Abstract

Tetramethylphosphoric acid, guanidine dodecyl monohydrochloride, and sodium molybdate can be easily synthesized into an antibacterial material (TNG) that is almost insoluble in water. However, TNG still has limitations when used directly as a protective layer on metal surfaces. Nevertheless, TNG can serve as a coating enhancer, significantly improving the hydrophobicity of the coating while maintaining its hardness. TNG enhances the corrosion resistance of epoxy coatings against microbial attack caused by sulfate reducing bacteria (SRB) biofilm. The epoxy coating enhanced by TNG effectively inhibited the formation of SRB biofilm and kill a few sessile cells. Compared to coatings not enhanced with TNG, the corrosion current density was reduced by 3460 times. A dynamic corrosion test conducted over 9 months in the Yangtze River basin demonstrated that the stable presence of TNG in the epoxy coating achieves long-term inhibition of biofouling in real-world environments.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

A new type of high manganese steel (HMS) with a Mn content of 22.5% to 25.5% (wt%) is being rapidly developed as a key material for LNG storage and vaporization equipment1,2. However, long-term contact with seawater makes corrosive microorganisms, such as sulfate-reducing bacteria (SRB), could triggered microbiologically influenced corrosion (MIC) for HMS3. SRB could embrittle the grain boundaries of HMS to cause intergranular corrosion, and also could establish electron transfer pathways with HMS to induce surface corrosion pits.

In general, SRB-mediated metal corrosion can be divided into two categories: extracellular electron transfer-mediated microbial corrosion and microbial metabolic corrosion medium-mediated material corrosion (M-MIC)4,5. The former is commonly observed in “high-energy” metals such as Fe, Cr, and Mn. According to the biocatalytic cathodic sulfate reduction theory6, SRB can utilize these “high-energy” metals as alternative electron donors in respiration. At 25 °C and 1 M metal ion concentration, the equilibrium potentials (vs. SHE) for Fe2+/Fe (1), Cr3+/Cr (2), and Mn2+/Mn (3) are −447 mV, −710 mV, and −1050 mV, respectively, with battery potentials coupled to sulfate reduction (4, −217 mV at pH 7 and 1 M solutes at 25 °C) of +230 mV, +833 mV, and +493 mV, respectively7, corresponding to negative Gibbs free energy (spontaneity). A typical example of the latter is that the metabolite H2S secreted by SRB can directly corrode copper. M-MIC typically produces large amounts of H2, because H⁺ often serves as the actual electron acceptor3.

Therefore, to prevent the occurrence of MIC, killing corrosive microorganisms or using coatings to block contact between microorganisms and metal substrates has become the primary means of mitigating MIC.

Quaternary phosphates are represented by Tetrakis(hydroxymethyl)phosphonium sulfate (THPS) (Fig. 1A), which is also a commonly used crosslinking agent and flame retardant. Guanidine biocides represented by guanidine dodecyl monohydrochloride (GDMC) (Fig. 1B) are famous for their low-cost/dose, broad-spectrum bactericidal properties and environmental friendliness8. They kill bacteria by disrupting the bacterial outer membrane and intracellular nucleic acids through cationic groups. It was shown that 50 ppm of THPS was able to inhibit the growth of SRB biofilms to prevent carbon steel corrosion9. The addition of 50 ppm polyhexamethylene guanidine to simulated seawater containing SRB can also inhibit the growth of SRB planktonic and sessile cells to mitigate carbon steel MIC10. Smaller molecules of GDMC appeared to be more effective in inhibiting microbes because 25 ppm additions killed 100% of S. aureus and and E. coli11. However, LNG is a system that is inextricably linked to circulating seawater. Continuous delivery of large quantities of biocides into pipelines and gasification units makes no sense and compromises the quality of the gas. In addition, the theoretical biocide dose delivered on-site might be inadequate, which could cause rebound and acceleration of MIC8,12.

Epoxy coating stands out for its low cost, high stability and strong adhesion, being an efficient coating protection technology for a wide range of applications in marine oil and gas fields13,14,15. The excellent performance of epoxy coating can be easily mistaken as sufficient to isolate metals from corrosive microbes, which is clearly not the case. Pseudomonas sp. could oxidize epoxy coating to form hydroxyl groups, causing pits on the surface of coating and making the coating less resistant to corrosion16. Bacillus biofilms were shown to significantly degrade the bio-tolerance of epoxy coating to the point of degradation on day 1917. SRB proliferated to form irregular biofilm, which resulted in severe pitting, affecting the protective properties of epoxy coating18 After 96 h of immersion of epoxy coating in SRB medium, its polarization resistance and adhesive strength decreased dramatically, with significant deterioration of coating performance19. This would seem to make it not wise to use biocides or epoxy coatings alone. Therefore, the promotion of coating antimicrobial properties is a key strategy to cope with long-term MIC.

The preparation of antimicrobial coatings has become a long-lasting strategy against MIC. For example, the addition of cuprous oxide to the coating could effectively address coating degradation caused by Pseudomonas aeruginosa and S. aureus20. DCOIT and copper omadine as coating fillers were effective in inhibiting marine bacterial activity and macro-biofouling21. These copper-containing antimicrobial coatings appear to be ineffective in SRB environments because HS− production precipitates copper ions4. In addition, various types of two-dimensional nanofillers were experimentally applied in coatings, which also have the potential to enhance strength and antimicrobial properties of epoxy coatings22,23, but their preparation tends to be complex and conditionally stringent, with this not being conducive to rapid field application.

If the liquid biocides THPS and GDMC mentioned above are added as fillers to epoxy coatings, they will dissolve quickly due to their water solubility, which in turn accelerates the weakening of the epoxy coating. Our previous study used Na2MoO4 (Fig. 1C) reacted with soluble polyhexamethylene guanidine to obtain a low-solubility PHMG-MoO4 filler, which demonstrated the feasibility of co-precipitation of molybdate with commonly used biocides10. This type of solidified coating filler required fine grinding to be added to the epoxy coating, increasing the potential for inhomogeneous dispersion and affecting the surface flatness of the coating. In view of the above, in order to solve the problems of dissolution of single-component biocide addition and non-uniform dispersion of powder, the epoxy-coated fillers with both antimicrobial activity and excellent physicochemical properties were synthesized in this study using THPS, molybdate, and GDMC in an extremely simple way to achieve long-lasting inhibition of SRB-MIC.

