Abstract

Zonisamide exhibits potential neuroprotective properties, but its efficacy during the prodromal stage of Lewy body disease (LBD) remains unclear. In this phase II randomized, double-blind pilot trial, 29 high-risk individuals aged 50–80 years with ≥2 prodromal symptoms and abnormal DaT-SPECT and/or cardiac MIBG were randomized to zonisamide (50–100 mg/day, n = 14) or placebo (n = 15) and treated for 96 weeks. Participants with Parkinson’s disease or dementia with Lewy bodies were excluded. No significant between-group difference was observed in the primary outcome, change in DaT-SPECT specific binding ratio from baseline to week 96 (0.072; 95% CI −0.565 to 0.709; p = 0.817), or in secondary outcomes including MIBG parameters and motor and cognitive functions. Non-motor symptoms worsened with zonisamide, whereas two placebo recipients developed Parkinson’s disease. Somnolence, fatigue, decreased appetite, and constipation were frequent adverse events. Although findings are inconclusive due to limited power, this study provides valuable methodological insights for preventive LBD trials.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Disease-modifying therapies remain to be established for Lewy body disease (LBD), which encompasses Parkinson’s disease (PD) and dementia with Lewy bodies (DLB). Clinical trials of disease-modifying therapies for patients with LBD have reported negative results, indicating the requirement for initiating therapeutic intervention during the prodromal phase1. The prodromal phase of LBD is characterized by non-motor symptoms such as constipation, rapid eye movement (REM) sleep behavior disorder (RBD), and hyposmia, which emerge 10–20 years before the clinical onset of LBD2

The Nagoya-Takayama preclinical/prodromal Lewy body disease (NaT-PROBE) study is a prospective, longitudinal, multi-center, community-based cohort study. Notably, 5.7% of healthy individuals aged >50 years in the NaT-PROBE exhibited at least two of the following prodromal symptoms: dysautonomia, RBD, and hyposmia. This population was defined as individuals at high risk for LBD3. Abnormalities in dopamine transporter (DaT) single-photon-emission computed tomography (SPECT) or cardiac metaiodobenzylguanidine (MIBG) scintigraphy were observed in approximately one-third of high-risk individuals4. Furthermore, the plasma neurofilament light chain (NfL) levels of these individuals were higher than those of low-risk individuals without prodromal symptoms 5.

Zonisamide has exhibited efficacy in improving motor symptoms and reducing off-time in patients with PD6,7. Similarly, it has ameliorated parkinsonism in patients with DLB8. Consequently, it has received approval for use in the management of both conditions in Japan. In addition to these symptomatic effects, zonisamide has also demonstrated multiple mechanisms potentially relevant to neuroprotection in cellular and animal studies such as modulation of dopamine turnover, induction of neurotrophic factor expression, inhibition of oxidative stress and apoptosis, inhibition of neuroinflammation, modulation of synaptic transmission, and modulation of gene expression9. A retrospective study of early PD showed that zonisamide co-treatment attenuated the decline in DaT-SPECT specific binding ratio (SBR) and reduced the progression of wearing-off and dyskinesia10, supporting its potential disease-modifying role.

Therefore, this study (NaT-PROBEi trial) evaluated the efficacy and safety of zonisamide in individuals at high risk of developing LBD with abnormalities in DaT-SPECT and/or cardiac MIBG scintigraphy. The present study is one of the first trials targeting the prodromal phase of LBD.

Results

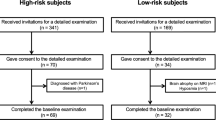

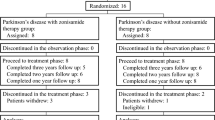

Participant flow

Among the 36 participants screened for eligibility between February 2021 and August 2021 (Fig. 1), six with normal DaT-SPECT and cardiac MIBG scintigraphy findings were excluded. Thus, 30 participants were randomly allocated to receive zonisamide and placebo at a 1:1 ratio. Five participants in the zonisamide group discontinued the study drug owing to death from aortic dissection (n = 1), development of adverse events (exacerbation of glaucoma [n = 1] and fatigue, decreased appetite, insomnia, and anxiety [n = 1]), and withdrawal of consent at their own request (n = 2). One participant in the placebo group discontinued the study drug at their own request. All participants who discontinued the study drug, except for the deceased participant, provided additional consent for continued follow-up evaluations. Thus, the full analysis set (FAS) comprised 14 and 15 participants in the zonisamide and placebo groups, respectively, with DaT-SPECT data at baseline and at least one follow-up assessment. No participants received dopaminergic medication at baseline or during the study.

