Abstract

Solid-state qubits are sensitive to their microscopic environment, causing the qubit properties to fluctuate on a wide range of timescales. The sub-Hz end of the spectrum is usually dealt with by repeated background calibrations, which bring considerable overhead. It is thus important to characterize and understand the low-frequency variations of the relevant qubit characteristics. In this study, we investigate the stability of spin qubit frequencies in the Si/SiGe quantum dot platform. We find that the calibrated qubit frequencies of a six-qubit device vary by up to ±100 MHz while performing a variety of experiments over a span of 912 days. These variations are sensitive to the precise voltage settings of the gate electrodes, however when these are kept constant to within 15 µV, the qubit frequencies vary by less than ±7 MHz over periods up to 36 days. During overnight scans, the qubit frequencies of ten qubits across two different devices show a standard deviation below 200 kHz within a 1-hour time window. The qubit frequency noise spectral density shows roughly a 1/f trend above 10−4 Hz and, strikingly, a steeper trend at even lower frequencies.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

High-fidelity single1,2,3,4,5 and two-qubit gates5,6,7,8 have been demonstrated in semiconductor spin qubit platforms, motivating efforts towards large-scale quantum computing. Indeed, recent efforts have focused on increasing the size of quantum dot arrays9,10,11,12,13,14, but to retain universal control involves a large number of calibration parameters that typically outscale the number of qubits. As a case in point, in ref. 12. a calibration protocol of 108 different parameters was developed to demonstrate universal control of six qubits. Furthermore, these parameters were subject to slow variations over time, thus compromising the fidelity of state preparation, quantum gates, and measurement.

To overcome parameter variations in time, recent studies have aimed at efforts to implement feedback control or periodic recalibration to retain high fidelities3,12,15,16,17, similar to efforts with, for instance, superconducting qubits18 or trapped ions19. For successful feedback control, recalibration must occur on a timescale similar to or faster than the typical fluctuations of the calibrated parameters. In the semiconductor spin platform, for qubits encoded in the spin state of a single charge, one of the most important parameters to recalibrate periodically is the qubit frequency, because it impacts the calibration of many other parameters and empirically needs to be recalibrated more often than most other parameters5,12. Qubit frequency noise in semiconducting spin qubit platforms is typically attributed to two dominant sources: magnetic and charge noise. Magnetic noise arises predominantly from the nuclear spin bath, which couples to the qubit via the hyperfine interaction. For a dense bath of nuclear spins, the flip-flop rates between nuclear spins driven by the dipole-dipole interaction are high, causing a Brownian spin diffusion with a power spectral density Sm(f) that scales as 1/f2 20. This behavior has been observed in GaAs quantum dot qubits, where all atoms have a nuclear spin 3/221,22. Also in the silicon platform, nuclear spin noise can dominate dephasing despite the lower (4.7%) abundance of spinful nuclei23. However, isotopically purifying the active layer to remove spinful 29Si isotopes has proved effective in greatly increasing coherence times24. The larger average distance between the nuclear spins leads to reduced flip-flop rates, which manifests in a power spectral density closer to a 1/f-like scaling20,25,26.

Charge noise on the other hand couples to the qubit frequencies by perturbing the confinement potential of the quantum dot in combination with intrinsic or artificial spin-orbit coupling27,28. This noise is typically attributed to an ensemble of two-level fluctuators (TLFs) which, under certain assumptions, will manifest in a power spectral density Sc(f) with a 1/fα dependence with α ≈ 1 over a wide-frequency range29,30,31,32. Experimental data typically captures this behavior, however in ref. 33, a high-volume characterization of 231 charge noise measurements of Si/SiO2 quantum dots across many different devices reports charge noise profiles with varying values of α ∈ [0,2] over a frequency range of approximately [10−1,102] Hz. A characterization of charge noise in Si/SiGe over a much wider frequency range of approximately [10−6,106] Hz reveals a charge noise spectrum with a fluctuating value of α34. All these observations are consistent with coupling to a low-density ensemble of TLFs32. Depending on the distance of the TLF’s to the qubits, charge noise experienced by nearby qubits can exhibit both temporal and spatial correlations35,36,37,38.

Despite the many studies investigating the origin and power spectral density of spin qubit frequencies, it remains important to investigate the variation of qubit frequencies over periods of months to years, a timescale relevant for future quantum processors deployed at a customer site39.

In this study, we examine the stability of the resonance qubit frequency in two devices; a six-dot linear array and a four-dot 2 × 2 array, both defined within a 28Si/SiGe heterostructure. In the linear device, the qubit frequency stability is analyzed over a period of 912 days. For this analysis, we separate intrinsic qubit frequency variations in time from qubit frequency shifts resulting from changes in the gate voltages, the mixing chamber temperature, the applied magnetic field, and thermal cycles. In both devices, Ramsey experiments are utilized to track qubit frequency variations over time periods ranging from 10-41 hours, repeated for a total of 46 times over a data collection period lasting several months. We also discuss the impact of qubit frequency variations on the fidelity of a standard resonantly driven 90-degree qubit rotation in the Bloch sphere. Finally, we perform Fourier analysis on the obtained datasets to characterize the qubit frequency noise spectral density in the range of approximately [10−7,10−2] Hz.

