Abstract

I present a method for estimating the fidelity F(μ, τ) between a preparable quantum state μ and a classically specified pure target state \(\tau =\left|\tau \right\rangle \left\langle \tau \right|\), using simple quantum circuits and on-the-fly classical calculation (or lookup) of selected amplitudes of \(\left|\tau \right\rangle\). The method is sample efficient for anticoncentrated states (including many states that are hard to simulate classically), with approximate cost 4ϵ−2(1 − F)dpcoll where ϵ is the desired precision of the estimate, d is the dimension of the Hilbert space, and pcoll is the collision probability of the target distribution. This scaling is exponentially better than that of any method based on classical sampling. I also present a more sophisticated version of the method that uses any efficiently preparable and well-characterized quantum state as an importance sampler to further reduce the number of copies of μ needed. Though some challenges remain, this work takes a significant step toward scalable verification of complex states produced by quantum processors.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

One of the more promising and imminent applications of quantum computers is the efficient preparation of quantum states that model complex, computationally challenging domains. For example, quantum computers can in principle efficiently simulate states of quantum many-body systems1,2 and learn to output states that model complex data sets3,4. But real quantum processors have imperfections, and the algorithms themselves often involve approximations whose impact is not fully understood. Consequently, for the foreseeable future, complex states produced by quantum processors need to be experimentally verified. Unfortunately, verifying many-qubit states presents a major challenge since the number of parameters specifying a quantum state is generally exponential in the number of qubits. Recently developed quantum processors are already capable of producing states too large and complex to be directly verified using available methods5.

Nearly all known methods for efficiently verifying large quantum states either require the state to have special structure or require additional quantum resources. If one has the means to prepare reference copies of the target state \(\left|\tau \right\rangle\), the quantum swap test6 can be used to estimate the fidelity of any quantum state \(\left|\mu \right\rangle\) with respect to \(\left|\tau \right\rangle\) using O(1) copies of \(\left|\tau \right\rangle\). But often, reference copies of the target state are not available. In such cases, known structure of the state in question may be used to reduce the number of measurements needed to characterize it. For example, pure or low-rank states are described by exponentially fewer parameters than mixed states (though still exponentially many). Compressive sampling can be used to efficiently learn quantum states that are sparse in a known basis7,8,9,10. States produced by local dynamics can also be efficiently characterized11. Notably, it is not necessary to fully characterize an unknown state in order to verify it. One approach, proposed in12,13, is to express F(μ, τ) as a sum of terms that are sampled and estimated separately. That approach enables scalable verification of states that are concentrated in the Pauli operator basis.

In this Letter I present a hybrid (quantum-classical) algorithm, designated EVAQS, for efficient verification of quantum states that are anticoncentrated in feasible measurement bases. The algorithm estimates the fidelity F(μ, τ) between a preparable quantum state μ and a classically-described pure quantum state \(\tau =\left|\tau \right\rangle \left\langle \tau \right|\). (The symbols μ and τ are chosen as mnemonics for unknown and target.) The underlying idea of the algorithm is to compare randomly selected sparse projections or snippets of the unknown state μ against corresponding snippets of the target state τ. Since the snippets of τ are small they can be efficiently calculated and prepared. The fidelity between μ and τ is then estimated as a weighted average of the fidelities of corresponding snippets. The basic version of EVAQS consists of a simple feed-forward quantum circuit applied to multiple copies of the prepared state μ and two ancilla qubits. The feed-forward part of the circuit involves an on-the-fly classical calculation (or lookup) of a few randomly-selected probability amplitudes of \(\left|\tau \right\rangle\). Such feed-forward operation will be possible on commercially available quantum devices in the near future14. In the meantime, the algorithm may be approximated by calculating amplitudes afterwards and using postselection, albeit with higher cost.

The cost of the algorithm is quantified by the number of times N the testing circuit must be run to estimate F(μ, τ) to precision ϵ. In the important regime in which μ is close to τ, \(N\approx 4{\epsilon }^{-2}(1-F(\mu ,\tau ))d{p}_{\,{{\mbox{coll}}}\,}^{(\tau )}\) where d is the dimension of the Hilbert space in which μ, τ reside and \({p}_{\,{{\mbox{coll}}}\,}^{(\tau )}\) is the collision probability of the induced classical target distribution in the computational basis. Note that \({p}_{\,{{\mbox{coll}}}\,}^{(\tau )}\) is a measure of the concentratedness of \(\left|\tau \right\rangle\) (\(1/{p}_{\,{{\mbox{coll}}}\,}^{(\tau )}\) is the effective support of \(\left|\tau \right\rangle\)). It follows that EVAQS is efficient if \(\left|\tau \right\rangle\) is anticoncentrated. Optionally, an auxiliary quantum state \(\alpha =\left|\alpha \right\rangle \left\langle \alpha \right|\) (the symbol α is a mnemonic for auxiliary) may be used to importance sample μ, further reducing the number of repetitions needed. Any pure state that is efficiently preparable, well-characterized, and has support over \(\left|\tau \right\rangle\) may be used. For this more general version of the algorithm I find that N ≈ 4ϵ−2(1 − F(μ, τ))(1 + χ2(τ, α)) where χ2(τ, α) is the chi-square divergence between the classical distributions induced by \(\left|\alpha \right\rangle\) and \(\left|\tau \right\rangle\). In this version, the efficiency of EVAQS is limited only by how well \(\left|\alpha \right\rangle\) samples \(\left|\tau \right\rangle\).

The state verification method proposed here constitutes a truly quantum capability, as there is no method of verifying an anticoncentrated classical distribution with fewer than O(d1/2) samples, where d is the effective support. (This follows from applying Theorem 1 of ref. 15 to the uniform distribution.) And until recently, there was no known efficient method of verifying arbitrary anticoncentrated quantum states. While this manuscript was in preparation, Huang et al.16 introduced a type of randomized tomography that enables low-rank projections (e.g., fidelities) of an arbitrary quantum state to be estimated efficiently. That method can be used for the same purpose as EVAQS, but the two methods appear to provide different tradeoffs in classical and quantum complexity. Regardless of which of method is ultimately found to be more practical, the approach described here stands to be interesting in its own right.

This work addresses a major problem (namely, sample complexity) for verification of some large quantum states, but it must be acknowledged that some challenges remain. First of all, quantum states that have an intermediate amount of concentration fall in the gap between this work and prior work and remain difficult to verify. For example, spin-glass states can simultaneously have exponentially large support (making them costly for standard methods) and be exponentially sparse (making them more difficult for the method described here). Second, there is the very fundamental problem that verifying a quantum state requires a specification of its readily measurable properties, whereas the most useful quantum states for computational purposes are the ones for which such a classical specification is likely to be difficult to obtain. While it is perhaps too much to hope that all interesting quantum states would be efficiently verifiable, this work shows that some significant inroads may be made.

