Abstract

Multi principal element alloys (MPEAs) have emerged as a novel class of materials with complex compositions and tuneable properties, making them promising candidates for corrosion-resistant applications. However, their vast compositional space complicates the establishment of clear composition-property relationships using conventional experimental and computational methods, which typically yield insufficient data for effectively mapping causal relationships. This study investigates MPEA corrosion behaviour via supervised machine learning (ML). A dataset of alloy compositions, phases, electrolyte characteristics, and corrosion properties was used to train ML models, including random forest, neural network, kernel ridge regression, and LassoIC. To address data scarcity and enhance prediction accuracy, a generative adversarial network (GAN) was employed to generate synthetic data. Retraining the ML models with augmented data led to improvements in predictive accuracy for corrosion properties. The results highlight the effectiveness of an integrated GAN-ML approach in exploring MPEA compositional complexity and accelerating the design of corrosion-resistant alloys.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Corrosion is the degradation of a material resulting from its interaction with the environment, with corrosion presenting as a significant barrier to the reliability and service life of structural materials in applications ranging from infrastructure to aerospace1,2,3,4,5. Studies suggest that 25–30% of annual corrosion costs could be avoided through corrosion management6,7,8. Traditional alloys, designed with a single principal element, often struggle to balance corrosion resistance with other critical properties such as strength and ductility9. In recent years, multi principal element alloys (MPEAs), also inclusive of high-entropy alloys (HEAs), have been developed as a novel category of metallic materials10,11. Unlike conventional alloys, MPEAs incorporate multiple principal elements in near-equiatomic or complex proportions, yielding an expansive compositional space with adjustable properties12,13,14.

The corrosion behaviour of MPEAs, however, is highly variable and far from straightforward15. Studies have shown that their corrosion rate depends on a complex interplay of composition, phase stability, and environmental conditions such as electrolyte type and pH16,17,18. For instance, certain MPEAs form protective passive films that enhance pitting resistance, whereas others exhibit accelerated degradation from phase heterogeneity or micro galvanic effects between constituent elements16. The number of possible MPEA combinations is vast and can be estimated using the formula:

where n is the number of alloying elements and k is the number of principal elements (assuming alloying is in equal atomic ratios)19. Considering non-equiatomic compositions with large numbers of n and k, the number of possible alloys expands to ≫1020, making traditional experimental and computational approaches inadequate for systematically mapping composition-property relationships20,21,22. Experimental trial-and-error approaches are often time-consuming and resource-intensive, while atomistic simulations struggle to capture the full scope of corrosion dynamics under varied conditions. For example, CALPHAD (i.e. thermodynamic calculations) approaches are typically applied to alloys containing a restricted number of elements, because of constraints in the existing thermodynamic databases20,23.

To address these challenges, machine learning (ML) has been increasingly adopted as a tool for predicting material properties, including corrosion performance. Machine learning models, such as random forests, neural networks, and XGBoost have demonstrated effectiveness in predicting corrosion metrics for more conventional alloys like stainless steels and aluminium alloys24,25,26,27. In such studies, accuracies for modelling corrosion behaviour were reported to be around 82–93% with decision tree model24, 80% with RF model25 and 98% with XGBoost model26. Typical data set sizes for corrosion studies to date, which utilise machine learning (ML), are in the range of 50–50028,29. It is known that ML models trained on so-called small datasets (i.e. those with less than 100 entries) can result in models with reduced or limited accuracy, and of which have significant limitations when extrapolating beyond known data bounds.

The application of ML models to rationalise and interpret the corrosion of MPEAs is constrained by limited experimental datasets and the complexity of the MPEA feature space. A recent study however16, compiled a list of 619 unique entries for corrosion properties of MPEAs. That study is the largest holistic compilation of corrosion data for MPEAs to date and highlighted the complexities of visual and human level interpretation of MPEA corrosion. This is because the number of variables in the alloys studied (from the alloy composition to the microstructures developed), along with the test electrolyte and electrolyte concentration utilised, complicated the extraction of simple trends via data analysis. On this basis, there is a clear need to explore supervised machine learning on the issue of MPEA corrosion.

However, in the context of ML modelling being frustrated by the availability of datasets with only limited information or size, it is noted that generative adversarial networks (GANs) have shown promise in materials science by generating synthetic data to augment training sets30,31. For instance, Lee et al.32 employed a conditional GAN for phase prediction of HEAs that improved the accuracy of a deep neural network model from ~85 to 93%. Similarly, Zeni et al.33 developed a GAN model (MatterGen) capable of generating synthetic inorganic materials with over twice the likelihood of novelty and stability, tailored to specific chemistry, symmetry, and mechanical, electronic, and magnetic properties. The augmented data improved prediction accuracy and reduced generalisation error of the ML models.

Generative adversarial networks (GANs), introduced by Goodfellow et al. in 201434, are advanced deep learning models designed to generate synthetic data replicating a given training distribution. A GAN comprises two neural networks: a generator, that generates candidate data samples, and a discriminator, which can assess produced ‘samples’. These components are trained simultaneously in a competitive framework (i.e. a so-called ‘minmax game’), where the generator aims to fool the discriminator by improving its ability to produce realistic data; whilst the discriminator improves its ability to differentiate true data from generated samples. This adversarial interplay refines both networks until the generated data tends towards being statistically indistinguishable from the real dataset - which is posited to enable effective data augmentation for applications including alloy design35,36. To date, the use of GANs in corrosion studies, particularly for MPEAs, remains largely unexplored. While GANs have been used in corrosion image generation for automobiles37 and uncoated steel plates38, research in quantitative corrosion evaluation has mostly focused on supervised modelling39. However, Woldesellasse et al. used a conditional GAN to improve the prediction accuracy of a neural network (from 86% to 96%) for corrosion pit depth of onshore oil and gas buried pipelines through data augmentation29. Additionally, Li et al.22 proposed a GAN model (cardiGAN) for classifying the alloy phases in design and discovery of MPEAs. The proposed network effectively generated novel MPEA compositions and highlighted the potential to accelerate the exploration of new alloys with desirable phase-related properties including corrosion properties.

This present study seeks to advance the field by developing a supervised ML model for MPEA corrosion. The selection of supervised ML models investigated was done on the basis of exploring techniques which are reported to be capable of handling data of high dimensionality. Additionally, this model is developed with GAN-based data augmentation. This combination is, to the best of our knowledge, not yet reported in the literature10,12,20. To overcome data scarcity, a GAN was employed to generate a synthetic dataset, in order to enable accurate predictions upon ML model training. Specifically, a non-dominant sorting optimisation-based generative adversarial network (NSGAN) framework was employed. The novelty of this work lies in synergistically combining these techniques to accelerate the exploration of MPEA design space. Specifically, the study presents a computationally efficient data-driven approach for more accurately predicting and optimising the corrosion performance of MPEAs. Leveraging augmented datasets of compositional and environmental features, ML models were expected to predict the key corrosion metrics, namely: corrosion potential, corrosion current density, and pitting potential. The workflow of our method is illustrated in Fig. 1, providing an intuitive overview of the approach.

