Abstract

We develop and analyze a fault-tolerant quantum algorithm for non-linear response properties of molecular and condensed phase systems. We consider a semi-classical description in which the electronic degrees of freedom are treated quantum mechanically and the light is treated as a classical field interacting via the electric dipole approximation. We use the technique of eigenstate filtering, to efficiently resolve excitation energies for dominant dipole transitions. When applied to the electronic structure Hamiltonian with double factorized representation, each significant spectral line can be approximated to a width of ±γ, and to a height of ±ϵ with \(O\left({N}^{6}{\eta }^{2}{\gamma }^{-1}{\epsilon }^{-1}\log (1/\epsilon )\right)\) queries to the block encoding of the unperturbed electronic structure Hamiltonian for η electrons over N basis functions. These quantities can be used to compute the nth order response functions for non-linear spectroscopies under limited assumptions using \(\widetilde{O}\left({N}^{5n+1}{\eta }^{n+1}/{\gamma }^{n}\epsilon \right)\) queries to the block encoding of the Hamiltonian.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

A large focus of quantum algorithms has been on the determination of ground state properties of a given Hamiltonian, with a much smaller effort on extracting excited state properties1,2,3,4,5,6. While accurate estimation of ground state properties of quantum many-body systems is already difficult, excited state properties are often more challenging to calculate, because interior eigenvectors and eigenvalues must be resolved without a direct variational analog, since they are not the extremal eigenvalues of the Hamiltonian describing the system. Classical approaches to solve this problem are often expressed using the generalized variational principle, that target specific excited states7,8,9. While there exist efficient classical algorithms for approximating the vibronic spectra of molecules10, classical algorithms for electronic spectroscopy in general suffer from exponential scaling.

On the other hand, understanding non-ground state properties such as transition dipole moments and energy gaps allows better predictions of material properties, and is essential for predicting and analyzing spectroscopic features deriving from light–matter interactions. In this work, we present a quantum algorithm that can be used to accurately compute excited state properties deriving from the interaction of a many-electron system with photons in the semi-classical description, given access to efficient ground state preparation. In the weak field regime and in the electric dipole approximation, we obtain ab initio estimates of the transition dipole moments corresponding to electronic state transition probabilities, as well as their associated excitation energies. This allows efficient construction of nth order susceptibilities and hence efficient ab initio calculation of non-linear spectroscopic responses. We focus here specifically on the case of molecular spectroscopy, but our results can be applied more generally to any many-body fermionic system and its non-linear response to interaction with a classical light field.

The main contribution of this work is the development and analysis of an algorithm for computing ab initio transition dipole moments and excitation energies. This algorithm allows the determination of frequency-dependent properties of the response function by using a simple excite-and-filter approach where we first apply the dipole operator and then filter the response to eigenenergies within a particular frequency bin. By using quantum signal processing11 in conjunction with a modified binary search procedure, our algorithm achieves Heisenberg limited scaling12 for determination of excitation energies. With respect to the spectral resolution parameter γ, we expect our algorithm to be near optimal for the computation of frequency-dependent response properties in the semi-classical regime. Our proposed algorithm has the additional benefit that the core subroutine can be iteratively repeated to compute response functions of any order. As far as we are aware, this is the first work to provide concrete resource estimations for the general problem of estimating linear and nonlinear response functions of arbitrary order.

We focus on estimating transition strengths at specific excitation energies by implementing the transition dipole operator directly on a prepared ground state and filtering the response on a particular energy window. By repeatedly measuring a constant number of additional ancilla qubits, we can obtain systematically improvable estimates to transition dipole moments within this window. After obtaining the relevant transition dipole moments and energies, one can then post-process this data on a classical computer to extract interesting quantities such as oscillator strengths13 and compute the desired response functions.

The structure of this paper is as follows. In Section “Results” we present the algorithm and show the worst-case asymptotic costs to implement the algorithm for first-order polarizabilities. We then show how the algorithm can be iteratively applied to find calculate response functions of arbitrary order. In III we compare our results with other proposed quantum algorithms for the computation of polarizability of linear response functions, before concluding and giving an outlook for future work. In Section “Methods”, we introduce the molecular electronic structure Hamiltonian in second quantization, followed by an overview of relevant aspects of electronic spectroscopy within the semi-classical treatment of electron–light interactions and under the electronic dipole approximation. We then briefly discuss the primary quantum subroutines that we use in the main algorithm of this work.

Results

In this section, we present a quantum algorithm for computing the response and electronic absorption spectrum of a molecular system. The focus of our algorithm is in obtaining estimates of the induced dipole moments since these values give a direct way to compute absorption probabilities as described in the previous section. We desire to compute the response function by exploiting the sum-over-states form of the polarizability given by Eq. (54). This requires finding the relevant overlaps corresponding to particular ground-to-excited state transitions. In this section, we will use the convention Di to refer to the matrix representation of the dipole operator in direction i to differentiate from its matrix elements \({d}_{i,(nm)}=\left\langle {\psi }_{m}\right\vert {D}^{i}\left\vert {\psi }_{n}\right\rangle\). D without indices refers to arbitrary dipole operator. The terms in the sum-over-states form require approximations to terms of the form

and is non-zero whenever the transition 0 → n is allowed by symmetry, commonly referred to as a selection rule.

The algorithm is based off of a simple observation, given access to an eigenstate, say the ground state, \(\left\vert {\psi }_{0}\right\rangle\) of the electronic Hamiltonian H0, and a block-encoding of a potential, such as the dipole operator, we can use Fermi’s rule to approximate transition rates and strengths on the quantum computer. An algorithm implementing this procedure can be realized with a generalized Hadamard test, and uses only one ancilla qubit beyond those used for the block-encoding.

In the case of the second quantized chemistry Hamiltonian, we assume that spin-orbitals are mapped to qubits in a one-to-one fashion on a quantum computer using the Jordan-Wigner transformation in this work. In the Jordan–Wigner transform n = N where each of n qubits are mapped to one of the N spin–orbitals in a second quantized representation. We will use [a, b] to refer to a window of excitation frequencies over which we will approximate the response on and Δ: = b − a as width of the interval over which we wish to estimate the response. In this section, we will show how one can obtain systematically improvable approximations to frequency-dependent nth-order response properties. Combining these approximations, we obtain an approximation to the molecular response to the perturbing electric field over the total length of a spectral region of interest.

Additionally, we define the indicator function

To understand how this transformation produces the desired output, we will assume that we are able to exactly implement the indicator function of our matrix 1[a, b](H0). In the later sections, we analyze the scaling of the polynomial for a desired error tolerance. When applied to a matrix, the indicator function serves as a projection onto the subspace of H0 spanned by eigenvalues in [a, b]. By this we mean,

where \({\sum }_{{\lambda }_{j}\in [a,b]}\equiv {\sum }_{j:{\lambda }_{j}\in [a,b]}\) and where we have written H0 as its eigendecomposition

Let \(\left\vert {\psi }_{0}\right\rangle\) be the exact ground state of H0 and consider the dipole operators D and \({D}^{{\prime} }\). Before we make precise the statement of our algorithm, consider the following sequence of operations

then, if we could compute the inner product of that state with the ground state \(\left\vert {\psi }_{0}\right\rangle\), we would find obtain the desired terms

For [a, b] small enough so that ∣b − a∣ < γ, the parameter controlling the desired spectral resolution, we can faithfully approximate the response by summing over the approximations we find on each small interval of size o(γ). If [a, b] contains only one excitation, then this approximation would be exact up to sampling errors, and the only uncertainty is the position in the window where the excitation occurred. In the next section we present an algorithm that can improve this resolution at the Heisenberg limit. We introduce the following definitions, let

then since the polarizability

we can write an approximation to this sum in terms of the approximations for each sub-interval [a, b] estimating ωn0 by the central frequency of [a, b], \({\widetilde{\omega }}_{a,b}\equiv | b-a| /2\)

with ∪ i[ai, bi] ⊂ [−α, α]. In the next section we construct a quantum algorithm to obtain estimates to the factors \({d}_{[a,b]}^{x,{x}^{{\prime} }}\) which we can then use in conjunction with Eq. (8) to obtain an approximation to (7).

Full algorithm and cost estimate

Our algorithm will rely on block-encodings of the Hamiltonian H0 and dipole operators D and \({D}^{{\prime} }\), which will be accessed through their (α, m, 0) and (β, k, 0) block-encodings UH and \({U}_{D},{U}_{{D}^{{\prime} }}\) respectively. We will additionally need access to a high-precision approximation to the ground state. This assumption can be made more precise by first assuming that the initial state \(\vert \psi \rangle\) has been prepared with squared overlap \({p}_{0}={\left\vert \langle {\psi }_{0}| \psi \rangle \right\vert }^{2}\) and that the spectral gap G = λ1 − λ0, with neither being exponentially small. Under these assumptions, the eigenstate filtering method proposed in14,15, constructs an algorithm which can prepare the ground state with \(O\left(\frac{\alpha }{\sqrt{{p}_{0}}G}\log (1/\epsilon )\right)\) queries to UH.