Results

The EVAQS algorithm

Let μ be an efficiently preparable n-qubit state that is intended to approximate a pure target state \(\tau =\left|\tau \right\rangle \left\langle \tau \right|\). In most of this work it will be assumed that μ is pure, \(\mu =\left|\mu \right\rangle \left\langle \mu \right|\); the validity of the method for mixed μ will be established in section 4.1. Let \(\left|\tau \right\rangle =\mathop{\sum }\nolimits_{x = 1}^{d}{\tau }_{x}\left|x\right\rangle\) where d = 2n. Let us call a projection of \(\left|\tau \right\rangle\) onto a sparse subset of the computational basis a snippet. The EVAQS algorithm is motivated by two observations: The first is that \(\left|\mu \right\rangle\) and \(\left|\tau \right\rangle\) are similar if and only if all corresponding snippets of \(\left|\mu \right\rangle\) and \(\left|\tau \right\rangle\) are similar. The second is that, given the ability to compute selected coefficients of \(\left|\tau \right\rangle\), it is not difficult to prepare snippets of \(\left|\tau \right\rangle\) for direct comparison with corresponding snippets of \(\left|\mu \right\rangle\). This suggests the following strategy: (a) Project out a random snippet of \(\left|\mu \right\rangle\). (b) Construct the corresponding snippet of \(\left|\tau \right\rangle\) and test its fidelity with the snippet of \(\left|\mu \right\rangle\) using the quantum swap test17. (c) Repeat (a)-(b) many times and estimate the fidelity \(F(\mu ,\tau )\equiv \left\langle \tau \right|\mu \left|\tau \right\rangle ={\left|\left\langle \mu | \tau \right\rangle \right| }^{2}\) as a weighted average of the fidelities of the projected snippets. In a nutshell, the idea is to verify a quantum state by verifying its projections onto random two-dimensional subspaces.

Below I present two versions of the algorithm: a basic version that samples \(\left|\mu \right\rangle\) uniformly and is efficient when \(\left|\tau \right\rangle\) is anticoncentrated, and a more general version that uses an auxiliary quantum state \(\left|\alpha \right\rangle\) to importance sample \(\left|\mu \right\rangle\) when \(\left|\tau \right\rangle\) is not anticoncentrated. In principle \(\left|\alpha \right\rangle\) can be any accurately characterized reference state, but to be useful it should place substantial probability on the support of \(\left|\tau \right\rangle\) while being significantly easier to prepare than \(\left|\tau \right\rangle\) itself. The general version of the algorithm involves a larger and more complex quantum circuit than the basic version, but requires far fewer circuit repetitions when \(\left|\alpha \right\rangle\) is a substantially better sampler of \(\left|\mu \right\rangle\) than the uniform distribution. Both versions of the algorithm require the ability to calculate on a classical computer \({\tau }_{x}^{\prime}\propto {\tau }_{x}\) for any given x; for the general version, the ability to calculate \({\alpha }_{x}^{\prime}\propto {\alpha }_{x}\) is also required. These coefficients must be calculated on demand (or retrieved from a precomputed table) during the circuit, within the decoherence time of an unmeasured ancilla qubit. The prospect of calculating these coefficients after the circuit and using postselection, at the cost of requiring more circuit runs, is considered in Supplementary Material 1.4.

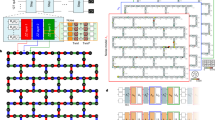

The basic version of the algorithm is implemented by a repeating a short quantum-classical circuit involving a test register containing the unknown state \(\left|\mu \right\rangle \in {{{{\mathcal{H}}}}}_{{2}^{n}}\) and two ancilla qubits (Fig. 1a). The steps of the circuit are as follows:

-

1.

Prepare the unknown state \(\left|\mu \right\rangle\) and one of the ancillas in the state \((\left|0\right\rangle +\left|1\right\rangle )/\sqrt{2}\).

-

2.

Draw a uniformly distributed random number v ∈ {0, 1}n and perform controlled-NOT operations between the ancilla qubit and each qubit i in the test register for which vi = 1.

-

3.

Measure the test register in the computational basis, obtaining a value x.

-

4.

Compute \({\tau }_{x}^{\prime}\propto {\tau }_{x}\) and \({\tau }_{y}^{\prime}\propto {\tau }_{y}\) where y = x ⊕ v ( ⊕ denotes vector addition modulo 2).

-

5.

Prepare the second ancilla qubit in the normalized state

$$\left|{\tau }_{yx}\right\rangle \propto {\tau }_{y}^{\prime}\left|0\right\rangle +{\tau }_{x}^{\prime}\left|1\right\rangle .$$(1) -

6.

Measure the two ancilla qubits in the Bell basis and set b = ±1 if \(\left|{{{\Phi }}}_{\pm }\right\rangle \equiv (\left|0\right\rangle \left|0\right\rangle \pm \left|1\right\rangle \left|1\right\rangle )/\sqrt{2}\) is obtained, otherwise set b = 0. (Note that the Bell measurement can be performed by a controlled-NOT between the ancillas followed by a pair of single-qubit measurements, as shown in Fig. 1a.)

The general version of the algorithm uses an additional n-qubit register containing an auxiliary state \(\left|\alpha \right\rangle\) (Fig. 1b). In principle \(\left|\alpha \right\rangle\) can be any well-known quantum state, though later it will be shown that the efficiency of the algorithm directly depends on how well \(\left|\alpha \right\rangle\) samples both \(\left|\tau \right\rangle\) and the error vector \(\left|\mu \right\rangle -\left|\tau \right\rangle\). In this case the steps of the circuit are:

-

1.

Prepare the test register, auxiliary register, and first ancilla qubit in the state \(\left|\psi \right\rangle =\frac{1}{\sqrt{2}}\left|\mu \right\rangle \left|\alpha \right\rangle (\left|0\right\rangle +\left|1\right\rangle )\).

-

2.

Perform a controlled swap between the test and auxiliary registers, using the first ancilla qubit as the control.

-

3.

Measure the test and auxiliary registers in the computational basis, obtaining values x, y, respectively.

-

4.

Compute \({\tau }_{x}^{\prime}\propto {\tau }_{x}\), \({\tau }_{y}^{\prime}\propto {\tau }_{y}\), \({\alpha }_{x}^{\prime}\propto {\alpha }_{x}\), and \({\alpha }_{y}^{\prime}\propto {\alpha }_{y}\).