Baseline characteristics

The participants were randomly assigned to either of the two groups using a minimization method with age at the time of providing consent and baseline DaT-SPECT SBR as the allocation factors. No significant differences were observed between the groups in terms of the demographic and baseline characteristics (Table 1). The prevalence of abnormal cardiac MIBG scintigraphy findings was higher than that of abnormal DaT-SPECT findings in both groups. A slightly higher population of participants with DaT-SPECT abnormalities was allocated to the placebo group, whereas MIBG abnormalities were similarly distributed across groups.

Primary outcome

No significant differences were observed between the two groups in terms of the change in DaT-SPECT SBR from baseline to week 96 (Table 2, Fig. 2a)

The changes in the adjusted average of DaT-SPECT SBR (a), MIBG H/M ratio delay (b), MDS-UPDRS III (c), MoCA-J (d), MDS-UPDRS I (e), BDI-II (f), PDQ-39 summary index (g), and plasma NfL levels (h) from the baseline to week 96 are plotted with 95% confidence interval. Mixed-effects models for repeated measures (MMRM) are used to determine the adjusted average and p-values visualized with **p < 0.01, *p < 0.05. DaT dopamine transporter, MIBG metaiodobenzylguanidine, MDS-UPDRS Movement Disorder Society-Unified Parkinson’s Disease Rating Scale, MoCA-J the Japanese version of the Montreal Cognitive Assessment, BDI-II Beck Depression Inventory-Second Edition, PDQ-39 Parkinson’s Disease Questionnaire-39, NfL neurofilament light chain.

Secondary outcomes

No significant differences were observed between the two groups in terms of the changes in the cardiac MIBG scintigraphy parameters, Movement Disorder Society-Unified Parkinson’s Disease Rating Scale (MDS-UPDRS) III, or the Japanese version of the Montreal Cognitive Assessment (MoCA-J) from baseline to week 96 (Table 2, Fig. 2b–d). However, compared with that observed among the participants in the placebo group, the worsening of the MDS-UPDRS I, the Beck Depression Inventory-Second Edition (BDI-II), and Parkinson’s Disease Questionnaire-39 (PDQ-39) summary index was significantly greater among the participants in the zonisamide group (Table 2, Fig. 2e–g). The plasma NfL levels exhibited a trend toward greater increase in the zonisamide group; however, this difference was not statistically significant at week 96 (Table 2, Fig. 2h). Two participants in the placebo group developed PD during the double-blind period; no participants in the zonisamide group experienced phenoconversion. This difference in conversion rates was not statistically significant (Table 2).

Ancillary analyses

The per-protocol set (PPS) comprised seven and 12 participants in the zonisamide and placebo groups, respectively. Analysis of the FAS revealed that medication adherence in the zonisamide group (64.6 [38.7]%) was lower than that in the placebo group (88.0 [21.9]%). However, analysis of the PPS revealed high and comparable adherence rates between the zonisamide (98.9 [1.6]%) and placebo (98.2 [1.7]%) groups. Moreover, the baseline Physical Activity for Scale for the Elderly (PASE) scores in the zonisamide group were significantly higher, indicating greater physical activity. The plasma NfL levels in the zonisamide group were higher; however, the difference was not significant. The remaining baseline characteristics were comparable between the groups (Supplementary Table 1). The primary outcome analysis in the PPS yielded results consistent with those of the FAS analysis, indicating no significant inter-group differences in terms of DaT-SPECT SBR change (Supplementary Table 2). Significant worsening of MDS-UPDRS I was observed in the zonisamide group compared with that in the placebo group, consistent with the results of the FAS analysis. The pareidolia test revealed significant worsening in the zonisamide group. The PDQ-39 summary index, BDI-II, and NfL levels also exhibited trends toward greater worsening in the zonisamide group; however, this difference was not statistically significant (Supplementary Table 2). The number of phenoconversions in the PPS was identical to that observed in the FAS.

Ten participants in the zonisamide group completed the administration of the study drug, whereas four discontinued the administration of the study drug. The baseline Epworth Sleepiness Scale (ESS) scores of the participants in the discontinuation group were significantly higher, indicating greater daytime sleepiness (Supplementary Table 3). Significantly greater worsening in MDS-UPDRS I and PDQ-39 summary index was observed in the participants who discontinued zonisamide compared with that in those who did not (Supplementary Table 4).

Stratification of the zonisamide group according to the baseline ESS median scores (≥5 vs. <5) revealed that the 96-week change in the pareidolia test was better in the participants with stronger baseline sleepiness; however, the coefficient of variation of R-R intervals (CVRR) results over the 96-week period of these participants were worse (Supplementary Table 5).

