Abstract

Rapid implementation of Additive Manufacturing (AM) for corrosion-resistant components demands understanding complex process-structure-property relationships without costly characterization. Here we introduce CorrosionOptiMap, a physics-informed process-to-property framework that maps laser powder bed fusion (LPBF) parameters directly to corrosion potential (Ecorr), corrosion rate (CR), and pitting potential (Epitting). Engineered physics descriptors feed Pareto-selected stacking ensembles with an ElasticNet meta-learner, trained on potentiodynamic data from 77 SS316L specimens, the largest experimental LPBF corrosion dataset. CorrosionOptiMap attains R2>0.89 across targets and cuts MAE/RMSE by 50–60% versus raw-parameter models, while SHAP reveals a hierarchy: surface morphology governs CR, porosity and spatters control Epitting, and microstructural homogeneity drives Ecorr. High-throughput “corrosivity maps” evaluate 6,200 parameter combinations and enable multi-objective Pareto optimization, reducing experimental burden 8̃0 × and guiding practical trade-offs. SEM on 35 prints validates surface area driven kinetics for CR. Embedding physics descriptors into ensemble learning yields explainable, scalable predictions that accelerate optimization of corrosion-resistant AM components.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Additive Manufacturing (AM) has transformed industrial production by enabling complex geometries with enhanced design flexibility and reduced material waste. Laser Powder Bed Fusion (LPBF) is the leading AM process for high-precision metallic components due to its accuracy and scalability1. Among metallic alloys, Stainless Steel 316L (SS316L) is widely used in LPBF, especially in aerospace, biomedical and energy sectors, because of its excellent corrosion resistance2. However, LPBF involves rapid solidification and complex thermal histories, creating unique microstructural features such as cellular substructures, residual stresses, and surface defects that significantly impact corrosion behavior3.

Several studies highlight the strong dependence between LPBF-induced microstructural characteristics and electrochemical performance4. Recent studies show large variations in corrosion performance for LPBF-manufactured SS316L5,6. These variations arise from differences in melt pool dynamics and resultant microstructures controlled by LPBF process parameters7. Despite increased interest, quantitative relationships between these parameters and corrosion behavior remain poorly represented. Traditional methods often involve extensive trial-and-error experimentation, hindering efficient optimization8,9.

Corrosion simulation in AM traditionally relies on complex computational models, starting with microstructural evolution simulations that feed into electrochemical models10. This two-step approach is computationally demanding and restricts scalability7,11. Moreover, experimental studies typically focus on limited parameter ranges without predictive capabilities6. Recent advances in Machine Learning (ML) offer promising alternatives, with neural networks and transformer-based architectures achieving remarkable accuracy in predicting melt pool dimensions and mechanical properties12. However, no ML model currently exists that directly correlates LPBF process parameters with corrosion performance.

Wang et al.13 recently demonstrated a physics-informed ML model to predict corrosion in AM alloys. Their work established critical relationships between alloy chemistry and corrosion susceptibility. By systematically varying Cr-Fe-Mn-Ni ratios across 25 alloys, they identified optimal compositional windows that minimize corrosion. Although innovative, their model did not explore the effects of LPBF process parameters, an essential aspect as processing parameters fundamentally dictate the microstructure and surface properties driving corrosion even within optimally designed alloys.

Addressing this critical gap, we introduce CorrosionOptiMap (Fig. 1), the first ML framework directly linking LPBF parameters to corrosion performance metrics. While Wang et al. answered “what to print" through compositional design13, our work addresses “how to print" through process optimization. Our experimental dataset comprising electrochemical corrosion tests from 77 LPBF specimens, the largest to date, spans extensive LPBF parameter ranges. By engineering physics-based descriptors that capture underlying microstructural effects induced by processing rather than composition, we overcome computational complexity, achieving predictive accuracies exceeding 89%. Our framework generates comprehensive “corrosivity maps" visualizing process-property relationships over 6200 parameter combinations, substantially extending beyond experimental limitations. Additionally, we employ multi-objective optimization through Pareto front analysis along with SHAP explainability to tie the model’s behavior to known corrosion mechanisms and actionable AM process choices for decision making.

The key steps in the CorrosionOptiMap framework are (1) Data collection through corrosion testing of 3D-printed specimens, (2) Data preprocessing and exploration, (3) A machine learning pipeline, (4) Model optimization and testing, and (5) Design space generation to explore new material-process combinations.

Addressing this critical gap, we introduce CorrosionOptiMap (Fig. 1), the first ML framework directly linking LPBF parameters to corrosion performance metrics. While Wang et al. answered “what to print" through compositional design13, our work addresses “how to print" through process optimization. Our experimental dataset comprising electrochemical corrosion tests from 77 LPBF specimens, the largest to date, spans extensive LPBF parameter ranges. By engineering physics-based descriptors that capture underlying microstructural effects induced by processing rather than composition, we overcome computational complexity, achieving predictive accuracies exceeding 89%. Our framework generates comprehensive “corrosivity maps" visualizing process-property relationships over 6200 parameter combinations, substantially extending beyond experimental limitations. Additionally, we employ multi-objective optimization through Pareto front analysis along with SHAP explainability to support smart manufacturing decisions.

This study illustrates how ML-driven methods significantly accelerate materials development, reducing months of experimental trials to rapid computations. We hypothesize that physics-informed ML models reliably predict three key corrosion metrics, specifically corrosion potential (Ecorr), Corrosion Rate (CR), and pitting potential (Epitting), directly from LPBF parameters. Our key contributions include (1) a systematic methodology linking LPBF parameters to corrosion behavior; (2) multi-dimensional visualization tools supporting decision-making and industrial integration; (3) systematic multi-objective optimization for complex trade-offs; and (4) SHAP analysis revealing hierarchical parameter influences with morphology validation. These advancements lie at the intersection of AM, ML and materials science disciplines, supporting accelerated scientific discovery and facilitating the industrial integration of AM technologies.

Results and discussion

Physics descriptors enable direct process-to-property mapping

The CorrosionOptiMap framework represents a paradigm shift in predicting corrosion performance of AM components by establishing direct process-to-property relationships without requiring intermediate microstructural characterization. This approach leverages physics-based feature engineering to transform raw LPBF process parameters into physically meaningful descriptors that implicitly capture microstructural effects governing corrosion behavior of AM components.

Initial exploratory data analysis of the augmented dataset revealed that raw LPBF process parameters alone provided limited predictive capability for corrosion performance. Pearson and Spearman correlation analyses (Figs. S23–S28) demonstrated varying, yet limited correlations between LPBF process parameters and corrosion performance metrics. For instance, the investigated LPBF process parameters had absolute Spearman correlations with the target Epitting ranging between 0.12 and 0.23, indicating complex interdependencies between LPBF process parameters and corrosion mechanisms. The highest correlation was moderate (-0.43) between layer height and CR, suggesting increased layer thickness may compromise corrosion resistance by increasing surface roughness, porosity or incomplete fusion between layers.

Process-to-property insights are enabled via engineering physics-based descriptors (detailed in Section III D) that capture fundamental microstructural outcomes governed by LPBF process parameters. The importance of these physics descriptors was initially explored using correlation heatmaps, principal component analysis, and random forest feature importance (Figs. S23–S34). For instance, energy density measures, inculding Volume Energy Density (VED), Surface Energy Density (SED) and Linear Energy Density(LED), exhibited moderate correlations averaging of 0.3 with Ecorr. Meanwhile, hatch spacing and scanning speed had minimal correlations (0.02 and 0.06, respectively) with the same target. For all corrosion metrics, feature importance and principal component analyses revealed that energy density measures have more predictive powers than raw LPBF process parameters. In reality, physics descriptors capture the combined influence of multiple process parameters and material properties on thermal energy input and melt pool dynamics during fabrication14,15. Higher energy densities, for example, typically result in more complete melting and fusion between layers, reducing porosity and creating homogeneous microstructure that minimizes preferential corrosion sites16,17.