-

5.

Prepare a second ancilla qubit in the normalized state

$$\left|{r}_{yx}\right\rangle \propto \frac{{\tau }_{y}^{\prime}}{{\alpha }_{y}^{\prime}}\left|0\right\rangle +\frac{{\tau }_{x}^{\prime}}{{\alpha }_{x}^{\prime}}\left|1\right\rangle .$$(2) -

6.

Same as for the basic version.

For either version of the algorithm, steps 1–6 are repeated N ≫ 1 times. Let xi, yi, bi denote the values obtained in the ith trial. Define the sample weight

where \({\alpha }_{x}^{\prime}={2}^{-n/2}\) for the basic version of the algorithm. Then F(μ, τ) is estimated by the quantity

where

The simple estimator (4) has a bias of order N−1. In practice this is usually negligible, but for completeness an estimator that is unbiased to order N−1 is derived in Supplementary Material 1.1.

a Basic circuit. b A more sophisticated circuit using an auxiliary state \(\left|\alpha \right\rangle\) for importance sampling, which reduces the number of circuit repetitions needed when τ is not anticoncentrated. In either case, the circuit is repeated many times and the fidelity F(μ, τ) is estimated in terms of weighted averages of \(b={(-1)}^{{m}_{1}}{m}_{2}\) and b2 (eqs. (4)-(6)). Notation: H = Hadamard gate; X = Pauli X gate; 0/1 block = measurement in the computational basis; rng random number generator.

The circuit for the basic algorithm is quite simple, consisting of (on average) just n/2 + 1 controlled-NOT gates and a few single-qubit gates and measurements. The general version replaces the (on average) n/2 controlled-NOT gates with n controlled-SWAP (Fredkin) gates between n pairs of qubits. Each controlled-SWAP gate requires a handful of standard 1- and 2-qubit gates18,19. Altogether the general version uses approximately twice as many qubits and roughly ten times as many gates as the basic version. However, if \(\left|\alpha \right\rangle\) is substantially better at sampling \(\left|\tau \right\rangle\) than the uniform distribution, the general version will require substantially fewer circuit repetitions to obtain a precise estimate.

Performance

Cost to achieve a given precision

The cost of EVAQS is driven by the number of samples needed to obtain an estimate with sufficiently small variance. In a typical application the expectation is that μ is not a bad approximation of τ; thus the regime of greatest interest is that of small infidelity I ≡ 1 − F. For the ensuing discussion it will be supposed that μ is pure, though the same cost estimate is obtained for the case that μ is mixed (see Section 4.2). To lowest order in I and statistical fluctuations, the variance of \(\tilde{F}\) can be written as

where \(\left|\varepsilon \right\rangle \equiv {e}^{-{{{\rm{i}}}}\phi }\left|\mu \right\rangle -\left|\tau \right\rangle\) is the error of \(\left|\mu \right\rangle\) upon correcting its global phase ϕ, defined via \(\left\langle \tau | \mu \right\rangle =\sqrt{F}{e}^{{{{\rm{i}}}}\phi }\). (For the basic version of the algorithm one may take αx = d−1/2). As shown in Section 4.2, \({\left|{\varepsilon }_{x}\right|}^{2}\) is (to lowest order) also proportional to I, so that the entire expression is proportional to I. Note that \({{{\rm{Var}}}}\tilde{F}\) does not depend on the phases of the components of \(\left|\alpha \right\rangle\).

The worst case is that the error resides entirely on the component x for which \(\left|{\tau }_{x}/{\alpha }_{x}\right|\) is largest, i.e., the basis state which is most badly undersampled. In non-adversarial scenarios the error may be expected to be distributed across the support of τ. Simulations indicate that for plausible error models \({\sum }_{x}{\left|{\tau }_{x}\right|}^{2}{\left|{\varepsilon }_{x}\right|}^{2}/{\left|{\alpha }_{x}\right|}^{2}\) is typically comparable in magnitude to \(I{\sum }_{x}{\left|{\tau }_{x}\right|}^{4}/{\left|{\alpha }_{x}\right|}^{2}\). This leads to the approximate scaling law

where ϵ2 is the desired variance and \({\chi }^{2}(\tau ,\alpha )\equiv {\sum }_{x}{(| {\tau }_{x}{| }^{2}-| {\alpha }_{x}{| }^{2})}^{2}/| {\alpha }_{x}{| }^{2}\) is the chi-square divergence of τ with respect to α (in this context regarded as classical distributions over the computational basis). χ2 is a standard statistical measure that quantifies the distance between distributions τ and α, heavily weighting differences in which α undersamples τ. Note that N has no intrinsic dependence on the dimension of τ.

For the basic version of the algorithm (or when \(\left|\alpha \right\rangle\) is the uniform superposition), Eq. (8) can be simplified even further to

where \({p}_{\,{{\mbox{coll}}}\,}^{(\tau )}={\sum }_{x}{\left|{\tau }_{x}\right|}^{4}\) is the collision probability of the classical distribution induced by \(\left|\tau \right\rangle\). \(1/{p}_{\,{{\mbox{coll}}}\,}^{(\tau )}\) may be interpreted as the effective support size deff of \(\left|\tau \right\rangle\). It follows that the basic algorithm is efficient so long as deff/d is at least 1/poly(n), that is, so long as the effective support of \(\left|\tau \right\rangle\) is not too small. This makes the proposed method complementary to existing methods which are efficient for concentrated distributions. For a slightly different perspective, the factor \(d{p}_{\,{{\mbox{coll}}}\,}^{(\tau )}\) can be written as \({2}^{n-{H}_{2}^{(\tau )}}\) where \({H}_{2}^{(\tau )}\) is the Rényi 2-entropy of the classical distribution induced by \(\left|\tau \right\rangle\). Thus the basic method is efficient when the entropy is large, namely, when \(n-{H}_{2}^{(\tau )}\) grows at most logarithmically in n.

Using standard calculus one can show that the optimal sampling distribution satisfies

where \(\left|\sigma \right\rangle\) is the normalized projection of \(\left|\varepsilon \right\rangle\) onto the space orthogonal to \(\left|\tau \right\rangle\). One might have guessed that it would be sufficient for \(\left|\alpha \right\rangle\) to sample either \(\left|\mu \right\rangle\) or \(\left|\tau \right\rangle\) well. But that is incorrect: if \(\left|\alpha \right\rangle\) doesn’t frequently sample the components of \(\left|\mu \right\rangle\) with the largest errors (whether or not the components themselves are large), then the (in)fidelity will not be estimated with high precision.

