Abstract

We design a quantum method for classical information compression that exploits the hidden subgroup quantum algorithm. We consider sequence data in a database with a priori unknown symmetries of the hidden subgroup type. We prove that data with a given group structure can be compressed with the same query complexity as the hidden subgroup problem, which is exponentially faster than the best-known classical algorithms. We moreover design a quantum algorithm that variationally finds the group structure and uses it to compress the data. There is an encoder and a decoder, along the paradigm of quantum autoencoders. After the training, the encoder outputs a compressed data string and a description of the hidden subgroup symmetry, from which the input data can be recovered by the decoder. In illustrative examples, our algorithm outperforms the classical autoencoder on the mean squared value of test data. This classical-quantum separation in information compression capability has thermodynamical significance: the free energy assigned by a quantum agent to a system can be much higher than that of a classical agent. Taken together, our results show that a possible application of quantum computers is to efficiently compress certain types of data that cannot be efficiently compressed by current methods using classical computers.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Information compression is the ubiquitous task of reducing data size by appropriate encoding, increasing information storage and transmission efficiency1. A prominent method of compression is to employ autoencoders2,3, artificial neural networks that automatically learn to compress unlabeled data without prior knowledge of the underlying patterns. Exploiting a bottleneck structure, an autoencoder can automatically extract essential features as compressed data in such a manner that the original data can be reconstructed4,5,6.

Recently, the quantum version of autoencoders, to our knowledge first proposed independently in refs. 7,8, has similarly been applied to encode9, compress7,8,10, classify and denoise11 quantum data and been implemented experimentally12,13,14,15,16. Quantum autoencoders can, via unitary circuits, compress data hidden in quantum superpositions, but it is natural to wonder if they can also be valuable in compressing classical data.

Quantum algorithms are indeed able to extract certain features in data that are not efficiently accessible to classical computers. For instance, the quantum period finding algorithm17,18,19 is exponentially faster than the best current classical algorithms in identifying the period of a function. More generally, the Abelian hidden subgroup problem (HSP) represents a broad class of problems (including period finding) that do not have known efficient classical algorithms, whereas efficient quantum algorithms often exist20,21,22,23,24.

Can that quantum speedup on HSPs be turned into an advantage for information compression? To tackle this question, we combine quantum autoencoders and the quantum HSP algorithm to create a concrete algorithm to compress data with symmetries of the HSP type.

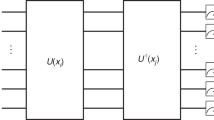

We prove an exponential speedup in query complexity of quantum algorithms in data compression with symmetries of the hidden subgroup type, extending the quantum computational advantage in HSP to data compression. Then we extend this algorithm to a variational quantum auto-encoder (Fig. 1) by designing a parameterized quantum circuit for HSP, making the variational algorithm capable of finding the hidden subgroup automatically. This is achieved by establishing a parameterized quantum circuit ansatz for quantum Fourier transforms that covers a wide range of the Abelian HSP case. We demonstrate the algorithm explicitly on simple compression examples where classical computers are used to simulate small quantum computers.

Our quantum auto-encoder first applies a parametrized hidden sub-group problem (HSP) circuit using an oracle \({U}_{f}\left\vert i\right\rangle \left\vert 0\right\rangle =\left\vert i\right\rangle \left\vert f(i)\right\rangle\) and a parametrized quantum Fourier transform \({{\rm{QFT}}}_{\overrightarrow{\theta }}\) for T times to extract the hidden subgroup structure as features s. \({W}_{\overrightarrow{\theta }}\) is a parameterized gate that permutes qubits to search over broader range of group structures. The parameters \(\overrightarrow{\theta }\) are tuned using gradient descent until the circuit identifies features s representing reversible compressions of the data from the given source.

Our algorithm opens a new direction for quantum machine learning: combining quantum algorithms with quantum autoencoders to achieve more efficient extraction of features. The algorithm exhibits a significant advantage for quantum computers in compressing sequential data over its classical counterpart. Furthermore, this computational advantage in compression can then be mapped to a thermodynamic advantage of energy harvesting, where an intelligent extractor with access to a quantum computer can extract more work within a limited amount of time.

Results

We first examine the scenario with a fixed group structure in sequential data. Our analysis demonstrates that quantum algorithms can achieve exponential acceleration in compressing this specific type of sequential data. Next, we extend our examination to include situations with indeterminate group structures. In these cases, we introduce a variational quantum algorithm capable of autonomously searching for the appropriate group structures. These structures reveal hidden subgroup symmetries within the sequential data.

Compression with respect to fixed group structure

Time series data in databases and compression via symmetry

We consider a database \({\mathcal{Q}}\) storing discrete time series (or sequential data) generated from a source of length N. For simplicity, (detailed reason in Supplementary Note A), we assume N = 2n for an integer n. The data is represented as an ordered sequence \(\{{x}_{0},{x}_{1},\ldots ,{x}_{i},\ldots ,{x}_{{2}^{n}-1}\}\), where each data point xi ∈ {0, 1}m is a bit string of length m. Using binary representation, we identify any index i and a binary string i = i1i2…in = τ(i). Querying \({\mathcal{Q}}\) on i yields the value xi, denoted as \({\mathcal{Q}}(i)={x}_{i}\). If each sequence is generated by a function f, such that xi = f(i) for all i, then the data can be compressed as a description of f, which we refer to as the generating function of the time series.

Without fully recognizing the exact generating function, the data in the database can still be compressed, e.g. by identifying duplicated entries (see Methods for an example). Different levels of knowledge of the function result in varying compression ratios. For instance, a data sequence generated by function f with periodicity can be compressed by retaining only the first period and marking the remaining indices free to use. If an index can be overwritten, we call it free. Even without knowing the exact function, identifying periodic symmetry allows for identifying free indices and leads to data compression.

This paper explores data compression by automatically identifying symmetries in the unknown generating function, treating the problem as a hidden subgroup problem (HSP).

The HSP in database compression

A concise introduction of quantum HSP algorithms can be found in Supplementary Note C and F. Suppose that the generating function f has a hidden subgroup H, i.e. f(i) = f(j) if and only if i − j ∈ H, with respect to a given group structure G on the set of indices \({\{i\}}_{0}^{{2}^{n}-1}\). The value f may take on a given coset is not deterministic. A coset c0H for c0 ∈ G is defined as the set {c0 + h∣h ∈ H}. Then the hidden subgroup H imposes a hidden pattern in the time series data generated by the function f, which is a redundancy that can be eliminated to achieve data compression. We call this kind of compression hidden subgroup compression, defined as follows,

Definition 1

HSP in database compression. For a given group structure G defined on a set of indices {i} and a function f which hides a subgroup H < G, where < denotes a subgroup, the objective is to compress the database \({{\mathcal{Q}}}_{f}\) storing the function values, i.e., \({{\mathcal{Q}}}_{f}({\bf{i}})=f({\bf{i}})\), removing all duplicated entries by constructing a characteristic function c(i) = 1 if the data at entry i can be overwritten, and c(i) = 0 otherwise. Furthermore, a query function q should be constructed that accurately retrieves f(i) upon query: \({{\mathcal{Q}}}_{f}^{{\prime} }(q({\bf{i}}))=f({\bf{i}})\), for any updated database \({{\mathcal{Q}}}^{{\prime} }\) with data modified on free indices.

For the moment, we assume that the sequence has a hidden subgroup structure with respect to a given group. This is to establish basic concepts and tools later used in the variational version. In the next section (Sec. Compression with respect to indeterminate group structure), we discuss how this assumption can be relaxed to include more types of data symmetry.

For simplicity, we focus on the case where there is a single generator of the hidden sub-group, which encompasses many studied HSP instances24. The methods we use can naturally be extended to the case of several generators, since the HSP algorithm also works for the case of several generators22,25.

The HSP database compression involves identifying the hidden subgroup’s generator using an HSP algorithm. Efficient construction and evaluation of both the characteristic function c and query function q are achievable through this generator. Consider Simon’s problem26 as an illustration: the function f exhibits symmetry, f(i) = f(j) if and only if i = j ⊕ s, where s is an unknown secret bit string. This s acts as the generator for the hidden subgroup 0, s, employing bit-wise addition ⊕ as the group operation. Once s is acquired through the HSP algorithm, constructing the characteristic function c proceeds by

where we say i < j if and only if τ(i) < τ(j). In other words, for any pair of two indices i, j such that f(i) = f(j), we keep the smaller index and set the larger index free. Therefore, we can construct the query function q by querying the smaller index,

This process frees half the database capacity for new data storage. The best classical HSP algorithm, as proven in ref. 26, demands an exponential query count to uncover the secret key s from the database \({\mathcal{Q}}\). Conversely, the quantum HSP algorithm requires only O(n) queries, presenting an exponential acceleration. Consequently, the quantum HSP’s exponential speedup directly enhances database compression.

More generally, the HSP quantum algorithm can be used to solve the HSP database compression. Identifying the generator of the hidden subgroup H and the characteristic function can be constructed as c(i) = 1 if \({\bf{i}}\,{\mathrm{mod}}\,\,H \,<\, {\bf{i}}\) and c(i) = 0 otherwise. The query function q can be constructed as \(q({\bf{i}})={\bf{i}}\,\mathrm{mod}\,\,H\). Conversely, if all the duplicated entries in the database are identified, the characteristic function can be used to find H. Using the bisection method, \(O(\log | G| )\) queries to c( ⋅ ) can identify the largest non-free index if, and if + 1 will be the generator of H, with + being the group operation. This established the equivalence (up to polynomial overhead) between the HSP and the hidden subgroup compression, summarized in the following theorem.

