Abstract

Apathy is a disabling symptom in Parkinson’s disease (PD). The effect of dopaminergic treatment on apathy is inconsistent, depending on the stage of the disease, the type of apathy and strongly influenced by placebo effect. Our study assessed the evolution of a cohort of 86 de novo, drug naive PD patients for 4 years, after dopaminergic treatment introduction. The main objective of the study was the change of apathy from baseline to follow-up and secondary outcomes were the change of other neuropsychiatric symptoms. At 4 years there was an improvement of apathy (p = 0.002), mainly driven by improvement of baseline apathy (p = 0.001). This was associated with an improvement of anxiety (p = 0.001), an increase in hyperdopaminergic behavior including nocturnal hyperactivity with consecutive diurnal sleepiness (p = 0.001 and p < 0.001), independently of the presence of apathy at baseline. These findings confirm, in a large real-life cohort, that dopaminergic treatment improves motivational apathy in early PD.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Neuropsychiatric symptoms represent an important burden in Parkinson’s disease (PD) and are associated with decreased quality of life1. Apathy, anxiety and depression can occur in the premotor phase of the disease, sometimes preceding motor onset by several years2,3,4. In the early stages of the disease, this triad seems mainly related to the mesolimbic and mesocortical dopaminergic denervation, therefore defined as hypodopaminergic5,6,7, and also to serotonergic system dysfunction8. Hypodopaminergic symptoms have been proposed to be on the one extreme of the behavioral spectrum of PD, the opposite extreme being represented by hyperdopaminergic behavior, including impulsive compulsive behaviors (ICB), dopamine dysregulation syndrome (DDS), (hypo)-mania and psychosis, which are related to the sensitization of the dopaminergic system and to dopaminergic medication9,10.

In more advanced stages, apathy, anxiety and depression might be the result of the cortical spreading of Lewy body pathology and of a widespread cholinergic degeneration, and are associated with cognitive decline11,12,13,14.

Apathy is a complex neuropsychiatric syndrome, presenting as a loss of motivation and interest and a reduced goal-directed behaviors15,16,17,18. It can occur as an isolated symptom, or as part of a larger hypodopaminergic behavioral spectrum associated with depression and/or anxiety17,19 or, in later PD stages, with cognitive decline13. As a syndrome, apathy might represent the common expression of different pathophysiological processes. Several studies have suggested the implication of the dopaminergic system. Indeed, in a randomized controlled study performed in PD patients treated with subthalamic stimulation, postoperative apathy due to marked decrease of antiparkinsonian drugs was improved with dopaminergic treatment20,21,22. However, other studies provided inconsistent results on the effect of dopaminergic medication on apathy, especially at disease onset23,24. This could be related to methodological problems and to a strong placebo effect. One of the main issues is that many studies include non-homogenous populations with early and advanced disease, resulting in possibly, mixed motivational and cognitive apathetic syndromes25. Targeting de novo PD has the advantage of focusing mainly on motivational apathy, which has been related to dopaminergic and serotonergic deficit8,20,26,27. Recently, we conducted a large observational study on the evolution of neuropsychiatric symptoms in de novo, drug naïve, PD patients, the honeymoon study. Within this cohort, we performed a 6 months double-blind placebo controlled study, which failed to demonstrate the efficacy of rotigotine on apathy24. Here we present the 3-5 years follow-up of a subgroup of the patients initially included in the honeymoon study, and thus homogenous for disease stage, evolution, without cognitive impairment or device-aided therapies, with the objective to assess the evolution of apathy and other neuropsychiatric symptoms as a result of real-life treatment strategies.

Results

90 patients were assessed both at baseline before the introduction of dopaminergic treatment and at follow-up, 4 of whom were erroneously included since their Mattis Dementia Rating Scale (MDRS) score was <130 at follow-up. 86 patients were finally included in the analysis (34 with apathy at baseline according to the Starkstein apathy score ≥ 14). Mean follow-up duration was 4.25 years ± 0.60.

Demographic characteristics of patients, as well as MDS-UPDRS scores, cognitive scores, and dopaminergic medication are reported in Table 1.

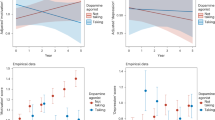

Apathy

There was a decrease of apathy, measured by Starkstein apathy scale, at last follow-up (12.6 ± 5.7 at baseline vs. 10.9 ± 5.6 at 4 years, p = 0.002, effect size = 0.30 (Confidence Interval (CI) 95%, 0.00; 0.60)). When correcting for baseline apathy, there was a significant interaction between apathy and time on the Starkstein apathy score (p < 0.001), with a greater reduction of apathy in the group of patients with apathy (Table 2 and Fig. 1).

Anxiety

When using the STAI, there was a significant improvement of both STAI state and trait at final visit in the whole population (STAI state 35.2 ± 9.7 at baseline, 31.1 ± 9.1 at 4 years, p < 0.001, effect size = 0.44 (CI 95%, 0.14; 0.74), and STAI trait 43.2 ± 10.8 at baseline, 39.1 ± 10.3 at 4 years, p < 0.001, effect size = 0.38 (CI 95%, 0.08; 0.68)). When considering the presence of baseline apathy, there was no significant interaction between apathy and time on the STAI score (Table 2).

