Abstract

Previous studies found that specialised allied health interventions in people with Parkinson’s disease (PD) are associated with fewer complications and lower costs, as compared to usual care. Here we studied the association between specialised physiotherapy with mortality risk in a real world setting. We performed a retrospective cohort study using a health insurance claims database capturing persons with PD in the Netherlands with a follow-up of ten years. In persons treated for PD-related indications (n = 37,729), specialised physiotherapy was associated with a lower mortality rate ratio (0.89; 95% CI [0.86; 0.92]; P < 0.0001) than usual care physiotherapy. The association was attenuated in persons with PD with worse mental health (1.00), higher healthcare costs (0.91) in the year prior to enrolment and for females (0.91). These findings suggest that specialised physiotherapy for PD-related indications may delay death in persons with PD, although we cannot exclude the possibility of residual confounding.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Parkinson’s disease (PD) is a neurodegenerative disease with rapidly increasing prevalence rates1 and age-adjusted mortality risk2,3,4. This has led some to label the secular trends as reflecting a “Parkinson Pandemic”5. Treatments to ameliorate symptoms include medication or device-aided therapies which can improve motor symptoms and functioning in everyday life6,7,8. Allied healthcare offers complementary treatment with increasingly promising results, studied thus far most extensively for physiotherapy9,10,11,12. Physiotherapy can, for example, improve gait, balance, and dual task performance. Positive effects have been reported on fall risk, motor and non-motor symptoms13,14,15,16,17,18, leading to better functioning in daily life as well as improved quality of life11,19,20, especially when delivered intermittently over a longer period of time21. To optimize the effects of allied health therapy, specialisation of professionals is warranted, through baseline training and managing a higher caseload. Such specialisation is associated with better clinical results22.

The Dutch ParkinsonNet is an example of how specialisation of healthcare professionals can be organized. ParkinsonNet is a community-based professional network of healthcare providers delivering care for persons with parkinsonism in which specialised therapists are educated in all aspects of the disease and who treat at least five persons with PD each year23. Professionals are educated in PD-specific knowledge by (1) a mandatory basic 3-day training program, according to the latest treatment guidelines; (2) follow-up regional interdisciplinary meetings that must be attended three times per year; and (3) a yearly conference, where the latest scientific evidence is presented (mandatory attendance once every two years). In the Netherlands, there is no other national certification in Neurological Physiotherapy besides the ParkinsonNet model of care for persons with Parkinson’s disease.

The evidence to support the ParkinsonNet approach has been growing since its initial implementation in the Netherlands in 201024,25,26. In a previous study, we showed that specialised physiotherapy given via ParkinsonNet compared to usual care physiotherapy is associated with fewer PD complications (odds ratio 0.67, 95% CI [0.56–0.81], p < 0.0001), while requiring fewer physiotherapy session and having less healthcare costs. Interestingly, we also found lower mortality, but this association was no longer statistically significant after adjustment for confounding variables27. The observed association with lower mortality may also have been affected by a type II error because of the relatively small sample size and short follow-up period.

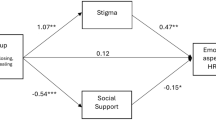

While specialised physiotherapy is not aimed primarily at reducing the mortality risk, better physiotherapy care may indirectly impact survival by improving psychological wellbeing and by reducing potentially lethal complications such as fall-related injuries or infections such as aspiration pneumonia, which are known predictors of mortality28,29. Persons with PD receiving physiotherapy are generally more likely to have greater disease severity and poorer quality of life. Therefore, the chances of benefitting from interventions that reduce e.g. infections may have a larger impact on mortality in this sub-group than in the general population of persons with PD30.

In our previous study27, we had access to a medical claims database of one large health insurer in The Netherlands with a market-share of 22%. The follow-up period in this study was only 3 years. In that paper, we included a sensitivity analysis that identified a positive effect on mortality, but we interpreted those findings very cautiously because a study of mortality rates was not our main aim. However, these promising findings did motivate us to hypothesise that specialized physiotherapy for PD-related indications might be associated with a lower mortality rate compared to the mortality rate of persons with PD receiving usual care physiotherapy. We expected that this association is mediated by a reduction in PD-related complications as having a hospital visit or admission because of sustaining a fracture, other orthopaedic injuries, or pneumonia. And we subsequently took this hypothesis to the test in a new dedicated study. Here, we report on these findings.

Results

Baseline comparisons

We observed 63,736 individuals with a diagnosis of PD between January 1, 2010, and December 31, 2019, of whom 50,511 (79.3%) received physiotherapy for any indication and 37,729 (59.2%) received physiotherapy for PD-related indications. Compared to the usual care group, the specialised group was slightly younger (0.33 years, p < 0.0009), had a somewhat lower proportion of females (6.1%, p < 0.0001), a lower prevalence of the use of at least two antiparkinsonian drugs (5.3%, p < 0.0001), lower hospital-related healthcare costs (689 Euros, p < 0.0001), lower occurrence of PD-related complications (0.02, p < 0.0001) and lower long-term care related costs (103 Euros, p < 0.01) in the year prior to enrolment (Table 1). The use of mental healthcare (0.02, p < 0.0001) and use of anti-depressive medication (0.01, p < 0.0003) were similar but a little lower in the specialist physiotherapy group (Table 1). For the group including all indications physiotherapy most persons with PD in the usual care group (67%) enrolled prior to January 1st 2015, while most persons with PD in the specialised care group (57%) enrolled thereafter. For the group including PD-related physiotherapy this was 73% vs 64%. In Supplementary Table 1, health-care use during the study period for PD-related physiotherapy is presented.

