Abstract

This review explores the aqueous corrosion of multi-principal element alloys (MPEAs) that have been prepared using additive manufacturing (AM), inclusive of laser powder bed fusion, directed energy deposition and electron beam melting. The impact of additive manufacturing techniques upon the microstructural features of MPEAs may influence corrosion resistance, through inducing an influence on grain size, phase distribution, and local nano-chemistry. Emphasis is placed on the comparative performance of MPEAs in various corrosive environments, highlighting key findings. The review aims to provide insights into the influence of AM as a processing method for MPEA production – in the context of impact upon corrosion.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

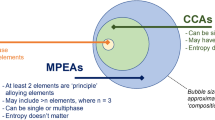

The field of multi-principal element alloys (MPEAs) remains an active area of research—driven by interest in the unique physical properties that have been revealed by the so-called high entropy alloys (HEAs)1. In this study, the term MPEAs is used as a broad terminology to describe alloys containing at least two principal alloying elements, hence inclusive of HEAs2,3,4. In the growing number of works regarding MPEAs to date, it is clear that many unique microstructures and elemental combinations are possible, with only a (very) small fraction of the possible alloys having been explored to date5. Key parameters such as valence electron concentration (VEC) and entropy of mixing are typically considered as characteristic parameters for defining and classifying HEAs and MPEAs6. The favourable properties of MPEAs include reports of high strength and hardness, high thermal stability, wear resistance, and several instances of exceptionally high corrosion resistance4,7. Whilst such favourable properties of MPEAs are emerging, a general feature of several MPEAs (and many, if not most, HEAs) is limited ductility and processability in manufacturing8,9. Most MPEAs explored to date have been produced via arc melting, with some exceptions having utilised ball milling or powder metallurgy approaches10,11,12,13. Arc melting typically produces relatively small specimens (typically with a maximum dimension below 100 mm), and limited ductility (i.e. brittleness) does not readily allow for thermomechanical processing of many MPEAs. As a consequence, there is an essential driver for exploring the production of MPEAs using additive manufacturing (AM) techniques. This is because AM can uniquely permit the following: (i) scalable production of components/specimens in their final net-shape, (ii) alleviate the requirement of subsequent forming operations, (iii) produce MPEAs with diverse and previously unexplored compositions, because the input energy sources used for metal AM generate local temperatures in excess of 3000 °C14, capable of melting elements inclusive of tungsten (and all the transition metals).

Reports of the production of AM prepared MPEAs are all relatively recent, commencing in the past decade, with most reports confined to the past few years. Of particular interest to this critical review is the works that have explored AM prepared MPEAs, and reported their findings with regards to aqueous corrosion performance—which includes ~55 studies, all of which have been sought to be embodied herein. Ahead of reviewing the corrosion of AM MPEAs, it is prudent to briefly discuss the characteristics (separately) of the corrosion of AM prepared alloys exclusive of MPEAs, and MPEAs not prepared by AM.

Corrosion of MPEAs

The corrosion of MPEAs, fabricated by methods other than additive manufacturing, is a topic that has been reviewed in works spanning back to 201515. A number of works have focused on subsets of MPEAs, namely HEAs, and have sought to identify universal trends among specific alloy families1,16,17,18,19,20,21. Key trends include that most of the alloys studied have been explored in either sulphuric acid or chloride-containing environments at neutral pH with many MPEAs displaying spontaneous passivity and hence appreciable corrosion resistance. There are some exceptions, however, and therefore the general statement that all MPEAs (or HEAs) are corrosion resistant is now known to not be empirically true. This was shown through various data representations in the most recent review on the topic of MPEA corrosion22, which revealed the wide range of scatter in the corrosion performance of MPEAs reported to date. Furthermore, that review also compiled a publicly accessible database that reports the aqueous corrosion properties of essentially all MPEAs explored until 202423. Of the general characteristics associated that can be gleaned from the numerous reviews on the topic of MPEA corrosion, it may be noted that:

-

There is no clear relationship (or yet apparent relationship) between bulk MPEA composition and corrosion performance. For example, having a higher ‘noble’ element concentration in one MPEA did not assure a corrosion rate lower than a different MPEA with a lower ‘noble’ element concentration. There is however, a complex relationship between all the elements that comprise an MPEA that is not universally understood at present.

-

The surface films (and passive films) that form upon MPEAs are complex, in that they are—for works that have sought to study them—multilayer in nature. Such films also include oxidised elements in proportions that vary widely from the bulk alloy stoichiometry, indicating that dissolution (and oxidation) is incongruent for essentially all MPEAs. Whilst the present review is focused on aqueous corrosion, similar reports exist in the domain of oxidation24.

-

Reviews to date have suggested that there is somewhat less sensitivity to microstructure-driven corrosion in MPEAs than in single principal element alloys. However, there is a significant sensitivity to bulk MPEA composition.

-

There is inadequacy in predictive capabilities to account for cooperative elemental effects during passivation of multi-principal element systems, where traditional approaches fail to capture the synergistic interactions between multiple principal elements. This makes conventional thermodynamic, kinetic, and empirical models largely ineffective for predicting passive film formation, stability, and breakdown in MPEAs.

-

Future work is needed to better understand the corrosion of MPEAs, and such future work is likely to necessarily need to explore subsets of MPEA families (rather than looking at MPEAs as a single class of alloys) in order to make progress in mechanistic interpretations.

