Abstract

Inconel 718 Ni-based polycrystalline superalloys exhibit excellent mechanical properties, while the type and nature of the grain boundaries are important for their corrosive properties. The effect of grain boundaries on initial oxidation is decisive for degradation, and the conventional method has difficulty revealing nanoscale grain boundaries with different angles. Atomic-scale initial oxidation on different boundaries in Inconel 718 alloys was systematically investigated by in situ environmental transmission electron microscopy (ETEM) with high spatial and temporal resolution. This study reveals the mechanism of intergranular oxidation in polycrystalline alloys and provides a new idea for improving the oxidation resistance of polycrystalline materials.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

The Inconel 718 Ni-based superalloy, one of the most utilised high-temperature superalloys, has been widely used extensively in the gas turbine, aeroengine, spacecraft and nuclear reactor industries due to its excellent high-temperature mechanical properties and good creep resistance1,2,3,4,5. In general, the Inconel 718 superalloy has good oxidation resistance and corrosion resistance below 650 °C6. An elevated working temperature and prolonged service time are increasingly needed with the development of modern industry. Inconel 718 superalloys are sensitive to oxygen at both high and low temperatures. Severe oxidation of short-term alloys during service can lead to premature failure at elevated temperatures, for example, in turbine discs. Long-term exposure also induces severe oxidation even at low temperatures, such as in nuclear applications.

Grain boundaries (GBs), as defects, are basic structures in polycrystalline alloys. The GBs in the alloy enhance the diffusion of alloying elements and oxygen atoms, which are preferential diffusion channels7. Since the diffusion rate of external oxygen atoms at the grain boundary is faster than that inside the grain, metal oxides are first formed at the grain boundary, which is called intergranular oxidation. The structure of the GBs in alloys is an important factor affecting the diffusion rate of solute atoms and the intergranular oxidation properties8,9,10. In general, intergranular oxidation is often the root cause of stress corrosion cracking in materials11,12,13, this is because the intergranular brittle oxides provide a way for the material to crack, which leads to a decrease in mechanical properties14. Therefore, it is very important to understand the intergranular oxidation behaviour of polycrystalline Inconel 718 superalloys and the mass transport mechanism of elements at different GBs.

The thickness, morphology and preference of the oxide layers were affected by the GBs for most of the component elements. Multilayered oxides usually form in long-term oxidised Inconel 718 superalloys at high temperatures according to the oxidation time, and some layers act as important protective agents for the alloy. In most cases, the outer layer is a NbCrOx-rich layer with voids and microcracks, the middle layer usually contains only a discontinuous thin layer of Al2O3 within a limited oxidation time, and the inner layer is mainly a combination of complex carbides15. The most important protective oxide Cr2O3 layer is the decisive oxide scale, and its thickness continuously determines its corrosion resistance. Understanding the boundary-affected Cr2O3 layer formation mechanism is key to its application. A previous study revealed that Cr scales are formed mainly by diffusion along GBs at high temperatures16. Other oxide layers are also affected by GBs, and long-term exposure of the Inconel 718 superalloy at high temperatures causes NbC to decompose on the surface and generate a large amount of Nb2O5, especially at the GBs17. Other important oxides, such as Al oxide α-Al2O318,19 and Ti oxide rutile-TiO220, in the GBs of oxidised alloys are also severely affected.

Furthermore, it has been reported that different kinds of GBs exhibit different oxidation preferences and speeds. Deep intergranular oxidation in Ni-based superalloys has been reported, and oxidation preferentially occurs randomly along high-angle GBs21. Twin boundaries can effectively slow the propagation of intergranular corrosion cracks by reducing the number of potential initiation sites22. Lin investigated the relationship between grain boundary diffusivity and GB characteristics and reported that the diffusion activation energy of ordered GBs is greater than that of disordered GBs23. Many intergranular oxidation phenomena related to Ni-based superalloys have been reported in previous articles, but the effects of different types of GBs on the oxidation behaviour have not been revealed in these studies due to the nanoscale of some GBs.

However, some issues at the nanoscale and atomic scale, such as the effects of the grain boundary structure or grain boundary energy on preferential oxidation, are still under debate. The effects of temperature on the oxidation of GBs provide experimental data for preparing polycrystalline alloys. These studies are based on ex situ oxidation studies of bulk samples, which cannot provide a full oxidation scene from the adsorption of oxygen to the formation of an oxide layer. Environmental transmission electron microscopy (ETEM) with spherical aberration correction can be used to directly and dynamically observe the reaction process of materials at the nanoscale or even the atomic scale24, which is helpful for understanding the role of different GBs in the full oxidation process and provides a full scene for oxidation.

In this work, the initial oxidation process of Inconel 718 superalloys was studied by in situ ETEM at high temperatures to reveal the effect of the grain boundary energy on the oxidation resistance. The main factors affecting the initial oxidation behaviour of different types of GBs were determined by observing the microstructure and elemental evolution of the GBs during the oxidation process, and the mechanism of intergranular oxidation was revealed. The purpose of this study is to provide a reference for the structural design of antioxidant polycrystalline superalloys.