Results and discussion

Composition and inhibition characteristics of TNG

The SRB-MIC effects of various independent biocides on HMS are shown in Fig. S1 and Table 1 of the Supplementary Materials. Analyzing the structure and reason for the inhibition of TNG is even more important because of the rich variety of substances involved in TNG. In FTIR (Fig. 2A), the peaks at 2932 cm−1 and 2814 cm−1 were associated with hydroxymethyl and methylene vibrations24. The peak at 1631 cm−1 was a mixed peak. Due to the presence of the aqueous phase, H-O-H oscillatory peaks in T, TN, and G could be detected; C=N was also exhibited there25, indicating the retention of the inhibitory component guanidino group in GDMC. The peak at 1423 cm−1 represented C-H bending vibrations26 or Mo-O-Mo bridging oxygen vibrations, flanking the formation of heteropolyacid structures27. The peaks at 1094 cm−1 and 1034 cm−1 could be P-O-Mo vibrations or central {PO4} (e. g. [PMo12O40]3−)28,29,30, because the P-O vibrational peaks could be coupled to the Mo-O backbone in this range leading to split peaks. In addition, the Mo-O-Mo bridge oxygen vibration at 798 cm−1 in TN and TNG was consistent with the inorganic backbone characteristics of typical heteropolyacid31,32. The peak at 636 cm−1 was typical of molybdate33. FTIR results showed that TNG was not a simple superposition of three single substances, but a complex with a complicated structure. XRD (Fig. S2) was able to detect faint characteristic peaks of keggin-type phosphomolybdenum heteropolyacid at 2θ of 19° and 22°34, but exhibited amorphous features in other wide-angle regions. On the one hand, it might be that the phosphomolybdenum heteropolyacid did not form a long-range ordered crystal structure; on the other hand, it might be that the long-chain alkyl groups (C12H25) of GDMC bonded to the heteropolyacid clusters via van der Waals forces, which disrupted the ordered stacking of the inorganic skeleton and caused the overall structural disorder35.

The existence forms of important elements Mo, P, O, N and C in TNG were analyzed by XPS fine spectra to corroborate the results of FTIR and XRD. The presence of Mo6+ and Mo5+ peaks at 232.6 eV and 235.3 eV in the Mo 3 d mapping (Fig. 2B) was attributed to the Mo-O octahedral structure in the formed heteropolyacids rather than free molybdate because TNG was subjected to a rigorous water-washing process32,36. In addition, the peaks at 132.8 eV in the P 2p spectrum (Fig. 2C) were associated with P-O30. For the O 1s pattern in Fig. 2D, the peaks of P-O and Mo-O appeared at 531.7 eV and 530.8 eV, respectively37,38. In Fig. 2E, F, amine group (N 1s, 399.5 eV), guanidino group (C 1s, 288.3 eV), and alkane chain were also shown to be present10,39, again suggesting that TNG is a complex structure consisting of both inorganic and organic phases coexisting. Combining FTIR, XRD and XPS results, we successfully composited THPS, Na2MoO4 and GDMC, in which a heteropolyacid framework might be formed and the effective antimicrobial moieties were retained.

Assessment of TNG stability and inhibition effect on SRB biofilm

In general, the dissolution of major bio-inhibitory components is an important factor in the failure of antimicrobial coatings40,41. TNG was hardly dissolved because the weight loss of the dried TNG was less than 1% (wt) in both groups (Fig. 3A, 0.4‰ in Group 1 and 0.1‰ in Group 2). TNG might contain phosphomolybdenum heteropolyacid anions, in which Mo-O-Mo bridge bonds and P-O-Mo bonds were able to form stable and insoluble inorganic skeletons42. In addition, we evaluated the swelling rate of TNG in seawater using the mass method and the result was 1.7%. According to the Flory-Rehner theory, a low dissolution rate means that TNG has a high cross-linking density, which restricts the movement of molecular chains and prevents leaching of the active ingredient43. Consequently, we determined the effect of TNG on SRB cell growth (Fig. 3B). The addition of 5% (wt) TNG to the SRB medium did not substantially affect SRB growth, and the decrease in the number of planktonic cells with days were the result of nutrient depletion within the culture medium.

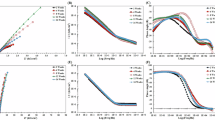

TNG was able to be directly applied to the HMS surface to form a coating, and its impedance gradually increased from 1 to 14 days and stabilized after a slight decrease at 21 and 28 d (Fig. 4A, B). The EIS data were fitted using a parallel equivalent circuit with two-time constants, and the fitted parameters are shown in Table S2. The Rf values of the TNG coatings during immersion peaked at 14 d and then remained stable. In addition, from the fitted double-layer capacitance and film capacitance, the values of Qf and Qdl decreased by two orders of magnitude with the increase of immersion time, indicating that the stability of the TNG coating in biological medium was not affected by the SRB.

The polarization curve of uncoated HMS immersed in SRB medium for 28 days (Fig. 4C) exhibited a more negative corrosion potential (−829 mV) than TNG covered HMS (−726 mV), suggesting that SRB was thermodynamically less inclined to corrode TNG covered HMS5. The fitted corrosion current icorr values in Table S3 indicated that the icorr of TNG-covered (1.3 μA cm−2) electrodes only accounted for 2.9% of the bare HMS icorr (44.6 μA cm−2), suggesting that TNG can greatly mitigate the corrosion of HMS by SRB. Furthermore, the details of the surface condition of HMS directly coated with TNG before and after 28 days are also provided in Supplementary materials Fig. S3.

