Abstract

Modeling the electrical response of multi-level quantum systems at finite frequency has been typically performed in the context of two incomplete paradigms: (i) input-output theory, which is valid at any frequency but neglects dynamic losses, and (ii) semiclassical theory, which captures dynamic dissipation effects well but is only accurate at low frequencies. Here, we develop a unifying theory, valid for arbitrary frequencies, that captures both the small-signal quantum behavior and the non-unitary effects introduced by relaxation and dephasing. The theory allows a multi-level system to be described by a universal small-signal equivalent-circuit model, a resonant RLC circuit, whose topology only depends on the number of energy levels. We apply our model to a double-quantum-dot charge qubit and a Majorana qubit, showing the capability to continuously describe the systems from adiabatic to resonant and from coherent to incoherent, suggesting new and realistic experiments for improved quantum state readout. Our model will facilitate the design of hybrid quantum–classical circuits and the simulation of qubit control and quantum state readout.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

An accurate model of the electrical response of a quantum system is of paramount importance, particularly when engineering its manipulation and state readout within a larger classical circuit. When an electrical signal perturbs the quantum dynamics of a mesoscopic quantum system, charge redistribution events will manifest as a (gate) current, which will propagate back into the classical world, where it will be measured1,2,3,4,5,6,7. This signal carries information about the dynamical properties of the system, which can be leveraged for characterization, tuning, and in-situ readout of quantum information8,9,10,11,12.

Much has been studied about the electrical response of mesoscopic capacitors and resistors13,14,15,16,17,18. However, a complete theoretical framework is still lacking in the quantum limit where the unitary dynamics of discrete levels and decoherence, caused by coupling to the environment, appear as dispersive and dissipative interactions to a connected classical circuit10,19,19,20,21,22. Thus far, modeling of such phenomena has been approached via two methods: (i) semiclassically, extending to quantum systems the treatment of classical high-frequency electronics23,24, and (ii) with Input-Output theory, adapting quantum electrodynamics (QED) methods to mesoscopic quantum devices operating in the radio-frequency (rf) or microwave range25,26,27,28. Both, however, only capture part of the picture, with the semiclassical models neglecting the complexity of the unitary dynamics beyond the adiabatic regime29,30, and input-output theory lacking a complete description of dynamical dissipation processes.

In this work, we present a Lindblad perturbation formalism that bridges the gap between the two theories, and provides the missing pieces for a more comprehensive modeling of a quantum device at high frequency, including dynamic decoherence processes. Although the formalism will be of interest to many communities such as superconducting charge31,32, semiconductor3,4,33,34,35,36 and Majorana qubits5,37,38,39, here we adopt the language typical of quantum-dot (QD) systems11,23,24. We will consider a quantum system in equilibrium excited by a (small) perturbation of the control voltages, and explore the link between its electrical response and susceptibility, arising from the input-output formalism25,26. The perturbation originates from an rf excitation of one of the gate voltages, \({V}_{{\rm{G}}}(t)=\delta V\cos \omega t\), and we work out its impact on the QD dynamics as well as the gate current it originates.

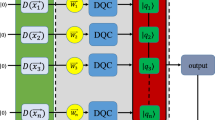

If the rf probe is taken to be small, the response of the system is linear, and thus the gate current oscillates at the same frequency ω as the probe, allowing us to reframe the problem in terms of small-signal electrical analysis. We find that, within the secular approximation, there exists a universal small-signal model of the system in terms of linear circuit elements, which consists of repeated fundamental units in parallel, one for each pair of levels (see Fig. 1). Thus, the circuit topology only depends on the number of levels described in the Hamiltonian, while the dynamical properties of the system only alter the values of the components.

Circuit elements are color-coded according to the description they originate from: input-output (blue) or semiclassical (red). Moreover, in this work we introduce a third branch (black), arising from a consistent quantum description of (detuning-dependent) dynamical decoherence. Notably, the input-output and semiclassical models overlap only in the description of the quantum capacitance (upper left).

In Fig. 1 we color-code the circuit elements according to the description they historically originate from: input-output (blue) or semiclassical (red). Moreover, a consistent description that includes both (detuning-dependent) decoherence and unitary evolution necessarily gives rise to a third set (black), which is introduced in this work and is dominant in the limit of very high decoherence. Notably, we show how the input-output and semiclassical models can be pictured to overlap in the description of the quantum capacitance, which, as we shall see, is the adiabatic limit of the isolated quantum system. However, we shall also describe how the introduction of our novel term allows us to cast a new light on quantum capacitance, which can be seen additionally as the response of the system when all coherent processes are suppressed.

Our description of the response of the quantum circuit as linear circuit elements has the key benefit of enabling the inclusion of small-signal coherent quantum behavior in simple electronic circuit models. Moreover, we only make use of frequency-independent voltage-dependent components, obviating the need for complex and slow Fourier-based nonlinear circuit analysis24.

This work is structured as follows: Firstly, we develop the formalism that leads to the universal small-signal model, starting from the simplicity of an isolated quantum system and later enhancing the model including decoherence in a Lindblad formalism. Consequently, we apply our model to two example systems: a double quantum dot (DQD) charge qubit11,23,24 and a QD coupled to topological Majorana modes5,37,38,39. We discuss our result in the context of the aforementioned paradigms present in the literature, demonstrating how our model continuously transitions between them in their respective regimes of validity. Moreover, we employ our formalism to suggest realistic experiments and potentially enhance current measurements.

Results

Universal small-signal model of a driven quantum system

In this section, we describe the theoretical basis of our formalism, relating the electrical response of a perturbed quantum system to its (charge) susceptibility.

The first necessary step is to describe the driven system quantum-mechanically, and thus define the gate current in terms of a quantum observable. For simplicity and ease of notation, we consider the case of a single gate driving the system (see SM I), but allow for an arbitrary number of energy levels (i.e., of orbital, valley or spin origin). The perturbation of the control voltages is related to the energy detuning of the system via a dimensionless parameter α (the gate lever arm). Thus, in terms of energy detuning, \(\varepsilon (t)={\varepsilon }_{0}+\delta \varepsilon \cos \omega t\), where the detuning oscillation amplitude reads δε = αeδV11.

To the quantum system, (perturbed) gate voltages appear as a time-dependent Hamiltonian of the form

where H0 is the unperturbed Hamiltonian, and \(\Pi =\frac{d}{d\varepsilon }{H}_{0}={\left(\alpha e\right)}^{-1}\frac{d}{d{V}_{{\rm{G}}}}{H}_{0}\) is the dipole operator that couples the quantum system to the gate, which can be understood physically by noting that, in our definition, \(| \left\langle \psi | \Pi | \psi \right\rangle {| }^{2}\) determines how much each level \(\left\vert \psi \right\rangle\) is capacitively coupled to the gate. Using this physical intuition, we can write the gate current as

where \(\alpha e\left\langle \Pi (t)\right\rangle\) is the expectation value of the (time-dependent) polarization charge at the gate. Notably, we stress that the operator Π describes both the perturbation of the QD detuning and collects the back-action on the gate, as one would expect since they originate from the same capacitive coupling.

