Abstract

A new Parkinson’s disease (PD) subtyping model has been recently proposed based on the initial location of α-synuclein inclusions, which divides PD patients into the brain-first subtype and the body-first subtype. Premotor RBD has proven to be a predictive marker of the body-first subtype. We found compared to PD patients without possible RBD (PDpRBD–, representing the brain-first subtype), PD patients with possible premotor RBD (PDpRBD+, representing the body-first subtype) had lower Movement Disorders Society Unified Parkinson’s Disease Rating Scale part III (MDS UPDRS-III) score (p = 0.022) at baseline but presented a faster progression rate (p = 0.009) in MDS UPDRS-III score longitudinally. The above finding indicates the body-first subtype exhibited a faster disease progression in motor impairments compared to the brain-first subtype and further validates the proposed subtyping model.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Parkinson’s disease (PD) is a heterogeneous neurodegenerative disorder exhibiting a wide range of phenotypes1. This diversity has prompted the proposal of different PD subtypes, aiming to improve our understanding of the underlying disease mechanisms and provide personalized management. However, despite these efforts, a unified and widely accepted classification system for PD subtypes is still lacking, and the pathophysiological foundations of PD heterogeneity remain elusive.

To fully classify patients and account for the underlying pathophysiological changes, one intriguing hypothesis was recently proposed: the brain-first subtype and body-first subtype2. For the past two decades, the Braak’s staging system3 has been a dominant hypothesis, which postulated that α-synuclein, the key neuropathological feature of PD, originates in the dorsal motor nucleus of the vagus. However, robust evidence now indicates that the Braak staging system is not valid for all cases at post mortem and pathology might start in other brain regions in a subset of patients4,5,6.

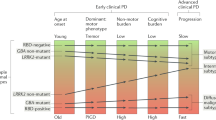

To address this controversy, the brain-first and body-first models were introduced. According to the theory, PD can be divided into two distinct subtypes based on the initial site of α-synuclein pathology and its spreading pattern7. In the brain-first subtype, α-synuclein pathology initially arises in the brain and subsequently spreads to the peripheral autonomic nervous system. Conversely, in the body-first subtype, the pathology originates in the enteric or peripheral autonomic nervous system and then spreads to the brain. Notably, the presence of rapid eye movement sleep behavior disorder (RBD) may be indicative of a body-first pattern7,8, as propagating body-first pathology will affect the pons before reaching the substantia nigra9.

Previous studies have verified the brain-first and body-first subtypes cross-sectionally, using both clinical multimodal imaging techniques7,8 and postmortem pathological findings4,5,6, which support the patient stratification based on the brain-first/body-first spreading hypothesis. However, to our knowledge, longitudinal study of the above subtypes is still lacking and little is known about the disease progression of the proposed brain-first and body-first subtypes. Therefore, we aimed to analyze the longitudinal changes of motor and non-motor features of the proposed brain-first and body-first subtypes, thus further validating the proposed subtyping model.

Results

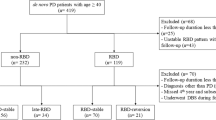

We enrolled a total of 137 PD patients in this study, 64 patients in the patients without possible RBD group (PDpRBD– group, baseline RBDSQ ≤ 3, baseline RBDSQ: 1.72 ± 0.93) and 73 patients in the patients with possible premotor RBD group (PDpRBD+ group, baseline RBDSQ ≥ 6, baseline RBDSQ: 8.45 ± 2.02) respectively. Sex distribution was statistically different between two groups (p = 0.007, Table 1). Compared to the PDpRBD– group, the PDpRBD+ group had lower Movement Disorders Society Unified Parkinson’s Disease Rating Scale part III (MDS UPDRS-III) score (p = 0.022) and higher Non-motor Symptoms Scale (NMSS) score (p = 0.001) at baseline (Table 1), indicating the body-first subtype presented fewer motor impairments but more nonmotor impairments compared to the brain-first subtype. No statistical differences were found in Epworth Sleepiness Scale (ESS) score, Mini Mental State Examination (MMSE) score, Beck Depression Inventory (BDI) score, Parkinson Disease Questionnaire 39 (PDQ-39) score and levodopa equivalent daily dose (LEDD) between two groups. Subscores of MDS UPDRS-III and NMSS by group are listed in the Supplementary Table 1.