The predictive power of physics descriptors was demonstrated through systematic evaluation of 6 regression algorithms, as well as an ElasticNet meta-learner paired with a stacking ensemble of Pareto-optimal models. This explicit ensemble strategy, integrating ElasticNet with diverse Pareto-optimal learners, ensures robust generalization and avoids reliance on a single model. All models were trained twice; (i) once using raw LPBF process parameters only, and (ii) once using LPBF process parameters with engineered physics descriptors. The training, validation, and testing were carried out according to the proposed pipeline (Fig. 2) and optimized using grid search and customized loss functions to nominate a set of Pareto-optimal models for ensembling. The dataset and code have been deposited in an open-access repository and are available at ref. 18.

The key steps in the machine learning pipeline are (1) Experiments: collection of experimental data points, (2) Data preparation: feature selection and local mixing to populate the dataset, (3) Modeling: candidate models, hyperparameter optimization, and Pareto-optimal model generation, and (4) Model deployment: testing and generation of corrosivity maps.

Figure 3 presents the comprehensive training and testing results for tuned models across all three investigated corrosion metrics. Among individual models, optimized CatBoost and GradientBoost algorithms demonstrated better performance across all targets. This performance aligns with established understanding that boosting algorithms excel particularly with smaller datasets. Their iterative architecture focuses on correcting previous prediction errors, enabling efficient utilization of limited training data. The inherent regularization mechanisms and ensemble construction through weak learners effectively reduce both bias and variance. Nevertheless, the limited dataset size inherently constrains the model’s generalization and extrapolation capabilities beyond the studied LPBF parameter ranges.

The stacking ensemble architecture employs ElasticNet as the meta-learner, which differs fundamentally from traditional boosting approaches. Unlike conventional algorithms that sequentially minimize a single loss function, ElasticNet integrates diverse Pareto-optimal base learners within a multi-objective framework. This integration provides superior stability and performance when balancing conflicting optimization objectives. The dual regularization strategy combining L1 and L2 penalties enables ElasticNet to manage collinearity among correlated base learners effectively. Furthermore, the L1 regularization induces sparsity in the model coefficients, enhancing both interpretability and generalization performance. This pipeline enhances generalization capability while preventing overfitting on sparse datasets.

The advantage of encoding physics descriptors becomes evident through quantitative performance metrics. Despite the limited dataset, the incorporation of physics descriptors achieved exceptional predictive accuracy across all corrosion metrics. The integration of these engineered descriptors reduced both Mean Absolute Error (MAE) and Root Mean Squared Error (RMSE) by 50-60% compared to the same models using only raw LPBF process parameters. This substantial error reduction demonstrates that domain knowledge successfully captured the underlying physical phenomena governing corrosion behavior. The improvement in model fitness further validates this claim, where the addition of physics descriptors increased test R2 values for both Ecorr and Epitting, allowing predictive accuracy to exceed 0.89. This enhancement indicates that the engineered physics descriptors effectively capture the variance in corrosion behavior across the parameter space. Most significantly, models’ generalization capability improved dramatically with physics descriptors as the gap between test and validation R2 values decreased to less than 0.1, compared to gaps reaching 0.4 for identical models without physics descriptors. This reduction in generalization error confirms that engineering the right physics descriptors provides robust representations that transfer effectively to unseen parameter combinations.

These quantitative improvements in error metrics, model fitness, and generalization capability provide compelling evidence for the proposed methodology. The synergistic combination of physics descriptors with customized stacking ensembles of Pareto-optimal models establishes a framework that overcomes the traditional limitations of data-driven approaches in corrosion science. This success demonstrates that embedding domain knowledge enables machine learning models to achieve reliable predictions for complex process-property relations even with limited experimental data.

Corrosivity maps: high-throughput predictions of corrosion performance across process space

The distinctive capability of CorrosionOptiMap emerges as a surrogate model capable of rapidly generating predictions across thousands to millions of candidates efficiently. To illustrate the utility of the CorrosionOptiMap framework, a design space was generated for five layer heights (20, 25, 30, 35 and 40 μm) with constraints on LED values to limit excessive extrapolations beyond experimentally explored regions. This approach yielded 6200 viable LPBF parameter combinations from only 77 experimental samples, representing an 80-fold increase in explored parameter space. Subsequently, three corrosion metrics were evaluated across the generated space, producing what we term “corrosivity maps". These comprehensive evaluations were performed on a standard consumer-grade CPU in seconds, demonstrating the computational efficiency and low-time inference of the framework. Furthermore, the model’s interpolation capabilities enable generation of predictions for previously unseen process parameters, such as layer heights of 25 or 35 μm, potentially expanding the accessible parameter combinations by several orders of magnitude beyond the initial 6200 parameter combinations (corrosivity maps for layer height of 25 μm are available in Fig. S36).

The generated corrosivity maps provide a comprehensive visualization of process-to-property relationships across the entire design space, mapping four LPBF process parameters to three corrosion metrics. Fig. 4 presents sample corrosivity map for each target metric. These maps were represented using multidimensional scatter plots at fixed layer heights, enabling the revelation of complex trends that are typically explored individually in literature studies.

CR corrosivity map (Fig. 4a) reveals particularly insightful patterns. At low hatch spacings, diagonal trends emerge where increasing scanning speed requires proportionally higher laser power to maintain comparable corrosion performance. This relationship follows fundamental energy density balance principles governing LPBF process parameter optimization guidelines19,20. However the relationships fade as hatch spacing increases and CR values rise rapidly which is explored further in Section II E). In the case of Ecorr, corrosivity maps (Fig. 4b) reveal that more than half of the explored parameter combinations produced values below -400 mV, indicating suboptimal corrosion resistance. However, specific processing windows achieve superior performance. Optimal conditions yielding enhanced Ecorr values (approximately -300 mV) occurred at 30 μm layer height with laser power exceeding 120 W, scanning speed above 1200 mm/s and small hatch spacing (5-15 μm). This enhanced corrosion resistance stems from the formation of fine cellular/dendritic microstructures and an improved distribution of critical alloying elements, particularly Cr and Mo21.

The generated corrosivity maps allow multi-objective optimization studies across competing corrosion metrics, enabling data-driven refinement of the design space. Practically, using small datasets collected from the existing literature, the approach allows rapid exploration to target high-potential regions of interest within the domain of large design spaces. In this study, the generated dataset was used where Pareto front discovery identified non-dominated solutions for two scenarios: (i) two-objective optimization study (minimize CR, maximize Ecorr) and (ii) three-objective optimization study (minimize CR, maximize Ecorr, maximize Epitting) as illustrated in (Fig. 5). These Pareto-optimal solutions represent combinations of LPBF parameters where one corrosion property cannot be improved without compromising another. For instance, applications requiring maximum corrosion resistance might select parameters from the Pareto front that minimize CR while accepting slightly lower Ecorr values, whereas components requiring balanced performance might choose intermediate solutions. This multi-objective optimization capability transforms conventional trial-and-error methodologies into systematic, data-driven decision making tools. Furthermore, the proposed corrosivity maps can be combined with existing printability maps from the literature to construct multi-dimensional decision spaces. Such integration enables simultaneous optimization of melt pool stability, mechanical properties, and corrosion resistance, thereby guiding more comprehensive process design decisions. The approach may be extended using data sourced from the literature to explore corrosivity metrics across a range of alloys, increasing the model’s input and output dimensionality while preserving high-throughput capabilities with low computational overhead.

