Abstract

Reinforcement learning has witnessed recent applications to a variety of tasks in quantum programming. The underlying assumption is that those tasks could be modeled as Markov decision processes (MDPs). Here, we investigate the feasibility of this assumption by exploring its consequences for single-qubit quantum state preparation and gate compilation. By forming discrete MDPs, we solve for the optimal policy exactly through policy iteration. We find optimal paths that correspond to the shortest possible sequence of gates to prepare a state or compile a gate, up to some target accuracy. Our method works in both the absence and presence of noise and compares favorably to other quantum compilation methods, such as the Ross–Selinger algorithm. This work provides theoretical insight into why reinforcement learning may be successfully used to find optimally short gate sequences in quantum programming.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Recent years have seen dramatic advances in the field of artificial intelligence1 and machine learning2,3. A long-term goal is to create agents that can carry out complicated tasks in an autonomous manner, relatively free of human input. One of the approaches that has gained popularity in this regard is reinforcement learning. This could be thought of as referring to a rather broad set of techniques that aim to solve some task based on a reward-based mechanism4. Formally, reinforcement learning models the interaction of an agent with its environment as a Markov decision process (MDP). In many practical situations, the agent may have limited access to the environment, whose dynamics can be quite complicated. In all such situations, the goal of reinforcement learning is to learn or estimate the optimal policy, which specifies the (conditional) probabilities of performing actions given that the agent finds itself in some particular state. On the other hand, in fairly simple environments such as the textbook grid-world scenario4, the dynamics can be fairly simple to learn. Moreover, the state and action spaces are finite and small, allowing for simple tabular methods instead of more complicated methods that would, for example, necessitate the use of artificial neural networks3. In particular, one could use the dynamic programming method of policy iteration to solve for the optimal policy exactly5.

In recent times, reinforcement learning has met with success in a variety of quantum programming tasks, such as error correction6, combinatorial optimization problems7, as well as state preparation8,9,10,11,12 and gate design13,14 in the context of noisy control. Here, we investigate the question of state preparation and gate compilation in the context of abstract logic gates and ask whether reinforcement learning could be successfully applied to learn the optimal gate sequences to prepare some given quantum state, or compile a specified quantum gate. Instead of exploring the efficacy of any one particular reinforcement method, we investigate whether it is even feasible to model these tasks as MDPs. By discretizing state and action spaces in this context, we circumvent questions and challenges involving convergence rates, reward sparsity, and hyper-parameter optimization that typically show up in reinforcement learning scenarios. Instead, the discretization allows us to exactly solve for and study quite explicitly the properties of the optimal policy itself. This allows us to test whether we can recover optimally short programs using reinforcement learning techniques in quantum programming situations where we already have well-established notions of optimally short programs or circuits.

Our construction applies in the case of both noiseless and noisy scenarios. On realistic hardware, such as on superconducting or ion-trap quantum computing platforms, one could in principle perform process tomography to learn the noise profile of the basic gateset available. One could then solve the MDP whose action space is composed of the noisy gateset. We detail such a construction below, where we consider simple noise models and show that one can still learn optimal circuits for the task of state preparation.

There have been numerous previous studies in the general problem of quantum compilation, including the Solovay–Kitaev algorithm15, quantum Shannon decomposition16, approximate compilation17,18, as well as optimal circuit synthesis19,20,21. Recent applications of reinforcement learning to quantum computing include finding optimal parameters in variational quantum circuits22,23,24, quantum versions of reinforcement learning and related methods25,26,27,28,29,30,31, Bell tests32, as well as quantum control33,34,35,36, state engineering, and gate compilation37,38,39,40,41,42. In such studies, reinforcement learning is employed as an approximate solver of some underlying MDP. This raises the important question of how, and under what conditions, can the underlying MDP be solved exactly, and what kind of solution quality does it result in. Naturally, such MDPs can only be solved exactly for relatively small problem sizes. Here, we explore the answer to this question in the context of single-qubit state preparation and gate compilation and demonstrate the effects of native gate choice, coordinate representation, discretization as well as quantum noise.

Quantum control tasks are naturally affected by different sources of quantum noise and reinforcement learning has previously shown success when applied in the presence of noise13,14. The ability to learn the effects of a quantum noise channel has apparent practical use for the current generation of noisy quantum computers, which are plagued by errors that severely limit the depth of quantum circuits that can be executed. As full error correction procedures are still too resource-intensive to be implemented on current hardware, quantum error mitigation methods that involve post-processing circuit results have been developed to decrease the effect of noise. Examples are zero-noise extrapolation, Clifford data regression, and probabilistic error cancellation43,44,45,46,47. However, there are also pre-processing error mitigation schemes that aim to modify the input circuit in order to reduce the impact of noise. Examples are quantum optimal control methods and dynamical decoupling48,49,50. Such techniques attempt to prepare a desired quantum state on a noisy device using circuits or sequences of pulses that are different from the ones that would be optimal in the absence of noise. We demonstrate that this idea is immediately applicable to the MDP framework.

The organization of this paper is as follows. We first briefly review the formalism of MDPs. We then show our main result of how to formulate quantum control tasks as Markov decision processes. We use this description to investigate the problem of single-qubit state preparation using the discrete gateset {I, H, T}. We then study this problem in the context of noisy quantum channels. Finally, we consider the application to the problem of single-qubit compilation into the {H, T} gateset, and show that learning the MDP can be highly sensitive to the choice of coordinates for the unitaries.

Markov decision processes (MDPs) provide a convenient framing of problems involving an agent interacting with an environment. At discrete time steps t, an agent receives a representation of the environment’s state \({s}_{t}\in {{{\mathcal{S}}}}\), takes an action \({a}_{t}\in {{{\mathcal{A}}}}\), and then lands in state st+1 and receives a scalar reward \({r}_{t+1}\in {{{\mathcal{R}}}}\). The policy of the agent, describing the conditional probability π(a∣s) of taking action a given the state s, is independent of the environment’s state at previous time steps and therefore satisfies the Markov property. The discounted return that an agent receives from the environment after time step t is defined as \({G}_{t}=\mathop{\sum }\nolimits_{k = 0}^{\infty }{\gamma }^{k}{r}_{t+k+1}\) where γ ∈ [0, 1] is the discount factor.

The discount factor controls the extent to which earlier rewards are weighted more than later rewards. In our setup, the exponent k plays the role of the number of steps taken to achieve a target state or unitary. Thus, by setting 0 < γ < 1, we favor shorter gate sequences. The exact value of γ is a hyper-parameter that one needs to tune in practice by trial and error. Too low a value might result in a very weak return that causes the learning agent to become unable to differentiate between long or short sequences beyond a certain value of the length k. On the other hand, too large a value might also result in the same behavior, though for the opposite reason of a roughly equally strong return for all possible paths. For γ = 1, there is no discounting over the length of the sequence k, so that the learning agent does not distinguish between short or long sequences.