TNG exhibited excellent dissolution and expansion rates, as well as strong inhibitory activity against SRB biofilm. The high antimicrobial effect of guanidine salts has been confirmed by many studies10,44. This work has demonstrated that 30 ppm GDMC could effectively inhibit the formation and growth of SRB biofilm. The excellent antimicrobial properties of GDMC are attributed to its positively charged guanidine group. GDMC could attract negatively charged SRB bacteria and disrupt cell membranes45. Long-chain alkyl groups were able to insert into the lipid bilayer, increasing membrane permeability and leading to leakage of intracellular ions and metabolites46. In addition, guanidino groups were also able to bind to acidic residues of membrane proteins, triggering conformational collapse47.

Properties of coating containing TNG enhancer

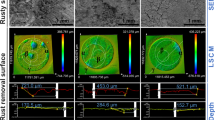

Figure 5 shows the original surface morphologies and elemental distributions of unfilled epoxy coating (Fig. 5A), Na2MoO4-filled epoxy coating (Fig. 5B) and TNG-enhanced epoxy coating (Fig. 5C). The surface of the Na2MoO4-filled epoxy coatings was more grainy and rougher compared to the unfilled epoxy coatings, while the TNG-enhanced epoxy coatings appeared much finer. From the Mapping patterns, it could be found that the distribution of major elements in the various epoxy coatings was uniform, and there was almost no regional enrichment of the elements, indicating that the homogeneity of the coatings was excellent.

In Fig. 5, the water contact angles of the unfilled epoxy coating and the Na2MoO4-filled epoxy coating were 13° and 17°, respectively, which were much smaller than the 89° of the TNG-enhanced epoxy coating, suggesting that TNG significantly increased the hydrophobicity of the epoxy coating. The hydrophobicity of the coating was derived from the formation of a hydrophobic layer on the surface by the long-chain alkyl groups, which greatly reduces the surface energy of the coating48. In addition, the hydrophobic layer of dodecyl chains could block the penetration of water molecules and reduce the contact of the internal cross-linked network with seawater, which will also inhibit the swelling and hydrolysis of TNG.

After the epoxy coatings with different fillings were prepared on the HMS surfaces, the coating thicknesses were measured at the coupon cross-section. The thickness of each coating was around 50 μm (Fig. S4). Line scans of the coatings showed that Na2MoO4 and TNG had been successfully prepared into the corresponding epoxy coatings. The hardness of the coatings usually reflects their abrasion resistance, and the pencil hardness method is the most frequently used and fastest test method to visualize the hardness of the coatings in the industrial field. The pencil hardness (Fig. 6A, B, C) of the unfilled epoxy coating was 3H. The pencil hardness of Na2MoO4-filled epoxy coating (Fig. 6D, E) was able to reach 5H, which was attributed to the reinforcing effect of solid Na2MoO4 on the overall hardness of the coating. The pencil hardness of TNG-enhanced epoxy coating (Fig. 6F, G, H) was 4H, which was lower than that of Na2MoO4-filled coating but similar to that of the unfilled epoxy coating, suggesting that filling of TNG did not decrease the hardness of the epoxy coatings in use.

Resistance of coating containing TNG enhancer in SRB medium

HMS coated with different filled epoxy coatings were incubated in SRB medium for 28 days to observe planktonic, sessile cell counts and solution pH changes, as shown in Fig. 7. The number of planktonic cells (Fig. 7A) was almost the same for uncoated, unfilled and TNG-enhanced systems at 7, 14, and 28 d, whereas there was a slight decrease in planktonic cells for Na2MoO4-filled condition, attributed to the inhibitory effect of molybdate on SRB. However, the author experimentally found that molybdate concentration could only completely inhibit the growth of SRB up to 300 mg/L, thus the small reduction of SRB planktonic cells would not have a decisive effect on the overall number of SRB. The planktonic cell results also indicated no dissolution of the active ingredient after TNG filling. The sessile cell counts (Fig. 7B) on the uncoated HMS, unfilled and Na2MoO4-filled epoxy coating surfaces remained in the order of 107 cells/cm2 at 14 and 28 d, while the sessile cell count on the TNG-enhanced epoxy coating surfaces was decreased from the order of 103 cells/cm2 on day 14 to the order of 102 cells/cm2, indicating that TNG was able to effectively inhibit the SRB cell adhesion, which not only stemmed from the inhibition of the contacted SRB growth by TNG, but also related to the substantial increase in the hydrophobicity of TNG to the epoxy coating. In Fig. 7C, the increase in pH after incubation in all systems compared to the initial medium pH (7.2) was related to the consumption of H+ by SRB metabolism. However, the pH in the Na2MoO4-filled system was about 0.2 higher compared to the other conditions, suggesting that Na2MoO4 had dissolved because it would have alkalized the medium.

The surface morphologies of the epoxy coatings with different fillings after immersion in SRB medium is shown in Fig. 7D-I. The surfaces of unfilled and Na2MoO4-filled coatings were covered by dense SRB biofilm at 14 d (Fig. 7D, E), and the biofilm did not decrease significantly at 56 d (Fig. 7G, H). Large amounts of the characteristic element S were detected on the unfilled and Na2MoO4-filled coating surfaces, and the corresponding fluorescence images (Fig. S5) also displayed the distribution of SRB sessile cells on the unfilled and Na2MoO4-filled surfaces after 14 and 56 days of immersion, suggesting that the addition of Na2MoO4 did not increase the resistance of the epoxy coating to SRB, and that dissolved Na2MoO4 was unable to pose a threat to sessile SRB. However, SRB biofilm failed to form on the surface of TNG-enhanced epoxy coating, and only a few deformed SRB cells could be seen after 14 days of incubation (Fig. 7F). When the immersion time was extended to 56 days (Fig. 7I), continuous biofilm still did not form on the surface of TNG-enhanced epoxy coatings, and only a few SRB cells were attached and killed. This indicated that the TNG-enhanced epoxy coating could effectively prevent SRB adhesion and inhibit the formation of biofilm on the surface of the coating, and its antimicrobial performance was much better than that of the control group.

