Abstract

The structural and electronic recovery of β-SiC nanopowders after gamma irradiation was investigated through post-irradiation thermal annealing. Gamma exposure induced significant lattice disorder, peak broadening, and reduced carrier mobility, evidencing radiation-driven degradation. Subsequent annealing at 1100 °C partially restored crystallinity and improved transport properties, as confirmed by XRD, FTIR, DRS, FESEM, and Hall effect analyses. The results reveal that thermal energy promotes defect recombination and grain growth, enabling partial reversal of radiation damage. The irradiated samples exhibited enhanced recovery compared to pristine powders, demonstrating the combined impact of pre-existing defects and annealing on defect dynamics. Although full restoration was not achieved, the findings highlight thermal annealing as an effective strategy to improve the stability of radiation-damaged SiC. This study advances understanding of defect recovery in wide-bandgap ceramics and outlines a practical route to tailoring their performance in radiation-intensive and high-temperature environments relevant to nuclear and space applications.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Silicon carbide (SiC) is a well-established wide-bandgap semiconductor, valued for its high thermal conductivity, mechanical strength, chemical stability, and notable resistance to radiation-induced damage1,2,3. These features make it highly suitable for power electronics, high-frequency systems, and applications in extreme thermal environments4,5. Among its various crystalline forms, the cubic β-phase (3C-SiC) stands out for its excellent carrier transport characteristics and compatibility with conventional silicon-based technologies6. In nanocrystalline form, SiC offers additional benefits, such as a large surface-to-volume ratio, enhanced defect reactivity, and high sensitivity to external stimuli, making it a promising candidate for use in sensors, energy devices, and radiation-hardened systems7,8. Exposure to ionizing radiation can lead to defect formation in SiC, although the underlying mechanisms differ depending on the radiation type. Neutron flux primarily generates defects through ballistic displacement of lattice atoms, whereas gamma rays interact through ionization, Compton scattering, and electronic excitations, which indirectly promote the formation of vacancies, interstitials, and antisites9,10,11,12,13,14. Recent studies on diverse material systems, including WO3 thin films15, ZrO2 thin films16, and Kapton-H polymer17 have demonstrated that gamma irradiation induces significant structural, optical, and chemical modifications, highlighting its broad impact across ceramics, oxides, and polymers. These findings further emphasize the importance of investigating recovery pathways in wide-bandgap semiconductors such as SiC. In a previous study, we reported the structural and electronic modifications of β-SiC nanopowders under gamma irradiation18. In the present study, our focus is placed on the subsequent thermal recovery process, as gamma rays, owing to their high penetration depth and relevance to nuclear and space environments, provide a representative platform for studying defect dynamics in nanostructured SiC. These radiation-induced defects distort the crystal lattice, reduce crystallinity, and hinder charge carrier transport, ultimately degrading the performance of semiconductor-based devices. Interestingly, under well-controlled conditions, such defects can also be exploited to tailor material properties, enabling engineered functionalities in wide-bandgap systems19,20,21,22. In nanostructured materials, these effects are often more pronounced due to the high density of grain boundaries and surface states, which enhance defect interactions and increase carrier scattering23,24,25.

Thermal annealing is widely used as a post-irradiation treatment to heal structural damage, promote defect recombination, and restore lattice order, leading to improved crystallinity and charge transport properties26,27,28,29. However, the outcome of annealing is strongly influenced by the nature and concentration of radiation-induced defects, which vary with irradiation dose and energy. Therefore, the objective of this study is not to revisit the irradiation effects, but to investigate thermal annealing as a standalone recovery strategy for β-SiC nanopowders previously subjected to gamma doses of 100 and 150 kGy. By systematically analyzing the evolution of structure and charge transport before and after annealing, the study aims to deepen our understanding of defect dynamics and to explore practical pathways for restoring and tuning the properties of radiation-damaged semiconductor nanomaterials.

