Abstract

In models of Parkinson’s disease (PD), angiotensin-II type-1 receptor (AT1) blockers (ARBs) mitigated the vulnerability of dopaminergic neurons, which aligns with recent transcriptomic studies of human brains showing increased susceptibility of dopaminergic neurons with high AGTR1 expression, and with epidemiological data indicating an ARB-related reduction in PD incidence. However, there is no experimental evidence in PD patients. Using a minimally invasive strategy based on the isolation of blood extracellular vesicles (EVs) from neuronal, microglial/macrophage, astrocytic, and oligodendrocytic origin, we report proteomic profiles from patients treated with the ARB candesartan. Candesartan treatment led to the differential expression of key proteins involved in PD pathogenesis: 46 in neuron-derived EVs, 48 in microglia/macrophage-derived EVs, 22 in astrocyte-derived EVs, and 92 in oligodendrocyte-derived EVs. Our findings provide the first direct molecular evidence of neuroprotective mechanisms triggered by ARBs in PD patients and support the rationale for larger clinical trials on ARB repurposing.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

A series of studies in animal and vitro models have shown that activation of angiotensin type-1 (AT1) receptors increased the vulnerability of dopaminergic neurons, which was inhibited by AT1 receptor blockers (ARBs), and that ARBs that were able to cross the blood-brain barrier (BBB), such as candesartan or telmisartan, were particularly effective in animal models1,2. Candesartan is an effective AT1 antagonist in crossing the blood-brain barrier, and low doses have little effect on blood pressure and inhibit brain angiotensin effects by blocking AT1 receptors3,4. In Parkinson’s disease (PD) models, activation of AT1 receptors exacerbated major mechanisms involved in dopaminergic neuron degeneration and PD progression, which was inhibited by ARB treatment5,6,7. Recent studies in humans are consistent with the results in experimental models. Using single-nucleus RNA sequencing and unbiased clustering analysis, Kamath et al.8 showed that the most vulnerable population of nigral dopaminergic neurons expressed the highest rate of the AT1 receptor gene (AGTR1), which was confirmed by several additional studies9,10. Furthermore, recent retrospective cohort studies showed that ARB treatment was associated with a marked reduction of PD risk in hypertensive patients, and that ARBs with BBB-penetrating properties and a high cumulative duration of treatment were particularly effective11,12. We have recently performed a randomized phase-II 28-week clinical trial of candesartan to explore the effects on cognitive impairment (CI) in PD patients13. Results showed that candesartan treatment was safe and well-tolerated and revealed improvement in apathy, a highly debilitating non-motor symptom experienced by PD patients14. However, to our knowledge, in vivo molecular brain changes induced by the administration of candesartan remain unexplored in PD patients. Interestingly, the neuroprotective effects of ARBs have also been suggested for Alzheimer’s disease15,16. On this basis, several recent studies underscore the urgency of initiating clinical trials on drug repurposing with ARBs17,18,19. However, there is currently no experimental evidence of their neuroprotective effects in PD patients to support the initiation of such trials, which is provided by the present study.

Small Extracellular vesicles (EVs) can cross the BBB and, owing to their biogenesis, their molecular cargo reflects the physiological state of their origin cell20,21. These properties position EVs as a powerful tool for investigating central nervous system (CNS) processes through peripheral biofluids. In the present study, we isolated EVs from neurons, astrocytes, oligodendrocytes, and microglia/macrophage cell origin in blood samples from randomly selected PD patients of the above-mentioned clinical trial, before and after the candesartan treatment, which were then subjected to proteomic analysis to identify molecular effects induced by candesartan in the patient brain. We observed remarkable effects of candesartan on proteins and cellular processes involved in dopaminergic degeneration and PD progression. Notably, this minimally invasive approach enabled the characterization of CNS cell–type–specific molecular changes induced by the administration of ARBs such as candesartan, potentially constituting a paradigm shift in the investigation and clinical monitoring of neurodegenerative disorders.

Results

Patient characteristics

Our clinical study13 was focused on cognitive impairment and revealed a significant positive effect on apathy, which is considered an early behavioral predictor of cognitive decline. The effect of candesartan on other parameters was more variable. Among the patients subjected to the present proteomic study, 3 of 5 patients improved UPDRS III scale after 6-month candesartan treatment (Supplementary Table 1). However, in the motor section of the UPDRS III scale, a change of 5 points is generally considered the minimal clinically relevant difference22. Overall, we can state that there was no clinically significant post-treatment improvement in motor scales. This result is consistent with the nature of neuroprotection trials, whose primary aim is to prevent deterioration rather than to produce improvement. However, relying on the expected longitudinal increase in UPDRS III scores would not be appropriate, as this parameter varies considerably according to Parkinson’s disease subtype, disease duration, and treatment regimen. We hypothesize that the clinical beneficial effects may have been limited by the relatively short duration of the study and the heterogeneity of the PD sample.

Regarding emotional outcomes, the HADS (Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale) was administered before and after treatment. Although two patients exhibited post-treatment improvements in depression and anxiety scores (Supplementary Table 2), these findings should be interpreted with caution, as none of the patients had baseline scores meeting the threshold for clinical significance (≥8 in either subscale).

None of the patients presented significant cardiovascular conditions at the time of study enrollment, and treatment-related blood pressure changes did not result in any significant effect or adverse effects leading to treatment discontinuation. Systolic and diastolic blood pressure values, both in the supine and standing positions, before and after treatment, are shown in Supplementary Table 3.

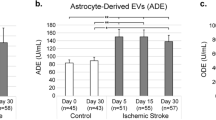

Characterization of the obtained extracellular vesicles

Nanoparticle tracking analysis (NTA; Fig. 1A, B) confirmed the presence of extracellular vesicles (EVs) with mean diameters of 115.6 ± 1.97 nm (SEM) before candesartan treatment and 119.2 ± 2.35 nm (SEM) after treatment. A paired t-test revealed no statistically significant differences in vesicle size between conditions. Similarly, EV concentrations did not differ significantly before and after candesartan administration (3.764 × 10¹² particles/mL ± 2.62 × 10¹¹ vs. 3.598 × 10¹² particles/mL ± 2.88 × 10¹¹). Transmission electron microscopy (TEM) confirmed the presence of vesicles displaying typical round morphology and nanometric size (Fig. 1C). To evaluate EV protein content, canonical EV markers were first analyzed in three pre- and three post-treatment samples. As no concentration differences were observed, samples were pooled for subsequent characterization. Total EV (EVT) preparations showed enrichment of canonical EV markers, including the tetraspanins CD81 and CD63 and the cytosolic protein Alix, involved in ESCRT-mediated biogenesis (Fig. 1D–F). Calnexin, an endoplasmic reticulum marker absent from bona fide EVs, was undetectable in EVT fractions and only present in the positive control (HMC3 cell lysate), supporting the purity of the EV isolation protocol (Fig. 1G). To verify the central nervous system (CNS) origin of the vesicles, quantitative ELISA was performed using cell-type-specific protein markers for four EV subtypes. Neuron-derived EVs (nEVs) were identified by the presence of neuron-specific enolase (NSE; Fig. 1H). Astrocyte-derived EVs (aEVs) were marked by glial fibrillary acidic protein (GFAP; Fig. 1I), oligodendrocyte-derived EVs (oEVs) by myelin basic protein (MBP; Fig. 1J), and microglia/macrophage-derived EVs (m/mEVs) by ionized calcium-binding adapter molecule 1 (IBA-1; Fig. 1K). Concentrations of each marker were compared across three pre- and three post-treatment samples using t-tests, revealing no significant differences. Data were therefore pooled to demonstrate marker enrichment following immunocapture. All four EV subtypes exhibited significantly higher marker levels in the enriched fractions compared to whole serum and EV-depleted samples. Furthermore, ENOLASE, GFAP, MBP, and IBA-1 showed robust enrichment in nEVs, aEVs, oEVs, and m/mEVs, respectively. In contrast, their levels were negligible in non-corresponding EV subtypes, supporting the subtype-specific expression of these markers (Supplementary Fig. 1), which confirms the successful isolation and characterization of neuronal, astrocytic, oligodendrocytic, and microglial/macrophage-derived EVs. Full statistical details are provided in Supplementary Data Fig. 1.

A, B Nanoparticle tracking analysis (NTA) showing size distribution and particle concentration of total EVs before and after candesartan treatment in each patient. C Transmission electron microscopy (TEM) image of a representative EV, confirming typical vesicular morphology (scale bar = 100 nm). D–F Quantification of canonical EV markers CD81, CD63, and Alix by ELISA, demonstrating EV enrichment compared to EV-depleted serum fractions. G Calnexin levels were used as a negative control to assess the absence of cellular contamination. An extract from the human microglial cell line HMC3 (ATCC® CRL-3304) was employed as a positive control. H–K Quantification of neuronal (Enolase), astrocytic (Glial Fibrillary Acidic Protein; GFAP), oligodendrocytic (Myelin Basic Protein; MBP), and microglial (Ionized calcium-binding adapter molecule 1; IBA-1) markers in serum, total extracellular vesicles (EVT), and in extracellular vesicles (EVs) isolated from distinct brain cell types confirmed the presence of CNS–derived EVs. Data are presented as mean ± SEM. *P < 0.05 vs. EV-depleted (D-G) or serum (H-K); #P < 0.05 vs. EVT.