Linear mixed models, adjusting for gender, age at baseline, and LEDD, were used to analyze the difference in the MDS UPDRS-III score, NMSS score, and ESS score between the PD pRBD– group and PDpRBD+ group. For MMSE score, BDI score, and PDQ-39 score, LEDD was further adjusted. We found the rate of change in MDS UPDRS-III score per month reached statistical significance between two groups (p = 0.009), with PDpRBD+ group, the body-first subtype, worsening at a statistically faster rate (PDpRBD+ group estimate β = 0.150 ± 0.019, PDpRBD- group estimate β = 0.071 ± 0.023) (Table 1, Fig. 1a). No statistical differences were found in disease progression rates regarding NMSS score (Table 1, Fig. 1b), ESS score (Table 1, Fig. 1c), MMSE score (Table 1, Fig. 1d), BDI score (Table 1, Fig. 1e) and PDQ-39 score (Table 1, Fig. 1f) between two groups.

Linear mixed models indicate that MDS UPDRS-III score trajectories over time are statistically different between two groups, with the PDpRBD+ group (red line, the body-first subtype), worsening at a faster rate than the PDRBD- group (blue line, the brain-first subtype) (a). No statistical differences were found in disease progression rates regarding NMSS score (b), ESS score (c), MMSE score (d), BDI score (e) and PDQ-39 score (f) between two groups. Abbreviations: PDpRBD–, PD patients without possible RBD; PDpRBD+, PD patients with possible premotor RBD. BDI Beck Depression Inventory; ESS Epworth Sleepiness Scale; LEDD levodopa equivalent daily dosage; MMSE Mini Mental State Examination; NMSS non-motor symptoms scale; PDQ-39 Parkinson Disease Questionnaire 39; MDS UPDRS-III Movement Disorders Society Unified Parkinson’s Disease Rating Scale part III.

Discussion

The above results revealed notable differences between the PDpRBD+ group and PDpRBD– group, suggesting body-first subtype exhibited fewer motor impairments (lower MDS UPDRS-III score) and more nonmotor impairments (higher NMSS score) compared to the brain-first subtype at baseline and a much faster disease progression in motor impairments, manifested by rapid increase in MDS UPDRS-III score.

Firstly, we have identified a notable sex distribution difference between two groups, as PDpRBD+ group presented a higher portion of male patients. The observed sex distribution discrepancy is consistent with previous findings, which found male were at higher risk of confirmed RBD in clinical populations than female10 and presented significantly more aggressive behavior during dreams11,12. This sex-based difference warrants further exploration in larger cohorts to ascertain its reproducibility and potential implications for clinical management.

Furthermore, our comparative analysis of motor impairments between the two groups has unveiled intriguing patterns. The PDpRBD+ group, representing the body-first subtype, exhibited lower MDS UPDRS-III score compared to the PDRBD- group, the brain-first subtype, at baseline. More importantly, the longitudinal assessment of disease progression revealed a statistically significant difference in the rate of change in MDS UPDRS-III score between two groups as PDpRBD+ group presented a much faster disease progression in motor impairments. The severity of impairments has long been linked to the pathological burden of α-synuclein13. In the body-first subtype, the pathology originates in the enteric or peripheral autonomic nervous system and then spreads to the brain. It has been suggested that α-synuclein may traverse multiple synapses to reach the substantia nigra, thereby causing motor impairments. In light of our baseline finding, we speculate that the body-first subtype may present fewer motor impairments in the initial stages due to less substantia nigra involvement. Borghammer13 has hypothesized that as the disease advances, the global burden of α-synuclein pathology is higher in the body-first subtype due to the more symmetric involvement of both hemispheres, possibly further promoted by the more marked involvement of ascending, neuromodulatory brainstem nuclei, leading to an elevated risk of faster progression. This hypothesis has not been validated in longitudinal cohort before, and our study here might provide a support for this concept, which needs further validation.

Additionally, we also found PDpRBD+ group exhibited higher NMSS score at baseline. This aligns with the notion that body-first patients should theoretically show damage to the autonomic nervous system and the lower brainstem structures earlier in the disease course compared to brain-first patients4 and is supported by the previous finding that body-first subtype is associated with non-motor dominant phenotype14. Therefore, our study adds to the prior body of evidence that the body-first subtype shows more severe non-motor impairments than the brain-first subtype.

Several limitations should be acknowledged. Firstly, the sample size in our exploratory study may limit the generalizability of the findings. Future research with larger cohorts is warranted to confirm and expand upon these results. Moreover, RBD was assessed by an accessible screening questionnaire RBDSQ. Though RBDSQ exhibits good diagnostic accuracy in the general population15 and we have classified patients using stringent thresholds, the inclusion criteria in this study was still not identical to the gold standard polysomnography. Additionally, the brain-first and body-first PD subtypes are most strongly distinguished early in the disease course and RBD disease state could have mitigated some difference between two groups. And recall bias may present due to long disease duration. Lastly, this study focused on a specific set of clinical features; further investigations incorporating imaging or biomarker data may provide a more comprehensive understanding of the underlying mechanisms driving subtype-specific progression.