One participant in the zonisamide group, who developed gastrointestinal stromal tumor (GIST) was transferred to the intensive care unit (ICU) during the double-blind period, indicating an outlier value in the plasma NfL levels. Sensitivity analysis excluding this outlier reduced the inter-group difference in NfL changes (Supplementary Table 6, Supplementary Fig. 1).

Safety

All participants experienced at least one adverse event (15 [100%] participants each; 65 and 115 events in the zonisamide and placebo groups, respectively; p > 0.999). The incidence of serious adverse events was more frequent in the zonisamide group (five participants [33.3%], five events) compared with that in the placebo group (none; p = 0.042). Kidney stones and glaucoma exacerbation were possibly related to zonisamide, while colon polyp, GIST, and aortic dissection were deemed unrelated. Treatment-related adverse events were observed in eight (53.3%) and seven (46.7%) participants in the zonisamide and placebo groups, respectively (p > 0.999). Somnolence, fatigue, decreased appetite, and constipation were the most frequently reported adverse events, with somnolence being particularly common (Table 3).

Discussion

This phase II trial did not demonstrate a significant effect of zonisamide on preventing the decline in DaT-SPECT SBR over 96 weeks among individuals at high risk of developing LBD. No significant differences were observed between the two groups in terms of the changes in cardiac MIBG scintigraphy parameters or motor and cognitive functions. Significant worsening of non-motor symptoms, particularly MDS-UPDRS I, BDI-II, and PDQ-39 summary index, was observed in the zonisamide group. Treatment-related adverse events such as fatigue, decreased appetite, constipation, especially somnolence, which was the most frequently experienced adverse event, were reported. Notably, two participants in the placebo group developed PD during the double-blind period, whereas none of the participants in the zonisamide group developed PD. However, this difference was not statistically significant.

DaT-SPECT SBR exhibited a decline of −1.01 (0.72) over 48 weeks in our unpublished preliminary study of eight high-risk individuals. Consequently, a larger decline was expected over 96 weeks. However, the actual decline observed in this trial was much smaller (approximately −0.3). This discrepancy may be attributed to the characteristics of the study population, which chiefly comprised participants with MIBG abnormalities rather than DaT-SPECT deficits. Individuals without DaT-SPECT deficits (defined as ≤65% of age-expected lowest putamen binding ratio) exhibited minimal changes in DaT binding over time compared with those observed in individuals with deficits exhibiting a decline of approximately 5% annually in a previous study11. Accordingly, the slightly higher proportion of participants with baseline DaT-SPECT abnormalities in the placebo group may have influenced the results. The findings of the present study are in contrast with those of a retrospective observational cohort study of patients with PD, which reported that zonisamide significantly attenuated the decline in DaT-SPECT SBR (−0.04 vs −0.46) over one year10. This difference might reflect variations between established PD and prodromal phases in terms of treatment response or suggest that the intervention timing was premature to detect potential effects in this study population wherein the DaT-SPECT changes are still minimal.

Somnolence, fatigue, decreased appetite, and constipation were the most common treatment-related adverse events. Kidney stones and exacerbation of glaucoma were two serious adverse events possibly related to zonisamide observed herein. The adverse event profile of zonisamide was consistent with those reported by previous trials of patients with PD and DLB6,7,8,12. The administration of 100 mg and 50 mg of zonisamide to patients with PD and DLB, respectively, showed significantly higher adverse event rates compared with those of lower doses or placebo6,12. Baseline sleepiness, as measured by ESS, was associated with treatment discontinuation in the present study, suggesting that individuals with prominent daytime sleepiness may be poor candidates for zonisamide treatment.

Significant worsening in non-motor symptoms, particularly in MDS-UPDRS I, BDI-II, and PDQ-39 summary index, was observed in the zonisamide group. Notably, this deterioration was more pronounced in participants who discontinued treatment. Thus, adverse effects may have contributed to symptom worsening and reduced quality of life. The plasma NfL levels exhibited a trend toward a greater increase in the zonisamide group; however, this trend was reduced when the outlier was excluded.

Two and zero participants in the placebo and zonisamide groups, respectively, developed PD during the double-blind period; however, this difference was not statistically significant. Combinations of prodromal features strongly predict PD development, with males presenting with constipation, probable RBD, and hyposmia exhibiting a 23-fold higher risk over three years13. Furthermore, the combination of hyposmia and reduced DaT binding strongly predicts conversion to PD within four years11. Thus, the 96-week double-blind period may have been insufficient to detect significant differences in phenoconversion rates, given the inclusion criteria of the presence of ≥2 prodromal symptoms + DaT-SPECT or MIBG abnormalities. Nevertheless, the absence of phenoconversion in the zonisamide group might reflect a partial symptomatic rather than disease-modifying effect. Zonisamide weakly inhibits monoamine oxidase B and enhances dopaminergic transmission9, which could improve mild motor symptoms and delay clinical diagnosis without necessarily altering the underlying neurodegenerative process. The participants are being followed up to evaluate the long-term outcomes.

