Abstract

Dissipative engineering is a powerful tool for quantum state preparation, and has drawn significant attention in quantum algorithms and quantum many-body physics in recent years. In this work, we introduce a novel approach using the Lindblad dynamics to efficiently prepare the ground state for general ab initio electronic structure problems on quantum computers, without variational parameters. These problems often involve Hamiltonians that lack geometric locality or sparsity structures, which we address by proposing two generic types of jump operators for the Lindblad dynamics. Type-I jump operators break the particle number symmetry and should be simulated in the Fock space. Type-II jump operators preserves the particle number symmetry and can be simulated more efficiently in the full configuration interaction space. For both types of jump operators, we prove that in a simplified Hartree-Fock framework, the spectral gap of our Lindbladian is lower bounded by a universal constant. For physical observables such as energy and reduced density matrices, the convergence rate of our Lindblad dynamics with Type-I jump operators remains universal, while the convergence rate with Type-II jump operators only depends on coarse grained information such as the number of orbitals and the number of electrons. To validate our approach, we employ a Monte Carlo trajectory-based algorithm for simulating the Lindblad dynamics for full ab initio Hamiltonians, demonstrating its effectiveness on molecular systems amenable to exact wavefunction treatment.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Quantum state preparation is a fundamental task in quantum simulation and quantum algorithm design1,2,3,4,5,6. While eigenstates of a Hamiltonian can, in principle, be prepared using quantum phase estimation (QPE) and its variants, these algorithms themselves often require an initial state that has a significant overlap with the target state7,8,9,10,11,12,13,14,15. Dissipative state engineering offers a very different perspective on this problem. Rather than treating dissipation as a source of decoherence due to system-environment coupling, properly designed dissipative dynamics, such as those governed by the Lindblad equation, can encode a wide variety of strongly correlated states as the steady states of a dynamical process. Dissipative techniques and state preparation techniques using mid-circuit measurements, in general, have been widely employed in preparing matrix product states, ground states of stabilizer codes, spin systems, and other states exhibiting long-range entanglement2,16,17,18,19,20,21,22. There has been also growing recent interest in using Lindblad dynamics as an algorithmic tool for thermal state and ground state preparation23,24,25,26,27,28,29,30,31. However, many applications have focused on Hamiltonians with special structures, as the dissipative terms often need to be carefully engineered based on the special properties of the Hamiltonian. In contrast, in quantum chemistry and materials science, ab initio Hamiltonians lack specific geometric locality or sparsity, which significantly complicates the design of dissipative terms.

In this work, we overcome this difficulty and present a novel method for using Lindblad dynamics to efficiently prepare the ground state for general ab initio electronic structure problems on quantum computers. Our approach builds upon recent developments in quantum ground state preparation25, which has the advantage of being applicable to both commuting and non-commuting Hamiltonians on an equal basis. Unlike ref. 25, which prepares the ground state using a single jump operator together with a coherent term, we propose two sets of Lindblad jump operators, termed Type-I and Type-II. Each set contains poly(L) jump operators (L is the number of spatial orbitals), which are agnostic to chemical details and thus can readily be applied to ab initio Hamiltonians with unstructured and long-range coefficients. The process does not involve variational parameters. Type-I Lindblad dynamics break the particle-number symmetry and must be simulated in the Fock space. In contrast, Type-II jump operators preserve the particle number, allowing for more efficient simulation (on both classical and quantum computers) in the full configuration interaction (FCI) space.

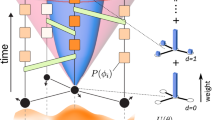

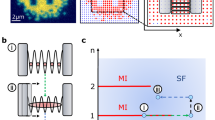

The efficiency of Lindblad dynamics for quantum state preparation is quantified by the mixing time, which is the time required to reach the target steady state to a certain precision from an arbitrary initial state32,33. Theoretical analysis of the mixing time is in general a challenging task, and is often feasible only for specific systems, parameter regimes, or simplified settings34,35,36,37,38,39. Our strategy is to first theoretically analyze the spectral gap of the Lindbladian, as well as dynamics of observables, such as the energy and the reduced density matrix (RDM), within a simplified Hartree-Fock (HF) framework. In this setting, the combined action of the jump operators effectively implements a classical Markov chain Monte Carlo within the molecular orbital basis. We prove that the convergence can be provably agnostic to specific chemical details, and in some cases, the convergence rate can be universal. We then perform numerical simulations to examine the transferability of this behavior to the full ab initio Hamiltonian, using an approach based on unraveled Lindblad dynamics. We also present an active-space-based strategy to reduce the number of jump operators in the implementation, thereby lowering the simulation cost while preserving the convergence behavior. This is applied to molecular systems, such as BeH2, H2O, and Cl2, which are amenable to exact wavefunction treatment within the FCI space. We also apply our method to investigate the stretched square H4 system, which has nearly degenerate low-energy states and poses challenges for highly accurate quantum chemistry methods, such as CCSD(T). In all cases, the Lindblad dynamics can prepare a quantum state with an energy that achieves chemical accuracy, even in the strongly correlated regime. A schematic workflow of our approach is shown in Fig. 1.

We consider the ab initio Hamiltonian in electronic structure theory for molecular systems. The central task in this framework is to construct Lindblad jump operators, derived from either Type-I or Type-II coupling operators. An active-space strategy is employed to reduce the simulation cost. The Lindblad dynamics can be efficiently simulated on quantum devices using only a single ancilla qubit, and the approach is classically validated using a wavefunction trajectory method.

Results

Dissipation engineering for ground state preparation

We consider Lindblad dynamics of the form:

For ground state preparation, the key object in Ref. 25 is the following jump operator:

Here, {Ak} are called (primitive) coupling operators, whose selection will be discussed in detail later. Each jump operator \({\hat{K}}_{k}\) is derived by reweighting Ak in the eigenbasis \({\{\left\vert {\psi }_{i}\right\rangle \}}_{i = 0}^{N-1}\) of the Hamiltonian \(\hat{H}\) by a filter function \(\hat{f}(\omega )\) evaluated at the energy difference λi − λj. The filter function \(\hat{f}(\omega )\) is only supported on the negative axis. In other words, \(\hat{f}({\lambda }_{i}-{\lambda }_{j})=0\) for any i≥j (assuming λ0 < λ1≤ ⋯ ≤λN−1). As a result, the jump operator \({\hat{K}}_{k}\) only allows transitions between the eigenvectors of \(\hat{H}\) that lower the energy. Since the Lindblad dynamics generate a completely positive, trace preserving (CPTP) map40,41,42, 〈ψi∣ρ(t)∣ψi〉 is a normalized probability distribution at time any t. In the energy basis, the dynamics continuously “shovels” high-energy states toward low-energy ones, eventually reaching the ground state, as shown in Fig. 2. Furthermore, we can easily verify \({\hat{K}}_{k}\left\vert {\psi }_{0}\right\rangle =0\) since \(\hat{f}({\lambda }_{j}-{\lambda }_{0})=0\) for any j ≥ 0. This immediately suggests that the ground state \(\vert {\psi }_{0} \rangle \langle {\psi }_{0} \vert\) is a stationary point of the Lindblad dynamics. This dynamics is ergodic if the ground state is the only stationary point, and this can be achieved by a carefully chosen set of coupling operators {Ak}.