Results

Modelling

The predictive performance of four ML models for corrosion properties of MPEAs was evaluated across three key metrics: corrosion current density (icorr), corrosion potential (Ecorr), and pitting potential (Epit), as presented in Fig. 2. Specifically, the data on the left of Fig. 2 is most relevant to discuss first, since such data corresponds to ML modelling with the experimental dataset.

In each row, model performance with (left) real data, and (right) synthetic data is presented for comparison. The x-axes represent four regression models namely LassoIC (Lasso model regularised with an Akaike information criterion), KRR (kernel ridge regression), RF (random forest), and NN (neural network). The performance of each model variant is calculated through average of train (red bars) and test (blue bars) scores within 10 repetitions. The y-axes represent prediction scores based on the coefficient of determination (R2), with error bars indicating the 95% confidence interval.

The supervised regression models included a linear model, LassoIC and three non-linear models: KRR, RF and NN. For icorr, kernel ridge regression model achieved the highest training score (R² ≈ 0.87), but its test score (R² ≈ 0.35) indicated overfitting, a trend also observed in RF. In contrast, neural network model (R² ≈ 0.40 and 0.34 for train and test scores) and LassoIC (R² ≈ 0.34 and 0.25 for train and test scores) demonstrated more consistent performance between training and testing phases, suggesting better generalisability despite lower overall scores. Among the models, RF model exhibited the highest test score for icorr (R² ≈ 0.38) highlighting its superior predictive capability, albeit that when using the experimental dataset with 619 entries, the overall train and test scores for all models were not aspirational. Through the work herein, this again highlights the challenge in materials science, that working with datasets of limited size can frustrate the ability of ML models to perform at high levels of accuracy.

In predicting Ecorr, RF again outperformed other models with the highest test score (R² ≈ 0.66) and a training score of R² ≈ 0.88, while LassoIC and NN exhibited closer train-test alignment, showing less overfitting. Kernel ridge regression model exhibited the second highest prediction accuracy for Ecorr prediction with a test score of R² ≈ 0.60. For Epit, all models showed high performance, with RF and KRR achieving the highest test scores (R² ≈ 0.78). However, similar to Ecorr, NN and LassoIC demonstrated a better alignment in train and test scores, suggesting noticeable generalisability for this property prediction. Across all metrics, error bars representing 95% confidence intervals highlighted variability, particularly in non-linear models, emphasising the importance of proper model selection to balance predictive accuracy and model stability.

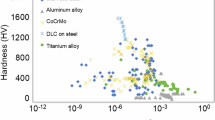

To address the data limitations identified in the initial modelling, particularly the constrained predictive accuracy for icorr and the deviations at extreme values for Ecorr and Epit, the use of synthetic data derived from the NSGAN was employed to augment the MPEA corrosion dataset. These synthetic datasets were designed to capture the underlying distribution of MPEA compositional, microstructural, and environmental features, providing a more diverse and representative training set. This approach has the potential to significantly tackle the scarcity of existing data for the high-dimensional space of MPEAs, as shown in Figs. 3 and 4. These scatter plots visualise the real (solid dots) and synthetic (hollow dots) datasets with colour coding that represents different electrolyte types. As it is evident, the original and synthetic GAN-generated data points for each electrolyte type overlap significantly across the range of all three corrosion properties, indicating that the NSGAN captured the distribution of corrosion behaviour for MPEAs under diverse environmental conditions. These notable overlaps indicate the utility of the data augmentation via employed approach, however, slight discrepancies at the extremes (below −1100 mV for Ecorr and above 2000 mV for Epit) suggest the synthetic data may underrepresent rare conditions.

Following the data augmentation, the models were retrained to re-predict the corrosion behaviour of MPEAs. As shown in Fig. 2, upon re-modelling with the combination of original and GAN-generated datasets, improvements in predictive performance were observed for all corrosion metrics. For icorr, predictive accuracy of retrained models exhibited a substantial increase compared to the initial models. Random forest achieved the highest test score that is increased from R² ≈ 0.38 to R² ≈ 0.80, with a reduced train-test score gap (train R² ≈ 0.65). Kernel ridge regression and NN showed very closed test scores to RF, with R² ≈ 0.82 for KRR and R² ≈ 0.81 for NN. The linear LassoIC and NN models demonstrated no train-test score gap, while for KRR the gap significantly narrowed from 0.52 to 0.12. The results indicate better generalisation, reduced overfitting, and stronger capability in capturing the complex relationships of corrosion current density with the compositional and environmental features for augmented data.

Similarly, for Ecorr and Epit, all test scores improved and the gap between train and test scores reduced likely due to the increased data diversity capturing a broader range of corrosion behaviours. For Ecorr, the predictive accuracy of RF increased from R² ≈ 0.66 to R² ≈ 0.90 (train R² ≈ 0.98), while the test score of KRR improved from R² ≈ 0.60 to R² ≈ 0.88. Neural network and LassoIC achieved the test scores of R² ≈ 0.83 and 0.67, respectively. For Epit, where the initial performance was already accurate (R² ≈ 0.58–0.78), RF and KRR both achieved a test score of R² ≈ 0.95 (train R² ≈ 0.98), with improved prediction accuracy at the boundaries. Neural network and LassoIC also benefited, with the test scores rising to R² ≈ 0.88 for NN, and R² ≈ 0.74 for LassoIC, alongside a tighter train-test alignments, further confirmed the improved performance of the models. A summary of models’ predictive performance with experimental and augmented data are summarised in Table 1.

The augmented dataset provided a more diverse training set, not only mitigated overfitting in RF and KRR but also enabled all models to better handle the complex high-dimensional compositional space of MPEAs, as evidenced by reduced variability in the 95% confidence intervals across all metrics (Fig. 2). The results highlight the effectiveness of combining supervised ML models with data augmentation via GANs (integrated GAN-ML approach) in overcoming data scarcity, addressing the limitations observed in the initial modelling, improving predictive accuracy, and accelerating the understanding and design of corrosion-resistant MPEAs.