This study provides several insights into the design of studies targeting the prodromal phase of LBD. First, the decline in DaT-SPECT SBR may not follow a linear trajectory during the prodromal phase but rather a nonlinear, possibly sigmoid pattern, with an accelerated decrease around the time of phenoconversion14,15. In the present study, participants were enrolled based on decreased uptake in MIBG and/or DaT-SPECT. This design might have reduced the statistical power, as longitudinal changes in SBR are likely to be small among individuals with preserved DaT uptake. Therefore, comprehensive information on the natural history of DaT-SPECT and modeling of prodromal SBR deterioration are essential for the rational design of clinical trials in high-risk individuals. Second, DaT-SPECT SBR exhibits considerable measurement variability, which makes it challenging to detect clinically meaningful changes in small samples and may limit its utility as a primary endpoint. Improving quantitative analysis methods for DaT-SPECT and developing alternative biomarkers that more directly reflect dopaminergic neuron degeneration will be crucial for enhancing trial design. Finally, future preventive or early-intervention trials should employ high-precision prognostic models integrating natural history of biofluid and imaging biomarkers, thereby enabling accurate participant stratification and enrichment.

Certain limitations of this study must be noted. The study assumed a 50% reduction in DaT-SPECT SBR decline, but the modest changes observed fell below the distribution-based thresholds estimated from our data (standard error of the mean, 0.23), suggesting limited statistical power to detect clinically meaningful effects. Furthermore, higher rates of study drug discontinuation and poor medication adherence than expected were observed, which could be attributed to adverse events such as somnolence and the unique challenges of conducting clinical trials in prodromal populations. Most participants who discontinued the study drug continued follow-up evaluations; nevertheless, the number of participants in the PPS was limited owing to low adherence. The 96-week double-blind period may have been insufficient for evaluating the changes in the prodromal phase. Furthermore, the high-risk criteria were formulated based on questionnaires and imaging findings; thus, the natural history and conversion rates in this population remain unclear. Individual variability in imaging biomarkers may have also affected the ability to detect treatment effects. Lastly, transcriptomic differences may have influenced treatment response, as previously reported in patients with PD 16.

Thus, this phase II trial did not demonstrate definitive disease-modifying effects of zonisamide in individuals at high risk of developing LBD and revealed safety concerns, particularly somnolence and non-motor symptom worsening. Future studies should explore different dosing regimens of zonisamide to identify the optimal balance between efficacy and tolerability. Given the limited sample size and power, these findings should be regarded as inconclusive but informative for future research. They highlight key requirements for future prodromal LBD trials, including careful patient selection, longer observation periods, and more sensitive surrogate markers. As one of the first therapeutic studies targeting the prodromal phase of LBD, this trial provides valuable guidance for the design of future disease-modifying therapy studies in neurodegenerative disorders.

Methods

Study design

This phase II, multicenter, randomized (1:1), double-blind, placebo-controlled, parallel-group trial (NaT-PROBEi) conducted across five centers in Japan (Nagoya University Hospital, National Center for Geriatrics and Gerontology, Nagoya City University Hospital, Kumiai Kosei Hospital, and Chutoen General Medical Center) evaluated the efficacy and safety of zonisamide in individuals at high risk of developing LBD. The double-blind treatment period spanned from February 2021 to June 2023. The primary outcome measure was the change in DaT-SPECT SBR from baseline to week 96. A 144-week drug-free observational period, which primarily aimed to monitor for conversion of LBD to PD or DLB, was commenced following the 96-week double-blind treatment period. This study adhered to the Declaration of Helsinki, the Ethical Guidelines for Medical and Health Research Involving Human Subjects, and the Clinical Trials Act by the Japanese government. The trial protocol was approved by the Certified Review Board of Nagoya University Graduate School of Medicine (approval number: 2019-0498, CRB4180004) and registered with the Japan Registry of Clinical Trials (jRCTs041190126). Written informed consent was obtained from all participants before screening. This article reports the results of the 96-week double-blind treatment period; the complete study protocol is available in the Supplementary Material.