At first glance, it may seem that constructing the jump operator in Eq. (2) requires diagonalizing \(\hat{H}\), which would clearly defeat the purpose. However, we can reformulate the definition of \({\hat{K}}_{k}\) in the time domain as

where \({A}_{k}(s)={e}^{{\rm{i}}\hat{H}s}{A}_{k}{e}^{-{\rm{i}}\hat{H}s}\) is the Heisenberg evolution of Ak, and \(f(s)=\frac{1}{2\pi }{\int}_{{\mathbb{R}}}\hat{f}(\omega ){e}^{-{\rm{i}}\omega s}\,{\rm{d}}\omega\) is the inverse Fourier transform of the filter function \(\hat{f}\) in the frequency domain.

In this form, the construction of the jump operator can be achieved using standard Trotter expansions for digitally simulating the Hamiltonian evolution. Additionally, the Trotter expansion can also be applied to simulate the Lindblad dynamics in Eq. (1). The choice of the filter function depends only on coarse-grained properties of the system, such as estimates of the spectral radius and the spectral gap \(\hat{H}\). A brief review of the selection of the filter function, the quantum simulation algorithm, as well as a rule of thumb for resource estimates is provided in the Methods section and Section I in the Supplementary Information (SI), respectively.

Types I and II jump operators for ab initio calculations

Unlike lattice problems, the second-quantized Hamiltonians in ab initio electronic structure calculations do not have clean forms, such as nearest-neighbor interactions. Therefore, it is important to choose a simple yet effective set of coupling operators {Ak} that are easy to implement and allow the system to converge rapidly towards the ground state. In this work, we introduce two simple sets of primitive coupling operators, referred to as Type-I and Type-II, respectively. The corresponding jump operators can be constructed according to Eq. (3).

We choose the set of Type-I coupling operators to be \({{\mathcal{A}}}_{{\rm{I}}}=\{{a}_{i}^{\dagger }| i=1,2,\cdots \,,2L\}\cup \{{a}_{i}| i=1,2,\cdots \,,2L\}\). This includes all of the 4L (counting spatial and spin degrees of freedom) fermionic creation and annihilation operators. Each operator can be expressed in the atomic orbital basis, molecular orbital basis, or some other basis set. These different choices differ by a unitary matrix. Given the linear relationship between the jump operator and the coupling operator, a unitary rotation of the coupling operators will correspondingly induce a unitary rotation of the jump operators. This unitary rotation can be viewed as a gauge degree of freedom. Ideally, the numerical result should be independent of this gauge. We will verify that this is indeed the case in a simplified HF setting.

The set of Type-II coupling operators is \({{\mathcal{A}}}_{{\rm{II}}}=\{{a}_{i}^{\dagger }{a}_{j}| i,j=1,2,\cdots \,,2L\}\) which includes every fermionic creation and annihilation pairs, and has 4L2 elements in total. Most Hamiltonians in ab initio electronic structure calculations are particle-number-preserving. Unlike Type-I coupling operators, which break particle number symmetries and must be simulated in the Fock space, Type-II coupling operators (and the corresponding jump operators) preserve particle number symmetries. The corresponding Lindblad dynamics can be simulated in the FCI space. Note that the dimension of the density matrix in the Fock formulation is 42L, and that of the FCI space is \({\left(\begin{array}{c}2L\\ {N}_{{\rm{e}}}\end{array}\right)}^{2}\), where Ne is the number of electrons. The difference becomes particularly significant when Ne is very small or large, such as simulating alkali metals and halogen elements in a small basis set. The particle number symmetry can be used also reduce the cost of quantum simulations, such as the Trotter error for Hamiltonian simulation \({e}^{-{\rm{i}}\hat{Ht}}\)43,44, or the block encoding subnormalization factors of the Hamiltonian45,46.

Both Type-I and Type-II sets are “bulk” coupling operators, meaning that dissipation is introduced on every (atomic or molecular) basis function. As will be seen below, this can be very effective in reducing the mixing time. On the other hand, this comes at the cost of introducing a large number of jump operators, which increases the simulation cost, both on quantum computers25 and in classical simulation. We will also discuss how to reduce the number using active space ideas.

Universal fast convergence with Type-I set in HF theory

We first consider the ground state preparation via Lindbladians at the HF level before moving on to the interacting regime. We refer readers to the Methods section for a brief review of the HF theory. Essentially, after self-consistency is reached, all the information of the HF theory is encoded in a non-interacting Hamiltonian

where the Hermitian matrix F is called the Fock matrix. Let Φ be the unitary matrix that diagonalizes F, then the new basis set, known as molecular orbitals, is obtained by transforming the atomic orbitals using Φ. For such Hamiltonians, the information contained in the many-body density operator ρ is entirely stored in the one-particle RDM (1-RDM), defined as

According to the Thouless theorem47,48,

Therefore, we have

and similarly

This implies that for the Type-I set, the jump operators are all linear in fermionic creation and annihilation operators. The corresponding Lindblad dynamics is quasi-free49,50,51,52, and we can derive a closed-form equation of motion for the 1-RDM

Here

and we use the fact that the Fock matrix F is Hermitian. A detailed derivation of Eq. (9) can be found in Section II in the SI. For any filter function \(\hat{f}\) satisfying \(\hat{f}(\omega )=1\) on \([-2\parallel \hat{H}{\parallel }_{2},-\Delta ]\) and \(\hat{f}(\omega )=0\) on [0, + ∞), we have

where 1 is the identity matrix. The equation of motion Eq. (9) then takes a very simple form

In particular, if we perform a unitary rotation of the fermionic creation and annihilation operators used to define the primitive coupling operators, this amounts to a gauge choice, and the final equation of motion Eq. (12) is gauge-invariant.

From Eq. (12) we can easily see that \({P}^{\star }=\hat{f}(F)\) is the unique stationary point. In fact, let P(t) and \({P}^{{\prime} }(t)\) be the solution to solve Eq. (12) with different initial values P(0) and \({P}^{{\prime} }(0)\), then

where \({\parallel A\parallel }_{{\rm{F}}}:=\sqrt{{\rm{Tr}}({A}^{\dagger }A)}\) denotes the Frobenius norm of matrices. The detailed derivation of Eq. (13) is provided in Section IV in the SI.

We may get more insight by rewriting Eq. (12) in the energy basis. Specifically, we define

where Φ is the coefficient matrix of the molecular orbitals. Then we have

Here we use FΛ = ΛΦ and Λ = diag(ε1, ⋯ , ε2L) with \({\varepsilon }_{1}\le \cdots \le {\varepsilon }_{{N}_{{\rm{e}}}}\le 0 < {\varepsilon }_{{N}_{{\rm{e}}}+1}\le \cdots \le {\varepsilon }_{2L}\). Therefore, the stationary point \({\widetilde{P}}{^{\star}}\) is given by

which is consistent with the aufbau principle, and this is achieved without explicitly diagonalizing the Fock matrix. In particular, the diagonal elements of \(\widetilde{P}(t)\) evolves as follows:

Assume the initial occupation numbers of the molecular orbitals (i.e., the diagonal elements of the initial 1-RDM \(\widetilde{P}(0)\)) is given by ni(0), then

Therefore, in the energy basis, the Lindblad dynamics with Type-I jump operators can drive the occupation numbers of the lowest Ne molecular orbitals to approach 1 exponentially, while the occupation numbers of the remaining 2L − Ne high-energy molecular orbitals exponentially approach zero (see Fig. 3). The convergence rate is universal and is independent of any chemical details or initial starting point. The numerical validation of this statement will be presented in the later sections.