Since the response of the system is linear, one can consider the electrical response of the QD system in terms of a small-signal admittance, defined as

If the rf perturbation is slow enough to be considered adiabatic, and one neglects decoherence and thermal redistribution of probability, it can be shown that the system’s admittance reads (Methods)11,23,24

where Em are the eigenenergies of the system (given by \({H}_{0}\vert {\phi }_{m}\rangle ={E}_{m}\vert {\phi }_{m}\rangle\)) and pm are the relative state occupation (see Methods). The term CQ is commonly known as the quantum capacitance of the quantum system23,24,40. In the most general case, however, the perturbation may mix the eigenstates and cause the charge movement to lag behind the excitation. Thus, most generally, the system’s response must be written in terms of a complex admittance Y(ω)11,23,24. The real part represents resistive effects, and thus energy dissipation caused by the interaction of the QD with the environment, while the imaginary part, other than the quantum capacitance, originates from the redistribution of probability, either thermally or because of diabatic transitions, hence the name tunneling capacitance in the literature23. From a quantum dynamics perspective, this can be seen by the contribution of the accumulated geometrical and dynamical phase, which in open systems may contain an imaginary part arising from dissipation41,42,43.

Isolated quantum system

We now consider the case of the isolated quantum system, the evolution of which is perfectly unitary. When unperturbed, its evolution is described by the Von Neumann equation as \(\frac{d}{dt}\rho =-i\left[{H}_{0},\rho \right]\), where we have introduced the density matrix ρ to describe the system, and take ℏ = 1. If the system is in the steady state with ρ ≡ ρss, i.e., \(\left[{H}_{0},{\rho }_{{\rm{ss}}}\right]=0\), we can obtain the gate current caused by the perturbation via the Kubo formula41.

If the response is linear, this can be expressed as

where the quantity

represents the susceptibility of the (time-independent) system25,26, and Π(t, τ) is the operator in interaction picture. In the small-signal regime, the susceptibility is not a function of t and τ separately, but only of the time difference t − τ. Therefore, it is best considered in reciprocal space by taking its Fourier transform χ(ω)26. We can now use the causality requirement of Eq. (6), and thus the well-known result that χ(− ω) = χ(ω)*, to write the electrical response as

This property follows from the fact that the operator determining the gate current is the same as the operator that determines the perturbation. Thus Eq. (5) is a consequence of the interaction between the classical circuit and the quantum system. For a unitary evolution and within the rotating-wave approximation (see Methods), the susceptibility takes the well-known form26

Firstly, χ(ω) is purely real, and thus the system’s response is purely reactive. To compare this result with Eq. (4), it is interesting to take the adiabatic limit of Eq. (9).

For most physical systems, such as QD arrays in the constant-interaction approximation44, the dipole operator is constant with respect to gate voltages (i.e., \(\frac{{d}^{2}}{d{\varepsilon }^{2}}{H}_{0}=0\)). We shall make this assumption throughout this work. Making use of this and the Hellman-Feynman theorem40, we find

which leads to the expected result

It is interesting to note that if the linearity with gate voltages is broken (\(\frac{{d}^{2}}{d{\varepsilon }^{2}}{H}_{0}\,\ne\, 0\)), Eq. (10) no longer holds, and the adiabatic limit of the quantum capacitance no longer coincides with the second derivative of the eigenenergies40,45.

Equation (9), moreover, shows how, even for an isolated quantum system, the finite-frequency response cannot simply be modeled by the quantum capacitance CQ. Unlike in a simple capacitor, the susceptibility diverges exactly at resonance, as one would expect from general theory26. This behavior can be better understood if we notice that every pair of levels is summed over twice in Eq. (9). The hermiticity of Π allows us, thanks to Foster’s theorem46,47,48, to synthesize the admittance of the system in the much more insightful form of an LC resonator, with

where we have defined

Firstly, we note how this confirms our previous adiabatic derivation of the quantum capacitance, as, thanks to the summation rule in Eq. (10), we find

At finite frequencies, however, the full diabatic quantum response implies the existence of a quantum inductance \({L}_{{\rm{Q}}}^{mn}\), as observed in the literature for a single QD18,49. The system is thus best modeled as a set of perfect LC resonators in parallel, one per pair of levels and resonant at the energy splitting.

Open Quantum System

It is of interest to go beyond the isolated system and consider the presence of decoherence because of the coupling between the QDs and the environment. The quantum dynamics of an open system can be described via the Lindblad Master Equation (LME)50

where Γl are called tunnel rates, while \({\mathcal{D}}\left({L}_{l}\right)\) is the superoperator causing decoherence effects, described by the jump operators Ll. In this case, Eq. (5) remains valid provided that we now redefine the susceptibility as41

where \({e}^{{{\mathcal{L}}}_{0}(t-\tau )}\) is the unperturbed propagator of the (non-unitary) dynamics, and \(\delta {\mathcal{L}}\) is the (small) perturbation to the time-independent Liouvillian \({{\mathcal{L}}}_{0}\) caused by the excitation. Given the linearity of the LME, we can divide the perturbation as \(\delta {\mathcal{L}}=\delta {{\mathcal{L}}}_{{\rm{H}}}+\delta {{\mathcal{L}}}_{\Gamma }+\delta {{\mathcal{L}}}_{{\rm{L}}}\), where we consider the effect of the rf excitation on the Hamiltonian, the tunnel rates, and the jump operators respectively. Their time evolution can be expressed to first order in the perturbation as

Linearity in Eq. (17) lets us write the total susceptibility as χ(ω) = χH(ω) + χΓ(ω) + χL(ω) and thus, from Eq. (8), the admittance can be synthesized as47,51,52

Notably, this can be thought of in electrical terms as a parallel combination of the three contributions (Fig. 1), which we now discuss in detail. The result in Eq. (17) is valid for any Liouvillian, not necessarily in Lindblad form. However, for the sake of simplicity, we assume that the dynamics of the system is well described by a phenomenological model including relaxation (T1) and pure dephasing (Tϕ) processes. Thus, we can write

where we have defined

Consistently with the Lindblad formalism, we treat dephasing in a Markovian approximation, neglecting the effect of low-frequency noise53,54,55,56,57.

Hamiltonian admittance

The simplest term is the contribution due to the direct perturbation of the Hamiltonian. Similarly to Eq. (6), this reads

In Methods we show that considering the Lindbladian in Eq. (20) leads to the simple modification of Eq. (9)26

where

is the rate of decay of off-diagonal terms in the density matrix58. Therefore, the effect of metastable states is to give χH(ω) a small imaginary part with respect to the isolated system, allowing the open quantum system to dissipate energy, thus curing the divergence of the response exactly at resonance. Notably, we find a diabatic decoherence-induced resistance, discussed in the literature of mesoscopic capacitors13,14,15,16,17,18,59 but notably absent in the literature of equivalent-circuit models of QD systems11,23,24.