To further validate the improved predictive performance with data augmentation, parity plots of predicted versus actual values for current density, corrosion potential, and pitting potential were generated, as shown in Figs. 5, 6, and 7, respectively. The retrained models exhibited tight clustering of points along the 45-degree line for all metrics, confirming the high predictive performance reported in Fig. 2 and Table 1. For icorr (Fig. 5), RF and KRR and NN showed slight scatters, reflecting their substantially improved test scores compared to the initial models. Similarly, for Ecorr (Fig. 6), no systematic biases at lower and higher values were noticed, particularly for RF and KRR, aligning with their improved performance. For Epit (Fig. 7), all models displayed near-perfect alignment along the diagonal, consistent with their high-test scores. These parity plots reinforce the effectiveness of the NSGAN-augmented dataset in improving model accuracy and generalisability.

Graphical user interface

To facilitate practical application of the framework developed in present study, a graphical user interface (GUI) webtool was designed using Google Colab (provided by Google®), that enables users to access the RF models for predicting corrosion properties of any arbitrary MPEA entry (Fig. 8). This tool allows researchers to input compositional and environmental features and obtain predicted corrosion metrics, streamlining the design and screening of corrosion-resistant MPEAs. The GitHub code associated with this Google Colaboratory notebook is publicly accessible through the following hyperlink:

https://colab.research.google.com/drive/1Q504PnMCWydQAQGnZplrNur8h3aMtFHk#scrollTo=LbTtrrB_9dg2

Discussion

This study reveals the impact of integrating supervised machine learning with generative adversarial networks (GAN-ML) for predicting corrosion behaviour of multi principal element alloys (MPEAs):

-

Initial ML models trained on the experimental dataset of 619 entries, struggled to achieve aspirational accuracy, particularly with icorr prediction. The highest performance was achieved using a random forest model, achieving a test score of 0.38.

-

The NSGAN-augmented dataset enabled non-linear models to capture complex composition-property relationships. After retraining with augmented data, random forest, as the most accurate model, achieved test scores of 0.83, 0.90, and 0.95 for icorr, Ecorr, and Epit, respectively.

-

The GAN-ML approach mitigated data scarcity, reduced overfitting, and improved predictive accuracy and generalisability of the models. A workflow for achieving this was presented herein.

-

This methodology facilitated the design of corrosion-resistant MPEAs, streamlining alloy development. This was demonstrated by the development of a user tool (GUI) to permit the prediction – for the first time – of corrosion properties of MPEAs for various environments.

Methods

Experimental data collection and format

In ML scenarios where input data is scarce, the efficacy of ML predictions relies more on the volume and quality of training data than on the specific ML algorithm selected40,41. Hence corrosion data of 619 MPEAs (i.e. 619 unique entries) available from published literature42,43,44,45,46,47,48,49,50,51,52,53,54,55,56,57,58,59,60,61,62,63,64,65,66,67,68,69,70,71,72,73,74,75,76,77,78,79,80,81,82,83,84,85,86,87,88,89,90,91,92,93,94,95,96,97,98,99,100,101,102,103,104,105,106,107,108,109,110,111,112,113,114,115,116,117,118,119,120,121,122,123,124,125,126,127,128,129,130,131,132,133,134,135,136,137,138 were collected in our preliminary work139 for training the ML models used in this research. The dataset was composed of inputs that included electrochemical testing (i.e. environmental) conditions, including electrolyte type and concentration; microstructural phases present; precise alloy compositions; and outputs that included corrosion properties. This data was derived from potentiodynamic polarisation experiments conducted in a range of electrolytes, including chloride-containing solutions, acidic media, and alkaline environments. The key outputs in the form of corrosion properties included corrosion potential (Ecorr), corrosion current density (icorr), and pitting potential (Epit). It is noted that the dataset only included 306 entries for the property of pitting potential (as this parameter was unable to be measured in all empirical tests, since not all electrolyte-alloy combinations promoted alloy passivity). The compiled dataset can provide a robust foundation for training ML models to predict MPEA corrosion performance, offering a practical screening tool despite the inherent variability of literature-sourced data.

Synthetic data generation via a generative adversarial network

This study utilised GANs to capture the underlying data distribution through an iterative process of validating synthesised data. The approach herein involved concurrently generating and optimising 20 sets of novel MPEAs and their output corrosion properties (each set containing 10,000 data points). This was achieved using a non-dominant sorting optimisation-based generative adversarial network (NSGAN) framework. This approach integrates the multi-objective optimisation capabilities of the NSGA-II algorithm with the generative power of a Wasserstein GAN with Gradient Penalty (WGAN-GP)36, enabling the model to implicitly learn and refine data distributions from the real dataset. The NSGAN operates across latent and design spaces, mapping high-dimensional alloy features into a lower-dimensional latent space for efficient multi-objective optimisation. This implementation utilised the Pymoo library for NSGA-II and PyTorch for WGAN-GP for data augmentation. In total 200000 synthetic alloys (and their associated characteristics and outputs) were generated available to augment experimental data. The details of how to generate such synthetic data, have been previously reported by the authors in refs. 140,141, including expanded descriptions and implementation tools.

Data visualisation

To facilitate the analysis of the MPEA corrosion data and evaluate the effectiveness of the NSGAN model in data augmentation, two visualisation techniques were employed using the scikit-learn Python library: distribution plots and the t-distributed stochastic neighbour embedding (t-SNE) dimension reduction algorithm. Kernel density estimation (KDE) was applied to plot and critically analyse the probability distributions of corrosion potential and corrosion current density for both real and GAN-generated MPEA data (Fig. 9).

To explore the high-dimensional feature space of MPEAs comprising 36 features (chemical composition, phase type, electrolyte type and concentration), the t-SNE algorithm was implemented for dimension reduction. This non-linear technique projects the high-dimensional data into a two-dimensional space while preserving local structures and revealing patterns in the dataset. In the t-SNE scatter plot (Fig. 10), each point represents an MPEA entry, with colour-coded markers for real and GAN-generated synthetic data. This approach enables a visual evaluation of the NSGAN model ability to generate synthetic data that aligns with the feature distributions observed in the real dataset.

Machine learning models

To predict the corrosion performance of MPEAs, this study employed a set of supervised ML models: Linear Lasso with Information Criterion (LassoIC), Kernel Ridge Regression (KRR), Random Forest (RF), and Neural Networks (NN). These models were selected for their ability to handle regression tasks across diverse feature spaces and their established efficacy in materials property prediction. The input dataset comprised 36 features is shown in Table 2, including chemical composition of alloys (24 constituent elements), microstructural phase of alloys, electrolyte types, and electrolyte concentration. Data utilised is from testing that is reported to have been conducted at ambient/room temperature (~23 ± 2 °C). The categorical variables, phase and electrolyte type, were transformed into numerical representations using one-hot encoding, expanding the feature set to accommodate their discrete nature while preserving model interpretability.