Results and discussion

XRD analysis

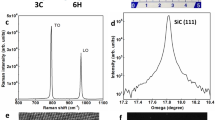

XRD measurements were carried out using Cu Kα radiation (\(\lambda\) = 1.54184 A) operated at 40 kV and 30 mA. Data were collected over a 2θ range of 10–80˚ with a step size of 0.05˚ and a counting time of 1 s per point. Figure 1 shows the XRD patterns of SiC nanopowders before and after gamma irradiation, as well as following thermal annealing. The NS0 sample displays sharp diffraction peaks with narrow full width at half maximum (FWHM), characteristic of the β-SiC (3 C) polytype, indicating high crystallinity and minimal lattice defects30,31. Following gamma irradiation at doses of 100 and 150 kGy, the diffraction patterns of NS100 and NS150 exhibit noticeable peak broadening (increased FWHM) and a reduction in peak intensity. These changes are attributed to radiation-induced lattice distortions and the accumulation of point defects such as vacancies, interstitials, and dislocations32. In addition to the dominant (111) reflection at ~35.9˚, weak shoulders are visible in its vicinity, which are attributed to stacking faults, local polytypic sequences (6H/15R-like ordering), and strain fields arising from irradiation-induced defects.

Thermal annealing at 1100 °C induces subtle yet significant structural modifications. In comparison to the irradiated samples (NS100 and NS150), the annealed counterparts (TNS100 and TNS150) exhibit broader FWHM but larger crystallite sizes, indicating that pre-existing irradiation-induced defects act as diffusion pathways which accelerate recrystallization and grain coarsening. These results highlight the role of thermal energy in enhancing atomic mobility, thereby facilitating local defect recombination and promoting nanoscale structural recovery. The overall peak intensities of TNS0, TNS100, and TNS150 are reduced relative to their pristine or irradiated states. This decrease does not imply a loss of crystallinity but arises from extrinsic factors such as reduced packing density in annealed powders, preferred orientation effects, and partial surface oxidation, which increase X-ray absorption14,29,33. Notably, the TNS150 sample displays a new diffraction peak at approximately 2θ ≈ 11.7˚, along with pronounced changes across the diffraction profile, indicating more extensive structural evolution driven by the combined effects of high-dose irradiation and thermal activation. The emergence of this additional peak in TNS150 may signify the formation of a secondary phase—such as silicon oxide—or localized structural rearrangements resulting from processes like phase segregation, oxidation, or re-nucleation14,33.

The crystallite size for each sample was estimated using the Debye–Scherrer method.

Here, β represents the FWHM of the diffraction peak, λ (1.5418 Å) is the X-ray wavelength, k is the Scherrer constant, which depends on the crystallites, and θ is the Bragg angle corresponding to the center of the diffraction peak34. Table 1 shows the results from the analysis of X-ray diffraction data, including crystallite size of our samples.

As summarized in Table 1, a consistent increase in crystallite size is observed across all sample groups following thermal annealing, indicating that heat treatment facilitates defect recombination and promotes partial grain growth. This effect is particularly pronounced in the irradiated samples, where pre-existing irradiation-induced defects enhance atomic mobility during annealing, thereby accelerating recrystallization and grain coarsening. This effect is particularly strong in irradiated samples, where gamma-induced defects provide nucleation and migration sites for recrystallization, thereby magnifying the grain coarsening process during annealing. In particular, TNS150 exhibits the largest crystallite size (25.9 nm), highlighting the synergistic role of high-dose irradiation and subsequent thermal activation in driving extended structural reorganization.

FTIR spectroscopy

FTIR spectra were collected in the range of 400–4000 cm−1 with a resolution of 4 cm−1, averaging 32 scans for each measurement using the ATR technique with a diamond crystal. Figure 2 presents the FTIR spectra of SiC nanopowders before and after gamma irradiation followed by thermal annealing. All samples exhibit characteristic vibrational bands associated with Si–C, Si–O, and C–H bonds.

The absorption band centered around 800 cm−1, attributed to the transverse optical (TO) mode of Si–C stretching, serves as a reliable signature of the crystalline β-SiC phase. In the NS0 sample, this band appears sharp and well-defined, indicating a highly ordered Si–C bonding network. Following irradiation, the NS100 and NS150 samples exhibit broadened and slightly red-shifted Si–C bands, reflecting lattice distortions and bond disorder. Thermal annealing results in sharpening and intensity enhancement of this band, with the most significant recovery observed in TNS150, suggesting that thermal energy promotes the reordering of disrupted bonds and supports recrystallization within the SiC matrix35.