Primary analyses

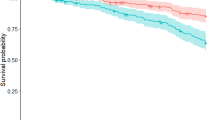

In the sub-group receiving physiotherapy for PD-related indications, we found that 3818 (28%) persons with PD in the specialised physiotherapy group and 15,454 (42%) in the usual care group died during a median follow-up duration of 3.81 and 4.77 years respectively. Compared to usual care, specialised physiotherapy for PD-related indications was associated with a mortality rate ratio of 0.89 (95% CI [0.86; 0.92]; P < 0.0001) (Table 2). The same analysis performed in the total sample of persons receiving physiotherapy for any indication showed a mortality rate ratio of 0.97 (95% CI, [0.93–1.00]; P = 0.07). For non-PD-related indications, the mortality rate ratio of specialized physiotherapy compared to usual care physiotherapy was elevated at 1.15 (95% CI [1.05–1.27]; P = 0.004).

Stratified subgroup analyses

The association between specialised physiotherapy and mortality for persons receiving physiotherapy for PD-related complications was generally similar across all our pre-specified strata. However, there was weak evidence (all p-values between 0.01 and 0.06) for potential effect modification by total hospital costs, use of mental health care, and use of depression medication. In each analysis the strata indicating worse health showed weaker or no benefits. For example, use of medication for depression had a MRR of 1.00 (95% CI 0.88–1.14), while not using medication for depression showed a MRR of 0.88 (95% CI 0.85–0.91). The associations did not vary by gender, age, socioeconomic status, PD medication use and long-term care enrolment (see Table 3).

Secondary analyses

Different thresholds for the number of sessions receiving specialised physiotherapy impacted the results, as shown in Table 4. Reduced mortality was seen at all thresholds for specialised physiotherapy. If anything, benefits were more modest in those receiving all their sessions from a specialist (Supplementary Tables 2 and 3 show extensive dose response threshold variations of specialised physiotherapy with mortality).

The results did not vary by time interval or by calendar period (Table 5). After additional adjustment for other specialised allied health therapy, the association between specialised physiotherapy and mortality attenuated somewhat (MRR = 0.95, 95% CI [0.91; 0.99]). The association did not meaningfully change after additional adjustment for complications (MRR = 0.89, 95% CI [0.85; 0.92]), urbanicity (MRR = 0.89, 95% CI [0.85; 0.92]) or hospital type (MRR = 0.89, 95% CI [0.85; 0.92]).

Sensitivity analysis to provide insight into possible immortal time bias showed no change in results when ruling out persons with PD with low physiotherapy costs and allocation by first session (generic or specialised (Supplementary Table 4) or dropping persons with PD with low cost for neurology visits for PD during follow-up time (Supplementary Table 5). However, the analysis whereby the intervention was categorized based on the first type of physiotherapy showed a modest attenuation of effect. There was some attenuation of the association after accounting for immortal time bias by reallocating person-time prior to specialised physiotherapy to the usual care arm for individuals who first received usual care physiotherapy (MRR = 0.97, 95% CI [0.93; 1.00]). The stratified analyses by indication of physiotherapy differed with benefits for PD-related indications (MRR = 0.86, 95% CI [0.81; 0.91]) whilst there was an unexpected increased mortality for physiotherapy for non-PD-related indications (MRR = 1.15, 95% CI [1.05; 1.27]) (Supplementary Table 6). Furthermore, in separate sensitivity analyses, we repeated the main analysis in tertile strata defined by a standardized propensity score, which included all covariables of the primary analysis. The association of specialized physiotherapy with mortality was similar across strata defined by a propensity score, with MRR estimates varying between 0.79, 95% CI [0.68; 0.91] in tertile 3 and 0.89 [0.83; 0.95] in tertile 2.

Discussion

Previous studies have shown an inverse association between specialised physiotherapy and the incidence of PD-related complications in persons with PD, in particular for those complications that generally do not respond well to pharmacotherapy, such as falls or pneumonia27,31. The novel finding here is that specialised physiotherapy is modestly associated with a reduced mortality rate in persons with PD. This risk reduction was only present when looking at physiotherapy provided for PD-related indications and was weaker in persons with PD with mental health care or those using anti-depression medication. This finding is clinically plausible and consistent with our original hypothesis, as physiotherapists with specialized training for PD should have a specific impact only on PD-related issues. If these associations are indeed causal, then they would suggest that specialised physiotherapy may delay death in persons with PD. Surprisingly, we observed that specialised physiotherapy was associated with a higher mortality rate for persons who received physiotherapy for non-PD-related indications, which was not predicted a priori. However, we must be careful in drawing conclusions with regard to causality based on these analyses of observational data. If specialised physiotherapy has a causal protective effects on mortality risk, then how might this operate? Possible mediators are an improvement of general health status including cardiorespiratory fitness, tools to improve self-management of disease-related challenges, a sustained improvement in mobility in daily functioning, and the prevention of PD-related complications. We had very limited data to test the possible mediating effects of these hypothetical pathways. Additional adjustment for PD-related complications during the study period did not attenuate the inverse association of specialised physiotherapy and mortality in this study, as one might have expected. However, it is conceivable that some PD-related complications did not elicit hospitalisation but did ultimately contribute to an earlier death. We previously showed that the delivery of other specialised therapy, such as occupational therapy or speech-language therapy, is also associated with a lower incidence rate of PD-related complications24. In this study, the inverse association between specialised therapy and mortality attenuated somewhat after additional adjustment for other specialised allied health therapy, suggesting that part of the putative protective effect may be mediated by collaboration between specialised therapists working together around persons with PD. Such a multidisciplinary collaboration is indeed part of the overall ParkinsonNet approach.