Given these constraints, we can apply this algorithm to efficiently transform some good initial state \(\vert \psi \rangle\) into a high fidelity approximation of the true ground state \(\vert {\psi }_{0}\rangle\). Once the high fidelity ground state is in hand, we can additionally use eigenstate filtering to obtain a high-fidelity estimate to the ground energy as well. Although the assumption of having an exact ground state is unlikely to be achieved in practice, this algorithm allows us to transform our initial state with 1/poly(n) overlap, to a state with arbitrarily close-to-1 overlap with the true ground state. We consider this to be a preprocessing step, and we assume for the duration of this work access to exact ground state preparation.

To motivate the construction, consider the operation \({\mathcal{U}}\), which we define as the product of block-encodings,

Forming the linear combination \(\frac{1}{2}({\mathcal{U}}+I)\) implements the Hadamard test for non-unitary matrices and when applied to the ground state \(\vert {\psi }_{0}\rangle\), we observe that the success probability of measuring the ancilla qubit to be \(\left\vert 0\right\rangle\) in the LCU is

which can be simplified to

where

is the subnormalization factor for this block encoding. In the following section, we bound the cost of performing these operations and the number of repetitions needed to obtain accurate approximations to the response with energies resolved to the desired spectral resolution o(γ) in terms of these parameters.

Block-encoding H 0 and dipole operators

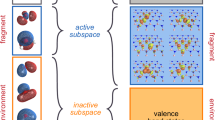

Our algorithm relies on access to block-encodings of the dipole operators, which we denote D and \({D}^{{\prime} }\), and H0. We bound the cost to implement these operations and show that it is subdominant to the cost of block-encoding H0. Block-encoding the electronic structure Hamiltonian has been discussed in great detail in the literature16,17, so we will not explicitly analyze the block-encoding gate complexity for H0. We do however, wish to obtain a bound to the number of queries to UH in terms of the number of spin–orbitals N and the number of electrons η. The naive bound on the subnormalization for UH would be O(N4) due to the O(N4) terms in the Coulomb Hamiltonian. However, this bound can be quite pessimistic in practice, and more efficient techniques such as double factorization17,18,19 or the method of tensor hypercontraction16 can reduce the number number of gates to O(N) in some cases. In the low-rank double-factorization based approach, empirical results have shown that the number of terms in H0 can be reduced to O(N2) while maintaining the desired accuracy (c.f.19,20 Supporting Information Section VII.C.5).

One approach to block-encoding the dipole operator D is to start from its second quantizated representation. We can use the Jordan–Wigner transformation to write D as a linear combination of Pauli matrices

with Pj ∈ {I, X, Y, Z}⊗N. From this we immediately obtain a representation of D as linear combination of O(N2) unitary matrices. Accordingly, the dipole operator can be block-encoded using \(k=\left\lceil \log ({N}^{2})\left.\right)\right\rceil\) ancilla qubits and O(N2) controlled Pauli operators. The subnormalization factor β is the 1 − norm of the coefficients in this decomposition and is therefore

We assume each of the coefficients in the LCU is a constant with respect to the number of basis functions N, thus β ∈ O(N2).

An alternative approach to block-encoding the single particle Fermionic operator is to use a single-particle basis transformation U17 to represent the creation and annihilation operators in the single-particle basis that makes D diagonal. That is

where the eigendecomposition of d = u ⋅ diag [λ0, ⋯ , λN−1] ⋅ u†. This immediately leads to a block-encoding of the dipole operator with β = N∣∣d∣∣, where \(| | d| | =\mathop{\max }\limits_{j}| {\lambda }_{j}|\). However, applying the result of ref. 21 Appendix J, this can be further improved. Let \(\vec{| \lambda | }\) sort the λj in magnitude from largest to smallest. Then

Importantly, any single-particle rotation can be implemented using only \({\mathcal{O}}({N}^{2})\) quantum gates.

When the block-encoding of the dipole operator is applied to the molecular ground state, the state of the quantum computer is,

Upon measurement of the ancilla register returning the all-zero state, we have knowledge that the state of the system register must have been

Where we have dropped the k-qubit ancillary register used in the block-encoding since we have assumed that register has been uncomputed and measured in the \({\left\vert 0\right\rangle }_{k}\) state.

At this stage of the algorithm we have prepared a superposition of excited states with amplitudes proportional to the probability of the respective ground to excited state transition. In the next step we show how to extract response properties at particular energies using an eigenstate filtering strategy.

Block-encoding the indicator function

The indicator function can be implemented using a suitable polynomial approximation and quantum signal processing of the block-encoding matrix UH. We invite the interested reader to view the Supplementary Materials for additional details on the construction of the indicator function, as well as concrete error analysis of its implementation. In the context of quantum algorithms, the indicator function was has been used as part of the eigenstate filtering subroutine explored in ref. 15, which constructs a polynomial approximation to the Heaviside step function smoothed by a mollifier. Other work such as refs. 22,23, provides an improvement to ref. 15 by a factor of \(O(\log (\delta ))\) using a polynomial approximation to the error function \({\rm{erf}}(kx)\). This factor is non-trivial, as in many cases the subnormalization factor rescales δ ∈ O(1) to δ/α ∈ O(1/α). Lemma 29 of ref. 22 promises the existence of a polynomial approximation to the symmetric indicator function that can be constructed using a \(d=O({\delta }^{-1}\log ({\epsilon }^{-1}))\) degree polynomial where δ ∈ (0, 1/2). Furthermore, there exist robust software implementations for computing the phase factors for window functions, provided for example in QSPPACK24,25.

We would like to block encode the indicator function over the symmetric interval \(\left[\omega -\Delta /2,\omega +\Delta /2\right]\). This corresponds to choosing some fixed central frequency ω and forming the interval of width Δ. One straightforward way to implement the shift is to simply perform an LCU of the original Hamiltonian with the identity matrix of the same dimension. Since we would like to study the excitation energies, we will assume that we have shifted the Hamiltonian so that λ0 = 0. We would like to implement the linear combination H0 − ωI for some ω > 0. We can construct a block-encoding of the shifted Hamiltonian with an additional qubit as in Fig. 1.

The prepare oracle can be implemented by the rotation \({R}_{y}(\theta )\left\vert 0\right\rangle =\cos (\theta /2)\left\vert 0\right\rangle +\sin (\theta /2)\left\vert 1\right\rangle\) and \(\theta =2\arccos \left({\left(1+{\omega }^{2}\right)}^{-1/2}\right)\), so that \({R}_{y}(\theta )\left\vert 0\right\rangle =\frac{1}{\sqrt{1+{\omega }^{2}}}\left(\left\vert 0\right\rangle +\omega \left\vert 1\right\rangle \right)\).

We use the notation \({\widetilde{1}}_{[a,b]}\) to refer to the approximated indicator function on some interval [a, b]. That is, given access to an (α, m, 0) block-encoding of H0, we can construct an (α + ω, m + 1, 0) block-encoding of H0 − ωI. Using QSP in conjunction with a degree d polynomial we can then form an (α + ω, m + 2, ϵ) block-encoding of \({\widetilde{1}}_{[\omega -\Delta ,\omega +\Delta ]}({H}_{0})\).

The next step of the algorithm is to apply another dipole operator to the state following the application of the filtering function, this step follows the same procedure as the block-encoding of the dipole operator we performed previously. In the following section, we apply these steps in a controlled fashion using a small number of additional ancilla qubits in conjunction with the non-unitary Hadamard test to estimate the desired terms.

Non-unitary Hadamard test

In order to obtain the terms relevant to computing response functions in the sum-over-states form, we need to compute the inner products \({d}_{[a,b]}^{x,{x}^{{\prime} }}=\left\langle {\psi }_{0}\right\vert {D}^{{\prime} }{1}_{[a,b]}({H}_{0})D\left\vert {\psi }_{0}\right\rangle\). The standard way to estimate inner products of unitary matrices on a quantum computer is the Hadamard test. Using the same circuit, but instead replacing the unitary matrix with a block-encoding renders an algorithm for estimating inner products of non-unitary matrices. This idea has been explored previously, and an implementation of this algorithm can be found in appendix D of ref. 21.

