Abstract

The recently proposed body-first and brain-first subtypes are classified based on the initial localization of α-synuclein inclusions. This study investigated plasma biomarkers and cerebral glucose metabolism characteristics in putative brain-first and body-first subtypes in PD subjects. PD patients without possible RBD (PDpRBD–) (n = 58) and with possible RBD symptoms discovered before motor symptoms (PDpRBD+) (n = 43) were recruited. Single-molecule array (SimoA) was used for measuring plasma biomarkers, including glial fibrillary acidic protein (GFAP), neurofilament light chain (NfL), Tau and phosphorylated-tau 181 (pTau-181). All participants underwent 18F-fluorodeoxyglucose (FDG) PET scans. Compared to PDpRBD– patients, PDpRBD+ patients exhibited significantly increased plasma GFAP levels and reduced 18F-FDG uptake in cortical regions. Notably, plasma GFAP and NfL levels correlated with cerebral glucose metabolism in PDpRBD– patients. Our study identified the association between plasma GFAP and NfL levels and cerebral glucose metabolism in PDpRBD– patients. Further large-scale longitudinal studies are required.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

A longstanding issue in Parkinson’s disease (PD) is its diverse phenotypic characteristics, posing challenges for both clinicians and researchers. Numerous efforts have been made to classify PD patients into subtypes in order to uncover underlying patterns which explain this heterogeneity. Interestingly, a recent hypothesis has introduced two distinct subtypes of α-synuclein spreading based on the initial location of α-synuclein inclusions: the putative brain-first subtype, in which α-synuclein pathology originates in the brain and spreads to the peripheral autonomic nervous system, and the putative body-first subtype, where pathology initiates in the enteric or peripheral autonomic nervous system and progresses to the brain1. REM sleep behavior disorder (RBD) has been suggested as a key discriminator, differentiating the putative body-first (RBD-positive at motor symptom onset) subtype from the putative brain-first (RBD-negative at motor symptom onset) subtype of PD. Previous studies suggested that the body-first PD patients exhibit greater autonomic symptoms, faster motor and non-motor progressions, and more symmetric striatal dopaminergic loss and motor symptoms2,3.

In recent years, research on biofluid biomarkers in Parkinson’s disease has expanded significantly. Emerging evidence highlights the diagnostic and prognostic potential of other cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) and blood biomarkers associated with PD pathophysiology beyond α-synuclein, including glial fibrillary acidic protein (GFAP), neurofilament light chain (NfL), Tau, and phosphorylated-tau 181 (pTau-181)4,5. However, these biomarkers have not been investigated in body-first and brain-first subtypes for PD subjects.

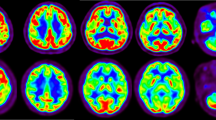

Positron emission tomography (PET) imaging is a valuable tool for assessing brain metabolic alterations in PD. PD is associated with an abnormal pattern of relative cortical hypometabolism and subcortical hypermetabolism6. Two previous studies have indicated that cortical metabolism in idiopathic RBD (iRBD) patients is less affected compared to early-stage PD patients, and significantly less than advanced-stage PD patients7,8. Until now, the metabolic differences between the two subtypes remain unexplored.

Therefore, we first examined plasma biomarkers in putative brain-first and body-first subtypes in PD patients. We then used 18F-fluorodeoxyglucose (FDG) PET to characterize metabolic differences between the two subtypes. Finally, we analyzed the possible correlations between these plasma biomarkers and cerebral metabolism in the putative brain-first and body-first groups separately.

Results

Demographics and clinical characteristics

Demographic information for the study participants is presented in Table 1. No significant differences were observed between the PDpRBD− and the PDpRBD+ group in age, sex, education, disease severity (including disease duration, H&Y stage and MDS UPDRS-III score), LED or BDI score. The PDpRBD+ group showed worse performance in NMSS score (P = 0.022), NMSS_AD score (P = 0.023) and PDQ-39 score (P = 0.028) compared with the PDpRBD− group. As expected, the PDpRBD+ group showed a significantly higher RBD score compared with the PDpRBD− group (P < 0.001). No significant differences were found in MMSE (P = 0.228), MoCA (P = 0.915), and the neuropsychological tests of cognition domains (Supplementary Tables 1 and 2).