Another possible explanation is that our results may be confounded by demographic factors and disease severity which determine both mortality and the type of physiotherapy that persons with PD receive, due to referral bias. It is plausible that highly educated persons with PD, with a lower mortality risk, are more likely to know about the potential benefits and thus request specialised therapy. Similarly, persons with PD treated by a movement disorders specialist -rather than by a general neurologist- may have been preferentially referred to specialised physiotherapists and may therefore have better outcomes. Our data did not support these explanations, as both groups were very similar in socioeconomic status and proxy measures of clinical severity at baseline. We addressed confounding by adjusting for all available measures of disease severity, comorbidity and overall health. We used PD medication and cost-of-illness because they are closely linked to disease severity and QoL32. In addition, accepted indicators for comorbidities such as Elixhauser or Charlson Comorbidity Index can be approximated with appropriate models in medical claims data with models including age, gender, counts of prescriptions, hospital claims or diagnosis clusters which can be equal predictors for future healthcare expenditures33. However, we did not have detailed clinical measures such MDS-UPDRS rating scale or measures of frailty. As a proxy, we examined changes in medication (type or dosage) during the study period in a post-hoc analysis. We observed that upscaling of medication occurred at similar rates in both physiotherapy groups in the first 5 years after diagnosis, and that – after 5 years – upscaling of medication occurred slightly earlier in the group treated by a specialized physiotherapist. This could either reflect that the group treated by a specialized physiotherapist had more rapid progression of clinical severity, or – alternatively – that part of the inverse association of specialized physiotherapy with PD-related complications is attributable to the specialized care’s network effect. So, despite our best efforts, we cannot exclude the possibility that residual confounding is (partly) driving the association.

A third explanation to consider is immortal time bias. We examined whether this occurred through several sensitivity analyses. When we reallocated the person-time prior to specialised physiotherapy to the usual care arm for individuals who first received usual care physiotherapy, we observed an attenuation of the main association, suggesting that immortal bias may partially contribute to our main observation. We found no further evidence for immortal time bias in our other sensitivity analyses, which involved excluding persons with PD with low physiotherapy costs, excluding persons with PD with low cost for neurology visits for PD, or allocating the level of physiotherapy based on the first session of therapy received.

Another explanation of our results relates to a form of “secular time bias” due to changes in mortality over time in clinical practice. ParkinsonNet, which forms a network of specialised physiotherapists and other (allied) health specialists, has developed and grown during our observation period. In the first five years of the follow-up period, specialised care was not the standard of care but it has increasingly become more common over time. Until 2015, allocation to specialised or usual care physiotherapy was based on the choices of persons with PD and referring physicians. Since 2016 there has been a growing financial incentive to opt for specialised care after one Dutch health insurer selectively contracted specialised allied health therapy. Other major insurers later followed. To correct for this potential bias we added the year of follow up start as a covariate and performed analyses on different time intervals. These analyses did not show evidence for temporal selection bias. Somewhat surprisingly, these analyses neither showed any clear amplification of the putative beneficial effects of specialised physiotherapy over time, as one might have expected as physiotherapists became more experienced at delivering specialised care. A possible explanation for this is that there was a massive influx of new physiotherapists during the study period, from 543 in 2010 to 1457 in 2019. This means that the average level of experience of ParkinsonNet-affiliated physiotherapists was not higher in 2019 than it was in 2010. An alternative explanation could be that an 11% relative mortality reduction represents the maximum protective effect of specialised physiotherapy in a real life population.

Not all results were in line with our hypothesis. In particular, we did not observe a dose-response relationship between the proportion of specialised care received and mortality rates. This finding is not supportive of a casual protective effect, as one would expect an amplification -or at least no reduction- of effects as the proportion of specialised care received increases. Another unexpected finding is that the mortality rate was increased for persons with PD receiving specialised physiotherapy for non-PD-related indications, compared to usual care physiotherapy. It might be plausible to expect no differences between specialized and usual care physiotherapy for those with non-PD indications. In theory, it is conceivable that “specialized” physiotherapists well versed in more than just PD – given their interest toward furthering their education and advancing their expertise. However, it is also conceivable that a physiotherapist only focuses on a single specialization – such as PD –, which would in fact make them less likely than other physiotherapists to specialize in other mortality-related diseases – such as COPD or diabetes mellitus.