For clarity, in this section we assume access to the operations above and that the indicator function is approximated well enough that we can ignore the error introduced by the approximation error. We will analyze the effect of this approximation on the desired expectation values in the following section. We define the map \({\mathcal{U}}\) according to its action on the ground state and ancilla registers used in the block-encoding as

Where we recall that m, k, and \({k}^{{\prime} }\) are the ancilla qubits used for block encoding H0D and \({D}^{{\prime} }\) respectively. Now, we apply \({\mathcal{U}}\) in a controlled manner with an additional ancilla qubit using the Hadamard test circuit. Measuring this ancilla register returns the \(\left\vert 0\right\rangle\) state with probability:

It is easy to show that \(\left\langle {\psi }_{0}\right\vert {D}^{{\prime} }{1}_{[a,b]}({H}_{0})D\left\vert {\psi }_{0}\right\rangle\) gives the desired overlaps

We can see that \({\mathcal{U}}\) corresponds to a product of the block-encodings we formed in the previous section, therefore it can be realized via the \(({\zeta }_{\omega },m+2+k+{k}^{{\prime} },0)\) block-encoding formed by the product of block-encoded matrices22. One should note that in the case where \({D}^{{\prime} }=D\), one can instead do the Hadamard test on only the indicator function to approximate the inner product \(\left\langle {\psi }_{0}\right\vert {D}^{\dagger }{1}_{[a,b]}({H}_{0})D\left\vert {\psi }_{0}\right\rangle\). This gives an improvement by a factor of O(β) in the query complexity over the off-diagonal case.

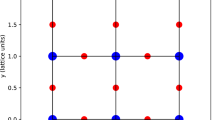

This introduces the main procedure for calculating the terms in the sum-over-states representation of response functions and a graphical representation of this procedure is provided in Fig. 2. In the next section, we show how to systematically improve the resolution by reducing the size of the window [a, b] and determine the response in bins to high resolution. Additionally, we show how these subroutines can be iteratively applied to efficiently approximate response functions to any order.

The x-axis is the frequency, ω(λ) = λ − λ0, the y-axis the measured response. The goal is to approximate the response in the window [a, b], by forming the indicator function 1[a, b] over the portion of the [ω(a), ω(b)] using the the block-encoding of H0 and QSP. The smooth line in black is the damped response function given by a Lorentzian broadening parameter γ, the red sticks are the oscillator strengths associated with particular transitions. We approximate the response by convolving the smoothed indicator function (in blue) with the signal (in red) to estimate the strength of the response over the region indicated a and b. The region denoted δ corresponds to the smoothing parameter used in approximating the indicator function. Using this approach over different regions with smaller and smaller windows, we obtain a systematically improvable estimate of the transition strength associated with a particular transition energy window, as shown in the inset.

Approximating first-order polarizability tensor

Although we have a quantum state whose amplitudes correspond to the dipole transition amplitudes in a particular window, we would like to use these estimates to compute response functions. The properties of the transition dipole will affect the difficulty of this task. In the most pessimistic case, the dipole prepares a near uniform superposition over the exponentially large set of excited states. In this case it can be very inefficient to extract high precision estimates of spectrally localized properties of the response function, as each amplitude is exponentially suppressed leading to small success probabilities. However, this behavior is unlikely for many systems of interest as it would imply that electronic transitions are nearly equiprobable for every incident frequency ω. Therefore, in practice we expect some concentration of the response function to relatively small portions of the spectrum similar to the schematic in Fig. 2. Our goal in this section is to determine the locations of most prominent dipole responses over the energy spectrum.

The algorithm in the above section provides a procedure for approximating the dipole response in the region [a, b] to compute \({d}_{[a,b]}^{x,{x}^{{\prime} }}\) and \({d}_{[a,b]}^{{x}^{{\prime} },x}\) and provides an approximate excitation energy for those responses as the center of the window \({\widetilde{\omega }}_{a,b}=| b-a| /2\). To approximate response functions such as the linear polarizability, we need to approximate all of the non-zero terms in the sum-over-states formalism. An inspection of this definition of the polarizability reveals that terms with large dipole response will dominate the behavior of the function.

These terms need to be evaluated to high precision and the window [a, b] that we use to approximate this quantity needs to be smaller than some desired spectral resolution γ. For fixed γ, in order to adequately resolve the response function requires the window [a, b] to satisfy Δ ≡ ∣b − a∣ < γ. Since by definition δ < Δ < γ, and the subnormalization α rescales this interval, this immediately implies that δ = o(α−1) so that the degree of polynomial needed is \(\widetilde{O}(\alpha )\). This increases the number of queries to UH by an additional factor of \(\widetilde{O}(\alpha )\). Therefore it is prudent to postpone this cost until it is absolutely necessary. To more rapidly approximate the frequency dependent response, we first introduce an algorithm to determine more pronounced regions in the response and resolve them to higher precision. This algorithm, which uses ideas based on a modified binary search similar to that found in ref. 15, can be implemented as a linear combination of Hadamard tests.

For simplicity, assume that the Hamiltonian has already been rescaled so that its spectrum lies in [−1, 1]. Take B, ∣B∣ ∈ O(1) to be a set of bins and for each bi ∈ B, \({b}_{i}=\left[-1+\frac{2i}{| B| },-1+\frac{2(i+1)}{| B| }\right]\). The problem then becomes determining which bins have the largest response. Since our goal at this stage is not to approximate \({d}_{{b}_{i}}^{x,{x}^{{\prime} }}\) for each bi, but instead to determine inequalities between the \({d}_{{b}_{i}}^{x,{x}^{{\prime} }}\)’s, the number of samples can be greatly decreased. Since the determination of the inequality \({d}_{{b}_{i}}^{x,{x}^{{\prime} }} > {d}_{{b}_{j}}^{x,{x}^{{\prime} }}\) is made by sampling, we only need to ensure this inequality holds with some probability. A depiction of how this might look for the first iteration is provided in Fig. 3. The number of samples Ns needed to determine that \({d}_{{b}_{i}}^{x,{x}^{{\prime} }} > {d}_{{b}_{j}}^{x,{x}^{{\prime} }}\) probabilistically is only \(\widetilde{O}(1)\) as a result of a Chernoff bound (see Lemma 3 of the Supplementary Materials for additional details).

Define \({{\mathcal{U}}}_{{b}_{i}}={U}_{{D}^{{\prime} }}{U}_{{1}_{{b}_{i}}}({H}_{0}){U}_{D}\), which is the product of block encodings needed to approximate the average response on the region bi. For each of the \({{\mathcal{U}}}_{{b}_{i}}\) we will append an additional ancilla qubit so that we can form the LCU \(\frac{1}{2}({{\mathcal{U}}}_{{b}_{i}}+I)=:{{\mathcal{U}}}_{i}\). Next we add an ancilla register of \(r=\log (| B| )\) qubits and apply the diffusion operator on the ancilla register over ∣B∣ states. Then, we apply each of the \({{\mathcal{U}}}_{i}\) to the ground state controlled on the ancilla register. The result of these operations prepares the state

using an additional \(| B| +\log (| B| )\) qubits with \(a=m+k+{k}^{{\prime} }+2\) the ancilla qubits used in block encoding \({{\mathcal{U}}}_{{b}_{i}}\).

Observe that the probability of observing the ith bitstring of the ancilla register can be expressed as

which resulted from the fact that the amplitude in front \(\left\vert i\right\rangle\) is directly related to the Hadamard test success probability. Therefore, in the same way as the standard Hadamard test, the frequency at which we observe the ancilla register in state \(\left\vert j\right\rangle\) upon measurement is directly related to the strength of the response in the region bj.

Under reasonable assumptions, the number of samples to determine the desired inequalities to high probability is \(O(\log (1/(1-P))| B{| }^{2})\) times, where P is the probability that the ordering obtained by a finite number of samples is correct. Since by assumption the number of bins ∣B∣ is only O(1) the δ parameter for the approximate indicator function can be taken to be some small constant value less than 1/∣B∣. Once we have sampled from this distribution we will have a rough sketch of which of the B bins has the largest response. Additionally, since the number of bins in this stage of the algorithm is independent of problem size, each one of these bins can be resolved using only \(\widetilde{O}(1)\) queries to UH.

Let bi be some bin which contained a large response and ∣bi∣ ∈ O(1/∣B∣). Our goal is to further resolve which subset(s) of bi have largest response. As above, we can subdivide bi into ∣B∣ sub-intervals and once again perform the linear combination of Hadamard tests. Then by measuring the ancilla used in the LCU, we obtain information about which sub-bins of bi have large response. Continuing in this fashion we can iteratively resolve the response onto an interval of size o(γ/α). Pseudocode describing the control flow for one run of this algorithm can be found in Alg. 1 and a visualization for how the binary search procedure might proceed can be found in Fig. 8 in the supplementary materials. We detail the cost of determining some interval of large response in the following theorem.

