Abstract

Recent discoveries support the principle that palliative care may improve the quality of life of patients with Parkinson’s disease and those who care for them. Advance care planning, a component of palliative care, provides a vehicle through which patients, families, and clinicians can collaborate to identify values, goals, and preferences early, as well as throughout the disease trajectory, to facilitate care concordant with patient wishes. While research on this topic is abundant in other life-limiting disorders, particularly in oncology, there is a paucity of data in Parkinson’s disease and related neurological disorders. We review and critically evaluate current practices on advance care planning through the analyses of three bioethical challenges pertinent to Parkinson’s disease and propose recommendations for each.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

The improvement of the quality of life of patients and their families is a cornerstone of palliative care. Fundamental to the discipline is the alleviation of pain and the suffering arising from other complex symptoms. To facilitate meeting these objectives, advance care planning (ACP) was created in order to “support adults at any age or stage of health in understanding and sharing their personal values, life goals, and preferences regarding future medical care.”1 ACP prepares a patient for making future medical choices, and a surrogate to decide on the patient’s behalf should that capacity be lost.1 ACP includes the completion of an advance directive (AD), such as the assignment of a health care power of attorney (HCPOA), or the completion of a living will, or both.2 The goal of ACP is to ensure that medical care is in alignment with patients’ values, goals, and preferences.1 Prior research demonstrates that planning for the future is associated with improvements in patient satisfaction, lower hospital admission rates, and decreases in psychological comorbidities for the family.3

Ethical considerations are critical in ACP, given the interdependent issues of personal identity, capacity, autonomy, consciousness, therapeutic nihilism, and stigma. Therefore, the principles of modern biomedical ethics codified by Beauchamp and Childress4 in 1979 serve to guide the process: autonomy, beneficence, non-maleficence, and justice. Autonomy highlights the respect of patients’ rights to informed self-determination; beneficence, the maximization of goodness whereas non-maleficence the protection from harm; and justice the equity and fairness on a population level. In conjunction with these principles, modern bioethics is also informed by prior instructive cases and by actions and policies aimed at fostering medicine as a moral enterprise (virtue ethics).5,6

Among the quality metrics defined for the care of patients with Parkinson’s disease (PD),7 the American Academy of Neurology includes initiation of ACP. Data on implementation are limited. In Kentucky, the rate of completion of living wills is 64%, unrelated to disease severity, and comparable to patients without PD.8 In Colorado and Florida, AD completion is 56% and 82%, respectively.9,10 In South Korea, despite a discussion prevalence of 71%, AD completion is only 27%.11 As a result, HCPOAs have insufficient knowledge about their loved ones’ views on life-sustaining measures.12

We analyze the three ethical challenges commonly encountered in clinical practice (Table 1) and propose a path forward for each (Table 2). These include (1) the challenge of ACP introduction before the appearance of cognitive impairment without undermining the therapeutic alliance; (2) the challenge of the patient to choose future medical care that may not reflect their future selves; and (3) the challenge to prepare patients and loved ones for the decision to pursue deep brain stimulation (DBS) with preoperative ACP, given that quality of life, identity, cognitive or psychosocial functions may be markedly different after the procedure.

Initiating ACP before cognitive dysfunction without undermining the therapeutic alliance

PD is a progressive disease associated with dementia in up to 80% of patients in advanced stages.13 This generates the challenge of introducing ACP at a time when cognitive function is preserved (beneficence) without jeopardizing the therapeutic alliance (non-maleficence). Some neurologists feel obligated to discuss ACP in patients with PD—and these patients want their clinicians to do so.10,14,15 Fewer than 10% of neurologists initiate such discussions around the time of diagnosis.16 Almost half of the clinicians delay the ACP conversations until cognitive decline manifests.16 At that point, patients with PD are unlikely to have the capacity to participate fully in these decisions.17