Exploring this further, the Choi-Kraus theorem guarantees that \({\Gamma }_{{T}_{2}}^{mn}={\Gamma }_{{T}_{2}}^{nm}\)50. Thus, we find the admittance related to χH as

where we have introduced

and \(\scriptstyle{C}_{{\rm{H}}}^{mn}={\left(\frac{1}{{C}_{{\rm{Q}}}^{mn}}+\frac{1}{{C}_{{\mathcal{D}}}^{mn}}\right)}^{-1}\). As for the isolated system (Eq. (12)), the diabatic response of the Hamiltonian component can be pictured as arising from resonators in parallel, one for each pair of levels. These are now, however, RLC resonators, as the presence of decoherence introduces both a resistive component \({G}_{{\mathcal{D}}}^{mn}\) and an additional capacitance \({C}_{{\mathcal{D}}}^{mn}\) in series with the quantum terms (Fig. 1). Notably, the frequency pulling of \({C}_{{\mathcal{D}}}^{mn}\) cancels out the damping exactly, and the resonance frequency remains unaltered at the value \(\hslash {\omega }_{{\rm{res}}}={E}_{m}-{E}_{n}\).

Sisyphus Admittance

To first order in the excitation, the perturbation of the Lindbladian due to the tunnel rates takes the form

In the literature, this effect has been termed Sisyphus processes, responsible for the resistance of the same name, and has been identified as the main cause of dynamical dissipation in QD systems10,11,21,23,24. The physical cause of Sisyphus processes stems from the dependence of the tunnel rates on energy11. The simplest way to describe time-dependent excitation is the instantaneous eigenvalue approximation (IEA), where the functional form of the time-independent master equation is calculated for the instantaneous eigenvalues of H(t)60. Thus \({\Gamma }_{\pm }^{mn}(t)={\Gamma }_{\pm }\left({E}_{m}(t)-{E}_{n}(t)\right)\). For a small perturbation, this causes the population to relax to equilibrium (see Methods) with rate

However, along one excitation cycle, the resulting modulation of the rates can give rise to excess relaxation,

which is manifested as a resistive term10,21,24.

In Methods, we show how the electrical response arising from the Sisyphus process can be written as

where we have defined

This is a generalization of the Sisyphus conductance derived for the DQD or the single-electron box11,23,24. Notably, Eq. (30) shows how Sisyphus processes generally include also a reactive component, thus inviting us to refer to a Sisyphus admittance that includes both the Sisyphus conductance and the tunneling capacitance24, as they are manifestations of the same physical process. Electrically, the series RC combinations behave as high-pass filters, one for each pair of levels, with corner frequency \({\Gamma }_{{T}_{1}}^{mn}\) (Fig. 1), with the clear physical significance of suppressing unitary processes that would happen on a longer timescale than the lifetime of the levels.

Hermes admittance

The last term contributing to the susceptibility is the perturbation of the jump operators. In the notation of Eq. (18), this reads

where we have defined

Within the IEA, jump operators are usually defined in the instantaneous eigenbasis (IEB) in which H(t) is instantaneously diagonal60,61. Thus, \({L}_{l}(t)={W}^{\dagger }(t){L}_{l}^{{\rm{IEB}}}W(t)\), where the rotation matrix W(t) is such that W†(t)E(t)W(t) = H(t), with E(t) the diagonal matrix containing the instantaneous energies. Incidentally, this term is a requirement to get a valid Lindbladian60,62,63,64. This is clear as, if the tunnel rates depend on the energies of the instantaneous eigenstates, the jump operators must describe transitions between such same levels. Thus, a consistent quantum treatment of Sisyphus processes must account for \(\delta {{\mathcal{L}}}_{{\rm{L}}}\) as well. In Methods, we show how the response reads

This term is a novel effect introduced in this work, and includes the effect of both relaxation (T1) and pure dephasing (Tϕ) processes, which combine to give the total decoherence rate as \({T}_{2}^{-1}={T}_{\phi }^{-1}+{\left(2{T}_{1}\right)}^{-1}\).

Firstly, we note the stark similarity between χH and χL, which is to be expected since the perturbation of the jump operators stems from the changes of the Hamiltonian and its eigendecomposition. Similarities and differences become evident if we analyze the response from the circuit point of view. After some algebra, we can write

where we define

and \(\scriptstyle\gamma ={\left(\frac{{\Gamma }_{{T}_{2}}^{mn}}{{E}_{m}-{E}_{n}}\right)}^{2}\). Notably, also for this term, the admittance corresponds to circuits in parallel, one for each pair of levels (Fig. 1), and the values of the equivalent circuit components are proportional (via γ) to their Hamiltonian counterparts. This highlighs the nature of this term as a state correction, which enters the first-order linear response as a perturbation of the jump operators, defined in the instantaneous eigenbasis. However, we note that the inductance in χH is here replaced by a parallel combination of a (negative) resistor and a (negative) capacitor. Thus, similarly to the Sisyphus term, χL does not resonate65, but rather acts to dampen resonances caused by the Hamiltonian term. We notice how all the terms in χL depend on γ, i.e., on the (squared) ratio between the coherent quantum beat between levels and the decay of their coherent superposition. As a matter of fact, we shall see in the subsequent section how this term dominates over the quantum (Hamiltonian) contribution when the system decoheres faster than its natural frequency (γ > 1), and in this regime it is responsible for the recovery of the semiclassical limit. Expanding on this, it is in fact possible to show (after some algebra) that

which casts a new light on the concept of quantum capacitance. This can now be seen as either the adiabatic limit of the isolated system (as argued above) or as the response of the quantum system in the limit of infinitely fast decoherence (which the literature sometimes defines as the semiclassical limit66,67). Physically, these two views are reconciled by noticing how in both regimes it is impossible for the quantum system to escape its steady state, either because of the adiabaticity of the drive or the suppression of coherent superposition and thus unitary processes.

Lastly, we address the issue of naming the new term χL. As we have seen, this depends on the velocity of decoherence compared to the intrinsic beat of the Hamiltonian dynamics. Thus, in keeping with the mythological theme established with the term ‘Sisyphus’, it seems only fitting to name χL the Hermes susceptibility, from the Greek deity of velocity and mischievousness.

Circuit model of example systems

In this Section, we employ the formalism derived thus far and we showcase its capabilities on two example systems: (i) a DQD charge qubit and (ii) a Majorana qubit formed by a QD coupled to two topological Majorana modes.

Charge qubit

Firstly, we discuss a charge qubit in a DQD, chosen because it is the simplest coupled two-level system and the (semiclassical) Sisyphus admittance and adiabatic quantum capacitance are well known from the literature23,24. In particular, we use the Lindblad equivalent of the semiclassical model employed in refs. 23 and 24, where the Hamiltonian in the charge basis of the two QDs reads

Here, Δ/2 is the tunnel coupling. Relaxation is introduced phenomenologically as61

where \(\Delta E=\sqrt{{\Delta }^{2}+{\varepsilon }^{2}}\) is the energy difference between the ground (\(\left\vert g\right\rangle\)) and excited (\(\left\vert e\right\rangle\)) states, and \(n(\Delta E)={\left({e}^{\Delta E/{k}_{{\rm{B}}}T}-1\right)}^{-1}\). As is common in the literature5,24, we take Γ0 to be independent of energy. The small-signal admittance of the DQD can be found by direct application of the above equations, taking

and, in the absence for now of a dephasing term, \({\Gamma }_{{T}_{2}}=\frac{1}{2}{\Gamma }_{{T}_{1}}\). In particular, considering Eqs. (25), (30), and (34), one obtains

where, notably, \(\left\langle e| \Pi | g\right\rangle =\Delta /\Delta E\) is the dipole matrix element, and the polarization in the energy basis reads \({p}_{g}-{p}_{e}={\Gamma }_{0}/{\Gamma }_{{T}_{1}}\). A quantitative comparison between Eqs. ((41)–(43)) and the input-output and semiclassical admittances is presented in SM II.