Convergence with Type-II set oblivious to chemical details in HF theory

Let us now carry out the calculation for Type-II jump operators in the HF setting. Recall \(\hat{f}(\omega )=1\) on \([-2\parallel \hat{H}{\parallel }_{2},-\Delta ]\) and \(\hat{f}(\omega )=0\) on [0, + ∞), using the Thouless theorem, the jump operators satisfy

Note that \({\hat{K}}_{ij}\) is a quadratic operator in the fermionic operators and not Hermitian. This means that the Lindblad dynamics is not quasi-free, and the 1-RDM cannot satisfy a closed-form equation of motion52. Despite this, we demonstrate below an explicit description of the dynamics in the energy basis. For the coherent part,

Here \({{\mathcal{L}}}_{H}^{\dagger }\) denotes the adjoint of the superoperator \({{\mathcal{L}}}_{H}\) with respect to the Hilbert-Schmidt inner product. Moreover, using that Φ consists of orthonormal columns, we find

Similarly, for r ≠ s,

Here

For r = s,

In all the expressions above, the operators occurring in the Lindblad dynamics are all invariant to the gauge choice in the primitive coupling operators, and can all be expressed using simple operators in molecular orbitals. For a detailed derivation of the above equations, interested readers can refer to the Section III in the SI.

Consider the 1-RDM in the molecular orbital basis \(\widetilde{P}={\left({\rm{Tr}}({c}_{r}^{\dagger }{c}_{s}\rho )\right)}_{1\le s,r\le 2L}={\Phi }^{\dagger }P\Phi\). Then the equation of motion of the entries of \(\widetilde{P}\) depends on that of the 2-RDM. Specifically, for the off-diagonal elements,

For the diagonal elements,

Further derivations of the equation of motion for the 2-RDM will lead to the 3-RDM, and so forth. It resembles the renowned Bogoliubov–Born–Green–Kirkwood–Yvon (BBGKY) hierarchy53. To make the system solvable, we can truncate the equations by neglecting the higher-order moment terms. At this point, if we consider these matrix elements as random processes, then the equations of motion describe a classical continuous-time Markov chain, with the stationary distribution 1-RDM approximately given by \({\widetilde{P}}{^{\star}}={\rm{diag}}(\underbrace{1,\cdots ,1}_{{N}_{{\rm{e}}}},\underbrace{0,\cdots ,0}_{2L-{N}_{{\rm{e}}}})\) according to the aufbau principle. Nonetheless, from Eq. (25) and Eq. (26), it is evident that the evolution of the RDMs is oblivious to chemical details, and are solely determined by the number of orbitals L and the number of electrons Ne. Moreover, the dynamics of the diagonal entries is independent of that of the off-diagonal entries. For an intuitive understanding of this, it resembles a “mass transport" process from higher energy orbitals to lower energy orbitals. Therefore, the change in occupation number of each orbital is influenced by the electronic population of other orbitals, leading to the appearance of 2-RDM related terms in the equations (see Fig. 4).

Given that the equations of motion of the entries of the 1-RDM are not closed, it is more challenging to analyze the convergence rate of the Type-II settings. Nonetheless, we may provide a qualitative estimation of the convergence rate using mean-field approximation. Let us first focus on the diagonal elements. For both r > s and r < s, applying the mean-field approximation to Eq. (25) results in the following linear homogeneous equation:

So under the mean-field approximation, the off-diagonal entry \({\widetilde{P}}_{sr}\) converges exponentially to zero with an exponent of at least \(\frac{1}{2}\), since Mk is positive semidefinite for any k.

For the diagonal entries, applying the mean-field approximation on Eq. (26) gives:

Note that Mk ≽ 1 for all r < Ne and r > Ne + 1, the convergence rates of the off-diagonal 1-RDM entries are exponential with the exponent of at least 1. The case r ∈ {Ne, Ne + 1} is beyond the mean-field analysis. As will be shown later, these convergence rate arguments can be verified numerically. A detailed explanation of the results above can be found in Section IV the SI.

Spectral gap of the Lindbladian in HF theory

In this section, we provide a direct characterization of the spectral gap of the Lindbladian. The definition of the spectral gap of the Lindbladian is

Briefly speaking, the inverse spectral gap of the Lindblad generator provides an estimate for an upper bound on the mixing time, up to logarithmic factors in the error tolerance and constants depending on the stationary state32,54.

Consider the following Hamiltonian, which corresponds to the dissipative part of the Lindblad dynamics,

Since for every jump operator \({\hat{K}}_{k}\left\vert {\psi }_{0}\right\rangle =0\), by construction, \({\hat{H}}_{{\rm{dp}}}\) can be viewed as a frustration-free parent Hamiltonian of the ground state \(\left\vert {\psi }_{0}\right\rangle\). We have the following theorem (the proof is given in Section V in the SI).

Theorem 1

If \([\hat{H},{\hat{H}}_{{\rm{dp}}}]=0\), then the spectral gap of the Lindbladian \({\mathcal{L}}\) is equal to the gap of \({\hat{H}}_{{\rm{dp}}}\).

In the HF setting, we have established that the equation of motion of the 1-RDM in the molecular orbital basis is independent of chemical details. Now we prove a stronger result, which states that the spectral gap of the Lindbladian is rigorously bounded from below using Type-I and Type-II jump operators in HF theory.

For Type-I jump operators, by calculating \({\hat{H}}_{{\rm{dp}}}\) in the molecular orbital basis (see Section V in SI for details), we obtain

where np, nq are number operators and commute with \(\hat{H}\), which is diagonal in the molecular orbital basis. Applying 1, we find that the spectral gap of the Lindbladian is the same as the gap of \({\hat{H}}_{{\rm{dp}}}\), which is equal to \(\frac{1}{2}\).

For Type-II jump operators, from previous calculations,

which again only consists of number operators. Applying 1, we find that the spectral gap of the Lindbladian is also equal to \(\frac{1}{2}\).

For thermal state preparation, an estimate of the spectral gap provides a direct upper bound on the mixing time of the Lindblad dynamics in trace distance32. This relationship, however, assumes that the stationary state is invertible, which is not satisfied by the ground state density matrix. In practice, we observe that the convergence rate of observables aligns closely with the spectral gap analysis and does not exhibit dependence on system size.

Numerical verification in the HF setting

In this section, we numerically verify the convergence rate of observables, such as energy and 1-RDM at the HF level. The detailed implementation of these numerical tests can be found in Section VI in the SI.

Using the Type-I set, Fig. 5a shows that the convergence of the energy towards the ground state energy follows a universal relation \(\exp (-t)\), for any molecule in any basis set. This is because the effect of the collection action of the jump operators is to independently adjust the occupation number of each molecular orbital, until the aufbau principle is reached. We perform each simulation by propagating the 1-RDM according to Eq. (9) using the DOPRI5 solver.

a Convergence of energy using the Type-I set for Hartree-Fock state preparation of the molecules H4, LiH, H2O, CH4, \({\rm{HCN}}\), C2H4, N2, H10 and SO3. The y-axis is displayed on a logarithmic scale. The convergence rate is universal. The dashed lines represent the convergence of energy for different molecules, while the solid green line shows the exponential decay \(\exp (-t)\). b Convergence of energy using the Type-II set for F2, LiH and H4 molecules (square and chain geometries) in STO-3G and STO-6G. The convergence rate only depends on the number of orbitals and the number of electrons. The dashed lines represent STO-3G results, and the dash-dotted lines represent STO-6G results, for F2, LiH, and H4 (square and chain geometries).

Figure 5b shows the convergence rate of the energy using the Type-II set. The test systems are F2 (1.4 Å), LiH (1.546 Å), chain H4 (2.0 Å) and square H4 (2.0 Å) using STO-3G and STO-6G basis sets. For each molecule, STO-3G and STO-6G have the same number of orbitals and electrons. The two isomers of H4 also share the same number of orbitals and electrons. We observe that the convergence of the systems with the same L and Ne are exactly identical up to renormalization, but it varies across those molecules with different numbers, indicating a nontrivial dependence on both L and Ne. In each system, we perform the simulation by directly propagating the many-body density operator using DOPRI5 solver in the number-preserving sector with random initialization.