The observational design of our research has some specific strengths and limitations34. A strength is the external validity of this study, which allows for extrapolation of the results to similar populations. The results are not based on a selected populations which are usually recruited into clinical trials, as recently shown in an analysis of studies performed in our own movement disorder center35. The use of healthcare claims data on all persons with PD in the Netherlands means that we did not exclude persons with PD based on disease severity, sex, ethnicity, co-morbidities, or any other reasons. Generalising these results to other countries with different health care systems warrants some caution, because of the specific universal social health insurance approach with public and private insurance in the Netherlands36. The major limitation of our study is the possibility of residual sources of bias because of the observational nature of this study. Potential bias has been discussed in detail in the previous sections. It is becoming increasingly clear that PD is not only a highly debilitating disease, but that survival is also reduced37,38. Common causes of death include pneumonia which is often secondary to aspiration as a result of immobility and dysphagia39,40. Other complications from PD such as injuries resulting from falls will also contribute to an increased mortality – hip fractures are particularly notorious in this regard41. These causes of death are difficult to alleviate with even optimal medical management (pharmacotherapy, deep brain surgery). In contrast, there is increasing evidence to suggest that allied health interventions can ameliorate some of these underlying causes of death; for example, dedicated speech-language therapy can improve dysphagia and thus help to prevent aspiration pneumonia, while dedicated physiotherapy plus occupational therapy can reduce falls and related injuries. Whether such non-pharmacological treatment strategies also translate into prolonged survival was thus far unclear, as this requires a long-term follow-up.

Our results are suggestive that specialized physiotherapy may reduce mortality risk, but because of the observational nature of this study we cannot definitively establish a causal protective effect. Currently, novel integrated care models (PRIME-NL or PRIME-UK) are being developed which include close collaboration between specialized therapists across an array of disciplines42,43,44 using both natural experiment and randomised designs. These evaluations will provide further insights onto the possible merits of specialised care. These more integrated models may or may not have stronger protective effects on mortality for persons with PD. Future research should also test whether specialised allied health therapy is effective for persons with PD living in long-term care facilities, which is a growing population45. There is also a need to test the generalizability of any benefits to other high income and low middle income country settings. Finally, it will be interesting to study whether this specialised allied care approach may have benefits for other chronic progressive diseases as well.

Methods

Study design

We used a national administrative claims database (Vektis), which contains the data of over 99% of the Dutch population. Vektis is the health care information centre in the Netherlands, established by health care insurers, with the responsibility to collect and analyse data on the costs and quality of health care46. We undertook a retrospective cohort study using data from January 1st, 2010, to December 31st, 2019. In the Netherlands, to have a health insurance is a legal obligation for everyone who lives or works in the Netherlands. The insurance covers the costs of, for example, consulting a GP, hospital treatment, medication and allied health therapy. Persons with PD were identified by the Diagnosis-Related Group (DRG) code 0501 (PD) using records of the neurological departments (0330 medical specialists neurology) of all hospitals in the Netherlands and in addition received physiotherapy. The medical claims database used for this study consists of data on costs of all types of care including hospital care, but also the general practitioner, pharmaceutics, allied health care and costs related to long stay care facilities. This enables us to get a more detailed insight in co-morbidities and other possible confounders. We did not exclude persons with PD for example on the basis of ethnicity, co-morbidities, age or any other reasons. These data therefore represent a real world cohort of all insured persons in the Netherlands with PD who are being treated on a regular basis by a neurologist in combination with a physiotherapist. An overview of the Dutch healthcare system and services covered is given elsewhere36.

Inclusion criteria

We extracted data from all persons with PD who had received physiotherapy at any time postdiagnosis. Follow-up time started on the first date on which an individual received physiotherapy after the diagnosis PD by a neurologist. Follow-up time ended either because of death, emigration or individuals were censored on December 31st, 2019. In the main analysis, these dates were restricted to physiotherapy received for PD-related indications. Research shows that persons with PD can be identified fairly accurately compared to clinical assessment based on medical claims data47,48,49.

Classifying specialised and usual care physiotherapy

All physiotherapist in the Netherlands have access to evidence-based guidelines (including the European Guidelines). Core areas of physiotherapy described in the EU guidelines were gait, balance, transfers, physical capacity and dexterity10. Intervention types were education, exercise, practice (skill training) or compensation strategies. Physiotherapy was classified as specialised if the practitioner was registered with the Dutch national ParkinsonNet. To comply with this registration, the practitioner had followed a dedicated three day training in PD-specific knowledge and competencies. In addition, the practitioner worked according to the latest guidelines, was part of a regional, multidisciplinary PD professional network, and had a relatively high case load of persons with PD (>5 per year)50,51. This specialized network approach has been described in detail elsewhere50,51,52. The physiotherapists classified as usual care did not receive any of these components of the ParkinsonNet approach. Similar to our previous research27, persons with PD who received ≥75% of their sessions (based on cost data) from a specialized therapist were classified as having received specialized physiotherapy, while others were classified as having received usual care physiotherapy. The ≥75% cut-off was chosen as it allows for missing sessions given by the specialist due to sick leave, continuing education or holidays.