Theorem 1

(Frequency bin sorting (informal)). There exists a quantum algorithm to determine frequency bins corresponding to large amplitudes to resolution O(γ/α) using \(\widetilde{O}({\alpha }^{2}{\beta }^{2}/\gamma )\) queries to the (α, m, 0) block-encoding of UH and O(αβ2) queries to the (β, k, 0) block-encodings of UD and \({U}_{D}^{{\prime} }\). (See Theorem 5 in the supplementary materials for additional details)

Proof

Let δ0 = O(1) be the smoothing parameter for the Heaviside approximation and [a, b] the bin we wish to find the largest response in with Δ ∈ O(1). Let ∣B∣ be the number of sub-intervals we use at each stage of the algorithm. Let B be an equal subdivision of [a, b] into ∣B∣ bins and let bi = [a + ib/∣B∣, a + (i + 1)b/∣B∣] ∈ B be an interval of width O(1/∣B∣). Define \({{\mathcal{U}}}_{i}=\frac{1}{2}(I+{U}_{{D}^{{\prime} }}{U}_{{\tilde{1}}_{{b}_{i}}}{U}_{D})\).

To prepare the linear combination of Hadamard tests with \({{\mathcal{U}}}_{i}\) requires constructing a linear combination of O(∣B∣) terms of the form

which requires O(∣B∣) ancilla qubits for the linear combination with the identity to form the Hadamard test and an additional \(\log (| B| )\) ancilla for the linear combination of Hadamard tests. This in turn queries the block-encodings of the form \({{\mathcal{U}}}_{i}\,O(| B| )\) times.

Since splitting into ∣B∣ intervals requires that δ0 → δ0/∣B∣ = : δ1, we have that the number of queries to the block-encoding \({U}_{{H}_{0}}\) increases by a factor of \(\widetilde{O}(| B| )\) by Lemma 29 of ref. 22. However, since we only need to find the sub interval of b1 with large response to some constant probability, we only need to repeatedly measure the ancilla \(\widetilde{O}(1)\) times. The first iteration therefore requires \(\widetilde{O}(| B{| }^{2})\) queries to UH. Therefore, the cost is entirely dominated by the size and number of the intervals.

If we let b2 be a subdivision of b1 into ∣B∣ bins, we have δ0 → δ0/∣B∣2, increasing the number of queries to O(∣B∣3). In general, if we repeat this algorithm for k iterations, we find that the number of queries to UH = O(∣B∣2 + ∣B∣3 + ⋯ ∣B∣k) = O(∣B∣k). We desire that ∣B∣−k < γ, meaning that the bins at iteration k are smaller than the desired resolution γ. This implies \(k=O(\log (1/\gamma ))\). For the simplest case of ∣B∣ = 2 requires only a single additional ancilla, and the total number of queries to UH is \(O({2}^{k+1})={2}^{2+\log (1/\gamma )}\) this corresponds to a total number of queries to UH that is O(1/γ), which upon rescaling by the subnormalization gives a number of queries that is O(α/γ).

However, because there is a success probability associated with the block-encodings, this increases the query complexity by a factor of \(\widetilde{O}(\alpha {\beta }^{2})\) to obtain success with some constant probability. This results in the final query complexity \(\widetilde{O}\left({\alpha }^{2}{\beta }^{2}/\gamma \right)\) queries to UH and \(\widetilde{O}(\alpha {\beta }^{2})\) queries to UD and \({U}_{{D}^{{\prime} }}\). Since we are able to improve the spectral resolution at a rate which is linear in γ−1, the desired resolution, this algorithm saturates the Heisenberg limit up to scalar block encoding factors.

This procedure allows us to systematically “sift" through the spectrum when searching for regions where the response is most prominent. This allows us to focus the computational resources in approximating the response to high-accuracy only in regions where the response is most pronounced. To ensure a frequency resolution consistent with the problem, the spectrum should be resolved to o(γ), which is the broadening parameter. Therefore, in regions where the response is largest we continue to halve the domain until the size of the bins are O(γ). We refer the reader to Fig. 8 for a visualization.

The main source of cost in the polynomial approximation occurs from the size of the smoothing parameter δ. As a result, iterations with larger bins have smaller cost than iterations with smaller bins. Furthermore, since the goal is only to determine inequalities amongst the bins, and not their values, the bins can be sorted with high probability using tail bounds of the sort found in Lemma 3 in the supplementary materials. Since this approach saturates the quantum limit asymptotically, we believe this approach is nearly optimal for block-encoding based algorithms of this kind.

Once we have run this procedure and have determined the most prominent frequency bins, e.g. at the location of a peak, we would like to accurately approximate the height of the peak. Chebyshev’s inequality bounds the number of expected samples to achieve an ϵ accurate approximation scales to \({N}_{{\rm{samples}}}\in O\left({\epsilon }^{-2}\right)\) to achieve an ϵ accurate result. We would like to have that our algorithm saturates the Heisenberg limit for estimating the heights of the found peaks. However, this cannot be done with the standard Hadamard test. In order to obtain the Heisenberg limit for our algorithm we will need to use amplitude estimation which uses quantum phase estimation on the circuit corresponding to the block-encoding \({{\mathcal{U}}}_{i}\).

Theorem 2

(Approximating bin heights (informal)). Given a small interval [a, b] with Δ ≡ ∣b − a∣/2 = o(γ/α) and a fixed ϵ > 0, there exists a quantum algorithm that makes \(O\left({\alpha }^{2}{\beta }^{2}/(\gamma \epsilon )\right)\) queries to the (α, m, 0) block-encoding of UH and \(O\left(\alpha {\beta }^{2}/\epsilon \right)\) queries to the \((\beta ,{m}^{{\prime} },0)\) block-encodings of UD and \({U}_{D}^{{\prime} }\) to obtain the average amplitude on the region [a, b] to additive accuracy ϵ. (See supplementary materials Corollary 1 for additional details).

Proof

Our goal is to estimate \({\mu }_{[a,b]}=\left\vert \left\langle {\psi }_{0}\right\vert {D}^{{\prime} }{1}_{[a,b]}(H)D\left\vert {\psi }_{0}\right\rangle \right\vert\), with an approximator \({\hat{\mu }}_{[a,b]}\) so that \(| {\hat{\mu }}_{[a,b]}-{\mu }_{[a,b]}| \le \epsilon\).

Assume that,

where \({\widetilde{\mu }}_{[a,b]}\) is the exact expected value of the approximate distribution with respect to the ground state wavefunction.

We would like to find conditions on \({\epsilon }^{{\prime} },\widetilde{\epsilon }\) so that whenever \(| {\widetilde{\mu }}_{[a,b]}-{\mu }_{[a,b]}| \le {\epsilon }^{{\prime} }\) (error from approximation of indicator) and \(| {\widetilde{\mu }}_{[a,b]}-{\hat{\mu }}_{[a,b]}| \le \widetilde{\epsilon }\) (error from sampling compared true average of approximate indicator) \(\ \Rightarrow \ | {\mu }_{[a,b]}-{\hat{\mu }}_{[a,b]}| < \epsilon\), our desired accuracy. Observe that

which we desire to be smaller than ϵ which implies that \({\epsilon }^{{\prime} }+\widetilde{\epsilon } < \epsilon\). Thus, whenever the approximation error \(\widetilde{\epsilon }\) satisfies that \(\tilde{\epsilon }\ll \epsilon\), we need to find an \({\epsilon }^{{\prime} }=O(\epsilon )\) accurate approximation to result. However, because the success amplitude is rescaled by the subnormalization factor ζω = O(αβ2), the success probability is \(O\left({(\alpha {\beta }^{2})}^{-2}\right)\), so the number of repetitions increases by a factor of \(O\left({(\alpha {\beta }^{2})}^{2}\right)\).

Using amplitude amplification improves this query complexity by a quadratic factor to O(αβ2). Then, using the block-encoding \({\mathcal{U}}\) with the quantum phase estimation algorithm to use amplitude estimation requires an additional factor of O(1/ϵ) controlled-applications of \({\mathcal{U}}\) to calculate the expectation value to accuracy ϵ requires O(αβ2/ϵ) total queries to \({\mathcal{U}}\) and its controlled version. The algorithm which directly samples the output distribution would require the standard O(1/ϵ2) repetitions, so the amplitude estimation routine improves over direct sampling by a factor of O(1/ϵ).

The number of queries to form the block-encoding of the indicator function depends on the degree d of the polynomial needed to approximate the indicator function to the desired precision. As was shown in Lemma 29 of ref. 22, we know that \(d=\widetilde{O}(1/\delta )=\widetilde{O}(\alpha /\gamma )\), so the total number of queries to the block-encoding of H0, UH, is \(\widetilde{O}({\alpha }^{2}{\beta }^{2}/\gamma \epsilon )\).

At this point, we can estimate the cost to run this algorithm for the problem of second quantized quantum chemistry. If we assume the empirical scaling, α ∈ O(N2), and use the estimate that β = O(∣∣d∣∣η) ∈ O(Nη) from the second quantization block-encoding procedure, we have that the total number of queries to UH is

or, suppressing logarithmic factors we have

Obtaining higher order polarizabilities

The above algorithm provides a method for computing the overlaps and excitation energies which can then be used with a classical computer to obtain first-order response functions. A straightforward generalization of the above procedure can be used to compute various terms in the numerator as well as the energies needed to evaluate the denominator.