Neurologists may perceive that raising the topic of ACP will amplify suffering, threaten hope, or cause a perception of abandonment and, therefore, might delay such discussion until an episode of acute clinical decline.16,18 For patients, barriers to engaging in ACP include concerns that clinicians may subsequently provide lesser quality of care or fears that such discussions are akin to giving up.19,20,21 Because PD is a disease where many will experience disease-related complications resulting in hospitalization, institutionalization, and death, the window in which patients have the capacity to make future medical decisions may be relatively narrow.17

Even in the absence of dementia, ACP discussions may be affected. Indeed, a study17 showed that a substantial subset of patients with PD, with a mean disease duration of 9.8 years and a Montreal Cognitive Assessment score of 24.5 (close to normal range), exhibited impaired decisional capacity in domains of understanding, appreciating, and reasoning. These findings create a compelling case to begin ACP as early as possible, around the time of diagnosis.10 The misguided belief that avoidance of ACP discussions will spare patients from unnecessary emotional distress is at odds with the lower depressive symptomatology ascertained at AD completion.15

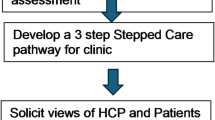

Addressing barriers to ACP includes establishing specific appointments for ACP, integrating chaplains into the discussions, and treating psychological distress (Lum et al. also offers specific, concrete steps).2 Preserving the therapeutic alliance requires communicating the rationale behind early ACP as part of routine and periodic practice, articulating that patients’ interests are the priority, and explaining that ACP neither reduces the intensity or quality of care, nor suggests impending decline.20 Transparent reasoning behind early ACP is, therefore, essential. Deferring medical decisions to surrogates when patients are unable to decide for themselves may lead to surrogate distress or interventions that are not concordant with patient wishes.22 For example, PD decedents who specified a preference for comfort-focused care were more likely to die at home than those who had not articulated such wishes.23

The above can be achieved effectively if ACP becomes a routine part of a practice, integrated into the standard of care, and clarified to represent a flexible rather than a one-time endeavor. This approach may help normalize the conversation for both patient and physician. Communication that the process is dynamic might allay concerns of post decision dissonance and allow patients to focus more on their current goals and values. In practice, the ACP discussion is divided into what the patient wants now and what they might want in the future if certain health outcomes are reached (e.g., severe dementia or loss of capacity). A frequent review of goals throughout the disease is expected. Since a patient’s decision-making capacity may be greatly affected as the disease progresses, the clinician can review the information obtained overtime to help surrogates infer care preferences in evolving circumstances.

Conceptualization of past, current, and future selves

Whereas the former challenge relates to the clinician’s timing of ACP discussions to make decisions, another challenge is to enable the patient to make the best decisions. ACP requires reflection on past, present, and foreseeable selves.24,25 Impairments in cognitive flexibility, seen early within the disease course, result in patients who may struggle to envision their future selves.26 In contrast to prior work that suggests that patients with chronic disease and poor performance status desire less aggressive measures27, patients with PD may wish to pursue high-burden care in the setting of poor prognoses when compared to controls.28 The challenge arises that if patients with PD experience deficits in envisaging, then how can patients and clinicians optimally collaborate so that future care reflects the person holistically?

A set of philosophical assumptions underpinning this discussion are that the self at time point 1 (t1) should justifiably be able to decide for the self at time point 2 (t2). This relies on an account of personhood, which dictates that the self at t1 is the same self at t2. Suppose the preferences of the self at t2 change, in the context of PD. Does this self at t2 not really know what the self at t2 wants? What permits the self at t1 to override the self at t2?

A recent study highlights this challenge by showing that patients with PD (1) may experience deficits in envisaging early in the disease, and (2) that this deficit is not related to disease severity.24 This was tested by assessing autobiographical memory (AM), and episodic-future thinking (EFT) as these are likely critical to the cognitive processes involved in decision-making and social functioning and can be markedly impaired in a host of neurological diseases.24 In the study, researchers explored the abilities of patients with PD to access AM, and EFT.24 AM involved re-experiencing memories, and EFT involved the pre-experiencing of foreseeable situations. Compared to healthy controls, participants generated fewer concepts and with less complexity for the AM task; complexity was also diminished during EFT.