The integrity of the different filled epoxy coatings was observed after removing biofilm and corrosion products from all surfaces. The unfilled coating and the Na2MoO4-filled coating showed cracks or corrosion pits on the surfaces (Fig. 8A, B). The appearance of many micropores on the surface of the Na2MoO4-filled coating appeared to demonstrate the dissolution of the Na2MoO4 particle filler. The damage to the surface of the coating implies a partial loss of corrosion resistance. Tambe noted that the damage to the coating could be attributed to the metabolic activity of the bacteria19. The coating breakage observed in this work was likely related to the formation of SRB biofilm (Fig. 7D, G, E, H). The surface of the TNG-enhanced coatings remained flat with no visible breakage because there was no SRB biofilm adherence (Fig. 8C, Fig. 7F, I). Cross-sectional tests after 56 days of incubation in SRB media showed that the cut edges of the unfilled and Na2MoO4-filled epoxy coatings exhibited coating peeling, especially the unfilled coatings tended to overall flake off (Fig. 8D, E), which corresponded to ASTM D3359 grades 2B and 4B. The cut edges of the TNG-enhanced epoxy coatings were very smooth and neat, with no coating peeling (Fig. 8F), corresponding to class 5B in ASTM D3359, indicating good adhesion strength between the coating and carbon steel compared to the control. These were in agreement with or even superior to the results of the test in the known literature10. The cross-cut test further demonstrated the damaging effect of SRB biofilm on different epoxy coatings and the effective inhibition of SRB by TNG as a filler.

Electrochemical measurements of epoxy coatings with different fillings

The resistance and stability of differently filled epoxy coatings incubated in SRB media for 28 days were investigated using Nyquist plots (Fig. 9A, C, E) and Bode plots (Fig. 9B, D, F). The equivalent circuits and fitted parameters corresponding to the EIS were exhibited in the rightmost column of Fig. 9 and in Table S4. The impedance of the unfilled epoxy coatings (Fig. 9A, B) was reduced by half at 3 d. The surface state of the coating deteriorated rapidly with increasing immersion time, and the final low-frequency impedance decreased from 109 Ω cm2 to 106 Ω cm2 orders of magnitude, which was attributed to the formation of a high-quality SRB biofilm on the surface of the coating (Fig. 7A, G) and the decreased coating bonding due to the metabolism of SRB growth (Fig. 8A). In Fig. 9C, D, all monitored EIS curves showed diffusion control (i.e., Warburg impedance), which was associated with the formation of coating micropores from Na2MoO4 dissolution in the Na2MoO4-filled epoxy coating in Fig. 8B, and the formation of these structures allowed for a potentially faster destruction of the coating than in unfilled epoxy coating (impedance was ultimately lowered to the order of magnitude of 105 Ω cm2). In contrast, the TNG-enhanced epoxy coating was almost unaffected by SRB and more stable in SRB medium. The TNG-enhanced epoxy coating displayed the same impedance regularity as the TNG-covered, which was attributed to the anti-SRB biofilm formation effect in Fig. 7A, I and the killing effect on the attached SRB, which was also reflected in the complete surface topography of the coating after immersion and the excellent binding force (Fig. 8C, F).

Time-dependent changes in OCP of the different filled epoxy coatings are shown in Fig. 10A. TNG-enhanced coatings remained stable over the 28 days of immersion cycle, while the continued positively shifted OCP values of unfilled and Na2MoO4-filled coatings were perhaps correlated with the formation of SRB biofilm and the disruption of the coating. Polarization curves indicated that the corrosion current densities (icorr, Table S5) of the initially immersed (Fig. 10B square) were 0.32 nA cm−2 for the unfilled epoxy coating, 0.40 nA cm−2 for the Na2MoO4-filled epoxy coating, and 0.16 nA cm−2 for the TNG-enhanced epoxy coating, suggesting that the coatings were of the same state and both have initial integrity. However, after 28 days of immersion in SRB medium (Fig. 10B circle), the icorr values of unfilled and Na2MoO4-filled epoxy coatings (173 nA cm−2 and 392 nA cm−2, respectively) increased 541 and 980 times, demonstrating that the coatings basically lost the resistance effect to SRB. On the contrary, the icorr value of TNG-enhanced epoxy coating was 0.05 nA cm−2, which not only did not increase but also slightly decreased, proving that TNG-enhanced enhanced the resistance of epoxy coating to MIC.

Assessment of the biofouling resistance of epoxy coating in the Yangtze River basin

Given the excellent antibacterial performance of TNG in the laboratory, it is necessary to evaluate its long-term durability in natural water environments for future use. Figure 11 shows optical images of different filled epoxy coatings covered on HMS coupons after 9 months of natural evolution in the Yangtze River basin (2024.9.03-2025-6.07). The surfaces of the unfilled epoxy coating and the Na2MoO4-filled coating were both densely covered with Limnoperna fortunei, resulting in severe biofouling. In contrast, the fouling organisms attached to the TNG-enhanced coating were significantly decreased, with almost no L. fortunei attachment detected. L. fortunei are a type of aquatic snail, distributed in the middle and lower reaches of the Yangtze River basin. They typically attach to the inner walls of pipelines, ship bottoms, and rocks, leading to reduced transportation capacity of pipelines or increased resistance for ships. In general, microorganisms that can attach to material surfaces in a short period of time often serve as “pioneer” species for biofouling organisms. They secrete extracellular polysaccharides and proteins to form biofilms, achieving irreversible attachment, thereby providing a conducive environment for the colonization of macro-biofouling organisms and significantly influencing the adhesion force-interfacial energy of the coating surface49,50. Subsequently, large biofouling organisms such as L. fortunei can attach to engineering material surfaces based on microbial biofilms51. On coating surfaces without any biocides, the biofouling formation process will continue52.