Participants

Individuals aged 50–80 years who satisfied the high-risk criteria for LBD, modified from previous studies, were eligible for inclusion3,4,5. In brief, in addition to the presence of abnormalities in DaT-SPECT (defined as an age-adjusted Z-score below the normal range in DaTView analysis)17 or cardiac MIBG scintigraphy (indicated by early or delayed heart-to-mediastinum [H/M] ratio of <2.2)18 the participants satisfied the criteria for at least two of the following prodromal symptoms: dysautonomia, a Japanese version of the Scale for Outcomes in Parkinson’s disease for Autonomic Symptoms (SCOPA-AUT) score of ≥10; hyposmia, a Self-administered Odor Question (SAOQ) score of ≤90% or an Odor Stick Identification Test for Japanese (OSIT-J) score of ≤7; and RBD, an RBD screening scale (RBDSQ) score of ≥5 or polysomnography-confirmed REM sleep without atonia (RWA). These inclusion criteria allowing either DaT-SPECT or MIBG abnormalities were designed to reflect the biological heterogeneity of prodromal LBD, as previous studies suggested that disease progression may follow diverse rather than uniform trajectories 19,20.

The key exclusion criteria included: use of zonisamide ≤4 weeks before screening; hypersensitivity to zonisamide or its ingredients; concomitant use of strong CYP3A inhibitors; diagnosis of PD, DLB, or psychiatric disorders other than depression; severe cardiac, hepatic, or renal disease; pregnant or lactating women; and abnormal findings on magnetic resonance images of the brain suggestive of dementia or other neurological disorders.

Treatment

Oral zonisamide (Sumitomo Pharma Co., Ltd., Japan) or matching placebo was administered to the participants for 96 weeks. The initial dose was 50 mg administered once daily for 4 weeks, followed by 100 mg administered once daily for 92 weeks. The approved doses for PD and DLB in Japan are 25–50 mg and 25 mg, respectively. However, the dosage expected to exert neuroprotective effects ranges from 25 to 300 mg/day10,21,22,23,24,25,26,27,28,29,30,31. The administration of higher doses resulted in increased adverse events in patients with PD and DLB in previous clinical trials6,12. Therefore, 100 mg was selected as the target dose to balance potential efficacy and safety. Dose reduction was permitted in the event of Grade 2 or higher adverse events according to the Common Terminology Criteria for Adverse Events (CTCAE), with stepwise reduction to 75 mg, 50 mg, and 25 mg being performed daily as required. Dose reduction was permitted for somnolence at the discretion of the investigator, even for Grade 1 events if they affected daily activities.

Clinical assessments

The participants were evaluated at baseline, weeks 4, 8, 12, and every 12 weeks thereafter. MDS-UPDRS, performed by certified evaluators, as well as cognitive function tests including MoCA-J, Stroop test, trail making test, line orientation test, and pareidolia test. DaT-SPECT imaging with (123I)FP-CIT, cardiac (123I)MIBG scintigraphy, olfactory testing (OSIT-J), autonomic function assessment using CVRR (resting and deep breathing) were conducted every 48 weeks. In addition, the following questionnaires were administered every 48 weeks: PASE, SCOPA-AUT (Japanese version), SAOQ, RBDSQ, BDI-II, ESS, PDQ-39, and Questionnaire for Impulsive-Compulsive Disorders in Parkinson’s Disease (QUIP). DaT-SPECT and cardiac MIBG scintigraphy were performed as described previously4. All aforementioned questionnaires were validated for self-administration in the Japanese population32,33,34,35,36,37,38,39. Adverse events were assessed according to CTCAE at each visit. The Common Adverse Events Reporting Guideline in the Japanese Cancer Trial Network, with events categorized as having a definite, probable, or possible causal relationship to the study drug, was used to define treatment-related adverse events.

DaT-SPECT analysis

DaT-SPECT image acquisition was performed at baseline, weeks 48 and 96 (or at early termination). The images were initially analyzed by trained image analysts at Micron, Inc., a contract research organization, using DaTView software (Nihon Medi-Physics Co., Ltd., Japan). The analysts were blinded to treatment allocation and visit timing. Phantom experiments were conducted at each participating center before commencing the trial to ensure the reliability and robustness of the SBR measurements.

An independent central review committee, comprising an experienced nuclear medicine physician not affiliated with any of the trial sites, evaluated the appropriateness of the results of the primary analysis. The SPECT images, region of interest (ROI) placement, and SBR calculations were reviewed by the committee member. Re-analysis was conducted in accordance with the DaTView analysis protocol by Micron or the committee member if modifications were deemed necessary by the committee member.

Discontinuation and follow-up

The administration of the study drug was discontinued in the event of the following adverse events that prevented continued participation: new onset of PD, DLB, or multiple system atrophy; major protocol violations; loss to follow-up; withdrawal of consent; early study termination; or other circumstances deemed necessary by the investigators. Additional consent for continued follow-up evaluations was obtained from the participants who discontinued participation during the double-blind period. All assessments conducted during the follow-up period were identical to those conducted during the treatment phase.