RBD-related items were calculated instead of the total sum score of the questionnaire and were described as the PDspRBD+ group (n = 32). Comparison among PDspRBD+ patients, PD pRBD− patients and HCs was estimated in Supplementary Table 3. PDspRBD+ patients exhibited significantly worse performance in the NMSS score (P = 0.047), NMSS_AD score (P = 0.015) and PDQ-39 score (P = 0.028) compared with the PDpRBD− group, following a similar trend as observed in the PDpRBD+ group.

Comparisons of plasma biomarker levels among groups

Plasma biomarker levels of PDpRBD+ and PDpRBD− group were presented in Table 1 and Fig. 1. Plasma GFAP levels were significantly increased in the PDpRBD+ group compared with both the HCs (P < 0.001) and PDpRBD− (P < 0.001) groups. Additionally, plasma GFAP was significantly elevated in the PDpRBD− group compared with the HCs (P = 0.032). Plasma NfL was significantly elevated in the PDpRBD+ group compared with the HCs. (P < 0.001) and PDRBD− (P = 0.042) groups. Furthermore, plasma NfL was significantly increased in the PDRBD− group compared to the HCs (P < 0.001). In PDspRBD+ group, plasma GFAP and plasma NfL showed the same trend as the PDpRBD+ group (GFAP: P < 0.001 to HCs, P = 0.001 to PDpRBD−; NfL: P < 0.001 to HCs, P = 0.039 to PDpRBD−). For plasma Tau and pTau-181 levels, no differences were found among HC and PD patients, as well as the two PD groups (P = 0.891, P = 0.503).

Plasma GFAP levels in PD without possible RBD (PDpRBD–) and with possible RBD (PDpRBD+) and healthy controls (HCs). Groups were compared with a one-way analysis of covariance (ANCOVA), including age as a covariate. Boxes show the median and IQR, and whiskers are minimum and maximum. Dots are single values. *p < 0.05, ***p < 0.001.

Comparisons of cerebral glucose metabolism between HCs, PDpRBD −, and PDpRBD+ patients

PDpRBD− showed a decreased 18F-FDG uptake in the left inferior parietal gyrus, left middle occipital gyrus, left superior occipital gyrus and an increased uptake in cerebellum, right paracentral lobule and precentral gyrus compared with HCs. PDpRBD+ showed a decreased 18F-FDG uptake in left middle temporal gyrus, middle frontal gyrus, left middle frontal gyrus, and left middle occipital gyrus and an increase in cerebellum, paracentral lobule, putamen and thalamus to HCs (Supplementary Fig. 1; Supplementary Tables 4 and 5). Compared to the PDpRBD− group, the PDpRBD+ group showed a decreased 18F-FDG uptake in the left middle temporal gyrus, bilateral middle occipital gyrus, and left inferior parietal gyrus (P < 0.001, uncorrected) (Fig. 2; Table 2). No significant increase was observed.

Correlations between plasma biomarkers and cerebral glucose metabolism

As presented above, plasma GFAP and NfL showed significant differences among between PDpRBD− and PDpRBD+ group. We further explore associations between plasma GFAP and NfL levels and cerebral glucose metabolism. Voxel-based multiple regression was conducted between plasma GFAP and NfL levels and cerebral glucose metabolism in PDpRBD− and PDpRBD+ group separately.

Among PDpRBD− group, plasma GFAP levels significantly correlated with increased 18F-FDG uptake in the bilateral substantia nigra and right cerebellum, and negatively correlated with 18F-FDG uptake in left inferior and superior parietal gyrus. However, no association was found in the PDpRBD+ group (Fig. 3).

Up correlations between the plasma GFAP levels and 18F-FDG uptake in PDpRBD− patients. Down: correlations between the plasma GFAP levels and 18F-FDG uptake in PDpRBD+ patients. Positive correlations are displayed using a red–yellow scale and negative correlations using a blue–green scale. The thresholds of the color bars represent T values. Voxel threshold was set at P < 0.001, uncorrected.

