Abstract

We give a causal inference scheme using quantum observations alone for a case with both temporal and spatial correlations: a bipartite quantum system with measurements at two times. The protocol determines compatibility with five causal structures distinguished by the direction of causal influence and whether there are initial correlations. We derive and exploit a closed-form expression for the spacetime pseudo-density matrix (PDM) for many times and qubits. This PDM can be determined by light-touch coarse-grained measurements alone. We prove that if there is no signalling between two subsystems, the reduced state of the PDM cannot have negativity, regardless of initial spatial correlations. In addition, the protocol exploits the time asymmetry of the PDM to determine the temporal order. The protocol succeeds for a state with coherence undergoing a fully decohering channel. Thus coherence in the channel is not necessary for the quantum advantage of causal inference from observations alone.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Identifying cause-effect relations from observed correlations is at the core of a wide variety of empirical science1,2. Determining the causal structure, i.e. which variables influence others, is known as causal inference. Causal inference is well-known to be important in understanding medical trials3,4, and also appears in a range of machine learning applications5. For example, by understanding the causal factors that give rise to different linguistic patterns, machine learning models can be trained to generate more accurate and meaningful text6.

Causal inference can, in principle, be undertaken via intervening in the system2,3. Intervening to set a random variable to particular values in a controlled manner can be used to determine what other random variables that random variable influences. At the same time, e.g. in medical contexts4, interventions may be costly or infeasible, motivating investigations into partial causal inference from observations2,7,8.

Similar questions have recently emerged concerning causal relations in quantum processes9,10,11,12,13,14,15,16,17,18,19,20,21,22,23,24. Interventions, like resetting the state of quantum systems, have been considered25,26,27,28,29,30,31,32,33. It is known that in the classical case, observations alone are, in general, not sufficient to perform causal inference, which is connected to the famous phrase ‘correlation does not imply causation’. A natural question is, therefore, to identify minimal interventions and observations needed to determine causal relations in the quantum case25. It remains an open question to what extent observations (measurements) in the quantum case, which come together with an inescapable small disturbance, are sufficient for causal inference. How ‘light-touch’ can quantum causal inference be?

We here address this question in the case of bipartite quantum systems of arbitrary numbers of qubits and measurements at two times. To be precise, we formulate the quantum causal inference problem as follows. As shown in Fig. 1, the observer has data from observing two quantum systems A and B. The observer wants to know the causal structure of the process of generating the data. In line with Reichenbach’s principle1 we allow for five causal structures that are to be distinguished (see Fig. 1). These structures are distinguished by the direction of any causal influence between A and B, and by whether there are initial correlations or not. Scenarios with causal influence in both directions (loops), such as global unitaries on A and B are excluded, such that there is a well-defined causal direction1,2 (nevertheless many of our results apply to such cases). We devise an explicit scheme for determining which causal structures are compatible with the data. The scheme is derived via the pseudo-density matrix (PDM) formalism, which assigns a PDM to the data table of experiments involving measurements on systems at several times12. Firstly one identifies whether there is negativity in certain reduced states of the PDM. Then one evaluates the time asymmetry of the PDM. The scheme employs no reset-type interventions but rather only coarse-grained projective measurements, thereby proving that causal inference can indeed be achieved with a very light touch in the quantum case.

The observer gains data from observing two quantum systems A (white ball) and B (red ball) which is correlated. In line with Reichenbach’s principle, we allow for five possible causal structures: (1) A has direct influence on B; (2) B has a direct influence on A; (3) there is a common cause (dashed ball) acting on A and B, meaning correlations in the initial state; (4) a combination of cases 1 and 3; 5) a combination of cases 2 and 3. The observer wants to determine which of those possible causal structures is the case.

We proceed as follows. After introducing the PDM formalism we present the main theorems, the protocol and an example. Further details are provided in the Supplementary Information.

Results

PDM formalism for measurements at multiple times, systems

The pseudo-density matrix (PDM) formalism, developed to treat space and time equally12, provides a general framework for dealing with spatial and causal (temporal) correlations. Research on single-qubit PDMs has yielded fruitful results34,35,36,37,38,39,40,41,42. For example, recent studies have utilised quantum causal correlations to set limits on quantum communication42 and to understand how dynamics emerge from temporal entanglement37. Furthermore, the PDM approach has been used to resolve causality paradoxes associated with closed time-like curves39.