In Fig. 2, we showcase our model by considering the effects of increasing the excitation frequency, comparing them to the semiclassical24 and input-output26 results. We choose the case of high temperature (kBT > Δ) to enhance the contribution of the Sisyphus term. For completeness, we additionally carry out a brute-force integration of the LME (blue dots), showing complete agreement with our analytical model. To begin with, we note how, as expected, the semiclassical admittance is recovered for ω → 0. In particular, we see how the width of the peak becomes broader than the mere quantum capacitance (Fig. 2c, i) due to the Sisyphus term, in agreement with the semiclassical theory11,24 and experimental observations68,69. Notably, in this work we obtain the same functional form for Sisyphus resistance and tunneling (Sisyphus) capacitance (Eq. (42)) as Ref. 24, as expected since this term arises from the perturbation of scalars. More specifically, it is possible to show (see Methods) that if ρss is diagonal (as it typically is in thermal equilibrium26,41,66), then \(\delta {{\mathcal{L}}}_{\Gamma }{\rho }_{{\rm{ss}}}\) is also diagonal. Therefore, this term of the LME is perfectly equivalent to a semiclassical (scalar) master equation. In passing, we note that this is not the case for \(\delta {{\mathcal{L}}}_{{\rm{H}}}\) or \(\delta {{\mathcal{L}}}_{{\rm{L}}}\). In contrast to the semiclassical theory, input-output theory ignores the dynamical relaxation process, thus predicting at low excitation frequencies a narrower, temperature-independent26 peak, which cannot faithfully reproduce the LME (Fig. 2i). This discrepancy is further highlighted when one considers the resistive component of the admittance (Fig. 2f), where the Sisyphus term dominates and we obtain the characteristic two lobes24 caused by the dependence of (thermal) relaxation on ΔE. The semiclassical model, however, fails to correctly predict the additional conductance peak at zero detuning, where the Sisyphus term vanishes and dissipation is dominated by \({G}_{{\mathcal{D}}}\) and the Hermes term.

Capacitance (a–c), conductance (b–f) and absolute value of the admittance (g–i) of the DQD charge qubit for increasing frequency at kBT = 2.5Δ and Γ0 = Δ0/10. The line cuts are taken in the adiabatic (ωb = 0.2Δ) and resonant (ωt = 4Δ) regimes. b, c and e, f Show the contribution to real and imaginary parts of the admittance from the Hamiltonian (cyan), Sisyphus (orange) and Hermes (pink) components, while h, i show a comparison between our model and the semiclassical model24 and input-output theory26. We additionally carry out a brute-force integration of the LME (blue dots), showing perfect agreement with our analytical model. Color bars are linear for the ±5% of the values on either side of zero and logarithmic outside.

The situation is reversed when ω > Δ. (Fig. 2c, f, h). We observe the Rabi-induced peak splitting caused by the inductive component in χH, while within the two Rabi wings (ω > ΔE) the reactive component changes sign. Both phenomena are predicted by input-output theory26,27 and circuit QED70,71, and have a simple physical interpretation. The splitting of the peak is caused by the strong response (divergent in the non-dissipative limit) of the quantum system when driven exactly at resonance. Within the wings, the system is driven faster than its natural response frequency, and thus the charge lags behind the excitation, giving rise to a negative reactance. Both observations have been confirmed experimentally19,49,72, while they are obviously absent from the semiclassical (adiabatic) model. A similar peak splitting due to vacuum Rabi is observed also in the conductance of the charge qubit, the response dominated by YH and sharply peaked at resonance. Similarly to the capacitive response at resonance, the large conductance can be understood by the system being efficiently driven by the excitation. This constant interplay of excitation of the quantum system and relaxation through the bath causes a net energy dissipation, which manifests electrically as a resistance. This is further clarified by thinking of the process in the formalism of circuit QED, where instead of charge dynamics, we are invited to keep track of photons exchanged with the cavity, which in turn drive the quantum system26. If the drive is resonant with the energy splitting, photons can efficiently be absorbed by the system being excited in a coherent superposition, which then decays back to equilibrium, leaking energy into the environment.

This demonstrates how our formalism is able to continuously morph between the two regimes, always remaining in agreement with the LME, showcasing how this work unifies the semiclassical and input-output descriptions.

Lastly, we comment on the new Hermes term, which becomes important when, unlike in Fig. 2, \({\Gamma }_{{T}_{2}}\) is comparable with ΔE. To showcase this effect, we introduce a pure dephasing term of the form

which has no semiclassical equivalent. For simplicity, we take Γϕ also independent of energy. Thus, the only necessary modification of Eqs. ((41)–(43)) is redefining \({\Gamma }_{{T}_{2}}={\Gamma }_{\phi }+{\Gamma }_{{T}_{1}}/2\). Consequently, varying Γϕ decouples the effect of χH and χL from the Sisyphus term.

In Fig. 3, we consider the DQD in the resonant regime (Fig. 2c, f, i) and show the evolution of the admittance for increasing Γϕ. For low decoherence rates, we see how the addition of a dephasing term does not qualitatively alter the admittance, which still shows a strong response sharply peaked at resonance (Fig. 3c, f, i) and a change in the sign of the reactance (Fig. 3f), a phenomenon well described by input-output theory (Fig. 3i). When \({\Gamma }_{{T}_{2}}\) approaches ΔE, however, not only do the resonant peaks become broader, but the Hermes contribution starts to become more relevant, in the shape of a single peak.

Capacitance (a–c), conductance (d–f) and absolute value of the admittance (g–i) of the DQD charge qubit in the resonant regime (ω = 4Δ) for increasing dephasing rate Γϕ at kBT = 2.5Δ, and Γ0 = Δ0/10. The line cuts are taken in the low-dephasing (Γϕ = 0.02Δ) and high-dephasing (Γϕ = 7.5Δ) regimes. b, c and e, f Show the contribution to real and imaginary part of the admittance from the Hamiltonian (cyan), Sisyphus (orange) and Hermes (pink) components, while (h, i) show a comparison between our model and the semiclassical model24 and input-output theory26. We additionally carry out a brute-force integration of the LME (blue dots), showing perfect agreement with our analytical model. Scale bars are linear within ± 5% and logarithmic outside.

This trend continues up to the point where the system decoheres faster than the timescales of the unitary dynamics (\({\Gamma }_{{T}_{2}} > \Delta E\)). In this case, we see how the Hermes term begins to dominate over the Hamiltonian (Fig. 3b, e), and the Rabi peaks disappear completely, the admittance having the shape now of a more conventional single peak centered at ε = 0. In fact, when \({\Gamma }_{{T}_{2}}\gg \Delta E\), we completely recover the semiclassical prediction, as one would expect from the limit of very high decoherence (Fig. 3i). Unlike in the adiabatic regime, however, we see that the resistive component also takes the shape of a zero-centred peak rather than the Sisyphus lobes (Fig. 2i). This is the physical manifestation of the fact that in this regime the dominant process is not the dynamical relaxation, but rather the dynamical loss of coherence (and thus leakage of quantum information), which is most efficient at ε = 0, where the dipole of the system is largest.