Corrosion of AM prepared alloys

Additive manufacturing encompasses a range of techniques that differ in their source of energy to generate interlayer bonding. The most common commercial AM methods use either a laser beam, or electron beam, to generate a focused localisation of heat (and hence, melting). Despite different energy sources, AM enables the production of components in a layer-by-layer manner25. The most widely used AM methods for preparing metallic materials include, (i) laser powder bed fusion (LPBF), which may often be called alternative names that include selective laser melting or selective laser sintering, (ii) Directed energy deposition (DED), which is also often called direct laser deposition, and (iii) Electron beam melting (EBM). Each of these AM methods offers unique benefits, such as material versatility, unique heating and cooling rates, geometric freedom, hence making them all suitable for various applications across different industries and specific application requirements26. Whilst there has been a recent emergence of liquid and solid-state AM methods that include WAAM (wire arc additive manufacturing) and friction stir additive manufacturing, such methods are yet to be explored for MPEAs on the basis that bulk MPEAs for such processes are not readily available.

To date, there have been a number of reviews related to the corrosion performance of AM prepared alloys (exclusive of the topic of MPEAs). Of such reviews, the comprehensive study from Sander et al.27 revealed (pictorially) some of the unique facets that accompany AM, as relevant to corrosion. For example, Fig. 1 reveals the impact that laser-based AM may have upon alloy components. Such features are unique when compared with conventional cast or wrought processing of alloys. As noted in Fig. 1, the unique features that are imposed by AM are numerous, all of which merit appropriate consideration (where relevant) in the ultimate corrosion response of AM prepared alloys.

Reproduced with permission from ref. 27.

The other facet regarding AM prepared alloys that merits consideration, is the length scale over which the phenomena depicted in Fig. 1 will occur. These phenomena include microstructural characteristics, defects28 or residual stress—and are depicted in Fig. 2.

Reproduced with permission from ref. 27.

Since the review of Sander et al.27. Regarding corrosion of AM prepared alloys, there have been several holistic reviews29 and reviews specific to corrosion of AM prepared steels30, aluminium alloys31 and nickel alloys32. Of the general characteristics associated that can be gleaned from the numerous reviews on the topic of corrosion of AM prepared alloys, it may be noted that:

-

The presence of so-called ‘defects’ is not universally detrimental. For example, there is weak evidence to suggest that residual stress, oxide inclusions, dislocation networks, or final density (for density >99%) are detrimental33,34.

-

Recalling that analysis relates to single principal element alloys only, the greatest influence on corrosion of AM prepared alloys is alloy microstructure, which can be heavily altered (in comparison to non-AM alloys of similar composition) through laser-based processing. This is because rapid (high) heating and rapid cooling rates8,9,11,35,36, can either dissolve particles in the alloy structure, or prohibit particles forming through rapid solidification.

-

Novel corrosion mechanisms have been revealed in some instances, owing to the very unique alloy structures being produced by AM. For example, AM prepared alloys can readily access unique ranges of composition that cannot be produced by casting operations—allowing excess solute concentration and non-equilibrium (metastable) structures that arise from rapid solidification37.

-

It is difficult to compare the corrosion of the same AM-prepared alloy with the non-AM prepared counterpart. This is because of the typically significant difference in microstructure that arises, including differences in solute distribution, grain size and texture, and phases present. For example, AM prepared aluminium alloy AA2024 has a different second phase compared to non-AM AA2024 (i.e. θ-phase vs. S phase), yielding a different corrosion response and mechanism38. Similarly, aluminium alloy AA7075 has a different second phase compared to non-AM AA7075 (i.e. ν-phase vs. η phase)39. Printing parameters can also drastically alter the corrosion resistance of a single alloy40,41.

Corrosion of AM prepared MPEAs

Understanding how the unique microstructures of AM-produced MPEAs interact with aqueous environments will be essential for predicting their longevity and reliability in service. The interplay between AM and the corrosion behaviour of MPEAs is a relatively new area of research. Based upon the (very brief) synopses above regarding the unique facets and complexity of MPEA corrosion and the complexity of corrosion of AM prepared alloys—the understanding of AM-MPEA corrosion will harbour even more significant complexity. This likely includes facets of corrosion that have not previously been dealt with or considered, which may range from local chemical fluctuations related to MPEA ordering to unique microstructures (and most certainly, new phases) not previously evaluated. Interestingly, there have been a number of reviews to date regarding the corrosion of AM prepared HEAs, including that of Das et al.42, Zhang et al.26 and Moghaddam et al.25. Such prior reviews did not, however, firmly articulate mechanistic details. At present (and since 2022), there are considerably more recent works regarding the corrosion of AM-MPEAs that can be reviewed, including the prospect of presenting a consolidated dataset for the community (which the present review does). Therefore, the present review aims to be a critical overview of the current state of research on the aqueous corrosion behaviour of AM-MPEAs and future considerations that may be relevant, including a database that is in a format that permits machine learning.

A survey of AM-MPEA corrosion

Overview of corrosion data to date

In exploring the literature related to AM-MPEA corrosion, each study was evaluated and the associated data extracted. This was done in order to provide a consolidated database of alloy composition and corrosion properties (including corrosion potential, corrosion current density, and pitting potential) that could be analysed in order to infer any trends. The associated data may be found and accessed at ref. 43. Such data may be presented in many formats (and by making such data available, the reader may wish to make their own representations), however an overview of the data extracted inclusive of all works is presented in Figs. 3 and 4.

What is evident from Figs. 3 and 4 is that AM-MPEAs have been tested in a variety of electrolytes (as depicted in the associated legend), and in many cases, there is a non-AM comparator set of data with which to compare the AM-MPEAs with. The consolidated plot in Fig. 3 indicates that there is a wide spread of corrosion current densities (icorr) reported (~8 orders of magnitude), along with a wide spread of corrosion potentials (a range of ~2 V). Whilst the data in Fig. 3 does not disambiguate specific research works, one high-level observation is that the AM-MPEAs are confined to a smaller range of icorr (~4 orders of magnitude) and corrosion potential (a range of ~1 V).