In conclusion, our preliminary exploratory study contributes to the growing body of literature of the proposed brain-first and body-first subtypes and explores the longitudinal disease progression by subtypes. We have found that compared to the brain-first subtype, the body-first subtype exhibited a much faster disease progression in motor impairments, manifested by rapid increase in MDS UPDRS-III score. Future research should further validate the proposed subtyping model and delve deeper into the neurobiological underpinnings of these subtypes to inform targeted interventions and enhance the precision of PD management.

Methods

Patients and grouping

PD patients were enrolled from the Department of Neurology, Huashan Hospital, Fudan University. PD diagnosis for each patient was determined by three movement disorder specialists according to the UK PD Society Brain Bank Clinical Diagnostic Criteria16 (for patients recruited before 2016) and the 2015 MDS Clinical Diagnostic Criteria for PD17 (for patients recruited from 2016 on). The Human Studies Institutional Review Board, Huashan Hospital, Fudan University approved this study. Informed consents were obtained.

Despite polysomnography (PSG) is widely recognized as the gold standard for diagnosing RBD18, REM Sleep Behavior Disorder Screening Questionnaire (RBDSQ) was used due to the limited availability of polysomnography data, which exhibits good diagnostic accuracy in the general population15. To avoid the uncertainty caused by scores, we include classified patients without possible RBD (PDpRBD– group) as scoring ≤3 and patients with possible premotor RBD (PDpRBD+ group) as scoring ≥6 at baseline, same as one previous study defined8. 28 PD patients, who scored 4 or 5 on RBDSQ at baseline, were excluded. Their demographic profiles, baseline clinical characteristics, and disease progression rates were listed in the Supplementary Table 2 and Supplementary Table 3. For PDpRBD+ patients, subjective RBD sleep symptoms needed to manifest before the onset of motor symptoms. Thus, according to the above inclusion criteria, a total of 137 PD patients were enrolled in this study, 64 patients in PDpRBD– group and 73 patients in PDpRBD+ group respectively. The average follow-up time were 65.84 ± 32.55 months (maximum follow-up time: 124 months) in the PDpRBD– group and 60.75 ± 32.65 (maximum follow-up time: 133 months) in the PDpRBD+ group.

Clinical assessments

The standardized procedure detailed here was performed through a face-to-face interview with all PD patients. An established method was used to calculate the levodopa equivalent daily dose (LEDD)19. The Movement Disorders Society Unified Parkinson’s Disease Rating Scale part III (MDS UPDRS-III) were conducted during the off-medication state, defined as the withdrawal of anti-PD medications for at least 12 h, except in those who could not tolerate it. Non-motor Symptoms Scale (NMSS), Epworth Sleepiness Scale (ESS), Mini Mental State Examination (MMSE), Beck Depression Inventory (BDI), and Parkinson Disease Questionnaire 39 (PDQ-39) were also conducted. All patients were scheduled for an annual follow-up clinical assessment in the same month (±2 weeks) as in the previous year in our institution, if they were available.

Statistical analysis

To compare the baseline demographic profiles and clinical characteristics between the two groups, Chi-squared test was used for categorical variables and student t test and Mann–Whitney U test were used for continuous variables as appropriate. To compare the longitudinal changes in clinical characteristics between the two groups, a linear mixed-effect model was applied. Disease duration was used as the time scale. A participant-specific random effect was considered due to the correlations among repeated measurements within the same participants. For MDS UPDRS-III score, NMSS score, and ESS score, the analyses were corrected for gender, age at baseline and LEDD; while for MMSE score, BDI score, and PDQ-39 score, gender, age at baseline, LEDD, and years of education were corrected. Two-tailed p values are presented, and differences were considered statistically significant at p < 0.05.

Data availability

Due to privacy concerns, the original data (demographic information, questionnaires) cannot be publicly disclosed. However, the cleaned clinical data are available from the corresponding author (Y.T., J.W.) via mail.

References

Rodriguez-Sanchez, F. et al. Identifying Parkinson’s disease subtypes with motor and non-motor symptoms via model-based multi-partition clustering. Sci. Rep. 11, 1–10 (2021).

Borghammer, P. & Van Den Berge, N. Brain-first versus gut-first Parkinson’s Disease: a hypothesis. J. Parkinsons Dis. 9, S281–S295 (2019).

Braak, H. et al. Staging of brain pathology related to sporadic Parkinson’s disease. Neurobiol. Aging 24, 197–211 (2003).