To further examine the convergence rate, we track the evolution of the diagonal and off-diagonal entries of the 1-RDM for the H4 within STO-3G, as shown in Fig. 6. From Fig. 6a, b, we see that the convergence rates of the diagonal entries are faster than \(\exp (-t)\) except for the highest occupied molecular orbital (HOMO) and the lowest unoccupied molecular orbital (LUMO). Additionally, the off-diagonal entries exhibit convergence exponents of at least \(\frac{1}{2}\). All of the numerical results are in very good agreement with the mean-field analysis discussed previously.

It is tested on the H4 system in STO-3G. a Convergence of the diagonal entries \({\widetilde{P}}_{rr}=\langle {n}_{r}\rangle\) of the 1-RDM for r≤Ne. The colored dashed lines are diagonal entries that increase faster than the exponential reference \(\exp (-t)\) (solid purple). The solid red line corresponds to the growth of the HOMO occupation number. b Convergence of the diagonal entries \({\widetilde{P}}_{rr}=\langle {n}_{r}\rangle\) of the 1-RDM for r≥Ne + 1. The colored dashed lines are diagonal entries that decrease faster than the exponential reference \(\exp (-t)\) (solid purple). The solid blue line corresponds to the decay of the LUMO occupation number. c Convergence of the off-diagonal entries of the 1-RDM. We plot \(| {\widetilde{P}}_{ij}| /| {\widetilde{P}}_{ij}(0)|\) for each curve. The dashed lines represent the decay of off-diagonal entries, which all converge faster than the exponential reference \(\exp (-t/2)\) shown in green solid line.

Transferability to full ab initio calculations

Both Type-I and Type-II coupling operators can be readily applied in full ab initio calculations. However, the jump operators are no longer linear or quadratic in fermionic operators. This is because, in the ab initio Hamiltonian

the presence of quartic terms prevent us from applying the Thouless theorem to simplify the Heisenberg evolution of the coupling operators \(A(s)={e}^{{\rm{i}}\hat{H}s}A{e}^{-{\rm{i}}\hat{H}s}\), as in Equations (7), (8) and (19). Consequently, unlike in the HF Hamiltonian setting, we cannot expect to obtain analytic or semi-analytic solutions for the dynamics of physical observables like energy or reduced density matrices. To conceptually demonstrate the transferability of our approach to full ab initio calculations, we, therefore, perform numerical simulations of the Lindblad dynamics with Types I and II jump operators in the FCI space.

For small-sized systems up to 12 spin orbitals, we may choose to propagate a many-body density operator, or a stochastic wavefunction by “unraveling” Lindblad dynamics and performing stochastic averages (see the Methods section as well as Section VI in SI), in the Fock space or in the FCI space. For systems of larger sizes, the only feasible option for direct simulation is to simulate the stochastic wavefunction using Type-II jump operators in the FCI space. We quantify the convergence of the Lindblad dynamics based on the rate of energy convergence.

We note that both Types I and II sets involve a large number of jump operators, which can lead to increased simulation costs. However, in practice, the number of jump operators can be significantly reduced with minimal impact on efficiency. This is because the primary challenges in simulating chemical systems often arise in the low-energy space, particularly near the Fermi surface when we start with the HF initial guess. As a result, we can apply “active space” techniques to reduce the number of jump operators, focusing only on the most relevant degrees of freedom. For instance, if we start from the vacuum state, it is unnecessary to include all operators from the set \({{\mathcal{A}}}_{{\rm{I}}}={\{{a}_{p}\}}_{p = 1}^{2L}\cup {\{{a}_{p}^{\dagger }\}}_{p = 1}^{2L}\), as the HF state is confined to the low-energy sector. Therefore, we can instead select the subset \({{\mathcal{S}}}_{{\rm{I}}}^{r}={\{{c}_{i,\uparrow },{c}_{i,\uparrow }^{\dagger },{c}_{i,\downarrow },{c}_{i,\downarrow }^{\dagger }\}}_{i = {N}_{{\rm{e}}}-r+1}^{{N}_{{\rm{e}}}+r}\), which includes only the 8r operators defined around the Fermi surface under the molecular orbital basis.

We perform the numerical tests for \({{\mathcal{S}}}_{{\rm{I}}}^{r}\). In all of the four systems demonstrated in Fig. 7, we choose the initial state to be the HF state. We observe that energy decreases to λ0 with a fidelity within the chemical accuracy, which shows a good transferability of the active space reduction idea to full ab initio calculations for the Type-I setting.

Tested systems are: a H2 at bond length 0.7 Å in STO-3G, b H2 at bond length 0.7 Å in 6-31G, c chain-like H4 at bond length 0.7 Å in STO-3G and d chain-like H6 at bond length 0.7 Å in STO-3G. We choose \({{\mathcal{S}}}_{{\rm{I}}}^{r}\) as the coupling matrices with r = 1, 1, 1, 2 respectively and initialize with \(\left\vert {\rm{HF}}\right\rangle\) in all of the four cases. In each panel, the red line represents the energy as a function of time, and the blue line indicates the ground-state energy of the corresponding system.

Similarly, for the Type-II set, we can start from the HF state or low-excited Slater determinant and include only the jump operators defined on a small number of orbitals around the Fermi surface. In this case, we consider the following reduced set of particle-number preserving coupling operators

which has 16r2 coupling operators in total. In practice, setting r = 1 or r = 2 is typically sufficient to achieve convergence of the system to its ground state. The corresponding numerical results are presented in Fig. 8. To compare the convergence rates of the full ab initio and HF state preparation with the reduced set \({{\mathcal{S}}}_{{\rm{II}}}^{r}\), we begin from the (triplet) excited Slater determinant \({c}_{{N}_{{\rm{e}}}+1,\uparrow }^{\dagger }{c}_{{N}_{{\rm{e}}},\downarrow }\left\vert {\rm{HF}}\right\rangle\). Notably, the convergence rate of the full ab initio state preparation is observed to be not much slower than that of the HF method, in the sense of Lindblad simulation time required to reach chemical accuracy.

In all cases, we initialize with the (triplet) excited Hartree-Fock Slater determinant \({c}_{{N}_{{\rm{e}}}+1,\uparrow }^{\dagger }{c}_{{N}_{{\rm{e}}},\downarrow }\left\vert {\rm{HF}}\right\rangle\). a–f display results for the H2, F2, LiH, Cl2, H2O, and BeH2 molecules, respectively. In each panel, the orange line and the green line represent the energy as a function of time using the \({{\mathcal{S}}}_{{\rm{II}}}^{r}\) and \({{\mathcal{T}}}_{{\rm{II}}}^{r}\) sets respectively, while the blue line indicates the ground-state energy of the corresponding system. g presents the Lindblad simulation time required to achieve chemical accuracy with full ab initio and simplified Hartree-Fock Hamiltonians. The orange and green bars represent the FCI simulation time using the \({{\mathcal{S}}}_{{\rm{II}}}^{r}\) and \({{\mathcal{T}}}_{{\rm{II}}}^{r}\) sets, respectively, while the red bars and blue bars represent the Hartree-Fock simulation time using the \({{\mathcal{S}}}_{{\rm{II}}}^{r}\) set and the \({{\mathcal{T}}}_{{\rm{II}}}^{r}\) set, respectively.