Theorem 1

Exponential speedup in database compression. The query complexity of the database compression is the same as that of the corresponding HSP.

According to the theorem, the exponential speedup of quantum algorithms over their classical counterparts in the Hidden Subgroup Problem (HSP) can be naturally extrapolated to the database compression problem. This is exemplified by period finding27,28 and Simon’s problem26. Note that the query complexity is defined as the number of times a black-box function is invoked, irrespective of the time consumed per call24. For the Abelian HSP, the most efficient known classical algorithm29,30 exhibits a query complexity of \(O(\sqrt{\frac{| G| }{| H| }})\). In some instances, the query complexity is \(\omega \left(\sqrt{\frac{| G| }{| H| }}\right)\)29,30, and specifically, \(\Theta (\sqrt{| G| })\) for Simon’s problem26). Here, O represents the asymptotic upper bound, ω denotes the asymptotic lower bound, and Θ signifies both the asymptotic upper and lower bounds. However, the quantum Abelian HSP algorithm displays a query complexity of \(O(\log | G| )\), which is always polynomial21.

Compression with respect to indeterminate group structure

Searching over group structures

In practice, the time series data generally does not come with a pre-defined group structure that is a priori known. Randomly guessing a group structure can lead to failures when attempting to compress the data, as patterns may not align with hidden subgroups of the group (see Supplementary Note D for an example). The standard quantum algorithm for HSP can only be directly applied when the generating function has an unknown subgroup with respect to a known group. For example, all periodic data sequences with length N have a hidden subgroup structure with respect to \({{\mathbb{Z}}}_{N}\). Without knowing that the group structure is \({{\mathbb{Z}}}_{N}\), the HSP algorithm cannot be applied.

This limitation can be overcome by modifying the hidden subgroup algorithm using variational quantum circuits that adjust themselves based on parameters, allowing for the search for suitable group structures. By exploring different group types and isomorphisms of assigning them, more classes of time series data can be compressed. We formulate the variational hidden subgroup compression as follows,

Definition 2

Variational hidden subgroup compression. Let \({{\mathcal{Q}}}_{f}\) be a database storing time series data {f(0), f(1), …, f(2n − 1)}, generated by the function f. We say \({{\mathcal{Q}}}_{f}\) has a hidden subgroup structure if there exists a group structure \({G}={(\{0,\,1\}^{n},\,*\,)}\) defined on the indices {i} and a subgroup H < G, satisfying \({f}{({\mathbf{i}}\,*\,{\mathbf{h}})}=f{({\mathbf{i}})}\) if and only if h ∈ H. The variational hidden subgroup compression is to compress the time series data by varying the group structures to search for the correct operation \({\,*\,}\) and the hidden subgroup H, using queries on \({{\mathcal{Q}}}_{f}\).

The variational hidden subgroup compression may not have a unique solution. As our goal is data compression, identifying just one solution suffices. For example, consider the time series {0, 1, 2, 3, 0, 1, 2, 3}, which exhibits multiple hidden subgroup structures, like \((\{0,4\},* )\, < \,{{\mathbb{Z}}}_{8}\) and \((\{(0,0,0),(1,0,0)\},* ) \,<\, {{\mathbb{Z}}}_{2}^{3}\). Here \({{\mathbb{Z}}}_{8}\) is the group formed by integers with addition modulo 8, and \({{\mathbb{Z}}}_{2}^{3}\) means \({{\mathbb{Z}}}_{2}\times {{\mathbb{Z}}}_{2}\times {{\mathbb{Z}}}_{2}\).

Next, we present our main results on solving this variational hidden subgroup compression problem using variational quantum circuits, without prior knowledge of the group G. This is achieved by replacing the quantum Fourier transform (QFT, see Supplementary Note C) in a standard HSP circuit with a parameterized circuit, which recovers the QFT over any finite Abelian group G of the form \({{\mathbb{Z}}}_{{2}^{{m}_{1}}}\times {{\mathbb{Z}}}_{{2}^{{m}_{2}}}\times \ldots \times {{\mathbb{Z}}}_{{2}^{{m}_{q}}}\), based on the chosen parameters. We then incorporate this parametrized hidden subgroup algorithm into an autoencoder structure. The autoencoder compresses the data through its bottleneck using the encoder and restores it using the decoder, ensuring reversible compression. During training, an automatic search finds suitable parameters to make the decoder’s output as similar as possible to the input. Once training is complete, the decoder can be removed and the encoder acts as a compressor.

Searching over different types of Abelian groups

We present here a parametrized quantum circuit that is capable of implementing the quantum Fourier transform over any Abelian group of the form \({{\mathbb{Z}}}_{{2}^{{m}_{1}}}\times {{\mathbb{Z}}}_{{2}^{{m}_{2}}}\times \ldots \times {{\mathbb{Z}}}_{{2}^{{m}_{q}}}\), with suitable choices of parameters. We will begin with examples and then present the general architecture. The quantum Fourier transform over a group G is defined as a unitary,

The quantum Fourier transform over a Cartesian product of two groups \({{\mathbb{Z}}}_{{N}_{1}}\times {{\mathbb{Z}}}_{{N}_{2}}\) is the tensor product of the respective quantum Fourier transform24,31, i.e., \({{\rm{QFT}}}_{{{\mathbb{Z}}}_{{N}_{1}}\times {{\mathbb{Z}}}_{{N}_{2}}}={{\rm{QFT}}}_{{{\mathbb{Z}}}_{{N}_{1}}}\otimes {{\rm{QFT}}}_{{{\mathbb{Z}}}_{{N}_{2}}}\).

Let us now find the patterns of the quantum circuits for quantum Fourier transform in order to formulate a parametrised circuit that generalises these transforms. Consider the groups \(G\cong {{\mathbb{Z}}}_{8}\), \({{\mathbb{Z}}}_{2}\times {{\mathbb{Z}}}_{4}\), \({{\mathbb{Z}}}_{4}\times {{\mathbb{Z}}}_{2}\), or \({{\mathbb{Z}}}_{2}^{3}\) (detailed definition of G is in Supplementary Note A). As proved in Supplementary Note C, the quantum circuit for the Fourier transform over \({{\mathbb{Z}}}_{8}\) is

where H is the Hadamard gate, and \({R}_{k}=\left[\begin{array}{cc}1&0\\ 0&{e}^{\frac{2\pi {\rm{i}}}{{2}^{k}}}\end{array}\right]\) is a phase rotation gate. The circuit for quantum Fourier transform over \({{\mathbb{Z}}}_{4}\times {{\mathbb{Z}}}_{2}\) is

Note that we can also have the quantum Fourier transform over \({{\mathbb{Z}}}_{2}\times {{\mathbb{Z}}}_{4}\), which is

Finally, the quantum circuit for the quantum Fourier transform over \({{\mathbb{Z}}}_{2}^{3}\) is

The quantum circuit of the Fourier transform over \({{\mathbb{Z}}}_{4}\times {{\mathbb{Z}}}_{2}\), \({{\mathbb{Z}}}_{2}\times {{\mathbb{Z}}}_{4}\) and \({{\mathbb{Z}}}_{2}^{3}\) can be obtained by shutting down certain controlled phase rotation gates Rk in the QFT circuit of \({{\mathbb{Z}}}_{8}\), followed by some swap operations among the qubits. In fact, three parameters will be sufficient to control the circuit. Denote the parameterized swap operation over all the three qubits as

where \({{\rm{SWAP}}}_{ij}^{\theta }\) is the unitary that swaps qubit i and qubit j when θ = 1, and does nothing when θ = 0. Therefore, the following circuit

can implement the quantum Fourier transform over all considered types of groups by suitable parameters. With θ1 = θ2 = θ3 = 1, it implements the quantum Fourier transform over \({{\mathbb{Z}}}_{8}\); with θ1 = 1, θ2 = θ3 = 0, it implements QFT over \({{\mathbb{Z}}}_{4}\times {{\mathbb{Z}}}_{2}\); with θ1 = θ3 = 0, θ2 = 1, it implements QFT over \({{\mathbb{Z}}}_{2}\times {{\mathbb{Z}}}_{4}\); and finally, with θ1 = θ2 = θ3 = 0, it implements the QFT over \({{\mathbb{Z}}}_{2}^{3}\). For simplicity, in the main result part we use parameter θi to represent the controlling parameter, but in the numerical simulation, θi will be replaced with \({\sin }^{2}({\theta }_{i})\) to limit the value of the switch to be in the range of [0, 1].

Generalizing the above example, we have the following parametrized circuits for QFT.

Definition 3

Parametrized circuits for QFT. The circuit is constructed by first applying the Hadamard gate H to every qubit and then consecutively applying

for k = 1, …, n − 1, where the θi,j’s are the tuning parameters and where \({R}_{m}^{i\to j}\) is the phase rotation operator on the j-th qubit controlled by the i-th qubit and H(k) is the Hadamard gate applied to the k-th qubit. Finally, we apply the parametrized SWAP gates

We will denote these parametrized circuits for quantum Fourier transform over different types of groups as \({{\rm{QFT}}}_{\vec{\theta }}\),

which has \(\frac{n(n-1)}{2}\) parameters. It corresponds to the following quantum circuit

This parameterized quantum circuit \({{\rm{QFT}}}_{\vec{\theta }}\) can implement the quantum Fourier transform over Abelian groups of type \({{\mathbb{Z}}}_{{2}^{{m}_{1}}}\times {{\mathbb{Z}}}_{{2}^{{m}_{2}}}\times \ldots \times {{\mathbb{Z}}}_{{2}^{{m}_{q}}}\).

