Abstract

Diffusion noise is a major source of spectral line broadening in liquid state nano-scale nuclear magnetic resonance with shallow nitrogen-vacancy centres, whose main consequence is a limited spectral resolution. This limitation arises by virtue of the widely accepted assumption that nuclear spin signal correlations decay exponentially in nano-NMR. However, a more accurate analysis of diffusion shows that correlations survive for a longer time due to a power-law scaling, yielding the possibility for improved resolution and altering our understanding of diffusion at the nano-scale. Nevertheless, such behaviour remains to be demonstrated in experiments. Using three different experimental setups and disparate measurement techniques, we present overwhelming evidence of power-law decay of correlations. These result in sharp-peaked spectral lines, for which diffusion broadening need not be a limitation to resolution.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Nuclear magnetic resonance (NMR) spectroscopy is widely used in the life and material sciences. However, classical NMR techniques are not readily available on the single cell level. Therefore, further scientific breakthrough in biosensing may be hindered by the invasive analysis techniques that most conventional approaches require in this regime. Existing methodologies entail tagging, e.g., with fluorescent nano-particles, cryogenic temperatures, or high-magnetic fields1,2,3,4,5. Either causes substantial modifications to the sample, meaning that its natural properties cannot be determined accurately. Nuclear magnetic resonance at the nano-scale (nano-NMR) with spin sensors, such as nitrogen-vacancy (NV) centres, offers a label-free, room temperature approach capable of studying biologically relevant samples down to the molecular level without altering their properties6,7,8,9. NV centres have already been shown capable of detecting the magnetic field created by nano-sized distributions of nuclei in liquid samples at ambient temperature4,10,11,12,13,14. However, a fundamental limitation to the ability of resolving spectral lines is thought to exist.

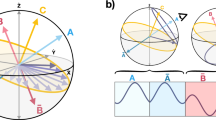

The nano-NMR approach with spin sensors relies on nano-scale sample sizes containing a sufficiently low number of nuclei, in which statistical fluctuations are significant enough to overcome the thermal averaging of nuclei orientation, leading to the emergence of time-correlated magnetic fields without resorting to sample polarisation. These fields can be detected at room temperature with quantum probes such as a shallow NV centre, whose interaction region is typically considered a hemisphere with a radius of the order of the NV depth as shown in Fig. 1b4,15,16,17. Sample sizes within the NV detection region are on the order of 10−24 − 10−20 L for several nm deep NV centres. There, the statistical polarisation exceeds the thermal by more than three orders of magnitude in ambient conditions10,18,19,20,21,22. Statistically polarised nano-NMR with spin sensors enables studying sample properties inaccessible with any other NMR protocol.

(a) Level scheme of the NV centre. (b) The NV centre is located at a depth d below the diamond surface. In the standard diffusion model a hemisphere sensing volume (blue) of radius ~ d is considered, in which the nuclei interact with the NV centre. Alternatively, we accurately take into account the 1/r3 dependence of the dipole–dipole interaction. The colour intensity of the orange hemisphere indicates the interaction strength of the nuclear spins (red) with the NV centre. (c) Decay of the auto-correlation according to the exponential and the power-law model. With the accurate dipole–dipole model, decay is (nearly) exponential for short times (t ≪ TD) and a power-law for t ≫ TD with TD the characteristic diffusion time. (d) Power spectrum of the NMR signal. The power-law model shows a distinct, sharp peak whereas the exponential model resembles a Lorentzian lineshape.

The main challenge for nano-NMR with statistically polarised liquid samples is posed by the diffusion of molecules out of the interaction region defined by the probe. Diffusion changes the spatial distribution of statistical polarisation, and leads to a decay of the correlations of the magnetic field signal in the probe, which is typically considered exponential (see Fig. 1c)16,23. Then, measurements performed beyond the characteristic time of the exponential decay yield no information about the spectral signatures of interest. When this time is short, not enough information can be gathered to allow for spectral reconstruction in post-processing24, creating a resolution problem. The corresponding spectral line for correlations with exponential decay is Lorentzian, as shown in Fig. 1d, where frequency resolution is typically defined by its full width at half maximum25,26,27.

Recent theoretical analysis has claimed that diffusion induced decay of correlations follows a power-law at long times (see Fig. 1c), due to the specific dipole–dipole interaction of the shallow NV centre sensors and the nuclei in the sample28. Such correlations allow suitable measurement protocols to extract sufficient information beyond the characteristic decay time TD, so estimating frequencies smaller than 1/TD becomes feasible24. Moreover, they provide a more accurate route to measure the diffusion coefficient in liquid samples. Although previous work in liquid NV nano-NMR has shown an instance where a non-exponential function fits better the observed correlation, this was attributed to surface effects that led to reduced translational diffusion of the nuclei close to the surface15. Thus, experimental evidence of interaction dependent power-law behaviour has not been demonstrated yet, to the best of our knowledge. The main reason might be that the early time decay of correlations resembles an exponential function, and it is only the long-time decay beyond the diffusion time that is critical to show deviations from the exponential paradigm29.

In this work, we provide compelling experimental evidence of a power-law decay of correlations at long times, in accordance with the theoretical prediction in ref. 28. We demonstrate our results using three distinct measurement settings and several independent statistical analysis tools. We include measurements of the magnetic field originated in the fluorine nuclear spins of the sample in one of the experiments. These nuclei are assumed to be separated from the diamond surface by an immobilised proton layer adsorbed onto the surface, and permit us to rule out surface effects as the source of a long correlation tail15. Our results pave the way for statistically polarised, room temperature nano-NMR experiments with biomedically relevant samples, with a scope that is not limited to NV centres but that, due to the power-law scaling stemming from dipole–dipole coupling, extends to any sensor that is based on such interactions.

Results

Theory

The NV centre is a point defect in the diamond lattice composed of a substitutional nitrogen atom and an adjacent vacancy which, together, are described as a system whose ground state is a 3A2 spin triplet. Applying a bias magnetic field, the degeneracy of the \(\left|{m}_{s}=\pm 1\right\rangle\) spin levels is lifted, and the NV centre can be used as an effective two-level system, as shown in Fig. 1a. Owing to its spin properties, an initial equal superposition state of two of the relevant states (e.g., \(\{\left|0\right\rangle ,\left|-1\right\rangle \}\)) accumulates a phase due to interaction with an external magnetic field. A rotation of the evolved state into the measurement basis reflects the accumulated phase as a population imbalance between the NV centre spin states, which can be measured thanks to the distinct fluorescence rates of each of the states. Such an initial state is most sensitive to the slowest frequency components of the (magnetic) noise. Therefore, dynamical decoupling (DD) sequences are routinely used to filter out the effect of slow noise, prolong coherence times, and enable sensing of specific frequency components of the signal18,30,31.