For PDpRBD− group, plasma NfL levels showed a positive correlation with 18F-FDG uptake in the bilateral cerebellum, and a negative correlation with 18F-FDG uptake in the bilateral superior frontal gyrus, thalamus, anterior cingulate gyrus, and cuneus. For PDpRBD+ group, there is no correlation with 18F-FDG uptake in any brain region (Fig. 4). Detailed results of the correlation between plasma GFAP, plasma NfL levels, and 18F-FDG uptake in the PDpRBD− group are summarized in Tables 3 and 4.

Up: correlations between the plasma NfL levels and 18F-FDG uptake in PDpRBD− patients. Down: correlations between the plasma NfL levels and 18F-FDG uptake in PDpRBD+ patients. Positive correlations are displayed using a red–yellow scale and negative correlations using a blue–green scale. The thresholds of the color bars represent T values. The voxel threshold was set at P < 0.001, uncorrected.

Discussion

The study indicated that PDpRBD+ patients demonstrated elevated plasma levels of GFAP and NfL compared to PDpRBD− patients. Additionally, we identified hypometabolism in PDpRBD+ patients compared with PDpRBD− patients, predominantly in the temporal and occipital regions. Notably, our findings revealed that plasma GFAP and NfL levels were correlated with cerebral glucose metabolism in PDpRBD− patients but showed no association with cerebral glucose metabolism in PDpRBD+ patients.

The brain-first and body-first theory differentiated the two PD subtypes based on the initial site of α-synuclein pathology site and its transmission pattern. RBD before motor symptoms has been proposed as a key marker of the hypothesized body-first subtype. Our study demonstrated that the PDpRBD+ group, which represented the putative body-first subtype according to the theory, showed worse performance in non-motor symptoms, especially in the autonomic dysfunction symptoms. The result consisted with the previous studies which suggested more severe damage in the putative body-first subtype at baseline in the autonomic nervous system1,2,9.

To the best of our knowledge, it is the first study to investigate the difference in cerebral glucose metabolism changes between PD/RBD+ and PD/RBD− patients. Our results demonstrated a more pronounced decrease in cortical metabolism in the putative body-first PD (PD/RBD+) than in putative brain-first PD (PD/RBD−) patients. Hypometabolism in the parietal and temporal cortices has been consistently correlated with executive dysfunction. Visuospatial dysfunction could be correlated with the occipito-parietal and temporal hypometabolic changes. However, our study did not find significant differences in MMSE or in MoCA scales, nor in specific cognitive domains, suggesting that the baseline cognition status showed little influence on the decreased metabolism of the PDpRBD+ group. Previous studies also suggested relative hypometabolism predominantly in the parieto-occipital cortex bilaterally in PD patients with autonomic failure, but the relation of autonomic system and the glucose metabolism difference remained to be explored10. The brain-first/body-first hypothesis is based on distinct α-synuclein spreading patterns. Previous studies showed a higher severity of α-synuclein pathology in the brain of RBD-positive PD patients11. It is possible that the cortical hypometabolism observed in putative body-first PD may be partially attributed to more widespread α-synuclein pathology. Although the underlying pathomechanisms for the expression of the metabolic pattern remained unclear, the studies suggest significant cortical metabolic alterations between putative brain-first and putative body-first PD subtypes.

GFAP is a key structural component of fibrillary astrocytes and is widely recognized as a prominent marker of reactive astrocytosis12. In our study, we observed elevated levels of plasma GFAP in individuals with both putative body-first and brain-first PD. Notably, the increase in plasma GFAP was more pronounced in putative body-first PD than in putative brain-first PD. This might indicate the presence of reactive astrogliosis in PD, and more pronounced reactive astrogliosis in putative body-first PD. Interestingly, in putative brain-first PD, plasma GFAP levels were negatively associated with 18F-FDG uptake in the parietal areas, while a positive association was primarily found in the midbrain. Under physiological conditions, astrocytes play a significant role in facilitating 18F-FDG uptake through astroglial glutamate transport activation13. However, in pathological conditions, reactive astrocytes, characterized by elevated GFAP expression, exhibit consistently reduced expression of genes involved in glutamate/GABA homeostasis, leading to hypometabolism14. Therefore, it is plausible that reactive astrocytes might contribute to the hypermetabolism and hypometabolism observed in putative brain-first PD, though further evidence is required.