An additional observation from Figs. 3 and 4 is that the majority of reported icorr values for AM-MPEAs are below 10 μA/cm2, which are considered to be relatively low rates of corrosion. Similar to the corrosion potentials, there exists a wide spread of pitting potentials for non-AM-MPEAs rather that the spread for AM-MPEAs, as shown in Fig. 4.

To visually observe the presence of any other first-order trends in the consolidated data extracted from the literature, the icorr of AM-MPEAs was plotted against the alloys respective VEC, and entropy of mixing, seen in Fig. 5. These so called ‘empirical parameters’ were calculated from the respective alloy composition44. There is no discernible (visual) trend between corrosion rate and VEC or entropy of mixing.

Exploring findings from individual studies regarding AM-MPEAs corrosion

In order to provide a more nuanced assessment of the specific MPEA systems that have been explored by AM production to date (including the alloy testing regime, measurement techniques adopted, evaluated corrosion properties, and any conclusions drawn from the respective authors), a compilation has been made in Table 1, followed by critical discussion.

Some features from the literature concerning AM-MPEA corrosion

The combination of specific information (Table 1) and a more holistic treatise of literature reports (Figs. 3 and 4), allow some first order observations to be made. Some such observations are listed in this section, and include the following:

-

Not all papers (and in fact, very few) compared the performance of the AM prepared MPEA with a cast or conventionally prepared counterpart. This is, however, understandable, on the basis that many MPEAs (including some novel MPEAs reviewed) are not easily amenable to conventional production—and hence why AM was explored as the production method. Nonetheless, making an assessment of the general impacts of the AM production method relative to casting, was not readily possible.

-

It was noted that AM prepared MPEAs had in essentially all cases, refined microstructures (finer grains)12,45,46, more uniform elemental distributions47, altering phase fractions45,48,49, alleviated segregations13, and sub-grain cellular structures50 due to rapid solidification. This is a known feature of laser-based AM prepared alloys; however, it was notable across the breadth of AM-MPEAs explored.

-

Of the studies reviewed, most tended to explore properties other than corrosion, as the principal purpose of the study (i.e. mechanical properties, wear, etc). This meant that in many instances, the quality and interpretability of the corrosion section of the work was not at an advanced level. In several studies, the corrosion section was illegible (i.e. no quantification of test results, no reporting of reference electrode type, etc). Most of the works reviewed have been published in sources that are outside the corrosion community, indicating that there remains significant future work in the broader corrosion field to be explored.

-

One feature of the works reviewed that was evident from several studies, and which merits emphasis, is that there is a trend of passive current density being decreased in cases where an AM-MPEA is compared with a conventionally prepared MPEA8,13,35,46,47,51. A montage of associated data has been compiled as Fig. 6, revealing this phenomenon. The data in Fig. 6 is from four independent studies of LPBF prepared alloys, including three different electrolytes, which clearly shows in all cases a lower passive current density for the AM prepared MPEA. Grain refinement and cellular structure from the AM process, and also and rapid diffusion of passivating elements such as Cr may contribute to this phenomenon52. It is noted, however, that not all AM processes lead to grain refinement. Whilst LBPF generally does lead to grain refinement (due to rapid cooling), DED may conversely lead to comparatively large columnar grains (including through retained heat in the DED build).

Fig. 6: Polarisation data collected from four different studies. Each alloy was LPBF prepared and tested in a unique electrolyte. Data represents a AM prepared CoCrFeMnNi tested in 3.5 wt. % NaCl51; b AM prepared FeCoCrNiMn tested in borate buffer solution13; c AM prepared CoCrFeMnNi tested in 3.5 wt. % NaCl47; d AM prepared CoCrFeNi tested in 0.5 M H2SO435. All studies depict a lower passive current density for the AM prepared MPEA being studied.

-

Many of the studies reviewed took a focused approach, exploring specific effects that include the effect of laser scanning speed11, or laser energy (or volumetric energy density)46,49,53,54,55 during the AM process; the effect of post AM heat-treatments9,48,56,57,58,59,60,61, or the effect of compositional variations7,12 in a specific alloy system.

-

Most studies carried out potentiodynamic polarisation as the means of corrosion assessment, which allowed for the determination of Ecorr, icorr and Epit (where relevant) across essentially all of the AM-MPEAs reviewed.

-

Many studies proposed mechanisms or postulates in order to rationalise the experimentally observed results. In the majority of cases, mechanistic descriptions were hypothesis-based and not supported by experimental evidence. For example, additional detailed experiments would be required in order to quantify and validate possible passive film compositions or elemental segregation at the nanoscale. That said, several studies did make specific assertions that could be supported from their own data. This was sought to be captured in the furthest right-hand column in Table 1—where readers are referred to a synopsis of key findings from each unique study reviewed. An example of outcomes from a single study is shown in Fig. 7, where the authors determined a relationship (trend) between corrosion behaviour and laser energy density (in J/mm2)55. The laser energy density is calculated based on the laser power (in W), divided by the laser scan speed (mm/min) and laser spot diameter (mm). In that study (Fig. 7), the AlCoCrFeNi2.1 alloy corrosion response varied with laser energy density on the basis that the laser energy density dictated the resultant cooling rate, and hence, the BCC:FCC ratio in the alloy produced, though no mechanistic interpretations presented.

Fig. 7 Polarisation data collected in in 3.5 wt. % NaCl for LPBF prepared AlCoCrFeNi2.1, revealing the effect of laser energy density (in J/mm2) upon polarisation response55.