In statistically polarised nano-NMR, the magnetic signal originates on an ensemble of nuclei within a small sensing volume oscillating at their Larmor frequency. Diffusion of molecules induces magnetic noise, which we model as a stationary Gaussian process with zero mean. For all experiments, we estimate that the possible spectral broadening effect that back-action on the NV centre or a gradient field due to the NV sensor32 is at least one order of magnitude smaller than the broadening caused by diffusion (see Supplementary Note 5). Therefore, we consider it negligible for the ensuing analysis of the decay of correlations due to diffusion. Throughout the experiments described here, we will be probing the auto-correlation of the time evolution of the NV centre interacting with the nuclear spins, which is given by the noise covariance of the external signal,

Here, Φrms is the accumulated phase on the NV probe, which is proportional to the root-mean-square field Brms originating from the statistically polarised nuclei, and δ is the typically small undersampling frequency of the detected signal. The latter is equal to the difference between the Larmor frequency and the frequency defined by the sampling times in the measurement protocol. The envelope C(t/TD) describes the effect of noisy fluctuations due to diffusion, with characteristic diffusion time \({T}_{D}=\frac{{d}^{2}}{D}\) where D is the diffusion coefficient16. Its particular shape is determined by the specific interaction between the sample and the sensor. For NV centres, it is the magnetic dipole–dipole interaction with the nuclei. In the common paradigm, this interaction lasts for TD. Thus, nuclei that diffuse beyond a distance \(\sqrt{{T}_{D}D} \sim d\) are too far to interact with the NV centre. This defines an interaction volume that is a hemisphere of radius ~ d above the surface of the diamond, illustrated by the solid colour region in Fig. 1b16. Correlations of the magnetic field at the NV position reflect the diffusion of nuclei in or out of this hemisphere, and the assumption about the interaction duration means that correlations are lost when nuclei diffuse out of the interaction region. In this picture \(C(t/{T}_{D})\propto \exp (-t/{T}_{D})\). The exponential model is widely accepted in the field due to its success when the measurement times are short and the frequencies probed are easily resolved15,16,33. However, such approximation has profound implications over measurements about the diffusion coefficient D in microfluids28,29. Moreover, it results in a resolution problem, which cannot be overcome24.

A more careful analysis of the dipole–dipole interaction renders a significantly different behaviour28. Heuristically, it can be understood as follows: the magnetic field generated at the NV position as a result of a nucleus located at a point \(\overrightarrow{r}\) is \(B(t)\propto \frac{1}{{r}^{3}}\). Hence, the correlation of the magnetic field is \(< B(t)B(0) > \propto < \frac{1}{{r}^{3}}\frac{1}{r{^{\prime} }^{3}} >\), where the coordinates \(\overrightarrow{r}\) and \(\overrightarrow{r}^{\prime}\) of a specific nucleus are related by its diffusive motion. This connection is usually observed in the second moment \(< r{^{\prime} }^{2} > = < x{^{\prime} }^{2} > + < y{^{\prime} }^{2} > + < z{^{\prime} }^{2} > ={x}^{2}+{y}^{2}+4Dt+ < z{^{\prime} }^{2} > \approx {r}^{2}+6Dt,\) where 2Dt is the variance in the nuclei positions in one dimension. Diffusion of molecules close to the surface is free along the surface directions x and y but limited in the orthogonal z. Hence, the second equality is always valid, while the last approximation is correct for t ≪ TD or t ≫ TD, where the exact geometry of the problem is less important. Substituting the second moment into the auto-correlation function yields \(< B(t)B(0) > \propto \left< \frac{1}{{r}^{3}}\frac{1}{{\left({r}^{2}+6Dt\right)}^{3/2}} \right>\). Averaging over the effective interaction volume leads to the approximate form \(< B(t)B(0) > \propto \frac{1}{{d}^{3}}\frac{1}{{\left({d}^{2}+6Dt\right)}^{3/2}}\). At short times t ≪ TD only close nuclei contribute, the hemisphere region approximation is valid, and correlations replicate the exponential behaviour. At long times, the interaction region expands beyond the hemisphere paradigm, as shown in Fig. 2b, and correlations decay as a power law \(< B(t\gg {T}_{D})B(0) > \propto \frac{1}{{\left(6Dt\right)}^{3/2}}\). The full expression for C(t/TD) in this scenario is given by G(t/TD) in Eq. (12) (see Methods). A more detailed derivation of the asymptotic behaviour of the power spectrum due to these correlations shown in Fig. 1d can be found in Supplementary Note 3 and in ref. 28.

(a) Signal of the correlation spectroscopy measurement as a function of the time difference between the two DD sequences (black dots) and fits of the exponential (blue line) and power-law (orange line) models. Labels show the goodness of fit. The power-law model, described by Eq. (12), offers a better fit to the data, which can be appreciated also in the C(t/TD) envelope (dashed lines). In both models, the initial amplitude for the fitting algorithm is fixed, obtained from an independent estimate in a power spectrum measurement. (b) Fast Fourier transform (FFT) of the experimental data together with FFT from the fitted data in (a) to the exponential and the power-law decay models, shown for illustrative purposes. The sharpness displayed by the power-law model allows for a more precise frequency estimation than the exponential model.

Experiments

We performed a series of experiments comprising three different setups: correlation spectroscopy measurements with single NV centres and with an ensemble of NV centres, and quantum heterodyne (Qdyne) with single NV centres. The experiments and results are reported in each subsection, altogether reinforcing the validity of the power-law scaling of the correlation’s decay. Description of the measurement sequences can be found in section IV Methods and all experimental details and parameters are described in Supplementary Note 4.

Correlation spectroscopy with a single NV centre

The first set of experiments is carried out on a shallow NV centre, which is located at a depth ≈ 2.9 nm below the surface of an isotopically enriched (99.999% 12C) diamond sample grown by chemical vapour deposition34,35. The shallow NV centre is addressed via a fluorescent confocal scan and is initialised and read out using a 532 nm laser pulse. We apply a bias field of ≈ 450 G along the NV axis using a permanent magnet to lift the ms = ± 1 degeneracy (see Fig. 1a). Microwave pulses for coherent control of the NV centre are applied through a copper wire of 20 μm diameter strapped across the diamond, and we use state-dependent photoluminescence measurements to detect the population of the spin states. The interaction of the NV centre with hydrogen nuclear spins in the immersion oil (Fluka 10976, viscosity of 400 cSt) is measured.