Hyperparameter tuning

Model training and hyperparameter optimisation for both real and synthetic data were conducted using a 10-fold cross-validation framework implemented via grid search cross-validation (GSCV) from the scikit-learn library. This approach systematically partitioned the training set into 10 subsets, iteratively training on nine folds and validating on the remaining fold, to ensure unbiased performance assessment and minimise overfitting. For each model, GSCV explored a pre-defined hyperparameter space: LassoIC was tuned for the regularisation parameter (α); KRR for the kernel type (e.g., radial basis function) and regularisation strength (α); RF for the number of trees, maximum depth, and minimum samples per split; and NN for the number of hidden layers, neurons per layer, and learning rate.

Evaluation of model performance

Model performance was evaluated using the coefficient of determination (R2) on both training and validation sets. Coefficient of determination as the performance metric is defined as:

where y and \(\hat{y}\) are the actual and predicted values of the target corrosion property.

The 10-fold cross-validation process yielded average performance metrics, guiding the selection of the optimal model configuration for each algorithm. This rigorous evaluation ensured that the models effectively captured the relationships between compositional, structural, and environmental features and the corrosion properties of MPEAs.

Data availability

The datasets generated during the current study are not publicly available as they form part of an ongoing research project but are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Code availability

The code supporting this study is not publicly available due to institutional confidentiality agreements and proprietary dependencies but is available from the corresponding author on reasonable request for academic, non-commercial use.

References

Chawla, S. L., Materials Selection for Corrosion Control (ASM international, 1993).

Koch, G. H., Brongers, M. P. H., Thompson, N. G., Virmani, Y. P. & Payer, J. H. Chapter 1 - Cost of corrosion in the United States. In Handbook of Environmental Degradation of Materials (rd, Kutz, M.) 3–24 (William Andrew Publishing, 2005).

Williams, J. C. & Starke, E. A. Progress in structural materials for aerospace systems11The Golden Jubilee Issue—Selected topics in Materials Science and Engineering: Past, Present and Future, edited by S. Suresh. Acta Mater. 51, 5775–5799 (2003).

Revie, R. W. & Uhlig, H. H. Corrosion and Corrosion Control: An Introduction to Corrosion Science and Engineering (John Wiley & Sons, 2008).

Batchelor, A. W., Lam, L. N. & Chandrasekaran, M. Materials Degradation and its Control by Surface Engineering. (World Scientific, 2011).

Bender, R. et al. Corrosion challenges towards a sustainable society. Mater. Corros. 73, 1730–1751 (2022).

Agarwala, V. S. Control of corrosion and service life. In NACE Corrosion (NACE, 2004).

Schmitt, G. et al. Global needs for knowledge dissemination, research, and development in materials deterioration and corrosion control. World Corros. Organ. 38, 14 (2009).

National Research Council; Division on Engineering and Physical Sciences; National Materials Advisory Board; Committee on Research Opportunities in Corrosion Science and Engineering. Research Opportunities in Corrosion Science and Engineering (The National Academies Press, 2011).

Gerashi, E. et al. Machine learning-aided phase and mechanical properties prediction in multi-principal element alloys. Comput. Mater. Sci. 243, 113114 (2024).

Miracle, D. B. & Senkov, O. N. A critical review of high entropy alloys and related concepts. Acta Mater. 122, 448–511 (2017).

Roy, A. et al. Machine-learning-guided descriptor selection for predicting corrosion resistance in multi-principal element alloys. npj Mater. Degrad. 6, 9 (2022).

Guo, S. Phase selection rules for cast high entropy alloys: an overview. Mater. Sci. Technol. 31, 1223–1230 (2015).

Du, Z. et al. Light-weight multi-principal element alloy Ti50V40Cr5Al5 with high strength-ductility and improved thermo-physical properties. Vacuum 234, 114110 (2025).

Birbilis, N., Choudhary, S., Scully, J. & Taheri, M. A perspective on corrosion of multi-principal element alloys. npj Mater. Degrad. 5, 14 (2021).

Ghorbani, M. et al. Current progress in aqueous corrosion of multi-principal element alloys. Metallurgical and Mater. Trans. A, 55, 2571–2588 (2024).

O’Brien, S. et al. On the microstructure, corrosion behavior and surface films of the multi-principal element alloy CrNiTiV. Electrochim. Acta 505, 144959 (2024).

Kumar, K., Babu, B. S. & Davim, J. P. Coatings: Materials, Processes, Characterization and Optimization (Springer, 2021).

Li, Z., Zeng, Z., Tan, R., Taheri, M. & Birbilis, N. A database of mechanical properties for multi principal element alloys. Chem. Data Collect. 47, 101068 (2023).

Yan, Y., Lu, D. & Wang, K. Accelerated discovery of single-phase refractory high entropy alloys assisted by machine learning. Comput. Mater. Sci. 199, 110723 (2021).

Bhattacharyya, J. J. et al. Lightweight, low cost compositionally complex multiphase alloys with optimized strength, ductility and corrosion resistance: Discovery, design and mechanistic understandings. Mater. Des. 228, 111831 (2023).

Li, Z. et al. cardiGAN: A generative adversarial network model for design and discovery of multi principal element alloys. J. Mater. Sci. Technol. 125, 81–96 (2022).

Ghorbani, M., Boley, M., Nakashima, P. & Birbilis, N. A machine learning approach for accelerated design of magnesium alloys. Part A: Alloy data and property space. J. Magnes. Alloy. 11, 3620–3633 (2023).

Hakimian, S., Pourrahimi, S., Bouzid, A.-H. & Hof, L. A. Application of machine learning for the classification of corrosion behavior in different environments for material selection of stainless steels. Comput. Mater. Sci. 228, 112352 (2023).

Galvao, T. L., Novell-Leruth, G., Kuznetsova, A., Tedim, J. & Gomes, J. R. Elucidating structure–property relationships in aluminum alloy corrosion inhibitors by machine learning. J. Phys. Chem. C. 124, 5624–5635 (2020).

Sheik, S., Mohammed, R., Teeparthi, K. & Raghuvamsi, Y. Machine learning-based prediction of intergranular corrosion resistance in austenitic stainless steels exposed to various heat treatments. J. Inst. Eng. Ser. D 106, 491–504 (2024).

Ghorbani, M., Boley, M., Nakashima, P. & Birbilis, N. A machine learning approach for accelerated design of magnesium alloys. Part B: Regression and property prediction. J. Magnes. Alloy. 11, 4197–4205 (2023).