Because of these findings, we may be inclined to view the t2 self as a less-robust or diseased version of t1, but perhaps we ought to be viewing the t2 self as an entirely different individual distinct from the t1 self. The “disability paradox” corroborates this notion: individuals who imagine a future disability tend to assume the quality of life would be lower than the patients who have that disability rate their quality of life.29,30 This discrepancy provides empirical data that the t1 and t2 selves often have different values, independent of incapacity or cognitive dysfunction. As the self at t2 is not completely independent from the self at t1, it follows that if the t2 self is severely impaired and inconsistent, then allowing an AD or HCPOA to serve as the voice not only of t1 but also of t2 may be sensible. Yet if, on the other hand, the t2 self has some impairment but is consistent and compelling or demonstrates a quality of life greater than what t1 predicted, a reconsideration is in order.

While alterations of personhood complicate ACP, “projection bias” often also confounds the process. Projection bias is a cognitive error in which emotional states alter the ability to consider future events rationally.31 For instance, cancer patients’ willingness to live varied by 30% throughout a given day in tandem with psychological states.31 Present reflections may thereby supersede more calculated analyses of past or future selves.28,31 Clinicians may be unaware of the transient nature of a particular preference or may be unable to operationalize those preferences.22,31 This may have vexing implications when deciding on potential future life-sustaining measures in a disease where mood often fluctuates in ON- and OFF-medication states.32

Two approaches of virtue ethics may help surmount the challenges: (1) incorporating loved ones in the ACP process so that they may provide additional perspectives on the patient, and (2) getting to know the patient well.

Clinicians should, first, encourage patients with PD at all stages of the disease to undertake ACP accompanied by loved ones who understand their history, values, and preferences. A collaborative process that encourages patients to discuss their wishes with others may forestall the intrusion of cognitive errors during medical decision-making. In addition, the incorporation of others’ views can reveal certain “blind spots” that might have otherwise been overlooked. Second, clinicians ought to become acquainted with patients at the outset. What hobbies or professions did they pursue? What brought joy and meaning? How did they react when others were ill? Did they always participate in their medical care, or did they prefer not to visit doctors? Some of these answers help explore “personhood” and may help shed light on approaches to decision-making. Taken together, these strategies will further enhance the clinician’s ability to make a holistic, personalized recommendation rather than a general recommendation made for all patients.

Preoperative ACP for DBS

Our third challenge relates to the potential missed opportunity for preoperative ACP before DBS surgery that can inform future medical decision-making, including potential perioperative complications. The eligibility mechanism for selection of DBS surgery involves examination of the motor, cognitive, and psychiatric states. What is often overlooked is that patients and families may receive inadequate preparation on the potential risks, range of outcomes, and side-effects of surgery. The challenge arises that if the quality of life, identity, cognitive, or psychosocial functions may markedly change after DBS, then how should patients and caregivers adequately prepare themselves for future decisions across a variety of outcomes?

Currently, ACP is not considered a best practice or standard for preoperative DBS planning.16,33 The current standard of care, therefore, elevates the likelihood of enabling discordant care and dysfunctional social situations.34,35,36,37,38 Following DBS, neuropsychiatric features such as suicidal ideation, apathy, mania, and delirium may appear, which may be refractory to adjustments in electrical stimulation or pharmacotherapy.39 Intracranial hemorrhage or hardware malfunction, while uncommon, may also occur.39 The steepest decline in couple satisfaction, for example, occurs during the first year after DBS surgery;35 within 2 years, one-third of spouses develop depression, and 42% of couples without prior histories of marital crises develop them.37

Only preliminary data is available regarding mitigating strategies.40 DBS is ideally suited for a well-designed, shared-decision-making tool such as a preoperative decision aid.41 A Cochrane review of trials of decision aids in other settings found that such aids help reduce decision conflict and ameliorate future regret while assuring that patients are well informed about all outcomes and that the treatments are consistent with their values.42 A balanced decision aid designed for patients with PD around DBS would need to be carefully designed so that it is both accurate and accessible for understanding. It would also need to elicit the individual’s preferences for life and care in the current situation with and without DBS as well as acknowledge the needs of the caregivers.