The goal of the agent is then to find the optimal policy π*(a∣s) that maximizes the state-value function (henceforth, ‘value function’ for brevity), defined as the expectation value of the discounted return received from starting in state \({s}_{t}\in {{{\mathcal{S}}}}\) and thereafter following the policy π(a∣s), and expressed as \({V}_{\pi }(s)={{\mathbb{E}}}_{\pi }\left[{G}_{t}| {s}_{t}=s\right]\). More formally then, the optimal policy π* satisfies the inequality \({V}_{{\pi }^{* }}(s)\ge {V}_{\pi }(s)\) for all \(s\in {{{\mathcal{S}}}}\) and all policies π. For finite MDPs, there always exists a deterministic optimal policy, which is not necessarily unique. The value function for the optimal policy is then defined as the optimal value function \({V}^{* }(s)={V}_{{\pi }^{* }}(s)={{{\mbox{max}}}}_{\pi }{V}_{\pi }(s)\) for all \(s\in {{{\mathcal{S}}}}\).

The value function satisfies a recursive relationship known as the Bellman equation

relating the value of the current state to that of its possible successor states following the policy π. Note that the conditional probability of finding state \({s}^{{\prime} }\) and receiving reward r having performed action a in state s specifies the environment dynamics, and also satisfies the Markov property. This equation can be turned into an iterative procedure known as iterative policy evaluation

which converges to the fixed point Vk = Vπ in the k → ∞ limit, and can be used to obtain the value function corresponding to a given policy π. In practice, we define convergence as ∣Vk+1−Vk∣ < ϵ for some sufficiently small ϵ.

Having found the value function, we could then ask if the policy that produced this value function could be further improved. To do so, we need the state-action value function Qπ(s, a), defined as the expected return by carrying out action a in state s and thereafter following the policy π, i.e. \({Q}_{\pi }(s,a)={{\mathbb{E}}}_{\pi }\left[{G}_{t}| {s}_{t}=s,{a}_{t}=a\right]\). According to the policy improvement theorem, given deterministic policies π and \({\pi }^{{\prime} }\), the inequality \({Q}_{\pi }(s,{\pi }^{{\prime} }(s))\ge {V}_{\pi }(s)\) implies \({V}_{{\pi }^{{\prime} }}(s)\ge {V}_{\pi }(s)\) where \({\pi }^{{\prime} }(s)=a\) (and in general \({\pi }^{{\prime} }(s)\,\ne \,\pi (s)\)) for all \(s\in {{{\mathcal{S}}}}\). In other words, having found the state-value function corresponding to some policy, we can then improve upon that policy by iterating through the action space \({{{\mathcal{A}}}}\) while maintaining the next-step state-value functions on the right-hand side of Eq. (2) to find a better policy than the current one (ϵ-greedy algorithm for policy improvement).

We can then alternate between policy evaluation and policy improvement in a process known as policy iteration to obtain the optimal policy4. Schematically, this process involves evaluating the value function for some given policy up to some small convergence factor, followed by the improvement of the policy that produced this value function. The process terminates when the improved policy stops differing from the policy in the previous iteration. This procedure to identify the optimal policy for an MDP relies on the finiteness of state and action spaces. It has been shown51,52 that policy iteration runs in \(O(\,{{\mbox{poly}}}\,(| S| ,| A| ,\frac{1}{1-\gamma }))\) many elementary steps. In our context, ∣A∣, the size of the action space, is usually limited to some small number, indicating the number of basic gates we have available. On the other hand, the size of the MDP state space ∣S∣ scales generically as 1/ϵ, where ϵ is the target accuracy.

Results

Quantum control tasks as Markov decision processes

In this section, we formulate general tasks in quantum system control in terms of MDPs with a focus on finite MDPs for state preparation and gate compilation using a discrete gate set. Figure 1 illustrates the complete procedure for the example of single qubit state preparation. Since pure states of a quantum system are represented as vectors in a Hilbert space, the MDP state space \({{{\mathcal{S}}}}\) is defined either as a set of states in a Hilbert space or as a set of mappings between Hilbert spaces, e.g., representing density matrices or quantum operations. If the Hilbert space is continuous, a finite state space \({{{\mathcal{S}}}}\) can be obtained via discretization. The MDP action space \({{{\mathcal{A}}}}\) is associated with physically realizable mappings between these states, e.g. completely positive trace-preserving (CPTP) maps between density matrices. Again, for continuous mappings, one can obtain a finite action space via discretization. The environmental dynamics \(p({s}^{{\prime} },r| s,a)\) is derived from the action of the underlying Hilbert space mappings and can in practice often be obtained using Monte-Carlo simulations. If the underlying dynamics are deterministic and non-Markovian (like in the case of unitary state evolution), care must be taken to render the effective MDP dynamics stochastic and Markovian. For the cases of state preparation and gate compilation, we show it is sufficient to discretize states and to introduce a reshuffling operation of quantum states within a discrete MDP state in order to achieve this goal. This comes at the cost of requiring an additional algorithmic step to go from the optimal policy π* to the optimal program that achieves the control task. Finally, a problem-specific reward \({{{\mathcal{R}}}}\) must be defined that differentiates different policies π. In the case of state preparation, we simply reward landing in the target state by r = 1 and select r = 0 when moving into any other state.

A discrete state space of pure qubit states \(\left\vert \psi \right\rangle =\cos \frac{\theta }{2}\left\vert 0\right\rangle +{{\rm {e}}}^{i\phi }\sin \frac{\theta }{2}\left\vert 1\right\rangle\) is obtained by discretizing the angles (θn, ϕm) ≡ (n, m). The left Bloch sphere illustrates the effect of gate actions H and T on a given state st (green). The transition probabilities \(p({s}^{{\prime} },r| s,a)\) can be obtained by Monte-Carlo simulations. As an example, applying a T gate to any quantum state within the green region results in a deterministic rotation around the equator. Alternatively, applying H introduces the possibility of ending in two different regions (gray). After performing policy iteration, we use the optimal policy π* to generate optimal programs (illustrated in the table) for preparing a desired final state (red) from a given initial state (green).

The optimal program to perform the desired quantum control task is obtained by first solving for the optimal policy π*. Here, we use policy iteration to find π*, but in more complex settings there exist a variety of other techniques that can be used4,53. The optimal policy provides the best action to take in any MDP state by maximizing the value function for all states. The algorithm to generate the optimal program is then to follow the optimal policy, possibly starting from slightly different initial states and taking the most optimal program among them.

In the following, we discuss in detail two applications: state preparation of a desired qubit state using a discrete gate set (without and with external quantum noise) and the compilation of a desired SU(2) qubit gate operation from the same discrete gate set.

Noiseless state preparation of single-qubit states

As a first example, we discuss the noiseless preparation of arbitrary single-qubit states using MDPs. We describe in detail how to render the environmental dynamics stochastic and Markovian by allowing for a probabilistic shuffling within discrete qubit states. This allows us to directly obtain optimal quantum programs via optimal policies π*.