The prospect of calculating the target amplitudes after the circuits are run, using a random state in place of \(\left|{r}_{yx}\right\rangle\) and performing postselection, is considered in Supplementary Material 1.4. There it is found that using postselection instead of feedforward increases the number of needed circuit runs by a large (but dimension-independent) factor. Improving that bound, or finding an alternative postselection scheme that does not incur so much overhead, is a direction for future work.

Robustness to error in the auxiliary state

A key assumption in the general version of EVAQS is that the auxiliary state \(\left|\alpha \right\rangle\) is well-characterized. Fortunately, EVAQS is robust with respect to this assumption in the sense that small error in the knowledge of \(\left|\alpha \right\rangle\) leads to a correspondingly small error in the estimate of F(μ, τ).

Suppose \(\left|\alpha \right\rangle\) is mistakenly characterized as \(\left|\tilde{\alpha }\right\rangle\). Then as shown in Section 4.3, instead of estimating F(μ, τ) the procedure estimates \(F(\mu ,\tilde{\tau })\) where \(\tilde{\tau }\) is a perturbation of τ. Intuitively, if \(\left|\tilde{\alpha }\right\rangle\) is close to \(\left|\alpha \right\rangle\) then \(\left|\tilde{\tau }\right\rangle\) will be close to \(\left|\tau \right\rangle\) and \(F(\mu ,\tilde{\tau })\) will be close to F(μ, τ). In Section 4.3 and Supplementary Material 1.3 it is shown that

where δrms is the average relative error in the amplitudes of \(\left|\tilde{\alpha }\right\rangle\). Thus a small error in the characterization of \(\left|\alpha \right\rangle\) yields a correspondingly small error in the estimate of F(μ, τ).

Simulations

In this section I present the results of several simulation studies demonstrating the validity and efficacy of the proposed method. The first study demonstrates scalable verification of so-called instantaneous quantum polynomial (IQP) circuits20. The next two studies demonstrate sample-efficient verification of random quantum circuits, including the kind of circuits used to demonstrate quantum supremacy5. In each of these studies the basic version of the method (without an auxiliary state \(\left|\alpha \right\rangle\)) was employed.

Verification of IQP circuits

IQP circuits are currently of interest as a family of relatively simple quantum circuits whose output distributions are hard to simulate classically21,22. IQP circuits are well-suited for demonstrating EVAQS as their outputs are typically anticoncentrated in the computational basis. Even better, if the output of an IQP circuit is transformed into the Hadamard basis, the distribution is not only perfectly uniform (yielding the lowest possible sample complexity), but also easy to calculate on a classical computer. This makes EVAQS a fully scalable way to verify IQP circuits.

An n-qubit IQP circuit of depth m can be defined as a set of m multiqubit X rotations acting on the \({\left|0\right\rangle }^{n}\) state. A multiqubit NOT operation may be written as \({X}^{a}\equiv {X}_{1}^{{a}_{1}}\otimes \cdots \otimes {X}_{n}^{{a}_{n}}\) for a ∈ {0, 1}n. In terms of such operators, an IQP circuit has the form

for some set of vectors A1, …, Am ∈ {0, 1}n. The amplitudes of the output state can be written concisely as

where A = [A1, …, Am] and

The number of terms in ∑v:Av=x is 2m−r where r = rank(A). Since r ≤ n, the number of terms contributing to τx is exponential in the circuit depth m once it exceeds n.

IQP states are substantially easier to analyze in the Hadamard basis. Let \(\left|\xi \right\rangle ={H}^{\otimes n}\left|\tau \right\rangle\). Note that it is experimentally easy to obtain \(\left|\xi \right\rangle\) from \(\left|\tau \right\rangle\). Since HX = ZH, we have

where \(\left|+\right\rangle \equiv (\left|0\right\rangle +\left|1\right\rangle )/\sqrt{2}=H\left|0\right\rangle\). In this basis, the amplitude

is trivial to compute classically. Furthermore, the induced probability distribution is uniform, which is the best case for EVAQS.

As a first demonstration, I simulated the verification of random IQP circuits in the Hadamard basis. The test circuits were comprised of n = 4, 6, 8, …, 20 qubits and m = 3n rotations; the depth m = 3n was chosen to ensure that the complexity of the output state is exponential in n. For each rotation, a random subset of qubits was chosen from n Bernoulli trials such that on average 2 qubits were involved in each rotation. Each rotation angle was chosen uniformly from [0, 2π]. To simulate circuit error, each angle θi was perturbed by a small random amount δi. The angle errors were globally scaled so that the resulting state \(\left|\mu \right\rangle\) had a prescribed infidelity I with respect to the ideal state. For each n and each I ∈ {0.01, 0.03, 0.1, 0.3}, 400 random perturbed circuits were realized. For each circuit, the verification procedure was performed with 104 simulated measurements.

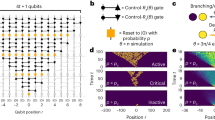

Figure 2 a shows the estimated infidelities obtained from these simulated experiments. (In all the figures, a solid line shows the median value among all realizations of a given experiment and a surrounding shaded band shows the 10th–90th percentiles). As expected, the proposed method is able to accurately estimate the infidelity of the prepared state independent of the number of qubits over a wide range of infidelities. With a fixed number of measurements, the states with smaller infidelity are estimated with larger relative error; however, the absolute error is actually smaller, in accordance with Eq. (9). Figure 2b shows the sample cost of the procedure, given by Eq. (8) and normalized by the desired precision ϵ2, as a function of the number of qubits. Notably, the cost is independent of the number of qubits, depending only on the fidelity of the test state. Again, this is expected from Eq. (9) given that the output distribution is uniform.

EVAQS is also effective when measurements are performed in the computational basis. In this basis, the output state of a typical IQP circuit is anticoncentrated in the sense that significant fraction of the basis states have probabilities of order 2−n or larger23. Figure 3a shows the estimated infidelities for the same set of circuits as described in the previous subsection, but this time using simulated measurements in the computational basis. As before, EVAQS was able to accurately estimate the circuit fidelities. This time, however, the cost tends to increase slowly with the number of qubits. I note that while the median cost does appear to grow exponentially, in going from 4 to 20 qubits it increases only by a factor of about 2.5, whereas the size of the state being verified increases by a factor of 220/24 = 65536. Furthermore, there is noticeable variation in cost for circuits of the same size (Fig. 3b). This is because different random circuits of the same size were anticoncentrated to different degrees. The strong link between cost and the degree of anticoncentration in the target distribution is shown in Fig. 3c. Indeed, the degree of concentration (as measured by the inverse collision probability) is a better predictor of cost than the number of qubits. Also noteworthy is the fact that the estimated costs, given by Eq. (9) and shown as dashed lines, are within a small factor of the true costs.

a Estimated infidelity. b Precision-normalized cost. c Cost as a function of the concentratedness of the output state. The dashed lines are the estimated cost, Eq. (8).