-

Several studies explored the impact of post-AM heat treatments. Generally speaking, in most cases, there was a corrosion improvement after aging (heat treatment) which was attributed to the modifications in alloy microstructure (in many cases, explored within the respective study). Additionally, such studies postulated changes in passive film chemistry and an enhancement in passivity (which was, however, not thoroughly explored in any study reviewed). Thermal annealing leading to recrystallisation on as-built microstructures would offer a simple yet efficient way to assess the role of metastable microstructure features (dislocations, micro segregation, metastable phases) on corrosion behaviour.

-

In the vast majority of studies, no advanced electrochemical analysis (inclusive of re-passivation assessment) was carried out. Similarly, detailed assessment of passivation by alternative means (i.e. potentiostatic or scratch testing) was not explored.

-

It is noted that the review herein has focused on AM methods that produce dense alloys, however, there are recent works that have explored the use of binder jetting to prepare MPEAs62,63. In one such study62, it was determined that binder jet prepared CoCrFeMnNi was able to demonstrate a corrosion rate that was comparable to SS 316 L.

-

Not necessary directly related to corrosion of AM-MPEAs, it, however, merits comment that it was possible in several studies to successfully produce AM-MPEAs via the use of blended alloy powders61 or elemental metal powders11,54,58,64,65. This is an important (if not significant) finding, because it means that AM-MPEAs can be produced without the need for significant pre-processing, alloying or production of complex powders. This facet alone, can help accelerate the exploration of AM-MPEAs and the field more generally.

General discussion

As foreshadowed in the Introduction to this review, there is considerable complexity in the topic of corrosion of additively manufactured alloys (in isolation) and in the topic of corrosion of MPEAs (in isolation). It therefore stands to reason that general observations that pertain to the corrosion behaviour of AM-MPEAs may be difficult to glean. This is, however, an unsatisfying outcome, on the basis that an individual and full empirical studies (at the level of required detail) for each AM-MPEA being considered, is not tenable. The scale of the required experiments and the associated cost and burden is prohibitive. What is therefore essential to assess at present is what can be done with experimental data, to contribute towards approaches that can permit future design or assessments with a decreased reliance upon ongoing experiments.

One such approach is a data science approach, which relies on the collection and summation of data for ongoing machine learning. To this end, a database of the studies reviewed herein has been compiled and made available at an open repository43, albeit noting that there is presently insufficient data (97 datapoints) to permit accurate machine learning. Future works, however, will remain important to build a database of knowledge that can be utilised and assessed for underlying trends.

Another approach, which is most fitting in the present, is to seek to rationalise corrosion behaviour of AM-MPEAs based on mechanistic factors. To this end, it is widely accepted that the corrosion of metallic alloys is closely linked to alloy microstructure (and micro/nano-chemistry). To this end, the accompanying microstructural analyses in the literature that were reviewed, merits specific attention. There are undoubtedly rather unique microstructures that form in AM-MPEAs. This is because the compositional complexity of AM-MPEAs gives rise to unique physical metallurgy (rapid solidification, excessive solute, uniform elemental distribution, multiple phases, etc.) in the context of AM processing. Consequently, it is possible to extract some key facets of microstructures (and microstructural features) developed in AM-MPEAs, that can guide mechanistic interpretations with regards to their corrosion performance. Some key examples are elaborated below. Furthermore, whilst the present review focused principally on the (limited) works that include some reference to corrosion, there is wider reportage of AM-MPEAs in the context of other properties, with key early reports dating back as far as 201566.

MPEAs possess some of the most complex microstructures of all metallic alloys, this includes multiple phases that respond to thermal treatment, and often, metastable or previously uncharacterised phases. In addition, such features are often present at the sub-micrometre scale. One example is given in Fig. 8 for LPBF prepared CoCrFeNiMo0.2. What can be observed is a cellular substructure in the alloy microstructure. Such cellular substructures are common to LPBF prepared alloys that have a high concentration of alloying elements (in the case of single principal element alloys) and essentially this qualifies all MPEAs. It is observed that such ‘cells’ can be sub-micron in size. Furthermore, what can also be observed from Fig. 8, is that certain alloying elements may be depleted at cell walls (such as Ni), whilst other elements may be enriched (such as Mo). Such local fluctuations in chemistry are a feature of AM-MPEAs8,36,60.

a bright-field (BF) TEM image, b SAED pattern and c HAADF image of the cellular substructures and (c1–c5) EDXS element distribution maps of (c). Reproduced from ref. 36.

In another example, this time for a N-doped CoCrFeNi alloy prepared by LPBF, the alloy microstructure is revealed in Fig. 9. What may be observed is once again, a cellular substructure at the micron/sub-micron level. In addition, a high density of dislocations may be observed within such cellular structures (Fig. 9c). Once again, EDXS mapping reveals elemental segregation across cell walls and local chemistry fluctuation within cells (in this case, for Cr). Such a high dislocation density and cellular structures effectively also contribute to the presence of residual stress, and a refined grain size (where in many cases, the conventional concept of grain size is superseded by the cellular structures)35.

a Bright field (BF) STEM images of the dislocation cell structure from edge-on orientation with b EDS-line scan results, and c dislocation cell structure from end-on orientation with EDS elemental mapping. Reported from ref. 35.

In an additional example for the LPBF prepared CoCrFeMnNiNbx alloy, the microstructure imaged using scanning electron microscopy (in backscattered electron mode) is seen in Fig. 10 for the case of LPBF-CoCrFeMnNiNb0.15. What can be observed is a complex microstructure in terms of phase / feature distribution. In addition, the EDXS mapping reveals elemental segregation of Nb12.

a SEM image showing the general morphology, b higher magnification image of (a), accompanied by EDXS mapping results (b1, b2) for Cr and Nb, respectively. Adapted from ref. 12.