The NV centre is initialised into its ms = 0 state, and read out optically. We use correlation spectroscopy to probe the diffusion spectrum (see section “Correlation spectroscopy” in Methods and Supplementary Note 1 for details). First, we prepare the system in state \(\left|Y\right\rangle =\frac{\left|0\right\rangle +i\left|1\right\rangle }{\sqrt{2}}\) by applying a π/2 pulse around x-axis and use two Knill dynamical decoupling (KDD4) sequences, separated by a waiting time difference T36,37,38,39. The centres of two subsequent π pulses in the sequence are separated by the time τ = 1/2fL, where fL is the Larmor frequency of the nuclear spins36,37,38,39, which allows for maximum phase accumulation of the NV centre due to the interaction with the nuclear spins. In this case, the Larmor frequency is 1.9 MHz. The information about the accumulated phase during the first decoupling sequence is mapped onto the spin population by another π/2 pulse applied around the y-axis. This result is then correlated with the second interrogation starting at time t = Nτ + T of the second KDD4 decoupling sequence, where N = 20 is the number of pulses in KDD4. The obtained signal is proportional to the correlation of the accumulated phases during the two sequences, and allows us to directly extract the auto-correlation of the signal.

Figure 2a shows the measured signal vs. the time t between the beginnings of the two DD sequences, fitted to the exponential and the power-law decay models described by the correlation function Eq. (1) with envelopes Eqs. (11) or (12), respectively. Note that Eq. (12) comes from exact mathematical calculations such that the envelope is valid for any time and shows a power-law decay for longer correlation times. We restrict the parameter space for both models by estimating the initial value of the signal amplitude \(\sim {{{\Phi }}}_{{{{\rm{rms}}}}}^{2}\) from an independent power spectrum measurement, which is typically used for finding the depth of the NV centre (see ref. 16 and Supplementary Note 4B). This is preferable, as the signal sampling times are chosen for better estimation of long-lived correlations. Thus, the estimate of the initial amplitude is not efficient and differs significantly between the two models, making comparison difficult. We then use the estimated value as a fixed input parameter for both models and apply non-linear least squares fitting of the signal. We start from 500 different initial conditions and take the best fit.

The obtained fits in Fig. 2a show that the power-law decay model performs better with an R2 ≈ 0.93 in comparison to R2 ≈ 0.90 for the exponential model. Its goodness of fit is evident especially at long times, e.g., between 50 and 100 μs, which correspond to more than three times the expected diffusion time TD ≈ 17 μs, highlighting the importance of long-lived correlations for an accurate estimation of the diffusion coefficient, and emphasising the need to estimate independently the initial contrast and the characteristic decay time in order to obtain accurate measurements of the diffusion coefficient.

In addition, Fig. 2b shows a comparison of the Fast Fourier transform (FFT) of the experimental data and the FFT from the fitted data to the exponential and the power-law decay models. The results show that the power-law decay model provides a better fit to the data than the exponential model. Its spectral linewidth is narrower than with the exponential fit, which is due to the long-lived correlations of the power-law model. Such a feature enables improved precision and resolution in sensing experiments due the sharply peaked spectrum of the power-law model (see also Fig. 1d). The slight broadening of the experimental FFT is mainly due to the fitting procedure, which uses zero padding, so we prolong the time domains of the fits of both theoretical models accordingly. This results in a sharper peak for the power-law model, as expected from theory. Such broadening can also be present due to extra noise sources, which produce exponential decay at a much slower rate than that of diffusion noise, as described in Supplementary Note 5.

Correlation spectroscopy with an NV centres ensemble

The next set of experiments is carried out on an ensemble of NV centres. Similarly to the single NV experiment, we use correlation spectroscopy to probe the diffusion spectrum. Here, a perfluoropolyether oil (Fomblin Y, Sigma Aldrich 317926, viscosity of 60 cSt) is analysed. We detect the signal coming from nuclei in the Fomblin oil, which sits above a proton layer located on top of the diamond surface, preventing fluorine nuclei from sticking to the surface. Thus, we can rule out surface effects as the underlying cause of the power-law behaviour.

The correlation spectroscopy protocol is the same as in the single NV experiment, except that each of the two DD sequences is KDD4-4, i.e., KDD4, repeated four times, accounting for the larger average depth of the NV centres in the ensemble of about 9 nm and the higher Larmor frequency, for which the centres of the decoupling pulses are separated by τ = 1/2fL = 135.6 ns (fL = 3.687 MHz).

Figure 3a displays the measured signal vs. the time t between the beginnings of the two DD sequences, together with its fit to the two decay models, exponential and power-law, as described. We use the same data analysis approach as for the single NV centre experiments. Since the measurements focus on targeting the later times of the correlations, sampling times are chosen accordingly. Thus, instead of considering the signal amplitude as a free parameter, which is inefficient and leads to big differences between models (see Supplementary Note 4C), we estimate it from independent power spectrum measurements and provide it as a fixed input parameter to each of the 500 non-linear least squares fittings of the signal, analogously to the single NV experiment, and consider the best fit. The obtained fits in Fig. 3a show that the power-law decay model provides a better fit to the experiment, in line with the results obtained with the single NV centre. The goodness of the fit of the power-law model is especially better at long times, e.g., between 200 and 400 μs, similarly to the single NV centre experiment. Finally, Fig. 3b compares the FFT of experimental data and the FFTs of the exponential and power-law fits to the experimental signal. We observe that not only the power-law model provides a better fit to the power spectrum of the data but also a sharply peaked spectrum, which is in principle key for improved precision and resolution.

(a) Signal of the correlation spectroscopy measurement vs. the time difference between the two DD sequences (black dots) and fits of the exponential (blue line) and power-law models (orange line) with their goodness of fit and the corresponding envelopes shown as dashed lines. The power-law model shows a better fit to the data, especially at long times. In both fits we fixed the initial amplitude of the fitted signal to an estimate from an independent power spectrum measurement. (b) Fast Fourier transform (FFT) of the experimental data together with the FFT from the fitted data to the exponential and the power-law decay models, shown here for illustrative purposes. Similarly to the single NV centre experiments, the power-law model provides a better fit of the sharp-peaked spectral line, thus allowing for better frequency estimation.