Theorem 2

Expressivity. The parametrized quantum circuit of n-qubits constructed in Definition 3, can implement the quantum Fourier transform over groups of type \({{\mathbb{Z}}}_{{2}^{{m}_{1}}}\times {{\mathbb{Z}}}_{{2}^{{m}_{2}}}\times \ldots \times {{\mathbb{Z}}}_{{2}^{{m}_{q}}}\) with suitable choices of parameters, where m1, m2, …, mq form an integer partition of n.

To prove the theorem, it is direct to verify that the implementation of the QFT over \({{\mathbb{Z}}}_{{2}^{{m}_{1}}}\times {{\mathbb{Z}}}_{{2}^{{m}_{2}}}\times \ldots \times {{\mathbb{Z}}}_{{2}^{{m}_{q}}}\), for t = 0, 1, …, q − 1 can be achieved with parameters

for k = s(t) + 1, s(t) + 2, …, s(t + 1) − 1, where \(s(t):= \mathop{\sum }\nolimits_{j = 1}^{t}{m}_{j}\) and s(0) ≔ 0, and we set all other parameters zero. In particular, when the parameters θi,j’s are all zeros, \({{\rm{QFT}}}_{\overrightarrow{\theta }}\) performs the QFT over \({{\mathbb{Z}}}_{2}^{n}\) and when the parameters θi,j’s are all ones, it performs the QFT over \({{\mathbb{Z}}}_{{2}^{n}}\).

Searching over bit-permutations

Searching across all possible group types is not enough to solve variational hidden subgroup compression, given the existence of multiple ways to assign the same group type (illustrated in Supplementary Note D). It is necessary to explore diverse isomorphisms for the same group type. An isomorphism identifies each element in \({{\mathbb{Z}}}_{{2}^{{m}_{1}}}\times {{\mathbb{Z}}}_{{2}^{{m}_{2}}}\times \ldots \times {{\mathbb{Z}}}_{{2}^{{m}_{q}}}\) with an element in {i = τ(i)∣i = 0, 1, …, 2n − 1}—bit strings of length n on which the group structure is defined. There are 2n! isomorphisms, making exhaustive search computationally infeasible. Thus, we confine our algorithm to isomorphisms induced by bit-permutations, which rearrange bit-string digits.

For a bit-permutation π ∈ Sn, where Sn is the symmetric group of n elements, acting this on the group \({G}={(\{0,1\}^{n},\,*\,)}\) yields a distinct isomorphic group \({G}_{\pi }=({\{0,1\}}^{n},{* }^{{\prime} })\). This isomorphism π induces a unitary transformation:

Uπ can be implemented using only SWAP gates. Supplementary Note D demonstrates that (n − 1)n/2 parameters controlling SWAP gate activation can parametrize all bit-permutations at the circuit level.

Parameterized quantum circuits for variational HSP

Substituting the standard QFT module in an HSP circuit with the provided parametrized QFT circuits yields the circuit ansatz for the variational HSP, denoted as \({{\rm{HSP}}}_{\vec{\theta }}\), as follows:

Corollary 1

Parameterized quantum circuits for hidden subgroup problems. Upon suitable configuration of the parameters \({\vec{\theta}}\), the following parametrized quantum circuits can solve the HSP over any type of finite Abelian group of the form \({{\mathbb{Z}}}_{{2}^{{m}_{1}}}\times {{\mathbb{Z}}}_{{2}^{{m}_{2}}}\times \ldots \times {{\mathbb{Z}}}_{{2}^{{m}_{q}}}\), that is assigned by bit-permutations,

where \({W}_{\vec{\theta }}\) is the parameterized unitary corresponding to bit-permutations and \({U}_{f}\left\vert i\right\rangle \left\vert 0\right\rangle =\left\vert i\right\rangle \left\vert f(i)\right\rangle\).

Obtaining group structures from parameters

Given valid parameters \({\vec{\theta}}\), if the parametrized quantum circuits execute the quantum Fourier transform on Gσ, the group Gσ can be determined from \({\vec{\theta}}\). This involves two steps: firstly, extracting the group type using parameters in QFT, and secondly, deducing permutations from \({W}_{\vec{\theta }}\) parameters. With the established group structure, group operations between elements can be computed, revealing the hidden subgroup. Remarkably, these computations are achievable using classical algorithms on classical devices.

Hidden subgroup auto-encoder

We now construct an auto-encoder that automatically finds the correct parameters of \({{\rm{HSP}}}_{\vec{\theta}}\), compressing the input data into a description of s and the group structure. We describe the autoencoder algorithm, the compression ratio, numerical experiments and discuss potential applications.

The autoencoder algorithm

Our primary algorithm is outlined below, with comprehensive details available in the Methods section.

We employ the quantum autoencoder design, consisting of an encoder \({\mathcal{E}}\) and a decoder \({\mathcal{D}}\). The quantum autoencoder bottleneck, designed to select specific features, generally transmits quantum states to the decoder. For our problem, we impose a classical bottleneck to ensure the classical output as the compressed data. Remarkably, a classical decoder is sufficient to reconstruct the original data, consistent with the compression being the difficult direction of a one-way function and the decoding the easy direction.

Unlike typical autoencoders characterized by arbitrary node connections, we enforce the distinct structure denoted \({{\rm{HSP}}}_{\vec{\theta }}\) as defined in Eq. (16), to serve as our circuit ansatz. We run \({{\rm{HSP}}}_{\vec{\theta}}\) for multiple times to solve a tentative hidden subgroup H. Then we use classical post-processing to generate a classical message σclassical which describes the hidden subgroup H and the data values f(i) on different cosets ciH. This classical message serves as the compressed data, which is passed to the decoder to reconstruct the data. The classical decoder determines the group structure using the message, and then for each index i, reconstructs \(\hat{f}(i)=f(i\,\mathrm{mod}\,\,H)\), where \(f(i\,\mathrm{mod}\,\,H)\) is the data value on some cosets ciH that can be decoded from the classical message σclassical. To evaluate the variational autoencoder’s performance, a cost function is defined using Euclidean distance between the original data and the reconstructed data,

where \(\hat{f}\) implicitly depends on \({\vec{\theta}}\). For computational efficiency, we estimate \(C({\vec{\theta}})\) using polynomial samples. In the Methods, we extend the binary-valued parameter \({\vec{\theta}}\) to the real-valued parameter \({\vec{\gamma}}\), enabling gradient descent. Minimizing this cost function yields the quantum circuit for hidden subgroup compression.

Numerical demonstrations

We implemented the algorithm via classical simulation. In all examples examined, there is indeed convergence to error-free compression, as shown in Fig. 2. Nevertheless, as with gradient descent optimisation in general, we do not analytically prove that there will be convergence to 0 cost function in all cases.

The solid lines are averages and the coloured areas indicate values within one standard deviation of the mean, as obtained from 10 trainings in each case. The Ansatz of Eq. (16) (with \({W}_{\vec{\theta}}\) being trivial) was used with the parameters initially random for each training. In one case, 2 n = 6 qubits are used and the data has Simon’s symmetry (Eq. (38)). In a second example, 2 n = 8 qubits are used and the data has periodic symmetry. In the third example, 2 n = 16 qubits are used and the data has Simon’s symmetry. The sudden drop at the last step appears when we choose the nearest integer for s. We see that in all cases the cost function of the training data converges to 0. The cost function on test data from the same source is then guaranteed to also be 0 and is therefore not shown.

In Fig. 3, we demonstrate that our quantum algorithm achieves a lower mean squared error on test data than a MATLAB classical autoencoder32. We do not rule out that other classical compression approaches may succeed for small input data sizes, but if a classical approach could work for very large data it would imply a classical method for efficiently solving the hidden subgroup problem, which is less likely.

The performance on test data after training is compared for the quantum case associated with 2 n = 16 qubits, and the classical MATLAB autoencoder32. The autoencoder has a 256-8-256 structure with 256 neurons for input and output and an 8-bit hidden layer. All the test data has the same hidden subgroup. The mean squared error is defined as \(\frac{1}{256}{\sum }_{i\,\in \,{\rm{test}}\, {\rm{data}}}{\left[{f_{in}}(i)-{f_{out}}(i)\right]}^{2}\,\), where fin is the input data (test data) and fout is the output of the autoencoder. We try different initial values to train the classical autoencoder and apply the trained classical autoencoder to the test data to get the mean squared error. The mean squared error standard deviation over different trainings is also shown as a line segment on the top of the bar. The quantum autoencoder achieves negligible error on the test data, unlike the classical autoencoder.

Details of the numerical experiments and links to the codes can be found in the Methods.