A higher magnification investigation of the same LPBF-CoCrFeMnNiNb0.15. alloy from Fig. 10, is revealed in Fig. 11. What is observed in the montage of images is features that span the micrometer to atomic length scale, including fine phases within cells of segregated composition, and with such fine phases having fluctuations in chemical composition. Whilst these multi-scale structures are nowadays considered typical of MPEAs (inclusive of HEAs and solute-rich MPEAs), the role of such multi-scale microstructures of diverse local chemistry is not well understood in terms of fundamental impact on localised corrosion and dissolution. There is a clear need for future work to probe corrosion initiation and propagation at these length scales.

a TEM image showing the cell structure and the Laves phase, b bright-field of the Laves phase, c HRTEM image of the marked region in (b), d, e FFT/IFFT results of the marked region in (c), f SAED pattern of the Laves phase. Adapted from ref. 12.

For the study in question12, an observation of the work is that with increasing Nb content (whereby Figs. 10 and 11 reveal the microstructure of the alloy with the highest Nb concentration), the general corrosion resistance and the pitting resistance of the MPEA improved—posited to be due to the grain refinement and modifications of the passive film. Both such mechanistic postulates, however, were not quantified, and do not capture the complexity of the microstructure in question—again indicating that there is a paucity of mechanistic understanding to address across the field. Looking at all of the above representative micrographs, and important general observation is the prevalence of heterogeneous microstructure with 3D dislocation cells inside each grain. There are also micro-segregation cells that inherently form during additive manufacturing, due to cellular solidification. Such features can serve as pathways for rapid diffusion path for elements (including, passivating elements such as Cr and Mo) possibly enhancing the passivity of AM-MPEAs. A mechanism for this would be the possibility that higher fractions of passivating oxides (i.e. Cr2O3 may be integrated into the passive film35). Consequently, the rate controlling steps for corrosion resistance in AM-MPEAs could be determined by critical features of the microstructure, and mobility/transport of species.

Another facet that is evident from the review herein is that there is a prevalence of previously unreported phases that evolve in AM-MPEAs (and indeed, in MPEAs more generally). It is uncommon in conventional (ingot metallurgy/cast) alloys to observe an ordered B2 compound. This is also due to the lack of thermodynamic data (including CALPHAD analysis) in these concentrated regions. As a result, phase identification and microstructural characterisation in AM-MPEAs will remain an important facet to understanding their properties and performance. This is also because if different phases (including phases formed but also phase fractions) occur for AM-MPEAs, the comparison with conventional (as cast) counterparts becomes somewhat less relevant in property determination.

The present review reflects a synopsis for an emerging field that has to date only received limited (but rapidly growing) attention. The individual fields of AM and MPEAs are two of the most dynamic fields in all of materials science (and most certainly, in the domain of structural materials) at present. Undoubtedly, research regarding the production of MPEAs via AM will continue to be pursued. This review has clearly identified that MPEAs can be readily produced by AM, including the production of large specimens in their net-shape, and the production by blended powders. As new alloys are explored and the field of AM-MPEAs grows, future research in the context of corrosion will be required. Some important areas for future research should consider:

-

Advanced electrochemical analysis. This should include closer inspection of passive behaviour. Such testing could include methods such as in-line atomic emission spectro-electrochemistry, and example of which is seen at ref. 67.

-

Exploration of alloy re-passivation, through cyclic polarisation testing, or scratch testing (that may involve physical or electrochemical scratching).

-

The reportage of quantitative properties from any testing, to continue to contribute towards the development of a database of AM-MPEA performance—ultimately permitting data science or machine learning approaches to supplement mechanistic studies.

-

Ongoing microstructural analysis in combination to corrosion testing.

-

In-situ analyses, be it local electrochemical probing, or in-situ observation of alloy dissolution at the appropriate length scale. Direct observation is possible through approaches such as in-situ microscopy, quasi in-situ electron microscopy, and liquid cell transmission electron microscopy68.

-

High-throughput synthesis in combination to corrosion testing. Some AM techniques such as DED allow for combinatorial deposition of alloy “libraries” via on-the-fly alloying from elemental powders, and systematic screening of pseudo-binary or pseudo-ternary phase diagrams. Automatization and parallelisation of corrosion testing on such libraries would accelerate the documentation and screening of AM-MPEAs towards faster identification of promising alloy candidates with superior corrosion resistance69,70,71,72.

Summary

This critical review underscores that the corrosion behaviour of additively manufactured multi-principal element alloys (AM-MPEAs) is governed by the interplay between compositional complexity and process-induced microstructural features. While AM unlocks the potential for fabricating complex, net-shape MPEAs with refined microstructures and unique phases, the resultant corrosion performance is far from universally predictable. The synthesis of over 50 studies reveals emerging patterns - particularly the frequent reduction in passive current density compared to conventionally processed alloy counterparts - yet highlights a field still in its infancy. Variations in processing parameters, alloy composition, and post-treatment significantly influence passivity, pitting resistance, and passive film stability, though the accompanying mechanisms remain largely speculative and underexplored. The path forward demands more rigorous mechanistic investigations, advanced electrochemical characterisation, and microstructural analysis including at the sub-micron scale. Open-access datasets compiled herein lay the foundation for data-driven approaches, including machine learning, to accelerate understanding and alloy design. As AM-MPEAs transition from laboratory to industrial materials, rationalising their corrosion behaviour will remain pivotal to realising their full potential across marine, energy, and aerospace sectors.