Depression

There was no significant change at 4-years in depression as measured with the BDI-2 scale in the overall sample (10.2[5–16] at baseline, 9[6–15] at 4 years, p = 0.67, effect size = 0.04 (CI 95%, 0.00; 0.34)).

When correcting for the presence of baseline apathy, a reduction of depression was only observed in the subgroup of patients with baseline apathy (p = 0.008, Table 2).

Fatigue

There was no change in fatigue score with evolution of the disease (PFS-16 score 45 ± 17.2 at baseline, 47.2 ± 15.0 at 4 years, p = 0.28, effect size = 0.14 (CI 95%, 0.00; 0.43)). Taking into account the presence of baseline apathy, no significant interaction between time and apathy was found on the evolution of fatigue (p = 0.07,Table 2).

Hyperdopaminergic behaviors

There was an overall increase in hyperdopaminergic behaviors at last follow-up (Table 3, Fig. 2).

There was a significant increase from 16 patients with at least one hyperdopaminergic behavior at baseline (7 with nocturnal hyperactivity, 3 with eating disorder, 2 with hypersexuality, 1 with hypomania, 1 with creativity and 1 with hobbyism 19%, 1 with medication addiction) to 51 (59%) at last follow-up (p = 0.001, odds ratio= 8.0 (CI 95%, 3.2; 26.0)) (Fig. 2).

Among hyperdopaminergic behaviors, at 4-years, nocturnal hyperactivity was the most frequent (26 patients, 30%, p = 0.001, odds ratio= 5.8 (CI 95%, 2.0; 22.9)), followed by compulsive shopping (12%, p = 0.01, odds ratio= 6.0 (CI 95%, 1.3; 55.2)), hobbyism (10 patients, 12%, p = 0.004), eating disorder (9 patients, 10%, p = 0.07, odds ratio= 7.0 (CI 95%, 0.9; 315.5)), punding (7 patients, 8%, p = 0.02), hypersexuality (6 patients, 7%, p = 0.29), creativity (6 patients, 7%, p = 0.03), pathological gambling (5 patients, 6%, p = 0.06). Dopaminergic addiction was not frequent in our cohort (2 patients, 2%, p = 0.99).

When correcting for baseline apathy, no difference in the evolution of hyperdopaminergic behaviors was found.

Diurnal sleepiness

There was a significant increase in the diurnal sleepiness over time (ASBPD 0[0-0] (15 patients) at baseline vs. 1[0-1] (48 patients) at 4 years p < 0.001, effect size = 0.76 (CI 95%, 0.45; 1.07)). When considering initial apathy, no significant interaction was found between apathy and time on the evolution of diurnal sleepiness.

Neuropsychiatric fluctuations

Neuropsychiatric fluctuations became more frequent with disease evolution, with patients rather reporting OFF-dysphoria (30%) than ON euphoria (10%) (Table 1). Their frequency was slightly higher in patients with baseline apathy (35% versus 26%, Table 2).

Quality of life

At 4 years there was a significant worsening of quality of life in the whole population (PDQ39 summary index 21.7[12.9–31.2] at baseline vs. 25.3 [17.1–33.9] at 4 years, p = 0.003, effect size = 0.29 (CI 95%, 0.00; 0.059)). When considering initial apathy, there was no interaction between apathy and time on the change of quality of life.

Concerning different domains of the PDQ39, at last follow-up there was a significant improvement of emotional well-being (41.7[25–50] at first visit vs. 33.3[20.8–45.8] at last follow-up, p = 0.02, effect size = 0.26 (CI 95%, 0.00; 0.56)), and a significant worsening of: mobility (11[5–27.5] at first visit vs. 25 [10–37.5] at last follow-up, p < 0.001, effect size = 0.38 (CI 95%, 0.08; 0.68)), social support (0[0–16.7] at first visit vs. 8.3 [0-25] at last follow-up, p = 0.02, effect size = 0.27(CI 95%, 0.00; 0.57)), cognition (18.8[6.3-37.5] at first visit vs. 25[18.8–37.5] at last visit, p < 0.001, effect size = 0.36 (CI 95%, 0.06; 0.66)) and communication (8.3[0–29.5] at first visit vs. 16.7[0–33.3] at last visit, p < 0.001, effect size = 0.31 (CI 95%, 0.01; 0.61)). There was a trend in worsening of stigma (18.8 [6.2–31.3] at first visit vs. 25 [12.5–43.8] at last follow-up p = 0.05, effect size = 0.26 (CI 95%, 0.00; 0.56)).

Looking at the impact of baseline apathy, a significant interaction between apathy and time in the stigma and communication domains was found (p = 0.03 and 0.003 respectively, Table 2) with a worsening only in the group without baseline apathy.

The role of dopaminergic medication dose

The post-hoc analysis with a mixed model REML did not show any significant interaction between levodopa equivalents dose or dopamine agonists equivalents dose and the evolution of apathy, and other behaviors over time.

