Abstract

Quantum neural networks (QNNs) require an efficient training algorithm to achieve practical quantum advantages. A promising approach is gradient-based optimization, where gradients are estimated by quantum measurements. However, QNNs currently lack general quantum algorithms for efficiently measuring gradients, which limits their scalability. To elucidate the fundamental limits and potentials of efficient gradient estimation, we rigorously prove a trade-off between gradient measurement efficiency (the mean number of simultaneously measurable gradient components) and expressivity in deep QNNs. This trade-off indicates that more expressive QNNs require higher measurement costs per parameter for gradient estimation, while reducing QNN expressivity to suit a given task can increase gradient measurement efficiency. We further propose a general QNN ansatz called the stabilizer-logical product ansatz (SLPA), which achieves the trade-off upper bound by exploiting the symmetric structure of the quantum circuit. Numerical experiments show that the SLPA drastically reduces the sample complexity needed for training while maintaining accuracy and trainability compared to well-designed circuits based on the parameter-shift method.

Similar content being viewed by others

Deep learning is a breakthrough technology that has a significant impact on a variety of fields1. In deep learning, neural networks are trained to approximate unknown target functions and represent input-output relationships in various tasks, such as image recognition2, natural language processing3, predictions of protein structure4, and quantum state approximation5. Behind the great success of deep learning lies an efficient training algorithm equipped with backpropagation6,7. Backpropagation allows us to efficiently evaluate the gradient of an objective function at approximately the same computational cost as a single model evaluation, optimizing the neural network based on the evaluated gradient. This technique is essential for training large-scale neural networks with enormous parameters, including large language models3.

In analogy to deep learning, variational quantum algorithms (VQAs) have emerged as a promising technology for solving classically intractable problems, e.g., in quantum chemistry and physics8, optimization9, and machine learning10,11,12,13,14. In VQAs, a parameterized quantum circuit, called a quantum neural network (QNN) in the context of quantum machine learning (QML)15,16,17,18, is optimized by minimizing an objective function with quantum and classical computers19. As in classical neural networks, gradient-based optimization algorithms are effective for training QNNs, where gradients are estimated by quantum measurements. However, unlike classical models, efficient gradient estimation is challenging in QNNs because quantum states collapse upon measurement20. In fact, general QNNs lack an efficient gradient measurement algorithm that achieves the same computational cost scaling as classical backpropagation when only one copy of the quantum data is accessible at a time21. Instead, the gradient is usually estimated using the parameter-shift method12,22, where each gradient component is measured independently. This method is easy to implement but leads to a high measurement cost that is proportional to the number of parameters, which prevents QNNs from scaling up in near-term quantum devices without sufficient computational resources.

Despite the lack of general algorithms to achieve backpropagation scaling, a commuting block circuit (CBC) has recently been proposed as a well-structured QNN for efficient gradient estimation23,24. The CBC consists of B blocks containing multiple variational rotation gates, and the generators of rotation gates in two blocks are either all commutative or all anti-commutative. This specific structure allows us to estimate the gradient using only 2B − 1 types of quantum measurements, which is independent of the number of rotation gates in each block, potentially achieving the backpropagation scaling. Therefore, the CBC can be trained more efficiently than conventional QNNs based on the parameter-shift method.

Inspired by these developments, several key questions about gradient measurement in QNNs arise. What factor fundamentally limits gradient measurement efficiency in QNNs? More specifically, what is the theoretically most efficient QNN model for measuring gradients? The specific structure of CBC suggests that there is a trade-off for its high gradient measurement efficiency, but this remains unclear. Answering these questions is crucial not only for the theoretical understanding of efficient training in QNNs but also for the realization of practical QML.

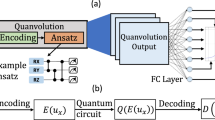

This work answers these questions for general QNNs. We first formulate gradient measurement efficiency in terms of the simultaneous measurability of gradient components, proving a general trade-off between gradient measurement efficiency and expressivity in a wide class of deep QNNs [Fig. 1a]. This trade-off implies that more expressive QNNs require higher measurement costs per parameter for gradient estimation, whereas the gradient measurement efficiency can be increased by reducing the QNN expressivity to suit a given task. Based on this trade-off, we further propose a general ansatz of CBC, the stabilizer-logical product ansatz (SLPA), as an optimal model for gradient estimation. This ansatz is inspired by the stabilizer code in quantum error correction25, exploiting the symmetric structure of the circuit to enhance gradient measurement efficiency [Fig. 1b]. Remarkably, the SLPA can reach the upper bound of the trade-off inequality, i.e., it enables gradient estimation with theoretically the fewest types of quantum measurements for a given expressivity. Owing to its symmetric structure, the SLPA can be applied to various problems involving symmetry, which are common in quantum chemistry, physics, and machine learning. As a demonstration, we consider the task of learning an unknown symmetric function. Numerical experiments show that the SLPA can drastically reduce the number of data samples needed for training without sacrificing accuracy and trainability compared to several QNNs based on the parameter-shift method. These results reveal the theoretical limits and possibilities of efficient training in parameterized quantum circuits, thus paving the way for realizing practical quantum advantages in various research fields related to VQAs, including QML.

a A trade-off relation between gradient measurement efficiency and expressivity. Any quantum model can only exist in the blue region. Gradient measurement efficiency, \({{\mathcal{F}}}_{{\rm{eff}}}\), is defined as the number of simultaneously measurable components in the gradient, and expressivity \({{\mathcal{X}}}_{\exp }\) is the dimension of the dynamical Lie algebra of the parameterized quantum circuit. The red circles denote the SLPA, where 2s gradient components can be measured simultaneously (i.e., \({{\mathcal{F}}}_{{\rm{eff}}}={2}^{s}\), s is an integer), reaching the upper bound of the trade-off inequality. b The circuit structure of SLPA. The generators of SLPA are constructed by taking the products of stabilizers and logical Pauli operators.

Results

Model, efficiency, and expressivity

We consider the following QNN on an n-qubit system:

where Gj is a Pauli operator in \({{\mathcal{P}}}_{n}={\{I,X,Y,Z\}}^{\otimes n}\), θ = (θ1, θ2, ⋯ ) are variational rotation angles, and L is the number of rotation gates. Let \({\mathcal{G}}={\{{G}_{j}\}}_{j = 1}^{L}\) be the set of generators. We also consider a cost function defined as the expectation value of a Pauli observable O:

where ρ is an input quantum state.

To reveal the theoretical limit of efficient gradient estimation, let us first define the simultaneous measurability of two different components in the gradient. The derivative of the cost function by θj is written as

where we have introduced a gradient operator Γj:

In other words, ∂jC is identical to the expectation value of the gradient operator Γj for the input state ρ. In quantum mechanics, two observables A and B can be simultaneously measured for any input state ρ if and only if [A, B] = 0. Therefore, we define the simultaneous measurability of two gradient components ∂jC and ∂kC as [Γj(θ), Γk(θ)] = 0 for all θ.