In fact, the set of Type-II orbitals can be further compressed. For instance, we may take the subset \({{\mathcal{T}}}_{{\rm{II}}}^{r}\) of \({{\mathcal{S}}}_{{\rm{II}}}^{r}\) that contains only the hopping between nearest energy levels of molecular orbitals:

The number of operators in \({{\mathcal{T}}}_{{\rm{II}}}^{r}\) increases only linearly with L for fixed r. The numerical convergence behaviors \({{\mathcal{T}}}_{{\rm{II}}}^{r}\) are shown in Fig. 8. We observe that the further compression of \({{\mathcal{S}}}_{{\rm{II}}}^{r}\) maintains the simulation efficiency, in the sense that the Lindblad simulation time required to achieve chemical accuracy with the \({{\mathcal{T}}}_{{\rm{II}}}^{r}\) set remains comparable to or only slightly longer than that needed with the \({{\mathcal{S}}}_{{\rm{II}}}^{r}\) set.

The ground state preparation via Lindbladians with the set \({{\mathcal{T}}}_{{\rm{II}}}^{r}\) can perform well even in strongly correlated systems where the HF state poorly approximates the true ground state. Examples like the stretched square H4 highlight these challenges due to their nearly degenerate low energy states, which even highly accurate methods like CCSD(T), often referred to as the “gold standard" in molecular quantum chemistry, struggle with refs. 55,56,57. Our results show that Lindblad dynamics effectively captures the correlation energy. As shown in Fig. 9a, as the bond length of the square H4 system increases, the energy accuracy of the HF initial guess decreases. Concurrently, the initial overlap between the HF state and the true ground state diminishes, indicating a growing extent of strong correlation. However, as illustrated in Fig. 9b, the convergence of Lindblad dynamics remains largely unaffected by the degree of strong correlation starting from the HF initial state at various bond lengths. Meanwhile, we observe that increasing the extent of strong correlation leads to slower asymptotic convergence of the Lindblad dynamics. Specifically, as shown in Fig. 9c, at bond lengths where the Hamiltonian gap \({\Delta }_{\hat{H}}\) (i.e., the gap between the ground and first excited state energies) becomes smaller, the spectral gap of the Lindbladian is also reduced. Correspondingly, the exponential fitting results in Fig. 9b demonstrate slower asymptoticconvergence rates. These observations suggest that stronger correlations in molecular systems can lead to slower convergence to the ground state.

a The accuracy of the HF, CCSD and CCSD(T) energy and the initial overlap between the HF state and the true ground state ρg at different bond lengths for square H4 system in STO-3G. The green, yellow, and purple lines show the energy errors from HF, CCSD, and CCSD(T), respectively; the blue line shows the initial overlap, and the red dashed line marks chemical accuracy. b The energy error relative to FCI energy vs. Lindblad simulation time at bond lengths d = 1.2, 1.4, 1.6, and 2.0 Å. The solid lines (blue, orange, green, red) represent Lindblad dynamics at bond lengths d = 1.2, 1.4, 1.6, and 2.0 Å; the red dotted line indicates chemical accuracy, and the dashed lines show the fitting. c The spectral gaps of the Lindbladian \({\mathcal{L}}\) and the Hamiltonian at bond lengths d = 1.2, 1.4, 1.6 and 2.0 Å. The blue line denotes the Lindbladian gap \({\Delta }_{{\mathcal{L}}}\), while the orange line denotes the Hamiltonian gap \({\Delta }_{\hat{H}}\).

It is also noteworthy that in Fig. 9b, the behaviors at short and long bond lengths are different. At short bond lengths, the pre-asymptotic decay is relatively rapid and the error quickly falls below chemical accuracy, making the preparation appear easier. In contrast, at long bond lengths, the pre-asymptotic decay is shorter-lived and the convergence is dominated by the smaller spectral gap, requiring a longer time to reach chemical accuracy.

Discussion

To our knowledge, this work is the first Lindblad-based ground state preparation algorithm for ab initio electronic structure calculations. The Lindblad dynamics is employed as an algorithmic tool for dissipative state engineering, which can be constructed without relying on variationally adjusted parameters. A notable advantage of this approach is that the effectiveness of the method can be nearly independent of the quality of the initial state. This stands in sharp contrast to QPE, whose cost depends directly on the initial state’s overlap with the target state and can fail if this overlap vanishes. The “shoveling” process in dissipative state preparation shares some conceptual similarities with various forms of imaginary time evolution (ITE)3,57,58,59,60,61,62,63, but also exhibits notable differences. A direct implementation of ITE through the application of \({e}^{-\tau \hat{H}}\) does not yield a CPTP map, and its quantum realization again requires nontrivial overlaps between the initial and target states. The quantum imaginary time evolution (QITE) algorithm3 addresses some of these challenges, but it relies on a tomography procedure and its cost can scale explicitly exponentially with system size.

In the dissipative state preparation framework, we prove that the Lindblad dynamics with Types I and II jump operators can converge rapidly in a simplified HF setting, and validate the transferability to full ab initio calculations even for systems exhibiting strong correlation behaviors. In order to perform numerical simulation for larger systems with tens to hundreds of spin-orbitals, even propagating the state vector in the FCI space can be very costly, and advanced simulation methods, such as quantum Monte Carlo methods or tensor network-based methods must be employed. For practical implementation on quantum devices, the simulation of Lindblad dynamics involves repeatedly applying circuit blocks with intermediate measurements, continuing until the dynamics approach a fixed point. As a result, a large mixing time in certain systems can lead to a substantial overall simulation cost. It is, therefore, important to develop a stronger theoretical framework for analyzing convergence rates in the ground state preparation problem. Recent progress in this direction can be found in ref. 64. This work may also provide new perspectives of ground state preparation in other areas, such as nuclei physics, fermions with random coefficients (e.g., the SYK model), or optimization problems on unstructured graphs.

Methods

Choice of filter function and sketch of quantum simulation algorithm

In this section, we discuss the choice of filter function in ref. 25 and briefly review quantum algorithms for simulating the Lindblad dynamics.

We begin by reviewing the definition of the jump operator \({\hat{K}}_{k}\). Since the eigenvectors of \(\hat{H}\) are typically not accessible, we express \({\hat{K}}_{k}\) in the time domain as follows:

where \({A}_{k}(s)={e}^{{\rm{i}}\hat{Hs}}{A}_{k}{e}^{-{\rm{i}}\hat{Hs}}\) is the Heisenberg evolution of Ak and \(f(s)=\frac{1}{2\pi }{\int}_{{\mathbb{R}}}\hat{f}(\omega ){e}^{-{\rm{i}}\omega s}{\rm{d}}\omega\) is the inverse Fourier transform of the filter \(\hat{f}\) in the frequency domain. One possible choice for the filter function in the frequency domain \(\hat{f}\) is given by the following form25

where \({\rm{erf}}(\omega ):= \mathop{\int}\nolimits_{0}^{\omega }\frac{2}{\sqrt{\pi }}{e}^{-{t}^{2}}{\rm{d}}t\) denotes the error function. Here, a is chosen to be an energy cutoff satisfying \(a > 2\parallel \hat{H}{\parallel }_{2}\) and b is chosen to be the spectral gap of the Hamiltonian Δ ≔ λ1 − λ0. The parameters δa and δb are chosen to be on the same order of a and b, respectively. In this setup, \(\hat{f}\) is approximately supported on the interval \([-2\parallel \hat{H}{\parallel }_{2},-\Delta ]\) (Note that the largest eigenvalue difference is \(| {\lambda }_{i}-{\lambda }_{j}| \le 2\parallel \hat{H}{\parallel }_{2}\)). The inverse Fourier transform f can also be computed analytically as

where \(f(0)=\frac{a-b}{2\pi }\) is obtained by taking the limit s → 0. f(s) is a smooth complex-valued function with the modulus ∣f(s)∣ exhibiting a rapid decay when ∣s∣ → ∞. Specifically, f(s) approximately vanishes when ∣s∣ > Ss for some Ss = Θ(1/Δ), which allows us to truncate the infinite integral and use the trapezoidal quadrature rule to approximate the jump operator \({\hat{K}}_{k}\):

where Ms is the number of quadrature nodes on [0, Ss] or [ − Ss, 0], sl = lΔs and Δs = Ss/Ms. The weights {wl} are chosen to be Δs/2 for l = ± Ms and Δs for − Ms + 1 ≤ l ≤ Ms − 1.