A broad absorption band between 1000 and 1200 cm−1, assigned to asymmetric Si–O–Si stretching vibrations, is observed in all samples. Its intensity increases after irradiation, likely due to defect-assisted oxygen uptake and surface oxidation. Following annealing, this band narrows and decreases in intensity, indicating partial removal or reconfiguration of surface-bound oxygen species. After annealing, this band exhibits pronounced modifications, particularly in irradiated samples, where it becomes sharper and more intense. This behavior indicates stabilization of oxygen-related species at the surface or grain boundaries, consistent with the additional XRD peak observed at ~11.7˚. The correlation between these two observations suggests that FTIR and XRD provide complementary evidence for oxide-related secondary phase formation or localized structural rearrangements induced by the combined effects of gamma irradiation and thermal treatment.

Weak absorption features near 2900 cm−1, corresponding to C–H stretching vibrations, are consistently detected across all samples. These bands likely originate from residual organic compounds or adsorbed carbon and exhibit minimal sensitivity to irradiation or thermal treatment. The evolution of the FTIR spectra, particularly in the Si–C and Si–O–Si regions, underscores the role of thermal annealing in reversing gamma-induced structural disorder. The restoration of local bonding order, modification of oxide-related features, and overall enhancement in spectral uniformity collectively highlight the effectiveness of post-irradiation annealing in recovering the structural and chemical integrity of SiC nanopowders.

FESEM analysis

FESEM imaging was performed at an acceleration voltage of 20 kV in secondary electron (SE) mode, and representative micrographs were analyzed for particle size distribution. Figure 3 displays FESEM images of SiC nanopowders before and after gamma irradiation followed by thermal annealing. The NS0 sample exhibits a relatively compact morphology, characterized by semi-spherical nanoparticles irregularly distributed across the surface. The moderate level of agglomeration observed suggests strong interparticle interactions, likely driven by the high surface energy inherent to nanoscale SiC.

Gamma irradiation results in noticeable morphological degradation, particularly in the NS100 and NS150 samples, where particle boundaries become less distinct and surface textures appear rougher. These changes are attributed to irradiation-induced damage, including the formation of point defects and localized amorphization, which disrupt surface uniformity and weaken grain coherence. These observations are consistent with reports on irradiated SiC systems36,37. Thermal annealing exerts a restorative effect on the irradiated samples. In TNS100 and TNS150, the particles display more defined contours, smoother surfaces, and improved intergranular connectivity. Notably, TNS150 demonstrates significant morphological improvements, characterized by denser particle packing and enhanced surface uniformity. These features are consistent with grain coarsening and densification processes facilitated by increased atomic mobility at elevated temperatures14,27. TNS0 also exhibits moderate grain growth and surface refinement compared to NS0, indicating that annealing alone promotes morphological improvements through grain boundary migration and structural relaxation28. Similar thermally induced enhancements have been reported in other high-silicon and nanostructured materials37,38, suggesting the broader relevance of these mechanisms beyond SiC.

Table 2 summarizes the elemental composition of the samples based on EDS analysis. A comparative evaluation reveals the complex effects of thermal annealing on the surfaces of irradiated SiC nanopowders. While gamma irradiation alone (NS100 and NS150) leads to moderate increases in surface oxygen content (6.9% and 16.8%, respectively), subsequent annealing results in a substantial rise, particularly in TNS100 (20.1%). This increase may be attributed to enhanced surface reactivity induced by prior irradiation, facilitating localized oxidation during annealing despite the inert atmosphere. The intermediate damage level in NS100 may promote partial defect healing, enabling oxygen incorporation without full surface restructuring. Concurrent decreases in Si and C contents in TNS100 suggest surface restructuring or volatilization of surface species. In contrast, the comparison between NS0 and TNS0 reflects a typical annealing response: increases in Si and C contents alongside a minor rise in oxygen level, indicative of moderate surface densification and reorganization without prior irradiation damage. It should be noted that EDS is a semiquantitative technique with an intrinsic error margin of up to ±5%, which accounts for minor deviations in the total percentages. The relatively high oxygen content, particularly in the pristine sample, is attributed to native surface oxides and adsorbed oxygen-containing species typical of nanocrystalline SiC powders. These compositional changes highlight the dual role of thermal annealing: it can either restore or further modify surface chemistry depending on the pre-existing defect landscape. The combined FESEM and EDS results confirm that thermal annealing improves morphological regularity while simultaneously influencing surface chemistry. These findings are consistent with studies, such as those by Bratus et al., who reported defect healing and recrystallization in neutron-irradiated β-SiC, and Frazer et al., who demonstrated oxygen redistribution and microstructural recovery in SiC/SiC composites subjected to thermal stress36,39.