In this work, the anti-biofouling performance of the epoxy coating was enhanced once the antimicrobial enhancer TNG was incorporated into the coating. The visible biofouling on the surface of the TNG-enhanced epoxy coating was almost nonexistent, indicating that TNG enhances the antimicrobial properties of the epoxy coating in real-world aquatic environments and across different seasons, while also demonstrating the environmental stability of the TNG-enhanced epoxy coating. Based on the fact that microbial biofilms are a prerequisite for the attachment of large biofouling organisms, the abundance of microbial populations on the coupon surface was identified. Except for the “other” category in the report, the remaining seven microbial genus, Flavobacterium, Chryseobacterium, Comamonas, Shewanella Aeromonas, Proteobacteria, Acinetobacter, were dominant species in the Yangtze River basin. The Proteobacteria should be given more attention, because the SRB used in this work and the common corrosive bacterium P. aeruginosa both belong to the Proteobacteria. The Proteobacteria accounted for 6.58% of the total on the TNG-enhanced epoxy coating surface, which was only one-seventh of the unfilled epoxy coating (45.1%), indicating that the TNG-enhanced epoxy coating effectively inhibits the adhesion and growth of Proteobacteria. Although Na2MoO4-filled coatings (21.8%) could also decrease the proportion of Proteobacteria, Na2MoO4 was dissolved in actual water environments. Epoxy coating without Na2MoO4 had poorer resistance than unfilled epoxy coating. Optical photograph (Fig. 11A) showed that Na2MoO4-filled coating was damaged and peeled off, rendering them irrelevant for reference. From the actual results, after removing the visible deposits on the surface, the TNG filling coating was the only one that remained intact, proving its practical usability.

An almost water-insoluble antibacterial organic–inorganic hybrid material, TNG, was simply synthesized using THPS, GDMC, and Na2MoO4. TNG, when used directly as a metal coating layer, could effectively inhibit the adhesion and formation of SRB biofilm on metal surface, thereby preventing MIC induced by SRB. However, it tended to be damaged with long-term use. If TNG was used as an epoxy coating enhancer, it could improve the hydrophobicity of the coating without affecting its hardness. After an 8-week immersion test, the surface of the pure epoxy coating was densely covered by SRB biofilm, causing cracks and pits on the coating surface. Na2MoO4-filled epoxy coating formed numerous micro-pores due to the dissolution of Na2MoO4, which accelerates the failure rate of the coating. However, the TNG-enhanced epoxy coating remained intact after 56 days of incubation, with no mature SRB biofilm formation. After 28 days of immersion in SRB medium, the corrosion current density of unfilled and Na2MoO4-filled coatings increased by 541 times and 980 times, respectively, while no significant current changes in the TNG-enhanced coating. A 9-month cross-seasonal dynamic corrosion test in the Yangtze River basin demonstrated that TNG-enhanced coating exhibits high stability and can inhibit biofouling. According to the main conclusions, a brief schematic of this work was drawn in Fig. S6. The simple preparation process and low cost make it possible to use TNG as a practical coating filler to inhibit MIC.

Methods

Materials preparation

HMS (NANJING IRON & STEEL UNITED CO., LTD.) with elements amounts (wt%) of C 0.3–0.5, Mn 22–25, Cr 3.0–4.0, Cu 0.4–0.7, Al 0.1–0.3, Si 0.1–0.3, Ni 0.1–0.3, V 0.01–0.02, Mo 0.01–0.02, P 0.004 and Fe balance was used in this work. The coupon size used for the coating exposure test was 50 mm × 10 mm × 5 mm long strips of metal. A metal coupon of 10 mm × 10 mm × 5 mm connected by copper wire sealed with AB epoxy resin was used for electrochemical measurements, leaving only one test surface of 10 mm × 10 mm. All coupons need to be degreased. Following polishing of metals to the smooth surface using 180#, 600#, 1200# and 1500# silicon carbide sandpaper, the coupons were cleaned with acetone and anhydrous ethanol to remove impurities.

THPS (T, 75% aqueous solution, Macklin), Na2MoO4 (N, 1 M), and GDMC (G, 30% aqueous solution, Zhejiang Simo Holdings Co., Ltd.) were used to synthesize coating fillers at room temperature. The antibacterial effects of THPS and GDMC were demonstrated in the Supplementary Materials. The target reactant TNG was obtained by adding 0.21 mL of T to 9.79 mL of N and mixing thoroughly, followed by the addition of excessive G and shaking thoroughly. Subsequently, the impurities were repeatedly soaked and rinsed with deionized water to obtain the target product TNG. To determine the effective composition of TNG, X-ray diffraction (XRD, X-Pert PRO, PANalytical B.V, Netherlands), X-ray photoelectron spectroscopy (XPS, AXIS-ULTRA DLD, Kratos Analytical, Kyoto, Japan) and Fourier transform infrared spectroscopy (FTIR, INVENIO-R, Bruker, Germany) were used.

TNG dissolution testing

The cleaned TNG were placed in an oven at 60 °C for 24 h to evaporate water and the original weight was weighed. Subsequently, the dried TNG was submerged in ultrapure water for 48 h. The dried TNG was then immersed in deionized water for 48 h and dried again. The difference in weight is the weight of the dissolved substances.

TNG-enhanced coating preparation

To demonstrate the basic antimicrobial property of TNG, it was uniformly coated on the surface of high-manganese steel coupons and electrodes (the attached TNG would not be dislodged by slight vibration at 6 o’clock) and dried in an oven at 60 °C for 24 h to obtain coupons and electrodes covered with only TNG.

Commercial epoxy coating 8701 (Tianjin Baochang Coatings Co., Ltd.) was added with 2 wt% of TNG, then stirred for 5 min and ultrasonicated for 10 min to fully mix the epoxy coating with TNG. The prepared coatings were coated on the surface of HMS sheets and electrodes using roller coating process for 48 h of room temperature curing to form antimicrobial epoxy coatings (TNG-enhanced epoxy coating). In addition, 2 wt% Na2MoO4-added epoxy coating (Na2MoO4-filled epoxy coating) was obtained by completely dispersing 2 wt% Na2MoO4, which was milled into a fine powder, into another portion of epoxy coatings and brush-coated on the surface of HMS for curing.

Epoxy coating hardness test

Coating hardness tests were performed according to ASTM D3363-2005 before the start of immersion experiments. A pencil sharpener was used to sharpen the 6H-H pencil (if subsequent tests were insufficient, a softer pencil was used instead). Place the coated surface horizontally and secure it. Hold the pencil at a 45° angle to the test coupon and apply force to scratch it, ensuring the pencil lead does not break. Scratch forward toward the tester at a uniform speed for ~1 cm. The scratching speed should be 1 mm/s. After each scratch, the pencil lead tip should be re-sharpened. At least five test lines were to be scribed on the same coupon surface. If the metal matrix could be observed with less than two test lines, it should be tested with a harder pencil until the matrix is no longer exposed.