To obtain a finite state space \({{{\mathcal{S}}}}\), we discretize the state space of pure 1-qubit states \(\left\vert \psi \right\rangle =\cos \frac{\theta }{2}\left\vert 0\right\rangle +{{\rm {e}}}^{i\phi }\sin \frac{\theta }{2}\left\vert 1\right\rangle\) with θ ∈ [0, π] and ϕ ∈ [0, 2π) as follows. First, we select a small discretization parameter ϵ = π/k with a positive integer k. Next, we identify polar caps around the north and south poles of the Bloch sphere as the set of all states with θ < ϵ and θ > π−ϵ, respectively, regardless of the value of ϕ. Away from the caps, an MDP state (l, m) is associated with the set of points lϵ ≤ θ ≤ (l + 1)ϵ and mϵ ≤ ϕ ≤ (m + 1)ϵ, where 0 < l < k−1 and 0 ≤ m < 2k−1. We identify every region as a ‘state’ in the MDP and 1-qubit pure states can now only be identified up to some threshold fidelity. For instance, the \(\left\vert 0\right\rangle\) and \(\left\vert 1\right\rangle\) states are identified with the polar caps (0, 0) and (k, 0) with fidelity \({{{\mbox{cos}}}}^{2}\left(\frac{\pi }{2k}\right)\). In other words, using the discrete states in the MDP only allows us to obtain these states up to these fidelities. We identify a finite action space \({{{\mathcal{A}}}}\) with single-qubit unitary operations, or gates. Here, we focus on a native gate set that is already discrete, {I, H, T}. However, one could also choose continuous gate sets such as the rotation gates {RZ(α), RY(α)} and obtain a finite action space via discretization similar to the one used for states on the Bloch sphere.

In our choice of the gateset, I is the identity, H is the Hadamard gate and T is the T gate. We include the identity I to allow the target state to be absorbing by having the agent choose I in that state under the optimal policy. In order to remain in the space of SU(2) matrices, we define H = RY(π/2)RZ(π), which differs from the usual definition by an overall factor of i, and T = RZ(π/4). Note that owing to our alternative gate definitions, we have that H2 = T8 = −1 so that we may obtain up to 3 and 15 consecutive applications of H and T, respectively, in the optimal program.

Noiseless reward structure and environment dynamics

An obvious guess for a reward would be the fidelity between the target state \(\left\vert {\psi }_{{\rm {t}}}\right\rangle \equiv \left\vert ({l}_{\rm {{t}}},{m}_{\rm {{t}}})\right\rangle\) and the prepared state \(\left\vert \phi \right\rangle\), i.e. ∣〈ϕ∣ψt〉∣2. Since this gives a rather high reward for landing in states near the target state, however, we find that the fidelity reward does not work well in practice. Instead, here we consider an even simpler reward structure that assigns r = 1 to the target state and r = 0 to all other states. As we show below, this allows relating the length of optimal programs to the optimal value function \({V}_{\pi }^{* }(s)\).

To finish the MDP specification, we need to estimate the environment dynamics \(p({s}^{{\prime} },r| s,a)\). Since our reward structure specifies a unique reward r to every state \({s}^{{\prime} }\in {{{\mathcal{S}}}}\), these conditional probabilities reduce to \(p({s}^{{\prime} }| s,a)\). We estimate these probabilities by uniformly sampling points on the Bloch sphere and determining the discrete state s they land in. Then we perform each of the actions \(a\in {{{\mathcal{A}}}}\) and determine the resulting states \({s}^{{\prime} }\). Note that continuous states from the same discrete state region s can land in different discrete final state regions \({s}^{{\prime} }\). Discretization thus induces probabilistic Markovian dynamics, \(p({s}^{{\prime} }| s,a)\), on the environment, even though the underlying continuous quantum states undergo deterministic mappings among each other.

Noiseless optimal value function and optimal policy

Let us now discuss the properties of the optimal value function \({V}_{{\pi }^{* }}(s)\). For illustration, we show \({V}_{{\pi }^{* }}(s)\) in Fig. 2 for the gate set {I, H, T} and the goal state \(\left\vert 0\right\rangle\). To interpret V*, we first notice that the optimal policy for the target state is to apply the identity, which yields a reward r = 1 at every time step. Summing the infinite series \({V}_{{\pi }^{* }}({s}_{t})=\mathop{\sum }\nolimits_{k = 0}^{\infty }{\gamma }^{k}\), we obtain (1−γ)−1, which is the highest value of any state on the discretized Bloch sphere. For some generic state \(s\in {{{\mathcal{S}}}}\), the optimal value function is given by

where the elements of the matrix P are given by \({P}_{{s}^{{\prime} },s}=p({s}^{{\prime} }| s,{\pi }^{* }(s))\). A proof of this is given in the Supplementary Material. We now show that V*(s) ≤ V*(st) for all \(s\in {{{\mathcal{S}}}}\). The Markov chain produced by the optimal policy has an absorbing state st, where all discrete states land for a sufficiently large number of steps. The smallest integer K for which the Markovian process converges to a steady state, such that

for all \(s,{s}^{{\prime} }\in {{{\mathcal{S}}}}\), provides an upper bound for the length of the gate sequence from state s to the target state st. Since \({\left({P}^{k}\right)}_{{s}^{{\prime} },s}\le 1\) we find the hierarchy V*(sk+1) ≤ V*(sk), where sk denotes states that reach st after the application of k actions drawn from π*. This property intimately relates the length of the optimal program with the optimal value function \({V}_{{\pi }^{* }}\).

Optimal value landscape across the Bloch sphere using the gates {I, H, T} and goal state \(\left\vert 0\right\rangle\) (red shaded). The color of the state indicates the value of \({V}_{{\pi }^{* }}\), where a brighter color indicates a higher value. In other words, these states are in some sense closer to the target state. Note that patches along the equator have a high value because a single H gate is sufficient to reach the target state.

Algorithm to generate optimal state preparation programs

Using policy iteration allows for finding the optimal policy π* in an MDP. The optimal policy dictates the best action to perform in a given state. We can chain the actions drawn from the optimal policy together to find an optimal sequence of actions, or gates, to reach the target state. In our case, the actions are composed of unitary operations, which deterministically evolve a quantum state (we note that in the presence of quantum noise, the unitary gates are replaced by non-unitary quantum channels). However, due to the discretization, this is no longer true in the MDP, where the states evolve according to the non-trivial probabilities \(p({s}^{{\prime} }| s,a)\). The optimal policy is learned with respect to the stochastic dynamics, and not with respect to the underlying deterministic one. In other words, we are imposing a Markovian structure on essentially non-Markovian dynamics. Therefore, if we simply start in some specific quantum state, and apply a sequence of actions drawn from the optimal policy, we might not necessarily find ourselves in the target (discrete) state. This discrepancy can cause the evolution to get stuck in a loop.

To circumvent this issue, in principle one may allow ‘shuffling’ of the quantum states within a particular discrete state before evolving them under the optimal policy. This is achieved by applying a shuffling transformation \({U}_{{\rm {s}}}^{(i)}:\left\vert \psi \right\rangle \to \left\vert \tilde{\psi }\right\rangle\) such that \(\left\vert \psi \right\rangle \sim \left\vert \tilde{\psi }\right\rangle\) belong to the same discrete state. However, this may increase the length of the gate sequence and lead to poorer bounds on the fidelity, since

Here, the Ui specifies (unitary) actions sampled from the optimal policy and \(\left\vert {\psi }_{i}\right\rangle\), \(\left\vert {\psi }_{i}^{{\prime} }\right\rangle\) are two different initial pure states that belong to the same initial discrete state. On the other hand, without such shuffling, the fidelities in the target states from sequences that only differ in their starting states are the same as the fidelities of the starting states, i.e. \(\langle {\psi }_{i}^{{\prime} }| {\psi }_{i}| =\rangle \langle {\psi }_{i}^{{\prime} }| {U}^{{\dagger} }U| {\psi }_{i}\rangle =\langle {\psi }_{f}^{{\prime} }| {\psi }_{f}\rangle\), where U = ∏iUi. To avoid such shuffling while still producing convergent paths, we sample several paths that lead from the starting state and terminate in the target (discrete) state, discarding sequences that are larger than some acceptable value, e.g. the length K defined by Eq. (4), and report the one with the smallest length as the optimal (i.e. shortest) program. Schematically, this can be described in pseudo-code as in Algorithm 1 (see Supplementary Material). This algorithm can be used to generate optimal programs for any given (approximately universal) single-qubit gate set in both noisy and noiseless cases.