Coelho, L. B. et al. Reviewing machine learning of corrosion prediction in a data-oriented perspective. npj Mater. Degrad. 6, 8 (2022).

Woldesellasse, H. & Tesfamariam, S. Data augmentation using conditional generative adversarial network (cGAN): Application for prediction of corrosion pit depth and testing using neural network. J. Pipeline Sci. Eng. 3, 100091 (2023).

Liu, S. & Yang, C. Machine learning design for high-entropy alloys: models and algorithms. Metals 14, 235 (2024).

Hong, Y., Hou, B., Jiang, H. & Zhang, J. Machine learning and artificial neural network accelerated computational discoveries in materials science. Wiley Interdisciplinary Reviews. Comput. Mol. Sci. 10, e1450 (2020).

Lee, S. Y., Byeon, S., Kim, H. S., Jin, H. & Lee, S. Deep learning-based phase prediction of high-entropy alloys: Optimization, generation, and explanation. Mater. Des. 197, 109260 (2021).

Zeni, C. et al. A generative model for inorganic materials design. Nature, 639, 624–632 (2025).

Goodfellow, I. J. et al. Generative adversarial nets. In Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems, 27 (NIPS, 2014).

Jabbar, R., Jabbar, R. & Kamoun, S. Recent progress in generative adversarial networks applied to inversely designing inorganic materials: A brief review. Comput. Mater. Sci. 213, 111612 (2022).

Li, Z. & Birbilis, N. Multi-objective optimization-oriented generative adversarial design for multi-principal element alloys. Integrating Mater. Manuf. Innov. 13, 435–444 (2024).

Zuben, A. V. & Viana, F. A. C. Generative adversarial networks for extrapolation of corrosion in automobile images. Expert Syst. Appl. 213, 118849 (2023).

Jiang, F. & Hirohata, M. A GAN-Augmented Corrosion Prediction Model for Uncoated Steel Plates. Appl. Sci. 12, 4706 (2022).

Li, M. et al. Composition driven machine learning for unearthing high-strength lightweight multi-principal element alloys. J. Alloy. Compd. 1008, 176517 (2024).

Thoppil, G. S., Nie, J.-F. & Alankar, A. Hierarchical machine learning based structure–property correlations for as–cast complex concentrated alloys. Comput. Mater. Sci. 216, 111855 (2023).

Ghorbani, M., Boley, M., Nakashima, P. N. H. & Birbilis, N. An active machine learning approach for optimal design of magnesium alloys using Bayesian optimisation. Sci. Rep. 14, 8299 (2024).

Yen, C.-C. et al. Corrosion mechanism of annealed equiatomic AlCoCrFeNi tri-phase high-entropy alloy in 0.5 M H2SO4 aerated aqueous solution. Corros. Sci. 157, 462–471 (2019).

Qiu, Y. et al. Microstructural evolution, electrochemical and corrosion properties of AlxCoCrFeNiTiy high entropy alloys. Mater. Des. 170, 107698 (2019).

Qiu, X.-W., Zhang, Y.-P., He, L. & Liu, C. -g Microstructure and corrosion resistance of AlCrFeCuCo high entropy alloy. J. Alloy. Compd. 549, 195–199 (2013).

Qiu, Y., Gibson, M., Fraser, H. & Birbilis, N. Corrosion characteristics of high entropy alloys. Mater. Sci. Technol. 31, 1235–1243 (2015).

Xu, Z. et al. Corrosion resistance enhancement of CoCrFeMnNi high-entropy alloy fabricated by additive manufacturing. Corros. Sci. 177, 108954 (2020).

Tang, Z., Huang, L., He, W. & Liaw, P. K. Alloying and processing effects on the aqueous corrosion behavior of high-entropy alloys. Entropy 16, 895–911 (2014).

Chou, Y., Yeh, J. & Shih, H. The effect of molybdenum on the corrosion behaviour of the high-entropy alloys Co1.5CrFeNi1.5Ti0.5Mox in aqueous environments. Corros. Sci. 52, 2571–2581 (2010).

Fujieda, T. et al. Mechanical and corrosion properties of CoCrFeNiTi-based high-entropy alloy additive manufactured using selective laser melting. Addit. Manuf. 25, 412–420 (2019).

Zhao, Y. et al. Effects of Ti-to-Al ratios on the phases, microstructures, mechanical properties, and corrosion resistance of Al2-xCoCrFeNiTix high-entropy alloys. J. Alloy. Compd. 805, 585–596 (2019).

Hsu, Y.-J., Chiang, W.-C. & Wu, J.-K. Corrosion behavior of FeCoNiCrCux high-entropy alloys in 3.5% sodium chloride solution. Mater. Chem. Phys. 92, 112–117 (2005).

Mishra, R. K., Sahay, P. P. & Shahi, R. R. Alloying, magnetic and corrosion behavior of AlCrFeMnNiTi high entropy alloy. J. Mater. Sci. 54, 4433–4443 (2019).

Yang, W., Liu, Y., Pang, S., Liaw, P. K. & Zhang, T. Bio-corrosion behavior and in vitro biocompatibility of equimolar TiZrHfNbTa high-entropy alloy. Intermetallics 124, 106845 (2020).

Lu, C.-W., Lu, Y.-S., Lai, Z.-H., Yen, H.-W. & Lee, Y.-L. Comparative corrosion behavior of Fe50Mn30Co10Cr10 dual-phase high-entropy alloy and CoCrFeMnNi high-entropy alloy in 3.5 wt% NaCl solution. J. Alloy. Compd. 842, 155824 (2020).

Shuang, S., Ding, Z. Y., Chung, D., Shi, S. Q. & Yang, Y. Corrosion resistant nanostructured eutectic high entropy alloy. Corros. Sci. 164, 108315 (2020).

Ren, J. et al. Corrosion behavior of selectively laser melted CoCrFeMnNi high entropy alloy. Metals 9, 1029 (2019).

Muangtong, P., Rodchanarowan, A., Chaysuwan, D., Chanlek, N. & Goodall, R. The corrosion behaviour of CoCrFeNi-x (x= Cu, Al, Sn) high entropy alloy systems in chloride solution. Corros. Sci. 172, 108740 (2020).

Xiang, C. et al. Microstructure and corrosion behavior of AlCoCrFeNiSi0.1 high-entropy alloy. Intermetallics 114, 106599 (2019).

Wang, S., Zhao, Y., Xu, X., Cheng, P. & Hou, H. Evolution of mechanical properties and corrosion resistance of Al0.6CoFeNiCr0.4 high-entropy alloys at different heat treatment temperature. Mater. Chem. Phys. 244, 122700 (2020).