Compression ratio of the encoder

Now let us upper bound the size of the compressed data σclassical and the compression ratio. According to our circuit architecture shown in Theorem 2 and Theorem 1, it takes n(n − 1) bits to specify the parameter configuration \({\overrightarrow{\theta}}\). Moreover, n bits are needed to specify the generator of H, and ∣G/H∣m bits are used to store the data values f(c) for each coset c ∈ G/H, where m is the number of bits used to represent f(c). In total, it takes no more than n2 + ∣G/H∣m bits to store the compressed data, while it takes ∣G∣ m bits to store the full sequential data. Since ∣G∣ = 2n, we get a compression ratio

which is smaller than 1 for sufficiently large n or m. For example, let us consider the subset of all balanced binary sequences of length 2n, where the sequence has the same number of 0’s and 1’s, e.g., {0, 0, 1, 1}. Because 0 and 1 are repeated for 2n−1 times, the subgroup H, if it exists, has cardinality 2n−1, which gives us a compression ratio \(\kappa =\frac{{n}^{2}+2}{{2}^{n}}\). For a more detailed discussion about the compression ratio, please refer to Supplementary Note B.

Potential applications to real-world data

Our algorithm is designed to work for input data sequences satisfying the following conditions: (i) The length of the data sequence is 2n for some integer n. (ii) There exists an Abelian group of the type \({{\mathbb{Z}}}_{{2}^{{m}_{1}}}\times {{\mathbb{Z}}}_{{2}^{{m}_{2}}}\times \ldots \times {{\mathbb{Z}}}_{{2}^{{m}_{q}}}\), where m1 + m2 + . . + mq = n and an isomorphism to assign this group structure to the set of indices of the data sequence up to bit-permutations, such that two data point values are the same if and only if their indices are in the same coset. Data sequences satisfying the above three assumptions can in principle be exactly solved by the variational HSP compression.

These strict assumptions can be relaxed to cover data sequences generated in reality that may violate assumptions (ii), if we allow approximate compression. For example, a data sequence of length 8, say, 01010001 that has five 0’s and three 1’s can never have hidden subgroup structure, since the cardinality of the subgroup must be an integer factor of the cardinality of the group. Our variational algorithm in fact allows for getting around this limitation by searching over approximate subgroup structures. When our algorithm converges to a reconstruction error that is not exactly zero but relatively small, then we get an approximate compression of the data sequence. In this way, even if the data does not have an exact group structure, we can approximate it by a sequence that is close to it. For example, 01010111 does not have a hidden subgroup, but 01010101 has and is close to the original sequence.

To this regard, our method can potentially be applied to the compression of pictures (regarded as sequential data), audio, and stock price data, where approximate reconstruction is allowed, as long as the approximation meets the respective requirements. We are presently investigating such applications.

Application to quantum state compression

Our algorithm can be adapted to compress quantum states satisfying translational symmetry. Specifically, consider a set of quantum states \({\mathcal{S}}=\{\left\vert \varphi \right\rangle \,| {T}_{{h}_{0}}\left\vert \varphi \right\rangle =\left\vert \varphi \right\rangle \}\) that is translationally invariant under the action of the operator \({T}_{{h}_{0}}\), defined as

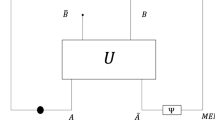

for all computational basis \(\left\vert x\right\rangle\), where \({\,*\,}\) represents the group operation of G assigned to the bit strings x’s. Assume that there is a source that randomly generates \({\left\vert \varphi \right\rangle }^{\otimes n}\) according to a probability density \({\mu }_{\vert \varphi \rangle}\), i.e., n copies of a state \(\left\vert \varphi \right\rangle \in {\mathcal{S}}\) satisfying the translational symmetry. Then our variational HSP algorithm can be applied to compress the quantum states generated by the source, with two modifications. First, we do not need Hadamard gates and Uf, and the variational QFT is applied directly to the quantum state \(\left\vert \varphi \right\rangle\), as shown by the following circuit,

Secondly, the cost function Eq. (17) is replaced by the infidelity between the input state and the reconstructed state. See Supplementary Note E for a more detailed description of this compression algorithm for quantum states.

Quantum thermodynamical advantage implied by the algorithm

Now we discuss the thermodynamic implications of our results. Quantum advantages for thermodynamical tasks are being sought in coherent accurate information processing33, in charging time of batteries34, and in the efficiencies of thermal machines35. Here we argue that the quantum computational advantage of HSP algorithms translates into a thermodynamic advantage in energy harvesting, enabling more work extracted from a source within a fixed amount of time.

Information can fuel energy harvesting together with heat energy; having the knowledge of the system will enable work extraction that is otherwise impossible, e.g. using Szilard engine36,37,38. The free energy of n degenerate 2-level systems is \(F=U-{k}_{B}TS\ln 2={k}_{B}T{\sum }_{i}\,{p}_{i}\ln {p}_{i}\), where T is the temperature of the heat bath, kB is the Boltzmann’s constant, U = 0 is the internal energy, \(S=-{\sum }_{i}\,{p}_{i}\,{\log }_{2}\,{p}_{i}\) is the Shannon entropy and pi is the probability for the system being in energy level i. Transforming the system into the thermal state gives a free energy difference \((n-S){k}_{B}T\ln 2\), which is the amount of work that can be extracted37.

As depicted in Fig. 4, we consider a source that generates pseudo-random spin sequences, where spin up encodes bit 0 and spin down encodes bit 1. Correlations among spins can be exploited to extract work, even if the marginal distributions of each spin are uniformly random37. For example, if two spins are correlated in such a way that they are pointing to either both up or both down, e.g. \(\frac{1}{2}(\left\vert 00\right\rangle \left\langle 00\right\vert +\left\vert 11\right\rangle \left\langle 11\right\vert )\), then we can apply a CNOT operation and transform it to \(\frac{1}{2}(\left\vert 0\right\rangle \left\langle 0\right\vert +\left\vert 1\right\rangle \left\langle 1\right\vert )\otimes \left\vert 0\right\rangle \left\langle 0\right\vert\), and can therefore deterministically extract \({k}_{B}T\ln 2\) work from the second bit. More generally, we can use a unitary transformation to convert non-uniformly distributed long spin sequences into shorter, uniformly-random spin sequences, with a fixed number of spins appended at the end, as shown in Fig. 4.

To demonstrate quantum energy harvesting advantage, consider a competition between classical and quantum intelligent extractors working on a pseudo-random spin source. The classical extractor uses classical neural nets or algorithms, while the quantum counterpart leverages our algorithm on a quantum computer. Specifically, let \({\mathcal{P}}\subset {\{0,1\}}^{n}\) be the set of all the binary strings with length n that have the same hidden subgroup structure H < G for a known G, as specified in the Methods section ''Group structures in databases''. Then for each run of the experiment, the source will, e.g. uniformly randomly, output a sequence in \({\mathcal{P}}\). The goal of intelligent extractors is to maximize the work extraction from this sequence within a reasonable amount of time. The competition is divided into two stages. At the first stage, the intelligent extractors are allowed to access the source for a polynomial amount of time and query and learn the patterns in the sequence generated. In the second stage, within a polynomial amount of time, the extractor will extract work from the source, and the extractor that has the largest average work extraction will win the competition.

We assert that a quantum intelligent extractor outperforms the classical version, effectively turning the quantum computational advantage into an increase in free energy. No polynomial-time classical algorithm is known for compressing this sequence, as that would imply solving the hidden subgroup problem efficiently. However, by exploiting the exponential speedup of quantum HSP algorithms, there is an efficient way to extract the largest amount of work from this pseudo-random source. Through training, our variational algorithm uncovers hidden subgroup structures. After training, we construct a unitary mapping pseudo-random n-spin sequences into those with the first kq spins uniformly random and the last n − kq spins all up, from which Szilard engines can extract \({W}_{q}=(n-{k}_{q}){k}_{B}T\ln 2\) work. The classical extractor, which is unable to reveal the hidden symmetry efficiently, can only transform the sequence to kc ≫ kq spins that are uniformly random, resulting a much smaller work extraction. Thus quantum extraction strategy can extract more work Wc ≪ Wq, demonstrating an advantage in energy harvesting using quantum algorithms.

Discussion

We presented a quantum algorithm for non-linear information compression based on the hidden subgroup problem (HSP), which is subsequently extended to a variational version that can automatically adapt itself to the correct group structure. Our approach employs a versatile quantum circuit ansatz that covers diverse Abelian HSP scenarios. This ansatz allows flexible feature extraction from input data, including period identification, which can be selectively passed through an autoencoder’s bottleneck or discarded.

Leveraging HSP’s exponential advantage over classical counterparts, our method achieves an exponential advantage in query complexity for HSP-symmetric data compression. Our HSP-based compression algorithm demonstrates scalable performance (O(n2) free parameters) and convergence in numerical experiments simulating error-corrected quantum computers. Furthermore, our algorithm enhances energy extraction from pseudo-random sources, effectively allowing the assignment of higher free energy to specific sources.

Our work links the quantum HSP exponential speed-up to data compression and presents a promising new direction for research into quantum autoencoders and the HSP, paving the way for future investigations in the non-Abelian HSP context: the search for further quantum advantages in classical information compression. Further investigations include scrutinizing the presence of HSP symmetries, both exact and approximate, in target compressible data. Experimental implementations and the impact of noise should be considered.

It should be investigated whether recent methods on the analysis of gradient descent with variational circuits can be employed to analytically give guarantees or other insights on the convergence of the gradient descent39,40,41. Finally, we advocate for delving into the non-Abelian scenario, and the algorithm’s potential to distinguish pseudo-random data, generated via modular exponentiation, from genuinely random data.

Methods

Compressing data in a database

Database and logical deletion

Compression optimizes data storage and analysis by removing duplicate data and saving resources in a database. Databases have both physical size (on hardware) and logical size (data stored). To save costs, data is logically deleted and overwritten when new data arrives42,43. Our goal is to create a framework for data compression by logically removing duplicate values in a database.