Data availability

The datasets generated during the current study are not publicly available as they form part of an ongoing research project but are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

References

Birbilis, N., Choudhary, S., Scully, J. & Taheri, M. A perspective on corrosion of multi-principal element alloys. npj Mater. Degrad. 5, 14 (2021).

Gorsse, S., Couzinié, J.-P. & Miracle, D. B. From high-entropy alloys to complex concentrated alloys. Comptes Rendus Phys. 19, 721–736 (2018).

Miracle, D. B. & Senkov, O. N. A critical review of high entropy alloys and related concepts. Acta Mater. 122, 448–511 (2017).

Miracle, D. & Spanos, G. Defining pathways for realizing the revolutionary potential of high entropy alloys: a TMS accelerator study. The Minerals, Metals & Materials Society (TMS) (2021).

Li, Z., Zeng, Z., Tan, R., Taheri, M. & Birbilis, N. A database of mechanical properties for multi principal element alloys. Chem. Data Collect. 47, 101068 (2023).

Poletti, M. G. & Battezzati, L. Electronic and thermodynamic criteria for the occurrence of high entropy alloys in metallic systems. Acta Mater. 75, 297–306 (2014).

Yeh, J. W. et al. Nanostructured high-entropy alloys with multiple principal elements: novel alloy design concepts and outcomes. Adv. Eng. Mater. 6, 299–303 (2004).

Yamanaka, K. et al. Corrosion mechanism of an equimolar AlCoCrFeNi high-entropy alloy additively manufactured by electron beam melting. npj Mater. Degrad. 4, 24 (2020).

Fujieda, T. et al. Mechanical and corrosion properties of CoCrFeNiTi-based high-entropy alloy additive manufactured using selective laser melting. Addit. Manuf. 25, 412–420 (2019).

Gianelle, M. et al. A novel ceramic derived processing route for multi-principal element alloys. Mater. Sci. Eng. A 793, 139892 (2020).

Shao, G. et al. A Study of the microstructure and mechanical and electrochemical properties of CoCrFeNi high-entropy alloys additive-manufactured using laser metal deposition. Coatings 13, 1583 (2023).

Zhang, Z. et al. Clarify the role of Nb alloying on passive film and corrosion behavior of CoCrFeMnNi high entropy alloy fabricated by laser powder bed fusion. Corros. Sci. 224, 111510 (2023).

Li, R., Kong, D., He, K., Zhou, Y. & Dong, C. Improved passivation ability via tuning dislocation cell substructures for FeCoCrNiMn high-entropy alloy fabricated by laser powder bed fusion. Appl. Surf. Sci. 621, 156856 (2023).

Armstrong, M., Mehrabi, H. & Naveed, N. An overview of modern metal additive manufacturing technology. J. Manuf. Process. 84, 1001–1029 (2022).

Qiu, Y., Gibson, M., Fraser, H. & Birbilis, N. Corrosion characteristics of high entropy alloys. Mater. Sci. Technol. 31, 1235–1243 (2015).

Qiu, Y., Thomas, S., Gibson, M. A., Fraser, H. L. & Birbilis, N. Corrosion of high entropy alloys. npj Mater. Degrad. 1, 15 (2017).

Shi, Y., Yang, B. & Liaw, P. K. Corrosion-resistant high-entropy alloys: a review. Metals 7, 43 (2017).

Nascimento, C. B., Donatus, U., Ríos, C. T., Oliveira, M. C. L. d & Antunes, R. A. A review on corrosion of high entropy alloys: exploring the interplay between corrosion properties, alloy composition, passive film stability and materials selection. Mater. Res. 25, e20210442 (2022).

Sur, D. et al. An experimental high-throughput to high-fidelity study towards discovering al–cr containing corrosion-resistant compositionally complex alloys. High. Entropy Alloy. Mater. 1, 336–353 (2023).

Blades, W. H. et al. High-throughput aqueous passivation behavior of thin-film vs. bulk multi-principal element alloys in sulfuric acid. Corros. Sci. 236, 112261 (2024).

Sur, D. et al. Investigating the synergistic benefits of Al on Cr (III) in the passive films of FeCoNi-Cr-Al CCAs in sulfuric acid. Electrochim. Acta 513, 145523 (2025).

Ghorbani, M. Current progress in aqueous corrosion of multi-principal element alloys. Metal. Mater. 55, 2571–2588 (2024).

Birbilis, N. et al. Multi principal element alloy (MPEA) corrosion database. Mendeley Data 1 (2024).

Anber, E. A. et al. Oxidation resistance of Al-containing refractory high-entropy alloys. Scr. Mater. 244, 115997 (2024).

Moghaddam, A. O., Shaburova, N. A., Samodurova, M. N., Abdollahzadeh, A. & Trofimov, E. A. Additive manufacturing of high entropy alloys: a practical review. J. Mater. Sci. Technol. 77, 131–162 (2021).

Zhang, W., Chabok, A., Kooi, B. J. & Pei, Y. Additive manufactured high entropy alloys: a review of the microstructure and properties. Mater. Des. 220, 110875 (2022).

Sander, G. et al. Corrosion of additively manufactured alloys: a review. Corrosion 74, 1318–1350 (2018).

Gordon, J. V. et al. Defect structure process maps for laser powder bed fusion additive manufacturing. Addit. Manuf. 36, 101552 (2020).

Kong, D., Dong, C., Ni, X. & Li, X. Corrosion of metallic materials fabricated by selective laser melting. npj Mater. Degrad. 3, 24 (2019).

Ghoncheh, M., Shahriari, A., Birbilis, N. & Mohammadi, M. Process-microstructure-corrosion of additively manufactured steels: a review. Crit. Rev. Solid State Mater. Sci. 49, 607–717 (2024).