Results for noiseless state preparation

In the following, we use the framework described above to map the problem of quantum state preparation onto a finite and discrete MDP. We focus on using the discrete gateset {I, H, T} to prepare quantum states of the form \({(HT)}^{n}\left\vert 0\right\rangle\) with integer n and to compile general SU(2) gates. We now discuss results for noiseless state preparation, where we employ an MDP to obtain these states up to some fidelity controlled by the discretization with a number of gates much smaller than n.

We use the discrete MDP states (lt(n), mt(n)) corresponding to the 1-qubit states \({\left(HT\right)}^{n}\left\vert 0\right\rangle\) for integers n ≥ 1 as target states of the MDP. The unitary HT peforms a rotation by an angle \(\theta =2\arccos \left(\frac{\cos (7\pi /8)}{\sqrt{2}}\right)\) about an axis \(\frac{1}{\sqrt{17}}\left((5-2\sqrt{2})\hat{{{{\bf{x}}}}}+(7+4\sqrt{2})\hat{{{{\bf{y}}}}}+(5-2\sqrt{2})\hat{{{{\bf{z}}}}}\right)\). These states \({(HT)}^{n}\left\vert 0\right\rangle\) thus lie along an equatorial ring around this axis and states with different n are different since θ is irrational. We choose to investigate state preparation up to n = 1010. Although as their form makes explicit, these states can be reproduced exactly using n many H and T gates, we will use an MDP to obtain them with much fewer gates up to some fidelity controlled by the discretization. The fidelity is defined as \({{{\mathcal{F}}}}=| \langle {\psi }_{t}| \psi | | \rangle\), where \(\left\vert \psi \right\rangle ={\pi }^{* }\left\vert 0\right\rangle\) is obtained from the application of the shown gate sequences, starting from the state \(\left\vert 0\right\rangle\) and \(\left\vert {\psi }_{t}\right\rangle ={(HT)}^{n}\left\vert 0\right\rangle\). This is illustrated in Table 1 where short gate sequences that only use ≈ 10 gates can reproduce states of the form \({(HT)}^{n}\left\vert 0\right\rangle\) for very large values of n.

It should be stressed however that since these states lie along an equatorial ring, the discretization essentially groups a dense subset of states into a finite set of cells. Thus, for some fixed target accuracy, increasing n would simply result in ending up in one of those cells again. For instance, we observe from Table 1 that the states for n = 104 and n = 105 are indeed the same MDP state for the given target accuracy, as are those for n = 108 and n = 109 which are also the same as the MDP state that contains the (starting) \(\left\vert 0\right\rangle\) state so that the optimal policy is to simply apply the identity. Nevertheless, it is not a priori obvious that any compilation scheme for some target accuracy, that would also in principle work in the presence of noise, would output short gate sequences for such states. We observe empirically that the scheme described here does indeed produce fairly short gate sequences.

State preparation in the presence of quantum noise

In this section, we define the MDP for noisy state preparation. Here the quantum state must be described by a density matrix that evolves under noisy quantum channels. In the presence of noise, the quantum state becomes mixed and is described by a density matrix, which for a single qubit can generally be written as

Here, r = (rx, ry, rz) are real coefficients called the Bloch vector and σ = (X, Y, Z) are the Pauli matrices. Since density matrices are semi-definite, it holds that ∣r∣ ≤ 1. If ρ is a pure state, then ∣r∣ = 1, otherwise ∣r∣ < 1. Pure states can thus be interpreted as points on the surface of the Bloch sphere, whereas mixed states correspond to points within the Bloch sphere. The maximally mixed state ρ = I/2 corresponds to the origin. To find r, one can calculate the expectation values of each Pauli operator

where r ≡ ∣r∣ ∈ [0, 1], θ ∈ [0, π], and ϕ ∈ [0, 2π). State discretization is performed in analogy to the previous section. First, we choose ϵ = π/k and δ = 1/k for some positive integer k. Then, the set of points lϵ ≤ θ ≤ (l + 1)ϵ, mϵ ≤ ϕ ≤ (m + 1)ϵ, and qδ ≤ r ≤ (q + 1)δ for integers 0 < l < k − 1, 0 ≤ m < 2k −1, and 0 ≤ q ≤ k−1 constitute the same discrete MDP state s = (l, m, q). As before, the polar regions l = 0, k−1 are special and are described by the set of integers s = (l, m = 0, q). This discretization corresponds to nesting concentric spheres and setting the discrete MDP states s to be the 3-dimensional regions between them.

Let us now introduce the action space \({{{\mathcal{A}}}}\) in the presence of noise. We model noisy gates using a composition of a unitary gate U and a noisy quantum channel described by a set of Kraus operators that define a completely positive and trace-preserving (CPTP) map as \({{{\mathcal{E}}}}(\rho )={\sum }_{k}{E}_{k}\rho {E}_{k}^{{\dagger} }\) with \({\sum }_{k}{E}_{k}{E}_{k}^{{\dagger} }={\mathbb{I}}\). Application of a noisy quantum channel can shrink the magnitude r of the Bloch vector as the state becomes more mixed. Evolution under a unitary gate U in this noisy channel results in

We here again consider the discrete gateset {I, H, T}. Once we specify the type of noise via a set of Kraus operators {Ek}, its only effect on our description of the MDP is to change the transition probability distributions \(p({s}^{{\prime} }| s,a)\). While noise can change the optimal policies π*, we may nevertheless solve for them using the same procedure as in the noiseless case.

Noisy reward structure and environment dynamics

The reward structure for noisy state preparation considers the purity of the state. This is to account for the fact that there may be no gate sequence that results in a state with a high enough purity to land in the pure target state. As a result, assigning a reward of r = + 1 to the pure target state and 0 to all other states can lead to poor convergence. Instead, we assign the reward as follows. First, the pure target state ρt is one of the MDP states (lt, mt, q = k−1). Then, for landing in the MDP state with the correct angles (\({l}_{{\rm {t}}},{m}_{{\rm {t}}},{q}^{{\prime} }\) we assign a reward of \(r={q}^{{\prime} }/k\) proportional to the purity. For all other states, we assign the reward r = 0. We thus reward gate sequences that move the state into the target direction even if they do not land in the pure target state, while still encouraging states with higher purity.

To obtain the environmental dynamics \(p({s}^{{\prime} }| s,a)\) in the presence of quantum noise, we again perform Monte-Carlo simulations and uniformly draw random continuous quantum states ρ(r, θ, ϕ) and assign them to their discrete MDP state s. Then, we apply deterministic noisy gates \(a\in \{U{{{\mathcal{E}}}}\}\) with U = {I, H, T} and record the obtained discrete states \({s}^{{\prime} }\) from which we obtain \(p({s}^{{\prime} }| s,a)\). Due to the noise, we find transitions to states \({s}^{{\prime} }\) with lower purity than the initial state s. Note that the Markovian stochastic nature of the probability distribution p arises solely from the discretization of the continuous quantum states to which we apply the noisy gate actions. The randomness due to noise is fully captured within the deterministic CPTP maps between mixed-state density matrices.