Outcome

Mortality was based on information from the Personal Records Database (BRP) of the National Office for Identity Data (RvIG) which is a part the national Dutch Government53,54. This database contains data of all Dutch citizens and includes the date of death for any deceased person. All Dutch health insurers receive information about their enrolees from this database and this data is included in the Vektis database we used here. For this study we do not take in account whether death was caused by PD because cause specific mortality is not available in the Vektis database but we merely look whether death did or did not occur in this population.

Covariables

We adjusted for the following baseline variables: age, sex, a proxy for socioeconomic status and the year prior to enrolment; ≥2 PD-specific medications, PD-specific complications (defined as a unweighted composite of orthopaedic injuries and pneumonia), hospital-related costs, use of mental healthcare, use of medication for depression, long-term care related cost and year of follow-up start55. Socioeconomic status (SES) is operationalized using area characteristics, income, education, and employment status of persons in each neighbourhood using postal code area, in the Netherlands56.

The Vektis database does not include any clinical measures of PD severity or comorbidity. Therefore we used several proxies based on the claims data for disease severity and comorbidities in the year before enrolment as markers for health status. Usage of PD medication and cost-of-illness is closely linked to disease severity and Quality of Life (QoL)32. We defined a binary variable of having or not having ≥2 PD-specific medication as a higher number of PD-specific medications area marker for greater disease severity57,58. In line with previous studies, we defined a PD-related complication as having a hospital visit or admission because of one or more of the following events: sustaining a fracture, sustaining other orthopaedic injuries, or pneumonia27,31. We assume that a higher occurrence of complications is a marker of greater disease severity59. Hospital and long term care cost form the main cost drivers of care in the Netherlands60. We used hospital and long term care costs (Euros) as an indicator for general health status. Mental healthcare use was used as a marker for common other co-morbidities of PD such as cognitive decline, dementia and hallucinations61. We used the Pharmaceutical Cost Group code (FKG) of depression as a marker for depression. FKG are codes in the Netherlands healthcare claims data system, which assign to a chronic condition and are used to predict future healthcare costs based on assumed disease severity62. We also adjusted for year of enrolment to account for a possible difference in follow-up time between both groups.

Ethical considerations

This study was done in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and article 23 of the Dutch personal protection act (section 23.2). No ethical approval or informed consent was obtained because of the observational, retrospective nature of the study using routinely collected data. As part of the standard health insurance policy, all patients included in the claims database had agreed to their data being used anonymously for analyses.

Baseline comparison

We calculated mean and standard deviation values of baseline characteristics and health care use during follow-up for PD-related physiotherapy, stratified by level of expertise of physiotherapy received.

Primary analyses

In the main model, we used a Cox regression model to compare rates of mortality between persons with PD treated by specialised or usual care with adjustment for potential confounders. In the primary analysis, this was restricted to physiotherapy for PD-related indications. In secondary analyses, we repeated the analyses for physiotherapy for any indication and -separately- for non-PD related indications. We included the year of follow up start as an covariate to adjust for secular trends in mortality and delivery of ParkinsonNet.

Adjustment for covariables

All analyses were adjusted for age, SES, comorbidity, sex, ≥2 PD-specific medications, occurrence of PD-specific complications, total hospital costs, use of mental healthcare, use of depression medication, long term care costs in the year prior to enrolment, and the year of follow-up start.

Stratified subgroup analyses

To determine if there were subgroup differences in the association between specialised physiotherapy and mortality, we repeated the main model with adjustment for potential confounders in strata defined by age group, sex, SES, less than or ≥2 PD-specific medications, prevalence of PD-specific complication, total hospital cost (euro), use of mental healthcare, use of depression medication, total long term care related cost (Euros). Continuous variables were usually dichotomized at the median.

Sensitivity analyses

We performed several sensitivity analyses. (i) We looked at different dose response associations by altering the threshold for classifying physiotherapy as specialised. (ii) We determined whether the association between specialised physiotherapy and mortality was time-dependent, by restricting the main model by median follow-up time, (<3.85 and ≥3.85 years) and the time intervals 2010–2014 and 2015–2019 because ParkinsonNet-physiotherapy was gradually scaled up over the study period24. For this analysis, we reassigned patients to either specialized physiotherapy or usual care based on the proportion of therapy sessions delivered by a specialised therapist within each time interval. (iii) We additionally adjusted the main model for various influences during follow up time. We estimated whether the association between specialized physiotherapy and mortality attenuated after adjustment for complications, to explore whether the prevention of complications was a potential mediator. We also estimated whether the association of physiotherapy with mortality attenuated after adjustment for other allied health therapy, since ParkinsonNet is a network approach of care, by adjusting for the number of other specialist visited. To take into account possible regional effects and proximity of care we adjusted for urbanicity on a scale of 1–5 (ranging from 1 which is urban with ≥2500 addresses km² to 5 which is rural with ≤500 addresses per km²) based on information of Statistics Netherlands (CBS)63. We looked at the type of hospital (independent treatment center, general hospital, top clinical hospital or university medical center) in which persons with PD received the majority of care based on costs. In a top clinical hospital the involvement of movement disorders specialists is presumably the greatest. (iv) We did additional sensitivity analysis to test for the possibility of “immortal time bias”. This might occur if persons with PD received specialised physiotherapy later than usual care physiotherapy in their natural history and hence any deaths would only be recorded in the usual care group and for persons with PD who do not die, the person years at risk for usual care would be under-estimated, artefactually increasing its mortality rate. We operationalized this by reallocating the person-time prior to specialised physiotherapy to the usual care arm, for individuals who first received usual care physiotherapy. We subsequently repeated the main analysis using a time-varying Cox proportional hazards model, in which the level of expertise of the physiotherapy received could vary. (v) We also excluded persons with PD with a low number of physiotherapy sessions (e.g. <10; <50 sessions), persons with PD with low cost for Neurology visits for PD during follow up time (e.g. <500 euro; <3840 euro) and by allocation of the level of expertise (specialised or usual care) of the physiotherapist who provided the first physiotherapy session after PD diagnosis.