Therefore, we stress how the inclusion of the Hermes term is not only crucial to correctly reproduce the results from the LME, but, most importantly, to correctly recover the semiclassical limit (Eq. (37)), as desirable in any complete and consistent modeling effort.

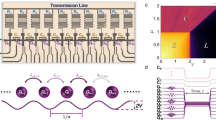

Majorana qubit

As a second example, we discuss the equivalent admittance of a Majorana qubit5,37,38,39,73,74,75,76,77,78. Typically, a Majorana qubit is based on a topological one-dimensional system housing two Majorana zero modes, which make up the computational basis. For concreteness, in this work we concentrate on the simplest incarnation of such a qubit, in which the topological modes are coupled to an ancillary QD5,73. However, our formalism can be generalized naturally to more-recent Majorana-qubit proposals37,78, as well as similar non-abelian systems that lack formal topological protection, such as Kitaev chains and ‘poor man’s Majorana’ bound states39.

When an auxiliary QD is coupled to two Majorana zero modes, it can be used to read out the joint Majorana parity, i.e., to sense the occupation of the (non-local) fermion composed by the two Majorana modes5,39. The effective low-energy Hamiltonian of such a system simply reads

where ε is the detuning of the ancillary QD, and p ∈ {even, odd} is the joint Majorana parity5. Δp represents the Majorana-QD coupling in each parity state, and can be tuned experimentally by changing barrier voltages and the magnetic flux threading the device. Most importantly, generally Δeven ≠ Δodd, and, thus, the parity state can be measured through the admittance of the coupled QD5. For the sake of simplicity, in the following discussion we will only include decoherence processes (modeled as in Eqs. (39)) within the even and odd sectors, while ignoring processes that can alter the Majorana parity, making the (realistic) assumption that they are negligible within the typical timescales of qubit readout75,79.

We now consider admittances of the even and odd states, as well as the absolute value of their difference Yeven − Yodd, which directly translates to the visibility of the readout of the two states5,12. These quantities are shown in Fig. 4 as a function of the QD detuning for the example parameters Δeven = 2.5 GHz and Δodd = 0.5 GHz. From Fig. 4e it is clear that in the adiabatic limit, both states have a non-zero admittance, thus creating additional challenges for readout when compared to other qubit systems5. This, however, can be obviated by measuring at finite frequency. In particular, by choosing a readout frequency Δodd < ω < Δeven, one can use the Rabi-induced peak splitting to suppress the admittance of the less-coupled mode (odd in this case) at ε = 0, while the more-coupled mode remains below resonance and still shows a zero-centered peak, as shown in Fig. 4d. The same panel, furthermore, shows how, while the odd state is indeed dark for ε = 0, the Rabi wings give a strong response for \({\varepsilon }_{{\rm{odd}}}=\sqrt{\omega -{\Delta }_{{\rm{odd}}}}\), where the odd subspace is resonant with the excitation. Thus, in this setting, one can selectively choose which state is bright by changing the readout voltages. This capability has been discussed in the context of other qubit architectures, and has been proposed to have several advantages with respect to more conventional readout techniques based on negative measurements, such as the ability to check for leakage outside the computational basis12,80. Our formalism thus predicts the possibility of selectively (and dynamically) choosing the bright state of a readout measurement by exploiting the diabatic properties of the system’s admittance, overcoming the limitation of this platform in the adiabatic regime.

a, b Absolute value of the admittance of the auxiliary QD in case of the even (a) and odd (b) joint Majorana parity. c Absolute value of the admittance difference between the two parity states, which directly translates to the visibility of the readout of the two states. d, e ∣Yeven − Yodd∣ in the resonant (d) and adiabatic (e) regime, showing the benefit of performing readout at Δodd < ω < Δeven to suppress the admittance of the odd state at ε = 0, which instead has a strong response at \({\varepsilon }_{{\rm{odd}}}=\sqrt{\omega -{\Delta }_{{\rm{odd}}}}\), where it is resonant with the excitation. Color bars are linear below 10−2 and logarithmic above.

Discussion

We have presented a Lindblad perturbation theory for quantum modeling of the electrical response of a generic QD device, highlighting the link between the susceptibility of a quantum system and its small-signal electrical admittance, from which stems a universal small-signal equivalent circuit. This condenses the perturbed quantum dynamics into linear circuit components, making use uniquely of frequency-independent variable components, simplifying the implementation of the model and providing key insights into the complex response of the Lindbladian. Our model shows how semiclassical and input-output approaches describe two facets of the decohering quantum dynamics, overlapping in the description of the adiabatic and perfectly coherent limit: the quantum capacitance. Moreover, we introduce a novel contribution to the response, named the Hermes admittance, which casts a new and complementary light on the concept of quantum capacitance, which can additionally be seen as the response of the quantum system when decoherence is so fast that all coherent processes are suppressed (i.e., the semiclassical limit).

Our approach provides an intuitive model for the small-signal electrical response of any quantum system, retaining the complexity of Lindblad circuit QED while being readily implementable within circuit simulators, showcasing it on two example systems. We have described the electrical response at high frequency of a DQD charge qubit, demonstrating the ability of the model to transition continuously from the Sisyphus-broadened adiabatic capacitance to the Rabi-induced peak splitting predicted by circuit QED. The single, zero-centered peak of the quantum capacitance is then recovered when considering fast dephasing, thanks to the inclusion of the Hermes term. The phenomenon of resonant peak splitting has then been exploited to showcase the response of a Majorana qubit composed of two Majorana zero modes coupled to an ancillary QD. The admittance of the QD can be used to read the state of the qubit, and we showcase how the diabatic response of the system can be leveraged to selectively make either state dark by varying the readout detuning. We stress that such a scheme exploits the high-frequency capabilities of the model to get around limitations that cannot be overcome in the adiabatic regime, thus highlighting how accurate modeling of the electrical response of quantum systems is key to unlocking the full potential of upcoming quantum technologies.

Methods

Numerical calculation of the gate current

In this section, we will show how to derive the admittance from Eq. (2) for an arbitrary perturbation of a markovian time evolution. In particular, we will consider the most general case of a Lindbladian of the type

where we consider \(\delta {\mathcal{L}}\) to be a small perturbation to \({{\mathcal{L}}}_{0}\). We will then be able to write the time evolution as

where we assume that ρ(t) remains mostly diagonal and

for the stationary state.

We must now compute IG(t). We can write, however,

Semiclassically, we may simply write

which, to zeroth perturbative order, can be written as

leading to Eq. (4) making use of \(\frac{d}{dt}=\frac{d}{d\varepsilon }\frac{d\varepsilon }{dt}\) 23,24. However, this neglects any redistribution of the state occupation, either thermal or due to coherent processes. These may be accounted for in the Lindblad formalism, which by definition of the Lindbladian, allows us to write Eq. (49) as

To first order in the perturbation, this becomes

echoing the fact that δρ(t) is, to first order, the solution of the equation

It is interesting to point out how Eq. (54) is the direct Lindblad generalization of the expression of tunneling capacitance presented in Ref. 80. However, the necessity of solving a complex time-dependent differential equation to obtain δρ(t) makes this particular formulation only viable for numerical treatments.