Verification of random circuits

The second study involves verification of random quantum circuits, that is, sequences of random 2-qubit unitaries on randomly selected pairs of qubits. Each random unitary was obtained by generating a random complex matrix with normally-distributed elements, then performing Gram-Schmidt orthogonalization on the columns of the matrix. In this study, error was modeled as a perturbation of the output state rather than perturbation of the individual gates. The output state was written as

where \(\left|\varepsilon \right\rangle\) consisted of both multiplicative and additive noise,

where \({\xi }_{x}^{\prime},{\xi }_{x}^{^{\prime\prime} }\) are independent complex Gaussian random variables. The constant λ was chosen so that the standard deviations of the multiplicative error and additive error are equal when \(\left|{\tau }_{x}\right|\) equals its mean value. The constant η was then chosen to yield a particular infidelity I. As before, circuits were comprised of n = 4, 6, 8, …, 20 qubits and m = 3n gates. For each n and I ∈ {0.01, 0.03, 0.1, 0.3}, 300 random circuits were realized. For each circuit, the verification procedure was performed with 104 simulated measurements.

The results are shown in Fig. 4. Again, EVAQS is able to estimate the output state fidelity accurately with a number of measurements that grows very slowly with the number of qubits. And as with IQP circuits, the cost is well-predicted by the concentration of the target state and the infidelity of the unknown state.

a Estimated infidelity. b Precision-normalized cost. c Cost as a function of the concentratedness of the output state. The dashed lines are the estimated cost, Eq. (8).

Verification of supremacy circuits

Another important class of circuits is that recently used to demonstrate the quantum supremacy of a quantum processor5. Such circuits consist of alternating rounds of single-qubit rotations drawn from a small discrete set and entangling operations on adjacent pairs of qubits in a particular pattern. Like IQP circuits, such circuits are hard to classically simulate24,25 in spite of their locality constraints. But unlike IQP circuits, they are universal for quantum computing.

The circuits simulated in this study consisted of n ∈ {4, 9, 12, 16, 20} qubits arranged in a planar square lattice with (nearly) equal sides and 16 cycles of alternating single-qubit operations and entangling operations, as described in ref. 5. Single-qubit error was modeled as a post-operation unitary of the form \(\exp \left({{{\rm{i}}}}\left({\varepsilon }_{x}X+{\varepsilon }_{y}Y+{\varepsilon }_{z}Z\right.\right)\) where εx, εy, εz are independent normally-distributed variables of zero mean and small variance. Error on the two-qubit operations was modeled as a small random perturbation of the angles θ, ϕ parameterizing the entangling gate5. The amount of error was chosen to yield a process infidelity26 on the order of 0.02% per single-qubit operation and 0.2% per two-qubit operation. For each circuit size, 100 random noisy circuits were generated; for each circuit, 104 measurements were simulated.

Figure 5 plots the estimated fidelity vs. the true infidelity of all the circuits simulated. For comparison, the dashed line shows the true infidelity. The smallest circuits (n = 4) had output infidelities on the order of 10−3, while the largest (n = 20) had infidelities around 0.3. Over this range, the infidelity was estimated to within 20% or better. What is not evident from the plot is that the variance of the estimator varied by an order of magnitude for different random circuits of the same size, due to the different amounts of entropy in their output distributions. Consequently, the expected error for some of the circuits is actually considerably smaller than 20%. For the circuits that were verified less accurately, the expected error could be reduced further by increasing the number of measurements. Interestingly, the relative error does not vary much over the wide range of circuit sizes and circuit infidelities in these simulations. According to Eq. (9), one expects the relative error to scale as \(\sqrt{{{{\rm{Var}}}}\tilde{F}}/I\propto {I}^{-1/2}\), that is, to increase as infidelity decreases. Additional simulations confirmed that this scaling does occur with smaller gate errors.

Comparison to other verification methods

To help place these results in context, this section compares and contrasts EVAQS with several leading methods of quantum state verification.

Direct fidelity estimation

One of the first scalable methods for quantum state verification, called direct fidelity estimation, was introduced in refs. 12,13. Like EVAQS, it addresses the problem of estimating the fidelity F(μ, τ) between an arbitrary quantum state μ and a classically-specified pure target state τ. The density operators μ and τ are expanded in an operator basis (τ explicitly, μ formally) leading to a formal expansion of the fidelity function F(μ, τ) in this basis. The fidelity is approximated by selecting a random subset of terms from the expansion, experimentally estimating their coefficients, and computing their weighted sum.

Like EVAQS, direct fidelity estimation requires a generally costly classical calculation of the coefficients of τ in some basis. Both methods also utilize importance sampling, though in direct fidelity estimation the sampling is done classically whereas in EVAQS a quantum state is used for this purpose. The main difference between the two methods is the regime of experimental efficiency. For direct fidelity estimation the number of samples to estimate F to fixed accuracy scales as \(O(\left|S\right|/{2}^{n})\) where \(\left|S\right|\) is the number of non-zero terms in the operator expansion of τ (see Supplementary Material section 1.5). Since the number of basis operators is 4n, the method is efficient only if the fraction of non-zero terms is poly(n)/2n, i.e., exponentially small. That is, direct fidelity estimation is efficient for target states τ that are sparse in the chosen operator basis, whereas EVAQS is most efficient for states that are anticoncentrated in the chosen state vector basis.

Heavy output testing

Recent efforts in benchmarking quantum computers have led to several related methods for verifying quantum computer outputs. The two most notable of these are the cross-entropy benchmark used for demonstrating quantum supremacy27 and the heavy output criteria used in calculating quantum volume28. The mathematical details differ, but the key principles are the same in both contexts: a quantum circuit is devised to prepare a state that induces a complicated probability distribution—the target distribution—in the computational basis. The circuit is executed and measured many times on a quantum computer under test. Under the premise that generating high-probability samples (so-called heavy outputs) from the target distribution is a difficult task24,27, the target probabilities of the measured outcomes are calculated on a classical computer and translated into a score: the higher the target probabilities, the better the score.