Qdyne with a single NV centre

Qdyne experiments rely on individual storage of each single readout performed at a constant rate7,40, in contrast to conventional measurements (as correlation spectroscopy) where the acquired data is averaged. In post-processing, the auto-correlation of the obtained time-trace reveals the accumulated signal. For that reason a single dynamical decoupling measurement sequence is repeated continuously. The experiments were performed with NV centres at a moderate depth between 8 and 15 nm. We performed six different Qdyne experiments spanning a total measurement time of ≈ 40 days. The Fluka immersion oil is used for five and another perfluoropolyether oil (Fomblin Y, Sigma Aldrich 317993, viscosity of 1508 cSt) for one measurement. XY8 dynamical decoupling is employed with different number of repetitions according to the depth of the NV centre where for all measurements the Larmor frequency is about fL ≈ 2 MHz. Full details of the experimental parameters are given in Supplementary Note 4D. For each experiment, the resultant time-traces are divided into 15 min slices ( ~ 107 measurements) for which the auto-correlation is calculated. Further noise reduction is achieved by averaging 20 of these auto-correlations. Frequency estimation is done by non-linear least squares fitting of the averaged auto-correlations to the modelling function Eq. (10) (see Methods), which compared to Eq. (1), contains a non-physical phase φ, included for reasons of stability in the numerical analysis. For each C(t/TD) model considered throughout, we perform a local optimisation with fixed initial parameters, taking the initial frequency from FFT of the auto-correlation of the full time-trace, and a global optimisation repeated 500 times with random initial parameters drawn from uniform distributions, in which the best fitting is determined by the highest R2 (see section “Statistical analysis” in Methods for full details). The latter analysis mimics the procedure in the case when FFT yields no results, e.g., when the signal decay is too fast.

Focusing on the first experiment (see Supplementary Table 1), the upper row of Fig. 4 displays the histogram of 18 frequency estimators for global optimisation of each model, with φ a free fitting parameter in Fig. 4a and kept fixed (φ = 0) in Fig. 4b. Results are consistent with the detection of a frequency δ ≈ 900 Hz, on a sample with estimated TD = 400 μs, i.e., a frequency smaller than the noise bandwidth defined by the characteristic decay time of the auto-correlation. FFT analysis of the full signal’s correlation (see Supplementary Fig. 5) indicates a frequency centred at 970 Hz with a FWHM of 1205 Hz. In both instances of Fig. 4, the root-mean-square error (rmse) of the estimator is smaller in the case of power-law correlations fitting as compared to exponential; 292 Hz vs. 468 Hz in Fig. 4a and 242 Hz vs. 317 Hz in Fig. 4b, with the standard deviation showing similar scaling.

The data is obtained from non-linear least squares fitting of auto-correlations for experimental (upper row) and numerical (lower row) Qdyne time-traces. In blue, fitting function assumes exponential decay of correlations while in orange the power-law model is considered. Each estimator corresponds to the highest R2 in 500 fittings of the same time-trace. In (a), the phase φ is left as a free fitting parameter while in (b) it is kept fixed to φ = 0. (c) displays the results for numerical data generated for auto-correlations with power-law decay while in (d) the data is generated for exponentially decaying auto-correlations.

Further evidence of power-law correlations is provided by generating artificial time-traces numerically. We simulate Qdyne experiments with parameters similar to those in the experiment shown in the upper row of Fig. 4, with two distinct noise models, which produce two data sets with either exponential or power-law correlations as explained in section “Numerical simulations” in Methods. Each of the data sets is simultaneously analysed with both models, and the resulting histograms for the frequency estimators displayed in the lower row of Fig. 4. In Fig. 4c, we show the results for data generated with power-law correlations, where a peak at a frequency ≈ 900 Hz can be estimated. Power-law model fitting yields a rmse of 195 Hz, while exponential fitting of the power-law auto-correlations is slightly wider at 270 Hz. Fig. 4d displays the results corresponding to time-traces generated with exponential correlations. Here, no frequency is detected and the rmse is 368 Hz for exponential fitting and 385 for the power-law model. Notice that the search region limit is 404 Hz for a flat histogram rmse, indicating that both estimators are essentially featureless. Together with the detection of a frequency below the noise bandwidth, our results are consistent with power-law correlations.

Note that in Fig. 4a, fitting to exponential correlations results in a histogram which goes to the extreme of the search region, signalling that the fitting generally fails. Only by reducing the number of parameters, restricting φ to 0, is the problem ameliorated. This does not happen for power-law model fitting. Results for local optimisation (displayed in Supplementary Fig. 6) display similar behaviour and, for power-law correlations, there exists a trend in the rmse, which diminishes as the fitting model is refined, e.g., in local optimisation or with fixed parameters. Such trend is not found for exponential correlations fitting. That the fitting fails when an extra, meaningless parameter is added provides further evidence that it is the power-law model, which best describes the experimental data.

We complete the analysis by considering the rmse ratio between power-law and exponential fittings. Here, most experiments have a frequency higher than the noise bandwidth (see Supplementary Table 1 for details) and therefore frequency estimation poses no problem with either model24. Hence, we resort to compare which model provides the most accurate fitting according to a smaller rmse. Figure 5 displays the rmse ratio for local optimisation of the experimental data, with the dashed line showing the average ratio standing at 0.62 ± 0.16, which means that power-law fitting of the experimental data has an average improvement of 40% of the rmse with respect to exponential fitting. For global optimisation the improvement is 20% (see Supplementary Fig. 7). A numerical analysis of artificial time-traces generated with either correlation model and analysed with both models shows the striking difference existing when analysing the data with the incorrect model. For data generated with power-law correlations the root-mean-square error (rmse) ratio between local optimisation for power-law and exponential model fittings is 0.65 ± 0.27 while for data generated with exponential correlations the ratio is 1.42 ± 0.29, further confirming the experimental results of detection of power-law decay of correlations.

The ratio is plotted as a function of the frequency δ and the noise bandwidth defined by TD. Each dot is calculated with the rmse of histograms as those shown in Fig. 4. Black squares show experimental results. Orange circles display the ratio for data generated with power-law decay while blue stars correspond to data generated with exponential decay. Solid lines show the mean ratio for all dots while shaded areas correspond to the standard deviation for each mean. Note that experiment six in Supplementary Table 1 is not shown but it is considered for the mean ratio.

Diffusion coefficient estimation

Estimating the diffusion coefficient on the micro- and nano-scales is an important but challenging task, and current techniques are prone to errors29. Using NV centres to calculate D from the characteristic time TD in an exponential envelope of correlations leads to inaccuracies, as this model disregards correlations beyond the distance d, which nonetheless carry diffusion information, as shown by a more rigorous modelling28. The ability to measure power-law correlations, as we have done throughout this article, opens up the possibility to estimate D more accurately.

The diffusion time TD is defined as the characteristic time to diffuse at a distance \(d=\sqrt{D{T}_{D}}\). For a hemispherical sensing volume, the number of nuclei is N ∝ d3, then \({B}_{{{{\rm{rms}}}}}\propto \frac{\sqrt{N}}{{d}^{3}}\propto {d}^{-3/2}\) and we have that \(d \sim {B}_{{{{\rm{rms}}}}}^{-2/3}\). Thus, the procedure to obtain D shall be as follows. The Brms can be independently estimated from, e.g., power spectrum measurements (as we do here) or rapid Ramsey measurements; hence the depth d of the NV centre can be obtained. TD is then estimated from a fitting procedure as described in the previous sections, with the Brms a fixed parameter. From these, the diffusion coefficient D can be obtained.