Discussion

Our study showed an improvement of apathy in a cohort of de novo PD at 4 years of follow-up, after introduction of dopaminergic treatment. The overall improvement of apathy was mainly driven by the improvement in patients with baseline apathy, without occurrence of apathy in non-apathetic patients at baseline.

The improvement of apathy in this cohort underlines the role of the dopaminergic system in the pathophysiology of apathy. The main change in our cohort, besides the evolution of the disease, was indeed the introduction of dopaminergic medication, which was identical in both groups of patients. The number of patients treated with antidepressant at last follow-up was the same that at baseline and could not account for the improvement of apathy. The post-hoc analysis on the effect of the dose of dopaminergic medication on the evolution of apathy was negative, indicating that the improvement of apathy by dopaminergic drugs was not dose-dependent. The occurrence of apathy after dopaminergic drugs reduction after subthalamic stimulation was not dose-dependent, but driven by the degree of mesolimbic dopaminergic denervation20. The present study appears to contradict the 6-month pharmacological de novo PD study (in which apathetic de novo patients were randomized to rotigotine versus placebo for six months), which found an improvement of apathy in both active and placebo groups of around 60%. The marked and sustained improvement of apathy at six months under placebo was unexpected and per se an important result, highlighting the potential benefit coming from a non-pharmacological and multidisciplinary management of apathy. Non-pharmacological approaches, such as cognitive behavioral therapy, have been shown to be promising in anxiety and depression in PD28,29, and are grounded on a solid framework also for apathy in PD30.

The improvement of apathy in the long-term follow-up and not at 6 months might be related first to the insufficient dose of rotigotine in the randomized controlled study (maximal dose was fixed at 8 mg, corresponding to highest recommended dose in early PD), whereas in the present study there was no limit representing the routine care practice. Moreover, reverting apathy might take longer than 6 months. On top of that, dopaminergic sensitization for motivational behaviors might be higher in patients with apathy due to mesolimbic denervation, with the need for these patients of lower doses of dopaminergic medication in the same way to what happens for motor sensitization with greater dopaminergic denervation9,10.

Other longitudinal studies in de novo PD found a stability31,32 or a worsening33,34,35,36 of apathy and neuropsychiatric symptoms at 4-5 years of follow-up. Methodological issues might explain this difference, such as different scales used to measure apathy33,36. Moreover, the prevalence of baseline apathy was lower in these studies (17% in the study of Weintraub and coll36), whereas in our population, such prevalence at baseline was of around 30%, which is considered to be representative of the prevalence of apathy in de novo PD37.

Importantly we also found a significant improvement at 4 years of anxiety in the all group of patients, in line to other longitudinal studies34,36.

A trend towards improvement of depression was also observed especially in the group of patients with baseline apathy, whereas other longitudinal studies found a slight worsening of depression at follow-up, probably because of methodological differences (scales, population)32,34,36. The improvement of anxiety independently of the presence of apathy at baseline and the lack of significant improvement of depression, possibly indicates specific, despite overlaps, anatomical, neurotransmission and functional alterations and suggests that grouping these three manifestations under a single umbrella of “hypodopaminergic triad” is over simplistic19,38.

The impact of disease evolution on neuropsychiatric symptoms is complex, with higher prevalence at disease onset and at more advanced stages, as a consequence of fluctuations, dyskinesias, impulse control disorders, and axial dopa-resistant signs, such as cognitive decline. As already mentioned, apathy is a behavioral syndrome, in which motivational, emotional and cognitive dimensions can be recognized13,39,40. Whereas in more advanced disease, apathy more often reflects a cognitive decline and thus does not respond any longer to dopaminergic treatment25, in early PD, it is more often isolated or associated to depression and anxiety, reflecting dopaminergic and serotonergic dysfunction and can be managed adjusting medical treatment.

In our cohort of early PD, patients presented mainly motivational and emotional apathy, without significant cognitive impairment after 4-year of disease evolution, explaining the ongoing improvement at last follow-up on dopaminergic treatment.

Conversely, an increase in the prevalence of cognitive impairment (defined as MOCA score < 26) of about 6% at 4 years has been found in the PPMI cohort36. This difference is probably related to our more restrictive inclusion criteria (MDRS ≥ 130), chosen in order to strictly select patients without cognitive apathy.

As expected, we found a worsening of non-motor symptoms, motor severity, and the onset of motor complications, although these remained mild at 4 years of follow-up. Fatigue significantly worsened with disease progression, similarly to what already described34,36.

Interestingly, the group of patients with baseline apathy had higher scores of fatigue both at disease onset and at follow-up. De novo apathy has been found to be associated with fatigue and anhedonia41. Fatigue is a “catch-all symptom”, used by patients to describe physical fatigue, or sleepiness, or a lack of energy or interest. Apathetic patients complain easily of fatigue. Thus, it is not surprising that apathetic patients at baseline had higher scores of fatigue. However, the lack of improvement of fatigue in this group with disease evolution, despite an improvement of apathy, suggests that different mechanisms than apathy also contribute to fatigue. The increase in fatigue with disease evolution in this study might be mainly related to the increase of diurnal sleepiness and to the worsening of motor symptoms.