Industrial implementation of corrosivity maps

The practical utility of CorrosionOptiMap extends beyond accelerating scientific discovery to providing manufacturers with actionable tools. For example, Pareto fronts offer a spectrum of optimal choices aligned with application requirements. However, engineers often accept suboptimal corrosion performance to balance mechanical properties, build time and dimensional accuracy. The high dimensionality of our corrosivity maps supports industrial tools for such complex trade-offs. For instance, CR corrosivity maps can generate isocorrosion contour plots to delineate processing regions with equivalent corrosion performance (Fig. 6). These contours, similar to isocorrosion diagrams in corrosion engineering, enable flexible parameter selection under manufacturing constraints such as build time and energy consumption. By identifying multiple parameter combinations that yield the same CR value, manufacturers can optimize secondary objectives like production efficiency and mechanical properties without sacrificing corrosion resistance. This comprehensive mapping of process-to-property relationships allows strategic selection of processing conditions that meet specific requirements while minimizing experimental iterations and associated costs. Overall, this approach can accelerate materials development and reduce time-to-market for corrosion-resistant AM components by allowing multi-constraint and multi-objective optimizations.

a Isocorrosion contour map showing laser power vs. scanning speed effects on CR values at fixed layer height (30 μm) and hatch spacing (0.05 mm). The unshaded area represents process parameter combinations filtered using energy density measures. b A typical processing window for LPBF and the locations of common defects.

SHAP analysis reveals hierarchical process-to-property relationships

The application of SHAP analysis transformed the ML predictions into a mechanistic understanding of how LPBF process parameters influence corrosion behavior without requiring explicit microstructural characterizations. This explainable ML approach revealed distinct parameter hierarchies and interaction effects governing each corrosion mechanism. The decision and waterfall plots across all three corrosion parameters (Figs. S39–S44) revealed distinctive pattern shifts and divergences indicating specific parameter combinations that substantially enhance or deteriorate performance.

Ecorr: The SHAP analysis of Ecorr reveals complex relationships (Fig. 7) with SED and Peclet number as the most influential parameters. While high SED values are driven by an increase in laser power and a decrease in scanning speed, higher Pecelt number values are driven by the simultaneous increase of laser power and scanning speed. The positive SHAP values at high SED and Peclet number ranges indicate that for small layer heights, a concurrent increase in laser power and scanning speed generally improves corrosion potential. Compared to SED, positive SHAP values take place on a wider space of high Peclet number values, indicating the need to maximize SED (red) while maintaining high Peclet number (purple-red) to achieve optimal corrosion resistance. This effect is also reflected in strong bimodal patterns observed for SHAP values of melt pool width, melt pool overlap, layer height and laser power. This proposes that optimal Ecorr values occur around high SED with increased scanning speed, layer height, and melt pool overlap. This observation suggests that an optimal melt pool width threshold controls melt pool characteristics, significantly affecting electrochemical nobility and is controlled by the right selection of laser power, scanning speed and layer height; factors present in the SED formula.

Epitting: SHAP summary plot (Fig. 8a) reveals layer height, adiabatic energy efficiency, and scanning speed as the most influential features with the widest range of SHAP values. Optimizing these three factors allows the creation of defect-free smooth surfaces with minimal pitting initiators. Strong bimodal patterns in SHAP values proposes that pitting resistance degrades rapidly with increasing layer height (red) and decreasing scanning speed (blue); conditions where surface defects form, creating active pitting initiation sites22. The rapid increase in Epitting values as layer height decreases (blue) aligns with existing understandings of reduced lack of fusion porosity, increased part density and lowered surface roughness at smaller layer heights23. Similarly, higher adiabatic energy efficiencies (red), which indicates higher energy input per unit volume of the melt pool, increase pitting susceptibility as the melt pool transitions from conduction mode to key-holing leading to X3-5 times the spatter flux and introducing vapor cavities24,25. Spatters in LPBF processes tend to induce rough powder layers, making LPBF printed components prone to porosities and cracks25,26. Aligning this correlation with SHAP analysis, adiabatic energy efficiency maybe used as a thermodynamic “knob” to maximize Epitting as it unifies energy input, melt pool stability, and spatter ejection. Keeping the adiabatic energy efficiency moderate (purple) ensures conduction mode melt pool and minimizes both spatter and as-built roughness. This yields fully dense parts with finer cellular/dendritic formations and improved distribution of passivating elements like Cr and Mo at grain boundaries; A desired microstructure capable of forming stable films that are more resistant to pitting21.

CR: Critical process-to-property relationships, presented in Fig. 9, reveal that surface area exposure primarily drives corrosion kinetics. For CR predictions, all features experience strong bimodal patterns in SHAP values, with the exception of SED, with the most influential features being VED, layer height, and VBR. Lower VED values (blue) dramatically increase CR through positive SHAP contributions. This relationship aligns with findings that insufficient VED leads to lack of fusion defects and interconnected porosity27, creating tortuous pathways that increase surface roughness and the effective surface area exposed to corrosive media. While high VED values (red) moderately reduce corrosion rates, an optimal VED value (purple) with lower layer heights (solid blue) tends to yield the highest negative contribution to CR (10 mpy below the average CR prediction) and produce the most optimal samples. This aligns with common efforts proposing that an optimal moderate VED value yields the densest parts with reduced surface roughness and minimal porosity6,20. The optimal range of VED values is known to yield microstructural uniformity, minimizing preferential sites for localized corrosion attacks16.

Layer height exhibits the second-strongest SHAP importance with a clear monotonic relationship where higher layer heights (red) consistently yield positive SHAP values, indicating accelerated corrosion. Comparing the corrosivity maps across varying layer heights (Figs. S35–S38) reveals that increasing layer height from 20 μm to 40 μm progressively amplifies CR, particularly at mid-range hatch spacings (100–200 μm). In addition, optimal processing windows represented by diagonal patterns with lower CR values narrowed down as the layer height increases; confirming a relation examined in detail by Hyer et al.23. This performance deterioration occurs because thicker layers require greater energy input to achieve complete melting, and when insufficient, result in coarser surface texture driven by incomplete melting of powder particles, increased porosity and spatters27.

When low VED values are accompanied by large layer heights, the CR values increase by around 7 mpy, indicating a large increase in surface defects and roughness that doubles CR values. VBR displays predominantly positive SHAP contributions at higher values, suggesting that faster processing speeds driven mainly by thicker layers (red) and larger hatch spacings (red) contribute the most to increased CR (13 mpy above average CR prediction). This relationship provides an understanding that higher VBR often results in unmolten tracks between laser scans (evident in the very wide range for SHAP values at high hatch spacings), increasing the effective area exposed to the corrosive medium; a relation further investigated and validated in Section II E and found to introduce lattice structures that substantially increase effective surface area. This observation is not common in existing corrosion literature due to the focus on investigating spaces with desired LPBF parameters and solid AM parts28,29. However, it is very meaningful in biomedical applications where porous lattice structures with tailored surface roughness are desired to promote cell adhesion and proliferation for implants30,31. This ability to explore large parameter spaces and deduce multiscale complex process-to-property relations using a surrogate model with a limited dataset indicates the efficacy of the proposed approach in data-driven scientific discovery.

These insights outline a clear hierarchy that stretches from the melt pool microstructure to surface features such as spatters and lattice geometries. At the microstructural level, Ecorr is chiefly dictated by the electrochemical nobility conferred by a homogeneous phase distribution. In contrast, the Epitting is governed more by pitting initiators (pores, spatters, and cracks). The overall CR hinges on the effective surface area exposed to the electrolyte, rising with increased roughness and surface defects, and becoming even more pronounced in process-induced lattice structures. This tiered dependence underscores the need for high-throughput predictive models that can navigate large LPBF parameter spaces and enable sophisticated trade-offs between microstructure, defect population, and surface morphology. Incorporating physics descriptors was proven advantageous in capturing key process-to-property relationships while introducing beneficial redundancy for model robustness. Future work could develop tailored physics descriptors using dimensional analysis to account for diverse corrosive environments with varying temperatures, salts, and CO2 levels.

