Abstract

To support a sustainable economy, the development of advanced and environmentally friendly food packaging systems is essential. This study presents innovative biodegradable composites based on polylactic acid (PLA), incorporating grape pomace and copper (Cu) nanoparticles as functional fillers to improve packaging performance. The composites exhibited rapid swelling when exposed to liquids. Grape pomace promoted a stable swelling behavior, maintaining a rate of ~1.2% over 100 days, leading to degradation through filler dissolution and increased porosity. In contrast, Cu nanoparticles initially enhanced structural integrity but later underwent surface delamination, accelerating swelling and degradation. Composites with lower Cu content showed a consistent swelling rate of around 4% for 20–60 days, followed by gradual disintegration. Higher Cu concentrations induced swelling via delamination, while erosion debris limited fluid penetration, resulting in slow and sustained biodegradation over 100 days. Antibacterial tests indicated that grape pomace composites lacked antimicrobial activity, whereas Cu-containing composites demonstrated significant antibacterial effects against Enterococcus faecalis and Klebsiella species, as well as strong antifungal activity against Candida albicans. These findings highlight the potential of PLA composites with grape pomace and Cu nanoparticles for biodegradable food packaging, offering tunable degradation behavior and enhanced antimicrobial properties.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Food packaging serves essential functions such as preserving, protecting, and maintaining the quality of the products. The common polymeric packages have a high pollutant potential due to their inability to be decayed by the environment and therefore plastic wastes pollutes earth and waters. These functions are only achievable if the packaging material retains its chemical and physical integrity over an extended period1,2. Therefore, the stability of the packaging material is closely linked to the product’s shelf life, which directly affects food quality3. In the food industry, the concept of “food quality” can have various meanings, depending on the type of product. Furthermore, in the specialized literature on food technology, there is no single, clear-cut definition of the term “shelf life,” due to its complexity4. Generally, shelf life is understood as the specific period after production (which may include processes such as maturation or aging) during which food retains its desired quality level, provided appropriate storage conditions are maintained5. In the context of European legislation, the term “shelf life” was first defined in Directive 13/EC (2000) on food labeling and later repealed by Regulation No. 1169 (2011), where it was referred to as the “minimum durability date” of food products.

Regarding packaging safety, Commission Regulation (EU) No. 10/20116 establishes the testing conditions for migration in order to validate materials intended to come into contact with food. This regulation permits the use of four food simulants to mimic real foods. The food simulants currently recommended by the EU are: 3% acetic acid in water (simulant A), 10% ethanol (simulant B), and 20% ethanol in water (simulant C)7.

In the case of biodegradable packaging, ensuring its stability under real usage conditions is essential for maintaining the shelf life of food products. Factors such as humidity, temperature, and ultraviolet (UV) light play a critical role in the stability of biodegradable packaging materials, while also influencing the biodegradation process after use8.

To date, there is no standardized procedure in scientific literature or legislation for evaluating the stability of PLA (polylactic acid) or other biodegradable packaging materials throughout their lifespan. However, it is important to note that the same conceptual approach applies to composting and biodegradation methods used for end-of-life analysis of materials, in accordance with standard NF 13432:20009.

One of the major limitations of PLA is its sensitivity to water, which poses a significant constraint for products with medium or long shelf lives, as reported in various shelf-life studies10,11,12. To use PLA as a packaging material for food products with extended shelf life, it is necessary to apply accelerated shelf-life testing (ASLT), similar to those used for food products. These tests are designed to simulate degradation processes under defined environmental conditions (temperature, humidity), which accelerate chemical reactions and thus shorten the time required for evaluation13.

The proposed study addresses an important topic: the stability of PLA in food applications. Fundamentally, it highlights the need for appropriate storage testing to better understand the behavior of the material under various conditions and to monitor its changes as it is used in contact with food.

Storage testing is essential for evaluating the chemical, physical, and microstructural stability of PLA and PLA-based nanocomposite materials, particularly considering that interactions between PLA and water can significantly affect its properties. In addition to stability studies, it is essential to consider the regulatory requirements related to the use of materials in contact with food. This includes ensuring that any structural changes in PLA do not result in the migration of hazardous substances into food, a critical aspect for consumer safety.

Besides the base polymer, plasticizers are key additives that enhance the flexibility of packaging materials, offering improved pliability across varying temperatures and good UV stability14. Depending on their concentration in composite materials, plasticizers can influence customer-specific requirements related to appearance, barrier properties, and handling.

Polylactic acid (PLA) has attracted significant attention as a biodegradable alternative to traditional petroleum-based polymers. However, its inherent brittleness and sensitivity to moisture limit its direct application in food packaging. To improve its performance, various strategies have been explored, including plasticization, reinforcement with inorganic nanoparticles, and the incorporation of natural fillers. Modifying the barrier properties of PLA is critical for food packaging applications, as excessive moisture absorption can compromise the material’s structural integrity and reduce the shelf life of packaged goods15.

Additives in food packaging are designed to meet specific performance needs or to enhance certain characteristics of base polymers. For example, research has shown that the incorporation of copper nanoparticles or other inorganic nanofillers (such as silver, zinc oxide, titanium dioxide, etc.) significantly enhances the properties of PLA16. These nanomaterials provide a larger specific surface area and contribute synergistically to the improvement of mechanical strength and antibacterial activity. As such, the use of eco-friendly packaging materials—such as PLA enhanced with copper nanoparticles—represents a promising approach to reducing the environmental impact of food packaging.

Grape pomace is a term used to describe the solid residues left after grape pressing in the winemaking process17. These residues consist mainly of skins, seeds, stems, and other plant particles. Extracts or compounds derived from grape pomace can be used as additives in packaging materials to improve moisture resistance and durability. These additives may also provide antimicrobial or antioxidant properties, thus helping to maintain the freshness of packaged food products.

To ensure consumer protection, the legal requirements regarding the migration of substances from materials in contact with food—particularly plastics—are regulated at the European level by Regulation (EU) No. 10/20116. Migration tests are carried out by exposing packaging materials to specific time and temperature conditions, followed by the determination of the concentration of migrating chemicals in the food simulants using analytical techniques such as chromatography18,19,20.

The aim of this study is to assess the chemical, physical, and structural stability of PLA-based composites incorporating copper nanoparticles and grape pomace when exposed to different storage solutions. The physical state of water is a crucial factor influencing the hydrolysis kinetics of PLA. When PLA is stored in direct contact with liquid water, the degradation process occurs at a slower rate compared to high humidity conditions. In these instances, the degradation products dissolve into the surrounding liquid medium in contact with the material.

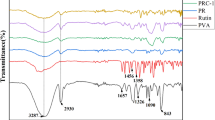

Results and discussion

Degradation and swelling of samples in simulants

As expected, the S1 (PLA 1) and S2 (PLA 2) samples exhibited the lowest liquid absorption, as shown in Fig. 1. For PLA 1, during the first 7 days, the absorption rate was the highest for most samples in all simulants, after which the process slowed down. For PLA 2, the absorption of the simulants reached much lower percentages, being much more resistant to moisture in all immersion media. The results show that S1 and S2 exposed to moist environments can absorb small amounts of water (less than 1.1% of their weight at 25 °C, close to the saturation point), similar to studies in the literature21,22. However, the absorption behavior over time varied depending on the composition of each composite.