More formally, let \({\mathcal{Q}}\) be a database that returns a value \({\mathcal{Q}}(i)\) upon query on index i. The data \({\mathcal{Q}}(i)\) is said to be a duplicated value if there exists an index j such that \({\mathcal{Q}}(i)={\mathcal{Q}}(j)\). We want to logically delete the duplicated value \({\mathcal{Q}}(i)\) by labeling the index i as deleted and ready for storing new data. This logical deletion can be accomplished by a characteristic function c that specifies if a position of the database is free for storing new data,

With this characteristic function c, the database \({\mathcal{Q}}\) can be freely modified on the index set F = {i∣c(i) = 1}, without affecting its data integrity, which is referred to as the set of free indices. To retrieve the original data from the database after deletion, we also need a query function q that helps us to retrieve the correct data in the modified database \({{\mathcal{Q}}}^{{\prime} }\),

for any new database state \({{\mathcal{Q}}}^{{\prime} }\) with modifications made on the free indices F.

Under some conditions, a classical database can also be queried in a quantum superposition44. For example, an optical device such as a compact disk storing classical data can be queried by light in a superposition of locations such that data stored at different indices can in principle be queried simultaneously (see Fig. 4 in ref. 44). In this paper, we regard the database \({\mathcal{Q}}\) as an oracle that can be queried by a quantum computer via a unitary that maps \(\left\vert i\right\rangle \left\vert 0\right\rangle\) to \(\left\vert i\right\rangle \left\vert {\mathcal{Q}}(i)\right\rangle\): \({\mathcal{Q}}\) serves as Uf in our circuit Ansatz in Eq. (16). The quantum computer can prepare a superposition state \(\frac{1}{\sqrt{N}}{\sum }_{i}\,\left\vert i\right\rangle \left\vert 0\right\rangle\) to query the database and obtain a superimposed data set \(\frac{1}{\sqrt{N}}{\sum }_{i}\left\vert i\right\rangle \left\vert {\mathcal{Q}}(i)\right\rangle\) as output, where N is the number of indices in the database.

Compression via symmetry

As long as there are symmetries, the data stored in the database can be compressed even if the exact expression of the generating function is not fully recognized. Different levels of knowledge of the generating function will produce different levels of compression ratio. For example, consider the data sequence {1, 4, 9, 16, 25, 16, 9, 4, 1, 4, 9, 16, 25, 16, …} generated by a function f. On the first level, it is obviously periodic, with f(i) = f(i + 8k), for all integer k. Identifying this periodic pattern in the database helps us to reduce its redundancy by only keeping the record of its first period {1, 4, 9, 16, 25, 16, 9, 4}, and marking all other indices free to use by setting c(i) = 1 for all i > 8. On the second level, the numbers have reflection symmetry within one period, i.e. f(i) = f(j) whenever the two indices satisfy i + j = 10. This reflection symmetry helps us to further compress the data to {1, 4, 9, 16, 25}. On the third level, we identify the exact expression of the generating function and the data can be further compressed to the description of the function f(i) = i2 for i = 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, and all the indices in the database can be marked free to use. But even if we do not get the exact expression of the generating function, the periodic structure and the reflection symmetry in the data can be used to compress the data. This type of compression can be achieved by identifying the symmetry in the data.

Introduction to the HSP

The HSP is to identify hidden symmetries in functions. The well-known quantum algorithm to solve this problem has an advantage in query complexity compared with its classical counterparts21. We will show that solving the HSP can be leveraged for data compression, efficiently identifying duplicated data values.

Definition 4

Abelian hidden subgroup problem. Given an Abelian group G and a subgroup H, suppose that a function f : G → {0, 1}m satisfies

We then say that H is a hidden subgroup of f, and f has the symmetry of the hidden subgroup H. The HSP is to find H, given an oracle of f, where the oracle is a black box that returns f(i) upon each query of i.

An example of an HSP is to find the period of a sequence. For example, {1, 4, 9, 16, 25, 1, 4, 9, 16, 25, 1, 4, 9, 16, 25} is a sequence of length 15 which has a period of length 5, because f(i) = f(j) if and only if i − j = 0, 5, or 10. Identifying the correct period is equivalent to identifying the correct hidden subgroup of \({{\mathbb{Z}}}_{15}\), and in this example, the hidden subgroup is \(\{0,5,10\} < {{\mathbb{Z}}}_{15}\).

Group structures in databases

Efficiently assigning group structures to the set of indices

To formulate database compression as an HSP, we need to establish a group structure for the indices in the database. Let us begin with examples and then present the general theory.

For instance, consider indices i = 0, 1, 2, 3, …, 7 represented as bit strings of length 3, e.g., i = 000, 001, 010, …, 111. Different types of group structures can be assigned: \({{\mathbb{Z}}}_{2}\times {{\mathbb{Z}}}_{2}\times {{\mathbb{Z}}}_{2}\), \({{\mathbb{Z}}}_{4}\times {{\mathbb{Z}}}_{2}\), or \({{\mathbb{Z}}}_{8}\).

One approach defines the group operation as bit-wise addition modulo 2, making the group isomorphic to \({{\mathbb{Z}}}_{2}\times {{\mathbb{Z}}}_{2}\times {{\mathbb{Z}}}_{2}\). Alternatively, the group operation can be binary addition modulo 8, resulting in a group isomorphic to \({{\mathbb{Z}}}_{8}\). Another method splits the bit string into two parts and defines the group operation \({\,*\,}\) between two bit strings abc and xyz as

where “Append” is the string operation that appends the second string to the end of the first string. This approach yields a group isomorphic to \({{\mathbb{Z}}}_{4}\times {{\mathbb{Z}}}_{2}\), combining addition modulo 4 for the first part and bit-wise addition ⊕ for the second part.

Further flexibility in assigning group structures comes from isomorphisms induced by permuting bit string digits. For instance, the group structure \({{\mathbb{Z}}}_{4}\) can be assigned to indices (bit strings of length 2) through the one-to-one correspondences (isomorphisms):

where G0 represents the canonical assignment and G1 is obtained by permuting the first and second bits.

More generally, the group structure is established in three steps. Consider assigning a group G isomorphic to \({{\mathbb{Z}}}_{{2}^{{m}_{1}}}\times {{\mathbb{Z}}}_{{2}^{{m}_{2}}}\times \ldots \times {{\mathbb{Z}}}_{{2}^{{m}_{q}}}\), with m1, m2, …, mq forming an integer partition of n such that m1 + m2 + … + mq = n.

-

1.

Index Mapping: Identify index i, as an integer, with its binary representation i = τ−1(i).

-

2.

Bit-Permutation and Partition: Apply a bit-permutation σ on binary digits of i, σ ∈ Sn, and divide the permuted bit string σ(i) into q parts, each of length m1, m2, …, mq. Denote parts as i1i2…iq, with ik as the kth part of σ(i).

-

3.

Group Operation: Define G by specifying its operation \({\,*\,}\). For indices i and j, first compute i1i2…iq and j1j2…jq and then calculate c1c2…cq via

$${{\bf{c}}}_{k}={\tau }^{-1}[\tau ({{\bf{i}}}_{k})+\tau ({{\bf{j}}}_{k})\,\mathrm{mod}\,\,{2}^{{m}_{k}}].$$(26)Define the group operation \({\,*\,}\) between i and j:

$$i* j=\tau ({{\bf{c}}}_{1}{{\bf{c}}}_{2}\ldots {{\bf{c}}}_{q}).$$(27)

Note that σ can be selected from \({S}_{{2}^{n}}\), but a bit-permutation is chosen here due to its simplicity. As permutations of digits in a bit string, bit-permutation is easily implemented with SWAP operations to shuffle digits. While arbitrary permutations require exponential parameters, bit-permutations need only polynomial parameters. For a more detailed discussion on assigning group structures to the index set {i} and the parametrization of bit-permutations, refer to Supplementary Note A.

Quantum autoencoder for hidden subgroup compression

Parameterized quantum autoencoder for finding suitable parameters

We adopt a variational quantum algorithm approach, defining a cost function and employing gradient descent to determine the parameters in \({{\rm{HSP}}}_{\vec{\theta}}\). Specifically, we employ the quantum autoencoder architecture. This comprises an encoder \({\mathcal{E}}\) and a decoder \({\mathcal{D}}\). The quantum autoencoder bottleneck, which selectively retains features, passes quantum states to the decoder. To achieve classical data compression, we ensure a classical bottleneck that guarantees classical compressed data. This assumes a classical connection between the encoder and decoder, and measurement of the bottleneck yields the compressed data. See the illustration below:

Note that the bottleneck may consist of multiple bits. The encoder captures a classical feature from the time series, treated as compressed data. This compressed data is then sent through the bottleneck to the decoder, which can reconstruct the original time series. Considering the exponential speedup of quantum circuits over classical algorithms in detecting hidden subgroups within input bits, it is reasonable to anticipate a similar exponential advantage over classical neural networks for variational hidden subgroup data compression.

Real valued parameters and cost function

An important note is that both the cost function shown in Eq. (17) and parameters are integers, rendering the problem combinatorial and unsuited for direct gradient descent. To address this, we generalize by making both parameters and the cost function real numbers, discussed as follows.