Following this procedure, we estimate D for the correlation spectroscopy measurements with single NV centres shown in Fig. 2. For the exponential model we get \({D}_{\exp }\approx 6.65\times 1{0}^{-13}\,{{{{\rm{m}}}}}^{2}\,{{{{\rm{s}}}}}^{-1}\), with a 95% confidence interval (5.57 − 8.25) × 10−13 m2 s−1, while the power-law model results in Dpl ≈ 4.33 × 10−13 m2 s−1 with a 95% confidence interval (2.95 − 8.15) × 10−13 m2 s−1. The estimate of the diffusion coefficient of the oil in the experiment, based on its viscosity characteristics is of the order of magnitude16 D ≈ 6 × 10−13 m2 s−1, which is within the confidence intervals of the estimates of both models. While the reported confidence intervals are rather large, they could be substantially decreased in future experiments, specifically designed to improve the efficiency of the procedure, e.g., by improving the signal-to-noise ratio and obtaining a clear signal at even longer times, as expected theoretically from the power-law model. Investigation of surface effects on diffusion are also envisaged, e.g., by probing it with NV centres at different depths with surface effects expected to be more pronounced with shallower NV centres.

Discussion

An exponential modelling for correlation’s decay is the natural assumption for nano-NMR experiments. Yet this hypothesis has profound implications on the possible applications of any such experiments. In particular, exponential correlations lead to Lorentzian lineshapes for which spectral resolution is fundamentally limited. It is possible, however, to refine the original assumption by carefully examining the microscopic diffusion process, which is the cause of correlations decay. Diffusion causes power-law decay of correlations at long times for the dipole–dipole interaction that is characteristic for the NV centre nano-NMR spectrometer28. This has substantial consequences, as spectral lineshapes become sharp-peaked, for which in theory there is no limit to resolution24. Yet, measuring deviations from the exponential paradigm and utilising them for improved spectral analysis is a challenging task due to experimental noise. Furthermore, by considering the full interaction model for correlations rather than the truncated exponential model, it shall be possible to measure more precisely the diffusion coefficient D in microfluids, a long sought goal, where current methods have only limited accuracy2,41.

By probing the auto-correlation of the dipole–dipole interaction between NV centres and nuclear spins, and prolonging the measurement time to several times the characteristic exponential decay time, we show strong evidence supporting a power-law decay of correlations as they provide a better fit to the experimental results. Furthermore, with the Qdyne data frequency estimation yields a results, which is 40% more precise than with the exponential model. We can also exclude surface effects causing a long correlation tail by detecting the signal created by fluorine nuclei lying on top of a proton layer adhered to the diamond surface, in which such effects originate15. Additionally, we show that Qdyne measurements auto-correlations are compatible with the same power-law decay to the extent that in the regime where exponential correlations limit frequency resolution, a frequency can still be detected. Finally, we rule out the possibility of exponential correlations by showing with numerical analysis that such correlations in the same regime would lead to featureless histograms or altogether wide spectral lines in which frequency estimation is not possible. Our results offer a way to significantly improve spectral resolution, and enable broad applications of nano-NMR with NV centres. The power-law scaling of correlations which originates in the dipole–dipole interaction between sensor and sample is key to this result, extending the applicability of our results to any quantum sensor based on this interaction, such as Rydberg atoms, squid based sensors, molecular quantum sensors, or alternative colour centres such as silicon carbide42. In addition, the ability to measure accurately correlations of nano-sized fluid samples, opens the door to study flow properties at these scales. It has been recently shown that single trajectory auto-correlations differ from ensemble averaged (multiple trajectories) auto-correlations for anomalously diffusing fluids43, which also show power-law scaling characterised by critical exponents44,45. These single auto-correlations contain crucial information about the sample fluid, which might be missed on typical ensemble averages46. Our results show that it is possible to directly access the microscopic behaviour that underpins the properties of nano-fluids, with applications in a wide variety of fields.

Methods

Samples

All experiments are carried out with an isotopically enriched (99.999% 12C) diamond sample grown by chemical vapour deposition. The diamond substrate with natural abundance of 13C was equipped with a 99.999% 12C enriched homoepitaxially grown diamond film with a thickness of about 150 nm in a home-built plasma enhanced chemical vapour deposition growth reactor34,35,47 using 99.999% enriched 12CH4 gas (Cambridge Isotope Laboratories) at a concentration of 0.2 % with respect to hydrogen.

Isolated shallow NV centres were then created by ion implantation with 15N+ at a dose of 5 × 108 N+ cm−2, using an acceleration energy of 2 keV (correlation spectroscopy), and 2.5 keV (Qdyne). Additionally, for Qdyne measurements utilising deeper NV centres, an ion dose of 1 × 1011 N+ cm−2 at an acceleration voltage of 2.5 keV was used, followed by processing the diamond with the indirect overgrowth method according to ref. 47, burying the NV centres deeper and thus shielding them from noise sources at the surface of the diamond. To heal resulting radiation damage, mobilise vacancies, and eventually create the desired NV centres, the diamond samples are annealed in a home-built UHV furnace at 1000 ∘C for 3 h, while ensuring extremely low process pressures < 1 × 10−7 mbar48.

The NV centre ensembles were created by implanting 15N+ ions with a dose of 1 × 1012N+/cm2 and an energy of 2.5 KeV, followed by annealing as described for the single NV centres. The NV ensemble creation yield was determined to be (1.0 ± 0.1)%, which corresponds to an average NV concentration of 60 ppb taking into account the depth distribution of implanted nitrogen in reference47. After annealing, the diamond is boiled in a 1:1:1 mixture of sulphuric (97%), perchloric (70%) and nitric acid (65%) at 200 ∘C in a microwave reactor system (MWT AG, type ETHOS Lab) for 30 min to remove any (graphitic) residues from the surface.

Power spectrum measurement

We perform power spectrum measurements to determine the Brms of the nuclear spins at the NV centre position16. This is used to determine the initial contrast of the auto-correlation signal and fix the value as in Figs. 2b and 3b. We consider a two-state system, which is prepared initially in state \(\left|0\right\rangle\), e.g., by optical pumping. The power spectrum measurement consists of the microwave pulse sequence π/2(x) pulse—dynamical decoupling—π/2( ∓ x) pulse, where the coordinate in parentheses indicates the axis of rotation. For two alternating measurements, which differ by the axis of rotation of the last π/2-pulse, we take their signal difference. The advantage of using the alternating sequence is reduction of the effect of unwanted laser power fluctuations.