Based on this definition, we partition the gradient operators \({\{{\Gamma }_{j}\}}_{j = 1}^{L}\) into ML simultaneously measurable sets. In this partitioning, all operators in the same set are simultaneously measurable in the sense that they are mutually commuting. This partitioning enables us to estimate all gradient components using ML types of quantum measurements in principle. Thereby, we define gradient measurement efficiency for finite-depth QNNs as

where min(ML) is the minimum number of sets among all possible partitions. We also define the gradient measurement efficiency in the deep circuit limit:

In this definition, \({{\mathcal{F}}}_{{\rm{eff}}}\) indicates the mean number of simultaneously measurable components in the gradient. Therefore, the larger \({{\mathcal{F}}}_{{\rm{eff}}}\) is, the more efficiently the gradient can be measured. This work mainly focuses on the deep circuit limit, but our results also have implications for efficient gradient measurement in finite-depth QNNs.

Another key factor in this work is expressivity, which is crucial in understanding quantum circuits and realizing universal computation. In particular, whether a given class of quantum circuits can express all unitaries, i.e., whether it is universal, has been investigated in various contexts, such as fault-tolerant quantum computation26,27,28,29, quantum dynamics30,31,32, random quantum circuits33,34,35,36, and VQAs37,38,39, with and without symmetry constraints. Here, to quantify expressivity, we employ the dynamical Lie algebra (DLA)40,41,42. To this end, we consider the Lie closure \(i{{\mathcal{G}}}_{{\rm{Lie}}}={\left\langle i{\mathcal{G}}\right\rangle }_{{\rm{Lie}}}\), which is defined as the set of Pauli operators obtained by repeatedly taking the nested commutator between the circuit generators in \(i{\mathcal{G}}={\{i{G}_{j}\}}_{j = 1}^{L}\). The DLA is defined from \({{\mathcal{G}}}_{{\rm{Lie}}}\) as

which is the subspace of \({\mathfrak{su}}({2}^{n})\). The DLA characterizes which unitaries the QNN can express in the overparameterized regime of \(L\gtrsim \,\text{dim}\,({\mathfrak{g}})\). That is, \(U({\boldsymbol{\theta }})\in {e}^{{\mathfrak{g}}}\) for all θ43. Therefore, we define the QNN expressivity in the deep circuit limit as the dimension of the DLA:

For example, a hardware-efficient ansatz consisting of local Pauli rotations \({\mathcal{G}}={\{{X}_{j},{Y}_{j},{Z}_{j}{Z}_{j+1}\}}_{j = 1}^{n}\) has the DLA of \({{\mathcal{X}}}_{\exp }={4}^{n}-1\)38, indicating that this ansatz is universal and can express all unitaries in the deep circuit limit. Note that \({{\mathcal{X}}}_{\exp }\le {4}^{n}-1\) as \({\mathfrak{g}}\) is a subset of \({\mathfrak{su}}({2}^{n})\).

Efficiency-expressivity trade-off

Remarkably, the upper bound of gradient measurement efficiency depends on expressivity. Here, we present the main theorem on the relationship between gradient measurement efficiency and expressivity (the proof is provided in “Methods” and Supplementary Sections II–IV):

Theorem 1

(Informal) In deep QNNs, gradient measurement efficiency and expressivity obey the following inequalities:

and

The inequality (9) represents a trade-off relation between gradient measurement efficiency and expressivity as shown in Fig. 1a. This trade-off indicates that more expressive QNNs require higher measurement costs per parameter for gradient estimation. For example, when a QNN has maximum expressivity \({{\mathcal{X}}}_{\exp }={4}^{n}-1\) (e.g., a hardware-efficient ansatz with \({\mathcal{G}}={\{{X}_{j},{Y}_{j},{Z}_{j}{Z}_{j+1}\}}_{j = 1}^{n}\)), the gradient measurement efficiency must be \({{\mathcal{F}}}_{{\rm{eff}}}=1\), which implies that two or more gradient components cannot be measured simultaneously in this model.

The trade-off inequality (9) also suggests that we can increase gradient measurement efficiency by reducing the expressivity to fit a given problem, i.e., by encoding prior knowledge of the problem into the QNN as an inductive bias. In the context of QML, such a problem-tailored model is considered crucial to achieving quantum advantages44. For instance, an equivariant QNN, where the symmetry of a problem is encoded into the QNN structure, is one of the promising problem-tailored quantum models and exhibits high trainability and generalization by reducing the parameter space to search39,45,46,47,48,49,50,51,52,53,54,55. Later, we will introduce a general QNN ansatz called SLPA that leverages prior knowledge about symmetry to reach the upper bound of the trade-off inequality (9).

On the other hand, the inequality (10) shows that gradient measurement efficiency is bounded by expressivity. This bound is achieved, for example, in the commuting generator circuit23, where all generators, G1, ⋯ , GL, are mutually commuting. This circuit allows us to measure all gradient components simultaneously, implying \({{\mathcal{F}}}_{{\rm{eff}}}=L\). Also, since all generators are commutative, the expressivity is \({{\mathcal{X}}}_{\exp }=L\) by definition. Consequently, the commuting generator circuit achieves the bound of the inequality \({{\mathcal{X}}}_{\exp }\ge {{\mathcal{F}}}_{{\rm{eff}}}\). As a result of this inequality, a deeply overparameterized QNN with \(L\,\gg\, {{\mathcal{X}}}_{\exp }\) parameters requires \(L/{{\mathcal{F}}}_{{\rm{eff}}}\,\gg\, {{\mathcal{X}}}_{\exp }/{{\mathcal{F}}}_{{\rm{eff}}}\ge 1\) types of quantum measurements to estimate the gradient, leading to high measurement costs for training. Furthermore, combining inequalities (9) and (10), we have \({{\mathcal{F}}}_{{\rm{eff}}}\le {2}^{n-1/2}\), which is the upper bound of gradient measurement efficiency in QNNs.

We remark on the relationship between gradient measurement efficiency and trainability. In deep QNNs, it is known that the variance of the cost function in the parameter space decays inversely proportional to \(\,\text{dim}\,({\mathfrak{g}})\): \({\text{Var}}_{{\boldsymbol{\theta }}}[C({\boldsymbol{\theta }})] \sim 1/\,\text{dim}\,({\mathfrak{g}})=1/{{\mathcal{X}}}_{\exp }\)38,56,57. Thus, exponentially high expressivity results in an exponentially flat landscape of the cost function (so-called the barren plateaus58), which makes efficient training of QNNs impossible. In other words, expressivity has a trade-off with trainability. By contrast, high gradient measurement efficiency and high trainability are compatible. From the trade-off inequality (9) and \({\text{Var}}_{{\boldsymbol{\theta }}}[C({\boldsymbol{\theta }})] \sim 1/{{\mathcal{X}}}_{\exp }\), we have \({{\mathcal{F}}}_{{\rm{eff}}}\,\lesssim\, {4}^{n}{\text{Var}}_{{\boldsymbol{\theta }}}[C({\boldsymbol{\theta }})]\). This inequality means that we can increase \({{\mathcal{F}}}_{{\rm{eff}}}\) and Varθ[C(θ)] simultaneously, indicating the compatibility of high gradient measurement efficiency and high trainability.