To avoid ambiguity, we use \({\vec{\gamma}}\) to denote the generalized, real-valued parameter configuration, and keep using \({\vec{\theta}}\) to denote the binary valued parameters configuration. When parameters become real, the circuit generally does not implement any quantum Fourier transform. To obtain the group structure, we discretize \({\vec{\gamma}}\) back to \({\vec{\theta}}\).

We randomly generate the configuration \({\vec{\theta}}\) of binary valued parameters according to the parameters γi; specifically, we randomly generate θi ∈ {0, 1} according to the probability distribution

In this way, the probability of getting a specific parameter configuration \({\vec{\theta}}=({b}_{1},{b}_{2},....,{b}_{q})\) is

For each binary configuration \({\vec{\theta}}\) generated in this way, we can then use the classical algorithm to obtain the compressed data. In general, this compressed data cannot exactly reconstruct the original data, at the intermediate step in the training process. This gives us a positive, integer-valued cost \(C({\vec{\theta}})\). Repeating this process many times, we can efficiently obtain the estimation of the average value of the cost function,

This average cost takes real values, and it is amenable to minimization through gradient descent. Minimizing this average cost function we will get the appropriate parameters that solve the HSP.

In the following, we will introduce the detailed structure of the encoder and the decoder, followed by a discussion of how parameters are updated to achieve successful compression.

Encoder structure overview

In contrast to conventional autoencoders with arbitrary node connections and learnable weights, we impose a special structure \({{\rm{HSP}}}_{\vec{\theta}}\) defined in Eq. (16) as the circuit ansatz. This structure leverages quantum circuits’ computational prowess in identifying Abelian hidden subgroups. Then we have a well-organized encoder (and decoder) as described below.

We use a quantum-classical hybrid structure for the encoder, where the quantum part is used to speed up the Fourier transform and the classical part is used to post-process the data sampled from the quantum circuit to calculate the hidden subgroup. The procedure is summarized in Algorithm 1 and explained as follows.

The key idea is to apply the parameterized quantum circuit \({{\rm{HSP}}}_{\vec{\gamma}}\) many times and then use a classical algorithm to find out the hidden subgroup. Specifically, we first apply the parameterized quantum circuits \({{\rm{HSP}}}_{\vec{\gamma}}\) for HSP with real valued parameters \({\vec{\gamma}}\), and obtain a bit string j = j1j2…jn. Repeat this process K times and then we have K such bit strings \({\{{{\bf{j}}}^{(k)}\}}_{k = 1}^{K}\). These bit strings would belong to the orthogonal group H⊥ (see Supplementary Note C for an introduction) if the parameters \({\vec{\gamma}}\) correctly configure the parameterized circuit \({{\rm{HSP}}}_{\vec{\gamma}}\) exactly as the circuit solving the HSP of f, which is not the case as long as \({\vec{\gamma}}\) is not binary numbers.

Then we randomly generate a configuration of binary parameters \({\vec{\theta}}\) according to the probability distribution defined in Eq. (30). This probability distribution does not guarantee that the parameter configuration generated gives a quantum circuit that solves a hidden subgroup. For example, θ3 = 1 while θ1 = 0 in Eq. (9) does not correspond to any quantum Fourier transform. So we need to check the validity of the parameters \({\vec{\theta}}\) generated. For each instance of the parameters, we check if the parameterized circuit \({{\rm{HSP}}}_{\vec{\gamma}}\) corresponds to a quantum circuit that solves the HSP for some certain group G. At the end of the training, we pick the valid QFT closest to the trained circuit. (This procedure is efficient in that there are poly(n) parameters and one decision per parameter).

Algorithm 1

Encoder

If a legitimate parameter configuration \({\vec{\theta}}\) is sampled, we then use the classical algorithm (see Supplementary Note F.3) to solve the corresponding group structure G. With the group structure G specified, we can find out which congruence equations (see Supplementary Note C.2, Eq. (40)) are used to find out the generator s = s1s2 ⋯ sn of the subgroup H. Since the linear congruence equation systems always have solutions, we can always get such a subgroup H < G. However, H is not guaranteed to be the actual hidden subgroup of f at this intermediate step. We have to optimize the parameters to increase the probability of finding the correct hidden subgroup of f. This optimization is carried out by passing the results to the decoder, calculating the average cost function, and then using gradient descent. In fact, the parameter \({\vec{\theta}}\) can be used to describe the group structure. We then encode \({\vec{\theta}}\), the generator of H, and the data points (c, f(c)) for c ∈ G/H into a classical message σclassical; this classical message is regarded as the compressed data.

Pre-training of the encoder

In practical training, we discovered that finding the generator of the hidden subgroup by directly applying Euclid’s algorithm to solve linear congruences (e.g. Eq. (33)) is ineffective. Instead, we employ a pre-training method to make the autoencoder functional. During intermediate training steps, the correct Fourier transformation remains undiscovered, and thus many incorrect bit strings are sampled (all bit strings are possible in general). This results in the congruence equations having only the trivial solution, i.e., all bits being zero. Consequently, the classical post-processing continuously outputs the wrong generator (e.g. the secret key in Simon’s algorithm) of the hidden subgroup as s = 0. With this incorrect generator, the cost function remains large, and gradient descent often fails to improve the situation, leading to a barren plateau phenomenon with the output stuck at s = 0.

To circumvent such barren plateaus, we introduce a pre-training technique to assist the encoder in identifying a non-trivial generator s, although this s is not guaranteed to be the correct hidden subgroup’s generator. The autoencoder training is thus split into two stages. First, the encoder is pre-trained to output a non-trivial s (i.e., s ≠ 0). In the second step, the hidden subgroup’s generator s is sent to the decoder to reconstruct the data sequence and be evaluated by the overall cost function shown in Eq. (17). The autoencoder is then trained as a whole to obtain the correct generator s. During each iteration in the overall training, we apply the pre-training technique described below to ensure the encoder outputs a non-trivial generator s ≠ 0.

To help the encoder output a non-trivial generator s, we incorporate a new parameter set \(\overrightarrow{S}\), where each Si takes values in the interval [0, 1]. The set will be used to calculate the continuous bit string \({\bf{s}}={s}_{{m}_{1}}{s}_{{m}_{2}}\ldots {s}_{{m}_{q}}\), where m1 + m2 + …mq = n, as follows:

By Eq. (32) we will get each continuous \({s}_{{m}_{i}}\), which depends on the corresponding \({{\mathbb{Z}}}_{{2}^{{m}_{i}}}\) groups. To make sure s is valid, we choose the nearest integer for each \({s}_{{m}_{i}}\) in s before feeding it to the decoder.

Now we train both \({\vec{\theta}}\) and \({\vec{S}}\) to find a non-trivial generator s. Take Simons’ problem as an example. Here m1 = m2 = ⋯ = mq = 1, and q = n, so we will write \({s}_{{m}_{i}}\) as si in Simon’s problem for simplicity (see Supplementary Note C.2 for a detailed introduction to Simon’s algorithm). Suppose that the k-th sampled bit string after applying the intermediate HSP algorithm \({{\rm{HSP}}}_{\overrightarrow{\theta }}\) is j(k), then we have the following linear congruence relations to solve for the generator s (proof in Supplementary Note C.2),

When s is not a solution to the linear congruence system, we can use CL(s) to quantify the discrepancy and therefore the cost,

Denoting the probability distribution of output bit string j = j1 j2…jn as P(j), we define a cost function CE for the pretraining of the encoder,

where \(C({\vec{S}})={\sum}_{i}{\sin }^{2}(\pi {S}_{i})\) is a penalty term introduced to push each Si takes value 0 or 1. Minimizing this pretraining cost function CE we can get a non-trivial generator s. When the cost value CE reaches 0, it means we find a plausible generator s, and then it is sent to the decoder for further processing and training.

Algorithm 2

Decoder

Input: Classical message σclassical as a description of the hidden subgroup H and the data values f(i) on different cosets.

Output: A reconstructed data sequence \(\{\hat{f}(0),\hat{f}(1),\ldots ,\hat{f}({2}^{n}-1)\}\).

1 Define an empty list l.;

2 Decode from σclassical the binary valued parameter \({\vec{\theta}}\), the generator

of the hidden subgroup H, and the ordered data pair (c, f(c)) for

c ∈ G/H.;

3 Calculate the group structure from the parameter \({\vec{\theta}}\), obtaining the

group operation \({\,*\,}\).;

4 For each hidden subgroup element h ∈ H and each representative

c ∈ G/H of the cosets, store the value f(c) in the position of

\(\tau{({{\mathbf{c}}\,*\,{\mathbf{h}}})}\) of the list l.;

5 Output \(l=\{\hat{f}(0),\hat{f}(1),\ldots ,\hat{f}({2}^{n}-1)\}\).

Detailed structure of the decoder

The encoder outputs a description of the subgroup H, the group structure G and the values (c, f(c)) for the quotient group c ∈ G/H. Using this information, the decoder can reconstruct the original time series by, i) creating a list of length N, and ii) for each h ∈ H and each c ∈ G/H, store the value f(c) into the position \(\tau({\mathbf{c}\,*\,{\mathbf{h}}})\) of the list, where \({\,*\,}\) is the group operation of G that is obtained from the compressed data. A more efficient decoder does not generate the full-time series but it outputs f(i) upon a query on i.