Results

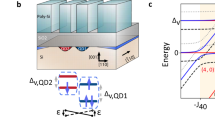

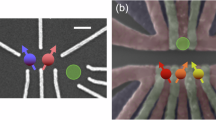

The two devices we study can host up to six and four qubits respectively, which we refer to as the linear12 and 2 × 240,41 devices. Nominally identical devices are depicted in Fig. 1a, b. Charges are isolated into quantum dots and an externally applied magnetic field induces a Zeeman splitting between the two spin states. Both devices employ two larger dots on the sides of the arrays for charge-sensing and utilize a Pauli spin blockade (PSB) protocol42 to implement parity readout that is used for both initialization and readout of single-spin qubits43. The magnetized micromagnet induces a gradient magnetic field across the quantum dot arrays which allows for frequency-selective qubit addressing and for the manipulation of individual spin qubits via electric-dipole spin resonance (EDSR)44. The EDSR Hamiltonian for a single spin qubit in the rotating frame (setting ℏ = 1) can be written in units of frequency as

where we define the qubit frequency detuning ∆(t) = f0 − fMW + η(t) as the difference between the qubit frequency at the time of calibration f0 and the microwave drive frequency fMW, with the added presence of qubit frequency noise η(t). Furthermore, Ω is the Rabi frequency (proportional to the microwave drive amplitude) and Φ sets the rotation axis in the rotating frame (which depends on the phase of the microwave drive). Finally, \(\hat{\sigma}_i\) are the standard Pauli matrices.

a, b False-colored scanning electron microscope images of two nominally identical devices to the ones used in the experiments. The linear device hosts six qubits, whilst the 2 × 2 device hosts four qubits. In both devices, the electron spin qubits reside beneath the plunger gates (P) as indicated by the white dashed circles. The barrier gates (B) are used to tune the tunnel coupling between adjacent dots and to the reservoirs. Screening gates (colored pink and with their contours indicated by dashed black lines) are used for extra confinement of the dots. The screening gate located nearest to the dots is also used to deliver microwave signals for EDSR driving. c Example of resonance frequency calibration scans for all six qubits in the linear device taken on the same day.

Qubit frequencies are calibrated by sweeping the frequency of the microwave burst to find the resonance condition as shown for the six qubits in the linear device in Fig. 1c. These scans are fitted to the Rabi formula

to extract the qubit frequency. Such calibration protocols are typically run on a daily basis.

Qubit frequency calibrations over 912 days

The linear device has been kept cold for several years, leading to multiple publications12,45,46. All data that has been collected, including calibration routines, is saved and indexed in a database, with each entry storing the experimental data and other relevant information (such as the dataset name, date, and time) in an accompanying metadata file. This archive serves as a useful resource to extract long-term trends in device behavior. We analyzed qubit frequency calibration scans such as those shown in Fig. 1c that were collected over a time span of 912 days (from 24/01/2022–24/07/2024). Each frequency scan was fitted to extract the qubit frequency, and all corresponding gate voltage settings were extracted from the experiment metadata file. The results are presented in Fig. 2.

A log of all six qubit frequencies (plotted in MHz deviations from the mean) and DC gate voltage settings in the linear device across a span of 912 days (from 24th Jan 2022–24th July 2024). The data points for the qubit frequencies are extracted from frequency scans as shown in Fig. 1c (see main text). Some days feature multiple data points whereas for other days none are recorded. Any time a frequency data point is plotted for at least one of the qubits, the gate voltage settings for the entire array are included in the plot as well. The four gray regions indicate periods when the fridge underwent a thermal cycle. The 16 red regions indicate periods of longer than seven days when no gate voltage was changed by more than 15 µV. The gates are labeled according to Fig. 1a. The tickmarks on the horizontal axis are positioned in the middle of the month. This dataset forms the basis for further analysis in subsequent figures.

The fitting of the frequency scans was evaluated with a chi-square metric, which calculates the squared sum difference between the experimental data and the model, to filter out any low-quality, hence unreliable, scans (i.e., any scans that had poor spin contrast, which made it difficult to reliably extract the qubit frequency). The plot only includes datapoints that passed this metric. For most of the 912 days, the magnetic field produced by the superconducting solenoid was set to 400 mT, but there were periods when the external field value was changed. Unfortunately, these changes were not logged. We therefore resort to filtering out any datapoints for which all six qubit frequencies were drastically different from their typical range. The fitting and filtering process is explained further in Supplementary Section 1.

The four gray regions indicate thermal cycles, whereby the sample was warmed up to room temperature and cooled down again without breaking the vacuum of the dilution refrigerator. We find no significant impact of thermal cycles on the gate voltages required to find the qubits, apart from the initial tuning period immediately following a thermal cycle. In some thermal cycles, some of the qubit frequencies shift by up to several MHz, despite returning to the same nominal magnetic field value of 400 mT. To magnetize the micromagnet, the external field is first set to 2 T before ramping down to 400 mT. Differences in this procedure could in part explain the small shifts in the observed qubit frequencies. The 16 red regions indicate periods longer than seven days where no DC gate voltage was changed by more than 15 µV. These amount to a total of 259 days, which corresponds to the device operating in a practically stable voltage condition for 28% of the 912 day period. Furthermore, during these stable periods, qubit frequencies would remain stable up to ±7 MHz.

Gate voltage stability

Changes in the DC voltage settings cause the qubit frequency of nearby qubits to shift, either by modifying the g-factor47 or by displacing the spins in the stray magnetic field gradient induced by the micromagnet48. For example, between September and November 2023 in Fig. 2, we notice that the qubit frequencies undergo an unstable period, which coincides in time with a period of device tuning that requires many changes in the DC voltage settings. Even without targeted measurements to probe the sensitivity of the qubit frequencies to changes in individual gate voltages, a further analysis of the data in this segment of Fig. 2 already provides indications of correlations between qubit frequencies and gate voltages (see Supplementary Section 2). Voltages are typically tuned to optimize tunnel couplings to the reservoir for loading and unloading of the dots and between adjacent dots for optimizing initialization, readout, and two-qubit gate fidelities. Furthermore, voltages are sometimes retuned in an attempt to reduce the impact of strongly coupled TLFs49.

We also characterized the long-term variations in gate voltages by tracking the set DC voltages for each stable period. In Fig. 3, we plot the difference in gate voltage setting from period 1 to 16. We observe that most set values did not change by more than 500 mV over the 912-day period, with the exception of gates P1, P3, P6, B0, and B6. Apart from P3, these gates are at the edges of the array and are used to control the loading/unloading of the dots. All plunger gate voltages undergo a net positive change, whereas the majority of the barrier gate voltages undergo a negative change. The outer barrier gate voltages B0 and B6 see the most drastic negative change, which was intended to reduce the tunnel coupling to the sensing dots to operate the device in “isolated” mode. In order to keep the electron number in dots 1 and 6 fixed, the plungers P1 and P6 had to be taken to larger values.