Dysregulated proteins of isolated EVs are associated with brain tissue

A quantitative analysis was performed using the SWATH-MS method to compare the protein expression profiles of patients before and after treatment. This study identified 1,141 proteins, 10,416 peptides, and 95,129 spectra, with an FDR < 1%. Over these proteins, 874 were quantified. The most dysregulated proteins were identified based on a log fold change (FC) ≥ 0.6 or ≤ −0.7 and p < 0.05, with a more stringent threshold of p < 0.01 applied to highlight the most significantly dysregulated proteins. STRING analysis confirmed that most quantified proteins are associated with brain tissue, supporting the CNS origin of the EVs. Protein enrichment patterns (Fig. 2A, B) further emphasized neurological relevance. Subtype-specific EV proteomes (nEVs, aEVs, oEVs, m/mEVs) were also compared across treatment conditions.

A Protein-protein interaction (PPI) network of the identified proteins generated using STRING. Each node (circle) represents a protein, and edges (lines) indicate known or predicted interactions. Red bubbles indicate tissue expression in the brain, blue bubbles represent expression in brain cell lines, green bubbles denote expression in the brainstem, and yellow bubbles correspond to expression in the brain ventricles. Edge colors indicate interaction types: blue for co-occurrence across species, green for functional associations based on text mining, purple for experimentally validated interactions, and yellow for database-derived interactions. The network reveals multiple interconnected protein clusters, suggesting functional modules and highlighting potential key regulatory proteins involved in neurological and cellular processes. B Gene set enrichment analysis of the identified proteins. The y-axis lists enriched biological pathways, including Brain cell line, Brain, Brainstem, and Brain ventricle, while the x-axis represents statistical significance thresholds. The color gradient indicates the false discovery rate (FDR), with lighter green representing highly significant pathways (FDR < 1.0e-120) and darker blue indicating less significant pathways (FDR ~ 1.0e-03). The bubble size corresponds to the number of genes associated with each pathway, with larger bubbles indicating pathways with a higher number of identified proteins. Among the most enriched pathways, Brain and Brain cell line exhibit large bubble sizes and low FDR values, suggesting a strong statistical association. These findings indicate a predominant involvement of brain-related pathways in the analyzed dataset.

Candesartan-induced protein changes in EVs enriched by neuronal origin

In the first analysis (post vs. pre-candesartan treatment) in nEVs, 46 dysregulated proteins were identified, of which 19 were upregulated, and 27 were downregulated (Supplementary Table 4). The volcano plot analysis of nEVs (Fig. 3A) shows the main upregulated proteins (p < 0.05; log2FC > 1). An in-depth analysis of the dataset reveals that PARK7/DJ-1, TCPZ, RL21, CAYP, FUS, and H1X were upregulated with p < 0.01, all of which are linked to key cellular recovery mechanisms as detailed in UniProt (https://www.uniprot.org) and the Human Protein Atlas (https://www.proteinatlas.org). Interestingly, PARK7/DJ-1 reflects the activation of antioxidant and mitochondrial protective pathways. PARK7 acts as an antioxidant protein, a sensor of mitochondrial stress, and a regulator of proteostasis23. Mutations in this gene cause autosomal recessive forms of Parkinson’s disease, highlighting its essential role in neuronal defense24. Functionally, DJ-1 mitigates ROS accumulation, preserves mitochondrial integrity, and modulates autophagy and protein quality control mechanisms. Therefore, the observed elevation in PARK7 expression likely represents a therapeutically beneficial adaptive response, enhancing the antioxidant capacity, mitochondrial stability, and overall neuronal resilience in PD. TCPZ supports proteostasis through the proper folding of cytoskeletal proteins. TCPZ, a ζ-subunit of the CCT/TRiC chaperonin complex, promotes the proper folding of cytoskeletal and aggregation-prone proteins. The CCT/TRiC complex inhibits α-synuclein aggregation, including the pathogenic A53T mutant25; thus, higher TCPZ expression is consistent with protective activation of chaperone mechanisms. Other upregulated proteins are also involved in neuronal protective mechanisms. Upregulation of RL21 indicates increased protein synthesis, while CAYP1 suggests restored intracellular transport. FUS is involved in RNA metabolism, DNA repair, and synaptic maintenance. H1X may reflect chromatin remodeling in response to treatment.

A Volcano plot showing the differential protein expression analysis of nEVs post-CAND vs. nEVs pre-CAND. The x-axis represents the log₂ fold change, indicating the magnitude of upregulation (right) or downregulation (left), while the y-axis displays the −log₁₀(p value), reflecting statistical significance. Upregulated genes (red) and downregulated genes (green) meet the significance threshold, while non-significant genes (gray) remain unchanged. B Heatmap representing the expression levels of differentially expressed proteins in nEVs after candesartan treatment. The x-axis corresponds to individual patients, with the first five samples representing the pre-treatment condition and the last five the post-treatment condition. The y-axis lists the proteins that exhibit significant changes in expression. The color scale indicates relative protein abundance, with blue representing downregulation, red representing upregulation, and white denoting intermediate expression levels. C Protein-protein interaction network generated using the STRING database, illustrating functional associations among key dysregulated proteins. Line colors represent different types of functional associations. D Gene Ontology (GO) pathway enrichment analysis. The bubble plot illustrates significantly enriched molecular functions. The Y-axis lists the enriched GO categories, while the X-axis represents the signal strength, indicating the enrichment level of each category. Bubble size corresponds to the number of genes associated with each category, and the background color reflects the False Discovery Rate (FDR), where lighter shades indicate higher statistical significance. Larger bubbles denote a greater number of associated proteins. This analysis highlights key molecular functions affected in the study and their statistical relevance.

In parallel, several proteins were significantly downregulated (p < 0.01), including HS90B, DEST, PLCD1, LANC1, NRCAM, PUR2, LV39, and AMPL. Reduced HSP90B1 (GRP94/gp96), a major ER-resident chaperone upregulated during ER stress and UPR activation, indicates less endoplasmic reticulum stress in the parent neurons and therefore a diminution of stress-signal export via EVs26. Downregulation of the ADF/Cofilin pathway, which includes Destrin (DEST), reflects the completion of axonal and synaptic remodeling processes. The ADF/Cofilin system promotes α-synuclein pathogenicity and spreading, and its overactivation exacerbates Parkinsonian phenotypes27. Therefore, reduced ADF/Cofilin activity could be beneficial, consistent with a shift toward cytoskeletal stabilization and diminished α-synuclein propagation. LANC1, a glutathione transferase, was downregulated, suggesting diminished proteotoxic and oxidative stress. Lower levels of PLCD1 suggest the stabilization of cytoskeletal architecture and calcium signaling. NRCAM downregulation may reflect the completion of axonal remodeling, while reduced PUR2 expression implies the normalization of purine metabolism. The decrease in AMPL, a Zn²⁺-dependent metallopeptidase involved in glutathione S-conjugate degradation and redox regulation, further supports reduced oxidative stress. Finally, lower LV39 levels may indicate decreased immune activation. Altogether, this proteomic profile suggests a coordinated neuroprotective response, involving improved redox and mitochondrial function, enhanced proteostasis and gene regulation, and attenuation of synaptic, metabolic, and inflammatory stress pathways, highlighting the therapeutic potential of the intervention in PD.

Clustering protein expression patterns is visualized in the heatmap (Fig. 3B), illustrating distinct protein expression profiles in nEVs after treatment. Notably, P02652 (APOA2) and Q99497 (PARK7/DJ-1) were upregulated after candesartan treatment, suggesting the activation of neuroprotective pathways. APOA2 may contribute to membrane stabilization, while PARK7/DJ-1 supports mitochondrial function and redox homeostasis. Conversely, Q08211 (DHX9), P26639 (SYTC), and P17844 (DDX5) were downregulated after candesartan treatment, possibly reflecting reduced transcriptional stress and improved proteostasis. These proteins are involved in RNA metabolism and translation, and their decreased expression may indicate a normalization of neuronal homeostasis. The consistency of these alterations across individuals supports a reproducible and systemic therapeutic effect on the nEV proteome in PD.

The protein-protein interaction network generated using STRING (Fig. 3C) highlights key functional associations of all significantly dysregulated proteins (up- and downregulated). Central nodes include HSP90AB1, HSPA5, and VCP, which are involved in protein homeostasis, and PARK7/DJ-1, which interacts with genes involved in ribosomal proteins (RPL35A, RPL21) and chaperones, linking translational regulation to protein quality control. The presence of PSMA6 (proteasomal subunit) and RNA-binding proteins (FUS, DHX9, DDX5) suggests a connection between protein degradation and post-transcriptional regulation. Notably, PARK7/DJ-1 and RAB3A indicate a role in vesicular trafficking. The strong connectivity of HSPA5 and HSP90 underscores the relevance of proteotoxic stress, while PARK7/DJ-1 emerges as a key regulator and potential biomarker in these processes.