Outcomes

The change in DaT-SPECT SBR from baseline to week 96 was the primary outcome measure. The secondary outcome measures were the changes in cardiac sympathetic denervation (MIBG H/M ratio), MDS-UPDRS I-III, cognitive function (MoCA-J, Stroop test, trail making test, line orientation test, and pareidolia test), olfactory function (OSIT-J), physical activity (PASE), autonomic symptoms (SCOPA-AUT), smell awareness (SAOQ), RBD symptoms (RBDSQ), depression (BDI-II), daytime sleepiness (ESS), quality of life (PDQ-39), impulse control (QUIP), plasma NfL levels, and phenoconversion rate to PD or DLB. Phenoconversion was defined as satisfying the Movement Disorder Society Clinical Diagnostic Criteria for PD40 or the diagnostic criteria of the fourth report of the DLB consortium 41.

Sample size

Preliminary data revealed a 48-week DaT-SPECT SBR change of -1.01 (standard deviation 0.72) in untreated high-risk individuals. Therefore, the change at 96 weeks was estimated to be approximately twice this magnitude. Eleven participants per group were required to detect this difference (α = 0.05, β = 0.10), assuming a 50% reduction in the change with zonisamide treatment and common standard deviation. Thirty participants (15 per group) were to be enrolled considering the dropout rate.

Randomization and blinding

An independent allocation manager at the Department of Advanced Medical Research, Nagoya University Hospital, generated the random allocation sequence. The investigators at each trial site enrolled the participants. The participants were allocated to receive interventions using a minimization method with age at the time of providing consent and baseline DaT-SPECT SBR as allocation factors. All participants, investigators, outcome assessors, and imaging analysts were blinded to treatment allocation. The study drugs were prepared in identical containers with sequential numbering to ensure allocation concealment. The zonisamide and placebo tablets were identical in appearance, size, color, and packaging. The allocation manager ensured that the appearance and packaging of the study drugs were indistinguishable. Emergency unblinding, which required obtaining approval from the principal investigator and allocation manager, was permitted only when necessary for participant safety. The allocation code, stored in sealed emergency keys, was concealed until database lock.

Statistical methods

Analyses were conducted on the FAS, which comprised randomized participants with DaT-SPECT SBR at baseline and ≥1 post-treatment assessment who received at least one dose of the study drug. Safety analyses were conducted on the safety analysis set, which comprised all randomized participants who received at least one dose of the study drug. Sensitivity analyses were conducted on a PPS, excluding participants with a medication adherence rate of <75% or major protocol violations. Post-hoc analyses included comparison between the study drug completion and discontinuation groups, and subsequent analyses stratified according to the baseline ESS scores. Post-hoc analyses were exploratory and not prespecified in the statistical analysis plan.

A mixed-effects model for repeated measures (MMRM) was used to compare the changes in DaT-SPECT SBR between the groups in the primary analysis. The treatment group, visit, treatment-by-visit interaction, and baseline values were set as the fixed effects. An unstructured covariance matrix was used initially. Alternative structures such as Toeplitz, heterogeneous compound symmetry, first-order autoregressive, compound symmetry, and variance components were tested sequentially if convergence failed. The variance and covariance parameters were determined using restricted maximum likelihood estimation. The degrees of freedom were computed using the Kenward-Roger method.

The secondary continuous outcomes were analyzed using MMRM in a similar manner. Fisher’s exact test was used to compare the proportions. Inter-group differences in the baseline characteristics in the post-hoc analyses were determined using Student’s t test or Mann–Whitney U-test for continuous variables and Fisher’s exact test for categorical variables. All statistical tests were two-sided, with a significance level of 5%. The MMRM approach, which assumes data are missing at random, was used to handle missing data. All PPS analyses were conducted using the same statistical methods used in FAS analyses. All statistical analyses were conducted using SAS version 9.3 or higher (SAS Institute, Cary, NC). Figures were generated using R version 4.2.0 (R Foundation for Statistical Computing, Vienna, Austria) with the ggplot2 package.

Data availability

The data used to support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request, which includes the specification of a clear research question and confirmation of the approval from the Ethics Review Committee of Nagoya University Graduate School of Medicine.

References

Mahlknecht, P., Marini, K., Werkmann, M., Poewe, W. & Seppi, K. Prodromal Parkinson’s disease: hype or hope for disease-modification trials?. Transl. Neurodegener. 11, 11 (2022).

Kalia, L. V. & Lang, A. E. Parkinson’s disease. Lancet 386, 896–912 (2015).

Hattori, M. et al. Subjects at risk of Parkinson’s disease in health checkup examinees: cross-sectional analysis of baseline data of the NaT-PROBE study. J. Neurol. 267, 1516–1526 (2020).