Results

Microstructure and boundary extraction

The Inconel 718 alloy used in the experiment is a polycrystalline alloy, and the EBSD orientation map that was chosen for cutting is shown in Fig. 1a. Three different locations of GBs at b, c and d are selected in the figure, and local magnified images of these three regions are shown in Fig. 1b1–d1. Owing to the high symmetry of the face-centred cubic structure in Inconel 718, the angle adjacent to 45o can be attributed to the high-angle boundary. The orientation map reveals that the grain boundary of region b is a high-angle grain boundary, the grain boundary of region c is a low-angle grain boundary, and the grain boundary of region d is a twin boundary. To clarify the difference in the initial oxidation behaviour of different types of GBs, FIB was used to extract TEM lamellas from the surfaces of parallel samples in these three regions. The HAADF images of the extracted samples are shown in Fig. 1b2–d2. The grain boundary angle can be obtained by calculating the orientation difference between adjacent grains via OIM analysis software (V2.1.5). The final angle obtained for the grain boundary in region b is approximately 36.2°, which is a high-angle grain boundary, and the angle of the grain boundary in region c is approximately 11.6°, which is a low-angle grain boundary, which is consistent with that observed in the orientation map. The grain boundary in Fig. 1d1 is a typical twin boundary, which is a 2D boundary and was verified by TEM data. The HADDF images and key element distributions of the original samples are shown in Fig. S1 of the supplementary file. It can be observed that, whether at a high-angle or a low-angle grain boundary, the elemental content at the boundary is essentially identical to that within the grain, with elemental segregation at the boundary being negligible.

Oxidation of high-angle grain boundary

The thermal oxidation process on high-angle grain boundary (region b in Fig. 1a) was carried out by in situ ETEM, and typical images from 20 °C to 800 °C with a constant oxygen pressure of 0.5 mbar are shown in Fig. 2. The heating was started from 300 °C, and the heating step was 50 °C. The subsequent experiments were carried out under the same conditions. The detailed thermal oxidation process can be found in Supplementary Movie 1. As shown in Fig. 2a, the original sample contains two grains, with the grain boundary in the middle clearly visible, and there is a line defect shown by the red arrow inside the grain. The internal stresses and defects on the sample surface caused by FIB milling were repaired by thermal annealing at 350 °C. There is no obvious change in the sample when the heating temperature is below 400 °C. A slight degree of oxidation gradually appeared at the edge of the sample due to the increased temperature. When the temperature was increased to 550 °C, an oxide layer appeared at the oxidation front at the edge of the sample, as shown by the red circle in Fig. 2g, and the growth rate of the oxide was relatively low. The oxide grew rapidly inwards along the grain boundary at 700 °C, and preferential oxidation at the grain boundary occurred, as shown by the red circle in Fig. 2j. When the oxidation agent diffused to the intersection of the grain boundary and line defects, it tended to spread to the defects. As the temperature continues to increase, the interior of the grains is gradually oxidised. The complete oxidation of the sample occurred at 800 °C, and oxide aggregates appeared inside the grains, as shown by the red circle in Fig. 2l. The EELS spectra of the grain edge and grain boundary of the sample from 20 °C to 800 °C are shown in Fig. 2m, n. The acquisition positions for the EELS spectrum are indicated by the square markers in the TEM images. The strength of the L3 and L2 edges is calculated by integration, and the strength ratio (hereinafter referred to as the L3/L2 ratio) can be used to further distinguish the valence states of the elements. Studies have shown that for Cr, Fe and other elements, with the increase of oxidation valence, the L3/L2 ratio increases25,26. The valence states of Cr and Fe increase with the increase of temperature. The contents of O and Cr at the grain boundary were significantly greater than those at the grain at 700 °C. The valence states of Cr and Fe increased with increasing temperature. When the temperature increased to 800 °C, all the Fe ions were transferred to Fe3+.

a–l Typical TEM images of the in situ oxidation process on the alloy at high-angle grain boundary from 20 °C to 800 °C, the detailed data can be found in Supplementary Movie 1. m,n EELS spectra of the grain and grain boundary.

