAMMPS—a flexible simulation tool for particle-based materials modeling at the atomic, meso, and continuum scales. Comput Phys. Commun. 271, 108171 (2022).

van Duin, A. C. T., Dasgupta, S., Lorant, F. & Goddard, W. A. ReaxFF: a reactive force field for hydrocarbons. J. Phys. Chem. A 105, 9397–9409 (2001).

van Duin, A. C. T. et al. ReaxFF SiO reactive force field for silicon and silicon oxide systems. J. Phys. Chem. A 107, 3803–3811 (2003).

Zhang, Y. et al. Development and validation of a general-purpose ReaxFF reactive force field for earth material modeling. J. Chem. Phys. 170, 094103 (2024).

Liu, L. et al. Development of a ReaxFF reactive force field for ettringite and study of its mechanical failure modes from reactive dynamics simulations. J. Phys. Chem. A 117, 15 (2012).

Verlet, L. Computer “Experiments” on classical fluids. I. thermodynamical properties of Lennard-Jones molecules. Phys. Rev. 159, 98 (1977).

Rappe, A. K. & Goddard, W. A. Charge equilibration for molecular-dynamics simulations. J. Phys. Chem. 95, 3358–3363 (1991).

Stukowski, A. Visualization and analysis of atomistic simulation data with OVITO-the Open Visualization Tool. Model. Simul. Mater. Sci. Eng. 18, 015012 (2010).

Acknowledgements

The authors gratefully acknowledge the financial supports from the National Natural Science Foundation of China (52308237), National Key Research and Development Program of China (2023YFB3711400), Natural Science Foundation of Jiangsu Province (No. BK20220854), and Fundamental Research Funds for the Central Universities (No. RF1028623108). This research work was supported by the Big Data Computing Center of Southeast University.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

F. Shen: Methodology, Investigation, Software, Writing-original draft. J. Tang: Conceptualization, Methodology, Investigation, Writing-review & editing, Supervision. Y. Wang: Methodology, Investigation, Software. G. Liu: Methodology, Formal analysis, Validation. C. Liu: Resources, Formal analysis, Writing-review & editing. All authors read and approved the final paper.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Shen, F., Tang, J., Wang, Y. et al. Molecular-scale understanding of crystallographic controlled anisotropic dissolution of albite in sulfate solution. npj Mater Degrad 9, 123 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41529-025-00672-w

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41529-025-00672-w