Voltage difference ∆V=VN−V1, where V1 is the voltage setting corresponding to period 1, extracted from the 16 stable periods identified in Fig. 2 and displayed chronologically. This dataset highlights the drift in gate voltages required to operate the full 6-qubit array over the 912 day period. Most gate voltages do not drift by more than 500 mV.

Long-term qubit frequency variations extracted from frequency scans

Altogether, including thermal cycles and gate voltage changes, and with a variety of experiments running, the qubit frequency shifts seen in Fig. 2 range from ±37 MHz for Q4 to ±93 MHz for Q1. Once a stable operating condition of magnetic field and DC gate voltages is established (the red regions in Fig. 2), we observe an average range and standard deviation in the qubit frequency of 867 kHz and 268 kHz, respectively, averaged over all qubits and stable periods.

To get further insight into the variations of the qubit frequencies during the stable periods, we inspect the longest stable periods with consistent frequency calibrations in Fig. 4, extending over 19, 20, 36, and 29 days, respectively. We notice some variability in exactly how steady the frequency of each qubit is in any given stable period.

(obtained from Fig. 2). Each plot corresponds to the qubit frequency variations in the stable period indicated above the panel. In each panel, the top six subpanels correspond to qubit frequency variations, whilst the bottom subpanel shows the mixing chamber temperature at the time of data collection. a Data taken at base temperature of 12.8 mK. b Data taken while the mixing chamber temperature was varied from 12.8 mK to about 800 mK. We observe that qubit frequency shifts globally correlate with the mixing chamber temperature over this period. c Data taken at 200 mK before changing to 300 mK. The temperature was no longer logged after 18/06. d Data taken at 200 mK.

Motivated by the findings in ref. 45, where a dependence of the qubit frequencies with temperature was reported, we include plots of the mixing chamber temperature below the qubit frequency evolution for each period. In Fig. 4b, we can notice clear global correlations between all qubit frequencies, which in this case are also correlated with the temperature changes of the mixing chamber (from nominally 12.8 mK to about 800 mK).

Averaged 1-hour qubit frequency variations extracted from Ramsey-style experiments

In order to quantify qubit frequency variations during the stable periods more accurately and on shorter timescales, we utilize Ramsey experiments that are implemented overnight to extract the average 1-hour qubit frequency variations experienced by all qubits in both the linear and 2 × 2 devices. The circuit we implement and an example Ramsey oscillation are shown in Fig. 5a shows schematically the circuit used to perform a Ramsey experiment where a virtual Rz(ωt) operation, also referred to as virtual detuning, is included to facilitate the data fitting and analysis. A single Ramsey experiment is shown in the plot below, which takes approximately 30 seconds to run. We repeat these measurements for 10–41 hours, resulting in a full dataset as shown in Fig.5 b.

a Circuit diagram of the Ramsey sequence used in the experiments, along with an example measurement trace. Error bars correspond to the 95% binomial confidence interval of the number of recorded spin up measurements with respect to the total number of shots, and the red line is fit to Eq. 3. The microwave drive frequency is fixed to the precalibrated qubit frequency fMW = f0. A virtual detuning of ω = 2 MHz is realized by a virtual rotation Rz(ωt) to enable a more reliable estimation of the qubit frequency variations by fitting deviations from a 2 MHz oscillation frequency. b All oscillations collected for qubit 6 in the linear device during a single collection run. c Deviations away from 2 MHz of the frequencies extracted from b as a function of time (left) and displayed as a histogram (right). The red line in the histogram is a fit to a Gaussian distribution, with a fitted standard deviation of σ = 33.9 kHz.

A total of 46 such datasets were collected, with 24 and 22 datasets collected from the linear and 2 × 2 devices, respectively (further details are provided in Supplementary Section 3). Operating conditions such as the mixing chamber temperature, gate voltages, and magnetic field were kept constant throughout a single data collection run; however, the temperature and gate voltages can vary from day to day.

For most Ramsey experiments, the detuning was set to 2 MHz and the maximum wait time of 1.5 µs ensured a high degree of accuracy in fitting the oscillation frequency (for a few datasets, a 4 MHz detuning and 0.75 µs wait time were used). In the linear device, the average recorded uncertainty in the extracted qubit frequency is 8.7 kHz for the Ramsey experiments, compared to an average recorded uncertainty in the fit from the qubit frequency calibration scan of 22.0 kHz. These values are extracted from the covariance matrix of the fit to Eqs. 2 and 3 (below) respectively and are averaged across all recorded measurements over all qubits. The number of data points in the Ramsey measurements was chosen to avoid aliasing. Readout calibrations were periodically interleaved every 10 Ramsey experiments to ensure high visibility throughout the full collection period. When data was collected on multiple qubits, a full Ramsey trace was obtained on one qubit before proceeding to the next. Finally, each oscillation is fitted with a function of the form

where the fit parameters are the oscillation frequency \(\mathop{\Delta }\limits^{ \sim }\), a phase offset ϕ, the dephasing time \({T}_{2}^{* }\), and parameters A and B that depend on state preparation and readout errors. Deviations of \(\mathop{\Delta }\limits^{ \sim }\) away from 2 MHz correspond to deviations in the qubit frequency. We assume all of the used fitting parameters to be quasi-static during a single Ramsey experiment, justifying the use of a Gaussian decay envelope. After fitting the oscillations, we perform a filtering protocol utilizing a normalized chi-square metric to filter out any low-quality traces (as described in Supplementary Section 1) to form a dataset as shown in Fig. 5c.