Revilla, R. I., Verkens, D., Rubben, T. & De Graeve, I. Corrosion and corrosion protection of additively manufactured aluminium alloys—A critical review. Materials 13, 4804 (2020).

Mehta, S., Jha, S. & Liang, H. Corrosion of nickel-based alloys fabricated through additive manufacturing: a review. Prog. Addit. Manuf. 7, 1257–1273 (2022).

Sen-Britain, S. et al. Critical role of slags in pitting corrosion of additively manufactured stainless steel in simulated seawater. Nat. Commun. 15, 867 (2024).

Sprouster, D. J. et al. Dislocation microstructure and its influence on corrosion behavior in laser additively manufactured 316L stainless steel. Addit. Manuf. 47, 102263 (2021).

Zhou, R. et al. 3D printed N-doped CoCrFeNi high entropy alloy with more than doubled corrosion resistance in dilute sulphuric acid. npj Mater. Degrad. 7, 8 (2023).

Chen, X. et al. CoCrFeNiMo0.2 high entropy alloy with excellent mechanical properties and corrosion resistance prepared by laser-powder bed fusion. Intermetallics 163, 108082 (2023).

DelVecchio, E. et al. Metastable cellular structures govern localized corrosion damage development in additive manufactured stainless steel. npj Mater. Degrad. 8, 45 (2024).

Gharbi, O. et al. On the corrosion of additively manufactured aluminium alloy AA2024 prepared by selective laser melting. Corros. Sci. 143, 93–106 (2018).

Gharbi, O. et al. Microstructure and corrosion evolution of additively manufactured aluminium alloy AA7075 as a function of ageing. npj Mater. Degrad. 3, 40 (2019).

Sopcisak, J. J. et al. Improving the pitting corrosion performance of additively manufactured 316L steel via optimized selective laser melting processing parameters. JOM 74, 1719–1729 (2022).

Trelewicz, J. R., Halada, G. P., Donaldson, O. K. & Manogharan, G. Microstructure and corrosion resistance of laser additively manufactured 316L stainless steel. JOM 68, 850–859 (2016).

Das, P., Nandan, R. & Pandey, P. M. A review on corrosion properties of high entropy alloys fabricated by additive manufacturing. Trans. Indian Inst. Met. 75, 2465–2476 (2022).

Ghorbani, M., Birbilis, N., & Laleh, M., Additively manufactured multi principal element alloy corrosion database. Mendeley Data 3 (2025).

Martin, P. et al. HEAPS: A user-friendly tool for the design and exploration of high-entropy alloys based on semi-empirical parameters. Comput. Phys. Commun. 278, 108398 (2022).

Dada, M. et al. The comparative study of the microstructural and corrosion behaviour of laser-deposited high entropy alloys. J. Alloy. Compd. 866, 158777 (2021).

Niu, P. D. et al. Microstructures and properties of an equimolar AlCoCrFeNi high entropy alloy printed by selective laser melting. Intermetallics 104, 24–32 (2019).

Ren, J. et al. Corrosion behavior of selectively laser melted CoCrFeMnNi high entropy alloy. Metals 9, 1029 (2019).

Wang, Y. et al. Effect of aging on corrosion resistance of (FeCoNi)86Al7Ti7 high entropy alloys. Corros. Sci. 227, 111717 (2024).

Luo, W. et al. Effect of volumetric energy density on the mechanical properties and corrosion resistance of laser-additive-manufactured AlCoCrFeNi2. 1 high-entropy alloys. J. Alloy. Compd. 1010, 178032 (2025).

Shittu, J. et al. Tribo-corrosion response of additively manufactured high-entropy alloy. npj Mater. Degrad. 5, 31 (2021).

Xu, Z. et al. Corrosion resistance enhancement of CoCrFeMnNi high-entropy alloy fabricated by additive manufacturing. Corros. Sci. 177, 108954 (2020).

Ralston, K. & Birbilis, N. Effect of grain size on corrosion: a review. Corrosion 66, 075005–075013 (2010).

Zhou, Z. et al. Laser additively manufacturing of Al0.5CoCrFeNiTi0.5 high-entropy alloys with increased resistances to corrosion 3.5% NaCl and oxidation at 1000 °C. J. Mater. Sci. 58, 10148–10165 (2023).

Malatji, N., Popoola, A. P. I., Lengopeng, T. & Pityana, S. Tribological and corrosion properties of laser additive manufactured AlCrFeNiCu high entropy alloy. Mater. Today. Proc. 28, 944–948 (2020).

Du, L. et al. Effect of laser energy density on microstructures and properties of additively manufactured AlCoCrFeNi2.1 eutectic high-entropy alloy. Acta Metall. Sin. 38, 233–244 (2025).

Cheng, H. et al. Tuning the microstructure to improve corrosion resistance of additive manufacturing high-entropy alloy in proton exchange membrane fuel cells environment. Corros. Sci. 213, 110969 (2023).

Melia, M. A. et al. Mechanical and corrosion properties of additively manufactured CoCrFeMnNi high entropy alloy. Addit. Manuf. 29, 100833 (2019).

Wang, R., Zhang, K., Davies, C. & Wu, X. Evolution of microstructure, mechanical and corrosion properties of AlCoCrFeNi high-entropy alloy prepared by direct laser fabrication. J. Alloy. Compd. 694, 971–981 (2017).

Chen, L. et al. Enhancing mechanical properties and electrochemical behavior of equiatomic FeNiCoCr high-entropy alloy through sintering and hot isostatic pressing for binder jet 3D printing. Addit. Manuf. 81, 103999 (2024).