The PDM generalises the standard quantum n-qubit density matrix to the case of multiple times. The PDM is defined as

where \({\tilde{\sigma }}_{{i}_{\alpha }}\in {\{{\sigma }_{0},{\sigma }_{1},{\sigma }_{2},{\sigma }_{3}\}}^{\otimes n}\) is an n-qubit Pauli matrix at time tα. \({\tilde{\sigma }}_{{i}_{\alpha }}\) is extended to an observable associated with up to m times, \({\otimes }_{\alpha = 1}^{m}{\tilde{\sigma }}_{{i}_{\alpha }}\) that has expectation value \(\langle {\{{\tilde{\sigma }}_{{i}_{\alpha }}\}}_{\alpha = 1}^{m}\rangle\). We shall return later to what measurement this expectation value corresponds to. The standard quantum density matrix is recovered if the Hilbert spaces for all but one time, say \({t}_{{\alpha }^{{\prime} }}\) are traced out, i.e. \({\rho }_{{\alpha }^{{\prime} }}={{\rm{Tr}}}_{\alpha \ne {\alpha }^{{\prime} }}{R}_{1...m}\). The PDM is Hermitian with unit trace but may have negative eigenvalues.

The negative eigenvalues of the PDM appear in a measure of temporal entanglement known as a causal monotone f(R)12. Analogously to the case of entanglement monotones43, in general, f(R) is required to satisfy the following criteria: (I) f(R) ≥ 0, (II) f(R) is invariant under local change of basis, (III) f(R) is non-increasing under local operations, and (IV) ∑ipif(Ri) ≥ f(∑piRi). Those criteria are satisfied by12

If R has negativity, f(R) > 0. An intuition for why f(R) serves as a sign of causal influence is that negative eigenvalues tell you that the PDM is associated with measurements multiple times; in the case of a single time, there would be a standard density matrix with no negativity.

The PDM negativity f(R) can thus be used to distinguish, at least in some cases, whether the PDM corresponds to two qubits at one time or one qubit at two times. This can be viewed as a simple form of causal inference, raising the question of whether the inference involving two parties (of multiple qubits) at multiple times depicted in Fig. 1 can be undertaken in a similar manner. A key challenge in this direction is to find a closed-form expression for the PDM R, from which one can see whether f(R) > 0.

Closed form for m-time n-qubit PDMs

We derive a closed-form expression for the PDM for n qubits and two times, before generalising the expression to m times.

Consider the PDM of n qubits undergoing a channel \({{\mathcal{M}}}_{2| 1}\) between times t1 and t2. In order to fully define the PDM of Eq. (1) it is necessary to further define how the Pauli expectation values \(\langle {\{{\tilde{\sigma }}_{{i}_{\alpha }}\}}_{\alpha = 1}^{m}\rangle\) are measured, since that choice impacts the states in between the measurements. We, importantly, choose coarse-grained projectors

where α in iα labels the time of the measurement. These are coarse-grained in the sense of being sums of rank-1 projectors, and by inspection generate lower measurement disturbance than fine-grained projectors in general. The coarse-grained projectors’ probabilities determine the expectation values \(\langle {\{{\tilde{\sigma }}_{{i}_{\alpha }}\}}_{\alpha = 1}^{m}\rangle\). (See Supplementary Information for a circuit to implement these measurements.)

The closed form of the PDM that we shall derive employs the Choi-Jamiołkowski (CJ) matrix of the completely positive and trace-preserving (CPTP) map \({{\mathcal{M}}}_{2| 1}\)44,45. An equivalent variant of the definition of the CJ matrix is as follows:

where the superscript T denotes the transpose. We show (see Supplementary Information) that the two-time n-qubit PDM, under coarse-grained measurements, can be written in a surprisingly neat form in terms of M12.

Theorem 1

Consider a system consisting of n qubits with the initial state ρ1. The coarse-grained measurements of Eq. (3) are applied at times t1 and t2. The channel \({{\mathcal{M}}}_{2| 1}\) with CJ matrix M12 is applied in-between the measurements. The n-qubit PDM can then be written as

where \(\rho := {\rho }_{1}\otimes {{\mathbb{1}}}_{2}\).

Theorem 1 extends an earlier known form for the single qubit case to multiple qubits that may have entanglement34,38. The theorem provides an operational meaning for a mathematically motivated spatiotemporal formalism22. Moreover, the n-qubit PDM will enable us to investigate phenomena that cannot be explored in the single qubit case, such as quantum channels with associated extra qubits constituting a memory42.