Wang, W. et al. Effect of Mo and aging temperature on corrosion behavior of (CoCrFeNi)100-xMox high-entropy alloys. J. Alloy. Compd. 812, 152139 (2020).

Bachani, S. K., Wang, C.-J., Lou, B.-S., Chang, L.-C. & Lee, J.-W. Microstructural characterization, mechanical property and corrosion behavior of VNbMoTaWAl refractory high entropy alloy coatings: Effect of Al content. Surf. Coat. Technol. 403, 126351 (2020).

Shang, X.-L. et al. Effect of Mo Addition on Corrosion Behavior of High-Entropy Alloys CoCrFeNiMox in Aqueous Environments. Acta Metall. Sin. 32, 41–51 (2019).

Godlewska, E. M. et al. Corrosion of Al(Co)CrFeNi High-Entropy Alloys. Front. Mater. 7, 566336 (2020).

Raza, A., Abdulahad, S., Kang, B., Ryu, H. J. & Hong, S. H. Corrosion resistance of weight reduced AlxCrFeMoV high entropy alloys. Appl. Surf. Sci. 485, 368–374 (2019).

Sun, Y., Wang, Z., Yang, H., Lan, A. & Qiao, J. Effects of the element La on the corrosion properties of CrMnFeNi high entropy alloys. J. Alloy. Compd. 842, 155825 (2020).

Li, J., Yang, X., Zhu, R. & Zhang, Y. Corrosion and serration behaviors of TiZr0.5NbCr0.5VxMoy high entropy alloys in aqueous environments. Metals 4, 597–608 (2014).

Soare, V. et al. The mechanical and corrosion behaviors of as-cast and re-melted AlCrCuFeMnNi multi-component high-entropy alloy. Metall. Mater. Trans. A 46, 1468–1473 (2015).

Soare, V. et al. Influence of remelting on microstructure, hardness and corrosion behaviour of AlCoCrFeNiTi high entropy alloy. Mater. Sci. Technol. 31, 1194–1200 (2015).

Zhang, X. et al. Influence of remelting and annealing treatment on corrosion resistance of AlFeNiCoCuCr high entropy alloy in 3.5% NaCl solution. J. Alloy. Compd. 775, 565–570 (2019).

Quiambao, K. F. et al. Passivation of a corrosion resistant high entropy alloy in non-oxidizing sulfate solutions. Acta Mater. 164, 362–376 (2019).

Lin, C. W., Tsai, M. H., Tsai, C. W., Yeh, J. W. & Chen, S. K. Microstructure and aging behaviour of Al5Cr32Fe35Ni22Ti6 high entropy alloy. Mater. Sci. Technol. 31, 1165–1170 (2015).

Lin, C.-M. & Tsai, H.-L. Evolution of microstructure, hardness, and corrosion properties of high-entropy Al0.5CoCrFeNi alloy. Intermetallics 19, 288–294 (2011).

Shon, Y., Joshi, S. S., Katakam, S., Shanker Rajamure, R. & Dahotre, N. B. Laser additive synthesis of high entropy alloy coating on aluminum: Corrosion behavior. Mater. Lett. 142, 122–125 (2015).

Hongbao, C., Ying, W., Jinyong, W., Xuefeng, G. & Hengzhi, F. Microstructural evolution and corrosion behavior of directionally solidified FeCoNiCrAl high entropy alloy. Appl. Mech. Mater. 66-68, 146-149 (2011).

Cui, H. B., Zheng, L. F. & Wang, J. Y. Microstructure evolution and corrosion behavior of directionally solidified FeCoNiCrCu high entropy alloy. Appl. Mech. Mater. 66, 146–149 (2011).

Lee, C., Chang, C., Chen, Y., Yeh, J. & Shih, H. Effect of the aluminium content of AlxCrFe1.5MnNi0.5 high-entropy alloys on the corrosion behaviour in aqueous environments. Corros. Sci. 50, 2053–2060 (2008).

Shih, H. C. et al. Effect of Boron on the Corrosion Properties of Al0.5CoCrCuFeNiBx High Entropy Alloys in 1N Sulfuric Acid. ECS Trans. 2, 15 (2007).

Zheng, Z. Y., Li, X. C., Zhang, C. & Li, J. C. Microstructure and corrosion behaviour of FeCoNiCuSnx high entropy alloys. Mater. Sci. Technol. 31, 1148–1152 (2015).

Zhang, J. J. et al. Corrosion properties of AlxCoCrFeNiTi0.5 high entropy alloys in 0.5M H2SO4 aqueous solution. Mater. Res. Innov. 18, S4-756–S4-760 (2014).

Huang, K. J., Lin, X., Wang, Y. Y., Xie, C. S. & Yue, T. M. Microstructure and corrosion resistance of Cu0.9NiAlCoCrFe high entropy alloy coating on AZ91D magnesium alloys by laser cladding. Mater. Res. Innov. 18, S2-1008–S2-1011 (2014).

Florea, I., Buluc, G., Chelariu, R., Baciu, E. R. & Carcea, I. Microstructure and Corrosion Properties Investigations of AlCrNiCuMn High-Entropy Alloy. Adv. Mater. Res. 1128, 127–133 (2015).

Fazakas, É, Wang, J., Zadorozhnyy, V., Louzguine-Luzgin, D. & Varga, L. Microstructural evolution and corrosion behavior of Al25Ti25Ga25Be25 equi-molar composition alloy. Mater. Corros. 65, 691–695 (2014).

Meghwal, A. et al. Tribological and corrosion performance of an atmospheric plasma sprayed AlCoCr0.5Ni high-entropy alloy coating. Wear 506-507, 204443 (2022).

Wang, P. et al. Microstructural evolution, mechanical properties and corrosion resistance of CoCrFeNiW0.5 high entropy alloys with various annealing heat treatment. J. Alloy. Compd. 918, 165602 (2022).

Hu, R. et al. Microstructure and corrosion properties of AlxCuFeNiCoCr(x = 0.5, 1.0, 1.5, 2.0) high entropy alloys with Al content. J. Alloy. Compd. 921, 165455 (2022).

Chen, X. et al. Effects of Cu-content and passivation treatment on the corrosion resistance of Al0.3CuxCoCrFeNi high-entropy alloys. J. Alloy. Compd. 920, 165956 (2022).

Cui, P. et al. Corrosion behavior and mechanism of dual phase Fe1.125Ni1.06CrAl high entropy alloy. Corros. Sci. 201, 110276 (2022).

