Abstract

In fault-tolerant quantum computing, logical errors in unitary gate synthesis are comparable to the noise inherent in the gates themselves. While mixed synthesis can suppress such coherent errors quadratically, there is no clear understanding of its remnant error, which hinders us from designing a holistic and practical error countermeasure. In this work, we propose that the classical characterizability of synthesis error can be exploited; remnant errors can be crafted to satisfy desirable properties. We prove that we can craft the remnant error of arbitrary single-qubit unitaries to be Pauli and depolarizing errors, while the conventional twirling cannot be applied in general. For Pauli rotation gates, in particular, the crafting enables us to suppress the remnant error up to cubic order, which results in synthesis with a T-count of \({\log }_{2}(1/\varepsilon )\) up to accuracy of ε = 10−9. Our work opens a novel avenue in quantum circuit design and architecture that orchestrates logical error countermeasures.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

It is widely accepted that quantum computers with error correction1,2 can be potentially useful in various tasks such as factoring3, quantum many-body simulation4, quantum chemistry5, and machine learning6. With the tremendous advancements in quantum technology, the earliest experimental demonstrations of quantum error correction were realized with various codes7,8,9,10,11,12,13,14,15. While such progress towards fault-tolerant quantum computing (FTQC) is promising, quantum computers in the coming generation, the early fault-tolerant quantum computers, would still be subject to noise at the logical level, and hence the error countermeasures developed for noisy intermediate-scale quantum (NISQ) devices, in particular the quantum error mitigation (QEM) techniques16,17,18,19,20,21,22,23, will remain essential to exemplify practical quantum advantage24,25,26,27,28,29,30. Meanwhile, there is a stark difference between (early) FTQC and NISQ regimes that is characterized by the Eastin–Knill theorem31; currently known FTQC schemes are based on universal gate sets that consist of discrete gates. This indicates that the gate synthesis yields coherent logical error whose effect is comparable to incoherent logical errors, even when we avoid all the coherent errors in the physical layer using tailored error correcting codes32,33,34.

In contrast to incoherent errors which inevitably necessitate entropy reduction via measurement and feedback35,36,37,38, there is no corresponding fundamental limitation for coherent errors. In fact, several previous works have found that algorithmic errors can be dealt with more efficiently than naive expectation39,40,41,42,43,44. It was pointed out by refs. 39,40 that, when one has access to a Pauli rotation exposed to over and under rotations, we can simply take a classical mixture of two to achieve quadratic suppression of the error. Such findings have invoked the proposal of a mixed synthesis scheme that approximately halves the consumption of magic gates under single-qubit unitary synthesis42,44. It must be noted that these existing works merely focus on the accuracy of the mixed synthesis, while one must take care of the compatibility between other error countermeasures to further suppress the logical errors. This is prominent when one desires to obtain an unbiased estimator via the QEM, which requires a deep knowledge of the error channel. To our knowledge, however, there is no firm understanding of the remnant error channel of gate synthesis, nor an attempt to control its profile.

In this work, we make a first step to fill this gap by introducing a notion of error crafting, i.e., performing the mixed synthesis that results in a remnant error channel with a desired property, for single-qubit unitaries synthesized under the framework of Clifford+T formalism. We rigorously prove that one can design a synthesis protocol that ensures the remnant error is constrained to Pauli error, which is crucial to perform efficient error mitigation techniques16,17,25. We further provide numerical evidence that, in the case of Pauli rotation gates, one can reliably manipulate the remnant error to be biased. This allows us to perform error detection at the logical level, which achieves quadratically small sampling overhead compared to the existing lower bound of sample complexity that does not rely on mid-circuit measurement36. We furthermore extend our framework to perform error crafting using CPTP channels obtained from error correction at the logical layer, and show that the remnant error can be suppressed up to cubic order. As a result, we can implement Pauli rotation gates of accuracy ε with T-count of \({\log }_{2}(1/\varepsilon )\) up to ε = 10−9, which is expected to be sufficient for various medium-scale FTQC beyond state-of-the-art classical computation26,27,28,30.

We remark that the operation of twirling shares the spirit, since it also transforms a noise channel into another channel with better-known properties via randomized gate compilation. However, there are two severe limitations in twirling: first, it agnostically smears out the characteristics of the channel, and second, it cannot ensure the noise maps are stochastic when one considers non-Clifford operations beyond the third level of Clifford hierarchy (see Table 1 and Supplementary Note S1 for details). Note that existing works on randomized compiling have reported suppression of unknown noise41,45,46, including both stochastic and coherent ones, while we are not aware of any work that guarantees the structure of the noise channel for general SU(2) gates. This is in sharp contrast to our work, which fully utilizes the information on the error profile of general unitary synthesis that can be characterized completely via classical computation. Stochastic noise associated with the synthesized gates is not within the scope of error crafting.

Results

Unitary, mixed, and error-crafted synthesis

We aim to implement a target single-qubit unitary \(\hat{U}\) with its channel representation given by \(\hat{{\mathcal{U}}}\). We hereafter distinguish the unitaries before and after synthesis by the presence and absence of a hat. Due to the celebrated Eastin-Knill’s theorem31, there is no fault-tolerant implementation of continuous gate sets, and therefore, we cannot exactly implement the target in general. We alternatively aim to approximate \(\hat{U}\) by decomposing it to a sequence of implementable operations. Such a task is called gate synthesis.