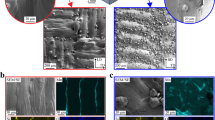

Experimental validation confirms surface morphology as primary driver of corrosion rate

CR corrosivity map (Fig. 4a) indicates that increasing the hatch spacing yields excessively high CR values regardless of varying the laser power and scanning speed values. Thus, Scanning Electron Microscopy (SEM) analysis of 35 specimens with 20 μm layer height provided direct visual evidence validating the ML predictions and supporting mechanistic interpretations made earlier based on SHAP analysis. The systematic examination of surface morphology across varying hatch distances and energy densities revealed that effective surface area exposed to the corrosive medium is the primary driver of CR variations in LPBF-manufactured SS316L.

Samples fabricated with optimal parameters (identified as purple scatters in Fig. 4a and highlighted red regions in Fig. 10) exhibited remarkably smooth surfaces with minimal defects, corresponding to the lowest measured corrosion rates (CR < 10 mpy). These conditions promoted complete powder melting with appropriate overlap between adjacent tracks, creating homogeneous microstructure with minimal surface defects and reduced surface roughness. In contrast, samples produced with wider hatch spacing (orange regions in Fig. 10) displayed pronounced unmolten tracks with visible exposure of underlying layers, substantially increasing the effective surface area. This increased surface area accelerates electrochemical reactions by providing additional sites for corrosion initiation and propagation. Similarly, samples fabricated with excessive energy density (purple regions in Fig. 10)) showed pronounced topographical variations due to excessive melting, while those produced with insufficient energy densities (black regions in Fig. 10)) demonstrated melt track irregularities and surface pores.

Overall, SEM evidence points to a multiscale hierarchy controlling CR: small CR shifts (≤5 mpy) stem from melt pool microstructural refinements; moderate changes (~5−15 mpy) are governed by mesoscale surface roughness and porosity; and the largest increments (>15 mpy) are introduced by process-induced macroscale lattice structures that amplify the surface area exposed to the corrosive medium. These variations in CR from 5 to 45 mpy can be used to distinguish between acceptable and catastrophic performance at the component level, thus underscoring the direct link between LPBF process parameters and part failure due to corrosion. This stratification also enables engineers to meet diverse design requirements such as retaining a desired lattice for certain weight reduction or biocompatibility requirements while still optimizing microstructure and surface defect populations to achieve desired corrosion performance targets across multiple length scales.

In summary, this study successfully addressed the critical challenge of predicting and optimizing corrosion performance in LPBF-manufactured SS316L components through the development of CorrosionOptiMap, a novel framework that establishes direct process-to-property relationships without requiring intermediate microstructural characterization. The research integrated experimental fabrication of 77 specimens across diverse LPBF parameter combinations, comprehensive electrochemical testing in brine solution, physics descriptors, and advanced machine learning implementation to design an impactful approach for corrosion-resistant component design. The key findings demonstrate that energy density measures consistently influenced corrosion resistance across all metrics, while distinct parameter hierarchies emerged for different corrosion mechanisms. The resulting multi-dimensional corrosivity maps enabled successful multi-objective optimization through Pareto front discovery. This offers a spectrum of parameter combinations that balance competing corrosion metrics based on application-specific requirements. The paradigm shift introduced by CorrosionOptiMap extends beyond immediate practical applications. By demonstrating that corrosion performance can be reliably predicted directly from process parameters without expensive microstructural characterization, this work establishes a new framework for accelerated materials development in corrosion of AM parts. This approach not only reduces development time and costs but also provides mechanistic insights that advance fundamental understanding of process-structure-property relationships in metal AM.

Methods

Materials

This study used EOS SS316L powder with particle size up to 63 μm as feedstock material, with its nominal chemical composition presented in Table 1. SS316L was specifically selected due to its excellent corrosion resistance in harsh environments, making it particularly suitable for energy sector applications where components are exposed to aggressive chemicals2. A simulated brine solution served as the electrolyte for corrosion testing, with salt concentrations detailed in Table 2. This ionic composition was formulated to simulate the challenging conditions typically encountered in oil and gas reservoir environments, providing a realistic assessment of material performance under service conditions32.

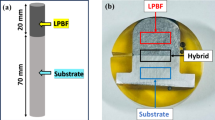

Specimen preparation via LPBF

All samples were manufactured using an EOS M100 LPBF system with SS316L powder as feedstock. The comprehensive study produced 77 cylindrical specimens measuring 14 mm in diameter and 5 mm in height across multiple print trials, with each trial containing between 8 and 12 samples. Among these specimens, 32 were fabricated using recommended LPBF parameters derived from literature to establish baseline performance, while the remaining 45 samples were deliberately produced with parameters designed to induce defects. This dual approach enabled systematic quantification of the effects of the induced defects on corrosion performance while providing good predictability in the defect-free region. This study systematically varied four key LPBF process parameters (layer thickness, hatch distance, laser power, and laser scanning speed) to investigate their effects on corrosion behavior.

To ensure comprehensive parameter space exploration, each specimen was assigned unique LPBF parameter combinations during fabrication. Throughout the printing process, samples were built on a DirectBase S15 platform while maintaining a protective argon atmosphere in the build chamber. The scanning strategy employed a single laser beam with 67∘ rotation between successive layers, which effectively minimized residual stress accumulation. Additionally, laser scanning proceeded against the argon flow direction, a technique that reduced spatter contamination on the powder bed. Following completion of the printing process, wire electrical discharge machining was used to carefully remove samples from the build platform while preserving their as-printed surface characteristics.

Electrochemical testing and data collection

Electrochemical characterization was performed using a Gamry Interface 1010E potentiostat equipped with a multiport corrosion jacketed cell. All tests were conducted at room temperature using a three-electrode configuration, where a saturated calomel electrode served as reference along with a graphite counter electrode. A standard sample holder was employed to expose 1 cm2 of specimen surface to the test electrolyte. Importantly, all electrochemical tests were conducted on the top surface of as-printed specimens without any polishing, as this approach evaluated realistic service conditions in which surface roughness and microstructural features characteristic of LPBF parts significantly influence their electrochemical responses.

Prior to polarization measurements, each test commenced with a cathodic cleaning step at −1.0 V vs SCE to remove surface oxides while simultaneously stabilizing the baseline current. Immediately after this potentiostatic hold, potentiodynamic polarization (PDP) scans were initiated from −1.0 V to 1.5 V vs SCE, employing a scan rate of 2 mV/s with data sampling at 2 Hz frequency. This scanning protocol provided a comprehensive characterization of both anodic and cathodic behavior across a wide range of potentials.

From each polarization curve, three critical parameters were extracted to characterize the corrosion behavior comprehensively (Fig. 11). The corrosion potential (Ecorr) indicated the thermodynamic tendency for corrosion initiation, while the corrosion current (Icorr) quantified the kinetic rate of metal dissolution. Additionally, the pitting potential (Epitting) provided a measure of resistance to localized attack. The Tafel extrapolation method was applied to determine Icorr values, which were subsequently converted to Corrosion Rates (CR) expressed in mils per year (mpy) following ASTM G102 using the equation:

where Icorr is in μA/cm2, EW is the equivalent weight of the alloy (g/equivalent), and ρ is the density (g/cm3). This conversion provides the annual corrosion rate expressed in mpy33. These electrochemical parameters ultimately served as target variables for the ML model development, providing a comprehensive assessment of corrosion performance across the investigated LPBF parameter space.