Horsager, J., Knudsen, K. & Sommerauer, M. Clinical and imaging evidence of brain-first and body-first Parkinson’s disease. Neurobiol. Dis. 164, 105626 (2022).

Borghammer, P. et al. Neuropathological evidence of body-first vs. brain-first Lewy body disease. Neurobiol. Dis. 161, 105557 (2021).

Borghammer, P. et al. A postmortem study suggests a revision of the dual-hit hypothesis of Parkinson’s disease. npj Parkinsons Dis. 8, 1–11 (2022).

Horsager, J. et al. Brain-first versus body-first Parkinson’s disease: a multimodal imaging case-control study. Brain 143, 3077–3088 (2020).

Banwinkler, M., Dzialas, V., Hoenig, M. C. & van Eimeren, T. Gray matter volume loss in proposed brain-first and body-first Parkinson’s Disease subtypes. Mov. Disord. 37, 2066–2074 (2022).

McKenna, D. & Peever, J. Degeneration of rapid eye movement sleep circuitry underlies rapid eye movement sleep behavior disorder. Mov. Disord. 32, 636–644 (2017).

Li, X. et al. Sex differences in rapid eye movement sleep behavior disorder: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Sleep. Med. Rev. 71, 101810 (2023).

Cerri, S., Mus, L. & Blandini, F. Parkinson’s Disease in Women and Men: what’s the difference? J. Parkinsons Dis. 9, 501–515 (2019).

Bjørnarå, K. A., Dietrichs, E. & Toft, M. REM sleep behavior disorder in Parkinson’s disease–is there a gender difference? Parkinsonism Relat. Disord. 19, 120–122 (2013).

Borghammer, P. The α-Synuclein Origin and Connectome Model (SOC Model) of Parkinson’s disease: explaining motor asymmetry, non-motor phenotypes, and cognitive decline. J. Parkinsons Dis. 11, 455–474 (2021).

Pavelka, L. et al. Body-first subtype of Parkinson’s disease with probable REM-Sleep behavior disorder is associated with non-motor dominant phenotype. J. Parkinsons Dis. 12, 2561–2573 (2022).

Li, K., Li, S.-H., Su, W. & Chen, H.-B. Diagnostic accuracy of REM sleep behaviour disorder screening questionnaire: a meta-analysis. Neurol. Sci. 38, 1039–1046 (2017).

Hughes, A. J., Daniel, S. E., Kilford, L. & Lees, A. J. Accuracy of clinical diagnosis of idiopathic Parkinson’s disease: a clinico-pathological study of 100 cases. J. Neurol. Neurosurg. Psychiatry 55, 181–184 (1992).

Postuma, R. B. et al. MDS clinical diagnostic criteria for Parkinson’s disease. Mov. Disord. 30, 1591–1601 (2015).

Antelmi, E., Lippolis, M., Biscarini, F., Tinazzi, M. & Plazzi, G. REM sleep behavior disorder: Mimics and variants. Sleep. Med. Rev. 60, 101515 (2021).

Tomlinson, C. L. et al. Systematic review of levodopa dose equivalency reporting in Parkinson’s disease. Mov. Disord. 25, 2649–2653 (2010).

Acknowledgements

Y.T. received research funding from National Nature Science Foundation of China (82371261). J.W. received research funding from National Nature Science Foundation of China (91949118, 82171421, 92249302). National Health Commission of China (Pro20211231084249000238), and Shanghai Municipal Science and Technology Major Project (21S31902200).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Design and conceptualization of the study: J.W., Y.T. Data collection: Z.X., T.H., C.X., S.L., Y.S., F.L., J.W., Y.T. Statistical analysis of data: Z.X., T.H., C.X., X.L. Drafted and revising the manuscript for intellectual content: Z.X., T.H., C.X., J.W., Y.T.. Z.X., T.H. and C.X. are considered co-first author.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Xu, Z., Hu, T., Xu, C. et al. Disease progression in proposed brain-first and body-first Parkinson’s disease subtypes. npj Parkinsons Dis. 10, 111 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41531-024-00730-1

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41531-024-00730-1

This article is cited by

-

Synuclein Proteoforms: Role in Health and Disease

Molecular Neurobiology (2026)

-

Unveiling Butyrate as a Parkinson’s Disease Therapy

Neuroscience Bulletin (2026)

-

Multimodal diagnostic tools and advanced data models for detection of prodromal Parkinson’s disease: a scoping review

BMC Medical Imaging (2025)

-

Clinical progression and genetic pathways in body-first and brain-first Parkinson’s disease

Molecular Neurodegeneration (2025)

-

Parkinson’s disease with possible REM sleep behavior disorder correlated with more severe glymphatic system dysfunction

npj Parkinson's Disease (2025)