Implications for future research and innovation

The development of shared-decision-making aids will be vital to improving ACP, particularly tools that include stories from patients and families describing how satisfied they are with their decisions, and why they feel that way. It has not escaped our notice that while no substitute exists for frequent conversations with the individual patients and families, advances in decision-making and data analytics create an opportunity to apply artificial intelligence to ACP for neurological diseases. Efforts examining the accuracy of surrogates in predicting patients’ desires show that, on average, they can correctly predict choices at a rate between 59.3% and 68%.22,43 In contrast, tools that incorporate computer guidance may assist both patients and clinicians to improve conversations44 and predict choices.45,46,47,48

Methodologically, the integration of behavioral economics and data science may improve predictive capacity for future choices.45 Longitudinal data collection of the goals, behaviors, beliefs, and affective states is likely to later aid in predicting patient-centered communication styles, preferences, and preferred clinical choices. Foreseeably, an auto-generated report, personalized for a given patient, that uses natural language technologies would be dynamic and reflective of inputs captured over time. Such a user-friendly document would allow for dissemination to patients, their loved ones, and the clinical team to assist in their deliberations during times of clinical change. These tools can allow loved ones and clinicians to develop a more comprehensive understanding of the patient and predict their preferences in future stages. Additionally, if a surrogate is required to decide on behalf of a patient, then a machine-aided interpretation of “what the patient would want”—with certain predicted likelihoods attached to each option—may assist with such a decision.

Further research is required to measure perceptions of the accuracy of decisions near the end-of-life and to determine whether these decisions are concordant with intended care preferences. Such inquiry ought to be aligned with the principles of modern biomedical ethics, while based on cases that are tailored to neural disorders and their circumstances. This should be ideally coupled with efforts to better understand the preferences, practices, and attitudes of movement disorder neurologists surrounding the integration of palliative care and ACP into clinical practice. Developing and validating improved shared-decision-making strategies, aids, and vignettes of clinical outcomes will be crucial to ensure that patient preferences and values are optimally captured and honored.

References

Sudore, R. L. et al. Defining advance care planning for adults: a consensus definition from a multidisciplinary Delphi panel. J. Pain. Symptom Manag. 53, 821–832.e1 (2017).

Lum, H. D., Sudore, R. L. & Bekelman, D. B. Advance care planning in the elderly. Med. Clin. North Am. 99, 391–403 (2015).

Wright, A. A. et al. Associations between end-of-life discussions, patient mental health, medical care near death, and caregiver bereavement adjustment. J. Am. Med. Assoc. 300, 1665–1673 (2008).

Beauchamp, T. L. & Childress, J. F., others. Principles of Biomedical Ethics. (Oxford University Press, USA, 2001).

Pellegrino, E. D. & Thomasma, D. C. The Virtues in Medical Practice. (Oxford University Press, 1993).

Buetow, S. A., Martínez-Martín, P., Hirsch, M. A. & Okun, M. S. Beyond patient-centered care: person-centered care for Parkinson’s disease. npj Parkinson's Dis. 2, 1–4 (2016).

Factor, S. A., Bennett, A., Hohler, A. D., Wang, D. & Miyasaki, J. M. Quality improvement in neurology: Parkinson disease update quality measurement set. Neurology 86, 2278–2283 (2016).

Gillard, D. M., Proudfoot, J. A., Simoes, R. M. & Litvan, I. End of life planning in parkinsonian diseases. Park. Relat. Disord. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.parkreldis.2019.01.026 (2019).

Patterson, A., De Almeida, L. B., McFarland, N., Okun, M. & Malaty, I. Understanding of Palliative Care Among Parkinson Disease Patients at the University of Florida (S22.006). 88, S22.006 (Wolters Kluwer Health, Inc., 2017). https://n.neurology.org/content/88/16_Supplement/S22.006.