Machine learning framework

ML has emerged as a transformative tool in materials science, offering data-driven models that serve as cheap and accurate simulation alternatives to costly experiments34. These computational approaches enable rapid exploration of vast parameter spaces while providing actionable insights for materials optimization and science discoveries35. In the context of AM, there is a need for ML frameworks that can accelerate the development of process-property relationships without requiring extensive experimental campaigns or computationally expensive simulations8.

Simulating corrosion in AM components traditionally requires a multi-step approach: first modeling microstructural evolution during LPBF processing, then feeding these microstructures into electrochemical models to simulate redox reactions. This multi-step computational workflow is complex, resource-intensive, and prone to compounding uncertainties, ultimately limiting the scalability of dataset generation7,11. Meanwhile, experimental studies correlating LPBF parameters to corrosion typically investigate only limited sets of LPBF processing parameters without employing predictive modeling tools6. Our framework bridges these gaps by establishing direct ML-based links from LPBF process parameters to corrosion performance metrics. This approach bypasses the need for computational microstructure simulation, offering an experimental dataset and a streamlined alternative to traditional methods.

By feeding physics descriptors as engineered features, our models implicitly capture the major microstructural effects shaping corrosion behavior. We demonstrate that corrosion performance can be reliably predicted directly from process inputs, eliminating the need for intermediate characterization steps. By breaking down traditional disciplinary barriers, this work provides a template for developing streamlined process-to-property models that accelerate materials development while reducing experimental burden. Figure 2 summarizes the proposed workflow that transforms raw LPBF parameters into a high-throughput, explainable process-to-property surrogate capable of predicting corrosion properties without the need for microstructural characterization.

Engineering physics descriptors

During the ML training phase, selecting appropriate features is crucial for reliable prediction performance. Initial exploratory data analysis examined statistical properties, feature distributions, and relationships between input features and target variables. This analysis revealed that raw process parameters alone provided limited predictive capability, necessitating feature engineering to transform these parameters into physically meaningful quantities. To develop a well-trained ML surrogate, sufficient features needed to be identified due to the complexity of the physical phenomena involved in LPBF and its effects on process-induced surface features and microstructure that drive corrosion performance. By leveraging established relationships, the selected LPBF process parameters were used to engineer the following physics descriptors:

Energy density measures: These integrated metrics capture the combined influence of multiple process parameters on thermal energy input during fabrication. Using such measures as input features helps establish stronger correlations with microstructural development and resulting corrosion properties than individual parameters alone, enhancing predictive model performance. The most common density measures are15,36:

where VED is the volume energy density [J/mm3], SED is the surface energy density [J/mm2], LED is the Linear Energy Density [J/mm], P is the laser power [W], V is the laser scanning speed [mm/s], H is the hatch spacing [mm], and L is the powder layer thickness [mm].

Higher energy densities typically result in more complete melting and fusion between layers, reducing porosity and creating more homogeneous microstructures36. This microstructural uniformity directly influences corrosion performance by minimizing preferential sites for localized corrosion attack such as pores, lack of fusion defects, and microstructural heterogeneities16. However, excessive energy input can lead to increased residual stress, coarser grain structures, and surface oxidation, all of which can detrimentally affect corrosion resistance by creating electrochemical potential differences within the material37.

Volumetric build rate: This parameter quantifies manufacturing efficiency by measuring the volume of material processed per unit time, providing insights into production throughput capabilities of the LPBF process. In relation to corrosion behavior, this parameter significantly influences microstructural evolution through its direct effect on cooling rates and thermal gradients during fabrication. The volumetric build rate, VBR, can be calculated in [mm3/s] using38:

Higher VBR values indicate faster processing speeds that result in steeper thermal gradients and rapid solidification rates, promoting finer grain structures38. These microstructural features can enhance corrosion resistance by creating more uniform passive film formation and reducing susceptibility to galvanic microcells within the material39. Conversely, excessively high build rates may lead to insufficient melting, increased porosity, and unmelted powder inclusions, creating crevices and sites for localized corrosion initiation that can substantially reduce pitting resistance in aggressive environments22.

Normalized enthalpy: This dimensionless parameter represents the ratio of absorbed energy to the energy required for melting, characterizing the thermal conditions during laser-material interaction in LPBF processes. This thermodynamic metric effectively predicts melt pool dynamics and solidification behavior, thereby establishing direct correlations with resulting microstructural features and melt pool dimensions40.

where \(\overline{\Delta H}\) is the normalized enthalpy [dimensionless], α is the absorptivity of the bulk material (0.6 for SS316L powder41), ρ is the density (7900 kg/m3 for SS316L), C is the specific heat (490 J/(kg ⋅ K) for SS316L), ΔT is the difference between melting and powder bed temperatures (1300 K in this study), Lm is the latent heat of melting (260 kJ/kg for SS316L35), r is the laser spot radius (20 μm for EOS M10042) and D is the thermal diffusivity (3.5 × 10−6m2/s for SS316L).

The normalized enthalpy directly influences melt pool stability and morphology, which in turn affects surface roughness, oxide formation, and compositional homogeneity of the printed parts16. Optimal normalized enthalpy values produce stable melt pools with consistent solidification patterns, resulting in uniform elemental distribution and reduced microsegregation at grain boundaries43,44. These characteristics are particularly important for corrosion performance of stainless steels, as they minimize chromium-depleted zones that are susceptible to preferential corrosion attacks, thereby enhancing passive film stability and increasing pitting resistance in chloride-rich environments21.

Melt pool width and overlapping: These parameters characterize the geometric relationship between adjacent melt tracks and significantly influence the formation of lack of fusion tracks in the LPBF process. Melt pool width (Wmelt) can be estimated using a dimensionless equation derived from experimental data and fitted using symbolic regression35:

where k is the thermal conductivity [W/(m ⋅ K)]. The overlap between adjacent melt tracks can be quantified as follows:

Positive overlap values indicate overlaps between adjacent melt pools, while negative values denote gaps between adjacent melt tracks (Fig. 12). Sufficient overlapping is crucial for achieving dense parts as it ensures complete fusion between adjacent tracks and minimized surface roughness45. Insufficient overlapping creates unfused regions between adjacent tracks, increasing the effective surface area exposed to the corrosive environment, thus, compromising mechanical properties and corrosion resistance28. Therefore, optimizing the relationship between melt pool width and hatch spacing represents a critical balance for achieving high-quality fabricated parts with good corrosion performance.

Adiabatic energy efficiency: This dimensionless parameter quantifies the efficiency of laser energy utilization in creating the melt pool volume, considering the geometric relationship between melt pool dimensions and energy input. This metric provides insights into the thermal efficiency of the LPBF process and helps identify optimal energy utilization conditions46:

where ηadiabatic is the adiabatic energy efficiency [dimensionless]. Higher efficiency values indicate better utilization of laser energy for melt pool formation, typically corresponding to more stable processing conditions with reduced spatter formation and improved surface quality. Optimal energy efficiency promotes uniform microstructural development and consistent passive layer formation, enhancing corrosion resistance by minimizing surface irregularities and compositional heterogeneities that can serve as corrosion initiation sites46,47.

Melt pool depth: This parameter characterizes the penetration depth of the laser into the powder bed and substrate material, directly influencing layer bonding and defect formation. Melt pool depth significantly affects interlayer adhesion and the formation of lack-of-fusion defects between successive layers45. The depth of melt pools forming with conduction mode can be estimated using48:

where Dmelt is the estimated melt pool depth [μm], and A is the absorptivity. Excessive melt pool depth can cause keyhole formation and entrapment of process gases, both conditions that negatively impact corrosion resistance by creating preferential attack sites28. When laser power is high and scan speed is low, the resulting high energy density tracks generate strong Marangoni and recoil-jet forces that push the melt pool flow from laminar circulation into a turbulent regime49.