We next, for completeness, stretch the argument to multiple times. Consider initially an n-qubit state ρ1 measured at time t1, undergoing the channel \({{\mathcal{M}}}_{2| 1}\), measured at time t2, undergoing \({{\mathcal{M}}}_{3| 2}\) and measured at time t3. The central objects to determine are the joint expectation values of the observables at three times. These can be written as

where we denote the CJ matrices for channels \({{\mathcal{M}}}_{2| 1},{{\mathcal{M}}}_{3| 2}\) by M12, M23 respectively, and (see Supplementary Information)

Eqs. (6) and (7) then together imply that

where implicit identity matrices are now omitted for notational convenience.

From Eq. (8), demanding that

gives expectation values consistent with the PDM definition of Eq. (1). Since the expectation values uniquely determine the PDM, Eq. (9) must be the correct expression.

The above derivation can be directly generalised to more than three times:

Theorem 2

The n-qubit PDM across m times is given by the following iterative expression

with the initial condition \({R}_{12}=\frac{1}{2}(\rho \,{M}_{12}+{M}_{12}\,\rho )\) where Mm−1,m denotes the CJ matrix of the (m − 1)-th channel.

This iterative expression, proven in Supplementary Information, can be written in a (possibly long) closed-form sum in a natural manner. We have thus extended a key tool in the PDM formalism from the cases of single qubits, two times or two qubits single time to the case of n qubits at m times for any n and m.

Relation between PDM negativity and the possibility of common cause

PDM negativity (f > 0) was linked to cause-effect mechanisms for the case of one qubit at 2 times or 2 qubits at one time in ref. 12. We now consider the case of several qubits and several times, such that there may be combinations of temporal and spatial correlations. We use Eq. (5) to derive a relation between the negativity of parts of the PDM and the possibility of a common cause, meaning correlations in the initial state.

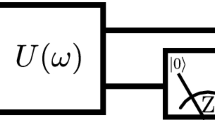

We model the possible directional dynamics of Fig. 1 as so-called semicausal channels46,47. Semicausal channels are those bipartite completely positive trace-preserving (CPTP) maps that do not allow one party to signal or influence the other. If the channel \({\mathcal{P}}\) does not allow B to influence A, it must admit the decomposition \({\mathcal{P}}={{\mathcal{M}}}_{BC}\,{\circ}\; {{\mathcal{N}}}_{AC}\)47. The circuit representation of \({\mathcal{P}}\) on A and B across two times t1, t2, is depicted in Fig. 2. The following theorem shows that when there is no signalling from B at time 1 to A at time 2, the PDM \({R}_{{B}_{1}{A}_{2}}\) has no negativity for any input state.

Semicausal channels are bipartite channels which can be decomposed into either \({{\mathcal{M}}}_{BC}\,{\circ}\; {{\mathcal{N}}}_{AC}\) or \({{\mathcal{N}}}_{AC}\,{\circ}\; {{\mathcal{M}}}_{BC}\) where C is an ancilla, as in the above circuit. The circles here indicate possible measurements. In this example, which is consistent (only) with cases 1, 3 and 5 in Fig. 1, A can causally influence B, while the inverse is not true.

Theorem 3

(null PDM negativity for semicausal channels) If a quantum channel \({\mathcal{P}}\) does not allow signalling from B to A, then, for any state \({\rho }_{{A}_{1}{B}_{1}}\) at time t1, the PDM \({R}_{{B}_{1}{A}_{2}}\) is positive semidefinite and the PDM negativity \(f({R}_{{B}_{1}{A}_{2}})=0\).

The theorem implies that only the existence of causal influence between B and A allows for \(f({R}_{{B}_{1}{A}_{2}}) > 0\). In particular, if there is no causation from B1 to A2, any initial correlations between A1 and B1 cannot make the PDM negativity \(f({R}_{{B}_{1}{A}_{2}}) > 0\). In contrast, several other observation-based measures such as the mutual information can be raised from initial correlations alone48.

Theorem 3 additionally has value for the more restricted task of characterising whether channels are signalling, as considered in refs. 46,47. If \(f({R}_{{B}_{1}{A}_{2}}) > 0\) the channel must be signalling from B to A. In this restricted task, one may vary over input states. There are reasons to believe pure product states may maximise \(f({R}_{{B}_{1}{A}_{2}})\) for a given channel. From property IV of f, with a given R = ∑ipiRi, the most negative pure state \({R}_{i* }:= {\rm{argmax}}\,f({R}_{i})\) respects f(Ri*) ≥ f(R). We moreover conjecture that if the channel is signalling from B to A, we can always find a pure product input state such that \(f({R}_{{B}_{1}{A}_{2}}) > 0\). We prove this conjecture for a quite general case of 2-qubit unitary evolutions49 in Supplementary Information.