One of the most common approaches for gate synthesis is the unitary synthesis, namely, to decompose the target unitary into a sequence of implementable unitary gate sets. For instance, unitary synthesis into the Clifford+T gate set is known to be possible with classical computation time of \(O({\rm{polylog}}(1/\epsilon ))\) for arbitrary single-qubit Pauli rotation, assuming a factoring oracle47 and O(poly(1/ϵ)) for a general SU(2) gate48,49. Another measure for the efficiency of synthesis is the number of T gates, or the T-count, since T gates require cumbersome procedures such as magic state distillation and gate teleportation. In this regard, the existing methods nearly saturates the information-theoretic lower bound regarding the T-count of \(3{\log }_{2}(1/\epsilon )\) except for rare exceptions that require \(4{\log }_{2}(1/\epsilon )\)47,48,49,50.

We may also consider mixed synthesis, which takes a classical mixture of several different outputs from the unitary synthesis algorithm. Concretely, we generate a set of slightly shifted unitaries {Uj} which are ϵ-close approximations of the target unitary \(\hat{U}\) in terms of diamond distance as \({d}_{\diamond }(\hat{{\mathcal{U}}},{{\mathcal{U}}}_{j})\le \epsilon\) (see Supplementary Note S2 for the definition of diamond distance). It is known that the mixed synthesis allows quadratic suppression of the error, when we appropriately generate a set of synthesized unitaries \(\{{{\mathcal{U}}}_{j}\}\) and choose the probability distribution over them:

Lemma 1

(informal44) Let \(\hat{{\mathcal{U}}}\) be a target unitary channel with \(\{{{\mathcal{U}}}_{j}\}\) constituting its ϵ-net in terms of the diamond distance. Then, one can find the optimal weight {pj} such that the diamond distance is bounded as

by solving the following minimization problem via semi-definite programming:

As an extension of existing synthesis techniques, here we propose error-crafted synthesis, or error crafting. In short, this can be understood as constraining the remnant error of the synthesis, depending on the subsequent error countermeasure (such as QEM or error detection) one wishes to perform. We formally define the remnant error channel as

where Pa ∈ {I, X, Y, Z} and {χab} gives the chi representation of the remnant error. We also allow the implementable channel to be a non-unitary CPTP map as {Λj}, which we find to be useful when we incorporate measurement and feedback as discussed later. The aim of the crafted synthesis is to control {χab} by optimizing the probability distribution {pj} for appropriately generated {Λj}.

Let us remark that we require the synthesis protocol to be distinct from the QEM stage, in the sense that we do not allow synthesis to increase the sampling overhead, the multiplication factor in the number of circuit executions. Also, we require that the gate complexity is nearly homogeneous even if we include feedback operations, in order to prevent a situation where parallel application of multiple synthesized channels is stalled due to a fallback scheme42,51.

Crafting remnant error to be Pauli channel

While the quadratic suppression (1) by mixed synthesis is already beneficial for practical quantum computing, the performance of many error counteracting protocols can be enhanced when we craft the remnant error \({{\mathcal{E}}}_{{\rm{rem}}}\). For instance, let us consider the probabilistic error cancellation (PEC), which is one of the most well-known error mitigation techniques that estimate expectation values of physical observables by the quasi-probabilistic implementation of error channel inversion16,52. One can show that it suffices to take Clifford operations and Pauli initialization to constitute a universal set to invert arbitrary single-qubit error channels18,53, while the implementation is significantly simplified when \({{\mathcal{E}}}_{{\rm{rem}}}\) is a Pauli channel. This is because the PEC can be performed merely via updates on Pauli frames, which is purely done by classical processing of stabilizer measurements25. As another example, when we consider the rescaling technique under white-noise approximation54,55, which is a provably cost-optimal way of error mitigation, we can drastically improve the accuracy of the approximation when the errors are free from coherent components (see Supplementary Note S6 for details).

In this regard, we make a further step and ask the following question: can we guarantee both quadratic error suppression and success of crafting the remnant error to be Pauli channel? This is equivalent to solving the following optimization problem:

where χaa ≥ 0 is required for all a. We emphasize that this cannot be achieved by naively applying twirling techniques, since randomization for coherent errors following non-Clifford unitary demands non-Clifford operations, which are not error-free in FTQC (see Supplementary Note S1. Our strategy is to prepare shift unitaries \({\{{{\mathcal{V}}}_{j}^{c\epsilon }\}}_{j}\) that can be used to generate a set of cϵ-close unitaries such that the feasibility of the minimization problem (4) is guaranteed, even when unitary synthesis induces error of ϵ. By explicitly constructing such a set of shift unitaries, we rigorously answer the above-raised question as follows:

Theorem 1

There exist shift factor c, a positive number ϵ0, and a set of shift unitaries \({\{{{\mathcal{V}}}_{j}^{c\epsilon }\}}_{j = 1}^{7}\) such that, for any given single-qubit unitary \(\hat{{\mathcal{U}}}\) and for any ϵ ∈ (0, ϵ0], if we synthesize the shifted target unitaries to obtain \(\{{{\mathcal{U}}}_{j}\}=\{{\mathcal{A}}({{\mathcal{V}}}_{j}^{c\epsilon }\circ\; \hat{{\mathcal{U}}})\}\) so that \({d}_{\diamond }({{\mathcal{V}}}_{j}^{c\epsilon }\circ \;\hat{{\mathcal{U}}},{{\mathcal{U}}}_{j})\le \epsilon\) is satisfied under the synthesis algorithm \({\mathcal{A}}\), then there exists a mixture of \(\{{{\mathcal{U}}}_{j}\}\) that induces a Pauli channel as the effective synthesis error, with the accuracy being

Remarkably, this theorem states that we can craft the error without assuming anything but the accuracy for the synthesis algorithm \({\mathcal{A}}\). It is also worth noting that the minimization problem (4) can be solved by the linear programming.

To prove Theorem 1, we explicitly construct the shift unitaries \({\{{{\mathcal{V}}}_{j}^{c\epsilon }\}}_{j}\), and show that the feasibility of the solution is robust even under additional synthesis error of ϵ. Once such a solution is ensured, the upper bound of Eq. (5) follows directly from the formulation via the minimization over diamond distance and the fact that \({\{{{\mathcal{U}}}_{j}\}}_{j = 1}^{7}\) is (c + 1)ϵ-close to \(\hat{{\mathcal{U}}}\) with respect to the diamond distance. Also, the lower bound follows from the fact that the diamond distance between the compiled shifted unitaries \(\{{{\mathcal{U}}}_{j}\}\) and the target unitary \(\hat{{\mathcal{U}}}\) is at least (c−1)ϵ. We guide readers to Supplementary Note S7 for details of the proof.

Since the theorem only states the existence of finite c, we rely on numerical simulation to verify the practical usage with finite c values. For this purpose, we synthesize a single-qubit Haar random unitary gate by first performing the axial decomposition into three Pauli rotations, each of which is passed to the synthesis algorithm proposed by Ross and Selinger47. As shown in Fig. 1a, the mixed synthesis indeed yields error-bounded solutions that achieve quadratic suppression compared to the unitary synthesis. Meanwhile, we find that the Pauli constraint is violated when we take small shift factors c. This does not contradict Theorem 1, since the theorem only states the existence of c that always yields successful results. It must be noted that, as shown in Fig. 1b, c, the occurrence of such a violation is suppressed exponentially by increasing the value of c. We observe that it suffices to take c ~ 3.5, 4.5 to yield feasible solutions with failure probability of 10−2, 10−3, respectively, and naturally deduce that c ~ 5.5, 6.5 is required to reach 10−4, 10−5. We remark that, while we have employed the axial decomposition of the SU(2) gates for the results shown here, we observe similar suppression when we utilize a direct synthesis algorithm56.

a Diamond distance \({d}_{\diamond }(\hat{{\mathcal{U}}},{{\mathcal{U}}}_{{\rm{synth}}})\) between the target single-qubit Haar random unitary \(\hat{{\mathcal{U}}}\) and the synthesized channel \({{\mathcal{U}}}_{{\rm{synth}}}:={\sum }_{j}{p}_{j}{{\mathcal{U}}}_{j}\). The black real line indicates the results from unitary synthesis by the Ross-Selinger algorithm, while the filled dots are results from mixed synthesis with shift factors of c = 2, 3, 5, 7. When we increase the number of synthesized unitaries by a factor of R = 3 (see main text for detailed definition) for c = 7, shown by unfilled triangles, the remnant synthesis error is suppressed below the bound in Eq. (5) and approaches the value of ϵ2, which matches the upper bound for the non-constrained case as in Eq. (1). The plots are averaged over 200 random instances of target unitaries. b Surface plot of failure rate pfail of mixed synthesis under the Pauli constraint, averaged over 200 instances for ϵ = 10−4. Scaling with c and R are shown in (c), (d), where the number of instances is 10,000 and 2000, respectively.

Since increasing the shift factor c increases the prefactor of the remnant error by c2, we find it beneficial to introduce another practical strategy that enhances the feasibility of the solution. Here we provide a simple yet powerful technique; by generating the shift unitaries for R different shift factors c/R, 2c/R, . . . , c and solving the problem (4) with R-fold larger number of basis set, we can both suppress the failure of error-crafted synthesis (see Fig. 1b, d) and the remnant error. As shown in Fig. 1a, when we take c = 7 and R = 3, we find that the diamond distance is suppressed as ϵ2 for a broad range of the synthesis accuracy ϵ, which is a significant improvement from the case of R = 1 with ~c2ϵ2. Note that this is extremely beneficial when we wish to eliminate such remnant errors using QEM methods. To be concrete, the sampling overhead is given as (1+4p)L under error rate of p with L gates when one employs the PEC method, and hence the reduction of the remnant error from prem ~ c2ϵ2 to prem ~ ϵ2 results in exponential difference with L. For instance, when we implement {1, 2, 3} × 108 rotation Pauli gates with ϵ = 10−5, the sampling overhead is reduced by factors of 6.8, 47, and 317, respectively.