Peclet number: This dimensionless parameter characterizes the relative importance of convective heat transport to diffusive heat transport during the LPBF process, providing critical insights into thermal transport mechanisms and solidification behavior50:

where Pe is the Peclet number [dimensionless]. The Peclet number governs thermal gradients and cooling rates during solidification, directly influencing grain morphology and cellular/dendritic spacing. Lower Peclet numbers favor equiaxed grain formation and finer microstructures, while higher values promote columnar grain growth and coarser cellular structures51.

Data augmentation and preprocessing

The experimental dataset from PDP testing consisted of 77 samples, compiled into a structured dataset containing 4 LPBF process parameters alongside the target corrosion performance metrics (Ecorr, CR, Epitting). In addition to the base input parameters, 10 physics descriptors were engineered to incorporate domain knowledge of process-structure interactions. Accordingly, data may be represented as:

Input branch A: raw LPBF process parameters only

Input branch B: input branch A + 10 physics descriptors

Targets: three selected corrosion performance metrics

To address the dataset’s limited size, data augmentation was implemented using local mixup technique, effectively tripling the dataset52:

where Xaug and Yaug represent the augmented features and targets, Xorig and Yorig are the input branch B features and target features, Xnn and Ynn are the corresponding values from the k-nearest neighbor (k=3 & 5), and λ ~ Beta(α, α) with α = 0.1 is the mixing coefficient that controls the interpolation between samples. These values were selected to ensure that virtual samples are generated as structured perturbations around original points rather than arbitrary interpolations. Following this, all features and target variables underwent RobustScaler standardization to ensure uniform scaling during model development and deployment. Both input branches passed through identical preprocessing steps to ensure fair model comparisons.

Model architecture and training protocols

This framework demonstrates that direct process-to-property predictions are both feasible and impactful, bypassing computationally expensive intermediate steps. Our framework complements traditional experimental work while significantly reducing computational burden. The following regression models were trained as candidate models:

ElasticNet: combines L1 (Lasso) and L2 (Ridge) regularization penalties to achieve both feature selection and coefficient shrinkage, making it particularly effective for high-dimensional datasets with correlated features53. The method balances the sparsity-inducing properties of Lasso with the grouping effect of Ridge regression. This allows simultaneous selection of groups of correlated features. This characteristic makes ElasticNet well-suited for materials science applications where process parameters often exhibit strong intercorrelations.

Gradient Boosting: builds an ensemble of weak learners sequentially, where each new model corrects residual errors of the previous ensemble54. The algorithm minimizes a loss function through gradient descent in function space. This results in a strong predictor that captures complex non-linear relationships and the ability to automatically perform feature selection, making it valuable for process-to-property modeling in AM.

CatBoost: an advanced gradient boosting algorithm designed to handle categorical features effectively while reducing overfitting55. The algorithm uses novel techniques such as ordered boosting and feature combinations.Its ability to automatically handle feature interactions makes it suitable for capturing hierarchical interdependencies between LPBF process parameters.

AdaBoost: iteratively adjusts the weights of training samples, focusing on previously poorly predicted instances56. Each weak learner is trained on a reweighted version of the training set, emphasizing difficult-to-predict samples. This adaptive mechanism makes AdaBoost effective at identifying and learning from outliers or unusual LPBF parameter combinations.

Huber Regressor: employs the Huber loss function, which combines squared loss for small errors and absolute loss for large errors57. This provides robustness against outliers. This characteristic is particularly valuable in experimental datasets where underrepresented classes may introduce outliers. The method ensures that model predictions remain stable when trained on datasets containing anomalous observations.

NGBoost: extends traditional boosting to predict entire probability distributions rather than point estimates58. The method uses natural gradients to optimize over probability distributions to capture of both epistemic and aleatoric uncertainties in predictions.

The augmented dataset was partitioned using an 85/15 training-testing split. 5-fold cross-validation was applied to the training portion to ensure robust model performance assessment. Hyperparameter optimization was conducted for each model using Grid Search (tuning settings detailed in Table S2). Performance was evaluated using coefficient of determination (R2), Mean Absolute Error (MAE), and Root Mean Squared Error (RMSE):

where yi represents actual values, fθ(xi) represents model predictions, \(\bar{y}\) is the mean of actual values, and n is the number of samples.

For each candidate model, 5-fold cross-validation was performed to obtain comprehensive performance metrics. These track both predictive accuracy and generalization capability. Generalization gaps were quantified as Gap = ∣Metrictrain − Metricval∣. The Pareto-optimal set \({\mathcal{P}}\) was identified using a multi-objective dominance rule considering five criteria. Model A dominates model B if A performs better than or equal to B on all objectives. The minimized objectives are MSEval, RMSEval, MSEgap, RMSEgap, and ∣RMSEval − MAEval∣. The maximization objective is \({R}_{val}^{2}\), with at least one strict improvement required. This approach ensures selection of models that balance predictive accuracy, generalization capability, and consistency across error metrics.

The ensemble framework implements a two-stage approach combining parameter diversity and stacking. For each candidate model, 5 Pareto-optimal model configurations were selected. Each configuration was used to train a separate model instance on the training dataset. This creates a diverse ensemble for each model type. Out-of-fold predictions were generated by averaging predictions from all ensemble members within each model type. The stacking architecture employs these averaged out-of-fold predictions as training features for an ElasticNet meta-model. Test features were computed as mean predictions across ensemble members. This approach leverages diversity introduced by different Pareto-optimal configurations and complementary strengths of different algorithms. The meta-model learns optimal combinations of ensemble predictions, enhancing generalization performance despite limited data size.

The stacking regressor architecture can be described as:

where z = [z1, z2, . . . , zK] are the out-of-fold predictions from K Pareto-optimal models, and fmeta is the meta-learner. Predictions are generated using cross-validation to prevent overfitting:

where \({f}_{k}^{(-fold(i))}\) represents the k-th Pareto-optimal model trained on all folds except the one containing sample i. Performance metrics were evaluated for the meta-learner using the same approach implemented for candidate models.

Design space generation and multi-objective optimization

To explore the design space for LPBF process parameters, a full factorial design generated all possible parameter combinations within the studied LPBF parameter space using discrete parameter ranges. These combinations were filtered according to the LED values in the dataset to avoid excessive extrapolations beyond model-validated regions, resulting in 6200 viable LPBF parameter combinations. This refined design space represents feasible experiments with three stacking ensembles applied to predict the target variables (Ecorr, CR, Epitting). To facilitate interpretation of the relationships between LPBF process parameters and corrosion performance, 3D scatter plots were generated for selected layer heights. These visualizations, termed “corrosivity maps", provide comprehensive insights into how different LPBF parameter combinations influence corrosion behavior.

A multi-objective optimization approach was implemented to identify optimal LPBF parameter combinations through Pareto front discovery, balancing the trade-offs between competing corrosion performance metrics. The multi-objective optimization problem is formulated as:

subject to:

where x is the vector of LPBF process parameters, F(x) is the vector of objective functions (selected corrosion metrics), g(x) and h(x) are inequality and equality constraints, and xL, xU are the lower and upper bounds on process parameters. A solution x is said to be Pareto-dominated by another solution x* if and only if fi(x)≤fi(x*) for all i ∈ {1, 2, 3} with at least one strict inequality. The set of all Pareto optimal solutions forms the Pareto front, representing the optimal trade-offs between competing corrosion metrics.