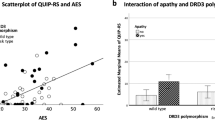

On the other side, nocturnal hyperactivity and other so-called hyperdopaminergic behaviors significantly increased at 4 years. This is not surprising since it has already been shown that impulsive compulsive behaviors are associated with dopaminergic treatment42,43, with a prevalence in de novo PD similar to that in healthy controls, as shown in the PPMI cohort44. Apathy has been hypothesized to be a risk factor for the development of ICB, because associated to a more severe mesocorticolimbic denervation, in analogy to akinesia, reflecting more severe nigrostriatal denervation, being a risk factor for dyskinesias19. However, here, the worsening of ICB and of nocturnal hyperactivity was not different in apathetic and non-apathetic patients. Nevertheless, in a post-hoc analysis of the PPMI cohort, apathy was indeed predictive of the occurrence of ICB45. Recently, Theis et al. found that both apathy and DRD3 polymorphysm were risk factors for ICB in early PD46. In our study, baseline apathy was not associated with higher occurrence of ICB. However, our population was underpowered to detect such a difference and the duration of follow up was probably too short.

Diurnal sleepiness also worsened with disease progression, probably favored by nocturnal hyperactivity in this cohort of patients, whereas it is infrequent in de novo PD47.

Concerning neuropsychiatric fluctuations, these were more common at 4 years of follow-up, as expected with disease progression48,49. Interestingly, we observed greater frequency of neuropsychiatric off than on (30% versus 10%). This could be related to a recall bias, with neuropsychiatric OFF more easily recognized and retrospectively recalled by patients, as more distressful, whereas neuropsychiatric ON are more pleasant and therefore more egosyntonic.

Despite the improvement of apathy and neuropsychiatric symptoms, quality of life significantly worsened at 4 years, with a worsening in all domains but the emotional well-being domain, which was improved. Overall, patients with baseline apathy had worse quality of life at baseline and at follow-up compared to non-apathetic ones, despite the improvement of apathy. Quality of life relies on multiple factors. In our cohort, the worsening of quality of life was probably mainly driven by the worsening of motor symptoms, and non-motor non-neuropsychiatric symptoms. This finding, although unexpected, supports the recent criticism to the old concept of “honeymoon”50, with several motor and non motor aspects, which can hamper quality of life also in early PD. The worsening in cognitive domain is not reflected by a worsening in cognitive functions. In routine care, it is not rare to have a mismatch between their judgment on cognition and the real performance on test51,52. This might be related to the lack of sensitivity for mild impairment of cognitive test. Furthermore, in PD mood disorders can participate to this subjective cognitive complain53. The improvement in emotional well-being domain can be explained by the improvement of apathy and it goes along with the improvement in communication domain in the apathetic group, which is probably related to an emotional, a motivational and cognitive “awakening” induced by dopaminergic medication. From a neuropsychiatric point of view, patients under dopaminergic medication can become talkative, with a spectrum reaching in some logorrhea and flight of ideas, and this goes along with a reduction in bradyphrenia48,54.

Our study has several limitations, first of all its sample size, which can restrain its power.

Its pharmacological nature did not allow to address potential non-pharmacological factors, which might have contributed to apathy improvement, such as cognitive-behavioral therapy or life-style change, which should be explored in the future.

Furthermore, we did not use objective measures of sleep, since the study of sleep and sleepiness was out the scope of our study. However, implementing future studies with these objective measures might be useful, in order to better define the sleep profile in early PD.

In conclusion, we showed a change in the emotional profile in a selected population of de novo PD patients without cognitive decline, with an improvement of motivational apathy and other neuropsychiatric symptoms along with an increase of hyperdopaminergic behaviors after the introduction of dopaminergic treatment. Our findings point out the need of a sustained exposure to dopaminergic treatment in order to achieve this improvement.

Methods

Study design and participants

This is a prospective multicenter French study of a cohort of de novo PD followed up for 3 to 5 years.

Patients were initially included in the honeymoon study (NCT02786667), a large observational study on neuropsychiatric symptoms, if: aged between 30 and 72 years; had a diagnosis of PD for < 2 years; with no cognitive impairment (defined as a score on the MATTIS Dementia rating scale (MDRS) < 130/144 or on Frontal assessment battery (FAB) < 15/18); no dopaminergic treatment; no active comorbidity of major psychiatric disease (no suicidal risk, no major depressive episode according to DSM IV, no active psychosis). Patients under rasagiline or antidepressant could be included provided that the treatment was stable for the last 3 months before inclusion. 198 patients were enrolled in the Honeymoon study. Within this cohort, apathetic de novo patients were enrolled in a 6-month randomized controlled study assessing rotigotine versus placebo on apathy improvement24.

The current study assessed 90 patients, initially included in the honeymoon study and followed up for 3 to 5 years (NCT03141944): 60 patients who did not present apathy at baseline, 30 patients who were apathetic at baseline (according to a score of the baseline Lille Apathy Rating Scale ≥ −21). Patients involved in the current study were required to have a confirmed diagnosis of PD, to be on dopaminergic treatment, and to have a MDRS ≥ 130.

Approval from Ethical Committee (Comité de Protection des Personnes Sud Est V) was obtained for both studies (CPP 11-CHUG-13 and 16-CHUG-23). The study was performed in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and all patients signed an informed consent.