In Fig. 6, we plot the average of the qubit frequency variations \(\mathop{\sigma }\limits^{ \sim }\) observed over 1-hour windows. Each full qubit frequency drift dataset, consisting in total of N datapoints x = (x1,x2,…,xN), is segmented into M chronological sections [x1,x2,…,xM] where M was selected such that each xi would cover approximately a 1-hour time window. For every section i the corresponding standard deviation σi in qubit frequency was calculated. The datapoints plotted in Fig. 6 show the average of those standard deviations for a given dataset x, i.e:

For each dataset, labeled by the day of the year in 2023, we segment the qubit frequency drift data into 1-hour sections and track the standard deviation of the recorded qubit frequencies σi for each section i. The data points in the figure show the average of the standard deviation of the qubit frequency over one hour, \(\bar{\sigma}\), for each dataset as described in Eq. 4. The solid error bars correspond to one standard deviation on σi for each dataset (Eq. 5) and express how the magnitude of the qubit frequency variations itself fluctuates throughout the data collection period (of 10–41 hours). The dashed error bars correspond to the minimum and maximum observed σi throughout the data collection period (Eq. 6). The mixing chamber temperature at the time of data collection is displayed at the top of each panel.

From the frequency drift values σi of the M one-hour sections, we also extract their standard deviation, and the range from the minimum to the maximum value, i.e:

which are plotted as error bars in Fig. 6. We do not have enough data points to draw conclusions on the impact of the mixing chamber temperature on the average 1-hour qubit frequency drifts.

For all measurements, the qubit frequencies show a maximum standard deviation of less than 200 kHz within a 1-hour time window. Focusing first on the linear device, we observe that σmax of qubits 4-6 never exceeds 50 kHz within a single data collection period. However, we can also notice that qubits 1 and 2 exhibit both a larger average and spread in σi compared to the rest, highlighting how the frequency variations in time of the qubits can vary substantially within the same device.

We speculate that the larger frequency variations seen in qubits 1 and 2 are due to localized and strongly-coupled TLFs, which could originate from electric33 (e.g., from nearby charge defects in the heterostructure or gate dielectrics) or magnetic50 (29Si nuclear spins) sources. For example, we can identify the presence of a TLF strongly coupling to qubit 1, which induces a telegraph signal in the qubit frequency with an amplitude of 103-315 kHz and a switching rate on the order of twice per hour (Supplementary Fig. 14). We note that the activation and switching rate of individual charge TLFs are known to be affected by DC voltages49,51. Given that the separate datasets x are typically taken with different DC gate voltage settings, this can explain the variability in the observed \(\bar{\sigma}\), σmin, and σmax for any given qubit. Furthermore, in the course of collecting full datasets x lasting between 10 and 41 hours, we have also observed three instances of a single discrete jump in qubit frequencies of about 250 to 380 kHz in amplitude for qubits 1 and 2, which explain the large σmax on 12/04, 27/06, and 28/06. These are documented further in Supplementary Section 4.

In the 2 × 2 device, we observe that qubit 3 consistently experiences lower levels of frequency variations when compared with qubits 1 and 2. Furthermore, we observe larger deviations in all qubit frequencies when compared with the linear device. A priori, we could expect qubits from both devices to exhibit similar levels of drift, since both devices follow nearly identical fabrication procedures and are hosted in similar heterostructures (detailed in the Methods section). In fact, the 2 × 2 device has a 1 nm thinner quantum well, which has been shown to reduce the strength of charge noise52.

A major difference between the two devices, however, is the micromagnet gradient field at the quantum dot locations. In the linear device, the micromagnet was engineered such that the qubits would be positioned in the sweetspot of the decoherence gradient. When moving to two dimensions in the 2 × 2 device, the qubits no longer reside in the sweetspot. Whereas the exact dot locations in the actual device are not known, we expect the resulting decoherence gradients to be roughly twice as large as in the linear device, based on numerical simulations12,40. This could induce larger qubit frequency variations in the 2 × 2 device even if the level of charge noise were the same or lower as in the linear device.

Fidelity of X π/2 gate impacted by qubit frequency detuning

The uncertainty in the qubit frequencies at any point in time has several consequences. First, when a qubit is idling in a state of superposition, random fluctuations in the resonance frequency will result in a random phase pickup. The effect of slow qubit frequency variations during idling can be largely removed using dynamical decoupling techniques based on the spin-echo concept, although the decoupling pulses themselves will also produce errors20. Second, when attempting to resonantly drive a qubit, the drive frequency will no longer be on resonance if the qubit frequency has shifted. In the literature, this effect has been mitigated by background recalibrations of the qubit frequency and adjusting the drive frequency accordingly12. More resilience to unknown qubit frequency detunings can be achieved using composite rotations or by tailoring the amplitude and/or phase profile of the drive signal53. Nevertheless, it is instructive to quantify how qubit frequency detunings affect the fidelity of single-qubit gates implemented by standard fixed-amplitude and fixed-frequency bursts.

The EDSR Hamiltonian (Eq. 1) enables us to engineer arbitrary rotations about an axis in the xy-plane of the Bloch sphere by adjusting the amplitude, phase and duration of the microwave burst. We here assume that the burst is applied nominally on resonance. However, the presence of qubit frequency noise η(t), which we take to be quasi-static for the duration of a burst, introduces a detuning ∆(t) = η(t), i.e., a random \({\hat{\sigma }}_{z}\) component which effectively reduces the control fidelity if left unaccounted for. We can derive the expected gate fidelity54 of a single-qubit Xπ/2 gate (Supplementary Section 5) as a function of the detuning ∆ and the Rabi frequency Ω as

with λ = √∆2 + √Ω2.