In addition to GFAP, plasma NfL levels also showed significantly elevation in putative body-first PD compared with putative brain-first PD. As a highly expressed protein in large caliber myelinated axons, NfL has been recently proposed as marker of neuronal damage in various neurological disorders15. Evidence suggests that increased NfL levels in PD are associated with greater disease severity, faster motor progression, and a higher risk of dementia16,17. Prior research has shown that putative body-first PD patients experience more autonomic symptoms, along with faster motor and non-motor progression2,3. Further investigation is needed to determine whether higher baseline plasma NfL values in these patients predict faster motor and non-motor progression. Notably, a correlation between plasma NfL and glucose metabolism has also been observed in putative brain-first PD patients. Since NfL is considered as a nonspecific marker of neurodegeneration, the observed relationship with 18F-FDG uptake may reflect ongoing neurodegeneration processes. A longitudinal study is needed to better understand the relationship between plasma NfL changes and alterations in cerebral metabolism.

To our surprise, we observed a correlation between plasma GFAP and NfL levels and cerebral glucose metabolism in putative brain-first PD patients, while no significant correlation was found in putative body-first PD patients. GFAP is not only highly expressed in the central nervous system (CNS) but also present in the peripheral nervous system (PNS) and the glial cells of the enteric nervous system (ENS)18. NfL has been found to increase in both CNS and PNS diseases associated with axonal injury or degeneration19. In the subtype where α-synuclein pathology initially occurred in the enteric or peripheral autonomic nervous system, we did not observe a direct correlation between plasma GFAP and NfL levels and cerebral metabolism. This lack of correlation may be attributed to the earlier and more pronounced involvement of the enteric or peripheral autonomic nervous system in the putative body-first subtype, given that GFAP and NfL are not exclusive to the CNS.

The current data on PDpRBD− patients were consistent with the putative brain-first subtype (PD/RBD−) in our study. However, we hypothesized that a fraction of our PDpRBD− patients would develop RBD in the future, and such future RBD converters would align with the top-down RBD category. Therefore, further longitudinal follow-up is necessary to differentiate PDpRBD− patients with or without developed RBD.

Identifying clinical subtypes of Parkinson’s disease is crucial for better understanding its pathogenesis, predicting disease progression, and developing potential targeted therapeutic interventions. In our study, the PDpRBD+ group exhibited lower cortical FDG metabolism and higher levels of GFAP and other inflammatory markers. Our previous research demonstrated that the putative body-first subtype exhibited faster disease progression in motor impairments20. Another research also suggested that a body-first subtype of α-synucleinopathy is characterized by diffuse motor and non-motor symptoms, combined with a more aggressive disease course21. Based on the previous researches, we hypothesize that the body-first subtype might represent the subtype of PD associated with more rapid clinical progression. Nevertheless, further longitudinal studies comparing disease progression across different subtypes are required to validate this classification and its implications for disease progression.

This study has several limitations. Firstly, the assessment of RBD relied on a screening questionnaire rather than the gold standard polysomnography (PSG). Although more conservative cutoff values were applied to improve sensitivity and specificity22,23, this approach still introduces a degree of uncertainty. Secondly, the FDG results may be influenced by certain analysis, which could lead to potential discrepancies in the final outcomes. Finally, our exploration of research questions was conducted through a cross-sectional analysis, and the study included a limited number of participants. Further large-scale studies on longitudinal data are warranted.

In summary, our study revealed cortical metabolic differences between the putative brain-first and putative body-first subtypes in PD. Specifically, we identified associations between plasma GFAP and NfL levels and cerebral glucose metabolism in putative brain-first PD patients. Our findings support the notion that putative brain-first and putative body-first PD might be two distinguishable entities on plasma and imaging markers. Difference in the spreading patterns of putative brain-first and putative body-first PD provide valuable insights into the heterogeneity of PD and need further investigation.