Gene ontology (GO) molecular function enrichment analysis (Fig. 3D) identified four main functional categories associated with dysregulated proteins: (i) Protein Folding and Cellular Stress Response, which includes chaperones and heat shock proteins essential for maintaining protein quality control; (ii) Cell Adhesion and Protein-Protein Interaction, crucial for intercellular communication and structural organization; (iii) Enzymatic Regulation and Energy Metabolism, encompassing ATP-dependent enzymatic activities relevant to biochemical transformations and nucleotide metabolism; and (iv) Nucleic Acid and Ion Binding, regulating gene expression, post-transcriptional processes, and calcium-dependent signaling.

Detailed tree maps of the upregulated and downregulated pathways in nEVs after candesartan treatment, along with their interpretation, are shown in Supplementary Material: Supplementary Results and Supplementary Figs. 2 and 3.

Candesartan-induced protein changes in EVs enriched by astrocytic origin

Analysis of aEV proteomic cargo showed 22 dysregulated proteins, of which 10 were upregulated, and 12 were downregulated after candesartan treatment (Supplementary Table 5). The volcano plot analysis of aEVs (Fig. 4A) identified the principal dysregulated proteins (p < 0.05; log2FC > 1). Among the upregulated proteins (p < 0.01), PSB4, LSAMP, PHLD, and SYFB stood out for their roles in cellular maintenance and neuroprotection as detailed in UniProt (https://www.uniprot.org) and the Human Protein Atlas (https://www.proteinatlas.org). Upregulation of PSB4, a catalytic subunit of the 20S proteasome, indicates enhanced proteostasis, as the ubiquitin–proteasome system (to which PSB4 belongs) is crucial for degrading misfolded proteins and maintaining protein homeostasis28. LSAMP (limbic system-associated membrane protein), involved in synapse formation and neuronal connectivity, also increased, suggesting activation of synaptic repair and remodeling pathways29. PHLD may promote clearance of toxic GPI-anchored proteins, and SYFB reflects improved mitochondrial function30.

A Volcano plot showing the differential protein expression analysis of aEVs post-CAND vs. aEVs pre-CAND. The x-axis represents the log₂ fold change, indicating the magnitude of upregulation (right) or downregulation (left), while the y-axis displays the −log₁₀(p value), reflecting statistical significance. Upregulated genes (red) and downregulated genes (green) meet the significance threshold, while non-significant genes (gray) remain unchanged. B Heatmap representing the expression levels of differentially expressed proteins in aEVs after candesartan treatment. The x-axis corresponds to individual patients, with the first five samples representing the pre-treatment condition and the last five the post-treatment condition. The y-axis lists the proteins that exhibit significant changes in expression. The color scale indicates relative protein abundance, with blue representing downregulation, red representing upregulation, and white denoting intermediate expression levels. C Protein-protein interaction network generated using the STRING database, illustrating functional associations among key dysregulated proteins. Line colors represent different types of functional associations. D Gene Ontology (GO) pathway enrichment analysis. The bubble plot illustrates significantly enriched molecular functions. The Y-axis lists the enriched GO categories, while the X-axis represents the signal strength, indicating the enrichment level of each category. Bubble size corresponds to the number of genes associated with each category, and the background color reflects the False Discovery Rate (FDR), where lighter shades indicate higher statistical significance. Larger bubbles denote a greater number of associated proteins. This analysis highlights key molecular functions affected in the study an their statistical relevance.

Conversely, stress-related proteins SUMO2, RS26L, and CRNS1 were downregulated (p < 0.01), indicating reduced oxidative and proteotoxic stress, normalized translation, and a more balanced redox state. SUMO2, a modifier that becomes active under oxidative and proteotoxic conditions, conjugates misfolded proteins such as α-synuclein; its downregulation is consistent with attenuated stress responses31. Similarly, reduced RS26L, a 40S ribosomal subunit protein, suggests normalization of translational activity and diminished ribosomal stress32. Finally, decreased CRNS1 (CNDP1), the enzyme that degrades the antioxidant dipeptide carnosine, may indicate preserved antioxidant capacity and mitigation of oxidative damage33. Consistent with this, elevated CRNS1 expression has been linked to increased oxidative and metabolic stress, leading to depletion of carnosine reserves34.These findings suggest that treatment enhances astrocytic support while reducing stress responses, fostering a neuroprotective environment in PD.

The heatmap (Fig. 4B) shows distinct protein expression changes in aEVs pre- and post-treatment, with clustering indicating coordinated regulation. Notably, P31939 (PUR9) and O43301 (HS12A) were significantly downregulated after candesartan treatment, suggesting reduced astrocytic stress and metabolic burden, consistent with a protective effect on the neural environment. In contrast, P28070 (PSB4) and P46778 (RPL21) were upregulated after candesartan treatment, indicating enhanced proteostasis and protein synthesis. These changes suggest a transition to a less reactive, more supportive astrocytic phenotype, potentially contributing to neuroprotection in PD. Their consistency across samples supports a reproducible treatment effect.

The PPI network of significantly dysregulated proteins in aEVs (Fig. 4C) revealed key associations related to proteostasis, metabolism, and neuroinflammation. Upregulation of proteasome (PSMB4, PSMB5, PSMA3) and ribosomal proteins (RPL21, RPL31), along with metabolic regulators (CKB, FARSB), suggests enhanced protein turnover and astrocytic support. Downregulation of stress-related proteins (HSPA12A, SUMO2, ATIC) and immunomodulators (ITIH3) indicates reduced cellular stress and inflammation. These findings support a candesartan-induced shift toward a neuroprotective astrocytic phenotype in PD. The GO biological process analysis (Fig. 4D) identifies “organonitrogen compound metabolic process” which suggests active involvement of astrocytes in the metabolism of nitrogen-containing neurotransmitters, amino acids, and related compounds, reflecting their role in neurotransmitter clearance, glutamine synthesis, and ammonia detoxification, potentially contributing to improved proteostasis, metabolic efficiency, and neuroprotection in the context of PD.

Detailed tree maps of the upregulated and downregulated pathways in aEVs after candesartan treatment, along with their interpretation, are shown in Supplementary Material: Supplementary Results and Supplementary Figs. 4 and 5.

Candesartan-induced protein changes in EVs enriched by oligodendroglia origin

oEV proteomic cargo showed 92 dysregulated proteins, of which 55 were upregulated, and 37 were downregulated after candesartan treatment (Supplementary Table 6). The volcano plot analysis of oEVs revealed significant alterations in their proteomic cargo following candesartan treatment (Fig. 5A), suggesting a neuroprotective effect in PD aimed at enhancing myelin repair, metabolic homeostasis, oxidative stress resistance, immune modulation, and neuronal support, as detailed in UniProt (https://www.uniprot.org) and the Human Protein Atlas (https://www.proteinatlas.org). An increase (p < 0.01; log2FC > 1) in the expression of STXBP1 and L1CAM in oEVs indicates enhanced synaptic and axon–glia communication. Both were previously identified as relevant nodes in PD networks35 and are key regulators of vesicle fusion and cell adhesion. Their increase likely reflects an adaptive response of oligodendrocytes that promotes myelin integrity, metabolic support, and neuronal connectivity under PD-related stress, consistent with evidence that oEVs transfer neuroprotective and remyelinating factors to neurons36. Upregulation of TBCB and DBNL in oEVs suggests enhanced cytoskeletal organization and cellular remodeling, processes associated with oligodendrocyte recovery and myelin repair. TBCB supports microtubule assembly and stability37, which is essential for oligodendrocyte morphology, differentiation, and intracellular transport required for myelin production. DBNL regulates actin remodeling, a critical process for the extension and membrane dynamics of oligodendrocytes during myelination38. An increase in the expression of APOC3, NP1L1, and SORCN supports lipid metabolism, neurogenesis, and calcium homeostasis. PPIA, DHX9, and PCBP1 are involved in RNA processing, protein quality control, and cellular stress responses, supporting proteostasis and reducing toxic aggregate formation. ATP5H and CPSM contribute to mitochondrial function and ammonia detoxification, enhancing metabolic efficiency.

A Volcano plot showing the differential protein expression analysis of oEVs post-CAND vs. oEVs pre-CAND. The x-axis represents the log₂ fold change, indicating the magnitude of upregulation (right) or downregulation (left), while the y-axis displays the −log₁₀(p value), reflecting statistical significance. Upregulated genes (red) and downregulated genes (green) meet the significance threshold, while non-significant genes (gray) remain unchanged. B Heatmap representing the expression levels of differentially expressed proteins in oEVs after candesartan treatment. The x-axis corresponds to individual patients, with the first five samples representing the pre-treatment condition and the last five the post-treatment condition. The y-axis lists the proteins that exhibit significant changes in expression. The color scale indicates relative protein abundance, with blue representing downregulation, red representing upregulation, and white denoting intermediate expression levels. C Protein-protein interaction network generated using the STRING database, illustrating functional associations among key dysregulated proteins. Line colors represent different types of functional associations. D Gene Ontology (GO) pathway enrichment analysis. The bubble plot illustrates significantly enriched molecular functions. The Y-axis lists the enriched GO categories, while the X-axis represents the signal strength, indicating the enrichment level of each category. Bubble size corresponds to the number of genes associated with each category, and the background color reflects the False Discovery Rate (FDR), where lighter shades indicate higher statistical significance. Larger bubbles denote a greater number of associated proteins.