Microbial isolation and incubation

Desulfovibrio sp. (similarity >99%) was isolated from HMS seawater pipelines from the LNG field station offshore China. Species identification was performed using bacterial 16S rDNA sequencing, which was analyzed by Sangon Biotech (Shanghai) Co., Ltd. Specific isolation steps and identification results were shown in our previous work3,53. SRB was incubated and cultured in enriched artificial seawater (EASW, pH 7.2), with EASW (g/L) consisting of 23.476 g NaCl, 0.192 g NaHCO3, 3.917 g Na2SO4, 0.026 g H3BO3, 0.1 g NH4Cl, 0.096 g KBr, 4.965 g MgCl2, 0.04 g SrCl·6H2O, 0.664 g KCl, 1.469 g CaCl2·2H2O, 0.712 g MgSO4·7H2O, 0.1 g CaSO4, 0.05 g K2HPO4, 4.5 mL sodium lactate, 1.0 g yeast extract, 0.57 g tri-sodium citrate·2H2O, and 0.5 g FeSO4·7H2O. SRB seed was activated and incubated in a constant temperature and humidity chamber at 30 °C for 3 d as experimental strains. The test vials of 125 mL and 380 mL used for immersion and electrochemical experiments, as well as other experimental materials, were autoclaved at 121 °C for 30 min. Liquid mediums that cannot be autoclaved required filtration through a 0.22 μm filter membrane. All HMS coupons needed to be UV-sterilized for at least 1 h prior to the experiment. Afterwards, all items were transferred to a glove box filled with nitrogen. Each immersion vial contained three long coupons of the same preparation conditions and filled with 99 mL EASW medium and 1 mL SRB. Electrochemical vials were filled with three parallel high-manganese steel electrodes and added with 300 mL EASW and 3 mL SRB. All samples were incubated in a constant temperature and humidity chamber at 30 °C for 14 d and 56 d.

Antimicrobial surface morphology and biofilm distribution

After incubation, HMS surface biofilm and corrosion products were immobilized by 2.5% (v/v) glutaraldehyde and then dehydrated stepwise using 25%, 50%, 75%, 90% and 100% (v/v) anhydrous ethanol. They were air-dried in a nitrogen atmosphere and stored under vacuum. The surface morphologies and elemental distribution of the coatings were observed using an environmental scanning electron microscope (ESEM, Quanta 200, FEI, Eindhoven, Netherlands) and its piggybacked energy-dispersive X-ray spectroscopy (EDS, EDAX, USA). In addition, confocal laser microscopy (CLSM, FV1200, OLYMPUS, Japan) was used to examine the cell distribution on the surface of coatings dropwise coated with DAPI (4’,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole, Solarbio Science & Technology Co., Ltd, Beijing). Fluorescence was able to be observed even when the cells were killed because DAPI is directed against nucleic acids.

Planktonic and sessile cells were counted respectively on day 14 of incubation using a hemocytometer plate (XB-K-25, Qiujing Medical Instrument Co., Ltd, Zhejiang, China). Planktonic cells were counted by extracting the bacterial solution directly from the immersion vials. Sessile cells, on the other hand, were counted by using a sterile brush to brush the biofilm from coating surfaces into a centrifuge tube containing 10 mL of PBS, which was well shaken.

Adhesion strength after incubation

Adhesion strength parameters of epoxy coatings obtained from different preparation conditions after 8 weeks of SRB immersion were determined using cross-cut testing machine. Cross-cut testing was carried out in accordance with ASTM D 3359B-0210. Cutting blades contained 11 sharp teeth with a spacing of 1 mm, and the degree of flaking was examined with tape after applying cross scratches to the coatings surface. The characteristic parts were observed using CLSM.

Electrochemical measurements

Electrochemical workstation (Model CS350, Corrtest, China) was used to monitor coating surface changes in corrosive environments. High-manganese steel electrodes prepared with various conditions served as working electrodes; saturated calomel electrodes were reference electrodes, and a 10 mm × 10 mm platinum mesh served as counter electrodes. Electrochemical impedance spectroscopy (EIS) and potentiodynamic polarization curve measurements were obtained at a stable open circuit potential (OCP). The OCP needed to be observed continuously for 28 d, with one data point of the day recorded every 2 d. EIS measurements were performed with a sinusoidal signal amplitude of 10 mV and a frequency range of 100,000–0.01 Hz. Potentiodynamic polarization curves were measured with an interval of ±250 mV vs. SCE and a sweep rate of 0.5 mV/s (vs. SCE). All test results were repeated at least three times. EIS and potentiodynamic polarization curves were fitted using Zsimpwin and Cview2 software, respectively.

Evaluation of coating performance in the Yangtze River basin

The actual corrosion experiments in the Yangtze River were conducted at the Wuhan Corrosion Environment Monitoring Station (provided by the Wuhan Research Institute of Materials Protection). The standard test coupons with a size of 10 mm × 50 mm × 3 mm were used as substrates, with different types of epoxy coatings applied uniformly and evenly on their surfaces. The test coupons were secured to suspension plates using copper wires and then submerged in the Yangtze River. The specific experimental period was from 2024.9.03 to 2025.6.07, spanning four seasons throughout the year, providing real-world data for assessing the actual durability of the coatings. After 9 months of actual water-based experiments, the integrity of the different types of test coupons was directly assessed, and they were sent to Shanghai Sangon Biotech Co., Ltd. for genomic analysis.

Data availability

Data will be made available on request.

References

Han, K., Yoo, J., Lee, B., Han, I. & Lee, C. Effect of Ni on the hot ductility and hot cracking susceptibility of high Mn austenitic cast steel. Mater. Sci. Eng. A. 618, 295–304 (2014).

Lee, J. et al. Effects of Mn addition on tensile and charpy impact properties in austenitic Fe-Mn-C-Al-based steels for cryogenic applications. Metall. Mater. Trans. A. 45, 5419–5430 (2014).