We remark that crafting is actually essential to guarantee the remnant channel to be a Pauli channel. In Fig. 2, we compare the remnant errors in crafted and uncrafted mixed synthesis. We find that, as expected, the magnitude of the remnant error is slightly smaller when we do not craft it. However, we can see there is a drastic difference in the non-Pauli component. Here, we calculate the magnitude of the error that persists even after we eliminate the Pauli component as \(\mathop{\min }\limits_{{\mathcal{R}}}{d}_{\diamond }({\mathcal{R}}\circ\; {{\mathcal{E}}}_{{\rm{rem}}},{\mathcal{I}})\), where \({\mathcal{R}}\) is minimized over the set of trace-preserving maps that inverts Pauli error. We can see that the non-Pauli component in uncrafted synthesis remains as O(ϵ2), while in the crafted synthesis the magnitude is suppressed below 10−13. We attribute this residual to the relaxation of equality constraint into inequality, which was performed to enhance the stability of the numerical solver (see Supplementary Note S3). While we show the result for Z rotation here, we have confirmed that similar results can be obtained for general SU(2) gates as well. As summarized in Table 2, such a guarantee allows us to perform PEC using the Pauli frame.

a Box plots are provided for the magnitude of remnant errors of 100 random instances of Z rotation gate, with unitary synthesis done for ϵ = 10−4. The left two box plots show \({d}_{\diamond }({{\mathcal{E}}}_{{\rm{rem}}},{\mathcal{I}})\) with and without crafting for Pauli error, and the right two box plots indicate the magnitude of the non-Pauli contribution. b Scaling of the remnant errors with ϵ. In both panels, shift unitaries are generated with c = 3, R = 5.

As another practical remark, note that the number of bases with nonzero probability (\({\sum }_{{p}_{j}\ne 0}1\)) is always upper-bounded by 10. Hence, the actual memory footprint of the transpiled circuit is comparable to ordinary mixed synthesis algorithms.

Crafting remnant error to be detectable

If one chooses to employ the PEC method as the QEM method for FTQC, it suffices to guarantee only the feasibility under the Pauli constraint. Indeed, the PEC method is powerful in the sense that one may perform unbiased estimation when the error channel is precisely known. However, we find that the remnant errors can be counteracted much more effectively by utilizing the fact that they can be characterized completely by classical computation. For instance, we may wish to craft local depolarizing errors, since many limits and performance of quantum algorithms, as well as QEM methods, are analyzed under the assumption of the local depolarizing noise19,35,38,57,58. We may alternatively wish to craft the remnant errors to be some biased Pauli noise. We find that this is extremely beneficial for the case of the Pauli rotation gates. Namely, we can perform error detection or correction in the logical layer, which reduces the sampling overhead to the extent that QEM methods designed for general channels cannot achieve.

First, let us discuss the crafting of the depolarizing channel. Following a similar strategy as in Theorem 1, we can mathematically prove that there exists a set of shift unitaries \(\{{{\mathcal{V}}}_{j}^{c\epsilon }\}\) such that we can achieve quadratic suppression of error under the depolarizing constraint, with the sole difference being that the number of shift unitaries is 9 instead of 7. The formal statement and the proof are provided in Supplementary Note S7. Our numerical simulation also shows similar favorable properties as seen in the case of Pauli constraint (See Supplementary Note S3).

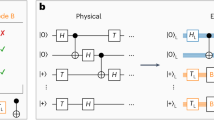

Next, let us consider crafting the remnant error to be biased. In particular, we focus on the Pauli Z rotation gate and aim to bias the error to be XY error, since it can be detected using a single ancilla qubit with less sampling overhead than the lower bound for QEM methods that do not rely on mid-circuit measurement36 (concrete circuit structure provided in Fig. 3). While we have not found a guaranteed set of shift unitaries, we find that the nine shift unitaries for the depolarizing noise are of practical use, if we allow violation of the constraint as pz ≤ 0.01p where p: = px + py + pz (see Supplementary Notes S3 for details).

Circuit structure for a error detection and b logical error correction for Pauli Z rotation gate Rz with remnant error of \({{\mathcal{E}}}_{{\rm{rem}}}\). We may further combine with the PEC method, for which the Pauli operation \({\mathcal{P}}\) with dotted square is executed virtually via updating the Pauli frame. Note that the feedback operation in (b) is also done via the Pauli frame.

The success of error crafting is highlighted in Fig. 4. As can be seen from Fig. 4a, while the rate of Pauli errors \((\frac{{p}_{x}}{p},\frac{{p}_{y}}{p},\frac{{p}_{z}}{p})\) is distributed quite homogeneously if we do not impose any constraint on the error profile, we find that the constraints can be reflected with high accuracy. We verify that px = py = pz is satisfied up to the order of machine precision for the depolarizing constraint, while for the XY-biased noise, we find that we cannot completely eliminate the Z error; there is a small residual component of pz = O(ϵ3) even if we allow the XY-biased noise to consist of non-unital components. We also attempted to craft X-biased noise, but it did not succeed in most instances.