During the DD sequence a phase Φ is accumulated due to the Larmor precession of the nuclear spins. Φ follows a Gaussian distribution where the expectation of Φ is zero. Its variance depends on the strength of the interaction between the NV centre and the nuclear spins in the sensing volume, the filter function of the applied DD sequence and the interaction time. The expected value of the phase variance in case of statistical polarisation is given by \(\langle {{{\Phi }}}^{2}\rangle ={{{\Phi }}}_{{{{\rm{rms}}}}}^{2}\) (see Supplementary Note 2)

where γe is the gyromagnetic ratio for the NV electron spin, Brms is the root-mean-square of the magnetic field of the statistically polarised sample, N is the number of the DD pulses, τ is their pulse separation and ωL is the Larmor frequency of the sensed spins (in angular frequency units). This allows us to estimate Brms and the corresponding depth of the NV centre16.

Correlation spectroscopy

Next, we analyse the expected measurement results with correlation spectroscopy. Again the two-state system is considered, which is prepared initially in state \(\left|0\right\rangle\). We perform the correlation spectroscopy measurement, which consists of two DD blocks, separated by a waiting time T. During the waiting time, the information about the accumulated phase is mapped onto a population difference, so it cannot exceed T1 of the system. The pulse sequence is

where the two versions of the last pulse π/2( ± y) give the alternating projections on the \(\left|0\right\rangle\) and \(\left|1\right\rangle\) states, respectively. The signal is the difference between these two and is given by

where Φ1 and Φ2 are the accumulated phases during the first and the second DD sequences, \({c}_{\max }\) is the maximum readout contrast (see Supplementary Note 1 for details), and we can neglect the effect of decoherence and relaxation because the duration of each dynamical decoupling sequence τN ≪ T2 and the waiting time T ≪ T1.

Averaging multiple measurement readouts leads to

where the last approximation is valid only for small Φk, k = 1, 2. The phases Φk follow the same Gaussian distribution as in the power spectrum measurement, i.e., centred at zero with a variance \({{{\Phi }}}_{{{{\rm{rms}}}}}^{2}\), and we obtain (see Supplementary Note 2)

where t = Nτ + T is the time separation between the beginnings of the two DD sequences and ωL = 2πfL with fL again the Larmor frequency of the sensed spins (or the respective undersampling frequency). In our analysis the correlation \(\left\langle B({t}^{\prime})B({t}^{\prime}+t)\right\rangle \approx {B}_{{{{\rm{rms}}}}}^{2}\cos ({\omega }_{{{{\rm{L}}}}}t)C(t)\), where the correlation function C(t) can be exponential16 or have a power-law decay for long times24,28.

Quantum heterodyne detection

Lastly, we focus on the Qdyne protocol40. As before, the initial state of the NV centre is the \(\left|0\right\rangle\) state. In this case, the basic building block of the protocol is a DD sequence encased in between two π/2 pulses as

The salient feature of the Qdyne protocol is that the projection of the NV state through the second π/2 pulse, is followed not only by state readout/re-initialisation but also by a fixed delay time that defines the sampling frequency with which measurements are repeated, thereby recording information about the phase of the target signal, a crucial point that permits correlating all measurement outcomes in post-processing.

No alternating measurement protocol is used here. The signal for a given measurement at time t in a Qdyne measurement sequence is

In post-processing of the data the auto-correlation of the recorded time-trace is calculated. The correlation between any two readout pairs that are separated by tn = nTQd, where TQd is the sequence length of a single measurement, is then

With Φt = Φ1 and \({{{\Phi }}}_{t+{t}_{n}}={{{\Phi }}}_{2}\) the same signal as in correlation spectroscopy (5) is measured.

Statistical analysis

Parameter estimation is done by numerically fitting the experimental auto-correlation functions to the theoretical mode

where a0 is a signal offset, \({a}_{1} \sim {{{\Phi }}}_{{{{\rm{rms}}}}}^{2}\) is the signal amplitude, δ is the undersampling frequency, φ is the signal phase, and TD is the diffusion time. In the fits of Figs. 2 and 3 the parameter \({a}_{1} \sim {{{\Phi }}}_{{{{\rm{rms}}}}}^{2}\) is fixed and estimated from an independent power spectrum measurement. Note that we have included an artificial phase φ. This is necessary for correlation spectroscopy experiments as the undersampling frequency δ is typically much smaller than the actual Larmor frequency ωL, which can result in a non-zero phase, e.g., when the first sampling time is smaller than the oscillation period at δ. The reason is purely numerical for Qdyne as the fitting algorithm is prone to crashing, especially when considering the power-law correlations with Eq. (12). Then, the phase aids in adding stability and thus saving computational time. In all of the instances where we include it as a free parameter, we check that the estimation result for φ is either 0 or 2π within numerical precision. For the correlation function decay described by the envelope C(t/TD) we consider either that (exponential model)

or (power-law model) as in ref. 28

with z = t/TD and C(z) = G(z) to distinguish it from other possible power-law models. The latter is shown to fall off as C(z ≪ 1) ∝ z−3/2, for which reason we call it the power-law model.

The fitting procedure utilises a non-linear least squares algorithm with finite-difference estimation of the gradient. In correlation spectroscopy data, due to measurement vectors being indivisible, we compare goodness of fitting for each of the two correlation models, using the R2 as a figure of merit. For each signal and model, the fitting procedure is repeated 500 times and the best fitting according to the highest R2 is selected. The procedure is akin to the global optimisation described below for the Qdyne data.

Qdyne data analysis deserves a more in-depth explanation. Qdyne experiments are performed sequentially, therefore, each experiment yields a single time-trace of measurements spanning the total duration of the experiment. Here, we describe the processing of the data corresponding to the experiment shown in Fig. 4a, b, as the rest are analogous. In this case, the total measurement duration is 90 h, while each single measurement requires 49.740 μs. Contrary to the case of correlation spectroscopy, where the data recording procedure did not allow to slice the time-traces, in Qdyne we can partition the data in arbitrarily short vectors. For reasons of setup stability the slices are of 15 min worth of measurements. In between two of these 15-min time-traces the NV centre is optically refocused. However, the resulting auto-correlations are too noisy for adequate fitting. Thus, we compromise between eliminating noise by averaging several auto-correlations and having sufficient statistics to build a meaningful histogram, i.e., to perform Bayesian analysis. For Fig. 4a, b that means averaging 20 auto-correlations from 15-min time-traces, resulting in a total of 18 auto-correlations with which to perform statistical analysis. Each of the 18 resulting averaged auto-correlations is fitted to the model as explained above, yielding a total of 18 frequency estimators that compose the shown histograms.