Xu, Z. et al. Microbial corrosion of high manganese austenitic steel by a sulfate-reducing bacterium dominated by extracellular electron transfer and intergranular effect. Corros. Sci. 248, 112799 (2025).

Dou, W. et al. Investigation of the mechanism and characteristics of copper corrosion by sulfate reducing bacteria. Corros. Sci 144, 237–248 (2018).

Xu, Z., Dou, W., Chen, S., Pu, Y. & Chen, Z. Limiting nitrate triggered increased EPS film but decreased biocorrosion of copper induced by Pseudomonas aeruginosa. Bioelectrochemistry 143, 107990 (2022).

Gu, T., Jia, R., Unsal, T. & Xu, D. Toward a better understanding of microbiologically influenced corrosion caused by sulfate reducing bacteria. J. Mater. Sci. Technol. 35, 631–636 (2019).

Wang, D. et al. Microbiologically influenced corrosion of CoCrFeMnNi high entropy alloy by sulfate-reducing bacterium Desulfovibrio vulgaris. Corros. Sci. 223, 111429 (2023).

Xu, Z. et al. Electrochemical investigation of the “double-edged” effect of low-dose biocide and exogenous electron shuttle on microbial corrosion behavior of carbon steel and copper in enriched seawater. Electrochimica Acta 476, 143687 (2024).

Wang, J., Liu, H., Mohamed, M. E.-S., Saleh, M. A. & Gu, T. Mitigation of sulfate reducing Desulfovibrio ferrophilus microbiologically influenced corrosion of X80 using THPS biocide enhanced by peptide A. J. Mater. Sci. Technol. 107, 43–51 (2022).

Zhang, T. et al. Polyhexamethylene guanidine molybdate as an efficient antibacterial filler in epoxy coating for inhibiting sulfate-reducing bacteria biofilm. Prog. Org. Coat. 176, 107401 (2023).

Song, Y., Li, Q., Li, Y. & Zhi, L. Synthesis and properties of dodecylguanidine hydrochloride. Fine. Chem. 30, 0028–0004 (2013).

Xu, L. et al. Inadequate dosing of THPS treatment increases microbially influenced corrosion of pipeline steel by inducing biofilm growth of Desulfovibrio hontreensis SY-21. Bioelectrochemistry 145, 108048 (2022).

Verma, C. et al. Epoxy resins as anticorrosive polymeric materials: a review. React. Funct. Polym. 156, 104741 (2020).

Moradi Kooshksara, M. & Mohammadi, S. Investigation of the in-situ solvothermal reduction of multi-layered graphene oxide in epoxy coating by acetonitrile on improving the hydrophobicity and corrosion resistance. Prog. Org. Coat. 159, 106432 (2021).

Wan, P. et al. Synthesis of PDA-BN@f-Al2O3 hybrid for nanocomposite epoxy coating with superior corrosion protective properties. Prog. Org. Coat. 146, 105713 (2020).

Feng, T., Wu, J., Chai, K. & Liu, F. Effect of Pseudomonas sp. on the degradation of aluminum/epoxy coating in seawater. J. Mol. Liq. 263, 248–254 (2018).

Deng, S. et al. Effect of Bacillus flexus on the degradation of epoxy resin varnish coating in seawater. Int. J. Electrochem. Sci. 14, 315–328 (2019).

Wu, T. et al. Stress corrosion of pipeline steel under disbonded coating in a SRB-containing environment. Corros. Sci. 157, 518–530 (2019).

Tambe, S. P., Jagtap, S. D., Chaurasiya, A. K. & Joshi, K. K. Evaluation of microbial corrosion of epoxy coating by using sulphate reducing bacteria. Prog. Org. Coat. 94, 49–55 (2016).

Behzadinasab, S. et al. Antimicrobial activity of cuprous oxide-coated and cupric oxide-coated surfaces. J. Hosp. Infect. 129, 58–64 (2022).

Bressy, C. et al. Compère, What governs marine fouling assemblages on chemically-active antifouling coatings? Prog. Org. Coat. 164, 106701 (2022).

Liu, S., Gu, L., Zhao, H., Chen, J. & Yu, H. Corrosion resistance of graphene-reinforced waterborne epoxy coatings. J. Mater. Sci. Technol. 32, 425–431 (2016).

Haeri, Z., Ramezanzadeh, B. & Ramezanzadeh, M. Recent progress on the metal-organic frameworks decorated graphene oxide (MOFs-GO) nano-building application for epoxy coating mechanical-thermal/flame-retardant and anti-corrosion features improvement. Prog. Org. Coat. 163, 106645 (2022).

Shenderova, O. et al. Modification of detonation nanodiamonds by heat treatment in air. Diamond Relat. Mater. 15, 1799–1803 (2006).

Yang, L., May, P. W., Yin, L., Smith, J. A. & Rosser, K. N. Ultra fine carbon nitride nanocrystals synthesized by laser ablation in liquid solution. J. Nanopart. Res. 9, 1181–1185 (2007).

Tammer, M. & Sokrates, G. Infrared and Raman characteristic group frequencies: tables and charts. Colloid Polym. Sci. 283, 235–235 (2004).

Rocchiccioli-Deltcheff, C., Fournier, M., Franck, R. & Thouvenot, R. Vibrational investigations of polyoxometalates. 2. Evidence for anion-anion interactions in molybdenum(VI) and tungsten(VI) compounds related to the Keggin structure. Inorg. Chem. 22, 207–216 (1983).

Ishikawa, S. et al. Oxidation catalysis over solid-state Keggin-type phosphomolybdic acid with oxygen defects. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 144, 7693–7708 (2022).

Sun, Y. et al. Preparation and visible-light photochromism of phosphomolybdic acid/polyvinylpyrrolidone hybrid film. Chem. Res. Chin. Univ. 30, 703–708 (2014).

Li, N. et al. Self-assembly of a phosphate-centered polyoxo-titanium cluster: discovery of the heteroatom Keggin family. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 58, 17260–17264 (2019).

Nalumansi, I., Birungi, G., Moodley, B. & Tebandeke, E. Preparation and Identification of reduced phosphomolybdate via, molybdenum blue reaction. Orient. J. Chem. 36, 607–612 (2020).