Assessment

At both baseline and follow-up visit, patients underwent a motor assessment using the MDS-UPDRS55, as well as a thorough neuropsychological assessment. This included the Starkstein apathy scale for apathy (range 0–42)56, the Beck depression inventory-2 (BDI-2) for depression (range 0–63)57, the State-Trait Anxiety Inventory for anxiety trait (STAI-trait) and state (STAI-state)58, each ranging from 20 to 80, the Ardouin Scale of Behavior in Parkinson’s Disease (ASBPD) for apathy, anxiety, depression (each item ranging 0–4), hyperdopaminergic behaviors, and non-motor-fluctuations59, the PFS-16 for the fatigue60, the MATTIS Dementia rating scale (range 0–144)61 and the Frontal Assessment Battery (FAB, range 0–18) for cognition62. Quality of life was evaluated by PDQ-39 (the summary index (PDQ-39 SI) was calculated by the sum of dimension total scores divided by 8)63.

Dopaminergic treatment was converted to levodopa equivalent dose, according to Jost et al. 202364.

Outcome measures

The primary outcome of the study was the evolution of the apathy between baseline and follow-up visit, measured as the change in the Starkstein apathy scale. We chose the Starsktein apathy scale in this longitudinal study, instead of the Lille apathy scale65 used in the honeymoon study24, because it appears to be more sensitive to motivational apathy and to the behavioral changes following dopaminergic medication adjustment, whether the latter is more sensitive to cognitive apathy.

As secondary outcomes, we assessed the evolution over 3–5 years of: depression, measured with BDI-2; anxiety, measured with STAI state (measuring the anxiety in that precise moment) and trait (measuring long-standing anxiety); fatigue, measured with the PFS-16; hyperdopaminergic behaviors, as well as non-motor neuropsychiatric fluctuations measured with the ASBPD and quality of life, measured with the PDQ-39.

Hyperdopaminergic behaviors were assessed using ASBPD. Nocturnal hyperactivity, hypomanic mood, psychotic symptoms, punding, pathological gambling, hypersexuality, dopaminergic addiction were considered as pathological if the score in the respective item of the ASBPD was ≥ 1. Cut-off score for clinically relevant hyperdopaminergic compulsive shopping was defined as > 1 for men and > 2 for women. A patient was considered affected by clinically relevant hyperdopaminergic eating behavioral issues, creativity, hobbyism, risk taking behavior, appetitive behavior whenever her/his score in the respective item of the ASBPD was ≥ 2. This cut off is based on general population normative data of the ASBPD (unpublished data).

The impact of dopaminergic medication in the change of primary and secondary outcomes was explored as well.

Statistical analysis

Data were given as number and frequency for categorical variable, mean and standard deviation for normally distributed variables (tested with a Shapiro-Wilk test), median and interquartile range (IQR) for non-normally distributed variables. Comparisons were realized using a paired t-test, when the distribution was normal, otherwise with a Wilcoxon signed rank test. For categorical variables, a McNemar test was used.

For primary outcome, a paired t-test was used.

For secondary outcomes, a repeated measure ANOVA was realized using the factor apathy (a patient was considered apathetic whenever the score at the Starkstein apathy scale was ≥ 14). The procedure of Benjamini-Hocheberg was used for correcting for multiple comparisons across all tests (including primary and secondary outcome). The Cohen effect size and confidence interval were calculated for the paired test. Statistically significance was set to p < 0.05.

A post-hoc analysis with a mixed model REML was realized, using the total levodopa daily equivalent dose as well as the dopamine agonists dose expressed as levodopa equivalent dose.

The sample size was calculated (paired difference test) in order to show a statistically significant difference of 1,8 point with 80% of power, of 2 points with a power of 90% (considering the Starkstein apathy scale at 11.6 + /−5.9 and alpha risk of 0.05 (logiciel nQuery Advisor 7.0 -)66.

Data availability

Anonymized data of this study will be available from the corresponding author on reasonable request from any qualified researcher, following the EU General Data Protection Regulation.

References

Weintraub, D. et al. The neuropsychiatry of Parkinson’s disease: advances and challenges. Lancet Neurol. 21, 89–102 (2022).

Berg, D. et al. MDS research criteria for prodromal Parkinson’s disease. Mov. Disord. J. Mov. Disord. Soc. 30, 1600–1611 (2015).

Schrag, A., Horsfall, L., Walters, K., Noyce, A. & Petersen, I. Prediagnostic presentations of Parkinson’s disease in primary care: a case-control study. Lancet Neurol. 14, 57–64 (2015).

Kazmi, H. et al. Late onset depression: dopaminergic deficit and clinical features of prodromal Parkinson’s disease: a cross-sectional study. J. Neurol. Neurosurg. Psychiatry 92, 158–164 (2021).

Ardouin, C. et al. Assessment of hyper- and hypodopaminergic behaviors in Parkinson’s disease. Rev. Neurol. (Paris) 165, 845–856 (2009).