Conversely, the downregulation (p < 0.01; log2FC < −0.7) of KLKB1, a protease activating the kallikrein-kinin system, is consistent with attenuated neuroinflammation and blood–brain barrier disruption39. Decreased expression of CLIC4, a chloride intracellular channel, may indicate clinical improvement in Parkinson’s disease, as CLIC4 upregulation has been linked to neuroinflammatory and demyelinating processes. Reduced levels of oligodendrocyte-derived vesicular CLIC4 likely reflect diminished oligodendrocyte stress and a reestablishment of glial homeostasis, consistent with the restoration of myelin integrity and the attenuation of neuroinflammatory activity40. Lower ENO2 levels in oEVs likely reflect a more stable and mature oligodendroglial state, consistent with improved myelin maintenance and neuronal support41. Dowregulation of AK1A1, a key enzyme for detoxifying reactive aldehydes such as methylglyoxal and acrolein, suggests a lower oxidative burden in treated cells. A decline in CALR, a chaperone involved in ER stress and calcium homeostasis, points to improved proteostasis.

The heatmap analysis of differentially expressed proteins in oEVs after candesartan treatment (Fig. 5B) reveals distinct proteomic shifts indicative of a neuroprotective response. Elevated expression of Q9H4G0 (E41L1) may reflect an effective modulation in neuron-oligodendroglial interaction, while upregulation of P61764 (STXB1) points to potential restoration of synaptic vesicle trafficking and neurotransmission. The presence of P40925 (MDHC) indicates an improvement in metabolic function and redox homeostasis. Conversely, proteins such as P24752 (THIL) and P61981 (1433 G) display downregulation after candesartan treatment, which suggests a reduction in mitochondrial β-oxidation activity and improved mitochondrial protein quality control, respectively. The observed proteomic shifts suggest that the cargo of oEVs reflects the neuroprotective effects of candesartan, primarily through the modulation of neuron-glia communication, the promotion of metabolic homeostasis, and the attenuation of oxidative stress.

STRING-based PPI network analysis of oEVs (Fig. 5C) reveals a highly coordinated molecular adaptation, suggesting a shift toward a neuroprotective status. Distinct functional clusters reflect enhanced mitochondrial activity and metabolism (ATP5PD, ATP5F1B, SLC25A5, VDAC2, ALDH9A1), optimized RNA processing and translation regulation (EIF4G1, RBMX, ELAVL1, PCBP1, FUBP1, RPS12, RPL27A), and reinforcement of synaptic stability and axonal support (MAP1A, SNAP25, STXBP1, TUBA4A, L1CAM, NEFL). The upregulation of oxidative stress regulators (CAT, PPIA, CTSD, LANCL1) and the downregulation of HSP90AA1 suggest reduced neurotoxic stress, while the modulation of immune-related proteins (C1QC, SERPINA5, CAMP, ITIH1, ITIH3, THBS1) indicates a controlled neuroinflammatory response42,43. Central hubs such as HSP90AA1, ATP5F1B, and EIF4G1 highlight the importance of energy balance, proteostasis, and synaptic stability in oligodendrocyte-mediated neuroprotection.

GO biological process analysis (Fig. 5D) identified several major functional categories enriched among the dysregulated proteins in oEVs, including pathways related to structural organization, protein complex assembly, and regulation of metabolic and degradative processes. These biological functions are particularly relevant in PD, as they reflect the glial mechanisms involved in maintaining tissue homeostasis and neural support.

Detailed tree maps of the upregulated and downregulated pathways in oEVs after candesartan treatment, along with their interpretation, are shown in Supplementary Material: Supplementary Results and Supplementary Figs. 6 and 7.

Candesartan-induced protein changes in EVs enriched by microglia/macrophage origin

Analysis of m/mEV proteomic cargo showed 48 dysregulated proteins, of which 23 were upregulated, and 25 were downregulated (Supplementary Table 7). The volcano plot analysis of m/mEVs reveals significant alterations in their proteomic cargo (Fig. 6A), suggesting a neuroprotective response mediated by enhanced immune regulation, metabolic adaptation, oxidative stress resistance, and synaptic support, as detailed in UniProt (https://www.uniprot.org) and the Human Protein Atlas (https://www.proteinatlas.org). The increased expression (p < 0.01; log2FC > 1) of NSF1C, E41L1, PP1R7, RAB14, and SNAP25 after candesartan treatment suggests a shift toward a reparative immune phenotype. An enrichment of NSFL1C (p47) and PPP1R7 (SDS22) in m/mEVs is consistent with a shift toward an anti-inflammatory microglial phenotype and may mechanistically underlie the observed neuroprotective effect. Both proteins act as negative regulators of pro-inflammatory signaling: NSFL1C/p47 binds K63-linked and linear polyubiquitin chains on NEMO (IKKγ), promoting its lysosomal degradation and thereby suppressing IKK/NF-κB activation44. PPP1R7/SDS22, a targeting subunit of protein phosphatase-1 (PP1), directs PP1 toward dephosphorylating AKT/NF-κB nodes, dampening downstream inflammatory transcription45. Higher levels of RAB14 suggest recovery of endosomal–autophagic trafficking, a process increasingly recognized as critical in neurodegeneration and PD-related endolysosomal stress46. The detection of SNAP25 in microglial EVs may indicate enhanced clearance and remodeling of synaptic material, consistent with microglial pruning and synaptic maintenance under disease-associated stress, as previously observed in Alzheimer’s disease47.

A Volcano plot showing the differential protein expression analysis of m/mEVs post-CAND vs. m/mEVs pre-CAND. The x-axis represents the log₂ fold change, indicating the magnitude of upregulation (right) or downregulation (left), while the y-axis displays the −log₁₀(p value), reflecting statistical significance. Upregulated genes (red) and downregulated genes (green) meet the significance threshold, while non-significant genes (gray) remain unchanged. B Heatmap representing the expression levels of differentially expressed proteins in m/mEVs after candesartan treatment. The x-axis corresponds to individual patients, with the first five samples representing the pre-treatment condition and the last five the post-treatment condition. The y-axis lists the proteins that exhibit significant changes in expression. The color scale indicates relative protein abundance, with blue representing downregulation, red representing upregulation, and white denoting intermediate expression levels. C Protein-protein interaction network generated using the STRING database, illustrating functional associations among key dysregulated proteins. Line colors represent different types of functional associations. D Gene Ontology (GO) pathway enrichment analysis. The bubble plot illustrates significantly enriched molecular functions. The Y-axis lists the enriched GO categories, while the X-axis represents the signal strength, indicating the enrichment level of each category. Bubble size corresponds to the number of genes associated with each category, and the background color reflects the False Discovery Rate (FDR), where lighter shades indicate higher statistical significance. Larger bubbles denote a greater number of associated proteins.

A decrease in the expression (p < 0.01; log2FC < −0.7) of ODO1, PCP4, PDIA6, RS10, and HSP72 may indicate reduced microglial stress, inflammatory signaling, and maladaptive activation. ODO1 downregulation is consistent with a lowered mitochondrial–inflammatory tone in microglia and, therefore, is potentially beneficial for PD. Inflammatory microglial activation is tightly coupled to mitochondrial dysfunction and excess ROS production, which sustains pro-inflammatory signaling and neurotoxicity. Targeting microglial mitochondrial metabolism is proposed as a disease-modifying strategy48. Mechanistically, ODO1 is both a redox-sensitive enzyme and a significant mitochondrial source of H₂O₂/ROS; its activity modulates mitochondrial ROS output and redox signaling. Thus, reduced export of ODO1 in m/mEV cargo is compatible with reduced mitochondrial ROS generation and attenuation of downstream inflammatory cascades49. Reduced PCP4 may indicate dampened calcium/calmodulin signaling, associated with microglial reactivity. Similarly, reduced PDIA6 levels indicate alleviation of endoplasmic reticulum (ER) stress50, while HSP72, although cytoprotective within cells, can act as an extracellular damage-associated molecular pattern (DAMP) when secreted or incorporated into EVs. In this context, extracellular HSP72 is known to activate TLR2/TLR4 and NF-κB signaling in glial and immune cells, thereby amplifying inflammatory cascades51. Consequently, a decrease in HSP72 cargo within m/mEVs following CAND treatment likely reflects attenuation of microglial stress and inflammatory activation, accompanied by a reduced release of pro-inflammatory DAMPs into the extracellular milieu. Reduced RS10 could reflect a shift away from excessive protein synthesis, often seen in pro-inflammatory states. Together, these changes are consistent with a transition toward a less inflammatory, homeostatic microglial phenotype, potentially supporting neuronal survival.

The heatmap of differentially expressed proteins in m/mEVs (Fig. 6B) reveals a distinct proteomic shift indicative of a therapeutic effect, suggesting a coordinated molecular response to treatment. After candesartan treatment, the increased concentration of proteins involved in synaptic maintenance P60880 (SNP25), vesicle trafficking P61106 (RAB14), RNA regulation Q99729 (HNRNPAB), immune modulation P04433, P01703, P07358 (KV311, LV140 CO8B), extracellular matrix stability P19827 (ITIH1), and lipid metabolism P35542 (SAA4) may indicate enhanced microglial support of neuronal function and homeostasis, consistent with treatment-induced neuroprotection. Conversely, proteins associated with ER stress Q15084 (PDIA6), altered protein synthesis P46783 (RS10), cytoskeletal destabilization P48643 (TCPE), and neurotoxic proteolysis P17655 (CAN2) display downregulation after candesartan treatment, suggesting a shift toward a homeostatic, neuroprotective microglial state.