Kluger, B. M. et al. Defining palliative care needs in Parkinson’s disease. Mov. Disord. Clin. Pract. 6, 125–131 (2019).

Kim, M. J., Kim, H. J., Kim, J. K., Na, H. R. & Koh, S. B. Advance care planning in advanced Parkinsonian patients in a long-term care hospital. Mov. Disord. 32 (suppl 2) (2017). https://www.mdsabstracts.org/abstract/advance-care-planning-in-advanced-parkinsonian-patients-in-a-long-termcare-hospital/. Accessed 9 Nov 2019.

Kwak, J., Wallendal, M. S., Fritsch, T., Leo, G. & Hyde, T. Advance care planning and proxy decision making for patients with advanced Parkinson disease. South Med. J. 107, 178–185 (2014).

Mollenhauer, B., Rochester, L., Chen-Plotkin, A. & Brooks, D. What can biomarkers tell us about cognition in Parkinson’s disease? Mov. Disord. 29, 622–633 (2014).

Boersma, I. et al. Parkinson disease patients’ perspectives on palliative care needs: what are they telling us? Neurol. Clin. Pract. 6, 209–219 (2016).

Tuck, K. K., Brod, L., Nutt, J. & Fromme, E. K. Preferences of patients with Parkinson’s disease for communication about advanced care planning. Am. J. Hosp. Palliat. Care 32, 68–77 (2015).

Walter, H. A. W., Seeber, A. A., Willems, D. L. & de Visser, M. The role of palliative care in chronic progressive neurological diseases−a survey amongst neurologists in the Netherlands. Front. Neurol. 9, 1157 (2018).

Abu Snineh, M., Camicioli, R. & Miyasaki, J. M. Decisional capacity for advanced care directives in Parkinson’s disease with cognitive concerns. Parkinson's Relat. Disord. 39, 77–79 (2017).

Hall, K., Sumrall, M., Thelen, G. & Kluger, B. M. Palliative care for Parkinson’s disease: suggestions from a council of patient and carepartners. npj Parkinson's Dis. 3, 1–2 (2017).

Curtis, J. R., Patrick, D. L., Caldwell, E. S. & Collier, A. C. Why don’t patients and physicians talk about end-of-life care? Barriers to communication for patients with acquired immunodeficiency syndrome and their primary care clinicians. Arch. Intern. Med. 160, 1690–1696 (2000).

Krakauer, E. L., Crenner, C. & Fox, K. Barriers to optimum end-of-life care for minority patients. J. Am. Geriatr. Soc. 50, 182–190 (2002).

Lum, H. D. et al. Framing advance care planning in Parkinson disease. Neurology 10.1212/WNL.0000000000007552 (2019).

Shalowitz, D. I., Garrett-Mayer, E. & Wendler, D. The accuracy of surrogate decision makers. Arch. Intern. Med. 166, 493 (2006).

Tuck, K. K. et al. Life-sustaining treatment orders, location of death and co-morbid conditions in decedents with Parkinson’s disease. Parkinson's Relat. Disord. 21, 1205–1209 (2015).

Ernst, A., Allen, J., Dubourg, L. & Souchay, C. Present and future selves in Parkinson’s disease. Neurocase 23, 210–219 (2017).

Young, M. J. & Bursztajn, H. J. Narrative, identity and the therapeutic encounter. Ethics Med. Public Health 2, 523–534 (2016).

de Vito, S. et al. Future thinking in Parkinson’s disease: an executive function? Neuropsychologia 50, 1494–1501 (2012).

Mahajan, A., Patel, A., Nadkarni, G. & Sidiropoulos, C. Are hospitalized Parkinson’s disease patients more likely to carry a do-not-resuscitate order? J. Clin. Neurosci. 37, 57–58 (2017).

Li, W. et al. Treatment preferences at the end-of-life in Parkinson’s Disease patients. Mov. Disord. Clin. Pract. 3, 483–489 (2016).

Ubel, P. A., Schwarz, N., Loewenstein, G. & Smith, D. Misimagining the unimaginable: the disability paradox and health care decision making. Health Psychol. 24, 57–62 (2005).