Wang, W. et al. Novel Ti-Zr-Hf-Nb-Fe refractory high-entropy alloys for potential biomedical applications. J. Alloy. Compd. 906, 164383 (2022).

Yang, W. et al. Design and properties of novel Ti–Zr–Hf–Nb–Ta high-entropy alloys for biomedical applications. Intermetallics 141, 107421 (2022).

Chavan, A., Mandal, S. & Roy, M. In-Vitro Wear and Corrosion Properties of Cr Added Refractory Ti-Mo-Nb-Ta-W High Entropy Alloys (SSRN 2022).

Ji, C., Ma, A. & Jiang, J. Mechanical properties and corrosion behavior of novel Al-Mg-Zn-Cu-Si lightweight high entropy alloys. J. Alloy. Compd. 900, 163508 (2022).

Chen, W. et al. Microstructural Evolution, Mechanical Properties, and Corrosion Behavior of an Al7.5Co20.5Fe24Ni24Cr24 High-Entropy Alloy. Adv. Eng. Mater. 25, 2200780 (2023).

Kuo, P.-C. et al. The effect of increasing nickel content on the microstructure, hardness, and corrosion resistance of the CuFeTiZrNi x high-entropy alloys. Materials 15, 3098 (2022).

Liu, J., Zhang, X. & Yuan, Z. Structures and properties of biocompatible Ti-Zr-Nb-Fe-Mo medium entropy alloys. Mater. Today Commun. 32, 103808 (2022).

Liao, L., Gao, R., Yang, Z. H., Wu, S. T. & Wan, Q. A study on the wear and corrosion resistance of high-entropy alloy treated with laser shock peening and PVD coating. Surf. Coat. Technol. 437, 128281 (2022).

Tsau, C.-H., Chen, J.-Y. & Chien, T.-Y. Corrosion Behavior of CrFeCoNiVx (x= 0.5 and 1) High-Entropy Alloys in 1M Sulfuric Acid and 1M Hydrochloric Acid Solutions. Materials 15, 3639 (2022).

Zhicheng, Z., Aidong, L., Min, Z. & Junwei, Q. Effect of Ce on the localized corrosion behavior of non-equiatomic high-entropy alloy Fe40Mn20Cr20Ni20 in 0.5 M H2SO4 solution. Corros. Sci. 206, 110489 (2022).

Sokkalingam, R. et al. Additive Manufacturing of CoCrFeMnNi High-Entropy Alloy/AISI 316L Stainless Steel Bimetallic Structures. Adv. Eng. Mater. 25, 2200341 (2023).

Tokarewicz, M., Grądzka-Dahlke, M., Rećko, K., Łępicka, M. & Czajkowska, K. Investigation of the structure and corrosion resistance of novel high-entropy alloys for potential biomedical applications. Materials 15, 3938 (2022).

Sarac, B. et al. Transition metal-based high entropy alloy microfiber electrodes: Corrosion behavior and hydrogen activity. Corros. Sci. 193, 109880 (2021).

Ren, Y. et al. A comparative study on microstructure, nanomechanical and corrosion behaviors of AlCoCuFeNi high entropy alloys fabricated by selective laser melting and laser metal deposition. J. Mater. Sci. Technol. 131, 221–230 (2022).

Shi, Y. et al. Corrosion of AlxCoCrFeNi high-entropy alloys: Al-content and potential scan-rate dependent pitting behavior. Corros. Sci. 119, 33–45 (2017).

Kumar, N. et al. Understanding effect of 3.5 wt.% NaCl on the corrosion of Al0.1CoCrFeNi high-entropy alloy. J. Nucl. Mater. 495, 154–163 (2017).

Zhang, S., Wu, C. L., Zhang, C. H., Guan, M. & Tan, J. Z. Laser surface alloying of FeCoCrAlNi high-entropy alloy on 304 stainless steel to enhance corrosion and cavitation erosion resistance. Opt. Laser Technol. 84, 23–31 (2016).

Qiu, X. -w, Wu, M. -j, Liu, C. -g, Zhang, Y. -p & Huang, C. -x Corrosion performance of Al2CrFeCoxCuNiTi high-entropy alloy coatings in acid liquids. J. Alloy. Compd. 708, 353–357 (2017).

Shi, Y. et al. Homogenization of AlxCoCrFeNi high-entropy alloys with improved corrosion resistance. Corros. Sci. 133, 120–131 (2018).

Ayyagari, A. et al. Reciprocating sliding wear behavior of high entropy alloys in dry and marine environments. Mater. Chem. Phys. 210, 162–169 (2018).

Wong, S.-K., Shun, T.-T., Chang, C.-H. & Lee, C.-F. Microstructures and properties of Al0.3CoCrFeNiMnx high-entropy alloys. Mater. Chem. Phys. 210, 146–151 (2018).

Wu, C. L., Zhang, S., Zhang, C. H., Zhang, H. & Dong, S. Y. Phase evolution and properties in laser surface alloying of FeCoCrAlCuNix high-entropy alloy on copper substrate. Surf. Coat. Technol. 315, 368–376 (2017).

Zhang, X. et al. Design of NbNiTaTi refractory high-entropy alloy via NiTi eutectic phase. J. Alloy. Compd. 925, 166741 (2022).

Zhang, Z., Axinte, E., Ge, W., Shang, C. & Wang, Y. Microstructure, mechanical properties and corrosion resistance of CuZrY/Al, Ti, Hf series high-entropy alloys. Mater. Des. 108, 106–113 (2016).

Xiao, D. H. et al. Microstructure, mechanical and corrosion behaviors of AlCoCuFeNi-(Cr,Ti) high entropy alloys. Mater. Des. 116, 438–447 (2017).

Shang, C. et al. CoCrFeNi(W1−xMox) high-entropy alloy coatings with excellent mechanical properties and corrosion resistance prepared by mechanical alloying and hot pressing sintering. Mater. Des. 117, 193–202 (2017).

Cai, Y. et al. Influence of dilution rate on the microstructure and properties of FeCrCoNi high-entropy alloy coating. Mater. Des. 142, 124–137 (2018).

Zhang, Z.-C., Lan, A.-D., Zhang, M. & Qiao, J.-W. Effect of Ce on the pitting corrosion resistance of non-equiatomic high-entropy alloy Fe40Mn20Cr20Ni20 in 3.5wt% NaCl solution. J. Alloy. Compd. 909, 164641 (2022).

Wang, R., Zhang, K., Davies, C. & Wu, X. Evolution of microstructure, mechanical and corrosion properties of AlCoCrFeNi high-entropy alloy prepared by direct laser fabrication. J. Alloy. Compd. 694, 971–981 (2017).