Influence of Proviplast on Fluid Absorption: Incorporating 15% Proviplast into PLA led to higher fluid absorption compared to unmodified PLA. Since Proviplast is a plasticizer that increases the mobility of the polymer chains by disrupting the rigid PLA chains, it results in a more amorphous matrix that is more permeable to small polar molecules, providing a more hygroscopic structure23. This trend was evident in all the simulant media.

Incorporation of Grape Pomace at Different Concentrations: The incorporation of grape pomace at concentrations of 0.5%, 1%, and 1.5% demonstrated a concentration-dependent effect on fluid absorption. PLA composite reinforced with grape pomace reduces the moisture absorption at lower filler concentration, while higher levels of grape pomace (1.5%) doubled the absorption levels compared to pure PLA, particularly in simulant C. The moisture uptake increases as the weight percentage of grape pomace additives increases24. This behavior can be explained by the formation of agglomerates that can create voids, introducing microstructural defects and increasing permeability25. The initial increase and subsequent decrease in absorption for the 0.5% grape pomace sample are likely due to the swelling of the fibers, a common phenomenon in PLA composites reinforced with natural fibers. The hydrophilic nature of grape pomace allows it to absorb water in the early stages of exposure, but over time, the polymer matrix stabilizes26.

The swelling of the samples containing grape pomace can be attributed to the high concentration of polar compounds, such as polyphenols, tannins, organic acids, and residual sugars, which exhibit hydrophilic properties. These chemical compounds contain complex carbohydrate chains that are highly hydrophilic due to the presence of numerous hydroxyl and carboxyl groups. These groups form hydrogen bonds with water molecules, causing the material to absorb a large amount of water, and the degree of swelling is directly related to the concentration of these compounds in the composition of the analyzed experimental materials.

Incorporation of Copper Nanoparticles: The incorporation of copper nanoparticles at concentrations of 2%, 5%, and 8% showed a different effect depending on the loading degree but with similar behavior across all three simulant media. At lower concentrations (2%), the PLA composite reinforced with Cu showed increased absorption in the first month and then remained nearly constant until 3 months, a behavior similar to pure PLA. In contrast, higher Cu contents (≥5%) increased absorption levels above those of pure PLA in the first 20 days, but then decreased, reaching approximately the same value as sample S2 (PLA 2) by the third month. This trend has been observed in other biopolymer composites, where water-swollen fibers release the absorbed moisture once equilibrium is reached, ultimately reducing overall retention27. For S8, moisture absorption continuously decreased, showing negative values in all the investigated simulants. Studies on PLA composites with metal-based fillers indicate that prolonged exposure to ethanol can modify the nanoparticle-polymer adhesion, leading to higher diffusion rates28. These findings suggest that while 2% Cu increases moisture resistance, excessive Cu loading may compromise the integrity of the packaging, especially in alcoholic food storage applications29.

From a practical standpoint, this analysis of the stability of PLA and PLA-based materials suggests that the use of PLA monomer is suitable for producing packaging intended for semi-dry or dry foods, which are characterized by a water activity (aw) ≤0.530. These conditions are met by samples S1 and S2, which show the highest chemical stability. Stability decreases depending on the additives incorporated alongside the PLA monomer. It can also be observed that the higher absorption rate occurs at the lower the crystallization temperature31,32, as polymer degradation is influenced by the degree of crystallinity. The swelling rate increases in the following order: S8, S2, S1, S2, S3, S4, S5, S6, S7. Clearly, the addition of plasticizer and grape pomace increases the absorption rate, which later slows, reaching a maximum aw activity of up to 1.5. In this context, the composite formulations can be used for packaging dry foods, whereas for semi-dry foods, a shorter shelf life is required33.

In the case of samples S6, S7, and S8, the moisture absorption activity reaches a value of 5 within the first 21 days, the hydrophilicity of the samples being influenced by the presence of PEG used in the synthesis of Cu particles. Therefore, for these formulations, material stability requires special attention, as rapid loss of structural stability, which may result in changes to the material and reduce the potential shelf life it can offer.

The influence of the storage media on the formulations had a minor impact on the absorption behavior of the samples. Most samples displayed similar behavior across the three simulants, with slight absorption variations in the first 7 days or differences between the control and additive-containing samples. Literature data indicates that the swelling degree of PLA films is approximately 8.7 in alcohols (ethanol) and even higher in organic acids (acetic acid)34.

Composites containing Cu particles showed a higher dissolution rate than that of pure PLA film, likely due to the release of migratory nanoparticles. In the case of sample S8, the negative values may be attributed to the quantity of Cu particles released into the simulant35, as well as to potential agglomeration of the additives, which may have promoted the formation of voids in the packaging composite structure.

The differences in the swelling behavior among the studied samples can be attributed to the characteristics of the chosen base polymer, PLA. This material exhibits variations in melting temperatures, which reflect differences in the degree of crystallinity. A higher melting temperature (PLA 1) generally indicates a higher level of crystallinity, leading to a more compact and less permeable polymer structure that limits water absorption and swelling. In contrast, a lower melting temperature (PLA 2) suggests a lower degree of crystallinity, resulting in a more amorphous structure that facilitates greater water uptake and swelling.

The degradation behavior of the composites after 90 days in different simulants can be observed in Fig. 2b. The percentage mass loss of the samples was insignificant for S1 and S2, up to 1% for samples S3–S6, and up to 11% for the samples containing Cu particles (increasing directly in proportion to the particle content).

This significant percentage mass loss showed a negative value in sample S6, suggesting that a 2% concentration of Cu particles increases the swelling ratio of the sample without resulting in particle release. Above 5% additive content, all composites exhibited a notable increase in mass loss, attributed to the leaching of additives and ongoing interface degradation36,37.

Migration of metals from composites formulations into simulant media

The nature and composition of food are critical factors in evaluating migration. Foods with high fat content tend to exhibit elevated levels of migration38. Various food simulants have already been used to study the influence of food types on migration. Numerous studies have been conducted to investigate the mass transfer of substances between packaging and food by applying solubility parameters, which have helped in real-time testing of the degree of migration during food production.

A thorough understanding of the effect of additives on the migration behavior of materials in contact with food is essential for consumer health. The migration process is closely linked to the absorption and swelling capacity of the composite materials used39. The values obtained from the ICP-OES (Inductively Coupled Plasma Optical Emission Spectrometry) measurements are presented in Fig. 3.

When PLA is in direct contact with liquid water and lacks nano-fillers, the hydrolysis reaction proceeds more slowly, as the degradation products dissolve into the storage medium40. In this process, water or solvent penetrates the polymer structure, active compounds are solubilized, and diffuse toward the surface, from where they migrate into the food through the contact surface41.

The migration of copper particles and grape-derived compounds from packaging materials into food is based on a series of complex chemical mechanisms, influenced by the physicochemical properties of the packaging composites, the nature of the food to be packaged, and the storage conditions42,43,44. We assumed that the partial dissolution of the PLA polymer under the testing conditions facilitated the release of nanoparticles from the nanocomposite film into the simulant solvent. Thus, the approximate amount of migratory nanoparticles ranged from 0.5 to 8.5 mg/L in simulant A, and between 0.8 and 16.6 mg/kg in simulant B (Fig. 3).