Methods

Participants

Participants for the study were recruited from the Movement Disorders Clinics at Huashan Hospital, Fudan University from February 2012 to January 2022. The study cohort included 101 PD patients and 15 healthy controls (HCs) (Fig. 5). PD patients were diagnosed based on the UK Brain Bank criteria24. The diagnosis of PD was further confirmed by using dopaminergic PET imaging and 18F-FDG PET imaging (Fig. 6). All HCs were acknowledged to have no history of neurological or psychiatric conditions.

We employed the REM sleep behavior disorder screening questionnaire (RBDSQ) to classify possible RBD in PD patients25. The Chinese version of RBDSQ was used in the study22. Despite polysomnography (PSG) being widely recognized as the gold standard for diagnosing RBD26, RBDSQ was used due to the limited availability of polysomnography data. As described in the previous study27, we excluded subjects with scores of 4 and 5 from the analysis to minimize ambiguity near the original cutoff score of 5 points, leaving only scores ≤3 to be categorized as no possible RBD (RBD−) and scores ≥6 as having possible RBD performance (RBD+) (Fig. 6). For possible RBD+ patients, subjective RBD sleep symptoms needed to manifest before the onset of motor symptoms. Finally, PD patients without possible RBD (PDpRBD–) (n = 58) and PD patients with possible RBD occurred before motor symptoms (PDpRBD+) (n = 43) were enrolled. Specific RBD-related questionnaire items were used to further improve the specificity of possible RBD patients and finally enrolled 32 screened PDpRBD+ (PDspRBD+) patients after exclusion28.

The study was performed under the principles of the Declaration of Helsinki. Ethical approval was granted by the Institutional Review Board at the Huashan Hospital (approval numbers: 2011-174-2). All participants were provided with written informed consent.

Clinical and neuropsychological assessments

Patients underwent clinical evaluation after being off anti-parkinsonian medications for a minimum of 12 hours. The severity of the disease was assessed using the MDS UPDRS-III and the Hoehn and Yahr (H&Y) scale29,30. Depression levels were measured using the Beck Depression Inventory (BDI)31,32. Non-motor symptoms were evaluated using The Non-Motor Symptoms Scale (NMSS) and items related to the autonomic nervous system were calculated as the NMSS_AD score33,34. Olfactory function was assessed using the Sniffin’ Sticks test35. Quality of life was assessed using the 39-item Parkinson’s Disease Questionnaire (PDQ-39)36,37. The Chinese versions were used in the study and have been all proven to be a valid and reliable method for valuation. The total daily dosage of anti-parkinsonian medications was converted into a Levodopa equivalent dose (LED)38.

Cognitive assessment was conducted while patients were on their regular anti-parkinsonian medications state (ON state). Global cognitive functioning was measured using the Mini-Mental State Examination (MMSE) and the Montreal Cognitive Assessment (MoCA)39,40,41.

Measurement of GFAP, NfL, Tau, and pTau-181 in plasma

Blood samples were collected in the morning using EDTA Vacutainer tubes (BD) after a 12 hour overnight fast. The EDTA blood was temporarily kept on ice and then centrifuged at 2000 × g for 15 minutes within 30 minutes after collection. The plasma supernatant was collected, divided into 200 µl/tube aliquot, and frozen at −80 °C until further analysis.

Plasma levels of GFAP, NfL, Tau, and pTau-181 were quantified by the Quanterix SimoA HD-X analyzer, using the SimoA Neurology 4-Plex B Kit and the SimoA pTau-181 V2 Advantage Kit following the manufacturer’s instructions. Samples were randomized, blinded, and measured using a single batch of reagents from the same lot. All assays demonstrated good analytical performance. The within-run variations and between-run variations both ranged consistently below 15%.