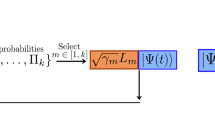

To simulate the Lindblad dynamics \(\exp ({\mathcal{L}}t)\) on quantum devices, we can begin with a first order Trotter splitting \(\exp ({\mathcal{L}}t)\approx {(\exp ({{\mathcal{L}}}_{H}\tau )\cdot \exp ({{\mathcal{L}}}_{K}\tau ))}^{t/\tau }\). The coherent dynamics \(\exp ({{\mathcal{L}}}_{H}\tau )\) is just the Hamiltonian simulation \(\exp (-{\rm{i}}\hat{H}\tau )\). For the nonunitary dissipative part \(\exp ({{\mathcal{L}}}_{K}\tau )\), we can reduce this problem to a dilated Hamiltonian simulation up to a partial trace on the ancilla qubit, namely

Here, \({{\rm{Tr}}}_{a}\) denotes the partial trace operation on the ancilla qubit. For simplicity we consider only one jump operator K, and \(\widetilde{K}\) is defined by the Hermitian dilated matrix \(\widetilde{K}=\left(\begin{array}{cc}0&{K}^{\dagger }\\ K&0\end{array}\right)\). Then the dilated Hamiltonian simulation \({e}^{{\rm{i}}\widetilde{K}\sqrt{\tau }}\) can be efficiently performed on a quantum computer using a second-order Trotter splitting according to the discretized time evolution of K shown in Eq. (39) (see ref. 25, Section III for details).

Review of HF theory in the second quantized representation

The HF theory finds a self-consistent single-particle operator approximation to the many-body Hamiltonian taking the form

Here L is the number of spatial orbitals, and 2L is the number of spin orbitals. The operators \({a}_{p}^{\dagger }\) and ap are fermionic creation and annihilation operators with respect to the orthonormalized spin orbitals. Here, hpq is a fixed single-particle matrix. The direct Coulomb and Fock exchange terms, denoted by Vpq and Kpq, respectively, should be solved self-consistently with respect to the one-particle density matrix (1-RDM), defined as

Here \(\Phi \in {{\mathbb{C}}}^{2L\times 2L}\) is a unitary matrix called the molecular orbital coefficients, which are eigenfunctions of the Fock matrix F. We denote FΛ = ΛΦ with Λ = diag(ε1, ⋯ , ε2L).

Once D is fixed, the HF Hamiltonian in Eq. (41) is a quadratic Hamiltonian. Its ground state has an explicit expression in the Slater-determinant form:

where the new set of creation operators \(\{{c}_{i}^{\dagger }\}\) are given by the unitary transform of \(\{{a}_{i}^{\dagger }\}\) via

Note that \(\left\vert {\rm{HF}}\right\rangle\) is the ground state of the converged Hamiltonian \({\hat{H}}_{{\rm{HF}}}\) with eigenvalue \({E}_{0}=\mathop{\sum }\nolimits_{k = 1}^{{N}_{{\rm{e}}}}{\varepsilon }_{k}\). This sum of eigenvalues can also be expressed as \({\rm{Tr}}(FD)\), which differs from the HF energy by a nonlinear term that depends only on D.

Monte-Carlo trajectory-based method for unraveled Lindblad dynamics

To solve the Lindblad dynamics for ground state preparation at the FCI level, we may directly propagate the many-body density operator \(\rho (t)\in {{\mathbb{C}}}^{{2}^{L}\times {2}^{L}}\) using a differential equation solver65. Another approach is to “unravel” the Lindblad dynamics for the many-body density operator66,67. Broadly speaking, we employ a family of Monte-Carlo-type algorithms where we only propagate the state vector \(\left\vert \psi (t)\right\rangle\) in some stochastic schemes, and the many-body density operator ρ(t) at the time t can be retrieved by taking the average of the random matrix \(\left\vert \psi (t)\right\rangle \left\langle \psi (t)\right\vert\), i.e., \(\rho (t)={\mathbb{E}}\left\vert \psi (t)\right\rangle \left\langle \psi (t)\right\vert .\) The deterministic Lindblad equation for the dynamics of the many-body density operator is now expressed using stochastic pure-state trajectories, thus leading to a quadratic reduction in dimensionality, at the cost of incorporating statistical averaging across multiple runs.

The simplest setting is the discrete form of unraveling, or quantum jump method68. The quantum-jump pure-state dynamics are evolved under an effective non-Hermitian Hamiltonian \(\hat{H}-{\rm{i}}/2{\sum }_{k}{\hat{K}}_{k}^{\dagger }{\hat{K}}_{k}\), with stochastic quantum jumps occurring intermittently throughout the evolution. Specifically, it can be described by the following stochastic differential equation (SDE):68,69,70

Here, Nt denotes a Poisson process with a splitting \({N}_{t}={\sum }_{k}{N}_{t}^{k}\). For a sufficiently small time step Δt, the Poisson increment ΔNt takes the values 0 (no jump) or 1 (jump) with expectation value \({\mathbb{E}}(\Delta {N}_{t})={\sum }_{k}{\parallel \hat{{K}_{k}}\psi \parallel }^{2}\Delta t={\sum }_{k}\langle {\hat{K}}_{k}^{\dagger }{\hat{K}}_{k}\rangle \Delta t\). The Poisson processes \(\{{N}_{t}^{k}\}\) are mutually independent with intensities given by \({\parallel \hat{{K}_{k}}\psi \parallel }^{2}=\langle {\hat{K}}_{k}^{\dagger }{\hat{K}}_{k}\rangle\). This implies that, in the event of a jump, we select the jump operator \({\hat{K}}_{k}\) to apply to ψ with a probability proportional to \(\langle {\hat{K}}_{k}^{\dagger }{\hat{K}}_{k}\rangle\) for k = 1, 2, ⋯ , N. It can be shown that the density operator, defined as \(\rho (t)={\mathbb{E}}\left\vert \psi (t)\right\rangle \left\langle \psi (t)\right\vert\) indeed solves the Lindblad dynamics, by calculating \(\frac{{\rm{d}}\psi {\psi }^{\dagger }}{{\rm{d}}t}\) using Itô’s lemma for the Poisson process and then taking the expectation.

For a Monte-Carlo-type simulation of Eq. (45), we first discretize the time interval by the time step Δt. Then at each step, we randomly pick up k ∈ [N + 1] (assume we have N jump operators in total) with respect to the distribution

If k = 1, ⋯ , N, we update the trajectory using \({\psi }_{n+1}={\hat{K}}_{k}{\psi }_{n}/\langle {\hat{K}}_{k}^{\dagger }{\hat{K}}_{k}\rangle\). If K = N + 1, we update using \({\psi }_{n+1}={\psi }_{n}-({\rm{i}}\hat{H}+\frac{1}{2}{\sum }_{k}{\hat{K}}_{k}^{\dagger }{\hat{K}}_{k}){\psi }_{n}\Delta t\). Then, the many-body density operator ρ(tn) at time tn can be approximated by taking the average of the pure states \(\left\vert \psi ({t}_{n})\right\rangle \left\langle \psi ({t}_{n})\right\vert\) over the trajectories65.