Full structure of the autoencoder and the description of the training process

Now, we can combine the encoder and the decoder to make an autoencoder that automatically finds the hidden subgroup. Given a parameter configuration \({\vec{\gamma}}\), we run the encoder once and then pass its output to the decoder to get the reconstructed data. Repeat T = O(n) times and calculate the average cost \({{\mathbb{E}}}_{\vec{\gamma}}C\). Then we slightly change the γi to \({\gamma }_{i}^{{\prime} }\) and calculate the updated average cost \({{\mathbb{E}}}_{{\vec{\gamma}}^{{\prime} }}C\). Then the partial derivative of the average cost function can be estimated by \(\frac{\partial \,{{\mathbb{E}}}_{\vec{\gamma}}C}{\partial \,{\gamma}_{i}}\approx \frac{{{\mathbb{E}}}_{{\vec{\gamma}}^{{\prime}}}C-{{\mathbb{E}}}_{\vec{\gamma}}C}{{\gamma }_{i}^{{\prime} }-{\gamma }_{i}}\,.\) Consecutively change the value of γi and we can calculate the gradient \(\nabla{{\mathbb{E}}}_{\vec{\gamma}}C=({\partial}_{{\gamma}_{1}}\,{{\mathbb{E}}}_{\vec{\gamma}}C,\ldots ,{\partial }_{{\gamma }_{q}}\,{{\mathbb{E}}}_{\vec{\gamma}}C)\). If the gradient is smaller than a certain predefined threshold, then the parameter \({\vec{\gamma}}\) is good enough for the hidden subgroup compression. We just output the classical message from the encoder σclassical and the problem is solved. Otherwise, we need to update the parameters, \({\vec{\gamma}}\leftarrow {\vec{\gamma}}-\beta \,\nabla \,{{\mathbb{E}}}_{\vec{\gamma}}C\,,\) where β is the learning rate and a ← b means assigning the value b to the variable a.

In the more sophisticated scaled conjugate gradient (SCG) algorithm32, which is adopted e.g. by MATLAB, the step-size is a function of quadratic approximation of the cost function. Taking the classical autoencoder cost function \({C}_{ca}({\vec{\theta}})\) as an example, at the kth iteration \({C}_{ca}({\vec{\theta}}_{k})\), the next point \({\vec{\theta}}_{k+1}\) is determined as:

To calculate this, SCG defines a middle point \({{\vec{\theta }}_{t,k}}\) between \({{\vec{\theta}}_{k}}\) and \({{\vec{\theta}}_{k+1}}\): \({{\vec{\theta}}_{t,k}}={{\vec{\theta}}_{k}}+{\sigma }_{k}{{\vec{d}}_{k}},\) where 0 < σk ≤ 1 is the step-size and \({{\vec{d}}_{k}}\) is the conjugate direction of the k-th parameter. Thus, the second-order information is computed by using the following first-order information and the conjugate directions:

with \({\alpha}_{k}=-{{{\vec{d}}_{k}}^{\!T}}{C}_{ac}^{{\prime} }({{\vec{\theta }}_{k}})/{{{\vec{d}}_{k}}}^{\!T}{s}_{k}\), where sk denotes the second-order information. Then the next point can be calculated as \({{\vec{\theta}}_{k+1}}={{\vec{\theta }}_{k}}+{\alpha}_{k}\,{{\vec{d}}_{k}}\)

The above procedure as a whole is summarized in Algorithm 3 and is numerically tested in the Methods section ''Numerical experiments''. An important observation is that this algorithm not only compresses the data; as a by-product, it also solves the hidden subgroup of the generating function f without a priori knowledge of the group structure G. In this sense, Algorithm 3 is also a variational quantum algorithm solving the variational HSP.

Algorithm 3

Training of autoencoder

Numerical experiments

In this section, we will numerically check how our quantum algorithm performs by using a classical computer to simulate it. First, we will describe how we generate the training data: data strings with a certain symmetry and corresponding group structures. In line with Eq. (23), for the numerical implementation, we can generate the simplest data series based on f(i) = f(j) if and only if i = j + s, where s is the secret bit string which is a member of a hidden subgroup and “ + ” is the group addition specified by the group structure. In particular, we shall feed our algorithm data that either: (i) is periodic, with a hidden subgroup of \({{\mathbb{Z}}}_{8}\), (ii) satisfies Simon’s symmetry, with a hidden subgroup of \({{\mathbb{Z}}}_{2}\times {{\mathbb{Z}}}_{2}\times {{\mathbb{Z}}}_{2}\), or (iii) has the symmetry of a hidden subgroup of \({{\mathbb{Z}}}_{2}\times {{\mathbb{Z}}}_{4}\).

As an example, we now describe the generating process in the 6 qubits case, where 3 qubits are used as data registers and 3 qubits are used as ancillas. Then the length of the data sequence is 23 = 8. Taking Simon’s problem as an example, the data series set could be

where each row is a time series that we could choose to compress. The (i, j)-th entry of the table is fi(j). The rows are sorted by the value of s. For example, in the first row, the symmetry is the repeating of data in the sense that f1(1) = f1(2), f1(3) = f1(4), f1(5) = f1(6), f1(7) = f1(8). In terms of bits, f1(000) = f1(000 + 001), f1(010) = f1(010 + 001), f1(100) = f1(100 + 001), f1(110) = f1(110 + 001), where “ + ” denotes bit-wise addition modulo 2 and is usually denoted as “⊕”. s is the generator of a hidden subgroup of \({{\mathbb{Z}}}_{2}\times {{\mathbb{Z}}}_{2}\times {{\mathbb{Z}}}_{2}\). Other rows have the same type of symmetry generated by bit-wise addition, except s is different. There are multiple possible data sequences that have the same hidden subgroup symmetry; in this example, 4! = 24 distinct sequences exist, as there are 4! distinct sequences within one “period”, e.g. {0, 1, 2, 3}, {0, 1, 3, 2}, {0, 3, 2, 1}… . We can randomly choose 19 types of data series to train the circuit and 5 types of data series to test the circuit. In the simulations undertaken here testing the performance on the test data was perfect, since the circuit converged to the correct HSP circuit.

Following the above approach, we can generate other matrices of training data according to different group structures and secret bit strings.

We show in Figs. 3 and 2 how our Algorithm 1 combined with Algorithm 2 perform in terms of compressing the data thus generated, for 2n = 6, 2n = 8 and 2n = 16 qubit quantum circuits. Figure 2 demonstrates the convergence of our algorithm when compressing data sequences that either possess Simon’s symmetry (with respect to group \({{\mathbb{Z}}}_{2}\times {{\mathbb{Z}}}_{2}\times {{\mathbb{Z}}}_{2}\)) or periodic symmetry (with respect to group \({{\mathbb{Z}}}_{8}\)). In either case, the training successfully converges to the corresponding group structure, sending the expected number through the bottleneck, namely, the secret key s for Simons’ problem or the period r for the periodic symmetry case. Before sending the data to the decoder, we round s to be composed of integers, which for the 2n = 16 case leads to a small sudden drop in the cost function at the end of the training. In the case of Simon’s symmetry, Fig. 3 illustrates an accuracy advantage compared to the classical autoencoder. To compress classical data series, we build a fully connected classical autoencoder with a 256-8-256 structure, with 256 neurons for input and output, and an 8-bit hidden layer due to s having 8 bits. The training was executed on the MATLAB platform with the built-in scaled conjugate gradient training algorithm32. To enable a comparison with the quantum approach, the training data and test data for the classical autoencoder are also chosen from the 128! distinct sequences but in the form of classical bits. Thus, in this numerical experiment, the quantum approach effectively compresses the time series, while the classical counterpart results in a higher mean squared error on test data.

Compressing quantum states via finding symmetry

We present here a preliminary method to apply our variational QFT ansatz to compress quantum states satisfying a certain type of symmetry. We present first the non-variational version of quantum state compression and then present the variational version. See Supplementary Note E for a more pedagogical discussion.

Non-variational quantum states compressions

Consider n-qubit quantum states \(\left\vert \varphi \right\rangle\), which lives in an N = 2n dimensional Hilbert space, with basis \({\{\left\vert x\right\rangle \}}_{x = 0}^{N-1}\). We can define a translational operator \({T}_{{h}_{0}}\), such that

where + is the group operation of \({{\mathbb{Z}}}_{N}\), i.e., addition modulo N, and h0 = 2m for some integer m such that h0 is a factor of N. Thus the group generated by h0, denoted by H = {0, h0, 2h0, …, (2n−m − 1)h0} is not the whole group \({{\mathbb{Z}}}_{N}\). Define the coset state as

for c ∈ C = {0, 1, 2, …, 2m − 1} being the representative of each coset. It is direct to verify

for all c ∈ C. These coset states form an orthonormal basis for the invariant subspace of this translation operator \({T}_{{h}_{0}}\), whose dimension is \(\frac{| G| }{| H| }={2}^{n-m}\). This suggest that an n-qubit quantum state invariant under \({T}_{{h}_{0}}\) can be compressed to an (n − m)-qubit quantum state.

The quantum state compression problem can be formulated as follows. A source will randomly generate an n-qubit quantum state \(\left\vert \varphi \right\rangle \in {\mathcal{S}}=\{\left\vert \phi \right\rangle | {T}_{{h}_{0}}\left\vert \phi \right\rangle =\left\vert \phi \right\rangle \}\) with probability density \({\mu }_{\left\vert \varphi \right\rangle }\), when we access it. We know that \({T}_{{h}_{0}}\) will act on the state according to the group addition of \({{\mathbb{Z}}}_{N}\) but we do not know the value of h0. The goal is to compress the n-qubit states by identifying their symmetry, given accesses to the quantum sates sampled from the source.