According to the series of TEM images obtained during in situ thermal oxidation, obvious structural changes can be found at the four typical temperatures, which clearly vary, and the elemental distributions were characterised at the temperatures shown in Fig. 3. The four typical oxidation conditions are as follows: no oxidation ( < 400 °C), obvious oxidation at the edge ( > 550 °C), preferential oxidation at the grain boundary ( > 700 °C) and critical oxidation in the grain ( > 800 °C). The HAADF images and element distribution maps of typical regions under these four conditions are shown in Fig. 3. All the element distribution mappings can be seen in Fig. S2 of the supplementary file. The data indicate that the elements are uniformly distributed within the samples at 400 °C without any obvious segregation (Fig. 3a) before oxidation. The results of the quantitative EDS analysis of the line distribution also reveal that the elemental contents at the grain boundary and inside the grains are nearly equal. The Ni content of the original alloy is 50%, the Cr content is 20%, the Fe content is 18%, and the Nb content is 3%. At this point, a small amount of enriched oxygen appeared at the edge of the sample. The content variation after initial oxidation only occurs at the sample edge at 550 °C. Compared with that at 400 °C, the oxygen content at the edge of the sample increases at 550 °C. The elemental distribution inside the sample after initial oxidation at 550 °C did not change significantly, and the elemental content also remained the same as that at 400 °C (Fig. 3b). The oxide layer at this temperature has a double-layered oxide structure at the edge of the sample, with a Ni/Fe-rich outer layer and a Cr-rich inner layer, and aggregates of O, Cr and Nb also appear at the grain boundary. After oxidation at 700 °C, obvious oxidation can be observed at the edge and grain boundary of the sample at this temperature, and substantial changes in the microstructure and elemental distribution are observed, as shown in Fig. 3c. A high quantity of Fe was detected at the edge of the sample, and the contents of Cr and Nb at the grain boundary increased significantly compared with those at other temperatures, reaching 40% and 12%, respectively. The contents of Ni and Fe at the grain boundary, however, decreased significantly to 14% and 13%, respectively. The contrast of the HAADF images indicates the composition of the sample, which is proportional to the square of the atomic number27, that is, a bright region means that the region has more heavy elements than its adjacent regions. The weak contrast at the grain boundary in Fig. 3c indicates that the average atomic mass in this area is low compared with that in its adjacent region. This phenomenon indicates that oxidation promotes the diffusion of Cr and Nb to form oxides at the grain boundary. Diffusion of Ni from the grain boundary to the interior of the grains also occurs at the same time, and this reverse diffusion leads to an increase in the Ni content at the grains of up to 57% compared with that at the grain boundary (14%). After complete oxidation of the sample at 800 °C, large quantities of Fe-rich oxides formed and extruded from the edge of the sample, and the Fe concentration inside the sample decreased from the original 18 to 10%, indicating that Fe diffusion occurred from the inner alloy to the sample edge during the oxidation process. At this point, the oxygen covered the full surface of the sample, and many Ni aggregation zones appeared inside the grains. Interestingly, the Ni content at the grain boundary increased to 35%, whereas the Cr and Nb contents decreased to 30% and 7%, respectively. This elemental variation can be attributed to the fast oxidation of the grains at this time, where many oxygen atoms occupy the lattice positions of the grains, and the excess Ni atoms rediffuse to the grain boundary, leading to a decrease in the relative concentrations of Cr and Nb.

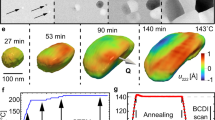

The 700 °C temperature is a particular temperature under which high-angle grain boundary begin to oxidise during our in situ oxidation experiment, and typical TEM images are shown in Fig. 4. In this study, the average oxidation rate was defined by the average rate at which oxygen diffuses from the edge of the sample to the inside of the sample in a direction parallel to the sample and continuously reacts to form oxides. The oxidation rate of the grain boundary is significantly greater than that of the other regions on the surface. Oxidation initiated at the sample edge and continued to diffuse internally along the grain boundary. The depth‒time curves of the oxides on the grain boundary and interior grain are compared in Fig. 4h. The oxidation depth of the grain boundary increased linearly in the early stage of oxidation, whereas the oxidation speed of the grains nearly remained stable as the oxidation proceeded from 0 to 24 min. At 700 °C for 24 min, the oxidation depth at the grain boundary reached 415 nm, whereas the maximum oxidation depth at the grain was only 73 nm. This phenomenon indicates preferential oxidation at high-angle grain boundary, and its average oxidation speed (17 nm·min-1) is approximately 5.7 times greater than that at the grain surface (3 nm·min-1), this can be attributed to the fact that the high-angle grain boundary provides preferred diffusion channels for O, and the rapidly formed loose porous Fe3O4, as indicated by the EDS data, accelerates the diffusion of oxygen inwards along the high-angle grain boundary.

a–g Series of time-dependent TEM images of a typical high-angle grain boundary during in situ oxidation in ETEM at 700 °C/0.5 mbar of oxygen. The dashed contour lines indicate the positions of the metal‒oxide interface. h Relationship between the oxidation depth and time between the grain boundary and interior grain.

Oxidation of low-angle grain boundary

During the oxidation process, the low-angle grain boundary exhibits obvious structural and elemental variation that is markedly different from that occurring in the high-angle grain boundary. Typical TEM images during the in situ thermal oxidation process of the alloy at low-angle grain boundary (region c in Fig. 1a) from 20 °C to 800 °C with a constant oxygen pressure of 0.5 mbar are shown in Fig. 5. The grain boundary was located in the centre of the images indexed by the red arrow and was obvious because of the orientation-induced contrast difference. The crystal structure of the alloy and the grain boundary angle can be determined via selected-area electron diffraction (SAED). The SAED pattern at the grain boundary is shown in Fig. 5b. The selected area contains two grains; thus, two sets of diffractions in the pattern are indexed. The diffraction image shows that the two grains have the same structure, both of which have FCC structures in the [110] plane, indicating that they are low-angle GBs. The full oxidation process can be seen in Supplementary Movie 2. The starting oxidation temperature is similar to that of the high-angle grain boundary alloy, and slight initial oxidation begins from the thin edge of the sample at 400 °C. The dimension of the oxide particles increased gradually with increasing temperature up to 600 °C, with the highest rate. The main oxidation mode of the alloy, however, changes from “outwards growth” to “inwards diffusion” at 700 °C. Since then, the main form of oxidation of the alloy changes from outward oxidation to alloy‒oxide interface oxidation, and then the oxidation continuously migrates inwards with continuous diffusion of oxygen. The oxidation interface after oxidation at 700 °C is shown as the dashed line in Fig. 5j. Unlike the oxidation behaviour of the high-angle grain boundary, the low-angle GBs did not show drastic preferential oxidation, but only a wedge-shaped oxide structure appeared at the grain boundary when oxidised at 750 °C for 4 min. As the oxidation time increased to 14 min, the inwards migration of the alloy‒oxide interface increased significantly, and the interface gradually became smooth from serrated to basically parallel to the edge of the sample, as shown by the red arrow in Fig. 5o. The oxidation phenomenon at 800 °C is similar to that of high-angle grain boundary, where the sample is completely oxidised and the same degree of oxide particle aggregation appears inside the grains, as shown by the red arrow in Fig. 5p.

a–p Typical TEM images of the in situ oxidation process on the alloy at a low-angle grain boundary from 20 °C to 800 °C, the detailed data can be found in Supplementary Movie 2.