Consider a product of block-encodings of the form

For now, ignoring subnormalization factors and ancillary qubits, if we can successfully implement controlled \({{\mathcal{U}}}_{2}\) in a Hadamard test, then we can gain information about\(\left\langle {\psi }_{0}\right\vert {{\mathcal{U}}}_{2}\left\vert {\psi }_{0}\right\rangle\). We can relate this to the desired information by observing

Therefore, estimates this quantity provide estimates to ωm0 ∈ [a, b] and ωnm ∈ [c, d] as well as the response observed in the region. In turn, this can be used to approximate the first hyperpolarizability.

The same procedure for roughly determining the distribution by forming a superposition over large regions of the frequency domain works for nonlinear response as well in the form of a 2-dimensional grid. First we discretize the interval [−1, 1] into ∣B∣ bins with bi as above. Consider the Cartesian product B × B which is the set of all tuples (bi, bj) for bi, bj ∈ B and take two registers of size \(\left\lceil \log (| B| )\right\rceil\) and prepare each in the uniform superposition over ∣B∣ states and implement the controlled unitary

where \({{\mathcal{U}}}_{i,j}={U}_{{D}^{{\prime\prime} }}{U}_{\tilde{1}{b}_{j}}{U}_{{D}^{{\prime} }}{U}_{{\tilde{1}}_{{b}_{i}}}{U}_{D}\). Measuring the ancilla registers, the algorithm outputs the bitstrings i, j with probability

which provides data on the strength of the response in the 2-d region bi × bj.

To implement this, we need access to UH to form \({\{{{\mathcal{U}}}_{i,j}\}}_{i,j = 1}^{| B| }\) and its controlled version. Each one of the \({{\mathcal{U}}}_{ij}\) can be implemented with a degree d = O(∣B∣) polynomial. Since there are O(∣B∣2) of these, each one requiring O(∣B∣) queries to UH gives a total query complexity to UH that is \(\widetilde{O}(| B{| }^{3})\). Using the same procedure as above, we sample from a distribution over O(∣B∣2) elements and determine a pair (i, j) corresponding to the region \({b}_{i}^{0}\times {b}_{j}^{0}\) which has the largest response with some probability. We then subdivide the box \({b}_{i}^{0}\times {b}_{j}^{0}\) into into ∣B∣ bins, each of size O(1/∣B∣4). This will require \(\widetilde{O}(| B{| }^{5})\) queries to UH to implement and \(\widetilde{O}(1)\) repetitions to determine a new bin \({b}_{i}^{1}\times {b}_{j}^{1}\). We wish to repeat this k times until \(| {b}_{i}^{k}\times {m}_{j}^{k}| =O({\gamma }^{2}/{\alpha }^{2})\). This means that \(k=O(\log (\gamma /\alpha ))\). Then, the total number of queries to UH is

But the success probability for this procedure requires an additional number of queries that is O(α2β3), where we assume that the subnormalization factor β is the same for all the dipole operators. Then, the total query complexity is

This binary-search inspired procedure for finding frequency bins of pronounced response can be generalized to any order. In the case of nth order response functions, where one desires to determine a n-dimensional bin of frequencies b0 × b1 × ⋯ × bn−1 where the size of the bin is order \(O\left({\left(\gamma /\alpha \right)}^{n}\right)\), will in general require \(\widetilde{O}\left({(\alpha /\gamma )}^{n}\right)\) queries to UH to form the desired polynomial. An additional factor of O(αnβn+1) arises due to the success probability of implementing the \({\mathcal{U}}\)’s, so that the total complexity is expressed as

queries to UH. These can then be used to evaluate the Iij portions of the terms in Eq. (59).

Once the region has been determined where the response is desired accurately, one can either Monte-Carlo sample or use amplitude estimation which increases the query complexity by a factor of O(1/ϵ2) and O(1/ϵ) respectively. The amplitude estimation based sampling algorithm will therefore scale as

queries to UH to measure the response in some small frequency bin to precision ϵ. Of course, this will need to be repeated for many bins, so the cost is additive in total number of bins one needs to consider to accurately compute the terms corresponding to the \({d}_{lm}^{k}\)’s in Eq. (59). Therefore, this methodology could in practice be used to compute high-precision estimates to nonlinear quantities in optical and molecular physics.

Using our estimates for α and β used in block-encoding H0 and the dipole operators in second quantization gives an expected query complexity to the molecular Hamiltonian block encoding for nth order molecular response quantities that is

The bulk of the complexity of this algorithm comes from two sources, the success probability of the block-encodings and the spectral resolution required. Note that in many cases the success probability estimates can be very pessimistic, as the numerator can be quite large and compensate for a large subnormalization factor in the denominator. However, improving over the γnϵ−1 resolution and precision scaling would imply a violation of the Heisenberg limit, so we expect that the factor of O(γnϵ−1) cannot be improved in general.

Discussion

In this work, we have shown how one can calculate molecular response properties for the fully correlated molecular electronic Hamiltonian using the dipole approximation for nth order response functions in a manner that can be implemented in \(O\left({\alpha }^{2n}{\beta }^{n+1}/({\gamma }^{n}\epsilon )\right)\) queries to the Hamiltonian block encoding, with α and β the block encoding subnormalization factors for the Hamiltonian and the dipole operators respectively. In this section we will use the estimates α = O(N2) and β = O(Nη). Due to electronic correlation, many classical methods such as time-dependent density functional theory can fail to capture correct quantitative and even qualitative behavior of the absorption strengths and excitation energies of molecules interacting with light. Since quantum algorithms can efficiently time-evolve the full molecular electronic Hamiltonian, quantum algorithms can efficiently capture highly correlated electronic motion. Accordingly, there has been interest before our work in developing quantum algorithms for estimating linear response functions. There are multiple works that we are aware of that report algorithms1,2,3,4 for computing similar spectroscopic quantities to those we compute in the above sections.

In the work of ref. 1, the response function is calculated by solving a related linear system with a quantum linear systems algorithms such as HHL26. They report a poly(N) complexity but do not discuss the degree of this polynomial. Their approach is to solve the linear system

by block encoding the dipole operator D. Solving this system for a sequence of ω’s with spacing smaller than the damping parameter γ and for each direction, one can obtain an approximation to the frequency dependent polarizability. One difficulty of this approach is that HHL requires many additional ancilla qubits to perform the classical arithmetic to compute the \(\arccos\) function of the stored inverted eigenphases as well as a dependence on the condition number of the linear system. The scaling of HHL is \(\widetilde{O}({\kappa }^{2}/\epsilon )\), where κ is the condition number of A(ω). However, this cost in quantum linear solvers can be improved by using more recent work based on quantum signal processing (QSP) and the discrete adiabatic theorem. These methods can solve the linear system problem with \(\widetilde{O}(\kappa \log (1/\epsilon ))\)27 queries to a block encoding of A(ω). Once the quantum state corresponding to a solution is prepared, measurements of the observable \(\left\langle {\psi }_{0}\right\vert {D}^{{\prime} }D\left\vert {\psi }_{0}\right\rangle\) as well as \(\left\langle x\right\vert {A}^{\dagger }(\omega )A(\omega )\left\vert x\right\rangle\) are required to extract similar information to that in our algorithm. Since the number of terms in A(ω) is the same as the number of terms in H, O(N2), the number of terms is A†A = O(N4). This will in general require O(N4/ϵ2) repetitions of the circuit to obtain an estimate to \(\left\langle x\right\vert {A}^{\dagger }(\omega )A(\omega )\left\vert x\right\rangle\), assuming the variance is O(1)28. We take as estimates that \(\kappa (A)=\widetilde{O}(| | H| | /\gamma )=\widetilde{O}({N}^{2}/\gamma )\), and that the success probability for block-encoding for the dipole with subnormalization β = O(Nη) is improved with amplitude amplification. Using the HHL-based algorithm originally presented in ref. 1, the expected scaling is \(\widetilde{O}(N\eta {\kappa }^{2}{N}^{4}/{\gamma }^{2}{\epsilon }^{3})\) which simplifies to \(\widetilde{O}(\eta {N}^{9}/{\gamma }^{2}{\epsilon }^{3})\) queries to the time evolution operator for the linear operator A(ω). Using more modern techniques based on block encoding, we obtain the scaling \(\widetilde{O}({N}^{7}\eta /\gamma {\epsilon }^{2})\) queries to the block encoding of UH for estimating the response at a particular frequency using the algorithm in ref. 1 to ϵ accuracy.