In Fig. 7a we plot the Xπ/2 gate infidelity as a function of the Rabi frequency and qubit frequency detuning. As is well known, for a given frequency detuning, we can enhance the fidelity by increasing the Rabi frequency through a larger driving amplitude. In Fig. 7b, we show a table with the required Rabi frequencies corresponding to an Xπ/2 gate infidelity of 1%, 0.1% and 0.01% at set qubit frequency detunings of 50, 100, 150, and 200 kHz. In the linear device, the frequencies of qubits 5 and 6 do not vary by more than 50 kHz in most 1-hour time windows. According to Eq. 7, at this level of detuning and to retain Xπ/2 gate fidelities of 99.99%, it is sufficient to drive with a Rabi frequency of 2.89 MHz. The frequency of qubit 3 in the 2 × 2 device varies by less than 100 kHz for most one-hour windows, and thus it is sufficient to drive at 5.77 MHz to retain the same level of fidelity. However, long-term drift on the scale as observed in Fig. 4 clearly cannot be left uncompensated, as, for example, a detuning of 0.5 MHz would require a Rabi frequency of 28.9 MHz to retain a Xπ/2 gate fidelity of 99.99%, which is unattainable in this device. As also observed in ref. 1, the Rabi frequency becomes non-linear with respect to the microwave amplitude and eventually saturates. Furthermore, randomized benchmarking experiments have indicated that the highest attainable Rabi frequencies do not necessarily produce the highest fidelities6, since heating and leakage effects become more severe at larger driving amplitudes.

a The infidelity of an Xπ/2 gate, in the absence of other sources of noise, as a function of qubit frequency detuning and Rabi frequency. Dashed black lines represent the gate infidelity corresponding to 0.01%, 0.1%, 1% and 10%. b Minimum Rabi frequency needed to retain 1%, 0.1% and 0.01% infidelity at the specified qubit frequency detunings.

Qubit frequency noise spectra

In order to get more insight in the nature of the qubit frequency variations, we perform Fourier analysis on the data collected in the time domain to obtain the noise power spectral density (PSD). The Ramsey-style data are used to extract the noise spectra over a frequency range of approximately [10−4,10−2] Hz, whilst the frequency scan data are used to probe the noise spectra over a frequency range of approximately [10−7,10−5] Hz. Even lower frequency ranges were not accessible despite the total data collection period of 912 days, as we only consider data taken at the specified stable periods from Fig. 2. This gave us datasets up to a timescale of 36 days, yielding noise spectra in the sub-µHz range. Even studies on the timescale of a month are rare, so experimental data available in the literature for comparison remains limited.

Qubit frequency noise with a 1/fα spectrum, with α ≈ 1, has been reported in Si/SiGe devices1,23,37,38,55. However, these studies characterize the noise spectra only at frequencies of 10−4 Hz and above, with the exception of ref. 55. Interestingly, that study reports a cross-over in the qubit frequency noise spectrum from α ≈ 2 below f ≈ 10−4 − 10−3 Hz, to α ≈ 1.5 at higher frequencies, and notes a corresponding transition in the charge noise spectrum from 1/f2 to 1/f. A transition in the charge noise spectrum with similar characteristics is reported in ref. 33 for Si/SiO2 quantum dots as well.

In Fig. 8a, we plot the PSD data points from both the Ramsey experiments (circles) and the frequency scans (triangles) (further details on the methods used to obtain these plots are provided in the Methods and Supplementary Section 6). The solid red lines are fits to the PSD data points from the Ramsey measurements. The fits give α in the range of 0.68 − 1.62. We can observe that the PSDs extracted from frequency calibration data consistently lie above the trends extrapolated back from the PSDs extracted from Ramsey data, indicating a transition to a PSD with a larger value of α at lower frequencies. The black dashed lines are a guide to the eye corresponding to α = 2, and visually match the observations reasonably well. The transition frequency is around f = 10−4 Hz, not very different from the earlier observations33,55. In principle, 1/f noise spectral densities could result from the evolution of a sparse bath of nuclear spins. However, the fact that also charge noise transitions to 1/f2 behavior below f = 10−4 Hz33,55, hints that the qubit frequency noise at these frequency ranges could arise from atypical charge noise, i.e. not originating from the ensemble of TLFs with log-uniformly distributed switching rates that gives rise to the typical 1/f behavior.

a A comparison of the PSDs extracted from the Ramsey data and the frequency scan data for qubits 1-6 in the linear device. The frequency calibration data is from period 10 as described in Fig. 4, which corresponds to the longest time period with a sufficient number of datapoints at a stable operating condition of gate voltage, magnetic field and temperature. The Ramsey data for qubits 1-3 was collected on 21/04/2023 and for qubits 4-6 on 29/06/2023. The solid red lines are fits to the Ramsey PSD data points to S0/fα, with S0 and α as fit parameters. The black dashed line is a guide to the eye showing a 1/f2 dependence. We note an unexpected change in slope of the PSD from 1/fα (with α ≈ 1) to 1/f2 at a transition frequency of approximately 10−4 Hz for all qubits. b Fitted values of α and Sf=1mHz of each PSD obtained from fits to the Ramsey data as in a. The DC gate voltage setting for each date is reported in Supplementary Section 3. The error bars (2σ) are extracted from the covariance matrix of the fit. The mixing chamber temperature at the time of data collection is shown at the top.

In Fig. 8b, we show the fitted parameters of the PSDs from all Ramsey experiments to S(f) = S0/fα. Most qubit frequency noise spectra exhibit a good agreement to the fit, although the fitted values of α show a large degree of variability. We observe consistently lower values of Sf=1mHz in the linear device when compared to the 2 × 2 device, which was anticipated given the smaller qubit frequency variations seen in the time domain (see Fig. 6). The observed values for Sf=1mHz are in the same range as the values reported in earlier studies1,23,37,38,55, which range from approximately [1011,1013] Hz2/Hz.

Most noise profiles show relative consistency over time, but at the same time the variability seen in Fig. 8b highlights that caution is due when drawing firm conclusions on the value of α or Sf=1mHz taken on any particular day. A strong correlation between qubit frequency noise and charge noise was documented in ref. 37. Furthermore, operating conditions such as temperature56 can influence charge noise levels and DC gate voltages49 can (de)activate individual TLFs, and it is likely that both will also influence qubit frequency noise spectra. This being said, we also observe changes in the extracted values of α or Sf=1mHz under identical operating conditions of temperature, DC voltages, and magnetic field. This is the case for qubit 1 in the 2 × 2 device from June 9th to 10th, and to a lesser extent for qubit 6 of the linear device from June 7th to 9th. The same behavior is seen in the time-domain data in Fig. 6.