The morphology and elemental distributions of the low-angle grain boundary after oxidation at different temperatures are shown in Fig. 6. All the element distribution mappings can be seen in Fig. S3 of the supplementary file. A very small amount of nanoscale Fe oxides initially formed quickly at the edge of the sample at 400 °C, while the elements were uniformly present in the grain at the same time. When the temperature was increased to 550 °C, similar to the oxidation behaviour of the high-angle grain boundary alloy, Fe and Ni oxide began to appear at the edge of the sample. The difference between the oxidation behaviours at high-angle and low-angle boundaries is that no elemental aggregation was found at the low-angle grain boundary. As the temperature increased to 700 °C, there was still no obvious aggregation of Cr at the grain boundary compared with the high-angle boundary. It is interesting to note that preferential oxidation of Nb was also observed at the low-angle grain boundary, which is similar to that which occurred in the high-angle grain boundary. The EDS quantitative analysis of the line distribution reveals that the content of Nb at the grain boundary is 12%, which is much greater than that in the grains. On the other hand, the content of Cr at the grain boundary remains stable, similar to that in the grain. Correspondingly, the contents of Ni and Fe at the low-angle grain boundary appeared to decrease to 40% and 10%, respectively.

Compared with the oxidation behaviour of the high-angle grain boundary after oxidation at 700 °C, the content of Ni did not decrease substantially. This can be attributed to the uniform distribution of Cr and Ni oxides on the grain boundary during oxidation and the lack of obvious aggregation. The diffusion of Ni is passive, and it is prompted or activated by other easily oxidised elements during continuous oxidation-induced movement. The inward migration and concentration decrease of Ni in the deep oxidation zone at the edge of the sample are caused by the oxidation and aggregation of Cr and Nb in this region. A comparison of the oxidation behaviour at high-angle and low-angle GBs revealed that some key elements affect oxidation at different types of GBs. Ni and Cr are two key elements, and there is only a high degree of aggregation of Cr at high-angle grain boundary (40%), which remains uniform at low-angle grain boundary. Unlike the aggregation behaviour of Cr, Ni has a weak oxidation preference at both high- and low-angle GB, which has little effect on its corrosion resistance during initial oxidation.

Oxidation of twin boundary

In polycrystalline alloys, distortions occur due to the irregular arrangement of atoms at GBs, leading to increased free energy in the system. In theory, the level of grain boundary energy is related to the degree of distortion of the atom arrangement on the grain boundary. The energy γ of the low-angle grain boundary mainly depends on the phase difference θ between grains:

where γ0 = Gb/4π(1-υ), depending on the shear modulus G, Burr’s vector b and Poisson’s ratio υ, and A is the integration constant, depending on the atomic misalignment energy of the dislocation centre. Equation (1) shows that the grain boundary energy of the low-angle grain boundary increases with increasing phase difference between the grains. The energy of a high-angle grain boundary is independent of the phase difference, which is essentially a constant value, approximately 0.25 ~ 1.0 J/m228. In comparison, high-angle grain boundary usually has higher grain boundary energies. As a special type of low-energy grain boundary, the colattice twin boundary has a lower grain boundary energy than the high-angle grain boundary and low-angle grain boundary since the atoms on the twin plane are shared by two crystals at the same time.

The oxidation behaviour in the twin boundary (d region in Fig. 1a) is also characterised and analysed, as shown in the typical TEM images in Fig. 7, from 20 °C to 800 °C with a constant oxygen pressure of 0.5 mbar. There was no preferential oxidation at the twin boundary during the oxidation process, and the alloy‒oxide interface remained smooth even at the twin boundary. EDS analysis also revealed that there was no accumulation of Cr or Nb at the twin boundary after oxidation, indicating maximum oxidation resistance among the three kinds of GBs. In general, the lower the energy is, the less prone it is to intergranular corrosion29, which is why the twin boundary has good oxidation resistance.

a–h Typical TEM images of the oxidation process on the alloy with a twin boundary from 20 °C to 800 °C, the detailed data can be found in Supplementary Movie 3. i HAADF image and typical elemental distributions during oxidation at 800 °C.