Stabilizer-logical product ansatz

While Theorem 1 reveals the general trade-off relation between gradient measurement efficiency and expressivity, designing optimal quantum models that reach the upper bound of the trade-off inequality is a separate issue for realizing practical QML. Here, we propose a general ansatz of CBC called SLPA, which is constructed from stabilizers and logical Pauli operators to reach the upper bound of the trade-off (see “Methods” for the details of CBC). This ansatz is also insightful in understanding the trade-off relation from a symmetry perspective.

The SLPA is inspired by the stabilizer code in quantum error correction25. The stabilizer code is characterized by a stabilizer group \({\mathcal{S}}=\{{S}_{1},{S}_{2},\cdots \,\}\subset {{\mathcal{P}}}_{n}\), which satisfies

where \({S}_{j}\in {\mathcal{S}}\) is a Pauli operator. Given that s is the number of independent stabilizers in \({\mathcal{S}}\), the order of \({\mathcal{S}}\) is given by \(| {\mathcal{S}}| ={2}^{s}\), where an arbitrary element of \({\mathcal{S}}\) is written as a product of the s independent stabilizers. For this stabilizer group, we consider logical Pauli operators \({\mathcal{L}}=\{{L}_{1},{L}_{2},\cdots \,\}\subset {{\mathcal{P}}}_{n}\), which commute with the stabilizers:

where \({L}_{a}\in {\mathcal{L}}\) is a Pauli operator. In quantum error correction, the stabilizer code encodes quantum information into n − s logical qubits in the code space (the Hilbert subspace in which the eigenvalues of the stabilizers are all +1), detecting errors that flip the eigenvalues of the stabilizers. The logical operators correspond to operations on the encoded logical qubits. This stabilizer code establishes the foundation of fault-tolerant quantum computation based on promising quantum error-correcting codes, including the surface code59,60 and more general quantum low-density parity-check codes61.

The SLPA leverages the algebraic structure of the stabilizer code to improve gradient measurement efficiency without focusing on fault tolerance. Suppose that we are given stabilizers \({\mathcal{S}}\) and logical Pauli operators \({\mathcal{L}}\). The SLPA comprises block unitaries containing multiple variational rotation gates, as shown in Fig. 1b. To construct the SLPA, we take the product of the stabilizer Sj and the logical Pauli operator La, defining the jth generator of the ath block as

Using these generators, we construct the SLPA

with block unitaries

where each block can contain at most \(| {\mathcal{S}}| ={2}^{s}\) variational rotation gates. The multi-Pauli rotation gates in the circuit can be implemented using, for example, a single-Pauli rotation and Clifford gates25.

This SLPA enables efficient gradient estimation due to the following commutation relations between the generators \({G}_{j}^{a}\). First, the generators within the same block are all commutative:

Second, the generators in any two distinct blocks are either all commutative or all anti-commutative:

These commutation relations satisfy the requirements of CBC, ensuring that all gradient components of each block can be measured using only two types of quantum circuits. Specifically, the gradient can be measured efficiently using the linear combination of unitaries with an ancilla qubit (Supplementary Section V A). Conversely, any CBC can be formulated using a stabilizer group and logical Pauli operators, implying that the SLPA is a general ansatz of CBC (Supplementary Section V B). This stabilizer formalism also allows us to understand a necessary condition for the backpropagation scaling of CBC in general (Supplementary Section V C).

It is noteworthy that the SLPA has symmetry \({\mathcal{S}}\):

which is derived from \([{G}_{j}^{a},{\mathcal{S}}]=[{S}_{j}{L}_{a},{\mathcal{S}}]=0\). As shown in the following numerical experiment section, leveraging this property allows us to solve problems with symmetry \({\mathcal{S}}\) efficiently and accurately. Furthermore, when the stabilizers \({\mathcal{S}}\) commute with the observable O, we can measure all gradient components within a block simultaneously (i.e., only one type of quantum circuit is sufficient to measure all gradient components of each block) because the generators of the block are either all commutative or all anti-commutative with O: \([{G}_{j}^{a},O]=0\,\forall j\) or \(\{{G}_{j}^{a},O\}=0\,\forall j\) (see also “Methods”).

Let us revisit the efficiency-expressivity trade-off from the perspective of SLPA. We first consider the gradient measurement efficiency of SLPA. When the stabilizers \({\mathcal{S}}\) commute with the observable O, all gradient components of each block can be measured simultaneously, as discussed above. Therefore, given that each block can contain at most \(| {\mathcal{S}}| ={2}^{s}\) rotation gates, the gradient measurement efficiency, which is the mean number of simultaneously measurable gradient components, obeys

The equality holds if all blocks of the SLPA have 2s rotation gates.

The stabilizers limit expressivity instead of providing high gradient measurement efficiency. Since all the generators of the SLPA commute with the stabilizers (i.e., \([{\mathcal{G}},{\mathcal{S}}]=0\)), the DLA generated by them also commute with the stabilizers (i.e., \([{\mathfrak{g}},{\mathcal{S}}]=0\)). Then, the dimension of the subspace in \({\mathfrak{su}}({2}^{n})\) stabilized by \({\mathcal{S}}\) (the centralizer of \({\mathcal{S}}\)) is \({4}^{n}/| {\mathcal{S}}| ={4}^{n}/{2}^{s}\). Furthermore, given that \([{\mathfrak{g}},{\mathcal{S}}]=[O,{\mathcal{S}}]=0\), we can assume that the stabilizers \({\mathcal{S}}\) are not included in the generators \({\mathcal{G}}\) and thus the DLA \({\mathfrak{g}}\) because rotation gates generated by stabilizers, \({e}^{i\theta {S}_{j}}\), never affect the result of the cost function. This consideration provides the upper bound of the DLA dimension, namely the expressivity:

where the equality holds if the DLA covers the entire subspace stabilized by \({\mathcal{S}}\) except for \({\mathcal{S}}\) (i.e., the ansatz is universal under the symmetry constraint). Specifically, given k = n − s logical qubits for the stabilizer group \({\mathcal{S}}\), if \({\mathcal{L}}\) contains all 4k − 1 logical Pauli operators except for the identity, the generators \({\mathcal{G}}={\{{S}_{j}{L}_{a}\}}_{j,a}\) are sufficient to reach the upper bound of the above inequality as \({{\mathcal{X}}}_{\exp }=({4}^{k}-1){2}^{s}={4}^{n}/{2}^{s}-{2}^{s}\). For example, in the toric code on the torus with k = 259, two logical X and Z operators, which correspond to the two types of X and Z chains that wrap around the torus in the two directions, and their products (logical Pauli strings) are sufficient for universal ansatz. We note that 4k − 1 logical Pauli operators can be systematically obtained for any stabilizer group by considering the standard form of the check matrix26.