Noisy optimal value function and optimal policy

One can expect the optimal value function \({V}_{{\pi }^{* }}\) for a noisy evolution to take on smaller values since the rewards are smaller. For a simplified noise model consisting of only a depolarizing quantum channel \({{{\mathcal{E}}}}(\rho )=(1-p)\rho +\frac{p}{3}(X\rho X+Y\rho Y+Z\rho Z)\), the resulting optimal value function is simply uniformly shrunk compared to the noiseless version. Since the change is uniform across all values, the optimal policy for depolarizing noise is unchanged from the noiseless setting. This is different for more realistic noise models such as the amplitude and dephasing channels we use below, in which case one needs to rederive the optimal policy.

Results for noisy state preparation

We now consider the task of approximating states of the form \({(HT)}^{n}\left\vert 0\right\rangle\) using a noisy gate set. The set is built by composing the unitaries {I, H, T} with a quantum noise channel that we choose to consist of amplitude damping and dephasing noise. Since quantum noise modifies the environmental transition probabilities \(p({s}^{{\prime} }| s,a)\), the optimal policy \({\pi }_{\,{{\rm{noisy}}}\,}^{* }\) that we obtain via policy iteration is different from the optimal policy \({\pi }_{\,{{\rm{noiseless}}}\,}^{* }\) of the noiseless MDP. Finally, we find optimal gate sequences via Algorithm 1 (see Supplementary Material) and compare the resulting shortest gate sequences derived from \({\pi }_{\,{{\rm{noise}}}\,}^{* }\) with those from \({\pi }_{\,{{\rm{noiseless}}}\,}^{* }\). Importantly, we observe that an agent that was trained using the noisy transition probabilities consistently prepares the target state with higher fidelity than an agent that lacks knowledge of the noise channel. The optimal policy π* thus adapts to the noise and produces optimal programs that prepare the target state with higher fidelity than a policy that is trained on the noiseless MDP.

Let us first describe the noise channel and the corresponding Kraus operators that we used to model the quantum noise. The noise observed in current quantum computers is to a good approximation described by amplitude damping and dephasing channels. The amplitude damping channel is described by the two Kraus operators

with 0 ≤ γ ≤ 1. Physically, we can interpret this channel as causing a qubit in the \(\left\vert 1\right\rangle\) state to decay to the \(\left\vert 0\right\rangle\) state with probability γ. In current quantum computing devices, the relaxation time, T1, describes the timescale of such decay processes. For a given T1 time and a characteristic gate execution time τg, we parametrize

Note that the application of the amplitude damping channel also leads to the dephasing of the off-diagonal elements of the density matrix in the Z basis with timescales T2 = 2T1. The dephasing channel takes the form \({{{{\mathcal{E}}}}}_{{{\rm{dephasing}}}}(\rho )=(1-p)\rho +pZ\rho {Z}^{{\dagger} }\) and is described by the Kraus operators \({A}_{0}=\sqrt{1-p}\,{\mathbb{1}}\) and \({A}_{1}=\sqrt{p}Z\). This channel leads to pure phase damping of the off-diagonal terms of the density matrix in the Z basis, and is described by a dephasing time, T2.

We use Pyquil54 to construct a noise channel consisting of a composition of these two noise maps by specifying the T1 and T2 times as well as the gate duration τg. The amplitude damping parameter γ is set by T1 using Eq. (10). Since this also results in phase damping of the off-diagonal terms of the density matrix (in the Z basis), the dephasing time T2 is upper limited by 2T1. We thus parametrize the dephasing channel parameter describing any additional pure dephasing as

The dephasing channel thus describes dephasing leading to T2 < 2T1 and acts trivially if T2 is at its upper bound T2 = 2T1. In the following, we consider T1 = T2 such that the dephasing channel acts non-trivially on the quantum state.

In Table 2, we present results up to n = 1010 that includes the shortest gate sequences found by the optimal policies of noisy and noiseless MDP. We also compare the final state fidelities produced by these optimal circuits. The fidelities \({{{\mathcal{F}}}}\) that are listed in the table are found by applying the optimal gate sequences for a given n to the initial state \(\left\vert 0\right\rangle\). Since the resulting states are mixed, we calculate the fidelity between the target state σ and the state resulting from an optimal gate sequence ρ as

We list both the gate sequences found by the noiseless MDP, the agent whose underlying probability distribution is constructed from exact unitary gates, and the noisy MDP, whose transition probabilities are generated from noisy gates considering combined amplitude damping and dephasing error channels. We set the relaxation and dephasing times to T1 = T2 = 1 μs and the gate time to τg = 200 ns. While the value for τg is typical for present day superconducting NISQ hardware, the values of T1, T2 are about two orders of magnitude shorter than typical values on today’s NISQ hardware, where T1, T2 ≃ 100 μs. We choose such stronger noise values in order to highlight the difference in gate sequences and resulting fidelities produced by the optimal policies π* for noisy and noiseless MDPs. We expect that this result is generic and robust when considering MDPs for multiple qubits, where two-qubit gate errors are expected to lead to pronounced noise effects even at current hardware noise levels.

The results in Table 2 demonstrate that even in the presence of strong noise, the noisy MDP is able to provide short gate sequences that approximate the target state reasonably well. Importantly, for all values of n shown (except for n = 104), the optimal policy of the noisy MDP \({\pi }_{\,{{\rm{noisy}}}\,}^{* }\) yields a gate sequence that results in a higher fidelity than the gate sequence obtained from \({\pi }_{\,{{\rm{noiseless}}}\,}^{* }\) of the noiseless MDP when applied in the presence of noise. This shows that noise can be mitigated by adapting the gate sequence according to the noise experienced by the qubit.

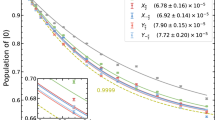

In Fig. 3 we compare the gate sequences and fidelities obtained from the optimal policies of noisy and noiseless MDPs for a fixed value of n = 107 as a function of T1 = T2. We fix the gate time to τg = 200 ns when generating the Kraus operators using Eqs. (10) and (11). To obtain \({\pi }_{\,{{\rm{noise}}}\,}^{* }\), we first generate the transition probabilities \(p({s}^{{\prime} }| s,a)\) for each value of T1, T2 according to the corresponding noise map. We then use policy iteration to find the optimal policy. The fidelity \({{{\mathcal{F}}}}\) is calculated by applying the shortest gate sequence obtained using Algorithm 1 (see Supplementary Material) to the initial state \(\left\vert 0\right\rangle\) in the presence of the quantum noise channel with parameters T1 and T2. We observe that the agent trained on the noisy MDP outperforms the noiseless one for all noise strengths. This indicates that by learning the noise channel the agent adapts to the noise and finds gate sequences that yield higher fidelities in that channel.