Model interpretability and SHAP analysis

The final component of our high-throughput process-to-property framework involves translating ML predictions into physical understanding of corrosion mechanisms without the need to assess the microstructure of the produced specimens. This approach represents a significant advancement over traditional process-structure-property mapping methodologies. Interpretability, understanding the rationale behind a model’s predictions, is critical in relating LPBF process parameters and corrosion performance through ML models59. To address this, SHapley Additive exPlanations (SHAP) was applied as an explainable AI technique which uses a game-theoretic approach to explain model outputs, attributing the contribution of each feature to the final prediction in a human-comprehensible way60. SHAP assigns a unique Shapley value to each feature for every prediction, quantifying the average marginal contribution of that feature’s value across all possible combinations of features. The SHAP value ϕi for feature i is defined as:

where N is the set of all features, S is a subset of features not including feature i, and f(S) is the model prediction using only features in subset S.

For each target variable, SHAP analysis was performed on the stacking ensemble using the generated parameter space. This methodology enables intuitive explanations for specific predictions, independent of the ML model’s complexity. To gain deeper insights, various SHAP plots are employed to examine how individual features influence predictions across different observations, offering a comprehensive understanding of model behavior at both global (overall trends) and local (individual prediction) levels. These analyses provide insights into the relative importance of input features and understand the model’s decision-making process, enhancing interpretability and making the trained model a valuable tool for predictive tasks. By correlating SHAP values with known physical mechanisms, our framework establishes direct links between LPBF process parameters and corrosion behavior, effectively bypassing traditional microstructural characterization requirements.

Surface morphology validation

Surface morphology was examined using SEM on all specimens with a layer thickness of 20 μm, totaling 35 samples, to verify CR conclusions and support the interpretation of corrosivity maps. These post-corrosion analyses were conducted using a Thermo-Fisher Lumis SEM operated with a T2 detector and a metal-oxide semiconductor sensor. The SEM was operated with “Standard" use case at 2.0 kV, 25 pA, and varying magnifications.

The samples were analyzed on the basis of varying hatch distances and energy densities to investigate the relationship between LPBF process parameters, resulting surface features and corrosion performance. Special attention was given to identifying unmolten tracks, balling phenomenon, insufficient melting, and other surface irregularities that potentially increase the effective surface area exposed to the corrosive environment. This analysis provided direct visual evidence for correlating surface morphology with the observed variations in CR values across the generated design space, supporting the insights derived from SHAP analysis and validating the process-to-property mapping.

Data availability

The data that support the findings of this study are available in the supplementary material of this article. All code, trained weights, and raw data are openly available under a CC-BY license at 18, reproducing all results and figures in this article.

References

Bakhtari, A. R. et al. A review on laser beam shaping application in laser-powder bed fusion. Adv. Eng. Mater. 26, 2302013 (2024).

Lodhi, M., Deen, K. & Haider, W. Corrosion behavior of additively manufactured 316l stainless steel in acidic media. Materialia 2, 111–121 (2018).

Zhang, R. et al. Mechanical properties and microstructure of additively manufactured stainless steel with laser welded joints. Mater. Des. 208, 109921 (2021).

Hemmasian Ettefagh, A., Guo, S. & Raush, J. Corrosion performance of additively manufactured stainless steel parts: a review. Addit. Manuf. 37, 101689 (2021).

Puga, B. et al. Influence of laser powder bed fusion processing parameters on corrosion behaviour of 316l stainless steel in nitric acid. Metall. Res. Technol. 119, 523 (2022).

Alabtah, F. G. et al. Advancing the industrial utilization of additive manufacturing: Understanding early-stage corrosion dynamics through advanced electrochemical and microstructural characterization. J. Mater. Res. Technol. 35, 2525–2546 (2025).

Moazzen, P. et al. Optimum corrosion performance using microstructure design and additive manufacturing process control. npj Mater. Degrad. 9, 10 (2025).

Hu, Z. & Yan, W. Data-driven modeling of process-structure-property relationships in metal additive manufacturing. npj Adv. Manuf. 1, 3 (2024).

Villabona, E., Veiga, F., Rivero, P. J., Uralde, V. & Suárez, A. Corrosion behavior of additively manufactured steels: a comprehensive review. Steel Res. Int. 96, 51–79 (2025).

Brewick, P. Simulating pitting corrosion in am 316l microstructures through phase field methods and computational modeling. J. Electrochem. Soc. 169 (2022).

Zhi, H. et al. Phase field study of pitting corrosion: electrochemical reactions and temperature dependence. Comput. Mater. Sci. 244, 113251 (2024).

Akbari, P., Zamani, M. & Mostafaei, A. Machine learning prediction of mechanical properties in metal additive manufacturing. Addit. Manuf. 91, 104320 (2024).

Wang, Y. et al. Integrated high-throughput and machine learning methods to accelerate discovery of molten salt corrosion-resistant alloys. Adv. Sci. 9, 2200370 (2022).

Buhairi, M. A. et al. Review on volumetric energy density: influence on morphology and mechanical properties of Ti6Al4V manufactured via laser powder bed fusion. Prog. Addit. Manuf. 8, 265–283 (2023).

Deng, Q. et al. Limitations of linear energy density for laser powder bed fusion of Mg-15Gd-1Zn-0.4Zr alloy. Mater. Charact. 190, 112071 (2022).

Vukkum, V. B. & Gupta, R. K. Review on corrosion performance of laser powder-bed fusion printed 316l stainless steel: Effect of processing parameters, manufacturing defects, post-processing, feedstock, and microstructure. Mater. Des. 221, 110874 (2022).

Perumal, G. et al. Exploring the role of volume energy density in altering microstructure and corrosion behavior of nitinol alloys produced by laser powder bed fusion. Sci. Rep. 15, 2055 (2025).

Karaki, A., Hammoud, A., Alabtah, F. G., AbdelGawad, M. & Khraisheh, M. CorrosionOptiMap links additive manufacturing process parameters to corrosion of stainless steel. Zenodo https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.17338728 (2025).

Ni, C. et al. Recent advance in laser powder bed fusion of Ti–6Al–4V alloys: microstructure, mechanical properties and machinability. Virtual Phys. Prototyping 20 (2025).

Wang, Z., Xiao, Z., Tse, Y., Huang, C. & Zhang, W. Optimization of processing parameters and establishment of a relationship between microstructure and mechanical properties of SLM titanium alloy. Opt. Laser Technol. 112, 159–167 (2019).

Zhao, C., Bai, Y., Yan, Q. & Li, B. Enhanced corrosion resistance of laser powder bed fusion 316L stainless steel by modifying the microstructure through heat treatment. J. Mater. Res. Technol. 36, 7158-7171 (2025).

Voisin, T. et al. Pitting corrosion in 316L stainless steel fabricated by laser powder bed fusion additive manufacturing: a review and perspective. JOM 74, 1668–1689 (2022).

Hyer, H. C. & Petrie, C. M. Effect of powder layer thickness on the microstructural development of additively manufactured SS316. J. Manuf. Process. 76, 666–674 (2022).

He, X. et al. The kinetics of pitting corrosion in a defect-contained Hastelloy X alloy fabricated by laser powder bed fusion. Corros. Sci. 237, 112321 (2024).

Li, Z. et al. A review of spatter in laser powder bed fusion additive manufacturing: In situ detection, generation, effects, and countermeasures. Micromachines 13 https://www.mdpi.com/2072-666X/13/8/1366 (2022).

Zhang, H., Vallabh, C. K. P. & Zhao, X. Influence of spattering on in-process layer surface roughness during laser powder bed fusion. J. Manuf. Process. 104, 289–306 (2023).

Levkulich, N. et al. The effect of process parameters on residual stress evolution and distortion in the laser powder bed fusion of Ti-6Al-4V. Addit. Manuf. 28, 475–484 (2019).