Like EVAQS, heavy output testing is experimentally efficient for states that are anticoncentrated in the computational basis; the number of required samples goes as O(ε−2), independent of the number of qubits. Also like EVAQS, it requires a costly evaluation of the target output coefficients on a classical computer. The main difference between the two approaches is that EVAQS provides a direct estimate of the fidelity of the quantum state in question, whereas heavy output testing strictly provides only indirect evidence of the state’s accuracy. Indeed, the best heavy output score is obtained not by preparing the target distribution, but by outputting the most likely element of τ every time. Furthermore, the heavy output score is blind to phase errors in the amplitudes of the prepared quantum state. A counterpoint is that the heavy output score has been shown to be quite sensitive to typical circuit errors27. That is, errors almost always make the heavy output score noticeably worse. Thus if one is willing to make a strong non-adversarial assumption about the errors on the quantum state in question, heavy output testing is a comparably effective way to estimate the state’s accuracy.

Shadow tomography

Very recently Huang et al. introduced a type of randomized tomography that enables low-rank projections of arbitrary quantum states (e.g., fidelity) to be estimated efficiently16. In the most comparable form of their method, the unknown state μ is measured in a set of random bases, which is accomplished by applying random global Clifford operations to μ and measuring in the computational basis. The measurement bases and observed outcomes are used to classically compute a state \(\tilde{\mu }\), called a classical shadow, to serve as a proxy for μ. That is, properties of μ are estimated by corresponding properties of \(\tilde{\mu }\). For example, \(F(\mu ,\tau )=\left\langle \tau \right|\mu \left|\tau \right\rangle\) is estimated by \(F(\tilde{\mu },\tau )=\left\langle \tau \right|\tilde{\mu }\left|\tau \right\rangle\). Crucially, the measurement bases are chosen so that \(\tilde{\mu }\) and its properties can be efficiently calculated on a classical computer. The success of this approach is rather remarkable: the classical shadow \(\tilde{\mu }\) is generally not a good holistic approximation of μ; it is usually not even physical! (In the common case that the Hilbert space dimension d significantly exceeds the number of observations, most of the eigenvalues of the classical shadow are negative). Nevertheless, it allows one to efficiently estimate observables that have small operator norm, such as fidelity.

Shadow tomography is a general characterization method, not just a verification method, and its efficiency evidently does not depend on the sparsity of the target state. But as acknowledged in ref. 16, the global Clifford operations needed for shadow tomography are non-trivial to implement. In contrast, the quantum circuits used for EVAQS are very simple. For the task of fidelity estimation, both EVAQS and shadow tomography require calculation of the target state on a classical computer. But whereas shadow tomography evidently requires a substantial portion of the target state to be calculated, EVAQS requires only a small fraction of the target state to be calculated. On the other hand, in EVAQS the results of such calculations must be available on demand for a feed-forward measurement. As the two methods appear to provide different tradeoffs in classical and quantum complexity, it is plausible that different scenarios may favor different methods.

Discussion

The verification of complex states produced by quantum computers presents daunting experimental and computational challenges. The state verification method presented here, EVAQS, takes a significant step in addressing these challenges. In contrast to most existing verification methods, EVAQS is inherently sample-efficient when the target state is anticoncentrated (i.e., has high entropy) in the chosen measurement basis. In the case that the target state is not anticoncentrated, an auxiliary state may be used to importance sample the unknown state, greatly reducing the number of measurements needed.

The main limitation of EVAQS is the need to calculate selected probability amplitudes of the target state. At a certain level this seems unavoidable: to verify a quantum state against a classical specification, at least some characteristic features of the target state must be calculated. In the hope of reducing the classical computational complexity in at least in some cases, the method was designed so that the calculated amplitudes need not be normalized. But the general computational challenge of quantum state verification remains an important direction for future work.

A related issue is that the most efficient implementation of EVAQS involves feedforward operation of the quantum computer. While such a feature is anticipated to be available on some devices in the near future, the most obvious workaround involving postselection appears to incur significant cost. Efforts are currently underway to devise a variant of EVAQS that replaces the feedforward aspect with post-calculated amplitudes and postselection without incurring a large overhead.

EVAQS complements previously known verification methods that are efficient when the target state is sparse in some readily measurable basis. However, there exist interesting quantum states that are neither sparse nor anticoncentrated; for example, coherent analogs of thermal states at moderate temperatures. Such a state can have an effective support that is exponentially large (making it challenging for sparse methods) but still exponentially smaller than the number of basis states. Furthermore, such a state is unlikely to be importance-sampled well by any auxiliary state that is easy to make (otherwise it would not be such an interesting state). Thus although importance sampling can reduce the cost of EVAQS considerably for such intermediate density states, the most interesting of these are likely to remain challenging to verify. Other approaches, perhaps yet to be discovered, will be needed to efficiently verify such states.

Methods

Proof of correctness

To show that the procedures described in Section “The EVAQS Algorithm” indeed yield an estimate of F(μ, τ), we consider the more general version; the correctness of the simpler version will subsequently be established as a special case.

Proof of the general version

In each iteration of the general version of the algorithm, one first prepares the test register, auxiliary register, and the first ancilla qubit in the state

In the second step, the ancilla controls a swap between the test and auxiliary registers. This yields the state

In the third step the test and auxiliary registers are measured, yielding values x, y. This projects ancilla 1 onto the unnormalized state

In the fourth step, the observed values x, y are used to compute \({\tau }_{x}^{\prime},{\tau }_{y}^{\prime},{\alpha }_{x}^{\prime},{\alpha }_{y}^{\prime}\) and prepare ancilla qubit 2 in the state

Let \(\lambda ={\left|{\tau }_{x}^{\prime}/{\tau }_{x}\right|}^{2}/{\left|{\alpha }_{x}^{\prime}/{\alpha }_{x}\right|}^{2}\), which is independent of x. Then \(\left|{r}_{yx}\right\rangle\) can be written as

where

The joint state of the two ancillas is

Finally, the ancillas are measured in the Bell basis. Since

the probability of joint outcome (x, y, b = ± 1) is

Using \({\left|\mathop{\sum}\limits_{x}{\mu }_{x}^{* }{\tau }_{x}\right|}^{2}=F(\mu ,\tau )\) we obtain

Now, \({p}_{xy+}+{p}_{xy-}=\mathop{\sum}\nolimits_{b\in \{-1,0,1\}}{p}_{xyb}{b}^{2}\) and \({p}_{xy+}-{p}_{xy-}=\mathop{\sum}\nolimits_{b\in \{-1,0,1\}}{p}_{xyb}b\). Thus

and

It follows that

To obtain an experimental estimate of F(μ, τ), the steps above are repeated N ≫ 1 times. Let xi, yi, bi denote the values of x, y, b obtained in the ith trial. The experimental quantities (5) and (6) are unbiased estimators of \(\langle {w}_{xy}^{\prime}b\rangle\) and \(\langle {w}_{xy}^{\prime}{b}^{2}\rangle\), respectively. As a first approximation F may be estimated by the ratio \(\tilde{A}/\tilde{B}\). It is a basic result of statistical analysis that such an estimator has a bias of order N−1. The estimator which corrects for this bias is derived in Supplementary Material 1.1.