In contrast, the pure PLA1 and PLA2 polymer films were chemically stable in the two food simulant solvents under room temperature migration conditions. A slight release of Zn was observed in the samples containing grape pomace in 10% ethanol, an effect that was absent in acetic acid. Grape-derived compounds, particularly polyphenols, can be solubilized in either the aqueous or lipid phase of the food, depending on their chemical structure and polarity. Their release into the food product is influenced by pH, solubility, intermolecular interactions, and the degree of dispersion in the polymer matrix45.

The high migration levels of Cu from the samples containing Cu particles (S6, S7, S8) suggest that organic filler materials may promote metal leaching due to increased polymer-filler interactions in ethanol- and acetic acid-rich environments. The amount of Cu migrated was higher in simulant B than in simulant A, indicating that the Cu particles obtained and incorporated into the S6–S8 formulations were more easily dissolved in acidic solutions than in organic ones—findings also supported by other studies in the literature46,47.

Similarly, the presence of plasticizers (Proviplast) in certain composites appears to affect the retention of metallic elements, as observed in the differing migration levels of Fe and Zn across the samples48. These findings highlight the importance of evaluating both hydrolytic degradation and migration behavior when designing PLA-based packaging for high-moisture or acidic food products49.

The migration ratio was defined as the ratio between the amount of additives migrated into the food simulant and the initial mass of the investigated sample immersed in 20 mL of food simulant. According to the experimental results, the additive content varied considerably between samples. The results are expressed as the mean migration ratio and are presented in Table 1, which also lists the absolute concentration of additives migrated into the different simulants. A significant migration of Cu particles was observed, particularly in simulant B. However, the overall migration for all samples remained below 10 mg·dm−2, the limit established by Regulation (EU) No 10/20116. Table 2.

Scanning electron microscopy (SEM)

Sample S1 contains only PLA1, which was processed in bulk form. The polymer wavefronts in the plastic phase flowed to form dense microstructural clusters with a boulder-like appearance, ranging in size from 5–10 µm, surrounded by the remaining plastic polymer flow, which ensured a compact microstructural packing (Fig. 4). The addition of grape pomace powder (serving as filler particles) in the presence of the plasticizer (Proviplast) led to a refinement of the microstructure by inducing a relatively laminar flow regime. This facilitated the reduction in wavefront size and, consequently, of the microstructural clusters in sample S3.

As the percentage of grape pomace powder increased while keeping the plasticizer content constant, a progressive refinement of the microstructure was observed in samples S4 and S5. The clusters became increasingly finer (1–5 µm) with a more rounded appearance. Some clusters showed a whitish appearance due to the direct exposure of grape pomace particles at the sample surface. (Grape pomace powder has more electro-insulating properties compared to the polymer matrix, and since SEM imaging was performed without metallization, electrostatic discharge of the electron beam occurred in those areas, producing an intense white appearance).

Exposure to 3% acetic acid solution for 3 months acted mainly on the less dense material surrounding the microstructural clusters, leading to the progressive dissolution of polymeric bonds and inducing microstructural degradation (Fig. 4)50. In the case of the composite samples, degradation was observed particularly in the filler particles directly located at the surface layer. On the other hand, the compact internal material better resisted disintegration due to the more advanced refinement of the microstructure. Therefore, S5 followed by S4 showed greater resistance than S3.

Exposure to the 10% ethanolic solution affected the surface of the samples by weakening the cohesion of the polymer material, which tended to disintegrate through swelling of surface morphological features. The boundary between the dense microstructural clusters and the intermediate layer became more diffuse, indicating a frontal-type degradation in sample S1. This mode of disintegration exposed more grape pomace particles to the erosive liquid, leading to their removal from the surface and resulting in the formation of eroded alveoli with a relatively oval shape, approximately 3–6 µm in S3. These features decreased in both number and size (1–4 µm) in sample S4 and were almost unnoticeable in sample S5. Doubling the ethanol concentration doubled the intensity of the erosive effect and the degradation of the composite material, as can be seen in the last row of Fig. 4.

Sample S2 contains PLA2, which is more plastic than the previously used PLA1, due to more mobile bonds within its constituent molecules. As a result, mould filling is more efficiently achieved, ensuring a laminar flow regime that leads to higher cohesion in the bulk material. The precision of mould filling induces the appearance of white microstructural details on its surface, caused by the polymer’s contact with the mold surface. The introduction of Cu nanoparticles reinforces the polymer matrix, giving the material a higher consistency and forming a wave-like flow front during molding, as seen in Fig. 5–sample S6. Increasing the Cu nanoparticle content in S7 further densifies the wave-like pattern on the contact surface with the mold. Finally, at a Cu content of 8% (sample S8), a pronounced densification of the material occurs, such that the wave-like front is no longer visible, and only slight depressions remain where the polymer contacted the mold surface.

Exposure of composite S2 to a 3% acetic acid solution for three months results in advanced surface erosion, characterized by funnel-shaped depressions with a base diameter of ~1–3 µm, expanding laterally to 3–10 µm.This observation suggests the possible presence of submicron mixing pores, which may not be detectable by SEM analysis but could account for the formation of these erosion funnels. Composite S4, when exposed to the same acetic acid solution, exhibits acid-etching pitting in the form of round, white-toned islands with central depressions. These features indicate the loss of filler particles that were directly exposed to the liquid environment. Increasing the filler content in composites S7 and S8 leads to microstructural complications. Presumably, submicron pores formed during polymer flow, together with the superficial delamination of Cu nanoparticles, result in pronounced erosion features, as observed in Fig. 5 for composites S7 and S8.

Exposure of composite S2 to a 10% ethanol solution results in frontal surface erosion, characterized by numerous shallow depressions ranging from 1–3 µm in diameter. This correlates with the presence of submicron mixing pores that have undergone advanced erosion due to the ethanol solution. Advanced surface erosion exposes Cu nanoparticles to the erosive environment, leading to progressive degradation of the composite microstructure with increasing filler content. For instance, in sample S7, a distinct erosion pit accompanied by a diagonal crack is observed. This pit has a diameter of approximately 12 µm and is partially filled with erosion debris. Increasing the ethanol concentration to 20% accelerates the degradation process, producing microstructural damage similar to that observed with the 10% solution, but with more pronounced effects.

SEM imaging reveals that composite samples containing grape pomace exhibit improved resistance to degradation with increasing filler content, whereas those incorporating Cu nanoparticles show more advanced degradation as the filler content increases.

This represents a qualitative assessment supported by the morpho-structural changes observed in the SEM micrographs. However, it calls for a complementary quantitative approach, such as surface roughness measurements, to correlate the topographic variations with fine-scale microstructural features.