García-Rodríguez, S., Bedmar, J., Abu-warda, N., Torres, B. & Rams, J. Microstructure and corrosion behavior of 316L stainless steel lattice and bulk parts manufactured by LPBF using fiber and CO2 lasers. Mater. Des. 244, 113214 (2024).

Puttonen, T. et al. Influence of feature size and shape on corrosion of 316L lattice structures fabricated by laser powder bed fusion. Addit. Manuf. 61, 103288 (2023).

Tyagi, S. A. & M, M. Additive manufacturing of titanium-based lattice structures for medical applications - a review. Bioprinting 30, e00267 (2023).

GÜRKAN, D. and Sagbas, B. “Additively manufactured Ti6Al4V lattice structures for biomedical applications,” Int. J. 3D Printing Technol. Digit. Industry. 5, 07 (2021).

Ansari, N., Alabtah, F. G. & Khraisheh, M. Influence of temperature on corrosion behavior of additively manufactured SS316L stainless steel in Co2-saturated brine solution. Mater. Lett. 376, 137272 (2024).

Electrochemical techniques for corrosion measurement. Tech. Rep., Gamry Instruments, Warminster, PA, USA https://www.gamry.com/assets/Uploads/Echem-Corrosion-Measurement.pdf (2019).

DebRoy, T., Mukherjee, T., Wei, H. L., Elmer, J. W. & Milewski, J. O. Metallurgy, mechanistic models and machine learning in metal printing. Nat. Rev. Mater. 6, 48–68 (2021).

Akbari, P. et al. Meltpoolnet: Melt pool characteristic prediction in metal additive manufacturing using machine learning. Addit. Manuf. 55, 102817 (2022).

Kurzynowski, T. et al. Effect of scanning and support strategies on relative density of SLM-ed H13 steel in relation to specimen size. Materials 12, 239 (2019).

Yousif, M. A. S., Al-Deheish, I. A., Ali, U., Akhtar, S. S. & Al-Athel, K. S. Mechanical, tribological, and corrosion behavior of laser powder-bed fusion 316L stainless steel parts: Effect of build orientation. J. Mater. Res. Technol. 33, 1220–1233 (2024).

Schwerz, C., Schulz, F., Natesan, E. & Nyborg, L. Increasing productivity of laser powder bed fusion manufactured Hastelloy X through modification of process parameters. J. Manuf. Process. 78, 231–241 (2022).

Liang, J. et al. Study on corrosion characteristics and mechanism of laser powder bed fusion of mg–zn–zr alloy. J. Mater. Res. Technol. 30, 6366–6375 (2024).

Weaver, J. S., Heigel, J. C. & Lane, B. M. Laser spot size and scaling laws for laser beam additive manufacturing. J. Manuf. Process. 73, 26–39 (2022).

King, W. E. et al. Laser powder bed fusion additive manufacturing of metals; physics, computational, and materials challenges. Appl. Phys. Rev. 2, 041304 (2015).

Eos Positioning Systems. EOS Arrow Gold+ GNSS Receiver Technical Specifications. Eos Positioning Systems (2025). https://www.digital-can.com/wp-content/uploads/EOS-M100_EN.pdf. Accessed: May 5, 2025.

Ghasemi-Tabasi, H. et al. An effective rule for translating optimal selective laser melting processing parameters from one material to another. Addit. Manuf. 36, 101496 (2020).

Zhou, Y. et al. The processing map of laser powder bed fusion in-situ alloying for controlling the composition inhomogeneity of AlCu alloy. Metals 13, 97 (2023).

Dong, A. et al. Overlap ratio and scanning strategy effects on laser powder bed fusion Ti6Al4V: numerical thermal modeling and experiments. Int. J. Adv. Manuf. Technol. 125, 3053–3067 (2023).

Yang, Y. et al. Validated dimensionless scaling law for melt pool width in laser powder bed fusion. J. Mater. Process. Technol. 299, 117316 (2022).

Khairallah, S. A., Anderson, A. T., Rubenchik, A. & King, W. E. Laser powder-bed fusion additive manufacturing: Physics of complex melt flow and formation mechanisms of pores, spatter, and denudation zones. Acta Mater. 108, 36–45 (2016).

Eagar, T. W. & Tsai, N.-S. Temperature fields produced by traveling distributed heat sources. Weld. J. 62, 346–355 (1983).

Leung, C. L. A. et al. Quantification of interdependent dynamics during laser additive manufacturing using X-ray imaging informed multi-physics and multiphase simulation. Adv. Sci. 9, e2203546 (2022).

Grigoriev, S. N. et al. Beam shaping in laser powder bed fusion: Péclet number and dynamic simulation. Metals 12, 722 (2022).

Davis, A. E. et al. Achieving a columnar-to-equiaxed transition through dendrite twinning in high deposition rate additively manufactured titanium alloys. Metall. Mater. Trans. A 55, 1765–1787 (2024).

Baena, R., Drumetz, L. & Gripon, V. Local mixup: Interpolation of closest input signals to prevent manifold intrusion. Signal Process. 219, 109395 (2024).

Zou, H. & Hastie, T. Regularization and variable selection via the elastic net. J. R. Stat. Soc.: Ser. B (Stat. Methodol.) 67, 301–320 (2005).

Friedman, J. H. Greedy function approximation: a gradient boosting machine. Ann. Stat. 29, 1189–1232 (2001).

Prokhorenkova, L., Gusev, G., Vorobev, A., Dorogush, A. V. & Gulin, A. Catboost: unbiased boosting with categorical features. Adv. Neural Inf. Process. Syst. 31, 6638–6648 (2018).

Freund, Y. & Schapire, R. E. A decision-theoretic generalization of on-line learning and an application to boosting. J. Comput. Syst. Sci. 55, 119–139 (1997).

Huber, P. J. Robust estimation of a location parameter. Ann. Math. Stat. 35, 73–101 (1964).

Duan, T. et al. Ngboost: Natural gradient boosting for probabilistic prediction. In International Conference on Machine Learning, 2690–2700 (PMLR, 2020).

Abhilash, P. M., Luo, X., Liu, Q., Madarkar, R. & Walker, C. Towards next-gen smart manufacturing systems: the explainability revolution. npj Adv. Manuf. 1, 8 (2024).

Lundberg, S. M. & Lee, S.-I. A unified approach to interpreting model predictions. In Proc. 31st International Conference on Neural Information Processing Systems (NeurIPS), 4765–4774 https://proceedings.neurips.cc/paper_files/paper/2017/file/8a20a8621978632d76c43dfd28b67767-Paper.pdf (2017).

Acknowledgements

Research reported in this publication was supported by the Qatar Research Development and Innovation Council [NPRP14C-0920–210017]. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of Qatar Research Development and Innovation Council.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

A.K. conceptualized the study, curated data, performed formal analysis and investigation, developed the methodology, validated results, prepared visualizations, and drafted the original manuscript. A.H. conceptualized the study, curated data, performed formal analysis and investigation, developed the methodology, validated results, and contributed to writing, review, and editing. F.G.A. led formal analysis, provided supervision, developed software, and contributed to writing, review, and editing. M.A. performed formal analysis, provided supporting supervision, and contributed to writing, review, and editing. M.K. led supervision and project administration, provided resources, conducted validation, secured funding, and contributed to writing, review, and editing. All authors reviewed and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Karaki, A., Hammoud, A., Alabtah, F.G. et al. CorrosionOptiMap links additive manufacturing process parameters to corrosion of stainless steel. npj Mater Degrad 9, 148 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41529-025-00694-4

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41529-025-00694-4

This article is cited by

-

Process-Induced multiscale features and their impact on the corrosion kinetics of additively manufactured SS316L

Progress in Additive Manufacturing (2025)