Combining Eqs. (17) and (18), we obtain the trade-off inequality (9) for the SLPA, \({{\mathcal{X}}}_{\exp }\le {4}^{n}/{{\mathcal{F}}}_{{\rm{eff}}}-{{\mathcal{F}}}_{{\rm{eff}}}\). Then, the upper bound of the inequality is attained if the numbers of rotation gates in all blocks are \(| {\mathcal{S}}| ={2}^{s}\) and the DLA covers the entire subspace under the symmetry constraint \({\mathcal{S}}\), indicating that the SLPA can be optimal for gradient estimation. This result also describes the trade-off relation between gradient measurement efficiency and expressivity from the perspective of symmetry; we can measure several gradient components simultaneously by exploiting the symmetric structure of the quantum circuit, but this instead constrains expressivity.

Numerical demonstration: learning a symmetric function

Due to its symmetric structure, the SLPA is particularly effective in problems involving symmetry. Such problems are common in quantum chemistry, physics, and machine learning, which are the main targets of quantum computing. As a demonstration, we consider the task of learning an unknown symmetric function f : ρ ↦ y, where ρ is an input quantum state, y is a real scalar, and f(ρ) is assumed to be linear with respect to ρ. Here, suppose we know in advance that \(f(\rho )=f({S}_{j}\rho {S}_{j}^{\dagger })\) holds for \(\forall {S}_{j}\in {\mathcal{S}}\), where \({\mathcal{S}}\) is a stabilizer group. This type of learning task is standard in the context of geometric deep learning45 and has broad applications, including molecular dynamics62, electronic structure calculations63, and computer vision64. To learn the unknown function, we use a quantum model hθ(ρ) = Tr[U(θ)ρU†(θ)O] to approximate f(ρ). For the symmetric function, an equivariant QNN is effective in achieving high accuracy, trainability, and generalization39,45,46,47,48,49,50,51,52,53,54,55. The equivariant QNN consists of an \({\mathcal{S}}\)-symmetric circuit U(θ) and an \({\mathcal{S}}\)-symmetric observable O (i.e., \([U({\boldsymbol{\theta }}),{\mathcal{S}}]=[O,{\mathcal{S}}]=0\)), satisfying the same invariance as the target function \({h}_{{\boldsymbol{\theta }}}(\rho )={h}_{{\boldsymbol{\theta }}}({S}_{j}\rho {S}_{j}^{\dagger })\). The SLPA can be viewed as an equivariant QNN due to its symmetry, allowing us to improve accuracy, trainability, and generalization as well as gradient measurement efficiency.

For concreteness, we consider a stabilizer group

with even n, where the number of independent operators in \({\mathcal{S}}\) is s = 2. Suppose that the target symmetric function is given by \(f(\rho )=\,{\text{Tr}}\,[{U}_{{\rm{tag}}}\rho {U}_{{\text{tag}}\,}^{\dagger }O]\) with an \({\mathcal{S}}\)-symmetric random unitary Utag and the \({\mathcal{S}}\)-symmetric observable O (i.e., \([{U}_{{\rm{tag}}},{\mathcal{S}}]=[O,{\mathcal{S}}]=0\)). Here, we set O = X1X2. To learn this function, we use Nt training data \({\{\left\vert {x}_{i}\right\rangle ,{y}_{i}\}}_{i = 1}^{{N}_{t}}\), where \(\vert {x}_{i}\rangle { = \bigotimes }_{j = 1}^{n}\vert {s}_{i}^{j}\rangle\) and \({y}_{i}=f(\vert {x}_{i}\rangle )\) are the product state of single qubit Haar-random states and its label, respectively. The model is optimized by minimizing the mean squared error loss function. We also prepare Nt test data for validation, which are sampled independently of training data. Below, we set Nt = 50.

We employ three types of variational quantum circuits, SLPA and local symmetric and non-symmetric ansatzes, to learn the function f(ρ) via hθ(ρ) = Tr[U(θ)ρU†(θ)O] (see Fig. 2 and “Methods” for detailed descriptions). First, the generators of the local symmetric ansatz (SA) are given by \({{\mathcal{G}}}_{{\rm{SA}}}={\{{X}_{j}{X}_{j+1},{Y}_{j}{Y}_{j+1},{Z}_{j}{Z}_{j+1}\}}_{j = 1}^{n}\), which commutes with the stabilizers \({\mathcal{S}}\). The DLA generated by \({{\mathcal{G}}}_{{\rm{SA}}}\) covers the entire subspace stabilized by \({\mathcal{S}}\), except for \({\mathcal{S}}\), indicating that \({{\mathcal{X}}}_{\exp }={4}^{n}/4-4\) (Supplementary Section VI). Then, although the upper bound of the gradient measurement efficiency is \({{\mathcal{F}}}_{{\rm{eff}}}=4\) by Theorem 1, this symmetric ansatz cannot reach it but instead exhibits \({{\mathcal{F}}}_{{\rm{eff}}}=1\), as shown later. We can construct the SLPA from this symmetric ansatz via Eqs. (13)–(15) by regarding the generator of the symmetric ansatz as the logical Pauli operator La. In other words, we construct a block of the SLPA from each rotation gate of the symmetric ansatz by taking the product of the generator La and the stabilizers \({\mathcal{S}}\), where the generators are given by \({{\mathcal{G}}}_{{\rm{SLPA}}}={{\mathcal{G}}}_{{\rm{SA}}}\times {\mathcal{S}}\). The DLA dimension of SLPA is the same as the symmetric ansatz, \({{\mathcal{X}}}_{\exp }={4}^{n}/4-4\). Meanwhile, given that the generators of each block are either all commutative or all anti-commutative with the observable O (which is derived by \([O,{\mathcal{S}}]=0\)), we can measure all four gradient components of each block simultaneously. Therefore, in contrast to the symmetric ansatz, this SLPA can reach the upper bound of the gradient measurement efficiency \({{\mathcal{F}}}_{{\rm{eff}}}=4\). For comparison, we also consider the local non-symmetric ansatz (NSA), where the generators \({{\mathcal{G}}}_{{\rm{NSA}}}={\{{X}_{j},{Y}_{j},{Z}_{j}{Z}_{j+1}\}}_{j = 1}^{n}\) do not commute with the stabilizers \({\mathcal{S}}\) and lead to the maximum expressivity in the full Hilbert space \({{\mathcal{X}}}_{\exp }={4}^{n}-1\)38. Hence, the gradient measurement efficiency of this model must be \({{\mathcal{F}}}_{{\rm{eff}}}=1\) by Theorem 1. In gradient estimation, we use the parameter-shift method for the symmetric and non-symmetric ansatzes and the linear combination of unitaries for the SLPA, where 1000 measurement shots are used per circuit. The numerical experiments in this work use Qulacs, an open-source quantum circuit simulator65.