Exploiting time asymmetry to distinguish cause and effect

Consider the case where there is negativity f(RAB) > 0, but it is not known which is the cause or effect, i.e. the time-label is unknown. We can then exploit the asymmetry of temporal quantum correlations50 to distinguish the cause and effect, and to determine whether there is a common cause.

The asymmetry of temporal quantum correlations can be defined by comparing forwards and time-reversed PDMs50. The time-reversed PDM,

where S denotes the n-qubit swap operator22,50. The methods given here to find a closed-form expression for RAB can be similarly applied to show that \({\bar{R}}_{AB}=\frac{1}{2}(\pi \,\bar{M}+\bar{M}\,\pi )\), where \(\pi := ({{\rm{Tr}}}_{A}{R}_{AB})\otimes {{\mathbb{1}}}_{A}\) and \(\bar{M}\) is the CJ matrix of the time reversed process. The CJ matrices M and \(\bar{M}\) can be extracted via a vectorisation of R and \(\bar{R}\), respectively50. Let T denote the transpose on the initial quantum system. The Choi matrices of the process and its time reversal are given by MT and \({\bar{M}}^{T}\), respectively. A process being CP is equivalent to its Choi matrix being positive44,45. When only one of the two Choi matrices is positive, we say there is an asymmetry of the temporal quantum correlations.

The asymmetry can be used to distinguish different causal structures. If there is no initial correlation (no common cause) the forwards process is CP but in general the reverse process may be not positive semidefinite (\({\bar{M}}^{T}\) ≱ 0). Furthermore, if both Choi matrices are not positive semidefinite (\({\bar{M}}^{T},{M}^{T}\) ≱ 0), then neither process is CP, and there must be a common cause (initial correlations).

Protocol for quantum causal inference

We will now make use of the results from previous sections to give a protocol that determines the compatibility of the experimental data with the causal structures shown in Fig. 1. In line with causal inference terminology2, we say that the data and a causal structure are compatible if experimental data could have been generated by that structure. As in causal inference in general, compatibility is not guaranteed to be unique.

The causal structures of Fig. 1 are as follows. Case 1 is the cause-effect mechanism in one direction, when there are two instances of quantum systems A and B located in space and actions on A influence the reduced state on B and the actions on B do not influence the reduced state on A. Case 2 is the same mechanism as Case 1 but in the opposite direction. Case 3 is the pure common cause mechanism, with no influence between A and B. There is a common cause, meaning correlations at the initial time t1, iff \({R}_{{A}_{1}{B}_{1}}\ne {R}_{{A}_{1}}\otimes {R}_{{B}_{1}}\). Cases 4 and 5 is when there is a common cause mechanism and also a cause-effect mechanism. Cases 4 and 5 are distinguished by the directionality of the cause-effect mechanism.

Recall that the setting involves two systems A and B and two times ti and tj. We are given the data that constructs the PDM \({R}_{{A}_{i}{B}_{j}}\) and assume that the data has correlations (\({R}_{{A}_{i}{B}_{j}}\ne {R}_{{A}_{i}}\otimes {R}_{{B}_{j}}\) for whatever i, j we are given data for) so that there is a non-trivial causal structure. We are not given the data that constructs the PDM \({R}_{{A}_{i}{B}_{i}{A}_{j}{B}_{j}}\) and do not have enough data to reconstruct the full channel on AB in general. We are, moreover, not told which time is measured first. The protocol is as follows:

-

(1)

Evaluating compatibility with a common-cause mechanism. Consider the case of no negativity (\(f({R}_{{A}_{i}{B}_{j}})=0\)). Theorem 3 implies that only the existence of causal influence between Ai and Bj can allow for negativity. The purely common cause mechanism (case 3 in Fig. 1, \({R}_{{A}_{1}{B}_{1}}\,\ne\, {R}_{{A}_{1}}\otimes {R}_{{B}_{1}}\)) is, in contrast, compatible with no negativity. Thus for no negativity, the protocol is to conclude that the data \({R}_{{A}_{i}{B}_{j}}\) is compatible with the (purely) common cause mechanism.

-

(2)

Evaluating compatibility with different cause-effect mechanisms. Consider the case of negativity (\(f({R}_{{A}_{i}{B}_{j}}) > 0\)). Theorem 3 rules out the common cause mechanism, and we are left to evaluate the compatibility of the data with cases 1, 2, 4, and 5 in Fig. 1. We make use of the time asymmetry results described around Eq. (11) for this evaluation. In particular, we extract the two Choi matrices MT, \({\bar{M}}^{T}\) associated with \({R}_{{A}_{i}{B}_{j}}\) and its time reversal \({\bar{R}}_{{A}_{i}{B}_{j}}\). The basic idea is that MT > 0 means there is a CP map on A that gives B, indicating that A could be the cause and B the effect. More specifically,

-

(3)

If none of the above conditions are satisfied, i.e. f(RAB) > 0, MT ≱ 0 and \({\bar{M}}^{T}\) ≱ 0, the causal structure is compatible only with case 4 or 5 in Fig. 1.