Sampedro, F., Martínez-Horta, S., Marín-Lahoz, J., Pagonabarraga, J. & Kulisevsky, J. Apathy Reflects Extra-Striatal Dopaminergic Degeneration in de novo Parkinson’s Disease. J. Park. Dis. 12, 1567–1574 (2022).

Costello, H. et al. Longitudinal decline in striatal dopamine transporter binding in Parkinson’s disease: associations with apathy and anhedonia. J. Neurol. Neurosurg. Psychiatry 94, 863–870 (2023).

Maillet, A. et al. Serotonergic and Dopaminergic Lesions Underlying Parkinsonian Neuropsychiatric Signs. Mov. Disord. J. Mov. Disord. Soc. 36, 2888–2900 (2021).

Castrioto, A. et al. Psychostimulant effect of levodopa: reversing sensitisation is possible. J. Neurol. Neurosurg. Psychiatry 84, 18–22 (2013).

Castrioto, A. et al. Reversing dopaminergic sensitization. Mov. Disord.: J. Mov. Disord. Soc. 32, 1679–1683 (2017).

Dujardin, K., Sockeel, P., Delliaux, M., Destée, A. & Defebvre, L. Apathy may herald cognitive decline and dementia in Parkinson’s disease. Mov. Disord.: J. Mov. Disord. Soc. 24, 2391–2397 (2009).

Martin, G. P., McDonald, K. R., Allsop, D., Diggle, P. J. & Leroi, I. Apathy as a behavioural marker of cognitive impairment in Parkinson’s disease: a longitudinal analysis. J. Neurol. 267, 214–227 (2020).

Béreau, M. et al. Motivational and cognitive predictors of apathy after subthalamic nucleus stimulation in Parkinson’s disease. Brain J. Neurol. 147, 472–485 (2024).

Pedersen, K. F., Alves, G., Aarsland, D. & Larsen, J. P. Occurrence and risk factors for apathy in Parkinson disease: a 4-year prospective longitudinal study. J. Neurol. Neurosurg. Psychiatry 80, 1279–1282 (2009).

Levy, R. Apathy: a pathology of goal-directed behaviour: a new concept of the clinic and pathophysiology of apathy. Rev. Neurol. (Paris) 168, 585–597 (2012).

Santangelo, G. et al. Apathy in Parkinson’s disease: diagnosis, neuropsychological correlates, pathophysiology and treatment. Behav. Neurol. 27, 501–513 (2013).

Pagonabarraga, J., Kulisevsky, J., Strafella, A. P. & Krack, P. Apathy in Parkinson’s disease: clinical features, neural substrates, diagnosis, and treatment. Lancet Neurol. 14, 518–531 (2015).

Le Heron, C., Holroyd, C. B., Salamone, J. & Husain, M. Brain mechanisms underlying apathy. J. Neurol. Neurosurg. Psychiatry 90, 302–312 (2019).

Castrioto, A., Thobois, S., Carnicella, S., Maillet, A. & Krack, P. Emotional manifestations of PD: Neurobiological basis. Mov. Disord. J. Mov. Disord. Soc. 31, 1103–1113 (2016).

Thobois, S. et al. Non-motor dopamine withdrawal syndrome after surgery for Parkinson’s disease: predictors and underlying mesolimbic denervation. Brain J. Neurol. 133, 1111–1127 (2010).

Lhommée, E. et al. Subthalamic stimulation in Parkinson’s disease: restoring the balance of motivated behaviours. Brain J. Neurol. 135, 1463–1477 (2012).

Thobois, S. et al. Parkinsonian apathy responds to dopaminergic stimulation of D2/D3 receptors with piribedil. Brain J. Neurol. 136, 1568–1577 (2013).

Seppi, K. et al. Update on treatments for nonmotor symptoms of Parkinson’s disease-an evidence-based medicine review. Mov. Disord. J. Mov. Disord. Soc. 34, 180–198 (2019).

Castrioto, A. et al. A randomized controlled double-blind study of rotigotine on neuropsychiatric symptoms in de novo PD. npj Park. Dis. 6, 41 (2020).

Béreau, M. et al. Apathy in Parkinson’s Disease: Clinical Patterns and Neurobiological Basis. Cells 12, 1599 (2023).

Remy, P., Doder, M., Lees, A., Turjanski, N. & Brooks, D. Depression in Parkinson’s disease: loss of dopamine and noradrenaline innervation in the limbic system. Brain J. Neurol. 128, 1314–1322 (2005).

Prange, S. et al. Early limbic microstructural alterations in apathy and depression in de novo Parkinson’s disease. Mov. Disord. J. Mov. Disord. Soc. 34, 1644–1654 (2019).

Piers, R. J., Farchione, T. J., Wong, B., Rosellini, A. J. & Cronin-Golomb, A. Telehealth Transdiagnostic Cognitive Behavioral Therapy for Depression in Parkinson’s Disease: A Pilot Randomized Controlled Trial. Mov. Disord. Clin. Pract. 10, 79–85 (2023).

Reynolds, G. O., Saint-Hilaire, M., Thomas, C. A., Barlow, D. H. & Cronin-Golomb, A. Cognitive-Behavioral Therapy for Anxiety in Parkinson’s Disease. Behav. Modif. 44, 552–579 (2020).