DRS analysis

Diffuse reflectance spectra were measured in the wavelength range of 200–1200 nm with a spectral resolution of 1 nm to ensure reliable determination of absorption edges. Figure 4 presents the DRS spectra of SiC nanopowders subjected to gamma irradiation and subsequent thermal annealing. All samples exhibit broad absorption features in the UV–visible region, characteristic of indirect bandgap semiconductors like SiC. Variations in optical absorption among the samples reflect the combined effects of irradiation-induced defect formation and thermally driven structural reorganization.

The NS0 sample shows moderate UV absorption, whereas TNS0 exhibits a slightly sharper and more intense absorption edge, suggesting improved electronic transitions resulting from partial structural recovery. In the irradiated samples (NS100 and NS150), a noticeable increase in absorption across the UV–visible range is observed, likely due to the introduction of defect-related electronic states within the bandgap. Following thermal annealing, TNS100 and TNS150 demonstrate further enhancement in absorption, accompanied by a subtle red-shift in the absorption edge, indicating modifications in defect states and partial restoration of the band structure. In the irradiated samples (NS100 and NS150), the noticeable increase in absorption across the UV-visible range is attributed to irradiation-induced point defects. Si vacancies (VSi) and C vacancies (VC) introduce states close to the band edges, while antisite defects (SiC, CSi) and oxygen-related species generate additional mid-gap levels. These combined defects broaden the absorption edge and enhance sub-bandgap absorption26,29,30. Following thermal annealing, TNS100 and TNS150 exhibit a partial recovery, consistent with recombination of vacancies and relaxation of antisite defects, which leads to a sharper absorption profile and partial restoration of the electronic structure36.

These optical trends correlate well with the structural observations from XRD (crystallite growth and peak sharpening), FTIR (bond reordering and reduced Si–O–Si features), and FESEM (morphological refinement), collectively confirming that thermal annealing facilitates both structural and electronic recovery in irradiated SiC. The progressive shift in the absorption edge across the NS and TNS sample series underscores the sensitivity of SiC’s optical response to radiation damage and thermal repair, reinforcing the effectiveness of post-irradiation annealing in tailoring the optoelectronic properties of SiC nanomaterials.

Hall effect analysis

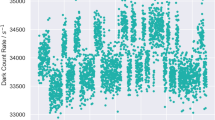

Hall effect measurements were performed at room temperature under a perpendicular magnetic field of 0.5 T using the van der Pauw configuration with four-point probe contacts. The applied current was set to 1 mA, and carrier concentration, mobility, and resistivity were automatically calculated by the system software. Figure 5 displays the SiC films fabricated using the doctor blade technique and subsequently dried under ambient conditions. These freestanding films were utilized for Hall effect measurements to assess the electrical transport properties of the samples.

The electrical transport parameters extracted from Hall effect measurements included Hall voltage (VH), resistivity (\(\rho\)), conductivity (\(\sigma\)), Hall coefficient (RH), carrier concentration (n), mobility (\(\mu\)), and magnetoresistance (MR). The majority carrier type was identified based on the sign of RH and VH. These values, presented in Table 3, were determined using conventional models established in solid-state physics40,41.

The Hall effect measurements reveal distinct trends illustrating the influence of gamma irradiation and subsequent thermal annealing on the electronic transport behavior of β-SiC nanopowders. The unirradiated reference sample (NS0) exhibited n-type conductivity, characterized by a low carrier concentration of 8.23 × 1011 cm−3, moderate mobility (50.7 cm2/V.s), and relatively high resistivity. These features reflect a structurally ordered system with minimal intrinsic defects and low charge scattering, establishing NS0 as a benchmark for evaluating radiation-induced perturbations42. Following gamma irradiation, NS100 displayed a substantial increase in mobility to 512.3 cm2/V.s, accompanied by a dramatic reduction in carrier concentration to 9.31 × 109 cm−3. This behavior suggests the formation of fragmented conduction pathways within disordered regions, likely caused by defect clustering and partial amorphization. The low carrier density may reflect trap-dominated conduction or the emergence of localized states suppressing free carrier generation, while the high mobility may result from preferential conduction through isolated ordered domains22,43. At a higher dose (NS150), n-type conductivity persisted; however, the carrier concentration rose to 2.65 × 1010 cm−3 while mobility decreased to 229.8 cm2/V.s, implying the emergence of donor-like trap states and intensified carrier scattering effects, consistent with structural disruption and localized charge localization4,13. Thermal annealing exerted a pronounced restorative effect. In TNS100, carrier concentration increased to 5.25 × 1010 cm−3, while mobility decreased to 100.8 cm2/V.s, suggesting partial passivation of radiation-induced traps and reformation of continuous transport networks. Notably, TNS150 exhibited the most significant recovery, with mobility rising to 328.8 cm2/V.s and carrier concentration stabilizing at 1.66 × 1010 cm−3. These results indicate effective defect recombination and structural reordering, in agreement with improved crystallinity and reduced surface oxidation observed in complementary characterizations24,29.