Adjustment for covariables

All analyses were adjusted for age, SES, comorbidity, sex, ≥2 PD-specific medications, occurrence of PD-specific complications, total hospital costs, use of mental healthcare, use of depression medication, long term care costs in the year prior to enrolment. We used untransformed values for continuous variables which were normally distributed (age, socioeconomic) and dichotomized values for continuous variables which were not normally distributed (total hospital costs and total long stay care act cost).

Data availability

The data utilized in this study is sourced from Vektis and provided under mandate 6-401 to Radboudumc. Due to the specific terms of this mandate, the data is not available for access or distribution to other parties.

References

Bloem, B. R., Okun, M. S. & Klein, C. Parkinson’s disease. Lancet 397, 2284–2303 (2021).

Rong, S. et al. Trends in mortality from Parkinson disease in the United States, 1999–2019. Neurology 97, e1986–e1993 (2021).

Deaths from Parkinson disease have surged. AJN Am. J. Nurs. 122, 15 (2022).

Lampropoulos, I. C. et al. Worldwide trends in mortality related to Parkinson’s disease in the period of 1994–2019: Analysis of vital registration data from the WHO Mortality Database. Front. Neurol. 13, 956440 (2022).

Dorsey, E. R. & Bloem, B. R. The Parkinson pandemic—a call to action. JAMA Neurol. 75, 9–10 (2018).

Limousin, P. & Foltynie, T. Long-term outcomes of deep brain stimulation in Parkinson disease. Nat. Rev. Neurol. 15, 234–242 (2019).

Honig, H. et al. Intrajejunal levodopa infusion in Parkinson’s disease: a pilot multicenter study of effects on nonmotor symptoms and quality of life. Mov. Disord. Off. J. Mov. Disord. Soc. 24, 1468–1474 (2009).

Schapira, A. et al. Levodopa in the treatment of Parkinson’s disease. Eur. J. Neurol. 16, 982–989 (2009).

Osborne, J. A. et al. Physical therapist management of Parkinson disease: a clinical practice guideline from the American Physical Therapy Association (vol 102, pzab302, 2022). Phys. Therapy Rehabilit. J. 102, pzab302 (2022).

Domingos, J. et al. The European physiotherapy guideline for Parkinson’s disease: implications for neurologists. J. Parkinsons Dis. 8, 499–502 (2018).

Radder, D. L. et al. Physiotherapy in Parkinson’s disease: a meta-analysis of present treatment modalities. Neurorehabilit. Neural Repair 34, 871–880 (2020).

Tomlinson, C. L. et al. Physiotherapy versus placebo or no intervention in Parkinson’s disease. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 11, CD002817 (2013).

Nonnekes, J. et al. Compensation strategies for gait impairments in Parkinson disease: a review. JAMA Neurol. 76, 718–725 (2019).

Mirelman, A. et al. Addition of a non-immersive virtual reality component to treadmill training to reduce fall risk in older adults (V-TIME): a randomised controlled trial. Lancet 388, 1170–1182 (2016).

Strouwen, C. et al. Training dual tasks together or apart in Parkinson’s disease: results from the DUALITY trial. Mov. Disord. 32, 1201–1210 (2017).

Schenkman, M. et al. Effect of high-intensity treadmill exercise on motor symptoms in patients with de novo Parkinson disease: a phase 2 randomized clinical trial. JAMA Neurol. 75, 219–226 (2018).

Van der Kolk, N. M. et al. Effectiveness of home-based and remotely supervised aerobic exercise in Parkinson’s disease: a double-blind, randomised controlled trial. Lancet Neurol. 18, 998–1008 (2019).

Walton, C. C. et al. Cognitive training for freezing of gait in Parkinson’s disease: a randomized controlled trial. npj Parkinsons Dis. 4, 15 (2018).

Ramig, L. et al. Speech treatment in Parkinson’s disease: Randomized controlled trial (RCT). Mov. Disord. 33, 1777–1791 (2018).

Sturkenboom, I. H. et al. Efficacy of occupational therapy for patients with Parkinson’s disease: a randomised controlled trial. Lancet Neurol. 13, 557–566 (2014).

Au, K. L. K. et al. A randomized clinical trial of burst vs. spaced physical therapy for Parkinsons disease. Parkinsonism Relat. Disord. 97, 57–62 (2022).

Luft, H. S., Bunker, J. P. & Enthoven, A. C. Should operations be regionalized? The empirical relation between surgical volume and mortality. N. Engl. J. Med. 301, 1364–1369 (1979).