PET imaging

All participants were instructed to rest adequately and fast for at least 6 hours, with patients refraining from anti-parkinsonian medications for 12 hours before the PET scan. A low-dose CT transmission scan was conducted for attenuation correction. A 10-minute PET scanning was then performed 60 min following the intravenous injection of 18F-FDG (150–200 MBq). Participants were placed in a quiet and dimly lit environment with minimal background noise. The 18F-FDG PET imaging data was acquired on Siemens Biograph 64 PET/CT (Siemens, Munich, Germany) in 3D mode. Image reconstruction was achieved by the ordered subset expectation maximization 3D (OSEM 3D) method.

Imaging preprocessing and data analysis

Data preprocessing and analysis were performed using SPM12 software (Wellcome Department of Imaging Neuroscience, Institute of Neurology, London, UK) on MATLAB R2018b (MathWorks Inc., Sherborn, MA, USA). PET scans were initially spatially normalized into the Montreal Neurological Institute (MNI) brain space using both linear and non-linear 3D transformations. Spatially normalized PET images were then smoothed using a Gaussian kernel of 10 mm full-width at half-maximum.

After imaging preprocessing, differences in relative cerebral metabolism or FDG uptake between PDpRBD– and PDpRBD+ patients were analyzed by a two-sample t test according to the general linear model. Multiple regression analyses were conducted to explore the correlations between plasma biomarkers and global glucose metabolism. For estimating global effects, we use mean voxel value for global calculation. P < 0.001 (uncorrected) was set as the voxel threshold over the whole brain to compare significant difference and correlation evaluation.

Statistical analysis

We use χ2 for categorical data, one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) with Bonferroni’s corrected post hoc comparisons for parametric data, and Kruskal–Wallis test with Dunn’s corrected post hoc comparisons for non-parametric data to compare among groups as appropriate. Differences in continuous variables between PDpRBD– and PDpRBD+ patients were analyzed with the Mann-Whitney U test. All analyses were conducted using SPSS (version 20.0; IBM, Armonk, NY, USA). Two-tailed P values < 0.05 were considered statistically significant.

Data availability

The datasets generated during and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

References

Horsager, J. et al. Brain-first versus body-first Parkinson’s disease: a multimodal imaging case-control study. Brain 143, 3077–3088 (2020).

Horsager, J., Knudsen, K. & Sommerauer, M. Clinical and imaging evidence of brain-first and body-first Parkinson’s disease. Neurobiol. Dis. 164, 105626 (2022).

Borghammer, P. The alpha-synuclein origin and connectome model (soc model) of Parkinson’s disease: explaining motor asymmetry, non-motor phenotypes, and cognitive decline. J. Parkinsons Dis. 11, 455–474 (2021).

Schulz, I. et al. Systematic assessment of 10 biomarker candidates focusing on alpha-synuclein-related disorders. Mov. Disord. 36, 2874–2887 (2021).

Parnetti, L. et al. CSF and blood biomarkers for Parkinson’s disease. Lancet Neurol. 18, 573–586 (2019).

Ma, Y., Tang, C., Spetsieris, P. G., Dhawan, V. & Eidelberg, D. Abnormal metabolic network activity in Parkinson’s disease: test-retest reproducibility. J. Cereb. Blood Flow. Metab. 27, 597–605 (2007).

Meles, S. K. et al. FDG PET, dopamine transporter SPECT, and olfaction: combining biomarkers in REM sleep behavior disorder. Mov. Disord. 32, 1482–1486 (2017).

Huang, Z. et al. Correlations between dopaminergic dysfunction and abnormal metabolic network activity in REM sleep behavior disorder. J. Cereb. Blood Flow. Metab. 40, 552–562 (2020).

Pavelka, L. et al. Body-first subtype of Parkinson’s disease with probable REM-Sleep behavior disorder is associated with non-motor dominant phenotype. J. Parkinsons Dis. 12, 2561–2573 (2022).

Arahata, Y. et al. Parieto-occipital glucose hypometabolism in Parkinson’s disease with autonomic failure. J. Neurol. Sci. 163, 119–126 (1999).

Postuma, R. B. et al. REM sleep behavior disorder and neuropathology in Parkinson’s disease. Mov. Disord. 30, 1413–1417 (2015).

Liddelow, S. A. & Barres, B. A. Reactive astrocytes: production, function, and therapeutic potential. Immunity 46, 957–967 (2017).