Oxide characterisation

In situ TEM observation reveals a clear rule: the oxidation behavior and product strongly depend on the oxidation temperature. When the oxidation temperature is low, the main oxidation element is Fe. With the increase in temperature, active elements, such as Al, Cr, and Nb, begin to oxidise on the surface and at the grain boundary. At this time, competitive segregation of different elements will occur on high-angle GBs. This is because the higher interface energy reduces the energy barrier of oxide nucleation, so that a variety of oxidation reactions that may occur thermodynamically can be carried out here. The ordered arrangement of atoms at low-angle GBs provides a low-energy-barrier nucleation site for the selective oxidation of Nb, effectively inhibiting the segregation of other elements and the formation of oxides. In the later stage of the oxidation process, the remaining elements also gradually undergo oxidation reactions. With the injection of a high quantity of oxygen atoms, various elements accumulate on the surface of the sample and form a composite oxide. The main oxides at different temperatures were characterised and analysed as shown in HRTEM analysis and the related fast Fourier transform (FFT) in Fig. 8, and the atomic relationships with the base were also demonstrated. The phase and structure of the oxide can be obtained by measuring the lattice spacing and pinch angle of the oxide, combined with EDS analysis. The atomic relationship models between oxides and matrix were constructed by CrystalMaker software. Fig. 8a-c shows that the initial oxide formed on the surface at 400 °C was Fe3O4 (view direction [101]), and the orientation analysis revealed epitaxial growth within the matrix. With increasing temperature, the nanoscale oxides begin to grow and combine into large oxide particles, and the observed orientation of the oxides still remains in the [101] plane, rotated only in the plane parallel to the matrix (Fig. 8d–f). The growth of Fe3O4 ceased at 700 °C, and a large amount of randomly oriented dense Cr2O3 formed at the alloy‒oxide interface and at the same time, as shown in Fig. 8g–i. When the samples were fully oxidised at 800 °C, high quantities of oxides rich in Fe and Ni could be found on the surface, and they could be assigned to the spinel oxides of NiFe2O4 (Fig. 8j–l).

Discussion

In this study, we investigated the oxidation behaviour of different GBs. The same conclusion can be obtained by repeated in situ characterisation of different GBs. There are several factors that affect oxidation, including thermodynamics, which determines which substance can be oxidized first, and growth kinetics, which determines the oxidation speed or the oxide growth curve. During oxide growth, the component and structure are two additional important factors that affect the oxidation speed and tendency of the material. In the following, we discuss these factors separately.

The diffusion behaviour of elements in multicomponent alloys is an important factor affecting their oxidation resistance. Selective initial oxidation is the driving force for the diffusion of alloying elements, which is mainly controlled by the Gibbs free energy and can be used to reflect the spontaneity and stability of oxide formation in alloys. When the Gibbs free energy of the oxide is calculated, it should be regarded as the process of generating that oxide from the most stable monomer and is therefore calculated on the basis of one mole of monomer. Based on the thermodynamic data, the Gibbs free energy‒temperature diagram of the major oxides in the Ni-based superalloy was calculated via the HSC Chemistry 6.0 software, as shown in Fig. 9. The slope of the straight line in the figure reflects the change in the stability of the oxide with temperature, i.e., a positive slope indicates that the stability increases with increasing temperature. The lower the Gibbs free energy of the oxide is, the greater the ability of the corresponding element to combine with O. Table 1 summarises the detailed information of element enrichment temperature and location. In the actual oxidation process, the surface of Fe was first oxidised at 400 °C, depending on the elemental concentration and ambient temperature. Since the Fe-rich oxide is very loose, Fe atoms can pass through the surface oxide layer and combine with O, resulting in the continuous outwards growth of the oxide. At the same time, O also reacted with Cr at the alloy‒oxide interface through the oxide layer to form Cr2O3. There is a competitive relationship between the growth of Fe, Ni oxides and Cr oxides, which also explains why double-layer oxides appear at 550 °C (Figs. 3b and 6b). With the continuous oxidation of Cr, Cr2O3 in the middle layer acts as a barrier to the diffusion of cations to the surface30,31. Therefore, the outer layer lost the supply of elements, and the growth rate of the oxide was greatly reduced. After that, the oxidation form of the alloy changed to anionic diffusion. At this stage, different types of GBs exhibit different oxidation behaviours. A large amount of Cr and Nb diffused to the high-angle GBs for oxidation, whereas Ni and Fe diffused to both sides of the GBs. From a thermodynamic point of view, this phenomenon can be attributed to the fact that the activity of Ni and Fe is lower than that of Cr and Nb, so they are expelled to reduce the stress caused by the increase in volume during oxide formation12,32. There is no Cr transfer phenomenon at the low-angle GBs, and more reactive Nb oxides are generated. The main reason for this difference is that the high-angle GBs are not well matched with the relatively open disordered structure. Elements diffuse rapidly at the GBs in this structure, so the oxidation and aggregation of elements are more likely to occur at high-angle GBs.