State preparation fidelity \({{{\mathcal{F}}}}(\sigma )\) as a function of noise strength T1 = T2 using gate sequences obtained from the optimal policies \({\pi }_{\,{{\rm{noisy}}}\,}^{* }\) (orange) and \({\pi }_{\,{{\rm{noiseless}}}\,}^{* }\) (blue) of the noisy and noiseless MDP, respectively. The target state is \({\psi }_{t}={(HT)}^{n}\left\vert 0\right\rangle\) for fixed n = 107. The noisy policy gives gate sequences (as shown) that are different from the noiseless case and that consistently yield higher fidelities. The optimal noisy gate sequence is HTHTHTH for all times T1 = T2 ≥ 60 μs. The point at infinity represents the noiseless case and corresponds to the transition probabilities learned by the noiseless MDP.

Compilation of single-qubit gates

In the previous sections, we considered an agent–environment interaction in which we identified Hilbert space as the state space, and the space of SU(2) gates as the action space. Shifting our attention to the problem of quantum gate compilation, we now identify both the state and action spaces with the space of SU(2) matrices, where for convenience we ignore an overall U(1) phase from the true group of single-qubit gates U(2). We first consider an appropriate coordinate system to use and discuss why the quaternions are better suited to this task than Euler angles. We again focus on the gateset {I, H, T}, and modify the reward structure slightly so that we now have to work with the probabilities \(p({s}^{{\prime} },r| s,a)\) instead of the simpler \(p({s}^{{\prime} }| s,a)\) as in the previous section.

State and action space for gate compilation

Here, we again consider the gate set {I, H, T} and choose an appropriate coordinate system. One naive choice is to parametrize an arbitrary U ∈ SU(2) using the ZYZ-Euler angle decomposition U = RZ(α)RY(β)RZ(γ) with angles α, β, and γ. Note that for β = 0, there is a continuous degeneracy of choices in α and γ to specify some RZ(δ) with α + γ = δ. A conventional choice is α = γ = δ/2. Under the action of T, \(T:U\to {U}^{{\prime} }=T\,U=RZ({\alpha }^{{\prime} })RY({\beta }^{{\prime} })RZ({\gamma }^{{\prime} })\), or equivalently \(T:(\alpha ,\beta ,\gamma )\to ({\alpha }^{{\prime} },{\beta }^{{\prime} },{\gamma }^{{\prime} })\), the ZYZ-coordinates transform rather simply as \({\alpha }^{{\prime} }=\alpha +\pi /4\), \({\beta }^{{\prime} }=\beta\), \({\gamma }^{{\prime} }=\gamma\). The action of H, however, results in a non-volume preserving operation for which the Jacobian of the transformation \(H:(\alpha ,\beta ,\gamma )\to ({\alpha }^{{\prime} },{\beta }^{{\prime} },{\gamma }^{{\prime} })\) diverges:

This implies that for pathological values where \(\cos (\alpha )\sin (\beta )=\pm 1\), a unit hypercube in the discretized (α, β, γ) space gets mapped to a region that covers indefinitely many unit hypercubes in the discretized \(({\alpha }^{{\prime} },{\beta }^{{\prime} },{\gamma }^{{\prime} })\) space. A single state s thus gets mapped to an unbounded number of possible states \({s}^{{\prime} }\), causing \(p({s}^{{\prime} }| s,a=H)\) to be arbitrary small. This may prevent the agent from recognizing an optimal path to valuable states, since even if the quantity \((r+\gamma {V}_{\pi }({s}^{{\prime} }))\) is particularly large for some states \({s}^{{\prime} }\), this quantity gets multiplied by the negligible factor \(p({s}^{{\prime} }| s,a=H)\), and therefore has a very small contribution in an update rule such as Eq. (2).

These problems can be overcome by switching to using quaternions as our coordinate system. Unlike the ZYZ-Euler angles, the space of quaternions is in one-to-one correspondence with SU(2). Given some

with real coefficients a, b, c, d that obey a2 + b2 + c2 + d2 = 1, the corresponding quaternion is given simply as q = (a, b, c, d). For quaternions, the mappings T and H are both volume preserving with Jacobians equal to one. The total number of states \({s}^{{\prime} }\) that can result from acting with either T or H in state s is therefore bounded above. Suppose we choose our discretization such that the grid spacing along each of the 4 axes of the quaternionic space is the same. Then, since a d-dimensional hypercube can intersect with at most 2d equal-volume hypercubes, a state s can be mapped to at most 16 possible states \({s}^{{\prime} }\).

Reward structure and environment dynamics for gate compilation

Some natural measures of overlap between two unitaries include the Hilbert–Schmidt inner product tr(U†V), and since we work with quaternions, the quaternion distance \(| q-{q}^{{\prime} }|\). However, neither does the Hilbert–Schmidt inner product monotonically increase nor does the quaternion distance monotonically decrease, along the shortest {H, T} gate sequence. We showed previously how assigning a reward structure of +1 to some target state, and 0 to all other states, made it possible to relate the optimal value function to the length of the optimal path. Instead of specifying a reward of +1 in some target state and 0 in every other state however, we now assign a reward of +1 whenever the evolved quaternion q satisfies ∣q−q*∣ < ϵ, for some ϵ > 0 and q* is the target quaternion, and 0 otherwise.

We could estimate the dynamics by uniformly randomly sampling quaternions, track which discrete state the sampled quaternions belong to, evolve them under the actions, and track the resultant discrete state and reward obtained as a result, just as we did in the previous sections. However, here we now estimate the environment dynamics by simply rolling out gate sequences. Each rollout is defined as starting from the identity gate, then successively applying either an H or T gate with equal probability until some fixed number K of actions have been performed. The probabilities for the identity action \(p({s}^{{\prime} },r| s,a=I)\) are simply estimated by recording that \(({s}^{{\prime} },a=I)\) led to \(({s}^{{\prime} },r)\) at each step that we sample \(({s}^{{\prime} },r)\) when performing some other action a ≠ I in some other state \(s\,\ne\, {s}^{{\prime} }\). The number of actions per rollout K is set by the desired accuracy, which the Solovay–Kitaev theorem informs us is O(polylog(1/ϵ))15, and in our case has an upper bound given by Eq. (4). Estimating the environment dynamics in this manner is similar in spirit to off-policy learning in typical reinforcement learning algorithms, such as Q-learning4.

Algorithm to generate optimal programs for gate compilation

Solving the constructed MDP through policy iteration, we arrive at the optimal policy just as before. We now chain the optimal policies together to form optimal gate compilation sequences, accounting for the fact that while the dynamics of our constructed MDP are stochastic, the underlying evolution of the unitary states is deterministic. The procedure we use for starting with the identity gate and terminating, with some accuracy, at the target state is outlined in pseudo-code in Algorithm 2 (see Supplementary Material), where the length of the largest sequence K is dictated by Eq. (4), and in our experiments we took 100 rollouts.

The accuracy with which we would obtain the minimum length action sequence in Algorithm 2 (see Supplementary Material) need not necessarily satisfy the bound ϵ set by the reward criterion, r = 1 for ∣q−q*∣ < ϵ, for reasoning similar to the shuffling discussed in the context of state preparation above. This is why we require Algorithm 2 to report the minimum length action sequence that also satisfies the precision bound. In practice, we found that this was typically an unnecessary requirement, and even when the precision bound was not satisfied, the precision did not stray too far from the bound. It should be emphasized that due to the shuffling effect, there is no a priori guarantee that the optimal sequence returned by Algorithm 2 needs even exist since the precision bound is not guaranteed to exist. In practice, however, we find the algorithm to work quite well in producing optimal sequences that correspond to the shortest possible gate sequences to prepare the target quaternions q*.