Detailed justifications for the above protocol are given in the Supplementary Information. The Supplementary Information also contains a semidefinite programme motivated by a technical subtlety when extracting the CJ matrix from the PDM. When both ρ and π are of full rank, M and \(\bar{M}\) can be uniquely extracted using the vectorisation technique. However, when they are rank deficient, there are infinitely many solutions for M and \(\bar{M}\). Ref. 51 also showed how solving for the process in the case where the marginal is rank deficient is a semidefinite problem for the case of a single qubit. Therefore, we design a semidefinite programming problem to find all possible CJ matrices where \({M}^{{T}_{1}}\) and \({\bar{M}}^{{T}_{1}}\) are the least negative.

The protocol identifies compatibility, and it is natural to wonder whether it uniquely identifies the structure used to generate the data. For at least part of the protocol this appears to be the case. Numerical simulations of 2-qubit cases show a near unit probability that if \(f({R}_{{A}_{i}{B}_{j}}) > 0\) the data is indeed not generated by the common cause mechanism (see Supplementary Information).

Example: cause-effect mechanism

We now consider an example that shows how our light-touch protocol can resolve the causal structure even for channels that do not preserve quantum coherence. Let systems A and B be uncorrelated single qubit systems, and the end effect of the compound channel \({{\mathcal{M}}}_{BC}\,{\circ}\; {{\mathcal{N}}}_{AC}\) on the compound system AB be the channel that measures the system A, recording the outcome in C and then preparing a state on system B that depends on C, as in Fig. 2. Denote the effective channel on AB by \({{\mathcal{L}}}_{A\to B}={{\rm{Tr}}}_{CA}\,{\circ}\; {{\mathcal{M}}}_{BC}\,{\circ}\; {{\mathcal{N}}}_{AC}\). For concreteness, we choose \({{\mathcal{N}}}_{AC}({\rho }_{A}\otimes {\left\vert 0\right\rangle }_{C}\left\langle 0\right\vert )=\left\langle 0\right\vert {\rho }_{A}\left\vert 0\right\rangle {\left\vert 00\right\rangle }_{AC}\left\langle 00\right\vert +\left\langle 1\right\vert {\rho }_{A}\left\vert 1\right\rangle {\left\vert 11\right\rangle }_{AC}\left\langle 11\right\vert\) and \({{\mathcal{M}}}_{BC}({\rho }_{B}\otimes {\rho }_{C})=S({\rho }_{B}\otimes {\rho }_{C}){S}^{\dagger }\) where S is the unitary swap. Thus the action of \({{\mathcal{L}}}_{A\to B}\) on the state is \({{\mathcal{L}}}_{A\to B}({\rho }_{A})=\left\langle 0\right\vert {\rho }_{A}\left\vert 0\right\rangle {\left\vert 0\right\rangle }_{B}\left\langle 0\right\vert +\left\langle 1\right\vert {\rho }_{A}\left\vert 1\right\rangle {\left\vert 1\right\rangle }_{B}\left\langle 1\right\vert\). Therefore, the CJ matrix of \({\mathcal{L}}\) in the Pauli basis is

Substituting Eq. (12) into Eq. (5), the PDM

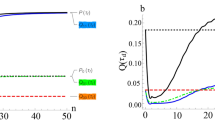

where \(z:= {\rm{Tr}}({\rho }_{{A}_{1}}{\sigma }_{3})\). The eigenvalues of \({\rho }_{{A}_{1}}+\frac{1}{2}{\sigma }_{3}+\frac{z}{2}{\mathbb{1}}\) are \(\frac{1}{2}(1+z\pm \sqrt{{(1+z)}^{2}+{x}^{2}+{y}^{2}})\) with \(x:= {\rm{Tr}}({\rho }_{{A}_{1}}{\sigma }_{1}),y:= {\rm{Tr}}({\rho }_{{A}_{1}}{\sigma }_{2})\). When x2 + y2 = 0, the PDM is positive (\(f({R}_{{A}_{1}{B}_{2}})=0\)) without coherence in the Pauli-z basis. However, the PDM is negative (\(f({R}_{{A}_{1}{B}_{2}}) > 0\)) exactly when x2 + y2 > 0, i.e. when the initial state \({\rho }_{{A}_{1}}\) is coherent in the Pauli-z basis.