Here we display the distribution of error rate ratio \(({q}_{x},{q}_{y},{q}_{z}):=(\frac{{p}_{x}}{p},\frac{{p}_{y}}{p},\frac{{p}_{z}}{p})\) on a plane qx + qy + qz = 1, where pa: = χaa(a ∈ {x, y, z}) is the rate of each Pauli channel in \({{\mathcal{E}}}_{{\rm{rem}}}\) and p: = px + py + pz = O(ϵ2) corresponds to the total error rate. Note that here we show results whose violation of the constraints is below threshold values (see Supplementary Notes S3 for details). The unitary synthesis is done for ϵ = 10−4 with shift factor c = 2.0, 5.0 for depolarizing and XY constraints, respectively.

Error crafting using CPTP maps

While we have considered the error crafting using synthesized unitaries {Uj}, we can also apply the framework to CPTP maps. As a demonstration, here we consider the target unitary \(\hat{U}\) to be a Pauli Z rotation, and constitute the set of implementable CPTP maps {Λj} as the channels of synthesized unitaries accompanied with entangled measurement and feedback as shown in Fig. 3b 59,60. We have numerically found that, the remnant error can be suppressed cubically small as ϵ3, as opposed to the quadratic suppression realized in the error crafting for unitaries. Since the optimal unitary synthesis yields T-count of \(3{\log }_{2}(1/\epsilon )+O(1)\), such an improvement allows us to synthesize a Pauli rotation gate with a T-count of \({\log }_{2}(1/\varepsilon )+O(1)\) on average. Compare this with the scaling of \(1.5{\log }_{2}(1/\varepsilon )\) realized by mixed synthesis, which achieve quadratic improvement in ε (see Fig. 5). We guide the readers to the Supplementary Note S4, S5 for a detailed discussion on the search for appropriate Λj.

The red, yellow, and blue regions indicate the achievable accuracy without any sampling overhead when we employ unitary, mixed, and error-crafted synthesis. The blue circles indicate the error solely from crafted synthesis for Rz(θ) with \(\theta \in {\{\frac{m\pi }{32}\}}_{m\ne 0{\rm{mod4}}}\) under various synthesis accuracy. Note that the total error, combined with hardware noise, is bounded by the chained black line, which indicates the contribution from noise in T gates. Here we choose error rate of 10−11 per T gate. The dotted red, yellow, and green lines are given by the empirical T-count of \(3{\log }_{2}(1/\varepsilon )\), \(1.5{\log }_{2}(1/\varepsilon )\), and \({\log }_{2}(1/\varepsilon )\), respectively, and the real lines indicate the total error.

Even if the Z error cannot be eliminated completely, such an error crafting drastically alters the sampling overhead. By performing the error detection operation as shown in Fig. 3a, we can mitigate Pauli X and Y errors with a sampling overhead of γXY = 1 + px + py, which is even below the lower bound of QEM sampling overhead that does not rely on mid-circuit measurement36. While the Z error is undetectable and hence we shall rely on other QEM methods such as PEC or rescaling with overhead of γZ = 1 + αpz, the total sampling overhead is γtot = γXYγZ ~ 1 + px + py + αpz~1 + ϵ2. When we perform QEM for L gates, the total sampling overhead \({\gamma }_{{\rm{tot}}}^{L}\) is quartically small compared to that of PEC.

An intuitive understanding of the reduction of the T-count can be obtained from a geometric interpretation. Let us first briefly describe the standard volume argument61 for SU(2) synthesis to yield scaling of \(3{\log }_{2}(1/\varepsilon )+O(1)\), and then proceed to explain the improved scaling of \({\log }_{2}(1/\varepsilon )+O(1)\). We can interpret the problem of designing a synthesis algorithm, i.e., ensuring any d-dimensional unitary to be approximated by accuracy of ε, as packing ϵ-ball into the manifold of SU(d). The volume of ε-ball in (d2−1)-dimensional space is \(O({\varepsilon }^{{d}^{2}-1}),\) in particular V = O(ε3) for SU(2). Hence, in order to cover the entire space, we need at least O(1/V) = O(1/ε3) unique unitaries. Note that any Clifford+T gate can be expressed uniquely by the canonical form proposed by Matsumoto and Amano62. Specifically, the number of unique Clifford+T operator with T-count of t is 192 ⋅ (3 ⋅ 2t − 2). We therefore deduce that the lower bound of T-count scales as \(3{\log }_{2}(1/\varepsilon )+O(1)\). It has been numerically verified that this bound is indeed nearly saturated by a direct search algorithm56, which reflects the fact that the grid points corresponding to Clifford+T unitary are distributed homogeneously within the manifold so that the gate set quickly mimics the Haar unitary ensemble63.

When we perform the mixed CPTP synthesis, since we can correct the coherent error of X rotation via the feedback operation, we may allow it to be arbitrarily large. This effectively projects out one of the dimensions of the manifold to be covered. Correspondingly, the volume of the ball is regarded as V = O(ε2). From the volume argument, this leads to the T-count of \(2{\log }_{2}(1/\varepsilon )+O(1)\) for the synthesis of unitaries to be included in the mixture. By combining with the fact that appropriate mixed synthesis allows quadratic suppression of error and hence reduces the T-count by a factor of two, we arrive at the scaling of \({\log }_{2}(1/\varepsilon )+O(1)\).