PPI network analysis of m/mEVs post-candesartan treatment (Fig. 6C) reveals a coordinated molecular response indicative of a neuroprotective, homeostatic phenotype. The central cluster, comprising ribosomal and translational regulators (RPS10, RPS12, RPL22, RPL24, EIF3A, FBL, SRP14), supports neuronal maintenance and immune modulation. Strong connectivity between cytoskeletal regulators (CDC42, RAC1, EPB41L1, CD44, LMNB1) and translational machinery indicates a coordinated response that enhances microglial structural plasticity while preventing excessive activation. Additionally, the upregulation of ITIH1, ITIH2, C8B, APOA2, and SAA4 suggests a modulation of immune signaling and complement regulation, contributing to controlled inflammatory responses and reduced neurotoxicity. Together, these adaptations promote a protective microglial state that supports neural stability in PD.

The GO functional enrichment analysis of differentially expressed genes in microglia (Fig. 6D) reveals a significant modulation of biological processes associated with glycosaminoglycan and hyaluronic acid binding, both crucial for extracellular matrix remodeling, immune signaling, and neuroprotection.

Detailed tree maps of the upregulated and downregulated pathways in m/mEVs after candesartan treatment, along with their interpretation, are shown in Supplementary Material: Supplementary Results and Supplementary Figs. 8 and 9.

Discussion

The present methodology allows for the first time the demonstration of brain cellular/molecular effects exerted by the oral administration of angiotensin AT1 receptor antagonists (ARBs) in PD patients. Treatment with candesartan induced the upregulation or downregulation of many proteins relevant to PD progression. These changes were detected not only in EVs derived from neurons (46 dysregulated proteins) and microglia/macrophages (48 dysregulated proteins), but also in astrocytes (22 dysregulated proteins) and oligodendrocytes (92 dysregulated proteins).

PD has traditionally been considered a gray matter/neuronal disease, with glial alterations interpreted as consequences or collateral damage of the neurodegenerative process. However, recent studies have identified novel glial mechanisms that could play significant roles in neurodegeneration. These mechanisms include a glial role beyond the microglial neuroinflammatory response, and astrocyte regulation of the microglial response and neuroinflammation. Astrocytes are essential for providing metabolic support to neurons and preventing neurodegeneration52. The role of oligodendrocytes extends beyond their involvement in myelin formation and demyelinating diseases. Recent multi-omic studies have shown that oligodendrocyte-related genes are significantly altered across all stages of PD in the midbrain, even in early stages, suggesting a role for oligodendrocytes in PD pathogenesis rather than as passive participants in neurodegeneration and neuroinflammation, for instance, by providing intercellular metabolic support to axons through the transfer of energy metabolites53.

The isolation and analysis of EVs from neurons and different types of glial cells and neurons within the same blood sample provides an unprecedented tool for obtaining information on the effects occurring in the brain during pathological processes, and for monitoring the effects of potential neuroprotective treatments. Interestingly, the present study shows for the first time in humans and particularly PD patients that candesartan induces beneficial changes in proteins involved in a series of neuronal and glial processes that the numerous experimental studies (see below) have shown to induce the progression of dopaminergic neuron degeneration and PD, which reinforces the specificity of the proteomic changes observed in the present study. In EVs derived from neurons, candesartan induced a series of changes affecting major mechanisms involved in PD progression. The data suggest neuroprotective effects associated with processes such as the reduction of oxidative stress, ER stress, and mitochondrial dysfunction, reduction of proteotoxic stress burden, enhanced cellular resilience, and synaptic stability. There was also significant enrichment in processes related to dopamine metabolism and transport. Additionally, the downregulation of inflammatory and immune response pathways, such as the regulation of NF-κB transcription activity and response to interferon-gamma, suggests a decrease in the stimulation of inflammatory responses, a major contributor to neuronal degeneration in PD. Changes in aEVs contribute to a more supportive astroglial environment, potentially slowing PD progression and improving neuronal function. Astroglial changes suggest a shift toward reduced neuroinflammation, oxidative stress control, metabolic efficiency, and reduced neuroinflammation, which may contribute to reduced neurodegeneration and improved neuronal resilience in PD patients. Changes in oEVs suggest an adaptive and protective role of oligodendrocytes, enhancing myelination, synaptic function, metabolic efficiency, and neuroimmune balance to prevent excessive oligodendrocyte-mediated inflammation, ultimately supporting neuronal survival and functional recovery post-treatment. Candesartan-induced protein changes in EVs enriched by microglia/macrophage origin (m/mEVs) promote a shift toward a neuroprotective phenotype and a microglial-mediated neuroprotective environment, including cytoskeletal remodeling, metabolic stabilization, diminished oxidative stress, and controlled immune activation, ultimately contributing to a stabilized neural environment and enhanced neuronal survival.

The results observed in EVs from PD patients in the present study are consistent with numerous previous studies in PD animal and cell culture models showing the neuroprotective effects of ARBs by counteracting several major mechanisms of dopaminergic neuron degeneration54. In rodent models and primary mesencephalic cultures, ARBs such as candesartan and telmisartan reduced dopaminergic neuron death induced by neurotoxins such as 6-OHDA6,7, MPTP55,56 or overexpression of alpha-synuclein1 through inhibition of NADPH-oxidase derived oxidative stress and the microglial neuroinflammatory response. AT1 blockers modulated mitochondrial respiration and mitochondrial-derived oxidative stress57,58,59 and regulated mitochondrial dynamics by inhibiting mitochondrial fission60. Similar effects on mitochondrial dynamics were observed by upregulation of the compensatory RAS through administration of Angiotensin 1-760. In a recent study, we also observed that AT1 promotes oxidative stress and intracellular calcium increase, leading to alpha-synuclein aggregation, which is inhibited by AT1 blockers5,61. Angiotensin/AT1 signaling also modulated cholesterol homeostasis in dopaminergic neurons and astrocytes62. Furthermore, mutual regulation between brain angiotensin and dopamine systems has been shown in experimental models in our laboratory63,64,65 and several others54,66.

In conclusion, despite limitations such as the short duration of candesartan treatment (6 months) and a limited number of patients, the present proteomic analysis demonstrates remarkable neuroprotective effects of ARBs crossing the BBB, such as candesartan, on PD patient neurons and glial cells. Using proteomic analysis, the present study reveals that numerous proteins involved in processes related to neuroprotection/neurodegeneration are modified by the treatment of PD patients with candesartan. Future studies using different methodologies focused on the most relevant proteins/targets identified in the present proteomic work may confirm and expand the present results. Above all, our results indicate that larger clinical trials should be conducted using ARBs or other RAS-modifier drugs as an early therapeutic strategy for neuroprotection against the progression of PD.

Methods

Study design and participants

This study analyzed paired serum samples (pre- and post-treatment) from five Parkinson’s disease (PD) patients (2 females, 3 males) enrolled in a 28-week, randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled phase II clinical trial evaluating candesartan vs. placebo13. The trial was conducted at Sant Pau University Hospital (Barcelona), approved by the Ethics Committee, and registered under EudraCT number 2016-000679-25 (https://www.clinicaltrialsregister.eu/ctr-search/trial/2016-000679-25/ES). The trial was conducted following the Declaration of Helsinki and the guidelines of Good Clinical Practice. Written informed consent was obtained before participant inclusion. PD patients were included if they met the following inclusion criteria: neuroimaging evidence within the last 18 months compatible with PD; Hoehn and Yahr (H&Y) stage I-III; stable dopaminergic treatment for at least four weeks before enrollment; and Montreal Cognitive Assessment (MoCA) scores of ≥20 and ≤25 for PD patients with mild cognitive impairment or dementia, or ≥26 for those PD patients with subjective cognitive decline. Exclusion criteria included illiteracy; significant visual or hearing impairment; any severe and/or uncontrolled medical condition deemed clinically relevant for study participation; uncontrolled motor fluctuations or disabling dyskinesia; history of deep brain stimulation; severe white matter involvement on CT or MRI; active psychosis or major hallucinations; severe depression or delirium; or past or current drug or alcohol abuse. Additional exclusion criteria specific to the investigational medication included symptomatic orthostatic hypotension, hypovolemia, or contraindications for antihypertensive drugs; dependence on the renin-angiotensin system (e.g., heart failure class III or IV according to the NYHA classification, unilateral or bilateral renal artery stenosis); current or prior use of ARBs, angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors, or potassium-sparing diuretics; previous treatment with candesartan; hereditary galactose intolerance, glucose-galactose malabsorption; and concomitant use of lithium, acetylcholinesterase inhibitors, anticholinergic agents, or dopamine receptor blockers.

Patients initiated candesartan treatment at a dose of 4 mg/day for the first four weeks. The dose was then titrated to 8 mg/day for the remainder of the study. In cases of adverse events, the study physician could reduce the dose back to 4 mg/day. Treatment was maintained at the target dose until week 24, after which it was tapered to 4 mg/day for four weeks and discontinued at the end of week 28. The specific characteristics of the patients enrolled in this study can be found in Supplementary Tables 1–3.