Bloem, B. R. et al. ParkinsonNet: a low-cost health care innovation with a systems approach from the Netherlands. Health Aff. 36, 1987–1996 (2017).

Bloem, B. R. et al. From trials to clinical practice: Temporal trends in the coverage of specialized allied health services for Parkinson’s disease. Eur. J. Neurol. 28, 775–782 (2021).

Rompen, L. et al. Introduction of network-based healthcare at Kaiser Permanente. J. Parkinson’s Dis. 10, 207–212 (2020).

Gray, B. H., Sarnak, D. O. & Tanke, M. ParkinsonNet: an innovative Dutch approach to patient-centered care for a degenerative disease (Commonwealth Fund New York, 2016).

Ypinga, J. H. et al. Effectiveness and costs of specialised physiotherapy given via ParkinsonNet: a retrospective analysis of medical claims data. Lancet Neurol. 17, 153–161 (2018).

Akbar, U. et al. Prognostic predictors relevant to end-of-life palliative care in Parkinson’s disease and related disorders: a systematic review. J. Neurol. Neurosurg. Psychiatry 92, 629–636 (2021).

Hughes, T. et al. Mortality in Parkinson’s disease and its association with dementia and depression. Acta Neurol. Scand. 110, 118–123 (2004).

de Boer, A. G. et al. Predictors of health care use in patients with Parkinson’s disease: a longitudinal study. Mov. Disord. 14, 772–779 (1999).

Talebi, A. H. et al. Specialized versus generic allied health therapy and the risk of Parkinson’s disease complications. Mov. Disord. 38, 223–231 (2023).

Keränen, T. et al. Economic burden and quality of life impairment increase with severity of PD. Parkinsonism Relat. Disord. 9, 163–168 (2003).

Farley, J. F., Harley, C. R. & Devine, J. W. A comparison of comorbidity measurements to predict healthcare expenditures. Am. J. Managed Care 12, 110–118 (2006).

Bloem, B. R. et al. Using medical claims analyses to understand interventions for Parkinson patients. J. Parkinsons Dis. 8, 45–58 (2018).

Maas, B. R. et al. Time trends in demographic characteristics of participants and outcome measures in Parkinson’s disease research: a 19-year single-center experience. Clin. Parkinsonism Relat. Disord. 8, 100185 (2023).

Wammes, J. et al. The Dutch health care system. In International profiles of health care systems, 137 (The Commonwealth Fund 2020).

Pinter, B. et al. Mortality in Parkinson’s disease: a 38-year follow-up study. Mov. Disord. 30, 266–269 (2015).

Dommershuijsen, L. J. et al. The elephant in the room: critical reflections on mortality rates among individuals with Parkinson’s disease. npj Parkinson’s Dis. 9, 145 (2023).

Hobson, P. & Meara, J. Mortality and quality of death certification in a cohort of patients with Parkinson’s disease and matched controls in North Wales, UK at 18 years: a community-based cohort study. BMJ Open 8, e018969 (2018).

Pressley, J. C. et al. Disparities in the recording of Parkinson’s disease on death certificates. Mov. Disord. 20, 315–321 (2005).

Nam, J. S. et al. Hip fracture in patients with Parkinson’s disease and related mortality: a population-based study in Korea. Gerontology 67, 544–553 (2021).

Ypinga, J. H. et al. Rationale and design to evaluate the PRIME Parkinson care model: a prospective observational evaluation of proactive, integrated and patient-centred Parkinson care in The Netherlands (PRIME-NL). BMC Neurol. 21, 1–11 (2021).

Lithander, F. E. et al. Proactive and Integrated Management and Empowerment in Parkinson’s Disease protocol for a randomised controlled trial (PRIME-UK) to evaluate a new model of care. Trials 24, 147 (2023).

Maas, B. R. et al. The PRIME-NL study: evaluating a complex healthcare intervention for people with Parkinson’s disease in a dynamic environment. BMC Neurol. 24, 269 (2024).

Weerkamp, N. J. et al. Parkinson disease in long term care facilities: a review of the literature. J. Am. Med. Dir. Assoc. 15, 90–94 (2014).

de Boo, A. Vektis’ Informatiecentrum voor de zorg. Tijdschr. voor gezondheidswetenschappen 89, 358–359 (2011).

Faust, I. M., Racette, B. A. & Searles Nielsen, S. Validation of a Parkinson disease predictive model in a population-based study. Parkinsons Dis. 2020, 2857608 (2020).

Noyes, K. et al. Accuracy of Medicare claims data in identifying Parkinsonism cases: comparison with the Medicare current beneficiary survey. Mov. Disord. 22, 509–514 (2007).

Baldacci, F. et al. Reliability of administrative data for the identification of Parkinson’s disease cohorts. Neurological Sci. 36, 783–786 (2015).

Nijkrake, M. J. et al. The ParkinsonNet concept: development, implementation and initial experience. Mov. Disord. 25, 823–829 (2010).

Nijkrake, M. J. et al. Allied health care in Parkinson’s disease: referral, consultation, and professional expertise. Mov. Disord. 24, 282–286 (2009).