Let us briefly comment on the classical precomputation time of crafted synthesis. Our results in Fig. 5 exploits the direct search algorithm for SU(2) gate synthesis whose computational complexity scales as O(1/ϵ) on average56. Considering that currently known unitary synthesis algorithms for Rz gates based on number-theoretic approach47,64 or repeat-until-success circuits42,51 yield nearly optimal gate sequence with computational complexity of \(O({\rm{polylog}}(1/\epsilon ))\), the complexity of direct search algorithms seems to be a significant overhead. Meanwhile, we observe that the actual computation time per synthesis is observed to be milliseconds for the accuracy regime we have investigated. Considering that such computations can be embarrassingly parallelized, and also that number of rotation gates for early FTQC circuits is of 104 for quantum dynamics simulation30,65 and 106 for ground state energy simulation66, we envision that classical computation time is not a bottleneck for such applications.

Last but not least, while we have exclusively discussed the error and sampling overhead only for the synthesis error, it must be kept in mind that, in reality, there is also incoherent noise that indirectly limits the synthesis accuracy. As can be seen from Fig. 5, one shall aim for the sweet spot where the total error is minimized. While we have displayed the case when we have designed the FTQC to contribute the majority of logical errors to magic state distillation, we may flexibly change the scheme to introduce errors in Clifford operations as well.

Discussion

In this work, we have proposed a scheme for error-corrected synthesis of single-qubit unitaries under the framework of Clifford+T formalism. We have proven that we can guarantee the quadratic suppression of the unitary synthesis error even when we constrain the remnant error to be Pauli and a depolarizing channel. Furthermore, for the case of Pauli rotation gates, we have numerically shown that error crafting can yield biased Pauli noise such that sampling overhead to mitigate the errors can be suppressed quadratically compared to the existing techniques. We have also found that error crafting for CPTP maps that incorporate measurement and feedback operations achieves cubic suppression of the error up to accuracy of 10−9.

Numerous future directions are envisioned. First, it is essential to determine whether error crafting is possible for the synthesis of multiqubit unitaries. Combined with the fact that the error can potentially be suppressed exponentially smaller with the qubit count for multiqubit case44, it is crucial to extend the framework proposed in this work to perform practical quantum computation. Second, it is intriguing in terms of resource-theoretic argument to assess the probabilistic transformability between channels. While this has been studied for state transformation in the context of magic state or entanglement distillation67, the argument on quantum channels is left as an interesting open question. Third, it is an intriguing open question whether there is a lower bound on the computational complexity to perform error-crafted synthesis.

Data availability

Data and codes for the work are available via GitHub repository68.

References

Shor, P. W. Scheme for reducing decoherence in quantum computer memory. Phys. Rev. A 52, R2493 (1995).

Gottesman, D. Stabilizer codes and quantum error correction. arXiv preprint quant-ph/9705052 (1997).

Shor, P. W. Polynomial-time algorithms for prime factorization and discrete logarithms on a quantum computer. SIAM Rev. 41, 303–332 (1999).

Abrams, D. S. & Lloyd, S. Quantum algorithm providing exponential speed increase for finding eigenvalues and eigenvectors. Phys. Rev. Lett. 83, 5162–5165 (1999).

Aspuru-Guzik, A., Dutoi, A. D., Love, P. J. & Head-Gordon, M. Simulated quantum computation of molecular energies. Science 309, 1704–1707 (2005).

Biamonte, J. et al. Quantum machine learning. Nature 549, 195 (2017).

Sundaresan, N. et al. Demonstrating multi-round subsystem quantum error correction using matching and maximum likelihood decoders. Nat. Commun. 14, 2852 (2023).

Egan, L. et al. Fault-tolerant control of an error-corrected qubit. Nature 598, 281–286 (2021).

Ryan-Anderson, C. et al. Realization of real-time fault-tolerant quantum error correction. Phys. Rev. X 11, 041058 (2021).

Bluvstein, D. et al. Logical quantum processor based on reconfigurable atom arrays. Nature 626, 58–65 (2024).

Livingston, W. P. et al. Experimental demonstration of continuous quantum error correction. Nat. Commun. 13, 2307 (2022).

Satzinger, K. J. et al. Realizing topologically ordered states on a quantum processor. Science. 374, 1237–1241 (2021).

Bluvstein, D. et al. A quantum processor based on coherent transport of entangled atom arrays. Nature 604, 451–456 (2022).

Zhao, Y. et al. Realization of an error-correcting surface code with superconducting qubits. Phys. Rev. Lett. 129, 030501 (2022).

Acharya, R. et al. Suppressing quantum errors by scaling a surface code logical qubit. Nature 614, 676–681 (2023).

Temme, K., Bravyi, S. & Gambetta, J. M. Error mitigation for short-depth quantum circuits. Phys. Rev. Lett. 119, 180509 (2017).

Li, Y. & Benjamin, S. C. Efficient variational quantum simulator incorporating active error minimization. Phys. Rev. X 7, 021050 (2017).