Hattori, M. et al. Clinico-imaging features of subjects at risk of Lewy body disease in NaT-PROBE baseline analysis. NPJ Parkinsons Dis. 9, 67 (2023).

Hiraga, K. et al. Plasma biomarkers of neurodegeneration in patients and high risk subjects with Lewy body disease. NPJ Parkinsons Dis. 10, 135 (2024).

Murata, M., Hasegawa, K. & Kanazawa, I. Zonisamide on PD Study Group. Zonisamide improves motor function inParkinson disease: a randomized, double-blind study. Neurology 68, 45–50 (2007).

Murata, M. et al. Zonisamide improves wearing-off in Parkinson’s disease: a randomized, double-blind study: Zonisamide Improves Wearing-Off. Mov. Disord. 30, 1343–1350 (2015).

Murata, M. et al. Effect of zonisamide on parkinsonism in patients with dementia with Lewy bodies: a phase 3 randomized clinical trial. Parkinsonism Relat. Disord. 76, 91–97 (2020).

Li, C. et al. Zonisamide for the treatment of Parkinson disease: a current update. Front. Neurosci. 14, 574652 (2020).

Ikeda, K. et al. Zonisamide cotreatment delays striatal dopamine transporter reduction in Parkinson disease: a retrospective, observational cohort study. J. Neurol. Sci. 391, 5–9 (2018).

Jennings, D. et al. Conversion to Parkinson disease in the PARS hyposmic and dopamine transporter-deficit prodromal cohort. JAMA Neurol. 74, 933–940 (2017).

Murata, M. et al. Adjunct zonisamide to levodopa for DLB parkinsonism: a randomized double-blind phase 2 study. Neurology 90, e664–e672 (2018).

Flores-Torres, M. H. Identifying individuals in the prodromal phase of Parkinson's disease: a prospective cohort study. Ann. Neurol. 97, 720–729 (2024).

Berg, D., Marek, K., Ross, G. W. & Poewe, W. Defining at-risk populations for Parkinson’s disease: lessons from ongoing studies. Mov. Disord. 27, 656–665 (2012).

Kordower, J. H. et al. Disease duration and the integrity of the nigrostriatal system in Parkinson’s disease. Brain 136, 2419–2431 (2013).

Naito, T. et al. Comparative whole transcriptome analysis of Parkinson’s disease focusing on the efficacy of zonisamide. J. Neurol. Neurosurg. Psychiatry 93, 509–512 (2022).

Matsuda, H. et al. Japanese multicenter database of healthy controls for [123I]FP-CIT SPECT. Eur. J. Nucl. Med. Mol. Imaging 45, 1405–1416 (2018).

Nakajima, K. & Nakata, T. Cardiac 123I-MIBG imaging for clinical decision making: 22-year experience in Japan. J. Nucl. Med. 56, 11S–19S (2015).

Horsager, J. et al. Brain-first versus body-first Parkinsonas disease: a multimodal imaging case-control study. Brain 143, 3077–3088 (2020).

Totsune, T. et al. Nuclear imaging data-driven classification of Parkinson’s disease. Mov. Disord. 38, 2053–2063 (2023).

Sano, H., Murata, M. & Nambu, A. Zonisamide reduces nigrostriatal dopaminergic neurodegeneration in a mouse genetic model of Parkinson’s disease. J. Neurochem. 134, 371–381 (2015).

Sano, H. & Nambu, A. The effects of zonisamide on L-DOPA-induced dyskinesia in Parkinson’s disease model mice. Neurochem. Int. 124, 171–180 (2019).

Yokoyama, H. et al. Therapeutic effect of a novel anti-parkinsonian agent zonisamide against MPTP (1-methyl-4-phenyl-1,2,3,6- tetrahydropyridine) neurotoxicity in mice. Metab. Brain Dis. 25, 305–313 (2010).

Arawaka, S. et al. Zonisamide attenuates α-synuclein neurotoxicity by an aggregation-independent mechanism in a rat model of familial Parkinson’s disease. PLoS ONE 9, e89076 (2014).

Asanuma, M. et al. Neuroprotective effects of zonisamide target astrocyte. Ann. Neurol. 67, 239–249 (2010).

Choudhury, M. E. et al. Zonisamide up-regulated the mRNAs encoding astrocytic anti-oxidative and neurotrophic factors. Eur. J. Pharmacol. 689, 72–80 (2012).

Kawajiri, S., Machida, Y., Saiki, S., Sato, S. & Hattori, N. Zonisamide reduces cell death in SH-SY5Y cells via an anti-apoptotic effect and by upregulating MnSOD. Neurosci. Lett. 481, 88–91 (2010).