Plant, O. et al. A Cognitive-Behavioral Model of Apathy in Parkinson’s Disease. Park. Dis. 2024, 2820257 (2024).

Wee, N. et al. Baseline predictors of worsening apathy in Parkinson’s disease: A prospective longitudinal study. Parkinsonism Relat. Disord. 23, 95–98 (2016).

Dlay, J. K. et al. Progression of Neuropsychiatric Symptoms over Time in an Incident Parkinson’s Disease Cohort (ICICLE-PD). Brain Sci. 10, 78 (2020).

Erro, R. et al. Non-motor symptoms in early Parkinson’s disease: a 2-year follow-up study on previously untreated patients. J. Neurol. Neurosurg. Psychiatry 84, 14–17 (2013).

Erro, R. et al. Clinical clusters and dopaminergic dysfunction in de-novo Parkinson disease. Parkinsonism Relat. Disord. 28, 137–140 (2016).

Ou, R. et al. Evolution of Apathy in Early Parkinson’s Disease: A 4-Years Prospective Cohort Study. Front. Aging Neurosci. 12, 620762 (2020).

Weintraub, D. et al. Neuropsychiatric symptoms and cognitive abilities over the initial quinquennium of Parkinson disease. Ann. Clin. Transl. Neurol. 7, 449–461 (2020).

den Brok, M. G. H. E. et al. Apathy in Parkinson’s disease: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Mov. Disord. J. Mov. Disord. Soc. 30, 759–769 (2015).

Prange, S., Klinger, H., Laurencin, C., Danaila, T. & Thobois, S. Depression in Patients with Parkinson’s Disease: Current Understanding of its Neurobiology and Implications for Treatment. Drugs Aging 39, 417–439 (2022).

Eglit, G. M. L. et al. Delineation of Apathy Subgroups in Parkinson’s Disease: Differences in Clinical Presentation, Functional Ability, Health-related Quality of Life, and Caregiver Burden. Mov. Disord. Clin. Pract. 8, 92–99 (2021).

Ang, Y.-S., Lockwood, P., Apps, M. A. J., Muhammed, K. & Husain, M. Distinct Subtypes of Apathy Revealed by the Apathy Motivation Index. PLOS ONE 12, e0169938 (2017).

Dujardin, K. et al. Apathy in untreated early-stage Parkinson disease: relationship with other non-motor symptoms. Mov. Disord.: J. Mov. Disord. Soc. 29, 1796–1801 (2014).

Weintraub, D. et al. Impulse control disorders in Parkinson disease: a cross-sectional study of 3090 patients. Arch. Neurol. 67, 589–595 (2010).

Weintraub, D., David, A. S., Evans, A. H., Grant, J. E. & Stacy, M. Clinical spectrum of impulse control disorders in Parkinson’s disease. Mov. Disord.: J. Mov. Disord. Soc. 30, 121–127 (2015).

Weintraub, D. et al. Cognitive performance and neuropsychiatric symptoms in early, untreated Parkinson’s disease. Mov. Disord.: J. Mov. Disord. Soc. 30, 919–927 (2015).

Maggi, G., Loayza, F., Vitale, C., Santangelo, G. & Obeso, I. Anatomical correlates of apathy and impulsivity co-occurrence in early Parkinson’s disease. J. Neurol. 271, 2798–2809 (2024).

Theis, H. et al. Impulsive-compulsive behaviour in early Parkinson’s disease is determined by apathy and dopamine receptor D3 polymorphism. npj Park. Dis. 9, 154 (2023).

Simuni, T. et al. Correlates of excessive daytime sleepiness in de novo Parkinson’s disease: A case control study. Mov. Disord.: J. Mov. Disord. Soc. 30, 1371–1381 (2015).

Witjas, T. et al. Nonmotor fluctuations in Parkinson’s disease: frequent and disabling. Neurology 59, 408–413 (2002).

Martínez-Fernández, R., Schmitt, E., Martinez-Martin, P. & Krack, P. The hidden sister of motor fluctuations in Parkinson’s disease: A review on nonmotor fluctuations. Mov. Disord. J. Mov. Disord. Soc. 31, 1080–1094 (2016).

Alonso-Canovas, A. et al. The Early Treatment Phase in Parkinson’s Disease: Not a Honeymoon for All, Not a Honeymoon at All?. J. Park. Dis. 13, 323–328 (2023).

Pennington, C., Duncan, G. & Ritchie, C. Altered awareness of cognitive and neuropsychiatric symptoms in Parkinson’s disease and Dementia with Lewy Bodies: A systematic review. Int. J. Geriatr. Psychiatry 36, 15–30 (2021).

Zakrzewski, J. J. et al. Subjective cognitive complaints and objective cognitive impairment in hoarding disorder. Psychiatry Res. 307, 114331 (2022).

Barbosa, R. P. et al. Cognitive complaints in Parkinson’s disease patients: from subjective cognitive complaints to dementia and affective disorders. J. Neural Transm. Vienna Austria 1996 126, 1329–1335 (2019).