Results for gate compilation

Finally, we consider the problem of approximating general SU(2) gates. To benchmark the compilation sequences found by using an MDP, we find the shortest gate sequences for compilation to some specified precision using a brute-force search that yields the smallest gate sequence that satisfies ∣q−q*∣ < ϵ for some ϵ > 0 with the smallest value of ∣q−q*∣, where q is the prepared quaternion and q* is the target quaternion.

As an experiment, we drew 30 Haar random SU(2) matrices and found their compilation sequences via the two methods described above. We set ϵ = 0.3, estimated the environment dynamics using 1000 rollouts where each rollout is 50 actions long, and each action being a uniform draw between H and T. The findings are presented in Table 3, where the gate sequences are to be read right to left. We find that although the two approaches sometimes yield different sequences, they agree in their length and produce quaternions that fall within ϵ of the target quaternion. Based on these results, we expect in general that the two approaches will produce comparable length sequences and target fidelities, though not necessarily equal.

As a comparison, we use the Ross–Selinger algorithm21, implemented through the gridsynth55 program, to approximate Haar random SU(2) matrices. We decompose the quaternion into its ZXZ-Euler angle decomposition U = RZ(α)RX(β)RZ(γ) = RZ(α)HRZ(β)HRZ(γ) so that each single-qubit Z-rotation can be compiled individually. The full unitary is then the concatenation of each rotation. The runtime of the Ross–Selinger algorithm is much more favorable compared to the MDP approach described here (poly(log(1/ϵ)) vs. poly(1/ϵ)). However, for gate compilation accuracies comparable to those found by the optimal MDP (second column from the right in Table 3), we observe that the Ross–Selinger gate sequences are on average about 8.7 times longer than those found by the MDP. We describe this comparison in more detail in Supplementary Material.

Discussion

We have shown that the tasks of single-qubit state preparation and gate compilation can be modeled as finite MDPs yielding optimally short gate sequences to prepare states or compile gates up to some desired accuracy. These optimal sequences were found to be comparable with independently calculated shortest gate sequences for the same tasks, often agreeing with them exactly. Additionally, we investigated state preparation in the presence of amplitude damping and dephasing noise. We found that an agent that is trained in a noisy environment can make use of the learned information about the noise and produce noise-adapted optimal gate sequences with higher target state fidelities. This work therefore provides strong evidence that more complicated quantum programming tasks can also be successfully modeled as MDPs. In scenarios where the state or action spaces grow too large for dynamic programming to be applicable, or where the environment dynamics cannot be accurately learned by the straightforward Monte-Carlo sampling we use in our work, it is therefore highly promising to apply reinforcement learning to find optimally short circuits for quantum control tasks. Future work should be directed towards using dynamic programming and reinforcement learning methods for noiseless and noisy state preparation and gate compilation for several coupled qubits.

We provide the required programs for qubit state preparation as open-source software, and we make the corresponding raw data of our results openly accessible56.

Data availability

The data supporting other findings of this study are available from the corresponding authors upon reasonable request.

Code availability

The source code and data to generate the figures in the paper are provided freely at https://doi.org/10.6084/m9.figshare.19833436.v3.

References

Norvig, P. & Russell, S. J. Artificial Intelligence: A Modern Approach (Pearson Education Limited, 2016).

Shalev-Schwartz, S. & Ben-David, S. Understanding Machine Learning: From Theory to Algorithms (Cambridge University Press, 2014).

Goodfellow, I., Bengio, Y. & Courville, A. Deep Learning (MIT Press, 2016).

Sutton, R. S. & Barto, A. G. Reinforcement Learning: An Introduction, 2nd edn (Bradford Books, Cambridge, MA, 2018).

Bellman, R. On the theory of dynamic programming. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 38, 716 (1952).

Fösel, T., Tighineanu, P., Weiss, T. & Marquardt, F. Reinforcement learning with neural networks for quantum feedback. Phys. Rev. X 8, 031084 (2018).

McKiernan, K. A., Davis, E., Alam, M. S. & Rigetti, C. Automated quantum programming via reinforcement learning for combinatorial optimization. Preprint at http://arxiv.org/abs/1908.08054 (quant-ph) (2019).

Bukov, M. et al. Reinforcement learning in different phases of quantum control. Phys. Rev. X 8, 031086 (2018).

Bukov, M. Reinforcement learning for autonomous preparation of Floquet-engineered states: inverting the quantum Kapitza oscillator. Phys. Rev. B 98, 224305 (2018).

August, M. & Hernández-Lobato, J. M. Taking gradients through experiments: Lstms and memory proximal policy optimization for black-box quantum control. In Yokota, R., Weiland, M., Shalf, J., Alam, S. (eds) High Performance Computing. ISC High Performance 2018. Lecture Notes in Computer Science Vol. 11203 (2018). Springer, Cham.

Albarrán-Arriagada, F., Retamal, J. C., Solano, E. & Lamata, L. Measurement-based adaptation protocol with quantum reinforcement learning. Phys. Rev. A 98, 042315 (2018).

Zhang, X.-M., Wei, Z., Asad, R., Yang, X.-C. & Wang, X. When does reinforcement learning stand out in quantum control? a comparative study on state preparation. npj Quantum Inf. 5, 85 (2019).

An, Z. & Zhou, D. L. Deep reinforcement learning for quantum gate control. EPL 126, 60002 (2019).

Niu, M. Y., Boixo, S., Smelyanskiy, V. N. & Neven, H. Universal quantum control through deep reinforcement learning. npj Quantum Inf. 5, 33 (2019).

Dawson, C. M. & Nielsen, M. A. The Solovay–Kitaev algorithm. Preprint at http://arxiv.org/abs/quant-ph/0505030 (2005).

Shende, V. V., Bullock, S. S. & Markov, I. L. Synthesis of quantum logic circuits. IEEE Trans. Comput.-Aided Design 25, 1000–1010 (2006).

Peterson, E. C., Crooks, G. E. & Smith, R. S. Fixed-depth two-qubit circuits and the monodromy polytope. Quantum 4, 247 (2020).

Kliuchnikov, V., Bocharov, A., Roetteler, M. & Yard, J. A framework for approximating qubit unitaries. Preprint at http://arxiv.org/abs/1510.03888 (quant-ph) (2015).

Kliuchnikov, V., Maslov, D. & Mosca, M. Fast and efficient exact synthesis of single qubit unitaries generated by Clifford and t gates. Quantum Inf. Comput. 13, 607–630 (2013).

Vatan, F. & Williams, C. Optimal quantum circuits for general two-qubit gates. Phys. Rev. A 69, 032315 (2004).

Ross, N. J. & Selinger, P. Optimal ancilla-free clifford+t approximation of z-rotations. Quantum Inf. Comput. 16, 901–953 (2016).

Yao, J., Bukov, M. & Lin, L. Policy gradient based quantum approximate optimization algorithm. In Proc. First Mathematical and Scientific Machine Learning Conference, Proc. Machine Learning Research, Vol. 107 605–634 (eds Lu, J. & Ward, R.) (PMLR, 2020).

Wauters, M. M., Panizon, E., Mbeng, G. B. & Santoro, G. E. Reinforcement-learning-assisted quantum optimization. Phys. Rev. Res. 2, 033446 (2020).