The microstructural changes induced by the exposure to liquid affect the sample’s surface as observed in the SEM images. However, the pores network is less visible because of the grey level scaling of the SEM images. A special investigation effectuated with Image J software evidences the pores formation, Supplementary Fig. 1 and Supplementary Fig. 2. We found that pomace filler facilitates the formation of microstructural clusters which are prone to form pores when reach the outermost layers. Thus, the surface porosity has an increasing tendency with the pomace content. On the opposite copper filler facilitates a better homogenization of material avoiding pores formation in the initial state.

There were found two main ways in the pore’s formation. The first one consists in weakening of the polymer microstructural units which are progressively penetrated by the liquid generating small pores of about 1 to 2 μm in diameter for acetic acid and pores of about 2–3 μm for alcohol. Increasing the alcohol concentration has a tendency for pore diameter increase. It seems that ethanol particularly affects the polymer cohesion within the microstructural units. The second main mechanism in pore formation is the delamination of outermost layer filler particles and their subsequent mineral loss.

Thus, the polymer microstructural units weakening facilitate delamination of the filler particles increasing the pores diameter for both pomace and copper filler, Fig. 6, Spl1 and Spl2. The diameter pore increases progressively with the filler particles amount and aggressivity of the liquid environment, solution of 3% acetic acid having milder effect than 10% ethanol. Pores diameter is only one aspect of the problem; their proliferation on the samples surface affects the total porosity which represents an important indicator for the sample’s biodegradation abilities. Figure 6 present the variation of the total porosity with the filler amount.

The initial pomace samples feature a mild increase of the total porosity as consequence of the significant number of filler clusters exposed on the surface, Fig. 6a. This tendency is maintained through the liquid exposure. Overall, it results that the solution of 3% acetic acid features a moderate increase of the total porosity being exceeded by the solution of 10% ethanol. The best increase in porosity is ensured by 20% ethanol keeping the slightly increase with the filler content.

The initial copper samples feature a mild decrease of the porosity by the filler amount increase, fact explained by the promotion of the internal cohesion. But the liquid exposure weakens the cohesion within S2 polymer, causing filler delamination. Thus, the surface porosity increases with the filler amount for the exposed samples, Fig. 6b. Acetic acid solution ensure a mild proliferation of the pores within samples surface but ethanol has an aggressively effect materialised by a progressively increase of the surface porosity.

Atomic force microscopy (AFM)

Topographic details presented in Fig. 7 reveal that composite S1 forms compact microstructural clusters with a boulder-like morphology, ranging in size from 3 to 15 µm, interconnected by a continuous but less dense matrix. This structure is most likely a result of the polymer’s viscosity during mold filling, with the clusters formed by the advancing front of the polymer jet in its pasty state. The addition of grape pomace powder to the S1 composition leads to a refinement of the microstructure, breaking down the dense, rigid PLA clusters. At a 0.5% pomace content, these clusters are reduced to sizes below 2–3 µm, and at 1.5%, submicron clusters in the range of 200–800 nm are observed. This microstructural refinement is accompanied by a progressive reduction in surface roughness, as shown in Fig. 851.

Exposure to a 3% acetic acid solution for three months induces noticeable topographic changes, as illustrated in Fig. 7. The less dense edges of the clusters in composite S1 are particularly susceptible to microstructural disintegration caused by the acidic environment, leading to fragmentation of the clusters through a network of eroded cracks that reduce their size to approximately 5 µm. However, the overall surface topography becomes more irregular as a result. The microstructural refinement induced by the addition of grape pomace mitigates the fragmentation of the S1 matrix. Nonetheless, surface-exposed filler particles remain vulnerable to long-term acid erosion. In sample S3, numerous small pores are observed, associated with the loss of filler particles, which in some cases form localized debris agglomerations.

Sample S4, containing a higher amount of grape pomace and thus exhibiting improved microstructural uniformity, demonstrates greater resistance to degradation. Only a few shallow depressions (1–2 µm) caused by acid erosion are observed, while the rest of the surface remains largely intact. At a 1.5% grape pomace content in sample S5, the least amount of topographic alteration is observed, indicating enhanced microstructural cohesion. Still, some signs of filler particle dislodgement due to direct acid exposure are present. These topographic changes are expected to contribute to an increase in surface roughness, as shown in Fig. 8.

Alcohol exposure also induces notable topographic changes. Ethanol does not significantly impact the boundaries between microstructural clusters in sample S1 but instead causes superficial erosion. This results in the progressive degradation of the polymer matrix and the formation of erosion debris, predominantly in the form of numerous submicron particles. The beneficial effect of grape pomace on microstructural stability gradually counteracts the erosive impact of ethanol, with increasing filler content. In sample S3, a reduction in the number of submicron debris particles is observed, while sample S4 displays only a few erosion pits associated with filler particle dislodgement. Sample S6, exposed to 10% ethanol, exhibits a much more uniform surface topography compared to other samples in the same series, with only minor traces of erosion debris—an aspect that influences the overall surface roughness, as shown in Fig. 8.

Increasing the ethanol concentration to 20% has a significantly more aggressive effect on the surface topography of all tested samples. In sample S1, the erosion debris increases in size from submicron scale to 1–2.5 µm. For samples S3, S4, and S5, erosion features become noticeably more intense and deeper. The variation in average surface roughness indicates that exposure to 3% acetic acid over three months results in the least pronounced topographic alterations. In contrast, 10% ethanol causes slightly more intense erosion than the acetic acid solution, while 20% ethanol produces the most severe surface degradation. From a compositional standpoint, the addition of grape pomace enhances the resistance of the composites to the erosive effects of both acetic acid and ethanol.

Sample S2 exhibits a smooth and uniform topography, indicating that the polymer was well-homogenized due to its preparation characteristics and good fluidity. As a result, the microstructural clusters observed range in size from 1 to 5 µm and are strongly bonded to each other, as shown in Fig. 9. The presence of predominantly rounded superficial pores is also noticeable, with a slight tendency for elongation depending on the polymer’s plasticity during processing. These mixing pores have sizes between 2 and 3 µm. Therefore, sample S2 shows low surface roughness. The addition of Cu nanoparticles significantly affects the morphology and topography of the samples. The nanoparticles act as fillers within the S2 matrix, forming composite structures. The appropriate fluidity aids in the proper incorporation of Cu nanoparticles into the polymer matrix of sample S6, resulting in submicron details ranging from 120 to 300 nm. These contribute to the reduction of mixing pore sizes into the submicron range (150–300 nm). The presence of filler particles embedded in the polymer matrix leads to an increase in surface roughness, which likely correlates with a hardening of the composition. As the Cu nanoparticle content progressively increases in samples S7 and S8, a compaction of the microstructure occurs, with a reduction of mixing pores to near extinction. However, compact waves of composite material form, leading to a significant increase in surface roughness (Fig. 10). Exposure of these samples to a 3% acetic acid solution for three months results in the erosion of their topography. The erosive effect of the vinegar focuses on the pores formed during mixing, which tend to expand as the bonds within the S2 matrix weaken. The erosive effect is more pronounced in the composite samples, where filler particles exposed to prolonged acid action begin to delaminate and be removed from the surface, enlarging the pre-existing pores, as seen in sample S6.

Samples S7 and S8 are even more affected by the erosion of Cu nanoparticles from the surface, leading to the formation of irregularly shaped erosion pits with sizes up to 10 µm. In sample S8, erosion debris deposits are also observed, particularly in the top left corner. This results in a significant increase in surface roughness, as shown in Fig. 10.