Zhang, J. et al. Superior corrosion resistance and its origins in an additively manufactured Co-Cr-Ni-Al-Ti high-entropy alloy with nano-lamellar precipitates. J. Mater. Sci. Technol. 231, 164–179 (2025).

Liu, Z., Tiannan, M., Jiawei, L. & Zou, T. Regulating microstructure, mechanical properties and corrosion resistance of laser direct energy deposited Al0.5Mn0.5CoCrFeNi high-entropy alloy by annealing heat treatment. Virtual Phys. Prototyp. 20, e2458656 (2025).

Xu, Z. et al. Fabrication of porous CoCrFeMnNi high entropy alloy using binder jetting additive manufacturing. Addit. Manuf. 35, 101441 (2020).

Chen, B. Progress in additive manufacturing of high-entropy alloys. Materials 17, 5917 (2024).

Qiu, X. Microstructure and corrosion properties of Al2CrFeCoxCuNiTi high entropy alloys prepared by additive manufacturing. J. Alloy. Compd. 887, 161422 (2021).

Malatji, N., Kanyane, L. R., & Shongwe, M. B. Tribological and electrochemical performance of AlCrFeNiCuTix high entropy alloy fabricated via laser additive manufacturing. In Proceedings of the 8th International Conference on Manufacturing, Material and Metallurgical Engineering (ICMMME) 2024 (Cham: Springer Nature Switzerland, 2025).

Joseph, J. et al. Comparative study of the microstructures and mechanical properties of direct laser fabricated and arc-melted AlxCoCrFeNi high entropy alloys. Mater. Sci. Eng. A 633, 184–193 (2015).

Xie, C., Han, J., Sun, F. & Ogle, K. Deciphering the role of alloying elements in spontaneous passivation by element-resolved electrochemistry: from pure metals to equiatomic CoCrFeNi. Electrochim. Acta 526, 146177 (2025).

Zhou, Z. et al. In situ electron microscopy: atomic-scale dynamics of metal oxidation and corrosion. npj Mater. Degrad. 9, 28 (2025).

Ribeiro, B. L. et al. High-throughput screening of MoNbTaW-based refractory high-entropy alloys through direct energy deposition in-situ alloying. Mater. Charact. 217, 114346 (2024).

Liu, S., Grohol, C. M. & Shin, Y. C. High throughput synthesis of CoCrFeNiTi high entropy alloys via directed energy deposition. J. Alloy. Compd. 916, 165469 (2022).

Dobbelstein, H., Thiele, M., Gurevich, E. L., George, E. P. & Ostendorf, A. Direct metal deposition of refractory high entropy alloy MoNbTaW. Phys. Proc. 83, 624–633 (2016).

Wang, J., Wang, Y., Su, Y. & Shi, J. Evaluation of in-situ alloyed Inconel 625 from elemental powders by laser directed energy deposition. Mater. Sci. Eng. A 830, 142296 (2022).

Kuwabara, K. et al. Mechanical and corrosion properties of AlCoCrFeNi high-entropy alloy fabricated with selective electron beam melting. Addit. Manuf. 23, 264–271 (2018).

Peng, H., Lin, Z., Li, R., Niu, P. & Zhang, Z. Corrosion behavior of an equiatomic CoCrFeMnNi high-entropy alloy-a comparison between selective laser melting and cast. Front. Mater. 7, 244 (2020).

Thapliyal, S. et al. Damage-tolerant, corrosion-resistant high entropy alloy with high strength and ductility by laser powder bed fusion additive manufacturing. Addit. Manuf. 36, 101455 (2020).

Tong, Z. et al. Achieving excellent wear and corrosion properties in laser additive manufactured CrMnFeCoNi high-entropy alloy by laser shock peening. Surf. Coat. Technol. 422, 127504 (2021).

Savinov, R. & Shi, J. Microstructure, mechanical properties, and corrosion performance of additively manufactured CoCrFeMnNi high-entropy alloy before and after heat treatment. Mater. Sci. Addit. Manuf. 2, 42 (2023).

Zhang, C. et al. Improved corrosion resistance of laser melting deposited CoCrFeNi-series high-entropy alloys by Al addition. Corros. Sci. 225, 111599 (2023).

Xv, T. et al. Effect of melting current on microstructure, mechanical, and corrosion properties of wire arc additive non-equimolar FeCrNiMnCuSi high-entropy alloys. J. Mater. Sci. 60, 5153–5176 (2025).

Acknowledgements

Financial support from the Office of Naval Research under the contract ONR: N00014-17-1-2807 with Dr. David Shifler and Dr. Clint Novotny as program officers is gratefully acknowledged. MLT acknowledges support from the Office of Naval Research MURI Program under the contract N00014-20-1- 2368, with Dr. David Shifler.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Marzie Ghorbani: Writing - Original Draft, Data curation, Writing - Review & Editing, Formal analysis. Majid Laleh: Review & Editing, Oumaima Gharbi: Review & Editing, Marie A. Charpagne: Review & Editing, Hamish L. Fraser: Review & Editing, Rajeev K. Gupta: Review & Editing, Mitra L. Taheri: Review & Editing, Nick Birbilis: Writing - Original Draft, Data curation, Writing - Review & Editing, Supervision, Project administration.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare that there are no competing or conflicts of interests. Professor Nick Birbilis is Editor-in-Chief of npj Materials Degradation but was not involved in the review or editorial decision process for this manuscript. The remaining authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Ghorbani, M., Laleh, M., Gharbi, O. et al. Aqueous corrosion of additively manufactured multi principal element alloys: a critical review. npj Mater Degrad 9, 159 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41529-025-00701-8

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41529-025-00701-8