For concreteness, we now assume the initial state is given by \({\rho }_{{A}_{1}{B}_{1}}=\left[(1-\lambda )\frac{{\mathbb{1}}}{2}+\lambda \left\vert +\right\rangle \left\langle +\right\vert \right]\otimes \left\vert 0\right\rangle \left\langle 0\right\vert ,\lambda \in (0,1).\) The Choi matrix of the time reversal process (Eq. (11)) can be calculated to be

Clearly, LT ≥ 0 and \({\bar{L}}^{T}\) ≱ 0 for any λ ∈ (0, 1).

Applying the causal inference to the above case we would firstly note \(f({R}_{{A}_{1}{B}_{2}}) > 0\) so case 3 is ruled out. Since LT ≥ 0 and \({\bar{L}}^{T}\) ≱ 0, the data is compatible with A → B (case 1 in Fig. 1).

The example has implications for when the apparent quantum advantage of not requiring interventions for causal inference exists. An earlier observational protocol25 showed this advantage existing for a case of coherence- preserving channels. The above example using our observational protocol indicates that coherence-preserving channels is not required for this apparent quantum advantage. In the above example, there is coherence in the initial state but a decoherent channel. A further example of applying the protocol to a cause-effect mechanism with a common cause is given in the Supplementary Information.

Discussion

The results naturally point towards several developments: (i) Our closed-form PDM may enable Leggett-Garg type inequalities, which concern 3 or more times9,52, to be extended to non-trivial evolutions; (ii) The causal inference protocol may be generalisable to networks of multiple times and parties using the closed form; (iii) The causality monotone might be possible to witness via observables, c.f.53; (iv) Other formalisms based around the CJ isomorphism could likely be employed analogously, and may offer alternative tools and perspectives10,16,18,19,25,54; (v) Our scheme can be used to determine classical causal structures without interventions provided that these can be probed in quantum superposition, e.g. as in the case of typical optical table equipment; (vi) Why are such light-touch interventions sufficient for quantum causal inference? (vii) The protocol could be strengthened to distinguish between causal mechanisms 4 and 5 for the special case when there is negativity both in the PDM, the CJ matrix and the time-reversed CJ matrix; (viii) An important open question is whether the approach can be generalised to other measurement schemes.

Methods

Coarse-grained measurement underlying closed-form PDM

Let us take a two-qubit system to illustrate our design of measurement events. At initial time t1, we implement the observable \({\sigma }_{i}^{A}\otimes {\sigma }_{j}^{B}\). This observable can be decomposed into linear combinations of projectors in several ways. For example,

where

are the elements of the projective measurement. The observable can also be decomposed in terms of the Bell basis:

where

are elements of the Bell measurement with U being any unitary satisfying \(U\left({\sigma }_{1}\otimes {\sigma }_{1}\right){U}^{\dagger }={\sigma }_{i}\otimes {\sigma }_{j}.\)

One can show

and

We shall define the PDM in terms of the corresponding coarse-grained measurement

One possible way to implement the coarse-grained measurements, inspired by55 is provided in the Supplementary Information.

Note added

The above quantum causal inference protocol has, after the preparation of this manuscript, been implemented experimentally in an NMR platform56,57.

Data availability

No data were generated in this research apart from that presented in the paper.

Code availability

Codes are available upon request to the authors.

References

Reichenbach, H. The Direction of Time Vol. 65 (Univ. California Press, 1956).

Pearl, J. Causality (Cambridge Univ. Press, 2009).

Balke, A. & Pearl, J. Bounds on treatment effects from studies with imperfect compliance. J. Am. Stat. Assoc. 92, 1171–1176 (1997).

Prosperi, M. et al. Causal inference and counterfactual prediction in machine learning for actionable healthcare. Nat. Mach. Intell. 2, 369–375 (2020).

Peters, J., Janzing, D. & Schölkopf, B. Elements of Causal Inference: Foundations and Learning Algorithms (MIT Press, 2017).

Feder, A. et al. Causal inference in natural language processing: estimation, prediction, interpretation and beyond. Trans. Assoc. Comput. Linguist. 10, 1138–1158 (2022).

Angrist, J. D., Imbens, G. W. & Rubin, D. B. Identification of causal effects using instrumental variables. J. Am. Stat. Assoc. 91, 444–455 (1996).

Greenland, S. An introduction to instrumental variables for epidemiologists. Int. J. Epidemiol. 29, 722–729 (2000).

Leggett, A. J. & Garg, A. Quantum mechanics versus macroscopic realism: Is the flux there when nobody looks? Phys. Rev. Lett. 54, 857 (1985).