Equilibrium populations

In this work, we have seen how the calculation of the susceptibility requires knowledge of the equilibrium probability of occupation. Therefore, for the benefit of the reader, we include this short Appendix on the means of calculations of the equilibrium populations of a quantum system.

If the dynamics of the system is already described by an LME via a superoperator \({{\mathcal{L}}}_{0}\), the steady-state density matrix will simply read

which, for the non-driven system, is simply the thermal equilibrium. Therefore, finding ρss simply turns into an eigenvalue problem of finding the kernel of \({{\mathcal{L}}}_{0}\). This can be easily done, in the general case, in Fock-Liouville space50,81, where it is possible to turn the superoperator eigendecomposition into a matrix eigenvalue problem41.

In some cases, however, the coupling with the environment will be small enough to be negligible in the dynamics within an rf cycle, but nonetheless large enough to dictate the equilibrium steady state in the long-time regime. In this case, as we have already discussed, the density matrix will become diagonal, and one only needs to find the occupation probability in thermal equilibrium. The simplest way to do so is to consider the system coupled to a bosonic bath (i.e., phonons in the crystal), which is responsible for T1-type processes. The Hamiltonian in this case reads

where b is the annihilation operator on the bath. In this case, the LME reads

with

where we assume for the summation that Em > En if m > n, and that there is no forbidden transition. In the rotating-wave approximation, we simply take23,26

as the number of bosons resonant with the transition. For simplicity, we take Γ0 to be independent of energy and the same for all transitions. Typically, one could consider a Debye model26

where \(\frac{1}{{e}^{E/{k}_{{\rm{B}}}T}-1}\) is the Bose-Einstein distribution and \(E/{{\mathcal{E}}}_{0}\) represents the bath spectral density. On the diagonal of the density matrix, these jump operators take the form of a Pauli-like master equation, reading

where, for ease of notation, we have defined Nmn = N(Em − En). Therefore, the equilibrium probabilities are found as the eigenvalues of the rate matrix

from which it is clear that the steady state does not depend on the choice of Γ0. Moreover, in the limits of very low (Nmn ≪ 1) or very high (Nmn ≫ 1) temperature, the steady state does not depend on \({{\mathcal{E}}}_{0}\)26,58.

Susceptibility derivation

In this section, we shall sketch for completeness and pedagogical value the necessary mathematical steps to derive the susceptibility formulas in the main text from the general expression in Eq. (17) (and Eq. (6)).

Hamiltonian susceptibility

The first term we tackle is the case of the isolated system. As mentioned in the main text, Eq. (9) is equivalent to Ref. 26. However, we report it here for completeness and to illustrate the physical origin of the imaginary response in Eq. (23), as well as it naturally extending to describe χH in Eq. (23).

To begin with, we can define

through which the operators evolve in the interaction picture as

Therefore, making the commutator explicit,

We can now take the case when ρss is purely diagonal. This may not be the case for a perfectly Hamiltonian dynamics. However, any interaction with the environment will lead to exponentially decaying off-diagonal terms66. Therefore, we can consider this as the limit of \({\Gamma }_{{T}_{2}}^{mn}\to 0\). For a practical way of computing such probabilities, a method is presented in the Methods. In this case, we can use the fact that

and the cyclic property of the trace to write the first term in Eq. (65) as

Now, we can use the completeness relation

where \({\mathcal{I}}\) is the identity, to obtain

Performing similar manipulation for the other term in Eq. (65) and making the time evolution of bra and ket explicit, we find

whose Fourier transform is Eq. (9).

This derivation allows to immediately consider the expression for χH(t, τ) in the case of the Lindblad dynamics. Using the cyclic property of the trace, in fact, we can write the equivalent of Eq. (70) as

where we have defined \({\Gamma }_{{T}_{2}}^{mn}=\frac{1}{2}{\Gamma }_{{T}_{1}}^{mn}+{\Gamma }_{\phi }^{mn}\) as in the main text, and used the fact that [Π, ρss] is real and antihermitian, and thus non-zero only off the diagonal, as well as

Taking the Fourier transform, we obtain Eq. (23).

Sisyphus susceptibility

To derive the general form of the Sisyphus admittance, we must write down the variation of T1 with respect to energy. Assuming without loss of generality a simple form of Eq. (58), we can write

where, for compactness, we write

We can now notice that, for a diagonal density matrix,

En passant, we note that the \(\delta {{\mathcal{L}}}_{\Gamma }\) due to pure dephasing processes vanishes over a diagonal steady-state ρss. Therefore, even if the dephasing rate has an energy dependence, it only contributes to \({\Gamma }_{{T}_{2}}^{mn}\) in Eq. (23), but does not introduce additional terms in the admittance.

Therefore,

If we now define

using the definitions in Eq. (30), and making use of Eqs. (76) and (17), we easily obtain

whose Fourier transform reads

and

Hermes susceptibility

The first step towards deriving the Hermes admittance is to expand the rotation matrix W(t), which diagonalizes the Hamiltonian instantaneously, to first order. To do so, we can notice that

Instantaneously, to first order,

Thus,

with

Consequently, the perturbation of the jump operators reads

With some more algebra, it is possible to write

We must now consider relaxation and dephasing separately. The Hermes susceptibility of T1 processes can be calculated making use of the algebra presented above, with the additional fact that

With a similar formalism, it is also possible to include pure dephasing (Tϕ) processes, which are usually described by a diagonal jump operator \({\tau }_{mn}^{z}\). Carrying out the algebra and making use of Eq. (87), we find the results in Eq. (88).

Notably, one can express both superoperators in terms of Λmn, and they only differ in their dependence on the probabilities. The formulae greatly simplify if we consider the combined action of relaxation and dephasing. In the notation above and taking, without loss of generality, Em > En, the perturbation to the jump operators reads

where we have introduced the pure dephasing rate Γϕ.

Before proceeding, we note that in such a Lindbladian the equilibrium probabilities and the relaxation rates are linked by the principle of detailed balance as

Combining Eqs. (88) and (90) we find, after some algebra,

where we have defined

Interestingly, there is a factor of 2 between the contributions of relaxation and dephasing, reflecting the fact that the decay of the coherences reads \(\scriptstyle{T}_{2}^{-1}={\left({T}_{\phi }\right)}^{-1}+{\left(2{T}_{1}\right)}^{-1}\).

From Eq. (91) it follows directly that we can write the Hermes susceptibility as

the Fourier transform of which is Eq. (34) in the main text.

Data availability

No new data was generated in the writing of this work.

References

Wallraff, A. et al. Strong coupling of a single photon to a superconducting qubit using circuit quantum electrodynamics. Nature 431, 162 (2004).

Petersson, K. D. et al. Circuit quantum electrodynamics with a spin qubit. Nature 490, 380–383– (2012).

Samkharadze, N. et al. Strong spin-photon coupling in silicon. Science 359, 1123–1127 (2018).

Mi, X. et al. A coherent spin-photon interface in silicon. Nature 555, 599–603 (2018).