Variations in the Hall coefficient and MR further reflect these transitions. Samples with higher lattice order exhibited greater MR values and more coherent charge transport, whereas heavily disordered samples showed suppressed MR due to disrupted conduction pathways. The recovery of MR and mobility following annealing underscores the critical role of thermal activation in restoring long-range order, stabilizing electronic transport, and mitigating the electronic degradation induced by gamma irradiation42.

This study has demonstrated that thermal annealing at 1100˚C plays a decisive role in mitigating radiation-induced degradation in β-SiC nanopowders. While gamma irradiation generated lattice disorder and reduced electronic mobility, subsequent heat treatment facilitated partial defect recombination and crystallite growth, leading to measurable improvements in both structural and electronic properties. The recovery remained incomplete, underscoring the complex nature of defect evolution in nanocrystalline ceramics. Importantly, these results confirm that controlled annealing provides a practical pathway to enhance the radiation tolerance of SiC for use in demanding environments. Future research should explore the influence of different annealing conditions, extended irradiation doses, and alternative radiation sources (e.g., ion or neutron beams) to fully establish the limits of recovery and long-term stability of SiC nanomaterials in nuclear and space applications.

Methods

Sample preparation

High-purity β-phase SiC nanopowder (purity >99%, particle size: 45–65 nm; US Research Nanomaterials, USA) was utilized as the starting material. The details of the gamma irradiation procedure, including dose conditions and exposure setup, have been previously reported18. Based on those findings, three representative samples were selected for thermal annealing: NS0 (unirradiated control), NS100 (irradiated at 100 kGy), and NS150 (irradiated at 150 kGy), corresponding to progressively higher levels of radiation-induced damage. After annealing, the samples were designated as TNS0, TNS100, and TNS150, respectively. Figure 6 shows the schematic workflow of the experimental procedure, including irradiation, annealing, and analysis steps.

Thermal annealing was performed in a tubular furnace (Carbolite, UK) under continuous argon flow. The samples were initially heated to 700 °C and maintained at that temperature for 1 h, followed by annealing at 1100 °C for 3 h. Cooling to room temperature was conducted gradually under the same argon atmosphere to minimize thermal stress.

For electrical characterization, SiC films were prepared by dispersing the nanopowders in distilled water containing polyethylene glycol (PEG) and polyvinyl alcohol (PVA) as binder agents. The resulting suspensions were magnetically stirred for 15 min to ensure uniform dispersion and subsequently coated onto pre-cleaned glass substrates using the doctor blade method. The films were then dried at room temperature before characterization.

Analysis

Structural properties were examined using X-ray diffraction (XRD; AW-XDM300, ASENWARE). Surface morphology was investigated by field emission scanning electron microscopy (FESEM; Sigma 300-HV, Zeiss), and chemical bonding information was obtained via Fourier-transform infrared spectroscopy (FTIR; Jasco 6300). Optical properties were assessed through diffuse reflectance spectroscopy (DRS; UV-3600, Shimadzu). Electrical properties were evaluated using Hall effect measurements (HMS 7000, Ecopia) at room temperature.

Data availability

The relevant data are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

References

Vali, I. P. et al. Structural and optical studies of gamma irradiated N-doped 4H-SiC. Nucl. Instrum. Methods Phys. Res. B 440, 101–106 (2019).

Huseynov, E. M., Garibov, A. A. & Valiyev, S. P. EPR study of silicon nitride (Si₃N₄) nanoparticles exposed to neutron irradiation. Radiat. Phys. Chem. 195, 110087 (2022).