Oreshkov, O., Costa, F. & Brukner, Č. Quantum correlations with no causal order. Nat. Commun. 3, 1–8 (2012).

Brukner, Č. Quantum causality. Nat. Phys. 10, 259–263 (2014).

Fitzsimons, J. F., Jones, J. A. & Vedral, V. Quantum correlations which imply causation. Sci. Rep. 5, 18281 (2016).

Barrett, J., Lorenz, R. & Oreshkov, O. Cyclic quantum causal models. Nat. Commun. 12, 1–15 (2021).

Barrett, J., Lorenz, R. & Oreshkov, O. Quantum causal models. Preprint at arXiv:1906.10726 (2019).

Hardy, L. Probability theories with dynamic causal structure: a new framework for quantum gravity. Preprint at arXiv:gr-qc/0509120 (2005).

Chiribella, G., D’Ariano, G. M. & Perinotti, P. Theoretical framework for quantum networks. Phys. Rev. A 80, 022339 (2009).

Milz, S., Bavaresco, J. & Chiribella, G. Resource theory of causal connection. Quantum 6, 788 (2022).

Costa, F. & Shrapnel, S. Quantum causal modelling. N. J. Phys. 18, 063032 (2016).

Allen, J.-M. A., Barrett, J., Horsman, D. C., Lee, C. M. & Spekkens, R. W. Quantum common causes and quantum causal models. Phys. Rev. X 7, 031021 (2017).

Aharonov, Y., Popescu, S., Tollaksen, J. & Vaidman, L. Multiple-time states and multiple-time measurements in quantum mechanics. Phys. Rev. A 79, 052110 (2009).

Liu, X., Ebler, D. & Dahlsten, O. Thermodynamics of quantum switch information capacity activation. Phys. Rev. Lett. 129, 230604 (2022).

Parzygnat, A. J. & Fullwood, J. From time-reversal symmetry to quantum bayes’ rules. PRX Quantum 4, 020334 (2023).

Wolfe, E. et al. Quantum inflation: a general approach to quantum causal compatibility. Phys. Rev. X 11, 021043 (2021).

Wolfe, E., Schmid, D., Sainz, A. B., Kunjwal, R. & Spekkens, R. W. Quantifying bell: the resource theory of nonclassicality of common-cause boxes. Quantum 4, 280 (2020).

Ried, K. et al. A quantum advantage for inferring causal structure. Nat. Phys. 11, 414–420 (2015).

Bai, G., Wu, Y.-D., Zhu, Y., Hayashi, M. & Chiribella, G. Quantum causal unravelling. npj Quantum Inf. 8, 69 (2022).

Chiribella, G. & Ebler, D. Quantum speedup in the identification of cause–effect relations. Nat. Commun. 10, 1–8 (2019).

MacLean, J.-P. W., Ried, K., Spekkens, R. W. & Resch, K. J. Quantum-coherent mixtures of causal relations. Nat. Commun. 8, 1–10 (2017).

Chaves, R. et al. Quantum violation of an instrumental test. Nat. Phys. 14, 291–296 (2018).

Agresti, I. et al. Experimental test of quantum causal influences. Sci. Adv. 8, eabm1515 (2022).

Gachechiladze, M., Miklin, N. & Chaves, R. Quantifying causal influences in the presence of a quantum common cause. Phys. Rev. Lett. 125, 230401 (2020).

Nery, R., Taddei, M., Chaves, R. & Aolita, L. Quantum steering beyond instrumental causal networks. Phys. Rev. Lett. 120, 140408 (2018).

Agresti, I. et al. Experimental device-independent certified randomness generation with an instrumental causal structure. Commun. Phys. 3, 1–7 (2020).

Horsman, D., Heunen, C., Pusey, M. F., Barrett, J. & Spekkens, R. W. Can a quantum state over time resemble a quantum state at a single time? Proc. R. Soc. A Math. Phys. Eng. Sci. 473, 20170395 (2017).

Fullwood, J. & Parzygnat, A. J. On quantum states over time. Proc. R. Soc. A 478, 20220104 (2022).

Jia, Z., Song, M. & Kaszlikowski, D. Quantum space-time marginal problem: global causal structure from local causal information. New J. Phys. 25, 123038 (2023).

Marletto, C. et al. Temporal teleportation with pseudo-density operators: How dynamics emerges from temporal entanglement. Sci. Adv. 7, eabe4742 (2021).

Zhao, Z. et al. Geometry of quantum correlations in space-time. Phys. Rev. A 98, 052312 (2018).