Wei, Y., Han, B., Dong, Z. & Feng, W. Phosphomolybdic acid-modified highly organized TiO2 nanotube arrays with rapid photochromic performance. J. Mater. Sci. Technol. 35, 1951–1958 (2019).

Yeganeh, M., Omidi, M. & Rabizadeh, T. Anti-corrosion behavior of epoxy composite coatings containing molybdate-loaded mesoporous silica. Prog. Org. Coat. 126, 18–27 (2019).

Khalaji-Verjani, M. & Masteri-Farahani, M. Lacunary Keggin-type phosphomolybdate functionalized with Ru(acac)3 complex for electrocatalytic H2 production in aqueous media. ACS Appl. Energy Mater. 7, 6612–6620 (2024).

Zhao, N. et al. Versatile types of organic/inorganic nanohybrids: from strategic design to biomedical applications. Chem. Rev. 119, 1666–1762 (2019).

Rouhani, M. et al. Photochromism of amorphous molybdenum oxide films with different initial Mo5+ relative concentrations. Appl. Surf. Sci. 273, 150–158 (2013).

Cornaglia, L. M. & Lombardo, E. A. XPS studies of the surface oxidation states on vanadium-phosphorus-oxygen (VPO) equilibrated catalysts. Appl. Catal. A 127, 125–138 (1995).

Chowdari, B. V. R., Tan, K. L., Chia, W. T. & Gopalakrishnan, R. X-ray photoelectron spectroscopic studies of molybdenum phosphate glassy system. J. Non-Cryst. Solids. 119, 95–102 (1990).

Zhu, L. et al. Interfacial engineering of graphenic carbon electrodes by antimicrobial polyhexamethylene guanidine hydrochloride for ultrasensitive bacterial detection. Carbon 159, 185–194 (2020).

Banerjee, I., Pangule, R. C. & Kane, R. S. Antifouling coatings: recent developments in the design of surfaces that prevent fouling by proteins, bacteria, and marine organisms. Adv. Mater. 23, 690–718 (2011).

Wang, S., Qiu, B., Shi, J. & Wang, M. Quaternary ammonium antimicrobial agents and their application in antifouling coatings: a review. J. Coat. Technol. Res. 21, 87–103 (2024).

Pope, M. T. & Müller, A. Polyoxometalate chemistry: an old field with new dimensions in several disciplines. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 30, 34–48 (1991).

Rebello, N. J., Beech, H. K. & Olsen, B. D. Adding the effect of topological defects to the Flory–Rehner and Bray–Merrill swelling theories. ACS Macro Lett. 10, 531–537 (2021).

Zhang, Z. et al. Preparation and antibacterial properties of poly(hexamethylene guanidine hydrochloride) modified ionic waterborne polyurethane. Prog. Org. Coat. 156, 106246 (2021).

Zhou, Z. X., Wei, D. F., Guan, Y., Zheng, A. N. & Zhong, J. J. Damage of Escherichia coli membrane by bactericidal agent polyhexamethylene guanidine hydrochloride: micrographic evidences. J. Appl. Microbiol. 108, 898–907 (2010).

Wang, J., Li, J., Shen, Z., Wang, D. & Tang, B. Z. Phospholipid-mimetic aggregation-induced emission luminogens for specific elimination of gram-positive and gram-negative bacteria. ACS Nano 17, 4239–4249 (2023).

O.V. et al. Rogalsky, eDNA inactivation and biofilm inhibition by the polymericbiocide polyhexamethylene guanidine hydrochloride (PHMG-Cl). Int. J. Mol. Sci. (2022).

Tan, Y. et al. Crystalline alkyl side chain enhanced hydrophobicity–oleophobicity for transparent and durable low-surface-energy coatings based on short fluorinated copolymers. Macromolecules 57, 5189–5199 (2024).

Lewis, J. Marine biofouling and its prevention on underwater surfaces. Mater. Forum. 22, 41–61 (1998).

Johnson, B. & Azetsu-Scott, K. Adhesion force and the character of surfaces immersed in seawater. Limnol. Oceanogr. 40, 802–808 (1995).

Beech, I., Sunner, J. & Hiraoka, K. Microbe-surface interactions in biofouling and biocorrosion processes. Microbiology 8, 157–168 (2005).

Richmond, M. & Seed, R. A review of marine macrofouling communities with special reference to animal fouling. Biofouling 3, 151–168 (1991).

Zhang, T., Wang, Z., Qiu, Y., Iftikhar, T. & Liu, H. “Electrons-siphoning” of sulfate reducing bacteria biofilm induced sharp depletion of Al-Zn-In-Mg-Si sacrificial anode in the galvanic corrosion coupled with carbon steel. Corros. Sci. 216, 111103 (2023).

Acknowledgements

This work is supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (52171069) and (52401092), and Open Fund for the National Innovation Center for Market Supervision (Safety of Oil and Gas Pipelines and Storage Equipment) of the China Special Equipment Inspection & Research Institute (CXZX-YQGDYCCSBAQ-2024-001). Special thanks to Yanhe Liu from the China Special Equipment Inspection and Research Institute for his significant support in this work. We also acknowledge the support of the Analytical and Testing Center of Huazhong University of Science and Technology.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

The study was proposed by X.Z., Z.T., L.H., and H.R. Sample preparation, experimental procedures, and data collection were carried out by X.Z., H.Y., Z.T., and W.H. Coating hardness and adhesion tests were conducted by W.J. and W.H. Field experiments in the Yangtze River basin were performed by W.J. and Z.X. Data analysis and interpretation were performed by X.Z. and W.H. under the supervision of H.R. and L.F. The initial draft was prepared by X.Z. and revised by all authors; the final revision was completed by X.Z. All authors approved the submitted manuscript version. Funding acquisition and resource management were handled by L.H., Z.T., and X.Z.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Xu, Z., Zhang, T., He, Y. et al. Improving long-term control of microbial corrosion and biofouling by a novel insoluble antimicrobial enhancer. npj Mater Degrad 10, 21 (2026). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41529-025-00734-z

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41529-025-00734-z