Proof of the basic version

To establish the correctness of the basic version of the algorithm, I show that it is equivalent to performing the general algorithm with \(\left|\alpha \right\rangle\) as the uniform superposition state.

In the basic version, one starts with just the unknown state \(\left|\mu \right\rangle\) and an ancilla qubit in the state \((\left|0\right\rangle +\left|1\right\rangle )/\sqrt{2}\). One picks a uniform random vector v ∈ {0, 1}n and performs

yielding the state

Measuring x yields the ancilla state

with net probability

Now, consider the general algorithm with \(\left|\alpha \right\rangle ={2}^{-n/2}{\sum }_{y}\left|y\right\rangle\). From Eq. (22), the state immediately following the controlled swap between test and auxiliary registers is

Measurement of x, y yields the ancilla state

with probability

Equations (45), (46) with y = x ⊕ v are the same as (42), (43). Thus, the basic version of the algorithm is equivalent to the general version with a uniform superposition for \(\left|\alpha \right\rangle\).

Validity for mixed input states

So far it has been supposed that μ is a pure state. Here I show that the proposed method also works when μ is mixed. Recall that an arbitrary state μ may be generally be written as

where each \({\mu }^{(i)}=\left|{\mu }^{(i)}\right\rangle \left\langle {\mu }^{(i)}\right|\) is a pure state and q = (q1, …, qd) is a discrete probability distribution. Since expectation values of quantum observables are linear in the density operator, the experimental quantities \(\tilde{A}\) and \(\tilde{B}\) (eqs. (5), (6)) have expectation values

where \({\left\langle \cdots \right\rangle }_{\rho }\) denotes the expectation value according to density operator ρ. Now, since B does not depend on μ, \({\left\langle \tilde{B}\right\rangle }_{{\mu }^{(i)}}={\left\langle \tilde{B}\right\rangle }_{\mu }\). Then the expectation value of the simple estimator (4) is

The last line follows from the linearity of F( ⋯ , τ) when τ is pure.

Derivation of the variance

The cost of EVAQS is driven by the number of samples needed to obtain an estimate with sufficiently small variance. In Supplementary Material 1.2 is shown that, for pure μ and to lowest order in statistical fluctuations,

where

In a typical application it is expected that μ is not a bad approximation of τ; thus the regime of interest is that of small infidelity I ≡ 1 − F. We proceed to simplify Qx for the case that the infidelity I ≡ 1 − F is small, keeping only the lowest order terms. Let \(\left\langle \tau | \mu \right\rangle ={e}^{{{{\rm{i}}}}\phi }\cos \theta\). Then \(F={\cos }^{2}\theta\), \(I={\sin }^{2}\theta\), and 1 + F2 ≈ 2F. This yields

Now, \(\left|\mu \right\rangle\) can be written as \(\left|\mu \right\rangle ={e}^{{{{\rm{i}}}}\phi }(\left|\tau \right\rangle \cos \theta +\left|\sigma \right\rangle \sin \theta )\) where \(\left\langle \sigma | \sigma \right\rangle =1\) and \(\left\langle \sigma | \tau \right\rangle =0\). Then \({\tau }_{x}^{* }{\mu }_{x}{e}^{-{{{\rm{i}}}}\phi }={\left|{\tau }_{x}\right|}^{2}\cos \theta +{\tau }_{x}^{* }{\sigma }_{x}\sin \theta\). To lowest order in \(\sin \theta =\sqrt{I}\),

Substituting these expressions into (56) and combining terms yields

This yields

To obtain Eq. (7) the above expression for \(\left|\mu \right\rangle\) is substituted into \(\left|\varepsilon \right\rangle \equiv {e}^{-{{{\rm{i}}}}\phi }\left|\mu \right\rangle -\left|\tau \right\rangle\), giving

Since \((1-\left|\tau \right\rangle \left\langle \tau \right|)\left|\varepsilon \right\rangle =\left|\sigma \right\rangle \sin \theta\), \(\left|\sigma \right\rangle\) can be understood as the normalized projection of \(\left|\varepsilon \right\rangle\) onto the subspace orthogonal to \(\left|\tau \right\rangle\). Alternatively, we may use the fact that \(\sin \theta =\sqrt{1-F}=\sqrt{I}\) and \(\cos \theta =\sqrt{F}\approx 1-\frac{1}{2}I\) to obtain

Equation (7) follows from substituting this expression into (60).

In the case that μ is mixed with eigenvector decomposition \(\mu ={\sum }_{i}{q}_{i}\left|{\mu }^{(i)}\right\rangle \left\langle {\mu }^{(i)}\right|\), Eq. (54) generalizes to

where Q(i) is defined analogously to Q but with \(\left|{\mu }^{(i)}\right\rangle\) in place of \(\left|\mu \right\rangle\). Then in the high-fidelity regime we obtain

where \(\left|{\varepsilon }^{(i)}\right\rangle\) is the error vector associated with \(\left|{\mu }^{(i)}\right\rangle\). Note that \({\sum }_{i}{q}_{i}{|{\varepsilon }_{x}^{(i)}|}^{2}\) may be interpreted as the total amount of error on the x component of μ. Assuming this total error is distributed non-adversarially, we obtain the same scaling rule as for the pure state case, Eq. (8).

Derivation of the robustness bound

Suppose \(\left|\alpha \right\rangle\) is mischaracterized as \(\left|\tilde{\alpha }\right\rangle\). Then upon measuring x, y one is led to prepare the ancilla state

where \(\tilde{w}\) is defined in the same way as w but using the coefficients of \(\left|\tilde{\alpha }\right\rangle\) instead of those of \(\left|\alpha \right\rangle\). Equation (28) then becomes

A derivation similar to that of 4.1 yields

where \(\tilde{\tau }=\left|\tilde{\tau }\right\rangle \left\langle \tilde{\tau }\right|\) has state vector amplitudes

The construction (4) then yields an estimate of \(F(\mu ,\tilde{\tau })\). That is, error in one’s knowledge of the auxiliary state \(\left|\alpha \right\rangle\) causes the algorithm to estimate the fidelity of μ with respect to a perturbed version of the target state. Intuitively, if \(\left|\tilde{\alpha }\right\rangle\) is close to \(\left|\alpha \right\rangle\) then \(\left|\tilde{\tau }\right\rangle\) will be close to \(\left|\tau \right\rangle\) and \(F(\mu ,\tilde{\tau })\) will be close to F(μ, τ). To make this more precise we use the triangle inequality for the Bures angle \({\theta }_{\alpha \beta }\equiv \arccos \sqrt{F(\alpha ,\beta )}\):

Using the fact \(\left|{\theta }_{\tau \tilde{\tau }}\right|\le \pi /2\) and combining the inequality above with the trigonometric identity

yields

In Supplementary Material 1.3 it is shown that

where δrms is the average relative error of the amplitudes of \(\left|\tilde{\alpha }\right\rangle\) defined as

The bound (11) immediately follows.