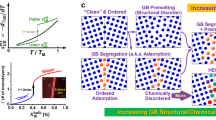

The energy of the grain boundary usually affects the corrosion resistance of the material, which is a key factor in determining the properties of the material33. There is a systematic relationship between the grain boundary energy and the orientation difference between the two grains. According to the different angles and types of GBs, the GB energies corresponding to high-angle GB, low-angle GB, and twin boundary in Fig. 1 are about 0.981, 0.659, and 0.063 J/m2, respectively34. Different oxidation mechanisms can be summarised according to the models shown in Fig. 10. In the initial oxidation stage, outwards oxidation is the dominant mode, and the Fe-rich oxide grows from the surface to the outside due to its fast growth rate. Subsequently, the oxidation pattern changes to inward oxidation, a Cr-rich oxide layer is formed between the outer oxide layer and the matrix, and the alloy-oxide interface continues to move inwards. In the subsequent process, the effect of grain boundary energy on the oxidation behaviour began to gradually reflect. After analysing the in situ TEM images, it can be found that the diffusion rate of oxygen along the high-angle grain boundary is much higher than that inside the grains (Fig. 4). This shows that some conditions provide a fast or easy channel for oxygen diffusion, such as high grain boundary energy, loose structure, or a low diffusion energy barrier. The change of element distribution in the oxidation process shows an obvious dynamical segregation at the grain boundary and shows significantly different behaviour on different types of GBs. The high-angle grain boundary exhibits strong interfacial reactions, and Cr-rich and Nb-rich oxides diffuse rapidly along the grain boundary. In contrast, only slight oxidation with significantly reduced oxidation depth occurred at the low-angle grain boundary, and only active Nb-rich oxides formed at the grain boundary, while no Cr-rich oxides were observed. The twin boundary has the same oxidation behaviour with a smooth alloy-oxide interface as the inner grain does, and there is no interfacial reaction during the oxidation process. The oxidation in different GBs indicates that the higher the grain boundary energy, the stronger the driving force for the segregation of alloying elements. A high-energy grain boundary provides diffusion paths and reaction sites for oxidation, which is the main driving factor of intergranular corrosion of materials. With the decrease of grain boundary energy, the oxidation resistance of the grain boundary is gradually enhanced. Therefore, oxidation resistance in different GB can be listed as follows: twin GB > low-angle GB > high-angle GB. During the oxidation process of polycrystalline materials, the main path of oxygen diffusion into the alloy is along the GBs, especially at low pressures or temperatures. Oxygen has been found to diffuse much more slowly in some special GB than in other types of GBs35. Compared to other regions, nontextured polycrystalline materials contain numerous high-angle GBs with high energy. Oxygen undergoes short-circuit diffusion in large quantities at these high-energy GBs, resulting in high-speed diffusion and oxidation rates at the GBs. Therefore, the anti-oxidation design is not only to increase the proportion of low-energy GBs but also to construct an interconnected low-energy GB network. When oxidation propagates horizontally, the propagation path is effectively blocked once the low-energy GB is encountered. Optimising the structure of the GB network through GB engineering is an effective strategy for retarding the oxidation-induced failure of superalloys.

The migration of elements across different GBs is crucial for the varying oxidation behaviors of the GBs. Fig. 11 shows the demonstration of the migration of elements in the oxidation process on different GBs with different energies. During the initial stage of oxidation, the O atom gradually adsorbs at the edge of the sample, and then, the Fe atoms rapidly diffuse from the inner alloy to the surface and combine with O to form an Fe3O4 oxide layer in a short time. At the same time, O atoms penetrate the inner alloy through the loose pores of the Fe3O4 layer to form Cr2O3 in the intermediate layer. Competitive growth between Cr-rich oxides and Ni-rich oxides occurs, and Ni atoms diffuse faster than Cr atoms do. A sufficient number of thick continuous Cr2O3 layers acts as barriers to the continued outwards diffusion of cations and hinders further oxidation. At this point, the main oxidation mode changes from inwards diffusion to outwards diffusion, and the GBs begin to exhibit different oxidation mechanisms, which are key factors. The O atoms diffuse the fastest at high-angle GBs because they have the highest boundary energy, and severe preferential oxidation occurs. The Gibbs free energy of Ni is lower than that of Cr and Nb, and large amounts of Cr and Nb first migrate to the GBs to form Cr2O3 and Nb2O5 at low temperatures. With increasing temperature, fast diffusion/oxidation of Ni atoms occurs on both sides to reduce the stress caused by the increase in volume during the formation of the oxide. Owing to the low energy of low-angle GBs, only Nb migrates to the GBs to form Nb2O5 during oxidation at low temperatures due to its low Gibbs free energy, and not enough Cr migrates to the GBs at these temperatures. For the lowest energy twin boundary, the alloy‒oxide interface always diffuses inwards parallel to the sample edge. The internal Cr migrated to the alloy‒oxide interface and oxidised, and no accumulation of Cr or Nb was observed at the GBs. Thus, the oxidation activity of the element has a direct relationship with the grain boundary energy; high-angle GBs have a high boundary energy and actively react with oxygen, whereas low-angle GBs have a low grain energy and slowly react with oxygen.

In summary, to determine the corrosion preference of different GBs in polycrystalline alloys, the in situ oxidation behaviour of an Inconel 718 Ni-based superalloy, including high-angle, low-angle and twin GBs, was systematically investigated via environmental transmission electron microscopy. The microstructure evolution and elemental distribution process during oxidation at different GBs were investigated in detail, and the key factors affecting the oxidation resistance of the GBs were elucidated. The findings indicate that the grain boundary energy is the decisive factor affecting the corrosive resistance of a material and is directly related to its angle, and the energy sequence is as follows: high-angle boundary>low-angle boundary>twin boundary. High-angle GBs exhibit high oxidation speeds and normal surfaces and act as the main channels for the inward diffusion of oxygen for intergranular oxidation. The twin boundaries exhibit the best oxidation resistance, followed by the low-angle GBs, and the high-angle GBs have the worst oxidation resistance. After high-temperature oxidation, obvious enrichment of Cr and Nb was observed at the high-angle GBs, while only Nb was enriched at the low-angle GBs, and no element enrichment was observed at the twin GBs. With the decrease of grain boundary energy, the GB gradually exhibits excellent oxidation resistance. A large number of low-energy grain boundary network should be considered in the design of anti-oxidation polycrystalline materials.