First of all, we investigate the gradient measurement efficiency of these three models. In Fig. 3a–c, we numerically compute the commutation relations between all pairs of the gradient operators for random θ, where the black and yellow regions indicate [Γj(θ), Γk(θ)] = 0 and [Γj(θ), Γk(θ)] ≠ 0, respectively. While most pairs of gradient operators are not commutative in the symmetric and non-symmetric ansatzes, we observe a 4 × 4 block structure in the SLPA. This means that the SLPA allows us to measure four gradient components simultaneously, implying the high efficiency of the SLPA. Figure 3d shows the gradient measurement efficiency \({{\mathcal{F}}}_{{\rm{eff}}}^{(L)}\) for finite-depth circuits with varying the number of parameters L. In the symmetric and non-symmetric ansatzes, the efficiency decreases as the circuit becomes deeper and converges to \({{\mathcal{F}}}_{{\rm{eff}}}=1\) after overparameterized. The SLPA shows a similar behavior, but the efficiency is larger than those of the other two models for the entire region of L, eventually approaching the theoretical upper bound of \({{\mathcal{F}}}_{{\rm{eff}}}=4\) in the deep circuit limit. These results demonstrate the validity of our trade-off relation and the high gradient measurement efficiency of the SLPA in both shallow and deep circuits. In Supplementary Section VII A, we also investigate another type of quantum circuit, which has low expressivity despite the absence of stabilizer-type symmetry, supporting the validity of the trade-off.

a–c Commutators between two gradient operators Γj(θ) and Γk(θ) in the SLPA and symmetric and non-symmetric ansatzes for n = 4 qubits and L = 48 parameters. The black and yellow regions represent [Γj(θ), Γk(θ)] = 0 and [Γj(θ), Γk(θ)] ≠ 0 for random θ, respectively. d Changes in gradient measurement efficiency when the number of parameters L is varied for n = 4. Their values are computed by minimizing the number of simultaneously measurable sets of Γj(θ)'s for random θ. The blue circles, orange squares, and green triangles are the results of SLPA and symmetric and non-symmetric ansatzes, approaching four and one in the limit of L → ∞, respectively. The dashed gray lines represent the DLA dimension of each model, \(\,\text{dim}\,({\mathfrak{g}})\).

The high gradient measurement efficiency of SLPA can reduce the number of data samples needed for training. In Fig. 4, the SLPA shows significantly faster convergence of loss functions than the other models in terms of the cumulative number of measurement shots, i.e., training samples. This fast convergence stems from the high gradient measurement efficiency. As discussed above, the SLPA has \({{\mathcal{F}}}_{{\rm{eff}}}=4\) in the deep circuit limit, which is four times greater than the other two models with \({{\mathcal{F}}}_{{\rm{eff}}}=1\). Furthermore, the parameter-shift method used in the symmetric and non-symmetric ansatzes requires twice the number of circuits for estimating a gradient component than the linear combination of unitaries used in the SLPA. Thus, the number of measurement shots per epoch for the SLPA is one-eighth that of the other models in total, leading to a drastic reduction in the sample complexity for training.

The horizontal axis is the cumulative number of measurement shots. The blue, orange, and green solid (dashed) lines represent the test (training) losses for the SLPA, symmetric ansatz (SA), and non-symmetric ansatz (NSA), respectively. The shaded areas are the maximum and minimum of the test losses for 20 sets of random initial parameters. The numbers of qubits and parameters are n = 4 and L = 96.

Besides high training efficiency, the SLPA can learn the target function with high accuracy (i.e., low test loss). As shown in Fig. 4, the test loss of SLPA after training is comparable to that of the symmetric ansatz, implying high generalization performance of SLPA for this problem. This is due to encoding the symmetry of the target function into the SLPA as prior knowledge, similar to the symmetric ansatz. In the overparameterized SLPA and symmetric ansatz, the same DLA results in similar generalization performance. In contrast, the non-symmetric ansatz sufficiently reduces the training loss but does not reduce the test loss, indicating its low generalization performance. These results show the importance of symmetry encoding in this problem.

We highlight the trainability of SLPA. A potential concern is that the multi-Pauli rotations within the SLPA, which can be global, could lead to a barren plateau58 even in shallow circuits. However, this concern can be ignored; the global operators do not directly induce a barren plateau in the SLPA. Rather, our model is less prone to the barren plateau phenomenon than the symmetric ansatz when the circuit depth is \(L/n \sim {\mathcal{O}}(\log (n))\), where the SLPA exhibits a larger variance in the cost function compared to the symmetric ansatz. We discuss the high trainability of SLPA in more detail in Supplementary Section VII B.

Finally, while this section has investigated the symmetric function learning task, the SLPA can be applied to other types of problems associated with symmetry. In Supplementary Section VII C, we tackle a quantum phase recognition task as an example of learning problems without an explicit symmetric target function, demonstrating the high training efficiency and accuracy of SLPA. In this task, the data distribution (not the target function) is invariant under the action of symmetry. This demonstration suggests the broad applicability of SLPA beyond the symmetric function learning.

Beyond stabilizer-logical product ansatz

Here, we discuss some further potentials of the SLPA beyond the results presented in this work.

One intriguing potential is to extend the SLPA to encompass more general symmetries beyond the stabilizer group. These general symmetries, which include both Abelian and non-Abelian groups, can lead to more complex and exotic structures within the Hilbert space, introducing a challenge for extending our theory to accommodate such broader situations. To this end, there are several possible scenarios in which the SLPA can exploit other types of symmetries. First, when a group characterizing symmetry contains a stabilizer group as its subgroup, we can exploit the stabilizer group to construct an SLPA. While this SLPA cannot fully incorporate symmetry into the circuit, it allows for efficient gradient estimation without imposing unnecessary symmetry constraints. Second, eliminating assumptions from our theory could break through the limitations of SLPA. For instance, we could broaden the types of symmetries applicable in the SLPA by utilizing general generators Gj and general observable O (though this work is limited to Pauli operators) or by performing classical post-processing of the outputs from multiple SLPAs24,66. Understanding the efficiency-expressivity trade-off in such situations and elucidating the fundamental limit of efficient gradient estimation for QNNs with general symmetries remains an important open problem in realizing efficient QML.

Another potential is applying the SLPA to problems that lack symmetry. Regardless of the high gradient measurement efficiency of SLPA, the symmetry constraint may result in low accuracy in some problems without symmetry. To address this challenge, we can eliminate the symmetry constraint and reinforce the capability of SLPA by combining it with another parameterized quantum circuit. For instance, we consider U(θ) = USLPA(θ2)USB(θ1), where USLPA and USB are an SLPA and a non-symmetric parameterized circuit breaking the symmetry of the SLPA, respectively. In this circuit, the gradient of θ2 can be measured efficiently due to the commutation relations of the SLPA, whereas the gradient of θ1 must be measured with the parameter-shift method in general. If USB is sufficiently shallow compared to USLPA, the gradient measurement efficiency of U is still high, although additional cost is required for the parameter-shift method for the gradient of θ1. Meanwhile, USB can break the symmetry constraint of the SLPA, reinforcing the capability of the circuit. Therefore, combining the SLPA with another symmetry-breaking circuit can eliminate the symmetry constraint while maintaining high gradient measurement efficiency. We will leave further investigation of the capabilities of this model for future work.