Discussion

We have quantified the qubit frequency variations and characterized the PSDs of 10 different qubits across two different devices. In some cases, such as qubits 1 and 2 of the linear device, the frequency variations exhibit telegraph signals and are presumably dominated by a strong coupling to a local TLF. Such events are particularly harmful for maintaining high-fidelity qubit operations. In the PSDs, the most striking observation is a transition in the slope of the qubit frequency noise spectrum for all qubits in the linear device from 1/f-like behavior above ≈ 10−4 Hz to 1/f2-like behavior at frequencies below ≈ 10−4 Hz.

Whereas it is difficult to be certain of the origin of the TLF’s and the observed power spectral densities, we can consider the following. For the sparse bath of nuclear spins present in the device (under 800 ppm residual 29Si in the quantum well), the magnetic noise spectrum can tend towards a 1/fα-like slope with α < 220,25,26. Furthermore, typical nuclear spin bath models assume that the low-frequency tail of the spectrum flattens out23. Considering this, it is unlikely that the transition that we observe is caused solely by the nuclear spin bath. As for two-level charge fluctuators, any noise spectrum can in principle, be explained by a certain distribution of the switching rates of the TLFs. For example, a 1/f2 spectrum above a certain frequency and a flat spectrum below it, points at a single dominant TLF, whereas a 1/f spectrum is indicative of a log-uniform distribution of switching rates. For the same reason, a combination of nuclear spin noise and electric TLFs cannot be excluded given the observed qubit frequency PSDs. However, it is worth noting that a similar transition from 1/f2 to 1/f behavior, and with a comparable cross-over frequency, has been observed in charge noise spectra reported in refs. 33,55. The similarity would suggest an electrical origin of the observed transition in the qubit frequency PSDs, which may be caused by a distribution of charge TLFs that deviates from the more typical log-uniformly distributed switching rates. Another possible explanation could be the presence of mobile charges in the gate oxide33. These charges are free to slowly move around and could be expected to exhibit Brownian motion which has a characteristic noise spectrum with a 1/f2 slope. In this case, the picture could be that Brownian motion of slowly moving charges dominates the PSD below ≈ 10−4 Hz and a standard log-uniform distribution of TLFs dominates the PSD at higher frequencies, with additional contributions from nuclear spin noise.

Whereas we cannot be sure of the dominant sources of frequency variations, we can still recommend several steps to obtain more stable qubit frequencies. Nuclear spin noise can be further suppressed by eliminating additional 29Si nuclear spins in the quantum well (recent studies have already achieved 50ppm residual 29Si in the quantum well57,58), and by also isotopically purifying the SiGe barrier into which the electron wavefunction penetrates, reducing both the number of 29Si and 73Ge nuclear spins. For charge fluctuators, it is commonly believed that the majority of charge traps reside in the gate oxide layer. Reducing the thickness of this layer has been shown to be effective in reducing charge noise levels at the quantum well56. A systematic effort to develop gate oxides that minimize charge noise at cryogenic temperatures will be needed to obtain a further reduction in the qubit frequency variations. Furthermore, the design of the micromagnet can also be optimized further to decrease the decoherence gradient, which will directly reduce the impact of electrical TLFs on the qubit frequency, albeit with a trade-off in qubit addressability and possibly the driving efficiency. Finally, we note that reducing the possible mechanisms for qubit frequency variations one at a time can help clarify what are the dominant mechanisms.

In conclusion, we report the calibrated qubit frequencies for all six qubits in a linear quantum dot device over a span of 912 days. Over this entire period, the qubit frequencies varied by up to ±100 MHz, under the influence of changes in the DC gate voltages and mixing chamber temperature, and while running a variety of experiments on the device. We identified 16 time windows of one week or longer during which the gate voltages were not adjusted by no more than 15 µV, yet qubit initialization, control, and readout were maintained. During those “stable” periods, the qubit frequencies varied by less than ±7 MHz. On days where the gate voltages, magnetic field, and temperature were all kept constant, we performed overnight Ramsey measurements on the linear device and a 2 × 2 device. Over 1-hour time windows during these overnight measurements, the standard deviation in the qubit frequency was below 200 kHz for all qubits, and below 50 kHz on some qubits of the linear device. To put this number in perspective, a detuning of the qubit frequency by 50 kHz permits a 99.99% single-qubit gate fidelity provided the Rabi frequency exceeds 2.9 MHz, which is an accessible value in practice. We also converted the time-domain data to power spectral densities for the qubit frequencies, fitting and comparing with a S(f) = S0/fα dependence. Since the physically possible frequencies are bounded, one might expect the PSD to saturate at very low frequencies. Instead, we observe that the PSD, hence the amplitude of the qubit frequency variations, continues to increase all the way down to the µHz range (corresponding to weeks). Most strikingly, comparing the noise spectra from the Ramsey and frequency calibration data revealed in fact a steeper slope α at frequencies below ≈ 10−4 Hz. Furthermore, we observed that the PSDs not only vary substantially between two devices despite the similar heterostructure growth conditions and fabrication flow used, but also between qubits within the same device, and in some cases show variability from day to day.

Whereas dedicated studies of the stability of qubit parameters on the timescale of weeks to months obviously require patience to carry out, it will be important to continue such experiments, as it looks problematic to extrapolate qubit frequency variations on this ultralong timescale from measurements on more accessible timescales. The better the long-term stability, the lower the demands on background calibrations will be, and the simpler the autonomous operation of spin-qubit systems. It will be especially helpful to eliminate dominant two-level fluctuators, which cause the qubit frequency to jump by a large amount (of the order of 103–351 kHz) at rare but random points in time.