We can also consider a variant of the Monte Carlo-type algorithm that is slightly different but essentially equivalent to the one described above. Notice that65

which implies that the decaying evolution governed by the non-Hermitian effective Hamiltonian primarily dictates the probability distribution. Consequently, we actually do not need to compute \({\parallel {\hat{K}}_{k}{\psi }_{n}\parallel }^{2}\) at every time step. Instead, we can first calculate \({\parallel {\psi }_{n}\parallel }^{2}\) and sample a random number R ~ U(0, 1) to decide whether jump or not. If \(R < {\parallel {\psi }_{n}\parallel }^{2}\), we just propagate the trajectory using \({\psi }_{n+1}={\psi }_{n}-\left({\rm{i}}\hat{H}+\frac{1}{2}{\sum }_{k}{\hat{K}}_{k}^{\dagger }{\hat{K}}_{k}\right){\psi }_{n}\Delta t\). If \(R\ge {\parallel {\psi }_{n}\parallel }^{2}\), we calculate each \(\langle {\hat{K}}_{k}^{\dagger }{\hat{K}}_{k}\rangle\) and update \({\psi }_{n+1}=\hat{{K}_{k}}{\psi }_{n}/\langle {\hat{K}}_{k}^{\dagger }{\hat{K}}_{k}\rangle\) with a probability proportional to \(\langle {\hat{K}}_{k}^{\dagger }{\hat{K}}_{k}\rangle\) for k = 1, 2, ⋯ , N. After this, we reset the random number R ~ U(0, 1). Essentially, this corresponds to evolving the trajectory using \(\hat{H}-{\rm{i}}/2{\sum }_{k}{\hat{K}}_{k}^{\dagger }{\hat{K}}_{k}\) deterministically causing the norm of ψ to decrease, until a random quantum jump occurs. At this point, the norm is restored to 1, and the process repeats52.

In all of the steps in the unraveling algorithm, only matrix-vector multiplication is involved.

Data availability

The data that support this study are available upon request. The codes that support this study are available on GitHub via https://github.com/haoen2021/LindbladAbInitio.

Code availability

The codes that support this study are available on GitHub via https://github.com/haoen2021/LindbladAbInitio.

References

Aspuru-Guzik, A., Dutoi, A. D., Love, P. J. & Head-Gordon, M. Simulated quantum computation of molecular energies. Science 309, 1704–1707 (2005).

Verstraete, F., Wolf, M. M. & Cirac, I. Quantum computation and quantum-state engineering driven by dissipation. Nat. Phys. 5, 633–636 (2009).

Motta, M. et al. Determining eigenstates and thermal states on a quantum computer using quantum imaginary time evolution. Nat. Phys. 16, 205–210 (2020).

Albash, T. & Lidar, D. A. Adiabatic quantum computation. Rev. Mod. Phys. 90, 015002 (2018).

Cerezo, M. et al. Variational quantum algorithms. Nat. Rev. Phys. 3, 625–644 (2021).

Zhang, X.-M., Li, T. & Yuan, X. Quantum state preparation with optimal circuit depth: implementations and applications. Phys. Rev. Lett. 129, 230504 (2022).

O’Brien, T. E., Tarasinski, B. & Terhal, B. M. Quantum phase estimation of multiple eigenvalues for small-scale (noisy) experiments. New J. Phys. 21, 023022 (2019).

Ge, Y., Tura, J. & Cirac, J. I. Faster ground state preparation and high-precision ground energy estimation with fewer qubits. J. Math. Phys. 60, 022202 (2019).

Lin, L. & Tong, Y. Near-optimal ground state preparation. Quantum 4, 372 (2020).

Lin, L. & Tong, Y. Heisenberg-limited ground state energy estimation for early fault-tolerant quantum computers. PRX Quantum 3, 010318 (2022).

Wan, K., Berta, M. & Campbell, E. T. Randomized quantum algorithm for statistical phase estimation. Phys. Rev. Lett. 129, 030503 (2022).

Dutkiewicz, A., Terhal, B. M. & O’Brien, T. E. Heisenberg-limited quantum phase estimation of multiple eigenvalues with few control qubits. Quantum 6, 830 (2022).

Ding, Z. & Lin, L. Even shorter quantum circuit for phase estimation on early fault-tolerant quantum computers with applications to ground-state energy estimation. PRX Quantum 4, 020331 (2023).

Lee, S. et al. Evaluating the evidence for exponential quantum advantage in ground-state quantum chemistry. Nature Comm. 14, 1952 (2023).

Berry, D. W. et al. Rapid initial state preparation for the quantum simulation of strongly correlated molecules. PRX Quantum 6, 020327 (2025).

Kraus, B. et al. Preparation of entangled states by quantum markov processes. Phys. Rev. A 78, 042307 (2008).

Zhou, L., Choi, S. & Lukin, M. D. Symmetry-protected dissipative preparation of matrix product states. Physical Review A 104, 032418 (2021).

Cubitt, T. S. Dissipative ground state preparation and the dissipative quantum eigensolver. arXiv preprint arXiv:2303.11962 (2023).

Wang, Y., Snizhko, K., Romito, A., Gefen, Y. & Murch, K. Dissipative preparation and stabilization of many-body quantum states in a superconducting qutrit array. Phys. Rev. A 108, 013712 (2023).

Lu, T.-C., Lessa, L. A., Kim, I. H. & Hsieh, T. H. Measurement as a shortcut to long-range entangled quantum matter. PRX Quantum 3, 040337 (2022).

Foss-Feig, M. et al. Experimental demonstration of the advantage of adaptive quantum circuits. arXiv preprint arXiv:2302.03029 (2023).

Kalinowski, M., Maskara, N. & Lukin, M. D. Non-Abelian Floquet Spin Liquids in a Digital Rydberg Simulator. Phys. Rev. X 13, 31008 (2023).

Mozgunov, E. & Lidar, D. Completely positive master equation for arbitrary driving and small level spacing. Quantum 4, 1–62 (2020).

Chen, C.-F. & Brandão, F. G. S. L. Fast thermalization from the eigenstate thermalization hypothesis. arXiv preprint arXiv:2112.07646 (2023).

Ding, Z., Chen, C.-F. & Lin, L. Single-ancilla ground state preparation via Lindbladians. Phys. Rev. Research 6, 033147 (2024).

Rall, P., Wang, C. & Wocjan, P. Thermal State Preparation via Rounding Promises. Quantum 7, 1132 (2023).

Chen, C.-F., Kastoryano, M. J., Brandão, F. G. & Gilyén, A. Quantum thermal state preparation. arXiv preprint arXiv:2303.18224 (2023).

Chen, C.-F., Kastoryano, M. J. & Gilyén, A. An efficient and exact noncommutative quantum Gibbs sampler. arXiv preprint arXiv:2311.09207 (2023).

Ding, Z., Li, B. & Lin, L. Efficient quantum Gibbs samplers with Kubo–Martin–Schwinger detailed balance condition. Commun. Math. Phys. 406, 67 (2025).

Gilyén, A., Chen, C.-F., Doriguello, J. F. & Kastoryano, M. J. Quantum generalizations of Glauber and Metropolis dynamics. arXiv preprint arXiv:2405.20322 (2024).

Ding, Z., Li, B., Lin, L. & Zhang, R. Polynomial-time preparation of low-temperature Gibbs states for 2d toric code. arXiv preprint arXiv:2410.01206 (2024).

Temme, K., Kastoryano, M. J., Ruskai, M. B., Wolf, M. M. & Verstraete, F. The χ2-divergence and mixing times of quantum Markov processes. J. Math. Phys. 51, 122201 (2010).