Blood samples were obtained from each patient before the initiation of treatment and upon its completion. Venipuncture was performed, and blood was collected in Vacutainer SST II Advance Serum Separator Gel tubes (8.5 mL; ref. 366468). The samples were centrifuged at 1500 × g for 10 min to isolate serum. The resulting serum samples were immediately frozen and stored at −80 °C until further analysis. For this study, we analyzed a total of 10 serum samples from 5 PD patients: 5 samples collected before initiating candesartan treatment and 5 obtained at the end of the six-month treatment period. A placebo control group was included in the trial to evaluate clinical effects and particularly cognitive effects13. However, the endpoints analyzed in the proteomic study are objective molecular readouts (quantitative changes in protein abundance within brain-derived EVs) rather than subjective or behavioral outcomes. The observed proteomic shifts, therefore, reflect bona fide pharmacodynamic responses rather than expectancy-related or psychological effects. Each participant served as their own control through a paired within-subject design. This approach markedly reduces inter-individual biological variability (genetic, metabolic, lifestyle, and disease-related) and enhances statistical power to detect drug-induced proteomic changes67. Unlike parallel-group comparisons, where between-subject variance can mask subtle molecular effects, the within-subject design provides a highly sensitive and controlled framework for identifying true pharmacologically driven alterations in the EV proteome.

Isolation of total extracellular vesicles using size exclusion chromatography

Total EVs were isolated from serum samples that had undergone centrifugation at 10,000 × g, for 10 min at 4 °C to ensure the removal of debris. For EV isolation, qEV Original 70 nm Gen2 columns were pre-equilibrated with 17 mL of filtered 1X PBS (0.22 µm filter) before loading a 500 µL sample. A buffer volume of 2.9 mL was used to discard the void volume before EV collection. Five fractions of 0.4 mL each were collected using an Automatic Fraction Collector (AFC) (IZON SCIENCE LTD, New Zealand). Then, the EV-enriched fractions were pooled and concentrated using 100 kDa ultrafiltration devices (Amicon Ultra, Millipore) by centrifugation at 12,000 × g at 4 °C until reaching the desired volume (200 μL). The concentrated EVs were finally transferred to a sterile tube and stored at −80 °C until further analysis. For each individual and time point, two independent 500 µL samples were processed separately and subsequently pooled.

Isolation of brain-derived extracellular vesicles

From an initial 100 µL concentrate of total EVs isolated from 1 mL of serum, a sequential separation was performed to obtain EVs derived from different brain cell types, including neurons, astrocytes, oligodendrocytes, and microglia.

Initially, 100 µL of total EVs were incubated overnight at 4 °C under continuous agitation with 4 µg of L1CAM (L1 Cell Adhesion Molecule)/CD171-Biotin (ref. 13-1919-82, ThermoFisher Scientific) in 300 µL of PBS containing 1.3% BSA for the isolation of neuronal EVs (nEVs). The following day, 200 µL of streptavidin magnetic beads (ThermoFisher Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA) were added and incubated at room temperature for 3 h under agitation. After incubation, the immunocomplexes (containing nEVs) were captured using a magnetic separator, while the supernatant (depleted of nEVs) was collected for subsequent extractions of specific EV subpopulations.

To remove unbound components, the bead-bound nEV immunocomplexes were washed three times with 1000 µL of PBS containing 0.1% BSA. The immunocomplexes were then resuspended in 100 µL of filtered PBS elution buffer and immediately frozen at −80 °C for further characterization and analysis.

The supernatant was sequentially processed to isolate additional brain cell-origin EV subpopulations. First, it was incubated with 4 µg of biotinylated Glast (GLAST (ACSA-1)-Biotin ref. 130-118-984, Miltenyi Biotec) to isolate astrocyte-derived EVs (aEVs), following the same workflow. Next, the remaining supernatant was incubated with 4 µg of biotinylated Human/Mouse MOG (Myelin Oligodendrocyte Glycoprotein)-antibody (Ref. BAM2439, R&D Systems) for oligodendrocyte-derived EVs (oEVs) isolation. Finally, the residual supernatant underwent incubation with 4 µg of biotinylated TMEM119 (Transmembrane protein 119)-antibody (ref. 1023426, Novus Biologicals) to isolate microglia/macrophage-derived EVs (m/mEVs). Each step involved incubation with streptavidin magnetic beads, magnetic separation, and collection of the supernatant for the next extraction. A diagram illustrating the steps involved in isolating EVs enriched from different brain cell types is presented in Fig. 7.

From 1 mL of serum, total EVs (EVT) are extracted using size-exclusion chromatography (SEC) and subsequently incubated with magnetic beads conjugated with antibodies targeting cell-type-specific surface markers: L1CAM (neuronal EVs, nEVs), GLAST (astrocytic EVs, aEVs), MOG (oligodendrocytic EVs, oEVs), and TMEM (microglial/macrophage EVs, m/mEVs). The resulting enriched EV subpopulations are subjected to mass spectrometry-based proteomic analysis, followed by bioinformatic workflows. Illustration created by the authors with BioRender software (www.biorender.com).

Extracellular vesicle characterization by confirmation of the presence of EV marker proteins

Total EVs isolated from 1 mL of serum, along with serum samples, were analyzed using specific ELISA assays to detect established EV markers: CD81 (ref. 18095935), CD63 (ref. 16853020), and ALIX (ref. 30240446). Calnexin (ref. 18234959), an endoplasmic reticulum resident protein generally absent from EVs, was included as a negative control to assess potential non-vesicular contamination. All ELISA kits were sourced from Invitrogen. Serum samples were processed according to the manufacturer’s instructions, and assays with EVs were performed by resuspending 50 µL of total EVs in 50 µL of RIPA buffer, followed by four cycles of sonication (10 s each, 10% amplitude) on ice. The samples were then centrifuged at 10,000 × g for 10 min at 4 °C. A 6 µL aliquot of the supernatant was used for total protein quantification via the Pierce BCA Protein Assay, while 90 µL were loaded onto the corresponding ELISA plates. From this point, all procedures were strictly followed according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Absorbance was measured at 450/620 nm using an Infinite M200 multiwell plate reader (TECAN, Männedorf, Switzerland). Tetraspanin and calnexin concentrations were quantified by extrapolating from a standard curve generated using a four-parameter logistic (4PL) curve fit.

Nanoparticle tracking analysis measurement of extracellular vesicles

The quantification of the hydrodynamic diameter distribution and concentration of extracellular vesicles was performed using the NanoSight PRO (Malvern Instruments), equipped with a blue (488 nm) laser and a high-sensitivity camera. Samples were diluted 1:10.000 in filtered PBS to achieve a particle concentration within the optimal detection range (1 × 10⁷ – 1 × 10⁹ particles/mL). Each sample was measured by recording five 60-s videos at a detection threshold of exposure time 13, contrast gain 3. Automatic settings were applied for blur, minimum track length, and maximum jump distance. The collected videos were analyzed using NTA software (NanoSight NTA 3.4), providing particle size distribution and mean, mode, and median particle diameters. Data were expressed as mean particle size (nm) ± standard deviation and particle concentration (particles/mL).

Transmission electron microscopy characterization of extracellular vesicles

Morphology, size, and structural integrity were evaluated by transmission electron microscopy (TEM). At this end, enriched EVs were diluted 1:10 in distilled water. A 10 μL aliquot of the diluted sample was placed onto a carbon-coated copper grid and allowed to adsorb for 1 min. Excess liquid was carefully removed using filter paper. The grid was then placed on a drop of 1% phosphotungstic acid solution prepared in Milli-Q® water for 1 min, followed by blotting to remove excess stain. Finally, EV morphology was examined using a JEOL JEM 2010 transmission electron microscope operating at 200 kV.

Characterization of brain cell-origin EV subpopulations

To assess neuronal enrichment, neuron-specific enolase (NSE), a glycolytic enzyme predominantly expressed in neurons, was quantified in nEVs using the human neuron-specific Enolase ELISA Kit (ref. ab217778, Abcam). Astrocytic enrichment was evaluated using the Glial Fibrillary Acidic Protein (GFAP) ELISA kit (ref. EEL079, Invitrogen), as GFAP is a specific intermediate filament protein predominantly expressed in astrocytes. For the assessment of oligodendrocytic and microglial enrichment, the Human Myelin Basic Protein (MBP) ELISA kit (Ref. MBS2502574, MyBioSource) and the Ionized Calcium-Binding Adapter Molecule 1 (IBA-1) ELISA kit (ref. ABIN6953617, Antibodies Online) were used, respectively. MBP, a key structural component of the myelin sheath, is exclusively expressed by oligodendrocytes and serves as a well-established marker for oligodendrocyte-derived EVs. IBA-1, a cytoplasmic protein involved in actin remodeling and phagocytosis, is specifically expressed in microglia, making it a reliable marker for microglia-derived EVs. To ensure the robustness of the analysis, markers not expected to be enriched in each extracellular vesicle population derived from brain-origin cells were also evaluated.