Another algorithm reported in ref. 3 presents a quantum algorithm for computing response quantities such as the polarizability in linear response theory. Similar to our work, the authors begin by assuming the observable \({\mathcal{A}}\) they wish to compute the response function for has a one-body decomposition in the electron spin–orbital basis

and access to the ground state \(\left\vert {\psi }_{0}\right\rangle\). Here, instead of directly block-encoding \({\mathcal{A}}\), the authors block-encode individual matrix elements of \({\mathcal{A}}\) and apply it to the ground state. For a particular matrix element \({{\mathcal{A}}}_{mn}{a}_{m}^{\dagger }{a}_{n}\), they decompose into an LCU using the JW or Bravyi–Kitaev transformation, with off-diagonal terms having a representation as the linear combination of 8 unitary matrices. This block encoding will have a success probability that depends on the overlap, \(\left\langle {\psi }_{0}\right\vert {a}_{m}^{\dagger }{a}_{n}\left\vert {\psi }_{0}\right\rangle\), which will be small in regions where the n → m response is also small. Indeed, this block-encoding of a projector can be exponentially small or even zero if the particular transition is restricted by the problem symmetry. If the block-encoding is successful, then the state \({a}_{m}^{\dagger }{a}_{n}\left\vert {\psi }_{0}\right\rangle\) will be prepared in the system register. Then the authors apply QPE on the state \({a}_{m}^{\dagger }{a}_{n}\left\vert {\psi }_{0}\right\rangle\) and repeatedly measure until the phase estimation procedure successfully returns the bitstring corresponding to the energy of the associated transition. This work additionally numerically simulates their algorithm for the C2 and N2 molecules, and finds reasonable fitting to the response functions computed classically with full-configuration interaction. Although explicit circuits are presented which implement this algorithm, the computational complexity of this algorithm is not discussed in detail.

Additionally, a variational algorithm is proposed in ref. 2 to approximate the first-order response of molecules to an applied electric field. This algorithm operates similarly to ref. 1, but instead uses a variational ansatz on the solution state \(\left\vert \psi ({\boldsymbol{\theta }})\right\rangle \sim \left\vert x\right\rangle\) to minimize a cost function resulting from a variational principle for the polarizability. This computation also has a similar overhead in computing expectation values as ref. 2, and similarly does not permit a priori guarantees of accuracy and runtime that can be provided by fully coherent quantum algorithms such as HHL, QPE, and QSP.

In this work we have presented a quantum algorithm for computing general linear and non-linear absorption and emission processes which can be used in conjunction with simple classical post-processing to approximate response functions in molecules subjected to an external electric field treated semi-classically. Our work extends previous research which have approached this problem very differently. We compare our approach to these methods, and in cases where rigorous complexity estimates can be obtained, show that our approach scales more favorably than previous methods. Our algorithm approaches the difficult problem of obtaining high-fidelity estimates to the desired matrix elements with a quantum approach, and combines these results on a classical computer to obtain a parameterized representation of the response function for the given molecule. Furthermore, our algorithm is conceptually simple and employs a measurement scheme that reduces the computational effort over regions where the response is negligible. We showed that our quantum subroutine combined with the feedback from measurements is nearly optimal at determining excitation energies of the Hamiltonian. In addition, beyond the ancilla qubits for block-encoding the desired operation, our algorithm can be effectively reduced to a Hadamard test for non-unitary matrices which requires only a single additional ancilla; or a linear combination of such circuits.

We additionally presented a method to find the dominant contributions to the response function with a systematically improvable procedure to resolve spectral regions where the response is most pronounced at the Heisenberg limit. Once the region of interest has been determined to the desired resolution, then one can either sample at the standard classical limit or use amplitude estimation procedure to estimate the response function magnitude in a particular spectral region. Finally, our algorithm can be used to compute response functions to any desired order through iterative applications of the algorithm presented for linear response, so long as the electric dipole approximation accurately describes the desired physics. Of course as one goes to higher order of response function, there is a combinatorial explosion in the number of terms that need to be computed that is unavoidable for any current algorithm. However, it is often the case that response functions are only calculated or experimentally determined up to some small constant order or a very small number of fixed terms.

Additionally, the subnormalization factors also grow exponentially in the desired order of response. Near the end of this work, we became aware of a work published recently29, which performs a similar task with a different approach. In their Heisenberg-limited scaling algorithm, they perform a Gaussian fitting based on Hadamard tests of the Hamiltonian simulation matrix performed for times drawn from a probability density formed by the Fourier coefficients. In both cases, it will be of interest to study the robustness of these methods to imperfections in the ground state preparation.

In many instances the methods for computing these response functions do not permit provable guarantees on the accuracy of the result. However, using the power of quantum computing, it is tractable to perform eigenvalue transformations on very high dimensional systems making this algorithm efficient. Future work investigating other paradigms beyond block encoding that do not have possible issues with success probabilities could be of interest. In lieu of this, it may be possible that additional analysis can be performed to improve the estimates on the success probability for block encoding the dipole operators, using spectroscopic principles such as the Thomas-Reiche-Kuhn sum rule. Furthermore, since our algorithm only includes electronic degrees of freedom, it is a topic of future work to study how the asymptotic scaling of this algorithm compares when including vibronic degrees of freedom.

Methods

In this section, we first introduce the “Molecular Hamiltonian” and “Electronic spectroscopy” in the electric dipole setting and then summarize the main algorithmic primitives used in this work. These are the “Linear combination of unitaries” and “Quantum signal processing”. Unless otherwise noted, we will use ∣∣ ⋅ ∣∣ to refer to the vector 2-norm when the argument is a vector and the spectral norm, i.e. the largest eigenvalue, when the argument is a matrix. We use the notation ∣ ⋅ ∣ to refer to the absolute value if the argument is a scalar and is the set cardinality if the argument is a set. We use the over bar notation \(\widetilde{\cdot }\) to refer to approximate quantities. Furthermore, we will assume fault-tolerance throughout this work, and any errors result from approximation techniques or from statistical sampling noise. We analyze the effect of both of these kinds of errors in the text.

Molecular Hamiltonian

We begin by assuming that the system of interest is well approximated by the electronic Hamiltonian under Born–Oppenheimer approximation, with clamped nuclei represented as classical point charges. Starting from a Ritz–Galerkin discretization scheme, where basis functions are spin–orbitals in real space, we obtain the molecular electronic Hamiltonian in second quantization as

where a† and a are the fermionic creation and annihilation operators respectively, and N is the number of spin–orbital basis functions. p, q, r, s denote spin-orbital indices unless otherwise noted. We will work in the atomic units, where the reduced Planck constant ℏ, electron mass me, elementary charge e, and permittivity 4πϵ0, are set to 1.

The first term in the electronic Hamiltonian encapsulates the one-body interactions, including the kinetic energy of the electrons and the electron–nuclear interaction. The matrix elements are computed by finding the representation of the kinetic energy and electronic–nuclear repulsion terms in the chosen spin–orbital basis, which for the pth basis function is denoted as ϕp.

where \({\bf{r}}\in {{\mathbb{R}}}^{3}\) is the position coordinate vector for an electron, \({{\bf{R}}}_{\alpha }\in {{\mathbb{R}}}^{3}\) is the αth nuclear position coordinate vector, Zα is the integer electric charge of the αth nuclei, ϕp(r) is the spin-orbital basis function, and \({\nabla }_{{\bf{r}}}^{2}\) is the 3-dimensional Laplacian operator.

The second term, which is only a function of the electronic positions, is the two-body interaction term. The matrix elements are

which is the representation of the Coulombic repulsion in the MO basis. Due to the O(N4) terms in the two-body term as opposed to the O(N2) terms in the one-body term, it is the dominant contribution to the complexity of simulating the electronic Hamiltonian without further approximation. However, recent techniques based on double factorization or other tensor factorizations of the 2-electron operator18, can reduce this to between O(N2) terms where N scales with number of atoms and O(N3) terms where N scales with basis set size for a fixed number of atoms17,19 or even fewer in practice16. In the following, we will assume O(N2) scaling for number of terms.

Electronic spectroscopy

Spectroscopy allows physical systems to be probed via their interaction with light. A very common form of spectroscopy is electronic absorption spectroscopy, for which the UV-Vis frequency range allows probing of molecular electronic transitions (see e.g. ref. 30 Section 5 for a review). A typical molecular electronic absorption spectroscopy experiment consists of a sample of molecules in solution, that is irradiated by broadband light in the visible to ultraviolet range. The absorption spectrum is is calculated from the difference in intensity with and without the sample present.

Spectroscopy experiments yield vital information about the excited state energies and absorption probabilities of the system of interest. Quantities such as the oscillator strengths, static and dynamic polarizabilities, and absorption cross-sections are used to understand the electronic structure of molecular systems and to design materials that respond to light at specific frequencies31,32.