Exposure to 10% ethanol for 3 months has significant effects on the topography of the samples.The general effect is still concentrated on the mixing pores, which are more susceptible to bond weakening in the S2 matrix, leading to an increase in their diameter. This behavior facilitates the massive delamination of Cu nanoparticles from the surface of sample S6, making it more uneven and irregular. The substantial loss of filler in sample S7 manifests as a large erosion crack flanked laterally by clusters of rounded debris particles, with sizes ranging between 2 and 4 µm. In sample S8, the erosion induced by 10% ethanol is much stronger, with extended depressions forming, which leads to an increase in surface roughness. Doubling the ethanol concentration to 20% exacerbates the surface irregularities, resulting in the highest surface roughness values.

Analyzing the roughness variations in Fig. 10, it can be observed that the superficial disintegration effect is facilitated by both the increase in Cu nanoparticle content and the higher concentration of the erosive agent. Overall, the acetic acid solution has a weaker effect compared to the ethanol solutions.

Antibacterial test

Bacterial adhesion to food packaging materials plays a crucial role in maintaining food quality52,53. The antibacterial activity is illustrated in Fig. 11, which presents the number of bacterial colonies for Escherichia coli ATCC 25922, Staphylococcus aureus ATCC 25923, Pseudomonas aeruginosa ATCC 27853, Enterococcus faecalis ATCC 29212, Klebsiella sp., and Candida albicans ATCC 10231 after 24 h of incubation at 10 °C. Figure 11 displays the inhibition zone diameters (mm) observed for each sample against the tested microbial strains in comparison with the control samples.

Various levels of antibacterial activity were observed among the tested bacteria. Sample S8 exhibited the strongest antibacterial effect. A decrease in antibacterial activity was noted in samples containing lower concentrations of copper, indicating that the antimicrobial performance was dependent on Cu content. Notably, antibacterial activity was entirely attributed to the presence of copper, as samples S1, S2, and those containing only grape pomace (S3, S4, S5) showed no inhibition zones, confirming the absence of antimicrobial activity. The diameters of the inhibition zones were as follows: Against S. aureus: 11, 11.5, and 12 mm; Against P. aeruginosa: 10.6, 11, and 12 mm; Against E. faecalis: 16, 16, and 18 mm; Against Klebsiella sp.: 15.5, 16, and 18 mm; Against C. albicans: 16.5, 17, and 20 mm and Against E. coli: 13, 14, and 15 mm. These results confirm that higher concentrations of copper lead to increased antimicrobial activity. Samples with the highest concentration of Cu particles demonstrated the strongest inhibition against all six microbial cultures, particularly against Candida albicans.

Antibacterial activity decreased in samples containing lower concentrations of Cu particles. Notably, even a 2% Cu particle content was sufficient to inhibit bacterial growth. Key bacterial properties that influence surface adhesion include hydrophobicity and surface charge54, along with various physicochemical interactions such as van der Waals forces, Lewis’s acid-base interactions, hydrophobic effects, and electrostatic forces55. In simulated media, copper ions exhibit a positive charge, which tends to result in stronger adhesion of Gram-positive bacteria compared to Gram-negative bacteria56,57.

The thickness of the adhesion interface is a crucial parameter for the successful embedding of filler particles within the polymer matrix58,59. The literature also indicates that the relative flexibility of the polymer matrix with respect to the filler particles ensures better microstructural integration60,61.

The antibacterial activity of the tested materials showed a clear dependence on the concentration of Cu particles. This lack of response against both Gram-positive and Gram-negative bacterial cultures can be attributed to the absence of an additive capable of providing intrinsic antibacterial properties.

This study highlights the distinct effects of Proviplast, copper nanoparticles, and grape pomace on the fluid absorption behavior of PLA-based composites. The addition of Proviplast enhances the elasticity and physicomechanical properties of the composites; however, the potential migration of plasticizers in ethanol-rich environments should be monitored. Incorporating grape pomace utilizes an agro-food byproduct, contributing to the circular economy and opening new directions for active and intelligent packaging. At moderate concentrations (0.5–1%), grape pomace promotes the microstructural consolidation of the composite. Copper nanoparticles have a dual effect: at low concentrations (2%), they improve moisture resistance, but at higher concentrations (≥5%), they increase the material’s porosity, accelerating degradation through delamination and surface particle loss. These nanoparticles exhibit good antimicrobial activity against bacteria and fungi, contributing to extended food shelf life. Moderate antibacterial effects were observed against Escherichia coli, Staphylococcus aureus, and Pseudomonas aeruginosa, underscoring the composites potential in food preservation. However, their migration into food products poses a risk, necessitating rigorous studies on food safety and maximum allowable limits. Controlled use of copper nanoparticles can lead to active packaging capable of inhibiting microorganism growth, thereby prolonging food freshness.

This study involved the development of polymer formulations and their characterization using laboratory equipment, with immersion media selected based on food simulants in accordance with Commission Regulation (EU) No. 10/20116, rather than actual food products. Only three immersion environments and three additive variations were tested, with each measurement repeated three times. The physicochemical characterization focused on a limited set of tests. Biodegradability and performance assessments were conducted under controlled laboratory conditions. However, the behavior of the packaging materials under real-use and storage conditions—such as variable humidity, fluctuating temperatures, and exposure to UV light—requires further investigation through extended studies.

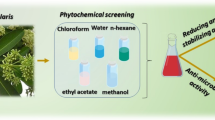

Methods

Sample preparation

The grape pomace powder was obtained by washing and drying grape clusters in a Memmert oven at 60 °C for 8 h, followed by grinding using a PM100 Retsch ball mill.

One of the main challenges in the synthesis of CuO nanoparticles is their tendency to agglomerate, a phenomenon that can be prevented by using polymers as coating agents66. In this context, coating the Cu nanoparticles with PEG 600 was carried out to improve their physicochemical properties and biological activities.

The Cu nanoparticles were obtained through reactive milling. Specifically, 2 g of copper sulfate powder were mixed with 15 g of PEG 600 and milled for one hour. After homogenization, 3 g of ascorbic acid were added. The resulting gel was stored at 4 °C (in a refrigerator) for 24 h to slow down the copper formation reaction, and then kept at room temperature. The Cu particles obtained have sizes up to 10 µm67.

In this study, six composite blend formulations were developed, based on polylactic acid (PLA) and the plasticizer Proviplast 2624 (supplied by Proviron, Hangzhou, China). To this base matrix, additives such as grape pomace and copper (Cu) particles were added, according to the compositions presented in Table 3. The composite mixtures were processed in the molten state using a Brabender Plastograph at a temperature of 180°C, with a mixing speed of 60 rpm and a mixing time of 20 to 30 min. For a relevant comparison, two control samples (S1 and S2) without any additives were also prepared.

PLA 1 (Ingeo™ 2003D) was used for the samples containing grape pomace because its higher mechanical strength and viscosity provide better compatibility and uniform dispersion of natural particles, while PLA 2 (Luminy® LX975) was selected for the copper nanoparticle samples due to its lower viscosity and melting point, which allow for more efficient nanoparticle dispersion and reduced thermal degradation of the polymer.