Discussion

This work has proven the general trade-off relation between gradient measurement efficiency and expressivity in deep QNNs. Furthermore, based on this trade-off relation, we have proposed a general ansatz of CBC called the SLPA, which can reach the upper bound of the trade-off inequality by leveraging the symmetric structure of the quantum circuit. These results provide a guiding principle for designing efficient QNNs, fully unleashing the potential of QNNs.

While the SLPA allows for the most efficient gradient estimation, the theoretical limit of gradient measurement efficiency motivates further investigation of other approaches for training quantum circuits. A promising one is the use of gradient-free optimization algorithms, such as Powell’s method67 and simultaneous perturbation stochastic approximation68. Such algorithms use only a few quantum measurements to update the circuit parameters, potentially speeding up the training process. However, it remains unclear how effective the gradient-free algorithms are for large-scale problems. Thorough verification and refinement of these algorithms could overcome the challenge of high computational costs in VQAs. Another promising direction is the coherent manipulation of multiple copies of input data. Since our theory implicitly assumes that only one copy of input data is available at a time, the existence of more efficient algorithms surpassing our trade-off inequality is not prohibited in multi-copy settings. In fact, there is an efficient algorithm for measuring the gradient in multi-copy settings, where \({\mathcal{O}}(\,\text{polylog}\,(L))\) copies of input data are coherently manipulated to be measured by shadow tomography21,69. However, this algorithm is hard to implement in near-term quantum devices due to the requirements of many qubits and long execution times. Exploring more efficient algorithms in multi-copy settings is an important open issue.

Methods

Proof sketch of Theorem 1

To prove Theorem 1, we introduce a graph representation of DLA called DLA graph to clarify the relationship between gradient measurement efficiency and expressivity. The DLA graph consists of nodes and edges. Each node P corresponds to the Pauli basis of the DLA \({{\mathcal{G}}}_{{\rm{Lie}}}\) (i.e., \(P\in {{\mathcal{G}}}_{{\rm{Lie}}}\)), and two nodes \(P\in {{\mathcal{G}}}_{{\rm{Lie}}}\) and \(Q\in {{\mathcal{G}}}_{{\rm{Lie}}}\) are connected by an edge if they anti-commute, {P, Q} = 0. Remarkably, the commutation relations between the Pauli bases of the DLA are closely related to the simultaneous measurability of gradient components. Therefore, the DLA graph visualizes the commutation relations of the DLA, allowing us to clearly understand the relationship between the gradient measurement efficiency and the DLA structure.

The proof of Theorem 1 requires understanding the gradient measurement efficiency \({{\mathcal{F}}}_{{\rm{eff}}}\) and the expressivity \({{\mathcal{X}}}_{\exp }\) in terms of the DLA graph. By definition, the expressivity \({{\mathcal{X}}}_{\exp }\) corresponds to the total number of nodes in the DLA graph. On the other hand, the relationship between the gradient measurement efficiency \({{\mathcal{F}}}_{{\rm{eff}}}\) and the DLA graph is nontrivial. The first step to obtaining the gradient measurement efficiency is to consider whether given two gradient operators Γj and Γk are simultaneously measurable (i.e., whether [Γj, Γk] = 0). The gradient operator Γj is defined from the generator of the quantum circuit \({G}_{j}\in {\mathcal{G}}\) [see Eq. (4)], corresponding to a node of the DLA graph. In Supplementary Section III, we will present Lemmas 1–5 to show that the simultaneous measurability of Γj and Γk is determined by some structural relations between the nodes Gj, Gk, and the observable O in the DLA graph. Hence, how many gradient components can be simultaneously measured, namely \({{\mathcal{F}}}_{{\rm{eff}}}\), is also determined by the structure of the DLA graph.

Based on Lemmas 1–5, we decompose the DLA graph into several subgraphs, where nodes belonging to different subgraphs cannot be measured simultaneously. Therefore, the number of nodes in each subgraph bounds the number of simultaneously measurable gradient components, i.e., the gradient measurement efficiency. Using this idea, we can map the problem on \({{\mathcal{F}}}_{{\rm{eff}}}\) and \({{\mathcal{X}}}_{\exp }\) to the problem on the DLA graph, or specifically on the relation between the total number of nodes and the size of the subgraphs in the DLA graph. Finally, by considering constraints on the number of nodes derived from the decomposition to the subgraphs, we prove the inequalities between \({{\mathcal{F}}}_{{\rm{eff}}}\) and \({{\mathcal{X}}}_{\exp }\). The detailed proof is provided in Supplementary Sections II–IV.

Commuting block circuit

The CBC is a parameterized quantum circuit allowing for efficient gradient estimation23. It consists of B block unitaries:

where each block contains multiple variational rotation gates as

Here, \({G}_{j}^{a}\in {{\mathcal{P}}}_{n}\) is the generator of the jth rotation gate in the ath block, and \({{\boldsymbol{\theta }}}_{a}=({\theta }_{1}^{a},{\theta }_{2}^{a},\cdots \,)\) is the variational rotation angles. The generators of CBC must satisfy the following two conditions. First, generators within the same block are commutative:

Second, generators in any two distinct blocks are either all commutative or all anti-commutative:

We also consider a cost function C = tr[UρU†O] with a Pauli observable O.

This specific structure of CBC allows us to measure the gradient components of the cost function with only two different quantum circuits for each block. To measure the gradient components for the ath block, we divide the generators of the rotation gates \({{\mathcal{G}}}_{a}={\{{G}_{j}^{a}\}}_{j}\) into the commuting and anti-commuting parts with the observable O: \({{\mathcal{G}}}_{a}={{\mathcal{G}}}_{a}^{{\rm{com}}}\sqcup {{\mathcal{G}}}_{a}^{{\rm{ant}}}\), where \([{{\mathcal{G}}}_{a}^{{\rm{com}}},O]=\{{{\mathcal{G}}}_{a}^{{\rm{ant}}},O\}=0\). Then, the gradient components in \({{\mathcal{G}}}_{a}^{{\rm{com}}}\) (\({{\mathcal{G}}}_{a}^{{\rm{ant}}}\)) can be measured simultaneously using the linear combination of unitaries with an ancilla qubit (see Supplementary Section V A for details). Therefore, the full gradient of U(θ) can be estimated with only 2B types of quantum measurements, which is independent of the number of rotation gates in each block (to be precise, 2B − 1 quantum measurements are sufficient because the commuting part of the final block does not contribute to the gradient). This allows us to measure the gradient more efficiently than conventional variational models based on the parameter-shift method, where the measurement cost is proportional to the number of parameters.