Keus, S. H. et al. The ParkinsonNet trial: design and baseline characteristics. Mov. Disord. 25, 830–837 (2010).

RvIG. About RvIG. Available from: https://www.rvig.nl/service/about-rvig (2015).

RvIG. Personal Records Database (BRP). Available from: https://www.government.nl/topics/personal-data/personal-records-database-brp (2025).

Van Den Eeden, S. K. et al. Incidence of Parkinson’s disease: variation by age, gender, and race/ethnicity. Am. J. Epidemiol. 157, 1015–1022 (2003).

de Boer, W. I. et al. Neighborhood socioeconomic status and health care costs: a population-wide study in the Netherlands. Am. J. Public Health 109, 927–933 (2019).

Möller, J. et al. Pharmacotherapy of Parkinson’s disease in Germany. J. Neurol. 252, 926–935 (2005).

Dahodwala, N. et al. Use of a medication-based algorithm to identify advanced Parkinson’s disease in administrative claims data: associations with claims-based indicators of disease severity. Clin. Parkinsonism Relat. Disord. 3, 100046 (2020).

Pressley, J. The impact of comorbid disease and injuries on resource use and expenditures in parkinsonism-Reply. Neurology 61, 1023–1024 (2003).

Vektis. Factsheet 15 jaar Zorgverzekeringswet. Available from: https://www.vektis.nl/intelligence/publicaties/factsheet-15-jaar-zorgverzekeringswet (2021).

Schrag, A., Ben-Shlomo, Y. & Quinn, N. How common are complications of Parkinson’s disease?. J. Neurol. 249, 419–423 (2002).

Lamers, L. M. & van Vliet, R. C. The Pharmacy-based Cost Group model: validating and adjusting the classification of medications for chronic conditions to the Dutch situation. Health Policy 68, 113–121 (2004).

CBS, S. N. Data by postal code. Available from: https://www.cbs.nl/nl-nl/dossier/nederland-regionaal/geografische-data/gegevens-per-postcode (2025).

Acknowledgements

The authors thank Vektis for providing access to the healthcare claims data and their continuing collaboration with our research group. JHLY would like to thank CZ Group and all colleagues for the opportunity and support to conduct this research.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

J.H.L.Y., L.H.H.M.B., S.K.L.D. and N.M.d.V. developed the study concept. J.H.L.Y., L.H.H.M.B., S.K.L.D. and N.M.d.V. drafted the manuscript. J.H.L.Y., S.K.L.D. were responsible for data acquisition. J.H.L.Y., L.H.H.M.B., Y.B.S., S.K.L.D. and N.M.d.V. were responsible for statistical analysis and validation. J.H.L.Y., L.H.H.M.B., Y.B.S., S.K.L.D. and N.M.d.V. created the tables and figures. All authors were involved in reviewing and editing the manuscript. All authors have approved the final version.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

L.H.H.M.B. and P.P.T.J. have no financial disclosures to report. The Centre of Expertise for Parkinson and Movement Disorders was supported by a grant from the Parkinson Foundation. The contributions by B.R.B., S.K.L.D., J.H.L.Y., and M.M. are part of the collaborative Proactive and Integrated Management and Empowerment in Parkinson’s Disease (PRIME) project, which is financed by the Gatsby Foundation (GAT3676) and Dutch Ministry of Economic Affairs by means of the PPP Allowance made available by the Top Sector Life Sciences & Health to stimulate public–private partnerships. The Gatsby Foundation and the Top Sector Life Sciences & Health have a seat in the advisory board of the PRIME Parkinson project but played no role in the design of the study, analysis, and interpretation of data and in writing of the manuscript. N.M.d.V. reports grants from The Netherlands Organisation for Health Research and Development (ZonMw) and The Michael J Fox Foundation. B.R.B. currently serves as Editor in Chief for Journal of Parkinson’s disease; serves on the editorial board of Practical Neurology and Digital Biomarkers; has received honoraria from serving on the scientific advisory board for AbbVie, Biogen, and UCB; has received fees for speaking at conferences from AbbVie, Zambon, Roche, GE Healthcare, and Bial; and has received research support from the Netherlands Organization for Scientific Research, The Michael J. Fox Foundation, UCB, AbbVie, the Stichting Parkinson Fonds, the Hersenstichting Nederland, the Parkinson’s Foundation, Verily Life Sciences, Horizon 2020, the Topsector Life Sciences and Health, the Gatsby Foundation, and the Parkinson Vereniging. Y.B.S. has received research support from the UK Medical Research Council, Wellcome Trust, NIHR, Parkinson’s UK, Versus Arthritis, Gatsby Foundation, and Dunhill Trust, and is a recipient of a Radboud Excellence award. S.K.L.D. has received funding from the Parkinson’s Foundation (PF-FBS-2026), ZonMW (09150162010183), ParkinsonNL (P2022-07 and P2021-14), Michael J Fox Foundation (MJFF-022767) and Edmond J Safra Foundation.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Ypinga, J.H.L., Boonen, L.H., Munneke, M. et al. Effects of specialised physiotherapy on mortality in Parkinson’s disease: a prospective observational study. npj Parkinsons Dis. 11, 214 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41531-025-01069-x

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41531-025-01069-x