Marletto, C. et al. Theoretical description and experimental simulation of quantum entanglement near open time-like curves via pseudo-density operators. Nat. Commun. 10, 1–7 (2019).

Zhang, T., Dahlsten, O. & Vedral, V. Different instances of time as different quantum modes: quantum states across space-time for continuous variables. N. J. Phys. 22, 023029 (2020).

Zhang, T., Dahlsten, O. & Vedral, V. Quantum correlations in time. Preprint at arXiv:2002.10448 (2020).

Pisarczyk, R., Zhao, Z., Ouyang, Y., Vedral, V. & Fitzsimons, J. F. Causal limit on quantum communication. Phys. Rev. Lett. 123, 150502 (2019).

Vidal, G. Entanglement monotones. J. Mod. Opt. 47, 355–376 (2000).

Choi, M.-D. Completely positive linear maps on complex matrices. Linear Algebra Appl. 10, 285–290 (1975).

Jamiołkowski, A. Linear transformations which preserve trace and positive semidefiniteness of operators. Rep. Math. Phys. 3, 275–278 (1972).

Beckman, D., Gottesman, D., Nielsen, M. A. & Preskill, J. Causal and localizable quantum operations. Phys. Rev. A 64, 052309 (2001).

Eggeling, T., Schlingemann, D. & Werner, R. F. Semicausal operations are semilocalizable. Europhys. Lett. 57, 782 (2002).

Janzing, D., Balduzzi, D., Grosse-Wentrup, M. & Schölkopf, B. Quantifying causal influences. Ann. Stat. 41, 2324–2358 (2013).

Kraus, B. & Cirac, J. I. Optimal creation of entanglement using a two-qubit gate. Phys. Rev. A 63, 062309 (2001).

Liu, X., Chen, Q. & Dahlsten, O. Inferring the arrow of time in quantum spatiotemporal correlations. Phys. Rev. A 109, 032219 (2024).

Song, M., Narasimhachar, V., Regula, B., Elliott, T. J. & Gu, M. Causal classification of spatiotemporal quantum correlations. Phys. Rev. Lett. 133, 110202 (2024).

Vitagliano, G. & Budroni, C. Leggett-Garg macrorealism and temporal correlations. Phys. Rev. A 107, 040101 (2023).

Araújo, M. et al. Witnessing causal nonseparability. N. J. Phys. 17, 102001 (2015).

Liu, X., Jia, Z., Qiu, Y., Li, F. & Dahlsten, O. Unification of spatiotemporal quantum formalisms: mapping between process and pseudo-density matrices via multiple-time states. N. J. Phys. 26, 033008 (2024).

Souza, A., Oliveira, I. & Sarthour, R. A scattering quantum circuit for measuring Bell's time inequality: a nuclear magnetic resonance demonstration using maximally mixed states. New J. Phys. 13, 053023 (2011).

Liu, H. et al. Experimental demonstration of quantum causal inference via noninvasive measurements. Preprint at arXiv:2411.06051 (2024).

Liu, H. et al. Quantum causal inference via scattering circuits in NMR. Preprint at arXiv:2411.06052 (2024).

Acknowledgements

We thank Dong Yang, Daniel Ebler, Qian Chen, Caslav Brukner, Giulio Chiribella and James Fullwood for the discussions. X.L. and O.D. acknowledge support from the NSFC (Grants No. 12050410246, No. 1200509, No. 12050410245) and the City University of Hong Kong (Project No. 9610623). Part of this work was carried out when X.L. was visiting the City University of Hong Kong. X.L. also acknowledge support from the National Research Foundation, Prime Minister’s Office, Singapore, under its Campus for Research Excellence and Technological Enterprise (CREATE) programme. Y.Q. is supported by the NRF, Singapore and A*STAR. This publication was made possible in part through the support of the ID 61466 grant from the John Templeton Foundation, as part of the The Quantum Information Structure of Spacetime (QISS) Project (qiss.fr). The opinions expressed in this publication are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the views of the John Templeton Foundation. This research is also funded in part by the Gordon and Betty Moore Foundation through Grant GBMF10604 to V.V. Open Access made possible with partial support from the Open Access Publishing Fund of the City University of Hong Kong.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

X.L. conceived the idea and derived the main results. All authors contributed to discussions throughout and the development of the results. X.L. and O.D. wrote the manuscript with inputs from all authors. O.D. supervised the project.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Liu, X., Qiu, Y., Dahlsten, O. et al. Quantum causal inference with extremely light touch. npj Quantum Inf 11, 54 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41534-024-00956-0

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41534-024-00956-0