Kastoryano, M. J. & Temme, K. Quantum logarithmic Sobolev inequalities and rapid mixing. J. Math. Phys. 54, 052202 (2013).

Bardet, I. et al. Rapid thermalization of spin chain commuting Hamiltonians. Phys. Rev. Lett. 130, 060401 (2023).

Kastoryano, M. J. & Brandao, F. G. Quantum Gibbs samplers: the commuting case. Communications in Mathematical Physics 344, 915–957 (2016).

Temme, K., Pastawski, F. & Kastoryano, M. J. Hypercontractivity of quasi-free quantum semigroups. Journal of Physics A: Mathematical and Theoretical 47, 405303 (2014).

Temme, K. Thermalization time bounds for Pauli stabilizer Hamiltonians. Communications in Mathematical Physics 350, 603–637 (2017).

Bardet, I. et al. Entropy decay for Davies semigroups of a one dimensional quantum lattice. Commun. Math. Phys. 405, 42 (2024).

Alicki, R., Fannes, M. & Horodecki, M. On thermalization in Kitaev’s 2D model. J. Phys. A Math. Theoretical 42, 065303 (2009).

Davies, E. B. Markovian master equations. Commun. Math. Phys. 39, 91–110 (1974).

Lindblad, G. On the generators of quantum dynamical semigroups. Commun. Math. Phys. 48, 119–130 (1976).

Gorini, V., Kossakowski, A. & Sudarshan, E. C. G. Completely positive dynamical semigroups of n-level systems. J. Math. Phys. 17, 821–825 (1976).

Su, Y., Huang, H.-Y. & Campbell, E. T. Nearly tight Trotterization of interacting electrons. Quantum 5, 495 (2021).

Low, G. H., Su, Y., Tong, Y. & Tran, M. C. Complexity of implementing Trotter steps. PRX Quantum 4, 020323 (2023).

Su, Y., Berry, D. W., Wiebe, N., Rubin, N. & Babbush, R. Fault-tolerant quantum simulations of chemistry in first quantization. PRX Quantum 2, 040332 (2021).

Tong, Y., An, D., Wiebe, N. & Lin, L. Fast inversion, preconditioned quantum linear system solvers, fast Green’s-function computation, and fast evaluation of matrix functions. Phys. Rev. A 104, 032422 (2021).

Thouless, D. J. Stability conditions and nuclear rotations in the Hartree-Fock theory. Nuclear Phys. 21, 225–232 (1960).

Szabo, A. & Ostlund, N. S. Modern Quantum Chemistry: Introduction to Advanced Electronic Structure Theory (Courier Corporation, 2012).

Prosen, T. Third quantization: a general method to solve master equations for quadratic open Fermi systems. New J. Phys. 10, 043026 (2008).

Prosen, T. & Žunkovič, B. Exact solution of Markovian master equations for quadratic Fermi systems: thermal baths, open XY spin chains and non-equilibrium phase transition. New J. Phys. 12, 025016 (2010).

Horstmann, B., Cirac, J. I. & Giedke, G. Noise-driven dynamics and phase transitions in fermionic systems. Phys. Rev. A 87, 012108 (2013).

Barthel, T. & Zhang, Y. Solving quasi-free and quadratic Lindblad master equations for open fermionic and bosonic systems. J. Stat. Mech. Theory Exp. 2022, 113101 (2022).

Stefanucci, G. & Van Leeuwen, R.Nonequilibrium many-body theory of quantum systems: a modern introduction (Cambridge University, 2013).

Žnidarič, M. Relaxation times of dissipative many-body quantum systems. Phys. Rev. E 92, 042143 (2015).

Paldus, J., Piecuch, P., Pylypow, L. & Jeziorski, B. Application of Hilbert-space coupled-cluster theory to simple \({({{\rm{h}}}_{2})}_{2}\) model systems: planar models. Phys. Rev. A 47, 2738–2782 (1993).

Lee, J., Huggins, W. J., Head-Gordon, M. & Whaley, K. B. Generalized unitary coupled cluster wave functions for quantum computation. J. Chem. Theory Comput. 15, 311–324 (2018).

Huggins, W. J. et al. Unbiasing fermionic quantum Monte Carlo with a quantum computer. Nature 603, 416–420 (2022).

Zhang, S., Carlson, J. & Gubernatis, J. E. Constrained path quantum Monte Carlo method for fermion ground states. Phys. Rev. Lett. 74, 3652–3655 (1995).

Zhang, S. & Krakauer, H. Quantum Monte Carlo method using phase-free random walks with Slater determinants. Phys. Rev. Lett. 90, 136401 (2003).

Booth, G. H., Thom, A. J. W. & Alavi, A. Fermion Monte Carlo without fixed nodes: a game of life, death, and annihilation in Slater determinant space. J. Chem. Phys. 131, 054106 (2009).

McArdle, S. et al. Variational ansatz-based quantum simulation of imaginary time evolution. npj Quantum Inf. 5, 75 (2019).

Lee, J., Pham, H. Q. & Reichman, D. R. Twenty years of auxiliary-field quantum Monte Carlo in quantum chemistry: an overview and assessment on main group chemistry and bond-breaking. J. Chem. Theory Comput. 18, 7024–7042 (2022).

Jiang, T. et al. Walking through Hilbert space with quantum computers. Chem. Rev. 25, 4569–4602 (2025).

Zhan, Y. et al. Rapid quantum ground state preparation via dissipative dynamics. arXiv preprint arXiv:2503.15827 (2025).

Lidar, D. A. Lecture notes on the theory of open quantum systems. arXiv preprint arXiv:1902.00967 (2019).

Dalibard, J., Castin, Y. & Mølmer, K. Wave-function approach to dissipative processes in quantum optics. Phys. Rev. Lett. 68, 580 (1992).

Dum, R., Zoller, P. & Ritsch, H. Monte Carlo simulation of the atomic master equation for spontaneous emission. Phys. Rev. A 45, 4879–4887 (1992).

Christie, R., Eastman, J., Schubert, R. & Graefe, E.-M. Quantum-jump vs stochastic schrödinger dynamics for gaussian states with quadratic Hamiltonians and linear Lindbladians. J. Phys. A Math. Theor. 55, 455302 (2022).

Breuer, H.-P. & Petruccione, F.The theory of open quantum systems (Oxford University Press, 2002).

Moodley, M. & Petruccione, F. Stochastic wave-function unraveling of the generalized Lindblad master equation. Phys. Rev. A 79, 042103 (2009).

Acknowledgements

H.-E. L. acknowledges support from the National Natural Science Foundation of China (Grant No. 223B1011) and the Tsinghua Xuetang Talents Program for funding a summer visit to the University of California, Berkeley, and the High-Performance Computing Center of Tsinghua University for providing computational resources. Y. Z. acknowledges support from the Institute for Quantum Information and Matter, an NSF Physics Frontiers Center. L. L. acknowledges support from the U.S. Department of Energy, Office of Science, through the Accelerated Research in Quantum Computing Centers program (Quantum Utility through Advanced Computational Quantum Algorithms, Grant No. DE-SC0025572), and from the Simons Investigator in Mathematics program (Grant No. 825053).The authors thank Zhiyan Ding, Zhen Huang, and Jakob Huhn for helpful discussions.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

L.L. conceived the original study. H.-E. L. and L.L. carried out theoretical analysis to support the study. H.-E. L. and Y. Z. carried out numerical calculations to support the study. All authors discussed the results of the manuscript and contributed to the writing of the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Li, HE., Zhan, Y. & Lin, L. Dissipative ground state preparation in ab initio electronic structure theory. npj Quantum Inf 11, 183 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41534-025-01124-8

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41534-025-01124-8