Derakhshan Maman, V., Gonzalez-Zalba, M. & Pályi, A. Charge noise and overdrive errors in dispersive readout of charge, spin, and majorana qubits. Phys. Rev. Appl. 14, 064024 (2020).

Burkard, G., Gullans, M. J., Mi, X. & Petta, J. R. Superconductor-semiconductor hybrid-circuit quantum electrodynamics. Nat. Rev. Phys. 2, 129–140 (2020).

van Dijk, J. et al. Impact of classical control electronics on qubit fidelity. Phys. Rev. Appl. 12, 044054 (2019).

Sillanpää, M. A. et al. Direct observation of josephson capacitance. Phys. Rev. Lett. 95, 206806 (2005).

Oakes, G. A. et al. Fast high-fidelity single-shot readout of spins in silicon using a single-electron box. Phys. Rev. X 13, 011023 (2023).

Ciccarelli, C. & Ferguson, A. J. Impedance of the single electron transistor at radio-frequencies. N. J. Phys. 13, 093015 (2011). ArXiv:1108.3463 [cond-mat].

Vigneau, F. et al. Probing quantum devices with radio-frequency reflectometry. Appl. Phys. Rev. 10, 021305 (2023).

von Horstig, F.-E. et al. Electrical readout of spins in the absence of spin blockade. arXiv https://doi.org/10.48550/arXiv.2403.12888 (2024).

Büttiker, M., Thomas, H. & Prêtre, A. Mesoscopic capacitors. Phys. Lett. A 180, 364–369 (1993).

Büttiker, M., Prêtre, A. & Thomas, H. Dynamic conductance and the scattering matrix of small conductors. Phys. Rev. Lett. 70, 4114–4117 (1993).

Nigg, S. E. & Büttiker, M. Quantum to classical transition of the charge relaxation resistance of a mesoscopic capacitor. Phys. Rev. B. 77, 085312 (2008).

Gabelli, J. et al. Violation of kirchhoff’s laws for a coherent rc circuit. Science 313, 499–502 (2006).

Bruhat, L. et al. Cavity photons as a probe for charge relaxation resistance and photon emission in a quantum dot coupled to normal and superconducting continua. Phys. Rev. X 6, 021014 (2016).

Wang, J., Wang, B. & Guo, H. Quantum inductance and negative electrochemical capacitance at finite frequency in a two-plate quantum capacitor. Phys. Rev. B 75, 155336 (2007).

Ibberson, D. J. et al. Large dispersive interaction between a cmos double quantum dot and microwave photons. PRX Quant. 2, 020315 (2021).

Burkard, G. & Petta, J. R. Dispersive readout of valley splittings in cavity-coupled silicon quantum dots. Phys. Rev. B 94, 195305 (2016).

Persson, F., Wilson, C. M., Sandberg, M., Johansson, G. & Delsing, P. Excess dissipation in a single-electron box: the sisyphus resistance. Nano Lett. 10, 953–957 (2010). ArXiv:0902.4316 [cond-mat].

Peri, L., Oakes, G. A., Cochrane, L., Ford, C. J. B. & Gonzalez-Zalba, M. F. Beyond-adiabatic quantum admittance of a semiconductor quantum dot at high frequencies: rethinking reflectometry as polaron dynamics. Quantum 8, 1294 (2024).

Mizuta, R., Otxoa, R. M., Betz, A. C. & Gonzalez-Zalba, M. F. Quantum and tunneling capacitance in charge and spin qubits. Phys. Rev. B 95, 045414 (2017).

Esterli, M., Otxoa, R. M. & Gonzalez-Zalba, M. F. Small-signal equivalent circuit for double quantum dots at low-frequencies. Appl. Phys. Lett. 114, 253505 (2019).

Kohler, S. Dispersive readout of adiabatic phases. Phys. Rev. Lett. 119, 196802 (2017).

Kohler, S. Dispersive readout: universal theory beyond the rotating-wave approximation. Phys. Rev. A 98, 023849 (2018).

Benito, M., Mi, X., Taylor, J. M., Petta, J. R. & Burkard, G. Input-output theory for spin-photon coupling in si double quantum dots. Phys. Rev. B 96, 235434 (2017).

Blais, A., Grimsmo, A. L., Girvin, S. M. & Wallraff, A. Circuit quantum electrodynamics. Rev. Mod. Phys. 93, 025005 (2021).

Shevchenko, S. N., Ashhab, S. & Nori, F. Landau-zener-stuckelberg interferometry. Phys. Rep. 492, 1–30 (2010).

Ivakhnenko, O. V., Shevchenko, S. N. & Nori, F. Nonadiabatic landau-zener-stückelberg-majorana transitions, dynamics, and interference. Phys. Rep. 995, 1–89 (2023).

Srinivasan, S. J., Hoffman, A. J., Gambetta, J. M. & Houck, A. A. Tunable coupling in circuit quantum electrodynamics using a superconducting charge qubit with a v-shaped energy level diagram. Phys. Rev. Lett. 106, 083601 (2011).

Yamamoto, T., Pashkin, Y. A., Astafiev, O., Nakamura, Y. & Tsai, J. S. Demonstration of conditional gate operation using superconducting charge qubits. Nature 425, 941–944 (2003).

Guo, K. S. et al. Methods for transverse and longitudinal spin-photon coupling in silicon quantum dots with intrinsic spin-orbit effect. arXiv http://arxiv.org/abs/2308.12626 (2023).

Burkard, G., Ladd, T. D., Pan, A., Nichol, J. M. & Petta, J. R. Semiconductor spin qubits. Rev. Mod. Phys. 95, 025003 (2023).

Bonsen, T. et al. Probing the jaynes-cummings ladder with spin circuit quantum electrodynamics. Phys. Rev. Lett. 130, 137001 (2023).

Undseth, B. et al. Nonlinear response and crosstalk of electrically driven silicon spin qubits. Phys. Rev. Appl. 19, 044078 (2023).

Smith, T. B., Cassidy, M. C., Reilly, D. J., Bartlett, S. D. & Grimsmo, A. L. Dispersive readout of Majorana qubits. PRX Quant. 1, 020313 (2020).

Rainis, D. & Loss, D. Majorana qubit decoherence by quasiparticle poisoning. Phys. Rev. B 85, 174533 (2012).

Tsintzis, A., Souto, R. S., Flensberg, K., Danon, J. & Leijnse, M. Majorana qubits and non-abelian physics in quantum dot-based minimal Kitaev chains. PRX Quant. 5, 010323 (2024).

Park, S. et al. From adiabatic to dispersive readout of quantum circuits. Phys. Rev. Lett. 125, 077701 (2020).

Albert, V. V., Bradlyn, B., Fraas, M. & Jiang, L. Geometry and response of lindbladians. Phys. Rev. X 6, 041031 (2016).

Buric, N. & Radonjic, M. Uniquely defined geometric phase of an open system. Phys. Rev. A 80, 014101 (2009).

Sarandy, M. S., Duzzioni, E. I. & Moussa, M. H. Y. Dynamical invariants and nonadiabatic geometric phases in open quantum systems. Phys. Rev. A 76, 052112 (2007).

van der Wiel, W. G. et al. Electron transport through double quantum dots. Rev. Mod. Phys. 75, 1–22 (2002).