Wu, C. L., Zhang, S., Zhang, C. H., Zhang, H. & Dong, S. Y. Phase evolution and cavitation erosion-corrosion behavior of FeCoCrAlNiTix high entropy alloy coatings on 304 stainless steel by laser surface alloying. J. Alloy. Compd. 698, 761–770 (2017).

Jiang, S., Lin, Z., Xu, H. & Sun, Y. Studies on the microstructure and properties of AlxCoCrFeNiTi1-x high entropy alloys. J. Alloy. Compd. 741, 826–833 (2018).

Qiu, X. Microstructure, hardness and corrosion resistance of Al2CoCrCuFeNiTix high-entropy alloy coatings prepared by rapid solidification. J. Alloy. Compd. 735, 359–364 (2018).

Wang, S.-P. & Xu, J. TiZrNbTaMo high-entropy alloy designed for orthopedic implants: As-cast microstructure and mechanical properties. Mater. Sci. Eng.: C. 73, 80–89 (2017).

Nair, R. B. et al. Exceptionally high cavitation erosion and corrosion resistance of a high entropy alloy. Ultrason. Sonochem. 41, 252–260 (2018).

Kukshal, V., Patnaik, A. & Bhat, I. Corrosion and thermal behaviour of AlCr1.5CuFeNi2Tix high-entropy alloys. Mater. Today.: Proc. 5, 17073–17079 (2018).

Kuwabara, K. et al. Mechanical and corrosion properties of AlCoCrFeNi high-entropy alloy fabricated with selective electron beam melting. Addit. Manuf. 23, 264–271 (2018).

Shang, C., Axinte, E., Ge, W., Zhang, Z. & Wang, Y. High-entropy alloy coatings with excellent mechanical, corrosion resistance and magnetic properties prepared by mechanical alloying and hot pressing sintering. Surf. Interfaces 9, 36–43 (2017).

Rodriguez, A. A. et al. Effect of molybdenum on the corrosion behavior of high-entropy alloys CoCrFeNi2 and CoCrFeNi2Mo0.25 under sodium chloride aqueous conditions. Adv. Mater. Sci. Eng. 2018, 3016304 (2018).

Nair, R. B., Arora, H. S., Ayyagari, A., Mukherjee, S. & Grewal, H. S. High entropy alloys: prospective materials for tribo-corrosion applications. Adv. Eng. Mater. 20, 1700946 (2018).

Dou, D., Li, X. C., Zheng, Z. Y. & Li, J. C. Coatings of FeAlCoCuNiV high entropy alloy. Surf. Eng. 32, 766–770 (2016).

Gao, L. et al. Microstructure, mechanical and corrosion behaviors of CoCrFeNiAl0.3 high entropy alloy (HEA) films. Coatings 7, 156 (2017).

Zhang, M., Zhang, L., Liaw, P. K., Li, G. & Liu, R. Effect of Nb content on thermal stability, mechanical and corrosion behaviors of hypoeutectic CoCrFeNiNbχ high-entropy alloys. J. Mater. Res. 33, 3276–3286 (2018).

Tan, X.-R. et al. Effects of hot pressing temperature on microstructure, hardness and corrosion resistance of Al2NbTi3V2Zr high-entropy alloy. Mater. Sci. Technol. 32, 1582–1591 (2016).

Wang, W., Wang, J., Yi, H., Qi, W. & Peng, Q. Effect of molybdenum additives on corrosion behavior of (CoCrFeNi) 100−x Mox high-entropy alloys. Entropy 20, 908 (2018).

Huang, K. et al. Wear and corrosion resistance of Al0.5CoCrCuFeNi high-entropy alloy coating deposited on AZ91D magnesium alloy by laser cladding. Entropy 20, 915 (2018).

Han, Z. et al. Structures and corrosion properties of the AlCrFeNiMo0.5Tix high entropy alloys. Mater. Corros. 69, 641–647 (2018).

Tan, X. et al. Effects of milling on the corrosion behavior of Al2NbTi3V2Zr high-entropy alloy system in 10% nitric acid solution. Mater. Corros. 68, 1080–1089 (2017).

Shi, Y., Ni, C., Liu, J. & Huang, G. Microstructure and properties of laser clad high-entropy alloy coating on aluminium. Mater. Sci. Technol. 34, 1239–1245 (2018).

Rodriguez, A., Tylczak, J. H. & Ziomek-Moroz, M. Corrosion behavior of CoCrFeMnNi high-entropy alloys (HEAs) under aqueous acidic conditions. ECS Trans. 77, 741 (2017).

Zhang, B., Zhang, Y. & Guo, S. M. A thermodynamic study of corrosion behaviors for CoCrFeNi-based high-entropy alloys. J. Mater. Sci. 53, 14729–14738 (2018).

Shi, Y., Yang, B. & Liaw, P. K. Corrosion-resistant high-entropy alloys: A review. Metals 7, 43 (2017).

Ghorbani, M., Birbilis, N. & Laleh, M. Additively Manufactured Multi Principal Element Alloy Corrosion Database, 3 (Mendeley Data, 2025).

Li, Z. & Birbilis, N. NSGAN: a non-dominant sorting optimisation-based generative adversarial design framework for alloy discovery. npj Comput. Mater. 10, 112 (2024).

Li, Z. & Birbilis, N. Multi-objective Optimization-Oriented Generative Adversarial Design for Multi-principal Element Alloys. Integr. Mater. Manuf. Innov. 13, 435–444 (2024).

Acknowledgements

Financial support from the Office of Naval Research under the contract ONR: N00014-17-1-2807 with Dr. David Shifler and Dr. Clint Novotny as program officers is gratefully acknowledged. The computational resources provided by the Applied Artificial Intelligence Institute (A²I²) cluster at Deakin University, which facilitated the machine learning modelling in this study, are also acknowledged.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

M.G.: Writing - Original Draft, Data curation, Coding and modelling, Writing - Review & Editing, Formal analysis. Z.L.: Coding and modelling (NSGAN development), Writing - Review & Editing, A.P.: Coding, Computing, Writing - Review & Editing, R.V.: Writing - Review & Editing, Resources. N.B.: Writing - Original Draft, Data curation, Writing - Review & Editing, Supervision, Project administration.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare that there are no competing or conflicts of interests. Professor Nick Birbilis is Editor-in-Chief of npj Materials Degradation but was not involved in the review or editorial decision process for this manuscript. The remaining authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Ghorbani, M., Li, Z., Pasquini, A. et al. Supervised machine learning for corrosion assessment of multi-principal element alloys using experimental and generative datasets. npj Mater Degrad 9, 155 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41529-025-00700-9

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41529-025-00700-9