Methods

Samples preparation

The material used in this study is an Inconel 718 Ni-based superalloy, and the chemical composition is listed in Table 2. The elemental contents mentioned in this paper are all expressed as atomic percentages. A composite with dimensions of 10 × 10 × 1 mm was taken from the alloy sheet via wire cutting. The sample was mechanically polished after being ground sequentially with 150 to 3000 grit paper and then electrochemically polished in a mixture of 10% HClO4 + 90% C2H5OH, followed by electron back scatter diffraction (EBSD) analysis. EBSD tests were conducted via a field emission scanning electron microscope (FEI Quanta 650) equipped with a detector model EDAX Hikari Camera to obtain information on the types of GBs. Thin samples containing specified GBs were diced via a focused ion beam (FIB) dual-beam system (FEI Helios 600i) and then transferred to a microelectromechanical system (MEMS, Bestronst Co.) heating chip for subsequent transmission electron microscopy (TEM) testing.

In situ ETEM oxidation experiments

In situ oxidation experiments were conducted in an ETEM (FEI Titan) instrument equipped with an objective lens spherical aberration corrector. The ETEM has a maximum accelerating voltage of 300 kV and a spatial resolution of 0.08 nm. High-purity O2 (99.999%) was injected into the ETEM, and the pressure near the sample was controlled at 0.5 mbar via a differential pumping system. At the same time, the sample temperature was controlled from 20 °C to 800 °C via a chip-based heating holder (BestronST Cor.). The sample was maintained at each temperature for approximately 25 min until no further reaction occurred. Electron energy-loss spectroscopy (EELS) was performed via a spectrometer (Gatan GIF 965) with an energy resolution of 0.8 eV to reveal the type and valence of the oxides formed.

Ex situ microstructure and chemical characterisation

For ex situ TEM, a transmission electron microscope (TEM FEI Talos) with an acceleration voltage of 200 kV equipped with an energy dispersive X-ray spectrometer (EDS) system was used to obtain high-angle annular dark field (HAADF) images and local elemental distribution information. Quantitative EDS analysis was performed via the conventional Cliff-Lorimer method, and a parabolic model was used to remove the background. The K series peaks were chosen for O, Ni, Cr, Fe, Al, Ti and Mn, and the L series peaks were chosen for Nb and Mo to analyse the elemental distribution.

Data availability

The relevant data is previously unpublished and is herein are available from the corresponding authors.

References

Wei, X. P. et al. Static recrystallization behavior of Inconel 718 alloy during thermal deformation. J. Wuhan. Univ. Technol. Mater. Sci. Ed. 29, 379–383 (2014).

Kumar, S. et al. Effect of surface nanostructure on tensile behavior of superalloy IN718. Mater. Des. 62, 76–82 (2014).

Wu, X. W., Chandel, R. S., Li, H., Seow, H. P. & Wu, S. C. Induction brazing of inconel 718 to inconel X-750 using Ni-Cr-Si-B amorphous foil. J. Mater. Process. Technol. 104, 34–43 (2000).

Cheng, L. et al. Deformation behavior of hot-rolled IN718 superalloy under plane strain compression at elevated temperature. Mater. Sci. Eng. A 606, 24–30 (2014).

Saravanan, K., Chakravadhanula, V. S. K., Manwatkar, S. K., Murty, S. V. S. N. & Narayanan, P. R. Dynamic strain aging and embrittlement behavior of IN718 during high-temperature deformation. Metall. Mater. Trans. A 51, 5691–5703 (2020).

Sanviemvongsak, T., Monceau, D., Desgranges, C. & Macquaire, B. Intergranular oxidation of Ni-base alloy 718 with a focus on additive manufacturing. Corros. Sci. 170, 108684 (2020).

Schreiber, D. K., Olszta, M. J. & Bruemmer, S. M. Grain boundary depletion and migration during selective oxidation of Cr in a Ni-5Cr binary alloy exposed to high-temperature hydrogenated water. Scr. Mater. 89, 41–44 (2014).

Mayo, W. E. Predicting IGSCC/IGA susceptibility of Ni-Cr-Fe alloys by modeling of grain boundary chromium depletion. Mater. Sci. Eng. A 232, 129–139 (1997).

Mishin, Y., Herzig, C., Bernardini, J. & Gust, W. Grain boundary diffusion: fundamentals to recent developments. Int. Mater. Rev. 42, 155–178 (1997).

Feng, X. Y., Xie, J. Y., Huang, M. Z. & Kuang, W. J. The intergranular oxidation behavior of low-angle grain boundary of alloy 600 in simulated pressurized water reactor primary water. Acta Mater. 224, 117533 (2022).

Capell, B. M. & Was, G. S. Selective internal oxidation as a mechanism for intergranular stress corrosion cracking of Ni-Cr-Fe alloys. Metall. Mater. Trans. A 38, 1244–1259 (2007).

Persaud, S. Y., Korinek, A., Huang, J., Botton, G. A. & Newman, R. C. Internal oxidation of Alloy 600 exposed to hydrogenated steam and the beneficial effects of thermal treatment. Corros. Sci. 86, 108–122 (2014).

Volpe, L., Burke, M. G. & Scenini, F. Oxidation behaviour of solution-annealed and thermally-treated Alloy 690 in low pressure H2-Steam. Corros. Sci. 167, 108514 (2020).