Albrecht, G. L. & Devlieger, P. J. The disability paradox: high quality of life against all odds. Soc. Sci. Med. 48, 977–988 (1999).

Loewenstein, G. Projection bias in medical decision making. Med. Decis. Mak. 25, 96–105 (2005).

Menza, M. A., Sage, J., Marshall, E., Cody, R. & Duvoisin, R. Mood Changes and “On-Off” Phenomena in Parkinson’s Disease. Mov. Disord. 5(2), 148–151 (1990).

Lang, A. E. et al. Deep brain stimulation: preoperative issues. Mov. Disord. 21(S14), S171–S196 (2006).

Kraemer, F. Authenticity or autonomy? When deep brain stimulation causes a dilemma. J. Med. Ethics 39, 757–760 (2013).

Baertschi, M. et al. The impact of deep brain stimulation for Parkinson’s disease on couple satisfaction: an 18-month longitudinal study. J. Clin. Psychol. Med. Settings. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10880-019-09601-x (2019).

Shahmoon, S. & Jahanshahi, M. Optimizing psychosocial adjustment after deep brain stimulation of the subthalamic nucleus in Parkinson’s disease. Mov. Disord. 32, 1155–1158 (2017).

Schüpbach, M. et al. Neurosurgery in Parkinson Disease: A Distressed Mind in a Repaired Body? Neurology. 66(12), 1811–1816 (2006).

Agid, Y. et al. Neurosurgery in Parkinson’s disease: the doctor is happy, the patient less so? Parkinson’s Dis. Relat. Disord. 409–414 (Springer, 2006).

Rossi, M., Bruno, V., Arena, J., Cammarota, A. & Merello, M. Challenges in PD patient management after DBS: a pragmatic review. Mov. Disord. Clin. Pract. 5, 246–254 (2018).

Flores Alves Dos Santos, J. et al. Tackling psychosocial maladjustment in Parkinson’s disease patients following subthalamic deep-brain stimulation: a randomised clinical trial. PLoS ONE 12, e0174512 (2017).

Aslakson, R. A. et al. Promoting perioperative advance care planning: a systematic review of advance care planning decision aids. J. Comp. Eff. Res. 4, 615–650 (2015).

Stacey, D., Légaré, F. & Lewis, K. B. Patient decision aids to engage adults in treatment or screening decisions. J. Am. Med. Assoc. 318, 657–658 (2017).

Suhl, J. Myth of Substituted Judgment. Arch. Intern. Med. 154, 90 (1994).

Curtis, J. R. et al. Effect of a patient and clinician communication-priming intervention on patient-reported goals-of-care discussions between patients with serious illness and clinicians: a randomized clinical trial. JAMA Intern. Med. 178, 930–940 (2018).

Plonsky, O., Erev, I., Hazan, T. & Tennenholtz, M. Psychological forest: predicting human behavior. Ssrn 656–662. https://doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.2816450 (2016).

Levy, J., Markell, D. & Cerf, M. Polar Similars: using massive mobile dating data to predict dating preferences. Front. Psychol. 10, 2010 (2019).

Cerf, M., Greenleaf, E., Meyvis, T. & Morwitz, V. G. Using single-neuron recording in marketing: opportunities, challenges, and an application to fear enhancement in communications. J. Mark. Res. 52, 530–545 (2015).

Biller-Andorno, N. & Biller, A. Algorithm-aided prediction of patient preferences—an ethics sneak peek. N. Engl. J. Med. 381, 1480 (2019).