In the case of local optimisation each of the 18 auto-correlations is fitted once to the model Eq. (1), with input parameters taken from the FFT of the total auto-correlation calculated over the full 90 h time-trace for the frequency, and amplitude and decay time taken directly from the full auto-correlation. For global optimisation, the fitting procedure is repeated 500 times, each time with different initial parameters randomly drawn from uniform distributions of size equal to the allowed searching regions for the fitting procedure (e.g., from 200 to 1800 Hz for the frequency estimator). This procedure is repeated for each of the 18 time-traces and for each case the frequency of the highest R2 fitting results in the estimator considered for statistics. In all cases the figure of merit is the root-mean-square error of the resulting histogram of estimators.

Numerical simulations

Qdyne signals are generated numerically employing data from molecular dynamics simulations24,49. We utilise molecular dynamics simulations data of N ≈ 46 × 103 dipolar particles within a simulation box of size Lx,y,z = (50, 50, 24) nm with an NV centre located at depths ranging from 0.3 to 12 nm. The particles within the box diffuse according to a Lennard-Jones fluid with normalised parameters ϵ = σ = 1 (where ϵ is the depth of the potential while σ is the distance at which the potential is zero), starting from an initial thermal state at temperature \(T=\frac{{\kappa }_{B}T(K)}{\epsilon }\)28. The magnetic signal is calculated as the magnetic field induced by the particles at the NV position. The data thus generated proves to have no trends and the standard deviation is scale invariant, i.e., depth independent, meaning that noise data generated for one depth can be scaled through the corresponding TD to suit a different depth24. Therefore, we are able to use all depths, thus, increasing the statistics. The resultant time-traces contain the power-law noise model with correlations scaling as \(C(t/{T}_{D}\gg 1) \sim {(t/{T}_{D})}^{-3/2}\) and thus we use them directly to generate Qdyne time-traces associated with this model. Exponential correlations are simulated by fitting the molecular dynamics data to Orstein-Uhlenbeck noise, which process exponential decay, and using such fitting as the noise source.

Data availability

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Code availability

The code used for obtaining the presented numerical results is available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

References

Chen, Y., Lagerholm, B. C., Yang, B. & Jacobson, K. Methods to measure the lateral diffusion of membrane lipids and proteins. Methods 39, 147–153 (2006).

Eggeling, C. et al. Direct observation of the nanoscale dynamics of membrane lipids in a living cell. Nature 457, 1159–1162 (2009).

Kovacs, H., Moskau, D. & Spraul, M. Cryogenically cooled probes–a leap in NMR technology. Prog. Nucl. Magn. Reson. Spectrosc. 46, 131–155 (2005).

Aslam, N. et al. Nanoscale nuclear magnetic resonance with chemical resolution. Science 357, 67–71 (2017).

Bucher, D. B., Glenn, D. R., Park, H., Lukin, M. D. & Walsworth, R. L. Hyperpolarization-Enhanced NMR Spectroscopy with Femtomole Sensitivity Using Quantum Defects in Diamond. Phys. Rev. X 10, 021053 (2020).

Degen, C. L., Reinhard, F. & Cappellaro, P. Quantum sensing. Rev. Mod. Phys. 89, 035002 (2017).

Boss, J. M., Cujia, K. S., Zopes, J. & Degen, C. L. Quantum sensing with arbitrary frequency resolution. Science 356, 837–840 (2017).

Ajoy, A., Bissbort, U., Lukin, M. D., Walsworth, R. L. & Cappellaro, P. Atomic-scale nuclear spin imaging using quantum-assisted sensors in diamond. Phys. Rev. X 5, 011001 (2015).

Lovchinsky, I. et al. Nuclear magnetic resonance detection and spectroscopy of single proteins using quantum logic. Science 351, 836–841 (2016).

Staudacher, T. et al. Nuclear magnetic resonance spectroscopy on a (5-Nanometer)3 sample volume. Science 339, 561–563 (2013).

Glenn, D. R. et al. High-resolution magnetic resonance spectroscopy using a solid-state spin sensor. Nature 555, 351–354 (2018).

Bucher, D. B., Glenn, D. R., Park, H., Lukin, M. D. & Walsworth, R. L. Hyperpolarization-enhanced NMR spectroscopy with femtomole sensitivity using quantum defects in diamond. Phys. Rev. X 10, 021053 (2020).

DeVience, S. J. et al. Nanoscale NMR spectroscopy and imaging of multiple nuclear species. Nat. Nanotechnol. 10, 129–134 (2015).

Loretz, M., Pezzagna, S., Meijer, J. & Degen, C. Nanoscale nuclear magnetic resonance with a 1.9-nm-deep nitrogen-vacancy sensor. Appl. Phys. Lett. 104, 033102 (2014).

Staudacher, T. et al. Probing molecular dynamics at the nanoscale via an individual paramagnetic centre. Nat. Commun. 6, 8527 (2015).

Pham, L. M. et al. NMR technique for determining the depth of shallow nitrogen-vacancy centers in diamond. Phys. Rev. B 93, 045425 (2016).

Fernández-Acebal, P. et al. Toward hyperpolarization of oil molecules via single nitrogen vacancy centers in diamond. Nano Lett. 18, 1882–1887 (2018).

Degen, C. L., Poggio, M., Mamin, H. J. & Rugar, D. Role of spin noise in the detection of nanoscale ensembles of nuclear spins. Phys. Rev. Lett. 99, 250601 (2007).

Reinhard, F. et al. Tuning a spin bath through the quantum-classical transition. Phys. Rev. Lett. 108, 200402 (2012).

Herzog, B. E., Cadeddu, D., Xue, F., Peddibhotla, P. & Poggio, M. Boundary between the thermal and statistical polarization regimes in a nuclear spin ensemble. Appl. Phys. Lett. 105, 043112 (2014).

Mamin, H. J. et al. Nanoscale nuclear magnetic resonance with a nitrogen-vacancy spin sensor. Science 339, 557–560 (2013).

Müller, C. et al. Nuclear magnetic resonance spectroscopy with single spin sensitivity. Nat. Commun. 5, 4703 (2014).

Hubbard, P. S. Nuclear magnetic relaxation by intermolecular dipole-dipole interactions. Phys. Rev. 131, 275–282 (1963).

Oviedo-Casado, S., Rotem, A., Nigmatullin, R., Prior, J. & Retzker, A. Correlated noise in Brownian motion allows for super resolution. Sci. Rep. 10, 19691 (2020).

Abbe, E. Beiträge zur Theorie des Mikroskops und der mikroskopischen Wahrnehmung. Arch. Mikrosk. Anat. 9, 413–468 (1873).