Zimmer, E. R. et al. [(18)F]FDG PET signal is driven by astroglial glutamate transport. Nat. Neurosci. 20, 393–395 (2017).

Leng, K. et al. Molecular characterization of selectively vulnerable neurons in Alzheimer’s disease. Nat. Neurosci. 24, 276–287 (2021).

Gaetani, L. et al. Neurofilament light chain as a biomarker in neurological disorders. J. Neurol. Neurosurg. Psychiatry 90, 870–881 (2019).

Pilotto, A. et al. Plasma NfL, clinical subtypes and motor progression in Parkinson’s disease. Parkinsonism Relat. Disord. 87, 41–47 (2021).

Aamodt, W. W. et al. Neurofilament light chain as a biomarker for cognitive decline in Parkinson disease. Mov. Disord. 36, 2945–2950 (2021).

Yang, Z. & Wang, K. K. Glial fibrillary acidic protein: from intermediate filament assembly and gliosis to neurobiomarker. Trends Neurosci. 38, 364–374 (2015).

Olsson, B. et al. Association of cerebrospinal fluid neurofilament light protein levels with cognition in patients with dementia, motor neuron disease, and movement disorders. JAMA Neurol. 76, 318–325 (2019).

Xu, Z. et al. Disease progression in proposed brain-first and body-first Parkinson’s disease subtypes. NPJ Parkinsons Dis. 10, 111 (2024).

Johansson, M. E., van Lier, N. M., Kessels, R. P. C., Bloem, B. R. & Helmich, R. C. Two-year clinical progression in focal and diffuse subtypes of Parkinson’s disease. NPJ Parkinsons Dis. 9, 29 (2023).

Wang, Y. et al. Validation of the rapid eye movement sleep behavior disorder screening questionnaire in China. J. Clin. Neurosci. 22, 1420–1424 (2015).

Li, K., Li, S. H., Su, W. & Chen, H. B. Diagnostic accuracy of REM sleep behaviour disorder screening questionnaire: a meta-analysis. Neurol. Sci. 38, 1039–1046.38 (2017).

Hughes, A. J., Daniel, S. E., Kilford, L. & Lees, A. J. Accuracy of clinical diagnosis of idiopathic Parkinson’s disease: a clinico-pathological study of 100 cases. J. Neurol. Neurosurg. Psychiatry 55, 181–184 (1992).

Stiasny-Kolster, K. et al. The REM sleep behavior disorder screening questionnaire-a new diagnostic instrument. Mov. Disord. 22, 2386–2393 (2007).

Antelmi, E., Lippolis, M., Biscarini, F., Tinazzi, M. & Plazzi, G. REM sleep behavior disorder: mimics and variants. Sleep. Med Rev. 60, 101515 (2021).

Banwinkler, M., Dzialas, V., Parkinson’s Progression Markers, I., Hoenig, M. C. & van Eimeren, T. Gray matter volume loss in proposed brain-first and body-first Parkinson’s disease subtypes. Mov. Disord. 37, 2066–2074 (2022).

Stefani, A. et al. Low specificity of rapid eye movement sleep behavior disorder questionnaires: need for better screening methods. Mov. Disord. 38, 1000–1007 (2023).

Goetz, C. G. et al. Movement disorder Society-sponsored revision of the Unified Parkinson’s disease rating scale (MDS-UPDRS): scale presentation and clinimetric testing results. Mov. Disord. 23, 2129–2170 (2008).

Yu R. L., et al. Cross-cultural differences of the non-motor symptoms studied by the Traditional Chinese version of the international parkinson and movement disorder society- Unified Parkinson’s disease rating scale. Mov. Disord. Clin. Pract. 4, 68–77 (2016).

Beck, A. T., Steer, R. A., Ball, R. & Ranieri, W. Comparison of Beck depression inventories -IA and -II in psychiatric outpatients. J. Pers. Assess. 67, 588–597 (1996).