Typical molecular electronic absorption spectroscopy is performed with laser fields that can be represented by classical fields, resulting in a semi-classical description in which the electronic degrees of freedom are treated quantum mechanically and interact with a classical electromagnetic field. The interaction between charged particles and the electromagnetic field is described by the minimal coupling Hamiltonian

where α indexes over all charged particles. pα, qα, rα, and mα are the momentum, charge, position, and mass of the αth particle, respectively. A is the classical vector potential of the electromagnetic field. Note that the Hamiltonian is now time-dependent due to the fact that the classical field is time-dependent. Since the length scales of molecules are typically much smaller than the wavelength of visible light that gives rise to electronic transitions, one can invoke the dipole approximation to rewrite the Hamiltonian of Eq. (40) into the dipole–electric field form as31,33,34.

Here, d is the dipole operator, which consists of a nuclear part dn and an electronic part de. They are defined as

where α and β index over the nuclei and electrons, respectively. Under the Born–Oppenheimer approximation, the dipole matrix element 〈n∣d∣m〉 for the transition between electronic states \(\left\vert n\right\rangle\) and \(\left\vert m\right\rangle\) has no contribution from the nuclear part dn because the electronic wavefunctions are orthogonal. The electronic contribution to the matrix element is usually written as a product of a nuclear wavefunction overlap and an electronic dipole matrix element 〈m∣de∣n〉, where \(\left\vert m\right\rangle\) and \(\left\vert n\right\rangle\) are the electronic wavefunction. The nuclear wavefunction overlaps give rise to the vibronic structure in electronic spectra35. In this work, we shall ignore the quantum nature of nuclei and therefore neglect the vibronic effects in electronic spectroscopy. Since only the electronic part of the dipole moment, de contribute to the dipole matrix elements in electronic transitions, from now on, we will denote de as d for notational simplicity.

We can now obtain the second-quantized representation of d by computing matrix elements in the fixed MO basis for the unperturbed Hamiltonian. Thus

gives the representation of the matrix element of the ith component di of the vector operator d in the spin-orbital basis used in defining the one and two electron integrals for H0, Eqs. (38) and (39). Here ri denotes the ith component of the position r in 3-d space. Once the basis has been selected and the relevant integrals performed, we then obtain the following second quantized representation of d,

where dpq is a 3-vector with components d1,pq, d2,pq, and d3,pq.

Once the induced dipole moment d is calculated, many quantities of interest, such as the linear or nonlinear electric susceptibilities, can be derived from the matrix elements formed by the eigenvectors of the unperturbed Hamiltonian \({{\bf{d}}}_{mn}=\left\langle m\right\vert {\bf{d}}\left\vert n\right\rangle\). Typically, absorption spectroscopy starts in the electronic ground state (assuming room temperature, ~300 K), so we set m = 0, and n indexes the set of all excited electronic eigenstates. Electric susceptibility measures the response of the molecular dipole moment to external electric fields. It is defined generally in the response formalism as

where χ(n) is the nth order susceptibility31, and the sum of the terms involving χ(n) is the nth order dipole moment, denoted as \({d}_{i}^{(n)}\). For weak-light matter interaction, as in the case of most electronic spectroscopy experiments, only the low-order effects are important. For example, the linear susceptibility χ(1) provides information about the absorption from the ground state. Due to symmetry considerations, the second order susceptibility χ(2) and all other even order susceptibilities are zero if molecules are isotropically distributed, as in the case of molecules in solution. The third order susceptibility χ(3) is widely used by nonlinear spectroscopists in experiments such as pump-probe or two-dimensional electronic spectroscopy, and it can be used to describe the dynamics in excited states. Higher order effects such as χ(5) have also been studied recently36.

The expressions for χ(n) can be derived from the perturbative expansion of the time evolution of the density matrix describing the electronic state of the molecule, and they are given by

\({\rho }_{0}=\left\vert 0\right\rangle \left\langle 0\right\vert\) is the ground state density matrix. The superscript × in \({d}_{i}^{\times }\) denotes the commutator superoperator, whose action on a general operator X is defined as \({d}_{i}^{\times }X=[{d}_{i},X]\). The Green’s function \({\mathcal{G}}(s)\) is the time-evolution superoperator, defined by the action

where the step function

ensures that \({\mathcal{G}}(s)\) acts non-trivially only when s > 0. The exponential factor e−γs in the definition of \({\mathcal{G}}(s)\) is a phenomenological decay factor that accounts for the decay of electronic coherence and excited state populations, typically due to the interaction with nuclear degrees of freedom or the quantized photon degrees of freedom. For simplicity, we assume a constant decay rate γ for all elements \(\left\vert m\right\rangle \left\langle n\right\vert\) of the density matrix. However, this assumption can be relaxed straightforwardly.

Sometimes the susceptibilities are expressed in the frequency domain. We denote the frequency domain susceptibilities as α(n), and it is defined by

where ωs = ω1 + ⋯ + ωn. We have used the following definition for the Fourier transform

The frequency-domain susceptibilities α(n) are related to the time-domain susceptibilities χ(n) by

where Sn is the symmetric group, and P indexes over all n! possible permutations of the n interactions. This sum takes into account all possible time-orderings of the n interactions. To obtain χ(n)(ω1 + ⋯ + ωn, ⋯ , ω1), we first note that by applying Eq. (47), the action of the time-domain Green’s function \({\mathcal{G}}(s)\) on the matrix element \(\left\vert m\right\rangle \left\langle n\right\vert\) in the energy eigenstate basis is

where ωmn = ωm − ωn.

As an example, using Eqs. (46) and (52), the linear susceptibility in the time-domain is expressed in the sum-over-state form as

where di,mn = 〈m∣di∣n〉. Using Eq. (51), the linear susceptibility in the frequency domain is

The notation (ω → −ω)* means switching all ω to −ω in the previous term and then taking the complex conjugate.

The first-order susceptibility is also known as the polarizability. It is a measure of the amount of change in the electronic configuration when subjected to an external electric field. In particular, the imaginary part of α(1) is proportional to the absorption spectrum. γ is usually defined as the half-width-half-maximum of the peaks, also referred to as the spectral resolution (see30 Sec. 7.5). Finite values γ ≠ 0 make Eq. (54) well defined when the laser frequency is resonant with a molecular transition, i.e., ω = ωn0.

Higher-order response functions such as the first hyperpolarizability and higher susceptibilities can be expressed in terms of higher-order moments of the induced dipole operator d. The calculation of these quantities also requires computing matrix elements for excited state-to-excited state transitions, not just ground-to-excited-state transitions. These quantities provide valuable information characterizing light-matter interactions. For example, third-order response functions are used in the modeling of four-wave mixing in non-linear phenomena, which have numerous applications in the modeling of optical physics, see e.g.37,38,39,40.

For arbitrary nth order spectroscopies, we need in general to compute O(2n) correlation functions in the time domain (see ref. 41 Eq. 30) because each of the n interactions involves a commutator, which has two terms (see Eq. (46)). Each of these requires an additional O(n!) permutations of the orderings in which we apply the operators (see Eq. (51) and ref. 41 Eq. 59). For example, the computation of third order response functions in the frequency domain requires the evaluation of 48 correlation functions. In general, the asymptotic scaling for nth order spectroscopies can almost certainly be assumed to be O(1) while also however being significantly larger than a single term. Thus, while higher-order spectroscopic are of interest (e.g., fifth-order spectroscopy can reveal details of exciton–exciton coupling36), many of these higher-order quantities are nevertheless inaccessible with any known classical algorithm with provable performance bounds.

However, this number of terms may be greatly reduced in practice due to problem symmetries, and often practioners are interested in specific contributions, not in the sum of all 48 terms because experiments can directly probe specific terms by making use of pulse-ordering and phase matching31. For example, by choosing a fixed time ordering for the three pulses, there is no need to permute the three frequencies, so the number of terms reduces to 48/6 = 8. Matching the optical phase of input and output pulses and ensuring that the output signals from different terms are projected into different spatial directions allow the number of terms to be reduced to just two terms which are complex conjugates.

As another example, we consider the commonly encountered third-order response function. Using Eq. (46), the third order susceptibility in the time domain can be written as

where

The superscripts l and r denote the left- and right-multiplying superoperator, i.e., AlX = AX and ArX = XA. Each Rν can be expressed explicitly in the sum-over-state form. For example,

The four Rν can be represented diagrammatically in terms of the double sided Feynman diagrams31,41, and they represent different nonlinear physical processes. For example, both R1 and R2 can describe the processes of excited state absorption and stimulated emission, depending on the intermediate states involved. R3 and R4 can describe the processes of ground state bleach. The processes can be further classified into rephasing and non-rephasing pathways, which can be distinguished experimentally using phase matching. Comparison between signals from the rephasing and non-rephasing pathways provides important information regarding the inhomogeneity of the sample. It is common to perform Fourier transforms on the first and the third time variables in Rν(s3, s2, s1), and write it as Rν(ω3, s2, ω1). These quantities are directly related to the spectra obtained in pump-probe spectroscopy or two-dimension electronic spectroscopy experiments, and they reveal the dynamics of electronically excited states.