Degradation and swelling of the samples

Since the structure of polymer blends used for packaging materials can be influenced both by the humidity of the storage environment and by moisture absorbed from the packaged product, we aimed to study the effect of absorption in different simulants currently recommended by the European Union to mimic real food products68. The recommended food simulants are:

3% acetic acid in water = simulant A

10% ethanol = simulant B

20% ethanol in water = simulant C

Liquid absorption was analyzed as the weight increase relative to the initial measurement (M₀), using an analytical balance (Ohaus Explorer, Bucharest, Romania) with a precision of 0.001 g.

The samples, each approximately 10 mm in length, 10 mm in width, and 3 mm in thickness, were individually immersed in 20 ml of simulant and stored at room temperature for a period of 3 months. At specific time intervals (1, 2, 3, 7, 14, 21, 30, 60, and 90 days), the samples were removed from the immersion medium, blotted with absorbent paper, and weighed (Mw). According to ASTM D57069, the material mass loss (Mloss) and the swelling rate of the samples were calculated using the following equations:

where Mw represents the mass of the sample after 3 months of immersion in the simulant.

For each of the investigated formulations and each simulant, five specimens were prepared. The obtained values were statistically analyzed using the one-way ANOVA test (with a p value below 0.05 considered statistically significant) and the Tukey post-hoc test (performed using the Origin2019b software).

Migration of elements from the samples by ICP-OES

The determination of heavy metal content (Co, Cd, Cr, Cu, Fe, Ni, Pb, Zn, Mn) in aqueous solutions was carried out using Inductively Coupled Plasma Optical Emission Spectrometry (ICP-OES, Optima 2100 DV – Perkin Elmer, USA), with sequential determination of the elements of interest in aqueous solution. The principle of the method is based on vaporizing the liquid in an argon plasma (99.999%). The elements of interest are detected at selected wavelengths, with the intensity of the emitted optical radiation being proportional to the concentration of the element, expressed in mg/L. This is calculated internally using calibration curves.

The selected wavelengths were:Cd (228.802 nm); Cr (267.716 nm); Cu (327.393 nm); Co (228.616 nm); Fe (238.204 nm); Ni (231.604 nm); Pb (220.353 nm); Zn (206.200 nm); Mn (289.372 nm). Calibration curves were generated using three multielement solutions prepared from Calibration Standard ICP-(IV) – 1000 mg/L, at concentrations of 0.1 mg/L, 0.3 mg/L, and 0.5 mg/Detection limits used were as follows: Cd, Zn, Co (0.001 mg/L); Cr, Fe (0.002 mg/L); Cu (0.0004 mg/L); Pb (0.01 mg/L); Ni (0.005 mg/L), Mn (0.0004 mg/L).

In Regulation (EU) No. 10/20116, the overall and specific migration limits for additives, elements, and substances in a plastic material or article intended to come into contact with food are established within a legal framework. By relating the amount detected via ICP-OES to the initial quantity of the sample immersed in 20 mL of food simulant, we can determine the concentration of certain elements and compare them with the established limits.

Scanning electron microscope (SEM)

The surfaces of the samples, before and after immersion in the simulant solutions, were analyzed microscopically, under low vacuum, using the Inspect scanning electron microscope (FEI Company, Hillsboro, OR, USA) at a magnification of X 5000, 23 kV and 4.5 spot.

Pores occurrence and evolution through the SEM images were assessed with Image J software version 1.53t (National Institute of Health, Bethesda, USA). Each SEM image was transformed in 8-bit type and further dimensionally calibrated using their scale-bar. Pores distribution within the sample’s surface is sensitive at grey level (usually are darker than the outermost layer of the sample). Their presence was properly detected upon the grey level threshold and marked with red colour while the unaffected regions of the sample’s surface appear blue. The pores diameter was measured and counted resulting in the distribution histogram. The surface areas affected by pores were also quantified resulting as total porosity expressed in percents.

Atomic force microscopy (AFM)

The samples presented in Table 3 were analyzed by Atomic Force Microscopy (AFM), including one specimen in its initial state and specimens that had been immersed for 3 months in the three food simulant media used for the absorption study: 3% acetic acid, 10% ethanol, and 20% ethanol. All specimens were in a completely dry state and individually packaged in appropriately labeled bags.

AFM investigation was performed using a JSPM 4210 scanning probe microscope (Jeol Company, Tokyo, Japan) in tapping mode. The surface-sensing probe used was the NSC 15 Hard model from Micromesh Company (Sofia, Bulgaria), with a resonance frequency of 325 kHz and a force constant of 40 N/m. The surface of the samples was scanned over a square area with 20 µm sides in at least three macroscopically distinct regions. The topographic images obtained were analyzed using Win SPM 2.0 software (Jeol Company, Tokyo, Japan), and the surface roughness of each area was measured. The parameters Ra and Rq were recorded, and their average values were calculated.

Antibacterial test

The antimicrobial activity of the samples was studied on Escherichia coli ATCC 25922, Staphylococcus aureus ATCC 25923, Pseudomonas aeuginosa, ATCC 27853, Enterococcus faecalis ATCC 29212, Klebsiella sp. and Candida albicans ATCC 10231. All used bacterial cultures belong to the Microbiology Laboratory, Faculty of Biology and Geology from Babes Bolyai University.

Petri dishes with Mueller-Hinton agar medium were used for antimicrobial test. After solidification, 6 mm wells were formed using a sterile cut tip. A suspension of pure microbial culture, standardized to a 0.5 MacFarland scale, was applied to these plates using a sterile swab. A piece of each sample was placed in each well. The plates were left to incubate for 24 h (for bacterial strains) or 48 h (for Candida strain), at 37 °C, then the inhibition zones were measured70.

Data availability

The relevant data are available from the corresponding authors upon reasonable request.

References

Athenstädt, B., Fünfrocken, M. & Schmidt, T. C. Migrating components in a polyurethane laminating adhesive identified using gas chromatography/mass spectrometry. Rapid Commun. MassSpectrom 26, 1810–1816 (2012).

Muncke, J. Exposure to endocrine disrupting compounds via the food chain: Is packaging a relevant source. Sci. Total Environ. 407, 4549–4559 (2009).

Thomas A., Singh K., Fahadha U. & Changmai M. Testing protocols for sustainable materials, packaging and shelf life. Sustain Mat Food Packag Preserv. https://doi.org/10.1016/B978-0-443-13567-5.00017-4 (2025).

Robertson, B. A., Rehage, J. S. & Sih, A. Ecological novelty and the emergence of evolutionary traps. Trends Ecol. Evolut. 28, 552–560 (2013).

Nicoli M. C. Shelf-life assessment of food. Food preservation technology series. (CRS Press Taylor & Francis Group, 2012).

European Commission Commission Regulation (EU) No 10/2011 of 14 January on plastic materials and articles intended to come into contact with food. J. Eur. Union 12, 1–89 (2011).

Rossi L. Plastic Packaging Materials for Food. Barrier function, mass transport, quality assurance and legislation. Wiley, New York. European Community legislation on materials and articles intended to come into contact with food, pp. 393–406 (2000).