Maricle, R. A., Nutt, J. G. & Carter, J. H. Mood and anxiety fluctuation in Parkinson’s disease associated with levodopa infusion: preliminary findings. Mov. Disord.: J. Mov. Disord. Soc. 10, 329–332 (1995).

Goetz, C. G. et al. Movement Disorder Society-sponsored revision of the Unified Parkinson’s Disease Rating Scale (MDS-UPDRS): scale presentation and clinimetric testing results. Mov. Disord.: J. Mov. Disord. Soc. 23, 2129–2170 (2008).

Starkstein, S. E. et al. Reliability, validity, and clinical correlates of apathy in Parkinson’s disease. J. Neuropsychiatry Clin. Neurosci. 4, 134–139 (1992).

Beck, A. T., Steer, R. A. & Brown, G. K. Manual for the Beck Depression Inventory-II. (Psychological Corporation, San Antonio, TX, 1996).

Spielberger, C. D., Gorsuch, R. L., Lushene, R., Vagg, P. R. & Jacobs, G. A. Manual for the State-Trait Anxiety Inventory. (Consulting Psychologists Press, Palo Alto, CA, 1983).

Rieu, I. et al. International validation of a behavioral scale in Parkinson’s disease without dementia. Mov. Disord. J. Mov. Disord. Soc. 30, 705–713 (2015).

Brown, R. G., Dittner, A., Findley, L. & Wessely, S. C. The Parkinson fatigue scale. Parkinsonism Relat. Disord. 11, 49–55 (2005).

Mattis, S. Dementia Rating Scale. Professional Manual. (Psychological Assessment Resources, Odessa, 1988).

Dubois, B., Slachevsky, A., Litvan, I. & Pillon, B. The FAB: a Frontal Assessment Battery at bedside. Neurology 55, 1621–1626 (2000).

Jenkinson, C., Fitzpatrick, R., Peto, V., Greenhall, R. & Hyman, N. The Parkinson’s Disease Questionnaire (PDQ-39): development and validation of a Parkinson’s disease summary index score. Age Ageing 26, 353–357 (1997).

Jost, S. T., et al. Levodopa Dose Equivalency in Parkinson’s Disease: Updated Systematic Review and Proposals. Mov. Disord. J. Mov. Disord. Soc. 38, 1236–1252 (2023).

Sockeel, P. et al. The Lille apathy rating scale (LARS), a new instrument for detecting and quantifying apathy: validation in Parkinson’s disease. J. Neurol. Neurosurg. Psychiatry 77, 579–584 (2006).

O’Brien, R. G., Muller, K. E. Applied Analysis of Variance in Behavioral Science. in 297–344 (Marcel Dekker, 1993).

Acknowledgements

The honeymoon study was an Investigator-Initiated Study, where UCB provided financial support. The follow-up study was funded by a grant of French Parkinson Association. We thank Deborah Amstutz for her advices.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

A.C.: Study Design, Data collection and interpretation, Draft writing and revision. E.S., E.L., A.B., S.T., P.K.: Study Design, Data collection, manuscript revision. D.S.: Data analysis and interpretation, manuscript revision. M.A., S.M., H.K., C.T., V.F., E.M., P.P.: data collection and interpretation, manuscript revision.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

A.C. received a research grant from Medtronic (to the institution), reimbusement for scientific meetings from ABBVIE, honoraria for lectures from MDS and ABBVIE, M.A.: Abbvie, Merz, Aguettant, Biogen Pharmaceuticals, Ipsen Pharma, Linde, Ever Pharma, Medtronic. S.M. received research grant support from Medtronic, Newronika, Grenoble Alpes University, Huntington’s Disease Network. V.F.: Consultancy fees from AbbVie France, Honorarium from MEDTRONIC. C.T.: AbbVie, IPSEN, Lynde. E.M. is an associated editor of npj Parkinson ́s Disease. E.M. has received honoraria from Medtronic for consulting services. She has also received restricted research grants from the Grenoble Alpes University, France Parkinson, IPSEN and Abbott. S.T. received grant from ANR, Neuratris, Boston Scientific, personal fees for conferences from Merz, Aguettant, NHC, for board/consulting from ABBVIE, Medtronic, Boston Scientific, for meetings from MDS and ABBVIE. P.K.: reports research or educational grants from Swiss National Science Foundation, ROGER DE SPOELBERCH Foundation, Fondation Louis-Jeantet, Carigest, Institut National de la Santé et de la Recherche Médicale, France Parkinson, Edmond Safra Philantropic Foundation, Bertarelli Foundation, Annemarie Opprecht Foundation, Parkinson Schweiz, Michael J Fox Foundation, Aleva Neurotherapeutics, Boston Scientific, Medtronic, St. Jude Medical, GE Healthcare, Idorsia, UCB, all paid to employing institutions; lecturing fees to employing institution from Boston Scientific, Bial, Advisis; travel expenses to scientific meetings from Boston Scientific, Zambon, Abbvie, Merz Pharma (Schweiz) AG. E.S., H.K., E.L., A.B., D.S., P.P.: declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Castrioto, A., Schmitt, E., Anheim, M. et al. Improvement of apathy in early Parkinson’s disease. npj Parkinsons Dis. 11, 89 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41531-025-00937-w

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41531-025-00937-w