Huseynov, E., Jazbec, A. & Snoj, L. Temperature vs. impedance dependencies of neutron-irradiated nanocrystalline silicon carbide (3C–SiC). Appl. Phys. A 125, 9 (2019).

De Napoli, M. SiC detectors: a review on the use of silicon carbide as radiation detection material. Front. Phys. 10, 898833 (2022).

Rafin, S. M. S. H. et al. Power electronics revolutionized: a comprehensive analysis of emerging wide and ultrawide bandgap devices. Micromachines 14, 2045 (2023).

Raynaud, C., Tournier, D., Morel, H. & Planson, D. Comparison of high voltage and high temperature performances of wide bandgap semiconductors for vertical power devices. Diam. Relat. Mater. 19, 1–6 (2010).

Hashim, A., Abbas, M. H., Al-Aaraji, N. A. & Hadi, A. Facile fabrication and developing the structural, optical and electrical properties of SiC/Y₂O₃ nanostructures doped PMMA for optics and potential nanodevices. Silicon 15, 1283–1290 (2023).

Ahmed, G. & Hashim, A. Synthesis and tailoring morphological and optical characteristics of PMMA/PEG/Si₃N₄ hybrid nanomaterials for optics and quantum nanoelectronics applications. Silicon 15, 7085–7093 (2023).

Cheng, Q., Xu, S. & Ostrikov, K. K. Single-step, rapid low-temperature synthesis of Si quantum dots embedded in an amorphous SiC matrix in high-density reactive plasmas. Acta Mater. 58, 560–569 (2010).

Shen, Y. et al. Structural features and photoelectric properties of Si-doped GaAs under gamma irradiation. Nanomaterials 10, 340 (2020).

Ruddy, F. H. & Seidel, J. G. The effects of intense gamma-irradiation on the alpha-particle response of silicon carbide semiconductor radiation detectors. Nucl. Instrum. Methods Phys. Res. B 263, 163–168 (2007).

Ohshima, T., Itoh, H. & Yoshikawa, M. Effect of gamma-ray irradiation on the characteristics of 6H silicon carbide MOSFET with hydrogen-annealed gate oxide. J. Appl. Phys. 90, 3038–3041 (2001).

Tala-Ighil, B., Trolet, J. L., Gualous, H., Mary, P. & Lefebvre, S. Experimental and comparative study of gamma radiation effects on Si-IGBT and SiC-JFET. Microelectron. Reliab. 55, 1512–1516 (2015).

Švec, M. et al. Effect of higher silicon content and heat treatment on structure evolution and high-temperature behaviour of Fe-28Al-15Si-2Mo alloy. Materials 14, 3031 (2021).

Gupta, D. et al. Influence of gamma radiation on optical, structural and surface morphological properties of WO₃ thin films grown by RF sputtering. Radiat. Phys. Chem. 202, 110554 (2023).

Chauhan, V. et al. Influence of high dose gamma radiation on optical, physico-chemical and surface morphology properties of nanocrystalline ZrO₂ thin films. Opt. Mater. 126, 112125 (2022).

Singh, P. et al. High dose gamma radiation exposure upon Kapton-H polymer for modifications of optical, free volume, structural and chemical properties. Optik 205, 164244 (2020).

Soltanifar, F., Ebrahimibasabi, E. & Shahidi, M. M. Gamma radiation effects on SiC nanopowders: structural, morphological, optical and electrical evolution. Ceram. Int. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ceramint.2025.02.305 (2025).

Singh, G. et al. Evaluating the irradiation effects on the elastic properties of miniature monolithic SiC tubular specimens. J. Nucl. Mater. 499, 107–110 (2018).

Yamashita, N. et al. Surface morphology changes of silicon carbide by helium plasma irradiation. Nucl. Mater. Energy 16, 145–148 (2018).

Song, J. et al. Development of a silicon carbide radiation detection system and experimentation of the system performance. Appl. Radiat. Isot. 214, 111555 (2024).

Park, J. et al. Effect of metal electrode on characteristics of gamma-irradiated silicon carbide detector. J. Nucl. Sci. Technol. 51, 482–486 (2014).

Huseynov, E. & Jazbec, A. EPR spectroscopic studies of neutron-irradiated nanocrystalline silicon carbide (3C–SiC). Silicon 11, 1801–1807 (2019).