Methods

Device heterostructure and fabrication

Both devices are fabricated on a 28Si/SiGe heterostructure, with a strain-relaxed Si0.7Ge0.3 buffer layer. On top of this an isotopically enriched 28Si quantum well is grown (residual 29Si concentration below 800 ppm) with a thickness of 8 nm and 7 nm for the 6D2S and 2 × 2 devices respectively. Then a 30 nm thick Si0.7Ge0.3 buffer layer is grown with a 1 nm silicon oxide cap. A gate stack consisting of three layers of Ti:Pd metallic gates is deposited and separated from the heterostructure by Al2O3, and separated from each other by 5 nm Al2O3. The metal gate film thickness is as described in ref. 59. Finally, another Al2O3 layer is deposited and a 200 nm thick Ti:Co micromagnet is fabricated.

Obtaining power spectral densities

We note that the extraction of PSDs from the time domain data is hindered by both a low number of datapoints and a non-uniform sampling rate. To overcome this, we first interpolate our time-domain data onto a uniform time axis before implementing the standard FFT. We validated this procedure by performing an analysis on artificially generated data (see Supplementary Section 6 for details).

Data availability

The data and code used throughout this manuscript are available for access in the Zenodo repository (https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.15632269).

References

Yoneda, J. et al. A quantum-dot spin qubit with coherence limited by charge noise and fidelity higher than 99.9%. Nat. Nanotech. 13, 102 (2018).

Lawrie, W. I. L. et al. Simultaneous single-qubit driving of semiconductor spin qubits at the fault-tolerant threshold. Nat. Commun. 14, 3617 (2023).

Nakajima, T. et al. Coherence of a driven electron spin qubit actively decoupled from quasistatic noise. Phys. Rev. X 10, 011060 (2020).

Zwerver, A. M. J. et al. Qubits made by advanced semiconductor manufacturing. Nat. Electron. 5, 184–190 (2022).

Mądzik, M. T. et al. Precision tomography of a threequbit donor quantum processor in silicon. Nature 601, 348 (2022).

Noiri, A. et al. Fast universal quantum gate above the fault-tolerance threshold in silicon. Nature 601, 338 (2022).

Xue, X. et al. Quantum logic with spin qubits crossing the surface code threshold. Nature 601, 343 (2022).

Mills, A. R. et al. Two-qubit silicon quantum processor with operation fidelity exceeding 99%. Sci. Adv. 8, eabn5130, (2022).

Borsoi, F. et al. Shared control of a 16 semiconductor quantum dot crossbar array. Nat. Nanotech. 19, 21 (2024).

Neyens, S. et al. Probing single electrons across 300-mm spin qubit wafers. Nature 629, 80 (2024).

Ha, S. D. et al. Two-dimensional Si spin qubit arrays with multilevel interconnects. PRX Quantum 6, 030327 (2025).

Philips, S. G. J. et al. Universal control of a sixqubit quantum processor in silicon. Nature 609, 919–924 (2022).

George, H. C. et al. 12-spin-qubit arrays fabricated on a 300 mm semiconductor manufacturing line. Nano Lett. 25, 793 (2024).

John, V. et al. A two-dimensional 10-qubit array in germanium with robust and localised qubit control, arXiv preprint arXiv:2412.16044 (2024).

Nakajima, T. et al. Real-time feedback control of charge sensing for quantum dot qubits. Phys. Rev. Appl. 15, L031003 (2021).

Berritta, F. et al. Physics-informed tracking of qubit fluctuations. Phys. Rev. Appl. 22, 014033 (2024).

Berritta, F. et al. Real-time two-axis control of a spin qubit. Nat. Commun. 15, 1676 (2024).

Ristè, D., Bultink, C., Lehnert, K. W. & DiCarlo, L. Feedback control of a solid-state qubit using high-fidelity projective measurement. Phys. Rev. Lett. 109, 240502 (2012).

Park, Y., Oh, H., Yoo, S., Kim, T. & Cho, D. A feedback control method to maintain the amplitude of the RF signal applied to ion traps. Appl. Sci 11, 837 (2021).

Burkard, G., Ladd, T. D., Pan, A., Nichol, J. M. & Petta, J. R. Semiconductor spin qubits, Rev. Mod. Phys. 95, 025003 (2023).

Reilly, D. et al. Measurement of temporal correlations of the overhauser field in a double quantum dot. Phys. Rev. Lett. 101, 236803 (2008).

Malinowski, F. K. et al. Spectrum of the nuclear environment for GaAs spin qubits. Phys. Rev. Lett. 118, 177702 (2017).

Rojas-Arias, J. et al. The origins of noise in the Zeeman splitting of spin qubits in natural-silicon devices, arXiv preprint arXiv:24008.13707 (2024).

Veldhorst, M. et al. An addressable quantum dot qubit with fault-tolerant control-fidelity. Nat. Nanotech. 9, 981 (2014).

Eng, K. et al. Isotopically enhanced triple-quantum-dot qubit. Sci. Adv. 1, e1500214 (2015).

Mądzik, M. T. et al. Controllable freezing of the nuclear spin bath in a single-atom spin qubit. Sci. Adv. 6, eaba3442 (2020).

Kawakami, E. et al. Gate fidelity and coherence of an electron spin in an Si/SiGe quantum dot with micromagnet. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 113, 11738 (2016).

Hendrickx, N. et al. Sweet-spot operation of a germanium hole spin qubit with highly anisotropic noise sensitivity. Nat. Mat. 23, 920 (2024).

Dutta, P. & Horn, P. Low-frequency fluctuations in solids: 1/f noise. Rev. Mod. Phys. 53, 497 (1981).

Güngördü, U. & Kestner, J. Indications of a soft cutoff frequency in the charge noise of a Si/SiGe quantum dot spin qubit. Phys. Rev. B 99, 081301 (2019).

Bermeister, A., Keith, D. & Culcer, D. Charge noise, spin-orbit coupling, and dephasing of single-spin qubits, Appl. Phys. Lett. 105 (2014).

Mehmandoost, M. & Dobrovitski, V. Decoherence induced by a sparse bath of two-level fluctuators: Peculiar features of 1/f noise in high-quality qubits. Phys. Rev. Res. 6, 033175 (2024).