Ruskov, R. & Tahan, C. Longitudinal (curvature) couplings of an n-level qudit to a superconducting resonator at the adiabatic limit and beyond. Phys. Rev. B 109, 245303 (2024).

Foster, R. M. A reactance theorem. Bell Syst. Tech. J. 3, 259–267 (1924).

Nigg, S. E. et al. Black-box superconducting circuit quantization. Phys. Rev. Lett. 108, 240502 (2012).

Solgun, F., Abraham, D. W. & DiVincenzo, D. P. Blackbox quantization of superconducting circuits using exact impedance synthesis. Phys. Rev. B 90, 134504 (2014).

Frey, T. et al. Quantum dot admittance probed at microwave frequencies with an on-chip resonator. Phys. Rev. B 86, 115303 (2012).

Manzano, D. A short introduction to the Lindblad master equation. AIP Adv. 10, 025106 (2020).

Zinn, M. K. Network representation of transcendental impedance functions. Bell Syst. Tech. J. 31, 378–404 (1952).

Montgomery, C. G., Dicke, R. H. & Purcell, E. M. Principles of Microwave Circuits. Revised ed. edition, Vol. 504 (The Institution of Engineering and Technology, London, U.K, 1987).

Bergli, J., Galperin, Y. M. & Altshuler, B. L. Decoherence in qubits due to low-frequency noise. N. J. Phys. 11, 025002 (2009).

Coish, W. A., Fischer, J. & Loss, D. Exponential decay in a spin bath. Phys. Rev. B 77, 125329 (2008).

Galperin, Y. M., Altshuler, B. L. & Shantsev, D. V. Low-frequency noise as a source of dephasing of a Qubit. In, Fundamental Problems of Mesoscopic Physics. NATO Science Series II: Mathematics, Physics and Chemistry (eds. Lerner, I. V., Altshuler, B. L. & Gefen, Y.) 141–165 (Springer Netherlands, Dordrecht, 2004).

Laikhtman, B. D. General theory of spectral diffusion and echo decay in glasses. Phys. Rev. B 31, 490–504 (1985).

Lutchyn, R. M., Cywiński, L., Nave, C. P. & Das Sarma, S. Quantum decoherence of a charge qubit in a spin-fermion model. Phys. Rev. B 78, 024508 (2008).

Kohler, S., Lehmann, J. & Hänggi, P. Driven quantum transport on the nanoscale. Phys. Rep. 406, 379–443 (2005).

Cottet, A., Mora, C. & Kontos, T. Mesoscopic admittance of a double quantum dot. Phys. Rev. B 83, 121311 (2011).

Yamaguchi, M., Yuge, T. & Ogawa, T. Markovian quantum master equation beyond adiabatic regime. Phys. Rev. E 95, 012136 (2017).

Oakes, G. A. et al. A quantum dot-based frequency multiplier. arXiv https://doi.org/10.1103/PRXQuantum.4.020346 (2022).

Albash, T., Boixo, S., Lidar, D. A. & Zanardi, P. Quantum adiabatic Markovian master equations. N. J. Phys. 14, 123016 (2012).

Ikeda, T., Chinzei, K. & Sato, M. Nonequilibrium steady states in the Floquet-lindblad systems: van Vleck’s high-frequency expansion approach. SciPost Phys. Core 4, 033 (2021).

Mori, T. Floquet states in open quantum systems. Annu. Rev. Condens. Matter Phys. 14, 35–56 (2023).

Alavi, S. M. M., Mahdi, A., Payne, S. J. & Howey, D. A. Identifiability of generalized randles circuit models. IEEE Trans. Control Syst. Technol. 25, 2112–2120 (2017).

Kohler, S., Dittrich, T. & Hänggi, P. Floquet-markovian description of the parametrically driven, dissipative harmonic quantum oscillator. Phys. Rev. E 55, 300–313 (1997).

Rudner, M. S. & Lindner, N. H. The Floquet engineer’s handbook. arXiv http://arxiv.org/abs/2003.08252 (2020).

DiCarlo, L. et al. Differential charge sensing and charge delocalization in a tunable double quantum dot. Phys. Rev. Lett. 92, 226801 (2004).

Hu, Y. et al. A ge/si heterostructure nanowire-based double quantum dot with integrated charge sensor. Nat. Nanotechnol. 2, 622–625 (2007).

Manucharyan, V. E., Baksic, A. & Ciuti, C. Resilience of the quantum Rabi model in circuit QED. J. Phys. A. Math. Theor. 50, 294001 (2017).

Toida, H., Nakajima, T. & Komiyama, S. Vacuum rabi splitting in a semiconductor circuit QED system. Phys. Rev. Lett. 110, 066802 (2013).

Zhou, X. et al. Single electrons on solid neon as a solid-state qubit platform. Nature 605, 46–50 (2022).

Flensberg, K. Non-abelian operations on majorana fermions via single-charge control. Phys. Rev. Lett. 106, 090503 (2011).

Gharavi, K., Hoving, D. & Baugh, J. Readout of majorana parity states using a quantum dot. Phys. Rev. B 94, 155417 (2016).

Karzig, T. et al. Scalable designs for quasiparticle-poisoning-protected topological quantum computation with majorana zero modes. Phys. Rev. B 95, 235305 (2017).

Kitaev, A. Y. Unpaired majorana fermions in quantum wires. Phys. Uspekhi 44, 131 (2001).

Knapp, C., Karzig, T., Lutchyn, R. M. & Nayak, C. Dephasing of majorana-based qubits. Phys. Rev. B 97, 125404 (2018).

Plugge, S., Rasmussen, A., Egger, R. & Flensberg, K. Majorana box qubits. N. J. Phys. 19, 012001 (2017).

Karzig, T., Cole, W. S. & Pikulin, D. I. Quasiparticle poisoning of majorana qubits. Phys. Rev. Lett. 126, 057702 (2021).

Lundberg, T. et al. Non-reciprocal pauli spin blockade in a silicon double quantum dot. npj Quant. Inform. 10, 28 (2021).

Am-Shallem, M., Levy, A., Schaefer, I. & Kosloff, R. Three approaches for representing lindblad dynamics by a matrix-vector notation. arXiv http://arxiv.org/abs/1510.08634 (2015).

Acknowledgements

The authors acknowledge G. Burkard and A. Pályi for useful discussions. L.P. acknowledges the UK Engineering and Physical Sciences Research Council (EPSRC) via the Cambridge NanoDTC (EP/L015978/1) and the Winton Programme for the Physics of Sustainability. M.F.G.Z. acknowledges a UKRI Future Leaders Fellowship [MR/V023284/1]. MB acknowledges funding from the Emmy Noether Programme of the German Research Foundation (DFG) under grant no. BE 7683/1-1.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

L.P. conceived and developed the theoretical framework and performed the calculations. M.B., C.J.B.F., and M.F.G.Z. supervised the work. All authors contributed to the discussion and interpretation of results.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Peri, L., Benito, M., Ford, C.J.B. et al. Unified linear response theory of quantum electronic circuits. npj Quantum Inf 10, 114 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41534-024-00907-9

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41534-024-00907-9

This article is cited by

-

Compact quantum dot models for analog microwave co-simulation

npj Quantum Information (2025)