While the basic framework for CBC has been proposed, there are still some challenges to be addressed. First, it remains unclear how the specific structure of the commuting block circuit affects the QNN expressivity. Second, a general method to construct the CBC or find the generators \({G}_{j}^{a}\) that satisfy the commutation relations of Eqs. (22) and (23) has not yet been established. The SLPA addresses these challenges by providing a general construction method with stabilizers and logical Pauli operators and uncovering its expressivity based on the stabilizer formalism.

Quantum circuits used in numerical experiments

The unitary of the local symmetric ansatz is given by

Here, a local Pauli operator Lk is defined as

with

where a ∈ {0, 1, 2}, b ∈ {1, ⋯ , n/2}, μk = a + b, νk = a + b + n/2, \(\ell \in {\mathbb{Z}}\), and \({P}_{j}^{\mu }={P}_{j+n}^{\mu }\). The SLPA is constructed by taking the products of the stabilizers \({\mathcal{S}}\) and the generators of USA(θ) as

where \({U}_{k}({{\boldsymbol{\theta }}}_{k}^{d})\) is the block unitary defined as

Finally, the unitary of the non-symmetric ansatz is given by

with

We optimize these quantum circuits by minimizing the mean squared error loss function with the Adam optimizer70. The hyper-parameter values used in this work are initial learning rate = 10−3, β1 = 0.9, β2 = 0.999, and ϵ = 10−8. We also adopt the stochastic gradient descent71, where only one training data is used to estimate the gradient at each iteration.

Data availability

The data used in numerical experiments are available from the authors upon request.

Code availability

Further implementation details are available from the authors upon request.

References

Hinton, G. E., Osindero, S. & Teh, Y. W. A fast learning algorithm for deep belief nets. Neural Comput. 18, 1527 (2006).

Krizhevsky, A., Sutskever, I. & Hinton, G. E. ImageNet classification with deep convolutional neural networks. Commun. ACM 60, 84 (2012).

Vaswani, A. et al. Attention is all you need. in: Proceedings of the 31st International Conference on Neural Information Processing Systems, NIPS’17 (Curran Associates Inc., Red Hook, NY, USA, 2017) pp 6000–6010.

Jumper, J. M. et al. Highly accurate protein structure prediction with alphafold. Nature 596, 583 (2021).

Carleo, G. & Troyer, M. Solving the quantum many-body problem with artificial neural networks. Science 355, 602 (2017).

Rumelhart, D. E., Hinton, G. E. & Williams, R. J. Learning representations by back-propagating errors. Nature 323, 533 (1986).

Baydin, A. G., Pearlmutter, B. A., Radul, A. A. & Siskind, J. M. Automatic differentiation in machine learning: a survey. J. Mach. Learn. Res. 18, 1 (2018).

Peruzzo, A. et al. A variational eigenvalue solver on a photonic quantum processor. Nat. Commun. 5, 4213 (2014).

Farhi, E., Goldstone, J. & Gutmann, S. A quantum approximate optimization algorithm. Preprint at arXiv https://doi.org/10.48550/arXiv.1411.4028 (2014).

Farhi, E. & Neven, H. Classification with quantum neural networks on near term processors. Preprint at arXiv https://doi.org/10.48550/arXiv.1802.06002 (2018).

Liu, J.-G. & Wang, L. Differentiable learning of quantum circuit Born machines. Phys. Rev. A 98, 062324 (2018).

Mitarai, K., Negoro, M., Kitagawa, M. & Fujii, K. Quantum circuit learning. Phys. Rev. A 98, 032309 (2018).

Benedetti, M., Lloyd, E., Sack, S. & Fiorentini, M. Parameterized quantum circuits as machine learning models. Quantum Sci. Technol. 4, 043001 (2019).

Schuld, M., Bocharov, A., Svore, K. M. & Wiebe, N. Circuit-centric quantum classifiers. Phys. Rev. A 101, 032308 (2020).

Wiebe, N., Kapoor, A. & Svore, K. M. Quantum deep learning. Preprint at arXiv https://doi.org/10.48550/arXiv.1412.3489 (2014).

Schuld, M., Sinayskiy, I. & Petruccione, F. An introduction to quantum machine learning. Contemp. Phys. 56, 172 (2015).

Biamonte, J. et al. Quantum machine learning. Nature 549, 195 (2017).

Dunjko, V. & Briegel, H. J. Machine learning & artificial intelligence in the quantum domain: a review of recent progress. Rep. Prog. Phys. 81, 074001 (2018).

Cerezo, M. et al. Variational quantum algorithms. Nat. Rev. Phys. 3, 625 (2021).

Gilyén, A., Arunachalam, S. & Wiebe, N. Optimizing quantum optimization algorithms via faster quantum gradient computation. in: Proceedings of the Thirtieth Annual ACM-SIAM Symposium on Discrete Algorithms, Proceedings (Society for Industrial and Applied Mathematics, Philadelphia, PA, 2019) pp 1425–1444.

Abbas, A. et al. On quantum backpropagation, information reuse, and cheating measurement collapse. Advances inNeural Information Processing Systems 36 (2023).

Schuld, M., Bergholm, V., Gogolin, C., Izaac, J. & Killoran, N. Evaluating analytic gradients on quantum hardware. Phys. Rev. A 99, 032331 (2019).

Bowles, J., Wierichs, D. & Park, C.-Y. Backpropagation scaling in parameterised quantum circuits. Preprint at arXiv https://doi.org/10.48550/arXiv.2306.14962 (2023).

Coyle, B. et al. Training-efficient density quantum machine learning. Preprint at arXiv https://doi.org/10.48550/arXiv.2405.20237 (2024).

Gottesman, D. Stabilizer codes and quantum error correction. PhD Thesis, California Institute of Technology (1997).

Nielsen, M. A. & Chuang, I. L. Quantum Computation and Quantum Infomation (Cambridge University Press, 2010).

DiVincenzo, D. P. Two-bit gates are universal for quantum computation. Phys. Rev. A 51, 1015 (1995).

Lloyd, S. Almost any quantum logic gate is universal. Phys. Rev. Lett. 75, 346 (1995).

Barenco, A. et al. Elementary gates for quantum computation. Phys. Rev. A 52, 3457 (1995).

Lloyd, S. Quantum approximate optimization is computationally universal. Preprint at arXiv https://doi.org/10.48550/arXiv.1812.11075 (2018).

Marvian, I. Restrictions on realizable unitary operations imposed by symmetry and locality. Nat. Phys. 18, 283 (2022).

Morales, M. E. S., Biamonte, J. D. & Zimborás, Z. On the universality of the quantum approximate optimization algorithm. Quantum Inf. Process. 19, 1 (2020).

Gross, D., Audenaert, K. & Eisert, J. Evenly distributed unitaries: on the structure of unitary designs. J. Math. Phys. 48, 052104 (2007).

Dankert, C. Efficient simulation of random quantum states and operators. Preprint at arXiv https://doi.org/10.48550/arXiv.quant-ph/0512217 (2005).

Dankert, C., Cleve, R., Emerson, J. & Livine, E. Exact and approximate unitary 2-designs and their application to fidelity estimation. Phys. Rev. A 80, 012304 (2009).