Lord Rayleigh, F. XXXI. Investigations in optics, with special reference to the spectroscope. Lond. Edinb. Dubl. Philos. Mag. 8, 261–274 (1879).

Jones, A. W., Bland-Hawthorn, J. & Shopbell P. L. Towards a General Definition for Spectroscopic Resolution. Vol. 77 (Astronomical Society of the Pacific Conference Series, 1995).

Cohen, D. et al. Utilising NV based quantum sensing for velocimetry at the nanoscale. Sci. Rep. 10, 5298 (2020).

Shagieva, F. et al. Lateral diffusion of phospholipids in artificial cell membranes measured by single shallow NV centers. Preprint at: https://arxiv.org/abs/2105.07712 (2021).

Viola, L., Knill, E. & Lloyd, S. Dynamical decoupling of open quantum systems. Phys. Rev. Lett. 82, 2417–2421 (1999).

Cywiński, L., Lutchyn, R. M., Nave, C. P. & Das Sarma, S. How to enhance dephasing time in superconducting qubits. Phys. Rev. B 77, 174509 (2008).

Unden, T. et al. Coherent control of solid state nuclear spin nano-ensembles. npj Quantum Inf. 4, 39 (2018).

Kong, X., Stark, A., Du, J., McGuinness, L. P. & Jelezko, F. Towards chemical structure resolution with nanoscale nuclear magnetic resonance spectroscopy. Phys. Rev. Appl. 4, 024004 (2015).

Osterkamp, C. et al. Engineering preferentially-aligned nitrogen-vacancy centre ensembles in CVD grown diamond. Sci. Rep. 9, 1–7 (2019).

Silva, F., Bonnin, X., Scharpf, J. & Pasquarelli, A. Microwave analysis of PACVD diamond deposition reactor based on electromagnetic modelling. Diam. Relat. Mater. 19, 397–403 (2010).

Ryan, C. A., Hodges, J. S. & Cory, D. G. Robust decoupling techniques to extend quantum coherence in diamond. Phys. Rev. Lett. 105, 200402 (2010).

Souza, A. M., Álvarez, G. A. & Suter, D. Robust dynamical decoupling for quantum computing and quantum memory. Phys. Rev. Lett. 106, 240501 (2011).

Genov, G. T., Schraft, D., Vitanov, N. V. & Halfmann, T. Arbitrarily accurate pulse sequences for robust dynamical decoupling. Phys. Rev. Lett. 118, 133202 (2017).

Casanova, J., Wang, Z.-Y., Haase, J. F. & Plenio, M. B. Robust dynamical decoupling sequences for individual-nuclear-spin addressing. Phys. Rev. A 92, 042304 (2015).

Schmitt, S. et al. Submillihertz magnetic spectroscopy performed with a nanoscale quantum sensor. Science 356, 832–837 (2017).

Heinemann, F., Betaneli, V., Thomas, F. A. & Schwille, P. Quantifying lipid diffusion by fluorescence correlation spectroscopy: a critical treatise. Langmuir 28, 13395–13404 (2012).

Yu, C.-J., von Kugelgen, S., Laorenza, D. W. & Freedman, D. E. A molecular approach to quantum sensing. ACS Cent. Sci. 7, 712–723 (2021).

Metzler, R. Brownian motion and beyond: first-passage, power spectrum, non-Gaussianity, and anomalous diffusion. J. Stat. Mech. 2019, 114003 (2019).

Sadegh, S., Barkai, E. & Krapf, D. 1/f noise for intermittent quantum dots exhibits non-stationarity and critical exponents. N. J. Phys. 16, 113054 (2014).

Leibovich, N., Dechant, A., Lutz, E. & Barkai, E. Aging Wiener-Khinchin theorem and critical exponents of 1/fβ noise. Phys. Rev. E 94, 052130 (2016).

Krapf, D. et al. Spectral content of a single non-brownian trajectory. Phys. Rev. X 9, 011019 (2019).

Findler, C., Lang, J., Osterkamp, C., Nesládek, M. & Jelezko, F. Indirect overgrowth as a synthesis route for superior diamond nano sensors. Sci. Rep. 10, 1–9 (2020).

Lang, J. et al. Long optical coherence times of shallow-implanted, negatively charged silicon vacancy centers in diamond. Appl. Phys. Lett. 116, 064001 (2020).

Cohen, D., Nigmatullin, R., Eldar, M. & Retzker, A. Confined nano-NMR spectroscopy using NV centers. Adv. Quantum Technol. 3, 2000019 (2020).

Acknowledgements

S.O.C. acknowledges the support from the Fundación Ramón Areces postdoctoral fellowship (XXXI edition of grants for Postgraduate Studies in Life and Matter Sciences in Foreign Universities and Research Centres). A.V.S. acknowledges the support from the European Union’s Horizon 2020 research and innovation program under the Marie Skłodowska-Curie Grant Agreement No. 766402. N. Staudenmaier. acknowledges support from the Bosch-Forschungsstiftung. D.C. acknowledges the support of the Clore Scholars Programme and the Clore Israel Foundation. This work was supported by the European Union’s Horizon 2020 research and innovation program under grant agreement No 820394 (ASTERIQS), DFG (CRC 1279 and Excellence cluster POLiS), ERC Synergy grant HyperQ (Grant No. 856432), BMBF and VW Stiftung. A.R. acknowledges the support of ERC grant QRES, project number 770929, grant agreement number 667192 (Hyperdiamond), ISF and the Schwartzmann university chair.

Funding

Open Access funding enabled and organized by Projekt DEAL.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

A.R., D.C. and F.J. conceived the idea. N. Staudenmaier did the Qdyne measurements with single NV centres. A.V.S. and G.G. performed the correlation spectroscopy measurements with single NV centres, while D.D., T.U., N. Striegler and P.N. did the corresponding experiments with ensembles of NV centres. A.M. and J.S. helped with the integration of hardware and software. A.V.S., G.G., N. Staudenmaier and S.O.C. did the analysis of the experimental results and S.O.C. did the simulation for the numerical data. C.F. and J.L. provided the diamond samples for the measurements. A.V.S., G.G., N. Staudenmaier and S.O.C. prepared the manuscript. All authors read and contributed to the paper. A.R., I.S., P.N. and F.J. supervised the project. N. Staudenmaier, A.V.S., S.O.C. and G.G. contributed equally.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons license and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Staudenmaier, N., Vijayakumar-Sreeja, A., Oviedo-Casado, S. et al. Power-law scaling of correlations in statistically polarised nano-NMR. npj Quantum Inf 8, 120 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41534-022-00632-1

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41534-022-00632-1

This article is cited by

-

Extending the coherence of spin defects in hBN enables advanced qubit control and quantum sensing

Nature Communications (2023)