Data availability

Computer code and data used in this work are available from the author on request.

References

Georgescu, I. M., Ashhab, S. & Nori, F. Quantum simulation. Rev. Mod. Phys. 86, 153–185 (2014).

Tacchino, F., Chiesa, A., Carretta, S. & Gerace, D. Quantum computers as universal quantum simulators: state-of-the-art and perspectives. Adv. Quantum Technol. 3, 1900052 (2020).

Biamonte, J. et al. Quantum machine learning. Nature 549, 195–202 (2017).

Benedetti, M., Lloyd, E., Sack, S. & Fiorentini, M. Parameterized quantum circuits as machine learning models. Quantum Sci. Technol. 4, 043001 (2019).

Arute, F. et al. Quantum supremacy using a programmable superconducting processor. Nature 574, 505–510 (2019).

Buhrman, H., Cleve, R., Watrous, J. & de Wolf, R. Quantum fingerprinting. Phys. Rev. Lett. 87, 167902 (2001).

Shabani, A. et al. Efficient measurement of quantum dynamics via compressive sensing. Phys. Rev. Lett. 106, 100401 (2011).

Jiying, L., Jubo, Z., Chuan, L. & Shisheng, H. High-quality quantum-imaging algorithm and experiment based on compressive sensing. Opt. Lett. 35, 1206 (2010).

Howland, G. A., Knarr, S. H., Schneeloch, J., Lum, D. J. & Howell, J. C. Compressively characterizing high-dimensional entangled states with complementary, random filtering. Phys. Rev. X 6, 021018 (2016).

Ahn, D. et al. Adaptive compressive tomography with no a priori information. Phys. Rev. Lett. 122, 100404 (2019).

Bairey, E., Arad, I. & Lindner, N. H. Learning a local hamiltonian from local measurements. Phys. Rev. Lett. 122, 020504 (2019).

Flammia, S. T. & Liu, Y.-K. Direct fidelity estimation from few pauli measurements. Phys. Rev. Lett. 106, 230501 (2011).

da Silva, M. P., Landon-Cardinal, O. & Poulin, D. Practical characterization of quantum devices without tomography. Phys. Rev. Lett. 107, 210404 (2011).

Wehden, K., Faro, I. & Gambetta, J. IBM’s roadmap for building an open quantum software ecosystem (2021).

Valiant, G. & Valiant, P. An Automatic Inequality Prover and Instance Optimal Identity Testing. In 2014 IEEE 55th Annual Symposium on Foundations of Computer Science, 51–60 (2014).

Huang, H.-Y., Kueng, R. & Preskill, J. Predicting many properties of a quantum system from very few measurements. Nat. Phys. 16, 1050–1057 (2020).

Buhrman, H. et al. New Limits on Fault-Tolerant Quantum Computation. In 2006 47th Annual IEEE Symposium on Foundations of Computer Science (FOCS’06), 411–419 (IEEE, Berkeley, CA, USA, 2006).

Smolin, J. A. & DiVincenzo, D. P. Five two-bit quantum gates are sufficient to implement the quantum Fredkin gate. Phys. Rev. A 53, 2855–2856 (1996).

Hung, W., Xiaoyu, S., Guowu, Y., Jin, Y. & Perkowski, M. Optimal synthesis of multiple output Boolean functions using a set of quantum gates by symbolic reachability analysis. IEEE Trans. Comput. -Aided Des. Integr. Circuits Syst. 25, 1652–1663 (2006).

Shepherd, D. & Bremner, M. J. Instantaneous quantum computation. Proc. R. Soc. A 465, 1413–1439 (2009).

Bremner, M. J., Jozsa, R. & Shepherd, D. J. Classical simulation of commuting quantum computations implies collapse of the polynomial hierarchy. Proc. R. Soc. A 467, 459–472 (2011).

Bremner, M. J., Montanaro, A. & Shepherd, D. J. Average-case complexity versus approximate simulation of commuting quantum computations. Phys. Rev. Lett. 117, 080501 (2016).

Hangleiter, D., Kliesch, M., Eisert, J. & Gogolin, C. Sample complexity of device-independently certified "Quantum Supremacy”. Phys. Rev. Lett. 122, 210502 (2019).

Aaronson, S. & Chen, L. Complexity-theoretic foundations of quantum supremacy experiments. In Proceedings of the 32nd Computational Complexity Conference, CCC ’17, 1–67 (Schloss Dagstuhl–Leibniz-Zentrum fuer Informatik, Dagstuhl, DEU, 2017).

Aaronson, S. & Gunn, S. On the classical hardness of spoofing linear cross-entropy benchmarking. Theory Comput. 16, 1–8 (2020).

Gilchrist, A., Langford, N. K. & Nielsen, M. A. Distance measures to compare real and ideal quantum processes. Phys. Rev. A 71, 062310 (2005).

Boixo, S. et al. Characterizing quantum supremacy in near-term devices. Nat. Phys. 14, 595–600 (2018).

Cross, A. W., Bishop, L. S., Sheldon, S., Nation, P. D. & Gambetta, J. M. Validating quantum computers using randomized model circuits. Phys. Rev. A 100, 032328 (2019).

Acknowledgements

This work was performed at Oak Ridge National Laboratory, operated by UT-Battelle, LLC under contract DE-AC05-00OR22725 for the US Department of Energy (DOE). Support for the work came from the DOE Advanced Scientific Computing Research (ASCR) Quantum Testbed Pathfinder Program under field work proposal ERKJ332.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

R.S.B. authored this paper and performed all the work described in it.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The author declares no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons license and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Bennink, R.S. Efficient verification of anticoncentrated quantum states. npj Quantum Inf 7, 127 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41534-021-00455-6

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41534-021-00455-6

This article is cited by

-

A probabilistic model of quantum states for classical data security

Frontiers of Physics (2023)