Dugdale, H., Armstrong, D. E. J., Tarleton, E., Roberts, S. G. & Lozano-Perez, S. How oxidized grain boundaries fail. Acta Mater. 61, 4707–4713 (2013).

Geng, L., Na, Y. S. & Park, N. K. Oxidation behavior of Alloy 718 at a high temperature. Mater. Des. 28, 978–981 (2007).

Dressler, M., Nofz, M., Dorfel, I. & Saliwan-Neumann, R. Influence of sol-gel derived alumina coatings on oxide scale growth of nickel-base superalloy Inconel-718. Surf. Coat. Technol. 202, 6095–6102 (2008).

Dressler, M., Nofz, M., Dorfel, I. & Saliwan-Neumann, R. Diffusion of Cr, Fe, and Ti ions from Ni-base alloy Inconel-718 into a transition alumina coating. Thin Solid Films 520, 4344–4349 (2012).

Al-hatab, K. A., Al-bukhaiti, M. A., Krupp, U. & Kantehm, M. Cyclic oxidation behavior of IN 718 superalloy in air at high temperatures. Oxid. Met. 75, 209–228 (2011).

Trindade, V. B., Krupp, U., Wagenhuber, P. E. G., Virkar, Y. M. & Christ, H. J. Studying the role of the alloy-grain-boundary character during oxidation of Ni-base alloys by means of the electron back-scattered diffraction technique. Mater. High. Temp. 22, 207–212 (2005).

Sanviemvongsak, T., Monceau, D. & Macquaire, B. High temperature oxidation of IN 718 manufactured by laser beam melting and electron beam melting: effect of surface topography. Corros. Sci. 141, 127–145 (2018).

Trindade, V. B., Krupp, U., Wagenhuber, P. E. G. & Christ, H. J. Oxidation mechanisms of Cr-containing steels and Ni-base alloys at high-temperatures - Part I: the different role of alloy grain boundaries. Mater. Corros. 56, 785–790 (2005).

Zeng, Q. H. et al. Effect of grain size and grain boundary type on intergranular stress corrosion cracking of austenitic stainless steel: a phase-field study. Corros. Sci. 241, 112557 (2024).

Lin, Y., Laughlin, D. E. & Zhu, J. X. A study of the determination of grain boundary diffusivity and energy through the thermally grown oxide ridges on a Fe-22Cr alloy surface. Philos. Mag. 97, 535–548 (2017).

Wang, L. H. et al. Tracking the sliding of grain boundaries at the atomic scale. Science 375, 1261–1265 (2022).

Daulton, T. L. & Little, B. J. Determination of chromium valence over the range Cr(0)-Cr(VI) by electron energy loss spectroscopy. Ultramicroscopy 106, 561–573 (2006).

Schmid, H. K. & Mader, W. Oxidation states of Mn and Fe in various compound oxide systems. Micron 37, 426–432 (2006).

Sohlberg, K., Pennycook, T. J., Zhou, W. & Pennycook, S. J. Insights into the physical chemistry of materials from advances in HAADF-STEM. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 17, 3982–4006 (2015).

Amouyal, Y., Rabkin, E. & Mishin, Y. Correlation between grain boundary energy and geometry in Ni-rich NiAl. Acta Mater. 53, 3795–3805 (2005).

Fujii, T., Suzuki, M. & Shimamura, Y. Susceptibility to intergranular corrosion in sensitized austenitic stainless steel characterized via crystallographic characteristics of grain boundaries. Corros. Sci. 195, 109946 (2022).

Sabioni, A. C. S., Huntz, A. M., Silva, F. & Jomard, F. Diffusion of iron in Cr2O3: polycrystals and thin films. Mater. Sci. Eng. A 392, 254–261 (2005).

Lobnig, R. E., Schmidt, H. P., Hennesen, K. & Grabke, H. J. Diffusion of cations in chromia layers grown on iron-base alloys. Oxid. Met. 37, 81–93 (1992).

Newman, R. C. & Scenini, F. Another way to think about the critical oxide volume fraction for the internal-to-external oxidation transition? Corrosion 64, 721–726 (2008).

Alexander, K. C. & Schuh, C. A. Exploring grain boundary energy landscapes with the activation-relaxation technique. Scr. Mater. 68, 937–940 (2013).

Olmsted, D. L., Foiles, S. M. & Holm, E. A. Survey of computed grain boundary properties in face-centered cubic metals: I. Grain boundary energy. Acta Mater. 57, 3704–3713 (2009).

Krupp, U., Wagenhuber, P. E., Kane, W. M. & McMahon, C. J. Improving resistance to dynamic embrittlement and intergranular oxidation of nickel based superalloys by grain boundary engineering type processing. Mater. Sci. Technol. 21, 1247–1254 (2005).

Acknowledgements

This work was financially supported by the Natural Science Foundation of China (52371001, 12304002, 52374360).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

M.L. and Y.C. conceived and designed the experiments. M.L., Z.W., H.L., and X.W. conducted, and analysed the experiments. Y.Z., Y.C., A.L., L.W., and X.H. helped with data analysis. M.L., S.L., and D.P. prepared the manuscript. All authors contributed to the data discussion and manuscript revision.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Liu, M., Wang, Z., Zhao, Y. et al. Grain boundary energy affected initial oxidation on Ni-based superalloy revealed by in situ environmental TEM. npj Mater Degrad 9, 162 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41529-025-00705-4

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41529-025-00705-4