Ji, Z., Liu, Y.-K. & Song, F. Pseudorandom quantum states. in: Lecture Notes in Computer Science (Springer International Publishing, Cham, 2018) pp 126–152.

Sim, S., Johnson, P. D. & Aspuru-Guzik, A. Expressibility and entangling capability of parameterized quantum circuits for hybrid quantum-classical algorithms. Adv. Quantum Technol. 2, 1900070 (2019).

Larocca, M. et al. Diagnosing barren plateaus with tools from quantum optimal control. Quantum 6, 824 (2022).

Zheng, H., Li, Z., Liu, J., Strelchuk, S. & Kondor, R. Speeding up learning quantum states through group equivariant convolutional quantum ansätze. PRX Quantum 4, 020327 (2023).

Albertini, F. & D’Alessandro, D. Notions of controllability for quantum mechanical systems. in: Proceedings of the 40th IEEE Conference on Decision and Control (Cat. No.01CH37228), Vol. 2 (2001) pp 1589–1594.

Zeier, R. & Schulte-Herbrüggen, T. Symmetry principles in quantum systems theory. J. Math. Phys. 52, 113510 (2011).

D’Alessandro, D. Introduction to quantum control and dynamics. Chapman & Hall/CRC Applied Mathematics & Nonlinear Science (Taylor & Francis, 2007).

Larocca, M., Ju, N., García-Martín, D., Coles, P. J. & Cerezo, M. Theory of overparametrization in quantum neural networks. Nat. Comput. Sci. 3, 542 (2023).

Kübler, J. M., Buchholz, S. & Schölkopf, B. The inductive bias of quantum kernels. Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems 34 (2021).

Bronstein, M. M., Bruna, J., Cohen, T. & Veličković, P. Geometric deep learning: grids, groups, graphs, geodesics, and gauges. Preprint at arXiv https://doi.org/10.48550/arXiv.2104.13478 (2021).

Verdon, G. et al. Quantum graph neural networks. Preprint at arXiv https://doi.org/10.48550/arXiv.1909.12264 (2019).

Larocca, M. et al. Group-invariant quantum machine learning. PRX Quantum 3, 030341 (2022).

Meyer, J. J. et al. Exploiting symmetry in variational quantum machine learning. PRX Quantum 4, 010328 (2023).

Skolik, A., Cattelan, M., Yarkoni, S., Bäck, T. & Dunjko, V. Equivariant quantum circuits for learning on weighted graphs. npj Quantum Inf. 9, 47 (2023).

Ragone, M. et al. Representation theory for geometric quantum machine learning. Preprint at arXiv https://doi.org/10.48550/arXiv.2210.07980 (2022).

Nguyen, Q. T. et al. Theory for equivariant quantum neural networks. PRX Quantum 5, 020328 (2024).

Schatzki, L., Larocca, M., Nguyen, Q. T., Sauvage, F. & Cerezo, M. Theoretical guarantees for permutation-equivariant quantum neural networks. npj Quantum Inf. 10, 12 (2024).

Sauvage, F., Larocca, M., Coles, P. J. & Cerezo, M. Building spatial symmetries into parameterized quantum circuits for faster training. Quantum Sci. Technol. 9, 015029 (2024).

Chinzei, K., Tran, Q. H., Maruyama, K., Oshima, H. & Sato, S. Splitting and parallelizing of quantum convolutional neural networks for learning translationally symmetric data. Phys. Rev. Res. 6, 023042 (2024).

Chinzei, K., Tran, Q. H., Endo, Y. & Oshima, H. Resource-efficient equivariant quantum convolutional neural networks. Preprint at arXiv https://doi.org/10.48550/arXiv.2410.01252 (2024).

Ragone, M. et al. A unified theory of barren plateaus for deep parametrized quantum circuits. Nat. Commun. 15, 7172 (2024).

Fontana, E. et al. The adjoint is all you need: Characterizing Barren Plateaus in quantum ansätze. Nat. Commun. 15, 7171 (2024).

McClean, J. R., Boixo, S., Smelyanskiy, V. N., Babbush, R. & Neven, H. Barren plateaus in quantum neural network training landscapes. Nat. Commun. 9, 4812 (2018)

Kitaev, A. Y. Fault-tolerant quantum computation by anyons. Ann. Phys. (N. Y.) 303, 2 (2003).

Horsman, D., Fowler, A. G., Devitt, S. & Van Meter, R. Surface code quantum computing by lattice surgery. N. J. Phys. 14, 123011 (2012).

Breuckmann, N. P. & Eberhardt, J. N. Quantum low-density parity-check codes. PRX Quantum 2, 040101 (2021).

Batzner, S. et al. E(3)-equivariant graph neural networks for data-efficient and accurate interatomic potentials. Nat. Commun. 13, 2453 (2022).

Gong, X. et al. General framework for E(3)-equivariant neural network representation of density functional theory Hamiltonian. Nat. Commun. 14, 2848 (2023).

Cohen, T. & Welling, M. Group equivariant convolutional networks. in: International Conference on Machine Learning (PMLR, 2016) pp 2990–2999.

Suzuki, Y. et al. Qulacs: a fast and versatile quantum circuit simulator for research purpose. Quantum 5, 559 (2021).

Huang, P.-W. & Rebentrost, P. Post-variational quantum neural networks. Preprint at arXiv https://doi.org/10.48550/arXiv.2307.10560 (2023).

Powell, M. J. D. An efficient method for finding the minimum of a function of several variables without calculating derivatives. Comput. J. 7, 155 (1964).

Spall, J. C. Multivariate stochastic approximation using a simultaneous perturbation gradient approximation. IEEE Trans. Autom. Control 37, 332 (1992).

Aaronson, S. Shadow tomography of quantum states. SIAM J. Comput. 49, STOC18 (2020).

Kingma, D. P. & Ba, J. Adam: A method for stochastic optimization. in: (eds Bengio, Y. and LeCun, Y.) 3rd International Conference on Learning Representations, ICLR 2015, San Diego, CA, USA, May 7–9, 2015, Conference Track Proceedings, (2015).

Robbins, H. & Monro, S. A stochastic approximation method. Ann. Math. Stat. 22, 400 (1951).

Acknowledgements

Fruitful discussions with Riki Toshio, Yuichi Kamata, Shintaro Sato, Snehal Raj, and Brian Coyle are gratefully acknowledged. S.Y. was supported by FoPM, WINGS Program, the University of Tokyo.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

K.C., S.Y., and Q.T. developed the theoretical aspects of this work. K.C. and S.Y. conducted the numerical experiments. K.C., S.Y., Q.T., Y.E., and H.O. contributed to technical discussions and writing of the paper. K.C. and S.Y. equally contributed to this entire work.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Chinzei, K., Yamano, S., Tran, Q.H. et al. Trade-off between gradient measurement efficiency and expressivity in deep quantum neural networks. npj Quantum Inf 11, 79 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41534-025-01036-7

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41534-025-01036-7