For this non-variational quantum state compression, the group structure is given as an input to the algorithm and therefore we can directly apply the HSP algorithm over the group \({{\mathbb{Z}}}_{N}\) to solve for h0. When h0 is identified, the compression operation can be constructed.

Specifically, suppose that the source generates a state \({\sum }_{c}{\alpha }_{c}\left\vert c+H\right\rangle\) each time; but the state generated may vary from time to time. Then we can use four steps to solve for h0 and therefore construct the compression protocol. (i) Apply \({{\rm{QFT}}}_{{{\mathbb{Z}}}_{N}}\) to the state and then measure in computational basis to get a bit string j. (ii) Repeat the first step for many times to get many bit strings j that satisfies j = k h0 for some integer k. In Supplementary Note E we prove that j’s are sampled from the orthogonal group of H. (iii) Solve the smallest common divisor among the sampled j’s and you get h0. (iv) Construct the following CPTP map that will compress the state generated by the source,

where \(\left\vert {c}_{i}\right\rangle\)’s are basis vectors of a Hilbert space of dimension ∣C∣ = 2n−m and \(\left\vert {\hat{c}}_{i}\right\rangle := \left\vert {c}_{i}+H\right\rangle\)’s are vectors of the Hilbert space of dimension 2n. The following CPTP map \({\mathcal{D}}\) will reconstruct the state,

Variational quantum state compression

Mathematically, we can formulate the following quantum state compression problem where our variational algorithm can be used to compress it. Define the generalized translational operator as

where \({\,*\,}\) is the group operation in the unknown Abelian group G. A source will randomly generate quantum state \({\left\vert \varphi \right\rangle }^{\otimes n}\in {\mathcal{S}}\) (multiple copies are used for evaluating the cost in training, see Supplementary Note E for more explanations) according to a probability density \({\mu }_{\left\vert \psi \right\rangle }\), where the state \(\left\vert \varphi \right\rangle\) is promised to be translational invariant under the action of \({T}_{{h}_{0}}\). Given access to the quantum states generated from this random source but without knowledge of the Abelian group structure G and the hidden subgroup H, the goal is to design \({\mathcal{E}}\) and \({\mathcal{D}}\) that compress and decompress the quantum states.

Then our variational HSP algorithm can be applied, with a slight modification in the cost function. Instead of reconstruction error of classical bit strings, our new optimization goal is to minimize the average infidelity between the input state to the reconstructed state,

The variational algorithm for this quantum states compression problem takes 5 steps. We list the sketch of the protocol here. (i) First, apply the variational QFT ansatz to the one copy of the random state \(\left\vert \varphi \right\rangle\). (ii) Measure the state after the parametrized QFT in the computational basis to get a bit string j. Repeat and get a set of bit strings j. (iii) Use steps 3,4,5 of Algorithm 1 in the main text to solve for a tentative generator h0 of the hidden subgroup. (iv) Use h0 to construct the hidden subgroup H and then use Eq. (42) and Eq. (43) to construct the encoding map \({\mathcal{E}}\) and the decoding map \({\mathcal{D}}\). (v) Evaluate the infidelity between the input state \(\left\vert \varphi \right\rangle \left\langle \varphi \right\vert\) and the reconstructed state \({\mathcal{D}}\,{\circ} \,{\mathcal{E}}(\left\vert \varphi \right\rangle \left\langle \varphi \right\vert )\). (vi) Finally, use gradient descent to update the parameters in the QFT ansatz to minimize the the infidelity cost Eq. (45).

Data availability

The source code and dataset can be found on Github https://github.com/unknownfy/parameterized-Abelian-hidden-subgroup-algorithm.

References

Goldberg, A. V. & Sipser, M. Compression and ranking. SIAM J. Comput. 20, 524–536 (1991).

Ackley, D. H., Hinton, G. E. & Sejnowski, T. J. A learning algorithm for Boltzmann machines. Cogn. Sci. 9, 147–169 (1985).

Kingma, D. P. & Welling, M. An introduction to variational autoencoders. Found. Trends Mach. Learn. 12, 307–392 (2019).

Liou, C. Y., Huang, J. C. & Yang, W. C. Modeling word perception using the Elman network. Neurocomputing 71, 3150–3157 (2008).

Liou, Cheng-Yuan, Cheng, Wei-Chen, Liou, Jiun-Wei & Liou, Daw-Ran Autoencoder for words. Neurocomputing 139, 84–96 (2014).

Biamonte, J. et al. Quantum machine learning. Nature 549, 195–202 (2017).

Wan, K. H., Dahlsten, O., Kristjánsson, H., Gardner, R. & Kim, M. S. Quantum generalisation of feedforward neural networks. Npj Quantum Inf. 3, 1–8 (2017).

Romero, J., Olson, J. P. & Aspuru-Guzik, A. Quantum autoencoders for efficient compression of quantum data. Quantum Sci. Technol. 2, 045001 (2017).

Bravo-Prieto, C. Quantum autoencoders with enhanced data encoding. Mach. Learn.: Sci. Technol. 2, 035028 (2021).

Cao, C. & Wang, X. Noise-assisted quantum autoencoder. Phys. Rev. Appl. 15, 054012 (2021).

Bondarenko, D. & Feldmann, P. Quantum autoencoders to denoise quantum data. Phys. Rev. Lett. 124, 130502 (2020).

Zhou, F. et al. Preserving entanglement in a solid-spin system using quantum autoencoders. Appl. Phys. Lett. 121, 134001 (2022).

Huang, Chang-Jiang et al. Realization of a quantum autoencoder for lossless compression of quantum data. Phys. Rev. A 102, 032412 (2020).

Zhang, H. et al. Resource-efficient high-dimensional subspace teleportation with a quantum autoencoder. Sci. Adv. 8, eabn9783 (2022).

Ding, Y., Lamata, L., Sanz, M., Chen, X. & Solano, E. Experimental implementation of a quantum autoencoder via quantum adders. Adv. Quantum Technol. 2, 1800065 (2019).

Pepper, A., Tischler, N. & Pryde, G. J. Experimental realization of a quantum autoencoder: The compression of qutrits via machine learning. Phys. Rev. Lett. 122, 060501 (2019).

Kaplan, M., Leurent, Gaëtan Leverrier, A. & Naya-Plasencia, M. Breaking symmetric cryptosystems using quantum period finding. In Advances in Cryptology–CRYPTO 2016: 36th Annual International Cryptology Conference, Santa Barbara, CA, USA, August 14-18, 2016, Proceedings, Part II 36, pages 207–237. Springer, (2016).

Wang, S. P. & Sakk, E. Quantum algorithms: overviews, foundations, and speedups. In 2021 IEEE 5th international conference on cryptography, security and privacy (CSP), pages 17–21. IEEE, (2021).

Ben-David, S. et al. Symmetries, graph properties, and quantum speedups. In 2020 IEEE 61st Annual Symposium on Foundations of Computer Science (FOCS), pages 649–660. IEEE, (2020).

Kitaev, A. Y. Quantum measurements and the Abelian stabilizer problem. Preprint at https://arxiv.org/abs/quant-ph/9511026 (1995).

Ettinger, M., Høyer, P. & Knill, E. The quantum query complexity of the hidden subgroup problem is polynomial. Inf. Process. Lett. 91, 43–48 (2004).

Lomont, C. The hidden subgroup problem-review and open problems. Preprint at https://arxiv.org/abs/quant-ph/0411037 (2004).

Jozsa, R. Quantum factoring, discrete logarithms, and the hidden subgroup problem. Comput. Sci. Eng. 3, 34–43 (2001).

Nielsen, M. A. & Chuang, I. Quantum computation and quantum information, (2000).

Ettinger, M. & Høyer, P. On quantum algorithms for noncommutative hidden subgroups. Adv. Appl. Math. 25, 239–251 (2000).

Simon, D. R. On the power of quantum computation. SIAM J. Comput. 26, 1474–1483 (1997).

Shor, P. W. Algorithms for quantum computation: discrete logarithms and factoring. In Proceedings 35th Annual Symposium on Foundations of Computer Science, pages 124–134 (IEEE, 1994).

Shor, P. W. Polynomial-time algorithms for prime factorization and discrete logarithms on a quantum computer. SIAM Rev. 41, 303–332 (1999).

Nayak, A. Deterministic algorithms for the hidden subgroup problem. Quant. Info. Comput. 22, 755–769 (2022).

Ye, Z. & Li, L. Deterministic algorithms for the hidden subgroup problem. Inf. Comput. 289, 104975 (2022).

Moore, C., Rockmore, D. & Russell, A. Generic quantum Fourier transforms. ACM Trans. Algorithms 2, 707–723 (2006).

Møller, M. F. A scaled conjugate gradient algorithm for fast supervised learning. Neural Netw. 6, 525–533 (1993).

Chiribella, G., Meng, F., Renner, R. & Yung, Man-Hong The nonequilibrium cost of accurate information processing. Nat. Commun. 13, 7155 (2022).

Campaioli, F. et al. Enhancing the charging power of quantum batteries. Phys. Rev. Lett. 118, 150601 (2017).

Hammam, K., Leitch, H., Hassouni, Y. & De Chiara, G. Exploiting coherence for quantum thermodynamic advantage. New J. Phys. 24, 113053 (2022).

Szilard, L. On the decrease of entropy in a thermodynamic system by the intervention of intelligent beings. Behav. Sci. 9, 301–310 (1964).