Du, Q. et al. Real-time, in situ probing of gamma radiation damage with packaged integrated photonic chips. Photonics Res 8, 186–193 (2020).

Babasafari, Z. et al. Effect of silicon and partitioning temperature on the microstructure and mechanical properties of high-carbon steel in a quenching and partitioning heat treatment. J. Mater. Sci. 56, 15423–15440 (2021).

Kasper, C. et al. Influence of irradiation on defect spin coherence in silicon carbide. Phys. Rev. Appl. 13, 044054 (2020).

Rijks, H. J., Bloem, J. & Giling, L. J. Heat treatment of silicon and the nature of thermally induced donors. J. Appl. Phys. 50, 1370–1374 (1979).

Sedlaček, M. et al. Influence of austempering of As-cast medium carbon high-silicon steel on wear resistance. Materials 14, 7518 (2021).

Feng, H. et al. Radiation effects and mechanisms on switching characteristics of silicon carbide power MOSFETs. J. Nanoelectron. Optoelectron. 16, 1423–1429 (2021).

Mirzayev, M. N. et al. Investigation of the formation of defects under fast neutrons and gamma irradiation in 3C–SiC nano powder. Phys. B 611, 412842 (2021).

Kim, C., Yoon, H., Kim, D. S. & Seok, O. Comparison analysis of radiation effects on 1.2 kV SiC MOSFETs with gamma-ray and proton irradiation. Electronics 13, 1352 (2024).

Wan, Z., Huang, S., Green, M. A. & Conibeer, G. Rapid thermal annealing and crystallization mechanisms study of silicon nanocrystal in silicon carbide matrix. Nanoscale Res. Lett. 6, 129 (2011).

Zhang, L. et al. Grain size variation in nanocrystalline silicon carbide irradiated at elevated temperatures. J. Am. Ceram. Soc. 102, 448–455 (2019).

Viswanathan, B., Dharmaraja, J. & Balamurugan, J. Structural parameters and optical constants of CdS nanocrystalline thin films. Nano 6, 251–258 (2011).

Arduino, D. et al. Silicon and silicon carbide recrystallization by laser annealing: a review. Materials 16, 7674 (2023).

Bratus, V. Y. A., Melnyk, R. S., Shanina, B. D. & Okulov, S. M. Thermal annealing and evolution of defects in neutron-irradiated cubic SiC. Semicond. Phys. Quantum Electron. Optoelectron. 18, 403–409 (2015).

Bayraktar, Ş et al. The impact of heat treatment process on the drilling characteristics of Al–5Si–1Cu–Mg alloy produced by sand casting. J. Mater. Res. Technol. 33, 2764–2772 (2024).

Bang, L. T., Ishikawa, K. & Othman, R. Effect of silicon and heat-treatment temperature on the morphology and mechanical properties of silicon-substituted hydroxyapatite. Ceram. Int. 37, 3637–3642 (2011).

Frazer, D., Deck, C. P. & Hosemann, P. High-temperature nanoindentation of SiC/SiC composites. JOM 72, 139–144 (2020).

Grosso, G. & Parravicini, G. P. Solid State Physics (2nd edn) (Academic Press, 2013).

Colinge, J. P. & Colinge, C. A. Physics of Semiconductor Devices (Springer, 2005).

Raja, P. V. & Murty, N. V. L. Thermally annealed gamma irradiated Ni/4H-SiC Schottky barrier diode characteristics. J. Semicond. 40, 022804 (2019).

Kannan, R., Krishnamurthy, S., Kiong, C. C. & Ibrahim, T. B. Impact of gamma-ray irradiation on dynamic characteristics of Si and SiC power MOSFETs. Int. J. Electr. Comput. Eng. 9, 1453–1460 (2019).

Acknowledgements

This research did not receive any specific grant from funding agencies in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

F.S. performed the experiments, analyzed the data, and drafted the manuscript. E.E. supervised the research, guided the study design, and provided overall direction. M.S. advised on data interpretation and critically revised the manuscript. All authors discussed the results and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Soltanifar, F., Ebrahimibasabi, E. & Shahidi, M.M. Thermal recovery of radiation-induced structural and electronic degradation in β-SiC nanopowders. npj Mater Degrad 9, 132 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41529-025-00676-6

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41529-025-00676-6