For each ELISA assay, 50 µL of EV samples from the different subpopulations were resuspended in 50 µL of RIPA buffer and subjected to four sonication cycles (10 s each, 10% amplitude) on ice. The samples were then centrifuged at 10,000 × g for 10 min at 4 °C. A 6 µL aliquot of the supernatant was used to determine total protein concentration using the Pierce BCA Protein Assay, while 90 µL were loaded onto the corresponding ELISA plates.

From this point, all assays were performed strictly following the manufacturer’s instructions. Absorbance was measured at 450/620 nm using an Infinite M200 multiwell plate reader (TECAN, Männedorf, Switzerland). Protein marker concentrations were quantified by extrapolation from a four-parameter logistic (4PL) standard curve.

Quantitative proteomic analysis by SWATH-MS

Proteomic analysis was conducted as previously described68,69. Briefly, EV proteins were concentrated by SDS-PAGE70, stained, excised, and subjected to in-gel tryptic digestion71. Peptides were extracted, pooled, and stored until analysis. For label-free quantification, SWATH-MS was performed using a TripleTOF® 6600 system72,73. Spectral libraries were generated from pooled peptide samples using data-dependent acquisition, including only high-confidence identifications74. Individual samples from various EV subtypes (MOG, TMEM, L1CAM, GLAST, total EVs, and plasma) collected before and after candesartan treatment were analyzed using data-independent acquisition.

Peptide signals were extracted and quantified using PeakView and MarkerView software. Normalization was performed using the most likely ratio method, and data visualization included principal component analysis (PCA). Proteomics data were deposited in the PRIDE repository (PXD063198)75.

All information regarding the function, subcellular localization, and tissue-specific expression of differentially expressed proteins identified in extracellular vesicles was obtained from UniProt (https://www.uniprot.org) and the Human Protein Atlas (https://www.proteinatlas.org).

Statistical analysis

For EV characterization, normality and homoscedasticity were assessed using Shapiro–Wilk and equal variance tests, respectively. Depending on data distribution, either parametric (unpaired t-test) or non-parametric (Mann–Whitney U test) methods were applied for two-group comparisons. For multi-group analyses, Kruskal–Wallis ANOVA on ranks followed by Student–Newman–Keuls post hoc testing was used. Statistical significance was set at P < 0.05.

Bioinformatic analyses were carried out in R (v4.1.2). Data were log-transformed, quantile normalized, and analyzed using linear models (limma, v3.50.3), with differentially enriched proteins defined by P < 0.05 and fold change ≥1.5 or <0.6. Visualization was carried out using heatmap3 (v1.1.9), Glimma (v2.4.0), and GraphPad Prism 8. Functional annotation was performed with clusterProfiler (v4.2.2) and rrvgo (v1.6.0). Protein–protein interaction analysis was conducted using STRING (v12.0) for Homo sapiens with a minimum interaction score of 0.7. GO enrichment and network visualization were also done within STRING and exported for interpretation.

Data availability

The mass spectrometry proteomics data have been deposited in the ProteomeXchange Consortium via the PRIDE partner repository with the dataset identifier PXD063198. The data supporting the conclusions of this article are included within the article and its Supplementary Information.

References

Rodriguez-Perez, A. I. et al. Angiotensin type 1 receptor antagonists protect against alpha-synuclein-induced neuroinflammation and dopaminergic neuron death. Neurotherapeutics 15, 1063–1081 (2018).

Villar-Cheda, B., Valenzuela, R., Rodriguez-Perez, A. I., Guerra, M. J. & Labandeira-Garcia, J. L. Aging-related changes in the nigral angiotensin system enhances proinflammatory and pro-oxidative markers and 6-OHDA-induced dopaminergic degeneration. Neurobiol. Aging 33, 204.e201–204.e211 (2012).

Gohlke, P. et al. Effects of orally applied candesartan cilexetil on central responses to angiotensin II in conscious rats. J. Hypertens. 20, 909–918 (2002).

Unger, T. Inhibiting angiotensin receptors in the brain: possible therapeutic implications. Curr. Med. Res. Opin. 19, 449–451 (2003).

Lage, L., Rodriguez-Perez, A. I., Villar-Cheda, B., Labandeira-Garcia, J. L. & Dominguez-Meijide, A. Angiotensin type 1 receptor activation promotes neuronal and glial alpha-synuclein aggregation and transmission. NPJ Parkinsons Dis. 10, 37 (2024).

Quijano, A. et al. Angiotensin Type-1 Receptor Inhibition Reduces NLRP3 Inflammasome Upregulation Induced by Aging and Neurodegeneration in the Substantia Nigra of Male Rodents and Primary Mesencephalic Cultures. Antioxidants 11 https://doi.org/10.3390/antiox11020329 (2022).

Rodriguez-Pallares, J. et al. Brain angiotensin enhances dopaminergic cell death via microglial activation and NADPH-derived ROS. Neurobiol. Dis. 31, 58–73 (2008).

Kamath, T. et al. Single-cell genomic profiling of human dopamine neurons identifies a population that selectively degenerates in Parkinson’s disease. Nat. Neurosci. 25, 588–595 (2022).

Lee, A. J. et al. Characterization of altered molecular mechanisms in Parkinson’s disease through cell type-resolved multiomics analyses. Sci. Adv. 9, eabo2467 (2023).

Martirosyan, A. et al. Unravelling cell type-specific responses to Parkinson’s Disease at single cell resolution. Mol. Neurodegener. 19, 7 (2024).

Jo, Y., Kim, S., Ye, B. S., Lee, E. & Yu, Y. M. Protective effect of renin-angiotensin system inhibitors on Parkinson’s disease: a nationwide cohort study. Front Pharm. 13, 837890 (2022).

Lin, H. C. et al. Association of angiotensin receptor blockers with incident parkinson disease in patients with hypertension: a retrospective cohort study. Am. J. Med. 135, 1001–1007 (2022).

Kulisevsky, J. et al. A randomized clinical trial of candesartan for cognitive impairment in Parkinson’s disease. Parkinsonism Relat. Disord. 110, 105367 (2023).

Pagonabarraga, J., Kulisevsky, J., Strafella, A. P. & Krack, P. Apathy in Parkinson’s disease: clinical features, neural substrates, diagnosis, and treatment. Lancet Neurol. 14, 518–531 (2015).

Ababei, D. C. et al. Therapeutic implications of renin-angiotensin system modulators in Alzheimer’s dementia. Pharmaceutics 15 https://doi.org/10.3390/pharmaceutics15092290 (2023).

Lee, H. W. et al. Neuroprotective effect of angiotensin II receptor blockers on the risk of incident Alzheimer’s disease: a nationwide population-based cohort study. Front. Aging Neurosci. 15, 1137197 (2023).

Bordet, S. et al. An open-label, non-randomized, drug-repurposing study to explore the clinical effects of angiotensin II type 1 (AT1) receptor antagonists on anxiety and depression in Parkinson’s disease. Mov. Disord. Clin. Pr. 12, 653–658 (2025).

Gonzalez-Robles, C. et al. Treatment selection and prioritization for the EJS ACT-PD MAMS trial platform. Mov. Disord https://doi.org/10.1002/mds.30190 (2025).

O’Brien, J. T. et al. RENEWAL: repurposing study to find NEW compounds with Activity for Lewy body dementia-an international Delphi consensus. Alzheimers Res. Ther. 14, 169 (2022).

Jeppesen, D. K., Zhang, Q., Franklin, J. L. & Coffey, R. J. Extracellular vesicles and nanoparticles: emerging complexities. Trends Cell Biol. 33, 667–681 (2023).

Xia, X., Wang, Y. & Zheng, J. C. Extracellular vesicles, from the pathogenesis to the therapy of neurodegenerative diseases. Transl. Neurodegener. 11, 53 (2022).

Schrag, A., Sampaio, C., Counsell, N. & Poewe, W. Minimal clinically important change on the unified Parkinson’s disease rating scale. Mov. Disord. 21, 1200–1207 (2006).

Heremans, I. P. et al. Parkinson’s disease protein PARK7 prevents metabolite and protein damage caused by a glycolytic metabolite. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 119 https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.2111338119 (2022).

Skou, L. D., Johansen, S. K., Okarmus, J. & Meyer, M. Pathogenesis of DJ-1/PARK7-mediated Parkinson’s disease. Cells 13 https://doi.org/10.3390/cells13040296 (2024).

Sot, B. et al. The chaperonin CCT inhibits assembly of alpha-synuclein amyloid fibrils by a specific, conformation-dependent interaction. Sci. Rep. 7, 40859 (2017).

Silvestro, S., Raffaele, I. & Mazzon, E. Modulating stress proteins in response to therapeutic interventions for Parkinson’s disease. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 24 https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms242216233 (2023).

Yan, M. et al. Cofilin 1 promotes the pathogenicity and transmission of pathological alpha-synuclein in mouse models of Parkinson’s disease. NPJ Parkinsons Dis. 8, 1 (2022).

Kulkarni, A. et al. Proteostasis in Parkinson’s disease: recent development and possible implications in diagnosis and therapeutics. Ageing Res Rev. 84, 101816 (2023).

Innos, J. et al. Deletion of the Lsamp gene lowers sensitivity to stressful environmental manipulations in mice. Behav. Brain Res. 228, 74–81 (2012).

Almalki, A. et al. Mutation of the human mitochondrial phenylalanine-tRNA synthetase causes infantile-onset epilepsy and cytochrome c oxidase deficiency. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1842, 56–64 (2014).