Acknowledgements

Dr. Sokol extends his gratitude toward Ms. Annie Wescott and Ms. Jonna Peterson for their assistance in identifying pertinent manuscripts, and toward Dr. Joel Frader, Dr. Joshua Hauser, and Dr. Kathy Neely for their willingness to meet, to educate, and to discuss. Mr. Paparian and Dr. Sokol extend their appreciation to Dr. Ori Plonsky for discussions related to the paper.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

L.L.S. conceived of the idea and wrote the first draft of the paper and revised subsequent drafts for intellectual content. M.J.Y., J.P., B.M.K., H.D.L., J.B., N.M.K., A.E.L., A.J.E., O.M.D., J.M.M., D.D.M., T.S. and M.C. contributed to conception, analysis, critical review, and revision of paper; approved the final draft for submission.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

Dr. Sokol serves as an ad hoc consultant for Tikvah for Parkinson. Dr. Young has nothing to disclose. Mr. Paparian is an employee of Verily Life Sciences, LLC. The opinions expressed herein are those of the author and do not reflect the opinions of Verily Life Sciences, LLC. Dr. Kluger has received support from NINDS, NIA, NINR, the Michael J. Fox Foundation, the Parkinson Foundation, PCORI, the Colorado Clinical and Translational Sciences Institute, and the Davis Phinney Foundation. Dr. Lum is supported in part by the National Institutes of Health (K76AG054782). Dr. Besbris is currently an American Academy of Hospice and Palliative Medicine (AAHPM) Neuropalliative SIG Co-Chair and the American Academy of Neurology Pain and Palliative Section Vice-Chair. Dr. Kramer is currently an American Academy of Hospice and Palliative Medicine (AAHPM) Neuropalliative SIG Co-Chair. Dr. Lang has received consulting fees from AbbVie, Acorda, Bristol-Myers Squibb, Biogen, Merck, Sun Pharma, Corticobasal Solutions, Sunovion, and Paladin, and honoraria from Medichem and Medtronic. Dr. Espay has received grant support from the National Institutes of Health (NIH), Great Lakes Neurotechnologies and the Michael J. Fox Foundation; personal compensation as a consultant/scientific advisory board member for Abbvie, Adamas, Acadia, Acorda, Neuroderm, Impax, Sunovion, Lundbeck, Osmotica Pharmaceutical, and USWorldMeds; publishing royalties from Lippincott Williams & Wilkins, Cambridge University Press, and Springer; and honoraria from USWorldMeds, Lundbeck, Acadia, Sunovion, the American Academy of Neurology, and the Movement Disorders Society. He serves as chair of the MDS Task Force on Technology. Dr. Dubaz has nothing to disclose. Dr. Miyasaki receives grants through PCORI and Parkinson Alberta and is a member of the American Academy of Neurology Board of Directors. Dr. Matlock was a Hartford Geriatrics Health Outcomes Research Scholar. In addition, Dr. Matlock was supported by a career development award from the NIA (1K23AG040696). Dr. Simuni has received personal compensation for consulting, serving on a scientific advisory board, speaking, or other activities with Acadia Abbvie Anavex Allergan Avid Civitas Accorda GE Medical Eli Lilly Cynapsus Ibsen IMPAX Merz Inc. National Parkinson Foundation Navidea Sanofi Pfizer Sunovion TEVA UCB Pharma Voyager US World Meds. Dr. Simuni has received research support from Civitas, Acorda, Biogen, Roche Neuroderm. Dr. Cerf has no relevant disclosures related to the paper.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons license and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Sokol, L.L., Young, M.J., Paparian, J. et al. Advance care planning in Parkinson’s disease: ethical challenges and future directions. npj Parkinsons Dis. 5, 24 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41531-019-0098-0

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41531-019-0098-0

This article is cited by

-

Characteristics, Complications, and Outcomes of Critical Illness in Patients with Parkinson Disease

Neurocritical Care (2025)

-

Far from being the end of the road: taking a closer look at neuropalliative care in Parkinson’s disease

Journal of Neural Transmission (2025)

-

Facilitators and barriers to the delivery of palliative care to patients with Parkinson’s disease: a qualitative study of the perceptions and experiences of stakeholders using the socio-ecological model

BMC Health Services Research (2023)

-

Health care experiences of people with Parkinson’s disease in Australia

BMC Geriatrics (2023)

-

The elephant in the room: critical reflections on mortality rates among individuals with Parkinson’s disease

npj Parkinson's Disease (2023)