Elsayed, A. et al. Low charge noise quantum dots with industrial CMOS manufacturing. npj Quantum Info 10, 70 (2024).

Connors, E. J., Nelson, J., Edge, L. F. & Nichol, J. M. Charge-noise spectroscopy of Si/SiGe quantum dots via dynamically-decoupled exchange oscillations. Nat. Commun. 13, 940 (2022).

Seedhouse, A. E. et al. Wavelet correlation noise analysis for qubit operation variable time series. Sci. Rep. 15, 11065 (2025).

Tanttu, T. et al. Assessment of the errors of high-fidelity two-qubit gates in silicon quantum dots, Nat. Phys. 1 (2024).

Yoneda, J. et al. Noise-correlation spectrum for a pair of spin qubits in silicon. Nat. Phys. 19, 1793 (2023).

Rojas-Arias, J. S. et al. Spatial noise correlations beyond nearest neighbors in 28Si/Si-Ge spin qubits. Phys. Rev. Appl. 20, 054024 (2023).

Last, T. et al. Quantum Inspire: QuTechs platform for co-development and collaboration in quantum computing. In Nov. Patt. Tech. Semicon., MEMS/NEMS and MOEMS 2020, Vol. 11324 (SPIE, 2020) pp. 49–59.

Unseld, F. K. et al. A 2D quantum dot array in planar 28Si/SiGe. Appl. Phys. Lett. 123, 084002 (2023).

Unseld, F. K. et al. Baseband control of single-electron silicon spin qubits in two dimensions. Nat. Commun. 16, 5605 (2025).

Seedhouse, A. E. et al. Pauli blockade in silicon quantum dots with spin-orbit control. PRX Quantum 2, 010303 (2021).

Loss, D. & DiVincenzo, D. P. Quantum computation with quantum dots. Phys. Rev. A 57, 120 (1998).

Pioro-Ladriere, M. et al. Electrically driven single-electron spin resonance in a slanting Zeeman field. Nat. Phys. 4, 776 (2008).

Undseth, B. et al. Hotter is easier: unexpected temperature dependence of spin qubit frequencies. Phys. Rev. X 13, 041015 (2023).

de Fuentes, I. F. et al. Running a six-qubit quantum circuit on a silicon spin qubit array, arXiv preprint arXiv:2505.19200 (2025).

Liles, S. et al. Electrical control of the g tensor of the first hole in a silicon MOS quantum dot. Phys. Rev. B 104, 235303 (2021).

Kobayashi, T. et al. Charge-induced energy shift of a single-spin qubit under a magnetic-field gradient. Phys. Rev. Appl. 23, 054078 (2025).

Ye, F., Ellaboudy, A. & Nichol, J. M. Stabilizing an individual charge fluctuator in a Si/Si-Ge quantum dot. Phys. Rev. Appl. 23, 044063 (2025).

Hensen, B. et al. A silicon quantum-dot-coupled nuclear spin qubit. Nat. Nanotech. 15, 13 (2020).

Ye, F. et al. Characterization of individual charge fluctuators in Si/SiGe quantum dots. Phys. Rev. B 110, 235305 (2024).

Paquelet Wuetz, B. et al. Reducing charge noise in quantum dots by using thin silicon quantum wells. Nat. Commun. 14, 1385 (2023).

Vandersypen, L. M. & Chuang, I. L. NMR techniques for quantum control and computation. Rev. Mod. Phys. 76, 1037 (2004).

Pedersen, L. H., Møller, N. M. & Mølmer, K. Fidelity of quantum operations. Phys. Lett. A 367, 47 (2007).

Struck, T. et al. Low-frequency spin qubit energy splitting noise in highly purified 28Si/SiGe. npj Quantum Info 6, 40 (2020).

Connors, E. J., Nelson, J., Qiao, H., Edge, L. F. & Nichol, J. M. Low-frequency charge noise in Si/SiGe quantum dots. Phys. Rev. B 100, 165305 (2019).

Klos, J. et al. Atomistic compositional details and their importance for spin qubits in insotope-purified silicon quantum wells. Adv. Sci. 11, 42 (2024).

Huang, J. Y. et al. High-fidelity spin qubit operation and algorithmic initialization above 1 K. Nature 627, 772 (2024).

Lawrie, W. I. L. et al. Quantum dot arrays in silicon and germanium, Appl. Phys. Lett. 116 (2020).

Acknowledgements

We acknowledge the contribution of A. Sammak in the growth of the 28Si/SiGe heterostructures. We also thank J. Rojas-Arias, P. Stano, and the members of the Vandersypen group for useful discussions. This research was supported by the Horizon Europe program of the European Union under grant agreement no. 951852 (QLSI) and no. 101174557 (QLSI2), by the “Quantum Inspire–the Dutch Quantum Computer in the Cloud” project (Project No. NWA.1292.19.194) of the NWA research program “Research on Routes by Consortia (ORC),” which is funded by the Dutch Research Council (NWO), by Intel Corporation and by the Army Research Office (ARO) under grant numbers W911NF-17-1-0274 and W911NF-12-1-0607. The views and conclusions contained in this document are those of the authors and should not be interpreted as representing the official policies, either expressed or implied, of the ARO or the US Government. The US Government is authorized to reproduce and distribute reprints for government purposes, notwithstanding any copyright notation herein.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

K.C. and B.U. performed experiments on both the linear and 2 x 2 devices. I.F.d.F., E.R., O.P., S.G.J.P. and M.M. assisted in data collection for the linear device and F.K.U. for the 2 x 2 device. K.C. performed the data analysis and simulations. S.V.A. and L.T. contributed to device fabrication. G.S. contributed to the growth of the Si/SiGe heterostructure. K.C. and L.M.K.V. wrote the manuscript with comments from all authors. L.M.K.V. conceived and supervised the project.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Capannelli, K., Undseth, B., Fernández de Fuentes, I. et al. Tracking spin qubit frequency variations over 912 days. npj Quantum Inf 11, 192 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41534-025-01134-6

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41534-025-01134-6