Holm V. K. Shelf life of foods in biobased packaging. In: Robertson, G. L. Ed. Food Packaging and Shelf Life: A Practical Guide. CRC Press, Boca Raton, pp. 353–362 (2010).

EN 13432: 2000/AC:2005 European committee for standardization. EN 13432. Packaging—requirements for packaging recoverable through composting and biodegradation-test scheme and evaluation criteria for the final acceptance of packaging, European standard. European Committee for Standardization, Brussels, Belgium Edition (2005).

Peelman N. et al. Use of biobased materials for modified atmosphere packaging of short and medium shelf-life food products. Innovative Food Science & Emerging Technologies. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ifset.2014.06.007 (2014).

Romani, S. et al. Effect of different new packaging materials on biscuit quality during accelerated storage. J. Sci. Food Agric. 95, 1736–1746 (2015).

Panseri, S. et al. Feasibility of biodegradable based packaging used for red meat storage during shelf-life: a pilot study. Food Chem. 249, 22–29 (2018).

Alfaro, M. E. C., Stares, S. L., Barra, G. M. O. & Hotza, D. Estimation of shelf life of 3D-printed PLA scaffolds by accelerated weathering. Mater. today Commun. 32, 104140 (2022).

Jung J., Cho Y., Lee Y. & Choi K. Uses and occurrences of five major alternative plasticizers, and their exposure and related endocrine outcomes in humans: a systematic review. Crit. Rev. Environ. Sci. Technol. https://doi.org/10.1080/10643389.2024.2301922 (2024).

Ranakoti L. et al. Critical review on polylactic acid: properties, structure, processing, biocomposites, and nanocomposites. Materials. https://doi.org/10.3390/ma15124312 (2022).

Ranakoti L. Bionanocomposites with hybrid nanomaterials for food packaging applications. Advances Biocomp App, Woodhead Publishing. 15, 4312 https://doi.org/10.1016/B978-0-443-19074-2.00007-1 (2022).

da Silva D. J., de Oliveira M. M., Wang S. H., Carastan D. J., Rosa D. S. Designing antimicrobial polypropylene films with grape pomace extract for food packaging. Food Packaging Shelf Life https://doi.org/10.1016/j.fpsl.2022.100929 (2022).

da Silva D. J. & de Oliveira M. M. Combined chromatographic and mass spectrometric toolbox for fingerprinting migration from PET tray during microwave heating. 34, 100929 (2022).

Alin, J. & Hakkarainen, M. Simultaneous determination of antioxidants and ultraviolet stabilizers in polypropylene food packaging and food simulants by high-performance liquid chromatography. Acta Chromatographica 61, 1405–1415, https://doi.org/10.1556/1326.2017.29.2.03 (2013).

Li B., Wang Z. W., Bai Y. H. Determination of the partition and diffusion coefficients of five chemical additives from polyethylene terephthalate material in contact with food simulants. Food Packaging Shelf Life https://doi.org/10.1016/j.fpsl.2019.100332 (2019).

Li, B., Wang, Z. W. & Bai, Y. H. Morphology, molecular mass changes, and degradation mechanism of poly-L-lactide in phosphate-buffered solution. Polym. Plast. Tech. Eng. 21, 100332 (2019).

Zhou, Z. H., Liu, X. P. & Liu, Q. Q. Novel aspects of the degradation process of PLA based bulky samples under conditions of high partial pressure of water vapour. Polym. Degrad. stab. 48, 115–120 (2009).

Oluwafunke P., Kucharczyk E., Hnatkova O. D., ZdenekDvorak V., Sedlarik G. O. Applications of Polylactic Acid-Magnesium Composite Materials for Sustainable Packaging Solutions. In TMS Annual Meeting & Exhibition. (Springer Nature Switzerland, 2013) pp 150-157.

Ahmed T. et al. Biodegradation of plastics: current scenario and future prospects for environmental safety. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11356-018-1234-9 (2018).

Ahmed, T., Shahid, M., Azeem, F. & Rasul, I. A state-of-the-art review on potential applications of natural fiber-reinforced polymer composite filled with inorganic nanoparticle. Compos. Part C Open Access 25, 7287–7298 (2018).

Azka M. A., Sapuan S. M., Abral H., Zainudin E. S. & Aziz F. A. An examination of recent research of water absorption behavior of natural fiber reinforced polylactic acid (PLA) composites: A review. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijbiomac.2024.131845 (2024).

Azka M. A., Sapuan S. M., Abral, H., Zainudin E. S. & Aziz F. A. Structure, mechanical properties, and dynamics of polyethylenoxide/nanoclay nacre-mimetic nanocomposites. Macromol 268, 131845 https://doi.org/10.1021/acs.macromol.9b01931 (2024).

Murariu, M., Paint, Y., Murariu, O., Laoutid, F. & Dubois, P. Recent advances in production of ecofriendly polylactide (PLA)–calcium sulfate (anhydrite II) composites: from the evidence of filler stability to the effects of PLA matrix and filling on key properties. Polymers 14, 2360 (2022).

Korumilli T., Abdullahi A., Kumar T. S. & Rao K. J. Nanoclay-reinforced bio-composites and their packaging applications. Nanoclay Based Sustain. Mat. 467-485 https://doi.org/10.1016/B978-0-443-13390-9.00022-9 (2024).

Gerometta M., Rocca-Smith J. R., Domenek S. & Karbowiak T. Physical and Chemical Stability of PLA in Food Packaging. Ref. Modul. Food Sci. https://doi.org/10.1016/B978-0-08-100596-5.22471-2 (2019).

Moldovan A. et al. Development and characterization of PLA food packaging composite. J. Therm. Anal. Cal. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10973-024-13841-x (2024).

Bondarev A. et al. P L A. plasticized with esters for packaging applications. Studia Univ Babes-Bolyai, Chemia, 68(2) (2023).

Ozkoc, G. & Kemaloglu, S. Morphology, biodegradability, mechanical, and thermal properties of nanocomposite films based on PLA and plasticized PLA. J. Appl. Polym. Sci. 114, 2481–2487 (2009).

Sato S., Gondo D., Wada T., Kanehashi S., Nagai K. Effects of various liquid organic solvents on solvent-induced crystallization of amorphous poly (lactic acid) film. J. Appl. Polymer Sci. https://doi.org/10.1002/app.38833 (2013).

Velichkova H. et al Influence of polymer swelling and dissolution into food simulants on the release of graphene nanoplates and carbon nanotubes from poly (lactic) acid and polypropylene composite films. J. Appl. Polymer Sci. https://doi.org/10.1002/app.45469 (2017).

Shen, L., Yang, H., Ying, J., Qiao, F. & Peng, M. Preparation and mechanical properties of carbon fiber reinforced hydroxyapatite/polylactide biocomposites. J. Mater. Sci: Mater. Med. 20, 2259–2265 (2009).

Shanmuganathan, K., Capadona, J. R., Rowan, S. J. & Weder, C. Biomimetic mechanically adaptive nanocomposites. Prog. Polym. Sci. 35, 212–222 (2010).