Rott, R. et al. SUMOylation and ubiquitination reciprocally regulate alpha-synuclein degradation and pathological aggregation. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 114, 13176–13181 (2017).

Shu, L. P., Zhou, Z. W., Zi, D., He, Z. X. & Zhou, S. F. A SILAC-based proteomics elicits the molecular interactome of alisertib (MLN8237) in human erythroleukemia K562 cells. Am. J. Transl. Res 7, 2442–2461 (2015).

Bellia, F., Vecchio, G. & Rizzarelli, E. Carnosinases, their substrates and diseases. Molecules 19, 2299–2329 (2014).

Zhou, Z. et al. Correlation between serum carnosinase concentration and renal damage in diabetic nephropathy patients. Amino Acids 53, 687–700 (2021).

Chandrasekaran, S. & Bonchev, D. A network view on Parkinson’s disease. Comput Struct. Biotechnol. J. 7, e201304004 (2013).

Li, F., Kang, X., Xin, W. & Li, X. The emerging role of extracellular vesicle derived from neurons/neurogliocytes in central nervous system diseases: novel insights into ischemic stroke. Front. Pharm. 13, 890698 (2022).

Okumura, M., Miura, M. & Chihara, T. The roles of tubulin-folding cofactors in neuronal morphogenesis and disease. Neural Regen. Res. 10, 1388–1389 (2015).

Inoue, S. et al. Drebrin-like (Dbnl) controls neuronal migration via regulating N-cadherin expression in the developing cerebral cortex. J. Neurosci. 39, 678–691 (2019).

Nokkari, A. et al. Implication of the Kallikrein-Kinin system in neurological disorders: quest for potential biomarkers and mechanisms. Prog. Neurobiol. 165-167, 26–50 (2018).

Chen, R. et al. Chloride intracellular channel 4 blockade improves cognition in mice with Alzheimer’s disease: CLIC4 protein expression and tau protein hyperphosphorylation. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 278, 134972 (2024).

Horvat, S. et al. The alpha- to gamma-enolase switch: The role and regulation of gamma-enolase during oligodendrocyte differentiation. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 301, 140464 (2025).

Astillero-Lopez, V. et al. Proteomic analysis identifies HSP90AA1, PTK2B, and ANXA2 in the human entorhinal cortex in Alzheimer’s disease: potential role in synaptic homeostasis and Abeta pathology through microglial and astroglial cells. Brain Pathol. 34, e13235 (2024).

Mitra, S. et al. Natural products targeting Hsp90 for a concurrent strategy in glioblastoma and neurodegeneration. Metabolites 12 https://doi.org/10.3390/metabo12111153 (2022).

Shibata, Y. et al. p47 negatively regulates IKK activation by inducing the lysosomal degradation of polyubiquitinated NEMO. Nat. Commun. 3, 1061 (2012).

Qu, L., Ji, Y., Zhu, X. & Zheng, X. hCINAP negatively regulates NF-kappaB signaling by recruiting the phosphatase PP1 to deactivate IKK complex. J. Mol. Cell Biol. 7, 529–542 (2015).

Jain, N. & Ganesh, S. Emerging nexus between RAB GTPases, autophagy and neurodegeneration. Autophagy 12, 900–904 (2016).

Cohn, W. et al. Multi-omics analysis of microglial extracellular vesicles from human alzheimer’s disease brain tissue reveals disease-associated signatures. Front. Pharm. 12, 766082 (2021).

Li, Y., Xia, X., Wang, Y. & Zheng, J. C. Mitochondrial dysfunction in microglia: a novel perspective for pathogenesis of Alzheimer’s disease. J. Neuroinflam. 19, 248 (2022).

Tretter, L. & Adam-Vizi, V. Generation of reactive oxygen species in the reaction catalyzed by alpha-ketoglutarate dehydrogenase. J. Neurosci. 24, 7771–7778 (2004).

Yassin, O. et al. Opposing regulation of endoplasmic reticulum retention under stress by ERp44 and PDIA6. Biochem. J. 481, 1921–1935 (2024).

Gulke, E., Gelderblom, M. & Magnus, T. Danger signals in stroke and their role on microglia activation after ischemia. Ther. Adv. Neurol. Disord. 11, 1756286418774254 (2018).

Bantle, C. M., Hirst, W. D., Weihofen, A. & Shlevkov, E. Mitochondrial dysfunction in astrocytes: a role in Parkinson’s disease?. Front. Cell Dev. Biol. 8, 608026 (2020).

Castelo-Branco, G., Kukanja, P., Guerreiro-Cacais, A. O. & Rubio Rodriguez-Kirby, L. A. Disease-associated oligodendroglia: a putative nexus in neurodegeneration. Trends Immunol. 45, 750–759 (2024).

Labandeira-Garcia, J. L., Labandeira, C. M., Guerra, M. J. & Rodriguez-Perez, A. I. The role of the brain renin-angiotensin system in Parkinson's disease. Transl. Neurodegener. 13, 22 (2024).

Garrido-Gil, P., Joglar, B., Rodriguez-Perez, A. I., Guerra, M. J. & Labandeira-Garcia, J. L. Involvement of PPAR-gamma in the neuroprotective and anti-inflammatory effects of angiotensin type 1 receptor inhibition: effects of the receptor antagonist telmisartan and receptor deletion in a mouse MPTP model of Parkinson’s disease. J. Neuroinflam. 9, 38 (2012).

Joglar, B. et al. The inflammatory response in the MPTP model of Parkinson’s disease is mediated by brain angiotensin: relevance to progression of the disease. J. Neurochem. 109, 656–669 (2009).

Rodriguez-Pallares, J., Parga, J. A., Joglar, B., Guerra, M. J. & Labandeira-Garcia, J. L. Mitochondrial ATP-sensitive potassium channels enhance angiotensin-induced oxidative damage and dopaminergic neuron degeneration. Relevance for aging-associated susceptibility to Parkinson’s disease. Age 34, 863–880 (2012).

Valenzuela, R. et al. Mitochondrial angiotensin receptors in dopaminergic neurons. Role in cell protection and aging-related vulnerability to neurodegeneration. Cell Death Dis. 7, e2427 (2016).

Valenzuela, R. et al. An ACE2/Mas-related receptor MrgE axis in dopaminergic neuron mitochondria. Redox Biol. 46, 102078 (2021).

Quijano, A. et al. Modulation of mitochondrial dynamics by the angiotensin system in dopaminergic neurons and microglia. Aging Dis. https://doi.org/10.14336/AD.2024.0981 (2024).

Lage, L., Rodriguez-Perez, A. I., Labandeira-Garcia, J. L. & Dominguez-Meijide, A. Angiotensin type-1 receptor autoantibodies promote alpha-synuclein aggregation in dopaminergic neurons. Front. Immunol. 15, 1457459 (2024).

Lopez-Lopez, A. et al. Interactions between Angiotensin type-1 antagonists, statins, and ROCK inhibitors in a rat model of L-DOPA-induced dyskinesia. Antioxidants 12 https://doi.org/10.3390/antiox12071454 (2023).

Dominguez-Meijide, A., Rodriguez-Perez, A. I., Diaz-Ruiz, C., Guerra, M. J. & Labandeira-Garcia, J. L. Dopamine modulates astroglial and microglial activity via glial renin-angiotensin system in cultures. Brain Behav. Immun. 62, 277–290 (2017).

Villar-Cheda, B. et al. Aging-related dysregulation of dopamine and angiotensin receptor interaction. Neurobiol. Aging 35, 1726–1738 (2014).

Villar-Cheda, B. et al. Nigral and striatal regulation of angiotensin receptor expression by dopamine and angiotensin in rodents: implications for progression of Parkinson’s disease. Eur. J. Neurosci. 32, 1695–1706 (2010).

Aschrafi, A. et al. Angiotensin II mediates the axonal trafficking of tyrosine hydroxylase and dopamine beta-hydroxylase mRNAs and enhances norepinephrine synthesis in primary sympathetic neurons. J. Neurochem. 150, 666–677 (2019).

Backes, C. et al. Paired proteomics, transcriptomics and miRNomics in non-small cell lung cancers: known and novel signaling cascades. Oncotarget 7, 71514–71525 (2016).

Candamo-Lourido, M. et al. Comparative brain proteomic analysis between sham and cerebral ischemia experimental groups. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 25 https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms25147538 (2024).

Casado-Fernandez, L. et al. The proteomic signature of circulating extracellular vesicles following intracerebral hemorrhage: novel insights into mechanisms underlying recovery. Neurobiol. Dis. 201, 106665 (2024).

Abramowicz, A. et al. Harmonization of exosome isolation from culture supernatants for optimized proteomics analysis. PLoS ONE 13, e0205496 (2018).

Rodrigues, J. S. et al. dsRNAi-mediated silencing of PIAS2beta specifically kills anaplastic carcinomas by mitotic catastrophe. Nat. Commun. 15, 3736 (2024).

Torres Iglesias, G. et al. Brain and immune system-derived extracellular vesicles mediate regulation of complement system, extracellular matrix remodeling, brain repair and antigen tolerance in Multiple Sclerosis. Brain Behav. Immun. 113, 44–55 (2023).