Lockwood, O. Optimizing quantum variational circuits with deep reinforcement learning. Preprint at https://doi.org/10.48550/ARXIV.2109.03188 (2021).

Jerbi, S., Gyurik, C., Marshall, S. C., Briegel, H. J. & Dunjko, V. Parametrized quantum policies for reinforcement learning. Preprint at https://doi.org/10.48550/ARXIV.2103.05577 (2021).

Skolik, A., Jerbi, S. & Dunjko, V. Quantum agents in the gym: a variational quantum algorithm for deep q-learning. Quantum 6, 720 (2022).

Wang, D., You, X., Li, T., & Childs, A. M. Quantum Exploration Algorithms for Multi-Armed Bandits. Proceedings of the AAAI Conference on Artificial Intelligence, 35, 10102–10110. https://ojs.aaai.org/index.php/AAAI/article/view/17212.1 (2021).

Sutter, D., Nannicini, G., Sutter, T. and Woerner, S. Quantum speedups for convex dynamic programming. Preprint at https://doi.org/10.48550/ARXIV.2011.11654 (2020).

Lumbreras, J., Haapasalo, E. & Tomamichel, M. Multi-armed quantum bandits: exploration versus exploitation when learning properties of quantum states. Quantum 6, 749 (2022).

Lamata, L. Quantum machine learning and quantum biomimetics: a perspective. Mach. Learn. Sci. Technol. 1, 033002 (2020).

Lamata, L. Quantum machine learning implementations: proposals and experiments. Adv. Quantum Technol. 6, https://doi.org/10.1002/qute.202300059 (2023).

Melnikov, A. A., Sekatski, P. & Sangouard, N. Setting up experimental bell tests with reinforcement learning. Phys. Rev. Lett. 125, 160401 (2020).

Sivak, V. V. et al. Model-free quantum control with reinforcement learning. Phys. Rev. X 12, 011059

Porotti, R., Tamascelli, D., Restelli, M. & Prati, E. Coherent transport of quantum states by deep reinforcement learning. Commun. Phys. 2, 61 (2019).

M.-Z. A. et al. Experimentally realizing efficient quantum control with reinforcement learning. Sci China Phys Mech. 65, 250312 (2022).

et al, L. G. A tutorial on optimal control and reinforcement learning methods for quantum technologies. Phys. Lett. A 434, 128054 (2022).

Mackeprang, J., Dasari, D. B. R. & Wrachtrup, J. A reinforcement learning approach for quantum state engineering. Quantum Mach. Intell. 2, 5 (2020).

Paler, A., Sasu, L. M., Florea, A. & Andonie, R. Machine learning optimization of quantum circuit layouts. ACM Trans Quantum Computing 4, 1–25 (2023).

Pozzi, M. G., Herbert, S. J., Sengupta, A. & Mullins, R. D. Using reinforcement learning to perform qubit routing in quantum compilers. ACM Trans Quantum Computing 3, 1–25 (2022).

Cincio, L., Rudinger, K., Sarovar, M. & Coles, P. J. Machine learning of noise-resilient quantum circuits. PRX Quantum 2, 010324 (2021).

Marquardt, F. Machine learning and quantum devices. SciPost Phys. Lect. Notes 29, https://doi.org/10.21468/SciPostPhysLectNotes.29 (2021).

Moro, L., Paris, M. G. A., Restelli, M. & Prati, E. Quantum compiling by deep reinforcement learning. Commun. Phys. 4, 178 (2021).

Temme, K., Bravyi, S. & Gambetta, J. M. Error mitigation for short-depth quantum circuits. Phys. Rev. Lett. 119, 180509 (2017).

Li, Y. & Benjamin, S. C. Efficient variational quantum simulator incorporating active error minimization. Phys. Rev. X 7, https://doi.org/10.1103/PhysRevX.7.021050 (2017).

Mari, A., Shammah, N. & Zeng, W. J. Extending quantum probabilistic error cancellation by noise scaling. Phys. Rev. A 104, 052607 (2021).

Lowe, A. et al. Unified approach to data-driven quantum error mitigation. Phys. Rev. Res. 3, 033098 (2021).

Cai, Z. et al. Quantum error mitigation. Preprint at http://arxiv.org/abs/2210.00921 (quant-ph) (2022).

Viola, L. & Knill, E. Random decoupling schemes for quantum dynamical control and error suppression. Phys. Rev. Lett. 94, 060502 (2005).

Khodjasteh, K. & Viola, L. Dynamically error-corrected gates for universal quantum computation. Phys. Rev. Lett. 102, 080501 (2009).

Abdelhafez, M., Schuster, D. I. & Koch, J. Gradient-based optimal control of open quantum systems using quantum trajectories and automatic differentiation. Phys. Rev. A 99, 052327 (2019).

Ye, Y. The simplex and policy-iteration methods are strongly polynomial for the Markov decision problem with a fixed discount rate. Math. Oper. Res. 36, 593 (2011).

Scherrer, B. Improved and generalized upper bounds on the complexity of policy iteration. Mathematics of Operations Research 41, 3 (2016).

François-Lavet, V., Henderson, P., Islam, R., Bellemare, M. G. & Pineau, J. An introduction to deep reinforcement learning. Found. Trends® Mach. Learn. 11, 219 (2018).

Smith, R. S., Curtis, M. J. & Zeng, W. J. A practical quantum instruction set architecture. Preprint at http://arxiv.org/abs/1608.03355 (quant-ph) (2016).

Selinger, P. & Ross, N. J. Exact and approximate synthesis of quantum circuits (accessed 31 July 2023). Version 0.3.0.4 released 2018/11/05. https://www.mathstat.dal.ca/~selinger/newsynth/ (2012–2018)

Alam, M. S., Berthusen, N. & Orth, P. P. Quantum logic gate synthesis as a Markov decision process. https://doi.org/10.6084/m9.figshare.19833436.v3 (2022).

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by the U.S. Department of Energy, Office of Science, National Quantum Information Science Research Centers, Superconducting Quantum Materials and Systems Center (SQMS) under contract No. DE-AC02- 07CH11359. This work was partially conducted (N.F.B., P.P.O.) at Ames National Laboratory which is operated for the U.S. Department of Energy by Iowa State University under Contract No. DE-AC02-07CH11358. M.S.A. was supported by Rigetti Computing during the initial stages of this work, which resulted in an initial version of the manuscript that was posted on the preprint server arXiv. M.S.A. is currently supported under contract No. DE-AC02- 07CH11359 through NASA-DOE interagency agreement SAA2-403602, and by USRA NASA Academic Mission Services under contract No. NNA16BD14C. M.S.A. would like to thank Erik Davis and Eric Peterson for valuable insights and useful feedback throughout the development of this work. Previous work with Keri McKiernan, Erik Davis, Chad Rigetti and Nima Alidoust directly inspired this current investigation. Joshua Combes and Marcus da Silva provided early feedback and encouragement to explore this work. P.P.O. acknowledges useful discussions with Derek Brandt.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

M.S.A. devised the project and performed the calculation in the noiseless case. N.F.B. and P.P.O. performed calculations of noisy state preparation. All authors contributed to the analysis of the results and the writing of the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons license and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Alam, M.S., Berthusen, N.F. & Orth, P.P. Quantum logic gate synthesis as a Markov decision process. npj Quantum Inf 9, 108 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41534-023-00766-w

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41534-023-00766-w