Endo, S., Benjamin, S. C. & Li, Y. Practical quantum error mitigation for near-future applications. Phys. Rev. X 8, 031027 (2018).

Koczor, B. Exponential error suppression for near-term quantum devices. Phys. Rev. X 11, 031057 (2021).

Huggins, W. J. et al. Virtual distillation for quantum error mitigation. Phys. Rev. X 11, 041036 (2021).

Yoshioka, N. et al. Generalized quantum subspace expansion. Phys. Rev. Lett. 129, 020502 (2022).

van den Berg, E., Minev, Z. K. & Temme, K. Model-free readout-error mitigation for quantum expectation values. Phys. Rev. A 105, 032620 (2022).

Strikis, A., Qin, D., Chen, Y., Benjamin, S. C. & Li, Y. Learning-based quantum error mitigation. PRX Quantum 2, 040330 (2021).

Piveteau, C., Sutter, D., Bravyi, S., Gambetta, J. M. & Temme, K. Error mitigation for universal gates on encoded qubits. Phys. Rev. Lett. 127, 200505 (2021).

Suzuki, Y., Endo, S., Fujii, K. & Tokunaga, Y. Quantum error mitigation as a universal error reduction technique: applications from the nisq to the fault-tolerant quantum computing eras. PRX Quantum 3, 010345 (2022).

Yoshioka, N., Okubo, T., Suzuki, Y., Koizumi, Y. & Mizukami, W. Hunting for quantum-classical crossover in condensed matter problems. npj Quantum Inf. 10, 45 (2024).

Babbush, R. et al. Encoding electronic spectra in quantum circuits with linear t complexity. Phys. Rev. X 8, 041015 (2018).

Lee, J. et al. Even more efficient quantum computations of chemistry through tensor hypercontraction. PRX Quantum 2, 030305 (2021).

Sakamoto, K. et al. End-to-end complexity for simulating the Schwinger model on quantum computers. Quantum 8, 1474 (2024).

Beverland, M. E. et al. Assessing requirements to scale to practical quantum advantage. arXiv preprint arXiv:2211.07629 (2022).

Eastin, B. & Knill, E. Restrictions on transversal encoded quantum gate sets. Phys. Rev. Lett. 102, 110502 (2009).

Zanardi, P. & Rasetti, M. Noiseless quantum codes. Phys. Rev. Lett. 79, 3306 (1997).

Alber, G. et al. Stabilizing distinguishable qubits against spontaneous decay by detected-jump correcting quantum codes. Phys. Rev. Lett. 86, 4402 (2001).

Ouyang, Y. Avoiding coherent errors with rotated concatenated stabilizer codes. npj Quantum Inf. 7, 87 (2021).

Aharonov, D., Ben-Or, M., Impagliazzo, R. & Nisan, N. Limitations of noisy reversible computation http://arxiv.org/abs/quant-ph/9611028. (1996).

Tsubouchi, K., Sagawa, T. & Yoshioka, N. Universal cost bound of quantum error mitigation based on quantum estimation theory. Phys. Rev. Lett. B 131, 210601 (2023).

Takagi, R., Tajima, H. & Gu, M. Universal sampling lower bounds for quantum error mitigation. Phys. Rev. Lett. 131, 210602 (2023).

Quek, Y., França, D. S., Khatri, S., Meyer, J. J. & Eisert, J. Exponentially tighter bounds on limitations of quantum error mitigation. Nat. Phys. 20, 1648 (2024).

Hastings, M. B. Turning gate synthesis errors into incoherent errors. Quantum Info Comput. 17, 488–494 (2017).

Campbell, E. Shorter gate sequences for quantum computing by mixing unitaries. Phys. Rev. A 95, 042306 (2017).

Wallman, J. J. & Emerson, J. Noise tailoring for scalable quantum computation via randomized compiling. Phys. Rev. A 94, 052325 (2016).

Kliuchnikov, V., Lauter, K., Minko, R., Paetznick, A. & Petit, C. Shorter quantum circuits via single-qubit gate approximation. Quantum 7, 1208 (2023).

Akibue, S., Kato, G. & Tani, S. Probabilistic unitary synthesis with optimal accuracy. ACM Transactions on Quantum Computing 5, 1 (2024).

Akibue, S., Kato, G. & Tani, S. Probabilistic state synthesis based on optimal convex approximation. npj Quantum Inf. 10, 1–9 (2024).

P. Santos, J., Bar, B. & Uzdin, R. Pseudo twirling mitigation of coherent errors in non-Clifford gates. npj Quantum Inf. 10, 100 (2024).

Odake, T. et al. Robust error accumulation suppression. arXiv preprint arXiv:2401.16884 (2024).

Ross, N. J. & Selinger, P. Optimal ancilla-free clifford+t approximation of z-rotations. Quantum Info Comput. 16, 901–953 (2016).

Fowler, A. G. Constructing arbitrary steane code single logical qubit fault-tolerant gates. Quantum Info Comput. 11, 867–873 (2011).

Bocharov, A. & Svore, K. M. Resource-optimal single-qubit quantum circuits. Phys. Rev. Lett. 109, 190501 (2012).