Tsujii, S., Ishisaka, M., Shimazawa, M., Hashizume, T. & Hara, H. Zonisamide suppresses endoplasmic reticulum stress-induced neuronal cell damage in vitro and in vivo. Eur. J. Pharmacol. 746, 301–307 (2015).

Omura, T. et al. HRD1 levels increased by zonisamide prevented cell death and caspase-3 activation caused by endoplasmic reticulum stress in SH-SY5Y cells. J. Mol. Neurosci. 46, 527–535 (2012).

Costa, C. et al. Electrophysiological actions of zonisamide on striatal neurons: selective neuroprotection against complex I mitochondrial dysfunction. Exp. Neurol. 221, 217–224 (2010).

Condello, S. et al. Protective effects of zonisamide against rotenone-induced neurotoxicity. Neurochem. Res. 38, 2631–2639 (2013).

Hagiwara, A., Ito, N., Sawai, K. & Kazuma, K. Validity and reliability of the Physical Activity Scale for the Elderly (PASE) in Japanese elderly people. Geriatr. Gerontol. Int. 8, 143–151 (2008).

Matsushima, M., Yabe, I., Hirotani, M., Kano, T. & Sasaki, H. Reliability of the Japanese version of the scales for outcomes in Parkinson’s disease-autonomic questionnaire. Clin. Neurol. Neurosurg. 124, 182–184 (2014).

Takebayashi, H. et al. Clinical availability of a self-administered odor questionnaire for patients with olfactory disorders. Auris Nasus Larynx 38, 65–72 (2011).

Miyamoto, T. et al. The REM sleep behavior disorder screening questionnaire: validation study of a Japanese version. Sleep. Med. 10, 1151–1154 (2009).

Kojima, M. et al. Cross-cultural validation of the Beck Depression Inventory-II in Japan. Psychiatry Res. 110, 291–299 (2002).

Takegami, M. et al. Development of a Japanese version of the Epworth Sleepiness Scale (JESS) based on item response theory. Sleep. Med. 10, 556–565 (2009).

Kohmoto, J., et al. Validation of the Japanese version of the Parkinson’s disease questionnaire. Rinsho Shinkeigaku 43, 71–76 (2003).

Tanaka, K., Wada-Isoe, K., Nakashita, S., Yamamoto, M. & Nakashima, K. Impulsive compulsive behaviors in Japanese Parkinson’s disease patients and utility of the Japanese version of the Questionnaire for Impulsive-Compulsive Disorders in Parkinson’s disease. J. Neurol. Sci. 331, 76–80 (2013).

Postuma, R. B. et al. MDS clinical diagnostic criteria for Parkinson’s disease. Mov. Disord. 30, 1591–1601 (2015).

McKeith, I. G. et al. Diagnosis and management of dementia with Lewy bodies: Fourth consensus report of the DLB Consortium. Neurology 89, 88–100 (2017).

Acknowledgements

Study drugs were provided by Sumitomo Pharma Co., Ltd. This study was supported by AMED under Grant Numbers JP20lk0201124 and JP19lk0201101; the Research Funding for Longevity Sciences (Nos. 19-20, 22-26, and 25-7) from the National Center for Geriatrics and Gerontology (NCGG), Japan; and Creating training hubs for advanced medical personnel (Supporting the fostering of doctors with advanced clinical and research capabilities) from Ministry of Education, Culture, Sports, Science and Technology (MEXT), Japan. The funder played no role in study design, data collection, analysis and interpretation of data, or the writing of this manuscript.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

K.H. contributed to study design and concept, manuscript drafting/revision, data analysis/interpretation, data acquisition, research project execution, and statistical analysis. M.H. contributed to study design and concept, data acquisition, research project execution. D.T., Y.Sat., and T.F. contributed to data acquisition and research project execution. Y.Sai., T.U., and T.T. contributed to research project execution. M.S., K.Y., K.S., Y.A., Y.U. contributed to data acquisition and research project execution. F.K. contributed to statistical analysis. H.M. contributed to DaT-SPECT analysis. A.M. contributed to DaT-SPECT analysis protocol. M.Y., M.W., N.M., and Y.W. contributed to data acquisition and research project execution. M.K. contributed to study design and concept, research project execution, data analysis/interpretation, and manuscript revision (intellectual content). All authors critically evaluated the manuscript, and approved the final version of manuscript to be submitted.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

M.K. receives research grants from Sumitomo Pharma and Nihon Medi-physics. The remaining authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Hiraga, K., Hattori, M., Tamakoshi, D. et al. Phase II pilot randomized trial of zonisamide for disease modification in prodromal Lewy body disease. npj Parkinsons Dis. 11, 322 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41531-025-01198-3

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41531-025-01198-3