Triantafyllou, V., Akrida-Demertzi, K. & Demertzis, P. A study on the migration of organic pollutants from recycled paperboard packaging materials to solid food matrices. Food Chem. 101, 1759–1768 (2007).

Petrovics N. et al. Effect of temperature and plasticizer content of polypropylene and polylactic acid on migration kinetics into isooctane and 95 v/v% ethanol as alternative fatty food simulants. Food Packag Shelf. Life. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.fpsl.2022.100916 (2022).

Rocca-Smith, J. R. et al. Effect of the state of water and relative humidity on ageing of PLA films. Food Chem. 236, 109–119 (2017).

Gupta, R. K. et al. Migration of chemical compounds from packaging materials into packaged foods: interaction, mechanism, assessment, and regulations. Foods 13, 3125 (2024).

Liu T. et al. Enhancement of mechanical and thermal properties of PBSeT copolyester by synthesizing AB-type PBSeT-PLA macromolecules. Adv. Comp. Hybrid Mat. https://doi.org/10.1007/s42114-024-01151-7 (2025).

Yenidoğan, S., Aydemir, C. & Doğan, C. E. Packaging–food interaction and chemical migration. cellulose. Chem. Technol. 57, 1029–1040 (2023).

Brandsch R. et al. Practical guidelines on the application of migration modelling for the estimation of specific migration. (E. J. Hoekstra.Publications Office, 2015) pp.40.

Metak, A. M., Nabhani, F. & Connolly, S. N. Migration of engineered nanoparticles from packaging into food products. LWT Food Sci. Technol. 64, 781–787 (2015).

Liu, F., Hu, C. Y., Zhao, Q., Shi, Y. J. & Zhong, H. N. Migration of copper from nanocopper/LDPE composite films. Food Addit. 33, 1741–1749 (2016).

Su, Q. Z. et al. Effect of antioxidants and light stabilisers on silver migration from nanosilver-polyethylene composite packaging films into food simulants. Food Addit. Contam A 32, 1561–1566 (2015).

Eti, S. A. et al. Assessment of heavy metals migrated from food contact plastic packaging: Bangladesh perspective. Heliyon 9, e19667 (2023).

Anvar A. et al. Evaluation of the antibacterial effects of Ag-TiO2 nanoparticles and optimization of its migration to sturgeon caviar (Beluga). Iran. J. Fish. Sci. https://dor.isc.ac/dor/20.1001.1.15622916.2019.18.4.13.4 (2019).

Bott, J., Störmer, A. & Franz, R. A model study into the migration potential of nanoparticles from plastics nanocomposites for food contact. Food Packag. Shelf Life 2, 73–80 (2014).

Duncan T. V. & Pillai K. Release of engineered nanomaterials from polymer nanocomposites: diffusion, dissolution, and desorption. ACS Appl. Mater Interfaces (2015). https://doi.org/10.1021/am5062745

Bayoumi, M. A., Kamal, R. M., Abd El Aal, S. F. & Awad, E. I. Assessment of a regulatory sanitization process in Egyptian dairy plants in regard to the adherence of some food-borne pathogens and their biofilms. Int. J. Food Micro. 158, 225–231 (2012).

Padhan, B. et al. Recent advancements in nanocomposites-based antibiofilm food packaging. J. Polym. Mater. 42, 411–433 (2025).

Magyari, K., Stefan, R., Vodnar, D. C. & Vulpoi, A. The silver influence on the structure and antibacterial prop erties of the bioactive 10B2O3 − 30Na2O − 60P2O2 glass. J. Non CrystalSol. 402, 182–186 (2014).

Katsikogianni, M. & Missirlis, Y. Concise review of mechanisms of bacterial adhesion to biomaterials and of techniques used in estimating bacteriamaterial inter actions. Eur. Cells Mat. 8, 37–57 (2004).

Faille, C. et al. Adhesion of Bacillus spores and Escherichia coli cells to inert surfaces: Role of sur face hydrophobicity. Canad J. Microbio. 48, 728–738 (2002).

Nithya M., Balaji R., Sundarajan T. & Sivalingam V. Novel PLA/chitosan blends with bio-released Ag-NPs nanocomposites for eco-friendly food packaging. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 1-10 https://doi.org/10.1007/s11356-025-36610-1 (2025).

Linghu C. et al. Long-term adhesion durability revealed through a rheological paradigm. Sci. Adv. 14;11. https://doi.org/10.1126/sciadv.adt3957 (2005).

Linghu C. et al. Versatile adhesive skin enhances robotic interactions with the environment. Sci. Adv. 11, https://doi.org/10.1126/sciadv.adt4765 (2025).

Weber, F., Dötschel, V., Steinmann, P., Pfaller, S. & Ries, M. Evaluating the impact of filler size and filler content on the stiffness, strength, and toughness of polymer nanocomposites using coarse-grained molecular dynamics. Eng. Fract. Mech. 307, 110270 (2024).

Shalygina, T. A. & Rudenko, M. S. Nemtsev IV, Parfenov VA, Voronina SY, Simonov-Emelyanov ID, Borisova PE. Influence of the filler particles’ surface morphology on the polyurethane matrix’s structure formation in the composite. Polymers 9 13, 3864 (2021).

https://www.specialchem.com/polymer-additives/product/proviron-proviplast-2624

Javed R., Ahmed M., Haq I., Nisa S. & Zia M. PVP and PEG Doped CuO Nanoparticles Are More Biologically Active: Antibacterial, Antioxidant, Antidiabetic and Cytotoxic Perspective. Mat. Sci. Eng. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.msec.2017.05.006 (2017).

Popescu V. et al. Antimicrobial poly (lactic acid)/copper nanocomposites for food packaging materials. Mat. https://doi.org/10.3390/ma16041415 (2023).

de Normalisation C. E. EN 13130-1: Materials and articles in contact with foodstuffs–Plastics substances subject to limitation–Part 1: Guide to test methods for the specific migration of substances from plastics to foods and food simulants and the determination of substances in plastics and the selection of conditions of exposure to food simulants. Brussels: CEN (2004).

Standard for water absorption test, ASTM D570. https://www.intertek.com/polymers-plastics/testlopedia/water-absorption-astm-d570/

Carpa R., Keul A., MunteanV, Dobrotă C. Characterization of Halophilic Bacterial Communities in Turda Salt Mine (Romania). Orig Life EvolBiosph https://doi.org/10.1007/s11084-014-9375-4 (2014).

Acknowledgements

This research received no external funding.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Andrei Moldovan helped in conceptualization and investigation. Ioan Sarosi contributed in investigation. Stanca Cuc helped in writing—reviewing and editing and formal analysis. Doriana Popa contributed to writing—original draft. Ioana Perhaita helped in analysis and supervision. Ioan Petean and Rahela Carpa contributed in formal analysis. Ovidiu Nemes and Stanca Cuc were involved in visualization and editing. Lucian Barbu Tudoran was involved in investigation.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Moldovan, A., Cuc, S., Petean, I. et al. Biodegradability of selected poly(lactic acid) composites for sustainable food packaging applications. npj Mater Degrad 10, 12 (2026). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41529-025-00724-1

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41529-025-00724-1