Using Eqs. (51) and (55), the frequency-domain third order susceptibility α(3) can be written as

Rν(ω3, ω2, ω1) can be expressed explicitly in the sum-over-state form. For example,

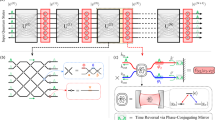

Linear combination of unitaries

Block encoding is a technique to probabilistically implement non-unitary operations on a quantum computer and one approach to constructing a block encoding is the method of linear combination of unitaries (LCU)42. LCU begins by assuming you have a matrix operation A that has a decomposition into k unitary matrices Uk

The goal is to embed the matrix operation given by A into a subspace of a larger matrix UA which acts as a unitary on the whole space. Because of the restriction to unitary dynamics, we require that ∣∣A∣∣ ≤ 1. Since this is difficult to satisfy for a general matrix, a subnormalization factor α is used so that ∣∣A∣∣ ≤ α. The block encoding UA can be expressed in matrix form

With LCU, it is straightforward to obtain an upper bound on ∣∣A∣∣ as

Then, scaling the LCU by 1/α

we have a matrix that can be block encoded using LCU.

The unitary description of LCU is as follows. We use an ancilla register of \(q=O(\log (k))\) qubits and define the oracle which “prepares” the LCU coefficients

which is a normalized quantum state and corresponds to the first column of a unitary matrix. Next, we implement the controlled-application of the desired unitaries using the “select” routine

Then, the block encoding can be expressed as the n + q qubit unitary

The circuit diagram corresponding to this transformation is shown in Fig. 4.

PREP prepares the LCU coefficients βl into a quantum state \({\sum }_{l}\sqrt{{\beta }_{l}}{\left\vert l\right\rangle }_{q}\), and SEL selects the unitary operator to apply conditioned on the state of the ancilla register, where the ⊘ notation is to be interpreted as a control on all states in the ancilla register. After uncomputing the ancilla register with PREP†, the normalized dipole operator is applied to the system register conditioned on the ancillary system with \(q=O(\log (k))\) being measured in the all-zero state.

A block encoding is characterized by 3 parameters, the subnormalization factor α, the number of ancilla qubits q, and the accuracy of the block encoding ϵ.

Definition 1

((α, q, ϵ) Block Encoding). For an n qubit matrix A, we say that the n + q qubit unitary matrix UA is an (α, q, ϵ) block encoding of A if

If we can implement the above unitary UA exactly, then we call it an (α, q, ϵ = 0) block encoding of A.

In the worst case, the complexity of implementing the state corresponding to the coefficients βl is exponentially hard in the number of qubits, i.e. \(\tilde{O}({2}^{q})\)43 gates. However, since the number of qubits is logarithmic in the number of terms in the LCU, the worst case circuit complexity is O(2q) = O(k). If k scales as POLY(N) then the state preparation can be done efficiently. However, in some cases such as the coefficients belonging to a log-concave distribution, the state preparation can be significantly sped up to \(O({\rm{polylog}}(N))\)44. This circuit is applied twice in the PREP and PREP† routines.

Since this procedure is non-deterministic, there is a probability that the computation fails. Success is flagged by the ancilla system being in the state \({\left\vert 0\right\rangle }^{\otimes q}\) and is directly related to the subnormalization factor α. When we apply the block encoding to a state \({\vert \psi \rangle }_{n}{\vert 0\rangle }_{q}\) we obtain

where \(\left\vert \perp \right\rangle\) denotes the orthogonal undesired subspaces. Therefore, the success probability of being in the correct subspace \({\left\vert 0\right\rangle }_{q}\) is,

Therefore, the failure/success probability directly depends on the ratio ξ/α where

In the absence of known bounds for ξ, the best-case bound is that α upper bounds ξ by a constant or logarithmic factor so that the success probability can be boosted to O(1) with only \(\widetilde{O}(1)\) rounds of robust amplitude amplification45. In general, we will need to perform \(\widetilde{O}(\alpha /\xi )\) rounds of amplitude amplification to boost the success probability of the block encoding to be O(1).

Quantum signal processing

Quantum signal processing (QSP) provides a systematic procedure for implementing a class of polynomial transformations to block encoded matrices. For Hermitian matrices A, the action of a scalar function f can be determined by the eigendecomposition of A = UDU†, as

where λi is the ith eigenvalue, and \(\left\vert i\right\rangle\) is the ith eigenvector. For the cases we consider here, the operators are Hermitian, and we use this characterization of matrix functions as a definition. QSP provides a method for implementing polynomial transformations of block encoded matrices. To implement a degree d polynomial, QSP11,46 uses O(d) applications of the block encoding and therefore its efficiency depends closely on the rate a given polynomial approximation converges to the function of interest and the circuit complexity to implement the block encoding.

QSP uses repeated applications of the block encoding circuit to implement polynomials of the block encoded matrix. We assume that A is a Hermitian matrix that has been suitably subnormalized by some factor α so that ∣∣A/α∣∣ ≤ 1. QSP exploits the surprising fact that the block encoding UA can be expressed as a direct sum over one and two dimensional invariant subspaces which correspond directly to the eigensystem of A. In turn this allows one to obliviously implement polynomials of these eigenvalues in each subspace, which builds up the polynomial transformation of the block encoded matrix A/α overall. QSP is characterized by the following theorem, which is a rephrasing of Theorem 4 of ref. 11.

Theorem 3

(Quantum Signal Processing (Theorem 7.2146)). There exists a set of phase factors \({\mathbf{\Phi }}:=({\phi }_{0},\ldots ,{\phi }_{d})\in {{\mathbb{R}}}^{d+1}\) such that

where

if and only if \(P,Q\in {\mathbb{C}}[x]\) satisfy

-

1.

deg(P) ≤ d, deg(Q) ≤ d − 1

-

2.

P has parity \(d\,\mathrm{mod}\,\,2\) and Q has parity \(d-1\,\mathrm{mod}\,\,2\), and

-

3.

∣P(x)∣2 + (1 − x2)∣Q(x)∣2 = 1 ∀ x ∈ [−1, 1]

Given a scalar function f(x), we can use QSP to approximately implement f(A/α) by using the block encoding of A, a polynomial approximation to the desired function, and a set of phase factors corresponding to the approximating polynomial. If f is not of definite parity, we can use the technique of linear combination of block encodings to obtain a polynomial approximation to f that is also of indefinite parity. This corresponds to implementing QSP for the even and odd parts respectively and then using an additional ancilla qubit to construct their linear combination. The last requirement, that P(x) + (1 − x2)∣Q(x)∣ = 1 for every x, is the most restricting and requires normalization of the desired function which can be severe in some cases. However, the polynomial P can be specified independent of the polynomial Q so long as ∣P(x)∣ ≤ 1 ∀ x ∈ [−1, 1] and \(P(x)\in {\mathbb{R}}[x]\) (see Corollary 5 of ref. 22), which is the case for the algorithm presented in this work.

Furthermore, there are efficient algorithms for computing the phase factors for very high degree polynomials. Algorithms for finding phase factors for polynomials of degree d = O(107) have been reported in the literature (see e.g.,24,47,48) and are surprisingly numerically stable even to such high degree. Given this result, conditions (1–3), and that a rapidly converging polynomial approximation exists, one can efficiently approximate smooth functions of the block encoded matrix A/α for very high degree polynomials. Furthermore, QSP provides an explicit circuit ansatz that allows one to know the exact circuit once the phase factors are found. This is a powerful tool since many computational tasks can be cast in terms of matrix functions.

Data availability

The authors report that there is no relevant data or software associated with the production of this paper.

Code availability

The authors report that there is no relevant data or software associated with the production of this paper.

References

Cai, X., Fang, W.-H., Fan, H. & Li, Z. Quantum computation of molecular response properties. Phys. Rev. Res. 2, 033324 (2020).

Huang, K. et al. Variational quantum computation of molecular linear response properties on a superconducting quantum processor. J. Phys. Chem. Lett. 13, 9114–9121 (2022).

Kosugi, T. & Matsushita, Y.-i. Linear-response functions of molecules on a quantum computer: charge and spin responses and optical absorption. Phys. Rev. Res. 2, 033043 (2020).

Roggero, A. & Carlson, J. Linear response on a quantum computer. Phys. Rev. C. 100, 034610 (2019).

Li, J., Jones, B. A. & Kais, S. Toward perturbation theory methods on a quantum computer. Sci. Adv. 9, eadg4576 (2023).

Hait, D. & Head-Gordon, M. How accurate are static polarizability predictions from density functional theory? An assessment over 132 species at equilibrium geometry. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 20, 19800–19810 (2018).