Kliuchnikov, V., Maslov, D. & Mosca, M. Fast and efficient exact synthesis of single-qubit unitaries generated by clifford and t gates. Quantum Info Comput. 13, 607–630 (2013).

Bocharov, A., Roetteler, M. & Svore, K. M. Efficient synthesis of universal repeat-until-success quantum circuits. Phys. Rev. Lett. 114, 080502 (2015).

van den Berg, E., Minev, Z. K., Kandala, A. & Temme, K. Probabilistic error cancellation with sparse Pauli-Lindblad models on noisy quantum processors. Nat. Phys. 19, 1116–1121 (2023).

Takagi, R. Optimal resource cost for error mitigation. Phys. Rev. Res. 3, 033178 (2021).

Arute, F. et al. Quantum supremacy using a programmable superconducting processor. Nature 574, 505–510 (2019).

Dalzell, A. M., Hunter-Jones, N. & Brandão, F. G. Random quantum circuits transform local noise into global white noise. Commun. Math. Phys. 405, 78 (2024).

Morisaki, H., Akibue, S. & Fujii, K. Optimal ancilla-free clifford+t compilation of single qubit unitary. In preparation (2024).

Koczor, B. The dominant eigenvector of a noisy quantum state. N. J. Phys. 23, 123047 (2021).

Cai, Z. et al. Quantum error mitigation. Rev. Mod. Phys. 95, 045005 (2023).

Gonzales, A., Shaydulin, R., Saleem, Z. H. & Suchara, M. Quantum error mitigation by Pauli check sandwiching. Sci. Rep. 13, 2122 (2023).

Debroy, D. M. & Brown, K. R. Extended flag gadgets for low-overhead circuit verification. Phys. Rev. A 102, 052409 (2020).

Harrow, A. W., Recht, B. & Chuang, I. L. Efficient discrete approximations of quantum gates. J. Math. Phys. 43, 4445–4451 (2002).

Matsumoto, K. & Amano, K. Representation of quantum circuits with clifford and π/8 gates. arXiv preprint arXiv:0806.3834 (2008).

Haferkamp, J. et al. Efficient unitary designs with a system-size independent number of non-clifford gates. Commun. Math. Phys. 397, 995–1041 (2023).

Kliuchnikov, V., Maslov, D. & Mosca, M. Practical approximation of single-qubit unitaries by single-qubit quantum clifford and t circuits. IEEE Trans. Comput. 65, 161–172 (2015).

Campbell, E. T. Early fault-tolerant simulations of the hubbard model. Quantum Sci. Technol. 7, 015007 (2021).

Kivlichan, I. D. et al. Improved fault-tolerant quantum simulation of condensed-phase correlated electrons via trotterization. Quantum 4, 296 (2020).

Regula, B. Probabilistic transformations of quantum resources. Phys. Rev. Lett. 128, 110505 (2022).

Yoshioka, N. error-crafting. https://github.com/quantum-programming/error-crafting GitHub Repository (2024).

Mitsuhashi, Y. & Yoshioka, N. Clifford group and unitary designs under symmetry. PRX Quantum 4, 040331 (2023).

Tsubouchi, K., Mitsuhashi, Y., Sharma, K. & Yoshioka, N. Symmetric clifford twirling for cost-optimal error mitigation in early fault-tolerant quantum computing. arXiv:2405.07720 (2024).

Morvan, A. et al. Phase transitions in random circuit sampling. Nature 634, 328–333 (2024).

Acknowledgements

We thank Suguru Endo, Ali Javadi-Abhari, Yuuki Tokunaga, and Kunal Sharma for fruitful discussions. This work was supported by JST CREST Grant Number JPMJCR23I4, JST Moonshot R&D Grant Number JPMJMS2061, and MEXT Q-LEAP Grant No. JPMXS0120319794, and No. JPMXS0118068682. N.Y. wishes to thank JST PRESTO No. JPMJPR2119, JST ERATO Grant Number JPMJER2302, JST Grant Number JPMJPF2221, and the support from IBM Quantum. S.A. is supported by JST, PRESTO Grant no.JPMJPR2111. This work is supported by the MEXT Quantum Leap Flagship Program (MEXT Q-LEAP) Grant No. JP- MXS0118067394 and JPMXS0120319794, JST COI- NEXT Grant No. JPMJPF2014. K.T. is supported by the World-leading Innovative Graduate Study Program for Materials Research, Information, and Technology (MERIT-WINGS) of the University of Tokyo and JSPS KAKENHI Grant No. JP24KJ0857.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

N.Y. conceived the idea. N.Y., S.A., K.T., and Y.S. performed the theoretical analysis. N.Y. and H.M. developed the numerical codes. All authors contributed to the scientific discussion and writing of the paper.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

Y.S. and S.A. own stock/options in Nippon Telegraph and Telephone. Y.S. owns stock/options in QunaSys Inc.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Yoshioka, N., Akibue, S., Morisaki, H. et al. Error crafting in mixed quantum gate synthesis. npj Quantum Inf 11, 95 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41534-025-01032-x

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41534-025-01032-x

This article is cited by

-

Symmetric Clifford twirling for cost-optimal quantum error mitigation in early FTQC regime

npj Quantum Information (2025)