Zheng, Y. P., Wei, L. A., Goa, L. G., Zhang, G. C. & Wong, C. G. Applicability of the Chinese beck depression inventory. Compr. Psychiatry 29, 484–489 (1988).

van Wamelen, D. J. et al. The non-motor symptoms Scale in Parkinson’s disease: validation and use. Acta Neurol. Scand. 143, 3–12 (2021).

Wang, G. et al. Validation of the Chinese non-motor symptoms scale for Parkinson’s disease: results from a Chinese pilot study. Clin. Neurol. Neurosurg. 111, 523–526 (2009).

Hummel T., Kobal G., Gudziol H. & Mackay-Sim A. Normative data for the “Sniffin’ Sticks” including tests of odor identification, odor discrimination, and olfactory thresholds: an upgrade based on a group of more than 3,000 subjects. Eur. Arch. Otorhinolaryngol. 264, 237–243 (2007).

Tsang, K. L. et al. Translation and validation of the standard Chinese version of PDQ-39: a quality-of-life measure for patients with Parkinson’s disease. Mov. Disord. 17, 1036–1040 (2002).

Luo, W. et al. Validity and reliability testing of the Chinese (mainland) version of the 39-item Parkinson’s Disease Questionnaire (PDQ-39). J. Zhejiang Univ. Sci. B 11, 531–538 (2010).

Tomlinson, C. L. et al. Systematic review of levodopa dose equivalency reporting in Parkinson’s disease. Mov. Disord. 25, 2649–2653 (2010).

Hoops, S. et al. Validity of the MoCA and MMSE in the detection of MCI and dementia in Parkinson disease. Neurology 73, 1738–1745 (2009).

Nasreddine, Z. S. et al. Nasreddine, Z. S. et al. The Montreal Cognitive Assessment, MoCA: a brief screening tool for mild cognitive impairment [published correction appears. J. Am. Geriatr. Soc. 67, 1991 (2019).

Jia X. A comparison of the Mini-Mental State Examination (MMSE) with the Montreal Cognitive Assessment (MoCA) for mild cognitive impairment screening in Chinese middle-aged and older population: a cross-sectional study. BMC Psychiatry 1, 485 (2021).

Acknowledgements

Yilin Tang received research funding from the National Nature Science Foundation of China (82371261). Chuantao Zuo received funding from the National Nature Science Foundation of China (82272039, 82021002, 82394434, and 81971641), STI2030-Major Projects (2022ZD0211606). Jian Wang received research funding from the National Health Commission of China (Pro20211231084249000238), the National Nature Science Foundation of China (82171421, 82371432, 92249302), and the Shanghai Municipal Science and Technology Major Project (21S31902200), and AI for Science Foundation of Fudan University (FudanX24AI062). Jianjun Wu received funding from the National Health Commission of China (Pro20211231084249000238). The authors wish to thank all patients and controls involved in this research.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

(1) Research project: A. Conception, B. Organization, C. Execution; (2) Statistical Analysis: A. Design, B. Execution, C. Critical revision; (3) Manuscript: A. Draft writing, B. Critical revision. Shiyu Li: 1 A, 1B, 1 C, 2 A, 2B, 2 C, 3 A, 3B. Fangyang Jiao: 1 A, 1B, 1 C, 2 A, 2B, 2 C, 3 A, 3B. Xiuyuan Li: 1 A, 1B, 1 C, 2 A, 2B, 2 C, 3 A, 3B. Zhiheng Xu: 1 C, 2B, 2 C, 3B. Tianyu Hu: 1 C, 2B, 2 C, 3B. Xiaoniu Liang: 1 C, 2B, 2 C, 3B. Jianjun Wu: 1 C, 2B, 2 C, 3B. Jian Wang: 1 C, 2B, 2 C, 3B. Chuantao Zuo: 1 A, 1B, 2 A, 2B, 2 C, 3 A, 3B. Yilin Tang: 1 A, 1B, 2 A, 2B, 2 C, 3 A, 3B

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

All the authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Li, S., Jiao, F., Li, X. et al. Plasma GFAP and NfL associate with cerebral glucose metabolism in putative brain-first and body-first Parkinson’s disease subtypes. npj Parkinsons Dis. 11, 54 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41531-025-00898-0

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41531-025-00898-0